ABSTRACT

Peptidoglycan (PG) is a unique and essential component of the bacterial cell envelope. It is made up of several linear glycan polymers cross-linked through covalently attached stem peptides making it a fortified mesh-like sacculus around the bacterial cytosolic membrane. In most bacteria, including Escherichia coli, the stem peptide is made up of l-alanine (l-Ala1), d-glutamate (d-Glu2), meso-diaminopimelic acid (mDAP3), d-alanine (d-Ala4), and d-Ala5 with cross-links occurring either between d-ala4 and mDAP3 or between two mDAP3 residues. Of these, the cross-links of the 4-3 (d-Ala4-mDAP3) type are the most predominant and are formed by penicillin-binding D,D-transpeptidases, whereas the formation of less frequent 3-3 linkages (mDAP3-mDAP3) is catalyzed by L,D-transpeptidases. In this study, we found that the frequency of the 3-3 cross-linkages increased upon cold shock in exponentially growing E. coli and that the increase was mediated by an L,D-transpeptidase, LdtD. We found that a cold-inducible RNA helicase DeaD enhanced the cellular LdtD level by facilitating its translation resulting in an increased abundance of 3-3 cross-linkages during cold shock. However, DeaD was also required for optimal expression of LdtD during growth at ambient temperature. Overall, our study finds that E. coli undergoes PG remodeling during cold shock by altering the frequency of 3-3 cross-linkages, implying a role for these modifications in conferring fitness and survival advantage to bacteria growing in diverse environmental conditions.

IMPORTANCE Most bacteria are surrounded by a protective exoskeleton called peptidoglycan (PG), an extensively cross-linked mesh-like macromolecule. In bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, the cross-links in the PG are of two types: a major fraction is of 4-3 type whereas a minor fraction is of 3-3 type. Here, we showed that E. coli exposed to cold shock had elevated levels of 3-3 cross-links due to the upregulation of an enzyme, LdtD, that catalyzed their formation. We showed that a cold-inducible RNA helicase DeaD enhanced the cellular LdtD level by facilitating its translation, resulting in increased 3-3 cross-links during cold shock. Our results suggest that PG remodeling contributes to the survival and fitness of bacteria growing in conditions of cold stress.

KEYWORDS: cold shock; DeaD; L,D-transpeptidases; LdtD; NlpI; peptidoglycan

INTRODUCTION

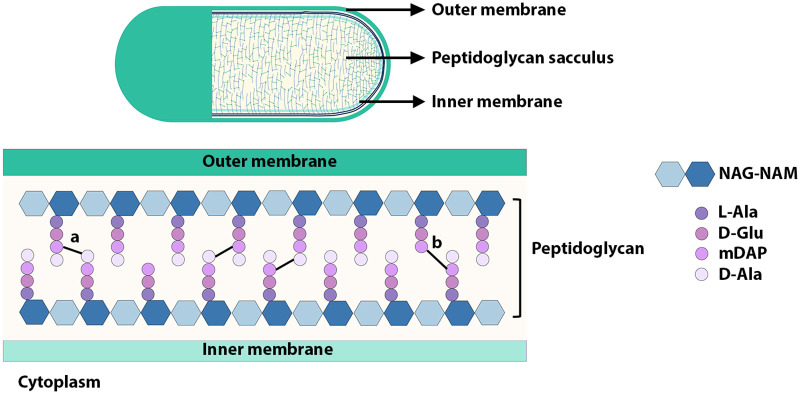

The gram-negative bacterial cell envelope is a multipartite structure comprising a surface-exposed outer membrane (OM) and an inner membrane (IM) lining the cytoplasm. Between these two layers is the periplasmic space, which harbors a highly cross-linked net-like macromolecule known as peptidoglycan (PG). By enclosing the IM, PG provides mechanical strength to resist the internal osmotic pressure and the bacterial cell shape (1). Chemically, PG is made up of linear glycan polymers with repeating disaccharide units of N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) bonded through β-1,4 covalent linkages. In many bacteria, including E. coli, the lactoyl moiety of each NAM residue of the glycan strands is covalently attached to a short stem peptide chain made up of l-alanine (l-Ala1), d-glutamate (d-Glu2), meso-diaminopimelic acid (mDAP3), d-alanine (d-Ala4), and d-alanine (d-Ala5). The third position of the peptide chain is mostly a dibasic amino acid mDAP, through which the stem peptides of adjacent glycan strands are cross-linked, giving PG its characteristic mesh-like structure (Fig. 1) (2–6).

FIG 1.

Schematic depiction of peptidoglycan sacculus of E. coli. The figure represents a Gram-negative bacterial cell in which the OM was partially peeled off. PG is a highly cross-linked sac-like structure situated between the OM and IM in the periplasmic space. PG is made up of linear glycan strands of NAG (light blue) and NAM (dark blue) bonded through β,1-4 linkages. Each NAM residue is attached to a stem peptide, which is usually a tetrapeptide made up of l-Ala1, d-Glu2, mDAP3, and d-Ala4. Glycan strands are interlinked to each other via stem peptides cross-bridged either between d-Ala4 and mDAP3 (4-3; depicted as ‘a’) or between two mDAP3 residues (3-3; depicted as ‘b’). Cross-linking is indicated by a black line between the stem peptides.

In actively growing E. coli, 40% of neighboring peptides are cross-linked with each other, among which ~93% are between d-Ala4 of a stem peptide and mDAP3 of an adjacent stem peptide (4-3 cross-links or d-Ala4-mDAP3) catalyzed by penicillin-binding PG synthases (PBP1A, PBP1B, PBP2, and PBP3) (7). The other ~7% are between two mDAP3 residues of adjacent peptide chains (3-3 cross-links or mDAP-mDAP) formed through the catalytic activity of L,D-transpeptidases (LDTs), LdtD, and LdtE (8). Apart from catalyzing 3-3 cross-links, LdtD and LdtE exchange the terminal amino acid of the stem peptide d-Ala4/5 mostly with a glycine residue or rarely with noncanonical d-amino acids such as D-tryptophan, D-methionine or D-aspartate (3, 8, 9).

Among the two types of cross-links, the abundance and frequency of 3-3 cross-links are known to vary during growth in diverse environmental conditions (3, 10–12). For example, during envelope stress, the abundance of 3-3 cross-links is increased through the upregulation of LdtD by a two-component system CpxA-CpxR, thereby strengthening the PG to avoid cell lysis (10, 12). Similarly, 3-3 cross-links are increased in the stationary phase of E. coli due to the upregulation of LdtE by a stationary phase-specific transcription factor σS (13). In addition, during intracellular growth, Salmonella enterica PG displays increased 3-3 cross-links (14, 15). Although 3-3 cross-links are dispensable for the growth of E. coli in laboratory conditions, they confer growth fitness during exposure to various stress conditions and β-lactam antibiotics (12, 16–19). Recent evidence indicates that LDTs together with MepK, a 3-3 cross-link specific endopeptidase, facilitate PG growth and expansion in the absence of 4-3 cross-links highlighting the importance of 3-3 cross-links in the maintenance of PG integrity (17, 20, 21).

As PG sacculus forms a continuous network around the IM, the growth of a cell is coupled to that of PG expansion. Given that PG is a highly cross-linked mesh, during the process of bacterial cell growth, pre-existing cross-links must be broken to make space for the incorporation of nascent strands. In E. coli, this is achieved by redundant endopeptidases MepS, MepM, and MepH, which cut the 4-3 cross-links, and MepK that cleaves the 3-3 cross-links between the two stem peptides (20, 22). Although cross-link hydrolysis is fundamental for PG expansion, the unregulated activity of the PG hydrolases is detrimental to cell wall integrity. Therefore, their levels must be stringently regulated. Previously, our lab identified a periplasmic proteolytic system comprising an OM lipoprotein NlpI and a protease Prc that regulates the stability of the endopeptidase MepS in a growth phase-specific manner (23). Here, NlpI functions as an adaptor protein that brings Prc and MepS into proximity to facilitate MepS degradation (23, 24). In addition, NlpI has also been shown to bind and modulate the stability of several other PG endopeptidases and synthases (25).

During our studies on NlpI, we observed that multiple copies of either of LDTs, LdtD, or −E were able to rescue the growth defects of a nlpI deletion mutant, indicating a role for NlpI in the regulation of 3-3 cross-link formation. Further detailed analysis revealed that deletion of nlpI conferred polarity on the expression of downstream gene deaD. Interestingly, we observed that the absence of DeaD lowered cellular LdtD levels and reduced the frequency of 3-3 cross-linkages in the PG sacculi, suggesting a previously unknown role for DeaD in PG remodeling. DeaD is an essential cold-inducible RNA helicase and mutants lacking deaD grow poorly below 15°C (26). DeaD is known to unwind complex RNA secondary structures (26, 27) and to facilitate the translation of certain mRNAs by destabilizing the inhibitory stem-loop structures located either in 5’UTR or in the coding sequence (28). Here, we find that DeaD contributes to the effective translation of LdtD, thereby enhancing its levels and leading to increased 3-3 cross-linkages during cold shock. Overall, this study signifies the importance of cell wall remodeling in the survival and fitness of bacteria encountering stressful environmental conditions, such as cold stress.

RESULTS

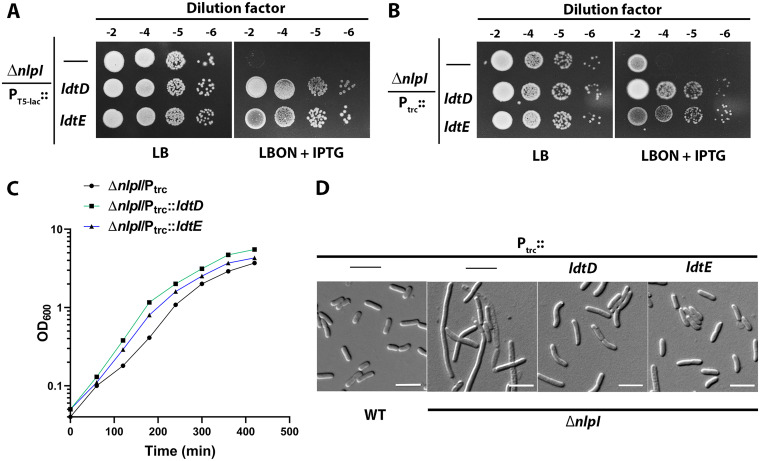

Multiple copies of LdtD or −E alleviated growth defects of the nlpI deletion mutant.

A strain lacking nlpI is sensitive to low osmolarity and does not grow on LBON (LB without NaCl) or nutrient agar (NA) (29). This growth defect (LBONS) is primarily attributed to the unregulated 4-3 cross-link cleaving activity of MepS because its deletion completely rescues this phenotype (23). To identify additional factors that alleviate the growth defect of nlpI, we transformed the ASKA plasmid library (a complete gene library of E. coli cloned downstream to isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) inducible promoter (PT5-lac::), obtained from National BioResource Project (NBRP), Japan (30)) into nlpI mutant and screened for colonies growing on LBON plates. Of these, a plasmid clone encoding ldtD conferred a modest growth advantage to the nlpI mutant (Fig. 2A). In addition, an ASKA plasmid encoding LdtE also suppressed the nlpI phenotypes (Fig. 2A). To further confirm the above observations, we cloned functional ldtD or ldtE downstream of an IPTG inducible trc promoter (Ptrc::) in a medium copy vector pTrc99a and introduced these plasmids into the ΔnlpI mutant. Viability assays and growth curves indicated that overexpression of Ptrc::ldtD or ldtE also suppressed the ΔnlpI phenotype similar to that of the ASKA clones (Fig. 2B and C). Mutants lacking NlpI are known to be filamentous in a low osmolar medium (29), and overexpression of LdtD or LdtE was able to partially restore the cell morphology phenotype (Fig. 2D). Like that of ΔnlpI, a mutant lacking Prc (Δprc) also exhibits increased MepS levels rendering cells sensitive to low osmolar media (23). As expected, overexpression of LdtD or LdtE was able to suppress the LBONS phenotype of Δprc mutant (Fig. S1A in Supplemental File 1). These results demonstrated that increased 3-3 cross-links partially restored the viability of both nlpI and prc deletion mutants, suggesting that elevated levels of 3-3 cross-links compensated for the decreased 4-3 cross-links in these mutants.

FIG 2.

Overexpression of LdtD or LdtE alleviated ΔnlpI phenotypes. (A) Growth of ΔnlpI mutant carrying the empty vector (ASKA plasmid; PT5-lac::) or its ldtD or ldtE derivatives at 37°C on indicated plates with 50 μM IPTG. (B) Growth of ΔnlpI mutant carrying the empty vector (pTrc99a; Ptrc::) or its derivatives harboring ldtD or ldtE on LB or LBON plates supplemented with 50 μM IPTG. (C) Growth curve of ΔnlpI mutant carrying the empty vector (pTrc99a) or its derivatives carrying ldtD or ldtE in LBON broth supplemented with 50 μM IPTG at 42°C. (D) Differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopic images of ΔnlpI cells with pTrc99a or its derivatives were grown in LBON containing 50 μM IPTG at 42°C. The scale bar represents 5 μm.

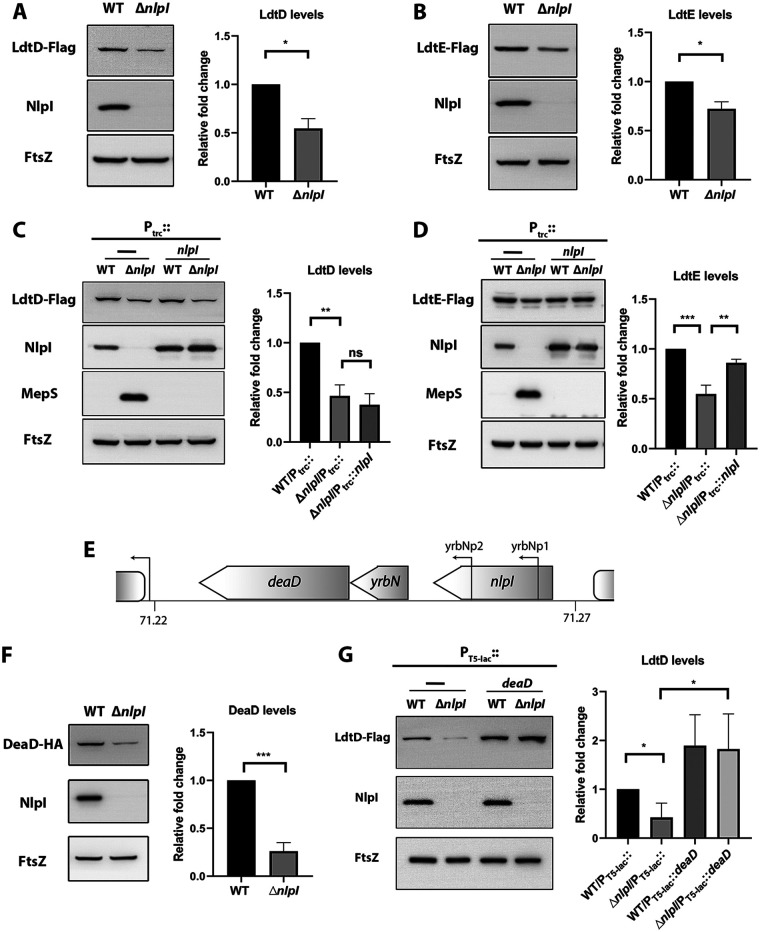

Deletion of nlpI is polar on the expression of a downstream gene, deaD.

NlpI and Prc form a proteolytic complex, which controls the stability of MepS (23). To check whether the NlpI-Prc system had any role in the regulation of LdtD or LdtE, we constructed functional C-terminal Flag fusions encoded at the native chromosomal loci and examined their levels by Western blotting. Fig. 3 shows that the absence of NlpI lowered the LdtD level by ~50% and that of LdtE to ~70% compared to an isogenic wild-type (WT) strain (Fig. 3A and B). To confirm whether the above phenotypes were due to the deletion of nlpI, we performed complementation using a full-length nlpI gene cloned under an IPTG-inducible promoter (23). Surprisingly, the plasmid-borne NlpI did not restore the LdtD levels, whereas it did rescue the levels of LdtE (Fig. 3C and D). This confounding result prompted us to examine the possibility of a polarity effect created by nlpI deletion on the expression of the downstream gene, deaD. It has also been observed earlier that mRNA levels of deaD are lower in a strain lacking nlpI (31). Incidentally, two promoters of the gene deaD are located within the coding sequence of nlpI (Fig. 3E). To examine whether DeaD levels were affected in ΔnlpI mutant, we tagged the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope to the C terminus of deaD at the native locus and probed its levels in nlpI deletion mutant. Corroborating the earlier studies, the DeaD level was approximately 3-fold lower in ΔnlpI in comparison to the WT (Fig. 3F). Further, a plasmid-borne copy of DeaD increased the LdtD level in both the WT and ΔnlpI strains (Fig. 3G), confirming the polar effect of nlpI deletion on the expression of deaD. Importantly, these results suggested that DeaD influences the abundance of cellular LdtD.

FIG 3.

Deletion of nlpI is polar on the expression of downstream gene deaD. Western blots showing levels of (A) LdtD-Flag or (B) LdtE-Flag in the WT and ΔnlpI strain backgrounds. (C) Western blot showing an LdtD-Flag in the ΔnlpI mutant with plasmid-borne nlpI (pTrc99-nlpI) (D) LdtE-Flag levels in indicated strains. (E) Schematic representation indicating promoter sites of deaD (Yrbnp1 and p2) within the nlpI gene. Block arrows indicate the direction of transcription. (F) Western blot showing DeaD-HA levels in the WT and ΔnlpI mutant. (G) LdtD-Flag levels of the WT and ΔnlpI mutant with empty vector (PT5-lac::) or vector carrying deaD grown in the presence of 50 μM IPTG. Indicated strains are grown in LB at 37°C until OD600 of 1.0, harvested, and analyzed via Western blotting. NlpI levels were also measured in all the strains used. MepS are used as a positive control to confirm the NlpI complementation because it is known to accumulate in the absence of NlpI (23). FtsZ was used as a loading control. Bar diagrams indicate the relative quantification of respective protein levels from three replicates; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001; ns (not significant); n = 3.

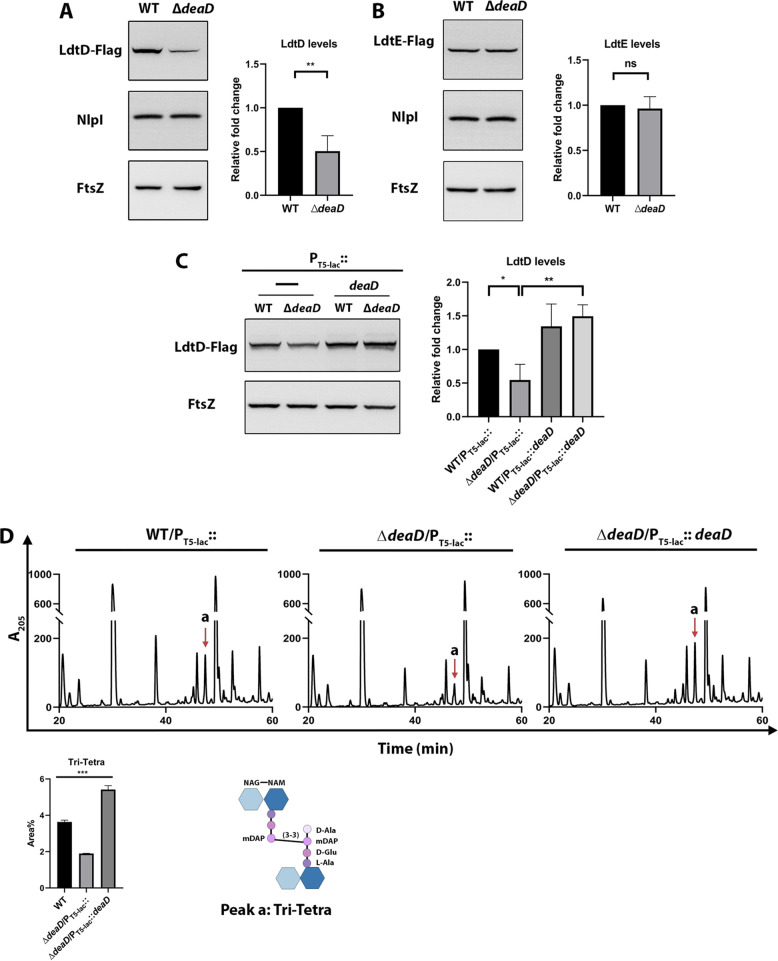

DeaD modulated the abundance of 3-3 cross-links.

DeaD is a cold-inducible RNA helicase that is vital for growth at lower temperatures (26). It has been shown that DeaD is involved in the small subunit assembly of the ribosome and in unwinding the RNAs with complex secondary structures to facilitate their translation (27, 28). To check whether the absence of DeaD affected the expression of LDTs, we probed their levels in a ΔdeaD mutant. The absence of DeaD indeed decreased LdtD levels but not the levels of LdtE (Fig. 4A and B). Additionally, low levels of LdtD in ΔdeaD mutants were restored by a plasmid-borne copy of DeaD (Fig. 4C), confirming its role in the modulation of LdtD levels.

FIG 4.

DeaD modulated LdtD levels and 3-3 cross-linkages in the PG sacculi. Western blots showing levels of (A) LdtD-Flag or (B) LdtE-Flag in the WT and ΔdeaD strain backgrounds. (C) Western blot of LdtD-Flag in the WT and ΔdeaD carrying the empty vector (pCA24N) or vector carrying the deaD gene (pCA24N-deaD) grown in the presence of 50 μM IPTG. FtsZ and NlpI were used as controls. Bar diagrams represent the respective quantified protein levels. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ns (not significant); n = 3. (D) HPLC chromatogram profile of the WT and ΔdeaD mutant carrying the empty vector (pCA24N) and that of ΔdeaD mutant with pCA24N-deaD. Strains were grown in LB supplemented with 50 μM IPTG and 15 μg/mL of Cm until an OD600 of 1.0. PG analysis was done as described in Materials and Methods. Peak “a” was identified by mass-spectrometric analysis and its structure is depicted. The graph represents the average peak-area% of Tri-Tetra muropeptide species. ***, P < 0.001; ns (not significant); n = 3.

As deaD deletion decreased the abundance of LdtD, next, we examined the abundance of 3-3 cross-links in these mutants by analyzing their PG composition. For this purpose, PG sacculi from WT and ΔdeaD mutants were isolated and digested with mutanolysin (a commercially available muramidase from Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and the resulting soluble muropeptides were separated by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). Analysis of the chromatograms indicated that a muropeptide peak eluting at 47 min was reduced ~50% in the ΔdeaD mutant (Fig. 4D). Tandem mass spectrometry analysis allowed us to identify this muropeptide peak to be a dimer of a disaccharide tripeptide and a disaccharide tetrapeptide (Tri-Tetra) cross-linked through their mDAP residues (3-3 cross-links). Moreover, ectopic expression of a plasmid-borne DeaD in the ΔdeaD mutant restored the level of Tri-Tetra cross-links to that of the WT (Fig. 4D). To summarize, the above results showed that DeaD modulates LdtD levels and, thereby, 3-3 cross-links in E. coli.

DeaD increases the effective translation of LdtD.

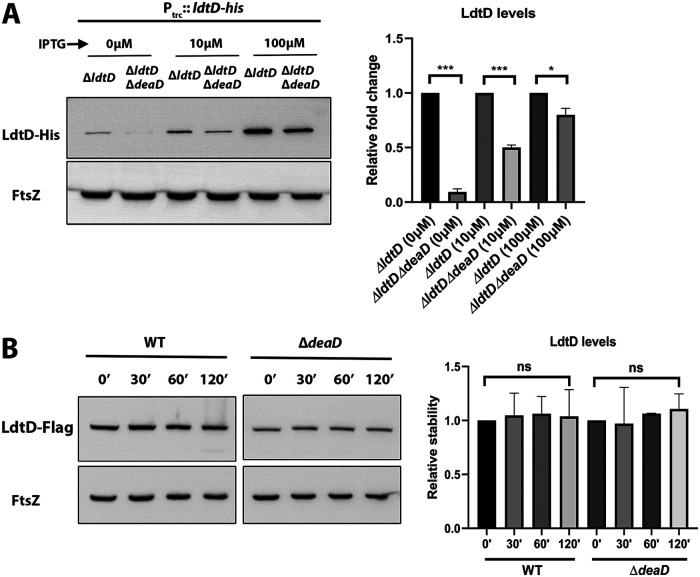

DeaD is an RNA helicase that unwinds inhibitory secondary structures of certain mRNAs facilitating their translation (27, 28). An earlier study predicted the propensity of LdtD mRNA to form RNA G-quadruplex structures, which are known to hinder its effective translation (32). Therefore, we hypothesized that DeaD, being an RNA helicase, may facilitate the translation of LdtD mRNA by unwinding its secondary structures. To test this hypothesis, we used a plasmid-borne ldtD-His construct lacking the native promoter and the ribosome binding site (as described in Supplemental File 1). This clone was introduced into ΔldtD or the ΔldtDΔdeaD double mutant, and LdtD-His levels were examined. Fig. 5A shows that the level of LdtD-His was much lower in the ΔdeaD mutant compared to the WT, showing that DeaD-mediated regulation of LdtD was independent of its upstream cis-regulatory elements. These results agreed with the existence of complex secondary structures in LdtD mRNA (32).

FIG 5.

DeaD is required for efficient translation of LdtD. (A) Western blot showing LdtD-His levels in ΔldtD or ΔldtDΔdeaD strains carrying pTrc99a-ldtD–His plasmid. Strains were grown in LB supplemented with IPTG (0, 10, or 100 μM) until an OD600 of 1.0, and normalized cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting. (B) Western blot showing posttranslational stability of LdtD-Flag. In rapidly growing WT or ΔdeaD cells at an OD600 0.6, 300 μg/mL spectinomycin was added to block the protein synthesis. Fractions were collected at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min post-antibiotic treatment, and normalized cell extracts were analyzed through Western blotting, as described in Materials and Methods. FtsZ was used as a loading control. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001; ns (not significant); n = 3.

In addition, we examined whether DeaD conferred any transcriptional control on LdtD expression by constructing a promoter fusion (PldtD::lacZ) at its native locus (as described in Supplemental File 1). Measurement of the beta-galactosidase levels in the WT and ΔdeaD mutant strains showed no significant difference between them (Fig. S2 in Supplemental File 1), confirming that DeaD did not exert regulation at the transcriptional level. Further, to examine whether DeaD had any effect on the post-translational stability of LdtD, we determined the half-life of LdtD in the presence and absence of DeaD. For this purpose, a spectinomycin-chase experiment was done in which cells were treated with spectinomycin (an inhibitor of prokaryotic translation) followed by a Western blot. The data in Fig. 5B indicated that the half-life of LdtD was not significantly altered in ΔdeaD mutant compared to the WT. Notably, the half-life of LdtD was found to be high with no significant degradation until 120 min post-spectinomycin treatment. Overall, these results showed that DeaD was required for the efficient translation of LdtD but not for its transcription or post-translational stability.

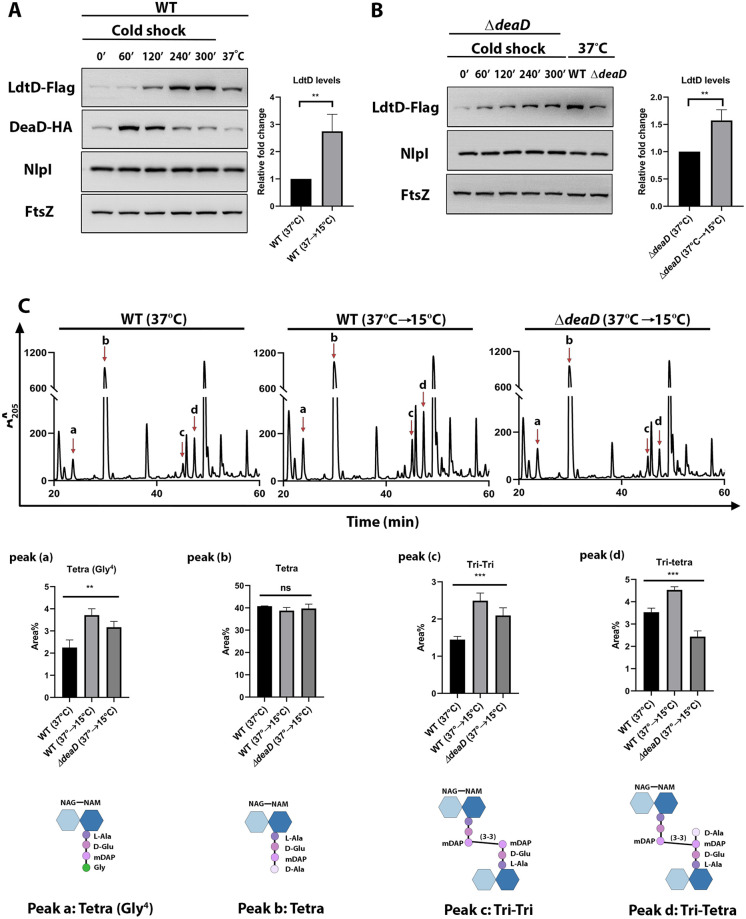

Abundance of 3-3 cross-links was higher during cold shock.

As DeaD is shown to be induced upon cold shock (26), we speculated that cold shock may also elevate the cellular LdtD levels. To address this, we measured the amount of LdtD in both WT and ΔdeaD mutants subjected to cold shock (as described in reference (26)). We observed a ~2 to 2.5-fold increase in LdtD levels of WT upon cold shock in comparison to the cells grown continuously at 37°C (Fig. 6A). However, a small increase in LdtD was also observed in ΔdeaD mutant upon cold shock (Fig. 6B), implying a minor DeaD-independent regulation of LdtD. These results encouraged us to examine the PG composition of WT cells subjected to cold shock. Therefore, the PG sacculi of exponentially growing WT and ΔdeaD mutant cells subjected to cold shock were isolated and their muropeptide composition was analyzed. The HPLC chromatograms indicated several changes (Fig. 6C), among which a significant increase was observed in the peaks containing muropeptides with 3-3 cross-links (peak c, Tri-Tri; peak d, Tri-Tetra). In addition, an increase in peak ‘a’ (Tetra-Gly4), a glycine-incorporated muropeptide species (a hallmark of LDT activity), was observed during cold shock. At the same time, the PG of ΔdeaD mutant did not display such a degree of change (Fig. 6C). To summarize the above results, cold shock induced the formation of 3-3 cross-links through an increased translation of LdtD mRNA by DeaD.

FIG 6.

Effect of cold shock on LdtD levels and composition of PG. (A) Western blot indicating LdtD-Flag and DeaD-HA levels of WT during cold shock. WT strain carrying both LdtD-Flag and DeaD-HA constructs was subjected to cold shock (as described in Materials and Methods) and fractions were collected at indicated intervals until an OD600 of 1.0 and normalized cell extracts were analyzed (lanes1 to 5). Lane 6 has cell extract of the WT continuously incubated at 37°C. The relative fold change of LdtD-Flag levels between lanes 5 and 6 is shown in the bar diagram. DeaD-HA served as a positive control, whereas FtsZ was used as a loading control. NlpI levels remained unaltered during cold shock. (B) Western blot indicating LdtD-Flag levels in a deaD deletion mutant. ΔdeaD mutant carrying LdtD-Flag subjected to cold shock was analyzed as described above (lanes 1 to 5). Lanes 6 and 7 had extracts of the WT and ΔdeaD grown continuously at 37°C. The values obtained from lanes 5 and 7 were used for comparison. (C) HPLC chromatograms of WT and ΔdeaD strains subjected to cold shock. Cells were grown, PG sacculi were isolated, and digested with mutanolysin and soluble muropeptides were resolved using HPLC. Peaks a, b, c, and d were analyzed further as described in Materials and Methods. Peaks a, c, and d showed a significant increase during cold shock, whereas peak b is unaltered. Bar diagrams represent the average peak area percentage of respective muropeptide species in the chromatogram. The molecular structures of the analyzed peaks are shown. **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001; ns (not significant); n = 3.

Because the 3-3 cross-links were upregulated during cold shock, we next examined whether they conferred an advantage during cold growth or survival. However, preliminary experiments did not show any significant difference in the growth rate or survival between WT and a mutant lacking LdtD and −E (ΔldtDE) when grown continuously at 15°C or under cold shock conditions (unpublished data).

Absence of DeaD conferred sensitivity to cell wall antibiotics.

Earlier high-throughput studies indicated that DeaD regulon consists of several genes involved in cell wall synthesis and cell division (33), and the mutants lacking DeaD are mildly sensitive to a β-lactam antibiotic cefsulodin (34). Therefore, we examined whether the absence of DeaD conferred sensitivity to any of the cell wall antibiotics, including cefsulodin, cephalexin, and vancomycin. The data in Fig. S3 in Supplemental File 1 showed that the deaD mutant was moderately sensitive to all of these cell wall antibiotics but not to others, such as chloramphenicol and rifampicin, suggesting DeaD may modulate several PG metabolic processes.

DISCUSSION

In E. coli, the stem peptides in PG are mostly linked by two types of cross-linkages, 4-3 and 3-3. Among these, the 4-3 cross-links are predominant and are essential for envelope integrity and cell viability. In contrast, 3-3 cross-links are minor and not essential for cell growth. However, they are implicated in conferring stability and rigidity to PG in the stationary phase or conditions of stress (3, 10–12). Here, we showed that cold shock increased the frequency of 3-3 cross-links in E. coli by increasing a major L,D-transpeptidase, LdtD, which catalyzes the 3-3 cross-link formation. We find that DeaD, a cold-inducible RNA helicase mediates the upregulation of LdtD not only during cold-shock but also contributes to the maintenance of LdtD levels during growth at ambient temperature. In summary, our study finds that PG of E. coli undergoes remodelling at low temperature signifying its role in the survival of bacteria encountering stressful environmental conditions such as cold-stress.

Multitier regulation of LdtD.

Several factors modulate 3-3 cross-link formation. For example, during envelope stress, a two-component system CpxA-CpxR upregulates the transcription of LdtD (10–12). Defective LPS transport has also been shown to induce PG remodeling via the upregulation of LdtD through CpxA-CpxR (12). Further, LdtE is upregulated by stationary-phase specific transcription factor σS (RpoS) (12, 13). Here, we found that LdtD was additionally regulated at the level of translation by an RNA helicase, DeaD, probably by unwinding inhibitory secondary structures located in the CDS region of LdtD mRNA (Fig. 4C and 5A). Moreover, we found that LdtD exhibited growth-phase dependent regulation, i.e., cells in the stationary phase had higher LdtD levels in comparison to the cells in the exponential phase, which was independent of DeaD (Fig. S2B in Supplemental File 1). This growth-phase mediated increase is consistent with the previous reports of increased 3-3 cross-links in the stationary phase (3), although it is not clear how LdtD is modulated during the stationary phase. The above observations indicate that LdtD is regulated both at the level of transcription and translation by several cellular/environmental factors, highlighting the role of 3-3 cross-links in the maintenance of envelope integrity.

Role of DeaD in PG remodeling.

DeaD was initially discovered as a suppressor of ΔrpsB mutant, a gene that codes for the S2 protein of the smaller subunit in the bacterial ribosome (35). Later, DeaD was shown to be a cold-inducible RNA helicase, essential for growth at low temperatures. It is upregulated during cold shock and is shown to participate in several processes such as translation initiation, gene regulation, mRNA stability, and biogenesis of ribosomes (26, 27, 36, 37). DeaD has also been shown to facilitate the effective translation of UvrY mRNA in E. coli growing at ambient temperature by resolving the stem-loop structures present in its mRNA (28). Akin to this situation, our results also showed that DeaD was required for the translation of LdtD mRNA at 37°C (Fig. 4A and C; Fig. 5A). These results imply that the basal level of DeaD made at 37°C facilitates the translation of certain mRNAs, whereas during the cold shock DeaD is upregulated, further increasing the translation efficiency indicating its role across a broad range of temperatures. In addition, deaD deletion mutants being susceptible to several cell wall antibiotics (Fig. S3 in Supplemental File 1) imply the existence of other cellular substrates of DeaD, which function in PG metabolism.

Cold shock-modulated PG composition in E. coli.

It is long known that temperature alters the structure and composition of the bacterial cell membrane (38). However, the effect of temperature on cell wall composition is not known. Biochemical analysis showed clearly that a shift to low temperature induced several alterations in the PG sacculi of E. coli, including a 2-fold increase in the 3-3 cross-link frequency (Fig. 6C). It is known that the frequency of 3-3 cross-links increases and strengthens the cell wall during envelope stress and stationary phase (3, 10, 12). In addition, an earlier global proteomics study showed that E. coli subjected to cold shock has elevated levels of several cell wall hydrolases and synthases (37), highlighting the importance of PG remodeling in cold stress. Nevertheless, in our preliminary experiments, the absence of 3-3 cross-links did not show any significant effect on growth or survival at 37°C, 15°C, or during cold shock indicating the possible existence of other PG factors contributing to the cold survival. However, further studies are required to understand the physiological significance of 3-3 cross-links in cells growing in different environmental conditions.

Deletion of nlpI was polar on the downstream gene deaD.

This study was initiated to examine whether NlpI regulates 3-3 cross-link formation as we observed overexpression of LdtD or −E alleviating the nlpI’s LBONS phenotype (Fig. 2A and B). However, detailed studies revealed that deletion of nlpI is polar on the expression of downstream gene deaD, which has a regulatory role in maintaining the LdtD levels (Fig. 3F and 4C). In this context of the polarity effect, we suggest that the nlpI phenotypes reported earlier be reevaluated. In addition, the data in Fig. 3B and D indicated the LdtE levels were partly controlled by NlpI. However, the molecular basis of this regulation is currently not clear.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Medium, bacterial strains, and plasmids.

Bacteria were grown primarily in Lysogeny Broth (LB; 0.5% yeast extract, 1% tryptone, and 1% NaCl) unless otherwise mentioned. LBON is LB without NaCl. Nutrient agar has 0.5% peptone and 0.3% beef extract. Antibiotic concentrations used in this study are as follows in μg/mL: kanamycin (kan), 50; ampicillin (amp), 50; chloramphenicol (cm), 15. Genes that were downstream of either trc or T5-lac promoters were induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) (Sigma-Aldrich). Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Supplemental File 1.

Strain and plasmid constructions.

Strain and plasmid constructions are described in detail in Supplemental File 1. C-terminal Flag and HA epitope tagging were done as described earlier (39).

Growth conditions.

Strains were normally grown at 37°C unless otherwise indicated. Cells were subjected to cold shock as described earlier (26). Briefly, cells grown overnight at 37°C were subcultured with 1:100 dilution into two separate flasks and allowed to grow until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4 at 37°C. At this point, one flask is shifted to 15°C and grown until cells reached an OD600 of 1.0 (approximately 5 h of growth). Another flask continuously incubated at 37°C until cells reached OD600 of 1.0 served as a control. Cells were collected at regular intervals for Western blotting, whereas for isolation of PG sacculi, cells were collected after 5 h of continuous growth at 15°C.

Viability assays and microscopy.

Viability assays were done by growing cells overnight and serially diluting them from 10−2 to 10−6. From each dilution, 4 μL were spotted onto the indicated plates and incubated for 20 to 24 h at 37°C. For microscopy, cells were collected and immobilized onto 1% agarose pads and subsequently visualized under a Zeiss Axioimager microscope in differential interference contrast (DIC) mode (Nomarski optics).

Molecular and genetic techniques.

The construction of plasmids and recombinant DNA was done as described (40). Genomic DNA from the MG1655 strain was used as the template for PCR amplification. All constructed plasmids and strains were confirmed through sequencing. P1 transductions and transformations were done following standard protocols as described earlier (41). All strains are derivatives of MG1655 unless otherwise mentioned. Deletion mutations were sourced from Keio collection (NBRP, Japan; (42)) and were transferred by P1-mediated transductions. The antibiotic marker was flipped out using plasmid-borne (pCP20) flippase.

β-galactosidase assay.

β-Galactosidase assays were done as described (41). Overnight cultures of the strains were subcultured in fresh medium and grown until OD600 of 0.6 to 0.8 was reached. To 0.1 to 0.5 mL of the culture, Z-buffer was added to a final volume of 1 mL, and the cells were lysed by adding 2 drops of chloroform and 1 drop of 1% SDS. O-nitrophenyl-beta-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG; 200 μL from a 4 mg/mL stock made in Z-buffer) was added and the initial time was noted. The tubes were left at room temperature and when the solution turned yellow, the reaction was terminated by adding 0.5 mL of 1 M Na2CO3, and the final time was noted. The absorbance of the reactions was recorded at 420 nm and 550 nm and of the cultures at 600 nm. The enzyme-specific activity (expressed in Miller Units) was calculated as described (41).

Western blotting.

Cells were grown and harvested by centrifugation at 3500 × g for 2 min. Cell pellets were dissolved in Laemmli buffer (40) and boiled for 10 min. An equal number of samples was loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE. Further, proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (0.45 μm Amersham Hybond) using cytivia TE 77 semidry blotter apparatus at a constant current of 70 A for 1 h. Post transfer, the blot was stained with Ponceau to visualize the transfer efficiency. The membrane was washed with TBST (TBS with 1% Tween 20) for 5 min and was then blocked with 5% skimmed milk (Blotto-2324, made in TBST) for 1 h at RT. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (1:10,000 for α-NlpI, 1:3,000 for α-His, 1:5000 for α-FLAG, and α-HA, 1:50,000 for α-FtsZ, and 1:5000 for α-MepS) made in 5% skimmed milk and washed 5 times with TBST for 5 min each to remove unbound antibodies. The membrane was then incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody tagged with HRP (horse-radish peroxidase) for 1 h (1:10,000 for anti-rabbit HRP and 1:5000 for anti-mouse HRP) and washed again 5 times with TBST for 5 min. The blot was developed using chemiluminescence (SuperSignal, Thermo Scientific, 34580). The bands were captured using Vilber lourmat chemiluminescence capture apparatus and quantified through ImageJ software.

Anti-Flag (mouse), and anti-His (rabbit) primary antibodies were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with HRP were procured from Invitrogen. Anti-HA was sourced from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-NlpI and anti-MepS primary antibodies (rabbit) are from the lab collection. Anti-FtsZ (rabbit) was a kind gift from Joe Lutkenhaus (Kansas University, USA).

Preparation of PG sacculi.

Isolation of PG sacculi was done as described earlier with slight modifications (3). Cells were grown until the required OD and harvested by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in ice-cold water and added dropwise to an equal volume of boiling 8% SDS and further allowed to boil for 1 h. The boiled suspension was allowed to cool overnight at RT. The suspension was diluted with deionized water and subjected to ultracentrifugation (3,00,000 × g, 50 min, RT). Pellet was repeatedly washed until SDS is removed. The presence of SDS was checked as described earlier (43). After SDS removal, the pellet was treated with 0.1 mg/mL of α-amylase (2 h at 37°C) and subsequently with predigested pronase (0.2 mg/mL, 90 min at 60°C) to remove high molecular weight glycogen and lipoprotein bound to PG, respectively. The enzymes were inactivated by boiling in an equal volume of 8% SDS for 20 min. The suspension was again diluted with water and subjected to ultracentrifugation. Pellet was washed until SDS is completely removed, resuspended in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, and stored at −30°C for further use.

Analysis of PG muropeptides.

HPLC analysis was done as described earlier with slight modifications (3, 22). To obtain soluble muropeptides, PG sacculi were treated with 10 U of mutanolysin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) for 16 h with constant stirring. Samples were centrifuged (10000 × g, 10 min, room temperature [RT]) and the supernatant containing soluble muropeptides was collected. The muropeptides were then reduced with ~1 mg of sodium borohydride in 50 mM sodium-borate buffer (pH 9.0) for 30 min. Excess borohydride was destroyed by adding 20% ortho-phosphoric acid and pH is adjusted to 3 to 4. Particulate matter is removed by a centrifugation step before being loaded onto a preheated (55°C) Zorbax 300SB RP-C18 column connected to an Agilent technologies RRLC 1200 HPLC machine. Muropeptides were eluted using a 1 to 10% gradient of acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoro acetic acid with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min for 120 min. Muropeptides were detected at 205 nm and subsequently identified using mass spectrometry (MS) and MS/MS analysis.

Mass spectrometry analysis of muropeptides.

Muropeptide fractions collected during HPLC were dried and dissolved in 5% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid and loaded onto a reverse phase PepMapTM RSLC-C18 column (3 μm, 100 Å, 75 μm x 15 cm) connected to Q-ExactiveTM HF Hybrid Quadrupole-OrbitrapTM mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Peaks were analyzed by MS and tandem MS and muropeptide structures were deciphered based on the molecular mass of the fragments.

Statistical analysis.

Experiments were performed at least three times, and significance was calculated. Error bars in the graphs are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical difference between the two samples was calculated using unpaired Student's t test whereas for comparison between more than two samples one-way ANOVA was performed. In all the figures, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; and ***, P < 0.001.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank National BioResource Project (NBRP) for the E. coli Keio collection and ASKA plasmid library; B Raman for mass spectrometry analysis; Anubhav Bhardwaj for the LdtD-Flag construction; Krishna Sree GB, Balaji Venkataraman for help with microscopy and members of MR lab for critical suggestions.

This work is supported by funds from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (MLP0141) and Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology (BT/PR33064/BRB/10/1819/2019), Govt of India (to MR). We acknowledge financial support from CSIR to KCN.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Manjula Reddy, Email: manjula@ccmb.res.in.

Conrad W. Mullineaux, Queen Mary University of London

REFERENCES

- 1.Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. 2010. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000414. 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidel W, Pelzer H. 1964. Bagshaped macromolecules-a new outlook on bacterial cell walls, p 193–232. In Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glauner B, Höltje JV, Schwarz U. 1988. The composition of the murein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 263:10088–10095. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)81481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Höltje J-V. 1998. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62:181–203. 10.1128/MMBR.62.1.181-203.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vollmer W, Blanot D, De Pedro MA. 2008. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:149–167. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garde S, Chodisetti PK, Reddy M. 2021. Peptidoglycan: structure, synthesis, and regulation. EcoSal Plus 9. 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0010-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauvage E, Kerff F, Terrak M, Ayala JA, Charlier P. 2008. The penicillin-binding proteins: structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:234–258. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magnet S, Dubost L, Marie A, Arthur M, Gutmann L. 2008. Identification of the l,d-Transpeptidases for Peptidoglycan Cross-Linking in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 190:4782–4785. 10.1128/JB.00025-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cava F, de Pedro MA, Lam H, Davis BM, Waldor MK. 2011. Distinct pathways for modification of the bacterial cell wall by non-canonical D-amino acids. EMBO J 30:3442–3453. 10.1038/emboj.2011.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernal-Cabas M, Ayala JA, Raivio TL. 2015. The Cpx envelope stress response modifies peptidoglycan cross-linking via the l,d-transpeptidase LdtD and the novel protein YgaU. J Bacteriol 197:603–614. 10.1128/JB.02449-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delhaye A, Collet J-F, Laloux G. 2016. Fine-tuning of the cpx envelope stress response is required for cell wall homeostasis in Escherichia coli. mBio 7:e00047-16–e00016. 10.1128/mBio.00047-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morè N, Martorana AM, Biboy J, Otten C, Winkle M, Serrano CKG, Montón Silva A, Atkinson L, Yau H, Breukink E, den Blaauwen T, Vollmer W, Polissi A. 2019. Peptidoglycan remodeling enables Escherichia coli to survive severe outer membrane assembly defect. mBio 10:e02729-18. 10.1128/mBio.02729-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber H, Polen T, Heuveling J, Wendisch VF, Hengge R. 2005. Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response network in Escherichia coli: sigmaS-dependent genes, promoters, and sigma factor selectivity. J Bacteriol 187:1591–1603. 10.1128/JB.187.5.1591-1603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quintela JC, De Pedro MA, Zöllner P, Allmaier G, Garcia-del Portillo F. 1997. Peptidoglycan structure of Salmonella typhimurium growing within cultured mammalian cells. Mol Microbiol 23:693–704. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2561621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernández SB, Castanheira S, Pucciarelli MG, Cestero JJ, Rico-Pérez G, Paradela A, Ayala JA, Velázquez S, San-Félix A, Cava F, Portillo FG. 2022. Peptidoglycan editing in non-proliferating intracellular Salmonella as source of interference with immune signaling. PLoS Pathog 18:e1010241. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mainardi J-L, Morel V, Fourgeaud M, Cremniter J, Blanot D, Legrand R, Fréhel C, Arthur M, van Heijenoort J, Gutmann L. 2002. Balance between two transpeptidation mechanisms determines the expression of β-lactam resistance in Enterococcus faecium. J Biol Chem 277:35801–35807. 10.1074/jbc.M204319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hugonnet J-E, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Monton A, den Blaauwen T, Carbonnelle E, Veckerlé C, Brun YV, van Nieuwenhze M, Bouchier C, Tu K, Rice LB, Arthur M. 2016. Factors essential for L,D-transpeptidase-mediated peptidoglycan cross-linking and β-lactam resistance in Escherichia coli. Elife 5:e19469. 10.7554/eLife.19469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montón Silva A, Otten C, Biboy J, Breukink E, VanNieuwenhze M, Vollmer W, den Blaauwen T. 2018. The fluorescent d-amino acid NADA as a tool to study the conditional activity of transpeptidases in Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 9:2101. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanders AN, Pavelka MSY. 2013. Phenotypic analysis of Eschericia coli mutants lacking l,d-transpeptidases. Microbiology (Reading) 159:1842–1852. 10.1099/mic.0.069211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chodisetti PK, Reddy M. 2019. Peptidoglycan hydrolase of an unusual cross-link cleavage specificity contributes to bacterial cell wall synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:7825–7830. 10.1073/pnas.1816893116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atze H, Liang Y, Hugonnet J-E, Gutierrez A, Rusconi F, Arthur M. 2022. Heavy isotope labeling and mass spectrometry reveal unexpected remodeling of bacterial cell wall expansion in response to drugs. Elife 11:e72863. 10.7554/eLife.72863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh SK, SaiSree L, Amrutha RN, Reddy M. 2012. Three redundant murein endopeptidases catalyse an essential cleavage step in peptidoglycan synthesis of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Microbiol 86:1036–1051. 10.1111/mmi.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh SK, Parveen S, SaiSree L, Reddy M. 2015. Regulated proteolysis of a cross-link-specific peptidoglycan hydrolase contributes to bacterial morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:10956–10961. 10.1073/pnas.1507760112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su M-Y, Som N, Wu C-Y, Su S-C, Kuo Y-T, Ke L-C, Ho M-R, Tzeng S-R, Teng C-H, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Reddy M, Chang C-I. 2017. Structural basis of adaptor-mediated protein degradation by the tail-specific PDZ-protease Prc. Nat Commun 8:1516. 10.1038/s41467-017-01697-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banzhaf M, Yau HC, Verheul J, Lodge A, Kritikos G, Mateus A, Cordier B, Hov AK, Stein F, Wartel M, Pazos M, Solovyova AS, Breukink E, van Teeffelen S, Savitski MM, den Blaauwen T, Typas A, Vollmer W. 2020. Outer membrane lipoprotein NlpI scaffolds peptidoglycan hydrolases within multi-enzyme complexes in Escherichia coli. EMBO J 39:e102246. 10.15252/embj.2019102246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones PG, Mitta M, Kim Y, Jiang W, Inouye M. 1996. Cold shock induces a major ribosomal-associated protein that unwinds double-stranded RNA in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:76–80. 10.1073/pnas.93.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butland G, Krogan NJ, Xu J, Yang W-H, Aoki H, Li JS, Krogan N, Menendez J, Cagney G, Kiani GC, Jessulat MG, Datta N, Ivanov I, Abouhaidar MG, Emili A, Greenblatt J, Ganoza MC, Golshani A. 2007. Investigating the in vivo activity of the DeaD protein using protein-protein interactions and the translational activity of structured chloramphenicol acetyltransferase mRNAs. J Cell Biochem 100:642–652. 10.1002/jcb.21016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vakulskas CA, Pannuri A, Cortés-Selva D, Zere TR, Ahmer BM, Babitzke P, Romeo T. 2014. Global effects of the DEAD-box RNA helicase DeaD (CsdA) on gene expression over a broad range of temperatures. Mol Microbiol 92:945–958. 10.1111/mmi.12606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohara M, Wu HC, Sankaran K, Rick PD. 1999. Identification and characterization of a new lipoprotein, NlpI, in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 181:4318–4325. 10.1128/JB.181.14.4318-4325.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitagawa M, Ara T, Arifuzzaman M, Ioka-Nakamichi T, Inamoto E, Toyonaga H, Mori H. 2005. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K -12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res 12:291–299. 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ojha S, Jain C. 2020. Dual-level autoregulation of the E. coli DeaD RNA helicase via mRNA stability and Rho-dependent transcription termination. RNA 26:1160–1169. 10.1261/rna.074112.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao X, Zhang W, Umar MI, Wong HY, Seng Z, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Yang L, Kwok CK, Deng X. 2020. RNA G-Quadruplex Structures Mediate Gene Regulation in Bacteria. mBio 11:e02926-19. 10.1128/mBio.02926-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phadtare S. 2012. Escherichia coli cold-shock gene profiles in response to over-expression/deletion of CsdA, RNase R and PNPase and relevance to low-temperature RNA metabolism. Genes Cells 17:850–874. 10.1111/gtc.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nichols RJ, Sen S, Choo YJ, Beltrao P, Zietek M, Chaba R, Lee S, Kazmierczak KM, Lee KJ, Wong A, Shales M, Lovett S, Winkler ME, Krogan NJ, Typas A, Gross CA. 2011. Phenotypic landscape of a bacterial cell. Cell 144:143–156. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toone WM, Rudd KE, Friesen JD. 1991. deaD, a new Escherichia coli gene encoding a presumed ATP-dependent RNA helicase, can suppress a mutation in rpsB, the gene encoding ribosomal protein S2. J Bacteriol 173:3291–3302. 10.1128/jb.173.11.3291-3302.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charollais J, Dreyfus M, Iost I. 2004. CsdA, a cold-shock RNA helicase from Escherichia coli, is involved in the biogenesis of 50S ribosomal subunit. Nucleic Acids Res 32:2751–2759. 10.1093/nar/gkh603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Burkhardt DH, Rouskin S, Li G-W, Weissman JS, Gross CA. 2018. A stress response that monitors and regulates mRNA structure is central to cold shock adaptation. Mol Cell 70:274–286.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marr AG, Ingraham JL. 1962. Effect of temperature on the composition of fatty acids in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 84:1260–1267. 10.1128/jb.84.6.1260-1267.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uzzau S, Figueroa-Bossi N, Rubino S, Bossi L. 2001. Epitope tagging of chromosomal genes in Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:15264–15269. 10.1073/pnas.261348198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green MR, Sambrook J, Sambrook J. 2012. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 4th ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller JH. 1992. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics – A Laboratory Manual and Handbook for Escherichia coli and Related Bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. 2006.0008. 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi K. 1975. A rapid determination of sodium dodecyl sulfate with methylene blue. Anal Biochem 67:503–506. 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental text, Tables S1 to S3, and Fig. S1 to S3. Download jb.00382-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.4 MB (458.3KB, pdf)