Abstract

Objective

To assess women's perceptions of the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) received in hospitals in Romania during the COVID‐19 pandemic by mode of birth.

Methods

A validated anonymous online questionnaire based on WHO quality measures. Subgroup analysis of spontaneous vaginal birth (SVB), emergency cesarean, and elective cesarean and multivariate analyses were performed, and QMNC indexes were calculated. Maternal age, educational level, year of birth, mother born in Romania, parity, type of hospital, and type of professionals assisting the birth were used for multivariate analysis.

Results

A total of 620 women completed the survey. Overall, several quality measures suggested gaps in QMNC in Romania, with the lowest QMNC indexes reported for provision of care and availability of resources. Women who had either elective or emergency cesarean compared with those who had SVB more frequently lacked early breastfeeding (OR 2.04 and 2.13, respectively), skin‐to‐skin contact (OR 1.73 and 1.75, respectively), rooming‐in (OR 2.07 and 1.96, respectively), and exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (OR 2.27 and 1.64, respectively). Compared with elective cesarean, emergency cesarean had higher odds of ineffective communication by healthcare providers (OR 1.65), lack of involvement in choices (OR 1.58), insufficient emotional support (OR 2.07), and no privacy (OR 2.06). Compared with other modes of birth, a trend for lower QMNC indexes for emergency cesarean was observed for all domains, while for elective cesarean the QMNC index for provision of care was significantly lower.

Conclusion

Quality indicators of perinatal care remain behind targets in Romania, with births by cesarean the most affected.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

Keywords: breastfeeding, cesarean, childbirth, COVID‐19, IMAgiNE EURO, mode of birth, quality of care, Romania

Synopsis

Gaps in quality of maternal and newborn care indicators in Romania during COVID‐19 were identified for provision of care and availability of resources.

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic shook society. For the Romanian healthcare system, the pandemic amplified existing constraints and unresolved issues, and added new challenges. In response to the pandemic, the Romanian Ministry of Health issued guidelines on safety measures to be adopted inside obstetric wards to reduce the transmission of SARS‐Cov2. 1 Maternities were divided into COVID‐19 and non‐COVID‐19 hospitals, where pregnant women were admitted according to their SARS‐Cov‐2 status (i.e., positive or negative on RT‐PCR test). 1 For SARS‐Cov‐2‐positive asymptomatic pregnant women, no formal indication for cesarean was mentioned in the national recommendations, except in cases of rapid deterioration of clinical status during labor. 1 Women with confirmed or suspected COVID‐19 were separated from their newborns until they had two consecutive negative SARS‐Cov2 test results, a process that can take weeks. In addition, they were not allowed to breastfeed as their breast milk was treated as “waste”. 1

Despite progressive developments in prenatal diagnosis and standards of maternal and newborn care over time, Romania still faces multiple challenges in achieving high‐quality perinatal health care, with the high rate of cesareans one of the most concerning indicators. According to recent estimates, the cesarean rate in Romania is increasing significantly, with 37.1% of total births occurring by cesarean in 2016 2 ; this frequency reaches more than 80% in private clinics. 3

Several factors may be contributing to this high average rate of cesarean in Romania: few centers provide prenatal parental education, relatively high number of births in private clinics, low number of midwives, limited autonomy of midwives in the clinical decision process, women's preferences, 4 and increasing maternal age. 5 , 6 Although reducing the cesarean rate is recognized as a national priority, some of the current regulations (e.g., reimbursing hospitals with higher rates of cesarean compared with spontaneous vaginal birth [SVB]) may actually be a serious barrier to reducing the cesarean rate in Romania. 7

There is a lack of studies reporting maternal perceptions of quality of health care received in Romania. 8 The present paper provides data from Romanian responders participating in the IMAgiNE EURO study, conducted in several countries of the WHO European Region. 9 The aim of the present study was to report the perspectives of women who gave birth during the COVID‐19 pandemic on the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) received in Romania, grouped by mode of childbirth.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional study reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. 10 Women aged 18 years and older who gave birth in hospitals in Romania from March 1, 2020, up to February 29, 2021, were invited to participate.

Data collection methods have been detailed elsewhere. 9 , 11 Briefly, recruitment was prospective between September 2, 2020, and June 1, 2021, through a validated online anonymous questionnaire, 9 which included 40 questions (one for each single WHO standards‐based quality measure) equally distributed across four domains: provision of care, experience of care, availability of human and physical resources, and key organizational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic. The 40 quality measures contributed to a QMNC index, ranging from 0–400, with higher scores indicating higher adherence to WHO standards. 11 , 12

Data were collected on a centralized platform using REDCap 8.5.21 (Vanderbilt University). A descriptive analysis was conducted, subgrouping women into three groups by mode of birth: SVB, elective cesarean, and emergency cesarean based on the possible responses to the question “How was your baby born?”, with possible response options: SBV, instrumental vaginal birth (by vacuum extraction or forceps), emergency cesarean during labor, emergency cesarean before going into labor, and planned or elective cesarean before going into labor. The number of instrumental vaginal births was too small and was therefore excluded from the analysis. Although emergency cesarean (either during or before labor) and elective cesarean share characteristics, they differ in many aspects of maternal and fetal outcomes that may affect the perception of quality of care; therefore, they were treated separately. A definition of labor was provided in the questionnaire, per the NICE guidelines for intrapartum care of mother and babies. 13 For women providing data on all 40 quality measures, the QMNC indexes were calculated according to predefined criteria. 9 Demographic variables, quality measures, and the QMNC index referring to the four domains were compared between groups by mode of birth using χ2 test, ANOVA, or Mann–Whitney test, according to type of variable (categorical or continuous) and normality. Odds ratios were calculated for quality measures. To further investigate differences among groups, in case of statistical significance, pairwise comparisons were conducted using Bonferroni adjustment. Multivariable quantile regression models were developed with the QMNC index as the dependent variable and including all sociodemographic variables (i.e. maternal age, educational level, year of birth, mother born in Romania), parity, type of hospital (public or private), and type of professionals assisting the woman as independent variables, to account for potential confounding of crude associations by other variables. Data were processed using Stata/SE version 14.0 (Stata Corp) and R version 4.1.1. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The IMAgiNE EURO study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo” Trieste, Italy (IRB‐BURLO 05/2020 15.07.2020) and was conducted according to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) regulations. This was an online anonymous survey that women could decide to join on a voluntary basis; no data elements that could disclose maternal identity were collected, answers were recorded directly into a centralized platform hosted in Italy, and no data were treated elsewhere, therefore no further ethical approval was required in Romania. Data transmission and storage were secured by encryption. Each of the participants provided informed consent prior to responding to the survey.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Maternal characteristics

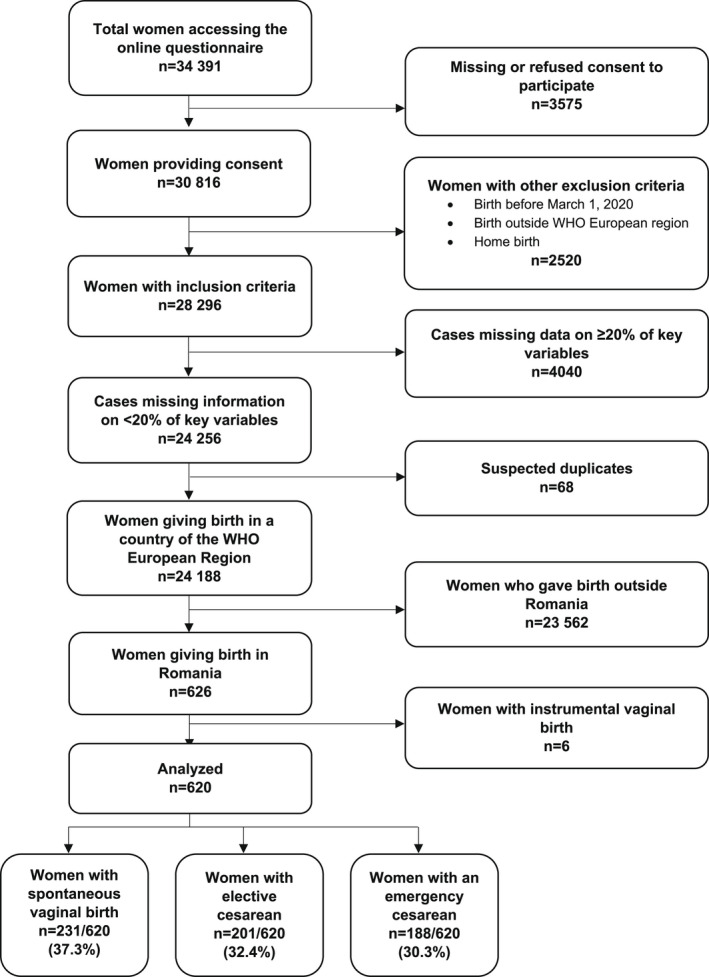

After exclusions had been considered, a total of 24 188 women gave birth in a WHO European region country. Of these, 23 562 (97.4%) gave birth outside Romania, leaving 626 (2.6%). After excluding six women who had an instrumental vaginal birth, 620 women who gave birth in Romania were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Each birth mode accounted for approximately one‐third of the total births. There were significant differences among the groups by birth mode: (1) being assisted by an obstetrician/gynecologist was significantly more frequent in women who had either an elective or emergency cesarean (P < 0.001); (2) SVB occurred more frequently in younger women (P < 0.001) and in public facilities (P < 0.001); and (3) emergency cesarean occurred more frequently in older women (P = 0.019); (4) elective cesarean was more frequent in private facilities (P < 0.001). Midwives were involved more frequently in SVB than in emergency and elective cesareans (P < 0.001) (Table 1) Overall, cesarean accounted for 72.7% (n = 136) of total births (n = 187) in private facilities versus 57.8% (n = 247 of total 419 births) in public facilities (P < 0.001). From the total number of cesareans performed, elective cesarean was more frequent than emergency cesarean in private versus public health facilities (58.8% [n = 80 from total 136 cesareans] vs. 47.9% [n = 116 from total 242 cesareans]; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of responders.

| Total No. (%) | Spontaneous vaginal birth No. (%) | Elective cesarean No. (%) | Emergency cesarean a No. (%) | P value f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 620 | 231 | 201 | 188 | |

| Age, year | |||||

| 18–24 | 34 (5.5) | 24 (10.4) b | 7 (3.5) | 3 (1.6) c | <0.001 |

| 25–30 | 258 (41.6) | 95 (41.1) | 82 (40.8) | 81 (43.1) | 0.884 |

| 31–35 | 241 (38.9) | 89 (38.5) | 77 (38.3) | 75 (39.9) | 0.941 |

| 36–39 | 58 (9.4) | 19 (8.2) | 24 (11.9) | 15 (8.0) | 0.309 |

| ≥40 | 15 (2.4) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (3.0) | 8 (4.3) c | 0.019 |

| Missing | 14 (2.3) | 3 (1.3) | 5 (2.5) | 6 (3.2) | 0.462 |

| Educational level d | |||||

| Elementary school | 4 (0.6) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.327 |

| Junior high school | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| High school | 82 (13.2) | 33 (14.3) | 28 (13.9) | 21 (11.2) | 0.605 |

| University degree | 251 (40.5) | 93 (40.3) | 83 (41.3) | 75 (39.9) | 0.958 |

| Postgraduate degree/Master/Doctorate or higher | 267 (43.1) | 98 (42.4) | 84 (41.8) | 85 (45.2) | 0.769 |

| Missing | 14 (2.3) | 3 (1.3) | 5 (2.5) | 6 (3.2) | 0.462 |

| Year of childbirth | |||||

| 2020 | 576 (92.9) | 215 (93.1) | 187 (93.0) | 174 (92.6) | 0.975 |

| 2021 | 27 (4.4) | 13 (5.6) | 7 (3.5) | 7 (3.7) | 0.485 |

| Missing | 17 (2.7) | 3 (1.3) | 7 (3.5) | 7 (3.7) | 0.235 |

| Women born in Romania | |||||

| Yes | 597 (96.3) | 227 (98.3) | 192 (95.5) | 178 (94.7) | 0.103 |

| No | 9 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (2.0) | 4 (2.1) | 0.250 |

| Missing | 14 (2.3) | 3 (1.3) | 5 (2.5) | 6 (3.2) | 0.462 |

| Parity | |||||

| 1 | 409 (66.0) | 154 (66.7) | 123 (61.2) | 132 (70.2) | 0.165 |

| >1 | 197 (31.8) | 74 (32.0) | 73 (36.3) | 50 (26.6) | 0.120 |

| Missing | 14 (2.3) | 3 (1.3) | 5 (2.5) | 6 (3.2) | 0.462 |

| Type of hospital | |||||

| Public | 419 (67.6) | 177 (76.6) b | 116 (57.7) | 126 (67.0) | <0.001 |

| Private | 187 (30.2) | 51 (22.1) b | 80 (39.8) | 56 (29.8) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 14 (2.3) | 3 (1.3) | 5 (2.5) | 6 (3.2) | 0.462 |

| Healthcare provider who assisted birth e | |||||

| Midwife | 251 (40.5) | 182 (78.8) b | 29 (14.4) | 40 (21.3) c | <0.001 |

| Nurse | 274 (44.2) | 102 (44.2) | 91 (45.3) | 81 (43.1) | 0.910 |

| Student | 8 (1.3) | 5 (2.2) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) | 0.326 |

| Ob/gyn resident | 152 (24.5) | 54 (23.4) | 43 (21.4) | 55 (29.3) | 0.173 |

| Ob/gyn specialist | 532 (85.8) | 174 (75.3) b | 188 (93.5) | 170 (90.4) c | <0.001 |

| I don't know | 35 (5.6) | 13 (5.6) | 6 (3.0) | 16 (8.5) | 0.062 |

| Missing | 43 (6.9) | 9 (3.9) | 17 (8.5) | 17 (9.0) | 0.070 |

Emergency cesarean includes both before and during labor.

Statistically significant adjusted P value (adj P < 0.05) in the comparison spontaneous vaginal birth versus elective cesarean.

Statistically significant adjusted P value (adj P < 0.05) in the comparison emergency cesarean versus spontaneous vaginal birth.

Wording on education levels agreed among partners during the Delphi. Questionnaire translated and back‐translated according to ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation Principles of Good Practice.

More than one possible answer.

Bold values are statistically significant. No statistically significant adjusted P value were found in the comparison elective cesarean versus emergency cesarean.

3.2. WHO standards‐based quality measures

In the domain of provision of care (Table 2, Supporting information Figure 1), overall, 68.2% (n = 423) of women lacked skin‐to‐skin contact, 68.5% (n = 425) lacked early breastfeeding, 52.3% (n = 324) did not exclusively breastfed at discharge, 47.9% (n = 297) reported inadequate breastfeeding support, and 43.9% (n = 272) reported lack of attention when needed. In addition, 43.4% (n = 149 out of 343 who went into labor) of women lacked pain relief during labor, and 68.0% (n = 157) had an episiotomy during SVB.

TABLE 2.

Provision of care, experience of care, and availability of resources. a

| Total | Spontaneous vaginal birth | Elective cesarean | Emergency cesarean | P value f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 620) | (n = 231) | (n = 201) | (n = 188) | ||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | ||

| Provision of care | |||||

| No pain relief in labor | 149/343 (43.4) | 124 (53.7) | NA | 25/112 (22.3) b | <0.001 |

| Episiotomy (in SVB) | 157/231 (68.0) | 157 (68.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| No pain relief after cesarean | 41/389 (10.5) | NA | 16 (8.0) | 25 (13.3) | 0.087 |

| No skin‐to‐skin contact | 423 (68.2) | 140 (60.6) c | 146 (72.6) | 137 (72.9) b | 0.007 |

| No early breastfeeding | 425 (68.5) | 135 (58.4) c | 149 (74.1) | 141 (75.0) b | <0.001 |

| Inadequate breastfeeding support | 297 (47.9) | 114 (49.4) | 89 (44.3) | 94 (50.0) | 0.453 |

| No rooming‐in | 298 (48.1) | 86 (37.2) c | 111 (55.2) | 101 (53.7) b | <0.001 |

| Not allowed to stay with the baby as wished | 156 (25.2) | 49 (21.2) | 52 (25.9) | 55 (29.3) | 0.162 |

| No exclusive breastfeeding at discharge | 324 (52.3) | 97 (42.0) c | 125 (62.2) | 102 (54.3) b | <0.001 |

| No immediate attention when needed | 272 (43.9) | 107 (46.3) | 82 (40.8) | 83 (44.1) | 0.512 |

| Experience of care | |||||

| No freedom of movements during labor | 115/343 (45.2) | 113 (48.9) | NA | 42/112 (37.5) b | <0.001 |

| No choice of birth position (in SVB) | 175/231 (75.8) | 175 (75.8) | NA | NA | NA |

| No information on newborn after cesarean | 199/389 (51.1) | NA | 92 (45.8) | 98 (52.1) | 0.210 |

| No consent requested for vaginal examination | 203 (32.7) | 94 (40.7) c | 44 (21.9) d | 65 (34.6) | <0.001 |

| No clear/effective communication from HCP | 273 (44.0) | 105 (45.5) | 75 (37.3) d | 93 (49.5) | 0.047 |

| No involvement in choices | 302 (48.7) | 122 (52.8) c | 82 (40.8) d | 98 (52.1) | 0.024 |

| Companionship not allowed | 579 (93.4) | 221 (95.7) | 182 (90.5) | 176 (93.6) | 0.101 |

| Not treated with dignity | 234 (37.7) | 94 (40.7) | 63 (31.3) | 77 (41.0) | 0.075 |

| No emotional support | 252 (40.6) | 104 (45.0) c | 60 (29.9) d | 88 (46.8) | 0.001 |

| No privacy | 172 (27.7) | 80 (34.6) c | 35 (17.4) d | 57 (30.3) | <0.001 |

| Abuse (physical/verbal/emotional) | 119 (19.2) | 53 (22.9) | 30 (14.9) | 36 (19.1) | 0.108 |

| Informal payment | 146 (23.5) | 50 (21.6) | 56 (27.9) | 40 (21.3) | 0.214 |

| Availability of physical and human resources | |||||

| No timely care by HCPs at hospital arrival | 121 (19.5) | 50 (21.6) | 31 (15.4) | 40 (21.3) | 0.204 |

| No information on maternal danger signs | 291 (46.9) | 115 (49.8) | 89 (44.3) | 87 (46.3) | 0.508 |

| No information on newborn danger signs | 319 (51.5) | 134 (58.0) c | 95 (47.3) | 90 (47.9) | 0.042 |

| Inadequate room comfort and equipment | 60 (9.7) | 22 (9.5) | 18 (9.0) | 20 (10.6) | 0.850 |

| Inadequate number of women per rooms | 54 (8.7) | 18 (7.8) | 18 (9.0) | 18 (9.6) | 0.804 |

| Inadequate room cleaning | 60 (9.7) | 23 (10.0) | 21 (10.4) | 16 (8.5) | 0.799 |

| Inadequate bathroom | 117 (18.9) | 43 (18.6) | 36 (17.9) | 38 (20.2) | 0.839 |

| Inadequate partner visiting hours | 514 (82.9) | 190 (82.3) | 167 (83.1) | 157 (83.5) | 0.940 |

| Inadequate number of HCPs | 126 (20.3) | 46 (19.9) | 37 (18.4) | 43 (22.9) | 0.540 |

| Inadequate HCP professionalism | 69 (11.1) | 19 (8.2) | 26 (12.9) | 24 (12.8) | 0.208 |

| Reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 | |||||

| Difficulties in attending routine antenatal visits | 354 (57.1) | 145 (62.8) | 104 (51.7) | 105 (55.9) | 0.064 |

| Any barriers in accessing the hospital | 249 (40.2) | 94 (40.7) | 72 (35.8) | 83 (44.1) | 0.241 |

| Inadequate info graphics | 161 (26.0) | 60 (26.0) | 44 (21.9) | 57 (30.3) | 0.166 |

| Inadequate wards reorganization | 235 (37.9) | 90 (39.0) | 68 (33.8) | 77 (41.0) | 0.321 |

| Inadequate room reorganization | 241 (38.9) | 87 (37.7) | 70 (34.8) | 84 (44.7) | 0.123 |

| Lacking one functioning accessible hand‐washing station e | 112 (18.1) | 38 (16.5) | 38 (18.9) | 36 (19.1) | 0.722 |

| HCP not always using PPE | 102 (16.5) | 36 (15.6) | 35 (17.4) | 31 (16.5) | 0.877 |

| Insufficient number of HCPs | 199 (32.1) | 71 (30.7) | 59 (29.4) | 69 (36.7) | 0.257 |

| Communication inadequate to contain COVID‐19‐related stress | 276 (44.5) | 105 (45.5) | 77 (38.3) | 94 (50.0) | 0.064 |

| Reduction in QMNC due to COVID‐19 | 345 (55.6) | 139 (60.2) | 98 (48.8) | 108 (57.4) | 0.050 |

Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare provider; NA, not applicable; SVB, spontaneous vaginal birth; PPE, personal protective equipment; QMNC, quality of maternal and newborn care.

All the indicators in the domains of provision of care, experience of care, and resources are directly based on WHO standards.

Statistically significant adjusted P value (adj P < 0.05) in the comparison emergency cesarean versus spontaneous vaginal birth.

Statistically significant adjusted P value (adj P < 0.05) in the comparison spontaneous vaginal birth versus elective cesarean.

Statistically significant adjusted P value (adj P < 0.05) in the comparison elective cesarean versus emergency cesarean.

Defined as at least one functioning and accessible hand‐washing station (near or inside the room where the mother was hospitalized) supplied with water and soap or with disinfectant alcohol solution.

Bold values are statistically significant.

In the domain of provision of care, significant differences were found among groups by birth mode for several WHO standards‐based quality measures, with a trend for women who had a cesarean showing the lowest scores (Table 2). Specifically, when compared with women who had SVB, those who had either an elective or emergency cesarean more frequently lacked early breastfeeding (OR 2.04; 95% CI, 1.35–3.07 and OR 2.13; 95% CI, 1.4–3.25, respectively), skin‐to‐skin contact (OR 1.73; 95% CI, 1.15–2.59 and OR 1.75; 95% CI, 1.15–2.65, respectively), rooming‐in (OR 2.07; 95% CI, 1.42–3.06 and OR 1.96; 95% CI, 1.32–2.9, respectively), and exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (OR 2.27; 95% CI, 1.54–3.35 and OR 1.64, 95% CI, 1.11–2.42, respectively). The only indicator showing poorest QMNC in women with SVB was lack of pain relief, which was more frequent than in women who experienced emergency cesarean (OR 7.55, 95% CI, 4.61–12.38).

In the domain of experience of care, key findings included: 93.4% (n = 579) of women were not allowed a companion for as long as needed, 48.7% (n = 302) felt that they were not involved in choices, 37.7% (n = 234) reported that they were not treated with dignity, 19.2% (n = 119) reported abuse, and 23.5% (n = 146) reported making informal payments. Indicators were significantly worse in the emergency cesarean group compared with (in this order) the SVB and elective cesarean groups. Emergency versus elective cesarean had higher odds of ineffective communication with healthcare providers (HCPs) (OR 1.65; 95% CI, 1.1–2.46), lack of involvement in choices (OR 1.58, 95% CI, 1.06–2.36), insufficient emotional support (OR 2.07; 95% CI, 1.36–3.14), and no privacy (OR 2.06; 95% CI, 1.28–3.33).

In the domain of availability of physical resources, 82.9% (n = 514) of women reported inadequate visiting hours for their partner, while 46.9% (n = 291) did not receive adequate information on maternal danger signs (e.g. excessive vaginal bleeding, difficulty in urinating, difficulty in breathing). There were no significant differences among groups by birth mode, except for information on newborn danger signs, which was less frequent in women with SVB (58.0% [n = 134] vs. 47.3% [n = 95] elective cesarean and 47.9% [n = 90] for emergency cesarean; P = 0.042).

In the domain of reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 (Table 2, Supporting information Figure 2), 55.6% (n = 345) of women from the whole sample perceived a reduction in quality of care (P = 0.050). In addition, a high percentage of women reported difficulties in attending routine antenatal visits during pregnancy (57.1%, n = 354), inadequate communication with HCPs to contain COVID‐19‐related stress (44.5%, n = 276), inadequate reorganization of hospital wards (37.9%, n = 235), and inadequate numbers of HCPs (32.1%, n = 199), with no significant differences by birth mode.

3.3. QMNC indexes and multivariate analysis

Overall, the median lowest scores in the QMNC indexes were reported in the domains of provision of care (60, IQR 45.0–75.0) and availability of human and physical resources (65, IQR 45.0–80.0) (Table 3). In the domain of experience of care there were significant differences by birth mode, with women who had an emergency cesarean (65, IQR 50.0–81.2) or SVB (65, IQR 50.0–80.0) showing significantly lower scores than those who had an elective cesarean (75, IQR 57.5–90.0) (P = 0.002) (supporting information Figure 3).

TABLE 3.

QMNC indexes by domain and mode of birth.

| QMNC index subdomains | Total (n = 438) | Spontaneous vaginal birth (n = 175) | Elective cesarean (n = 151) | Emergency cesarean (n = 112) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | ||

| Provision of care | 60.0 [45.0–75.0] | 60.0 [45.0–77.5] | 60.0 [45.0–75.0] | 60.0 [50.0–70.0] | 0.378 |

| Experience of care | 70.0 [50.0–85.0] | 65.0 [50.0–80.0] a | 75.0 [57.5–90.0] b | 65.0 [50.0–81.2] | 0.002 |

| Availability of physical and human resources | 65.0 [45.0–80.0] | 60.0 [45.0–75.0] | 65.0 [45.0–85.0] | 60.0 [40.0–80.0] | 0.498 |

| Reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19 | 80.0 [65.0–90.0] | 80.0 [65.0–90.0] | 80.0 [65.0–95.0] | 75.0 [55.0–90.0] | 0.106 |

| Total QMNC index | 270.0 [210.0–315.0] | 270.0 [215.0–307.5] | 280.0 [220.0–330.0] | 265.0 [203.8–306.2] | 0.135 |

Abbreviation: QMNC, quality of maternal and newborn care.

Statistically significant adjusted P value (adj P < 0.05) in the comparison spontaneous vaginal birth versus elective cesarean.

Statistically significant adjusted P value (adj P < 0.05) in the comparison elective cesarean versus emergency cesarean.

When the total QMNC indexes were corrected for other variables (Supporting information Table 1), women who had an elective cesarean, were multiparous, gave birth in private facilities, and were assisted by a midwife or obstetrician/gynecologist reported significantly higher QMNC scores in one or more centiles, while women born in other countries reported lower QMNC indexes.

When the QMNC index was analyzed by domain and adjusting for type of hospital (public or private), lower median QMNC indexes were observed in all of the four domains for cesarean, although this reached statistical significance (adjusted P < 0.05) only for provision of care (‐10 points and ‐5 for elective and emergency cesarean, respectively, compared to SVB) (supporting information Table 2). When compared with SVB, women who had an elective cesarean reported a lower QMNC index for provision of care (−10 points, P < 0.05), but a higher index for experience of care (+5, P < 0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first study in Romania using a standardized validated questionnaire to document the quality of perinatal care during the COVID‐19 pandemic, as assessed by women as key service beneficiaries. Previous preliminary publications from the IMAgiNE EURO study reporting data from 12 countries showed that the QMNC index reported by women giving birth in Romania was significantly lower than the QMNC index reported by women giving birth in most of the other 11 countries included. 9 , 14 , 15 The current article adds new participants to the previous data and provides additional analyses, exploring QMNC by mode of birth. Given the general lack of published evidence on the QMNC in Romania, 16 the study contributes by filling an evidence gap.

The findings from the present study confirm previous European reports which showed that the quality of hospital and specialist care in Romania was perceived below the European average 17 and add relevant information on perceived differences in the QMNC by birth mode, highlighting that the lowest scores were reported by women who had an emergency cesarean.

In the domain of provision of care, the major gaps observed were in the practices of essential newborn care, lack of pain relief in labor, and the high rate of episiotomy. Notably, many indicators in this domain suggested the lowest QMNC reported by women who had a cesarean. This is concerning, adding low quality of care reported by this group of women to the burden of the already high cesarean rate in Romania. Importantly, while women who had an emergency cesarean may have needed postpartum medical treatments that in some cases may have delayed skin‐to‐skin contact, early breastfeeding, and rooming‐in, for both SVB and elective cesarean there is no justification for the lack of these practices, which benefit both maternal and newborn health. This calls for immediate action to promote better essential care in Romania for babies born by cesarean. 9 , 18

Despite that previous studies have reported higher scores in the experience of care domain, our study calculated lower scores for women who had an emergency cesarean compared with women with SVB and elective cesarean (in this order). 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 Additionally, when comparing other European countries, quality measures in this domain, even for elective cesarean, were far beyond the European average. 9 Several factors may explain why mothers with SVB perceived lower QMNC in the experience of care domain compared with mothers who gave birth by elective cesarean. First, this may be explained by demographic characteristics, significantly different among groups, or by the sample selection. Secondly, these findings may reflect the expectations of women toward cesarean. Third, most births by elective cesarean occurred in private facilities and previous research highlighted that women who delivered in private facilities perceived better care than those delivering in public facilities 9 , 23 ; however, is uncertain whether this reflects objective quality or rather a subjective judgment. 9 Finally, some key indicators in the experience of care domain, such as the lack of involvement in choices and the lack of privacy (both reported as more frequent in mothers with SVB compared with elective cesarean), may have affected the perception of other indicators. These factors may also explain the higher total QMNC index reported for private facilities.

Indicators of availability of resources and reorganization of care were not statistically different by birth mode; however, several gaps were revealed, with top priorities being accessibility of care, communication related to stress, and inadequate ward organization. More than half of the respondents reported a reduction in the QMNC and difficulties in attending routine antenatal visits, which were, even before the pandemic, poorly accessible in Romania. 24 A national report from 2016 showed that 7.1% of women had any medical consultation before birth and 69% did not attend the recommend number of visits during the pregnancy. 2

The present study confirms the high rate of cesarean in Romania (62.7%), in line with the most recent report of the National Insurance House reporting 57.9% of singleton births by cesarean. 25 Notably, elective cesarean also includes cesarean on request. The National Guide for cesarean endorsed by the Ministry of Health specifies that the doctor will discuss this topic with the patient only “after the legislative frame will be set up”. In contrast, some experts consider that cesarean on request can be performed under general legislation referring to a patient's rights. 26 Due to this ambiguity in legislation, reporting is not compulsory and no official national data about the different subtypes of elective cesarean are currently available. However, since other studies in Romania confirm high rates of elective and emergency cesarean, 3 , 25 , 27 , 28 these data should drive a public debate to define appropriate evidence‐based policies to reduce the rate of cesarean.

This paper presents maternal characteristics by birth mode varying by age, type of hospital, and type of HCP related to the provision of quality of care during labour and childbirth. Regarding HCPs, the differences may be explained by the distinction in competencies between doctors and midwives and the Romanian legislation that restricts midwives' activity to monitoring labor and to a large extent to physiological birth. 29

Strengths of the study include a validated questionnaire, 9 , 11 based on the WHO quality measures, 12 and the participation of women from different regions of Romania. Official statistics do not provide such detailed information and most national studies have a smaller sample size. Therefore, the results presented in this article are a meaningful contribution to understanding women's perceptions surrounding perinatal care in Romania.

The study also has some limitations. As with any voluntary survey, it relies on willingness to participate, which might reduce the representativeness of the results. Online distribution may limit participation because 64% of individuals in Romania used the internet for social networking in 2021. 30 To reduce this risk, a mixed strategy for dissemination of the survey was developed and routinely monitored. It included dissemination via forums and other social networks of mothers, flyers, and posters, and direct contact of perinatal educators with women after birth in the hospital. Another possible weakness is that the survey collected data mainly from women with a high level of education. This may partly reflect the national trend seen in the last decade whereby the proportion of newborns born to women with a higher education level increased by 20%, 31 while in all other categories of education the numbers decreased. Nevertheless, level of education was not associated with QMNC. To the best of our knowledge, no other study has analyzed women's views on QMNC in Romania and the level of education, while previous studies exploring related themes were contradictory. In one study, level of education did not statistically correlate with confidence in the Romanian healthcare system in general, 32 although level of income was negatively related to the “overall impression”. In another study, patients with a higher level of education considered that they had better communication with the medical staff. 33

Finally, the sample included in this study may be slightly older than the national sample of women giving birth in Romania, although directly comparable data are not available. 34 This may also have affected results; however, in which direction cannot be predicted. According to previous data, older mothers access health services more frequently 2 and may have higher risks of cesarean 4 ; however, their expectation of QMNC may also be higher. In view of these limitations, we cannot extrapolate the results to the entire population of mothers. Nevertheless, the number of participants is reasonably large and reflects the current tendency of growth in internet users, in higher educated women, and women aged between 25 and 35 years of old. For targeted research on younger and older mothers (representing 9.3% and 16.3% of the total number of mothers in 2020), 35 other specific determinants should be included.

In conclusion, results from this study provide new data valuable for both researchers and policymakers, providing a comprehensive set of WHO standards‐based QMNC indicators and showing that major gaps remain in QMNC in Romania—with women who gave birth by emergency cesarean the most affected. There is an urgent need to understand the multiple underlying causes generating low quality of maternal and newborn care in Romania during the pandemic and to monitor trends over time and beyond the pandemic. Most importantly, it is critical to identify the most effective and sustainable interventions to improve QMNC and then take action.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MRO conceived the paper with major inputs from ML, AAS, and CMH. IM analyzed the data with major inputs from MRO, ML, and EPV. MIN and IN contributed to the interpretation of the data in the local context. MRO drafted the first version, with major inputs from ML. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

IMAgiNE EURO study group

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Amira Ćerimagić, NGO Baby Steps, Sarajevo; Croatia: Daniela Drandić, Roda – Parents in Action, Zagreb; Magdalena Kurbanović, Faculty of Health Studies, University of Rijeka, Rijeka; France: Rozée Virginie, Elise de La Rochebrochard, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Research Unit, Institut National d'Études Démographiques (INED), Paris; Kristina Löfgren, Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative (IHAB); Germany: Céline Miani, Stephanie Batram‐Zantvoort, Lisa Wandschneider, Department of Epidemiology and International Public Health, School of Public Health, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld; Italy: Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Benedetta Covi, Ilaria Mariani, Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste; Sandra Morano, Medical School and Midwifery School, Genoa University, Genoa; Israel: Ilana Chertok, Ohio University, School of Nursing, Athens, Ohio, USA and Ruppin Academic Center, Department of Nursing, Emek Hefer; Rada Artzi‐Medvedik, Department of Nursing, The Recanati School for Community Health Professions, Faculty of Health Sciences at Ben‐Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev; Latvia: Elizabete Pumpure, Dace Rezeberga, Gita Jansone‐Šantare, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Riga Stradins University and Riga Maternity Hospital, Riga; Dārta Jakovicka, Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Rīga; Agnija Vaska, Riga Maternity Hospital, Riga; Anna Regīna Knoka, Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Rīga; Katrīna Paula Vilcāne, Faculty of Public Health and Social Welfare, Riga Stradins University, Riga; Lithuania: Alina Liepinaitienė, Andželika Kondrakova, Kaunas University of Applied Sciences, Kaunas; Marija Mizgaitienė, Simona Juciūtė, Kaunas Hospital of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas; Luxembourg: Maryse Arendt, Professional Association of Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg; Barbara Tasch, Professional Association of Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, KannerKlinik, Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg, Luxembourg; Norway: Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, Sigrun Kongslien, Department of Community Medicine, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø; Eline Skirnisdottir Vik, Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen; Poland: Barbara Baranowska, Urszula Tataj‐Puzyna, Maria Węgrzynowska, Department of Midwifery, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw; Portugal: Raquel Costa, EPIUnit ‐ Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto; Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional, Porto; Lusófona University/HEI‐Lab: Digital Human‐environment Interaction Labs, Lisbon; Catarina Barata, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa; Teresa Santos, Universidade Europeia, Lisboa and Plataforma CatólicaMed/Centro de Investigação Interdisciplinar em Saúde (CIIS) da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon; Carina Rodrigues, EPIUnit ‐ Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto and Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional, Porto; Heloísa Dias, Regional Health Administration of the Algarve; Romania: Marina Ruxandra Otelea, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest and SAMAS Association, Bucharest; Serbia: Jelena Radetić, Jovana Ružičić, Centar za mame, Belgrade; Slovenia: Zalka Drglin, Barbara Mihevc Ponikvar, Anja Bohinec, National Institute of Public Health, Ljubljana; Spain: Serena Brigidi, Department of Anthropology, Philosophy and Social Work, Medical Anthropology Research Center (MARC), Rovira i Virgili University (URV), Tarragona; Lara Martín Castañeda, Institut Català de la Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya; Sweden: Helen Elden, Verena Sengpiel, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg; Karolina Linden, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg; Mehreen Zaigham, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institution of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Lund and Skåne University Hospital, Malmö; Switzerland: Claire de Labrusse, Alessia Abderhalden, Anouck Pfund, Harriet Thorn, School of Health Sciences (HESAV), HES‐SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Lausanne; Susanne Grylka‐Baeschlin, Michael Gemperle, Antonia N. Mueller, Research Institute of Midwifery, School of Health Sciences, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur.

DISCLAIMER

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Rome, Italy, in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste, Italy. We gratefully acknowledge all women who took the time to answer the questionnaire despite the burden of the COVID‐19 pandemic. We would also like to thank the following colleagues for their assistance with translation and dissemination of the Romanian questionnaire: Sinziana Ionita‐Ciurez, Ana Maita, Cristina Biciila, Raluca Dumitrescu (members of SAMAS Association). Special thanks to the IMAgiNE EURO study group for their contribution to the development of this project and support for this manuscript.

Otelea MR, Simionescu AA, Mariani I, et al. Women's assessment of the quality of hospital‐based perinatal care by mode of birth in Romania during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Results from the IMAgiNE EURO study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl. 1):126‐136. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14482

Funding informationThis work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Rome ‐ Italy, in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste ‐ Italy

Contributor Information

Anca Angela Simionescu, Email: anca.simionescu@umfcd.ro.

the IMAgiNE EURO Study Group:

Amira Ćerimagić, Daniela Drandić, Magdalena Kurbanović, Rozée Virginie, Elise de La Rochebrochard, Kristina Löfgren, Céline Miani, Stephanie Batram‐Zantvoort, Lisa Wandschneider, Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Benedetta Covi, Ilaria Mariani, Sandra Morano, Ilana Chertok, Rada Artzi‐Medvedik, Elizabete Pumpure, Dace Rezeberga, Gita Jansone‐Šantare, Dārta Jakovicka, Agnija Vaska, Anna Regīna Knoka, Katrīna Paula Vilcāne, Alina Liepinaitienė, Andželika Kondrakova, Marija Mizgaitienė, Simona Juciūtė, Maryse Arendt, Barbara Tasch, Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, Sigrun Kongslien, Eline Skirnisdottir Vik, Barbara Baranowska, Urszula Tataj‐Puzyna, Maria Węgrzynowska, Raquel Costa, Catarina Barata, Heloísa Dias, Marina Ruxandra Otelea, Jelena Radetić, Jovana Ružičić, Zalka Drglin, Serena Brigidi, Lara Martín Castañeda, Helen Elden, Verena Sengpiel, Karolina Linden, Mehreen Zaigham, Claire De Labrusse, Alessia Abderhalden, Anouck Pfund, Harriet Thorn, Susanne Grylka, Michael Gemperle, and Antonia Mueller

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bratila E, Vladareanu S, The Ministry of Health . Metodologia privind naşterea la gravidele cu infecţie suspicionată/confirmată cu SARS‐CoV‐2/Covid19, preluarea, îngrijirea şi asistenţa medicală a nou născutului (Romanian) [Methodology regarding childbirth in pregnant women with suspected/confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2/Covid19 infection, taking over, care and medical assistance of the newborn]. Ministry of Health, 2020. Accessed May 15, 2022. http://www.ms.ro/wp‐content/uploads/2020/04/Metodologia‐privindnasterea‐la‐gravidele‐cu‐infectie‐suspicionata‐confirmaa‐cu‐SARS‐COV‐2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suciu N, Nanu M, Stativa E, Novak C, Mihăilescu G. Study on the reproductive health in Romania. 2016. Accessed August 1, 2021. https://www.insmc.ro/wp‐content/uploads/2021/01/STUDIU_IOMC_final_23.09.2019_BT.pdf

- 3. Simionescu AA, Marin E. Caesarean birth in Romania: safe motherhood between ethical, medical and statistical arguments. Maedica (Bucur). 2017;12:5‐12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simionescu AA, Horobet A, Marin E, Belascu L. Who indicates Caesarean section in Romania? A cross‐sectional survey in tertiary level maternity on childbirth patients and doctors' profiles. Obstetrica Ginecologia. 2021;69:62. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rydahl E, Declercq E, Juhl M, Maimburg RD. Cesarean section on a rise ‐ Does advanced maternal age explain the increase? A population register‐based study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0210655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simionescu AA, Horobet A, Belascu L, Median DM. Real‐world data analysis of pregnancy‐associated breast cancer at a tertiary‐level hospital In Romania. Medicina. 2020;56:522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Health Insurance House . Ordinul 1068–627. 2021. Accessed August 1, 2021. http://www.casan.ro/media/pageFiles/01.07.2021‐‐Ordinulnr.201068‐627.pdf

- 8. Euro‐Peristat Project . European Perinatal Health Report. Core indicators of the health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2015. November 2018. https://www.europeristat.com/. Accessed August 1, 2021.

- 9. Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. Quality of facility‐based maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: online survey investigating maternal perspectives in 12 countries of the WHO European Region. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;13:100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453‐1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lazzerini M, Argentini G, Mariani I, et al. A WHO standards‐based tool to measure women's views on the quality of care around the time of childbirth at facility level in the WHO European Region: development and validation in Italy. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e048195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization . Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. WHO; 2016. Accessed August 1, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511216 [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies. NICE clinical guideline 190. December 2014. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190/resources/intrapartum‐care‐for‐healthy‐women‐and‐babies‐pdf‐35109866447557

- 14. Zaigham M, Linden K, Sengpiel V, et al. Large gaps in the quality of healthcare experienced by Swedish mothers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional study based on WHO standards. Women Birth. 2022;35:619‐627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, Giusti A, Valente EP, IMAgiNE EURO study group . Quality of care at childbirth: findings of IMAgiNE EURO in Italy during the first year of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;157:405‐417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies . State of Health in the EU. Romania: Country Health Profile 2019. OECD Publishing. 2019. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/docserver/f345b1db‐en.pdf?expires=1663247024&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=D84841E8237E401CE99731D31F50CDE2 [Google Scholar]

- 17. OECD/European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2020 . State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing. 2020. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/social‐issues‐migration‐health/health‐at‐a‐glance‐europe‐2020_82129230‐en [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zugravu C, Nanu MI, Moldovanu F, et al. The influence of perinatal education on breastfeeding decision and duration. Int J Child Health Nutr. 2018;7:74‐81. [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Pijl MSG, Kasperink M, Hollander MH, Verhoeven C, Kingma E, de Jonge A. Client‐care provider interaction during labour and birth as experienced by women: respect, communication, confidentiality and autonomy. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Olaru OG, Stanescu AD, Raduta C, et al. Caesarean section versus vaginal birth in the perception of woman who gave birth by both methods. J Mind Med Sci. 2021;8:127‐132. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Negrini R, da Silva Ferreira RD, Guimarães DZ. Value‐based care in obstetrics: comparison between vaginal birth and caesarean section. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schantz C, Panteliasc AC, de Loenzien M, et al. ‘A caesarean section is like you've never delivered a baby’: a mixed methods study of the experience of childbirth among French women. Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2021;12:69‐78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lazzerini M, Pessa Valente E, Covi B, et al. Rates of instrumental vaginal birth and cesarean and quality of maternal and newborn health care in private versus public facilities: Results of the IMAgiNE EURO study in 16 countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;. 159(Suppl 1):22‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. LeMasters K, Baber Wallis A, Chereches R, et al. Pregnancy experiences of women in rural Romania: understanding ethnic and socioeconomic disparities. Cult Health Sex. 2019;21:249‐262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. CAS . Raport final activitatea A.6. – Stabilirea metodei și a elementelor de calcul al costurilor la nivelul spitalelor pilot. Accessed August 25, 2021. http://cas.cnas.ro/media/pageFiles/Anexe%20Raport%20final%20A6.pdf

- 26. Ministry of Health, Romanian College of Physicians, Romanian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology . Cesarian section. Clinical guides series for obstetrics and gynecology. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://sogr.ro/wp‐content/uploads/2019/02/operatia‐cezariana‐.pdf

- 27. Ionescu CA, Ples L, Banacu M, Poenaru E, Panaitescu E, Traian Dimitriu MC. Present tendencies of elective caesarean delivery in Romania: geographic, social and economic factors. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67:1248‐1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Birjandi M, Nanu D. Ways to reduce cesarean surgery. Ro J Med Pract. 2019;14:108‐112. [Google Scholar]

- 29. OUG nr . 144/2008, ordonanta de urgenta privind exercitarea profesiei de asistent medical generalist, a profesiei de moasa si a profesiei de asistent medical, precum si organizarea si functionarea Ordinului Asistentilor Medicali Generalisti, Moaselor si Asistentilor Medicali din Romania. Accessed March 7, 2022. https://www.oammrbuc.ro/fisiere/oug_144_2008.pdf

- 30. Eurostat [website] . Digital economy and society statistics ‐ households and individuals. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics‐explained/index.php?title=Digital_economy_and_society_statistics_‐_households_and_individuals#Internet_usage

- 31. National Institute of Statistics 2019 . Tendinte sociale. Accessed March 7, 2022. https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/tendinte_sociale.pdf

- 32. Cosma SA, Bota M, Fleșeriu C, Morgovan C, Văleanu M, Cosma D. Measuring patients' perception and satisfaction with the romanian healthcare system. Sustainability. 2020;12:1612. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Popa D, Druguș D, Leașu F, Azoicăi D, Repanovici A, Rogozea LM. Patients' perceptions of healthcare professionalism‐a Romanian experience. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Institute of Statistics 2022 . Romanian Statistical Yearbook 2021. Accessed August 6, 2022. https://insse.ro/cms/ro/content/anuarul‐statistic‐al‐romaniei‐format‐carte‐cd‐rom

- 35. Ministry of Health, National Institute of Public Health . National Report on the Health Status of the Population. Accessed September 1, 2022. https://insp.gov.ro/download/cnepss/stare‐de‐sanatate/rapoarte_si_studii_despre_starea_de_sanatate/starea_de_sanatate/starea_de_sanatate/RAPORTUL‐NATIONAL‐AL‐STARII‐DE‐SANATATE‐A‐POPULATIEI‐%25E2%2580%2593‐2020.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.