Abstract

Administration of vaccines by the nasal route has recently proven to be one of the most efficient ways for inducing both mucosal and systemic antibody responses in experimental animals. Our results demonstrate that P40, a well-defined outer membrane protein A from Klebsiella pneumoniae, is indeed a carrier molecule suitable for nasal immunization. Using fragments from the respiratory syncytial virus subgroup A (RSV-A) G protein as antigen models, it has been shown that P40 is able to induce both systemic and mucosal immunity when fused or coupled to a protein or a peptide and administered intranasally (i.n.) to naive or K. pneumoniae-primed mice. Confocal analyses of nasal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue after i.n. instillation of P40 showed that this molecule is able to cross the nasal epithelium and target CD11c-positive cells likely to be murine dendritic cells or macrophages. More importantly, this targeting of antigen-presenting cells following i.n. immunization with a subunit of the RSV-A molecule in the absence of any mucosal adjuvant results in both upper and lower respiratory tract protection against RSV-A infection.

Many pathogens cause diseases by colonizing or penetrating mucosal tissues. Local production of immunoglobulin A (IgA) at the mucosal surface and induction of systemic IgG are essential for the primary defense against these pathogens (3). Successful protection against infectious diseases through vaccination implies high user compliance, which is best achieved by noninvasive mucosal administration of vaccines (38). To date, most of the vaccines licensed for human use are formulated for parenteral immunization and consequently induce a systemic immune response.

Several approaches have been investigated for their ability to provide efficient immunization by the mucosal route. Various killed or live attenuated recombinant microorganisms have been used as delivery systems essentially for the oral route (17, 30). As an alternative, many efforts have been made to immunize by the nasal route (18). In comparison to oral immunization, nasal administration of antigen seems to be more efficient, as smaller amounts of protein antigen and adjuvants are required (28). Recently, administration of vaccines by the nasal route has proven to be one of the most efficient ways of inducing both mucosal and systemic antibody responses in experimental animal models and human subjects (10, 14, 29, 32). In addition, nasal immunization can induce immune responses in other mucosal sites, such as the vagina (2, 20), a result which is of major interest for sexually transmitted diseases.

Intranasal (i.n.) immunization with a soluble protein antigen alone does not usually elicit substantial antibody or cellular immune responses. These failures can be overcome by coadministration of antigens formulated with liposomes (5), biodegradable polymer microspheres (7), microparticles (1), outer membrane proteins (4), or proteosomes (9, 20). In addition, adjuvants such as cholera toxin (CT), Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin (LT), or their B subunits (CTB and LTB, respectively) or, more recently, mutated forms of LT demonstrated efficacy in inducing mucosal and systemic responses when coupled to or mixed with several antigens (15, 35).

Recently, an outer membrane protein A (OmpA) derived from K. pneumoniae (24) called P40 has been identified and cloned. This OmpA displays carrier-related properties for peptides and polysaccharides (8, 27) when administered by the parenteral route. The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy and mechanism of action of this carrier molecule following nasal administration using, as antigen models, the pure B-cell epitope G5 and the G2Na protein, both derived from the respiratory syncytial virus subgroup A (RSV-A) G protein. These two antigens, known to be protective against RSV challenge when injected subcutaneously (s.c.) (26), were coupled and fused, respectively, to P40 for i.n. administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of P40-G5.

The protected peptide chain corresponding to the G5 sequence [144 to 159: (Cys)-Ser-Lys-Pro-Thr-Thr-Lys-Gln-Arg-Gln-Asn-Lys-Pro-Pro-Asn-Lys-Pro-(Cys)] was synthesized with an additional cysteine at the N or C terminus, allowing coupling to the P40 carrier protein (27). The chain was assembled by a solid-phase method with an Applied Biosystems 433A synthesizer and 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonly–tert-butyl chemistry. Side-chain-protecting groups were trityl for Asn, Gln, and Cys; tert-butyl for Ser and Thr; pentamethylchromansulfonyl for Arg; and tert-butyloxycarbonyl for Lys. The crude peptide, cleaved from the resin with trifluoric acid in the presence of scavengers, was lyophilized and purified by preparative reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The purity of the peptide was determined to be higher than 95% by reverse-phase HPLC and free-zone capillary electrophoresis. The mass (1,950.80 ± 0.31 Da) of the purified peptide, as measured by electrospray-mass spectrometry, was in close agreement with that calculated from the theoretical sequence (1,951.29 Da). P40 was prepared as previously described (8).

Peptide G5 was conjugated to P40 by its C-terminal cysteine residue using N-hydroxysuccinimidyl bromoacetate (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) as a coupling reagent as previously described (27). The peptide/protein molar ratio was determined by amino acid analysis using a Waters Pico-Tag HPLC system. Amino acids released from the conjugates by hydrolysis with 6 N HCl at 160°C for 2 h were analyzed as their phenylthiohydantoin derivatives. The degree of reaction was determined by quantifying the amount of S-carboxymethylcysteine calculated from the comparison of its integrated value with a known amount introduced into an amino acid standard solution. Typically, the G5/P40 ratio was between 5 and 8. The same method was applied for keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH)-G5 conjugation.

Production of P40G2Na.

P40G2Na was produced as previously described (26). The E. coli cell pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5)–1 mM EDTA–0.2 M NaCl–0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma, Saint Quentin Falavier, France). Cells were lysed by treating the suspension with lysozyme (0.5 g/liter) followed by 1 h of incubation at room temperature. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, the pellet was suspended in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5)–7 M guanidinium chloride–10 mM dithiothreitol, and inclusion bodies were solubilized by 2 h of incubation at 37°C. Thirteen volumes of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5)–150 mM NaCl–0.1% (wt/vol) Zwittergent 3-14 (Sigma) were added, and the solution was subsequently incubated overnight at room temperature under gentle stirring. The protein was further purified to homogeneity by two-step chromatography. Briefly, the renatured P40G2Na solution was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 20 mM ethanolamine-HCl (pH 10.5) buffer supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) Zwittergent 3-14 and then applied to a Pharmacia Source Q column equilibrated with the same buffer. Proteins were eluted using a 0 to 1 M NaCl gradient in 20 mM ethanolamine-HCl (pH 10.5) buffer containing 0.1% (wt/vol) Zwittergent 3-14. P40G2Na-containing fractions were pooled, dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–0.1% (wt/vol) Zwittergent 3-14, and applied to a Pharmacia Source S column equilibrated with the same buffer. Proteins were eluted using a 0 to 1 M NaCl gradient in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 0.1% (wt/vol) Zwittergent 3-14. P40G2Na-containing fractions were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration with a YM10 filter (Amicon cell). Purified P40G2Na was stored at −20°C. Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method using bovine serum albumin as a standard, and the protein was analyzed for purity by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with a 15% homogeneous gel.

Mouse strains and immunizations.

Six-week-old specific-pathogen-free female BALB/c mice were purchased from IFFA CREDO (l'Arbresle, France) and kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions. They were confirmed as seronegative for P40, G5, and RSV-A before being included in the studies. All animals were fed mouse maintenance diet A04 (UAR, Villemoissin-sur-Orge, France) and water ad libitum. They were housed and manipulated according to French and European guidelines. For immunizations, nonanesthetized BALB/c mice received 10 μg of G5 alone or coupled to P40, with or without the addition of 10 μg of CTB (Sigma) as a mucosal adjuvant. The immunization volume was less than or equal to 10 μl per nostril to avoid the spread of immunogen into the gastrointestinal tract or trachea. Serum samples were taken 9 days after immunization. For Klebsiella pneumoniae priming, 109 bacteria were administered i.n. to mice twice.

Animal sample preparation and ELISA.

Lung lavage fluids, nasal tract lavage fluids, and vaginal secretions were recovered as previously described (20, 27). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were performed essentially as described previously (26). Briefly, for anti-G5 antibody titration, Immulon 2 microtiter plates (Dynatech, Chantilly, Va.) were coated overnight at 4°C with KLH-G5 (1 μg of peptide/ml) in carbonate buffer (pH 9.8). Nonspecific reactions were blocked with 0.5% gelatin (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). The antibody samples were serially diluted and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were then extensively washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before incubation with 100 μl of peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Pierce) or goat anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) per well for 1 h at 37°C. After washing, a solution of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) was added to each well. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 10 min and was stopped by the addition of 1 M H2SO4. The A450 was determined using an IEMS reader (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). Titers were calculated as the reciprocal of the serum dilution which gave an A450 of >2 standard deviations above the value for a negative control serum. The results are expressed in log10 units, and for each group of mice, means are calculated as geometric means. Vertical bars represent standard deviations.

Lymphoproliferation assays.

For immunizations, nonanesthetized, 6-week-old female BALB/c mice (n = 10) received 20 μg of G5 coupled to P40 (up to 10 μl per nostril) or PBS as a control. Two weeks after immunization, spleens were removed, and a cell suspension was obtained by teasing spleens. Culturing was performed in triplicate with RPMI 1640 (Gibco) containing 50 U of penicillin/ml, 50 μg of streptomycin/ml, 0.25 M glutamine, and 10% fetal calf serum. The cells were stimulated in vitro by incubating 4 × 105 cells/well in 96 round-bottom plates (Costar) with various concentrations of recombinant P40. Background proliferation was measured with cells derived from PBS-immunized mice. At 54 h after plating, [methyl-3H]thymidine (1 μCi) (Amersham) was added to each well, and plates were incubated for an additional 18 h. Cultures were harvested onto a filter using a semiautomatic harvester (Skatron), and the amount of incorporated [3H]thymidine was determined using a 1900CA-Tricarb beta counter (Packard Instruments). The stimulation index was calculated as the experimental amount of radioactivity divided by the basal amount of radioactivity.

Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays.

BALB/c mice (n = 10) were immunized three times i.n. with P40-G5 or PBS. Three days after the last immunization, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (Imalgène 500; Mérial, Lyon, France) and xylazine (Rompun 2%; Bayer, Puteaux, France), exsanguinated by intracardiac puncture, and killed by cervical dislocation. Cervical lymph nodes (CLN), spleens, and nasal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) were removed and pooled. CLN and NALT were teased, and spleens were perfused with 10 ml of RPMI 1640 without phenol red (Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland) but supplemented with 2 mM glutamine (Life Technologies), 50 U of penicillin (Life Technologies)/ml, 50 μg of streptomycin (Life Technologies)/ml, and 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (BioWhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) (complete medium). Cells were washed and counted. Cell viability was checked by the trypan blue exclusion test, and single-cell suspensions were prepared at the appropriate concentrations before plating on previously coated plates (see below).

For ELISPOT assays, Maxisorb plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight at 4°C with antigen (KLH-G5: 0.1 μg of peptide/well in carbonate buffer [pH 9.8]) or with KLH (0.2 μg/well in carbonate buffer [pH 9.8]) and the serum albumin-binding region of streptococcal protein G (BB) (1 μg/well in carbonate buffer [pH 9.8]) as irrelevant antigens. After washing, nonspecific reactions were blocked with 0.5% gelatin (Serva), and 100 μl of cells from P40-G5-immunized mice or from PBS-treated naive mice was added in triplicate to the wells at concentrations of 2.5 × 106 to 0.3 × 106 cells/ml. Four dilutions from 2.5 × 105 to 0.3 × 105 cells/100 μl were analyzed for each spot number determination. In addition, the four dilutions were analyzed in triplicate. The number of spots analyzed was 8 to 44 spots/well. Cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in a humidified incubator and then removed by flicking the plates. The incubation time was too short for memory B cells to differentiate into immunoglobulin-secreting cells, allowing only in vivo-stimulated and actively secreting plasma cells to be identified (22). The plates were then washed three times with PBS–0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 20 and incubated overnight at 4°C with goat anti-mouse IgG (Pierce) or IgA (Southern Biotechnology Associates) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. After three washes in PBS–0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 20, the insoluble peroxidase substrate 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma)–H2O2 (100 μl/well) was added. H2O2 was prepared by adding 10 μl of a 30% H2O2 solution to 10 ml of acetate buffer. After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by adding water. Spots were enumerated under low magnification (×16), and data were adjusted to the number of immunoglobulin-secreting cells per 106 cells.

Confocal microscopy.

Heads were removed from sacrificed mice at various times after P40 or tetanus toxoid (TT) i.n. immunization, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified for 1 week at 4°C in PBS–0.4 M EDTA (Sigma), and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryostat-cut tissue sections were blocked with 10% murine serum in PBS and stained sequentially with rabbit anti-P40 or anti-TT polyclonal serum plus biotin–anti-CD3, biotin–anti-CD19, or biotin–anti-CD11c monoclonal antibody (MAb) (Pharmingen) diluted 1/200, followed by the addition of Alexa488-coupled goat anti-rabbit polyclonal serum (Molecular Probes) plus Cy5-streptavidin (Amersham), both diluted 1/500. Biotinylated isotype-matched antibodies (Pharmingen) were used as controls, and irrelevant anti-G2Na rabbit polyclonal serum was included as a negative control for P40 staining. Sections were analyzed on an LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using a ×16 C apochromate objective (Zeiss). Alexa 488 fluorescence was measured with a 530- to 30-nm band-pass filter after excitation with a 488-nm argon ion laser. Cy5 fluorescence was detected using a 660-nm LP filter after excitation with an HeNe laser tuned at 633 nm.

Virus preparation.

RSV subgroup A (RSV-A) (Long strain; ATCC VR-26; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) was propagated in HEp-2 cells (ECACC 86030501; European Collection of Animal Cell Cultures, Porton Down, Salisbury, United Kingdom) as previously described (26). The viral stock was prepared from the supernatant of a 48- to 72-h culture and stored at −196°C until use.

Protection studies.

Mice were challenged i.n. with 105 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of RSV-A and sacrificed 5 days later after anesthesia and total intracardiac puncture. Lung removal and processing, nasal tract lavage, and virus titrations were undertaken as previously described (26). The limits of detection of virus in lung tissues and nasal tracts were 1.45 log10 units/g of lung tissue and 0.45 log10 unit/ml of nasal wash fluid. When no virus was detected, actual detection limits were used for statistical analyses. Animal organs were considered protected when virus titers were reduced by at least 2 log10 units relative to titers for control mice.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using an analysis of variance with a P value of <0.05 and the Manugistics program (Statgraphic, Rockville, Md.).

RESULTS

Analysis of the antipeptide antibody response

To test whether i.n. administration of P40 coupled to G5 induces an antipeptide antibody response, BALB/c mice were administered P40-G5 (10 μg of G5, 10 μl per nostril) alone or in the presence of CTB as a mucosal adjuvant.

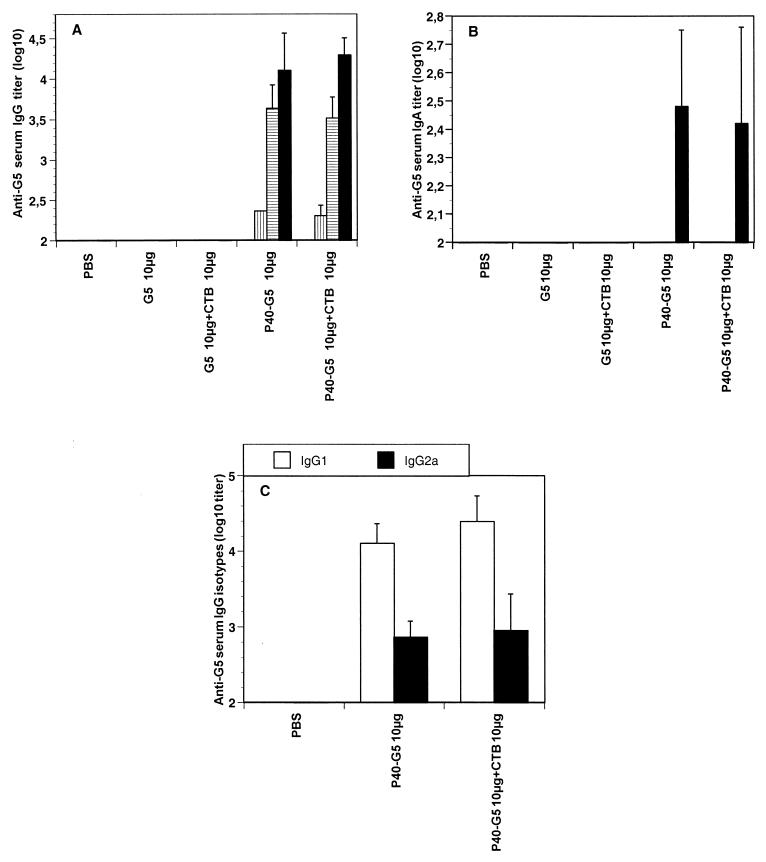

P40-G5 injected alone induced a slight primary systemic response against G5. After the first boost, significant anti-G5 serum IgG titers were observed and reached 4.2 log10 units after the third immunization (Fig. 1A). In contrast, no antibody response was detected when G5 was administered alone, even in the presence of 10 μg of CTB. Surprisingly, no further significant increase in the anti-G5 antibody response was observed when mice were immunized with P40-G5 in the presence of CTB. Three immunizations of mice by the s.c. route with P40-G5 plus Alhydrogel gave a slightly higher level of anti-G5 antibodies (5.3 log10 units) (L. Goetsch, unpublished data).

FIG. 1.

G5-specific immune response in serum of BALB/c mice (n = 5) immunized i.n. three times at 10-day intervals with peptide G5 (10 μg) coupled to P40, with or without CTB as a mucosal adjuvant. (A and B) All the mice were bled 9 days after each immunization, and G5-specific serum IgG (A) or IgA (B) was evaluated by ELISA. White bars, vertically hatched bars, horizontally hatched bars, and black bars represent anti-G5 titers at day 0 and after one, two, or three immunizations, respectively. (C) IgG subclasses determined by ELISA. For each group of mice, results are expressed as geometric means and standard deviations.

Specific IgA against G5 was also detected in sera after three immunizations with P40-G5. The addition of CTB had no further effect on the level of specific IgA elicited (Fig. 1B).

Analysis of the IgG subclasses in mice given P40-G5 revealed that both IgG1 and IgG2a were produced. The addition of CTB to P40-G5 was ineffective in modifying the IgG1/IgG2a ratio (Fig. 1C).

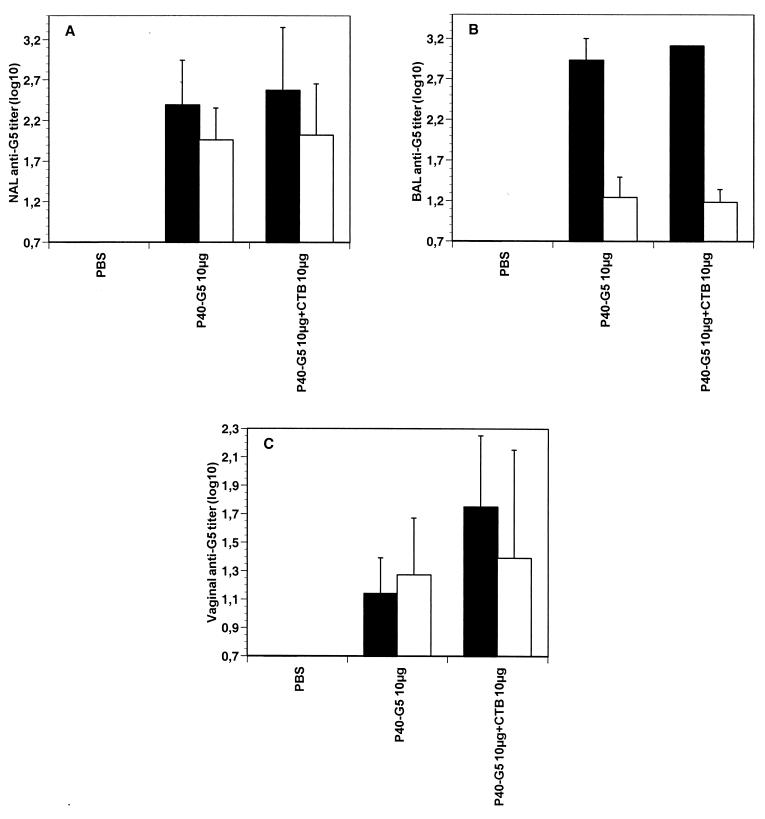

Since P40 coupled to G5 was administered locally, the presence of G5-specific IgA in the nasal tract and in mucosal secretions at a distal site was assessed. For this purpose, nasal, bronchoalveolar, and vaginal wash fluids were collected after i.n. immunization with P40-G5 and evaluated for their G5-specific IgA contents. Local anti-G5 IgA was detected in the nasal lavage fluid of the P40-G5-immunized mice (Fig. 2A, white bars). Anti-G5 IgG antibodies were also detected (Fig. 2A, black bars). Similarly, peptide-specific IgG antibodies were detected in the bronchoalveolar fluid of P40-G5-immunized mice (Fig. 2B, black bars). Only a small amount of G5-specific IgA was detected in the lung lavage fluid (Fig. 2B). Finally, anti-G5 IgA and IgG were also present in the vaginas of mice immunized with P40-G5 (Fig. 2C), indicating that the i.n. administration of P40-G5 induces G5-specific antibodies in mucosal surfaces at distal sites.

FIG. 2.

G5-specific mucosal immune response in nasal (A), bronchoalveolar (B), and vaginal (C) lavage fluids of BALB/c mice (n = 5) immunized i.n. three times at 10-day intervals with peptide G5 (10 μg) coupled to P40, with or without CTB as a mucosal adjuvant. Mice were sacrificed 10 days after the last immunization. Nasal, bronchoalveolar, and vaginal wash fluids were collected as described in Materials and Methods, and anti-G5 IgA (white bars) or IgG (black bars) was determined by ELISA. For each group of mice, results are expressed as geometric means and standard deviations.

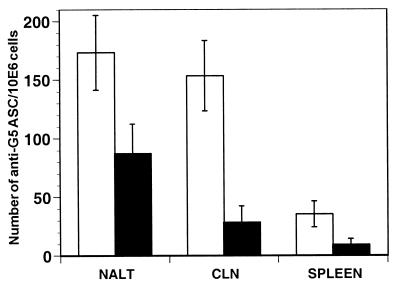

In order to discriminate between local induction and leakage of antibodies, the presence of antibody-secreting cells (ASC) was investigated 3 days after i.n. administration of P40-G5 to mice. Spleens, CLN, and NALT were examined for ASC as representative sites of systemic and mucosal antibody secretion. Small numbers of G5-specific IgG and IgA ASC were detected in the spleens; in contrast, however, CLN showed higher levels of G5-specific ASC in ELISPOT assays (Fig. 3A). The maximal IgG and IgA levels in ELISPOT assays were observed within the NALT. The IgG ASC level was higher than the IgA ASC level; these results are in agreement with those observed for tissue lavage fluids. Interestingly, ASC were already detected as early as 3 days postimmunization. As expected, nasal delivery of either G5 or P40 alone failed to elicit anti-G5 specific ASC (data not shown). No ASC were observed when NALT, CLN, or spleen cells from P40-G5-immunized mice were plated on irrelevant antigen-coated plates.

FIG. 3.

G5-specific ASC in NALT, CLN, and spleens of mice following i.n. immunization with P40-G5. BALB/c mice (n = 10) were immunized three times with P40-G5, and NALT, CLN, and spleens were removed 3 days after the last immunization. The number of specific IgG (white bars)- or IgA (black bars)-secreting cells was determined by ELISPOT assays as described in Materials and Methods. ASC, antigen-secreting cells; 10E6, 106.

In addition to the generation of ASC, T-cell memory was also induced after i.n. immunization with P40-G5, as shown by in vitro lymphocyte proliferation (Table 1). In comparison to PBS, P40 induced dose-dependent T-cell proliferation in vitro when added to cultures of splenocytes from mice immunized i.n. with P40-G5. Higher concentrations of P40 did not further increase T-cell proliferation. No proliferation was observed after splenocyte activation with G5, which is a B-cell epitope. These data demonstrate that P40 is an efficient carrier protein, able to induce mucosal and systemic antibody responses against a coupled peptide following i.n. administration in the absence of an adjuvant.

TABLE 1.

i.n. immunization with P40-G5 induces T-cell proliferation

| In vitro stimulant (μg/ml) | Stimulation index (cpm) after i.n. immunization with:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PBS | P40-G5 | |

| PBS | 1.0 (320) | 1.0 (258) |

| P40 (0.5) | 1.6 (512) | 17.4 (4,499) |

| P40 (1) | 1.5 (480) | 23.4 (6,044) |

| P40 (2) | 1.8 (576) | 33.0 (8,518) |

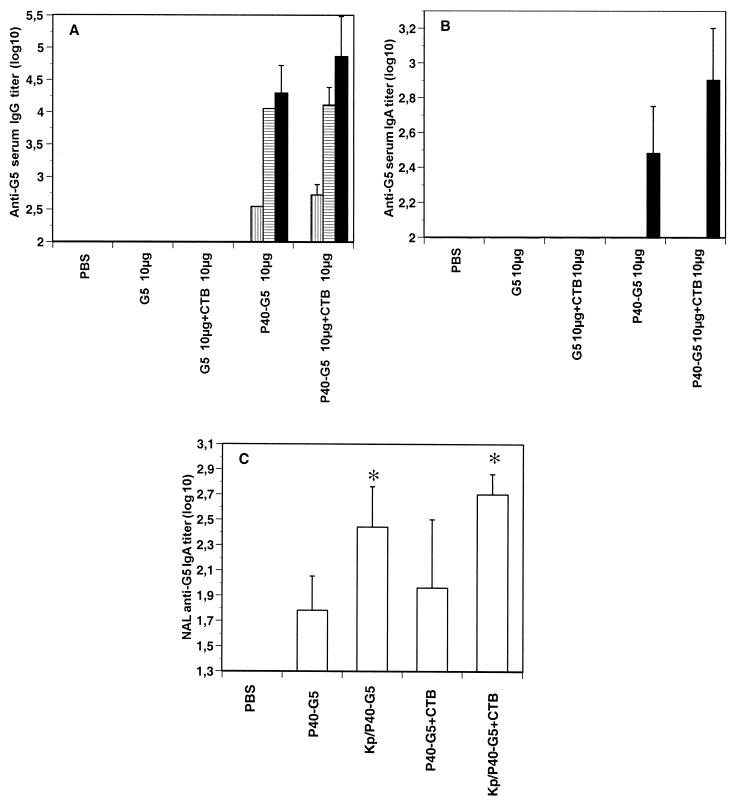

Analysis of the G5-specific immune response in mice primed with K. pneumoniae.

Since the presence of anticarrier antibodies may inhibit the induction of the antigen-specific response, as has been described for recombinant CTB used as a carrier protein (41), we investigated the effect of preexisting anti-P40 antibodies on the induction of the anti-G5 humoral response. For this purpose, BALB/c mice were sensitized twice i.n. with K. pneumoniae prior to immunization with P40-G5.

As expected, sensitization with K. pneumoniae induced anti-P40 antibody titers of up to 3.5 to 4 log10 units (Goetsch, unpublished). However, the induction of the serum G5-specific IgG response was not inhibited (Fig. 4A); it was even slightly increased compared to the results presented in Fig. 1A. In a similar way, the priming had no influence on the anti-G5 antibody response when mice were immunized with P40-G5 in the presence of CTB. Comparable results were observed for G5-specific IgA responses in sera (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, local G5-specific responses were increased in nasal fluids after sensitization with K. pneumoniae (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that preexisting anti-P40 antibodies have no suppressive effect on the antigenic response.

FIG. 4.

Anti-G5 systemic and mucosal immune responses in mice primed with K. pneumoniae (Kp) and immunized three times i.n. with P40-G5 3 weeks after priming. BALB/c mice (n = 5) were primed twice i.n. with K. pneumoniae (109 bacteria) and then immunized three times at 10-day intervals with P40-G5, with or without CTB as a mucosal adjuvant. (A and B) Mice were bled 9 days after each immunization, and serum anti-G5 IgG (A) or IgA (B) was determined by ELISA. White bars, vertically hatched bars, horizontally hatched bars, and black bars represent anti-G5 titers at day 0 and after one, two, or three immunizations, respectively. (C) At 10 days after the last immunization, mice were sacrificed and nasal fluids were collected for IgA titer determination. For each group of mice, results are expressed as geometric means and standard deviations. The asterisk indicates a P value of <0.05 for a statistical analysis of primed and nonprimed mice.

Trafficking of P40 in the NALT.

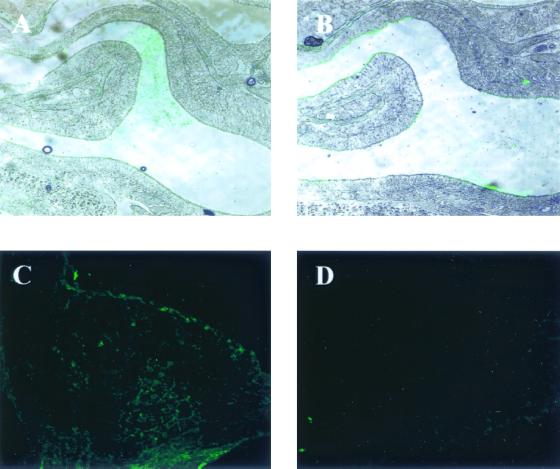

To further understand the mechanisms involved in the generation of local and systemic immune responses after the administration of P40 by the nasal route, P40 was administrated i.n. and monitored in the NALT with rabbit polyclonal serum against P40. Immediately after administration, P40 was located in the nasal cavity (Fig. 5A). At 3 h after administration, P40 was found on the epithelia of the nasal cavity (Fig. 5B), and at 12 h after administration, staining was detected within the NALT (Fig. 5C). The specificity of the staining was confirmed by a negative image obtained when sections were stained with an irrelevant, anti-G2Na polyclonal serum and the secondary anti-rabbit antibody (Fig. 5D) and by the fact that no P40 could be detected 72 h after immunization (Goetsch, unpublished). These results indicate that P40 is located within the NALT after in vivo i.n. administration.

FIG. 5.

Localization of P40 after i.n. immunization. (A to C) BALB/c mice (n = 3) were immunized i.n. with P40-G5 and sacrificed immediately (A) or 3 h (B) or 12 h (C) after immunization. After fixation and digestion of mouse heads with PBS-EDTA, cryostat-cut tissue sections were blocked and stained with anti-P40 rabbit polyclonal serum and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody. (D) Negative control stained with irrelevant anti-G2Na polyclonal serum and secondary antibody.

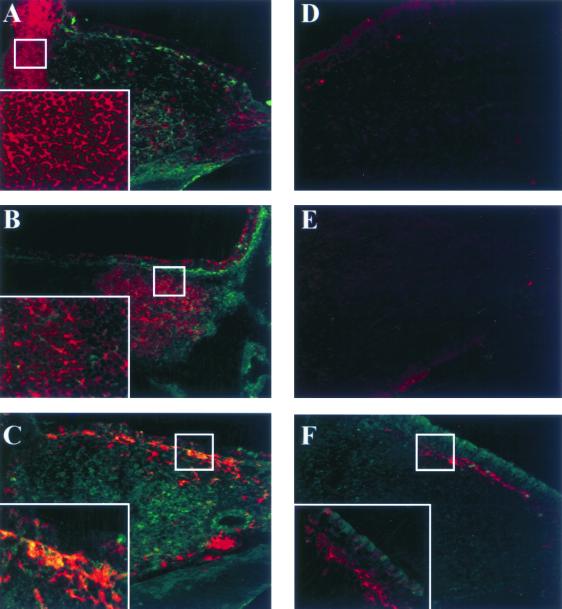

Colocalization experiments with antibodies specific for several cell types were subsequently performed. At 12 h after administration, P40 was located within the NALT (Fig. 6), in agreement with experiments described above (Fig. 5). Figures 6A and B show that no colocalization was observed with CD3- or CD19-positive cells. The major portion of CD11c-positive cells was located in the area surrounding the NALT (Fig. 6C). Significant colocalization of P40 and CD11c-positive cells is shown on Fig. 6C. No colocalization was observed when biotinylated hamster IgG was used as an isotype control for biotinylated CD3 and CD11c MAbs (Fig. 6D). The same result was obtained with biotinylated rat IgG2a, used as an isotype control for CD19 staining (Fig. 6E).

FIG. 6.

Colocalization of P40 with CD3-, CD19-, and CD11c-positive cells within the NALT. Heads of BALB/c mice were removed 12 h after P40-G5 i.n. immunization and treated as described in Material and Methods. (A to C) Cryostat-cut tissue sections were stained with anti-P40 polyclonal serum and biotinylated anti-CD3 MAb (A), anti-P40 polyclonal serum and biotinylated anti-CD19 MAb (B), and anti-P40 polyclonal serum and biotinylated anti-CD11c MAb (C). (D and E) Isotype control staining for, respectively, biotinylated anti-CD3 and anti-CD11c MAbs. (F) Colocalization of CD11c and TT administered as a control protein. Biotinylated antibodies were revealed using Cy5-streptavidin. Anti-P40 antibody was revealed using Alexa488-coupled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Enlargements of the small insets are shown in the lower left corners of panels A, B, C, and F.

To determine if the location in CD11c-positive cells is a unique feature of P40 or if it is a common pathway for nasally administered protein, the same experiment was performed with TT as a control protein. As shown in Fig. 6F, no colocalization of TT with CD11c-positive cells was observed 12 h after immunization. These results suggested that after i.n. administration, P40 targets selectively CD11c-positive cells within the NALT.

Protection after i.n. immunization with P40-G5 or P40G2Na in naive or K. pneumoniae-sensitized mice.

In order to test the biological relevance of the systemic and mucosal immune responses, an RSV-A model was used. Protective efficacy against an RSV-A infection was evaluated first in naive or K. pneumoniae-primed mice immunized with P40-G5. Protection of the lungs and the nasal tract was assessed 5 days after i.n. challenge with live RSV-A, corresponding to the peak of infection. In comparison to control mice, immunized with PBS, mice immunized i.n. with P40-G5 were protected against RSV-A infection, with more than a 2-log-unit reduction in their lung RSV-A titers (Table 2). Among these mice, two of them showed no evidence of virus in the lungs. These results are similar to those obtained after three s.c. immunizations with P40-G5 plus Alhydrogel, used as an adjuvant. The addition of CTB during i.n. immunization had no additional effect on the induced protection. As previously observed for the IgG antibody response, priming with bacteria had no significant effect on the lung RSV-A titers of mice immunized with P40-G5, which remained protected compared with control mice. These protection results correlate with the antibody responses, which are quite similar in naive and primed mice. In contrast to these data, protection of the nasal tract was not observed for naive mice after immunization with P40-G5, with or without CTB. However, partial protection of the nasal tract was observed for K. pneumoniae-primed mice, with a strong decrease in the virus load and two mice out of five showing no evidence of virus in the nasal tract. No protection of the upper respiratory tract was observed for mice immunized s.c. with P40-G5, either with or without K. pneumoniae priming.

TABLE 2.

i.n. immunization with P40-G5 protects naive or K. pneumoniae-primed mice from RSV-A infection

| Immunizing material | RSV-A titera in the following mice:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive

|

K. pneumoniae primed

|

|||

| Per g of lung | Per ml of nasal tract lavage fluid | Per g of lung | Per ml of nasal tract lavage fluid | |

| PBS i.n. | 4.16 ± 0.6 | 2.83 ± 0.47 | 4.05 ± 0.45 | 2.95 ± 0.68 |

| P40-G5 i.n. | 2 ± 0.54b (2/5) | 2.45 ± 0.61 | 1.9 ± 1.01b (4/5) | 1.4 ± 0.78b (2/5) |

| P40-G5 + CTB i.n. | 2.35 ± 1.02b (1/5) | 2.25 ± 0.48 | 2.15 ± 1.43c (3/5) | 2.25 ± 0.72 (1/5) |

| PBS s.c. | 5.05 ± 0.12 | 2.9 ± 0.43 | 4.70 ± 0.27 | 2.70 ± 0.42 |

| P40-G5 s.c. | 1.55 ± 0.12b (4/5) | 2.65 ± 0.53 | 1.55 ± 0.12 (3/5) | 2.85 ± 0.34 |

Log10 TCID50, reported as means and standard deviations (number of sterilized mice/number of mice tested).

The P value for a comparison with the control was <0.001.

The P value for a comparison with the control was <0.01.

These results demonstrated that i.n. administration of P40-G5 protects the lower respiratory tract against RSV-A infection and reduces significantly upper respiratory tract infection in mice previously primed with K. pneumoniae and seropositive for P40.

We also tested the protective efficacy of P40 fused with G2Na, a polypeptide which is derived from the RSV-A G protein and which comprises several B-cell epitopes involved in protection (26). In agreement with the results previously obtained with P40-G5, mice immunized with P40G2Na were protected against RSV-A infection of the lower respiratory tract, with most of the mice showing no detectable virus in the lungs (Table 3). Interestingly, these mice also showed a significant reduction in nasal RSV-A titers. Like the results obtained with P40-G5, the protective efficacy of P40G2Na was further increased in the nasal tract when mice were previously primed with K. pneumoniae.

TABLE 3.

i.n. immunization with P40G2Na protects naive or K. pneumoniae-primed mice from RSV-A infection

| Immunizing material | RSV-A titera in the following mice:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive

|

K. pneumoniae primed

|

|||

| Per g of lung | Per ml of nasal tract lavage fluid | Per g of lung | Per ml of nasal tract lavage fluid | |

| PBS i.n. | 4.55 ± 0.13 | 3.4 ± 0.48 | 4.11 ± 0.26 | 3.16 ± 0.19 |

| P40 i.n. | 4.2 ± 0.41b | 2.95 ± 0.48b | 4.4 ± 0.49b | 2.99 ± 0.43b |

| P40G2Na i.n. | 1.49 ± 0.1c | 2.28 ± 0.7d | 1.49 ± 0.1c | 0.99 ± 0.75c |

Log10 TCID50, reported as means and standard deviations.

Not significantly different from control value.

The P value for a comparison with the control was <0.001.

The P value for a comparison with the control was <0.01.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that targeting of the NALT with P40 coupled to a peptide or fused to a protein induces protection of the upper and lower respiratory tracts against RSV-A infection.

DISCUSSION

Mucosal immunization offers several advantages over parenteral immunization, including greater efficacy in achieving both mucosal and systemic antibody responses, minimal adverse reactions, and a reduction in cross-contamination with needles (38). Various strategies have been proposed to allow nonmucosal antigens to be used for mucosal immunization. These strategies include the use of mucosal adjuvants, expression of recombinant antigens from attenuated mucosal pathogens, and linkage of epitopes or proteins to mucosal immunogens. Such measures overcome the selective nature of the common mucosal immune system, which helps limit responsiveness to environmental immunogens. However, to date, most vaccines are administered intramuscularly.

In this study, the efficacy for i.n. immunization of a new carrier protein, P40, derived from K. pneumoniae (27), was demonstrated. G5, a hapten comprising a unique B-cell epitope, was immunogenic neither alone nor in the presence of CTB, which has been reported to potentiate mucosal immune responses to noncoupled antigens (35). T-helper sequences included in carrier molecules have been shown to be necessary for inducing an antibody response against a pure B-cell epitope (11). Immunization with P40 coupled to G5 was able to generate anti-G5 systemic and mucosal IgG and IgA responses. Despite the contamination of the CTB used (provided from Sigma) and the fact that this CTB has been used as an adjuvant in various studies (11, 20), no booster effect on the antibody response induced by P40-G5 immunization was observed. This observation suggests that the optimal response was obtained with the peptide coupled to P40 without the need for any mucosal adjuvant. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that a booster effect would be observed with CT as an adjuvant.

Interestingly, local IgA was detected in nasal wash fluids but also at distal sites, such as the lungs or vagina. These results are in agreement with previous experiments which demonstrated that either oral or nasal immunization could induce antibody responses in the vagina and rectum (20, 25, 28, 29, 37). Because P40 was purified in low-endotoxin conditions (an endotoxin level of less than 1 UI/mg of protein), we excluded the possible adjuvant effect of residual contaminating endotoxin. Moreover, when P40 mixed with the peptide was administered i.n., no response was observed (Goetsch, unpublished).

As P40 is isolated from K. pneumoniae, a ubiquitous pathogenic bacterium of the human upper respiratory tract, anti-P40 antibodies are commonly detected in human sera at titers reaching 3.7 ± 0.4 log10 units in persons from 1 to 15 years of age (Goetsch, unpublished). Inhibitory effects of preexisting anticarrier antibodies have been reported for humans (6) and mice with several type of carriers, such as TT for the systemic route of administration (31, 33) or CTB for nasal immunization (41). It was therefore important to demonstrate that anti-P40 antibodies had no effect on the induction of an antipeptide antibody response. Priming with K. pneumoniae raises a strong anti-P40 antibody response. In addition, since many people have already been infected with K. pneumoniae by the nasal route and have anti-P40 antibodies, we thought that it would be relevant to mimic natural priming with K. pneumoniae in mice. Our results show that sensitization of mice with K. pneumoniae prior to i.n. immunization with P40-G5 has no inhibitory effect on the levels of local and systemic antipeptide antibody responses. Furthermore, an increase in the levels of antibody responses was observed. This phenomenon has been previously reported using TT coupled to a malarial peptide (19) or to hCG (34). These results indicate that preexisting anti-P40 antibodies do not impair the development of specific immune responses and may even favor it; this idea has important implications for the use of P40 as an alternative carrier protein in seropositive humans. These results confirm previous experimental data showing that no epitopic supression was observed in mice primed with P40 and immunized with P40-peptide (27). The absence of epitopic supression was also observed with polysaccharide antigens.

The isolation of IgA or IgG ASC from the NALT after nasal immunization with P40-G5 indicates that the mucosal responses previously observed did not result in antibody leakage from systemic to mucosal compartments. Furthermore, the presence of ASC in draining CLN and the spleen shows that stimulation also occurs through these tissues. Taken together, these results suggest that P40 is able to cross the epithelium covering the nasal cavity, allowing antigen to reach and prime an immune response in the NALT. After immunogens have been captured and processed by antigen-presenting cells within the mucosal tissue, they can migrate to regional lymph nodes and the spleen to generate a systemic immune response (21).

These findings are in agreement with the histological appearance and immunohistochemical analysis of NALT, which show that P40 is able to pass through the nasal cavity into the lymphoid tissue, where the carrier protein is closely associated with antigen-presenting cells. These data correlate with those obtained by Jeannin et al. (16), who showed, in vitro, by flow cytometry and confocal analysis that P40 binds to and is internalized by macropinocytosis into dendritic cells and macrophages without any binding to B and T lymphocytes. In addition, the data could explain the early detection of ASC, which appeared 3 days after the last nasal immunization.

Ongoing experiments will elucidate the mechanisms of penetration of P40 within the NALT. The demonstration of the presence of epithelial M cells in the human nasopharyngeal areas forms the basis for an efficient i.n. vaccine (23). Experiments are in progress to investigate the binding of P40 to such cells. For CT and LT, it has been reported that binding to GM1 (36), expressed by a variety of cell types, occurs. This binding would increase the amount of antigen crossing the mucosal epithelium and therefore its subsequent presentation to the immune system (21). In contrast, the mechanism of action of meningococcal outer membrane vesicles, also being tested in humans, is not clearly defined.

The biological relevance of nasal immunization with P40 as a carrier protein was addressed by studying the protective efficacy of the G5 B-cell epitope coupled to P40 or the fusion protein P40-G2Na. Previous experiments demonstrated that P40 conjugated to G5 targeted monocyte-derived dendritic cells and was internalized, indicating that the coupling of a peptide to P40 did not impair the binding of the protein to antigen-presenting cells (16). G5 and G2Na are known to protect mice from RSV-A infection when conjugated or fused to carrier molecules and administered by the systemic route (26). i.n. immunizations with the two molecules induced remarkable protection of the lower respiratory tract against RSV-A infection. In agreement with the immunological results, preexisting anti-P40 antibodies did not have a negative effect on the protection observed. Furthermore, partial protection of the upper respiratory tract was observed after i.n. immunization with P40-G2Na. For both molecules, protection was further enhanced when mice were presensitized with K. pneumoniae. Several explanations could account for the beneficial effect of the K. pneumoniae priming. One could speculate that anti-P40 antibodies facilitate the uptake of the antigen, as already suggested (13). Alternatively, the T-cell response specific for P40 could help in the setting of the specific antibody response, as previously mentioned (12).

i.n. immunizations with the F protein derived from RSV and mixed with CT (39) or CTB (25, 40) have been reported to induce protection of the upper and lower respiratory tracts. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that i.n. immunization with a conjugate composed of P40 coupled to a single B-cell epitope or fused to a small protein derived from the G protein of RSV is able to induce protection of both lower and upper respiratory tracts without the use of any adjuvant.

CTB is the carrier molecule most frequently used for nasal immunization (36). In this study, we show that P40 is able to pass through the nasal cavity into lymphoid tissues. Interestingly, P40 targets in vivo antigen-presenting cells localized within the NALT. The main question which remains to be solved is the specificity of P40 penetration. The efficacy of P40 in targeting antigen-presenting cells in the NALT and in generating a protective immune response when coupled or fused to RSV-derived antigens offers a new opportunity for the use of this molecule as a carrier protein for nasal immunization in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Van Dorsselaer and N. Zorn for performing mass spectrometry and T. Champion, John Challier, F. Derouet, and L. Zanna for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baras B, Benoit M-A, Dupré L, Poulain-Godefroy O, Shacht A-M, Capron A, Gillard J, Riveau G. Single-dose mucosal immunization with biodegradable microparticles containing a Schistosoma mansoni antigen. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2643–2648. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2643-2648.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergquist C, Johansson E-L, Lagergard T, Holmgren J, Rudin A. Intranasal vaccination of humans with recombinant cholera toxin B subunit induces systemic and local antibody responses in the upper respiratory tract and the vagina. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2676–2684. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2676-2684.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvet J P, Fischetti V A. Diversity of antibody-mediated immunity at the mucosal barrier. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2687–2691. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2687-2691.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalseg R, Wedege E, Holst J, Haugen I L, Hoiby E A, Hanaberg B. Outer membrane vesicles from group B meningococci are strongly immunogenic when given intranasally to mice. Vaccine. 1999;17:2336–2345. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Haan A, Tomee J F C, Huchshorn J P, Wilshut J. Liposomes as an immunoadjuvant system for stimulation of mucosal and systemic antibody responses against inactived measles virus administered intranasally to mice. Vaccine. 1995;13:1320–1324. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di John D, Wasserman S S, Torres J R, Cortesia M J, Murillo J, Losonsky G A, Herrington D A, Sturcher D, Levine M M. Effect of priming with carrier on response to conjugate vaccine. Lancet. 1989;8677:1415–1418. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta R K, Chang A C, Siber G R. Biodegradable polymer microspheres as vaccine adjuvants and delivery systems. Dev Biol Stand. 1998;92:63–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haeuw J F, Rauly I, Zanna L, Libon C, Andréoni C, Nguyen T, Baussant T, Bonnefoy J Y, Beck A. The recombinant Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane protein OmpA has carrier properties for conjugated antigenic peptides. Eur J Chem. 1998;255:446–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haneberg B, Dalseg R, Oftung F, Wedege E, Hoiby E A, Haugen I L, Holst J, Andersen S R, Aase A, Meyer Naess L, Michaelsen T E, Namork E, Haaheim L R. Towards a nasal vaccine against meningococcal disease, and propects for its use as a mucosal adjuvant. Dev Biol Stand. 1998;92:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haneberg B, Dalseg R, Wedege E, Hoiby E A, Haugen I L, Oftung F, Rune Andersen S, Meyer Naess L, Aase A, Mickaelsen T E, Holst J. Intranasal administration of a meningococcal outer membrane vesicle vaccine induces persistent local mucosal antibodies and serum antibodies with strong bactericidal activity in humans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1334–1341. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1334-1341.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hathaway L J, Obeid O E, Steward M W. Protection against measles virus-induced encephalitis by antibodies from mice immunized intranasally with a synthetic peptide immunogen. Vaccine. 1998;16:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)88326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzenberg L A, Tokuhisa T. Carrier-priming leads to hapten-specific suppression. Nature. 1980;285:664–667. doi: 10.1038/285664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herzenberg L A, Tokuhisa T. Epitope-specific regulation. Carrier-specific induction of suppression for IgG anti-hapten antibody responses. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1730–1740. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.6.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong-Yin W, Russell M W. Induction of mucosal and systemic immune responses by intranasal immunization using recombinant cholera toxin B subunit as an adjuvant. Vaccine. 1998;16:286–292. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isaka M, Yasuda Y, Mikzokami M, Kozuka S, Taniguchi T, Matano K, Maeyama J I, Mizuno K, Morokuma K, Ohkuma K, Goto N, Tochikibo K. Mucosal immunization against hepatitis B virus by intranasal co-administration of recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen and recombinant cholera toxin B subunit as an adjuvant. Vaccine. 2001;19:1460–1466. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeannin P, Renno T, Goetsch L, Miconnet I, Aubry J P, Delneste Y, Herbault N, Baussant T, Magistrelli G, Soulas C, Romero P, Cerottini J C, Bonnefoy J Y. OmpA targets dendritic cells, induces their maturation and delivers antigen into the MHC class I prsentation pathway. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:502–508. doi: 10.1038/82751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyd J M, Cripps A W. Killed whole bacterial cells, a mucosal delivery system for the induction of immunity in the respiratory tract and middle ear: an overview. Vaccine. 1999;26:1775–1781. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemoine D, Francotte M, Préat V. Nasal vaccine from fundamental concepts to vaccine development. STP Pharma Sciences. 1998;8:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lise L D, Mazier D, Jolivet M, Audibert F, Chedid L, Schlesinger D. Enhanced epitopic response to a synthetic human malarial peptide by preimmunization with tetanus toxoid carrier. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2658–2661. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2658-2661.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowell G H, Kaminski R W, VanCott T C, Slike B, Kersey K, Zawoznik E, Loomis-Price L, Smith G, Redfield R R, Amselem S, Birx D L. Proteosomes, emulsomes, and cholera toxin B improve nasal immunogenicity of human immunodeficiency virus gp160 in mice: induction of serum, intestinal, vaginal, and lung IgA and IgG. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:292–301. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McWilliam A S, Nelson D, Thomas J A, Holt P G. Rapid dendritic cell recruitement is a hallmark of the acute inflammatory response at mucosal surfaces. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1331–1336. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moller S A, Borrebaeck C A. A filter immunoplaque assay for the detection of antibody-secreting cells in vitro. J Immunol Methods. 1985;79:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neutra M R, Frey A, Kraehenbuhl J P. Epithelial M cells: gateways for mucosal infection and immunization. Cell. 1996;86:345–348. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen T, Samuelson P, Sterky F, Merle-Poite C, Robert A, Baussant T, Heauw J F, Uhlen M, Binz H, Stahl S. Chromosomal sequencing using PCR-based biotin-capture method allowed isolation of the complete gene for the outer membrane protein A of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Gene. 1998;210:93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oien N L. Induction of local and systemic immunity against human respiratory syncyial virus using a chimeric FG glycoprotein and cholera toxin B subunit. Vaccine. 1994;12:731–735. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plotnicky-Gilquin H, Goetsch L, Huss T, Champion T, Beck A, Haeuw J F, Nguyen T N, Bonnefoy J Y, Corvaïa N, Power U F. Identification of multiple protective epitopes (protectopes) in the central conserved domain of a prototype human respiratory syncytial virus G protein. J Virol. 1999;73:5637–5645. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5637-5645.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rauly I, Goetsch L, Heauw J F, Tardieux C, Baussant T, Bonnefoy J Y, Corvaïa N. Carrier properties of a protein derived from outer membrane protein A of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5547–5551. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5547-5551.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudin A, Johansson E L, Berquist C, Holmgren J. Differential kinetics and distribution of antibodies in serum and nasal and vaginal secretions after nasal and oral vaccination of humans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3390–3396. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3390-3396.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudin A, Riise G C, Holmgren J. Antibody responses in the lower respiratory tract and male urogenital tract in humans after nasal and oral vaccination with cholera toxin B subunit. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2884–2890. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2884-2890.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan E T, Butterton J R, Smith R N, Carroll P A, Crean T I, Calderwood S B. Protective immunity against Clostridium difficile toxin A induced by oral immunization with a live, attenuated Vibrio cholerae vector strain. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2941–2949. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2941-2949.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sad S, Gupta H M, Talwar G P, Raghupathy R. Carrier-induced suppression of antibody response to a self hapten. Immunology. 1991;74:223–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saunders N B, Shoemaker D R, Brandt B L, Moran E E, Larsen T, Zollinger W D. Immunogenicity of intranasally administered meningococcal native outer membrane vesicles in mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:113–119. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.113-119.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schutze M P, Leclerc C, Jolivet M, Audebert F, Chedid L. Carrier-induced epitopic suppression, a major issue for future synthetic vaccines. J Immunol. 1985;135:2319–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah S, Raghupathy R, Singh O, Talwar G P, Sodhi A. Prior immunity to a carrier enhances antibody responses to hCG in recipients of an hCG-carrier conjugate vaccine. Vaccine. 1999;17:3116–3123. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snider D P. The mucosal adjuvant activities of ADP-ribosylating bacterial enterotoxins. Crit Rev Immunol. 1995;15:317–348. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v15.i3-4.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spangler B D. Structure and function of cholera toxin and the related Eschericha coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:622–647. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.622-647.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verweij W R, de Haan L, Holtrop M, Agsteribbe E, Brands R, van Scharrenburg G J M, Wilschut J. Mucosal immunoadjuvant activity of recombinant Escherichia coli heat labile enterotoxin and its B subunit: induction of systemic IgG and secretory IgA responses in mice by intranasal immunization virus surface antigen. Vaccine. 1998;16:2069–2076. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker R I. New strategies for using mucosal vaccination to achieve more effective immunization. Vaccine. 1994;12:387–400. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh E E. Mucosal immunization with a subunit respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in mice. Vaccine. 1993;11:1135–1138. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walsh E E. Humoral mucosal and cellular immune response to topical immunization with a subunit respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:345–350. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H-Y, Russell M W. Comparison of systemic and mucosal priming for mucosal immune responses to a bacterial protein antigen given with or coupled to cholera toxin (CT) B subunit, and effects of effects of preexisting anti-CT immunity. Vaccine. 1994;12:215–222. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]