Synopsis

A summary of the findings in the Supplement, highlighting the heterogeneity in reported quality of maternity care and inequalities within and between countries in the European region.

Experience of care is an essential component of quality health care. 1 In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched “Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities”, with domains inclusive of dignity, communication, autonomy, and emotional support. 2 A growing body of research highlights the importance of a positive care experience for women and providers, as well as the need for effective interventions to improve outcomes for women, newborns, and stillborn infants. 3 , 4

The early months of the COVID‐19 pandemic were filled with many concerns from families, health workers, and public health experts. 5 For maternal and newborn health, in addition to unknowns about SARS‐CoV‐2 susceptibility in pregnant women, vertical transmission, and disease severity among women and newborns, many questions arose about how to reduce transmission risk in maternal and newborn health facilities. In the face of uncertain and evolving scientific evidence, and in some cases insufficient protective equipment for patients and providers, different countries and health facilities took different approaches, with some implementing very restrictive policies. 6 This was in addition to general lockdown policies limiting movement, work, transport and, more specifically in the health sector, reassignment of various health workers to COVID‐19‐related duties. In maternity care services, 7 contrary to the WHO/UNICEF Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative guidance, some of these restrictions included excluding a companion of choice and not allowing family members to visit, separation of mothers and newborns (even where COVID‐19 had not been suspected), and discouraging breastfeeding. 8 , 9 , 10

In addition, key dimensions of experience of care such as patient participation, provision of emotional support, and attempts to reduce certain interventionist procedures of limited clinical value, were among the first aspects of care to be sidelined during the pandemic. 11 Although emotional support is widely recognized as being important to patient experiences and recovery, 12 many health authorities or facilities did not allow companions of choice or visits from family members, and some facilities routinely separated infants from parents in a, likely ineffective, effort to reduce transmission risk. 13

While there have been previous studies from individual countries examining women's and families' experiences utilizing healthcare services during the pandemic, IMAgiNE EURO (Improving MAternal Newborn carE In the EURO Region) was the first multicountry project in Europe to measure quality of maternal and newborn care during the pandemic using a uniform questionnaire based on the WHO maternal and newborn health standards. The project, coordinated by the WHO Collaborating Centre of the “Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico” (IRCCS) Burlo Garofolo in Trieste, Italy, was developed specifically to answer questions about how well the WHO standards were met, and how maternal and newborn care practices in health facilities were impacted during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Europe.

The IMAgiNE EURO project developed, tested, and deployed two online surveys: one for women who gave birth during the COVID‐19 pandemic (after March 1, 2020) and one for health workers providing maternal and newborn care in health facilities. The surveys included questions on sociodemographic characteristics, plus 40 questions based on the WHO standards in three categories: (1) provision of care; (2) experience of care; (3) and availability of human and physical resources, plus a fourth category of key organizational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic (Table 1). Specifically, some elements included understanding which adaptations to care had the greatest impact on women and their maternity care experiences, identifying policy changes undertaken, and assessing multicountry variability in maternity services in response to COVID‐19. The findings from these studies highlight what matters to women and how systems can adapt better during a disaster or a future health system shock, to ensure that the needs and wishes of women and their families are not only translated into improved quality of care generally, but also met during crises. The project also investigated the effects on health workers and working conditions and issues that were important to them for providing high‐quality care (forthcoming in separate analyses).

TABLE 1.

Domains captured by the IMAgiNE EURO survey

| Domain | Number of questions |

|---|---|

| Demographics | 24 (not included in index) |

| Provision of care | 10 |

| Experience of care | 10 |

| Availability of human and physical resources | 10 |

| Organizational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic (not based on WHO standards) | 10 |

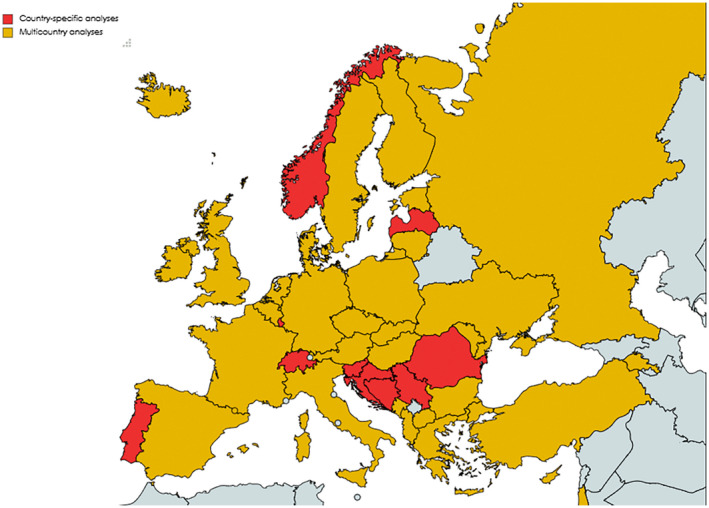

The survey was available in 25 languages and widely distributed by institutions in network partner countries using targeted dissemination material. Descriptions of the methodologies for validation and data collection are available elsewhere. 14 As of August 1, 2022, the IMAgiNE EURO network has collected over 60 000 responses from women and about 4000 from health workers, from 44 countries in the WHO European Region (Figure 1). A first set of results, including findings from the first year of the pandemic in 12 countries, was published in 2021. 15 The current Supplement includes a set of 10 in‐depth papers, each drawing from the same large dataset, but focusing on different geographic regions or aspects of care. While data from the perspective of health workers will be published separately, this Supplement focuses on the perspectives of women, including an analysis of medicalization of birth, comparison of experiences in public versus private facilities, identification of the experiences of migrant women compared with their nonmigrant counterparts, and seven papers with in‐depth analysis of specific country data from Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia‐Herzegovina, Romania, Portugal, Latvia, Norway, Luxembourg, and Switzerland.

FIGURE 1.

Map of countries participating in the IMAgiNE EURO study

[Correction added on 5 January 2023, after first online publication: Figure 1 has been updated.]

From seven national‐level papers in this Supplement (which represent findings from 10 countries), two main themes emerge: (1) a wide heterogeneity in quality of care exists between countries, with those in higher‐resource settings generally reporting higher quality of care, but still noting important quality gaps especially around informed consent and autonomy; and (2) inequity exists within countries, with marginalized groups (including those who do not speak the dominant language) generally reporting worse experiences of care. The multicountry papers reveal wide heterogeneity in reported quality of care between and within countries and highlight weak links in the quality of consent and communication. Although none of the IMAgiNE EURO surveys included baseline comparisons from before the pandemic, they did include questions about perceived changes in healthcare experiences due to COVID‐19. These reveal large differences across countries. National estimates can mask intracountry disparities, 16 and this effect may have been exacerbated during the pandemic. Therefore, besides assessing availability of resources, it is imperative to understand differences in healthcare provision, experiences, and outcomes by socioeconomic and migrant status, among others.

The in‐depth analyses presented in these papers reveal an alarmingly high prevalence of certain types of negative experiences. For example, over half the women reported an insufficient number of health workers; this has been documented in other studies and noted by maternal and newborn health workers themselves. Shortages of health workers have been identified in many settings before the emergence of COVID‐19, but the pandemic strained systems everywhere. In another online global multicountry survey in health facilities during the pandemic, newborn care was found to be compromised because of challenges to the workforce: 85% of health workers reported fearing for their health and 89% reported increased stress. 13 In a global survey of health workers in 71 countries, many providers believed their ability to provide respectful maternal and newborn care was limited by “compromised standards of care”, being “overwhelmed by rapidly changing guidelines and enhanced infection prevention measures”, and the inability to provide the type of “emotional and physical support” they would have wanted to. 17 In many countries in the IMAgiNE EURO survey, women perceived a reduction in quality due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. For some countries, however, quality index scores did improve between 2020 and 2021 (during the pandemic), as health systems better balanced risk reduction and maintenance of quality, and the introduction of the COVID‐19 vaccine allowed for the loosening of some restrictions. 18

Whether they were exacerbated by the pandemic or not, findings on various quality issues from individual countries can help pinpoint areas where attention may be needed. For example, in Serbia, over 25% of women reported having to give an informal payment, and in Bosnia, over 30% of women reported experiencing some type of abuse. 19 In Latvia, over 70% of women reported receiving no information on neonatal danger signs at discharge 20 ; in one region of Portugal, over 80% of women reported receiving fundal pressure. 21 Routinely collecting accurate and updated data on the quality of maternal and newborn care from those providing and using maternity services on their experiences of care provides an in‐depth roadmap for health researchers and policymakers to guide the necessary national quality improvements, which must be acted upon.

While pandemics and other shocks will undoubtedly challenge health systems, 22 those that have built trust through the provision of respectful evidence‐based care will be more prepared and resilient. National health authorities should commit to upholding the WHO standards, not only for maternal and newborn care, but for child and adolescent health, and for every service user. This needs to be done through a strong stewardship of the often‐fragmented health systems in European countries, where the interests and priorities of the various governmental agencies, health insurance companies, professional associations, and health facilities in various sectors (public, social security, university and teaching hospitals, faith‐based, for‐profit, etc) are not aligned under the same regulations and guidelines. Beyond studies such as IMAgiNE EURO and others, the onus of shedding light locally on failures to provide evidence‐based and respectful maternal and newborn care, before, during, and after the COVID‐19 pandemic, continues to fall on women, their families, and civil society organizations.

The papers in this Supplement are not without limitations: like most online surveys, the sample of respondents is biased to those with internet access, and with time and willingness to answer questions about their birth experience. Contextual factors that might be specific to a country, district, or subpopulation may not have been captured. Some distinctions were not possible in this dataset, such as the medical indication for interventions reported, the severity of certain co‐morbidities, timing of individual SARS‐CoV‐2 infections, if present, and the level of transmission risk and facility‐level policies (including in response to lockdowns) at given time periods. Finally, as the survey does not include data from before 2020, comparisons with a pre‐pandemic baseline are not possible. However, this set of analyses provides data from a standardized and validated questionnaire, with implementation of the survey in a wide range of countries according to a specific dissemination plan, and translation into 25 languages. As institutions and partners from more countries join the network, and more data are analyzed, more and more information will become available to help guide quality improvement initiatives.

Attention is needed to ensure that women's voices are heard, service user participation and informed consent are protected, and experience of care is seen as equally important as the provision of clinical care. Furthermore, even within higher‐income countries, there continue to be great disparities between subpopulations, often correlating with poorer care for those who are most marginalized, disadvantaged, and discriminated against, across Europe and beyond. These findings should help combat perceptions that quality of care is always high in high‐resource countries; in fact, there are shortcomings in many dimensions of care such as communication, nondiscrimination, and deprioritization of maternal and newborn care in the context of emergencies. Furthermore, there is an equivalent and urgent need to listen to the experiences of health workers, as sustainable progress is only feasible when each stakeholder is valued.

We have not yet recovered from the impact of COVID‐19. This Editorial was written in the summer of 2022 when unprecedented heatwaves and droughts were affecting Europe, at the same time as a military conflict resulting in 8 million displaced people, predominantly women and children, was being felt across the continent. Many countries still do not assure reproductive autonomy or universal health coverage, and few are well‐prepared for upcoming challenges to our health systems. The papers in this Supplement are as much about the actions we need to take to protect the health of women and newborns in the future, as they are about learning from the not‐too‐distant pandemic past.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Emma Sacks wrote the first draft. Lenka Beňová, Joy E. Lawn, Wendy Graham, Elise M. Chapin, Patience A. Afulani, Soo Downe, Tedbabe Degefie Hailegebriel, and Ornella Lincetto provided substantial comments and edits. All authors read and approved the final version.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Francesca Conway, and the team at ICRRS Burlo Garofalo for their support.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tunçalp Ӧ, Were WM, MacLennan C, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns‐the WHO vision. BJOG. 2015;122:1045‐1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities WHO MNH standards. WHO; 2016. Accessed September 2, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511216 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Downe S, Lawrie TA, Finlayson K, Oladapo OT. Effectiveness of respectful care policies for women using routine intrapartum services: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2018;15:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rubashkin N, Warnock R, Diamond‐Smith N. A systematic review of person‐centered care interventions to improve quality of facility‐based delivery. Reprod Health. 2018;15:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Graham WJ, Afolabi B, Benova L, et al. Protecting hard‐won gains for mothers and newborns in low‐income and middle‐income countries in the face of COVID‐19: call for a service safety net. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Data on Country Response Measures to COVID‐19. ECDC; 2022. Accessed September 2, 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications‐data/download‐data‐response‐measures‐covid‐19 [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization, UNICEF . Implementation guidance: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services – the revised Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative. Accessed September 2, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272943

- 8. Human Rights in Childbirth . HRIC; 2018. Accessed September 25, 2022. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Women/WG/DeprivedLiberty/CSO/Human_Rights_in_Childbirth.pdf

- 9. Semaan A, Audet C, Huysmans E, et al. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID‐19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Semaan A, Dey T, Kikula A, et al. “Separated during the first hours”—Postnatal care for women and newborns during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A mixed‐methods cross‐sectional study from a global online survey of maternal and newborn healthcare providers. PLoS Global Public Health. 2022;2:e0000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jolivet RR, Warren CE, Sripad P, et al. Upholding Rights Under COVID‐19: The Respectful Maternity Care Charter. Health Hum Rights. 2020;22:391‐394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sacks E, Finlayson K, Brizuela V, et al. Factors that influence uptake of routine postnatal care: Findings on women's perspectives from a qualitative evidence synthesis. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0270264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rao SPN, Minckas N, Medvedev MM, et al. Small and sick newborn care during the COVID‐19 pandemic: global survey and thematic analysis of healthcare providers' voices and experiences. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6:e004347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Valente EP, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. WHO Standards‐based questionnaire to measure health workers' perspective on the quality of care around the time of childbirth in the WHO European region: development and mixed‐methods validation in six countries. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e056753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. Quality of facility‐based maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: online survey investigating maternal perspectives in 12 countries of the WHO European Region. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;13:100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wirth ME, Balk D, Delamonica E, Storeygard A, Sacks E, Minujin A. Setting the stage for equity‐sensitive monitoring of the maternal and child health Millennium Development Goals. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:519‐527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Asefa A, Semaan A, Delvaux T, et al. The impact of COVID‐19 on the provision of respectful maternity care: findings from a global survey of health workers. Women Birth. 2022;35:378‐386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nedberg IH, Vik ES, Kongslien S, et al. Quality of health care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study in Norway and trends over time. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):85‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drandić D, Drglin Z, Mihevc B, et al. Women's perspectives on the quality of hospital maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study in Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, and Bosnia‐Herzegovina. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):54‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pumpure E, Jakovicka D, Mariani I, et al. Women's perspectives on the quality of maternal and newborn care in childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Latvia: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study on 40 WHO standards‐based quality measures. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):97‐112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Costa R, Barata C, Dias H, et al. Regional differences in the quality of maternal and neonatal care during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Portugal: results from the IMAgiNE EURO study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl 1):137‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization . Scoping review of interventions to maintain essential services for maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and older people during disruptive events . WHO; 2021. Accessed September 2, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038318 [Google Scholar]