Abstract

Objective

To investigate the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) during childbirth in Luxembourg from women's perspectives.

Methods

Women giving birth in facilities in Luxembourg between March 1, 2020, and July 1, 2021, answered a validated online WHO standards‐based questionnaire as part of the multicountry IMAgINE EURO study. Descriptive and multivariate quantile regression analyses were performed.

Results

A total of 493 women were included, representing 5.2% of women giving birth in the four maternity hospitals in Luxembourg during the study period. Most quality measures suggested high QMNC, although specific gaps were observed: 13.4% (n = 66) of women reported not being treated with dignity, 9.1% (n = 45) experienced abuse, 42.9% (n = 30) were not asked for consent prior to instrumental vaginal birth, 39.3% (n = 118) could not choose their birth position, 27% (n = 133) did not exclusively breastfeed at discharge (without significant differences over time), 20.5% (n = 101) reported an insufficient number of healthcare professionals, 20% (n = 25) did not receive information on the newborn after cesarean, and 41.2% (n = 203) reported lack of information on newborn danger signs before discharge. Multivariate analyses highlighted higher reported QMNC indexes among women born outside Luxembourg and delivering with a gynecologist, and significantly lower QMNC indexes in women with the highest education levels and those delivering in the hospital offering some private services.

Conclusions

Despite maternal reports suggesting an overall high QMNC in Luxembourg, improvements are needed in specific aspects of care and communication, mostly related to maternal autonomy, respect, and support, but also number and competencies of the health workforce.

Keywords: birth, breastfeeding, childbirth, COVID‐19, IMAgiNE EURO, Luxembourg, maternal health, newborn health, quality of care

Synopsis

Women giving birth in Luxembourg during the 16 months of the COVID‐19 pandemic reported gaps in quality of maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth.

1. INTRODUCTION

Luxembourg is a small country in Europe, with 634 700 inhabitants and 6460 infants born to residents per year (2020). 1 It operates a compulsory social health insurance (SHI) system, covering the majority of maternity costs. 2 , 3 All women in Luxembourg consult with obstetrician/gynecologists (OB/GYNs) as their main healthcare providers during pregnancy, rather than midwives, and attending five prenatal visits to an OB/GYN is required by the State to receive a prenatal allowance. 4 , 5 In addition, most of the out‐of‐hospital midwifery prenatal and postnatal services are only reimbursed upon presentation of a medical prescription 6 , 7 (medical prescription in Luxembourg means a prescription by a medical doctor for medicines, laboratory tests, other diagnostic tests, physiotherapy, or for midwifery care). Maternal care is provided by OB/GYNs working mostly in private practice and contracted for birth assistance by one of the maternity hospitals. Women usually opt to give birth in the hospital where “their” doctor, with whom they have a long‐standing relationship, can be present for birth. 3 The four maternity hospitals in Luxembourg all provide care that is reimbursed. Reimbursed care is also provided by one hospital that was privately founded but operates within the SHI system, albeit retaining certain private connotations related to the previous name of the facility and the offer of some first‐class superior rooms. SHI covers stay in a two‐person room, but all hospitals also offer single rooms. The single room choice implies additional formal fees that are not covered by the SHI for the stay and for the doctor's extra compensation. The overnight presence of the partners of birthing women also bears extra costs. There are less than 0.25% planned home births per year. 8

The health workforce is marked by strong dependence on neighboring countries: around two‐thirds of nurses and one‐quarter of doctors practicing in Luxembourg live outside the country. 2 Furthermore, around 47.2% of inhabitants hold a foreign nationality. 1 For 46.5% of infants born in Luxembourg neither of the parents has Luxembourg nationality. 1 Given the high volume of the workforce commuting daily from outside countries, around 10% of births in Luxembourg are to parents not residing in the country, which combines to give a total of 7108 infants born per year, according to the last national estimates in 2019 (unpublished perinatal statistic of the Ministry of Health).

The COVID‐19 pandemic affected Luxembourg from March 2020 onward, with a sharp increase in deaths registered from October 2020. 9 , 10 However, during the pandemic no official national recommendations were issued as a guidance for hospitals on how to organize maternity care in the country, resulting in a variety of unpublished policies that varied from hospital to hospital and over time. 10 Previous preliminary studies conducted in the early phases of the pandemic reported better access to health services and quality of care in Luxembourg compared with other countries. 11 , 12 Nonetheless, Luxembourg did not participate in the WHO survey on continuity of essential health services, therefore information on the resilience of the health system during the pandemic is limited. 13 While there have been reports of deterioration of mental health indicators in the general population, 14 data focusing on maternal and perinatal outcomes during the pandemic are still lacking in Luxembourg compared with other countries, even though this information has crucial public health implications. 15

Although some data on the views of service users on aspects of maternity care in Luxembourg have been previously published by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), no previous studies have reported maternal perspectives gathered through a comprehensive set of measures describing the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) in the country. 16 , 17

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a set of standards and quality measures for improving the QMNC. 18 The IMAgiNE EURO study is a multicountry project, including partners from numerous countries of the WHO European Region, which developed a questionnaire aimed at collecting the perspective of women on a key set of WHO standards‐based quality measures. The questionnaire was validated and used as an online survey. 19 , 20 The aim of the present study was to investigate QMNC during childbirth from the perspectives of women who gave birth in Luxembourg during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional study and is reported according to the STROBE guidelines and checklist (supporting information Table S1). 21

Women aged 18 years and older who gave birth in Luxembourg between March 1, 2020, and July 1, 2021, were invited to participate in an online survey. Women who gave birth outside the hospital setting were excluded.

The process of questionnaire development, validation, and previous use has been reported elsewhere. 20 , 22 Briefly, the questionnaire included 40 questions (each on one single quality measure), equally distributed across four domains: provision of care, experience of care, availability of human and physical resources, and key organizational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic. The 40 quality measures contributed to a QMNC index, with higher scores indicating higher adherence to WHO standards. 18 Basic sociodemographic information was also collected.

The questionnaire was made available in 23 languages, and women were invited to complete the survey in their preferred language. The survey was promoted through a predefined dissemination plan, using the following main approaches: posters and flyers made visible in hospitals, social media, websites of national networks (e.g. mothers' groups and NGOs), and radio interviews.

Data were analyzed in line with previous publications of the IMAgiNE EURO network. 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 Briefly, for the primary analysis, suspected duplicates and questionnaires missing 20% or more answers on 45 key variables were excluded. A descriptive analysis was performed, calculating absolute frequencies and percentages for each variable, as well as assessing the distribution of different languages chosen to answer the questionnaire.

For women providing data on all quality measures, a QMNC index was calculated based on the predefined criteria. 19 The QMNC index could range from 0–100 in each of the four domains, with the total ranging from 0–400. The QMNC indexes are presented as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) because they are not normally distributed. In addition to the primary analysis, two sensitivity analyses were conducted: (1) including only women who answered 100% of the 45 key variables; and (2) including women with up to 90% missing answers on 45 key variables, as has been done by similar studies. 19

We developed multivariable regression models with the QMNC index as the dependent variable and sociodemographic variables (i.e. parity, woman giving birth in the same country she was born, type of facility, maternal age, maternal educational level, year of birth), mode of birth, and presence of an OB/GYN directly assisting childbirth as independent variables. We conducted a multivariable quantile regression with robust standard errors (SEs) and we modeled the median, the 0.25th and 0.75th quantile, given statistical evidence of heteroskedasticity for parity, mode of birth, place of birth of the mother (Breusch‐Pagan/Cook‐Weisberg test P < 0.05, H0: homoskedasticity). The categories with the highest frequency were used as reference.

A subgroup analysis of women born in the country and women not born in the country was conducted to evaluate the differences in sociodemographic characteristics, quality measures, and the QMNC indexes using a χ2 test and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test.

Two additional exploratory analyses were also conducted. We analyzed whether there were differences between primiparous and multiparous women in their evaluation of the impact of COVID‐19 on access to antenatal care, barriers to accessing the facility, and perceived quality of care (three indicators in the domain of key organizational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic) using a χ2 test. Furthermore, we analyzed changes in the quality measures related to exclusive breastfeeding at discharge over time (three time periods, reflecting the subsequent waves of COVID‐19 in Luxembourg: March 2020 to June 2020; July 2020 to December 2020; January 2021 to June 2021) with a Cochran–Armitage trend test.

A two‐tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE version 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

2.1. Ethics statement

The IMAgiNE EURO study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the coordinating center: IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo” Trieste (IRB‐BURLO 05/2020 15.07.2020). The survey was an online anonymous questionnaire that woman could decide to join on a voluntary basis; no data elements that could disclose maternal identity were collected, answers were recorded directly into a centralized platform hosted in Italy, and no data were treated in Luxembourg, so no further ethical approval was required in Luxembourg. The survey was conducted according to the rules of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Prior to participation, women were informed of the objectives and methods of the study, including their rights to decline participation, and each provided consent before responding to the questionnaires. Data transmission and storage were secured by encryption.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of respondents

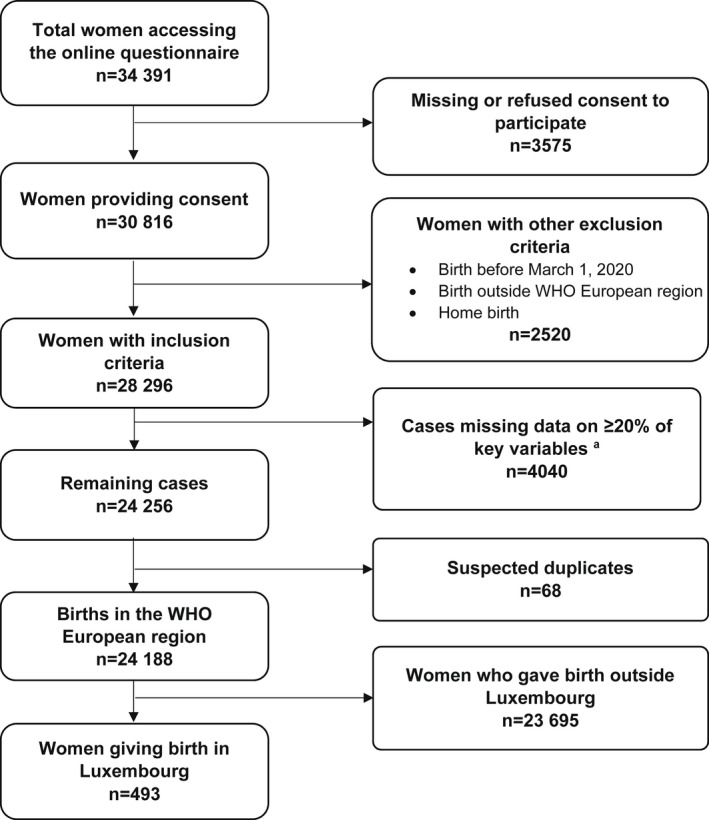

Of 34 391 women accessing the online questionnaire in all participating countries, 28 296 women fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and responses from 493 women giving birth in Luxembourg were analyzed after data cleaning (Figure 1). The sample accounted for 5.2% of total births expected in Luxembourg in the study period (unpublished perinatal statistics 2019 of the Ministry of Health). The German questionnaire was chosen by 55.2% (n = 272) of women, 26.8% (n = 132) chose the French, and the rest (18.0%, n = 89) opted for one of the other available languages during the study period (supporting information Table S2).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram. aPercentage of missing data for each woman was calculated over mandatory questions (n = 45)

Overall, most women (92.5%, n = 456) were aged between 25 and 39 years and had a high level of education (72.4%, n = 357 with a university degree or higher); 56.0% (n = 276) were primiparous (Table 1). Overall, 34.5% (n = 170) of women were not born in Luxembourg. Frequencies of spontaneous vaginal birth (SVB) and instrumental vaginal birth (IVB) were 60.9% (n = 300) and 14.2% (n = 70), respectively, while frequencies for cesarean during labor, elective, and emergency cesarean before labor occurred were 10.8% (n = 53), 10.5% (n = 52), and 3.7% (n = 18), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Overall (n = 493) No. (%) | Women born in Luxembourg a (n = 314) No. (%) | Women not born in Luxembourg a (n = 170) No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of birth | ||||

| 2020 | 414 (84.0) | 270 (86.0) | 144 (84.7) | 0.898 |

| 2021 | 67 (13.6) | 43 (13.7) | 24 (14.1) | 0.702 |

| Missing | 12 (2.4) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.2) | 0.251 |

| Maternal age, year | ||||

| 18–24 | 9 (1.8) | 6 (1.9) | 3 (1.8) | >0.99 |

| 25–30 | 136 (27.6) | 102 (32.5) | 34 (20.0) | 0.004 |

| 31–35 | 218 (44.2) | 141 (44.9) | 77 (45.3) | 0.934 |

| 36–39 | 102 (20.7) | 57 (18.2) | 45 (26.5) | 0.032 |

| ≥40 | 19 (3.9) | 8 (2.5) | 11 (6.5) | 0.034 |

| Missing | 9 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Maternal educational level b | ||||

| Less than high school | 21 (4.2) | 19 (6.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0.010 |

| High school | 106 (21.5) | 84 (26.8) | 22 (12.9) | <0.001 |

| University degree | 159 (32.3) | 111 (35.4) | 48 (28.2) | 0.112 |

| Postgraduate degree/Master/ Doctorate or higher | 198 (40.2) | 100 (31.8) | 98 (57.6) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 9 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Maternal parity | ||||

| 1 | 276 (56.0) | 193 (61.5) | 83 (48.8) | 0.007 |

| >1 | 207 (42.0) | 121 (38.5) | 86 (50.6) | 0.011 |

| Missing | 10 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.351 |

| Type of facility where the birth occurred | ||||

| Public | 398 (80.7) | 257 (81.8) | 141 (82.9) | 0.804 |

| Private | 86 (17.4) | 57 (18.2) | 29 (17.1) | 0.804 |

| Missing | 9 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Labor | ||||

| Yes | 423 (85.8) | 272 (86.6) | 142 (83.5) | 0.355 |

| No | 70 (14.2) | 42 (13.4) | 28 (16.5) | 0.355 |

| Mode of birth | ||||

| Spontaneous vaginal c | 300 (60.9) | 183 (58.3) | 111 (65.3) | 0.131 |

| Instrumental vaginal | 70 (14.2) | 46 (14.6) | 22 (12.9) | 0.606 |

| Emergency cesarean during labor | 53 (10.8) | 43 (13.7) | 9 (5.3) | 0.004 |

| Emergency cesarean before going into labor | 18 (3.7) | 10 (3.2) | 8 (4.7) | 0.399 |

| Elective cesarean | 52 (10.5) | 32 (10.2) | 20 (11.8) | 0.594 |

| Health professional directly assisting childbirth d | ||||

| Midwife | 465 (94.3) | 304 (96.8) | 161 (94.7) | 0.371 |

| Nurse | 140 (28.4) | 86 (27.4) | 54 (31.8) | 0.364 |

| Student | 89 (18.1) | 64 (20.4) | 25 (14.7) | 0.157 |

| Obstetrics registrar/medical resident (under postgraduate training) | 41 (8.3) | 14 (4.5) | 27 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| Obstetrician/Gynecologist | 434 (88.0) | 281 (89.5) | 153 (90.0) | 0.985 |

| I do not know (healthcare providers did not introduce themselves) | 10 (2.0) | 5 (1.6) | 5 (2.9) | 0.332 |

| Other | 32 (6.5) | 20 (6.4) | 12 (7.1) | 0.921 |

| Other characteristics | ||||

| Multiple birth | 6 (1.2) | 3 (1.0) | 3 (1.8) | 0.428 |

| Newborn admitted to neonatal intensive care unit | 26 (5.3) | 21 (6.7) | 5 (2.9) | 0.125 |

| Women admitted to intensive care unit | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.351 |

| Stillbirth | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

Information regarding maternal country of birth is missing for 9 women (1.8%).

Wording on education levels agreed among partners during the Delphi. Questionnaire translated and back‐translated according to ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation Principles of Good Practice.

Spontaneous vaginal births include all noninstrumental vaginal births independently of spontaneous or induced onset of labor.

More than one possible answer.

3.2. WHO standards‐based quality measures

Key results for the domain of provision of care (Table 2) were as follows: 10.4% (n = 44) of women who experienced labor and 11.4% (n = 14) who had a cesarean complained of inadequate pain relief; 30% (n = 21) of women with IVB reported fundal pressure during childbirth; 15% (n = 45) of women with SVB had an episiotomy; 0.6% (n = 3) of women did not experience skin‐to‐skin contact with their newborn; 5.3% (n = 26) reported no early breastfeeding; 27.0% (n = 133) were not exclusively breastfeeding at discharge, and 16.2% (n = 80) reported inadequate breastfeeding support.

TABLE 2.

| Overall (n = 493) No. (%) | Women born in Luxembourg (n = 314) No. (%) | Women not born in Luxembourg (n = 170) No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of care | ||||

| 1. No pain relief during labor (SVB, IVB, EC before labor) | 44/423 (10.4) | 27/272 (9.9) | 16/142 (11.3) | 0.789 |

| 2. Mode of birth | ||||

| 2a. SVB | 300 (60.9) | 183 (58.3) | 111 (65.3) | 0.131 |

| 2b. IVB | 70 (14.2) | 46 (14.6) | 22 (12.9) | 0.606 |

| 2c. EC after labor | 53 (10.8) | 43 (13.7) | 9 (5.3) | 0.004 |

| 2d. EC before labor | 18 (3.7) | 10 (3.2) | 8 (4.7) | 0.399 |

| 2e. Elective cesarean | 52 (10.5) | 32 (10.2) | 20 (11.8) | 0.594 |

| 3a. Episiotomy (in SVB) | 45/300 (15.0) | 28/183 (15.3) | 13/111 (11.7) | 0.389 |

| 3b. Fundal pressure (in IVB) | 21/70 (30.0) | 15/46 (32.6) | 5/22 (22.7) | 0.403 |

| 3c. No pain relief after cesarean | 14/123 (11.4) | 8/85 (9.4) | 6/37 (16.2) | 0.278 |

| 4. No skin‐to‐skin contact | 3 (0.6) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.672 |

| 5. No early breastfeeding | 26 (5.3) | 21 (6.7) | 4 (2.4) | 0.043 |

| 6. Inadequate breastfeeding support | 80 (16.2) | 53 (16.9) | 26 (15.3) | 0.748 |

| 7. No rooming‐in | 29 (5.9) | 20 (6.4) | 9 (5.3) | 0.783 |

| 8. Not allowed to stay with the baby as wished | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.351 |

| 9. No exclusive breastfeeding at discharge | 133 (27.0) | 92 (29.3) | 38 (22.4) | 0.124 |

| 10. No immediate attention when needed | 101 (20.5) | 68 (21.7) | 30 (17.6) | 0.353 |

| Experience of care | ||||

| 1a. No freedom of movements during labor | 60/423 (14.2) | 41/272 (15.1) | 19/142 (13.4) | 0.639 |

| 1b. No consent requested for vaginal examination before prelabor cesarean | 13/70 (18.6) | 7/42 (16.7) | 6/28 (21.4) | 0.616 |

| 2a. No choice of birth position (in SVB) | 118/300 (39.3) | 69/183 (37.7) | 47/111 (42.3) | 0.430 |

| 2b. No consent requested (for IVB) | 30/70 (42.9) | 17/46 (37.0) | 13/22 (59.1) | 0.085 |

| 2c. No information on newborn (after cesarean) | 25/123 (20.3) | 13/85 (15.3) | 12/37 (32.4) | 0.031 |

| 3. No clear/effective communication from HCP | 81 (16.4) | 50 (15.9) | 28 (16.5) | 0.979 |

| 4. No involvement in choices | 107 (21.7) | 68 (21.7) | 37 (21.8) | 1.000 |

| 5. Companionship not allowed | 104 (21.1) | 74 (23.6) | 27 (15.9) | 0.062 |

| 6. Not treated with dignity | 66 (13.4) | 49 (15.6) | 16 (9.4) | 0.077 |

| 7. No emotional support | 97 (19.7) | 65 (20.7) | 30 (17.6) | 0.492 |

| 8. No privacy | 50 (10.1) | 36 (11.5) | 13 (7.6) | 0.241 |

| 9. Abuse (physical/verbal/emotional) | 45 (9.1) | 27 (8.6) | 17 (10.0) | 0.729 |

| 10. Informal payment | 41 (8.3) | 33 (10.5) | 6 (3.5) | 0.012 |

| Availability of physical and human resources | ||||

| 1a. No timely care by HCPs at facility arrival | 54 (11.0) | 41 (13.1) | 10 (5.9) | 0.021 |

| 2. No information on maternal danger signs | 145 (29.4) | 92 (29.3) | 51 (30.0) | 0.955 |

| 3. No information on newborn danger signs | 203 (41.2) | 130 (41.4) | 70 (41.2) | 1.000 |

| 4. Inadequate room comfort and equipment | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| 5. Inadequate number of women per rooms | 21 (4.3) | 19 (6.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0.003 |

| 6. Inadequate room cleaning | 6 (1.2) | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0.670 |

| 7. Inadequate bathroom | 8 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0.786 |

| 8. Inadequate partner visiting hours | 112 (22.7) | 77 (24.5) | 31 (18.2) | 0.141 |

| 9. Inadequate number of HCPs | 42 (8.5) | 24 (7.6) | 16 (9.4) | 0.616 |

| 10. Inadequate HCP professionalism | 8 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) | 2 (1.2) | 1.000 |

| Reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 | ||||

| 1. Difficulties in attending routine antenatal visits | 178 (36.1) | 117 (37.3) | 57 (33.5) | 0.473 |

| 2. Any barriers in accessing the facility | 151 (30.6) | 106 (33.8) | 42 (24.7) | 0.050 |

| 3. Inadequate info graphics | 8 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) | 2 (1.2) | 1.000 |

| 4. Inadequate ward reorganization | 82 (16.6) | 55 (17.5) | 25 (14.7) | 0.505 |

| 5. Inadequate room reorganization | 92 (18.7) | 60 (19.1) | 28 (16.5) | 0.552 |

| 6. Lacking one functioning accessible hand‐washing station | 26 (5.3) | 19 (6.1) | 6 (3.5) | 0.326 |

| 7. HCP not always using PPE | 27 (5.5) | 21 (6.7) | 5 (2.9) | 0.093 |

| 8. Insufficient HCP number | 101 (20.5) | 72 (22.9) | 27 (15.9) | 0.086 |

| 9. Communication inadequate to contain COVID‐19‐related stress | 124 (25.2) | 77 (24.5) | 44 (25.9) | 0.826 |

| 10. Reduction in QMNC due to COVID‐19 | 194 (39.4) | 139 (44.3) | 49 (28.8) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: EC, emergency cesarean; HCP, healthcare professional; IVB, instrumental vaginal birth; PPE, personal protective equipment; QMNC, quality of maternal and newborn care; SVB, spontaneous vaginal birth.

All the indicators in the domains of provision of care, experience of care, and resources are directly based on WHO standards.

Indicators with a specified denominator identified (e.g. 3a, 3b) were tailored to take into account different mode of birth (i.e. spontaneous vaginal, instrumental vaginal, and cesarean). These were calculated on subsamples (e.g. 3a was calculated on spontaneous vaginal births; 3b was calculated on instrumental vaginal births).

Indicator 6 in the domain of reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 was defined as: at least one functioning and accessible hand‐washing station (near or inside the room where the mother was hospitalized) supplied with water and soap or with disinfectant alcohol solution.

In the domain of experience of care: 14.2% (n = 60) of women reported no freedom of movements during labor; 39.3% (n = 118) reported no choice of birth position during SVB; 18.6% (n = 13) reported that no consent was asked for vaginal examinations before prelabor cesarean, while 42.9% (n = 30) reported no consent request for IVB; 21.7% (n = 107) stated that they were not involved in choices around care or treatment and 20.3% (n = 25) did not receive information on the newborn after cesarean. Lack of clear or effective communication from healthcare professionals (HCPs) was experienced by 16.4% (n = 81) of women and 10.1% (n = 50) experienced limitations on privacy. Overall, 19.7% (n = 97) of the women did not feel emotionally supported during childbirth, 13.4% (n = 66) reported not being treated with dignity, and 9.1% (n = 45) experienced physical, verbal, or emotional abuse. The presence of a companion of choice was not permitted for 21.1% (n = 104) of women and 22.7% (n = 112) reported inadequate visiting hours; 8.3% (n = 41) had to make additional payments.

In the domain of availability of resources: 11.0% (n = 54) did not receive timely care at facility level at arrival; none reported inadequate room comfort, while a small percentage reported too many women per room (4.3%, n = 21), inadequate bathrooms (1.6%, n = 8), and inadequate cleaning (1.2%, n = 6). Lack of information on maternal and newborn danger signs was reported by 29.4% (n = 145) and 41.2% (n = 203), respectively.

In the domain of organizational changes due to COVID‐19, 36.1% (n = 178) of women had difficulties attending routine antenatal visits and 30.6% (n = 151) encountered barriers in accessing the facility. Inadequate ward reorganization and inadequate room reorganization were mentioned by 16.6% (n = 82) and 18.7% (n = 92), respectively. Insufficient numbers of HCPs to guarantee adequate assistance despite the COVID‐19 pandemic was reported by 20.5% (n = 101), while a reduction in quality of care due to COVID‐19 was expressed by 39.4% (n = 194). Communication on how to contain COVID‐19‐related stress was rated inadequate by 25.2% (n = 124) of women. The lack of a hand‐washing station or HCPs not using personal protective equipment (PPE) was reported by 5.3% (n = 26) and 5.5% (n = 27), respectively.

3.3. QMNC index and multivariate analysis

The total reported median QMNC index was 355 (IQR 335–375), with lower scores observed in the domain of availability of physical and human resources (median 85, IQR 75–95) compared with other domains (P < 0.001, Table 3). Findings of the sensitivity analyses were substantially similar to the findings of the primary analysis (supporting information Tables S3–S6 and supporting information Figures S1 and S2).

TABLE 3.

QMNC index and subdomains

| Overall (n = 391) Median [IQR] | Women born in Luxembourg (n = 241) Median [IQR] | Women not born in Luxembourg (n = 146) Median [IQR] | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total QMNC index | 355 [335–375] | 355 [330–370] | 365 [340–380] | 0.005 |

| Subdomains | ||||

| Provision of care | 90 [85–95] | 90 [85–95] | 90 [85–95] | 0.464 |

| Experience of care | 90 [85–100] | 90 [80–100] | 92.5 [85–100] | 0.474 |

| Availability of physical and human resources | 85 [75–95] | 85 [75–95] | 90 [75–100] | 0.034 |

| Reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 | 90 [82.5–100] | 90 [80–95] | 95 [85–100] | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; QMNC, quality of maternal and newborn care.

Multivariate analysis showed that when adjusting the QMNC indexes for other variables, in general only minor differences among groups were observed (Table 4). Significantly higher QMNC indexes were reported on selected centiles for women who were not born in Luxembourg (+8.9 and + 10 in the 50th and 75th centile respectively, P = 0.019 and P = 0.006 respectively) and had an OB/GYN present at the time of delivery (+10 in the 25th centile, P = 0.32). Significantly lower QMNC indexes were reported by women delivering in the hospital with some private offers (−40 in the 25th centile, P = 0.01) and by women with the highest education levels (−10 in the 25th centile, P = 0.05).

TABLE 4.

Multivariate quantile regression estimates (n = 384)

| 25th centile | 50th centile (median) | 75th centile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Maternal parity | ||||||

| 1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| >1 | 10 (−3.9; 23.9) | 0.159 | −1.7 (−9.0; 5.7) | 0.655 | 0 (−7.2; 7.2) | >0.999 |

| Women born in Luxembourg | ||||||

| Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| No | 5 (−3.3; 13.3) | 0.237 | 8.9 (1.5; 16.3) | 0.019 | 10 (2.9; 17.1) | 0.006 |

| Type of facility | ||||||

| Public | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Private | −40 (−70.3; −9.7) | 0.010 | −11.7 (−24.6; 1.2) | 0.076 | −5 (−17.6; 7.6) | 0.437 |

| Maternal age, year a | ||||||

| 18–30 | −5 (−19.9; 9.9) | 0.510 | −7.2 (−14.7; 0.3) | 0.060 | −5 (−13.7; 3.7) | 0.261 |

| 31–35 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| >35 | 0 (−9.0; 9.0) | >0.999 | 3.9 (−5.6; 13.4) | 0.421 | 0 (−7.7; 7.7) | >0.999 |

| Maternal educational level a | ||||||

| High school or lower | −5 (−15.1; 5.1) | 0.329 | 2.2 (−5.2; 9.6) | 0.557 | −5 (−14.0; 4.0) | 0.277 |

| University degree | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Postgraduate degree/master/ doctorate or higher | −10 (−20.0; 0.1) | 0.051 | 2.8 (−5.3; 10.8) | 0.497 | 0 (−7.8; 7.8) | >0.999 |

| Year of birth | ||||||

| 2020 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2021 | −5 (−19.0; 9.0) | 0.481 | 1.7 (−11.9; 15.2) | 0.809 | 5 (−2.8; 12.8) | 0.207 |

| Mode of birth | ||||||

| Spontaneous vaginal b | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Instrumental vaginal | −10 (−24.8; 4.8) | 0.186 | −9.4 (−18.9; 0.0) | 0.050 | −10 (−20.8; 0.8) | 0.069 |

| Cesarean | −15 (−33.2; 3.2) | 0.106 | −7.2 (−14.7; 0.02) | 0.057 | 0 (−12.3; 12.3) | >0.999 |

| OB/GYN directly assisting the birth | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 10 (0.9; 19.1) | 0.032 | 9.4 (−2.5; 21.4) | 0.121 | 5 (−3.1; 13.1) | 0.226 |

| Intercept | 335 (318.5; 351.5) | <0.001 | 350.6 (337.4; 363.7) | <0.001 | 370 (359.6; 380.4) | <0.001 |

Some categories of age and educational level were collapsed due to low number.

Spontaneous vaginal births include all noninstrumental vaginal births independently of spontaneous or induced onset of labor.

3.4. Subgroup and exploratory analyses

At subgroup analysis, women not born in the country were typically older than women born in Luxembourg, had a higher education level (57.6% vs 31.8% held a postgraduate degree, P < 0.001), and had higher parity (50.6% vs 38.5% were multiparous, P = 0.011) (Table 1). There were only a few differences in the reported quality measures between the two groups (Table 2): women not born in Luxembourg more frequently lacked information on their newborns after cesarean (32.4% vs 15.3%, P = 0.031), while women born in Luxembourg more frequently reported informal payments (10.5% vs 5.9%, P = 0.012), lack of timely care (13.1% vs 5.9%, P = 0.021), barriers to accessing the health facilities (33.8% vs 24.7%, P = 0.050), and reduced quality of care due to COVID‐19 (44.3% vs 28.8%, P = 0.001). Women not born in Luxembourg reported a significantly higher total QMNC index (365, IQR 340–380) compared with those born in Luxembourg (355, IQR 330–370) (P = 0.005), as well as a higher QMNC index in the subdomains of availability of physical and human resources (P = 0.034) and of reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 (P = 0.003) (Table 3).

Multiparous women were more likely to report barriers to accessing the facility during the pandemic compared with primiparous women (36.2% vs 26.1%, respectively; P = 0.016) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Evaluation of the impact of COVID‐19 on care received, by parity a

| Primiparas (n = 276) No. (%) | Multiparas (n = 207) No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 | |||

| Difficulties in attending routine antenatal visits | 101 (36.6) | 73 (35.3) | 0.763 |

| Any barriers in accessing the facility | 72 (26.1) | 75 (36.2) | 0.016 |

| Reduction in QMNC due to COVID‐19 | 108 (39.1) | 80 (38.7) | 0.914 |

Missing data for 10 women.

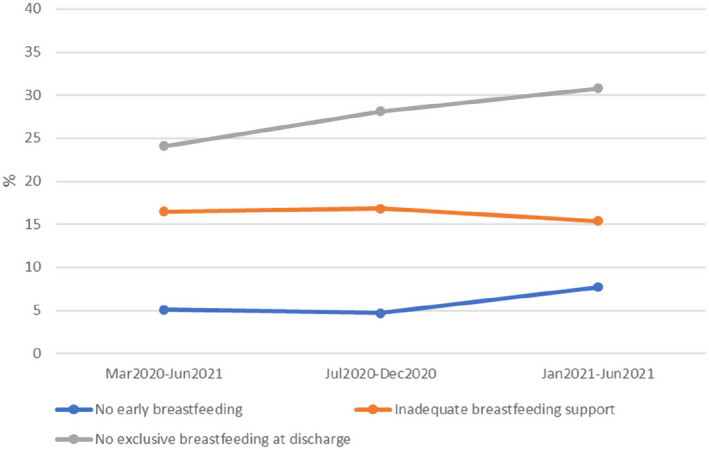

No statistically significant differences were found when comparing breastfeeding indicators over the three waves of the pandemic (Table 6 and Figure 2).

TABLE 6.

Breastfeeding indicators over time a

| March 2020–June 2020 (n = 158) No. (%) | July 2020 – December 2020 (n = 256) No. (%) | January 2021 – June 2021 (n = 65) No. (%) | Trend test P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate breastfeeding support | 26 (16.5) | 43 (16.8) | 10 (15.4) | 0.901 |

| No exclusive breastfeeding at discharge | 38 (24.1) | 72 (28.1) | 20 (30.8) | 0.255 |

| No early breastfeeding | 8 (5.1) | 12 (4.7) | 5 (7.7) | 0.560 |

14 additional women with missing date of birth.

FIGURE 2.

Breastfeeding indicators over time

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first study in Luxembourg to use a WHO standards‐based validated questionnaire to comprehensively document QMNC during the COVID‐19 pandemic, collecting the perspectives of women as key service users. Most quality measures suggested high QMNC in Luxembourg, although specific gaps were observed, mostly related to maternal autonomy, respect, and support, but also to number of healthcare professionals. Multiparous women reported more barriers to accessing the facility during the pandemic compared with primiparous women—a result of comparison of experiences before the pandemic. It is important that measures to keep healthcare facilities accessible during further pandemics are implemented.

While some of the findings of this study related to quality of care may have been exacerbated by the pandemic, for others there is no proof that the observed gaps in QMNC are related to the pandemic, or rather, there is some previous evidence of similar findings; for example, the observed rate of women not exclusively breastfeeding at discharge (27%) is in line with a previous national survey where 29% of all breastfed babies received supplementary feeding during the hospital stay. 24 The data underscore that, for breastfeeding success, skin‐to‐skin contact and rooming‐in are not enough. Implementation and revitalization of the whole Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) package is needed, as well as higher competencies of HCPs through continuous education efforts and improvements in initial training, with special focus on detecting good latch and swallowing, counseling, and reducing supplementary feeding. 25 Notably, in our study, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge, as well as reports of adequate breastfeeding support did not change significantly over time, suggesting that these results on breastfeeding rates may not be due to the pandemic.

In relation to measures of experience of care, particularly regarding aspects of communication and autonomy, our findings are in line with previous studies conducted in Luxembourg. 26 , 27 A previous online survey with 136 postpartum women revealed that 43% of the women reported that doctors did not take adequate time for explanations and 37% were not ready to talk about alternatives to the recommended care, while 34% of women reported not receiving adequate counseling on the advantages or risks of the proposed treatments. 26 In another online survey carried out in 2013–2014, only 58.4% of women reported having received sufficient information on standard procedures. 27

Findings of this study (e.g. those related to women's autonomy, involvement in care choices, consent request for procedures, dignity, privacy, and lack of information on danger signs for women and newborns) are in line with findings from other European countries. 28 , 29 , 30 However, it strongly suggests that the Luxembourg law on patients' rights adopted in 2014 is still not fully implemented. 31 HCP practices such as lack of communication and consent request, and not providing information or immediate attention for patients, may be the result of large gaps in effective provider supervision as well as in training on patients' rights and communication strategies. 32 This study highlighted several areas in which vast improvements are warranted, for the health and well‐being of women and infants. Further studies should explore health workers' perspectives as an integrative view of QMNC. 33 While it is true that Luxembourg shows some of the best indicators of QMNC across Europe, decision‐makers at all levels should address the existing gaps. 19 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40

Strengths of this study include the use of a standardized validated questionnaire, based on the WHO standards. 18 , 21 , 22 The sample also appropriately captures the multiethnic population in Luxembourg, and the expected age of women. 1

Limitations of the multicountry IMAgiNE EURO survey have been noted elsewhere. 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 Specific limitations to this study in Luxembourg are as follows: the sampled population included a greater number of highly educated and primiparous women and a smaller number of women who delivered by cesarean compared with the average expected for women giving birth in the country. 1 However, it is difficult to predict in which direction this may have affected results on the reported QMNC, as women with a lower level of education may have had better or worse experiences than women in the sample. Data reflect maternal perception of care, which may be affected by culture and expectations; future studies should aim to triangulate the data using other methods and perspectives. Improvements in the future might occur related to the July 2021 document authored by the Woman's Health Working Group of the Scientific Council of Health of Luxembourg recommending the implementation of the WHO standards for QMNC, 41 as well as the reimbursement of new acts and services carried out by midwives, effective February 1, 2022, allowing a midwifery care model to start. 42

In conclusion, this study adds to previous evidence of findings related to QMNC in the Luxembourg context. It highlights the need for further efforts regarding the number and competencies of the health workforce. Competencies include provider knowledge of women's rights, of effective communication during care including the need to disclose adequate information about newborns, and implementation of adequate practices of informed consent as well as greater respect for women's choices. While WHO standards should be monitored regularly to assess progress over time—including collecting the views of the users in independent studies—decision‐makers at all levels of the healthcare system, including individual HCPs, should take immediate action to ensure high QMNC for all women and newborns.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ML conceived the IMAgiNE EURO study, with inputs from MA, BC, IM, EPV. MA and BT supported the process of data collection, with inputs from BC and EPV. All authors conceived the analyses presented in this paper. IM analyzed data, with major inputs from all other authors. MA, ML, and FC wrote the first draft, which major inputs from all authors. AL reviewed the draft and provided some unpublished national statistics. All authors approved the final version.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

IMAgiNE EURO study group

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Amira Ćerimagić, NGO Baby Steps, Sarajevo; Croatia: Daniela Drandić, Roda – Parents in Action, Zagreb; Magdalena Kurbanović, Faculty of Health Studies, University of Rijeka, Rijeka; France: Rozée Virginie, Elise de La Rochebrochard, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Research Unit, Institut National d'Études Démographiques (INED), Paris; Kristina Löfgren, Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative (IHAB); Germany: Céline Miani, Stephanie Batram‐Zantvoort, Lisa Wandschneider, Department of Epidemiology and International Public Health, School of Public Health, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld; Italy: Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Benedetta Covi, Ilaria Mariani, Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste; Sandra Morano, Medical School and Midwifery School, Genoa University, Genoa; Israel: Ilana Chertok, Ohio University, School of Nursing, Athens, Ohio, USA and Ruppin Academic Center, Department of Nursing, Emek Hefer; Rada Artzi‐Medvedik, Department of Nursing, The Recanati School for Community Health Professions, Faculty of Health Sciences at Ben‐Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev; Latvia: Elizabete Pumpure, Dace Rezeberga, Gita Jansone‐Šantare, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Riga Stradins University and Riga Maternity Hospital, Riga; Dārta Jakovicka, Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Rīga; Agnija Vaska, Riga Maternity Hospital, Riga; Anna Regīna Knoka, Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Rīga; Katrīna Paula Vilcāne, Faculty of Public Health and Social Welfare, Riga Stradins University, Riga; Lithuania: Alina Liepinaitienė, Andželika Kondrakova, Kaunas University of Applied Sciences, Kaunas; Marija Mizgaitienė, Simona Juciūtė, Kaunas Hospital of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas; Luxembourg: Maryse Arendt, Professional Association of Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg; Barbara Tasch, Professional Association of Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, KannerKlinik, Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg, Luxembourg; Norway: Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, Sigrun Kongslien, Department of Community Medicine, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø; Eline Skirnisdottir Vik, Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen; Poland: Barbara Baranowska, Urszula Tataj‐Puzyna, Maria Węgrzynowska, Department of Midwifery, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw; Portugal: Raquel Costa, EPIUnit ‐ Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto; Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional, Porto; Lusófona University/HEI‐Lab: Digital Human‐environment Interaction Labs, Lisbon; Catarina Barata, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa; Teresa Santos, Universidade Europeia, Lisboa and Plataforma CatólicaMed/Centro de Investigação Interdisciplinar em Saúde (CIIS) da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon; Carina Rodrigues, EPIUnit ‐ Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto and Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional, Porto; Heloísa Dias, Regional Health Administration of the Algarve; Romania: Marina Ruxandra Otelea, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest and SAMAS Association, Bucharest; Serbia: Jelena Radetić, Jovana Ružičić, Centar za mame, Belgrade; Slovenia: Zalka Drglin, Barbara Mihevc Ponikvar, Anja Bohinec, National Institute of Public Health, Ljubljana; Spain: Serena Brigidi, Department of Anthropology, Philosophy and Social Work, Medical Anthropology Research Center (MARC), Rovira i Virgili University (URV), Tarragona; Lara Martín Castañeda, Institut Català de la Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya; Sweden: Helen Elden, Verena Sengpiel, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg; Karolina Linden, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg; Mehreen Zaigham, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institution of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Lund and Skåne University Hospital, Malmö; Switzerland: Claire de Labrusse, Alessia Abderhalden, Anouck Pfund, Harriet Thorn, School of Health Sciences (HESAV), HES‐SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Lausanne; Susanne Grylka‐Baeschlin, Michael Gemperle, Antonia N. Mueller, Research Institute of Midwifery, School of Health Sciences, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur.

DISCLAIMER

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Rome, Italy, in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste, Italy. We would like to thank all women who took their time to respond to this survey despite the burden of the COVID‐19 pandemic. We thank our colleagues from the professional organization of lactation consultants and the midwifery association as well as Initiativ Liewensufank, the involved maternity hospitals, and others who helped in the dissemination of the invitation to participate in the survey. Special thanks to the IMAgiNE EURO study group for their contribution to the development of this project and support for this manuscript.

Arendt M, Tasch B, Conway F, et al. Quality of maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth in Luxembourg during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Results of the IMAgiNE EURO study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl. 1):113‐125. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14473

Funding informationThis work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Rome ‐ Italy, in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste ‐ Italy

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. STATEC . Luxembourg in figures 2021. https://statistiques.public.lu/fr/publications/series/luxembourg‐en‐chiffres/2021/luxembourg‐en‐chiffres.html. Page 11–13. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 2. European Commission . State of health in the EU. Luxembourg Country Health Profile 2021. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/docs/librariesprovider3/country‐health‐profiles/chp2021pdf/luxemburg‐countryhealthprofile2021.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2022

- 3. The Government of the Grand‐Duchy of Luxembourg . Health benefits in Luxembourg. https://guichet.public.lu/en/citoyens/sante‐social/remboursement‐frais‐medicaux/prestations‐sante‐resident/prise‐en‐charge‐resident.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 4. The Government of the Grand‐Duchy of Luxembourg . Prenatal medical check‐ups. https://cae.public.lu/en/allocations/primes‐de‐naissance/avant‐la‐naissance‐‐conditions.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 5. The Government of the Grand‐Duchy of Luxembourg . Prenatal allowance. https://guichet.public.lu/en/citoyens/famille/parents/allocation‐naissance/allocation‐naissance.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 6. CNS . Midwives. https://cns.public.lu/en/assure/vie‐privee/sante‐prevention/prestations‐paramedicales/sages‐femmes.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 7. CNS . Nomenclature and tariffs of midwifery procedures and services. (Nomenclature et tarifs des actes et services des sages‐femmes) https://cns.public.lu/en/legislations/alsf/cns‐alsf‐tableau.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 8. Luxembourg Institute of Health , The Government of the Grand‐Duchy of Luxembourg. Surveillance of perinatal health in Luxembourg. https://susana.lu/Web/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=cil7ZpOgOgU%3d&tabid=116. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 9. The Government of the Grand‐Duchy of Luxembourg . Covid data Luxembourg. https://covid19.public.lu/fr/graph.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 10. Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg . Fathers allowed to come to some ultrasound. https://www.chl.lu/fr/actualites/les‐papas‐peuvent‐a‐nouveau‐assister‐a‐echographie‐avril‐2021. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 11. Burzyński M, Machado J, Aalto A, et al. COVID‐19 crisis management in Luxembourg: insights from an epidemionomic approach. Econ Hum Biol. 2021;43:101051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bauer J, Brüggmann D, Klingelhöfer D, et al. Access to intensive care in 14 European countries: a spatial analysis of intensive care need and capacity in the light of COVID‐19. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2026‐2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization . National pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID‐19 pandemic 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐2019‐nCoV‐EHS‐continuity‐survey‐2021.1. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 14. Ribeiro F, Schröder VE, Krüger R, Leist AK, CON‐VINCE Consortium . The evolution and social determinants of mental health during the first wave of the COVID‐19 outbreak in Luxembourg. Psychiatry Res. 2021;303:114090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Semaan A, Audet C, Huysmans E, et al. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID‐19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lauterbour‐Rohla C, Lehners‐Arendt M, Thommes‐Bach C. Having a child in Luxembourg (Kinderkriegen in Luxemburg). Initiativ Liewensufank asbl; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Initiativ Liewensufank . Parents magazines. https://www.liewensufank.lu/de/baby‐info‐magazine/. Accessed January 17, 2022

- 18. World Health Organization . Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. WHO; 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511216. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 19. Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. Quality of facility‐based health care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: online survey investigating the maternal perspective in 12 countries of the WHO European region. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;13:100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lazzerini M, Argentini G, Mariani I, et al. WHO standards‐based tool to measure women's views on the quality of care around the time of childbirth at facility level in the WHO European region: development and validation in Italy. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e048195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453‐1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, Giusti A, Pessa Valente E; for the IMAgiNE EURO Study Group. Quality of care at childbirth: Findings of IMAgiNE EURO in Italy during the first year of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;157:405‐417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zaigham M, Linden K, Sengpiel V, et al; IMAgiNE EURO Study Group . Large gaps in the quality of healthcare experienced by Swedish mothers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional study based on WHO standards. Women Birth. 2022; 35:619‐627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Desroches S, Brochmann C, Wagener Y, Lehners S. Nutrition of our babies (L'alimentation de nos bébés Etude Alba 2015) Ministry of Health, Health directorate. (Ministère de la Santé, Direction de la Santé) 2017. https://gimb.public.lu/fr/publications/2015/ALBA.html. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 25. World Health Organization , United Nations Children's Fund. Implementation guidance: protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services: the revised Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative. WHO; 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513807. Accessed January 16, 2022.

- 26. Arendt M. Are women treated as responsible patients? (Werden Frauen als mündige Patientinnen behandelt?) p.16–17 babyinfo 2/2017. https://www.liewensufank.lu/wp‐content/uploads/2017/08/2017_04_baby‐info.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 27. Heltemes B, Arendt M. C‐section, information and consent (Kaiserschnittentbindung‐ Informationen und Einwilligung zu Massnahmen) p.23–25 babyinfo 3/2016. https://www.liewensufank.lu/wp‐content/uploads/2017/08/2016_07_baby‐info.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 28. Drandić D, Drglin Z, Mihevc Ponkivar B et al. Women’s perspectives on the quality of hospital maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study in Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, and Bosnia‐Herzegovina. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):54‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hersoug Nedberg I, Skirnisdottir Vik E, Kongslien S, et al. Quality of health care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Results from the IMAgiNE EURO study in Norway and trends over time. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):85‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Costa R, Barata C, Dias H et al. Regional differences in the quality of maternal and neonatal care during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Portugal: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):137‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. The Government of the Grand‐Duchy of Luxembourg. Patient rights and obligations . Luxembourg law on patients' rights. 2014. https://guichet.public.lu/en/citoyens/sante‐social/droits‐devoirs‐patient/droits‐devoirs‐patient/droits‐obligations‐patient.html. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 32. Valente EP, Mariani I, Covi B, Lazzerini M. Quality of Informed Consent Practices around the Time of Childbirth: A Cross‐Sectional Study in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19:7166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Valente EP, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. WHO Standards‐based questionnaire to measure health workers’ perspective on the quality of care around the time of childbirth in the WHO European region: development and mixed‐methods validation in six countries. BMJ Open. 2022; 12:e056753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. De Rekeneire N, Weber G, Barre J, Billy A, Couffignal S, Lecomte A. Monitoring of perinatal health in Luxembourg . Report on births from 2014–2015‐2016 and changes since 2001. (Surveillance de la Santé Périnatale au Luxembourg. Rapport sur les naissances 2014–2015‐2016 et leur évolution depuis 2001.) Ministry of Health and Luxembourg Institute of Health. https://sante.public.lu/fr/publications/s/surveillance‐sante‐perinatale‐lux‐2014‐2015‐2016.html. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 35. Anonymous . Caesarean: Yes? No? Maybe? Ministry of Health and CRP Santé. https://sante.public.lu/fr/publications/c/cesarienne‐fr‐de‐pt‐en/index.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 36. Alkerwi A, Leite S, Pivot D, Debacker M, Weber G. Analysis and evaluation of the potential impact of recommendations of the scientific council on health of 9th of July 2014 related to scheduled CS. (Analyse et évaluation de l'impact potentiel des recommandations du Conseil scientifique du domaine de la santé, du 9 juillet 2014, en matière des indications de la césarienne programmée à terme au Luxembourg). Service épidémiologie et statistique. Direction de la santé. March 2021. https://sante.public.lu/dam‐assets/fr/publications/r/rapport‐pratique‐cesarienne/dossier‐evaluation‐de‐pratique‐cesariennes.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 37. Scientific Council on Health . Indications for scheduled caesarean section at term in Luxembourg. (Indications de la césarienne programmée à terme au Luxembourg. Conseil scientifique du domaine de santé), (2014, updated in 2021). https://conseil‐scientifique.public.lu/fr/publications/perinat/indications‐de‐la‐cesarienne‐programmee‐a‐terme‐au‐Luxembourg‐version‐courte‐maj‐2021.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 38. Anonymous . Rose Revolution Luxembourg. https://business.facebook.com/The‐Roses‐Revolution‐Luxembourg‐1101609286516795/. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 39. Schmoetten I. Our birth culture needs feminism . (Eis Gebuertskultur brauch Feminismus) Interview. January 2022. https://www.100komma7.lu/program/episode/381553/202201061240‐202201061243?fbclid=IwAR2XP5b6Vl6UJXDAw7e5ajONaPpmaV2rXapOXg0Q12WPpuG8HFXts7J_EFw. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 40. Khosla R, Zampas C, Vogel JP, Bohren MA, Roseman M, Erdman JN. International human rights and the mistreatment of women during childbirth. Health Hum Rights. 2016;18:131‐143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scientific Council on Health . Obstetrical and gynecological violence (July 2021) (Violences gynécologiques et obstétricales). https://conseil‐scientifique.public.lu/fr/publications/perinat/violences‐gynecologiques‐et‐obstetricales.html. Accessed September 19, 2022.

- 42. CNS . Nomenclature of acts and services of midwives (Nomenclature des actes et services des sages‐femmes). https://cns.public.lu/fr/legislations/alsf/cns‐alsf‐tableau.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.