Summary

A ‘new’ way of dreaming has emerged during the pandemic, enhancing the interest of psychological literature. Indeed, during the years of the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), many studies have investigated dream‐related phenomena and dreaming functions. Considering the constant and rapid emergence of new results on this topic, the main aim of this study was to create an ‘observatory’ on the short‐ and long‐term consequences of the COVID‐19 pandemic on dreaming, by means of a living systematic review. The baseline results are presented, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses statement guidelines, to identify and discuss existing studies about dreams and dreaming during the COVID‐19 pandemic published until February 2022. Web of Science, Embase, EBSCO, and PubMed were used for the search strategy, yielding 71 eligible papers included in the review. Our results show: (a) a more intense oneiric activity during lockdown; (b) changes in dreaming components (especially dream‐recall and nightmare frequency); (c) a particular dreaming scenario (‘pandemic dreams’); (d) an alteration of the dreaming–waking‐life continuum and a specific function of dreaming as emotional regulator. Findings suggest that monitoring changes in dreaming provides important information about psychological health and could also contribute to the debate on the difficulties of dreaming, as well as sleeping, in particular during and after a period of ‘collective trauma’.

Keywords: dreaming, dreams, living systematic review, pandemic, psychological health

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the strain of coronavirus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), especially the lockdown periods in which restrictions included limitations in contact with others, the incentive to work from home, and the shutdown of public places and activities, entailed complex challenges for the population across the world, increasing psychological distress (Di Blasi et al., 2021; Every‐Palmer et al., 2020; Nishimi et al., 2022).

Although psychological clinical symptoms seemed to partially decrease after lockdowns (Aknin et al., 2022), the investigation of the long‐term effects of the pandemic on psychological health is still ongoing.

The COVID‐19 pandemic affected the daytime life and mental health of individuals, and even modified and impacted night‐time patterns involving sleeping and dreaming.

Studies have suggested the presence of quarantine‐induced circadian modifications (da Silva et al., 2020) and sleep pattern changes (Beck et al., 2021), enhanced sleep problems, sleep disturbances, and poor sleep quality worldwide (Johnson et al., 2022; Lin, Wang, et al., 2021; Yuksel et al., 2021). According to the literature, widespread sleep disruption, so‐called ‘COVID‐somnia’ (Gupta & Pandi‐Perumal, 2020) reflected the decrease in psychological health observed in the general population during the lockdowns (Yuksel et al., 2021). Even after the lockdowns, unlike insomnia and anxiety, poor sleep and depression persisted in the general population (Salfi et al., 2021). In addition, the persisting insomnia was considered as an index of higher psychological dysfunction during the pandemic waves (Bi & Chen, 2022).

Moreover, other authors have shown an increase in sleep duration during the acute phases of pandemic (Bottary et al., 2020). However, night‐time phenomena did not only concern sleeping, but also dreaming. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, a growing interest in dreaming emerged in the literature, concerning the so‐called ‘pandemic dreams’. In pandemic dreams, the hypothesis of dreaming–waking life continuity that shows how waking experiences and concerns are reflected in dream contents, was widely confirmed (Barrett, 2001, 2020).

A recent narrative review was published on dreaming during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Gorgoni et al., 2022), which reported an interesting organisation of the main findings of some studies, showing a change in the phenomenology of dreams during the pandemic. However, a systematic review identifying and screening all the papers presented in the main scientific databases in the psychological field about dreaming and dreams during the COVID‐19 pandemic, both in the general and the clinical population, is lacking.

Hence, the aim of this study was to monitor the main findings on dreaming during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the general and the clinical population, presenting the first phase of a living systematic review (LSR) that allows us to create an ‘observatory’ on the short‐ and long‐term consequences of the COVID‐19 pandemic on dreaming.

METHODS

General procedure

A LSR represents a recent innovative method aimed at adapting the systematic review to the new needs of scientific literature, generating a continuous update of current research into a specific topic of interest (Elliott et al., 2017). It arose from medical research, although some applications in the psychological field have emerged in the past few years, especially for tracing the psychological effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the population (Dong et al., 2021).

This type of method was considered optimal for the aim of the present study because it allows us to create an ‘observatory’ about dreaming and the COVID‐19 pandemic, responding to the constant growth of publications in this field that will probably see new papers for the following 2 years, at least. A LSR will allow us to update the current results provided by the scientific literature with emerging data in order to respond to the uncertainty and heterogeneity that characterise some dimensions of this area of study, as a previous narrative review has shown (Gorgoni et al., 2022).

Here, the LSR baseline study is presented. The future phases of this LSR will include an updating of the results in March 2023 and a further update in March 2024. This update schedule was organised considering the authors' resources and a prediction of the future publications on dreaming and the COVID‐19 pandemic through the forthcoming years.

Search strategy

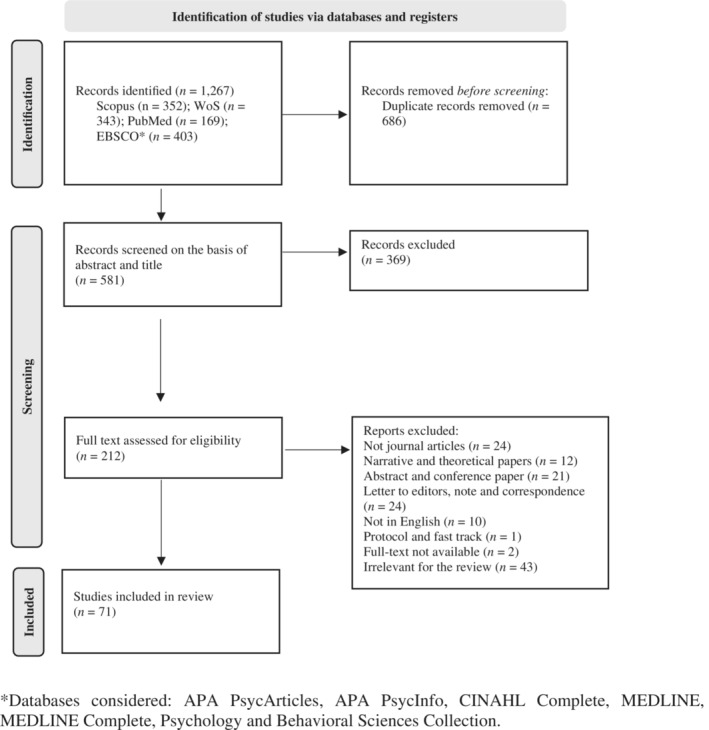

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021) were used to perform the current systematic review. Published papers were retrieved up to the February 7, 2022, from the following electronic databases: Web of Science, Embase, EBSCO (APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo; Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection; MEDLINE) and PubMed. The following string of key‐terms was used for the searching process of titles and abstracts: (dream* OR nightmare*) AND (‘SARS CoV 2’ OR ‘COVID‐19’ OR ‘COVID’ OR coronavirus OR pandemic*).

Selection strategy

Journal articles that reported new and original results about several aspects of dreaming during the spread of COVID‐19, including nightmare features (frequency and content), dream features (dream‐recall frequency [DRF], content of dreams, and COVID‐19‐related dreams); with a publication date from September 1, 2019, to February7, 2022; written in English were included in the present review. Papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria, such as letters to editors, data reports, abstracts, conference papers, narrative and theoretical papers, papers on sleep disturbances that did not include results on dreaming phenomena, and not in English, were excluded from the review.

The selection strategy followed the steps suggested by the PRISMA statement (2020). First, all duplicate papers were deleted. Secondly, studies were screened based on abstracts and titles. Finally, considering the inclusion criteria, the full texts of the papers were reviewed.

Selected studies

Electronic database searches produced a total of 1,267 papers (Figure 1). Among them, 686 duplicates were found and deleted. After the screening of titles and abstracts, 369 studies were excluded, and 212 studies full texts were screened. In the full‐text screening step, 125 papers were excluded: 24 were not journal articles; 12 were narrative or theoretical papers; 21 were abstracts and conference papers; six were letters to editors, notes, and correspondences; two did not have a full text available; 10 were not in English; one was an experimental protocol; 44 did not report results on dreaming phenomena.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow‐diagram. *Databases considered: APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE, MEDLINE Complete, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection.

In the end a total of 71 studies were included in the review. Information extracted from each included article were as follows: author(s) and year of publication; country; type of study (qualitative and/or quantitative; cross‐sectional or longitudinal); characteristics of participants (sample type and size); periods of data collection (lockdown, partial lockdown, first or second year of the COVID‐19 pandemic); dreaming features or phenomena accessed in the article (DRF, nightmare frequency [NF], dreams content, dream narrative features, COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency and content); main findings related to dreaming phenomena during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the studies

| Study | Country | Study type | Participants, N | Pandemic phase | Instruments | Dreaming phenomena | Results | Level of quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alfonsi et al. (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Longit. study |

147 adults |

Lockdown follow‐up: 4 months after lockdown |

Sleep diary | DRF | DRF increased at T2 and decreased after lockdown, unlike the trend of sleep patterns | B |

| 2. Aragona et al. (2022) | Italy |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

28 immigrants in poor socio‐economic conditions in treatment for PTSD | Lockdown |

Item 2 (B2) of clinician administered PTSD |

NF | NF remained quite stable after lockdown in PTSD patients and no difference between worsened and stable/improved patients emerged | B |

| 3. Barrett (2020) | Multi‐country (N = 6) |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional Control with baseline data |

2,888 adults Controls: Hall and Von de Castle baseline data |

1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐19‐related dream content |

Comparing to the normative values, Death was the most increased theme. Changing in dream theme category frequency (e.g., more negative emotions and lower positive emotions) was observed especially in women. Continuity hypothesis was supported |

B |

| 4. Bhat et al. (2021) | India |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

310 pharmacy students | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | NF | NF was high during lockdown | B |

| 5. Borghi et al. (2021) | Italy |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

761 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | Dream content | The most frequent categories in dreams were open and closed places, relationality, blocked and persecutory actions, emotions, and process categories. Themes predicted positive and negative emotions, depression, and anxiety. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 6. Bruni, Breda, et al. (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Cross‐sectional Control group |

Caregivers of 100 ASD, 236 ADHD patients, and 340 healthy children, and adolescents (controls) |

Lockdown | SDSC modified | NF | Among the three groups, NF was higher in ADHD group than ASD and control one, before and during the pandemic. On the other side, NF increased during lockdown only for subjects in the control group | B |

| 7. Bruni, Giallonardo, et al. (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

992 caregivers of children and adolescents with ADHD | Lockdown | SDSC modified | NF | NF was higher during lockdown for children, unlike adolescents with ADHD (such as other sleep disturbances) | B |

| 8. Bruni, Malorgio, et al. (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

4,314 caregivers of children and adolescents | Lockdown | SDSC modified | NF | NF increased during lockdown only for children, unlike adolescents | B |

| 9. Conte et al., (2022) | Italy |

Quant. Longit. study |

212 adults |

Pre‐total lockdown Total Lockdown Pre‐partial lockdown Partial lockdown |

Ad hoc quest. | DRF, length, vividness, emotional tone, COVID‐19‐related content of dreams |

Dream’ features changed during lockdowns comparing to pre‐periods. DRF decreased with the increased sleep impairment during lockdowns. Negative emotional tone of dreams increased during lockdown periods and was predicted by stress, bad sleep quality, female gender, and younger age. Negative tone of dreams during partial lockdown was not predicted by negative mood, unlike total lockdown. Negative tone of dreams also predicted changes in the others dream features. COVID‐19‐related dreams also increased during lockdowns and were predicted by female gender, negative tone of dreams, dream vividness and high fear. Continuity hypothesis was partially questioned |

A |

| 10. Currie (2021) | Canada |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

933 adults without a PTSD pre‐pandemic diagnosis | 1st year of the pandemic | Primary Care PTSD Screen Modified | Nightmares aggregates with intrusive thoughts about COVID‐19 | Women had more nightmares about COVID‐19. Those who had substance use had a major possibility of having nightmares and intrusive thoughts | B |

| 11. Dondi et al. (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

6,210 caregivers of children and adolescents | Partial lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | NF (associated with sleep terrors) | NF increased during lockdown for children/adolescents more affected by the consequences of the pandemic. No comparison among age groups was analysed | B |

| 12. Drager et al. (2022) | Brazil |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

4,384 HCW | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | NF | An increase in NF was found associated to younger age, female gender, more contacts with COVID‐19 patients, income reduction, weight gain, anxiety, burnout, and insomnia | A |

| 13. Engström et al. (2022) | Sweden |

Qual. Cross‐sectional |

13 critically ill patients with COVID‐19 | Pandemic in general | IPA Interviews | Nightmare narratives | Terrifying nightmares were narrated by patients in the ICU. Relatives and worries for their health were recurrent in dreams | B |

| 14. Ferraro et al. (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

223 parents of children | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | NF | Higher NF predicted emotional distress in children | B |

| 15. Fränkl et al. (2021) | Multi‐country (N = 14) |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

19,355 adults | I year of the pandemic | BNSQ modified | DRF | DRF increased during lockdown and was predicted by female gender, younger age, increasing in NF, sleep talking, sleep maintenance problems, symptoms of REM sleep behaviour disorder, and intrusive thoughts (PTSD symptoms). DRF was negatively associated with depression and anxiety. Continuity hypothesis was supported | A |

| 16. Gallagher and Incelli (2021) | USA |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

193 college students | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | DRF | Women had higher DRF. COVID‐19‐related dreams reports were influenced by priming effect. No significant associations were observed between DRF and the direct impact of the pandemic | B |

| 17. Giardino et al. (2020) | Argentina |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

1,959 HCW | 1st year of the pandemic | Items from Innsbruck RBD inventory | NF and violent dreams frequency | 58.9% of health professionals had nightmares and violent dreams during the pandemic. NF was higher in workers with major psychological distress | B |

| 18. Giovanardi et al., (2022) | Italy |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

598 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | Dream content, COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency, DRF, vividness, and emotional tone of dreams |

DRF and COVID‐19‐related dreams’ frequency were higher in women than men. COVID‐19‐related dreams’ frequency was higher in people who were undergoing psychotherapy and was correlated to a lower psychological distress. Dreams’ vividness was higher in people with higher fear of COVID‐19. Friends, warlike setting, crowds, digital devices, maternity dreams, and fear of unknown other emerged as dreams’ themes. Negative tone of dreams was frequent. Continuity hypothesis was supported |

B |

| 19. Goncalves et al., (2022) | Portugal |

Quant. Repetitive measures design |

5,011 general population (≥16 years) | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | NF | Being women, being younger, having greater fear of COVID‐19, and having a diagnosis of COVID‐19 were among predictors of the most severe profile in NF and insomnia | B |

| 20. Gorgoni et al., (2021) | Italy |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

1,091 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | DRF; emotional intensity; vividness, bizarreness, length, and emotions of dreams. |

All dream features were higher in lockdown period than before. They were associated with higher increase in PTSD (except length), and depression (except bizarreness and length). Younger age, female gender, living alone, in the North, longer sleep duration, higher sleep disturbances and poor sleep quality were predictors of higher scores in DRF, vividness, emotional intensity and length (except sleep quality) of dreams during lockdown. DRF and vividness were also predicted by depression. Higher daytime dysfunction predicted vividness and emotional intensity. Negative emotions were higher in women, people with poor sleep quality, PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Fear was the most frequent emotion in dreams during lockdown, unlike the pre‐pandemic period. No difference was found for people who had been exposed directly and indirectly to the virus. Continuity hypothesis was supported |

B |

| 21. Goweda et al. (2020) | Saudi Arabia |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

438 college students |

1st year of the pandemic | Sleep‐50 questionnaire | NF | NF was one of the least prevalent sleep disturbances (13.7%) | C |

| 22. Guerrero‐Gomez et al. (2021) | Multi‐country (N = 3) |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

2,105 adolescents | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | DRF, NF, COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency, extraordinary dreams frequency |

DRF was higher in girls, older students and participants that reported feelings of sadness and discomfort referred to their daytime life. NF was higher in girls, older students, Italian participants, and people who reported greater fear, difficulty to manage COVID‐19 problems, emotions of sadness, fear, and emptiness and in people who did not miss contact with others and changed the relationship with parents and friends during lockdown. COVID‐19‐related dreams were predicted by female gender, younger age, worries about COVID‐19 and creative time. Continuity hypothesis was supported |

B |

| 23. Guo and Shen (2021) | China |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

328 adults | 1st year of the pandemic |

Dream Threat Questionnaire (DTQ) |

Threatening dream frequency | Anxiety mediated the relationship between higher exposure to media and threatening dream frequency, with the negative moderation effect of coping efficacy | B |

| 24. Halstead et al. (2021) | Not specified |

Quant. Longit. study |

95 adults with autism |

T1: pre‐lockdown T2: during lockdown T3: after lockdown |

Ad hoc quest | NF | NF was higher during lockdown than pre‐lockdown | A |

| 25. Herrero San Martin et al. (2020) | Spain |

Quant. Case–control study |

170 HCW and non‐HCW (controls) | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | NF, vivid dreams’ frequency | NF was higher in HCW than control group. No difference was found for vivid dreams’ frequency | B |

| 26. Holzinger et al. (2021) | Austria |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

77 adults | Lockdown |

Dreamland Questionnaire (DL‐Q) |

NF, DRF | No specific results on NF were provided. No difference in DRF before and during lockdown was reported | C |

| 27. Ingegnoli et al. (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

507 patients with chronic rheumatic diseases | Lockdown | IES‐R | COVID‐19‐related nightmares/ dreams | 29.9% reported COVID‐19‐related dreams | B |

| 28. Iorio et al. (2020) | Italy |

Qual./ Quant. Cross‐sectional |

796 adults | Lockdown |

Dream Questionnaire The most recent dream |

Dreams content, DRF, emotional intensity, emotional tone of dream, COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency, realism/ bizarreness, creative content of dreams | Women had higher DRF, emotional intensity and negative tone of dreams. Women and people who knew a person dead/infected by COVID‐19 reported more emotions and sensory impressions. The most relevant contents in dreams reports were external locations and the presence of negative emotions. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 29. Iqbal et al., (2021) | Saudi Arabia |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

397 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | Nightmares, bad/horrible dreams frequency | No specific result on nightmare was reported. Bad/horrible dreams frequency was higher in people who had been in contact with a person affected by COVID‐19 | B |

| 30. Jiang et al., (2020) | China |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

338 adults | Lockdown | Post‐traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist | NF | A strong connection emerged between NF and intrusive thoughts during lockdown | B |

| 31. Kennedy et al. (2021) | USA |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

419 adults | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc items; MADRE | COVID‐19‐related nightmares contents; NF | Depression and anxiety were associated to nightmare themes. COVID‐19 general stress was more associated to war, totalitarianism (such as poor sleep quality) and helpless | B |

| 32. Kheirallah et al. (2021) | Jordan |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

3,000 medical students | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | NF | 13% of participants reported an increase in NF | B |

| 33. Kilius et al. (2021) | Not specified |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional Control with baseline data |

71 university students Controls: Hall and Von de Castle baseline data |

Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | Changing in dreaming; NF; dreams content | A change in dreaming was found, with an increase of stress and vividness in dreams. Women showed higher NF. Dreams considered ‘bad’ were frequent. Anxiety, confusion, fear, unknown places, were common in dreams content. Compared to baseline control scores, women during the pandemic had higher aggressive references in their dream report. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 34. Korukcu et al., 2022 | Turkey |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

429 pregnant women | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐19‐related bad dreams frequency | High COVID‐19‐related bad dreams frequency was one of the best predictors of depressive symptoms | B |

| 35. Lehmann et al. (2021) | Norway |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

2,997 adolescents | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | NF | Women, older participants, and those with a lower socio‐economic income had higher NF | B |

| 36. Li et al. (2021) | China |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

528, medical staff members and medical students | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency | COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency was one of the best predictors of the psychological distress in medical staff and students | B |

| 37. Lin, Wang, et al., (2021) | China |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

528 medical staff members | Lockdown |

PSQI Component 5 |

NF | Higher NF was associated to higher sleep duration and reduced sleep efficacy | B |

| 38. MacKay and DeCicco (2020) | Canada |

Qual./ Quant. Non‐concurrent case–control study |

19 university students Controls: students accessed not during the pandemic |

1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | Dream content | More imagery of location changes, animal, head, food, and COVID‐19‐related dream imagery were found in COVID‐19 group than controls. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 39. Mandelkorn et al. (2021) | Multi‐country (N = 49) | Cross‐sectional |

Studio 1 2,562 Studio 2 971 adults |

Lockdown | Ad hoc questions | Changing in dream patterns | In both studies more than a third of the participants reported a change in dream patterns | A |

| 40. Margherita et al. (2021) | Italy |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

1,095 adults | Lockdown | MADRE, ad hoc quest. | Dream narratives content and functions, DRF, attitudes toward the dreams | The main themes emerged were: escape from the threat; the work of mourning, unrecalled dreams; COVID‐19: As manifest content. The three functions emerged were: remembering, repeating, and working through; from traumatic content to problem‐solving strategy; from the safe‐guardian of sleep to the safe‐guardian of dream waking continuity. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 41. Mariani, Gennaro, et al. (2021) | Italy |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

49 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | Dream narratives’ functions | Comparing dream narratives to waking thoughts narratives, both showed higher Affective Salience Index (as in index of affective arousal). Dream narratives had a major Referential Activity function (the symbolisation of experience through different coding systems). Instead, thought narratives presented more reflection and affect words than dream narratives | B |

| 42. Mariani, Monaco, et al. (2021) | Italy |

Qual./ Quant. Cross‐sectional |

68 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | Dream narratives’ functions | Reflection/reorganising dreams (were dreamers discussed the discrepancy between dream and reality) were the most frequent, followed by arousal dreams (were actions, movements, parts of body and unknown feeling were common) and symbolising dreams (characterised by the use of metaphors) at least. Younger age and being in a romantic relationship were associated with more negative emotions | B |

| 43. Marogna et al. (2021) | Italy |

Qual. Cross‐sectional |

17 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | Dream narratives and associations | The most common groups of themes were: contents about lockdown, restrictions, social distance, PEP, and isolation anxiety; apocalypse, dystopia and war like contents; difficulties in moving and returning to home | B |

| 44. Monterrosa‐Castro et al. (2020) | Columbia |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

531 healthcare practitioners | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐19‐related NF | Anxiety symptoms were associated to NF about COVID‐19 | B |

| 45. Mota et al. (2020) | Brazil |

Qual./ Quant. Case–control non‐concurrent study |

67 adults Controls: adults accessed prior to the pandemic |

Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐19‐related dreams content and length | During the pandemic the dream reports were longer, presented more words related to anger and sadness, and to the semantic areas of ‘contamination’ and ‘cleanness’, frequent in people with major psychological distress, in particular distress related to social isolation. No difference was found in emotional tone of dream reports | B |

| 46. Musse et al. (2020) | Brazil |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

1,057 adults | 1st year of the pandemic |

Ad hoc quest. |

NF, COVID‐19‐related NF | People reported a three‐fold increase in NF during the pandemic. 32.9% of them had a pandemic content. Prior psychiatric care, suicidal ideation, sleep medication, increased, pandemic alcohol consumption, perceiving high risk of contamination, being a woman, and of younger age were factors associated with NF. Prior psychiatric care, sleep medication, and age were factors associated with a pandemic content. No difference was found between health professionals and the general population | B |

| 47. Parrello et al., (2021) | Italy |

Qual./ Quant. Cross‐sectional |

235 adolescents | Lockdown | MADRE, the most recent dream | Dreams content, DRF, NF, emotional intensity, and tone of dreams | Girls had higher DRF, NF, emotional intensity, negative tone of dreams, and COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency. Common contents were setting (indoor and outdoor), friends and family, often associated to negative emotions, mainly related to violent and dangerous situations. Age had an effect only on the emotional intensity. The effect of COVID‐19‐relevant variable were found, in particular on the emotional intensity and the length of dreams reports. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 48. Partinen et al. (2021) | Multi‐country (N = 24) |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

22,151 adults | 1st year of the pandemic | BNSQ modified | NF | NF increased during the pandemic and was higher in people who had been infected by COVID‐19 and in people with financial problems | A |

| 49. Pérez‐Carbonell et al.,( 2020) | Not specified |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

834 adults | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | NF | NF was higher in people in self‐isolation, people with suspected COVID‐19 infection, and with psychological distress | B |

| 50. Pesonen et al. (2020) | Not specified |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

811 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | NF, nightmares and dreams content | NF increased during the pandemic and was higher in people with higher level of stress. Women were more likely to report dreams content, than man (no difference was found for age). More than a half of thematic clusters extracted from dreams reports were COVID‐19 related | B |

| 51. Petrov et al. (2021) | Multi‐country (N = 79) |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

991 adults | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | NF | NF increased during the pandemic in different sleep profiles | B |

| 52. Ramos Socarras et al. (2021) | Canada |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

498 adolescents and young adults | Lockdown | PSQI adapted | NF | Young adults reported an increase in sleep difficulties associated with sleep onset difficulties, nocturnal and early morning awakenings, and NF than adolescents | B |

| 53. Reséndiz‐Aparicio (2021) | Mexico |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

4,000 parents of children | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | NF | NF was observed in children but not with a high percentage | B |

| 54. Scarpelli, Alfonsi, D'Anselmo, et al. (2021) | Italy | Qual./Quant. Case–control study |

129 pharmacologically treated patients with NT1 Controls: people without NT1 |

Pandemic | MADRE | DRF, NF, Lucid‐dreams frequency, emotional aspects of dreams. | Lucid‐dreams frequency was higher in NT1 patients than controls. No difference was found for DRF and dream emotionality. Female gender, longer sleep duration, higher intra‐sleep wakefulness predicted NF in NT1 patients. DRF, NF and lucid‐dreams frequency were positively correlated with sleepiness. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 55. Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al. (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Longit. study |

611 adults |

T1: lockdown T2: second wave |

PSQI‐A, MADRE | DRF, NF, nightmare distress, emotional intensity, and tone of dreams, lucid‐dream frequency | DRF, NF, lucid‐dreams frequency, nightmare distress and emotional intensity decreased in the second wave while negative tone of dreams increased in the second wave. People with an increase in NF in the second wave showed higher problems in sleeping, PTSD symptoms and post‐traumatic growth in relationship. People with an increase in lucid‐dream frequency showed higher post‐traumatic growth and PTSD‐symptoms. No difference was found for higher dream‐recallers. Job changes and asking help to mental health services was associated with a major intensity of dreams emotions and nightmare distress. Quarantine and having significant others affected by COVID‐19 was associated to a major negative tone of dreams. Continuity hypothesis was partially supported | A |

| 56. Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., (2021) | Italy |

Quant. Cross‐sectional/ case–control non‐concurrent study |

5,988 adults Control group: population‐based Italian sample provided by Settineri |

Lockdown | MADRE | DRF, NF, Nightmare distress, emotional tone, and intensity of dreams | DRF and NF were higher in participants accessed during the pandemic than controls. Younger age, female gender, not having children and higher sleep duration were associated with higher DRF. Younger age, female gender, modification of daytime napping, high intra‐sleep wakefulness, greater sleep duration, higher sleep problem index score, higher anxiety and depressive symptoms were associated with higher NF. People who stopped working, had significant others infected by COVID‐19, and changed sleep habits had higher intensity and negative tone of dreams. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 57. Scarpelli, S., Gorgoni, Alfonsi et al., (2022) | Italy |

Qual./Quant. Longit. study |

90 adults |

1: lockdown 2: immediate post‐lockdown |

Sleep diary; PSQI‐A; Typical Dreams Questionnaire modified | DRF, lucid‐ dreams frequency, dreams content | DRF and lucid‐dreams frequency were higher during lockdown than post‐lockdown. Considering dreams content, during lockdown people dreamed of more crowded places and travelling. Continuity hypothesis was supported | A |

| 58. Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., (2022) | Multi‐country (N = 14) |

Quant. Case–control concurrent study |

1,088 people infected by COVID‐19 Control group: people not infected with COVID‐19 |

1st years of the pandemic | BNSQ modified | DRF, NF | People reported higher DRF and NF during the pandemic than before. No difference was found between controls and COVID‐19 infected participants in DRF before and during the pandemic. NF was higher in the COVID‐19 group exclusively during the pandemic. Younger age, higher DRF, high anxiety and insomnia symptoms, high risk of PTSD, lower sleep duration and a major severity of COVID‐19 symptoms predicted higher NF | A |

| 59. Šćepanović et al. (2022) | Multi‐country (N = 86) |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

2,888 adults | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐19‐related dream narratives | COVID‐19‐related medical words were found both in discussion online narratives and in dreams narratives shared online. In discussion narratives words related to real symptoms of COVID‐19 were frequent, while in dreams narratives not‐COVID‐19‐related symptoms and surreal conditions were more frequent. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 60. Schlarb et al. (2020) | Not specified |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

12 parents of children (aged 5–10 years) with insomnia | Pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | Nightmares | Online cognitive behavioural group therapy for insomnia for school children and their parents during the pandemic was presented, including modules on finding strategies against nightmares | C |

| 61. Schredl and Bulkeley (2020) | USA |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

3,031 adults | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | DRF, emotional tone of dreams, COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency and contents | People more affected by the virus consequences had higher DRF, negative tone of dreams and COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency. DRF was also predicted by younger age, higher level of education and physical health. Emotional tone of dreams was predicted by female gender, and social isolation. COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency was predicted by female gender, higher level of education, physical health. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 62. Solomonova et al. (2021) | Worldwide (N = 6) |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

968 adults | Lockdown |

Typical Dreams Questionnaire |

DRF, bad dreams frequency and NF, dreams content | Changes in DRF during the pandemic was found. No changes in NF emerged, though a decreasing in bad dreams frequency was found. No association between DRF and sleep duration emerged, whereas a weak association was found between NF and bad dreams and a decrease in sleep duration. The main dream themes emerged were inefficacy, threat from other humans, death, and the pandemic imagery. All these elements were associated with more stress. Bad dreams frequency, and four main themes frequency were also associated to more depression and anxiety | B |

| 63. Sommantico et al. (2021) | Italy |

Qual./Quant. Cross‐sectional |

475 adults and adolescents | Lockdown | Most recent dream, Dream questionnaire | DRF, emotional intensity and tone of dreams, dreams content, dream length, sensory impressions frequency | Adults had longer dreams’ reports, higher emotional intensity and negative tone and presence of sensory impressions in their dreams than adolescents. Adolescents had higher DRF. People more affected by COVID‐19 reported more effects in their dreams, especially adolescents. Women had higher DRF, negative tone and intensity of dreams, and sensory impressions and longer dreams than man. Considering the content, adults dreamt more about pleasure actions, forbidden by the restrictions, whereas adolescents dreamt more about relationships. In both groups, dreaming home confinement was associated with higher negative tone of dreams. Continuity hypothesis was supported | B |

| 64. Taylor et al. (2020) | Muti‐country (N = 2) |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

6854 adults | Pandemic |

COVID‐19 Stress Scales |

NF | NF was included as an index of specific stress manifestation during COVID‐19 spread and was associated to a greater exposure to news media | B |

| 65. Wang et al. (2021) | China |

Qual./Quant. Case control non‐concurrent study |

182 adults during the pandemic, Control group: adults assessed before the pandemic |

Lockdown | Malinowski's (2015) question | Dreams content, dreams report length | No difference was found in reports’ length. Dreams collected during the pandemic reported higher presence of non‐aggressive threatening events than dreams collected before the pandemic. No difference was found for types of interactions (negative, positive, neutral), presence of illness or health events. Continuity hypothesis was questioned | B |

| 66. Wang et al. (2020) | China |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

1,599 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐29‐related dreams frequency | COVID‐29‐related dreams frequency partially explained higher psychological distress, along with perceiving changes and emotional control | B |

| 67. Wu et al. (2020) | China |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

505 adults | Lockdown | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency | Higher COVID‐19‐related dreams frequency was associated with more serious mental illness | B |

| 68. Xiong et al. (2021) | China |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

291 surviving frontline HCW | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | COVID‐19‐related NF | COVID‐19‐related NF was not a common symptom of PTS in surviving HCW, although the percentage was not low (34.5%), such us flashbacks, amnesia, over alertness | B |

| 69. Yasmin et al. (2021) | Bangladesh |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

248 bankers | 1st year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | Wakes up from sleep having a bad dreams frequency | High frequency of bad dreams was associated with higher level of depression, stress, and anxiety | C |

| 70. Tu et al., 2020 | China |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

100 frontline nurses | 2nd year of the pandemic | PSQI | NF | NF was reported in about a half of the sample | B |

| 71. Zupancic et al. (2021) | Slovenia |

Quant. Cross‐sectional |

1,189 physicians | 2nd year of the pandemic | Ad hoc quest. | NF | NF was higher in frontline physicians | B |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder; BNSQ modified, Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire Modified (Partinen & Gislason, 1995; Partinen et al., 2021); COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; DRF, dream‐recall frequency; HCW, healthcare workers; IPA, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith, 2007); Longit., longitudinal; MADRE, Mannheim Dream Questionnaire (Schredl et al., 2014); NF, nightmare frequency; NT1, narcolepsy type‐1; PEP, personal protective equipment; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Buysse et al., 1989); PSQI‐A, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index‐Addendum (Germain et al., 2005); quest., questions; SDSC, Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (Bruni et al., 1996); PTS(D), post‐traumatic stress (disorder); Qual., qualitative; Quant., quantitative.

Quality assessment

For the quality assessment the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Qualitative Studies Checklist and the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross‐Sectional Studies were used (https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools). For quali‐quantitative studies an integration of both the instruments was used.

Each item was rated according to four possible responses ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’. Two researchers independently scored on each included study, and, in the end, an overall quality judgment was elaborated. The scoring was organised on three levels: Level A rating if 100% or more of applicable categories were rated as ‘yes’; Level B, if between 99% and 50% of items were rated as ‘yes’; and Level C, if <50% of items were rated as ‘yes’.

RESULTS

Among all the papers included in the review, no studies were published in 2019, 18 studies were published in 2020, 44 studies were published in 2021, and 9 were published during the first months of 2022. The majority of the studies were conducted in Italy (23), followed by China (nine), Canada, USA, and Brazil (three), and another 30 articles were conducted in other countries. Moreover, 10 articles were classified as multi‐country studies, as they included data collected in two or more countries.

Regarding methods, 49 studies were quantitative, two studies were exclusively qualitative, and 20 studies used a mixed quali‐quantitative method. In all, 59 studies had a cross‐sectional design, five were longitudinal studies, 10 studies provided controls (three were non‐concurrent case studies and used data collected in a different group prior to the pandemic as controls, three compared data with normative/baseline scores identified by other studies, four compared different groups). No systematic reviews were found.

Furthermore, 12 studies included <100 participants, 36 studies included between 100 and 1,000 participants, 22 studies included >1,000 participants.

Considering age range, 47 studies collected data on adults, nine on adolescents, nine reported data on children, and six studies were specifically on healthcare workers (HCW).

In 46 articles authors referred their data to lockdown periods, 23 collected data during the first year of COVID‐19 spread, whereas two were during the second year (2021).

In 31 studies validated instruments were used (Mannheim Dream Questionnaire [MADRE], Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI‐A], Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire [BNSQ]‐modified), whereas in 40 studies ad hoc questions were formulated to assess dreaming dimensions.

Considering dreaming phenomena, 48 papers reported data on nightmare features (among them 37 were on NF, four on COVID‐19‐related NF, two on nightmare distress, and five discussed nightmares during the COVID‐19 pandemic in general); 11 reported information about emotions in oneiric activity (five studies focused on emotional intensity, four on the emotional tone of dreams, and two on emotions in dreams in general); 20 studies included data on DRF; 18 studies accessed specifically COVID‐19‐related dreams in content and/or frequency; whereas 14 reported data on content of dreams collected during the COVID‐19 pandemic in general.

Considering the quality level, nine studies were Level A, four were Level C, whereas the majority were Level B (58).

Main results of the studies

Data on the general population

Dream‐recall frequency of healthy subjects

During lockdowns, DRF in the general population changed, although the direction of this change remains unclear.

Although four articles showed an increase in DRF in individuals during lockdown (Alfonsi et al., 2021; Fränkl et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, D’Anselmo, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021), three studies were not consistent with these data (Conte et al., 2022; Holzinger et al., 2021; Solomonova et al., 2021).

Although post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms accessed through self‐report measures in the general population were associated with an increase in DRF in one study (Gorgoni et al., 2021), there were contradictory findings in the relationship between DRF, psychological distress and COVID‐19‐related variables emerging in eight studies (Conte et al., 2022; Fränkl et al., 2021; Gallagher & Incelli, 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, D'Anselmo, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Schredl & Bulkeley, 2020; Solomonova et al., 2021).

Moreover, three longitudinal studies showed a decrease in DRF immediately after lockdowns and during the second wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic (Alfonsi et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni et al., 2021), although the Conte et al. (2022) data did not confirm the direction of this change.

Nightmare frequency and emotionality in dreams

In general, six papers suggested an increase in NF during the first year of the virus spread (Dondi et al., 2021; Halstead et al., 2021; Musse et al., 2020; Partinen et al., 2021; Pesonen et al., 2020; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021).

The NF was assessed by two studies as part of the PTSD symptomatology (Currie, 2021; Jiang et al., 2020) and as an independent index of psychological distress in adults, adolescences, and children in three studies (Ferraro et al., 2021; Musse et al., 2020; Reséndiz‐Aparicio, 2021). In a further 12 studies it was considered as an index of sleep impairment and poor sleep quality (Dondi et al., 2021; Goncalves et al., 2022; Goweda et al., 2020; Lin, Lin, et al., 2021; Parrello et al., 2021; Partinen et al., 2021; Pérez‐Carbonell et al., 2020; Petrov et al., 2021; Ramos Socarras et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Schlarb et al., 2020), whereas in seven studies it was considered as a dreaming life phenomenon (Guerrero‐Gomez et al., 2021; Holzinger et al., 2021; Kennedy et al., 2021; Kilius et al., 2021; Pesonen et al., 2020; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021); five studies overlap nightmares with bad or threatening dreams, focusing attention on the content component (Guo & Shen, 2021; Iqbal et al., 2021; Korukcu et al., 2022; Solomonova et al., 2021; Yasmin et al., 2021); one study considered nightmares as a symptom of COVID‐19‐related stress (Taylor et al., 2020). At least, four studies referred specifically to ‘COVID‐19‐related nightmare frequency’ (Kennedy et al., 2021; Korukcu et al., 2022; Musse et al., 2020).

In studies that assessed NF as a symptom of PTSD it emerged that nightmares were predicted by alcohol consumption in the general population (Currie, 2021).

Assessed as an independent index of psychological distress it resulted in being associated with prior psychiatric care, suicidal ideation, pandemic alcohol consumption, and perceiving a high risk of contamination in adults (Musse et al., 2020).

Considering high NF as a form of poor sleep quality, it was predicted by being more affected by the consequences of the pandemic (Dondi et al., 2021), having higher fear for COVID‐19, having a diagnosis of COVID‐19 (Goncalves et al., 2022; Partinen et al., 2021; Pérez‐Carbonell et al., 2020), and a major severity of COVID‐19 symptoms (Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022).

Moreover, NF resulted in a dream phenomenon associated with higher level of stress (Pesonen et al., 2020), anxiety, depression (Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021) and PTSD symptoms during the spread of the second wave of the virus (Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021).

Moreover, NF was associated with major emotional distress in five studies (Ferraro et al., 2021; Guerrero‐Gomez et al., 2021; Pesonen et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Solomonova et al., 2021).

Likewise, a prevalence of negative emotions in dreams and negative emotional tone of dreams was found during lockdowns in seven studies (Barrett, 2020; Borghi et al., 2021; Conte et al., 2022; Gorgoni et al., 2021; Giovanardi et al., 2022; Iorio et al., 2020; Parrello et al., 2021).

Considering the content, four studies reported that fear and anguish were the prevalent emotions found in dreams during the acute phase of the pandemic (Giovanardi et al., 2022; Gorgoni et al., 2021; Guerrero‐Gomez et al., 2021; Kilius et al., 2021).

Psychological distress, PTSD symptoms (Conte et al., 2022; Gorgoni et al., 2021), and showing COVID‐19‐related contents on the relationship domain (Borghi et al., 2021; Sommantico et al., 2021) were among the most frequent predictors of negative emotionality in dreams in the general population.

Moreover, a higher emotional intensity of dreams clearly emerged during lockdown as reported by six studies (Gorgoni et al., 2021; Mariani, Gennaro, et al., 2021; Parrello et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Sommantico et al., 2021).

Changing in sleep patterns (Gorgoni et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021), PTSD symptoms registered in the general population (Gorgoni et al., 2021), isolation (Gorgoni et al., 2021; Parrello et al., 2021), knowing at least one person infected by COVID‐19 (Parrello et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021), and job changes (Scarpelli, Alfonsi, D'Anselmo, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021) were considered the best predictors of a higher emotional intensity in dreams during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Longitudinal studies suggested a decrease in negative tone and emotional intensity of dreams after lockdowns (Conte et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021).

A specific result emerged from the longitudinal inquiries, showing that, during total lockdown, the negative tone of dreams was predicted by negative mood of waking life, whereas during partial lockdown this result was not found (Conte et al., 2022).

Dream scenarios: pandemic dreams

Dream imagery changed during the pandemic, including a lot of COVID‐19‐related explicit (i.e., masks, virus, isolation) and implicit contents (catastrophic and apocalyptic scenarios) (Kilius et al., 2021; Marogna et al., 2021; MacKay & DeCicco, 2020; Mota et al., 2020; Pesonen et al., 2020; Solomonova et al., 2021). High COVID‐19‐related imagery in dreams was associated with an increase in psychological distress in the population more affected by the virus as it emerged in six studies (Korukcu et al., 2022; Monterrosa‐Castro et al., 2020; Musse et al., 2020; Schredl & Bulkeley, 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020). Moreover, COVID‐19‐related dream frequency was considered a possible risk of PTSD in the general population during the pandemic in one study (Wang et al., 2020).

Considering the themes and content presented in dreams, studies described different scenarios. Some of the most common themes were: specific COVID‐19‐related imagery (i.e., masks, virus, isolation) (Kilius et al., 2021; Marogna et al., 2021; MacKay & DeCicco, 2020; Mota et al., 2020; Pesonen et al., 2020; Solomonova et al., 2021), death (Barrett, 2020; Margherita et al., 2021; Solomonova et al., 2021), health and illness (Barrett, 2020; Šćepanović et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021), external‐internal and changing settings (Borghi et al., 2021; Iorio et al., 2020; MacKay & DeCicco, 2020; Parrello et al., 2021), violence and war (Kennedy et al., 2021; Marogna et al., 2021; Parrello et al., 2021; Solomonova et al., 2021), relationships especially in adolescence (Borghi et al., 2021; Iorio et al., 2020; Margherita et al., 2021; Parrello et al., 2021; Sommantico et al., 2021), difficulties in actions (Borghi et al., 2021; Marogna et al., 2021), pleasure actions, and non‐aggressive threats imagery (Borghi et al., 2021; Sommantico et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021).

These peculiar characteristics of dreams induced researchers to use the specific term of ‘pandemic dreams’ to refer to dream scenarios that included COVID‐19‐related elements.

Sleep problems, dysfunction, and changes in sleep patterns

Changes in dreaming were found in six studies that accessed changes in sleep patterns, sleep problems and dysfunction during lockdowns (Bruni, Malorgio, et al., 2021; Halstead et al., 2021; Holzinger et al., 2021; Petrov et al., 2021; Ramos Socarras et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021).

These studies considered the presence of NF in individuals during the COVID‐19 pandemic as an index of sleep dysfunction and poor sleep quality (Bruni, Malorgio, et al., 2021; Halstead et al., 2021; Holzinger et al., 2021; Petrov et al., 2021; Ramos Socarras et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021).

During lockdowns, changes in sleep habits, longer sleep duration, poor sleep quality and sleep impairment predicted an increase in other dream phenomena, e.g., DRF, negative tone of dreams, emotional intensity, and dream content (Conte et al., 2022; Gorgoni et al., 2021; Kennedy et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021). In turn, DRF predicted an increase in NF, sleep talking, sleep maintenance problems, and symptoms of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder (Fränkl et al., 2021).

Dreaming in clinical populations during the COVID‐19 pandemic

The six studies that reported data on dreaming in specific clinical populations during the COVID‐19 pandemic, investigated especially NF. In particular, in immigrants with diagnosis of PTSD, NF remained stable during and after lockdowns (Aragona et al., 2022). Prior psychiatric care and suicidal ideation, and an increased pandemic alcohol consumption during lockdowns emerged as predictors of NF (Musse et al., 2022).

Moreover, changes in NF were not found in children with attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) before and during lockdown, unlike children without a diagnosis, which reported an increase in NF during lockdown (Bruni, Breda, et al., 2021; Bruni, Giallonardo, et al., 2021). Otherwise, the longitudinal study conducted by Halstead et al. (2021) reported an increase in NF during lockdown than pre‐lockdown in adults with autism.

A study compared dreaming phenomena frequency of pharmacologically treated patients with narcolepsy type‐1 (NT1) with a control group, showing a difference in the lucid‐dream frequency, higher in patients with NT1 than controls, whereas no differences were found for DRF and dream emotionality. Moreover, female gender, longer sleep duration, and higher intra‐sleep wakefulness predicted NF in patients with NT1.

Moreover, Ingegnoli et al. (2021) reported that the 29.9% of patients with chronic rheumatic diseases had had nightmares about the COVID‐19 pandemic.

A qualitative study (Engström et al., 2022) showed that the narration of nightmares in critically ill patients with COVID‐19 reflected worries for the possible contagion of relatives and HCW.

Moreover, no difference was found between controls and COVID‐19‐infected participants in DRF before and during the pandemic, whereas NF was higher in the COVID‐19 group exclusively during the pandemic (Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022).

Subjects most affected by changes in dreaming

Changes in dreaming were greater in women than man. During the pandemic, women showed a major increase in COVID‐19‐related dream frequency (four studies) (Barrett, 2020; Guerrero‐Gomez et al., 2021; Parrello et al., 2021; Schredl & Bulkeley, 2020), NF (nine studies) (Currie, 2021; Drager et al., 2022; Goncalves et al., 2022; Guerrero‐Gomez et al., 2021; Kilius et al., 2021; Lehman et al., 2021; Parrello et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, D'Anselmo, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021), negative emotions and emotional intensity of dreams (seven studies) (Barrett, 2020; Conte et al., 2022; Gorgoni et al., 2021; Iorio et al., 2020; Parrello et al., 2021; Schredl & Bulkeley, 2020; Sommantico et al., 2021), and DRF (eight studies) (Fränkl et al., 2021; Gallagher & Incelli, 2021; Giovanardi et al., 2022; Guerrero‐Gomez et al., 2021; Iorio et al., 2020; Parrello et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Sommantico et al., 2021).

Children also surfaced as a group with an altered NF in three studies (Bruni, Malorgio, et al., 2021; Ferraro et al., 2021; Reséndiz‐Aparicio, 2021). Younger adults, unlike adolescence, were also associated with an increase in NF and negative emotions (eight studies) (Conte et al., 2022; Goncalves et al., 2022; Mariani, Monaco, et al., 2021; Musse et al., 2020; Ramos Socarras et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022; Sommantico et al., 2021), DRF (four studies) (Fränkl et al., 2021; Gorgoni et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Schredl & Bulkeley, 2020), and COVID‐19‐related dream frequency (Guerrero‐Gomez et al., 2021).

Among studies on HCW and healthcare students, six suggested these populations experienced nightmares during the pandemic (Bhat et al., 2021; Drager et al., 2021; Kheirallah et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2021; Tu et al., 2020; Zupancic et al., 2021). More contacts with COVID‐19 patients, income reduction, weight gain, anxiety, burnout, insomnia, higher sleep duration, reduced sleep efficacy, and higher psychological distress emerged as predictors of NF in this population (Giardino et al., 2021; Lin, Lin, et al., 2021; Monterrosa‐Castro et al., 2020). Herrero San Martin et al. (2020) showed the level of NF was greater for HCW than the general population. Moreover, COVID‐19‐related dream frequency emerged as one of the best predictors of psychological distress in medical staff and students (Li et al., 2021).

Mainly in HCW and groups more affected by virus consequences, changes in dreaming were associated with sleep disruptions (four studies) (Drager et al., 2022; Lin, Lin, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022). These groups also showed a higher ‘pandemic dream’ frequency (four studies) (Schredl & Bulkeley, 2020; Xiong et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021) and NF (eight studies) (Herrero San Martin et al., 2020; Kheirallah et al., 2021; Monterrosa‐Castro et al., 2020, Scarpelli, Alfonsi, D'Anselmo, et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Tu et al., 2020; Zupancic et al., 2021; Yasmin et al., 2021).

DISCUSSION

The great number of studies included in the present review (71), reporting results and comments about dreaming during the COVID‐19 pandemic, shows an increasing interest in dreams and dreaming, sustaining the necessity of a LSR design to cover this topic in the forthcoming years. To date, studying dream‐related phenomena appeared an effective way to access symptoms of psychological distress as well as, in a broader sense, permitting the access to the in‐depth internal and emotional world of people reacting to the ‘collective trauma’ of the COVID‐19 pandemic, giving insight into the psychological functioning in this period of crisis.

How: methodological issues

This paragraph contains reflections about methods and critical issues that emerged from ‘how’ oneiric activity during COVID‐19 pandemic was assessed.

We recorded an average quality in the majority of the studies included in the review, although the present study confirms some considerations provided by a previous review (Gorgoni et al., 2022) regarding the heterogeneity of methods used by researchers to assess dreaming phenomena and some of the possible biases. Among them, quali‐quantitative designs appear as an emerging and wide approach to investigate dreams and dreaming, permitting the integration of results about the frequency of dream phenomena with an analysis of the content of dreams.

Considering the design of the studies, the low number of studies (10) that provide controls could represent a weakness in methodology, although it is partially a consequence of the unpredictability and peculiarities of the pandemic experience.

Moreover, the use of non‐standardised and validated instruments in the majority of the studies (40) used to assess dreaming phenomena represents a limit that increases the heterogeneity of the studies and reduces the possibility to compare the results systematically. Future research should address this point by increasing the use of validated instruments, to enhance the reproducibility of the research.

Methodologically, data about dreaming before the pandemic were mainly accessed through retrospective questions, with the exception of the few studies that provided control comparisons and longitudinal analysis. Hence, we need to consider that data retrieved by retrospective items or questions, frequent in COVID‐19‐related studies, might be subject to several biases, which can influence the recall accuracy (Aspy et al., 2015; Gorgoni et al., 2022; Hipp et al., 2020). The studies during the pandemic included mainly retrospective protocols for the collection of dream narratives and reports, while only two studies (Alfonsi et al., 2021; Scarpelli et al., 2021d) used prospective protocols (such as diaries), which are less influenced by recall biases (Robert & Zadra, 2008; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022). Moreover, restrictions imposed by the pandemic might have limited the organisation of experimental laboratory studies often used before the pandemic in dream‐ and sleep‐related research. Indeed, no studies on dreaming through provoked awakenings and the assessment of neurophysiological indices were found in the literature during the COVID‐19 pandemic. New information derived from these types of studies might confirm or not the findings summarised in the present review.

Furthermore, for qualitative data collection some considerations are needed. It is well‐known that dream reports and dream narratives are influenced by the context (Margherita et al., 2015; Margherita et al., 2017; Windt, 2013), and that the online survey might enhance some possible biases, e.g., self‐selection bias.

Otherwise, the focus on the general population in the majority of the studies and the use of the online survey to collect data, permitted access to a substantial amount of data, as is shown by the number of participants in the research on dreaming who were accrued in the study by Fränkl et al. (2021), which included 19,355 participants from 14 countries.

In addition to the methodological considerations (‘How’), to comment on the specific results, we have organised the discussion by answering the ‘Five Ws’ or ‘Wh‐questions’ with reference to dreaming during the pandemic: in which countries and contexts did dreaming patterns appear to have changed (where)? How did dreaming change during the different phases of the pandemic (when)? What characteristics of dreaming changed during the virus spread (what)? For whom did dreaming change during the pandemic (who)? Why did dreaming change during the pandemic (why)?

Where and When

Research took place especially in contexts and periods characterised by the most acute impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic, as shown by the prevalence of studies conducted in Italy, China and during lockdowns in different countries, in line with the Gorgoni et al. (2022) review. High‐quality studies, which compared data from several different countries, showed no relevant difference between nations or continents (Fränkl et al., 2021; Mandelkorn et al., 2021; Partinen et al., 2021; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022). Moreover, pandemic‐related situational aspects, e.g., total or partial lockdown, seemed to have a major impact on the changes in dream phenomena. Longitudinal studies of Level A included in the review showed a decrease in NF, DRF (except Conte et al., 2022), negative emotions and emotional intensity of dreams after lockdowns. This result was consistent with longitudinal studies that showed an increase in psychological and emotional distress in daytime life in the general population during lockdown, with a decrease after lockdown (Robinson et al., 2022; Shanahan et al., 2020).

The absence of ‘baseline’ data collected before the pandemic outbreak instead represents a limitation of these longitudinal studies, which can only provide information about what has happened during the waves of the pandemic rather than a comparison with previous data, with the exception of the Halstead et al. (2021) results, which showed an increase in NF in people with autism during lockdown through a comparison with pre‐lockdown data collected on the same participants. Otherwise, a lot of Level B studies provide information about the ‘change’ of dreaming, through the use of retrospective questions about dreaming before lockdown.

What

Our analysis showed a great heterogeneity of the results, which will be discussed through the identification of some common trajectories. Considering what changed during the pandemic among dream phenomena and in which direction, with particular mention reserved to: (1) an emerging interest concerning dreams’ contents; (2) new insights about old questions on dream components regarding, in particular, dream recall (a), and emotionality and nightmares (b).

Which contents. A new interest emerged during the current pandemic in dream research. COVID‐19‐related contents (virus‐related imageries, failures to socially distance, coronavirus contagion, personal protective equipment, and catastrophic scenario) directly showed the influence of waking life on dreaming. Dreams became a ‘mental space’ for fears and needs during the virus spread, organised to manifest the scenario of the so‐called ‘pandemic dreams’ (Pesonen et al., 2020), represented in a wide variety of themes observed in several studies. In content terms, pandemic dreams are similar and different from post‐traumatic dreams. In fact, while post‐traumatic dreams (following catastrophic events) replicate recurring collective images, a difficulty to personify the virus and the related anguish in a shared representation emerged in pandemic dreams (Barrett, 2020).

Which components. (a) A wide variability of data about changes in dream recall during the COVID‐19 pandemic was found by comparing the results of the studies included in the present review. Consequentially, among dream phenomena, DRF remained a hard to interpret area (Schredl, 2010). In previous studies, personality traits, neurobiological, situational and relational variables were used as predictors of DRF but did not result in being sufficient to explain its variations (Blagrove & Pace‐Schott, 2010; Scarpelli et al., 2019; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022; Schredl & Göritz, 2017).

Previous studies had shown how dream recall could be partially influenced by sleep duration fluctuations or habits and awakening from REM sleep (Schredl & Reinhard, 2008). Other studies, instead, considered dream recall as quite a stable characteristic of individuals, which could be altered in the case of greater sleep impairment (De Gennaro et al., 2012; Scarpelli et al., 2015), as was observed during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

The ‘arousal‐retrieval model’ (Koulack & Goodenough, 1976), could help to interpret dream‐recall results during the COVID‐19 pandemic considering data on sleep dysfunction. Indeed, previous research has shown the association between greater dream recall and higher sleep fragmentation (van Wyk et al., 2019) and the effect of cortical activation (i.e., increased rapid electroencephalography [EEG] activity or reduced slow EEG activity) on dream recall (Chellappa et al., 2011; Siclari et al., 2017; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Gorgoni et al., 2022). In particular, dream recall during the COVID‐19 pandemic resulted in sleep impairments and symptoms of REM sleep behaviour disorder, as suggested by Level A studies (Conte et al., 2022; Fränkl et al., 2021).

The summary data of this review highlights an old problem in dreaming research ‘we do not know and might never know whether unremembered dreams serve any function’ (Schredl, 2010, p 150).

In this sense, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, both dreaming with its narrative reorganisation, as well as the absence of dream recall and so its maintenance on a mental level, could be opportune protective strategies aimed at preserving the continuity between dreaming and waking life (Margherita et al., 2021).

(b) Regarding emotionality, the findings suggested how COVID‐19 strongly affected oneiric activity. It is well observed in the increase of NF during the first year of the virus spread and its association with emotional and COVID‐19‐related variables.

Before the pandemic, NF, was instead considered a signal of emotional distress (Levin & Nielsen, 2007; Schredl et al., 2009; Schredl & Reinhard, 2011).

Gorgoni et al. (2022) had highlighted the difficulties in comparing studies about nightmares during the COVID‐19 pandemic owing to the lack of a clear and unique definition. Nightmares could be read along a continuum from a normal part of dreaming up to psychopathology. Frequent nightmares are considered an index of PTSD, but also as a parasomnia, index of sleep impairment or general psychological distress. Some reflections can come by considering the function that nightmares have in relation to the trauma.

The literature on post‐traumatic nightmares highlighted that they could or not be associated to PTSD and could be more severe and distressing than typical nightmares, (Nielsen & Levin, 2007). The neurophysiological model suggested that nightmares are associated with an interruption in the brain networks (limbic, paralimbic, and prefrontal regions) responsible for the elaboration of emotional experiences. Difficulties in the activation of this area is typical in patients with PTSD or people with sleep disorders (Nielsen & Levin, 2007).

Previous literature on post‐traumatic nightmares (Hartmann & Basile, 2003; Hartmann & Brezler, 2008) (i.e., studies on the survivors of the September 11, 2001 (9/11) terrorist attacks) focused on the intensity of emotions associated with the ‘central image’ of the dream. While the literature on traumatised people after a war or other traumatic events also showed how dreams can ‘replay’ trauma without variations or can contribute to the elaboration of the traumatic memory (Margherita et al., 2020; Varvin et al., 2012).

Although in the literature there is not a unique definition of nightmare (Gorgoni et al., 2022), during the COVID‐19 pandemic nightmares and post‐traumatic nightmares overlapped, considering the pandemic trauma as a collective and transversal dimension.

Our data confirm the previous literature that suggest how nightmares, in a broad sense, can be considered an expression of emotionality in a more or less adaptive way (Gieselmann et al., 2019; Hartmann, 1984; Nielsen & Levin, 2007; Varvin et al., 2012).

Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of the results might also be influenced by the different instruments used to assess NF.

In summary, considering the components of dreaming, our results showed: (i) the necessity to assess dream recall considering the association with other variables such as sleep impairments, (ii) the NF as both an index of emotional distress or an affective regulator.

Who?

Dream phenomena during COVID‐19 were studied in association with different aspects, including pandemic‐related variables (knowing someone with COVID‐19, being affected by the virus during the data collection, having lost someone due to COVID‐19 etc.) (Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022), sociodemographic data (gender, age, type of work), indices of psychological distress (anxiety, depression, stress symptoms) and other individual variables.

Studies on clinical groups are few and their results are difficult to generalise. Even though interesting results are provided by these studies, e.g., the lack of variance in NF before and during the pandemic in immigrants with a diagnosis of PTSD (Aragona et al., 2022), more studies are needed to systematise these results.

When we consider the assessment of psychological distress in the general population and its association with dreaming changes, conclusions can be summarised for PTSD, unlike depression and anxiety for which there are no clear and concurred results.

The association of PTSD symptoms with dreaming variables in the general population have been assessed through self‐report measures during the COVID‐19 pandemic, showing a positive correlation between higher PTSD scores and NF, COVID‐19‐related dream frequency, DRF, and negative and intense emotions in dreams.

Considering sociodemographic variables, a more intense oneiric activity in females and a higher NF in children and HCW was mainly observed in the general population.

The ‘gender salience’ in dreaming is not new to the literature. Previous studies showed how dream recall and NF was higher in women than men due to the effect of personality and clinical variables (Schredl, 2010; Schredl & Reinhard, 2011). Only for negative emotionality in dreams, in contrast with the studies during the COVID‐19 pandemic, previous studies did not show a clear prevalence in women over men.

According to the age range, an increase in NF was found in children, a greater emotionality was found in young adults, whereas data on adolescents showed more complex results. Longitudinal studies about dreaming in children and adolescents during the phases of the COVID‐19 pandemic are needed to better understand the differences in dreaming in these different groups. Indeed, the literature suggests that nightmares could be most problematic for children's mental health if they persist (Schredl et al., 2009).

The HCW also emerged as a group mainly influenced by changes in dreaming, particularly with an increase in NF and COVID‐19 contents of dreams (Drager et al., 2022).

Hence, some groups were more affected by the pandemic in terms of psychological distress – women, children, young adults and HCW (Glowacz & Schmits, 2020; de Miranda et al., 2020; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020) also emerged as ‘particular’ groups regarding altered dreaming patterns.

Further research is needed on dreaming during the COVID‐19 pandemic in vulnerable and specific non‐clinical groups (i.e., ethnic minorities).

Why?

This question collects different perspectives of the papers. The continuity hypothesis, and its declinations (Barrett, 2017; Domhoff, 2017; Schredl, 2017), was the most frequent theory used by studies to explain the results on dreaming (Gorgoni et al., 2022), although some contributions (Conte et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Alfonsi, Mangiaruga, et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021) expressed some doubts about the exclusive use of this theory to explain changes in the dreaming patterns observed. Before the pandemic, studies about dreaming in people with psychopathologies had already observed both phenomena of continuity and discontinuity in dreaming of people with different diagnoses (Skancke et al., 2014). Data about lockdown focused on a great continuity between contents and emotions in daytime life and night‐time life, but longitudinal studies showed a decrease of this mutual influence. Perhaps a hypothesis of different gradients of ‘continuity’ could be suggested, considering how crises, such as lockdowns, might enhance the continuity between waking and dreaming life.

Several studies included in the review commented on changes in dreaming during lockdown as possible consequences of ‘collective trauma’ in the results.

Some studies have suggested an integrative function of dreaming (Giovanardi et al., 2022; Solomonova et al., 2021), other studies, focused on dream narratives, showed a meaning‐making function, through which the symbolic dreams assume different levels of signification (Mariani, Gennaro, et al., 2021; Mariani, Monaco, et al., 2021; Marogna et al., 2021; Šćepanović et al., 2022).

In a transversal way we could say that from different theoretical frameworks, dreaming appears as a mental activity that regulates emotional processes, as is well demonstrated through the rich interdisciplinary dialogue between models that range from psychoanalysis to cognitivism and neuroscience (Ferro, 2002; Fonagy et al., 2012; Fosshage, 1983; Hartmann, 1984; Solms, 1995).

To increase the investigation about the different functions of dreaming further research in clinical settings is needed (Scarpelli, Alfonsi, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Gorgoni, et al., 2022; Scarpelli, Nadorff, et al., 2022). Moreover, to determine the valence of dreaming and the difficulty of dreaming and sleeping, our findings also suggest the importance of linking the great amount of data on environmental variables with the analysis of personal and trait‐like variables.

CONCLUSION

The present paper represents the first step of a LSR on dreaming during the COVID‐19 pandemic. For years, prior to the pandemic, dreaming phenomena have been investigated in specific ‘homogenous’ groups, such as people with different ages, ethnicities, life conditions, and diagnoses. Instead, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, studies on dreaming have emerged as a useful and broad‐based ‘observatory’ to monitor the psychological health of the general population.

The present review shows a more intense oneiric activity, associated with greater psychological distress, especially during lockdowns than during other phases of the pandemic.