To the Editor: The BA.2.75 sublineage of the B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may escape neutralizing antibodies. The BA.2.75 sublineage (primarily the BA.2.75.2 subvariant) became the predominant sublineage in Qatar by September 10, 2022 (Section S1 and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). We estimated the effectiveness of previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 in preventing reinfection with BA.2.75 using a test-negative, case–control study design (Section S2).1

In this study, the effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection in preventing reinfection with BA.2.75 was defined as the proportional reduction in susceptibility to infection among persons who had had a previous infection as compared with those who had not been infected. We extracted data regarding SARS-CoV-2 laboratory testing, clinical infection, vaccination, and demographic details from the national SARS-CoV-2 databases, which include the results of all polymerase-chain-reaction and rapid antigen tests conducted at health care facilities in Qatar. Case participants (persons with positive SARS-CoV-2 tests) and controls (persons with negative SARS-CoV-2 tests) were matched exactly according to specific factors in order to balance observed confounders among the study groups (Figure 1).1,2 Previous infections were classified as pre-omicron infections if the positive test result was obtained before the onset of the omicron wave on December 19, 2021, and as omicron infections if the positive test result was obtained on or after that date.2 Omicron infections were further classified according to subvariant or sublineage on the basis of the time period during which such infections were predominant: between December 19, 2021, and June 7, 2022, for BA.1 and BA.2 infections2; between June 8, 2022, and September 9, 2022, for BA.4 and BA.5 infections2; and between September 10, 2022, and October 18, 2022, for BA.2.75 infections.

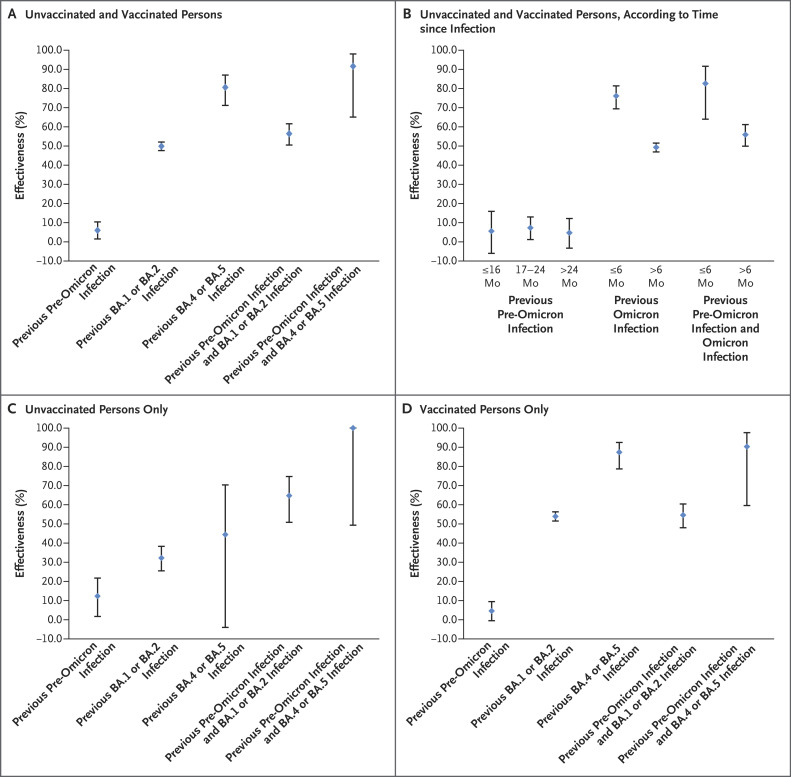

Figure 1. Effectiveness of Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Preventing Reinfection, Irrespective of the Presence of Symptoms, with an Omicron BA.2.75 Subvariant.

The study was conducted in Qatar between September 10, 2022, and October 18, 2022. Previous infections were classified as pre-omicron infections if the positive test result was obtained before the onset of the omicron wave on December 19, 2021, and as omicron infections (BA.1 or BA.2 infections or BA.4 or BA.5 infections) if the positive test result was obtained on or after that date. Case participants (persons with positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2] tests) and controls (persons with negative SARS-CoV-2 tests) were matched exactly according to sex, 10-year age group, nationality, number of coexisting medical conditions, number of vaccine doses that had been received by the time of the SARS-CoV-2 test, calendar week of testing, method of testing, and reason for testing. 𝙸 bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure S2 shows the process for selecting the study population. Table S1 summarizes the characteristics of the study population, which was found to be broadly representative of the overall population of Qatar (Table S2). Most persons had been vaccinated with the mRNA vaccines that target the ancestral strain.

The effectiveness of previous pre-omicron infection against reinfection with BA.2.75, irrespective of the presence of symptoms, was 6.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5 to 10.4) (Figure 1A and Table S3). The effectiveness of previous BA.1 or BA.2 infection was 49.9% (95% CI, 47.6 to 52.1), and the effectiveness of previous BA.4 or BA.5 infection was 80.6% (95% CI, 71.2 to 87.0). The effectiveness of previous pre-omicron infection, followed by BA.1 or BA.2 infection, against BA.2.75 reinfection was 56.4% (95% CI, 50.5 to 61.6). The effectiveness of previous pre-omicron infection, followed by BA.4 or BA.5 infection, was 91.6% (95% CI, 65.1 to 98.0).

We found similar but slightly higher effectiveness against symptomatic BA.2.75 reinfection (Table S3). Sensitivity analyses with adjustment for differences in testing frequency among the study groups confirmed the study results (Table S4). Analyses that were stratified according to the duration of time since the previous infection showed that the effectiveness of previous infection against any BA.2.75 reinfection was higher with more recent previous infection (Figure 1B and Table S5). Analyses that were stratified according to vaccination status indicated that the effectiveness of previous infection was higher among persons who had had previous omicron infection and had been vaccinated than among those who had had previous omicron infection and had not been vaccinated (Figure 1C and 1D and Table S5). These results confirm those of earlier reports, which indicated that previous pre-omicron infection or vaccination followed by omicron infection enhances protection against future omicron infection.3,4 Cases of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection were rare (Section S4). Limitations of the study are described in Section S2.

The effectiveness of previous infection against reinfection with BA.2.75.2 appears to be lower than that against BA.4 or BA.5 reinfection.2 Protection afforded by a previous pre-omicron infection is negligible at this stage of the pandemic, a finding that confirms that pre-omicron–conferred immunity against omicron infection may not last beyond approximately 1 year.5 Protection conferred by a previous omicron infection was moderate, at approximately 50%, when the previous infection was with a BA.1 or BA.2 subvariant but was approximately 80% when the previous infection was more recent (i.e., caused by a BA.4 or BA.5 subvariant); these results may reflect a combination of progressive immune-system evasion and gradual waning of immune protection. Immunity resulting from a combination of pre-omicron and omicron infection was most protective against BA.2.75 reinfection. Viral immune-system evasion may have accelerated recently to overcome high immunity in the global population, thereby also accelerating the waning of natural immunity.5

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on January 18, 2023, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by the Biomedical Research Program and the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core at Weill Cornell Medicine–Qatar; the Qatar Ministry of Public Health; Hamad Medical Corporation; and Sidra Medicine. The Qatar Genome Program and Qatar University Biomedical Research Center supported viral genome sequencing.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Ayoub HH, Tomy M, Chemaitelly H, et al. Estimating protection afforded by prior infection in preventing reinfection: applying the test-negative study design. January 3, 2022. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.02.22268622v1). preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Altarawneh HN, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, et al. Protective effect of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection against omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants. N Engl J Med 2022;387:1620-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Tang P, et al. Immune imprinting and protection against repeat reinfection with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med 2022;387:1716-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Tang P, et al. COVID-19 primary series and booster vaccination and immune imprinting. November 1, 2022. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.10.31.22281756v1). preprint.

- 5.Chemaitelly H, Nagelkerke N, Ayoub HH, et al. Duration of immune protection of SARS-CoV-2 natural infection against reinfection. J Travel Med 2022;29:taac109-taac109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.