Abstract

Single-chain antibodies neutralize activity and bind nonoverlapping epitopes of botulinum A neurotoxin. Two phage display epitope libraries were constructed from the 1.3 kb of binding domain cDNA. The minimal epitopes selected against the single-chain Fv-Fc antibodies correspond to conformational epitopes with amino acid residues 1115 to 1223 (S25), 1131 to 1264 (3D12), and 889 to 1294 (C25).

The anaerobic bacterium Clostridium botulinum produces a potent neurotoxin causing flaccid paralysis (19). Therapeutic strategies for toxicity associated with ingestion of contaminated food, infant bowel infection, and infected wounds include active immunization or passive immunotherapy with neutralizing antibodies. Antibotulinum antibodies exert therapeutic effects by inhibiting cellular receptor binding by the toxin of the heavy chain binding domain (HC) of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A (BoNT/A) (5, 6, 15, 16, 18, 26). Production of human immunoglobulins from immunized volunteers (2) involves risks of blood-borne contaminants. Thus, monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) with botulinum neurotoxin neutralizing activity offer an alternative treatment approach.

Recently, we selected antibody (Ab) single-chain variable fragments (scFv) to BoNT/A from phage libraries constructed using mice immunized with BoNT/A HC (MAbs S25 and C25) or humans immunized with pentavalent botulinum toxoid (MAb 3D12). scFv bind nonoverlapping epitopes with Kds of 7.3 × 10−8 M (S25) (1), 1.1 × 10−9 M (C25) (1), and 3.7 × 10−8 M (3D12) (P. Amersdorfer, unpublished data). These Abs neutralize BoNT/A in a mouse hemidiaphragm assay (170, 50, and 50% longer times to neuroparalysis for C25, S25, and 3D12, respectively) and are synergistic (1; Amersdorfer, unpublished). Epitopes of these antibodies have not been mapped, and the basis for the differential activity is unknown. Gene fragment libraries provide an attractive approach for epitope mapping because library members provide direct sequence information about the epitope (linear and conformational) (7). We used a gene fragment phage display to map neutralizing antitoxin epitopes.

Epitope libraries.

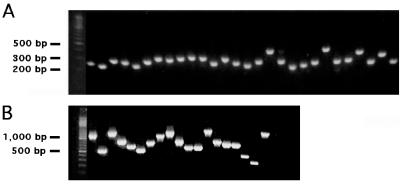

Two phage libraries were constructed from 1.3 kb of synthetic BoNT/A HC cDNA (GenBank accession no. U22962) (5). PCR DNA (from phage library BOT1) or plasmid DNA (from phage library BOT2) was randomly fragmented with DNase I (10 U/ml) in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.0)-10 mM MnCl2 for 8 min at 15°C, blunted with T4 polymerase for 30 min at 12°C, and ligated with SfiI restriction site linkers (link1, 5′-AGCGGCCGCAGGCCATGGAGGCC; link2, 5′-GGCCTCCATGGCCTGCGGCCGCT). Products of 200 (BOT1) or >300 (BOT2) bp were purified by gel (2%) electrophoresis. PCR template (100 ng of linker-ligated DNA) was amplified with nested primer LP5 (5′-GCGGCCGCAGGCCATGGA) for 30 cycles (94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min). The pORF1 gene fragment phage display vector was derived from pHEN-1 (10), containing a nonreligatable SfiI insert cloning site upstream of gene III. Optimized ligation mixtures were electroporated into Escherichia coli TG-1. The size distribution of library inserts was evaluated by PCR with primers flanking the cloning site (Sfiseq5, 5′-TCACCATCATCACGGGGCCAT; Sfiseq3, 5′-GTTTTTGTTCTGCGGCCGTTG) with Pfu polymerase for 30 cycles (94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min). DNA sequencing of random clones revealed fragments of HC vector sequence in both coding orientations. The BOT1 library contains 3 × 107 150- to 300-bp inserts, while the BOT2 library contains 8 × 106 300- to 1,200-bp inserts (Fig. 1), generously covering the sequence space (<104 bp).

FIG. 1.

Size distribution of PCR inserts from unselected BOT1 (A) and BOT2 (B) epitope phage libraries. Individual random clones were subjected to PCR amplification using primers immediately flanking the insert cloning site and analyzed on a 1% agarose gel.

Some unstable scFv unfold when immobilized onto solid surfaces. Thus, scFv were fused to a human Fc-immunoglobulin G1 scaffold (21). Expressed Fc fusion proteins, homodimers with increased avidity and stability, retained affinity (confirmed by BIAcore). Epitope phage was selected (17, 24) using Fc-coated (50-μg/ml) immunotubes. Random clones from the second round of selection were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (22, 24) on Fc-coated (50-μg/ml) plates, and binding clones were detected with a 1:1,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-M13. Selected clones did not cross-react with plastic, albumin, or immunoglobulin IgG. Positive controls included anti-erbB2 phage. The DNA sequences of ELISA-positive clones with unique insert sizes were determined, aligned by BLAST (accession no. P10845), and modeled using Rasmol. Significant enrichment occurred during selections except for those from the BOT1 library phage against MAb C25 mAb (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Results of epitope library selections on MAbs C25, S25, and 3D12a

| Antibody | Library | Phage titer (CFU/ml)

|

No. of ELISA-positive clones V/total no. of clones | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |||

| C25 | BOT1 | 1.4 × 107 | 7.5 × 105 | 0/95 |

| BOT2 | 1.7 × 106 | 1.5 × 108 | 5/95 | |

| S25 | BOT1 | 3.0 × 107 | 8.0 × 107 | 58/95 |

| BOT2 | 1.8 × 106 | 4.7 × 109 | 10/95 | |

| 3D12 | BOT1 | NDb | ND | ND |

| BOT2 | 3.5 × 106 | 7.0 × 1010 | 36/95 | |

Phage BoNT/A HC fragments (from library BOT1 or BOT2) were subjected to two rounds of selection on MAbs C25 S25, and 3D12, and the titers of the eluted phage were determined by infection with E. coli. After two rounds of selection, the number of antibody binding phage was determined by ELISA.

ND, not determined.

Epitope identification.

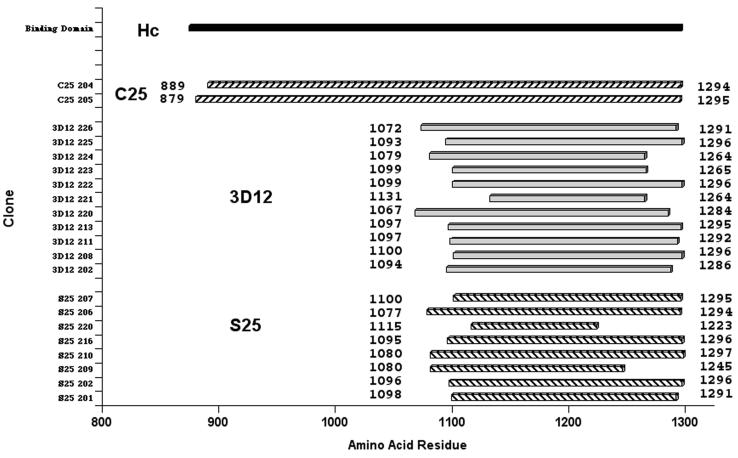

DNA sequencing revealed 8, 11, and 2 unique and overlapping clones for MAbs S25, 3D12, and C25, respectively (Fig. 2). The minimal consensus epitope regions correspond to holotoxin residues 1115 to 1223 (108 amino acids), 1131 to 1264 (133 amino acids), and 889 to 1294 (405 amino acids) for S25, 3D12, and C25, respectively (Fig. 2). These relatively large clones suggest complex conformational epitopes (13). Only the 3D12 antibody bound to the denatured HC fragment, as determined by Western blotting (data not shown). Fine mapping was performed by “peptide-on-a-pin,” with 54 peptides (15-mers, overlapping by seven amino acids) corresponding to the HC sequence (Mimotopes, San Diego, Calif.). None of the antibodies bound specifically to any of the peptide pins, confirming conformational epitopes. The BOT1-selected S25 and 3D12 clones are larger (500 to 600 bp) than those in the library (150 to 300 bp). In contrast, other gene fragment selections (50 to 400 bp) from multivalent rather than monovalent display libraries yield small epitopes (i.e., 50 to 200 bp) (3, 4, 8, 9, 11, 20, 27) that are perhaps related to multivalent, smaller fragments with higher functional affinity.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of epitope phage sequence with botulinum toxin and binding domain (HC) protein sequences. The DNA sequence of inserts from ELISA-positive clones was determined and aligned against the BoNT/A HC sequence using BLAST. The corresponding residues of each individual clone are indicated at the N and C termini. The sequences of the S25 and 3D12 clones overlap the C-terminal binding domain, while the C25 sequence overlaps the entire binding domain.

Three-dimensional structure.

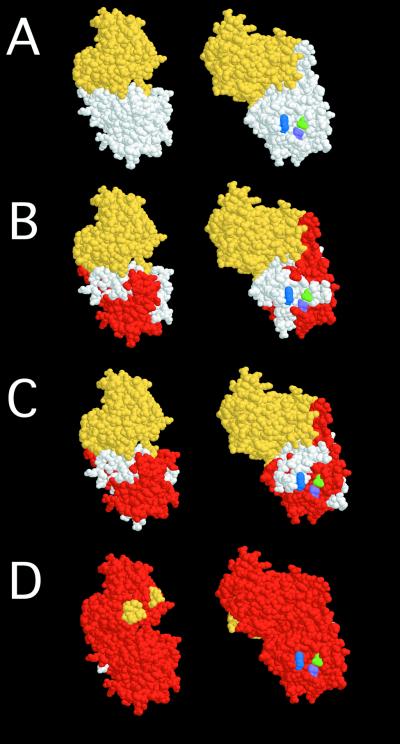

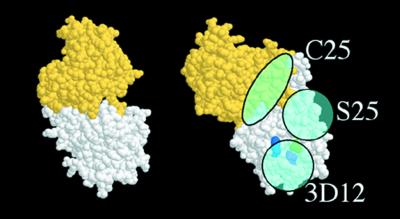

Recently, the crystal structure of BoNT/A (14) revealed that holotoxin is composed of three distinct functional domains: catalytic (residues 1 to 437), translocation (residues 448 to 872), and receptor binding (HC; residues 873 to 1295) (12). A molecular model overlay of selected epitopes corresponds to the three-dimensional HC. The BoNT/A binding domain consists of N- and C-terminal regions (Fig. 3A). The S25 (Fig. 3B) and 3D12 (Fig. 3C) epitopes map within the C-terminal subdomain, containing the putative sialo-ganglioside binding site (23, 25). Based on the botulinum neurotoxin serotype B structure, BoNT/A sialyllactose corresponds to Trp1265, His1252, and Glu1202 (Fig. 3). These residues are contained within the 3D12 epitope, proximal to the S25 epitope. Thus, it is likely that 3D12 neutralizes toxin by blocking binding to ganglioside (Fig. 4), while S25 may interfere with binding to this site or to the putative protein receptor (Fig. 4). C25 maps to a complex epitope that includes the majority of the HC sequence (Fig. 3D), suggesting an epitope of adjacent N- and C-terminal subdomains (Fig. 4), which would explain why small epitopes were not identified.

FIG. 3.

Molecular model overlay of neutralizing epitopes within the BoNT/A HC binding domain. (A) N-terminal (yellow) and C-terminal (white) subdomains of BoNT/A HC and putative ganglioside binding residues Glu1202 (purple), His1252 (green), and Trp1265 (blue). (B) S25 epitope. (C) 3D12 epitope. (D) C25 epitope. Minimal epitopes identified by phage display are indicated in red, while the remainder of the binding domain is indicated in yellow and white. Models were constructed using the coordinates of BoNT/A by use of Rasmol. S25 and 3D12 recognize the C-terminal subdomain of the binding domain, while C25 recognizes a complex epitope comprising the entire binding domain sequence.

FIG. 4.

Model of C25, S25, and 3D12 epitopes. A hypothetical model of the C25, S25, and 3D12 epitopes, based on the epitopes identified for each Ab by phage display, is shown.

Epitope mapping provides insight into why a single MAb cannot potently neutralize a toxin. Broad interaction of the C-terminal subdomain with cellular receptors is consistent with the mechanism of tetanus toxin (9). Potent toxin neutralization would require blockade of this broad surface, which could not be covered by a single Ab. Administration of all three MAbs may more potently neutralize toxin by blocking a larger proportion of the binding surface. Thus, it is unlikely that smaller peptides or HC fragments would be as potent an immunogen as the complete HC region would be.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Powers and Agnes Nowakowski for Fc-Ab and Andrew Bradbury and Peter Pavlik for fine mapping of peptides.

We gratefully acknowledge funding from grant DAMD-17-98-C-8030/CA78877/K22-85327.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amersdorfer P, Wong C, Chen S, Smith T, Deshpande S, Sheridan R, Finnern R, Marks J D. Molecular characterization of murine humoral immune response to botulinum neurotoxin type A binding domain as assessed by using phage antibody libraries. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3743–3752. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3743-3752.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnon S S. Clinical trial of human botulism immune globulin. New York, N.Y: Plenum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arza B, Felez J, Lopez-Alemany R, Miles L A, Munoz-Canoves P. Identification of an epitope of alpha-enolase (a candidate plasminogen receptor) by phage display. Thromb Haemostasis. 1997;78:1097–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bluthner M, Bautz E K, Bautz F A. Mapping of epitopes recognized by PM/Scl autoantibodies with gene-fragment phage display libraries. J Immunol Methods. 1996;198:187–198. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton M A, Clayton J M, Brown D R, Middlebrook J L. Protective vaccination with a recombinant fragment of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A expressed from a synthetic gene in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2738–2742. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2738-2742.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dertzbaugh M T, West M W. Mapping of protective and cross-reactive domains of the type A neurotoxin of Clostridium botulinum. Vaccine. 1996;14:1538–1544. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fack F, Hugle-Dorr B, Song D, Queitsch I, Petersen G, Bautz E K. Epitope mapping by phage display: random versus gene-fragment libraries. J Immunol Methods. 1997;206:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fehrsen J, du Plessis D H. Cross-reactive epitope mimics in a fragmented-genome phage display library derived from the rickettsia, Cowdria ruminantium. Immunotechnology. 1999;4:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s1380-2933(98)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzsimmons S P, Clark K C, Wilkerson R, Shapiro M A. Inhibition of tetanus toxin fragment C binding to ganglioside G(T1b) by monoclonal antibodies recognizing different epitopes. Vaccine. 2000;19:114–121. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoogenboom H R, Griffiths A D, Johnson K S, Chiswell D J, Hudson P, Winter G. Multi-subunit proteins on the surface of filamentous phage: methods for displaying antibody (Fab) heavy and light chains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4133–4137. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsson K, Frykberg L. Phage display shot-gun cloning of ligand-binding domains of prokaryotic receptors approaches 100% correct clones. BioTechniques. 1996;20:1070–1081. doi: 10.2144/96206rr04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieglstein K G, DasGupta B R, Henschen A H. Covalent structure of botulinum neurotoxin type A: location of sulfhydryl groups, and disulfide bridges and identification of C-termini of light and heavy chains. J Protein Chem. 1994;13:49–57. doi: 10.1007/BF01891992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuwabara I, Maruyama H, Kamisue S, Shima M, Yoshioka A, Maruyama I N. Mapping of the minimal domain encoding a conformational epitope by lambda phage surface display: factor VIII inhibitor antibodies from haemophilia A patients. J Immunol Methods. 1999;224:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacy D B, Tepp W, Cohen A C, DasGupta B R, Stevens R C. Crystal structure of botulinum neurotoxin type A and implications for toxicity. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:898–902. doi: 10.1038/2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaPenotiere H F, Clayton M A, Middlebrook J L. Expression of a large, nontoxic fragment of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A and its use as an immunogen. Toxicon. 1995;33:1383–1386. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(95)00072-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis G E, Angel P S U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. Biomedical aspects of botulism. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks J D, Hoogenboom H R, Bonnert T P, McCafferty J, Griffiths A D, Winter G. By-passing immunization: human antibodies from V-gene libraries displayed on phage. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:581–597. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90498-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Middlebrook J L, Brown J E. Immunodiagnosis and immunotherapy of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;195:89–122. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85173-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montecucco C, Schiavo G. Structure and function of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins. Q Rev Biophys. 1995;28:423–472. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereboeva L A, Pereboev A V, Wang L F, Morris G E. Hepatitis C epitopes from phage-displayed cDNA libraries and improved diagnosis with a chimeric antigen. J Med Virol. 2000;60:144–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers D B, Amersdorfer P, Poul M A, Nielsen U B, Shalaby M R, Adams G P, Marks J D. Expression of single-chain Fv-Fc fusions in Pichia pastoris. J Immunol Methods. 2001;251:123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schier R, Bye J, Apell G, McCall A, Adams G P, Malmqvist M, Weiner L M, Marks J D. Isolation of high-affinity monomeric human anti-c-erbB-2 single chain Fv using affinity-driven selection. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:28–43. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro R E, Specht C D, Collins B E, Woods A S, Cotter R J, Schnaar R L. Identification of a ganglioside recognition domain of tetanus toxin using a novel ganglioside photoaffinity ligand. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30380–30386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheets M D, Amersdorfer P, Finnern R, Sargent P, Lindquist E, Schier R, Hemingsen G, Wong C, Gerhart J C, Marks J D, Lindqvist E. Efficient construction of a large nonimmune phage antibody library: the production of high-affinity human single-chain antibodies to protein antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6157–6162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swaminathan S, Eswaramoorthy S. Structural analysis of the catalytic and binding sites of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin B. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:693–699. doi: 10.1038/78005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tacket C O, Shandera W X, Mann J M, Hargrett N T, Blake P A. Equine antitoxin use and other factors that predict outcome in type A foodborne botulism. Am J Med. 1984;76:794–798. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90988-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L F, Du Plessis D H, White J R, Hyatt A D, Eaton B T. Use of a gene-targeted phage display random epitope library to map an antigenic determinant on the bluetongue virus outer capsid protein VP5. J Immunol Methods. 1995;178:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00235-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]