Abstract

We assessed relationships between early peripheral blood type I interferons (IFN) levels, clinical new early warning scores (NEWS), and clinical outcomes in hospitalized coronavirus disease‐19 (COVID‐19) adult patients. Early IFN‐β levels were lower among patients who further required intensive care unit (ICU) admission than those measured in patients who did not require an ICU admission during severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 infection. IFN‐β levels were inversely correlated with NEWS only in the subgroup of patients who further required ICU admission. To assess whether peripheral blood IFN‐β levels could be a potential relevant biomarker to predict further need for ICU admission, we performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses that showed for all study patients an area under ROC curve of 0.77 growing to 0.86 (p = 0.003) when the analysis was restricted to a subset of patients with NEWS ≥5 at the time of hospital admission. Overall, our findings indicated that early peripheral blood IFN‐β levels might be a relevant predictive marker of further need for an ICU admission in hospitalized COVID‐19 adult patients, specifically when clinical score (NEWS) was graded as upper than 5 at the time of hospital admission.

Keywords: COVID‐19, intensive care unit, NEWS, SARS‐CoV‐2, type I interferons

1. BACKGROUND

It is now well admitted that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) caused coronavirus disease‐19 (COVID‐19) clinical stages evolve from early infection (stage I) toward a mild‐to‐moderate pulmonary involvement without or with hypoxia (stage II), which can be followed by an hyperinflammatory phase resulting in potential severe clinical events requiring an intensive care unit (ICU) admission (clinical stage III). 1 Pathophysiology of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is clearly characterized by an early viral replicative phase in respiratory tract tissues associated with low viremia levels (clinical stage I) during 8 days after the first onset of symptoms, followed by an inflammatory phase occurring from 9 to 12 days after the first onset of symptoms (clinical stages II and III).

COVID‐19 inflammatory phase is characterized by a dysregulated inflammatory host response with an abnormal release of proinflammatory cytokines mediated by the activation of cell surface or intracellular toll like receptors (TLRs). 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Remarkably, a low interferon‐beta (IFN‐β) production in the peripheral blood of severe (clinical stage III) COVID‐19 patient was evidenced suggesting that type I IFN low production levels could drive the development of clinical stages II and III during the course of the SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 7 Type I IFNs influence the development of innate and adaptive immune responses limiting virus replication activities and preventing the development of severe clinical events during viral respiratory infections. 8 , 9 However, patterns of type I IFNs production during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, were investigated only in COVID‐19 patients at clinical stages II and III (9−12 days after onset of first symptoms). 7 , 10 In the present time, type I IFN expression pattern in the early phase of COVID‐19 (clinical stage I) and its potential relationship with further development of severe clinical events remains to be investigated.

In the present retrospective investigation, we assessed peripheral blood type I IFNs and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA levels at early phase (1−8 days after the first symptom onset) of COVID‐19 in adult patients who further required or not an ICU admission during infection. Among these two subsets of patients, we assessed potential relationships between early blood type I IFNs and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA levels and clinical new early warning scores (NEWS) at the time of hospitalization.

2. CLINICAL SAMPLES AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

From November 2020 to March 2021, peripheral blood EDTA‐plasma samples taken from adult patients had been stored at −80°C in Reims University Hospital until processing for anti SARS‐CoV‐2 IgM or IgG antibodies detection assays. This biobank was declared as a biological specimen's research collection and was registered by the French Ministry of High Education and Research (number DC‐2020‐4052).

From this research biobank samples (n = 4704 sampled patients), we retrospectively selected samples taken from adult patients (i) hospitalized in medicine wards for COVID‐19 (n = 1116); (ii) with a time delay less than 9 days between sample collection and onset of COVID‐19 symptoms (n = 183); (iii) with full clinical data available from a registered clinical data bank (Reims University Hospital GDPR number RMR004‐061120) elaborated for an internal purpose between March 1, 2020 and March 31, 2021 and focusing on COVID‐19 adult patients (n = 143). Patients who required palliative care or hospitalized directly in ICU were excluded from the study.

Finally, only 43 COVID‐19 adult patients with available frozen EDTA‐plasma samples and with full registered clinical data were included in this retrospective investigation.

2.2. Demographic, clinical, and medical data collection

For each selected patient, the following data had been previously registered in a declared database (RMR004‐061120) during their hospital stage: sex, age, comorbidities, immunocompromised state, date of symptoms onset, new early warning score (NEWS) graded at the time of hospital admission, 11 computerized tomography chest scan results (CT‐chest scan), drugs prescription, and further need for ICU admission and in‐hospital mortality. Demographic and clinical characteristics of study patients are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics COVID‐19 adult patients according to their further need for ICU admission

| Characteristics of COVID‐19 patients | No further need for ICU admission (n = 25) | Further need for ICU admission (n = 18) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender n (%) | 13 (52.0) | 10 (55.5) | 0.81 |

| Median age (years) [range] | 68 [28−92] | 63 [44−78] | 0.14 |

| Comorbidities n (%)a | 20 (80.0) | 12 (66.6) | 0.32b |

| Immunocompromised state n (%)c | 6 (24.0) | 4 (22.2) | 0.89b |

| Median time delay between symptoms/admission in Covid‐19 medicine ward (days) [range] | 5 [0−10] | 5 [0−11] | 0.22 |

| Median new early warning score [range] 11 | 3 [0−11] | 7 [2−11] | 0.0005 |

| Median maximal lung involvement observed on CT‐chest scan (%) [range] | 25 [0−75] | 50 [25−75] | 0.001 |

| Corticosteroids treatment n (%) | 14 (56.0) | 17 (94.4) | 0.01b |

| Antibiotics n (%) | 17 (68.0) | 18 (100.0) | 0.02b |

| Anticoagulation therapy n (%) | 24 (96.0) | 18 (100.0) | 0.99b |

| Isocoagulant heparin therapy n (%) | 10 (40.0) | 7 (38.8) | 0.99b |

| Optiflow nasal high flow therapy n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (33.3) | 0.007b |

| Mechanical ventilation n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (61.1) | <0.0001b |

| In‐hospital mortality n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (33.3) | 0.007b |

Note: (11): Covino et al. predicting intensive care unit admission and death for COVID‐19 patients in the emergency department using early warning scores. Resuscitation 156, 84–91 (2020).

Abbreviations: COVID‐19, coronavirus disease‐19; CT‐chest scan, computerized tomography chest scan; ICU, intensive care unit; RT‐PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2.

Comorbidities: arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, heart failure, obesity, chronic kidney failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or unbalanced asthma.

Fischer's exact test.

Immunocompromised state: cases of neoplasia (cancers), antineoplastic chemotherapy or previous corticosteroids, or immunosuppressive treatments.

2.3. Peripheral blood type I IFNs and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load

Using our research biological samples (registered research biobank), peripheral blood levels of IFN‐alpha (IFN‐α), Beta (IFN‐β) were determined on plasma samples using enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (Biotechne) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In parallel, SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load in EDTA plasma samples were quantified using droplet based digital PCR (dd‐PCR) (MOBICYTE Technical Platform), as previously described, 7 with Bio‐Rad SARS‐CoV‐2 dd‐PCR kit (Bio‐Rad). Viral RNA was extracted using QIAmp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Viral concentration results (copies/ml, cp/ml) were calculated considering the extraction volumes of plasma (140 µl).

2.4. Statistical analyses

Quantitative variables expressed as median [range] were compared using the Mann−Whitney U test. Qualitative variables expressed as percentages were compared using Fischer's exact test or Pearson's χ 2 if applicable. When linear regression was performed, slopes were compared using Spearman's test. When receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed, area under ROC curve, standard error, and p value were calculated using the trapezoid rule, the Hanley method, and Z ratio, respectively. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Early peripheral blood IFN‐β, SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA levels, and further need for ICU admission in COVID‐19 adult patients

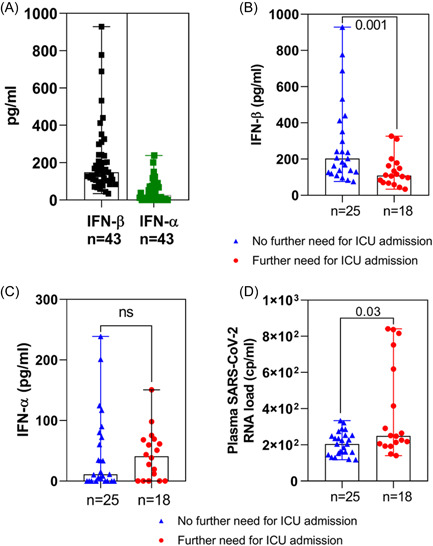

Type I IFNs and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load were assessed in peripheral blood samples taken from adult patients after a median time delay of 5 [1−8 days after the onset of symptoms] (Table 1). Among the 43 selected patients, early peripheral blood IFN‐β were detected in all the study patients with values ranging from 40 to 929 pg/ml, whereas peripheral blood IFN‐α were detectable in only 86% of the study patients with values ranging from non‐detectable to 326 pg/ml (Figure 1A). Because low type I IFN production levels could drive the development of COVID‐19 induced inflammatory phase, we segregated our patient group into two subsets according for their further need for an ICU admission during infection. Remarkably, levels of IFN‐β appeared to be significantly lower among the subset of patients who further required ICU admission than the subset of patients who did not further require ICU admission (p = 0.001) (Figure 1B). For IFN‐α levels, no significant differences between patient subsets requiring or not ICU admission was evidenced at the time of hospitalization (Figure 1C). In addition, the plasma SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load appeared to be significantly higher in patients who further required ICU admission than those measured in samples of patients who did not further required ICU admission (p = 0.03) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Early peripheral blood type I interferon (IFN) levels, SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load, and clinical new early warning scores in COVID‐19 adult patients requiring, or not further intensive care unit admission. At the time of hospital admission type I IFN and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load were measured in the peripheral blood of patients who further required (red circle, n = 18) or not (blue triangle, n = 25) further intensive unit care (ICU) admission. (A) IFN‐β (black square) and IFN‐α (green square) were measured using ELISA (enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay) in the peripheral blood of 43 COVID‐19 patients. (B, C) IFN‐β and IFN‐α levels were measured using a referenced ELISA.(D) Plasma SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA loads were assessed by a referenced digital PCR assay. Data indicated median values. p Values were determined using Mann−Whitney test by two‐way comparisons. COVID‐19, coronavirus disease‐19; ns, nonsignificant; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2.

3.2. Associations between early peripheral blood IFN‐β levels, SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA loads, and clinical NEWS

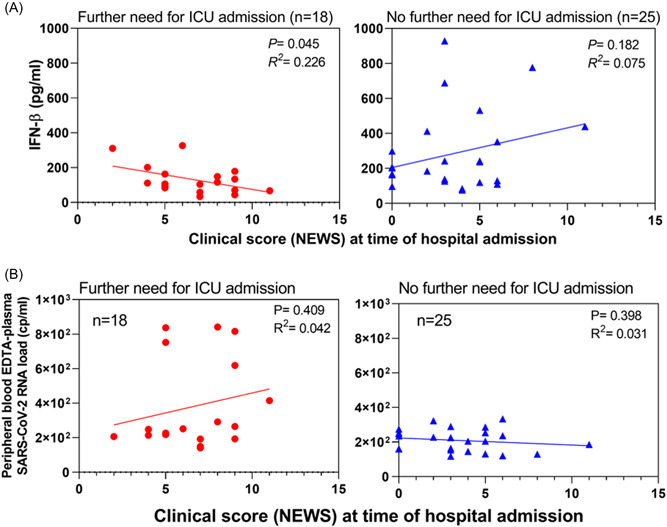

Because clinical NEWS had been previously associated with further ICU admission events in COVID‐19 adult patients, 11 we first sought for a potential association between NEWS and IFN‐β concentrations and then between NEWS and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load according to a further need for ICU admission. Among the subset of patients who further required an ICU admission, a significant negative correlation between NEWS and IFN‐β concentrations (p = 0.045; R 2 = 0.226) was observed (Figure 2A, left panel). By contrast a nonsignificant positive correlation was observed between NEWS and IFN‐β concentrations among the subset of patients who did not require further ICU admission (p = 0.182; R ² = 0.075) (Figure 2A, right panel). No significant correlation was evidenced between NEWS and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load among the two subsets of study patients (Figure 2B). Remarkably, when the analysis was restricted to a subset of patients with a NEWS ≥5 at hospital admission we observed a significant negative correlation between blood IFN‐β level and plasma SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load in the subset of COVID‐19 patient who did not further require an ICU admission. Such a correlation was not observed among patients who further require ICU admission (Supporting Information: Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Association of early peripheral blood type I IFN levels, SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load with clinical new early warning scores in COVID‐19 adult patients requiring, or not further intensive care unit admission. (A) Correlation analyses between clinical scores (NEWS) and IFN‐β levels in the peripheral blood of Covid‐19 adult patients at the time of hospital admission: left panel with red circles (n = 18) represent patients who further required an ICU admission; right panel with blue triangles (n = 25) represent patients who did not further require an ICU admission. Linear regression analyses were performed using Spearman's tests, p = 0.045; R 2 = 0.226 and p = 0.182; R 2 = 0.075, respectively. (B) Correlation analyses between clinical scores (NEWS) and peripheral blood plasma SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load in COVID‐19 patients at the time of hospital admission: left panel with red circles (n = 18) represent patients who further required an ICU admission and right panel with blue triangles (n = 25) represent patients who did not further require an ICU admission. Linear regression analyses were performed using Spearman's tests, p = 0.409; R 2 = 0.042 and p = 0.398; R 2 = 0.031, respectively. COVID‐19, coronavirus disease‐19; ICU, intensive care unit; IFN, interferon; NEWS, new early warning scores; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2.

3.3. Early blood IFN‐β concentrations accuracy to predict the need for a further ICU admission

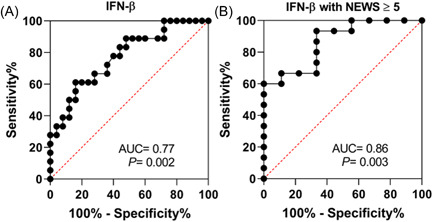

To assess whether peripheral blood IFN‐β levels could be a relevant biomarker to predict further need for ICU admission, we performed ROC curve analyses (Figure 3). Including all study patients, the sensitivity and specificity were respectively of 88% and 50% with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.77 (Figure 3A). Remarkably, the area under the ROC curve of blood IFN‐β level grew to 0.86 when the analysis was restricted to a subset of patients with a NEWS ≥5 at hospital admission indicating a relevant predictive value of early IFN‐β levels among the most clinically severe study patients. Among the subset of patients with NEWS ≥5 at hospital admission, peripheral blood IFN‐β levels below 107.6 pg/ml were associated to a further ICU requirement with a specificity of 100% and a sensitivity of 60% (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of IFN‐β for relevance to predict coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) severity. (A) ROC curve of blood IFN‐β levels among study Covid‐19 patients who further require or not an ICU admission; area under the ROC (AUC) = 0.77, p = 0.002. (B) ROC curve blood IFN‐β levels of Covid‐19 patients who further required or not an ICU admission when the analysis was restricted to patients with a NEWS ≥5 at admission. Area under the ROC (AUC) = 0.86, p = 0.003. ICU, intensive care unit; IFN, interferon; NEWS, new early warning scores.

4. DISCUSSION

Investigation of peripheral blood type I IFN production patterns in SARS‐CoV‐2 infected adult patients is of major interest for understanding COVID‐19 pathophysiology and clinical courses of infection. 7 , 10 Herein, we assessed relationships between early peripheral blood IFN‐beta (IFN‐β) levels, clinical NEWS, and clinical outcomes in SARS‐CoV‐2 infected adult patients hospitalized from 1 to 8 days after the first symptom onset (clinical stage I).

Among the 43 selected patients, anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 total antibodies were not detected and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α) were not measured at significant levels in peripheral blood (data not shown). These results were associated with detectable SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load confirming that study patients were at the viral phase of COVID‐19 (Figure 1D). Interestingly, early peripheral blood IFN‐β were detected in all the study patients, whereas IFN‐α were detectable only in 86% of the study patients (Figure 1A). Because low type I IFN production levels could drive the development of COVID‐19 induced inflammatory phase (clinical stages II and III), we segregated our patient group into two subsets according for their further need for an ICU admission. Interestingly, our findings indicated for the first time that patients who further required ICU admission demonstrated significant lower peripheral blood IFN‐β levels and higher SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load than those observed in patients who did not require ICU admission (Figure 1). Low early IFN‐β concentration levels in patient could be related to interindividual sequences variability in human genes implicated into the regulation of type I IFN innate immunity, 12 but also to the translation of SARS‐CoV‐2 nonstructural proteins inhibiting the IFN‐β promoter activation 13 or to preexisting peripheral blood auto‐antibodies directed against human type I IFNs. 14

Among the subset of COVID‐19 patients who further required ICU admission, a negative correlation between peripheral blood IFN‐β concentrations and clinical NEWS was evidenced, whereas no significant association was observed between clinical scores and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA levels (Figure 2). These findings were completed by ROC analyses and results indicated that early peripheral blood IFN‐β, but not SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA load, might be a relevant biomarker of a further ICU admission, specifically among patients with a NEWS ≥5 at the time of hospital admission (Figure 3B). Overall, these findings supported the concept that an early IFN‐β treatment in COVID‐19 adult patients hospitalized at phase I of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection might be of therapeutic benefit improving the clinical outcomes. However, these findings remain to be fully investigated in further prospective large multicenter clinical investigations.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Even if our study is a limited retrospective monocentric investigation conducted before large anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination campaigns in general population and before the emergence of new Delta or Omicron viral variants, our original findings revealed a significant association between early low peripheral blood IFN‐β levels and high clinical scores (NEWS) during SARS‐CoV‐2 clinical phase I. Overall, our findings indicated that early peripheral blood IFN‐β levels might be a relevant predictive marker of further need for an ICU admission in COVID‐19 adult patients, specifically when clinical score (NEWS) was graded as upper than 5 at hospital admission.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Andreoletti Laurent, N'Guyen Yohan, and Berri Fatma designed the study. Andreoletti Laurent, Berri Fatma, and N'Guyen Yohan wrote the manuscript. Andreoletti Laurent, Pham Bach‐Nga, and N'Guyen Yohan established the research biobank, the clinical data bank, and supervised the data collection. Berri Fatma and N'Guyen Yohan analyzed the data and designed the table and the figures. Callon Domitille helped for data collection. Berri Fatma, N'Guyen Yohan, Andreoletti Laurent, Callon Domitille, Labreil Anne‐Laure, Glenet Marie, Heng Laetitia, Bani‐Sadr Firouze, and Pham Bach‐Nga provided valuable input to interpretation of the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All these authors approved the final version of the present manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REIMS COVID‐19 STUDY GROUP

Collaborators included the following: Dr Ezekiel Bankole, Dr Loïs Bolko, Dr Michel Bonnivard, Dr Nelly Bourse, Dr Aurélie Brunet, Dr Sandy Carazo Mendez, Dr Clement Chopin, Dr Joël Cousson, Dr Sophie Demotier, Pr Gaetan Deslee, Dr Vincent Dupont, Dr Thierry Floch, Dr Julien Gautier, Dr Guillaume Giordano Orsini, Dr Sophie Giordano Orsini Dr Antoine Goury, Dr Marie Laure Gross, Dr Valentin Houannou, Dr Claire Lepouse, Dr Gauthier Lejeune, Dr Natacha Noël, Pr Jeanne Marie Perotin, Dr Juliette Romaru, Dr Jerome Tassain, Pr. Bruno Mourvillier.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC), University hospital of Reims (Grand‐Est, France) waived the requirement of informed consent and approved all methods and protocols. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles and Good Clinical Practices. Patients did not provide individual consent because of the retrospective and non‐interventional nature of this study, in accordance with French legislation. No patient raised an opposition to the use of their recorded medical data or their samples collected at the time of hospitalization for COVID‐19. Data confidentiality was preserved during this internal study (Reims University Hospital GDPR register number RMR004‐061120), and research collection of biological specimens was registered in French Ministry of Higher Education and Research as number DC‐2020‐4052.

Supporting information

Supplementary information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. Nicolas Richet (URCA, Université de Reims Champagne‐Ardenne, Plateau Technique MOBICYTE) for performing the Droplet Digital PCR analysis. We are indebted to Pr. Christine Hoeffel, Dr Clément Lier, Dr Coralie Barbe, Cécile Grasset, and Cécile Reppel for their help in the preparation of this manuscript. This work was supported by a research grant URCA‐2020‐EA4684 dedicated to research teams from the University of Reims Champagne‐Ardenne. This work was supported by a research grant URCA‐2020‐EA4684 dedicated to research teams from the University of Reims Champagne‐Ardenne.

Berri F, N'Guyen Y, Callon D, et al. Early plasma interferon‐β levels as a predictive marker of COVID‐19 severe clinical events in adult patients. J Med Virol. 2022;95:e28361. 10.1002/jmv.28361

Fatma Berri and Yohan N'Guyen contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID‐19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical–therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:405‐407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:762‐768. 10.1093/cid/ciaa248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choudhury A, Das NC, Patra R, Mukherjee S. In silico analyses on the comparative sensing of SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA by the intracellular TLRs of humans. J Med Virol. 2021;93:2476‐2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choudhury A, Mukherjee S. In silico studies on the comparative characterization of the interactions of SARS‐CoV‐2 spike glycoprotein with ACE‐2 receptor homologs and human TLRs. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2105‐2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mukherjee S. Toll‐like receptor 4 in COVID‐19: friend or foe? Future Virol. 2022;17:415‐417. 10.2217/fvl-2021-0249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hadjadj J, Yatim N, Barnabei L, et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID‐19 patients. Science. 2020;369:718‐724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang WLW, Coro ES, Rau FC, Xiao Y, Erle DJ, Baumgarth N. Influenza virus infection causes global respiratory tract B cell response modulation via innate immune signals. J Immunol. 2007;178:1457‐1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McNab F, Mayer‐Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O'Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:87‐103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dorgham K, Quentric P, Gökkaya M, et al. Distinct cytokine profiles associated with COVID‐19 severity and mortality. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:2098‐2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Covino M, Sandroni C, Santoro M, et al. Predicting intensive care unit admission and death for COVID‐19 patients in the emergency department using early warning scores. Resuscitation. 2020;156:84‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Q, Bastard P, Liu Z, et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life‐threatening COVID‐19. Science. 2020;370(6515):eabd4570. 10.1126/science.abd4570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lei X, Dong X, Ma R, et al. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bastard P, Rosen LB, Zhang Q, et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life‐threatening COVID‐19. Science. 2020;370:eabd4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.