Abstract

Objectives:

To explore trends in demographic characteristics of scleral lens (SL) practitioners and primary indications for SL fitting over 5 years.

Methods:

An online survey similar to the 2015 Scleral Lenses in Current Ophthalmic Practice Evaluation (SCOPE) study was designed and administered from November 8, 2019, through March 31, 2020, to attendees at 2 international contact lens meetings, members of the Scleral Lens Education Society, and participants in the 2015 SCOPE study. Practitioners reporting at least 5 completed SL fits were included in the analysis.

Results:

Of 922 respondents, 777 had fit at least 5 SLs: 63% from the US (59 other countries were represented), findings similar to the 2015 survey in which 799 respondents (72%) were US-based, 49 from other countries. Most practitioners were in community practice (76%) rather than academic practice (24%). In 2015, 64% were in community practice and 36% in academic practice. A median of 84% of SLs were fit for corneal irregularity, 10% for ocular surface disease, and 2% for uncomplicated refractive error. In comparison, the 2015 indications were 74%, 16%, and 10%, respectively. The median number of fits completed per practitioner was 100 (range, 5–10,000; mean [SD] 284 [717]; n=752). In 2015, the median was 36 (range, 5–3,600; mean [SD] 125 [299]; n=678).

Conclusions:

The number of experienced SL practitioners is increasing, as is international representation. Most practitioners practice in community rather than academic settings. SLs continue to be primarily prescribed for corneal irregularity and are rarely used solely for correction of refractive error.

Keywords: corneal irregularity, ocular surface disease, scleral lenses

Interest in scleral lenses (SLs) has increased substantially over the past decade.1–3 SLs have been prescribed to improve both vision and comfort for patients with irregular corneal surfaces and ocular surface disease (OSD).4, 5 Practitioners have incorporated SLs into their practices, and manufacturers have responded to the increase in demand by providing new and innovative SL designs.

The Scleral Lenses in Current Ophthalmic Practice Evaluation (SCOPE) study group deployed a survey in 2015 to obtain an overview of the use of SLs.6 That study provided insights into the number of SLs being prescribed, demographic characteristics of practitioners actively fitting SLs, and indications for SL use. Data from the 2015 study described a rapidly expanding and relatively new industry. Dramatic annual increases in the number of practitioners fitting SLs were noted, beginning in 2008 and continuing through 2014; the number of new graduates who incorporated SLs into their practices each year roughly doubled between 2009 and 2014. The majority of respondents (65%) were relatively inexperienced, having fit 50 or fewer lenses. The SCOPE study group conducted a similar cross-sectional study in 2020 to determine whether the expansion of SL practice had continued, to evaluate the level of experience of current SL practitioners, and to investigate the current indications for SL prescription. The aim of the present study was to analyze current characteristics of SL practitioners and explore trends in SL practice over 5 years.

Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The survey was designed and administered by the SCOPE study group using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture)7, 8 housed at The Ohio State University. The survey was available between November 8, 2019, and March 31, 2020. A complete copy of the survey is available in Supplemental Appendix 1.

As in the 2015 study, eye care practitioners who had demonstrated interest in specialty contact lenses were recruited for this study. Email invitations were sent to previous study participants who had agreed to be contacted for future studies and to members of the Scleral Lens Education Society. All attendees of the 2019 Summit of Specialty Contact Lenses and the 2020 Global Specialty Lens Symposium received email invitations from the conference organizers. Links to the survey were included in 2 online newsletters (I-site and the British Contact Lens Association) and were also posted in a private Facebook group for SL practitioners.

Practitioners who had completed at least 5 SL fits were included in this study. Data collected included country of residence, primary practice modality, year in which participants fit their first SL, setting in which participants fit their first SL (optometry school, residency, or clinical practice), estimated total number of SLs fit, estimated average number of SLs fit per month, and indications for SL wear.

Participants were divided into groups to allow for comparisons based on country of residence, mode of practice, and years of SL fitting experience. US-based practitioners were compared with non-US practitioners. University or academic institutions, hospitals, or industry were defined as academic practice, whereas private, group, or commercial practice modalities were defined as community practice. Participants who reported initially fitting SLs before or during 2014 were considered established and those who began fitting SLs in 2015 or later were considered new practitioners.

Statistical Analysis

The median and range for each group are reported. Categorical data are reported as frequency and proportion. Nonparametric comparisons for these groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum and Fisher exact tests. A P value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 922 practitioners responded to the survey. Of these, 65 reported prescribing fewer than 5 SLs, and 80 reported prescribing 5 or more SLs but did not respond to any other items; both of these groups were excluded from analysis. Responses from the remaining 777 participants were included in the analysis, although participants were not required to answer each question.

Of the 775 participants who indicated a country of residence, 63% (488) practiced in the US; Italy was identified as country of residence for 4.3% (33) participants, and 3.6% (28) participants reported residence in Canada. The remaining 226 participants represented 57 countries (complete data on country of residence is included in Supplemental Appendix 2). Most participants reported community practice as their primary practice modality (76%, 585/765); approximately one-fourth (24%, 180/765) reported practicing in an academic setting. Two-thirds of participants (66%, 494/749) were established SL practitioners, and approximately one-third (34%, 255/749) were new practitioners.

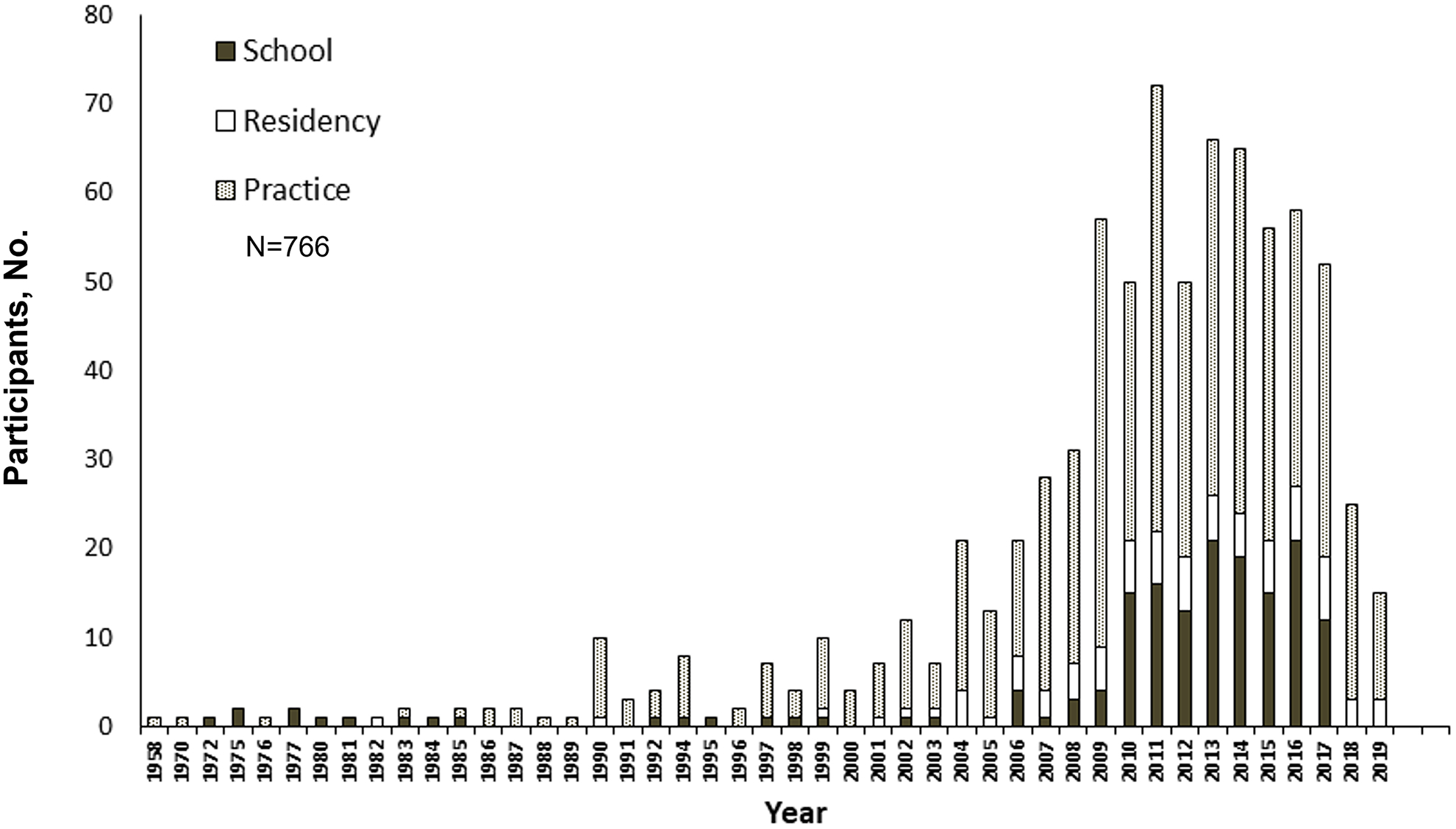

Participants were asked to identify the year and setting (optometry school, residency, clinical practice) of their first SL fit. Most participants (69%, 536/777) reported fitting their first SL while working in clinical practice at a mean of 12 years (range, 0–46 years; n=499) after graduation. Twenty-one percent (164) fit their first SL during optometry school, and 10% (77) fit their first SL during residency (Figure 1). The mean year of the first SL fit was 2012 (range, 1972–2019; n=766); 8% (6) of participants completed their first SL fit before 2000, 20% (154) between 2000 and 2009, and the remaining 72% (551) completed their first SL fit in 2010 or later. Participants were also asked to identify the year in which they completed their training. Seven percent of participants (49/750) graduated before 1980, 15% (116) graduated in the 1980s, 18% (136) graduated in the 1990s, 25% (188) graduated in the 2000s, and 35% (261) graduated in the 2010s (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Reported SL Fitting Experience (Year and Setting [School, Residency, and Practice]). Most first SL fits occurred in a practice setting. First SL fits during school increased around 2010 until 2017. Few participants reported initially fitting SLs during residency. SL indicates scleral lens.

Figure 2.

Reported Year of Graduation. From 2008 to 2017, there were more graduates; however, the number of graduates over those years was stable without a steady increase.

Although most US (60%, 291/481) and non-US practitioners (82%, 233/283) reported fitting their first SL when working in clinical practice, non-US practitioners were significantly more likely to report fitting SLs in practice rather than during optometric training (P<.001). Twenty-eight percent (134/481) of US practitioners reported completing their first SL fit during optometry school compared with only 10% (29/283) of non-US practitioners (P<.001). Similarly, 12% (56/481) of US practitioners completed their first SL fit during residency compared with 7% (21/283) of non-US practitioners (P<.001). Practitioners in academic settings were more likely to have fit their first SLs either in optometry school (28%, 51/180) or residency (16%, 29/180) than community providers (19% [122/585] and 8% [48/585], respectively; P<.001). Community practitioners (73%, 425/585) were more likely to have begun to fit SLs after completing their training than academic practitioners (56%, 100/180; P<.001). A slightly higher percentage of established practitioners (72%, 355/494) reported completing their first SL fitting in practice than did new practitioners (63%, 161/255; P=.04). More new practitioners completed their first SL fit during school (26%, 67/255) or residency (11%, 27/255) than established practitioners (19% [94/494] and 9% [45/494], respectively; P=.04).

The median number of SL patients per participant was 100 (range, 5–10,000; n=752) (Table 1). Thirteen percent (97/752) of participants had fit fewer than 10 patients, 30% (224) reported fitting 11 to 50 patients, and 31% (231) reported fitting 51 to 200 patients. Twenty-seven percent (200) of participants had fit 201 or more patients with SLs, and a subset of this group (11% [82]) had fit 500 or more patients (Figure 3). Participants practicing in academic settings had fit more patients (median, 150; range, 5–5,000; n=169) than community practitioners (median, 70; range, 10–10,000; n=571) (P<.001).

Table 1.

Number of Reported Total SL Fits for All Participants and by Groupa

| All groups | US | Non-US | Academic | Community | Established | New | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated number of total SL fits | |||||||

| No. | 752 | 463 | 276 | 169 | 571 | 476 | 249 |

| Median | 100 | 100 | 80 | 150 | 70 | 150 | 30 |

| Range | 5–10,000 | 5–10,000 | 5–5,000 | 5–5,000 | 10–10,000 | 5–10,000 | 5–1,500 |

| P value | .49 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| ≤10, No. (%) | 97 (13) | 54 (12) | 41 (15) | 11 (7) | 85 (15) | 28 (6) | 65 (26) |

| 11–50, No. (%) | 224 (30) | 142 (31) | 79 (29) | 40 (24) | 181 (32) | 111 (23) | 106 (43) |

| 51–200, No. (%) | 231 (31) | 146 (32) | 80 (29) | 59 (35) | 167 (29) | 158 (33) | 64 (26) |

| 201–500, No. (%) | 118 (16) | 71 (15) | 45 (16) | 34 (20) | 82 (14) | 179 (38) | 14 (6) |

| >500, No. (%) | 82 (11) | 50 (11) | 31 (11) | 25 (15) | 56 (10) | 78 (16) | 2 (1) |

| Estimated SL fits per month | |||||||

| No. | 757 | 468 | 276 | 173 | 572 | 487 | 243 |

| Median | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Range | 0–150 | 0–60 | 0–150 | 0–150 | 0–50 | 0–60 | 0–150 |

| P value | .41 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

Abbreviation: SL, scleral lens.

Academic and established practitioners completed more total fits and the highest number of new SL fits per month. Few participants in any group fit fewer than 10 or more than 500 SLs.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Participants by the Number of Completed Total Lens Fits. Of practitioners, 43% reported 50 or fewer SL fits, and 40% reported fitting between 91 and 500 SLs. SL indicates scleral lens.

Participants were also asked to estimate the average numbers of SL fits performed per month. The median number of new fits per month was 3 (range, 0–150; n=757). Most participants (88%, n=669) fit 10 or fewer SLs per month, 8% (n=61) fit 11 to 20 SLs per month, 3% (n=25) fit 21–50 SLs per month, and fewer than 1% (n=2) fit more than 50 SLs per month.

Estimated percentages of patients wearing SLs for various indications were provided by 684 participants. Corneal irregularity (CI) was the primary indication for SL wear (84%; range, 0%−100%; n=684), OSD was the second most common indication for SL wear (10%; range, 0%−93%), and uncomplicated refractive error (RE) was the least common indication for SL wear (2%; range, 0%−100%) (Table 2). CI was the most common indication for SL wear among all groups. Academic practitioners reported fitting a higher percentage of SLs for OSD than community practitioners (median, 15%; range, 0%−90%; vs median, 8%; range, 0%−100%) (P<.001). The percentage of SLs fit for uncomplicated RE was low among all groups, but non-US practitioners fit lenses for this indication more often than US practitioners (median, 3%; range, 0%−100%; vs median, 1%; range, 0%−48%, respectively) (P<.001).

Table 2.

Indications for SL Lens Weara

| Indication for SL fit | All groups (N=684) | US (n=434) | Non-US (n=238) | Academic (n=157) | Community (n=513) | Established (n=433) | New (n=232) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corneal irregularity | |||||||

| Median, % | 84 | 85 | 80 | 80 | 85 | 80 | 85 |

| Range, % | 0–100 | 0–100) | 0–100 | 10–100 | 0–100 | 0–100 | 0–100 |

| P value | .002 | <.001 | .07 | ||||

| Ocular surface disease | |||||||

| Median, % | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Range, % | 0–93 | 0–100 | 0–90 | 0–90 | 0–100 | 0–93 | 0–90 |

| P value | .60 | <.001 | .02 | ||||

| Uncomplicated refractive error | |||||||

| Median, % | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Range, % | 0–100 | 0–48 | 0–100 | 0–40 | 0–100 | 0–100 | 0–45 |

| P value | <.001 | .02 | .08 | ||||

Abbreviation: SL, scleral lens.

Corneal irregularity was the most common primary indication for SL wear overall and in every group of practitioners identified. Refractive error alone was a rare indication for SL wear overall and in every group of practitioners identified.

Discussion

During the past decade, there has been an increase in the number of publications and educational programs related to SL wear, suggesting growth in the SL market. Estimates of the number of patients fit with SLs more than doubled in 2020 compared with 2015: 84,735 SL wearers were reported (among 723 prescribers) in 2015 and 213,444 (among 781 prescribers) were reported in 2020.6 Although the percentage of practitioners who had fit 50 lenses or more increased (from 35% in 2015 to 57% in 2020), the percentage of practitioners who had fit 50 or fewer lenses decreased from 65% to 43% compared with the 2015 study. Data suggest that SL prescription could become concentrated toward high-volume practices. In both the original and current studies, practitioners who had fit larger numbers of lenses also reported fitting more lenses per month than their less prolific colleagues. This trend would widen the gap in the number of SLs fit between high- and low-volume prescribers. It is possible that sampling bias may have also contributed to this disparity; despite efforts to recruit similar populations in both the 2015 and 2020 surveys, cohorts of study participants were not identical.

The 2015 SCOPE study showed that the number of practitioners entering SL practice annually increased dramatically in the decade before the study. This finding is consistent with the increase in SL fits beginning in 2011, which was reported by Woods et al3 in 2020. Had this trend continued through 2020, one might have expected a corresponding increase in the number of practitioners who had fit only a small number of lenses, as new practitioners begin an SL practice. However, the percentage of practitioners who had fit 10 or fewer lenses actually decreased slightly in 2020 compared with 2015 (13% in 2020 to 21% in 2015). The current study suggests that the number of new SL providers entering the field annually stabilized over 5 years. The number of new graduates incorporating SLs into their practices also appears to be stabilizing or even decreasing. Both studies asked participants to provide their years of graduation or completion of training; in the 2015 study,6 2013 was the most commonly reported year of graduation, whereas more participants in the 2020 study reported graduating even earlier, in 2009. Although a proliferation of novel SL-related educational opportunities and publications in the early 2010s may have encouraged individuals graduating during that time to plan to incorporate SLs into their practices, the market reality is that SLs have largely remained a niche product whose use is still primarily limited to patients with CI and OSD. Market penetrance for SLs may be reaching a point of equilibrium, and patient demand for SLs may be able to be met by providers currently in practice.

Further comparisons between the original 2015 SCOPE study and the current survey suggest a global increase in the use of SLs. In this study, 63% of participants resided in the US compared with 72% of participants in the 2015 study. Sixty countries were represented in this study compared with 50 in the 2015 study. These changes could be due to more intentional distribution of the questionnaire to areas outside of the US, but they might also reflect that SLs are penetrating global markets. Interestingly, Woods et al3 surveyed contact lens practitioners in 66 countries over a 20-year period (2000–2019) and reported that Switzerland, rather than the US, had the highest number of SL fits. Differences in methods or emphasis of survey distribution may have contributed to this disparity. This survey specifically targeted practitioners with a demonstrated interest in SLs, whereas Woods et al3 surveyed a more general population of eye care providers. Regardless of geographic location, more practitioners who prescribe SLs appear to be working in community settings compared with 2015 (76% of 2020 participants, 63% of 2015 participants).6 Migration of SL practice into community settings along with the fact that the preponderance of SL literature originates from academic settings9 raises the possibility that published literature may not accurately describe the practice patterns of most SL providers. Although survey research has certain limitations, studies such as this do provide an opportunity to collect data from practitioners who may otherwise be underrepresented in SL-related literature.

Overall, indications for prescribing SLs have remained consistent compared with previous studies.6, 10–12 CI remains the most common indication for SL wear (means: 77% in 2020, 74% in 2015). OSD continues to be a distant second indication for SL fitting (means: 15% in 2020, 16% in 2015). The percentage of SLs fit for correction of RE declined from a mean of 10% in 2015 to a mere 2% in this study. SL manufacturers have expanded their market presence and have simplified the fitting process through advanced manufacturing and collaboration with companies developing scleral imaging technology, yet data from this survey suggest a trend away from using SLs in the absence of ocular pathology.

The goal of this study was to assess trends within the SL industry over a 5-year interval; thus, study design and survey items were purposefully similar to the 2015 survey. Although both studies recruited from similar populations (eye care providers with an interest in specialty contact lenses), responses were received from unique cohorts for each study. Beyond the impracticality of surveying the same cohort for both studies, this design recognizes fluidity within the SL community. As some practitioners step away from SLs, others initiate SL practice. Surveying similar, but not exactly the same, cohorts allows for assessment of trends within the entire SL industry, not simply in the practices of a limited number of individuals.

Both studies solicited responses from a large number of prescribers and therefore represent an overview of SL prescribing practices that cannot be gleaned from single-center studies. However, conclusions that can be drawn from this data are limited by both study and survey design. Sampling bias is always a possibility in survey-based research; it is possible that individuals who responded to this survey are not representative of the general population of SL providers. The survey did not require respondents to perform a formal chart review but simply asked them to estimate values based on their best recall. Data based on actual chart review may have been more accurate, but it is likely that fewer respondents would have taken the time to complete the survey had a chart review been required. The decision to allow respondents to progress through the survey without answering every item was also consciously made to encourage participation by as many prescribers as possible; requiring responses to every item would likely have limited participation. Although the survey was made available to an international audience, both the 2015 and 2020 surveys were available only in English. Despite its limitations, this study provides insight into growth and usage trends in SLs.

Global SL representation has increased since 2015. SLs continue to be primarily a therapeutic option for patients with CI. The use of SLs for RE alone has decreased. Current SL practitioners are more likely to have greater experience fitting SLs compared with practitioners in 2015, and the number of new SL practitioners entering practice annually may be stabilizing.

Supplementary Material

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

Contamac provided an unrestricted grant to the SCOPE study group to support survey development and distribution. Study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, and decision to submit the article for publication were completed by the authors independently.

This publication was supported, in part, by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant UL1 TR002733. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The study also received support from the National Eye Institute Center Core Grant P30 EY001792hT and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Abbreviations

- CI

corneal irregularity

- OSD

ocular surface disease

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- RE

refractive error

- SCOPE

Scleral Lenses in Current Ophthalmic Practice Evaluation

- SL

scleral lens

Footnotes

Declaration of interest:

Cherie B. Nau: None

Jennifer Harthan: Consulting for Allergan, Essilor, Euclid, International Keratoconus Academy, Metro Optics, Visioneering Technologies, Inc. Research for Bausch + Lomb, Kala Pharmaceuticals, Ocular Therapeutix, Metro Optics

Ellen Shorter: Research grant from Johnson & Johnson

Jennifer Fogt: Research funding from Nevakar, EyeNovia, Alcon, Innovega, Contamac. Consulting for Alcon and Contamac

Amy Nau: Paid lecturer for EyeEcco. Consulting for Oyster Point Pharmaceuticals

Alexander P. Hochwald: None

David O. Hodge: None

Muriel M. Schornack: None

References

- 1.Vincent SJ. The rigid lens renaissance: A surge in sclerals. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Apr 2018;41(2):139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Worp E, Bornman D, Ferreira DL, Faria-Ribeiro M, Garcia-Porta N, Gonzalez-Meijome JM. Modern scleral contact lenses: A review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Aug 2014;37(4):240–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods CA, Efron N, Morgan P, International Contact Lens Prescribing Survey C. Are eye-care practitioners fitting scleral contact lenses? Clin Exp Optom. Jul 2020;103(4):449–453. doi: 10.1111/cxo.13105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pullum KW, Whiting MA, Buckley RJ. Scleral contact lenses: the expanding role. Cornea. Apr 2005;24(3):269–77. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000148311.94180.6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shorter E, Harthan J, Nau CB, et al. Scleral Lenses in the Management of Corneal Irregularity and Ocular Surface Disease. Eye Contact Lens. Nov 2018;44(6):372–378. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nau CB, Harthan J, Shorter E, et al. Demographic Characteristics and Prescribing Patterns of Scleral Lens Fitters: The SCOPE Study. Eye Contact Lens. Sep 2018;44 Suppl 1:S265-S272. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. Apr 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. Jul 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Efron N, Jones LW, Morgan PB, Nichols JJ. Bibliometric analysis of the literature relating to scleral contact lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Aug 2021;44(4):101447. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2021.101447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harthan JS, Schornack M, Nau CB, Nau AC, Fogt JS, Shorter ES. Current U.S. based optometric scleral lens curricula and fitting recommendations: SCOPE educators survey. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Jun 2021;44(3):101353. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2020.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macedo-de-Araujo RJ, van der Worp E, Gonzalez-Meijome JM. Practitioner Learning Curve in Fitting Scleral Lenses in Irregular and Regular Corneas Using a Fitting Trial. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5737124. doi: 10.1155/2019/5737124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schornack M, Nau C, Nau A, Harthan J, Fogt J, Shorter E. Visual and physiological outcomes of scleral lens wear. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Feb 2019;42(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.