Abstract

Down syndrome (DS), the most frequent chromosomic aberration, results from the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 21. The identification of genes which overexpression contributes to intellectual disability (ID) in DS is important to understand the pathophysiological mechanisms involved and develop new pharmacological therapies. In particular, gene dosage of Dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation Regulated Kinase 1A (DYRK1A) and of Cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) are crucial for cognitive function. As these two enzymes have lately been the main targets for therapeutic research on ID, we sought to decipher the genetic relationship between them. We also used a combination of genetic and drug screenings using a cellular model overexpressing CYS4, the homolog of CBS in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, to get further insights into the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of CBS activity. We showed that overexpression of YAK1, the homolog of DYRK1A in yeast, increased CYS4 activity whereas GSK3β was identified as a genetic suppressor of CBS. In addition, analysis of the signaling pathways targeted by the drugs identified through the yeast-based pharmacological screening, and confirmed using human HepG2 cells, emphasized the importance of Akt/GSK3β and NF-κB pathways into the regulation of CBS activity and expression. Taken together, these data provide further understanding into the regulation of CBS and in particular into the genetic relationship between DYRK1A and CBS through the Akt/GSK3β and NF-κB pathways, which should help develop more effective therapies to reduce cognitive deficits in people with DS.

Keywords: CBS, DYRK1A, GSK3β, Akt, NF-κB, pharmacological inhibitor

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is the most frequent chromosomic aberration, with a prevalence of one in 650–1,000 live births worldwide. This genetic condition results from the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 21, as first described by Lejeune et al. (1959). The triplication of this chromosome and of its ∼225 genes leads to a complex phenotype that includes particular craniofacial features, hypotonia, cardiac, and digestive defects, high incidence of leukemia, early onset of Alzheimer’s disease and intellectual disability (ID). Although the detailed consequences of the overexpression of all these individual genes is difficult to assess, a few of them have been suggested to be of crucial importance in the development of certain phenotypic aspects (Antonarakis, 2017). Concerning ID, a few genes are considered as highly relevant candidates, among which the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) (Salehi et al., 2007), the Glutamate Receptor, Ionotropic, Kainate 1 (GRIK1) (Valbuena et al., 2019), the Regulator of CAlciNeurin 1 (RCAN1) (Dudilot et al., 2020) and the Dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-Regulated Kinase 1A (DYRK1A) (Altafaj et al., 2013; García-Cerro et al., 2014). So far, DYRK1A has been the main target for therapeutic research, leading to the identification of compounds that inhibit its protein kinase activity and are able to improve cognition in mouse models for DS (Guedj et al., 2009; De la Torre et al., 2014, 2016; Kim H. et al., 2016; Nakano-Kobayashi et al., 2017; Neumann et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2018). However, their efficiency in DS patients is limited, showing the need to combine multiple therapies to improve cognitive deficits and more generally the quality of life of DS patients.

More recently, studies of transgenic mouse models have revealed that the triplication of CBS gene also contributes to cognitive phenotypes and that CBS and DYRK1A show epistatic interactions (Maréchal et al., 2019). CBS encodes a pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the first reaction in the transsulfuration pathway. This pathway leads to the synthesis of cysteine and glutathione (GSH) at the expense of homocysteine and methionine (Jhee and Kruger, 2005). In the brain, CBS is also the major enzyme catalyzing the production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) from L-cysteine (Kimura, 2011) or from the condensation of homocysteine with cysteine (Chen et al., 2004). H2S is now considered as a major gasotransmitter in the brain, which plays a role in synaptic transmission (Kamat et al., 2015) and its increased production resulting from CBS triplication has been suggested to contribute to the cognitive phenotype of DS patients (Kamoun, 2001; Kamoun et al., 2003; Szabo, 2020). For this reason, the identification of pharmacological inhibitors of CBS has been an important field of research in the last 10 years. Unfortunately, most of the screening methods used were in vitro and have only led to the identification of compounds with relatively low potency and limited selectivity (Asimakopoulou et al., 2013; Thorson et al., 2013, 2015; Zhou et al., 2013; Druzhyna et al., 2016), suggesting that CBS may be difficult to target pharmacologically. We recently developed a new screening method based on the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae which allows the identification of drugs or genes that interfere with the phenotypical consequences of CYS4 (CBS homolog in yeast) overexpression. Using this method, we recently identified four molecules (disulfiram, chloroxine, clioquinol, and nitroxoline), all involved in metallic ion binding (Maréchal et al., 2019; Conan et al., 2022), which effect on CBS activity has been validated in different cellular models (Zuhra et al., 2020; Conan et al., 2022).

A genetic interaction between CBS and DYRK1A has been previously suggested in mouse (Tlili et al., 2013; Latour et al., 2015; Baloula et al., 2018; Maréchal et al., 2019) but the nature of this interaction was still undetermined. It was described as positive in certain studies and negative in others depending on the context or the organ (liver vs. brain). Here, we took advantage of our yeast-based model to explore the relationship between CBS and DYRK1A genes, which allowed us to confirm the positive regulation of Cbs activity by Dyrk1A. Next, we further investigated the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of CBS activity using a combined genetic and drug screening approach. Our results highlighted the importance of the Akt/GSK3β and the NF-κB pathways in the regulation of CBS activity and expression.

Materials and methods

Genetic and drug screening in S. cerevisiae

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1 and were cultured as previously described (Maréchal et al., 2019). Cultures in exponential growth phase, obtained by diluting overnight cultures and incubation for 4–5 h to reach OD600∼0.6–1, were used in all experiments. Subcloning of full-length cDNA of CYS4 in expression vectors of the pRS42X series was performed as previously described (Maréchal et al., 2019) using primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. To obtain a sufficient level of methionine auxotrophy, in all the figures presented (except Figure 1B, in which 2 centromeric plasmids were used), CYS4 overexpression was obtained through the transfection of two 2 μ vectors of the pRS42X series and the addition in the medium of serine (at a final concentration of 1.5 mM), a limiting substrate for Cys4p activity.

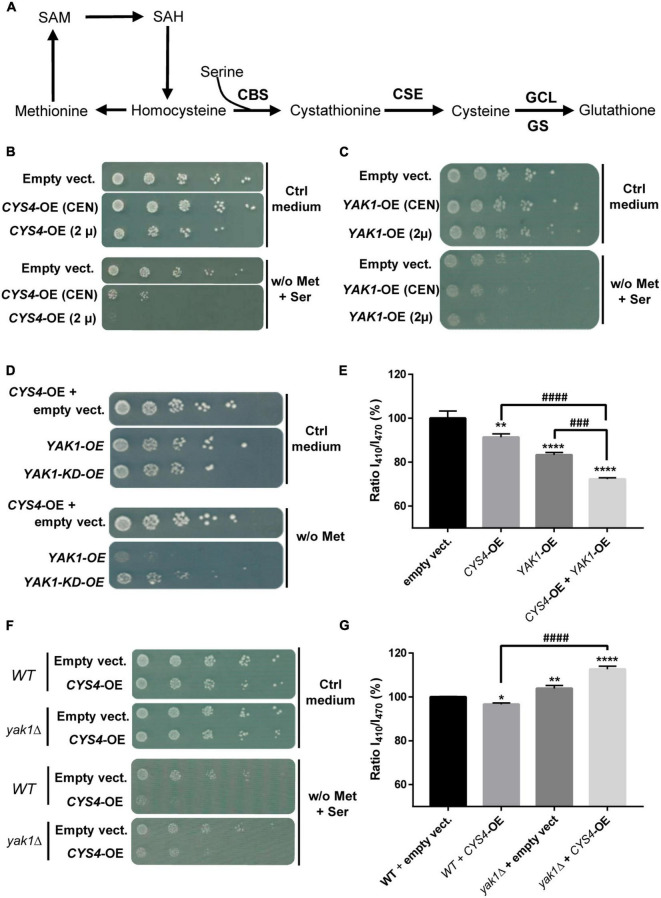

FIGURE 1.

Interaction between CYS4 and YAK1. (A) Simplified representation of the transsulfuration pathway. Yeast CYS4 gene encodes the cystathionine beta synthase protein (CBS) which converts homocysteine and serine into cystathionine. The other enzymes of the transsulfuration pathway are CSE, GCL (γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase), and GS (glutathione synthetase). CYS4/CBS overexpression would favor cysteine and glutathione synthesis at the expense of homocysteine and methionine. (B) Methionine auxotrophy of CYS4-overexpressing (CYS4-OE) cells. Methionine auxotrophy, revealed by the absence of growth on medium lacking methionine, was assessed by spotting serial dilutions of wild-type yeast cells transformed with two centromeric (CEN) or 2 μ plasmids either empty or containing full length CYS4, which expression in yeast is driven by the strong GPD promoter. The presence of a centromere segment (CEN) in plasmids enhances their mitotic stability but results in a lower copy number than 2 μ plasmids, thus producing less proteins. (C) Methionine auxotrophy of YAK1-OE cells. Similarly to CYS4-OE, YAK1-OE leads to methionine auxotrophy using either a single centromeric plasmid (CEN) or a single 2 μ plasmid. (D,E) Additive effect of YAK1-OE and CYS4-OE. (D) YAK1-OE (obtained with one single 2 μ plasmid) enhances methionine auxotrophy of CYS4-OE cells (obtained with two 2 μ plasmids). This effect depends on the kinase activity of YAK1 as a kinase dead form of YAK1 (YAK1-KD) was not able to strengthen CYS4-OE induced phenotype. Note that we used in these experiments a methionine-free medium without serine supplementation to be able to see stronger methionine auxotrophy than the one caused by CYS4-OE. (E) YAK1 and CYS4 overexpression have additive effects on cytosolic acidification. (F,G) YAK1 deletion prevents CYS4-OE induced phenotypes. (F) YAK1 deletion mitigates CYS4-OE induced methionine auxotrophy. (G) Similarly, CYS4-OE is not able to induce acidification defects in cells deleted for YAK1 suggesting that Yak1p is necessary for Cys4p activity. Note that YAK1 deletion even increases cytosolic pH, suggesting a decrease in GSH synthesis and/or the presence of oxidative stress which may deplete intracellular glutathione. (E,G) One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. Comparison with DMSO: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. Comparison between conditions: ###p < 0.001; ####p < 0.0001.

To test the genetic interaction between YAK1 and CYS4, the coding sequence of YAK1 was amplified from the genomic DNA of a W303 wild-type strain and subcloned into either a pRS416-GPD (centromeric plasmid) or a pRS426-GPD (2 μ) vector using primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. YAK1 overexpression was obtained through the transfection of only one vector of the pRS42X series (2 μ plasmids).

For the genetic screening, a yeast genomic DNA library (Lista et al., 2017) constructed by inserting ∼4 kb genomic DNA fragments (obtained by Sau3A partial digestion) at the unique BamHI site in the replicative 2 μ multicopy pFL44L vector containing URA3-marker, was transformed into a yeast strain overexpressing CYS4 (with pRS423 and pRS424 plasmids). Transformants were selected on solid minimal medium lacking tryptophan, histidine, uracil, and methionine and supplemented with 1.5 mM of serine. Plasmids originated from the pFL44L-based library were extracted and purified with the Zymoprep kit (Zymo Research), amplified in Escherichia coli and then retransformed into the yeast strain overexpressing CYS4 to confirm their ability to reverse methionine auxotrophy. The extremities of the confirmed clones were sequenced using primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. The coding sequences of genes obtained in the genetic screen were amplified from the pFL44L plasmids extracted from the library and subcloned into pRS426-TEF (2 μ) plasmids using primers listed in Supplementary Table 2, which introduced SmaI and XhoI restriction sites. Yeast deletion of MCK1 in the W303 background was performed by standard one-step gene replacement with PCR-generated cassettes (Longtine et al., 1998) using primers listed in Supplementary Table 2.

The YAK1-KD (kinase dead, p.K398R) and MCK1-KD (p.K68R) mutants were created by site-directed mutagenesis (QuickChange Lightning, Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer instructions using primers listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Drug screening was performed as previously described (Maréchal et al., 2019; Conan et al., 2022) using compounds obtained from the NIH from different sets: 166 FDA-approved Oncology Drugs (at a concentration of 10 mM in DMSO), 1,584 compounds of the NCI Diversity Set VI (at a concentration of 10 mM in DMSO), 811 compounds of the Mechanistic Set VI (at a concentration of 1 mM in DMSO) and 390 compounds of the Natural Products Set V (at a concentration of 10 mM in DMSO).

Determination of yeast cytosolic pH was performed as previously described (Conan et al., 2022) using a pRS416-ADH plasmid containing a pH-sensitive ratiometric GFP variant named pHluorin (kindly obtained from S. Léon, IJM, Paris).

Cell culture and drug treatment

The human liver cancer cell line HepG2 was obtained from ATCC and was cultured in DMEM glutamax high glucose medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen), in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 atmosphere.

All the molecules used in this study were either purchased from Merck or obtained from the NIH libraries and were resuspended in DMSO. For drug treatment, 20,000 HepG2 cells were plated in each well of a Greiner Bio-One black 96-well plate with transparent flat bottom in 100 μL of culture medium. The following day, cells were incubated for 24 or 48 h with selected drugs at indicated concentrations with a final concentration of 1% DMSO (v/v).

Measurement of H2S production in live cells

For HepG2 transfection, 250,000 cells were seeded per well in 6 well plates 24 h before transfection. Cells were then transfected with either the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) alone as a negative control or with GSK3β or DYRK1A cDNA using JetOptimus transfection reagent (Polyplus transfection, Illkirch, France) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The GSK3β plasmid was obtained from Addgene (#14754) and corresponds to a constitutively active enzyme (mutant p.S9A). Wild-type and mutant p.S324R and p.S311F DYRK1A plasmids were obtained from Courraud et al. (2021). These two mutations, located in the kinase domain of DYRK1A affect its kinase activity (Courraud et al., 2021). Fourty-eight or 72 h after transfection, H2S production was assessed as followed.

Following a 24 h-treatment, cells were washed once with 1× PBS and incubated for 2 h in a saline buffer (139 mM NaCl, 0.56 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM K2HPO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2 pH7.4 supplemented with 10 mM glucose) containing 100 μM of 7-Azido-4-Methylcoumarin (AzMC) fluorescent probe (Sigma Aldrich), which selectively reacts with H2S to form a fluorescent compound. Fluorescent AzMC signal acquisition (λEx = 365 nm and λEm = 450 nm) was performed on a Flexstation 3 microplate reader using the SoftMax Pro 5.4.5 software (Molecular Device, San Josa, CA, USA). Values were expressed as a percent of the corresponding controls.

Cell viability assessment

The cytotoxicity of all tested compounds was examined using the Cell Counting Kit WST-8/CCK8 (Abcam). Briefly, following the measurement of H2S levels, cells were washed once with 1× PBS and incubated for 2 h in the WST-8 reagent mixed in the culture medium according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance signal acquisition (at 450 nm) was performed on the Flexstation 3 microplate reader with SoftMax Pro 5.4.5 software (Molecular Device, San Josa, CA, USA). Values were expressed as a percent of the corresponding controls.

Western blot

HepG2 cells were treated for 24 or 48 h with selected drugs and were harvested in the following buffer: 150 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 with Protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Cell lysis was then performed by 6 cycles of vigorous vortexing and freeze-thawing. Protein amount in the supernatants was evaluated by classical Bradford method. Twenty micrograms of each sample were then loaded onto 10% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (precast NuPAGE, Invitrogen), and transferred onto 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Cytiva, Velizy-Villacoublay, France). Membranes were blocked during 1 h at room temperature in 1× PBS containing 0.1% Igepal and 5% milk and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti-CBS mouse monoclonal antibody (ab12476, Abcam, 1:1,000) and anti-α-tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody (T6793, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:10,000). The following day, membranes were washed with fresh 1× PBS with 0.1% Igepal and incubated for 45 min with gaot anti-mouse (ab6789, Abcam, 1:3,000) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at a 1:3,000 dilution, and analyzed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Cytiva) using a Vilbert-Lourmat Photodocumentation Chemistart 5000 imager.

RT-qPCR

HepG2 cells were treated for 24 h and RNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin RNA mini kit (Macherey-Nagel) and reverse transcribed using RT2 First Strand Kit (SA Biosciences) following the manufacturers’ instructions. Real-Time PCR was performed on an ABI PRISM® 7300 Sequence Detection System using RT2 SYBR Green ROX qPCR Mastermix (Qiagen). Expression levels were normalized across samples using the GAPDH or β-actin housekeeping genes. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Data analysis was done by the 2–ΔΔCt method and relative expression was calculated using DMSO condition as the reference sample (expression = 1). Significant differences were assessed by the unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA). Presented results in each figure represent data obtained in at least 3 independent experiments.

Results

Yak1p promotes Cys4p activity through its kinase activity

We first investigated the relationship between CBS and DYRK1A using an original yeast-based assay that we recently set-up to identify CBS inhibitors (Maréchal et al., 2019; Conan et al., 2022), and which is based on the overexpression of CYS4, the homolog of CBS in S. cerevisiae. Located at a metabolic hub, CBS/Cys4p converts homocysteine and serine into cystathionine (Figure 1A). As previously shown (Maréchal et al., 2019; Conan et al., 2022), CYS4-overexpression (OE) in yeast favors cysteine and glutathione synthesis at the expense of methionine and homocysteine (Figure 1A), leading to a decreased ability of yeast cells to grow without external supply of methionine (Figure 1B). This effect can be enhanced by the addition in the medium of serine, a substrate of the reaction, making this phenotype a convenient read-out that can be easily monitored and used for drug or genetic screening.

Similarly to what was observed for CYS4-OE, the overexpression of YAK1, the homolog of DYRK1A in S. cerevisiae, induced by itself methionine auxotrophy in a dose-dependent manner on medium supplemented with serine (Figure 1C). In addition, simultaneous YAK1-OE and CYS4-OE showed additive effect on methionine auxotrophy (Figure 1D). Yak1p activity appeared to be mediated by its kinase activity as its effect was lost when a kinase dead (KD) form p.K398R of YAK1 (Moriya et al., 2001) was used (Figure 1D). We previously identified cytosolic acidification as another phenotype specific to CYS4-OE (Conan et al., 2022). We show here that, similarly to CYS4-OE, YAK1-OE induced cytosolic acidification and that combined effect of CYS4-OE and YAK1-OE on cytosolic pH was additive (Figure 1E). On the opposite, YAK1 deletion partially rescued methionine auxotrophy due to CYS4-OE (Figure 1F). Similarly, yak1Δ cells showed increased cytosolic pH, suggestive of an absence of Cys4p activity as shown by Conan et al. (2022). Finally, CYS4-OE in a yak1Δ strain was unable to induce cytoplasmic acidification defects and even further accentuated cytosolic pH basification (Figure 1G). Taken together, these results suggest that Yak1p promotes Cys4p activity through its kinase activity and that, in the absence of Yak1p, Cys4p activity is reduced.

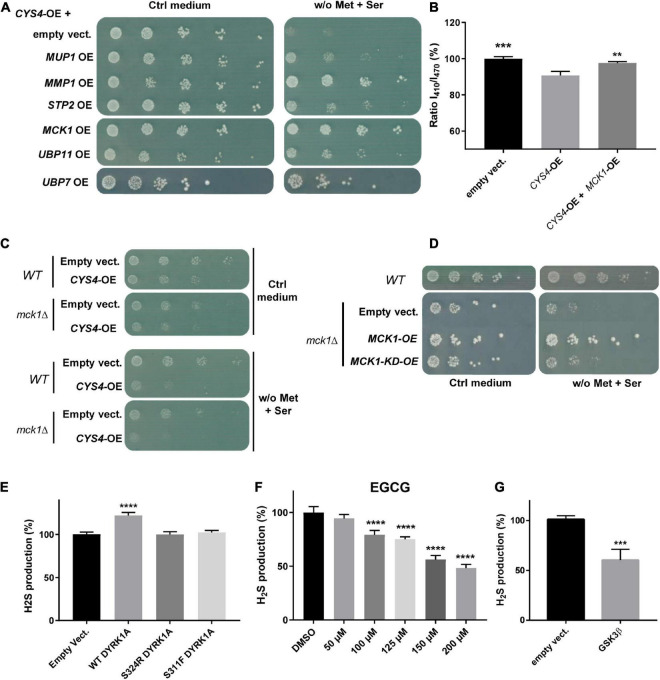

Identification of MCK1, the yeast homolog of GSK3, as a genetic suppressor of CYS4-OE phenotypes

To get better insights into the cellular mechanisms involved in CYS4-OE induced phenotypes, we sought to identify genetic suppressors. Amongst the genes having the capacity to save the methionine auxotrophy of CYS4-OE cells, six genes had a strong effect: MUP1 (a methionine permease), MMP1 (a S-methylmethionine permease), STP2 (a transcription factor that activates the transcription of amino acid permease genes), MCK1 (one of the four genes that encode glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) homologs in yeast), and UBP7 and UBP11, two ubiquitin specific proteases involved in endocytosis and in the sorting of internalized receptors (Tardiff et al., 2013; Weinberg and Drubin, 2014; Figure 2A). The overexpression of MUP1, MMP1, and STP2 may act in bringing up traces of methionine or related amino acids present in the medium to rescue the methionine auxotrophy induced by CYS4-OE. However, as the overexpression of MUP1 and MMP1 appears to also decrease cytosolic acidification of CYS4-OE cells (Supplementary Figure 1A), their action may also involve other molecular mechanisms. Similarly, MCK1 (Figure 2B), UBP11 and UBP7 (Supplementary Figure 1B) were also able to counteract the effects of CYS4-OE on cytosolic acidification.

FIGURE 2.

A genetic screening identified MCK1 as a genetic repressor of CYS4-OE induced phenotypes. (A,B) MCK1-OE rescues the consequences of CYS4-OE. (A) Genes that were the most effective in rescuing the methionine auxotrophy induced by CYS4-OE include genes related to amino acid import (MUP1, MMP2, STP2), a kinase (MCK1), and two genes encoding deubiquitinating enzymes (UBP7 and UBP11). (B) MCK1-OE restores normal cytosolic acidification of CYS4-OE cells. Comparison of each condition with CYS4-OE, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test: **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (C,D) Deletion of MCK1 causes slight methionine auxotrophy. (C) Deletion of MCK1 strengthens the effect of CYS4-OE on methionine auxotrophy. (D) The mck1Δ strain, similarly to CYS4-OE, has difficulty to grow on a methionine-free medium complemented with serine, and this methionine auxotrophy is rescued by the expression of wild-type MCK1 but not of a kinase-dead form of Mck1p (MCK1-KD). (E) Effect of human Dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation Regulated Kinase 1A (DYRK1A) overexpression on H2S production in HepG2 cells. The expression of wild-type Dyrk1A induced increased H2S expression 48 h after transfection, effect that was not visible using two mutants p.S324R and p.S311F which affect its kinase activity. (F) Inhibition of Dyrk1A activity decreased H2S production. A 24 h-treatment with epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), an inhibitor of Dyrk1A resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in H2S production. (G) The expression of a constitutively active form of GSK3β (p.S9A) resulted in decreased H2S production 72 h after transfection. (E,F) Comparison of each condition with empty vector or DMSO, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test: ****p < 0.0001. (G) Student’s t-test: ***p < 0.001.

Then, due to the important role of MCK1/GSK3 in cell signaling, we focused our attention on this genetic repressor of CYS4-OE induced phenotypes. As shown in Figures 2A, B MCK1-OE counteracted both methionine auxotrophy and cytosolic acidification phenotypes induced by CYS4-OE. On the opposite, MCK1 deletion appeared to slightly enhance the methionine auxotrophy of CYS4-OE cells (Figure 2C), suggesting that in the absence of Mck1p, Cys4p activity may be promoted. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the fact that a mck1Δ strain (without CYS4 overexpression) shows slight methionine auxotrophy, which is rescued by the expression of wild-type MCK1 but not by a KD form of MCK1 (p.K68R, Lim et al., 1993; Figure 2D). Taken together, these results thus show that Cys4p activity is reduced in the presence of Mck1p but increased in the absence of Mck1p, suggesting that Mck1p inhibits directly or not Cys4p activity, and that Mck1p kinase activity is required.

The genetic interactions between CYS4 and YAK1, and between CYS4 and MCK1, are conserved in mammalian cells

Then, to check whether the regulation of Cys4p by Yak1p is conserved in mammalian cells, we tested the effect of the expression of DYRK1A in the human hepatoma HepG2 cell line. We chose this cell line because CBS is known to be highly expressed and active in the liver. In addition, this cell line is commonly used to study CBS-mediated hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production (Wang et al., 2018), as cystathionine γ lyase (CSE), the other enzyme involved in H2S production, is expressed at very low levels in HepG2 cells. H2S production, measured using the 7-AzMC fluorogenic probe as previously described (Conan et al., 2022), can be thus considered in HepG2 as a read-out for CBS activity. As shown in Figures 2E, D YRK1A expression in HepG2 cells induced a significant increase in H2S production without affecting cell proliferation and/or viability (Supplementary Figure 1C), whereas two mutant forms of DYRK1A (p.S324R and p.S311F) that had lost their kinase activity (Courraud et al., 2021) had no effect on H2S production (Figure 2E). Conversely, a 24 h treatment with epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), an inhibitor of DYRK1A, decreased H2S production in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2F and Supplementary Figure 1D). Similarly, the expression of a constitutively activated form of GSK3β (p.S9A mutant) in HepG2 cells induced a significant decrease of H2S production (Figure 2G) without affecting cell proliferation and/or viability (Supplementary Figure 1E). Taken together, these results confirm genetic interactions between CBS and DYRK1A and between CBS and GSK3β, which are conserved between yeast and human.

Several small molecules identified in a drug screening appear to converge on metal ion chelation and/or inhibition of NF-κB and Akt/GSK3β pro-survival signaling pathways

To get further insights into the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of CBS activity, we screened a set of 2,932 small molecules from the National Cancer Institute, consisting in diverse chemical scaffolds, including natural products and approved oncology drugs. Several compounds were able to restore cell growth of CYS4-OE cells on medium without methionine (Supplementary Table 4). Remarkably, the vast majority of the molecules identified in this screen have been described to form complexes with metal ions or to either inhibit NF-κB and/or the Akt/GSK3β pathway (Table 1). Interestingly, six of these compounds have the property to form complexes with Cu(II) (Table 1), supporting our previous findings that copper chelation efficiently decreases CBS activity both in yeast and mammalian cells (Conan et al., 2022). Similarly, zinc pyrithione, a zinc ionophore (Ding and Lind, 2009) that we previously described (Conan et al., 2022), was also found active in the drug screening (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4).

TABLE 1.

The molecules identified in the screen share common properties such as metal cation binding or target pro-survival pathways.

| Compound | Metal-binding properties | Effect on NF-κ B pathway | Effect on Akt/GSK3β pathway | References |

| 9-Methylstreptimidone | None | Inhibitor | possible inhibitor | Wang et al., 2006; Ishikawa et al., 2009; Brassesco et al., 2012; Koide et al., 2015 |

| 4-(2-Thiazolylazo)-resorcinol | Cu(II) | Stanley and Cheney, 1966 | ||

| 1-(2-Thiazolylazo)-2-naphtol | Cu(II) | Pease and Williams, 1959 | ||

| Zinc pyrithione | Zn(II) | Inhibitor | Kim et al., 1999; Ding and Lind, 2009 | |

| N,N- dimethyldaunomycin hydrochloride |

Cu(II) |

Inhibitor |

Malatesta et al., 1987; Boland et al., 1997; Ho et al., 2005; Jabłoñska-Trypuæ et al., 2017 |

|

| Doxorubicin dihydrochloride | ||||

| Daunorubicin hydrochloride | ||||

| γ-thujaplicin | Cu(II), Zn(II) | Inhibitor | Inhibitor | MacLean and Gardner, 1956; Miyamoto et al., 1998; Byeon et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2020 |

| Verrucarin A,10-epoxide |

Inhibitor |

Inhibitor |

Deeb et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016 |

|

| 8α-Hydroxy-verrucarin A | ||||

| Monoacetyl verrucarin A epoxide | ||||

| Chrysomycin A | Inhibitor | Inhibitor | Liu et al., 2021, 2022 | |

| Naphtoquinones | Cu(II) | Inhibitor | Brandelli et al., 2004; Golan-Goldhirsh and Gopas, 2014 |

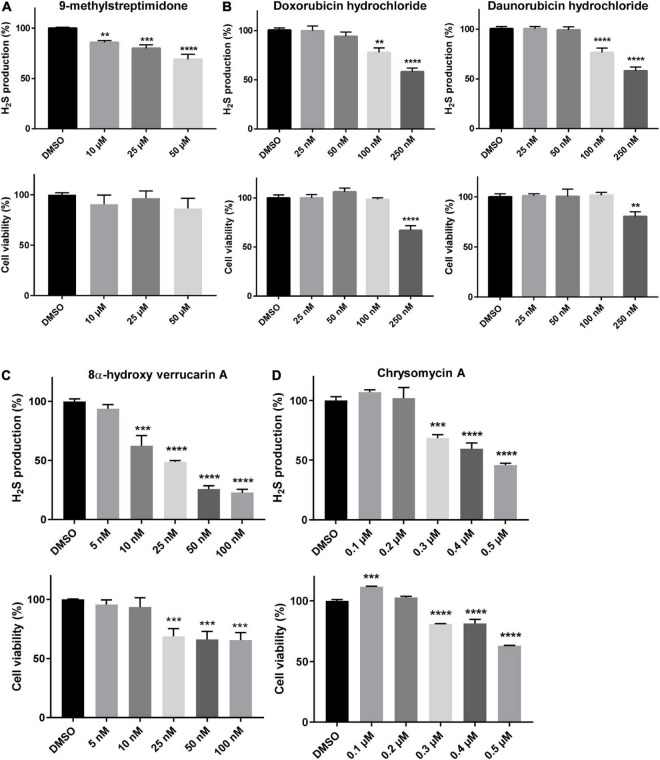

Among the other compounds identified, eight of them are known to inhibit pro-survival pathways (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4). Among these compounds, 9-methylstreptimidone, an inhibitor of NF-κB (Wang et al., 2006; Ishikawa et al., 2009) and possibly of the Akt/GSK3β pathway (Brassesco et al., 2012; Koide et al., 2015), showed a strong capacity to rescue yeast growth on a medium without methionine (Supplementary Table 4). Similarly, 8α-hydroxy verrucarin A and chrysomycin A, both inhibitors of NF-κB and of the Akt/GSK3β pathway (Deeb et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016), also counteracted the growth defect phenotype induced by Cys4p overexpression (Supplementary Table 4). In order to check whether these drugs were also able to inhibit CBS activity in mammalian cells, we tested some of the most active compounds on H2S production in HepG2 cells. As shown in Figure 3, inhibitors of NF-κB and/or Akt/GSK3β pathway such as 9-methylstreptimidone (Figure 3A), 8α-hydroxy verrucarin A (Figure 3C) and chrysomycin A (which has been identified twice in the screening) (Figure 3D) were able to decrease H2S production (upper panel), although 8α-hydroxy verrucarin A and chrysomycin A also affected cell viability (lower panel). Similarly, two members of the anthracycline antibiotic family, doxorubicin and daunorubicin hydrochloride decreased H2S production in HepG2 cells (Figure 3B, upper panels) although they induced cell toxicity at higher concentrations (Figure 3B, lower panels). Finally, several small molecules with moderate activity were obtained in the screening, including several derivatives of naphtoquinones, which are also inhibitors of the NF-κB pathway (Supplementary Table 4). However, as their activity was moderate in rescuing cell growth in yeast, they were not tested on H2S production in HepG2 cells.

FIGURE 3.

Molecules reducing the phenotypes induced by CYS4-OE decrease H2S production. The level of H2S production and cell viability were assessed using the Azido-4-Methylcoumarin (AzMC) probe and the WST-8 assay, respectively. A 24 h-treatment of HepG2 cells with 9-methylstreptimidone (A), doxorubicin and daunorubicin hydrochloride (B), 8α-hydroxy verrucarin A (C), and chrysomycin A (D), resulted in decreased H2S production (upper panels) without decreasing cell viability, except at the highest concentrations tested (lower panels). Comparison of each condition with DMSO, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test: **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

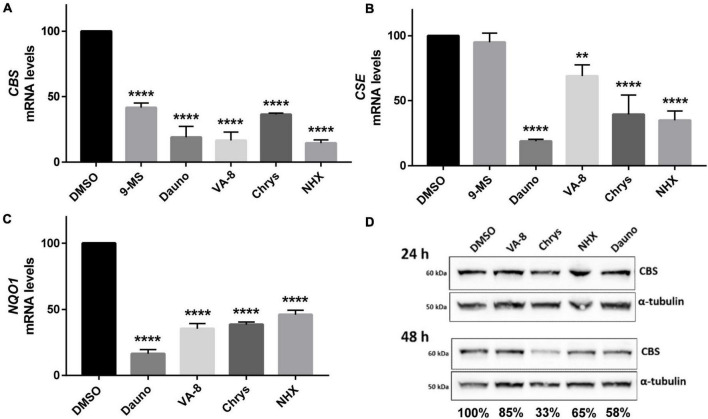

To further confirm the hypothesis of a regulation of CBS activity by the Akt/GSK3β and/or NF-κB pathways, we assessed the impact of inhibitors of these pathway (9-methylstreptimidone, 8α-hydroxy verrucarin A, chrysomycin and daunorubicin) on the mRNA levels of CBS, CSE and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), three genes known to be regulated by these pathways (Wang et al., 2014; Mutter et al., 2015; Ozaki et al., 2018). We also evaluated the effect of nitroxolin (NHX), a copper chelator that we previously identified as a candidate inhibitor for CBS (Conan et al., 2022) and which has been reported to reduce Akt phosphorylation and decrease GSK3β phosphorylation (Xu et al., 2019; Veschi et al., 2020). As shown in Figures 4A–C, all the compounds that reduced H2S production in HepG2 cells (Figure 3) also decreased mRNA levels of CBS, CSE, and NQO1 genes, after 24 h of treatment. Accordingly, the levels of CBS protein were also reduced after 48 h but not after 24 h of treatment (Figure 4D). Altogether, these data suggest that the Akt/GSK3β and NF-κB pathways are involved both in the regulation of CBS activity (as assessed by the decreased H2S production 24 h after treatment), but also in the regulation of CBS expression, effect which is observed at the mRNA level 24 h after treatment and at the protein level 48 h after treatment.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of molecules identified in the pharmacological screening on Cystathionine beta synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ lyase (CSE) and NQO1 mRNA and CBS protein levels. (A–C) The level of CBS (A), CSE (B), and NQO1 mRNAs: three genes involved in the defense against oxidative stress and which are regulated by the NF-κB and the Akt/GSK3β pathways, was assessed by RT-qPCR 24 h after treatment with 30 μM of 9-methylstreptimidone, 150 nM of daunorubicin hydrochloride, 10 nM of 8α-hydroxy-verrucarin A (VA-8), 200 nM of chrysomycin (Chrys) and 50 μM of NHX in HepG2 cells. (D) Similarly, the level of CBS protein was assessed by western-blot 24 and 48 h after treatment with the same drugs. Ratios of CBS/α-tubulin signals are indicated below each lane for 48 h fater treatment. (A–C) Comparison of each condition with DMSO, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test: **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. Note that there is no error bar for DMSO because the different values we obtained were expressed as percentages compared to the DMSO condition which was set up at 100%.

Discussion

DYRK1A positively regulates CBS activity

Several studies have previously suggested a genetic interaction between CBS and DYRK1A but the nature of this interaction was still undetermined. Indeed, most of these data have been obtained in mouse models and it is sometimes difficult to assess in a complete organism whether the effects observed are direct or indirect consequences of DYRK1A or CBS deregulation. Here our data obtained in simple cellular models suggest that DYRK1A positively regulates CBS activity and that this relationship is conserved between yeast and human. This observation is consistent with previous findings obtained in mouse. For example, the triplication of both DYRK1A and CBS results in additive effects on hyperactivity and locomotion compared to mice having a triplication of either gene (Maréchal et al., 2019). Similarly, Delabar et al. (2014) have described increased CBS activity in the liver of Dyrk1A-overexpressing mice. This group also showed that forced expression of Dyrk1A (using an adenoviral construct) in the liver of CBS+/− mice induced increased CBS activity both in the liver (Tlili et al., 2013; Latour et al., 2015) and the brain (Baloula et al., 2018). The pathways involved in this regulation have been explored: decreased homocysteine levels, resulting from Dyrk1A overexpression, induced increased phosphorylation of the serine threonine kinase Akt (on Serine 473) (Guedj et al., 2012; Abekhoukh et al., 2013), which is then activated to promote cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis. On the contrary, mice or rats with hyperhomocysteinemia (resulting from a high-methionine diet) have decrease Dyrk1A protein levels both in the liver and the brain (Hamelet et al., 2009; Rabaneda et al., 2016) and consequently decreased phosphorylation of Akt (Liu et al., 2010, 2011; Figure 5). Our data, obtained in a simple model organism, thus confirm previous observations suggesting a link between DYRK1A, homocysteine levels and Akt phosphorylation in one hand and between DYRK1A expression and CBS activity on the other hand.

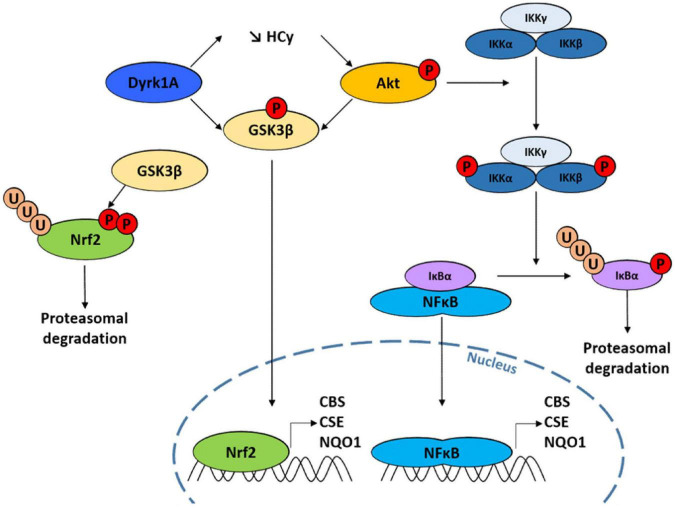

FIGURE 5.

Scheme illustrating the genetic connection between Dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation Regulated Kinase 1A (DYRK1A), GSK3β and Cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) through the Akt and NF-κB pathways.

GSK3β negatively regulates CBS activity

The transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) encodes a protein which has a short half-time of only 30 min and which stability is controlled through the regulation of its turnover by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. It controls the expression of over 100 genes, including CBS (Hourihan et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2020), CSE (Jamaluddin et al., 2022), and NQO1 (Mutter et al., 2015), three genes that play an important role in cell response to oxidative stress. The homolog system to Nrf2 in yeast is Yap1p, which also confers protection against oxidative stress and regulates the expression of yeast homologs of CBS and CSE (Orumets et al., 2012). The kinase GSK3β has been shown to prevent the transcription of Nrf2 targets by phosphorylating two serine residues in Nrf2, leading to its nuclear exclusion and degradation (Salazar et al., 2006; Rada et al., 2011). All these data thus point toward a mechanism of regulation of CBS expression at the transcriptional level involving the Nrf2 pathway. This is consistent with our results showing that (i) the expression of Mck1p, the yeast homolog of GSK3β, antagonizes the effect of CYS4-OE in yeast (Figures 2A–B) and (ii) the expression of a constitutively active form of GSK3β decreased H2S production in HepG2 cells (Figure 2G). Interestingly, both kinase DYRK1A and Akt have convergent effects by directly inactivating GSK3β by phosphorylation at Thr356 (for DYRK1A) (Song et al., 2015) and on serine 9 (for Akt) (Tlili et al., 2013; Latour et al., 2015; Figure 5).

Role of NF-κB and Akt/GSK3β pathways in the regulation of the expression and activity of CBS

The compounds identified in our screening also confirm the importance not only of the Akt/GSK3β pathway but also of NF-κB, which is often activated by Akt/GSK3β (Ozes et al., 1999), in the regulation of CBS activity and expression. NF-κB is a key regulator of genes involved in the response to inflammation and stress. Ordinarily, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm through a direct interaction with a member of the IκB family of inhibitor proteins such as IκBα. Diverse range of stimuli, including oxidative stress, lead to the activation of the IKK complex (which contains two IκB kinases, IKKα and IKKβ). Phosphorylation of IκBα by the IKK complex triggers its recognition by an E3 ligase complex which leads to its polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. The liberated NF-κB dimer then translocates to the nucleus, where it binds specific DNA sequences, inducing the transcription of genes such as CBS (Li et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013), CSE (Wang et al., 2014; Ozaki et al., 2018), and NQO1 (Dinkova-Kostova and Talalay, 2010). Supporting these observations, we observed that several of the compounds identified in our screen and known to inhibit Akt and/or NF-κB pathways (9-methylstreptimidone, 8α-hydroxy verrucarin A, chrysomycin…) induced a significant decrease in CBS, CSE, and NQO1 mRNA levels (Figure 4). Similar results were obtained for NHX (Figure 4), a metal chelator that we previously identified as a candidate inhibitor for CBS (Conan et al., 2022), and which has been reported to reduce both Akt and GSK3β phosphorylation (Xu et al., 2019; Veschi et al., 2020). However, it is important to note that we cannot completely rule out possible additional effects on CBS at the post-transcriptional level. Indeed, several post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, glutathionylation or sumoylation, have been reported to play a role in the regulation of CBS enzymatic activity. In addition, CBS protein levels have been reported to be increased following Akt activation, without affecting CBS mRNA expression (Zhu et al., 2022), which suggests that these pathways may also target CBS enzymatic activity in addition to its expression. This is also suggested by the fact that H2S production was decreased 24 h after treatment with 9-methylstreptimidone, 8α-hydroxy verrucarin A, chrysomycin and daunorubicin, whereas the level of CBS protein was not reduced before 48 h of treatment. This suggests that these pathways act at the level of both CBS enzymatic activity and expression level.

Concerning the identification of MUP1, MMP1, STP2, UBP7, and UBP11 genes in the genetic screen, all five suggest a common role in overexpressing amino acid permeases at the plasma membrane, possibly to capture the low traces of methionine present in the medium and due to possible incomplete purification of other amino acids added in the medium. Indeed, Ubp7p and Ubp11p have been shown to deubiquinylate permeases ubiquitinylated by Rsp5p (the homolog of Nedd4L in yeast), preventing their endocytosis (Tardiff et al., 2013; Weinberg and Drubin, 2014). However, the fact that these genes also mitigate the cytosolic acidification of CYS4-OE cells suggest a possible other molecular mechanism. A possible mechanism to explain these results could be that an import of extracellular leucine or methionine would activate the Target Of Rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway (Takahara et al., 2020; Vellai, 2021), which in turn inhibits the retrograde response, the pathway which regulates the response to oxidative stress and which is the equivalent of the NF-κB pathway in yeast (Johnson and Johnson, 2014).

Role of metal chelation in the regulation of CBS activity

Several compounds identified in our drug screening point toward an important role of metal ion chelation in the regulation of CBS activity, as previously reported (Maréchal et al., 2019; Conan et al., 2022). Indeed, we previously showed that decreasing intracellular copper levels decreased the effects of CBS overexpression in yeast and H2S production in HepG2 cells (Conan et al., 2022). Here, the identification of several compounds involved in metal chelation [4-(2-Thiazolylazo)-resorcinol, 1-(2-Thiazolylazo)-2-naphtol, γ-thujaplicin, doxorubicin and daunorubicin hydrochloride, naphtoquinones…] confirm the importance of this process to decrease CBS activity. Several studies have shown that exposure of HepG2 cells or neuronal-like SH-SY5Y cells to copper (and to a lesser extent Zinc) induce phosphorylation of Akt and GSK3β (Ostrakhovitch et al., 2002; Walter et al., 2006; Barthel et al., 2007; Hickey et al., 2011) and that copper chelation reduces the levels of activated Akt and thus of inactivated GSK3β (Guo et al., 2021). Accordingly, we previously reported that several copper chelators such as D-penicillamine, trientine and several members of the 8-hydroxyquinoline family [clioquinol, chloroxine, NHX, and PBT2 (2-(dimethylamino) methyl-5,7-dichloro-8-hydroxyquinoline)] efficiently decreased CBS activity in several cell lines (Conan et al., 2022). Although further investigation is needed, the data obtained here with NHX (Figures 4A, D) suggest that the mechanism of action of this compound involves, at least in part, decreased CBS activity through the NF-κB and Akt/GSK3β pathways.

Disulfiram (DSF) is another compound that we previously identified in a similar drug screening (Maréchal et al., 2019). Its mechanism of action has not been fully deciphered. It has been suggested that DSF could inhibit CBS by its ionophore activity, increasing intracellular copper levels, as Cu-DSF was found more active than DSF on its own (Zuhra et al., 2020; Supplementary Figures 2A, B), which seemed in disagreement with our finding that increasing copper levels increased CBS activity (Conan et al., 2022). The relationship we here describe between the Akt and NF-κB pathways and CBS regulation could bring an explanation to this apparent discrepancy. Indeed, several groups have shown in various cellular models that DSF, on its own or combined to copper, decreases Akt phosphorylation (Kim J. Y. et al., 2016; Park et al., 2018; Nasrollahzadeh et al., 2021; Zha et al., 2021) as well as the NF-κB pathway (Wang et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2010; Yip et al., 2011). These data are in agreement with the observation that DSF on its own decreases H2S production, although with a limited effect, but has an increased effect (as well as increased toxicity) when combined to copper (Supplementary Figures 2A, B). Accordingly, we observed decreased CBS (as well as CSE and NQO1) mRNA levels in HepG2 cells treated with DSF-Cu (Supplementary Figure 2D). On the contrary, incubation with Bathocuproine disulphonate (BCS), a copper chelator totally abolished the effect of DSF (Supplementary Figure 2C).

Extrapolation of these findings to the context of Down syndrome

Our results, supported by others in mouse models (Tlili et al., 2013; Delabar et al., 2014; Latour et al., 2015; Baloula et al., 2018; Maréchal et al., 2019), suggest that the overexpression of DYRK1A and CBS have additive effects and that CBS expression and/or activity is increased following DYRK1A overexpression. On the contrary, Dyrk1A inhibition results in decreased CBS expression and/or activity as shown by H2S production in HepG2 cells treated with EGCG. This suggests that therapeutic research focusing on DYRK1A inhibition should, at least in part, also take care of the problem of CBS triplication, at the condition that these inhibitors are specific of DYRK1A and do not inhibit GSK3β as well, as our data suggest that GSK3β activation is needed to reduce Nrf2 activity and thus CBS expression.

Several studies have shown that the expression and/or activity of CBS is tightly regulated and strongly depends on the redox state of the cell (Mosharov et al., 2000; Banerjee and Zou, 2005), meaning that the triplication of this gene would not necessarily mean an overexpression. However, CBS overexpression has been extensively reported in patients with DS (Kamoun et al., 2003; Ichinohe et al., 2005; Panagaki et al., 2019). Accordingly, increased oxidative stress, confirmed in several studies in these patients, as well as a hyperactivation of the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway have been reported in the brain of DS patients (Perluigi et al., 2014). All these data suggest that any molecule decreasing the level of oxidative stress, inhibiting NF-κB pathway and/or activating GSK3β activity may result in decreasing CBS expression. Although several preclinical studies and clinical trials aimed at reducing oxidative stress using various anti-oxidant molecules have been performed (Rueda Revilla and Martínez-Cué, 2020), none of them has looked at the level of CBS expression and/or activity. This would be worth further investigating.

However, the regulation of CBS expression and/or activity also depends on other genes of chromosome 21. We showed here that DYRK1A overexpression increases CBS activity. Several other genes present on chromosome 21, including SOD1 and APP are directly or indirectly involved in mitochondrial function, contributing to oxidative stress (Izzo et al., 2018) and may thus on their own or in combination with others have an impact on CBS expression and/or activity. On the contrary, RCAN1, also present on chromosome 21, encodes an inhibitor of the NF-κB pathway and its overexpression may then be expected to decrease CBS activity and/or expression.

Taken together, our data provide further insights into the regulation of CBS activity and into the relationship with other genes important for brain development and functioning such as DYRK1A and GSK3β. Although further studies are still needed to fully understand the different contributions of these molecular actors into the pathophysiology of DS, the hope is that they will lead to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathology of DS, and thus to the development of more effective therapy that will bring amelioration or prevention of cognitive deficits in people with DS.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PC, AL, FB, CV, and GF: conceptualization. PC, AL, NC, FB, OM, CV, and GF: formal analysis. GF: funding acquisition and project administration. PC, AL, NC, CR, LC, and JM: investigation. PC, AL, FB, OM, CV, and GF: methodology. OM, CV, and GF: resources. OM, FB, CV, and GF: supervision. PC, AL, NC, CR, LC, CV, and GF: validation and visualization. PC, AL, and GF: writing—original draft preparation. PC, CV, and GF: writing—review and editing. All authors commented on the different versions of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hélène Simon for technical assistance. The pHluorin plasmid was kindly given by S. Léon (Institut Jacques Monod, Paris) and the DYRK1A plasmids by J. Courraud and A. Piton (IGBMC, Strasbourg).

Funding Statement

This project was supported by the Fondation Jérome Lejeune, La Ligue contre le Cancer, the Association Gaëtan Saleün, La Région Bretagne, and the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2022.1110163/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abekhoukh S., Planque C., Ripoll C., Urbaniak P., Paul J. L., Delabar J. M., et al. (2013). Dyrk1A, a serine/threonine kinase, is involved in ERK and Akt activation in the brain of hyperhomocysteinemic mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 47 105–116. 10.1007/s12035-012-8326-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altafaj X., Martín E. D., Ortiz-Abalia J., Valderrama A., Lao-Peregrín C., Dierssen M., et al. (2013). Normalization of Dyrk1A expression by AAV2/1-shDyrk1A attenuates hippocampal-dependent defects in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 52 117–127. 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonarakis S. E. (2017). Down syndrome and the complexity of genome dosage imbalance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18 147–163. 10.1038/nrg.2016.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asimakopoulou A., Panopoulos P., Chasapis C. T., Coletta C., Zhou Z., Cirino G., et al. (2013). Selectivity of commonly used pharmacological inhibitors for cystathionine β synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ lyase (CSE). Br. J. Pharmacol. 169 922–932. 10.1111/bph.12171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloula V., Fructuoso M., Kassis N., Gueddouri D., Paul J. L., Janel N. (2018). Homocysteine-lowering gene therapy rescues signaling pathways in brain of mice with intermediate hyperhomocysteinemia. Redox Biol. 19 200–209. 10.1016/j.redox.2018.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R., Zou C. G. (2005). Redox regulation and reaction mechanism of human cystathionine-beta-synthase: A PLP-dependent hemesensor protein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 433 144–156. 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel A., Ostrakhovitch E. A., Walter P. L., Kampkötter A., Klotz L. O. (2007). Stimulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling by copper and zinc ions: Mechanisms and consequences. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 463 175–182. 10.1016/j.abb.2007.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland M. P., Foster S. J., O’Neill L. A. (1997). Daunorubicin activates NFkappaB and induces kappaB-dependent gene expression in HL-60 promyelocytic and Jurkat T lymphoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272 12952–12960. 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandelli A., Bizani D., Martinelli M., Stefani V., Gerbase A. E. (2004). Antimicrobial activity of 1,4-naphthoquinones by metal complexation. Brazilian J. Pharm. Sci. 40 247–253. 26749803 [Google Scholar]

- Brassesco M. S., Pezuk J. A., Morales A. G., de Oliveira J. C., Valera E. T., da Silva G. N., et al. (2012). Cytostatic in vitro effects of DTCM-glutarimide on bladder carcinoma cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 13 1957–1962. 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.5.1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon S. E., Lee Y. G., Kim J. C., Han J. G., Lee H. Y., Cho J. Y. (2008). Hinokitiol, a natural tropolone derivative, inhibits TNF-alpha production in LPS-activated macrophages via suppression of NF-kappaB. Planta Med. 74 828–833. 10.1055/s-2008-1074548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Jhee K. H., Kruger W. D. (2004). Production of the neuromodulator H2S by cystathionine beta-synthase via the condensation of cysteine and homocysteine. J. Biol. Chem. 279 52082–52086. 10.1074/jbc.C400481200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conan P., Léon A., Gourdel M., Rollet C., Chaïr L., Caroff N., et al. (2022). Identification of 8-Hydroxyquinoline derivatives that decrease cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23:6769. 10.3390/ijms23126769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courraud J., Chater-Diehl E., Durand B., Vincent M., Del Mar Muniz Moreno M., Boujelbene I., et al. (2021). Integrative approach to interpret DYRK1A variants, leading to a frequent neurodevelopmental disorder. Genet. Med. 23 2150–2159. 10.1038/s41436-021-01263-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeb D., Gao X., Liu Y., Zhang Y., Shaw J., Valeriote F. A., et al. (2016). The inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells by verrucarin A, a macrocyclic trichothecene, is associated with the inhibition of Akt/NF-êB/mTOR prosurvival signaling. Int. J. Oncol. 49 1139–1147. 10.3892/ijo.2016.3587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delabar J. M., Latour A., Noll C., Renon M., Salameh S., Paul J. L., et al. (2014). One-carbon cycle alterations induced by Dyrk1a dosage. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 1 487–492. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre R., De Sola S., Pons M., Duchon A., de Lagran M. M., Farré M., et al. (2014). Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a DYRK1A inhibitor, rescues cognitive deficits in Down syndrome mouse models and in humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 58 278–288. 10.1002/mnfr.201300325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre R., de Sola S., Hernandez G., Farré M., Pujol J., Rodriguez J., et al. (2016). Safety and efficacy of cognitive training plus epigallocatechin-3-gallate in young adults with Down’s syndrome (TESDAD): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 15 801–810. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30034-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W. Q., Lind S. E. (2009). Metal ionophores – An emerging class of anticancer drugs, IUBMB. Life 61 1013–1018. 10.1002/iub.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Talalay P. (2010). NAD(P)H:quinone acceptor oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), a multifunctional antioxidant enzyme and exceptionally versatile cytoprotector. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 501 116–123. 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druzhyna N., Szczesny B., Olah G., Módis K., Asimakopoulou A., Pavlidou A., et al. (2016). Screening of a composite library of clinically used drugs and well-characterized pharmacological compounds for cystathionine β-synthase inhibition identifies benserazide as a drug potentially suitable for repurposing for the experimental therapy of colon cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 113 18–37. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudilot A., Trillaud-Doppia E., Boehm J. (2020). RCAN1 Regulates bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Curr. Biol. 30 1167–1176.e2. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Cerro S., Martínez P., Vidal V., Corrales A., Flórez J., Vidal R., et al. (2014). Overexpression of Dyrk1A is implicated in several cognitive, electrophysiological and neuromorphological alterations found in a mouse model of Down syndrome. PLoS One 9:e106572. 10.1371/journal.pone.0106572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan-Goldhirsh A., Gopas J. (2014). Plant derived inhibitors of NF-κB. Phytochem. Rev. 13 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Guedj F., Sébrié C., Rivals I., Ledru A., Paly E., Bizot J. C., et al. (2009). Green tea polyphenols rescue of brain defects induced by overexpression of DYRK1A. PLoS One 4:e4606. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedj F., Pereira P. L., Najas S., Barallobre M. J., Chabert C., Souchet B., et al. (2012). DYRK1A: A master regulatory protein controlling brain growth. Neurobiol. Dis. 46 190–203. 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Xu B., Pandey S., Goessl E., Brown J., Armesilla A. L., et al. (2010). Disulfiram/copper complex inhibiting NFkappaB activity and potentiating cytotoxic effect of gemcitabine on colon and breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 290 104–113. 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Cheng J., Zheng N., Zhang X., Dai X., Zhang L., et al. (2021). Copper promotes tumorigenesis by activating the PDK1-AKT oncogenic pathway in a copper transporter 1 dependent manner. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 8:e2004303. 10.1002/advs.202004303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelet J., Noll C., Ripoll C., Paul J. L., Janel N., Delabar J. M. (2009). Effect of hyperhomocysteinemia on the protein kinase DYRK1A in liver of mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res Commun. 378 673–677. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey J. L., Crouch P. J., Mey S., Caragounis A., White J. M., White A. R., et al. (2011). Copper(II) complexes of hybrid hydroxyquinoline-thiosemicarbazone ligands: GSK3β inhibition due to intracellular delivery of copper. Dalton Trans. 40 1338–1347. 10.1039/c0dt01176b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho W. C., Dickson K. M., Barker P. A. (2005). Nuclear factor-kappaB induced by doxorubicin is deficient in phosphorylation and acetylation and represses nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent transcription in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 65 4273–4281. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourihan J. M., Kenna J. G., Hayes J. D. (2013). The gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide induces nrf2-target genes by inactivating the keap1 ubiquitin ligase substrate adaptor through formation of a disulfide bond between cys-226 and cys-613. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19 465–481. 10.1089/ars.2012.4944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. H., Lu S. H., Chang C. C., Thomas P. A., Jayakumar T., Sheu J. R. (2015). Hinokitiol, a tropolone derivative, inhibits mouse melanoma (B16-F10) cell migration and in vivo tumor formation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 746 148–157. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe A., Kanaumi T., Takashima S., Enokido Y., Nagai Y., Kimura H. (2005). Cystathionine beta-synthase is enriched in the brains of Down’s patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338 1547–1550. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa Y., Tachibana M., Matsui C., Obata R., Umezawa K., Nishiyama S. (2009). Synthesis and biological evaluation on novel analogs of 9-methylstreptimidone, an inhibitor of NF-κB. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19 1726–1728. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo A., Mollo N., Nitti M., Paladino S., Calì G., Genesio R., et al. (2018). Mitochondrial dysfunction in down syndrome: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Mol. Med. 24:2. 10.1186/s10020-018-0004-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabłoñska-Trypuæ A., Świderski G., Krêtowski R., Lewandowski W. (2017). Newly synthesized doxorubicin complexes with selected metals-synthesis, structure and anti-breast cancer activity. Molecules 22:1106. 10.3390/molecules22071106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamaluddin M., Haas de Mello A., Tapryal N., Hazra T. K., Garofalo R. P., Casola A. (2022). NRF2 regulates cystathionine gamma-lyase expression and activity in primary airway epithelial cells infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Antiox. (Basel) 11:1582. 10.3390/antiox11081582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhee K. H., Kruger W. D. (2005). The role of cystathionine beta-synthase in homocysteine metabolism. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7 813–822. 10.1089/ars.2005.7.813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. E., Johnson F. B. (2014). Methionine restriction activates the retrograde response and confers both stress tolerance and lifespan extension to yeast, mouse and human cells. PLoS One 9:e97729. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat P. K., Kalani A., Tyagi N. (2015). Role of hydrogen sulfide in brain synaptic remodeling. Methods Enzymol. 555 207–229. 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun P. (2001). Mental retardation in Down syndrome: A hydrogen sulfide hpothesis. Med. Hypotheses 57 389–392. 10.1054/mehy.2001.1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun P., Belardinelli M. C., Chabli A., Lallouchi K., Chadefaux-Vekemans B. (2003). Endogenous hydrogen sulfide overproduction in Down syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 116A 310–311. 10.1002/ajmg.a.10847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. H., Kim J. H., Moon S. J., Chung K. C., Hsu C. Y., Seo J. T., et al. (1999). Pyrithione, a zinc ionophore, inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 259 505–509. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Lee K. S., Kim A. K., Choi M., Choi K., Kang M., et al. (2016). A chemical with proven clinical safety rescues Down-syndrome-related phenotypes in through DYRK1A inhibition. Dis. Model Mech. 9 839–848. 10.1242/dmm.025668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Y., Cho Y., Oh E., Lee N., An H., Sung D., et al. (2016). Disulfiram targets cancer stem-like properties and the HER2/Akt signaling pathway in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 379 39–48. 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H. (2011). Hydrogen sulfide: Its production, release and functions. Amino Acids 41 113–121. 10.1007/s00726-010-0510-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide N., Kaneda A., Yokochi T., Umezawa K. (2015). Inhibition of RANKL- and LPS-induced osteoclast differentiations by novel NF-κB inhibitor DTCM-glutarimide. Int. Immunopharmacol. 25 162–168. 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour A., Salameh S., Carbonne C., Daubigney F., Paul J. L., Kergoat M., et al. (2015). Corrective effects of hepatotoxicity by hepatic Dyrk1a gene delivery in mice with intermediate hyperhomocysteinemia. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2 51–60. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune J., Gauthier M., Turpin R. (1959). Les chromosomes humains en culture de tissus. CR Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. (Paris) 248 602–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Xie R., Hu S., Wang Y., Yu T., Xiao Y., et al. (2012). Upregulation of cystathionine beta-synthetase expression by nuclear factor-kappa B activation contributes to visceral hypersensitivity in adult rats with neonatal maternal deprivation. Mol. Pain 8:89. 10.1186/1744-8069-8-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M. Y., Dailey D., Martin G. S., Thorner J. (1993). Yeast MCK1 protein kinase autophosphorylates at tyrosine and serine but phosphorylates exogenous substrates at serine and threonine. J. Biol. Chem. 268 21155–21164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lista M. J., Martins R. P., Billant O., Contesse M. A., Findakly S., Pochard P., et al. (2017). Nucleolin directly mediates Epstein-Barr virus immune evasion through binding to G-quadruplexes of EBNA1 mRNA. Nat. Commun. 8:16043. 10.1038/ncomms16043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. H., Zhao Y. S., Gao S. Y., Li S. D., Cao J., Zhang K. Q., et al. (2010). Hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration is impaired in mice with methionine diet-induced hyperhomocysteinemia. Am. J. Pathol. 177 2357–2365. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. J., Ma L. Q., Liu W. H., Zhou W., Zhang K. Q., Zou C. G. (2011). Inhibition of hepatic glycogen synthesis by hyperhomocysteinemia mediated by TRB3. Am. J. Pathol. 178 1489–1499. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Gao X., Deeb D., Zhang Y., Shaw J., Valeriote F. A., et al. (2016). Mycotoxin verrucarin A inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells by inhibiting prosurvival Akt/NF-kB/mTOR signaling. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 11 251–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Lin X., Huang C. (2020). Activation of the reverse transsulfuration pathway through NRF2/CBS confers erastin-induced ferroptosis resistance. Br. J. Cancer 122 279–292. 10.1038/s41416-019-0660-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Zhang S. S., Liu D. N., Yang Y. L., Wang Y. H., Du G. H. (2021). Chrysomycin a attenuates neuroinflammation by down-regulating NLRP3/Cleaved Caspase-1 Signaling Pathway in LPS-Stimulated Mice and BV2 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:6799. 10.3390/ijms22136799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D.-N., Liu M., Zhang S.-S., Shang Y.-F., Song F.-H., Zhang H.-W., et al. (2022). Chrysomycin a inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of U251 and U87-MG glioblastoma cells to exert its anti-cancer effects. Molecules 27:6148. 10.3390/molecules27196148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., et al. (1998). Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast Chichester Engl. 14 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean H., Gardner J. A. F. (1956). Analytical method of thujaplicins. Anal. Chem. 28:509512. 19822109 [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta V., Gervasini A., Morrazoni F. (1987). Chelation of Copper(II) ions by doxorubicin and 4‘-epidoxorubicin: Esr evidence for a new complex at high anthracycline/copper molar ratios. Inorganica Chim. Acta I36, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal D., Brault V., Léon A., Martin D., Lopes Pereira P., Loaëc N., et al. (2019). Cbs overdosage is necessary and sufficient to induce cognitive phenotypes in mouse models of Down syndrome and interacts genetically with Dyrk1a. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28 1561–1577. 10.1093/hmg/ddy447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto D., Kusagaya Y., Endo N., Sometani A., Takeo S., Suzuki T., et al. (1998). Thujaplicin–copper chelates inhibit replication of human influenza viruses. Antivir. Res. 39 89–100. 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00034-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya H., Shimizu-Yoshida Y., Omori A., Iwashita S., Katoh M., Sakai A. (2001). Yak1p, a DYRK family kinase, translocates to the nucleus and phosphorylates yeast Pop2p in response to a glucose signal. Genes Dev. 15 1217–1228. 10.1101/gad.884001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosharov E., Cranford M. R., Banerjee R. (2000). The quantitatively important relationship between homocysteine metabolism and glutathione synthesis by the transsulfuration pathway and its regulation by redox changes. Biochemistry 39 13005–13011. 10.1021/bi001088w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutter F. E., Park B. K., Copple I. M. (2015). Value of monitoring Nrf2 activity for the detection of chemical and oxidative stress. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43 657–662. 10.1042/BST20150044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano-Kobayashi A., Awaya T., Kii I., Sumida Y., Okuno Y., Yoshida S., et al. (2017). Prenatal neurogenesis induction therapy normalizes brain structure and function in Down syndrome mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 10268–10273. 10.1073/pnas.1704143114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh A., Momeny M., Fasehee H., Yaghmaie M., Bashash D., Hassani S., et al. (2021). Anti-proliferative activity of disulfiram through regulation of the AKT-FOXO axis: A proteomic study of molecular targets. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1868:119087. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2021.119087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann F., Gourdain S., Albac C., Dekker A. D., Bui L. C., Dairou J., et al. (2018). DYRK1A inhibition and cognitive rescue in a Down syndrome mouse model are induced by new fluoro-DANDY derivatives. Sci. Rep. 8:2859. 10.1038/s41598-018-20984-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. L., Duchon A., Manousopoulou A., Loaëc N., Villiers B., Pani G., et al. (2018). Correction of cognitive deficits in mouse models of Down syndrome by a pharmacological inhibitor of DYRK1A. Dis. Model Mech. 11:dmm035634. 10.1242/dmm.035634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orumets K., Kevvai K., Nisamedtinov I., Tamm T., Paalme T. (2012). YAP1 over-expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae enhances glutathione accumulation at its biosynthesis and substrate availability levels. Biotechnol. J. 7 566–568. 10.1002/biot.201100363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrakhovitch E. A., Lordnejad M. R., Schliess F., Sies H., Klotz L. O. (2002). Copper ions strongly activate the phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt pathway independent of the generation of reactive oxygen species. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 397 232–239. 10.1006/abbi.2001.2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki T., Tsubota M., Sekiguchi F., Kawabata A. (2018). Involvement of NF-κB in the upregulation of cystathionine-γ-lyase, a hydrogen sulfide-forming enzyme, and bladder pain accompanying cystitis in mice. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 45 355–361. 10.1111/1440-1681.12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozes O. N., Mayo L. D., Gustin J. A., Pfeffer S. R., Pfeffer L. M., Donner D. B. (1999). NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature 401 82–85. 10.1038/43466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagaki T., Randi E. B., Augsburger F., Szabo C. (2019). Overproduction of H2S, generated by CBS, inhibits mitochondrial Complex IV and suppresses oxidative phosphorylation in Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 18769–18771. 10.1073/pnas.1911895116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. M., Go Y. Y., Shin S. H., Cho J. G., Woo J. S., Song J. J. (2018). Anti-cancer effects of disulfiram in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma via autophagic cell death. PLoS One 13:e0203069. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease B. F., Williams M. B. (1959). Spectrophotometric investigation of analytical reagent 1-(2-pyridylazo)-2-naphtol and its copper chelate. Anal. Chem. 6 1044–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Perluigi M., Pupo G., Tramutola A., Cini C., Coccia R., Barone E., et al. (2014). Neuropathological role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis in Down syndrome brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842 1144–1153. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabaneda L. G., Geribaldi-Doldán N., Murillo-Carretero M., Carrasco M., Martínez-Salas J. M., Verástegui C., et al. (2016). Altered regulation of the Spry2/Dyrk1A/PP2A triad by homocysteine impairs neural progenitor cell proliferation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863 3015–3026. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada P., Rojo A. I., Chowdhry S., McMahon M., Hayes J. D., Cuadrado A. (2011). SCF/β-TrCP promotes glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor in a Keap1-independent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31 1121–1133. 10.1128/MCB.01204-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda Revilla N., Martínez-Cué C. (2020). Antioxidants in down syndrome: From preclinical studies to clinical trials. Antioxidants (Basel) 9:692. 10.3390/antiox9080692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar M., Rojo A. I., Velasco D., de Sagarra R. M., Cuadrado A. (2006). Glycogen synthase kinase-3β inhibits the xenobiotic and antioxidant cell response by direct phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of the transcription factor Nrf2. J. Biol. Chem. 281 14841–14851. 10.1074/jbc.M513737200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi A., Faizi M., Belichenko P. V., Mobley W. C. (2007). Using mouse models to explore genotype-phenotype relationship in Down syndrome. Ment. Retard Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 13 207–214. 10.1002/mrdd.20164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W. J., Song E. A., Jung M. S., Choi S. H., Baik H. H., Jin B. K., et al. (2015). Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) by dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (Dyrk1A). J. Biol. Chem. 290 2321–2333. 10.1074/jbc.M114.594952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley R. W., Cheney G. E. (1966). Metal complexes of 4-(2’thiazolylazo)-resorcinol: A comparative study with 4-(2’-pyridylazo)-resorcinol. Talanta 13 1619–1629. 10.1016/0039-9140(66)80244-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C. (2020). The re-emerging pathophysiological role of the cystathionine-β-synthase - hydrogen sulfide system in Down syndrome. FEBS J. 287 3150–3160. 10.1111/febs.15214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara T., Amemiya Y., Sugiyama R., Maki M., Shibata H. (2020). Amino acid-dependent control of mTORC1 signaling: A variety of regulatory modes. J. Biomed. Sci. 27:87. 10.1186/s12929-020-00679-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff D. F., Jui N. T., Khurana V., Tambe M. A., Thompson M. L., Chung C. Y., et al. (2013). Yeast reveal a “druggable” Rsp5/Nedd4 network that ameliorates α-synuclein toxicity in neurons. Science 342 979–983. 10.1126/science.1245321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorson M. K., Majtan T., Kraus J. P., Barrios A. M. (2013). Identification of cystathionine β-synthase inhibitors using a hydrogen sulfide selective probe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52 4641–4644. 10.1002/anie.201300841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorson M. K., Van Wagoner R. M., Harper M. K., Ireland C. M., Majtan T., Kraus J. P., et al. (2015). Marine natural products as inhibitors of cystathionine beta-synthase activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25 1064–1066. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlili A., Noll C., Middendorp S., Duchon A., Jouan M., Benabou E., et al. (2013). DYRK1A overexpression decreases plasma lecithin:Cholesterol acyltransferase activity and apolipoprotein A-I levels. Mol. Genet. Metab. 110 371–377. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valbuena S., García Á, Mazier W., Paternain A. V., Lerma J. (2019). Unbalanced dendritic inhibition of CA1 neurons drives spatial-memory deficits in the Ts2Cje Down syndrome model. Nat. Commun. 10:4991. 10.1038/s41467-019-13004-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellai T. (2021). How the amino acid leucine activates the key cell-growth regulator mTOR. Nature 596 192–194. 10.1038/d41586-021-01943-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veschi S., Ronci M., Lanuti P., De Lellis L., Florio R., Bologna G., et al. (2020). Integrative proteomic and functional analyses provide novel insights into the action of the repurposed drug candidate nitroxoline in AsPC-1 cells. Sci. Rep. 10:2574. 10.1038/s41598-020-59492-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P. L., Kampkötter A., Eckers A., Barthel A., Schmoll D., Sies H., et al. (2006). Modulation of FoxO signaling in human hepatoma cells by exposure to copper or zinc ions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 454 107–113. 10.1016/j.abb.2006.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., McLeod H. L., Cassidy J. (2003). Disulfiram-mediated inhibition of NF-kappaB activity enhances cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Int. J. Cancer 104 504–511. 10.1002/ijc.10972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Igarashi M., Ikeda Y., Horie R., Umezawa K. (2006). Inhibition of NF-Kappa B Activation by 9-Methylstreptimidone Isolated from Streptomyces. Heterocycles 69:377. 10.3727/096504012x13425470196056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Guo Z., Wang S. (2014). The binding site for the transcription factor, NF-κB, on the cystathionine γ-lyase promoter is critical for LPS-induced cystathionine γ-lyase expression. Int. J. Mol. Med. 34 639–645. 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Cai H., Hu Y., Liu F., Huang S., Zhou Y., et al. (2018). A Pharmacological Probe Identifies Cystathionine β-Synthase as a new negative regulator for ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 9:1005. 10.1038/s41419-018-1063-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. S., Drubin D. G. (2014). Regulation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis by dynamic ubiquitination and deubiquitination. Curr. Biol. 24 951–959. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. J., Hsu W. J., Wu L. H., Liou H. P., Pangilinan C. R., Tyan Y. C., et al. (2020). Hinokitiol reduces tumor metastasis by inhibiting heparanase via extracellular signal-regulated kinase and protein kinase B pathway. Int. J. Med. Sci. 17 403–413. 10.7150/ijms.41177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N., Huang L., Li X., Watanabe M., Li C., Xu A., et al. (2019). The Novel combination of nitroxoline and PD-1 Blockade, exerts a potent antitumor effect in a mouse model of prostate cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 15 919–928. 10.7150/ijbs.32259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip N. C., Fombon I. S., Liu P., Brown S., Kannappan V., Armesilla A. L., et al. (2011). Disulfiram modulated ROS-MAPK and NFκB pathways and targeted breast cancer cells with cancer stem cell-like properties. Br. J. Cancer 104 1564–1574. 10.1038/bjc.2011.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha J., Bi S., Deng M., Chen K., Shi P., Feng L., et al. (2021). Disulfiram/copper shows potent cytotoxic effects on myelodysplastic syndromes via inducing Bip-mediated apoptosis and suppressing autophagy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 902:174107. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. H., Hu J., Zhou Y. L., Hu S., Wang Y. M., Chen W., et al. (2013). Promoted interaction of nuclear factor-κB with demethylated cystathionine-β-synthetase gene contributes to gastric hypersensitivity in diabetic rats. J. Neurosci. 33 9028–9038. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1068-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Yu J., Lei X., Wu J., Niu Q., Zhang Y., et al. (2013). High-throughput tandem-microwell assay identifies inhibitors of the hydrogen sulfide signaling pathway. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 49 11782–11784. 10.1039/c3cc46719h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Chan K. T., Huang X., Cerra C., Blake S., Trigos A. S., et al. (2022). Cystathionine-β-synthase is essential for AKT-induced senescence and suppresses the development of gastric cancers with PI3K/AKT activation. Elife 11:e71929. 10.7554/eLife.71929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]