Abstract

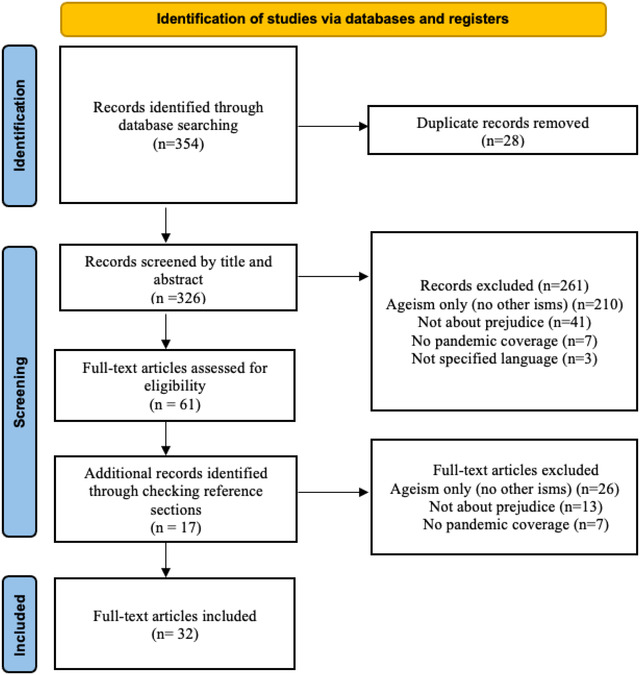

The COVID‐19 pandemic is a significant global issue that has exacerbated pre‐existing structural and social inequalities. There are concerns that ageism toward older adults has intensified in conjunction with elevated forms of other “isms” such as ableism, classism, heterosexism, racism, and sexism. This study offers a systematic review (PRISMA) of ageism toward older adults interacting with other isms during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Articles were searched in 10 databases resulting in 354 ageism studies published between 2019 and August 2022 in English, French, Portuguese, or Spanish. Only 32 articles met eligibility criteria (ageism together with other ism(s); focus on the COVID‐19 pandemic); which were mostly review papers (n = 25) with few empirical papers (n = 7), reflecting almost all qualitative designs (n = 6). Articles discussed ageism with racism (n = 15), classism (n = 11), ableism (n = 9), sexism (n = 7), and heterosexism (n = 2). Authors represented numerous disciplines (gerontology, medicine, nursing, psychology, social work, and sociology) and countries (n = 14) from several continents. Results from this study underscore that ageism intersects with other isms in profoundly negative ways and that the intersections of ageism and other isms are understudied, requiring more research and intervention efforts.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic is a significant global issue that has tested economic, education, employment, healthcare systems, social relationships, and transportation, and throughout, has exacerbated pre‐existing structural and social inequalities such as ageism, ableism, classism, heterosexism, racism, and sexism (Chang et al., 2020; Levy et al., 2022; Misra et al., 2020; P. Wang, 2020; World Health Organization [WHO], 2021a). Isms contain three components: stereotyping (cognitive component), prejudice (affective component), and discrimination (behavioral component). Ageism toward older adults refers to individuals ages 60 and older, and older adults were in the spotlight as early data on the COVID‐19 pandemic indicated that older adults were at disproportionate risk for complications and death (Levy et al., 2022; WHO, 2021a). Older adults faced stereotypes and hate speech as all being sickly and a burden on society, faced prejudgments of being helpless and in need of assistance, and faced discrimination in receiving healthcare such as being turned away for treatment and facing age‐based rationing of ventilators (Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al., 2020; Lichtenstein, 2021; Lloyd‐Sherlock et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2021; Sipocz et al., 2021; Skipper & Rose, 2021; Swift & Chasteen, 2021; Vervaecke & Meisner, 2021; Xiang et al., 2021). At the same time, older adults in some countries and communities received first priority for vaccinations and were provided with dedicated shopping hours and delivery services to reduce their chances of infection from COVID‐19 (Lloyd‐Sherlock et al., 2022; Monahan et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2022; Vervaecke & Meisner, 2021). While some care and positivity was extended to older adults, abundant evidence point to an increase in ageism toward older adults since the onset of the pandemic (Ayalon et al., 2020; Barrett et al., 2021; Bergman et al., 2020; Cohn‐Schwartz et al., 2022; Derrer‐Merk et al., 2022; Drury et al., 2022; Fraser et al., 2020; Kanik et al., 2022; Levy et al., 2022; McDarby et al., 2022; Previtali et al., 2020; Reynolds, 2020; Spaccatini et al., 2022; Sutter et al., 2022; WHO, 2021a). As noted, COVID‐19 pandemic has also exacerbated other isms such as ableism, classism, heterosexism, racism, and sexism (Misra et al., 2020; P. Wang, 2020). As examples, Asian Americans have faced hate speech, anger, and hate crimes (e.g., Misra et al., 2020), and women have faced increases in domestic violence (P. Wang, 2020).

Furthermore, there is evidence that during the COVID‐19 pandemic, individuals are experiencing negative consequences due to the intersections of ageism with other isms such as the compounding effects of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination based on more than one of their identities such as an older adult living with a disability, older transgender individuals, and older Black women (e.g., Banerjee & Rao, 2021). For example, Black and Latinx older adults living in long term care facilities were disproportionately affected by COVID‐19, highlighting how ageism and racism operate in tandem (Chidambaram et al., 2020).

According to intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1991; Overstreet et al., 2020; Rosenthal, 2016), individuals with multiple stigmatized identities (e.g., older women) may experience unique forms of stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination that they would not experience based on only one of their identities alone. The origins of intersectionality theory are in law and the study of Black women's liberation (Crenshaw, 1991); however, the intersectionality framework has subsequently expanded to the study of any interlocking systems of power (e.g., ableism, ageism, sexism) in psychology, law, and sociology (Overstreet et al., 2020; Rosenthal, 2016). There is a small but growing body of research on the intersections of ageism, ableism, heterosexism, racism, and sexism (Apriceno & Levy, 2019; Chrisler et al., 2016; Jönson & Taghizadeh Larsson, 2021; Kim & Fredriksen‐Goldsen, 2017; Lytle, Dyar, et al., 2018; Lytle, Macdonald, et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2019; Monahan et al., 2020; Ramírez et al., 2022; Robinson‐Lane & Booker, 2017).

Accordingly, there have been repeated calls for a focus on intersecting “isms” that individuals have faced during the COVID‐19 pandemic, such as exacerbated pre‐existing ageism experienced in conjunction with elevated forms of other “isms” like ableism, racism, and sexism (Monahan et al., 2020; Robinson‐Lane et al., 2022; WHO, 2021a, 2021b). Experiencing multiple isms (e.g., ageism and sexism) may yield particularly negative consequences across multiple contexts such as the workplace (e.g., older women experiencing more job and income losses than men, and consequently being less likely to have pensions compared to older men; ILO, 2021; WHO, 2021a), and healthcare (e.g., older Asian Americans facing disproportionate mortality rates compared to non‐Hispanic Whites (Ma et al., 2021).

As further examples, results from a qualitative study of older transgender individuals living in India revealed negative healthcare experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Banerjee & Rao, 2021). Participants reported being turned away at clinics as they were told they were not first priority for COVID‐19 treatment and were instead offered HIV testing, and they reported experiencing being a low priority for other unmet needs such as financial problems that arose as a result of loss of work during the pandemic (Banerjee & Rao, 2021). As another example, structured interviews of 15 low‐wage Black workers aged 50 and older in the U.S. revealed that workers were receiving insufficient pay and health benefits, insufficient supervisor and co‐worker support, and less flexible work arrangements, which placed them at increased risk for poor mental, physical, and financial well‐being (Jason, 2022). Additionally, in‐depth interviews of 15 older Chinese adults in Canada revealed that these individuals have faced significant barriers to well‐being such as experiencing racism (e.g., being perceived as “bringing” the pandemic to Canada by out‐group community members) and ageism (e.g., feeling neglected by the Canadian government in nursing homes) (Q. Wang et al., 2021). In Nigeria, qualitative interviews of 11 older adults uncovered how ageism and classism (i.e., low access and use of digital technology among older adults across the globe) have heightened social isolation and loneliness throughout the pandemic (Ekoh et al., 2021). In this study, participants often lamented experiencing double exclusion due to enforced social distancing as well as lacking internet access, which is known to cope with social anxiety and separation, particularly during the pandemic (Mukhtar, 2020).

The aforementioned set of examples point to the negative effects of the intersections of ageism with other isms. Before the pandemic, there were multiple calls for greater attention being placed on the intersecting isms and their consequences. As such, this study aimed for the first time to conduct a systematic review of how ageism toward older adults has intersected with other isms such as ableism, classism, heterosexism, racism, and sexism during the COVID‐19 pandemic. By systematically reviewing the literature, this study aims to provide a stock take of the ways in which ageism toward older adults intersects with other isms during the pandemic within and across countries. Given concerns about the dearth of attention and research on intersectionality, this systematic review cast a wide net and included articles whose primary focus is on the intersections of ageism with other isms, but also articles that acknowledge the importance of studying intersectionality even if not a primary and secondary point of the article. Results from this review are used to make recommendations about the future study of ageism intersecting with other isms in order to inform theorizing, research, and applications.

METHODS

This paper has earned a Pre‐Registered Research Design badge, available at https://osf.io/asfnw/.

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

This systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) approach (Moher et al., 2015) and is depicted in Figure 1. First, we searched the following databases to locate relevant and potentially eligible studies published between 2019 and August 2022 with no restrictions on region, language, or publication type: APA PsycInfo APA PsycArticles, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, ERIC, Fuente Académica Plus, Gender Studies Database, LGBTQ+ Source, MEDLINE with Full Text, Social Sciences Full Text (H.W. Wilson), SocINDEX with Full Text. In Step 1, our search strategy was to combine key terms related to ageism (entering ageis* to encompass iterations of ageism such as ageist) and COVID‐19. We focused on these terms based on the Global Report on Ageism (WHO, 2021a) that uses these terms. Following our initial search which led to the identification of 354 articles, in Step 2, we removed duplicates using Endnote (n = 28). Then, in Step 3, the second author reviewed titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies. Consistent with the goals of the study, inclusion criteria are: (1) Articles must be about ageism toward older adults (i.e., the article could discuss or include data from younger groups as well; “older adult” is defined as 60 years or older based on WHO, 2021a). (2) Articles must be about the COVID‐19 pandemic. Data (empirical articles) must be collected during the COVID‐19 pandemic up until the time of data collection (September 2019 ‐ August 2022) and review papers must include coverage of the pandemic. September 2019 was used as a start date coinciding when COVID‐19 was detected in China. An article that was published during the COVID‐19 pandemic but did not include data or theorizing concerning the COVID‐19 pandemic were excluded). (3) Lastly, articles must contain information regarding isms such as ableism, classism, heterosexism, racism, and sexism which interact with ageism toward older adults. The word “intersectionality” need not be mentioned.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flowchart [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

After titles and abstracts were combed to fit the three criteria above, in Step 4, the full‐length articles of the potentially relevant studies (n = 61) were reviewed by all authors. We manually searched the reference lists of all these articles to determine if any additional articles were missed in our original search of databases; any articles with titles that might be relevant to our four criteria were obtained and reviewed (n = 16). Then, all these potentially eligible studies (n = 77) were reviewed based on the same three criteria above as well as a fourth criteria (4) article must be written in English, French, Portuguese, or Spanish, the four languages understood by the authors of this study. This led to a final list of 32 articles meeting criteria. The earliest publication date of an article fitting our criteria was December 2019.

Data analysis

We coded the final list of articles (those growing out of Step 5 above) based on the following: (1) Publication year, (2) Author(s) country, (3) Author(s) discipline, (4) Type of article (i.e., empirical study, meta‐analysis, review paper, book chapters) (5) Type of “ism” (e.g., racism, sexism, ableism,, classism, heterosexism) that intersects with ageism toward older adults, and (6) Discipline (e.g., psychology, law, gerontology). For empirical articles, we coded all of the above in addition to (7) Data collection time frame and (8) Sample description.

As noted earlier, this systematic review included not only articles whose primary focus was on the intersections of ageism with other isms, but also articles that acknowledged the value of studying intersectionality without making it the main point of the article.

RESULTS

The results of the systematic review are provided in Table 1 (all the empirical articles) and Table 2 (all the review papers) that fit our criteria: focus on ageism toward adults 60 years or older, according to WHO's (2021a) criteria, focus on ageism during the COVID‐19 pandemic, discuss or offer evidence of other isms that interact with ageism toward older adults (i.e., disability status, ethnicity, gender identity, race, sexual orientation, intersex status), and were written in one of the following languages: English, French, Portuguese, or Spanish, the four languages understood by the authors of this study.

TABLE 1.

Empirical articles in the systematic review

| No. | Author(s)/Article Publication Year | Author(s) Country | Author(s) Discipline(s) | Empirical Type | Type(s) of Ism | Data collection time frame | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arcieri (2021) | USA | Psychology | Quantitative design |

Ableism Sexism |

September ‐ December 2020 |

Surveyed online 156 participants living in the USA, via Qualtrics, from Amazon MTurk in USA |

| 2 | Bacsu et al. (2022) | Canada |

Computer Science; Health Sciences; Kinesiology; Nursing; Nutrition; Pharmacy; Psychology; Rehabilitation |

Qualitative design | Ableism |

February ‐ September 2020 |

Analyzed 1743 stigma‐related tweets using the GetOldTweets application in Python |

| 3 | Banerjee and Rao (2021) | India | Psychiatry | Qualitative design | Heterosexism |

April ‐ May 2020 |

Conducted in‐depth interviews with 10 transgender older men and women from India |

| 4 | Banerjee et al. (2021) | India | Psychiatry | Qualitative design | Ableism | April – June 2020 |

Conducted 148 semi‐ structured online interviews with psychiatrists, neurologists, general physicians involved in dementia care in multiple locations in India |

| 5 | Ekoh et al. (2021) |

Hong Kong, Nigeria, Norway |

Social Work | Qualitative design | Classism | “Data collection conducted during the first wave of the pandemic." | Conducted semi structured, in‐depth interviews with 11 older men and women from an Indigenous community in Nigeria |

| 6 | Guzman et al. (2021) | Ireland |

Geography; Public Health |

Qualitative design | Classism | “Ongoing at the time of publication” |

Conducted 46 in‐depth interviews over the phone or using video conference platforms with older men and women, living in Irish community settings |

| 7 | Q. Wang et al. (2021) | Canada | Social Work | Qualitative design | Racism | April ‐ May 2020 | Conducted 15 in‐depth interviews with Chinese adults living in Canada, using a communication mobile app or via telephone |

TABLE 2.

Review‐type articles in the systematic review

| No. | Author(s)/Article Publication Year | Author(s) Country | Author(s) Discipline(s) | Article Type | Type(s) of Ism(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akerkar (2020) | UK | Law | Opinion Piece | Ableism |

| 2 | Buffel et al. (2020) | UK | Gerontology | General Review | Classism |

| 3 | Calvo (2020) | USA | Social Work | Letter |

Classism Racism |

| 4 | Chatters et al. (2020) | USA | Social Work | General Review | Racism |

| 5 | Chigangaidze and Chinyenze (2021) | Zimbabwe | Social Work | General Review |

Ableism Classism |

| 6 | Cox (2020) | USA | Social Work | Commentary |

Classism Racism |

| 7 | D'Cruz & Banerjee (2020a) | India | Psychiatry | General Review | Sexism |

| 8 | D'Cruz & Banerjee (2020b) | India | Psychiatry | General Review |

Ableism Classism |

| 9 | Dlamini (2021) | South Africa | Sociology | General Review | Sexism |

| 10 | Ebor et al. (2020) | USA | Biobehavioral Sciences; Psychiatry | Commentary | Racism |

| 11 | Garcia et al. (2021) | USA | Sociology | General Review | Racism |

| 12 | Jen et al. (2020) | USA | Social Work | General Review | Heterosexism |

| 13 | Lee and Miller (2020) | USA |

Gerontological Social Work |

Letter |

Ableism Racism Sexism |

| 14 | Miller (2021) | USA | Gerontology | General Review | Racism |

| 15 | Monahan et al. (2020) | USA | Psychology | General Review | Racism |

| 16 | Morrow‐Howell et al. (2020) | USA | Social Policy; Psychology | General Review |

Classism Racism |

| 17 | Previtali et al. (2020) | Finland Israel Poland |

Gerontology; Social Sciences; Social Work |

General Review |

Racism Sexism |

| 18 | Putnam and Shen (2020) | Not available | Health and Public Service; Social Work | General Review | Racism |

| 19 | Rabheru and Gillis (2021) | Canada | Psychiatry; Public Administration | General Review | Ableism |

| 20 | Robinson‐Lane et al. (2022) | USA | Nursing | General Review | Racism |

| 21 | Rochon et al. (2021) |

Canada UK |

Medicine |

Commentary |

Sexism |

| 22 | Seifert et al. (2021) | Switzerland USA | Communication; Sociology; Technology | Special article | Classism |

| 23 | Shippee et al. (2020) | USA | Public Health | General Review |

Classism Racism Sexism |

| 24 | Swinford et al. (2020) | USA |

Gerontological Social Work |

General Review |

Classism Racism |

| 25 | Wilkinson (2021) | UK | Bioethics/Medicine | General Review | Ableism |

Type of isms

As seen in Table 1, empirical articles focused mainly on ableism (n = 3), followed by classism (n = 2), sexism (n = 1), racism (n = 1) and heterosexism (sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status discrimination, n = 1). As revealed in Table 2, most review articles discussed ageism with racism (n = 14), ableism (n = 6), sexism (n = 6), classism (n = 9), heterosexism (sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status discrimination, n = 1). Also, as seen in both tables, several articles covered ageism with more than one other ism. For example, Lee and Miller (2020) discuss ageism with ableism, racism, and sexism.

Type of article

As seen in Table 1, there were few empirical papers (n = 7), among which qualitative studies predominate (n = 6). As seen in Table 2, more review‐type articles that are general review papers (n = 25), including commentaries (n = 3), letters (n = 2) and opinion pieces (n = 1).

Country

As seen in Tables 1 and 2, most authors of articles work in the USA (n = 16) and then India (n = 4), Canada (n = 4), UK (n = 4), Japan (n = 1), Nigeria (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), Zimbabwe (n = 1), Poland (n = 1); Israel (n = 1); Finland (n = 1) and Ireland (n = 1) and Switzerland (n = 1). It is important to note that some articles are authored by the same team of collaborators; for example, all 4 articles from India are from the same collaborative team.

Discipline

As seen in Tables 1 and 2, most articles are from authors whose affiliation is in a department of social work (n = 10) and psychiatry (n = 6), then psychology (n = 4), medicine (n = 2), public health (n = 3), gerontology (n = 3), social sciences (n = 2), nursing (n = 2), sociology (n = 1), political science (n = 1). Most of the articles reflect one discipline, whereas 30% of the articles have authors with affiliations reflecting more than one discipline (n = 9).

DISCUSSION

The results of this systematic review reveal that ageism and its intersections with other isms during the COVID‐19 pandemic were described by scholars across disciplines and countries who noted the profoundly negative effects, but that overall, the study of the intersections of ageism and other isms is greatly understudied during this time period. Only 32 articles qualified for this systematic review from a larger possible pool of 354 articles on ageism during the almost 2‐year time window of this review.

Most of the articles were general review papers, some of which were commentaries, editorials, letters to the editor, and opinion pieces. Among the articles that conducted empirical research on ageism and other intersecting isms, six conducted qualitative research (Bacsu et al., 2022; Banerjee & Rao, 2021; Banerjee et al., 2021; Ekoh et al., 2021; Q. Wang et al., 2021), focusing on the intersections of ageism with: ableism (Bacsu et al., 2022; Banerjee et al., 2021), classism (Ekoh et al., 2021), racism (Q. Wang et al., 2021), and heterosexism (sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status discrimination) (Banerjee & Rao, 2021). These articles provide extensive details about the experiences of older adults facing multiple isms. Furthermore, multiple perspectives were given in these articles. Of these research articles, two originated in psychiatry, two in social work and one was interdisciplinary. One psychology research article had a quantitative approach and focused on the intersection between ageism and ableism (Arcieri, 2021). In reviewing both the empirical papers and review papers, we organize our discussion into a type of ism that intersects with ageism. Thereafter, we provide some implications of the results from this systematic review for future research and finally, we explore some limitations of our systematic review and propose future directions for this line of inquiry on older adults facing additional stigmas.

Brief description of empirical articles and review papers

Ageism and Ableism

Ableism is defined as prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination toward persons living with a disability (PLWD) (Bogart & Dunn, 2019). PWLD, who make up 15% of the global population (WHO, 2022), are broadly defined as persons living with a physical, cognitive (i.e., intellectual), and sensory disabilities, including those with chronic health and psychiatric conditions, and invisible disabilities (Bogart & Dunn, 2019). Older adults, in particular face significant ableism, as more than 46 percent of adults aged 60 and over live with disability(ies) (Monahan et al., under, review; UN, 2022). Beliefs about disability and aging may intertwine, as older adults and PLWD are stereotyped to have hearing, sight, cognitive, and mobility impairments. In the context of the pandemic, both groups were largely portrayed as facing significant health risks as well as weak and frail (Monahan et al., 2020). Consistently, some papers included in this review discuss the potential ageism and ableism that older adults have been facing.

Bacsu et al. (2022) attempted to gain an understanding of how social media content contributes to increasing stigma against people with dementia and their caretaking partners in the US. They analyzed 1743 tweets collected between February 15 and September 7 of 2020 and identified the four following themes (1) ageism and devaluing the lives of older adults (2) misinformation and false beliefs about dementia and COVID‐19 (3) dementia used as an insult and (4) challenging stigma against dementia. The authors concluded that social media raised attention to the serious risks of COVID‐19 for older adults living with dementia, thus amplifying ageism and stigma against older people facing dementia. To prevent stigma and the negative health outcomes associated with experiencing stigma, they recommended more comprehensive education about dementia and aging, as ageism and ableism are both global and socially condoned.

In another study concerning older adults living with dementia conducted in India, Banerjee et al. (2021), explored the experiences and barriers faced by physicians involved in dementia‐care during the COVID‐19 lockdown. They conducted 148 online in‐depth interviews with physicians including psychiatrists and neurologists who reported on their experiences caring for older adults with dementia during the lockdown. Three overarching categories emerged from the analysis: (1) telemedicine as the future of dementia care in India (2) people living with dementia being uniquely susceptible to the pandemic with a triple burden: age, ageism, and lack of autonomy and (3) markedly reduced health care access with significant mental health burden of caregivers. According to interviewees, patient‐caregiver relationships have faced significant strains, with many caretakers reporting challenges to care such as lockdown restrictions, loss of autonomy, and coercive care. The deterioration of the relationship with their caretakers has the potential to increase abuse toward older adults as well, a situation that may be further intensified in contexts where caregiving befalls on family members and dementia is considered a part of normal aging.

Only one quantitative study examined ableism with ageism in this systematic review. Drawing from Terror Management Theory (TMT) (i.e., the fear and concerns with aging and dying increase ageism toward older adults; Greenberg et al., 1986), Arcieri (2021) argued that anxiety associated with COVID‐19 would be linked to greater ageism and ableism during the pandemic. Using a correlational design, this study (N = 156 diverse adults) examined the relationship between COVID‐19 anxiety, negative attitudes towards older adults, and people living with disabilities (controlling for age, gender, and race). Results confirmed their hypotheses that greater COVID‐19 related anxiety was associated with greater negative attitudes toward older adults and people with disabilities. There was a strong correlation between ageist and ableist attitudes as well. Interestingly, hierarchical linear regression revealed that gender and ableism contributed more than COVID‐19 anxiety to explaining ageism during the pandemic. Arcieri discusses threats to mortality (i.e., during the pandemic), as well as stereotypes that older adults and PLWD are weak and frail, potentially reminding individuals of their mortality, which then appear to increase the likelihood of ageism and ableism. Arcieri (2021) also suggested that male gender norms which emphasize strength are also deleterious to views of older adults and those living with a disability.

Additional articles reviewing the intersection between ageism and ableism focused on the disadvantages faced by older adults with dementia (Chigangaidze & Chinyenze, 2021; D'Cruz & Banerjee, 2020b; Lee & Miller, 2020; Rabheru & Gillis, 2021). These papers bring attention to important concerns including that older adults with dementia experience reduced health care access and quality of care (Chigangaidze & Chinyenze, 2021. D'Cruz & Banerjee, 2020b) and are at greater risk of contagion due to impairments in understanding the risks and protective procedures of COVID‐19 (D'Cruz & Banerjee, 2020b). Isolation is an additional challenge for older adults living with dementia, as many long‐term care facilities were unable to isolate in the onset of the pandemic (D'Cruz & Banerjee, 2020b). Older adults with dementia are also at high risk of poor mental health, as older adults have faced loneliness and anxiety as a consequence of isolation measures and existential threats (Chigangaidze & Chinyenze, 2021).

Finally, Wilkinson (2021) discusses the ethical implications and challenges implied in triage decisions during the pandemic based on older adults’ frailty evaluations. Wilkinson (2021) acknowledges triage judgments of older adults’ frailty have been criticized for having the potential to discriminate against older adults, and older adults with disabilities. In addition to this, frailty rates are potentially higher among older adults from some ethnic groups and low socioeconomic status who already have greater rates of contagion, and whose health status already reflect their continued exposure to structural discrimination. These biases make them less likely to receive intensive care compared to younger groups and older adults from more privileged populations. Wilkinson argues that triage judgments on the basis of frailty are based on probability of other relevant factors (e.g., probability of survival) and that efforts have been made to correct biases against older people, and older adults with disabilities. Ultimately, Wilkinson (2021) argues that frailty‐based triage does not directly discriminate against older adults, older adults living with disability or victims of structural discrimination. Nevertheless, Wilkinson underscores the importance of attending to the social structures that contribute to inequality and striving to find ways that healthcare systems can mitigate it, thus highlighting the nuanced and sometimes controversial aspects of this debate.

In sum, ageism and ableism pose serious health risks to older adults during the pandemic, which Rabheru and Gillis (2021) highlight. In their review of the strategies to combat ageism and ableism, they ultimately discuss the need for education about aging (both formal and informal) and intergenerational contact. Rabheru and Gillis (2021) also suggest policies and laws which may better promote older adults' health such as sustainable development initiatives which increase health and longevity.

Ageism and classism

“Classism is the systematic oppression of subordinated class groups to advantage and strengthen the dominant class groups” (Bullok & Reppond, 2018, p. 225). Examining how ageism may be compounded by classism, Ekoh et al. (2021) conducted a qualitative study among older adults facing economic hardships during the pandemic. Ekoh et al. (2021) reasoned that preventative measures implemented to protect older adults (i.e., social distancing and no in‐person contact) unintentionally harmed older adults living South Nigeria, and that the lack of resources (lack of internet connection, low income, and internet fluency) exacerbated their poor health and isolation. Their study involved semi‐structured in‐depth interviews with eleven older men and women aged between 60 and 81 in an indigenous rural community in South Nigeria where many older adults faced digital exclusion and loneliness. Two themes emerged, illustrating (1) how the pandemic restrictions deprived older people of social contact and led to loneliness and (2) how many older adults were unable (or unwilling) to adopt digital technology, thus making social interactions even less feasible. Ekoh et al. (2021) discussed other aspects that contributed to deepening double exclusion such as lack of enough income to access technology, lack of technical knowledge and self‐exclusion (e.g., they are used to face‐to‐face interactions and chose not to use, or do not feel prepared to use technology). Ekoh et al. (2021) concluded that more resources are needed (e.g., social activities, access to technology) to prevent poor health and exclusion among older adults in South Nigeria. Their results highlight that social policies and programs are needed to provide social support and/or internet resources, when possible, for older adults facing economic hardships.

Other articles emerging from this systematic review underscore the effect of overlapping vulnerabilities and cumulative disadvantages of facing economic hardship among some groups of older adults during the pandemic. Intervention strategies and public policies aimed at helping people facing poverty and economic hardship may themselves become instruments of oppression (Robinson‐Lane et al., 2022; Rochon et al., 2021; Putnam & Shen, 2020; Wilkinson, 2021), when failing to acknowledge and properly consider older adults' diversity (Banerjee & Rao, 2021; Guzman et al., 2021; Lee & Miller, 2020; Robinson‐Lane et al., 2022) and needs (Calvo, 2020). One aspect that received attention directly or indirectly from several papers is technology, given its critical role in allowing individual adaptation to the challenges imposed by the pandemic. Ekoh et al. (2021) and Seifert et al. (2021) focused on how internet access and technology have become critical to the well‐being of older adults facing economic hardship (and everyone else), to the point that is should be considered a Human Right (Seifert et al., 2021). Access to information and communication technologies, devices, relevant skills, attitudes toward technology among other aspects, made a difference in older adults’ experiences during the pandemic in terms of their ability to maintain social contact, contact health and other services, obtain needed information and more. These authors discussed how the digital divide (which is economic based) interacted with age, increasing social isolation and marginalization. Also, it is noted that individuals from certain other groups may suffer marginalization from technology for other reasons like women, people with cognitive impairment, racial/ethnic and rural population to give some examples. Older adults located at the intersection with these dimensions are thus exposed to a double burden that increased their suffering during the COVID‐19 pandemic

Ageism and racism

Racism and racial and ethnic‐related health inequities have skyrocketed since the onset of the pandemic, with older adults of color facing serious consequences (UN, 2021). As one example, Q. Wang et al. (2021) argued that ageism and racism against Chinese people significantly increased during the pandemic due to a combination of public policy and faced hostility due to the belief that the virus originated in China. They conducted a study focused on the unique experience of Canadian Chinese older adults during the early stages of the pandemic. Using criterion sampling they recruited a balanced sample of 15 Chinese immigrant participants through social media or non‐profit organizations. Participants had to: be 65 years or older and had lived in Calgary for at least 10 years. Interviews were conducted in English, Mandarin or Cantonese using WeChat or telephone, translated when necessary, and transcribed. Findings suggest that participant's experiences during the pandemic were influenced by discrimination toward multiple intersecting identities: immigration, age, ethnicity and family role. For example, not only did they have to face COVID‐19 restrictions like other older adults, but some were unable to see their children and lost their support which was critical to them in the face of the pandemic. In addition, they also suffered from increased prejudice against them based on theories about the virus origin. Q. Wang et al. (2021) highlight how these participants resiliently navigated their challenges during the pandemic with the adoption of technology in their daily lives, and that future research should focus on older adults with additional marginalized identities who were not represented in the sample (e.g., marginalized sexual and gender identities).

Other articles in this systematic review bring attention to possible risks that are a byproduct of the intersection between ageism and racism, that increase the risk of detrimental outcomes in the face of COVID‐19 for older adults from ethnic and racial groups such as African Americans, Latinx in the US (Ebor et al., 2020; Ehni & Wahl, 2020; Miller, 2021) in addition to Native Americans (Lee & Miller, 2020). Monahan et al. (2020) and Swinford et al. (2020) focused on the unequal working conditions of ethnic and racial groups as well as older adults and highlighted how older adults who belong to stigmatized racial groups tend to hold jobs that that did not afford protection from COVID‐19 exposure during the pandemic (Monahan et al., 2020), and had more job‐losses than other population groups (Swinford et al., 2020), African Americans as well as less educated and lower income older adults, have been found to be at greater risk of contagion and have less access to health (Morrow‐Howell et al., 2020). It is often the case that older adults who are African American and Latinx live (more than their white counterparts) in multigenerational and multiracial households increasing their risk of contagion (Morrow‐Howell et al., 2020). This is also the case for older immigrant adults (Calvo, 2020; Previtali et al., 2020). In addition to this, Robinson‐Lane et al. (2022) and Shippee et al. (2020), point out the differences in the quality of long‐term care facilities that older adults from different racial and ethnic groups have access to. Specifically, White older adults have access to better long‐term care facilities than older adults from other groups. Robinson‐Lane et al. (2022) alert about the fact that long‐term care facilities can become the drivers of oppression and discrimination toward older adults from different backgrounds.

In the same line of reasoning, Chatters et al. (2020) and Swinford et al. (2020) focus on disparities by race and age in the healthcare system producing devastating deaths and injuries among older Black Americans during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lee and Miller (2020) highlight the uneven distribution of risk of undesired outcomes between Native American, Hispanic and African American population in comparison to White Americans. Putnam and Shen (2020) add to these considerations by broadening the scope of this analysis to include data from the US, the UK, Brazil and other nations.

In all, older adults of color face obstacles to their well‐being due to accumulated experiences of adversity (Shippee et al., 2020). Beyond bringing attention to the intersectional effects of ageism and racism, these authors offer some advice on how to better address the needs of older individuals of color in the fields of social work and sociology (Cox, 2020; Ebor et al., 2020), nursing (Robinson‐Lane et al., 2022), psychology (Monahan et al., 2020), and social policy (Morrow‐Howell et al., 2020) to remedy the structural inequalities that affect older adults' access and attention within the healthcare system.

Ageism and sexism

Sexism is defined by D'Cruz and Banerjee (2020a) as prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination against an individual, based upon their sex. Some examples of these gendered ageism provided by Rochon et al. (2021) and D'Cruz and Banerjee (2020a) point out the lack of more accurate statistics on COVID‐19 that disaggregate by sex and age. The homogenization of older adults hides the negative outcomes that older women are experiencing on their health and well‐being (D'Cruz & Banerjee, 2020a), but also, women are less likely than men to be involved in the decision making during the pandemic in private and public (e.g., policy making) settings, and they are more likely to take on the role of caretakers which limits their work and economic opportunities (Previtale et al., 2020). Also, the “young is good” stereotype for older women, imply negative effects for them in the workplace and in long‐term care facilities among others (Rochon et al., 2021). Marginalization and discrimination that affect older women (among other groups) make them more vulnerable to abuse by their partners (D'Cruz & Banerjee, 2020a; Previtali et al., 2020), family and caretakers (Dlamini, 2021). This marginalization is often deepened by their lack of access to technology. Altogether authors identify the need for better statistics (D'Cruz & Banerjee, 2020a; Rochon et al., 2021) and multi‐level future steps like interventions, and changes in social and cultural narratives of older women (Rochon et al., 2021).

Heterosexism

Treating someone less favorably than any other person because of their sexual orientation, gender identity or intersex status constitutes a form of heterosexism (Australian Human Rights Commision, 2014). In 2020, the Independent Expert at the United Nations issued a letter describing how the LGBT faced exacerbated challenges to healthcare due to the pandemic such as experiencing violence, lack of access to quality care, and social exclusion (UN, 2022). Discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, or intersex status is a serious global issue; people are subjected to the denials of their economic, social and cultural rights like health, housing, education work, to the non‐recognition of personal and family relationships, interfering with their personal dignity, and so on, in attempts to impose heterosexual norms, sometimes forcing them to remain silent and invisible, because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation and gender identity (O'Flaherty & Fisher, 2008).

Banerjee and Rao (2021) explored the experiences and psychosocial challenges of older adults from the LGBTQ community living in India during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Using purposive sampling, they contacted and conducted in‐depth interviews on the telephone with ten transgender individuals aged 60 years or older. Interviews were recorded, translated, and transcribed verbatim and then coded, using Haase's adaptation of Colaizzi's phenomenological method that involves the exploration of the subjective experiences of individuals under investigation. Upon a first round of coding, they re‐interviewed some 5 participants and modified and supplemented their data with additional information. Banerjee and Rao (2021) found three super‐arching themes: (1) marginalization, (2) the dual burden of “age” and “gender” and (3) multi‐faceted survival threats during the pandemic. Social rituals, spirituality, hope, and acceptance of “gender dissonance” emerged as the main coping factors. Unmet needs for social inclusion, awareness related to COVID‐19, mental health care, and a deaf audience to their distress suggest that older transgender adults experienced increased emotional and social risks during the COVID‐19 pandemic in association to their LGBTQ identity. Banerjee and Rao (2021) point out the need for policy implementation and community awareness vital to improving older transgender adults’ health and well‐being.

In a letter to the editor, Jen et al. (2020) bring attention to the challenges faced by older members of the LGBTIQA+ community during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Robinson‐Lane et al. (2022) discuss discrimination that negatively impacts older people with diverse gender and sexual identities, highlighting that LGBTQ older adults often encounter: admissions processes and paperwork that don't recognize their gender and sexual identities, denial of admission, maltreatment by long‐term care facilities’ staff, isolation and discrimination from other residents, all of which have led many LGBTQA+ older adults to conceal their identities after having been open in the community. All together, these experiences exemplify how LGBTQA+ older adults have faced significant barriers to health throughout the pandemic. (Lee & Miller, 2020)

Implications for research

The COVID‐19 pandemic has represented a challenge for the world population, generating needs for adjustment in a context in which fear, uncertainty and injustice have too often prevailed. A highly stressful environment is an environment in which threats thrive, and virtually become naturalized (Lamont et al., 2015). In our article, the different isms we found to intersect with ageism represent this threat perpetuated over time. Structural conditions, such as the case of policies motivated by the fear of contagion and the imminent need to control morbidity and mortality resulted in a negative visibility of older adults that reinforced negative stereotypes of old age and aging, age discrimination and prejudice toward older adults. Older adults’ basic needs (e.g., those related to health‐disease processes) were minimized, as older adults were considered expendable (Morrow‐Howell et al., 2020) due to false beliefs (e.g., all older adults have disabilities), having potentially multiple comorbidities, and other misconceptions. These misbeliefs ultimately yielded serious ageism, affecting the quality of life and wellbeing throughout the pandemic.

Through this systematic review, we confirm the multidisciplinary and international interest in understanding and explaining different forms of ageism that older adults are subjected to, by virtue of other interlocking identities making their lives more difficult, not only during the pandemic but also in their day to day lives during non‐pandemic times. Some of the above reviewed articles did declare using a framework of intersectionality while others did not. Instead, they used related terms such as double and triple jeopardy, interlocking identities, multiple deprivations, and structural discrimination, which are useful to approach and understand oppression from different perspectives in society. This systematic review suggests the contribution of intersectionality as a transdisciplinary “umbrella” that can be used by professionals from several disciplines (e.g., gerontology, medicine, social work, nursing, psychology) to understand and intervene discrimination using an integrative framework.

We found that empirical research on ageism and its intersection with isms during the pandemic is scarce, with a frank predominance of qualitative research on five types of isms interacting with ageism: ableism, classism, heterosexism, racism, and sexism. For the most part, qualitative data was analyzed using thematic analysis (Banerjee et al., 2021), one of them with the Colaizzi phenomenological method (Banerjee & Rao, 2021). Findings from these studies suggest that ableism is sometimes closely linked to cognitive decline in older adults, commonly represented as dementia (Banerjee & Rao, 2021). During the pandemic, especially during its first peaks, this type of ableism entailed important difficulties limiting access to health services (Morrow‐Howell et al., 2020; Wilkinson, 2021) and in providing care for older people (Banerjee et al., 2021).

Throughout this review, it has become evident that failing to recognize diversity among older adults represents a major issue of concern with the potential to put at risk older adults from specific groups of population. Women (D'Cruz & Banerjee, 2020a; Rochon et al., 2021), LGBTQA+ older adults (Robinson‐Lane et al., 2022), older adults from racial groups (Cox, 2020; Ebor et al., 2020), and possibly others not yet identified by academic literature on intersectionality, may face even life‐threatening risks when services supposed to help them apply the wrong standards and fail to recognize proper ways to support their needs.

It is important to highlight that ageism and its intersections with other isms as described above were not necessarily experienced in the same way by individuals within or across countries. The relatively small set of articles qualifying for this systematic review made it challenging to uncover possible unique experiences and implications by culture and context. For example, older women in one community may experience different forms of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination than older women in another community. Some articles however, highlighted the importance of understanding cultural aspects that contribute to tint the problem with a particular shade (e.g., the risk of violence against older adults among societies were caretakers are mainly their own families)

Limitations and future directions

Our search strategy has limitations such as combining key terms related to ageism (entering ageis* to encompass iterations of ageism such as ageist) and COVID‐19. We focused on these terms based on the Global Report on Ageism (WHO, 2021a) that uses these terms. However, some scholars and particularly some countries may not use “ageism” or “ageist” to describe stereotyping, prejudice, or discrimination toward older adults. Not all these articles mention the word “intersectionality”; some of them use other terms such as double jeopardy, multiple deprivation, interlocking or combined effects of X and Y forms of prejudice, arising from social relations, system biases or both.

Because our review focused on the intersections of ageism and other isms during the COVID‐19 pandemic, which is a global health crisis, most articles focused on healthcare‐related inequalities or focused on inequalities broadly across settings. Pre‐COVID‐19, both healthcare settings and the workplace were highlighted as settings in which ageism frequently occurred (Macdonald & Levy, 2016). The COVID‐19 pandemic greatly impacted the workplace, travel, social relationships, education, and thus greater attention to intersectionality needs to be given in those other contexts and across contexts.

It should also be noted that results of this review are also affected by how the COVID‐19 pandemic influenced publishing of commentaries, reviews, and empirical studies. There was an urgency to conduct studies, share findings, and make calls to action, and as such, some articles did not go through the more rigorous pre‐COVID‐19 pandemic review process. As an example, it was more difficult than usual to obtain reviewers since the pandemic was overwhelming for societies as a whole. Thus, editors had to rely on whoever was available, fewer reviewers per submission, and utilize reviewers whose expertise may have been outside the scope of the articles. The rush of authors to prepare commentaries and conduct studies and the use of fewer reviewers and/or reviewers with less expertise could contribute to lower quality articles during the COVID‐19 pandemic for all areas of research. In terms of the current systematic review, there are few empirical papers, which vary on many variables; thus, making it difficult to systematically draw conclusions about the quality of the research studies.

The small number of articles that met criteria overall for this systematic review and the even smaller number of empirical articles that met criteria is noteworthy in that it shows a gaping hole in attention to this line of research on intersectionality. Only 32 studies emerged overall, and six of them were not primarily focused on the intersection of ageism and other isms. The articles that did not have in‐depth examination were: Calvo (2020), Guzman et al. (2021), Miller (2021), Putnam and Shen (2020), Shippee et al. (2020) and Swinford et al. (2020). As noted, there were only seven empirical studies and only one quantitative study that met criteria for this systematic review. There are other isms which intersect with ageism (e.g., sizeism, religious discrimination) that did not emerge in this review. Together, this calls attention to how intersectionality remains an understudied and underrecognized perspective across multiple fields such as psychology, gerontology, psychiatry, and public health. An open question is why is this so? Is it that this line of inquiry is undervalued? Are there fewer individuals trained in conducting intersectional research? It has been repeatedly noted that ageism toward older adults is understudied in general relative to other isms and that ageism is potentially more institutionalized (Levy et al., 2022; Nelson, 2005; WHO, 2021a), which could contribute to the low number of articles qualifying for this systematic review. There is likely a myriad of reasons for the gaping hole in attention to the intersections of ageism and other isms. What is clear is that people have and are perceived by their multiple identities, people may experience negative consequences through the interaction of their multiple identities, and that research to date is not adequately addressing intersectionality.

Implications for social policy and programs

While more basic research is needed on the intersections of ageism and other isms, results from this systematic review point to the urgent need to make progress in reducing ageism along with other intersecting isms. There is a growing literature on effective strategies for reducing ageism with interventions focused on two key components as described by the PEACE (Positive Education about Aging and Contact Experiences) model (Levy, 2018): (1) increasing education about what ageism and accurate information about the process of aging and (2) increasing positive intergenerational interactions (Apriceno & Levy, under review; Burnes et al., 2019). Education about aging such as about middle and older adulthood is needed since some school systems have minimal education about aging and miseducation about aging is received from the mass and social media (Levy & Gu, in press; Palmore, 1989; Whitbourne & Montepare, 2017). In many societies ageism is socially accepted and hate speech during the pandemic attested to this (Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al., 2020; Lichtenstein, 2021; Ng et al., 2021; Sipocz et al., 2021; Skipper et al., 2021; Xiang et al., 2021), and thus raising awareness about what ageism is—and how it is socially communicated—is a crucially important step (Lytle & Levy, 2022; Okun & Ayalon, 2022). Raising awareness about the intersections of ageism with other isms is likewise needed. Heightened intergenerational tensions during the pandemic (Drury et al., 2022; Kanik et al., 2022; Lytle et al., 2022; Spaccatini et al., 2022; Sutter et al., 2022), highlight the continued need to foster positive intergenerational relations (Jarrott et al., 2022). Fostering positive intergenerational relations should also take into account younger and older participants' multiple identities.

Several articles in this special issue in the Journal of Social Issues highlight interventions that are being conducted at the global, country, community, and individual levels and attention to older individuals facing multiple isms can be incorporated into those interventions. As one example, Montepare and Brown (2022) describe the global Age‐Friendly University (AFU) initiative that addresses ageism and age‐inclusivity in over 80 university settings in Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America. Inclusivity by age and other factors are part of the 10 key principles of the AFU; thus, showing potential for being a welcoming and accessible environment for older individuals facing multiple identities and isms. As another example of grassroots organizing, Okun and Ayalon (2022) describe three different social media campaigns in Israel whose primary aim was to educate about ageism experienced by older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Discussions of the experiences of older adults facing multiple isms could be added to such campaigns through the podcasts, interviews, art exhibits, and short videos used. Furthermore, Jarrott et al. (2022) review four long‐standing intergenerational programs in five U.S. states adopted during the COVID‐19 pandemic to foster positive intergenerational attitudes and relationships. One of the programs collaborated with English and Spanish‐speaking older adults who were facing extreme hardships, and such programs could be a springboard for other community‐level programs with older individuals facing multiple isms. Lytle and Levy (2022) describe an online PEACE model intervention that is somewhat easily administered like the social media campaigns described by Okun and Ayalon (2022) and included education about ageism and exposure to positive intergenerational information. Their intervention involved college students and young adults in the broader community in the U.S. during the COVID‐19 pandemic who viewed brief videos addressing ageism and with special attention to the ways in which older adults are contributors to society (volunteers; grandchildren caregiving, administering vaccines) and positive intergenerational examples. Promising results showed that participants in the intervention condition compared to participants watching control videos reported more positive views of older adults and their contributions to society. Such an intervention could be adapted to teach about the ageism experienced by older individuals with multiple stigmas and highlighting their contributions to society.

Articles part of this systematic review point to several important aspects relevant to public policy that are necessary to be able to attend to the needs of older adults facing multiple isms. It is crucial to consider that depending on the culture and context, experiences of ageism intersecting with other isms may vary and with different implications. Turning basic research findings into effective tailored programs and policies often requires collaborations among researchers, practitioners, and community stakeholders who are most familiar with the unique community context, needs, and possible obstacles (Aboud & Levy, 1999; Levy et al., 2022).

Such collaborations are necessary to collect data disaggregated by age and other identities (e.g., disability status, ethnicity, indigenous status, race, sex, sexual orientation). Several authors of articles in this systematic review expressed their concern about the lack of statistics that adequately represent older adults. Rochon et al. (2021) and D'Cruz and Banerjee (2020a) pointed out the lack of more accurate statistics on COVID‐19 disaggregated by sex and age. COVID‐19 statistics tended to homogenize across age groups and gender. As pointed out by these authors, public policy design requires better knowledge of older adults' realities. Older adults, like any other social category, are diverse and this diversity should be incorporated in public policy design to be effective, which is not possible if it is blind to the needs of the population that it is trying to attend. Older adults oppressed by the effect of other stigmas have different life experiences and thus may have different needs in terms of health, recreation, family life, education, etc. To illustrate, medical decisions may fail to acknowledge older adults' diversity in terms of ethnicity or socioeconomic situation with important consequences for their well‐being (Chatters et al., 2020). Wilkinson (2021) brings forward important ethical considerations regarding decisions that involve resource allocation throughout the pandemic and beyond.

A blind policy, built upon one‐size‐fits‐all statistics may lead other services to discriminate against more vulnerable older adults because they are informed by the wrong assumptions. Interestingly, all sources of discrimination reported or reviewed in intersectionality articles identified long term care facilities as critical to the wellbeing of older adults. This is another example where recognizing older adults' diversity would be of great help to improve their attention and combat prejudice. As stated by one of the authors reviewed above, long‐term care facilities can become the drivers of oppression and discrimination toward older adults from different backgrounds (Robinson‐Lane et al., 2022). Consistently, several authors identified long‐term care facilities as an important source of discrimination for women (Rochon et al., 2021), ethnic groups (Robinson‐Lane et al., 2022; Shippee et al., 2020), LGBTQ older adults (Chatters et al., 2020), and older adults with dementia (Rabheru & Gillis, 2021). Consistently, long‐term care facilities seem to be critical places where multi‐level interventions are needed to change cultural narratives of older people (Rochon et al., 2021).

Policies and programs that increase community members’ access to internet services and other technological issues were crucial during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and this systematic review draws attention to the importance of the further development and expansion of these policies and programs for older adults and older adults facing multiple stigmas (also see Jarrott et al., 2022; Montepare & Brown, 2022; Okun & Ayalon, 2022). During the pandemic, technology and the internet proved to be vital aspects of current life with the potential to mediate and facilitate access to public and private services, information and social life among other things. However, technology also has the potential to or lack thereof to intensify structural biases as in the case of participants from Mukhtar (2020)’s study which lamented experiencing social distancing and lacking internet access (removing a known way that people cope with social anxiety and separation); was even more pronounced for older adults facing the intersection with other discriminated identities (Ekoh et al., 2021). Positive intergenerational contact can be a great source of encouragement and support for older adults (Jarrott et al., 2022; Levy, 2018; Okun & Ayalon, 2022). As seen in the Q. Wang et al. (2021) study, older adults can be supported in using technology, when needed and desired from sources including intergenerational support. In this sense, technology need not be a source of intergenerational distance but quite the opposite (for an intergenerational intervention involving sharing technology knowledge see Lytle et al., 2020). All in all, these findings call attention to the need for programs and policies to address internet and technology gaps that are contributing to worsening isolation, loneliness, and reduced health among older adults and those facing multiple stigmas.

In the adaptation, creation, and implementation of all policies and programs for older adults facing multiple isms, it is imperative that older adults are collaborators and that they have full participation (Levy et al., 2022). The COVID‐19 pandemic has spotlighted human rights violations toward older adults including both their right to protection (e.g., from abuse and violence) and their right to participation (Levy et al., 2022; Seifert et al., 2021). As is the case with all intervention programs, it is essential that the quality of programs be considered, and that whenever possible, the programs are evaluated for quality and effectiveness.

CONCLUSIONS

Ageism is a worldwide social problem that has long had vast effects on employment, healthcare, and housing for individuals, communities, and countries (Abrams et al., 2016; Ayalon & Tesch‐Römer, 2018; Chang et al., 2020; Levy et al., 2022; Macdonald & Levy, 2016; Nelson, 2005; WHO, 2021a). This was a unique systematic review of articles investigating how ageism has intersected with other isms (e.g., ableism, racism, sexism) during the COVID‐19 pandemic with compounding effects on individuals with attention to articles published in English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish. Across articles, the most attention was to the intersections between ageism and ableism or racism and less so with heterosexism. Other potentially relevant “isms” were missing completely from the review, including sizeism and isms based on religious affiliation. Most articles that emerged in the systematic review were review papers which highlight the significant gap in empirical research on this topic. The empirical studies which tended to be qualitative studies all converge on the poor treatment of older adults facing multiple stigmas. Thus, there is an urgent need to conduct more empirical research on the intersections of ageism and other isms. While articles emerged from Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America, no articles emerged from Australia and South America. Wider global attention on this topic is especially needed since experiences of ageism intersecting with other isms might be quite different and also have different implications depending on the country and context. This systematic review points to the need to raise awareness about the multiple forms of ageism that older adults are experiencing and the need for intergenerational interventions to consider that older adult participants have potentially multiple stigmatized identities and thus experience multiple barriers to their health and well‐being.

Biographies

Luisa Ramírez is currently a Professor of Psychology at Universidad del Rosario, Colombia. Her research interests include lay beliefs, prejudice and discrimination against older people, women, Afro‐Colombians, ex‐combatants and other social groups, climate change education, and their implications for social policy and inclusion. She recently developed and published a virtual learning environment to help school‐teachers improve their competences to deal with conflict within the school, available at: https://eco‐geste.herokuapp.com/ . Dr. Ramírez earned a masters’ degree in Political Science at Universidad de Los Andes in Colombia in 2001, and her PhD in Social Psychology at Stony Brook University in New York in 2007.

Caitlin Monahan, MA is a doctoral candidate in the psychology department at Stony Brook University, NY in the USA. Her research focuses on stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination toward various groups such as older adults and older women in various contexts such as the workplace, healthcare, and the media.

Ximena Palacios‐Espinosa is a Professor of Psychology at Universidad del Rosario, Colombia. Dr. Palacios earned a master's degree in Clinical and Health Psychology at Universidad de Granada (Spain) in 2000, and a Doctorate in Social Psychology at Universita di Bologna in Italy in 2013. Her research interests include psychological and social aspects of physical chronic illness and palliative care, stereotyping and prejudice against older people and women.

Sheri R. Levy is a Professor of Psychology at Stony Brook University, NY in USA and UN NGO SPSSI Representative, focusing on aging, climate justice, eliminating racism, gender equality, and human rights. Levy's research team conducts basic and applied research on stereotyping, prejudice, discrimination, and intergroup relations. Levy was Editor‐in‐Chief of JSI (2010‐2013). She created a web‐based resource called “Taking Ageism Seriously” (https://takingageismseriously.org/). Levy received her Ph.D. at Columbia University, NY, USA.

Ramirez, L. , Monahan, C. , Palacios‐Espinosa, X. & Levy, S.R. (2022) Intersections of ageism toward older adults and other isms during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Social Issues, 78, 965–990. 10.1111/josi.12574

REFERENCES

- Abrams, D. , Swift, H.J. & Drury, L. (2016) Old and unemployable? How age‐based stereotypes affect willingness to hire job candidates. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 105–121. 10.1111/josi.12158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboud, F. E. & Levy, S. R. (1999) Are we ready to translate research into programs? Journal of Social Issues, 55, 621–626. 10.1111/0022-4537.00138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Akerkar, S. (2020) Affirming radical equality in the context of COVID‐19: human rights of older people and people with disabilities. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 12(2), 276–283. 10.1093/jhuman/huaa032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apriceno, M. & Levy, S. R. (under review). A meta‐analytic review of the effective program for reducing ageism toward older adults. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Apriceno, M. & Levy, S.R. (2019) Racism and ageism. In Gu D. & Dupre. M. (Eds), Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging. Cham: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-69892-2_601-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Arcieri, A.A. (2021) The relationships between COVID‐19 anxiety, ageism, and ableism. Psychological Reports, 125(5), 2531–2545. 10.1177/00332941211018404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Human Rights Commission . (2014) Sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status discrimination. Retrieved from https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/GPGB_sogiis_discrimination_0.pdf?_ga=2.94724447.2126210769.1664568245‐738504829.1664568245

- Ayalon, L. , Chasteen, A. , Diehl, M. , Levy, B. , Neupert, S.D. , Rothermund, K. , et al. (2020) Aging in times of the COVID‐19 pandemic: avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity. Journal of Gerontology Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences Series b, 76(2), e49–e52. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L. & Tesch‐Römer, C. (Eds). (2018) Contemporary perspectives onageism. Cham: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_32 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Bacsu, J.D. , Fraser, S. , Chasteen, A.L. , Cammer, A. , Grewal, K.S. , Bechard, L.E. , et al. (2022) Using Twitter to examine stigma against people with dementia during COVID‐19: infodemiology study. JMIR Aging, 5(1), e35677 10.2196/35677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Banerjee, D. & Rao, T.S. (2021) "The Graying Minority”: lived experiences and psychosocial challenges of older transgender adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic in India, a qualitative exploration. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 604472. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.604472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Banerjee, D. , Vajawat, B. , Varshney, P. & Rao, T.S. (2021) Perceptions, experiences, and challenges of physicians involved in dementia care during the COVID‐19 Lockdown in India: a qualitative study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 615758. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.615758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, A.E. , Michael, C. & Padavic, I. (2021) Calculated ageism: generational sacrifice as a response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Gerontology Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences Series B, 76(4), e201–e205. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, Y.S. , Cohen‐Fridel, S. , Shrira, A. , Bodner, E. & Palgi, Y. (2020) COVID‐19 health worries and anxiety symptoms among older adults: the moderating role of ageism. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(11), 1371–1375. 10.1017/s1041610220001258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart, K.R. & Dunn, D.S. (2019) Ableism special issue introduction. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 650–664. 10.1111/josi.12354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Buffel, T. , Doran, P. , Goff, M. , Lang, L. , Lewis, C. , Phillipson, C. , et al. (2020) Covid‐19 and inequality: developing an age‐friendly strategy for recovery in low income communities. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 21(4), 271–279. 10.1108/QAOA-09-2020-0044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, H. E. & Reppond, H. A. (2018) Of “Takers” and “Makers”: a social psychological analysis of class and classism.', in Hammack P. L. (ed.), The oxford handbook of social psychology and social justice. Oxford Library of Psychology. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199938735.013.26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnes, D. , Sheppard, C. , Henderson, C.R. , Wassel, M. , Cope, R. , Barber, C. , et al. (2019) Interventions to reduce ageism against older adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 109(8), e1–e9. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Calvo, R. (2020) Older Latinx immigrants and covid‐19: a call to action. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6‐7), 592–594. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1800884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.‐S. , Kannoth, S. , Levy, S. , Wang, S.‐Y. , Lee, J.E. & Levy, B.R. (2020) Global reach of ageism on older persons’ healt systematic review. PLoS ONE, 15(1), e0220857. https://doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0220857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Chatters, L.M. , Taylor, H.O. & Taylor, R.J. (2020) Older Black Americans during COVID‐19: race and age double jeopardy. Health Education & Behavior, 47(6), 855–860. 10.1177/1090198120965513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidambaram, P. (2020) State reporting of cases and deaths due to COVID‐19 in long‐term care facilities. KFF.org. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue‐brief/state‐reporting‐of‐cases‐and‐deaths‐due‐to‐covid‐19‐in‐long‐term‐care‐facilities/ [Google Scholar]

- * Chigangaidze, R.K. & Chinyenze, P. (2021) Is it “Aging” or Immunosenescence? The COVID‐19 biopsychosocial risk factors aggravating immunosenescence as another risk factor of the morbus. A developmental‐clinical social work perspective. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 64(6), 676–691. 10.1080/01634372.2021.1923604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisler, J.C. , Barney, A. & Palatino, B. (2016) Ageism can be hazardous to women's health: ageism, sexism, and stereotypes of older women in the healthcare system. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 86–104, 10.1111/josi.12157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn‐Schwartz, E. , Finlay, J.M. & Kobayashi, L.C. (2022) Perceptions of societal ageism and declines in subjective memory during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Longitudinal evidence from US adults aged ≥55 years. Journal of Social Issues, 78(4), 924–938. 10.1111/josi.12544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, C. (2020) Older adults and Covid 19: social justice, disparities, and social work practice. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6/7), 611–624. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1808141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. (1991) Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * D'Cruz, M. & Banerjee, D. (2020a) An invisible human rights crisis: the marginalization of older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic—an advocacy review. Psychiatry Research, 292: 113369. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * D'Cruz, M. & Banerjee, D. (2020b) Caring for persons living with dementia during the COVID‐19 pandemic: advocacy perspectives from India. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 603231. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.603231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrer‐Merk, E. , Reyes‐Rodriguez, M.‐F. , Salazar, A.‐M. , Guevara, M. , Rodriguez, G. , Fonseca, A.‐M. , et al. (2022) Is protecting older adults from COVID‐19 ageism? A comparative cross‐cultural constructive grounded theory from the United Kingdom and Colombia. Journal of Social Issues, 78(4), 900–923. 10.1111/josi.12538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Dlamini, N.J. (2021) Gender‐based violence, twin pandemic to COVID‐19. Critical Sociology, 47(4/5), 583–590. 10.1177/0896920520975465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, L. , Abrams, D. & Swift, H. J. (2022) Intergenerational contact during and beyond COVID‐19. Journal of Social Issues, 78(4), 860–882, 10.1111/josi.12551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Ebor, M.T. , Loeb, T. B. & Trejo, L. (2020) Social workers must address intersecting vulnerabilities among noninstitutionalized, black, latinx, and older adults of color during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6‐7), 585–588. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1779161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehni, H.J. & Wahl, H.W. (2020) Six propositions against ageism in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4‐5), 515–525. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1770032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Ekoh, P.C. , George, E.O. & Ezulike, C.D. (2021) Digital and physical social exclusion of older people in rural nigeria in the time of COVID‐19. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 64(6), 629–642. 10.1080/01634372.2021.1907496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, S. , Lagacé, M. , Bongué, B. , Ndeye, N. , Guyot, J. , Bechard, L. , et al. (2020) Ageism and COVID‐19: what does our society's response say about us? Age and Ageing, 49(5), 692–695. 10.1093/ageing/afaa097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Garcia, M.A. , Homan, P.A. , García, C. & Brown, T.H. (2021) The color of COVID‐19: Structural racism and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on older Black and Latinx adults. Journal of Gerontology Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences Series B, 76(3), e75–e80. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. , Pyszczynski, T. & Solomon, S. (1986) The causes and consequences of a need for self‐esteem: a terror management theory. In Public self and private self. (pp. 189–212). Springer Series in Social Psychology, New York, NY: Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4613-9564-5_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Guzman, V. , Pertl, M. , Doyle, F. & Foley, R. (2021) Older people's aspirations for the aftermath of COVID‐19: findings from the WISE study. European Journal of Public Health, 31(Supplement_3), ckab165–098, 10.1093/eurpub/ckab165.098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ILO (2021) Fewer women than men will regain employment during the COVID‐19 recovery says ILO. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/global/about‐the‐ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_813449/lang–en/index.htm

- Jarrott, S.E. , Leedahl, S.N. , Shovali, T.E. , De Fries, C. , DelPo, A. , Estus, E. et al. (2022) Intergenerational programming during the pandemic: Transformation during (constantly) changing times. Journal of Social Issues, 78(4), 1038–1065. 10.1111/josi.12530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason, K. (2022) Older black workers' resilience: navigating work and health risks with chronic conditions. Sociation, 21(1), 41–58. https://pages.charlotte.edu/kendra‐jason/wp‐content/uploads/sites/407/2022/05/Jason‐2022‐Older‐Black‐Workers‐Resilience.pdf [Google Scholar]

- * Jen, S. , Stewart, D. & Woody, I. (2020) Serving LGBTQ+/SGL elders during the Novel Corona Virus (COVID‐19) pandemic: striving for justice, recognizing resilience. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6/7), 607–610. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1793255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez‐Sotomayor, M.R. , Gomez‐Moreno, C. & Soto‐Perez de Celis, E. (2020) Coronavirus, ageism, and Twitter: an evaluation of tweets about older adults and COVID‐19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(8 ), 1661–1665. 10.1111/jgs.16508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönson, H. & Taghizadeh Larsson, A. (2021) Ableism and ageism. In Gu D. & Dupre M.. (Eds), Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging. (pp. 4–9). Cham: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-22009-9_581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanık, B. , Uluğ, Ö.M. , Solak, N. & Chayinska, M. (2022) “Let the strongest survive”: Ageism and social Darwinism as barriers to supporting policies to benefit older individuals. Journal of Social Issues, 78(4), 790–814. 10.1111/josi.12553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]