To the Editor: The omicron BA.5 subvariant was the dominant variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)1 from July to November 2022 and showed substantial neutralization escape as compared with previous variants.2,3 Additional omicron variants have recently emerged, including the BA.4 sublineage BA.4.6, the BA.5 sublineages BF.7 and BQ.1.1, the BA.2 sublineage BA.2.75.2, and the BA.2 lineage recombinant XBB.1 (Figure 1A, and Figs. S1 through S5 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). All these variants have the R346T mutation in the spike protein. BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 have rapidly increased in frequency and have replaced BA.5 as dominant variants worldwide. However, the ability of these variants to evade neutralizing antibodies induced by vaccination and infection is unclear.

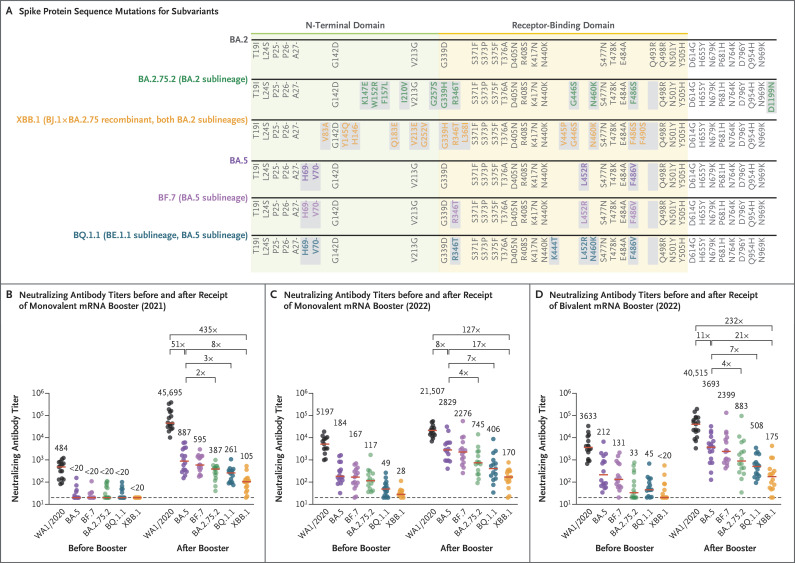

Figure 1. Neutralizing Antibody Responses to Omicron Subvariants.

Panel A shows spike protein sequences for the omicron BA.2, BA.2.75.2, XBB.1, BA.5, BF.7, and BQ.1.1 subvariants; mutations as compared with the WA1/2020 spike protein are shown. Mutations as compared with the BA.2 variant are indicated by gray boxes, and individual subvariant mutations are shown in colored font. The blank cells under Q493R represent reversions to the ancestral amino acid at this position. Panel B shows neutralizing antibody titers by luciferase-based pseudovirus neutralization assays in participants in 2021 at 6 months after the initial BNT162b2 vaccination (before booster) and after receipt of the BNT162b2 booster. In Panels B through D, dots indicate results in individual participants, red bars indicate medians, and factor differences are shown. The dashed line in each graph indicates the limit of detection. Panel C shows neutralizing antibody titers in participants before and after receipt of a monovalent mRNA booster in 2022, and Panel D shows neutralizing antibody titers in participants before and after receipt of a bivalent mRNA booster in 2022. Neutralizing antibody responses were measured against the WA1/2020 strain and the BA.5, BF.7, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 variants. The data regarding neutralizing antibodies against the WA1/2020 strain and the BA.5 variant in Panels C and D are from a separate study4 and are included here for comparison.

We first assessed neutralizing antibody titers in 16 participants who had been vaccinated and boosted with the monovalent mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech) in 2021 (Table S1). After the booster, the median neutralizing antibody titer to the WA1/2020 strain was 45,695 and the titers to the BA.5, BF.7, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 variants were 887, 595, 387, 261, and 105, respectively (Figure 1B). The median neutralizing antibody titers to the BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 variants were lower than the median titer to BA.5 by factors of 3 and 8, respectively.

We next evaluated neutralizing antibody titers in 15 participants who had received a monovalent mRNA booster in 2022 and in 18 participants who had received a bivalent mRNA booster in 2022, most of whom had received three previous doses of vaccine. In these two cohorts, 33% of the participants had had a documented SARS-CoV-2 omicron infection, but we suspect that the majority of participants had probably been infected owing to the high prevalence of omicron infection in 2022.

Before the booster, neutralizing antibody titers to the WA1/2020 strain and omicron variants were higher in the two 2022 cohorts than in the 2021 cohort. After the monovalent booster in 2022, the median neutralizing antibody titer to the WA1/2020 strain was 21,507 and the titers to the BA.5, BF.7, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 variants were 2829, 2276, 745, 406, and 170, respectively (Figure 1C). After the bivalent booster in 2022, the median neutralizing antibody titer to the WA1/2020 strain was 40,515, and the titers to the BA.5, BF.7, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 variants were 3693, 2399, 883, 508, and 175, respectively (Figure 1D). The median neutralizing antibody titers to the BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 variants were lower than the median titers to BA.5 by factors of 7 and 17, respectively, in the monovalent booster cohort and by factors of 7 and 21, respectively, in the bivalent booster cohort.

Our data show that the BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 variants escaped neutralizing antibodies substantially more effectively than the BA.5 variant by factors of 7 and 17, respectively, after monovalent mRNA boosting and by factors of 7 and 21, respectively, after bivalent mRNA boosting. The neutralizing antibody titers to BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 were dramatically lower than titers to the WA1/2020 strain by factors of 53 and 127, respectively, in the monovalent booster cohort and by factors of 80 and 232, respectively, in the bivalent booster cohort. These findings suggest that the BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 variants may reduce the efficacy of current mRNA vaccines and that vaccine protection against severe disease with these variants may depend on CD8 T-cell responses.5 The higher neutralizing antibody titers against omicron variants after monovalent mRNA boosting in the 2022 cohort than in the 2021 cohort probably reflect the greater numbers of vaccine doses and infections in the 2022 cohort. The incorporation of the R346T mutation into multiple new SARS-CoV-2 variants suggests convergent evolution.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on January 18, 2023, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by grants (CA260476 to Dr. Barouch; AI69309 to Dr. Collier) from the National Institutes of Health, the Massachusetts Consortium for Pathogen Readiness, and the Ragon Institute (to Dr. Barouch).

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Barouch DH. Covid-19 vaccines — immunity, variants, boosters. N Engl J Med 2022;387:1011-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hachmann NP, Miller J, Collier AY, et al. Neutralization escape by SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. N Engl J Med 2022;387:86-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Guo Y, Iketani S, et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature 2022;608:603-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collier AY, Miller J, Hachmann NP, et al. Immunogenicity of BA.5 bivalent mRNA vaccine boosters. N Engl J Med 2023;XXX:XXX-XXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wherry EJ, Barouch DH. T cell immunity to COVID-19 vaccines. Science 2022;377:821-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.