Abstract

Objective

To assess the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) in countries of the former Yugoslavia.

Method

Women giving birth in a facility in Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, and Bosnia‐Herzegovina between March 1, 2020 and July 1, 2021 answered an online questionnaire including 40 WHO standards‐based quality measures.

Results

A total of 4817 women were included in the analysis. Significant differences were observed across countries. Among those experiencing labor, 47.4%–62.3% of women perceived a reduction in QMNC due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, 40.1%–69.7% experienced difficulties in accessing routine antenatal care, 60.3%–98.1% were not allowed a companion of choice, 17.4%–39.2% reported that health workers were not always using personal protective equipment, and 21.2%–53.8% rated the number of health workers as insufficient. Episiotomy was performed in 30.9%–62.8% of spontaneous vaginal births. Additionally, 22.6%–55.9% of women received inadequate breastfeeding support, 21.5%–62.8% reported not being treated with dignity, 11.0%–30.5% suffered abuse, and 0.7%–26.5% made informal payments. Multivariate analyses confirmed significant differences among countries, with Slovenia showing the highest QMNC index, followed by Croatia, Bosnia‐Herzegovina, and Serbia.

Conclusion

Differences in QMNC among the countries of the former Yugoslavia during the COVID‐19 pandemic were significant. Activities to promote high‐quality, evidence‐based, respectful care for all mothers and newborns are urgently needed. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04847336.

Keywords: Bosnia‐Herzegovina, childbirth, COVID‐19, Croatia, IMAgiNE EURO, maternity, newborns, quality of care, Serbia, Slovenia

Synopsis

Quality of maternal and newborn care during the COVID‐19 pandemic varied greatly between Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia‐Herzegovina, and Serbia, with significant room for improvement.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the 1970s, all practicing physicians in the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia were part of a socialized health sector working as salaried staff at health facilities—a system American health economist Benjamin Ward referred to as the “Sweden of the Balkans”. 1 By 1991, when Yugoslavia dissolved, its health system had already become similar to that of European countries, 1 financed by a mixed social insurance and taxation‐based system, 2 municipally funded and decentralized. 3 Pregnant women and children had (and continue to have) free access to healthcare services. 4

Later, political and economic turbulence in the 1990s—in some countries accompanied by war—profoundly changed the delivery of health care. 4 Newly formed states (i.e. Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia‐Herzegovina, and Serbia) implemented healthcare system reforms, with uneven processes and impact. 3 Improvements in neonatal care were impressive after the 1990s, mostly due to investments in intensive care services, improved capacities, and introduction of new technologies and therapies that improved survival rates for premature infants and mothers. 3 This translated into major improvements in infant and maternal mortality rates and in other key indicators over the last 30 years, as well as a significant increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and health expenditure as a percentage of GDP (Supporting Information Table 1). Currently, most indicators relevant to maternal and newborn health care are fairly aligned across the four countries (Table 1). However, there are some important differences in reported maternal mortality rates, with rates significantly lower in Croatia and Slovenia compared with Serbia and Bosnia‐Herzegovina (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Key demographics and maternal and newborn healthcare indicators in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia‐Herzegovina, and Serbia

| Indicators | Slovenia a | Croatia b | Bosnia‐Herzegovina c | Serbia d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhabitants (year) | 2 100 126 | 4 065 253 (2019 5 ) | 3 492 000 6 | 6 945 235 |

| Live births | 19 054 | 36 166 | 28 360 7 | 61 692 8 |

| Live births per 1000 inhabitants (year) | 8.8 | 8.9 (2019) | 8.6 | 8.9 |

| Antenatal care provided by | Obstetrician Gynecologist (5 out of 10 prenatal visits can be provided by a midwife) |

Obstetrician Gynecologist 9 |

Obstetrician Gynecologist | Obstetrician Gynecologist 10 |

| No. of prenatal visits and ultrasound examinations for normal pregnancy |

10 visits 2 ultrasounds |

10 visits 3 ultrasounds 9 |

10 visits ultrasound every 4 weeks |

9 visits 4 ultrasounds 10 |

| % of women attending at least 4 antenatal care visits (any healthcare provider) | 98% | 99% | NA | 96.6% |

| % of all live births born in facilities | 99.6% | 99% | 99% 11 | 99.8% |

| No. of midwife‐led units or birth centers (% of all live births) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| No. of private maternity hospitals (% of all live births) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.4%) 12 | 4 (<1%) | N/A |

| % of births by cesarean | 21.3% | 26.6% | 28.2% | 31.8% (2019) 13 |

| Average age of mother at first birth, year | 31 | N/A | 27.7 | 30.1 |

| % of mothers aged under 20 years | 1.1% | 2.1% | 3% | 3.9% |

| % of mothers aged 35 years or more | 21.6% | 23.5% | 16% | 20.8% |

| % of live births before 37 weeks of gestation | 6.8% | 6.8% (2019) | 3.4% | 6.4% |

| Perinatal mortality rate 500 g + per 1000 births (year) | 6.07 | 6.1 (2019) | NA | 7.8 |

| Maternal mortality ratio per 100 000 live births (year or period) | 5.0 (2015–2017 average) | 8 (2017) 14 | 10 (2017) 15 | 8.8 (2013–2017 average) 16 |

Slovenia: unless otherwise noted, all data are for 2020 and taken from. 17

Croatia: unless otherwise noted, all data are for 2020 and taken from. 18

Bosnia‐Herzegovina: unless otherwise noted, all data are for 2019 and from. 11

Serbia: unless otherwise noted, all data are for 2019 and from. 8

Few previous studies on women's perceptions of maternal and newborn health care have been conducted in countries of former Yugoslavia. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 The present study was conducted within a larger project called IMAgiNE EURO and aimed to investigate the quality of maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth at facility level in different phases of the COVID‐19 pandemic and compare findings across the four countries of former Yugoslavia.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross‐sectional study was conducted according to STROBE guidelines for cross‐sectional studies (Supporting Information Table 2). 24

Women aged 18 years and over who gave birth in a facility in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia‐Herzegovina, and Serbia between March 1, 2020 and July 1, 2021 (16 months) were included in the study—a period that included the first three waves of the COVID‐19 pandemic. 25 Women who did not meet the above criteria, declined participation, or who gave birth outside a hospital facility were excluded.

2.1. Data collection

An online survey was made available in 23 languages, including the languages of these four countries. Participants could choose their language regardless of the country they gave birth in. Data collection timelines for each country are available in Supporting Information Table 3.

Data collection methods and questionnaire development and validation have been reported elsewhere. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 Briefly, data were collected using a structured online validated questionnaire, based on World Health Organization (WHO) standards 30 and recorded using REDCap 8.5.21 (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA) through a centralized platform. The questionnaire included 40 questions on one key indicator each, equally distributed in four domains: the three domains of the WHO standards, 30 namely provision of care, experience of care, and availability of human and physical resources, plus an additional domain on key organizational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Each country research team adopted predefined dissemination plans to recruit participants, including social media, organizational websites, and mailing lists, as well as local networks (parent groups, institutional networks).

Two versions of the questionnaire were available, one tailored for women who experienced labor and one for women who did not. Each included the 40 WHO standard‐based prioritized quality measure with 34 measures in common. Labor was defined according to NICE guidelines. 31 Questions worded in an easy‐to‐understand way were embedded in the questionnaire and participants self‐identified whether they belonged to the labor or nonlabor group. The questionnaire was validated through a process reported elsewhere. 28 The 40 quality measures contributed, through a predefined score system, 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 32 , 33 to a composite quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) index, which was developed drawing on previous examples 34 as a complementary synthetic measure of QMNC. The QMNC index ranged from 0–100 for each of the four domains, for a total range from 0–400 points, with higher scores indicating higher adherence to WHO standards (Supporting Information Tables 4 and 5; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) index by country a

| QMNC index | Overall (n = 3709) | Slovenia (n = 1891) | Croatia (n = 785) | Serbia (n = 699) | Bosnia‐Herzegovina (n = 334) | Comparison among all countries, P value | Pairwise comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | |||

| Provision of care | 80.0 [65.0–90.0] | 85.0 [80.0–95.0] | 80.0 [65.0–90.0] | 55.0 [45.0–70.0] | 65.0 [50.0–75.0] | <0.001 | All adjusted pairwise comparisons are significant (adj P < 0.001) |

| Experience of care | 70.0 [50.0–85.0] | 80.0 [65.0–90.0] | 65.0 [50.0–80.0] | 45.0 [30.0–65.0] | 55.0 [35.0–70.0] | <0.001 | All adjusted pairwise comparisons are significant (adj P < 0.001) |

| Availability of physical and human resources | 60.0 [40.0–80.0] | 70.0 [55.0–85.0] | 55.0 [40.0–70.0] | 40.0 [25.0–55.0] | 45.0 [30.0–65.0] | <0.001 | All adjusted pairwise comparisons are significant (adj P < 0.001) |

| Reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 | 75.0 [60.0–90.0] | 85.0 [75.0–95.0] | 70.0 [55.0–85.0] | 60.0 [50.0–75.0] | 60.0 [45.0–75.0] | <0.001 | All adjusted pairwise comparisons are significant (adj P < 0.001) except for Serbia vs Bosnia‐Herzegovina (P = 0.538) |

| Total QMNC Index | 285.0 [220.0–335.0] | 320.0 [280.0–350.0] | 270.0 [220.0–310.0] | 200.0 [155.0–255.0] | 220.0 [175.0–275.0] | <0.001 | All adjusted pairwise comparisons are significant (adj P < 0.001) for all comparisons except for Serbia vs Bosnia‐Herzegovina (P = 0.031) |

The QMNC index was calculated on the subsample of women providing an answer to all the questions on the 10 quality measures of the analyzed domain.

2.2. Data analyses

Data were cleaned according to a previously agreed protocol. A minimum sample size of 300 women for each country was calculated, based on preliminary data from other studies 26 on the hypothesis of an average QMNC index (our primary outcome and dependent variable) of 75% ± 7.5% (300 ± 30 points out of 400) and confidence level of 99.5%. This sample was adequate to detect a minimum expected frequency on each quality measure of 3% ± 3%, with a confidence level of 99.5%. Given the observational nature of the study, the upper limit of the sample was not predefined.

First, a descriptive analysis was performed, calculating absolute frequencies and percentages for sociodemographic variables and for each of the 40 key quality measures. Since quality measures differed between the two groups of women who did versus those who did not undergo labor, findings are presented separately. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to assess differences in the 40 key quality measures between the two groups (Supporting Information Table 6).

The QMNC index (Table 2; Supporting Information Table 7) was calculated based on the predefined criteria for all women providing answers for all 40 key quality measures. The QMNC indices are presented as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) as they are not normally distributed. Differences among countries were tested with a Kruskal‐Wallis test and pairwise comparisons were conducted with a Mann–Whitney test with a Bonferroni adjustment. To assess robustness of findings, a sensitivity analysis was conducted for each QMNC index domain including in the comparison all women not contributing to the QMNC index (women who did not answer all of the questions on the 10 quality measures were excluded from the QMNC index calculations) (Supporting Information Table 7).

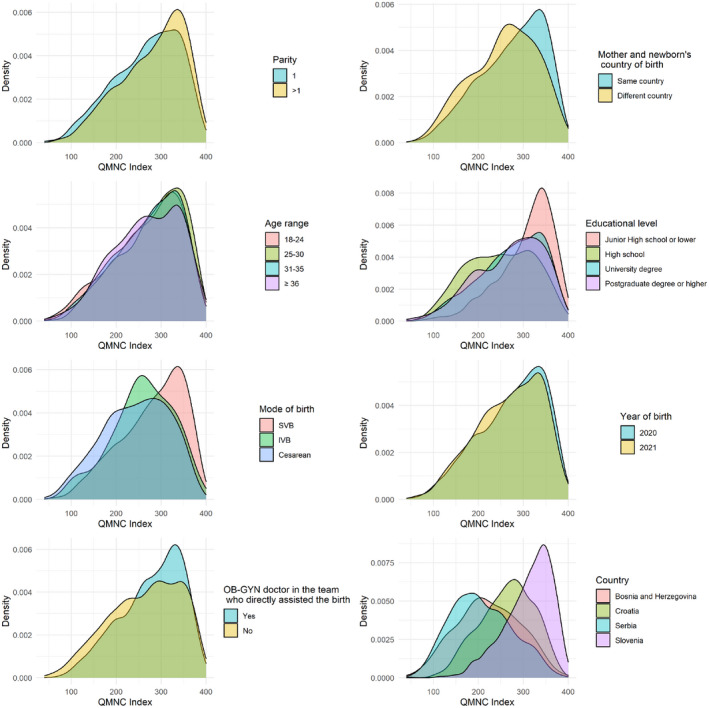

Multivariate analysis was also conducted. Given non‐normal distribution of the QMNC index and statistical evidence of heteroskedasticity (Breusch‐Pagan/Cook‐Weisberg test P < 0.05 for parity, facility type, age, education, birth mode, presence of an obstetrician/gynecologist who directly assisted birth, country), a multivariate quantile regression with robust standard errors was performed. The QMNC index was the dependent variable and the following were independent variables: sociodemographic variables (i.e. age, education, country, year of birth, and mother giving birth in the same country where she was born), parity, birth mode, and presence of an obstetrician/gynecologist who directly assisted birth (Supporting Information Tables 4, 5 and 8). Categories with the highest frequency were used as reference, except for countries where the reference was the country with the QMNC index closer to the average QMNC index for the whole sample (in this case Croatia) (Supporting Information Table 8). A graphical representation (kernel density) of QMNC index was plotted for each independent variable.

A two‐tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE version 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and R software (version 4.1.1).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of respondents

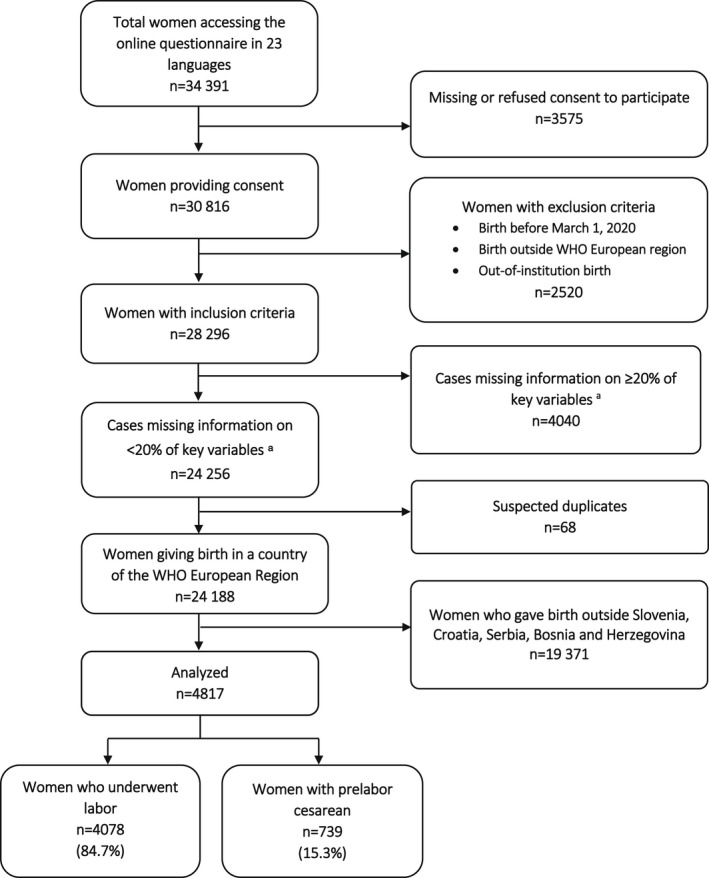

The characteristics of the survey respondents are described in Table 3. Out of 34 391 women accessing the online questionnaire of the IMAgiNE EURO study, 30 816 (89.6%) provided consent to participate. Of these, 4817 (15.9%) gave birth in one of the four countries included in the present paper (Figure 1, Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of respondents

| All four countries, No. (%) | Slovenia, No. (%) | Croatia, No. (%) | Serbia, No. (%) | Bosnia‐Herzegovina, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | |||||

| All participants (number) | 4817 | 2317 (48) | 1065 (22) | 940 (20) | 495 (10) |

| Year of birth | |||||

| 2020 | 3912 (81.2) | 2056 (88.7) | 770 (72.3) | 800 (85.1) | 286 (57.8) |

| 2021 | 708 (14.7) | 186 (8.0) | 258 (24.2) | 94 (10.0) | 170 (34.3) |

| Missing | 197 (4.1) | 75 (3.2) | 37 (3.5) | 46 (4.9) | 39 (7.9) |

| Participants giving birth in the same country where they were born | |||||

| Yes | 4355 (90.4) | 2154 (93.0) | 944 (88.6) | 833 (88.6) | 424 (85.7) |

| No | 311 (6.5) | 104 (4.5) | 94 (8.8) | 77 (8.2) | 36 (7.3) |

| Missing | 151 (3.1) | 59 (2.5) | 27 (2.5) | 30 (3.2) | 35 (7.1) |

| Age range, year | |||||

| 18–24 | 411 (8.5) | 204 (8.8) | 68 (6.4) | 58 (6.2) | 81 (16.4) |

| 25–30 | 1929 (40.0) | 1028 (44.4) | 396 (37.2) | 309 (32.9) | 196 (39.6) |

| 31–35 | 1652 (34.3) | 770 (33.2) | 404 (37.9) | 337 (35.9) | 141 (28.5) |

| 36–39 | 516 (10.7) | 203 (8.8) | 131 (12.3) | 145 (15.4) | 37 (7.5) |

| ≥40 | 158 (3.3) | 53 (2.3) | 39 (3.7) | 60 (6.4) | 6 (1.2) |

| Missing | 151 (3.1) | 59 (2.5) | 27 (2.5) | 31 (3.3) | 34 (6.9) |

| Educational level a | |||||

| Elementary school | 46 (1.0) | 30 (1.3) | 4 (0.4) | 7 (0.7) | 5 (1.0) |

| High school | 1522 (31.6) | 758 (32.7) | 315 (29.6) | 248 (26.4) | 201 (40.6) |

| University degree | 2131 (44.2) | 1055 (45.5) | 510 (47.9) | 391 (41.6) | 175 (35.4) |

| Postgraduate degree/Master/Doctorate or higher | 968 (20.1) | 415 (17.9) | 209 (19.6) | 264 (28.1) | 80 (16.2) |

| Missing | 150 (3.1) | 59 (2.5) | 27 (2.5) | 30 (3.2) | 34 (6.9) |

| Parity | |||||

| 1 | 2546 (52.9) | 1256 (54.2) | 595 (55.9) | 477 (50.7) | 218 (44.0) |

| >1 | 2119 (44.0) | 1002 (43.2) | 442 (41.5) | 433 (46.1) | 242 (48.9) |

| Missing | 152 (3.2) | 59 (2.5) | 28 (2.6) | 30 (3.2) | 35 (7.1) |

| Birth mode | |||||

| Vaginal spontaneous | 3528 (73.2) | 1777 (76.7) | 790 (74.2) | 618 (65.7) | 343 (69.3) |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 134 (2.8) | 81 (3.5) | 28 (2.6) | 20 (2.1) | 5 (1.0) |

| Cesarean | 1155 (24.0) | 459 (18.8) | 247 (23.2) | 302 (32.1) | 147 (29.7) |

| Type of hospital | |||||

| Public | 4609 (95.7) | 2248 (97.0) | 1032 (96.9) | 874 (93.0) | 455 (91.9) |

| Private | 55 (1.1) | 9 (0.4) | 6 (0.6) | 36 (3.8) | 4 (0.8) |

| Missing | 153 (3.2) | 60 (2.6) | 27 (2.5) | 30 (3.2) | 36 (7.3) |

| Type of healthcare providers assisting birth | |||||

| Midwife | 4035 (83.8) | 2128 (91.8) | 835 (78.4) | 725 (77.1) | 347 (70.1) |

| Nurse | 1961 (40.7) | 893 (38.5) | 470 (44.1) | 366 (38.9) | 232 (46.9) |

| Student (e.g. before graduation) | 496 (10.3) | 373 (16.1) | 39 (3.7) | 68 (7.2) | 16 (3.2) |

| Obstetrics registrar/medical resident (under postgraduation training) | 1062 (22.0) | 434 (18.7) | 295 (27.7) | 225 (23.9) | 108 (21.8) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology doctor | 3281 (68.1) | 1565 (67.5) | 718 (67.4) | 689 (73.3) | 309 (62.4) |

| Not specified | 784 (16.3) | 223 (9.6) | 243 (22.8) | 255 (27.1) | 63 (12.7) |

| Other | 188 (3.9) | 81 (3.5) | 12 (1.1) | 83 (8.8) | 12 (2.4) |

Wording on education levels agreed among partners during the Delphi. Questionnaire translated and back translated according to ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation Principles of Good Practice.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram. aForty quality measures and five key sociodemographic variables were considered as key variables.

TABLE 4.

Participants per country

| Slovenia | Croatia | Bosnia‐Herzegovina | Serbia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live births, 2019 | 18 794 | 35 985 | 28 360 | 61 692 |

| Expected births for reference period (16 months), based on 2019 data | 23 493 | 44 981 | 35 450 | 77 115 |

| Total number of participants | 2317 | 1065 | 495 | 940 |

| Percentage of participants per number of births in each country for reference period | 10% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

3.2. Provision of care

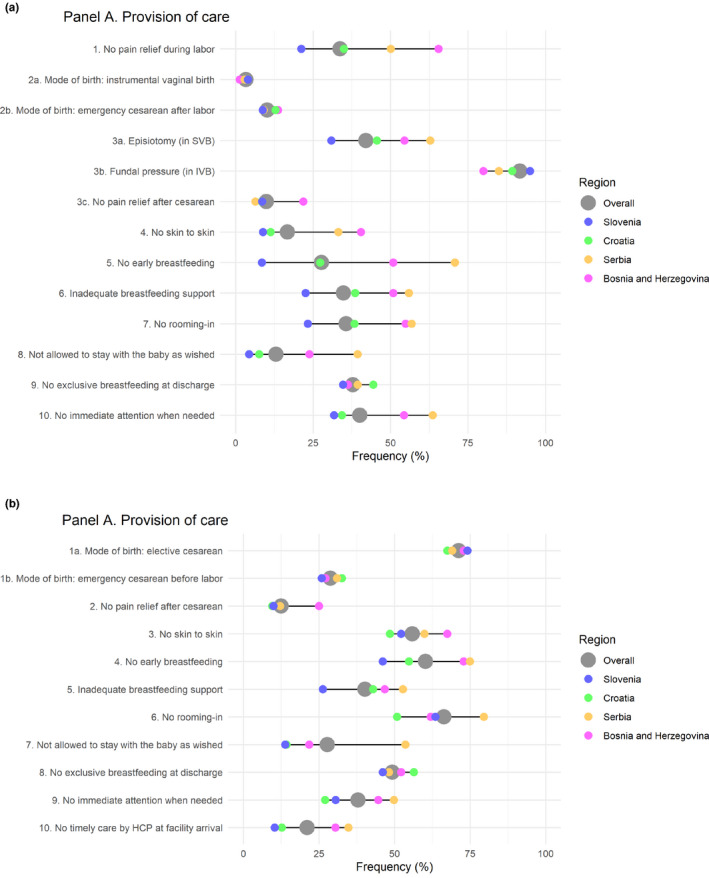

As shown in Figure 2a,b (detailed findings available in Supporting Information Tables 4–6), the majority of indicators showed substantial differences across the four countries, with the frequency for QMNC in Bosnia‐Herzegovina and Serbia worse for most indicators (i.e. more negative) compared with the other two countries. For example, lack of pain relief in labor during spontaneous vaginal birth had a frequency ranging from 21.2% in Slovenia to 65.5% in Bosnia‐Herzegovina. Lack of pain relief after cesarean ranged from 8.5% in Croatia to 21.8% in Bosnia‐Herzegovina. Episiotomy rates in spontaneous vaginal births ranged from 30.9% in Slovenia to 62.8% in Serbia.

FIGURE 2.

(a) Women who underwent spontaneous labor (b) Women with prelabor cesarean

Results were similar for indicators for newborn care, again with substantial differences across the four countries, and with Bosnia‐Herzegovina and Serbia showing larger gaps (Figure 2a,b). For the overall sample, for example, women reported lack of skin‐to‐skin contact soon after birth in 14.1% of cases in Slovenia compared with 45.5% in Bosnia‐Herzegovina; lack of early breastfeeding ranged from 13.0% in Slovenia to 71.8% in Serbia; lack of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge ranged from 36.0% in Slovenia to 45.8% in Croatia. Rate of skin‐to‐skin contact after birth, early breastfeeding, and exclusive breastfeeding were all lower for women who had a prelabor cesarean.

3.3. Experience of care

As shown in Figure 3a,b (Supporting Information Tables 4 and 5), trends in measures of experience of care were similar to those of provision of care, with substantial differences across the four countries and higher gaps for Bosnia‐Herzegovina and Serbia. Key results included the majority of survey participants reported inability to move freely during labor (range: 51.7% Slovenia and 52.1% Bosnia‐Herzegovina to 68.0% in Serbia) or to choose their birth position (range: 61.4% Slovenia to 89.5% Bosnia‐Herzegovina); lack of clear or effective communication with healthcare providers (range: 31.1% Slovenia to 58.8% Serbia); and not being involved in choices (range: 31.1% Slovenia to 78.3% Serbia).

FIGURE 3.

(a) Women who underwent spontaneous labor (b) Women with prelabor cesarean

Not being treated with dignity and respect was a commonly reported event (range: 21.5% Slovenia to 62.8% Serbia) as well as episodes of physical, verbal, or emotional abuse (range: 11.0% Slovenia to 30.5% Bosnia‐Herzegovina). There were major differences between the countries for women reporting lack of privacy (range: 17.7% Slovenia to 69.2% Serbia).

Women who experienced labor were mostly not allowed to have a companion (range: 60.3% Slovenia to 98.1% Serbia) and this frequency was significantly higher for women who had a planned cesarean (women who did not undergo labor; range 83.3% Slovenia to 98.3% Serbia). Among all countries, the frequency of women providing informal (cash) payments was higher among women who had a prelabor cesarean than in the group of women who experienced labor. The difference in frequencies for informal payments was most pronounced in Croatia (6.3% with prelabor cesarean, 1.2% of women who experienced labor) and Bosnia‐Herzegovina (27.2% with prelabor cesarean, 18.4% of women who experienced labor).

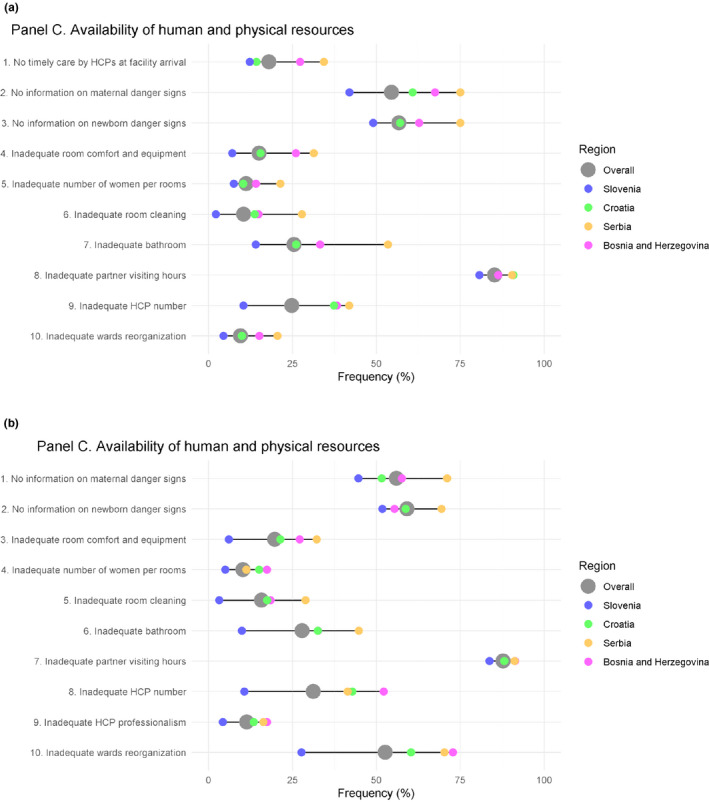

3.4. Availability of physical and human resources

Figure 4a,b (Supporting Information Tables 4 and 5) show that there were substantial differences in availability of physical and human resources across the four countries, with higher gaps in Bosnia‐Herzegovina and Serbia compared with the other two countries.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Women who underwent spontaneous labor (b) Women with prelabor cesarean

Most women reported inadequate partner visiting hours (range: 80.7% Slovenia to 90.8% Croatia and 90.4% Serbia). In addition, women reported overcrowding in maternity rooms (range: 7.5% Slovenia to 21.4% Serbia), lack of adequate information on maternal danger signs (range: 42.0% Slovenia to 75.0% Serbia), and lack of information on newborn danger signs (range: 49.1% Slovenia to 75.0% Serbia). Inadequate room cleaning and bathroom cleaning were relatively rare in Slovenia (2.2% and 14.1% respectively) but still frequent in Serbia (27.8% and 53.5%).

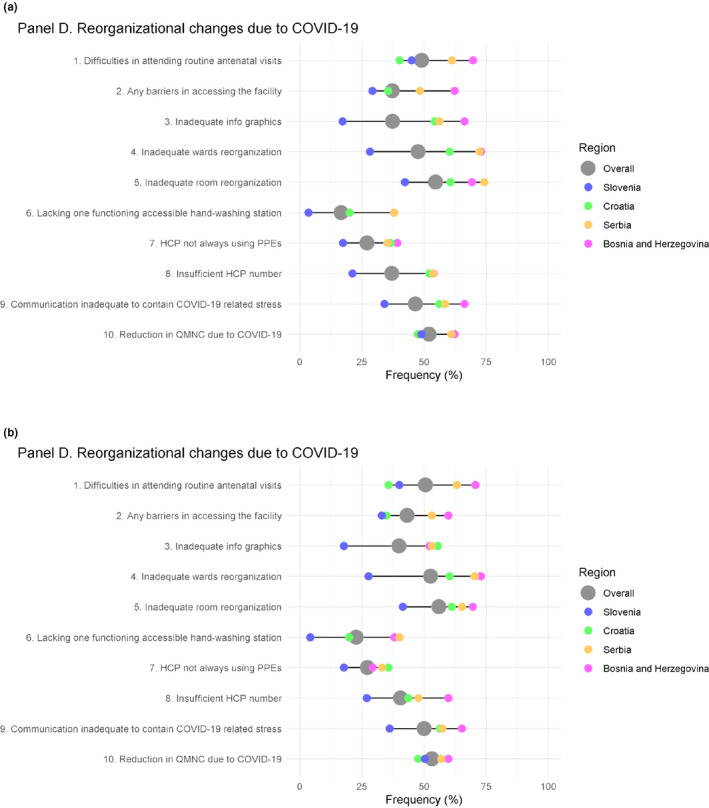

3.5. Organizational changes due to the COVID‐19 pandemic

Figure 5a,b (Supporting Information Tables 4 and 5) show that there were differences across the four countries for most indicators of organizational changes due to the pandemic, with higher gaps in Bosnia‐Herzegovina and Serbia compared with the other two countries.

FIGURE 5.

(a) Women who underwent spontaneous labor (b) Women with prelabor cesarean

Women reported difficulty in attending routine antenatal visits (range: 40.1% Croatia to 69.7% Bosnia‐Herzegovina), inadequate room reorganization (range: 42.3% Slovenia to 74.2% Serbia), and inadequate ward reorganization (range: 28.2% Slovenia to 73.0% Bosnia‐Herzegovina) at the time of birth. Reported adherence to pandemic hygiene measures tended to be relatively low in Serbia compared with the other countries, with lack of a functioning accessible handwashing station ranging from 3.5% in Slovenia to 38.1% in Serbia, and healthcare workers not always wearing protective equipment (ranging from 17.4% in Slovenia to 39.2% in Bosnia‐Herzegovina). A considerable number of women reported an inadequate number of healthcare workers (range: 21.2% Slovenia to 53.8% Bosnia‐Herzegovina) and felt that QMNC was reduced due to COVID‐19 (range: 47.4% Croatia to 62.3% Bosnia‐Herzegovina).

3.6. QMNC index and multivariate analysis

In each of the four countries, the domain with the lower QMNC index was availability of physical and human resources (range: 40.0 Serbia to 70.0 Slovenia); the domain with the higher QMNC index was provision of care (range: 55.0 Serbia to 85.0 Slovenia), with the exception of Serbia whose lowest index was in availability of physical and human resources (Table 2). Slovenia had significantly higher QMNC indices in all domains, when compared with other countries (P < 0.001). The sensitivity analyses did not change key findings (Supporting Information Table 7).

Results of multivariate quantile regression (Figure 6; Supporting Information Table 8) showed that women with junior high school or lower education, multiparous, aged 25–30 years, giving birth in 2021, and being assisted by an obstetrician/gynecologist reported significantly higher QMNC scores in one or more centiles, while women who had an instrumental vaginal birth or cesarean reported lower QMNC index scores in all analyzed centiles. Furthermore, women who gave birth in Slovenia had statistically significant higher coefficients compared with Croatian women, with increasing coefficients at lower centiles (coefficient variation at the 0.25th, 0.50th, and 0.75th centile: +57.5, +51.7, +40.0), while women giving birth in Serbia and in Bosnia‐Herzegovina had statistically significant lower QMNC index scores with decreasing values among women with lower QMNC index (−65.0, −63.3, −55.0 for women giving birth in Serbia and −55.0, −53.3, −36.7 for women giving birth in Bosnia‐Herzegovina).

FIGURE 6.

Quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) index

4. DISCUSSION

Few studies have been conducted on women's perceptions of maternal and newborn healthcare in countries of the former Yugoslavia. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 In Serbia, one study identified a number of interrelated themes, including women's feelings of isolation and abandonment, lack of communication, lack of a caring relationship, and lack of control and agency. 19 A hierarchical institutional culture with starkly disproportionate distribution of power between obstetricians, midwives, and women, paternalistic decision‐making, and use of nonevidence‐based practices has been documented in all four countries, although to a much lower extent in Slovenia. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Across and within countries, differences in practices of maternity care and implementation of evidence‐based care across health facilities have been described in previous studies. 21 , 22 , 23 , 35 However, to date, no study has described in a systematic manner the quality of maternal and newborn care across different countries of the former Yugoslavia, using standardized indicators and data collection tools.

The onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic strained many health systems already in challenging circumstances, lowering quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) globally. 36 , 37 , 38 Although many international and European institutions and organizations called for action supporting respectful, family‐centered care during the pandemic, 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 measures adopted in the field did not always reflect these recommendations.

The results of the survey suggest that there are major gaps in QMNC in the countries of the former Yugoslavia, with significant heterogeneity in most of the 40 indicators of QMNC and in the QMNC index. Multivariate analyses confirmed significant differences among countries, independently from population characteristics, with Slovenia showing the highest QMNC index, followed by Croatia, Bosnia‐Herzegovina, and Serbia. This is the first publication on a comprehensive assessment on the QMNC in these countries, based on a validated questionnaire including a set of 40 WHO standard‐based quality measures, capturing maternal perception of QMNC. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 The study provides a solid foundation on which to base future surveys to assess trends over time.

The findings of this study, with marked differences across countries, may be partly explained by differences in health system preparedness and response during the pandemic. For example, during the pandemic's waves, restriction of companionship—a practice not in accordance with WHO 41 —was adopted in varying degrees in all of the countries; however, these details may also reflect a pre‐existing difference in practice across the four countries. Companionship during cesarean is still not the norm in hospitals in any of the four countries, as reflected by our data showing that, overall, 91.5% (83.3%–98.3%) of women who had a prelabor cesarean were not allowed a companion.

Results of this study highlight gaps in all countries (but to a much lower extent in Slovenia), for all domains of QMNC, including provision (Croatia still showing a relatively high index), experience, availability of resources, and reorganization of care. Notably, episiotomy rates remain high in all four countries, indicating routine or liberal use, which is not in line with WHO recommendations, 43 but was also reported in other countries in the IMAgiNE EURO study. 44 , 45 , 46 Other indicators mirror unsatisfactory practices related to essential newborn care, with unsatisfactory rates of skin‐to‐skin contact and early breastfeeding, and insufficient breastfeeding support in all four countries. In 2017, a high number of maternity facilities in each of the countries were at some point designated as “baby friendly” as part of UNICEF's Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI). Currently, in Slovenia 86% of hospitals are BFHI designated (12 of 14 maternities), 47 in Croatia 95% of hospitals are designated (all public hospitals) 48 ; while 78% of hospitals in Bosnia‐Herzegovina and 85% in Serbia were “ever designated” as BFHI. 49 However, these results show that there is room for improvement, and many key elements of the BFHI are not well implemented in the countries, especially for women undergoing planned cesarean.

In the domain of experience of care, several quality measures, such as not asking for consent before vaginal examinations, and lack of privacy, emotional support, and dignity as well as abuses, indicated a need for improvements in respectful and evidence‐based care, including the implementation of quality improvement programs at healthcare facilities. Notably, the observed difference in informal payments between the elective cesarean group and women who experienced labor is in accordance with other studies, indicating that in central and eastern Europe, physicians often take informal payments to conduct planned cesarean. 50

Notably, the domain of availability of human and physical resources showed the lower reported QMNC index in each of the four countries. This is a crucial result, which is in line with previous reports 51 and calls for health system strengthening. Health policies should address this promptly by making targeted investments in the workforce and physical infrastructure of maternity facilities.

Overall, women with lower levels of education reported a higher QMNC index, which is in accordance with results from other authors, 34 , 52 likely because women with lower levels of education have lower expectations for their care. Some of the aspects of lower quality care reported, including those related to BFHI, were likely a result of pandemic containment measures, 44 but also a legacy of nonevidence‐based protocols and poor adherence to BFHI. These indicate the need for implementing quality improvement programs to raise the quality of care.

Limitations of the IMAgiNE EURO project have been commented on elsewhere 26 ; however, specific to this study, participants have higher levels of education compared with the general populations of the four countries 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 and they were more likely to be primiparous (Table 1). However, it is difficult to predict in which direction this may have affected results. 26 Data were collected over a period of time that included at least three COVID‐19 waves (depending on the country) but this specific study did not aim to look at trends over time; exploring how QMNC was associated with different phases of the pandemic and to the government responses will be the subject of future publications. Participants were disproportionately distributed among the four countries, and some countries had a small number of participants. Finally, the survey tool did not collect some important characteristics of mothers and newborns, such as gestational age, COVID‐19 status, and complications. This was predefined, in the light of retaining acceptability by mothers.

In conclusion, this study is the first of its kind among the four participating countries and provides a first comprehensive assessment on QMNC around the time of childbirth, from the woman's perspective. Findings of this study can be utilized to develop data‐driven quality improvement programs and policy reforms, and to identify priority gaps in QMNC that need to be tackled. The methodology allows further assessment over time; thus allowing assessment of progress over time and beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic, as well as focused assessments in specific subregions or settings. Quality of maternal and newborn care is a fundamental aspect of the health system and society and needs to be monitored and evaluated regularly.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ML conceived the study, with major inputs from EPV, BC, and IM. Surveys were translated by DD, MK, ZD, AB, AĆ, JR, and JR. EPV and BC supported the process of data collection, with inputs from ML. IM analyzed data, with major inputs from DD, ML, BC, and EPV. DD and ML wrote the first draft, with input from all authors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

5. IMAgiNE EURO study group

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Amira Ćerimagić, NGO Baby Steps, Sarajevo; Croatia: Daniela Drandić, Roda – Parents in Action, Zagreb; Magdalena Kurbanović, Faculty of Health Studies, University of Rijeka, Rijeka; France: Rozée Virginie, Elise de La Rochebrochard, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Research Unit, Institut National d’Études Démographiques (INED), Paris; Kristina Löfgren, Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative (IHAB); Germany: Céline Miani, Stephanie Batram‐Zantvoort, Lisa Wandschneider, Department of Epidemiology and International Public Health, School of Public Health, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld; Italy: Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Benedetta Covi, Ilaria Mariani, Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste; Sandra Morano, Medical School and Midwifery School, Genoa University, Genoa; Israel: Ilana Chertok, Ohio University, School of Nursing, Athens, Ohio, USA and Ruppin Academic Center, Department of Nursing, Emek Hefer; Rada Artzi‐Medvedik, Department of Nursing, The Recanati School for Community Health Professions, Faculty of Health Sciences at Ben‐Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev; Latvia: Elizabete Pumpure, Dace Rezeberga, Gita Jansone‐Šantare, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Riga Stradins University and Riga Maternity Hospital, Riga; Dārta Jakovicka, Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Rīga; Agnija Vaska, Riga Maternity Hospital, Riga; Anna Regīna Knoka, Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Rīga; Katrīna Paula Vilcāne, Faculty of Public Health and Social Welfare, Riga Stradins University, Riga; Lithuania: Alina Liepinaitienė, Andželika Kondrakova, Kaunas University of Applied Sciences, Kaunas; Marija Mizgaitienė, Simona Juciūtė, Kaunas Hospital of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas; Luxembourg: Maryse Arendt, Professional Association of Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg; Barbara Tasch, Professional Association of Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, KannerKlinik, Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg, Luxembourg; Norway: Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, Sigrun Kongslien, Department of Community Medicine, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø; Eline Skirnisdottir Vik, Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen; Poland: Barbara Baranowska, Urszula Tataj‐Puzyna, Maria Węgrzynowska, Department of Midwifery, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw; Portugal: Raquel Costa, EPIUnit ‐ Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto; Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional, Porto; Lusófona University/HEI‐Lab: Digital Human‐environment Interaction Labs, Lisbon; Catarina Barata, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa; Teresa Santos, Universidade Europeia, Lisboa and Plataforma CatólicaMed/Centro de Investigação Interdisciplinar em Saúde (CIIS) da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon; Carina Rodrigues, EPIUnit ‐ Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto and Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional, Porto; Heloísa Dias, Regional Health Administration of the Algarve; Romania: Marina Ruxandra Otelea, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest and SAMAS Association, Bucharest; Serbia: Jelena Radetić, Jovana Ružičić, Centar za mame, Belgrade; Slovenia: Zalka Drglin, Barbara Mihevc Ponikvar, Anja Bohinec, National Institute of Public Health, Ljubljana; Spain: Serena Brigidi, Department of Anthropology, Philosophy and Social Work, Medical Anthropology Research Center (MARC), Rovira i Virgili University (URV), Tarragona; Lara Martín Castañeda, Institut Català de la Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya; Sweden: Helen Elden, Verena Sengpiel, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg; Karolina Linden, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg; Mehreen Zaigham, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institution of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Lund and Skåne University Hospital, Malmö; Switzerland: Claire de Labrusse, Alessia Abderhalden, Anouck Pfund, Harriet Thorn, School of Health Sciences (HESAV), HES‐SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Lausanne; Susanne Grylka‐Baeschlin, Michael Gemperle, Antonia N. Mueller, Research Institute of Midwifery, School of Health Sciences, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur.

6. Ethical aspects

The multicountry study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the IRCCS Burlo Garofolo Trieste, Italy (IRB‐BURLO 05/2020 15.07.2020) and was conducted according to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, EU 2016/679). This was an online anonymous survey that women could decide to join on a voluntary basis. No data elements that could disclose maternal identity were collected, answers were recorded directly into a centralized platform hosted in Italy, and no data were treated in any of the four countries, therefore no further ethical approval was required for any of the countries considered in this paper. Prior to participation, women were informed of the study's objectives and methods, including their right to decline participation, and provided consent before participating. Data transmission and storage were secured by encryption, hosted at the Burlo Garofolo Institute.

DISCLAIMER

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Supporting information

Data S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Ministry of Health, Rome ‐ Italy, in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste, Italy. We would like to thank all of the women who took their time to respond to this survey despite family and childcare responsibilities and the stress of the COVID‐19 pandemic and earthquakes in the region. Special thanks to the IMAgiNE EURO study group for their contribution to the development of this project and support for this manuscript.

Drandić D, Drglin Z, Mihevc B, et al. Women's perspectives on the quality of hospital maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Results from the IMAgiNE EURO study in Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, and Bosnia‐Herzegovina . Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl. 1):54‐69. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14457

Contributor Information

Daniela Drandić, Email: daniela@roda.hr.

the IMAgiNE EURO study group:

Amira Ćerimagić, Daniela Drandić, Magdalena Kurbanović, Rozée Virginie, Elise de La Rochebrochard, Kristina Löfgren, Céline Miani, Stephanie Batram‐Zantvoort, Lisa Wandschneider, Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Benedetta Covi, Ilaria Mariani, Sandra Morano, Ilana Chertok, Emek Hefer, Rada Artzi‐Medvedik, Elizabete Pumpure, Dace Rezeberga, Gita Jansone‐Šantare, Dārta Jakovicka, Anna Regīna Knoka, Katrīna Paula Vilcāne, Alina Liepinaitienė, Andželika Kondrakova, Marija Mizgaitienė, Simona Juciūtė, Maryse Arendt, Barbara Tasch, Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, Sigrun Kongslien, Eline Skirnisdottir Vik, Barbara Baranowska, Urszula Tataj‐Puzyna, Maria Węgrzynowska, Raquel Costa, Catarina Barata, Teresa Santos, Carina Rodrigues, Heloísa Dias, Marina Ruxandra Otelea, Jelena Radetić, Jovana Ružičić, Zalka Drglin, Barbara Mihevc Ponikvar, Anja Bohinec, Serena Brigidi, Lara Martín Castañeda, Helen Elden, Verena Sengpiel, Karolina Linden, Mehreen Zaigham, Claire De Labrusse, Alessia Abderhalden, Anouck Pfund, Harriet Thorn, Susanne Grylka, Michael Gemperle, and Antonia Mueller

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data can be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sarić M, Rodwin VG. The once and future health system in the former Yugoslavia: myths and realities. J Public Health Policy. 1993;14:220‐237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stepovic M, Rancic N, Vekic B, et al. Gross domestic product and health expenditure growth in Balkan and East European Countries—Three‐Decade Horizon. Front Public Health. 2020;8:492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jakovljevic MM, Arsenijevic J, Pavlova M, Verhaeghe N, Laaser U, Groot W. Within the triangle of healthcare legacies: comparing the performance of South‐Eastern European health systems. J Med Econ. 2017;20:483‐492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klančar D, Švab I. Primary care principles and community health centers in the countries of former Yugoslavia. Health Policy. 2014;118:166‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. HZJZ . Hrvatski zdravstveno‐statistički ljetopis za 2019. – tablični podaci [Croatian Health‐Statistical Yearbook for 2019 ‐ tabular data]. Hrvatski Zavod Za Javno Zdravstvo [Croatian Public Health Institute]. 2020. https://www.hzjz.hr/periodicne‐publikacije/hrvatski‐zdravstveno‐statisticki‐ljetopis‐za‐2019‐tablicni‐podaci/. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- 6. Eurostat [website]. Enlargement countries ‐ population statistics. Eurostat Online Publications. Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina; 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics‐explained/index.php?title=Enlargement_countries_‐_population_statistics#Birth_and_death_rates. Accessed August 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agencija za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine [Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina]. Demografija 2019, Tematski bilten [Demography 2019, thematic bulletin]. Sarajevo; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Institut za javno zdravstvo Srbije dr. Milan Jovanović Batut [Institute of Public Health of Serbia "Dr. Milan Jovanović Batut]. Zdravstveno‐statistički godišnjak Republike Srbije 2019 [Health statistical yearbook of the Republic of Serbia 2019]. Beograd; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ministarstvo zdravstva Republike Hrvatske [Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia]. Plan i program mjera zdravstvene zaštite 2020.‐2022. [Plan and Program for Health Protection 2020–2022]. vol. NN 142/202. Zagreb; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Srpsko lekarsko društvo (Serbian Medical Society) . Zdravstvena zaštita žena u toku trudnoće ‐ nacionalni vodič za lekare u primarnoj zdravstvenoj zaštiti (Women's Healthcare During Pregnancy ‐ national guide for primary care physicians). Beograd: Ministarstvo zdravlja Republike Srbije (Ministry of Health of Serbia); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zavod za javno zdravstvo FBiH [Institute for Public Health FB&H Statistics Annual Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2019]. Zdravstveno statistički godišnjak Federacije Bosne i Hercegovine 2019 [Health Statistics Annual Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2019]. Sarajevo; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hrvatski zavod za javno zdravstvo [Croatian Institute for Public Health] . Hrvatski zdravstveno‐statistički ljetopis za 2020. – tablični podaci [Croatian Health‐Statistical Yearbook for 2020 ‐ tabular data]. HzjzHr; 2021. https://www.hzjz.hr/hrvatski‐zdravstveno‐statisticki‐ljetopis/hrvatski‐zdravstveno‐statisticki‐ljetopis‐za‐2020‐tablicni‐podaci/. Accessed July 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13. UNICEF [website] . Country Profiles: Serbia. Key Demographic Indicators. 2019. https://data.unicef.org/country/srb/. Accessed August 8, 2021.

- 14. World Bank [website] . Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate, per 100,000 live births) – Croatia. 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT?end=2017&locations=HR&start=2013. Accessed February 2, 2022.

- 15. UNICEF [website] . Country Profiles: Bosnia and Herzegovina. Key Demographic Indicators. 2019. https://data.unicef.org/country/bih/. Accessed August 8, 2021.

- 16. World Bank [website] . Maternal mortality ratio (national estimate, per 100,000 live births) ‐ Serbia. World Bank Data. 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT.NE?end=2017&locations=RS&start=1993&view=chart. Accessed February 2, 2022.

- 17. Nacionalni inštitut za javno zdravlje [National Institute for Public Health] . Zdravstveno stanje prebivalstva ‐ Porodi in rojstva [Population Health Status ‐ Births and Live Births]. NIJZ Podatkovni Portal [NIPH Data Portal]. 2020. https://podatki.nijz.si/Menu.aspx?px_tableid=PIS_TB_1.px&px_path=NIJZ%20podatkovni%20portal__1%20Zdravstveno%20stanje%20prebivalstva__03%20Porodi%20in%20rojstva&px_language=sl&px_db=NIJZ%20podatkovni%20portal&rxid=f41e850e‐421e‐4fa2‐9cb9‐29e0db0bea0e. Accessed July 7, 2021.

- 18. Rodin U, Cerovečki I, Jezdić D. Porodi u zdravstvenim ustanovama u Hrvatskoj 2020. godine [Childbirths in healthcare institutions in Croatia in 2020]. https://www.hzjz.hr/wp‐content/uploads/2021/07/PORODI_2020.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2022.

- 19. Stankovic B. Women's Experiences of Childbirth in Serbian Public Healthcare Institutions: a Qualitative Study. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24:803‐814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Drandić D, Knezić‐Frković B, Kurbanović M, Skukan‐Šoštarić Ž. Iskustva trudnica, rodilja i babinjača u zdravstvenom sustavu u Hrvatskoj u 2018. i 2019. godini [Women's Experiences in Maternity Care in Croatia in 2018 and 2019]. Zagreb. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vučemilović M, Mahmić‐Kaknjo M, Pavličević I. Transition from paternalism to shared decision making ‐ a review of the educational environment in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. Acta Med Acad. 2016;45:61‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mivšek AP, Petročnik P, Skubic M, Zakšek TŠ, Došler AJ. Umbilical cord management and stump care in normal childbirth in Slovenian and Croatian maternity hospitals. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56:773‐780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jug Došler A, Mivšek AP, Verdenik I, Škodič Zakšek T, Levec T, Petročnik P. Incidence of episiotomy in Slovenia: The story behind the numbers. Nurs Health Sci. 2017;19:351‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbrouckef JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:867‐872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lazić N, Lazić V, Kolarić B. First three months of COVID‐19 in Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia and Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina – comparative assessment of disease control measures. Infektološki Glasnik. 2020;40:43‐49. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. Quality of facility‐based maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: online survey investigating maternal perspectives in 12 countries of the WHO European Region. Lancet Reg Health Euro. 2022;13:100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, Giusti A, Pessa VE. Quality of care at childbirth: Findings of IMAgiNE EURO in Italy during the first year of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;157:405‐417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lazzerini M, Argentini G, Mariani I, et al. WHO standards‐based tool to measure women's views on the quality of care around the time of childbirth at facility level in the WHO European region: development and validation in Italy. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e048195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zaigham M, Linden K, Sengpiel V, et al. Large gaps in the quality of healthcare experienced by Swedish mothers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional study based on WHO standards. Women Birth. 2022;35:619‐627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization . Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Intrapartum care for women with existing medical conditions or obstetric complications and their babies. NICE Guideline; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lazzerini M, Mariani I, Semenzato C, Valente EP. Association between maternal satisfaction and other indicators of quality of care at childbirth: a cross‐sectional study based on the WHO standards. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e037063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lazzerini M, Semenzato C, Kaur J, Covi B, Argentini G. Women's suggestions on how to improve the quality of maternal and newborn hospital care: a qualitative study in Italy using the WHO standards as framework for the analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Afulani PA, Phillips B, Aborigo RA, Moyer CA. Person‐centred maternity care in low‐income and middle‐income countries: analysis of data from Kenya, Ghana, and India. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e96‐e109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Đelmiš J, Juras J, Rodin U. Perinatal mortality in Croatia in 2018. Gynaecol Perinatol. 2019;28:S1‐S17. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, et al. Effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e759‐e772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McDonnell S, McNamee E, Lindow SW, O'Connell MP. The impact of the Covid‐19 pandemic on maternity services: a review of maternal and neonatal outcomes before, during and after the pandemic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:172‐176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jardine J, Relph S, Magee L, et al. Maternity services in the UK during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a national survey of modifications to standard care. BJOG. 2021;128:880‐889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. International Confederation of Midwives . Women's rights in childbirth must be upheld during the Coronavirus pandemic. 29 March 2020. ICM; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Human Rights in Childbirth . Human rights violations in pregnancy, birth and postpartum during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Human Rights in Childbirth; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41. World Health Organization . Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID‐19 context. Vol 1. WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42. World Health Organization . COVID‐19 and breastfeeding position paper. WHO; 2020. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/437788/breastfeeding‐COVID‐19.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization . WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Transforming care of women and babies for improved health and well‐being. WHO; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272447/WHO‐RHR‐18.12‐eng.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pumpure E, Jakovicka D, Mariani I, et al. Women's perspectives on the quality of maternal and newborn care in childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Latvia: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study on 40 WHO standards‐based quality measures. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):97‐112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Costa R, Barata C, Dias H, et al. Regional differences in the quality of maternal and neonatal care during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Portugal: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):137‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Otelea MR, Simionescu AA, Mariani I, et al. Women's assessment of the quality of hospital‐based perinatal care by mode of birth in Romania during the COVID‐19 pandemic: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):126‐136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. National Institute for Public Health . Quality Indicators in Healthcare Annual Report 2016‐2017 (Kazalniki kakovosti v zdravstvu letno poročilo za leti 2016 in 2017). NIPH; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48. UNICEF Hrvatska . Baby‐Friendly Hospitals (Rodilišta prijatelji djece). UnicefOrg; 2017. https://www.unicef.org/croatia/rodilista‐prijatelji‐djece. Accessed February 2, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 49. World Health Organization . National Implementation of the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative 2017. WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Baji P, Rubashkin N, Szebik I, Stoll K, Vedam S. Informal cash payments for birth in Hungary: are women paying to secure a known provider, respect, or quality of care? Soc Sci Med. 2017;189:86‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. OECD iLibrary [website] . Health at a Glance: Europe 2020. OECD; 2020. https://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/social‐issues‐migration‐health/health‐at‐a‐glance‐europe‐2020_82129230‐en. Accessed February 2, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mehata S, Paudel YR, Dariang M, et al. Factors determining satisfaction among facility‐based maternity clients in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. United Nations Development Programme [website]. Human Development Indicators; 2020. https://www.hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/BIH. Accessed February 2, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 54. United Nations Development Programme [website]. Human Development Indicators; 2020. https://www.hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/HRV. Accessed February 2, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia . Statistical Pocketbook of the Republic of Serbia 2021. Vol 98; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 56. OECD . Education Policy Outlook: Slovenia. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia; 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.