Abstract

Rabbits orally challenged with Salmonella enterica developed a dose-dependent diarrheal disease comparable to human salmonellosis. Viable Salmonella organisms recovered from the intestine and deep tissues indicate local and systemic infections. Therefore, results show that the rabbit can be used as a model for diarrheal disease and sequelae associated with salmonellosis.

Salmonella enterica serotypes are the leading causes of food-borne illness worldwide (3), with approximately 50% of human infections caused by the serotypes Enteritidis and Typhimurium (4). Over 30% of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates are in the DT-104 phage type complex and exhibit the classic five-drug pattern of resistance (9). An infection with an S. enterica serotype generally causes a localized intestinal infection or gastroenteritis characterized by a sudden onset of abdominal pain and loose, watery diarrhea, occasionally with mucus or blood (11). In localized infections, the organisms invade the intestinal wall but remain predominantly within gut tissue and the local lymphatics. However, S. enterica serotypes can spread systemically in the elderly, in young children, and in immunocompromised individuals. Reports from the United Kingdom suggest that infection with five-drug-resistant serotype Typhimurium may result in greater morbidity and mortality than infection with other serotypes (9).

The murine enteric fever model has been extensively utilized to evaluate Salmonella pathogenicity. However, the lack of diarrheal disease in this model is limiting for the study of food-borne illness. Collins and Carter (6) have shown that germfree mice develop diarrhea when they are orally challenged with as few as 10 CFU of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis and that they die within 8 days of challenge. Although these animals develop diarrhea, they may not be representative of conventional animals. Surgical models that measure fluid accumulation as an indication of diarrheal disease caused by S. enterica serotypes have been developed with large animal species (1, 5, 10, 13), and several nonsurgical models for diarrheal disease have been developed with pigs (15, 20), calves (18, 19, 21), ponies (16), and primates (12, 17). However, these animals are not readily available in a standard animal facility, and therefore the usage of large numbers for in-depth studies is precluded. Salmonella virulence has also been examined using ligated rabbit or isolated intestinal sections (2, 5, 8). Although these models have been valuable for identifying Salmonella strains and genes that induce fluid accumulation, these surgical models do not represent the desired model, which would demonstrate the route and course of infection seen with food-borne salmonellosis.

This work describes a nonsurgical, oral challenge rabbit model for salmonella gastroenteritis. Rabbits develop a dose-dependent diarrheal illness that is comparable to that seen in human salmonellosis. A multidrug-resistant strain of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium phage type DT-104b, designated DT-9, which was isolated from children in a day care center, was used as the primary salmonella isolate. An outbreak-associated strain was chosen since the focus of this model is to emulate symptoms seen with food-borne salmonellosis.

Overnight cultures of salmonellae grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth in a microaerophilic environment were used for all challenge studies. All cultures were serially diluted 10-fold in LB broth immediately before challenge, and their inoculum size was confirmed by plate counts. The killed salmonella controls were inactivated by heating to 100°C for 1 min; nonviability was then verified by plating onto Trypticase soy agar plates (Becton Dickinson & Co. Microbiology Systems, Sparks, Md.). Adult New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits (Covance, Denver, Pa.) were used for all studies, and all procedures were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (14). Rabbits deprived of food for 16 h were challenged with salmonellae using a method adapted from Cray et al. (7). Animals were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of ketamine and acepromazine (70 and 0.4 mg per kg of body weight, respectively) and then intravenously administered 50 mg of cimetidine (National Logistics Services, Owings Mills, Md.) per kg. Animals were then intubated using a pediatric feeding tube, and two doses of 5% sodium bicarbonate were orally administered at 15-min intervals. The second dose of sodium bicarbonate was immediately followed by oral administration of 15 ml of bacterial culture at a concentration of 1011, 109, 107, 105, or 103 CFU per animal. The control animals were challenged with 1011 CFU of heat-killed salmonellae or with LB broth alone. To slow intestinal peristalsis, all animals were given an intraperitoneal injection of 2.0 ml of paregoric (2 mg/5 ml; National Logistics Services). Rabbits were examined for loose stool, diarrhea, anorexia, and weight loss. Rectal swabs were collected on a triweekly basis and cultured on Hektoen enteric agar (HEA) following 18 h of preenrichment in lactose broth.

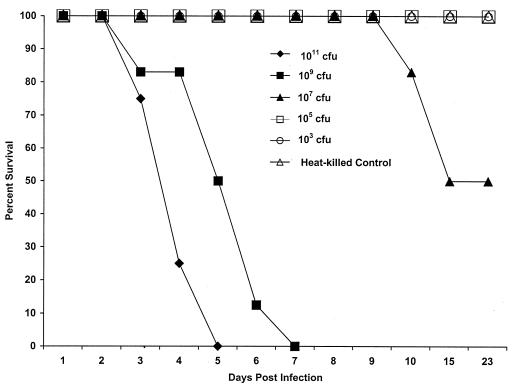

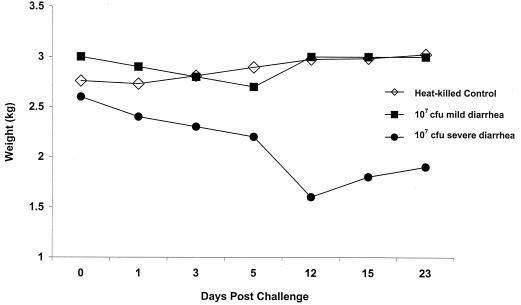

A dose-response relationship was seen between time of challenge and time of animal death. All animals challenged with either 1011 or 109 CFU of DT-9 developed symptoms which progressed from loose stool containing mucus by day 3 postinfection (p.i.) to watery diarrhea containing frank blood by day 5 p.i. All rabbits challenged with 1011 CFU died by day 5. Initial deaths of animals challenged with 109 CFU were seen at day 3 p.i., with all rabbits succumbing to infection by day 7 p.i. Rectal swabs from the majority of animals in all challenge groups were positive for salmonellae (Table 1), and necropsy revealed fluid accumulation in the cecum and small intestine. One-half of all rabbits challenged with 107 CFU of serotype Typhimurium developed watery diarrhea containing mucus and blood by day 5 p.i., and deaths were seen at day 10 p.i. (Fig. 1). Animal deaths in the 107-CFU challenge group occurred after all rabbits challenged with 1011 and 109 CFU had died, supporting the dose-response relationship between challenge and time of death. Twenty-five percent of animals challenged with 107 CFU of DT-9 developed severe watery diarrhea containing mucus and blood. At the height of their illness, animals lost from 16 to 30% of their initial body weights, a significant loss compared with the results from the controls (Fig. 2). However, these animals began to recover from the infection on day 14 p.i., as evidenced by weight gain and increased food consumption. By day 23 p.i., the animals were symptom free and within 90% of their prechallenge weights (Fig. 2). Rectal swabs from these animals were salmonella negative by day 15 p.i. (Table 1). For approximately 7 days, the remaining 25% of the animals challenged with 107 CFU exhibited occasional loose stools mixed with formed stools. These animals had a slight weight drop of ≤10% of initial body weight between days 3 and 5 p.i., but weight loss was not significantly different from that of control animals during this time period (Fig. 2). Animals challenged with 105 CFU exhibited no symptomatology, but salmonellae were recovered from the stools of these animals for up to 7 days p.i., indicating a viable bacterial challenge and some intestinal colonization. Rabbits challenged with 103 CFU shed salmonellae in their feces for only 3 days p.i., indicating challenge with viable bacteria but no colonization.

TABLE 1.

Rabbit colonization following oral challenge with DT-9a

| Challenge dose (CFU) | Animals colonized on indicated day p.i.b

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 15 | |

| 1011 | 11/12 | 6/9 | —c | ||||

| 109 | 10/12 | 7/10 | 4/6 | — | |||

| 107 | 10/12 | 7/12 | 6/12 | 11/12 | 10/10 | 2/6 | 0/6 |

| 105 | 4/12 | 9/12 | 6/12 | 3/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 |

| 103 | 2/4 | 3/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| 1011 (HK)d | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/8 |

| 0 (LB broth)e | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 |

Rectal swabs obtained from all animals were preenriched for salmonellae by growth in lactose broth for 18 h at 37°C and then cultured on HEA to determine the presence of salmonellae.

Data are numbers of animals with fecal samples positive for salmonellae out of numbers of surviving animals in challenge groups.

—, all animals in group dead.

HK, heat-killed control.

Bacterial growth medium control.

FIG. 1.

Survival rates of adult NZW rabbits orally challenged with DT-9. Results were obtained from three separate trials with 4 rabbits per challenge or control group for a total of 12 animals per treatment and from one trial with 4 animals challenged with 103 CFU and 4 heat-killed controls. All rabbits challenged with 1011 or 109 CFU of DT-9 died from infection by day 7 p.i. A dose of 107 CFU represented the 50% pathogenic endpoint for this isolate. All control rabbits and those challenged with 105 and 103 CFU survived challenge with DT-9.

FIG. 2.

Weight changes of rabbits challenged with 107 CFU of viable DT-9 or with heat-killed DT-9 as a control. Animals challenged with 107 CFU demonstrated two different patterns of weight change. One group of three rabbits showed a slight drop in weight between days 3 and 5 p.i.; by day 12 p.i., the weights of the rabbits in this group returned to control values. A second group of three animals challenged with 107 CFU demonstrated a severe weight loss, beginning on day 3, that peaked by day 12 p.i. These animals did recover from infection and initiated weight gain beginning on day 15 p.i. The control group consisted of four animals challenged with heat-killed serotype Typhimurium. Each symbol represents the average weight of all animals in each group at each time point.

Using pentobarbital (100 mg/kg), three representative rabbits challenged with 107 CFU of serotype Typhimurium and three challenged with heat-killed salmonellae were euthanized after the onset of diarrhea in the challenge group (approximately 7 days p.i.). To assess bacterial colonization, a 1.0-ml sample of cecal contents and tissues of known weight from the upper and lower intestines, spleen, and liver were aseptically removed. Tissue samples were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline, the homogenates and cecal contents were serially diluted 10-fold in phosphate-buffered saline, and 100 μl of each dilution was plated onto HEA plates and incubated at 37°C overnight. No viable bacteria were recovered from the tissues harvested from animals challenged with heat-killed serotype Typhimurium. However, viable Salmonella organisms were recovered from the cecal contents (1.2 × 107 ± 1.5 × 107), upper intestines (2.4 × 105 ± 3.4 × 105), and lower intestines (6.0 × 107 ± 1.7 × 107) of the rabbits challenged with 107 CFU of DT-9. Salmonella was also recovered from the livers (6.4 × 104 ± 1.0 × 104) and spleens (9.8 × 104 ± 8.7 × 104) of the challenged animals, and blood cultures were salmonella positive. These results show that bacteremia and invasion of deep tissue can occur in this model.

These data show that, when this model is used, NZW rabbits develop a diarrheal syndrome comparable to that seen in human salmonella gastroenteritis. Animals responded in a dose-dependent manner, with a challenge of 107 CFU representing the 50% pathogenic endpoint. These results also suggest that >105 CFU is needed to establish diarrheal disease in rabbits. Animals challenged with heat-killed salmonellae showed no signs of clinical illness, indicating that viable Salmonella is required for development of diarrheal disease in this model and that symptoms are not the results of a preformed toxin(s) or lipopolysaccharide. Several rabbits also developed infection of the deep tissues and septicemia, sequelae associated with salmonella infection. Control animals that were fed culture media also remained symptom free, showing that growth media alone do not cause diarrhea in rabbits. To confirm that this model can be used with serotypes other than serotype Typhimurium, we completed a smaller study using an Enteritidis serotype isolated from a food-borne outbreak. The dose-response curve and symptomatology for this isolate were identical to those seen with the DT-9 study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Colleen Carroll for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bolton A J, Osborne M P, Wallis T S, Stephen J. Interaction of Salmonella choleraesuis, Salmonella dublin and Salmonella typhimurium with porcine and bovine terminal ileum. Microbiology. 1999;145:2431–2441. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-9-2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolton A J, Martin G D, Osborne M P, Wallis T S, Stephen J. Invasiveness of Salmonella serotypes Typhimurium, Choleraesuis and Dublin for rabbit terminal ileum in vitro. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:801–810. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-9-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of notifiable diseases, United States—1997. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;46:1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Salmonella surveillance, annual summary, 1993–1995. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke R C, Gyles C L. Virulence of wild and mutant strains of Salmonella typhimurium in ligated intestinal segments of calves, pigs, and rabbits. Am J Vet Res. 1987;48:504–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins F M, Carter P B. Growth of salmonellae in orally infected germfree mice. Infect Immun. 1978;21:41–47. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.1.41-47.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cray W C, Jr, Tokunaga E, Pierce N F. Successful colonization and immunization of adult rabbits by oral inoculation with Vibrio cholerae O1. Infect Immun. 1983;41:735–741. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.735-741.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everest P, Ketley J, Hardy S, Douce G, Khan S, Shea J, Holden D, Maskell D, Dougan G. Evaluation of Salmonella typhimurium mutants in a model of experimental gastroenteritis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2815–2821. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2815-2821.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glynn M K, Bopp C, Dewitt W, Dabney P, Mokhtar M, Angulo F J. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 infections in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1333–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grøndahl M L, Jense G M, Nielsen C G, Skadhauge E, Olsen J E, Hansen M B. Secretory pathways in Salmonella Typhimurium-induced fluid accumulation in the porcine small intestine. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:151–157. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-2-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrant R L, Hook E W. Salmonella infections. In: Petersdorf R G, Adams R D, Braunwald E, Isselbacher K J, Martin J B, Wilson J D, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1993. pp. 961–965. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinsey M D, Dammin G J, Formal S B, Giannella R A. The role of altered intestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of salmonella diarrhea in the rhesus monkey. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray M J, Doran R E, Pfeiffer C J, Tyler D E, Moore J N, Sriranganathan N. Comparative effects of cholera toxin, Salmonella typhimurium culture lysate, and viable Salmonella typhimurium in isolated colon segments in ponies. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen B, Baggesen D, Bager F, Haugegaard J, Lind P. The serological response to Salmonella serovars Typhimurium and Infantis in experimentally infected pigs. The time course followed with an indirect anti-LPS ELISA and bacteriological examinations. Vet Microbiol. 1995;47:205–218. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen R, Fullerton J N, Tizard I R, Lumsden J H, Barnum D A. Studies on experimental enteric salmonellosis in ponies. Can J Comp Med. 1979;43:247–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rout W R, Formal S B, Dammin G J, Giannella R A. Pathophysiology of Salmonella diarrhea in the rhesus monkey: intestinal transport, morphological and bacteriological studies. Gastroenterology. 1974;67:59–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith B P, Habasha F, Reina-Guerra M, Hardy A J. Bovine salmonellosis: experimental production and characterization of the disease in calves, using oral challenge with Salmonella typhimurium. Am J Vet Res. 1979;40:1510–1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsolis R M, Adams L G, Ficht T A, Bäumler A J. Contribution of Salmonella typhimurium virulence factors to diarrheal disease in calves. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4879–4885. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4879-4885.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood R L, Rose R. Populations of Salmonella typhimurium in internal organs of experimentally infected carrier swine. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53:653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wray C, Sojka W J. Experimental Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves. Res Vet Sci. 1978;25:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]