Abstract

Objective

To compare women's perspectives on the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) around the time of childbirth across Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics 2 (NUTS‐II) regions in Portugal during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Methods

Women participating in the cross‐sectional IMAgiNE EURO study who gave birth in Portugal from March 1, 2020, to October 28, 2021, completed a structured questionnaire with 40 key WHO standards‐based quality measures. Four domains of QMNC were assessed: (1) provision of care; (2) experience of care; (3) availability of human and physical resources; and (4) reorganizational changes due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Frequencies for each quality measure within each QMNC domain were computed overall and by region.

Results

Out of 1845 participants, one‐third (33.7%) had a cesarean. Examples of high‐quality care included: low frequencies of lack of early breastfeeding and rooming‐in (8.0% and 7.7%, respectively) and informal payment (0.7%); adequate staff professionalism (94.6%); adequate room comfort and equipment (95.2%). However, substandard practices with large heterogeneity across regions were also reported. Among women who experienced labor, the percentage of instrumental vaginal births ranged from 22.3% in the Algarve to 33.5% in Center; among these, fundal pressure ranged from 34.8% in Lisbon to 66.7% in Center. Episiotomy was performed in 39.3% of noninstrumental vaginal births with variations between 31.8% in the North to 59.8% in Center. One in four women reported inadequate breastfeeding support (26.1%, ranging from 19.4% in Algarve to 31.5% in Lisbon). One in five reported no exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (22.1%; 19.5% in Lisbon to 28.2% in Algarve).

Conclusion

Urgent actions are needed to harmonize QMNC and reduce inequities across regions in Portugal.

Keywords: childbirth, COVID‐19, IMAgiNE EURO, maternal care, newborn care, Portugal, quality of care, respectful maternity care

Synopsis

Large inequities in the quality of maternal and newborn care in Portugal highlight the importance of promoting women's rights and respectful patient‐centered care.

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic, especially during its first months, has been a huge challenge for health systems. It affected the quality of maternal and neonatal care (QMNC) and increased inequalities in health care, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 with documented negative consequences for maternal and neonatal outcomes. 3 , 6 Specifically, around the time of childbirth, health care was impacted by disruption of healthcare facilities, in part due to lockdowns and reorganization of care due to COVID‐19, as well as reallocation of healthcare providers (HCPs) to COVID‐19 units. 5

Due to the novelty of the COVID‐19 pandemic, HCPs faced many uncertainties including a general lack of knowledge, lack of evidence‐based practices, and rapid changes in guidelines, 7 , 8 , 9 sometimes contradictory. Rapid variations in the recommendations related to care around the time of childbirth and continuous updates based on emerging evidence were challenging for decision‐making, not only due to their diversity but also due to high‐speed information flow. 10 , 11 By mid‐May 2020, more than 80 guidelines from 48 different organizations had been released, including recommendations on visits/support persons during pregnancy and childbirth (>80 recommendations), skin‐to‐skin contact (>20), rooming‐in (>60), breastfeeding (>120), or pain relief during labor (>80). 11 This was incredibly challenging for HCPs, since it demanded enormous flexibility and constant adaptation to clinical practices and reorganization of care. 12

Specific to Portugal, the General Directorate of Health (Direção Geral da Saúde, DGS) issued a guideline in March 2020 (Orientation 018/2020) to be followed by all Portuguese healthcare facilities. 13 This included a recommendation against skin‐to‐skin contact for all women with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19; mother–infant separation according to each woman's willingness; and the presence of a companion only if all safety conditions were insured by the facility (orientations 45, 47, and 28). On May 2020, a new DGS guideline (Orientation 026/2020) was issued recommending breastfeeding and case‐by‐case decision regarding skin‐to‐skin contact. 14 By October 2020, an update was issued 15 with amendments to the orientations that were more aligned with the World Health Organization (WHO) interim guidance released in May 2020, recommending that women with suspected, probable, or confirmed COVID‐19 should have access to a companion of choice during labor and childbirth, should not be separated from their infants without a medical reason, and should be encouraged to initiate and continue breastfeeding. 16

The Improving MAternal and Newborn carE in the EURO Region (IMAgiNE EURO) project had previously documented that QMNC around the time of childbirth had major gaps and huge variations across 12 countries in the WHO European Region. 17 However, no previous study had explored variations in QMNC among Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics 2 (NUTS‐II) 18 regions in Portugal, a country with serious gaps on information regarding QMNC, despite recent government recommendations (Resolution of the Assembly of the Portuguese Republic n.181/2021) to conduct studies on key indicators of women's mistreatment during childbirth. 19 The aim of the present study was to use data collected by the IMAgiNE EURO project to compare women's perspectives on QMNC around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic (between March 2020 and October 2021) at facility level, across NUTS‐II regions in Portugal.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

This is a cross‐sectional study reported according to STROBE guidelines 20 (Supporting Information Table S1). Participants were women who gave birth between March 1, 2020, and October 28, 2021, who completed an online survey of their childbirth experience in Portugal. Data were collected as part of the IMAgiNE EURO project and recorded using REDCap 8.5.21 (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA) via a centralized platform.

2.2. Ethics

Ethical authorizations were provided by the Institutional Review Board of the coordinating center, the IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo” Trieste, Italy (IRB‐BURLO 05/2020 15.07.2020) and by the ethical committees of other countries, including Portugal (Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto, CE20159). Participants provided informed consent before completing the anonymous questionnaire.

2.3. Participants

Participants were women who were aged 18 years and older, who gave birth in Portuguese hospital facilities, continent or islands, from March 1, 2020, to October 28, 2021. Exclusion criteria were home births or not providing information on the region of childbirth. Cases missing 20% or more answers on 45 key variables (including the 40 key quality measures and five key sociodemographic variables: date of birth, age, education, parity, whether a woman gave birth in the same country where she was born) were excluded. Sociodemographic variables, language and date of questionnaire completion, and key obstetric variables (e.g. mode and date of birth) were used to identify potential duplicates.

2.4. Data collection

Dissemination of the questionnaire, accessible by an online link, was conducted through social media platforms, using official communication channels, and leaflet posters with QR codes made available in some healthcare institutions.

The structured and validated questionnaire, based on the WHO standards for improving QMNC 21 was available in 24 languages, including Portuguese. It included QMNC questions and 24 sociodemographic questions including region of childbirth classified according to NUTS‐II 18 : North, Center, Lisbon Metropolitan area (Lisbon), Alentejo, Algarve, Madeira autonomous region, and Azores autonomous region. NUTS is a hierarchical system developed by EUROSTAT to divide the European Union economic territory to collect and harmonize European statistics and frame EU regional policies. NUTS‐II corresponds to the division of the territory in basic regions for the application of regional policies. 18

Two tailored versions of the questionnaire for women who experienced labor and those who had a prelabor cesarean were available, 17 each with a total of 40 key quality measures. The questionnaire included four domains with 10 questions each, with yes/no or multiple choice answers. Three domains correspond with the domains of the WHO standards: (1) provision of care; (2) experience of care; and (3) availability of human and physical resources. A fourth domain on reorganizational changes due to the COVID‐19 pandemic was also included. A predefined score (0–5‐10 points) was attributed to each possible answer, with higher scores indicating higher adherence to WHO standards. The QMNC index was calculated for each domain as the sum of all points in that domain (range 0 to 100), while the total QMNC index was calculated as the sum of all points (range 0 to 400). 17

2.5. Statistical analysis

We first described the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants by Portuguese region using frequencies for categorical variables and testing differences with a χ 2 or a Fisher exact test. Data from the regions without the minimum sample size (Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores) were regarded as exploratory findings, and were reported only for the descriptive analyses. These regions were excluded from comparisons across regions, since a minimum sample size of 100 was necessary to detect a minimum frequency on each quality measure of 4% ± 4%, with a confidence level of 96%.

Frequencies for each quality measure within each QMNC domain were computed overall and by region. Since different indicators were collected for women who underwent labor and women with prelabor cesarean, we presented results by these two groups. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to assess quality measure differences for women who experienced labor and women with prelabor cesarean, adjusting for potential confounders (i.e. parity, type of facility, mother born in Portugal, maternal age, maternal education, year of birth, presence of a midwife in the team who assisted birth, multiple birth).

The QMNC indexes are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) and differences between NUTS‐II regions with a sample size over 100, were tested with the Wilcoxon‐Mann Whitney test since they were not normally distributed. A graphical representation (kernel density) of the QMNC index was plotted for each Portuguese region. Multivariable quantile regression with robust standard errors was used due to non‐normal distribution of QMNC index and statistical evidence of heteroskedasticity. 22 We modeled the first, second, and third quartile, for QMNC index, using NUTS‐II regions (regions with less than 100 participants were merged into one group), parity, type of facility, mother born in Portugal, maternal age, maternal education, year of birth, presence of a midwife in the team who assisted birth, and multiple birth as independent variables, combining categories with low frequencies (i.e. for maternal age, the 15–25 years group was combined with the 25–30 years group, and the 35–40 years group with those aged more than 40 years old; for education junior high school and high school categories were combined together). The categories with the highest frequency were used as reference. A two‐tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE version 14.0 (Stata Corp) and R version 4.1.1. 23

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of participants

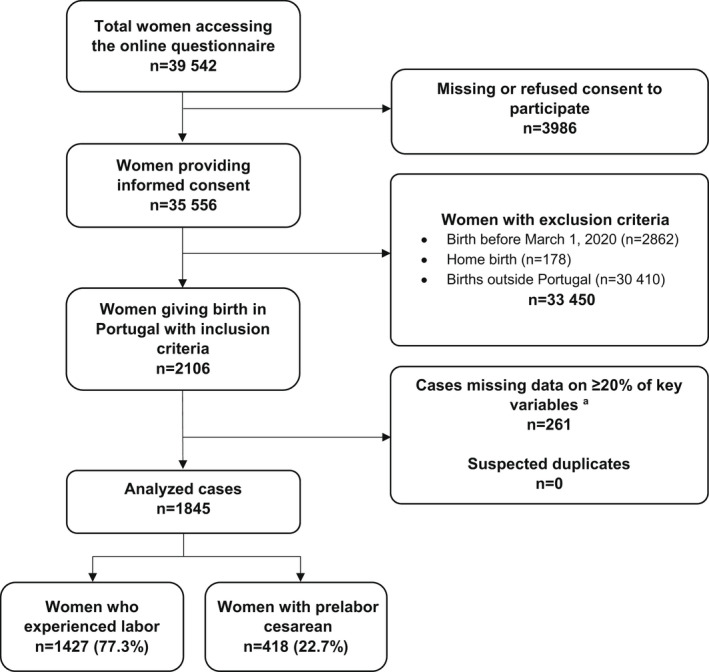

Overall, 89.9% (n = 35 556) of the women who accessed the online questionnaire provided informed consent to participate in the study. After exclusion of women who gave birth before March 1, 2020, or outside Portugal, home birth, missing values in 20% or more variables, and suspected duplicates, the analysis included 1845 women, of whom 1427 experienced labor and 418 had a prelabor cesarean (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram. aPercentage of missing data for each woman was calculated over 45 mandatory questions, including the 40 key quality measures and five key sociodemographic variables: date of birth, age, education, parity, whether a woman gave birth in the same country where she was born.

Most women were from the Lisbon (39.4%, n = 726), North (29.4%, n = 542), and Center regions (15.1%, n = 279), which accounted for 83.8% (n = 1547) of our sample (Table 1). According to the Statistics about Portugal and Europe (PORDATA), 24 live births in 2020 and in 2021 in those regions accounted for 83.9% and 83.5%, respectively, of total births in Portugal (Supporting Information Table S2).

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics by region

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 1845) No. (%) | North (n = 542) No. (%) | Center (n = 279) No. (%) | Lisbon (n = 726) No. (%) | Alentejo (n = 84) No. (%) | Algarve (n = 129) No. (%) | Madeira (n = 27) No. (%) | Azores (n = 58) No. (%) | P value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of birth | |||||||||

| 2020 | 1706 (92.5) | 503 (92.8) | 265 (95.0) | 670 (92.3) | 73 (86.9) | 119 (92.2) | 24 (88.9) | 52 (89.7) | 0.505 |

| 2021 | 93 (5.0) | 24 (4.4) | 8 (2.9) | 40 (5.5) | 7 (8.3) | 8 (6.2) | 2 (7.4) | 4 (6.9) | 0.282 |

| Missing | 46 (2.5) | 15 (2.8) | 6 (2.2) | 16 (2.2) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.4) | 0.882 |

| Mother born in Portugal | |||||||||

| Yes | 1668 (90.4) | 487 (89.9) | 251 (90.0) | 658 (90.6) | 79 (94.0) | 116 (89.9) | 22 (81.5) | 55 (94.8) | 0.968 |

| No | 136 (7.4) | 41 (7.6) | 22 (7.9) | 54 (7.4) | 1 (1.2) | 12 (9.3) | 4 (14.8) | 2 (3.4) | 0.905 |

| Missing | 41 (2.2) | 14 (2.6) | 6 (2.2) | 14 (1.9) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.7) | 0.672 |

| Age range, years | |||||||||

| 18–24 | 67 (3.6) | 21 (3.9) | 12 (4.3) | 19 (2.6) | 7 (8.3) | 3 (2.3) | 2 (7.4) | 3 (5.2) | 0.416 |

| 25–30 | 544 (29.5) | 159 (29.3) | 108 (38.7) | 193 (26.6) | 24 (28.6) | 41 (31.8) | 6 (22.2) | 13 (22.4) | 0.002 |

| 31–35 | 750 (40.7) | 217 (40.0) | 96 (34.4) | 311 (42.8) | 33 (39.3) | 54 (41.9) | 12 (44.4) | 27 (46.6) | 0.107 |

| 36–39 | 349 (18.9) | 107 (19.7) | 46 (16.5) | 150 (20.7) | 15 (17.9) | 20 (15.5) | 2 (7.4) | 9 (15.5) | 0.315 |

| ≥40 | 93 (5.0) | 24 (4.4) | 11 (3.9) | 39 (5.4) | 1 (1.2) | 10 (7.8) | 4 (14.8) | 4 (6.9) | 0.349 |

| Missing | 42 (2.3) | 14 (2.6) | 6 (2.2) | 14 (1.9) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.4) | 0.672 |

| Educational level b | |||||||||

| Junior High school | 4 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.879 |

| High school | 423 (22.9) | 133 (24.5) | 70 (25.1) | 127 (17.5) | 23 (27.4) | 48 (37.2) | 9 (33.3) | 13 (22.4) | <0.001 |

| University degree | 625 (33.9) | 167 (30.8) | 99 (35.5) | 248 (34.2) | 29 (34.5) | 50 (38.8) | 8 (29.6) | 24 (41.4) | 0.265 |

| Postgraduate degree/Masters /Doctorate or higher | 751 (40.7) | 226 (41.7) | 104 (37.3) | 335 (46.1) | 28 (33.3) | 30 (23.3) | 9 (33.3) | 19 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 42 (2.3) | 14 (2.6) | 6 (2.2) | 14 (1.9) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.4) | 0.672 |

| Parity | |||||||||

| First child | 1210 (65.6) | 360 (66.4) | 182 (65.2) | 469 (64.6) | 59 (70.2) | 85 (65.9) | 21 (77.8) | 34 (58.6) | 0.925 |

| >1 | 594 (32.2) | 168 (31.0) | 91 (32.6) | 243 (33.5) | 21 (25.0) | 43 (33.3) | 5 (18.5) | 23 (39.7) | 0.822 |

| Missing | 41 (2.2) | 14 (2.6) | 6 (2.2) | 14 (1.9) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.7) | 0.672 |

| Mode of birth | |||||||||

| Noninstrumental vaginal birth | 783 (42.4) | 220 (40.6) | 127 (45.5) | 301 (41.5) | 31 (36.9) | 67 (51.9) | 7 (25.9) | 30 (51.7) | 0.077 |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 439 (23.8) | 107 (19.7) | 78 (28.0) | 181 (24.9) | 26 (31.0) | 23 (17.8) | 14 (51.9) | 10 (17.2) | 0.015 |

| Cesarean | |||||||||

| Elective cesarean | 205 (11.1) | 67 (12.4) | 28 (10.0) | 87 (12.0) | 4 (4.8) | 13 (10.1) | 3 (11.1) | 3 (5.2) | 0.714 |

| Emergency cesarean during labor | 135 (7.3) | 37 (6.8) | 17 (6.1) | 55 (7.6) | 11 (13.1) | 5 (3.9) | 2 (7.4) | 8 (13.8) | 0.449 |

| Emergency cesarean prelabor | 283 (15.3) | 111 (20.5) | 29 (10.4) | 102 (14.0) | 12 (14.3) | 21 (16.3) | 1 (3.7) | 7 (12.1) | 0.001 |

| Type of facility | |||||||||

| Public | 1380 (74.8) | 434 (80.1) | 268 (96.1) | 412 (56.7) | 80 (95.2) | 108 (83.7) | 22 (81.5) | 56 (96.6) | <0.001 |

| Private | 423 (22.9) | 94 (17.3) | 5 (1.8) | 300 (41.3) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (15.5) | 4 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 42 (2.3) | 14 (2.6) | 6 (2.2) | 14 (1.9) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.4) | 0.672 |

| Type of healthcare provider who directly assisted the birth c | |||||||||

| Midwife | 744 (40.3) | 309 (57.0) | 106 (38.0) | 179 (24.7) | 34 (40.5) | 66 (51.2) | 15 (55.6) | 35 (60.3) | <0.001 |

| Nurse | 1469 (79.6) | 421 (77.7) | 220 (78.9) | 586 (80.7) | 68 (81.0) | 103 (79.8) | 22 (81.5) | 49 (84.5) | 0.611 |

| Student (i.e. before graduation) | 115 (6.2) | 38 (7.0) | 24 (8.6) | 32 (4.4) | 10 (11.9) | 6 (4.7) | 4 (14.8) | 1 (1.7) | 0.045 |

| Obstetrics registrar/medical resident (under postgraduate training) | 328 (17.8) | 106 (19.6) | 65 (23.3) | 116 (16.0) | 10 (11.9) | 15 (11.6) | 8 (29.6) | 8 (13.8) | 0.008 |

| Obstetrician/gynecologist | 1214 (65.8) | 345 (63.7) | 172 (61.6) | 509 (70.1) | 55 (65.5) | 69 (53.5) | 20 (74.1) | 44 (75.9) | 0.001 |

| I do not know (healthcare providers did not introduce themselves) | 270 (14.6) | 75 (13.8) | 61 (21.9) | 95 (13.1) | 15 (17.9) | 16 (12.4) | 5 (18.5) | 3 (5.2) | 0.003 |

| Other | 214 (11.6) | 65 (12.0) | 24 (8.6) | 85 (11.7) | 10 (11.9) | 12 (9.3) | 3 (11.1) | 15 (25.9) | 0.408 |

| Other characteristics | |||||||||

| Newborn admitted to neonatal intensive or semi‐intensive care unit | 147 (8.0) | 51 (9.4) | 21 (7.5) | 46 (6.3) | 11 (13.1) | 10 (7.8) | 4 (14.8) | 4 (6.9) | 0.244 |

| Mother admitted to intensive care unit | 8 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| Multiple birth | 33 (1.8) | 14 (2.6) | 9 (3.2) | 10 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.055 |

Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions were excluded from comparison due to low sample size.

Wording on education levels agreed among partners during the Delphi. Questionnaire translated and back‐translated according to ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation Principles of Good Practice.

More than one possible answer.

Most women were aged 25–35 years (70.2%, n = 1294), had a university degree (74.6%, n = 1376), and were first‐time mothers (65.6%, n = 1210). About one‐third had a cesarean (33.7%, n = 623) and 22.9% (n = 423) gave birth in a private hospital (Table 1).

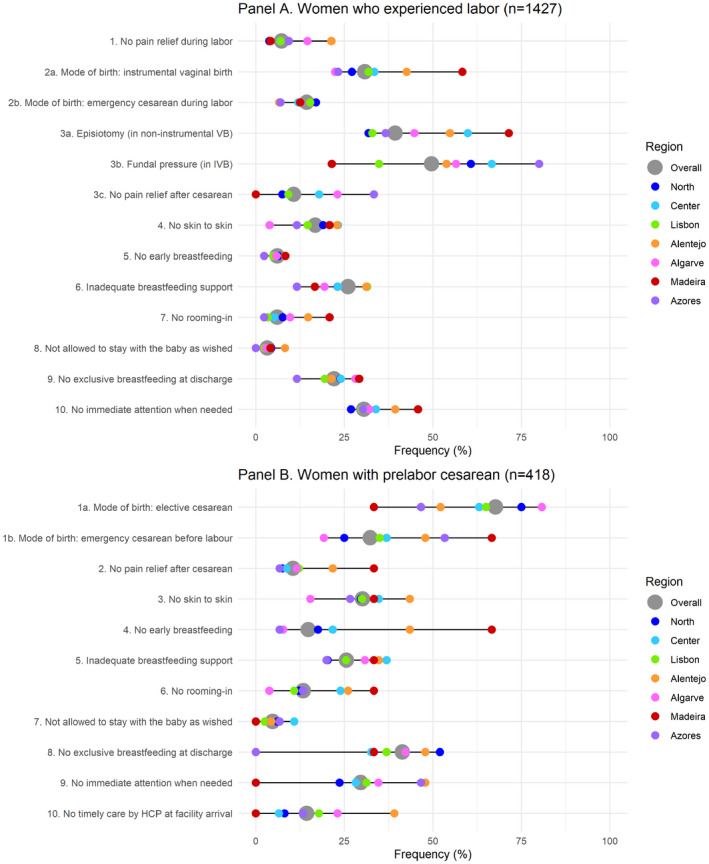

3.2. WHO standards‐based quality measures

In all domains of the QMNC, large variations were observed across NUTS‐II regions, suggesting coexistence of both high‐quality care and substandard care (Table 2, 3, 4, 5). In the domain of provision of care, comparisons excluding Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores, show that the differences included lack of skin‐to‐skin contact (ranging from 6.2% [n = 8] in Algarve to 25.1% [n = 70] in Center) and lack of rooming‐in (5.0% [n = 36] in Lisbon to 8.9% [n = 48] in North) (Table 2). Among women who experienced labor, the proportion of instrumental vaginal birth (IVB) was 30.8% (n = 439) with variation between 22.3% (n = 23) in Algarve to 33.5% (n = 78) in Center; among these, fundal pressure was performed in 49.7% (n = 218), varying from 34.8% (n = 63) in Lisbon to 66.7% (n = 52) in Center (Figure 2, Supporting Information Table S3). Episiotomy was performed in 39.3% (n = 308) of the noninstrumental vaginal births (VB), varying between 31.8% (n = 70) in the North region to 59.8% (n = 76) in Center. About one in four women reported inadequate breastfeeding support (26.1% [n = 372]; 19.4% [n = 20] in Algarve to 31.5% [n = 179] in Lisbon) and one in five reported no exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (22.1% [n = 315]; 19.5% [n = 111] in Lisbon to 28.2% [n = 29] in Algarve). Comparing women who experienced labor with women who had a prelabor cesarean (Supporting Information Table S3), the rates were quite similar except for some indicators where the rates were almost doubled; for example, absence of skin‐to‐skin contact with the newborn (16.8% [n = 240] vs 30.1% [n = 126], respectively), no breastfeeding within the first hour (6.0% [n = 86] vs 14.8% [n = 62], respectively), no rooming‐in (6.0% [n = 86] vs 13.4% [n = 56], respectively), and no exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (22.1% [n = 315] vs 41.4% [n = 173], respectively).

TABLE 2.

Provision of care. Quality measures common to both women who experienced labor and women with prelabor cesarean (n = 1845)

| Overall (n = 1845) No. (%) | North (n = 542) No. (%) | Center (n = 279) No. (%) | Lisbon (n = 726) No. (%) | Alentejo (n = 84) No. (%) | Algarve (n = 129) No. (%) | Madeira (n = 27) No. (%) | Azores (n = 58) No. (%) | P value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4. No skin‐to‐skin contact | 366 (19.8) | 119 (22.0) | 70 (25.1) | 130 (17.9) | 24 (28.6) | 8 (6.2) | 6 (22.2) | 9 (15.5) | <0.001 |

| 5. No early breastfeeding | 148 (8.0) | 51 (9.4) | 29 (10.4) | 39 (5.4) | 15 (17.9) | 8 (6.2) | 4 (14.8) | 2 (3.4) | 0.002 |

| 6. Inadequate breastfeeding support | 479 (26.0) | 121 (22.3) | 71 (25.4) | 219 (30.2) | 27 (32.1) | 28 (21.7) | 5 (18.5) | 8 (13.8) | 0.009 |

| 7. No rooming‐in | 142 (7.7) | 48 (8.9) | 23 (8.2) | 36 (5.0) | 15 (17.9) | 11 (8.5) | 6 (22.2) | 3 (5.2) | 0.035 |

| 8. Not allowed to stay with the baby as wished | 66 (3.6) | 26 (4.8) | 11 (3.9) | 18 (2.5) | 6 (7.1) | 3 (2.3) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.7) | 0.132 |

| 9. No exclusive breastfeeding at discharge | 488 (26.4) | 171 (31.5) | 71 (25.4) | 169 (23.3) | 24 (28.6) | 40 (31.0) | 8 (29.6) | 5 (8.6) | 0.007 |

| 10. No immediate attention when needed | 560 (30.4) | 141 (26.0) | 92 (33.0) | 219 (30.2) | 35 (41.7) | 42 (32.6) | 11 (40.7) | 20 (34.5) | 0.137 |

Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions were excluded from comparison due to low sample size.

TABLE 3.

Experience of care. Quality measures common to both women who experienced labor and women with prelabor cesarean (n = 1845)

| Overall (n = 1845) No. (%) | North (n = 542) No. (%) | Center (n = 279) No. (%) | Lisbon (n = 726) No. (%) | Alentejo (n = 84) No. (%) | Algarve (n = 129) No. (%) | Madeira (n = 27) No. (%) | Azores (n = 58) No. (%) | P value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3. No clear/effective communication from healthcare provider | 526 (28.5) | 139 (25.6) | 95 (34.1) | 197 (27.1) | 33 (39.3) | 41 (31.8) | 8 (29.6) | 13 (22.4) | 0.053 |

| 4. No involvement in choices | 748 (40.5) | 188 (34.7) | 132 (47.3) | 296 (40.8) | 41 (48.8) | 56 (43.4) | 11 (40.7) | 24 (41.4) | 0.004 |

| 5. Companionship not allowed | 1162 (63.0) | 282 (52.0) | 248 (88.9) | 390 (53.7) | 71 (84.5) | 99 (76.7) | 18 (66.7) | 54 (93.1) | <0.001 |

| 6. Not treated with dignity | 568 (30.8) | 134 (24.7) | 120 (43.0) | 207 (28.5) | 35 (41.7) | 46 (35.7) | 12 (44.4) | 14 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| 7. No emotional support | 673 (36.5) | 143 (26.4) | 134 (48.0) | 270 (37.2) | 39 (46.4) | 52 (40.3) | 12 (44.4) | 23 (39.7) | <0.001 |

| 8. No privacy | 394 (21.4) | 98 (18.1) | 76 (27.2) | 142 (19.6) | 25 (29.8) | 31 (24.0) | 14 (51.9) | 8 (13.8) | 0.012 |

| 9. Abuse (physical /verbal /emotional) | 405 (22.0) | 87 (16.1) | 85 (30.5) | 156 (21.5) | 26 (31.0) | 32 (24.8) | 11 (40.7) | 8 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| 10. Informal payment | 13 (0.7) | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | 7 (1.0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.776 |

Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions were excluded from comparison due to low sample size.

TABLE 4.

Availability of human and physical resources. Quality measures common to both women who experienced labor and women with prelabor cesarean (n = 1845)

| Overall (n = 1845)No. (%) | North (n = 542)No. (%) | Center (n = 279)No. (%) | Lisbon (n = 726)No. (%) | Alentejo (n = 84)No. (%) | Algarve (n = 129)No. (%) | Madeira (n = 27)No. (%) | Azores (n = 58)No. (%) | P value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. No timely care by HCPs at facility arrival | 252 (13.7) | 53 (9.8) | 30 (10.8) | 124 (17.1) | 20 (23.8) | 19 (14.7) | 3 (11.1) | 3 (5.2) | 0.001 |

| 2. No information on maternal danger signs | 534 (28.9) | 153 (28.2) | 91 (32.6) | 181 (24.9) | 31 (36.9) | 35 (27.1) | 14 (51.9) | 29 (50.0) | 0.101 |

| 3. No information on newborn danger signs | 814 (44.1) | 227 (41.9) | 118 (42.3) | 309 (42.6) | 39 (46.4) | 72 (55.8) | 14 (51.9) | 35 (60.3) | 0.030 |

| 4. Inadequate room comfort and equipment | 88 (4.8) | 21 (3.9) | 19 (6.8) | 32 (4.4) | 7 (8.3) | 5 (3.9) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (3.4) | 0.294 |

| 5. Inadequate number of women per rooms | 115 (6.2) | 29 (5.4) | 25 (9.0) | 35 (4.8) | 8 (9.5) | 13 (10.1) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (3.4) | 0.017 |

| 6. Inadequate room cleaning | 69 (3.7) | 12 (2.2) | 10 (3.6) | 32 (4.4) | 4 (4.8) | 10 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.019 |

| 7. Inadequate bathroom | 264 (14.3) | 58 (10.7) | 63 (22.6) | 92 (12.7) | 19 (22.6) | 15 (11.6) | 11 (40.7) | 6 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| 8. Inadequate partner visiting hours | 1178 (63.8) | 253 (46.7) | 246 (88.2) | 430 (59.2) | 78 (92.9) | 108 (83.7) | 12 (44.4) | 51 (87.9) | <0.001 |

| 9. Inadequate HCP number | 237 (12.8) | 58 (10.7) | 39 (14.0) | 90 (12.4) | 16 (19.0) | 20 (15.5) | 3 (11.1) | 11 (19.0) | 0.357 |

| 10. Inadequate HCP professionalism | 100 (5.4) | 23 (4.2) | 21 (7.5) | 35 (4.8) | 10 (11.9) | 9 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.4) | 0.168 |

Abbreviation: HCP, healthcare provider.

Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions were excluded from comparison due to low sample size.

TABLE 5.

Reorganizational changes due to COVID‐19. Quality measures common to both women who experienced labor and women with prelabor cesarean (n = 1845)

| Overall (n = 1845) No. (%) | North (n = 542) No. (%) | Center (n = 279) No. (%) | Lisbon (n = 726) No. (%) | Alentejo (n = 84) No. (%) | Algarve (n = 129) No. (%) | Madeira (n = 27) No. (%) | Azores (n = 58) No. (%) | P value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Difficulties in attending routine antenatal visits | 870 (47.2) | 262 (48.3) | 136 (48.7) | 312 (43.0) | 41 (48.8) | 70 (54.3) | 15 (55.6) | 34 (58.6) | 0.045 |

| 2. Any barriers in accessing the facility | 593 (32.1) | 175 (32.3) | 82 (29.4) | 221 (30.4) | 25 (29.8) | 56 (43.4) | 12 (44.4) | 22 (37.9) | 0.024 |

| 3. Inadequate info graphics | 641 (34.7) | 170 (31.4) | 103 (36.9) | 256 (35.3) | 22 (26.2) | 56 (43.4) | 12 (44.4) | 22 (37.9) | 0.054 |

| 4. Inadequate wards reorganization | 661 (35.8) | 176 (32.5) | 131 (47.0) | 220 (30.3) | 33 (39.3) | 68 (52.7) | 15 (55.6) | 18 (31.0) | <0.001 |

| 5. Inadequate room reorganization | 686 (37.2) | 193 (35.6) | 130 (46.6) | 218 (30.0) | 38 (45.2) | 77 (59.7) | 17 (63.0) | 13 (22.4) | <0.001 |

|

6. Lacking one functioning accessible hand‐washing station |

182 (9.9) | 51 (9.4) | 30 (10.8) | 65 (9.0) | 11 (13.1) | 18 (14.0) | 3 (11.1) | 4 (6.9) | 0.322 |

| 7. HCP not always using PPE | 201 (10.9) | 49 (9.0) | 28 (10.0) | 75 (10.3) | 12 (14.3) | 21 (16.3) | 4 (14.8) | 12 (20.7) | 0.115 |

| 8. Insufficient HCP number | 513 (27.8) | 127 (23.4) | 89 (31.9) | 201 (27.7) | 30 (35.7) | 40 (31.0) | 7 (25.9) | 19 (32.8) | 0.046 |

|

9. Inadequate communication to contain COVID‐19‐related stress |

660 (35.8) | 163 (30.1) | 124 (44.4) | 266 (36.6) | 34 (40.5) | 42 (32.6) | 8 (29.6) | 23 (39.7) | 0.001 |

| 10. Reduction in QMNC due to COVID‐19 | 864 (46.8) | 220 (40.6) | 153 (54.8) | 336 (46.3) | 44 (52.4) | 70 (54.3) | 17 (63.0) | 24 (41.4) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare provider; PPE, personal protective equipment; QMNC, quality of maternal and newborn care.

Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions were excluded from comparison due to low sample size.

FIGURE 2.

Domain of provision of care indicators by region of childbirth (Two panels for women who experienced labor and women with prelabor cesarean) (Supporting Information Table S3). Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare provider; IVB, instrumental vaginal birth; VB, vaginal birth. Data are reported as percent frequency on the total sample (gray dot) and as percent frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each region (colored dots); horizontal gray line represents the range of the regional frequencies. All the indicators in the domain of provision of care are directly based on WHO standards. Indicators identified with letters (e.g. 3a, 3b) were tailored to take into account different mode of birth (i.e. noninstrumental VB, IVB, and cesarean). These were calculated on subsamples (e.g. 3a was calculated on non‐instrumental VB; 3b was calculated on IVB). Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions are reported in this descriptive analysis but results should be regarded only as exploratory findings due to the low sample size enrolled in these regions.

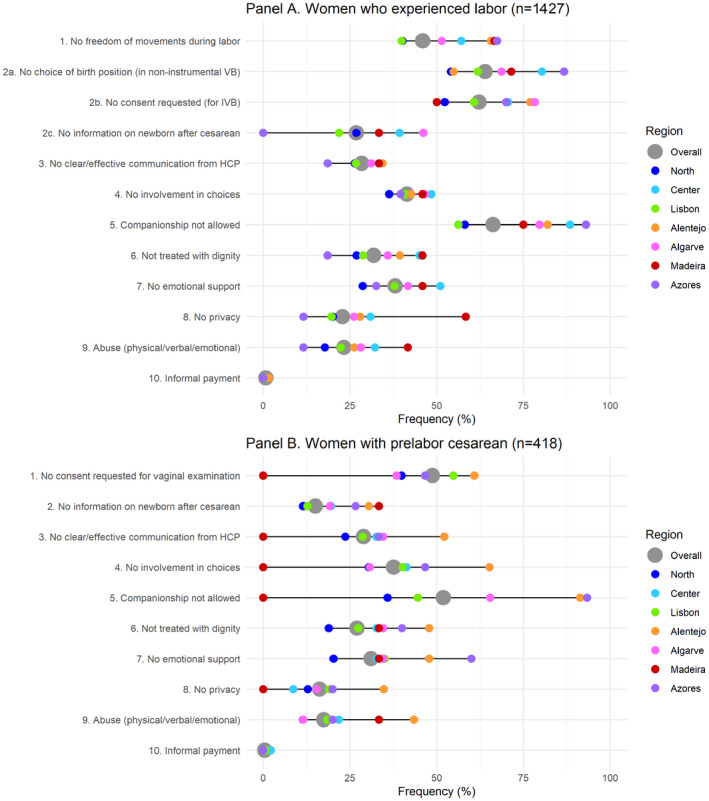

Similarly, there were large variations across regions in the domain of experience of care (Table 3). Among women who experienced labor, 66.2% (n = 945) had limitations imposed regarding the presence of a companion of choice (56.2% [n = 320] in Lisbon to 88.4% [n = 206] in Center) (Figure 3, Supporting Information Table S4). Among women with noninstrumental vaginal birth, 64.0% (n = 501) could not choose their birth position (54.1% [n = 119] in North to 80.3% [n = 102] in Center) and among those with IVB, for 62.2% (n = 273) consent was not requested for the use of instruments (52.3% [n = 56] in North to 78.3% [n = 18] in Algarve). An important proportion of women felt lack of emotional support (38.1% [n = 543]; 28.7% [n = 113] in North to 51.1% [n = 119] in Center), felt that they were not always treated with dignity (31.9% [n = 455]; 26.9% [n = 106] in North to 45.1% [n = 105] in Center), and that they were victims of physical/verbal/emotional abuse (23.3% [n = 332]; 17.8% [n = 70] in North to 32.2% [n = 75] in Center). For women with prelabor cesarean (Supporting Information Table S4), the rates were slightly lower for some quality measures compared with women who experienced labor; for example, no information on the newborn after cesarean (15.1% [n = 63] vs 26.8% [n = 55], respectively) or companionship not allowed (51.9% [n = 217] vs 66.2% [n = 945]).

FIGURE 3.

Domain of experience of care by region of childbirth (Two panels for women who underwent labor and women with prelabor cesarean) (Supporting Information Table S4). Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare provider; IVB, instrumental vaginal birth; VB, vaginal birth. Data are reported as percent frequency on the total sample (gray dot) and as percent frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each region (colored dots); horizontal gray line represents the range of the regional frequencies. All the indicators in the domain of experience of care are directly based on WHO standards. Indicators identified with letters (e.g. 2a, 2b) were tailored to take into account different mode of birth (i.e. noninstrumental VB, IVB, and cesarean). These were calculated on subsamples (e.g. 2a was calculated on noninstrumental VB; 2b was calculated on IVB). Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions are reported in this descriptive analysis, but results should be regarded only as exploratory findings due to the low sample size enrolled in these regions.

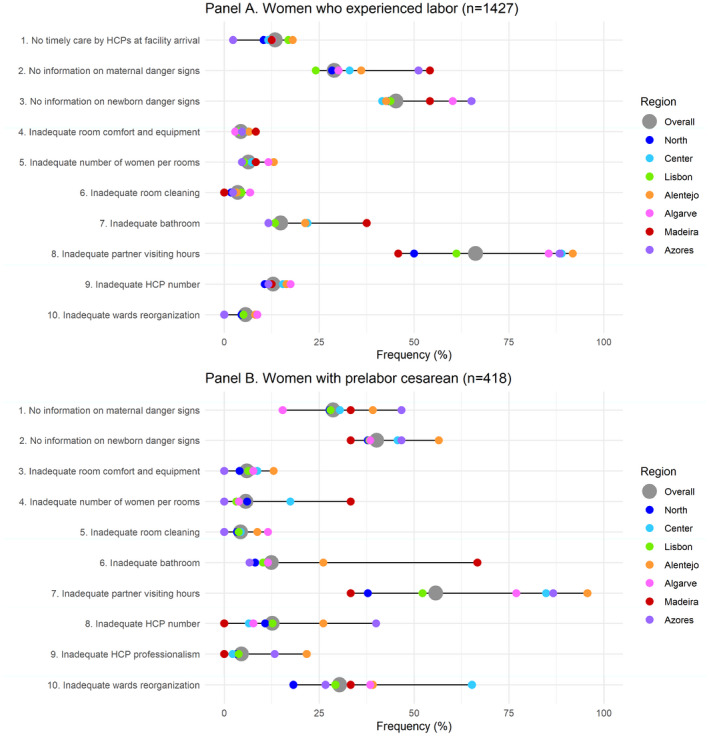

In the domain of availability of human and physical resources (Table 4), the largest variations across regions among women who experienced labor concerned lack of information on maternal danger signs (29.0% [n = 414]; 24.1% [n = 137] in Lisbon to 33.0% [n = 77] in Center), lack information on newborn danger signs (45.3% [n = 646]; 41.6% [n = 97] in Center to 60.2% [n = 62] in Algarve), and inadequate partner/other relative visiting hours (66.2% [n = 945]; 50.0% [n = 197] in North to 88.8% [n = 207] in Center) (Figure 4, Supporting Information Table S5). For women with prelabor cesarean, rates were similar as for women who experienced labor except for inadequate partner/other relatives visiting hours (55.7% [n = 233] vs 66.2% [n = 945], respectively).

FIGURE 4.

Availability of human and essential physical resources by region of childbirth (Two panels for women who experienced labor and women with prelabor cesarean) (Supporting Information Table S5). Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare provider. Data are reported as percent frequency on the total sample (gray dot) and as percent frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each region (colored dots); horizontal gray line represents the range of the regional frequencies. All the indicators in the domain of human and physical resources are directly based on WHO standards. Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions are reported in this descriptive analysis, but results should be regarded only as exploratory findings due to the low sample size enrolled in these regions.

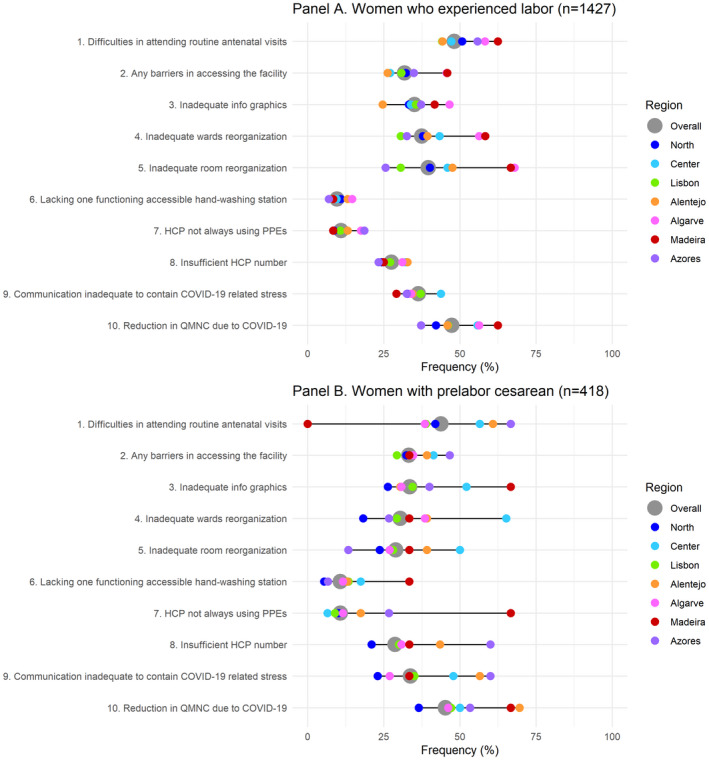

In the domain related to organizational changes due to the COVID‐19 pandemic (Table 5), the largest difference between regions among women who experienced labor concerned inadequate room organization (39.6% [n = 565]; 30.6% [n = 174] in Lisbon to 68.0% [n = 70] in Algarve) (Figure 5, Supporting Information Table S6). Reduction in QMNC due to the COVID‐19 pandemic was noted by 47.3% (n = 675) of women (42.1.0% [n = 166] in North to 56.3% [n = 58] in Algarve) and about one in three women reported inadequate HCP communication to contain COVID‐19‐related stress (36.4% [n = 519]; 32.7% [n = 129] in North to 43.8% [n = 102] in Center). Almost half (48.1%, n = 687) of these women reported difficulties in attending routine antenatal visits due to the COVID‐19 pandemic (44.1% [n = 251] in Lisbon to 58.3% [n = 60] in Algarve). The rates were similar for women with a prelabor cesarean and those who experienced labor, except for reports of inadequate ward organization (30.4% [n = 127] vs 37.4% [n = 534], respectively) and inadequate room organization (28.9% [n = 121] vs 39.6% [n = 565], respectively).

FIGURE 5.

Reorganizational changes due to the COVID‐19 pandemic by region of childbirth (Two panels for women who experienced labor and women with prelabor cesarean) (Supporting Information Table S6). Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare provider; PPE, personal protective equipment; QMNC, quality of maternal and newborn care. Data are reported as percent frequency on the total sample (gray dot) and as percent frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each region (colored dots); horizontal gray line represents the range of the regional frequencies. Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions are reported in this descriptive analysis, but results should be regarded only as exploratory findings due to the low sample size enrolled in these regions.

For women with a prelabor cesarean, gaps in quality measures, when corrected for women's characteristics, were more frequent compared with women who experienced labor (Supporting Information Table S7), including lack of skin‐to‐skin contact with the newborn (aOR 1.98; 95% CI, 1.50–2.63), no breastfeeding in the first hour (aOR 3.08; 95% CI, 2.08–4.56), no rooming‐in (aOR 2.78; 95% CI, 1.86–4.17), no exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (aOR 2.05; 95% CI, 1.58–2.67), inadequate room comfort or equipment (aOR 1.83; 95% CI, 1.08–3.11), and nonfunctioning and/or not easily accessible handwashing station (aOR 1.50; 95% CI, 1.00–2.23). Regarding the lack of information on newborn healthcare after cesarean, better practices were reported by women with prelabor cesarean (aOR 0.56; 95% CI, 0.30–0.88).

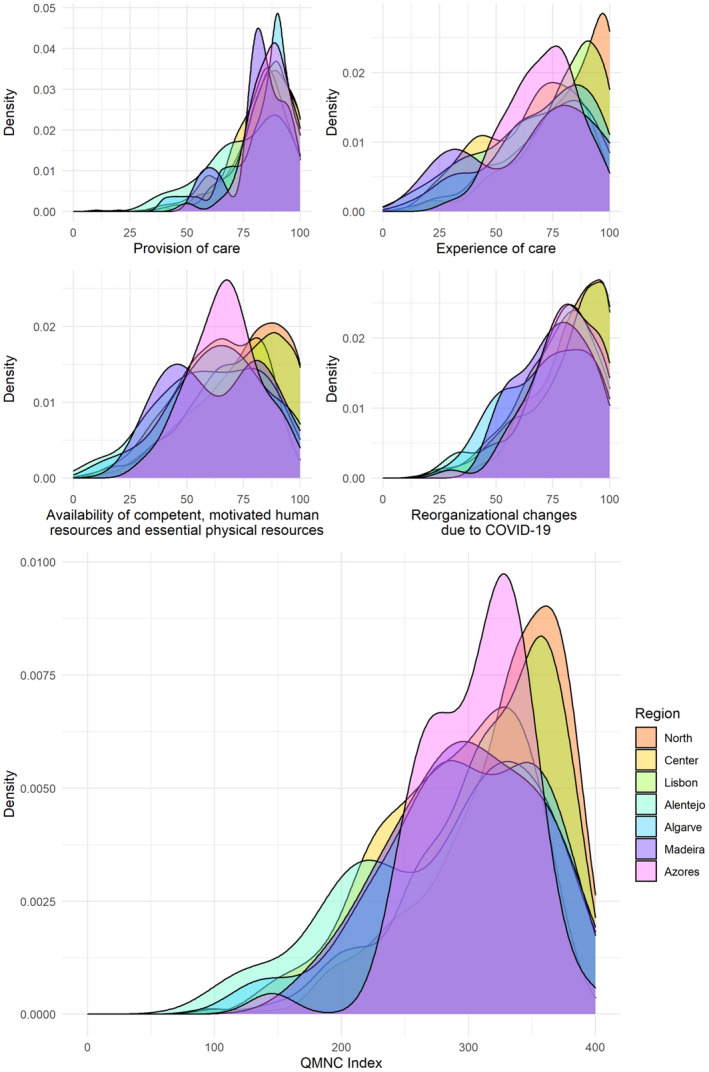

3.3. QMNC index

The overall median QMNC index was lowest in Center region and highest in the North and Lisbon regions (Figure 6, Supporting Information Table S8). Results of the quantile regression, corrected for potential confounders (Supporting Information Table S9), showed that taking Lisbon Metropolitan Area as a reference, the North region had a significantly higher QMNC index with increasing coefficients for lower quantiles (+15.0, +13.3, +10.0 points for the first, second, and third quartiles respectively), while Center and Algarve had a reduced QMNC index at one or more quantiles. A significantly higher QMNC index was reported by women who gave birth in private facilities compared with public facilities, or with a midwife in the team who assisted birth compared with births without a midwife. Women with a high school educational level registered a significantly higher QMNC index only on the first and third quartile, respectively. IVB and cesarean were associated with a lower QMNC index (IVB: −25.0, −15.0, −18.44 points; cesarean: −20.0, −10.0, −7.5 points on the first, second, and third quartiles, respectively) compared with noninstrumental vaginal birth.

FIGURE 6.

QMNC indexes: Provision of care, experience of care, availability of human and physical resources, reorganizational changes due to the COVID‐19 pandemic and total QMNC index by region of childbirth (Supporting Information Table S8). Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores regions are reported in this descriptive analysis, but results should be regarded only as exploratory findings due to the low sample size enrolled in these regions.

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using the WHO standards‐based quality measures to assess regional differences in perspectives of women about facility‐based QMNC around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Portugal. In all domains of the QMNC, large variations were observed across NUTS‐II regions, suggesting coexistence of both high‐quality care and substandard care. Inequities (i.e. avoidable differences) between NUTS‐II regions were clear. Even in the regions with the highest QMNC, some gaps were reported by a relevant proportion of women.

Our data confirm some previous findings, while bringing new evidence. The cesarean rate in our study (33.7%) is slightly lower than the 36.3% rate reported by PORDATA for the year 2020 25 (to date, data for the year 2021 have not been published) and slightly higher than the rate reported in the latest EURO PERISTAT report (32.9%). 26 The IVB rate in our study (23.8%) is slightly higher than that reported by PORDATA (18.8% for the year 2020), but not far from findings (21% from March 2020 to October 2021) reported by the Portuguese Consortium of Obstetric Data (Consórcio Português de Dados Obstétricos) 27 that gathers information exclusively from 13 public facilities in the North, Center, and Lisbon regions. The observed rate of episiotomies in noninstrumental vaginal birth is significantly higher in our study than those reported by the Portuguese Consortium of Obstetric Data (39.3% vs 26%), even when looking to our data exclusively from the North, Center, and Lisbon regions combined (37.8% vs 26%), which may be due to different characteristics of responders and different data collection methods (method not disclosed by the Portuguese Consortium of Obstetric Data). 28 In Portugal, national official data on rates of episiotomies are not available.

Examples of high‐quality care included low frequencies of lack of early breastfeeding and rooming‐in, and informal payment, and high frequencies of adequate staff professionalism, room comfort, and equipment. However, the huge disparities observed across regions in substandard practices of maternal care (e.g. IVB, episiotomy, fundal pressure) highlight significant local disparities in obstetric practices and the need to monitor obstetric data in all regions. As pointed out by WHO and by other studies, 29 unnecessary medicalization and use of nonevidence‐based interventions are common in high‐income countries, but variation within countries exists 30 and may be due to cultural reasons rather than clinical ones. 31 This excessive medicalization may compromise a woman's ability to have a physiological birth and has a negative impact on the overall childbirth experience. 32 Recently, governmental recommendations were made to conduct anonymous studies and “…eliminate violent obstetric practices such as fundal pressure…” in Portugal. 19 However, official national data regarding the use of fundal pressure are lacking, which is concerning given the number of women in our study who reported that they had been subjected to this unrecommended and potentially harmful practice. 32

Disparities between NUTS‐II regions were also clear concerning restrictions on companionship and key practices of newborn care, such as skin‐to‐skin contact, breastfeeding support, and exclusive breastfeeding at discharge. These specific aspects may have been affected by COVID‐19 prevention measures and conflicting recommendations. The guidelines of the DGS (2020) 13 were revised in October 2020 and were to be followed by Portuguese healthcare facilities 15 ; however, there was flexibility for institutional decisions according to the available resources and each woman's wishes, which may be the cause of such variations across regions in these specific quality measures.

Respectful and woman‐centered care implies, among other aspects, maintaining a woman's dignity. 16 However, our data show that an important proportion of women felt that they were not treated with dignity or were victims of emotional/physical/verbal abuse, with large variations between regions. The lowest rates were reported in Azores and North regions whereas the highest rates were reported in Center regions. These were also the regions with the highest proportion of women reporting lack of emotional support. Negative subjective birth experiences, lack of support, as well as verbal and psychological abuse are important risk factors associated with post‐traumatic stress disorder following childbirth 33 , 34 , 35 that can last for months 36 and is associated with negative child outcomes, namely eating/sleeping difficulties. 37 Women suffering physical and psychological abuse during childbirth perceive themselves as being subjected to obstetric violence. 38 It is striking that in a high‐income country, such disrespectful care and abuse are still reported. Urgent action is needed to promote the rights of women, provide access to respectful and supportive care for all women, and to develop programs to improve QMNC with an emphasis on respectful care to prevent and eliminate disrespect and abuse during childbirth. 39

Continued monitoring of QMNC around the time of childbirth is important to understand if these difficulties persist beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic. Prioritization of healthcare facilities to promote better care and to support HCPs in delivering better care, as well as the development of well‐established plans and suitable strategies for low‐performance facilities, are fundamental to promote quality care and reduce inequities.

Concerning study strengths, this is the first study in Portugal using a standardized validated questionnaire to assess maternal and newborn care that included a set of 40 quality measures based on the WHO standards for improving QMNC in health facilities, 21 which allowed for the first time a comparison between NUTS‐II regions. Furthermore, the proportion of the sample (83.9%) for the three most populated regions (i.e. North, Center, Lisbon) corresponds to the proportion of the live births in those regions in the year 2020 and 2021. 24

A limitation of this study is that some regions are underrepresented; therefore, it is important to continue efforts to monitor women's perceptions of QMNC in all Portuguese regions to provide additional reports with increased sample representativity. It is also possible that the most motivated women to respond to the questionnaire were those unsatisfied with the quality of care provided during childbirth; however, this paper reports comparisons of women's perspectives on the QMNC around the time of childbirth across NUTS‐II regions in Portugal, and differences found in QMNC between regions are not likely to be attributable to women's motivations to participate since we do not expect that women's motivations to respond to the questionnaire varies between regions. In addition, overall, study participants had a relatively higher level of education compared with the general Portuguese population. Higher educational levels could be associated with better access to high QMNC but could also be associated with higher expectations compared with women with lower education. There is also an over‐representation of births in private facilities in our study (22.9%), given that in 2020, 17.1% of births in Portugal were in private facilities. 40 Further analysis comparing women's perceptions by COVID‐19 status and on the perceptions of HCPs regarding QMNC by region may allow better understanding of the factors causing inequities within the country.

In conclusion, for such a small country as Portugal, despite existing examples of high‐quality maternal and newborn care, huge inequities in access, disrespect, abuse, and QMNC highlight the importance of developing actions to promote women's rights and respectful woman‐centered care around the time of childbirth, and to reduce inequities.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RC, CB, and HD conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. IM conducted the analysis and interpretation of data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. CR, TS, BC, EPV, and ML contributed to the study design, data acquisition, and curation, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

None to declare.

IMAgiNE EURO STUDY GROUP

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Amira Ćerimagić, NGO Baby Steps, Sarajevo; Croatia: Daniela Drandić, Roda – Parents in Action, Zagreb; Magdalena Kurbanović, Faculty of Health Studies, University of Rijeka, Rijeka; France: Rozée Virginie, Elise de La Rochebrochard, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Research Unit, Institut National d’Études Démographiques (INED), Paris; Kristina Löfgren, Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative (IHAB); Germany: Céline Miani, Stephanie Batram‐Zantvoort, Lisa Wandschneider, Department of Epidemiology and International Public Health, School of Public Health, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld; Italy: Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Benedetta Covi, Ilaria Mariani, Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste; Sandra Morano, Medical School and Midwifery School, Genoa University, Genoa; Israel: Ilana Chertok, Ohio University, School of Nursing, Athens, Ohio, USA and Ruppin Academic Center, Department of Nursing, Emek Hefer; Rada Artzi‐Medvedik, Department of Nursing, The Recanati School for Community Health Professions, Faculty of Health Sciences at Ben‐Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev; Latvia: Elizabete Pumpure, Dace Rezeberga, Gita Jansone‐Šantare, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Riga Stradins University and Riga Maternity Hospital, Riga; Dārta Jakovicka, Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Rīga; Agnija Vaska, Riga Maternity Hospital, Riga; Anna Regīna Knoka, Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Rīga; Katrīna Paula Vilcāne, Faculty of Public Health and Social Welfare, Riga Stradins University, Riga; Lithuania: Alina Liepinaitienė, Andželika Kondrakova, Kaunas University of Applied Sciences, Kaunas; Marija Mizgaitienė, Simona Juciūtė, Kaunas Hospital of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas; Luxembourg: Maryse Arendt, Professional Association of Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg; Barbara Tasch, Professional Association of Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, KannerKlinik, Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg, Luxembourg; Norway: Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, Sigrun Kongslien, Department of Community Medicine, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø; Eline Skirnisdottir Vik, Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen; Poland: Barbara Baranowska, Urszula Tataj‐Puzyna, Maria Węgrzynowska, Department of Midwifery, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw; Portugal: Raquel Costa, EPIUnit ‐ Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto; Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional, Porto; Lusófona University/HEI‐Lab: Digital Human‐environment Interaction Labs, Lisbon; Catarina Barata, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa; Teresa Santos, Universidade Europeia, Lisboa and Plataforma CatólicaMed/Centro de Investigação Interdisciplinar em Saúde (CIIS) da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon; Carina Rodrigues, EPIUnit ‐ Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto and Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional, Porto; Heloísa Dias, Regional Health Administration of the Algarve; Romania: Marina Ruxandra Otelea, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest and SAMAS Association, Bucharest; Serbia: Jelena Radetić, Jovana Ružičić, Centar za mame, Belgrade; Slovenia: Zalka Drglin, Barbara Mihevc Ponikvar, Anja Bohinec, National Institute of Public Health, Ljubljana; Spain: Serena Brigidi, Department of Anthropology, Philosophy and Social Work, Medical Anthropology Research Center (MARC), Rovira i Virgili University (URV), Tarragona; Lara Martín Castañeda, Institut Català de la Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya; Sweden: Helen Elden, Verena Sengpiel, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg; Karolina Linden, Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg; Mehreen Zaigham, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institution of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Lund and Skåne University Hospital, Malmö; Switzerland: Claire de Labrusse, Alessia Abderhalden, Anouck Pfund, Harriet Thorn, School of Health Sciences (HESAV), HES‐SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Lausanne; Susanne Grylka‐Baeschlin, Michael Gemperle, Antonia N. Mueller, Research Institute of Midwifery, School of Health Sciences, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur.

DISCLAIMER

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Rome ‐ Italy, in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste ‐ Italy. This study was supported by Portuguese fundings through FCT ‐ Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP, in the scope of the projects EPIUnit ‐ UIDB/04750/2020, ITR ‐ LA/P/0064/2020, and HEILab ‐ UIDB/05380/2020, and by the European Social Fund (ESF) and FCT (SFRH/BPD/117597/2016; RC postdoctoral fellowship). We are grateful to the women who dedicated their time to complete the survey, to Associação Portuguesa pelos Direitos da Mulher na Gravidez e Parto (APDMGP) for support with survey dissemination and to nurse Louise Semião for assistance provided in back‐translation of the questionnaires. Special thanks to the IMAgiNE EURO study group for their contribution to the development of this project and support for this manuscript.

Costa R, Barata C, Dias H, et al. Regional differences in the quality of maternal and neonatal care during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Portugal: Results from the IMAgiNE EURO study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;159(Suppl. 1):137‐153. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14507

Funding informationIMAgiNE EURO project was supported by the Ministry of Health, Rome ‐ Italy, in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste ‐ Italy. This study was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia; European Social Fund (ESF)

Contributor Information

Raquel Costa, Email: raquel.costa@ispup.up.pt.

IMAgiNE EURO study group:

Amira Ćerimagić, Daniela Drandić, Magdalena Kurbanović, Rozée Virginie, Elise de La Rochebrochard, Kristina Löfgren, Céline Miani, Stephanie Batram‐Zantvoort, Lisa Wandschneider, Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Benedetta Covi, Ilaria Mariani, Sandra Morano, Ilana Chertok, Emek Hefer, Rada Artzi‐Medvedik, Elizabete Pumpure, Dace Rezeberga, Gita Jansone‐Šantare, Dārta Jakovicka, Anna Regīna Knoka, Katrīna Paula Vilcāne, Alina Liepinaitienė, Andželika Kondrakova, Marija Mizgaitienė, Simona Juciūtė, Maryse Arendt, Barbara Tasch, Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, Sigrun Kongslien, Eline Skirnisdottir Vik, Barbara Baranowska, Urszula Tataj‐Puzyna, Maria Węgrzynowska, Raquel Costa, Catarina Barata, Teresa Santos, Carina Rodrigues, Heloísa Dias, Marina Ruxandra Otelea, Jelena Radetić, Jovana Ružičić, Zalka Drglin, Barbara Mihevc Ponikvar, Anja Bohinec, Serena Brigidi, Lara Martín Castañeda, Helen Elden, Verena Sengpiel, Karolina Linden, Mehreen Zaigham, Claire De Labrusse, Alessia Abderhalden, Anouck Pfund, Harriet Thorn, Susanne Grylka, Michael Gemperle, and Antonia Mueller

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kc A, Gurung R, Kinney MV, et al. Effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1273‐e1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khalil A, von Dadelszen P, Draycott T, Ugwumadu A, O'Brien P, Magee L. Change in the incidence of stillbirth and preterm delivery during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324:705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khalil A, von Dadelszen P, Ugwumadu A, Draycott T, Magee LA. Effect of COVID‐19 on maternal and neonatal services. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wastnedge EAN, Reynolds RM, van Boeckel SR, et al. Pregnancy and COVID‐19. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:303‐318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . Regional Office for Europe. Mitigating the Impacts of COVID‐19 on Maternal and Child Health Services: Copenhagen, Denmark, 8 February 2021: Meeting Report. WHO. Regional Office for Europe; 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/342056. Accessed March 25, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu S, Dzakpasu S, Nelson C, et al. Pregnancy outcomes during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Canada, march to august 2020. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2021;43:1406‐1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poon LC, Yang H, Kapur A, et al. Global interim guidance on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) during pregnancy and puerperium from FIGO and allied partners: information for healthcare professionals. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;149:273‐286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) . Guidance for Antenatal and Postnatal Services in the Evolving Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic, Version 2.2. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists, 24 April; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9. United Nations Population Fund . COVID‐19 technical brief for maternity services, update 2. UNFPA; 2020. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource‐pdf/COVID‐19_Maternity_Services_TB_Package_UPDATE_2_14072020_SBZ.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- 10. Narang K, Ibirogba ER, Elrefaei A, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 in pregnancy: a comprehensive summary of current guidelines. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pavlidis P, Eddy K, Phung L, et al. Clinical guidelines for caring for women with COVID‐19 during pregnancy, childbirth and the immediate postpartum period. Women Birth. 2021;34:455‐464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ross‐Davie M, Brodrick A, Randall W, Kerrigan A, McSherry M. 2. Labour and birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;73:91‐103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Direção Geral da Saúde (DGS) . Orientação n.° 018/2020 de 30/03/2020 [Orientation number 018/2020 from 30/03/2020]. DGS. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Direção Geral da Saúde (DGS) . Orientação n° 026/2020 de 19/05/2020 [Orientation number 026/2020 from 19/05/2020]. DGS. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Direção Geral da Saúde (DGS) . Orientação n.° 018/2020 de 30/03/2020 atualizada a 27/10/2020 [Orientation number 018/2020 from 30/03/2020 update on 27/10/2020]. DGS. https://www.dgs.pt/normas‐orientacoes‐e‐informacoes/orientacoes‐e‐circulares‐informativas/orientacao‐n‐0182020‐de‐30032020‐pdf.aspx. Accessed January 20, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization . Clinical Management of COVID‐19: Interim Guidance. WHO; 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332196. Accessed January 26, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. Quality of facility‐based maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic: online survey investigating maternal perspectives in 12 countries of the WHO European region. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;13:100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. EUROSTAT . NUTS ‐ Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics. 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/background. Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 19. Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.° 181/2021, publicada em Diário da República no dia 28 de junho de 2021, que recomenda ao Governo a eliminação de práticas de violência obstétrica e a realização de um estudo sobre as mesmas. Resolução da Assembleia da República n.° 181/2021. Assembleia da República. [Google Scholar]

- 20. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453‐1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization . Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. WHO; 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511216. Accessed September 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koenker R. Quantile Regression. Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. https://www.R‐project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 24. PORDATA [website]. https://www.pordata.pt/en/Municipalities/Live+births+of+mothers+resident+in+Portugal+total+and+by+sex‐103. Accessed February 22, 2022.

- 25. PORDATA [website] . Cesarianas nos hospitais (%). Qual a percentagem de cesarianas no total dos partos feitos nas unidades hospitalares? [Cesareans in hospital facilities. What is the percentage of cesarean in the total births at hospital facilities?] Data updated on 19/04/2022. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 26. Euro‐Peristat Project . European Perinatal Health Report. Core indicators of the health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2015. November 2018. www.europeristat.com. Accessed March 23, 2022.

- 27. Consórcio Português de Dados Obstétricos [Portuguese Consortium of Obstetric data]. https://cpdo.virtualcare.pt/. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 28. Lazzerini M, Costa R, Mariani I, et al. Science and beyond science in the reporting of quality of facility‐based maternal and newborn care during the COVID‐19 pandemic‐Authors' reply. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;20:100488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miani C, Wandschneider L, Batram‐Zantvoort S, et al. Individual and country‐level variables associated with the medicalization of birth. Eur J Public Health. 2022;32(Suppl 3):ckac129.191. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence‐based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2176‐2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lancet T. Stemming the global caesarean section epidemic. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization . WHO recommendations. Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Transforming care of women and babies for improved health and well‐being. WHO; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272447/WHO‐RHR‐18.12‐eng.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ayers S, Bond R, Bertullies S, Wijma K. The aetiology of post‐traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta‐analysis and theoretical framework. Psychol Med. 2016;46:1121‐1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Halperin O, Sarid O, Cwikel J. The influence of childbirth experiences on women's postpartum traumatic stress symptoms: a comparison between Israeli Jewish and Arab women. Midwifery. 2015;31:625‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martinez‐Vázquez S, Rodríguez‐Almagro J, Hernández‐Martínez A, Martínez‐Galiano JM. Factors associated with postpartum post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following obstetric violence: a cross‐sectional study. J Pers Med. 2021;11:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Martínez‐Vázquez S, Rodríguez‐Almagro J, Hernández‐Martínez A, Delgado‐Rodríguez M, Martínez‐Galiano JM. Long‐term high risk of postpartum post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and associated factors. J Clin Med. 2021;10:488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cook N, Ayers S, Horsch A. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder during the perinatal period and child outcomes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:18‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Annborn A, Finnbogadóttir HR. Obstetric violence a qualitative interview study. Midwifery. 2022;105:103212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. World Health Organization . The Prevention and Elimination of Disrespect and Abuse during Facility‐Based Childbirth. WHO; 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/134588/WHO_RHR_14.23_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed January 26, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 40. PORDATA [website] . Partos nos hospitais privados: total e por tipo. [Childbirth in private hospitals: total and by type]. https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/partos+nos+hospitais+privados+total+e+por+tipo‐1561‐67759. Data updated on 13/12/2021. Accessed March 23, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.