The intersection of racism, classism, gender discrimination, and criminal justice involvement in the United States continues to manifest syndemic inequalities. In their work, Alang et al. (p. S29) describe police brutality and the adverse outcomes produced in women’s lives over time. Drawing on seminal work on intersectionality and public health,1,2 Alang et al. argue for in-depth consideration of how gender and racism influence police brutality and the impact of interactions with the police on the health and well-being of racialized women. Personal and vicarious witnessing of police brutality and other adverse criminal justice contacts has been shown to affect women and Black individuals.3,4 Moreover, Black and Latina women are significantly more likely to fear police brutality than White women, and this anticipatory fear is linked with depressed moods.5 Furthermore, evidence suggests that even having a family member incarcerated during a woman’s childhood is associated with a higher likelihood of depressed mood in adulthood.5

The interaction between the criminal justice system and racial minority status is complex, as evidenced by results on the impact of a partner’s incarceration on racially minoritized women and consequences for their own life. In the case of Black women, evidence suggests that partner incarceration is linked with substance use.6 Although the mechanisms through which partner incarceration leads to drug use need further exploration, the knitted relationship between gender and race can lead to heightened vulnerability and inequality.6 Moreover, fear of harassment from police reduces access to syringe service programs and other harm reduction programs among racialized people who use drugs and may contribute to rising overdoses and fear of overdoses among minoritized groups, contributing to health disparities.7–9

Although minoritization based on race and sex complicates health and social equity, the impact of adverse criminal justice contacts on women receives less attention than the impact on racialized men, eliciting calls for gender-inclusive racial justice initiatives.1 Notwithstanding criminal justice–related cases of physical and sexual exploitation of women, few studies have quantified the prevalence and magnitude of such incidents.

Research by Cottler et al.10 showed that among a sample of 318 women involved in the criminal justice system, 25% reported police sexual misconduct. Of these women, 96% reported having sex with an on-duty officer, 77% reported repeated exchanges, and 31% reported being raped by police.10 In a study by Stringer et al., a smaller yet sizable percentage of women involved in the criminal justice system (14%) reported police sexual misconduct, significantly increasing depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among victims.11 An especially vulnerable group of women are those who engage in sex work, have a history of multiple arrests, and are affected by the syndemic nature of substance use and poverty, as they may be coerced into sexual activities in exchange for favors from police officers.10–12 The few studies quantifying adverse criminal justice outcomes and participant insights gain validation with US Department of Justice reports and the never-ending stream of media stories.13,14

The lack of measurement of these issues in large, representative samples limits our understanding of the impact of adverse criminal justice contacts on women’s health. In a brief descriptive analysis, we used data from the 2016 to 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (n = 65 184) to further highlight the effects of racism, gender, class, and criminal justice on women’s health and well-being. We explored the impact of ever being booked in prison (a measure of criminal justice involvement) among White and Black women and how the disparities observed in the initial measure transformed when poverty status (a proxy for social class) was incorporated into the analysis.

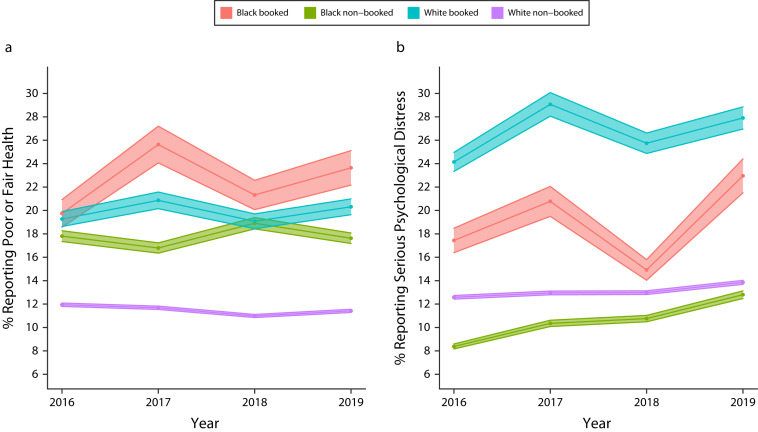

Panel A of Figure 1 shows that Black women who had been booked in prison reported worse health than any other group. They were followed by White women who had been booked and Black women who had never been booked. Interestingly, White women who had contact with the criminal justice system reported poor or fair self-reported health at levels closer to those of Black women who did not have contact with the criminal justice system than White women who reported no contact. The patterns observed in Figure 1 underscore how racial minority status and criminal justice involvement adversely affect health. White women who had never been booked in prison reported lower levels of poor or fair self-reported health than the other groups included in the analysis.

FIGURE 1—

Differences in (a) Poor or Fair Health and (b) Serious Psychological Distress Between White and Black Women According to Whether They Had Ever Been Booked in Prison: United States, 2016–2019

Note. The analysis evaluated women aged 18 years or older.

Source. National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2016–2019.

We also explored the association between self-reported health and racial minority status, class, and criminal justice involvement categories (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org). Disparities in self-reported health status were more evident and magnified when income level was considered. We acknowledge the various measurement issues arising from self-reported health, but it is still one of the most widely collected and used health outcomes and is associated with physiological dysregulation, other adverse health outcomes, and mortality.15,16

Panel B of Figure 1 shows corresponding trends for serious psychological distress. The descriptive analysis showed that White women who had been booked in prison reported worse serious psychological distress than the other groups. They were followed by Black women who had been booked in prison and White women who had not been booked. Black women who had never been booked in prison reported serious psychological distress at lower levels than the other groups assessed included in the study. When income level was considered, this pattern shifted. The odds of meeting the threshold for serious psychological distress were lower among White women who had never been booked and who lived above the poverty threshold than among most of the other groups. The only exception was Black women who had not been booked and lived above the poverty threshold (Figure A).

These results add quantification to some of Alang et al.’s arguments and corroborate previous research on the negative impact of adverse criminal justice contacts on psychological health.5 Mattingly et al.3 found that, among a large sample of racially/ethnically diverse young adults in California, distress regarding police brutality rose from 2017 to 2020, with Hispanic and Black individuals having the highest distress. Distress over police brutality was linked with substance use in racialized groups. Overall, the constant exposure to police brutality on media channels and physical witnessing of these incidents by racialized communities, along with personal police contact, produce vicarious and collective trauma.4,17 There is a disproportionate police presence in racialized communities, making anticipatory fear of adverse criminal justice contacts pronounced.4,5

In recent years, the constant stream of media stories and videos of police brutality victims and adverse criminal justice outcomes has illuminated pervasive racism in the United States, leading to calls for reformation within the criminal justice system. Research by Reingle et al.18 showed that every increase in police academy graduating class size was linked with a 9% increase in the odds of discharge for police sexual misconduct, and having a graduating class above 35 was associated with more than four times the odds of discharges than smaller classes. These results imply that solutions to adverse criminal justice contacts may include limiting police academy class sizes and instituting steady hiring practices, rather than intensive hiring periods, to ensure proper training of all members. Alang et al. note that “power and the benefits of power are what keep oppressive systems in place.” Acknowledging and addressing the effects of these intersectional social factors will be key to improving women’s health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (award K01DA051715; principal investigator: A. A. Jones). The Population Research Institute (PRI) provided infrastructure for the data analysis. The PRI is supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD041025), the Social Science Research Institute, and Pennsylvania State University.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See also Alang et al., p. S29.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crenshaw K, Ritchie A, Anspach R, Gilmer R, Harris L.2022. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4235&context=faculty_scholarship

- 2.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattingly DT, Howard LC, Krueger EA, Fleischer NL, Hughes-Halbert C, Leventhal AM. Change in distress about police brutality and substance use among young people, 2017–2020. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;237:109530. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turney K. Depressive symptoms among adolescents exposed to personal and vicarious police contact. Soc Ment Health. 2021;11(2):113–133. doi: 10.1177/2156869320923095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alang S, Haile R, Mitsdarffer ML, VanHook C. Inequities in anticipatory stress of police brutality and depressed mood among women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s40615-022-01390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruns A, Lee H. Partner incarceration and women’s substance use. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82(4):1178–1196. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones AA, Schneider KE, Mahlobo CT, et al. Fentanyl overdose concerns among people who inject drugs: the role of sex, racial minority status, and overdose prevention efforts. Psychol Addict Behav. 2022 doi: 10.1037/adb0000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones AA, Park JN, Allen ST, et al. Racial differences in overdose training, naloxone possession, and naloxone administration among clients and nonclients of a syringe services program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;129:108412. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strathdee SA, Beletsky L, Kerr T. HIV, drugs and the legal environment. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(suppl 1):S27–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cottler LB, O’Leary CC, Nickel KB, Reingle JM, Isom D. Breaking the blue wall of silence: risk factors for experiencing police sexual misconduct among female offenders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):338–344. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stringer KL, Marotta P, Goddard-Eckrich D, et al. Mental health consequences of sexual misconduct by law enforcement and criminal justice personnel among black drug-involved women in community corrections. J Urban Health. 2020;97(1):148–157. doi: 10.1007/s11524-019-00394-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones AA, Dyer TV, Das A, Lasopa SO, Striley CW, Cottler LB. Risky sexual behaviors, substance use, and perceptions of risky behaviors among criminal justice involved women who trade sex. J Drug Issues. 2019;49(1):15–27. doi: 10.1177/0022042618795141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones AA, O’Leary CC, Striley CW, et al. Substance use, victimization, HIV/AIDS risk, and recidivism among females in a therapeutic justice program. J Subst Use. 2018;23(4):415–421. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2018.1436604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Justice. 2022. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/04/ferguson_police_department_report.pdf

- 15.Santos-Lozada AR, Howard JT. Using allostatic load to validate self-rated health for racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Biodemography Soc Biol. 2018;64(1):1–14. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2018.1429891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(3):307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herschlag G, Kang HS, Luo J, et al. 2022. http://arxiv.org/abs/1801.03783

- 18.Reingle Gonzalez JM, Bishopp SA, Jetelina KK. Rethinking police training policies: large class sizes increase risk of police sexual misconduct. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016;38(3):614–620. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]