Abstract

Vaccines have had a tremendous impact on reducing the burden of infectious diseases; however, they have the potential to cause adverse events following immunization (AEFIs). Prelicensure clinical trials are limited in their ability to detect rare AEFIs that may occur in less than one per thousand individuals. While postmarketing surveillance systems have shown COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines to be safe, they led to the identification of rare cases of myocarditis and pericarditis after COVID‐19 vaccination that were not initially detected in clinical trials. In this narrative review, we highlight concepts of vaccine pharmacovigilance during mass vaccination campaigns and compare the approaches used in the context of myocarditis and pericarditis following COVID‐19 vaccination to historical examples. We describe mechanisms of passive and active surveillance, their strengths and limitations, and how they interacted to identify and characterize the safety signal of myocarditis and pericarditis after COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination. Articles were synthesized from a PubMed search using relevant keywords for articles published on vaccine surveillance systems and myocarditis and pericarditis after COVID‐19 vaccination, as well as the authors' collections of relevant publications and grey literature reports. The global experience around the identification and monitoring of myocarditis and pericarditis after COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination has provided important lessons for vaccine safety surveillance and highlighted its importance in maintaining public trust in mass vaccination programmes in a pandemic context.

Keywords: COVID‐19 vaccines, myocarditis, pericarditis, surveillance, vaccine pharmacovigilance, vaccine safety

1. INTRODUCTION

Vaccines have had a tremendous impact on reducing the burden of infectious diseases worldwide and are considered one of the greatest public health achievements. 1 However, similar to any biological product or health intervention, vaccines have the potential to cause adverse events. 1 While the safety of vaccines is carefully monitored in preclinical and prelicensure clinical trials (Phase 1, 2 and 3 studies), these are limited in their ability to detect adverse events following immunization (AEFIs) that may occur in less than one in a few thousand vaccinated individuals. 1 , 2 , 3 Thus, careful monitoring for rare but potentially serious AEFIs is required for vaccines that are authorized and used in the general population via postmarketing surveillance and Phase 4 studies. 3

Experience with previous mass vaccination programmes led to the implementation of multiple mechanisms to monitor for potential safety signals. 4 The detection of potential AEFIs that have arisen during routine or mass vaccination campaigns led to the development of passive and active vaccine surveillance systems that were leveraged and enhanced for AEFI monitoring of COVID‐19 vaccines. 4 , 5 While these surveillance systems have shown COVID‐19 vaccines to be safe, they have also led to the identification of rare AEFIs that were not identified in prelicensure clinical trials, such as thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome following adenoviral vector COVID‐19 vaccines, and myocarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines. 6 , 7

This narrative review focuses on events of myocarditis and pericarditis that occurred after COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines, given the extensive use of this platform worldwide and the significant impact of this AEFI on COVID‐19 vaccine campaigns and vaccine acceptance, especially in the highest risk groups. Historical examples that led to the strengthening of vaccine surveillance systems are also provided with a description on how they were leveraged in the context of the worldwide COVID‐19 mass vaccination campaign, allowing for the identification and characterization of the myocarditis and pericarditis signal. Finally, important lessons learned from this experience for global vaccine pharmacovigilance and surveillance systems are highlighted.

2. SEARCH STRATEGIES AND METHODS

A search of PubMed was conducted on 18 July 2022 for literature published up to that date in English on myocarditis and pericarditis after COVID‐19 vaccination and vaccine surveillance systems. The PubMed search strategies combined free‐text terms and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for each key concept. The detailed search strategies are shown in Appendix S1. Bibliographic records were exported from the electronic databases to an EndNote X9 (Clavirate Analytics) library.

A total of 1001 articles were found using the search strategies. Of these, 948 were excluded and 53 articles were deemed relevant for inclusion in the review by the authors based on their content. Articles that reported on animal studies or that did not pertain to vaccine safety (e.g., reported only on vaccine immunogenicity, effectiveness or cost‐effectiveness) were excluded. The authors also included an additional 67 studies and reports from personal collections of publications and grey literature reports that were deemed to be relevant for the purpose of the narrative review, ensuring that the selected articles were representative of various concepts of vaccine pharmacovigilance with illustrative examples. A total of 120 publications and reports were included in the review. The findings from the included studies were summarized using a narrative synthesis.

3. REVIEW

3.1. History and principles of vaccine pharmacovigilance

Pharmacovigilance, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), is the science and activities related to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug‐related problem. 8 Although principles of pharmacovigilance have been largely established after the recognition of adverse events occurring after receiving a medication, vaccine pharmacovigilance became an important branch of pharmacovigilance after the identification of unexpected, serious AEFIs that had sometimes tragic consequences. 9 An important difference between vaccines and other medications is that they are administered to large numbers of healthy individuals and therefore public, healthcare provider and regulatory expectations for their safety are high. 3

The minimal capacity for vaccine safety surveillance has been defined in the WHO Global Vaccine Safety Blueprint as a vaccine safety monitoring system that includes: (1) a national dedicated vaccine pharmacovigilance capacity; (2) a national database or system for collating, managing and retrieving AEFI reports; and (3) a national AEFI review committee to provide technical assistance on causality assessment of serious AEFIs. 10 Safety concerns that have been identified by such systems during previous mass vaccination campaigns have significantly influenced the monitoring of AEFI and principles of vaccines pharmacovigilance. 9

In this first section of the review, regulatory mechanisms, signal detection and surveillance systems, causality assessment and international case definitions are discussed using illustrative examples of vaccine safety concerns that have previously been observed during mass vaccination campaigns.

3.1.1. Regulatory mechanisms

One high‐profile vaccine safety crisis dates back to 1955, with the Cutter incident, when the American inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) programme led to 200 000 children receiving an incompletely inactivated vaccine (IPV). 11 , 12 After 40 000 vaccinees were diagnosed with poliomyelitis a defect was discovered in the process for inactivating the vaccine poliovirus strain at Cutter Laboratories. This incident left 200 children with varying degrees of paralysis and led to the deaths of 10 children. 11 , 12 One of the legacies of this tragic incident was the development and implementation of international standards for manufacture of pharmaceuticals termed good manufacturing practice (GMP). GMP aims to ensure consistency in the quality, safety and activity of pharmaceuticals and governs all stages of manufacture. 13 It has been generally accepted that had these practices been implemented for vaccine manufacture prior to the development of poliomyelitis vaccines, the Cutter incident could have been avoided. 12 To this day, regulatory mechanisms such as GMP, good laboratory practices (GLPs), which govern preclinical studies, and good clinical practices (GCPs), which govern clinical trial practices, remain important international standards in development and production of safe and effective vaccines. 14 These existing manufacturing processes and legacy systems ensured the effectiveness, precision and consistency of COVID‐19 vaccines upon mass production. 15 , 16

3.1.2. Signal detection and passive surveillance systems

Passive surveillance relies on spontaneous reporting of AEFIs from manufacturers, healthcare providers and the public. In 1976, a national vaccination campaign against swine influenza (influenza A/New Jersey/76) was initiated in the United States, during which over 45 000 000 doses of vaccines were administered. A passive nationwide surveillance programme was initiated for the mass campaign that within 2 months had identified clusters of reports of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) following vaccination. 17 Subsequent investigation undertaken by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uncovered 1098 individuals who had developed GBS during the initial phase of the vaccination campaign, of whom 532 individuals had received the vaccine. 17 , 18 Most individuals developed GBS within 6 to 8 weeks after vaccination, with a peak occurring during the third week. 17 , 18 The detection of the GBS signal led to the suspension of the vaccination programme and the subsequent creation of the first vaccination surveillance system in the United States, the Monitoring System for Adverse Events Following Immunization (MSAEFI). Through the MSAEFI, forms were given to vaccinees or their caregivers instructing them to report any illness requiring medical attention that occurred within 4 weeks of vaccination, which were then reviewed and forwarded to the CDC for data entry and analysis. 19

In response to alleged occurrences of acute neurological illnesses after whole‐cell pertussis‐containing vaccines, the US National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (NCVIA) of 1988 was adopted, which stipulated that healthcare professionals were required to report the occurrence of any AEFI. 20 Although an association between whole‐cell pertussis vaccines and febrile seizures was ultimately confirmed, subsequent studies did not confirm a causal relationship between pertussis vaccination and chronic neurological illness or epilepsy. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 The NCVIA then led to the implementation of the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) in 1990, replacing the MSAEFI as the main US passive surveillance system. In the United Kingdom, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) implemented the Yellow Card Scheme in 1964, following the thalidomide tragedy. 27 This database employs a similar reporting system to VAERS, with safety concerns involving any healthcare product being reported by individuals or healthcare providers, and it has been employed for the surveillance of AEFIs. 28

Passive surveillance systems are a primary pillar for AEFI signal detection because they are cost‐effective and broad reaching with the potential to identify novel safety concerns as adverse events need not be prespecified. 10 According to the WHO Global Vaccine Safety Blueprint, most countries rely on passive AEFI surveillance systems, which are often managed by national public health organizations. Between 2010 and 2019, countries with AEFI review committees increased from 94 (48.5%) to 129 (66.5%) of 194, and those reporting ≥10 AEFI per 100 000 infants increased from 80 (41.2%) to 109 (56.2%). 29 Despite these advances, further capacity building and enhancement around vaccine pharmacovigilance is needed in many low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). 10 In addition to national passive surveillance systems, the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) is a WHO collaborating centre for international drug monitoring that includes the integration of global data on AEFIs, facilitating the sharing of information, and harmonizing reporting. 1

Vaccine safety signals are often identified initially through passive surveillance systems based on comparison of observed reporting rates to expected population background rates irrespective of vaccination and disproportionality analyses identifying higher reporting rates of a specific AEFI–vaccine combination compared to reporting rates for the same AEFI after other vaccines. 30 The strength of dependency between a vaccine and an AEFI can be defined by a logarithmic measure of disproportionality, called the information component. 31 This epidemiological association is paramount to the eventual establishment of causality between an observed AEFI and the vaccine administered and highlights the importance of reporting AEFIs with established, routine vaccines, as well as newer products. 30 Analyses of passive surveillance data need to account for variability in sensitivity of reporting and sources of reporting bias, including both underreporting (particularly for nonserious or nonspecific expected AEFIs with established vaccines) as well as stimulated reporting when a safety concern draws media attention or leads to a change in the vaccine product information. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35

3.1.3. Active surveillance

Due to the limitations of passive surveillance systems outlined above as well as a need to confirm the strength of the epidemiologic association, data from active surveillance systems are often used to confirm and further evaluate safety signals identified via passive surveillance. 3 Active surveillance systems aim to identify all individuals within a defined population that may have developed the AEFI of interest and confirm their vaccination status. Approaches to active surveillance include review of health data recorded for patient care or health insurance purposes to identify cases or collection of data from vaccinees directly. Such systems may be population‐based or involve sentinel surveillance of defined subpopulations that are representative of the general population. 3 Active mechanisms can correct for reporting bias and underreporting seen with passive surveillance systems and enable adjustment for background rates of adverse events (AEs) of interest by comparing incidence of the AE in vaccinated vs. unvaccinated individuals from a representative population or using case‐only methods, such as the self‐controlled case series method to compare relative risk of the AE in the postvaccination period vs. a baseline period. 36 Thus, data from population‐based and sentinel surveillance systems can be used to determine whether an association exists between an exposure (vaccination) and an AEFI. 1

In the United States, the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), a joint project of the CDC and healthcare organizations established in 1990, uses ongoing searches of data from these organizations that capture exposures (i.e., vaccinations) and health outcomes of interest to conduct almost real‐time safety monitoring of vaccines using rapid cycle analyses and case‐only approaches like the self‐controlled case series design. 4 This system allowed the identification of a risk difference in febrile seizures occurring in children aged 6–59 months after receiving a specific brand of the influenza vaccine (Fluvax®, CSL Biologics), although the risk was highest in children receiving concomitant pneumococcal vaccines. 37 , 38 In Australia, recommendations were made in 2010 to strengthen the national vaccine adverse event reporting system following the identification of this unexpected signal. 3 Following these recommendations, the AusVaxSafety system was implemented, which includes an active, participant‐based safety surveillance system. Through the AusVaxSafety active surveillance system, parents of children receiving a vaccine in participating vaccination clinics are enrolled to receive either a Short Message Service (SMS) message and/or email to report whether there were any new health events within 3 days of vaccination and if so, to complete a short survey. 39 This surveillance system subsequently revealed low rates of fever and seizures after influenza vaccines, with most cases occurring in individuals with a prior history of seizures. 39

Another form of active surveillance is hospital‐based sentinel surveillance, which involves surveillance of individuals who present to hospital with certain health outcomes of interest. In Canada, following the detection of cases of aseptic meningitis following vaccination with the Urabe mumps vaccine strain in 1986–1988, the Immunization Monitoring Program ACTive (IMPACT) was established as a pilot study in five sites in 1991. 40 IMPACT is a paediatric hospital‐based national active surveillance network that now involves 13 Canadian centres and gathers information on children admitted to paediatric hospitals with conditions that could be AEFIs using trained surveillance nurses supervised by volunteer paediatric infectious diseases physicians acting as site investigators. 41 The model of hospital‐based active surveillance established by IMPACT has since been adapted and implemented in many countries, including Australia (Paediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance System, PAEDS) and Singapore (active hospital surveillance by the Vigilance Branch of the Health Science Authority). 42 Such active mechanisms are of specific importance for the identification of AEFIs that may arise during mass vaccination campaigns and have been especially valuable during the COVID‐19 vaccine rollout. For instance, IMPACT added specific COVID‐19‐relevant targets, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C), due to theoretical concern that vaccination might trigger a similar inflammatory response as SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, and myocarditis, after it emerged as a signal in passive surveillance systems. 41

3.2. COVID‐19 vaccine‐related myocarditis and pericarditis

Vaccination has played an essential role in mitigating the health burden of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 43 While COVID‐19 vaccines were assessed for safety during Phase 1, 2 and 3 clinical trials, ensuring adequate and enhanced postmarketing surveillance of AEFI in the general population has been of utmost importance to maintain trust in the vaccination campaign. With 21 720 and 15 210 participants having been vaccinated in Phase 3 clinical trials from Pfizer and Moderna, respectively, no cases of myocarditis or pericarditis were initially identified following vaccination. 44 , 45

In this section of the review, we discuss the systems that identified and characterized the safety signal observed with occurrence of myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination, the clinical presentation of these cases, mitigation strategies that were implemented and the lessons learned from this experience for improving vaccine pharmacovigilance and safety monitoring systems for routine and pandemic vaccines moving forward.

3.2.1. Clinical presentation and case definitions

In March 2021, a series of six cases of myocarditis occurring within days following receipt of the BNT162b2 vaccine was reported via the passive surveillance system in Israel. 7 These cases generally presented with a mild illness, characterized by symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath and palpitations, mostly in younger men aged 16 to 30 years of age. Previous cardiac conditions, including prior episodes of pericarditis or myocarditis, were not identified as a significant risk factor, and most cases seemed to occur in individuals who were previously healthy. 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53

Myocarditis can present as different clinical syndromes that range from mild chest pain with transient ECG changes to heart failure and cardiogenic shock. 54 However, in up to 95% to 99% of cases, chest pain will be reported as the initial symptom, or in some instances, as the only presenting symptom. 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 The Brighton Collaboration, a consortium of vaccine safety experts focused on standardizing AEFI reporting globally, has developed and published case definitions for definitive (level of certainty 1), probable (level of certainty 2) and possible (level of certainty 3) myocarditis after COVID‐19 vaccination. 55 Patients with definitive myocarditis have abnormal imaging (echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance study) and elevated troponins or myocardial inflammation found at endomyocardial biopsy, whereas patients with a probable case of myocarditis have symptoms of myocarditis with elevated troponins or abnormal heart imaging, or electrocardiogram (ECG) showing features of myocarditis. 55 Patients with possible myocarditis have clinical symptoms of myocarditis with elevated biomarkers supporting evidence of inflammation (elevated C‐reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or D‐dimer) or ECG abnormalities with no alternative diagnosis for the presenting symptoms. 55

The clinical presentation of pericarditis may be similar to that of myocarditis. The Brighton Collaboration also developed case definitions for definitive (level of certainty 1), probable (level of certainty 2) and possible (level of certainty 3) pericarditis, informed by the definitions established by the European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology Guidelines for Pericardial Disease. 55 , 56 Patients with definitive pericarditis have abnormal imaging (echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance study), ECG abnormalities (e.g., ST‐segment elevation) or physical signs (e.g., pericardial friction rub) suggestive of pericarditis. 55 Patients with a probable case of pericarditis have cardiac symptoms that include chest pain with one physical examination finding or one finding on ECG or cardiac imaging. 55 A possible case of pericarditis is based on symptoms with abnormal chest radiogram showing enlarged heart or nonspecific ECG abnormalities, in the absence of an alternative diagnosis. 55 The CDC has also established working case definitions for both acute myocarditis and pericarditis that overlap with the Brighton Collaboration definitions and which have been mostly used for case ascertainment in the United States. The main difference between these two definitions pertains to the confirmation of the diagnosis, with the CDC criteria requiring a cardiac MRI or myocardial biopsy for a case to be confirmed as opposed to probable. 57 Myocarditis and pericarditis may overlap in clinical practice, and cases whose presentation meets both the myocarditis and pericarditis definitions may be termed myopericarditis cases.

Reassuringly, detailed clinical reports have now shown that patients with pericarditis, myocarditis or myopericarditis typically experience a mild course of illness and improve quickly in response to conservative treatment and rest. 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 Some studies have also reported that at follow‐up up to 3 months after the initial episode of myocarditis or pericarditis after COVID‐19 vaccination, the majority of patients had no ongoing symptoms or abnormal cardiac investigations. 51 , 58 However, in some reports, a subset of patients have persistent late gadolinium enhancement pattern in their cardiac MRI up to 237 days after vaccination; the prognostic significance of this finding remains uncertain. 59 , 60 These studies and case series highlight the importance of long‐term follow‐up for patients who have experienced myocarditis after COVID‐19 vaccination to better understand the trajectory of this condition, particularly with subsequent SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or COVID‐19 vaccination.

3.2.2. Signal detection and causality

The key findings and actions taken on the postvaccine myocarditis and pericarditis signal are presented in Table 1 for select passive surveillance systems and Table 2 for select active surveillance systems. A timeline of select key events of the COVID‐19 vaccine rollout and detection of the myocarditis and pericarditis signal is presented in Figure 1. Several factors from previous vaccine pharmacovigilance experience converged to enable rapid identification and characterization of the myocarditis/pericarditis safety signal with COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines to inform public health and regulatory action. First, vaccine safety and public health experts anticipated that vaccine safety signals that were not initially detected in clinical trials may arise upon the broad rollout of COVID‐19 vaccines and instituted measures to enhance passive and active surveillance and enable rapid reporting of surveillance results. Such measures included the development of case definitions and tools for reporting AEFIs, estimating background rates of conditions that could be AEFIs and establishing regular online reporting of safety data. 28 , 67 , 82 In 2020, the Brighton Collaboration first developed a list of various potential adverse events of special interest (AESI) that should be monitored in a collaborative global effort. 83 AESI are events that have not previously been associated with COVID‐19 vaccines but warrant specific surveillance by regulators and public health authorities. 30 These initially included complications described with COVID‐19 and AEFIs previously associated with other vaccines; this list has been updated regularly. 83

TABLE 1.

Select passive surveillance platforms that have played a role in the detection of the post COVID‐19 vaccine myocarditis signal: key findings and actions taken

| Surveillance system | Region and year of implementation | Roles and/or key findings | Actions taken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Health monitoring and health administrative data | Israel 61 | Detection of the first cases of myocarditis in young males and clinical description; overall mild and resolved within a few days. 7 | Communications to NITAGs and regulators, triggering enhanced surveillance and detailing of the signal globally. |

| Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) | USA, 1990 19 , 35 | Early detection of the increased risk of myocarditis across multiple age and sex strata, highest after the second dose in adolescent males and young men. 51 | Review of the product by the FDA, discussion at ACIP (CDC), information disseminated to healthcare providers by the CDC. |

| EudraVigilance | Europe, 2001 62 | Early detection of cases and reports after all COVID‐19 vaccines, especially mRNA vaccines. 63 | Assessment of vaccine safety by the EMA safety committee (PRAC). |

| Yellow Card reporting scheme (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency) | UK, 1964 1 | Overall reporting rate across all age groups for suspected myocarditis of 10 reports per million doses of BNT162b2 and for suspected pericarditis, seven reports per million doses. 28 | Update to product information for mRNA‐1273 and BNT162b2 to inform healthcare professionals and patients and provide advice to be aware of important symptoms for myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination. |

| Canadian Adverse Events Following Immunization Surveillance System (CAEFISS) | Canada, 1987 2 | Integration of the databases and description of rate of 1.27 per 100 000 doses administered. Confirmed Ontario signal of higher rate of myopericarditis with mRNA‐1273 vs. BNT162b2. 64 , 65 |

Instituted enhanced surveillance for myocarditis. Data communicated to NACI, PHAC and HC. NACI statement and weekly AEFI reports updated with information about myopericarditis signal. |

| Public Health Ontario (PHO) passive surveillance of AEFI | Canada | In 18‐ to 29‐year‐old males, attributable risk of myocarditis/pericarditis higher among mRNA‐1273 vaccinees compared to BNT162b2 vaccinees, higher rate with dosing interval of ≤30 days. 32 | Initiated enhanced surveillance. NACI recommending preferential use of BNT162b2 vaccine over mRNA‐1273 vaccine in 18‐ to 29‐year‐old males with an 8‐week dosing interval. |

| Product Review of the Therapeutic and Goods Administration (TGA) | Australia 66 | Initial detection of 50 cases of suspected myocarditis and/or pericarditis in Australia. 67 | Addition of a warning statement to mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines product information and included myocarditis and pericarditis as an adverse event identified through postmarketing experience. |

| Surveillance of Adverse Events Following Vaccination in the Community (SAEFVIC) | Australia, 2007 66 | Detailed description of 75 cases of myocarditis in 12 to 17 year olds with an incidence of 8.3 per 100 000 doses. 68 | Communication to ATAGI. |

| Vigibase (Uppsala Monitoring Centre) | Global, 2001 29 , 69 | Disproportionate reporting of myocarditis observed in adolescents and in 18 to 29 year olds compared with older patients, as well as in male patients at a global level, however very rare risk overall. 70 | Review by GACVS and development of guidance on assessment and management of cases. |

Abbreviations: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; ATAGI, Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GACVS, Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety; HC, Health Canada; NACI, National Advisory Committee on Immunization; NITAGs, National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups; PHAC, Public Health Agency of Canada; PRAC, Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee.

TABLE 2.

Select active surveillance platforms that have played a role in the detection of the post COVID‐19 vaccine myocarditis signal: key findings and actions taken

| Surveillance system | Region and year of implementation | Roles and/or key findings | Actions taken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Health England | UK | Increased risks of myocarditis with the first dose of ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 vaccines and the first and second doses of the mRNA‐1273 vaccine in ≥16 year olds over the 1–28 days postvaccination period and after a SARS‐CoV‐2 positive test. 71 | Data communicated to the JCVI, consideration of risk and benefit balance of vaccination in adults and children. |

| Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) | USA, 1990 4 | Increased risk of myocarditis/pericarditis among individuals 12 to 39 years of age in the 7‐day risk interval after vaccination with mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines compared with unvaccinated individuals or individuals vaccinated with non‐mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines. 72 , 73 | Data presented to the CDC/ACIP and discussion on the risks and benefits of COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination in the identified groups. |

| V‐Safe (USA) | USA, 2020 74 | Detailed information on health impact, results often combined with VAERS data. 75 , 76 | Review of the product by the FDA, discussion at ACIP (CDC). |

| Immunization Monitoring Program, Active (IMPACT) | Canada, 1991 2 (Paediatric only) | Sentinel surveillance of myopericarditis occurring in children admitted to paediatric hospitals in Canada 42 initiated June 2021. 42 | AEFI reports submitted to CAEFISS for inclusion in national data. Activities communicated to PHAC and NACI. |

| Canadian National Vaccine Safety Network (CANVAS) | Canada, 2009 77 | Evaluation of the health burden of AEFI and comparison with unvaccinated control groups. 77 | Serious AEFIs reported to public health surveillance system. Data communicated to public health jurisdictions, PHAC, NACI and public. |

| Paediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance System (PAEDS) | Australia, 2007 78 | Surveillance of events (including myocarditis) occurring in children admitted to paediatric hospitals in Australia. 78 | Data communicated to ATAGI. |

| AusVaxSafety | Australia, 2010 79 , 80 | Publicly available data on more than 6 million vaccinees who have received health surveys sent on Day 3 post vaccination. Report of one to two cases of myocarditis or pericarditis per 100 000 vaccinees. 81 | Complement to TGA safety surveillance activities. |

Abbreviations: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; AEFI, adverse event following immunization; ATAGI, Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation; CAEFISS, Canadian Adverse Events Following Immunization Surveillance System; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; JCVI, Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation; NACI, National Advisory Committee on Immunization; PHAC, Public Health Agency of Canada; TGA, Therapeutic Goods Administration; VAERS, Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.

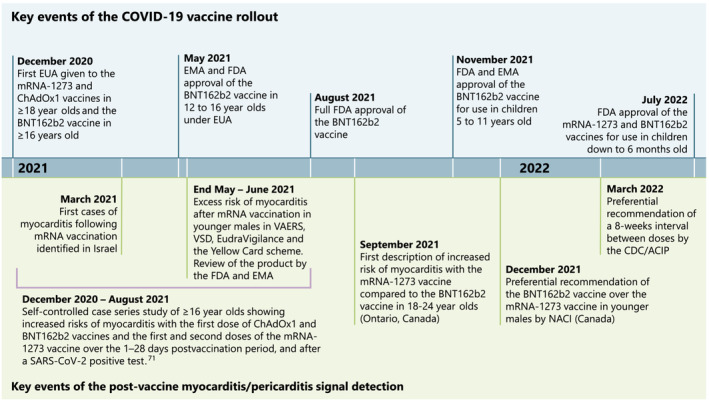

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of select key events of the COVID‐19 pandemic and COVID‐19 vaccine development, rollout and detection of postvaccine myocarditis and pericarditis. ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; AEFI, Adverse Event Following Immunization; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; EMA, European Medicines Agency; EUA, Emergency Use Authorization; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; NACI, National Advisory Committee on Immunization; VAERS, Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System; VSD, Vaccine Safety Datalink

Second, existing surveillance systems served as an early warning system. It should be acknowledged that timely recognition and reporting of myocarditis cases by astute clinicians was of particular importance. Cases were initially reported from Israel in March 2021, which then led to increased awareness for the detection of this condition, public health review of collated cases and public reporting of passive surveillance data. 7 Israeli surveillance systems alerted other clinicians, public health and regulators in other jurisdictions to the potential signal. 57 , 63 , 84 , 85 Awareness of the safety signal by these stakeholders stimulated further reporting, institution of enhanced surveillance measures, and analysis of data from passive and active surveillance programmes, which confirmed the increased risk of myocarditis and pericarditis following mRNA vaccines across multiple surveillance programmes and jurisdictions. 32 , 72 , 73 , 86 , 87 A study from Israel that employed health administrative data subsequently revealed an excess risk of myocarditis in vaccinees of three events per 100 000 individuals. 61 These findings were further supported by data from the US VAERS, US military surveillance and Canadian passive surveillance system that similarly found elevated reporting rates of myocarditis and pericarditis within 21 days following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination compared to expected background rates, with the highest rates reported within 7 days after vaccination and in males 12–39 years of age. 32 , 51 , 64 , 86

Active surveillance programmes later confirmed the signal. The VSD initially reported 34 cases of confirmed myocarditis and pericarditis in individuals 12 to 39 years old, of whom 85% were males. 4 , 72 Though there was no overall association between myocarditis/pericarditis within 21 days after any dose of COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination among 10 million vaccinees, the VSD did observe a significantly increased relative risk of myocarditis/pericarditis within 7 days after Dose 1 and Dose 2 (somewhat higher after Dose 2) corresponding to an excess of 6.3 cases per million vaccinees. 72 Updated data from the VSD until 31 May 2022 for persons 18–39 years of age and 20 August 2022 for persons 5–17 years of age, reported on a total of 320 cases of myocarditis and pericarditis in individuals 5 to 39 years old, corresponding to an approximate incidence of 1 per 200 000 first doses and 1 per 30 000 per second doses. 88 Most cases (61%) occurred 0 to 7 days after vaccination. 72 , 88 A study from Public Health England using administrative health data from over 37 million people from December 2020 to August 2021 also revealed increased risks of myocarditis with the first dose of ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 vaccines and the first and second doses of the mRNA‐1273 vaccine over the 1–28 days postvaccination period among individuals ≥16 years of age, though the risk of myocarditis associated with vaccination was significantly lower than the risk associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 71 Although cases of myocarditis following ChAdOx1, a viral vector‐based COVID‐19 vaccine, were also reported to EudraVigilance (passive surveillance system operated by the European Medicines Agency), the restricted use of this vaccine in multiple jurisdictions, particularly in young adults, owing to rare cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, has limited the evaluation of the strength of association between this vaccine and occurrences of myocarditis and pericarditis. 63

Criteria for causality assessment in individual cases have been established by both the US Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network and the WHO and include an established epidemiological association, confirming the diagnosis using standard case definitions, biological plausibility, temporality between the vaccine and the onset of the AEFI, occurrence of comparable events after a previous dose of the vaccine and the identification of potential alternate causes. 89 , 90 , 91 The strength and consistency of this epidemiological association has been paramount to confirming a causal relationship between the COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines and events of myocarditis and pericarditis within 7–28 days post vaccination, given the absence of established pathophysiological mechanisms. However, although myocarditis has been causally associated with first‐ and second‐generation smallpox vaccines, the pathogenesis of these events is thought to be due to a noninfectious inflammatory response to the live vaccinia virus, with a later onset post vaccination (4–30 days) than is being seen with mRNA vaccines. 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 Multiple pathophysiological mechanisms for myocarditis and pericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination have now been proposed, but its pathogenesis remains largely speculative, mostly given the overall mild clinical course and absence of histological evaluation through myocardial biopsy. 49 Proposed hypotheses have included immune‐mediated hyperinflammatory reaction to the antigen in predisposed individuals, antibody‐mediated hypersensitivity and molecular mimicry between SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein and an unknown myocardial protein. 49 , 55 , 95 , 97 Further, it is likely that significant differences in hormone signalling and T helper 1 cell‐mediated immune responses to mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines exist given the higher rates of myocarditis observed in males compared to females. 97 Additional studies are needed to better understand the underlying pathophysiology and long‐term outcomes of myocarditis and pericarditis following COVID‐19 vaccination.

3.2.3. Mitigation measures

Multiple reports and surveillance systems have shown that myocarditis and pericarditis is most frequent in younger males (16 to 29 years old) following the second dose of an mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine. 7 , 72 , 87 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 The use of different COVID‐19 vaccine platforms and products, different dosing intervals and heterologous schedules across countries with well‐developed vaccine surveillance systems created conditions that allowed for comparison of a variety of factors, enabling further characterization of this safety signal. For example, analysis of passive surveillance data from Ontario, Canada, demonstrated a significantly increased relative risk of myocarditis with mRNA‐1273 vs. BNT162b2 in young men, a finding later confirmed in passive and active surveillance programmes and epidemiologic cohort studies in several other countries (Tables 1 and 2). 32 , 64 , 71 , 72 , 86 , 103 This Ontario study also revealed that a shorter dosing interval (≤30 days) was associated with a higher rate of myocarditis or pericarditis than an extended interval of ≥56 days. 32 These data, confirmed in national passive surveillance, informed public health mitigation strategies. 64 Such mitigation strategies have included recommendation by national immunization expert advisory groups for preferential use of the BNT162b2 vaccine over the mRNA‐1273 vaccine in individuals under the age of 30 in Canada and several European countries, and an extended 8‐week interval between primary series doses in Canada and the United States. 104 , 105 Studies showing higher vaccine effectiveness with the 8‐week dosing interval over a 3‐ to 4‐week interval also informed the recommendation for the longer dosing interval. 104 , 105

Increased knowledge of the myocarditis and pericarditis signal informed immunization policy and surveillance when vaccines were authorized for younger age groups (<12 years of age), with jurisdictions undertaking close monitoring for myocarditis from the start of the programmes for those groups, as well as recommending the extended 8‐week interval. Another mitigation strategy includes the avoidance of revaccination with an mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine in individuals who have experienced confirmed myopericarditis without another identified cause following a prior dose of an mRNA vaccine. 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 However, in certain circumstances, such as in patients at high risk of severe COVID‐19 outcomes, people with confirmed myocarditis (with or without pericarditis) after a dose of an mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine may choose to receive another dose of vaccine after discussing the risks and benefits with their healthcare provider. 104 Further data are needed on the risk of myocarditis recurrence following future vaccination with COVID‐19 mRNA products and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, as well as safety of alternative products in individuals who have experienced confirmed myopericarditis from a prior dose of COVID‐19 mRNA vaccine to inform public health recommendations.

In many jurisdictions, regulatory bodies have approved COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination in children younger than 12 years of age, even as young as 6 months of age. 108 , 109 , 110 Across multiple clinical trials of paediatric doses of BNT162b2 and mRNA‐1273 involving children 6 months to 11 years of age, no events of myocarditis and pericarditis were detected. 109 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 Very low rates of myopericarditis have been observed in children aged 5–11 years of age, with reporting rates to VAERS of 2.5 and 0.7 cases per million doses among males and females, respectively, within 7 days of Dose 2 as of 21 August 2022 and incidence rates of 14.4 per million second doses among males (based on three cases) and 0 cases among females up to 20 August 2022. 115 Meanwhile, no cases of myopericarditis were reported to VAERS among children 6 to 59 months of age following administration of over 1.4 million doses of COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines from 18 June to 21 August 2022. 113 The low reporting rates seen in these age groups may be related to the fact that myocarditis secondary to causes other than COVID‐19 vaccination are less common compared to older children and adults as well as the lower doses used in the paediatric vaccine formulations. 98 , 110

3.2.4. Lessons learned

Although multiple surveillance systems from prior vaccine pharmacovigilance experience were leveraged for the identification and mitigation of the postvaccination myocarditis signal, significant gaps and potential areas for future improvement of these systems were also identified as described in Table 3. In particular, while clinicians were key to identifying the first cases of a possible signal, they may not be familiar with AEFI reporting and investigations procedures. Researchers are also often siloed within their existing networks, specialists within their specialties and public health within their jurisdictions. This can lead to both duplication of research efforts and lack of standardization in approach which can impede cross‐speciality and cross‐jurisdictional comparisons and potentially confuse communication efforts. 55 Earlier coordination and collaboration between public health and specialist clinical networks that would encounter affected patients (e.g., cardiology, emergency, family medicine and paediatrics) within and across jurisdictions may have helped to streamline efforts, improve communication, case reporting and standardize case management. Standard case definitions and guidelines for data collection are critical. The Brighton Collaboration did prioritize myocarditis and pericarditis when the signal was identified, though finalizing the case definitions took several months. 55 In addition, long‐term follow‐up of these cases is needed to document clinical course and monitor for late complications (e.g., arrhythmia). Such studies should be conducted in all countries where this signal was observed. 58

TABLE 3.

Roles and lessons learned from the experience with postvaccine myocarditis and pericarditis for select levels of vaccine pharmacovigilance entities and stakeholders

| Stakeholder or player | Roles | Lessons learned |

|---|---|---|

| Local/subnational | ||

| Individuals |

|

|

| Clinicians and healthcare providers |

|

|

| Local/regional public health |

|

|

| National | ||

| National public health organizations |

|

|

| NITAGs |

|

|

| Governments |

|

|

| Regulators |

|

|

| International and nongovernmental organizations | ||

| Manufacturers |

|

|

| Research funders |

|

|

| Researchers and global networks of specialists |

|

|

Abbreviations: AEFI, adverse event following immunization; GMP, good manufacturing practice; LMICs, low‐ and middle‐income countries; NITAGs, National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups.

Furthermore, few jurisdictions have programmes in place to systematically evaluate and follow up individuals who experience myocarditis and other potentially serious AEFIs in regard to the safety of future COVID‐19 vaccination and the risk of COVID‐19 complications following subsequent infections. With many public health jurisdictions recommending against future mRNA vaccinations in patients with confirmed myocarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination and limited access to alternative products, these patients remained suboptimally protected against severe COVID‐19. 99 , 101 , 104 , 106

Though countries using mRNA vaccines had access to data from multiple, complementary robust surveillance systems to inform the response to this signal, in LMICs with fewer resources or established surveillance programmes using non‐mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine products (e.g., inactivated vaccines) postmarket safety data remain limited to nonexistent. 116 Such gaps in evidence can undermine vaccine confidence while also hindering research into this safety signal, including confirming the specificity of myocarditis for the mRNA platform. Further augmentation of postmarket surveillance, including enhancing passive surveillance systems and increasing active surveillance approaches such as sentinel surveillance is needed to support vaccination programmes in LMICs settings.

To sustain and improve the effectiveness of the response to vaccine safety signals with COVID‐19 vaccination and future mass vaccination campaigns, existing programme capacity and expertise need to be sustained through inter‐pandemic periods at local, subnational, national and global levels. Clinicians need to maintain vigilance to potential AEFIs and have access to efficient mechanisms to report AEFIs promptly to the passive surveillance system. Safety surveillance programmes need to maintain capacity in data analysis and mechanisms for rapid communication of findings. Global coordination of case definitions, AEFI reporting, and surveillance algorithms needs to be further expanded and existing mechanisms sustained through continued funding support. For example, the Brighton Collaboration's Safety Platform for Emergency Vaccines (SPEAC) Project has created numerous resources and tools to support global standardization of COVID‐19 vaccine safety reporting while the Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) is coordinating safety evaluation of COVID‐19 vaccines, including assessing the association between myocarditis and mRNA vaccines using administrative data sources in 18 countries covering over 250 million people. 117 , 118 To further improve the safety of vaccines, global standing networks are needed to investigate patients with myocarditis and other AESIs to understand the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms and identify genetic risk factors to inform regulatory and public health risk–benefit assessment of vaccines and future vaccine development. The GVDN and International Network of Special Immunization Services (INSIS) aim to harness genomics and systems biology technologies to fill these critical knowledge gaps. 119 , 120 However, such initiatives require sustained funding to maintain readiness to respond to the next safety signal.

4. CONCLUSION

Experience with vaccine safety concerns that have arisen in previous mass vaccination campaigns led to the creation and enhancements of passive and active vaccine safety surveillance systems around the world. Enhancements to these systems in anticipation of the COVID‐19 vaccine campaign enabled the rapid identification of cases of myocarditis and pericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination and assessment of this safety signal. Vaccine safety signals will continue to occur with new and even existing vaccines. The COVID‐19 vaccination campaign has shone a spotlight on pharmacovigilance. Ensuring continued safety of COVID‐19 and vaccination programmes against other emerging infectious diseases, while supporting public confidence requires greater collaboration within and between jurisdictions as well as enhanced support for vaccine pharmacovigilance and vaccine safety research for all vaccines against pandemic and epidemic diseases.

COMPETING INTERESTS

P.P.P.R. has been a coinvestigator on an investigator‐led project that was funded by Pfizer, unrelated to this review. S.K.M. is coprincipal investigator on an investigator‐led grant from Pfizer, has served on ad hoc advisory boards for Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur and has received speaker fees from GlaxoSmithKline, all unrelated to this review.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting Information

Piché‐Renaud P‐P, Morris SK, Top KA. A narrative review of vaccine pharmacovigilance during mass vaccination campaigns: Focus on myocarditis and pericarditis after COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;1‐15. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15625

Funding information PPPR is supported by the Clinician‐Scientist Training Program and a Transplant and Regenerative Medicine Centre award from The Hospital for Sick Children.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety (GACVS); WHO secretariat . Global safety of vaccines: strengthening systems for monitoring, management and the role of GACVS. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8(6):705‐716. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacDonald NE, Law BJ. Canada's eight‐component vaccine safety system: a primer for health care workers. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22(4):e13‐e16. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crawford NW, Clothier H, Hodgson K, Selvaraj G, Easton ML, Buttery JP. Active surveillance for adverse events following immunization. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):265‐276. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.866895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McNeil MM, Gee J, Weintraub ES, et al. The Vaccine Safety Datalink: successes and challenges monitoring vaccine safety. Vaccine. 2014;32(42):5390‐5398. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salmon DA, Lambert PH, Nohynek HM, et al. Novel vaccine safety issues and areas that would benefit from further research. BMJ Glob. 2021;6(Suppl 2):e003814. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin TE, Weisser K, Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov‐19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(22):2092‐2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abu Mouch S, Roguin A, Hellou E, et al. Myocarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination. Vaccine. 2021;39(29):3790‐3793. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . What is Pharmacovigilance?. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/regulation-prequalification/regulation-and-safety/pharmacovigilance. Accessed June 12, 2022.

- 9. Anonymous . Global status of immunization safety: report based on the WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form, 2004 update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80(42):361‐367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Global Vaccine Safety Blueprint 2.0 (GVSB2.0) 2021‐2023. World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY‐NC‐SA 3.0 IGO [Google Scholar]

- 11. Offit PA. The cutter incident, 50 years later. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(14):1411‐1412. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fitzpatrick M. The cutter incident: how America's first polio vaccine led to a growing vaccine crisis. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(3):156. doi: 10.1177/014107680609900320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baylor NW, Marshall VB. Regulation and testing of vaccines. Vaccine. 2013;46(10):1‐4557. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4557-0090-5.00073-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Public Health Agency of Canada . Vaccine Safety and Pharmacovigilance: Canadian Immunization Guide [Internet]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-2-vaccine-safety/page-2-vaccine-safety.html#s2. Modified December 2019; accessed June 14, 2022.

- 15. Rosa SS, Prazeres DMF, Azevedo AM, Marques MPC. mRNA vaccines manufacturing: challenges and bottlenecks. Vaccine. 2021;39(16):2190‐2200. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang C, Maruggi G, Shan H, Li J. Advances in mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:594. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schonberger LB, Bregman DJ, Sullivan‐Bolyai JZ, et al. Guillain‐Barre syndrome following vaccination in the National Influenza Immunization Program, United States, 1976–1977. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(2):105‐123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurland LT, Wiederholt WC, Kirkpatrick JW, Potter HG, Armstrong P. Swine influenza vaccine and Guillain‐Barre syndrome. Epidemic or artifact? Arch Neurol. 1985;42(11):1089‐1090. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060100075026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosenthal S, Chen R. The reporting sensitivities of two passive surveillance systems for vaccine adverse events. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(12):1706‐1709. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.12.1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act: requirements for permanent vaccination records and for reporting of selected events after vaccination. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37(13):197‐200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cherry JD. ‘Pertussis vaccine encephalopathy’: it is time to recognize it as the myth that it is. JAMA. 1990;263(12):1679‐1680. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440120101046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Griffin MR, Ray WA, Mortimer EA, Fenichel GM, Schaffner W. Risk of seizures and encephalopathy after immunization with the diphtheria‐tetanus‐pertussis vaccine. JAMA. 1990;263(12):1641‐1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440120063038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller D, Wadsworth J, Diamond J, Ross E. Pertussis vaccine and whooping cough as risk factors in acute neurological illness and death in young children. Dev Biol Stand. 1985;61:389‐394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller DL, Ross EM, Alderslade R, Bellman MH, Rawson NS. Pertussis immunisation and serious acute neurological illness in children. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282(6276):1595‐1599. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6276.1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bellman MH, Ross EM, Miller DL. Infantile spasms and pertussis immunisation. Lancet. 1983;1(8332):1031‐1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92655-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barlow WE, Davis RL, Glasser JW, et al. The risk of seizures after receipt of whole‐cell pertussis or measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):656‐661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fornasier G, Francescon S, Leone R, Baldo P. An historical overview over pharmacovigilance. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;40(4):744‐747. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0657-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Medicines & Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency . Coronavirus vaccine—summary of Yellow Card reporting [Internet]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-adverse-reactions/coronavirus-vaccine-summary-of-yellow-card-reporting. Accessed July 17, 2022.

- 29. Salman O, Topf K, Chandler R, Conklin L. Progress in immunization safety monitoring—worldwide, 2010–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(15):547‐551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Black SB, Law B, Chen RT, et al. The critical role of background rates of possible adverse events in the assessment of COVID‐19 vaccine safety. Vaccine. 2021;39(19):2712‐2718. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bate A, Lindquist M, Edwards IR, Orre R. A data mining approach for signal detection and analysis. Drug Saf. 2002;25(6):393‐397. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225060-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buchan SA, Seo CY, Johnson C, et al. Epidemiology of myocarditis and pericarditis following mRNA vaccination by vaccine product, schedule, and interdose interval among adolescents and adults in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2218505. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.18505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McNeil MM, Li R, Pickering S, Real TM, Smith PJ, Pemberton MR. Who is unlikely to report adverse events after vaccinations to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS)? Vaccine. 2013;31(24):2673‐2679. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hua W, Izurieta HS, Slade B, et al. Kawasaki disease after vaccination: reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System 1990–2007. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(11):943‐947. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181a66471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen RT, Rastogi SC, Mullen JR, et al. The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Vaccine. 1994;12(6):542‐550. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(94)90315-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN, Farrington CP. The methodology of self‐controlled case series studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 2009;18(1):7‐26. doi: 10.1177/0962280208092342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tse A, Tseng HF, Greene SK, Vellozzi C, Lee GM, VSD Rapid Cycle Analysis Influenza Working Group . Signal identification and evaluation for risk of febrile seizures in children following trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Safety Datalink Project, 2010–2011. Vaccine. 2012;30(11):2024‐2031. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Broder KR, Martin DB, Vellozzi C. In the heat of a signal: responding to a vaccine safety signal for febrile seizures after 2010–11 influenza vaccine in young children, United States. Vaccine. 2012;30(11):2032‐2034. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pillsbury A, Cashman P, Leeb A, et al. Real‐time safety surveillance of seasonal influenza vaccines in children, Australia, 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20(43):30050. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.43.30050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. IMPACT after 17 years: lessons learned about successful networking. Paediatr Child Health. 2009;14(1):33‐39. doi: 10.1093/pch/14.1.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Canadian Pediatric Society . Surveillance [Internet]. Available from: https://cps.ca/impact. Modified March 24, 2022, accessed June 14, 2022.

- 42. Top KA, Macartney K, Bettinger JA, et al. Active surveillance of acute paediatric hospitalisations demonstrates the impact of vaccination programmes and informs vaccine policy in Canada and Australia. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(25):1900562. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.25.1900562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moghadas SM, Vilches TN, Zhang K, et al. The impact of vaccination on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreaks in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(12):2257‐2264. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid‐19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603‐2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403‐416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fazlollahi A, Zahmatyar M, Noori M, et al. Cardiac complications following mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines: a systematic review of case reports and case series. Rev Med Virol. 2021;e2318. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Truong DT, Dionne A, Muniz JC, et al. Clinically suspected myocarditis temporally related to COVID‐19 vaccination in adolescents and young adults: suspected myocarditis after COVID‐19 vaccination. Circulation. 2022;145(5):345‐356. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Patel T, Kelleman M, West Z, et al. Comparison of MIS‐C related myocarditis, classic viral myocarditis, and COVID‐19 vaccine related myocarditis in children. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;11(9):e024393. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.024393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bozkurt B, Kamat I, Hotez PJ. Myocarditis with COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines. Circulation. 2021;144(6):471‐484. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rathore SS, Rojas GA, Sondhi M, et al. Myocarditis associated with Covid‐19 disease: a systematic review of published case reports and case series. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(11):e14470. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Oster ME, Shay DK, Su JR, et al. Myocarditis cases reported after mRNA‐based COVID‐19 vaccination in the US from December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA. 2022;327(4):331‐340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Witberg G, Barda N, Hoss S, et al. Myocarditis after Covid‐19 vaccination in a large health care organization. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2132‐2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jain SS, Steele JM, Fonseca B, et al. COVID‐19 vaccination‐associated myocarditis in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2021;148(5):11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(33):2636‐2648. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sexson Tejtel SK, Munoz FM, Al‐Ammouri I, et al. Myocarditis and pericarditis: case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2022;40(10):1499‐1511. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015;68(12):1126. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gargano JW, Wallace M, Hadler SC, et al. Use of mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine after reports of myocarditis among vaccine recipients: update from the advisory committee on immunization practices—United States, June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(27):977‐982. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7027e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kracalik I, Oster ME, Broder KR, et al. Outcomes at least 90 days since onset of myocarditis after mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination in adolescents and young adults in the USA: a follow‐up surveillance study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(11):788‐798. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00244-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schauer J, Buddhe S, Gulhane A, et al. Persistent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging findings in a cohort of adolescents with post‐coronavirus disease 2019 mRNA vaccine myopericarditis. J Pediatr. 2022;245:233‐237. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fronza M, Thavendiranathan P, Karur GR, et al. Cardiac MRI and clinical follow‐up in COVID‐19 vaccine‐associated myocarditis. Radiology. 2022;304(3):220802. doi: 10.1148/radiol.220802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barda N, Dagan N, Ben‐Shlomo Y, et al. Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid‐19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(12):1078‐1090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Postigo R, Brosch S, Slattery J, et al. EudraVigilance Medicines Safety Database: publicly accessible data for research and public health protection. Drug Saf. 2018;41(7):665‐675. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0647-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. European Medicines Agency . COVID‐19 vaccines: update on ongoing evaluation of myocarditis and pericarditis. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/covid-19-vaccines-update-ongoing-evaluation-myocarditis-pericarditis. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- 64. Abraham N, Spruin S, Rossi T, et al. Myocarditis and/or pericarditis risk after mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination: a Canadian head to head comparison of BNT162b2 and mRNA‐1273 vaccines. Vaccine. 2022;40(32):4663‐4671. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Public Health Agency of Canada . Reported side effects following COVID‐19 vaccination in Canada [Internet]. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccine-safety/. Modified May 30, 2022, accessed June 14, 2022.

- 66. Clothier HJ, Crawford NW, Russell M, Kelly H, Buttery JP. Evaluation of ‘SAEFVIC’, a pharmacovigilance surveillance scheme for the spontaneous reporting of adverse events following immunisation in Victoria, Australia. Drug Saf. 2017;40(6):483‐495. doi: 10.1007/s40264-017-0520-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Australian Federal Government, Department of Health and Aged Care: Therapeutic Goods Administration . COVID‐19 vaccine weekly safety report—15‐07‐2021. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/periodic/covid-19-vaccine-weekly-safety-report-15-07-2021. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- 68. Cheng DR, Clothier HJ, Morgan HJ, et al. Myocarditis and myopericarditis cases following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines administered to 12–17‐year olds in Victoria, Australia. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2022;6(1):e001472. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2022-001472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dodd C, Andrews N, Petousis‐Harris H, Sturkenboom M, Omer SB, Black S. Methodological frontiers in vaccine safety: qualifying available evidence for rare events, use of distributed data networks to monitor vaccine safety issues, and monitoring the safety of pregnancy interventions. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(Suppl 2):e003540. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chouchana L, Blet A, Al‐Khalaf M, et al. Features of inflammatory heart reactions following mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination at a global level. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;111(3):605‐613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Patone M, Mei XW, Handunnetthi L, et al. Risks of myocarditis, pericarditis, and cardiac arrhythmias associated with COVID‐19 vaccination or SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Nat Med. 2022;28(2):410‐422. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01630-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Klein NP, Lewis N, Goddard K, et al. Surveillance for adverse events after COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1390‐1399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/slides-2021-06.html. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- 74. Gee J, Marquez P, Su J, et al. First month of COVID‐19 vaccine safety monitoring—United States, December 14, 2020–January 13, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(8):283‐288. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7008e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hause AM, Gee J, Baggs J, et al. COVID‐19 vaccine safety in adolescents aged 12‐17 years—United States, December 14, 2020–July 16, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(31):1053‐1058. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7031e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hause AM, Shay DK, Klein NP, et al. Safety of COVID‐19 vaccination in United States children ages 5 to 11 years. Pediatrics. 2022;150(2):e2022057313. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bettinger JA, Sadarangani M, De Serres G, et al. The Canadian National Vaccine Safety Network: surveillance of adverse events following immunisation among individuals immunised with the COVID‐19 vaccine, a cohort study in Canada. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e051254. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dinsmore N, McRae JE, Quinn HE, et al. Paediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance (PAEDS) 2019: prospective hospital‐based surveillance for serious paediatric conditions. Commun Dis Intell (2018). 2021;45. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2021.45.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pillsbury A, Quinn H, Cashman P, Leeb A, Macartney K, AusVaxSafety consortium . Active SMS‐based influenza vaccine safety surveillance in Australian children. Vaccine. 2017;35(51):7101‐7106. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cashman P, Moberley S, Dalton C, et al. Vaxtracker: active on‐line surveillance for adverse events following inactivated influenza vaccine in children. Vaccine. 2014;32(42):5503‐5508. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. AusVaxSafety . COVID‐19 vaccines [Internet]. Available from: https://ausvaxsafety.org.au/safety-data/covid-19-vaccines. Accessed July 13, 2022.

- 82. Chapin‐Bardales J, Myers T, Gee J, et al. Reactogenicity within 2 weeks after mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines: findings from the CDC v‐safe surveillance system. Vaccine. 2021;39(48):7066‐7073. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Brighton Collaboration . COVID‐19 AESI List 4th Update—September 2021 [Internet]. Available from: https://brightoncollaboration.us/covid-19-aesi-list-3rd-quarterly-update-september-2020/. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- 84. Ministry of Health . Surveillance of myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) cases between December 2020 and May 2021 (including). Press release of the Israeli Ministry of Health. February 6, 2021 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/01062021-03. Accessed December 13, 2022.

- 85. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Coronavirus (COVID‐19) update: June 25, 2021. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-june-25-2021. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- 86. Montgomery J, Ryan M, Engler R, et al. Myocarditis following immunization with mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines in members of the US military. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(10):1202‐1206. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Marshall M, Ferguson ID, Lewis P, et al. Symptomatic acute myocarditis in 7 adolescents after Pfizer‐BioNTech COVID‐19 vaccination. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Goddard K, Lewis N, Fireman B, et al. Risk of myocarditis and pericarditis following BNT162b2 and mRNA‐1273 COVID‐19 vaccination. Vaccine. 2022;40(35):5153‐5159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Williams SE, Klein NP, Halsey N, et al. Overview of the clinical consult case review of adverse events following immunization: Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) network 2004–2009. Vaccine. 2011;29(40):6920‐6927. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tozzi AE, Asturias EJ, Balakrishnan MR, Halsey NA, Law B, Zuber PL. Assessment of causality of individual adverse events following immunization (AEFI): a WHO tool for global use. Vaccine. 2013;31(44):5041‐5046. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Halsey NA, Edwards KM, Dekker CL, et al. Algorithm to assess causality after individual adverse events following immunizations. Vaccine. 2012;30(39):5791‐5798. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Arness MK, Eckart RE, Love SS, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(7):642‐651. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503‐1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ling RR, Ramanathan K, Tan FL, et al. Myopericarditis following COVID‐19 vaccination and non‐COVID‐19 vaccination: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(7):679‐688. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00059-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Switzer C, Loeb M. Evaluating the relationship between myocarditis and mRNA vaccination. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(1):83‐89. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2022.2002690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Engler RJ, Nelson MR, Collins LC Jr, et al. A prospective study of the incidence of myocarditis/pericarditis and new onset cardiac symptoms following smallpox and influenza vaccination. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0118283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Heymans S, Cooper LT. Myocarditis after COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination: clinical observations and potential mechanisms. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19(2):75‐77. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00662-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Snapiri O, Rosenberg Danziger C, Shirman N, et al. Transient cardiac injury in adolescents receiving the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(10):e360‐e363. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Rosner CM, Genovese L, Tehrani BN, et al. Myocarditis temporally associated with COVID‐19 vaccination. Circulation. 2021;144(6):502‐505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Larson KF, Ammirati E, Adler ED, et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 and mRNA‐1273 vaccination. Circulation. 2021;144(6):506‐508. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Chua GT, Kwan MYW, Chui CSL, et al. Epidemiology of acute myocarditis/pericarditis in Hong Kong adolescents following Comirnaty vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75:673‐681. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Kim HW, Jenista ER, Wendell DC, et al. Patients with acute myocarditis following mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(10):1196‐1201. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Karlstad O, Hovi P, Husby A, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination and myocarditis in a Nordic cohort study of 23 million residents. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(6):600‐612. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) . Summary of NACI advice on vaccination with COVID‐19 vaccines following myocarditis (with or without pericarditis) [Internet]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/summary-advice-vaccination-covid-19-vaccines-following-myocarditis-with-without-pericarditis.html. Accessed January 16, 2022.

- 105. Wallace M, Moulia D, Blain AE, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' recommendation for use of Moderna COVID‐19 vaccine in adults aged ≥18 years and considerations for extended intervals for administration of primary series doses of mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines—United States, February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(11):416‐421. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation . Guidance on myocarditis and pericarditis after mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/09/covid-19-vaccination-guidance-on-myocarditis-and-pericarditis-after-mrna-covid-19-vaccines_0.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2021.

- 107. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Clinical considerations for use of COVID‐19 vaccines currently approved or authorized in the United States [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/interim-considerations-us.html. Accessed July 22, 2022.

- 108. Fleming‐Dutra KE, Wallace M, Moulia DL, et al. Interim recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of Moderna and Pfizer‐BioNTech COVID‐19 vaccines in children aged 6 months–5 years—United States, June 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(26):859‐868. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7126e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]