Abstract

Evidence on the relations between heart rate, brain morphology and cognition is limited. We examined the associations of resting heart rate (RHR), visit-to-visit heart rate variation (VVHRV), brain volumes and cognitive impairment. The study sample consisted of postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study and its ancillary MRI sub-studies (WHIMS-MRI 1 and WHIMS-MRI 2) without a history of cardiovascular disease, including 493 with one and 299 women with two brain MRI scans. Heart rate readings were acquired annually starting from baseline visit (1996–1998). RHR was calculated as the mean and VVHRV as standard deviation of all available HR readings. Brain MRI scans were performed between 2005 and 2006 (WHIMS-MRI 1), and approximately 5 years later (WHIMS-MRI 2). Cognitive impairment was defined as incident mild cognitive impairment or probable dementia until December 30, 2017. An elevated RHR was associated with greater brain lesion volumes at the first MRI exam [7.86cm3 (6.48, 9.24) vs. 4.78cm3 (3.39, 6.17), p-value<0.0001] and with significant increases in lesion volumes between brain MRI exams [6.20cm3 (4.81, 7.59) vs. 4.28cm3 (2.84, 5.73), p-value=0.0168]. Larger ischemic lesion volumes were associated with a higher risk for cognitive impairment [Hazard Ratio (95% confidence interval), 2.02 (1.18, 3.47), p-value=0.0109]. Neither RHR nor VVHRV were related to cognitive impairment. In sensitivity analyses, we additionally included women with a history of cardiovascular disease to the study sample. The main results were consistent to those without a history of cardiovascular disease. In conclusion, these findings show an association between elevated RHR and ischemic brain lesions, probably due to underlying subclinical disease processes.

Keywords: heart rate, brain imaging, cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Higher resting heart rate (RHR) has been shown to predict myocardial infarction, coronary death and stroke.1 Beyond cardiovascular disease, there is accumulating evidence that RHR and visit-to-visit heart rate variation (VVHRV) may also be related to subclinical cerebrovascular disease and cognitive impairment later in life.2–4 However, evidence on the relations between RHR, VVHRV, and cognition is mostly limited to populations already suffering from a high burden of cardiovascular disease.2,3 This is problematic given that the risk of cognitive impairment and brain lesions is greater among those with longer duration and more severe exposure to cardiovascular disease or risk factors. To this point, it is not entirely clear, if RHR and VVHRV are also associated with brain morphology abnormalities and cognitive function in older individuals without a history of cardiovascular disease as longitudinal data on brain morphology and cognitive functioning are largely missing.4 Such data can help to identify subclinical disease processes at an early stage which may predispose to brain lesions and to brain volume changes and ultimately to cognitive impairment over time. Thus, this study evaluates the relations of RHR, VVHRV, brain morphology and cognitive impairment in a cohort of older (≥63 years) women with and without a documented history of cardiovascular disease or major cardiovascular risk factors using longitudinal brain MRI scans with concomitant structured cognitive assessment.

METHODS

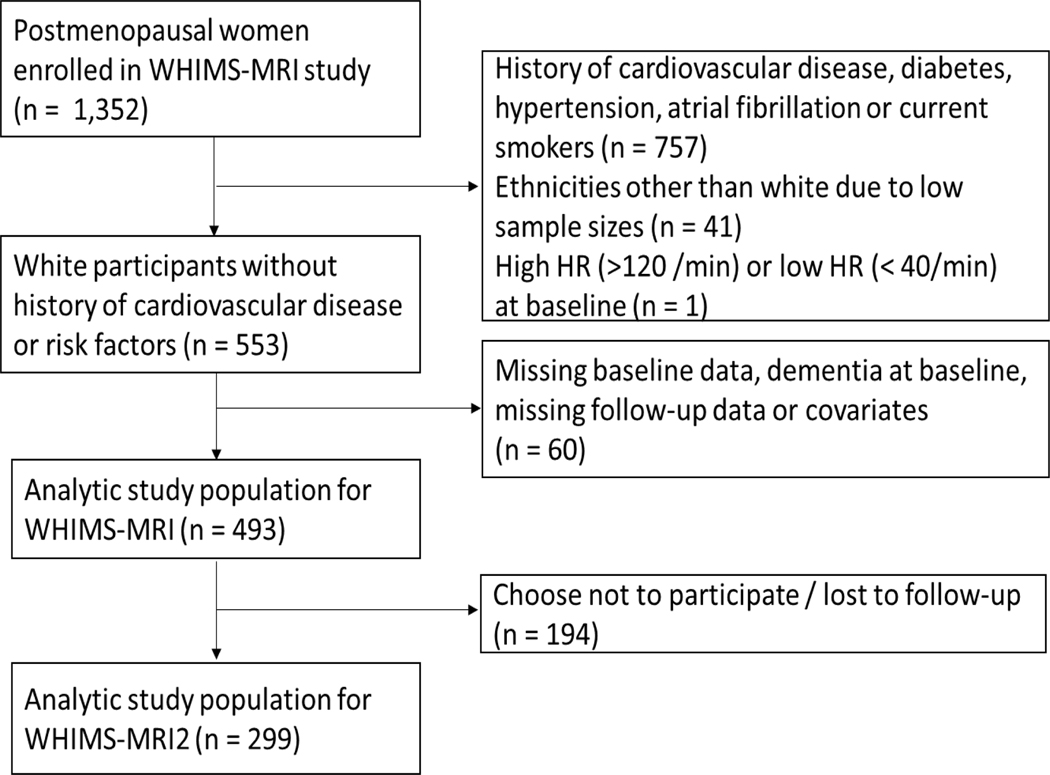

The study cohort consisted of postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study and its subsequent ancillary MRI sub studies (WHIMS-MRI 1 and WHIMS-MRI 2).5 WHIMS, which enrolled women between May 1996 and December 1999 investigated the effect of postmenopausal hormone regimens on cognitive function and cognitive impairment in 39 clinical centers across the United States.6 The WHIMS-MRI 1 study and its subsequent follow-up, the WHIMS-MRI 2 study, were conducted in 14 of the 39 WHIMS clinical sites to investigate if postmenopausal hormone therapy affects brain structure over time. WHIMS-MRI 1 recruitment began in January 2005 and was completed in April 2006. The WHIMS-MRI 2 study occurred an average of 4.7 years after WHIMS-MRI1 recruitment. WHIMS-MRI 1 conducted brain scans on 1,403 women, 51 of whom failed subsequent quality checks and were therefore excluded (n= 1,352). This main analysis excluded women with a history of diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation, hypertension or current smokers at baseline (n=757). The risk of cognitive impairment and brain lesions is greater among those with longer duration and more severe exposure of these risk factors. Unfortunately, infrequent screening, delayed diagnoses, and poor management are common problems which is why we excluded women with presence of these risk factors in order to restrict the analysis to a relatively healthy population. Nonetheless, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis, where we included women with these risk factors. Among the 757 participants with low cardiovascular risk at baseline, we further excluded women with ethnicities other than white due to small sample sizes (n=41) and women with very low (<40 beats/min) or very high (>120 beats/min) heart rate (n=1). Furthermore, we excluded women with missing baseline data, dementia at baseline, and missing follow-up or covariate data from our primary analysis (n=60). Our final study population for the main analysis consisted of 493 women for WHIMS-MRI 1 of which 299 women chose to participate in WHIMS-MRI 2 (Figure 1). The sensitivity analysis where we included women with cardiovascular risk factors was also subject to the same exclusion criteria, leaving 1,047 participants for the analysis. Institutional review boards at participating institutions approved all protocols and all participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Study inclusion

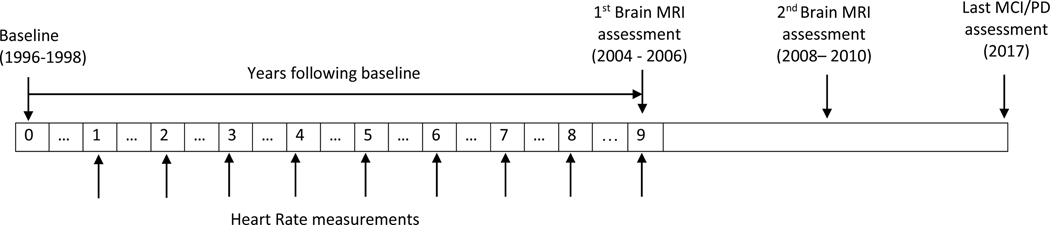

Heart rate readings were taken at each annual clinic visit starting from baseline visit to approximately 6 months to 1 year before the first MRI brain scan (Figure 2). For assessing heart rate, women sat quietly for 5 minutes before a trained observer measured heart rate by palpating the radial pulse for 30 seconds. RHR was calculated using the mean of all available heart rate readings. VVHRV was computed as standard deviation (SD) of heart rate measures or as coefficient of variation (CV) defined as the ratio of SD and mean (CV=SD/mean×100%).3 To capture the longitudinal changes in heart rate measures, both RHR and VVHRV were calculated using the first 3 measures then updated at each subsequent visit until outcome ascertainment occurred.

Figure 2.

Study timetable

Brain MRI scans were performed using a standardized protocol developed by the MRI Quality Control (QC) Center in the Department of Radiology of University of Pennsylvania.5,7,8 MRI scans were obtained with a field of view = 22 cm and a matrix of 256×256. Included were oblique axial spin density/T2-weighted spin echo (TR:3200 ms, TE = 30/120 ms, slice thickness = 3 mm), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) T2-weighted spin echo (TR = 8000 ms, TI = 2000 ms, TE = 100 ms, slice thickness = 3 mm), and oblique axial three-dimensional T1-weighted gradient echo (flip angle = 30 degrees, TR = 21 ms, TE = 8 ms, slice thickness = 1.5 mm) images from the vertex to the skull base parallel to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure (AC-PC) plane.8,9 Brain volumes, measured in cubic centimeters (cm3), were computed using automated computer-based template warping to sum voxels in anatomic regions of interest following a standardized imaging and reading protocol. For detecting ischemic lesions, all brain tissue was grouped into either normal or ischemic gray or white matter tissue using anatomic regions of interest.10 A further more detailed description on the assessment of brain MRI measurements and quantification of brain lesions was previously published.5,7,8

Cognitive impairment was defined as centrally adjudicated mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or probable dementia (PD). Cognitive function was assessed annually from baseline to December 30, 2017 using a neurocognitive assessment protocol based on four phases.6,11–14 In phase 1, all participants were screened annually with Modified Mini-mental State examinations (3MSE). If a participant scored at or below a pre-defined cut point at the 3MSE depending on education, she progressed to further in-person cognitive evaluation by a specialist (phase 2 to phase 4). In phase 2, certified technicians administered a modified Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) battery of neuropsychological tests. Furthermore, a designated informant was administered a questionnaire that assessed observed cognitive and behavioural changes. In phase 3, participants were examined by a specialist who performed a clinical neuropsychiatric evaluation using a standardized protocol and classified the WHIMS participant as having no cognitive impairment, MCI or PD based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria. Women suspected of having PD underwent phase 4 which included a noncontrast computed tomography brain scan and laboratory blood tests to rule out possible reversible causes of cognitive decline. In July 2008, the ‘Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study-Epidemiology of Cognitive Health Outcomes’ (WHIMS-ECHO) succeeded the WHIMS study. A panel of experts at the study coordinating center (Wake Forest School of Medicine) reviewed all WHIMS and WHIMS-ECHO results.

Information on covariates was derived from self-report or by physical measure.15 Clinic blood pressure was assessed at baseline and each annual study visit with the use of standardized procedures.15 Hypertension was defined as a self-report of current drug therapy for hypertension or clinic measurement of SBP ≥ 140mmHg or DBP ≥ 90mmHg. Antihypertensive medication use included ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, calcium blockers, and diuretics. Medication use was assessed at baseline and year 1, 3, 6, 9 by clinic interviewers. Atrial fibrillation was identified through review of ECG data in years 3, 6 and 9 after baseline. The presence of ApoE-ε4 allele was identified by DNA genotyping in a subset of study participants. Data on depression were based on self-report of depressive symptoms. Physical activity was assessed with metabolic equivalent tasks (in hours per week) using a questionnaire on leisure activities.16

Descriptive statistics of demographic characteristics and other covariates are presented as mean (±SD) or frequencies. Each exposure variable of interest was broken down by tertiles based on the distribution of the overall analytic sample. To assess the associations of RHR and VVHRV with brain volumes and brain volume changes, multivariate linear regression models were used with RHR or VVHRV as the main independent variable, adjusting for age, education, physical activity, depression, alcohol intake, coffee intake, presence of ApoE-ε4 allele, WHI Hormone Trial Randomization assignment (HTR arm), mean systolic blood pressure over time, antihypertensive medication use across visits as well as incident cases of cardiovascular disease (CHD, stroke, diabetes and atrial fibrillation) over time. All the covariates included in the model were assumed to have a linear relationship with the outcomes. Time-varying covariates (antihypertensive medication use, CHD, stroke, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation) were used when these variables were updated after WHIMS baseline visit (1996–1999) and before the model outcomes occurred. Main exposure variables were assumed to have a linear relationship with the outcomes of interest. We also looked at the possibility of non-linear trend (e.g. quadratic term) and there was no evidence to suggest a non-linear relationship. Tests of linear trends were performed by using tertiles of exposure variables as continuous variables in the multivariate models.

To address the concern of restricting our study population too much by excluding women with a history of cardiovascular disease or major cardiovascular risk factors, we conducted a sensitivity analysis and repeated our primary analyses with inclusion of women with a history of diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation, hypertension or current smoking at baseline. The multivariate regression models were adjusted for age, education, WHI Hormone Trial Randomization assignment (HTR arm), depression, physical activity, alcohol intake, coffee intake, presence of ApoE-ε4 allele, history of diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation or hypertension, current smoking, mean systolic blood pressure over time, anti-hypertensive medication use over time and incident cardiovascular disease over time.

To address the concern of loss-to-follow-up between WHIMS-MRI 1 and MRI 2 exam, inverse probability weighting was used to adjust for bias in a sensitivity analysis. First, the probability of remaining in the study was estimated through as a function of baseline age, education, smoking alcohol, self-rated health and presence of depression. Then, the reciprocal of this predicted probability of remaining in the study was used as weights in the linear regression model of VVHRV and change in brain and lesion volume such that participants who had a lower probability of remaining in follow-up were given more weight in the analysis.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) of MCI or PD with increasing tertiles of RHR or with increasing tertiles of total lesion volumes adjusting for the aforementioned variables. In the Cox regression models, cases were defined as first occurrence of MCI or PD from WHIMS baseline visit (1996–1999) through December 30, 2017 controls were defined as free of MCI or PD throughout the follow-up period and censored at time of death from any cause or last known contact. In sensitivity analysis, we excluded all MCI or PD cases that occurred before WHIMS-MR 1 exam (2005–2006). Proportional hazard assumption for Cox regression model was accessed and deemed satisfied for the main exposure variable.

All of the statistical tests were 2-sided. To address concern of multiple comparisons, a conservative Bonferroni correction was used and P-values < 0.003 (0.05/15 simultaneous tests) for Table-2 and p-values <0.005 (0.05/10 simultaneous tests) were considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were performed by SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Table 2.

Resting Heart Rate, Heart Rate Variation and brain and lesion volumes in WHIMS-MRI 1 Trial (n=493)

| Exposure by Tertile (beats/min) | n | Mean follow-up (years) | # of HR measures | Total brain volume (cm3) * | Hippocampus volume (cm3) * | Total lesion volume (cm3) *,† | White matter lesion volume (cm3) *,† | Gray matter lesion volume (cm3) *,† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting Heart Rate | ||||||||

| T1 (51–66) | 163 | 7.98 | 7.58 | 873.9 (858.3, 889.6) | 5.93 (5.78, 6.08) | 4.78 (3.39, 6.17) | 3.42 (2.59, 4.24) | 1.36 (0.69, 2.02) |

| T2 (66–71) | 166 | 7.92 | 7.50 | 870.3 (855.0, 885.7) | 5.90 (5.75, 6.04) | 5.87 (4.51, 7.24) | 3.98 (3.17, 4.79) | 1.89 (1.24, 2.55) |

| T3(71–92) | 164 | 8.05 | 7.63 | 875.8 (860.2, 891.3) | 5.80 (5.65, 5.95) | 7.86 (6.48, 9.24) | 5.23 (4.41, 6.05) | 2.64 (1.98, 3.30) |

| p-trend | 0.8332 | 0.1120 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0006 | |||

| p-value (T3 vs. T1) | 0.8350 | 0.1127 | <.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0006 | |||

| Per 5 beats/min | 1.58 (−4.08, 7.24) | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.02) | 1.12 (0.62, 1.62) | 0.63 (0.33, 0.92) | 0.49 (0.25, 0.73) | |||

| Heart Rate Variation | ||||||||

| T1 (1.25–4.96) | 164 | 7.91 | 7.38 | 863.3 (847.9, 878.7) | 5.93 (5.78, 6.08) | 5.45 (4.06, 6.85) | 3.72 (2.89, 4.55) | 1.73 (1.06, 2.39) |

| T2 (4.96–6.85) | 165 | 8.08 | 7.75 | 880.2 (864.7, 895.8) | 5.87 (5.72, 6.01) | 6.39 (4.98, 7.81) | 4.40 (3.56, 5.24) | 2.00 (1.32, 2.67) |

| T3 (6.89–15.3) | 164 | 7.95 | 7.58 | 876.8 (861.5, 892.1) | 5.83 (5.69, 5.98) | 6.71 (5.32, 8.09) | 4.53 (3.71, 5.35) | 2.17 (1.51, 2.84) |

| p-trend | 0.1197 | 0.2300 | 0.1084 | 0.0812 | 0.2313 | |||

| p-value (T3 vs. T1) | 0.1188 | 0.2303 | 0.1081 | 0.0807 | 0.2315 | |||

| Coefficient of variation | ||||||||

| T1 (2.16–7.42) | 164 | 7.95 | 7.47 | 869.2 (853.6, 884.7) | 5.91 (5.76, 6.06) | 6.01 (4.60, 7.42) | 4.08 (3.25, 4.92) | 1.92 (1.25, 2.60) |

| T2 (7.44–10.3) | 165 | 8.03 | 7.67 | 872.4 (856.7, 888.0) | 5.83 (5.68, 5.98) | 6.42 (5.01, 7.84) | 4.45 (3.61, 5.29) | 1.97 (1.30, 2.65) |

| T3 (10.3–22.3) | 164 | 7.96 | 7.57 | 878.0 (862.7, 893.2) | 5.89 (5.74, 6.03) | 6.13 (4.75, 7.51) | 4.13 (3.31, 4.95) | 2.00 (1.34, 2.66) |

| p-trend | 0.3051 | 0.7809 | 0.8810 | 0.9325 | 0.8346 | |||

| p-value (T3 vs. T1) | 0.3066 | 0.7712 | 0.8760 | 0.9241 | 0.8344 | |||

Model adjusted for age, education, WHI Hormone Trial Randomization assignment (HTR arm), depression, physical activity, alcohol intake, coffee intake, presence of ApoE-ε4 allele, mean systolic blood pressure over time, anti-hypertensive medication use over time and incident cardiovascular disease over time

Additionally, adjusted for total brain volume at WHIMS-MRI 1

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of included women are presented in Table 1. Women were followed-up over a median period of 8.0 years with an average of 8 HR assessments prior to the first brain MRI scan.

Table 1.

Analytic study sample of WHIMS-MRI 1 (n=493) and WHIMS-MRI 2 (n=299)

| Variable | WHIMS-MR 1 n (%) or mean (SD) | WHIMS-MR 2 n (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| n=493 | n=299 | |

| Age (years) | 69.3 (3.6) | 68.8 (3.4) |

| >High-school diploma/GED | 348 (71%) | 202(68%) |

| Alcohol, 1 - <7 drinks per week | 155 (31%) | 90 (30%) |

| Physical activities ≥19 METS-hours per week | 96 (19%) | 55 (18%) |

| Presence of ApoE-ε4 allele | 97 (20%) | 58 (19%) |

| Coffee or tea, med servings/day | 2.5 (1.8) | 2.6 (1.8) |

| Presence of Depression | 31 (6%) | 17 (6%) |

| WHI Hormone Trial Randomization assignment (HTR arm) | 246 (50%) | 144 (48%) |

| Antihypertensive medication use across visits | 239 (48%) | 142 (47%) |

| Diagnosed cardiovascular risk factors during follow-up | ||

| Hypertension | 239 (48%) | 142 (47%) |

| Diabetes | 16 (3%) | 11 (4%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (1%) | 1 (0%) |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 6 (1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Stroke | 5 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| MRI brain volumes at first assessment (WHIMS-MRI 1) | ||

| Total brain volume (cm3) | 868.12 (78.15) | 868.37 (73.08) |

| Hippocampus volume (cm3) | 5.84 (0.76) | 5.97 (0.72) |

| Total lesion volume (cm3) | 5.90 (6.98) | 5.51 (6.99) |

| White matter lesion (cm3) | 4.07 (4.14) | 3.92 (4.28) |

| Grey matter lesion (cm3) | 1.83 (3.32) | 1.59 (2.93) |

Using data from the first brain MRI assessment (WHIMS MRI 1), high RHR (71–92 beats/min) was found to be associated with higher ischemic lesion volumes, white and gray matter ischemic lesion volumes compared to low RHR (51–66 beats/min) whereas no relationships with total brain volume or hippocampus volume were detected (Table 2). Higher tertiles of VVHRV were not related to lower brain volumes or lesion volumes.

In longitudinal brain MRI analyses (WHIMS MRI 1 and WHIMS MRI 2), high compared to low RHR was associated with increases in lesion volumes but not with changes in brain or hippocampus volumes (Table 3). VVHRV did not show any significant association with brain volume changes over time (Supplemental Table 1). To address the concern of loss-to-follow-up (follow-up rate between MRI-1 and MRI-2 was 299/493=61%), we conducted sensitivity analyses using inverse probability weighting (Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental Table 3). Results from these were not materially different from those from unweighted analyses.

Table 3.

Resting Heart Rate and change in brain and lesion volumes between WHIMS-MRI 1 and WHIMS-MRI 2 Trial (n=299)

| Resting Heart Rate by Tertile (beats/min) | n | Mean follow-up (years) | # of HR measures | Total brain volume (cm3) * | Hippocampus volume (cm3) * | Total lesion volume (cm3) *,† | White matter lesion volume (cm3) *,† | Gray matter lesion volume (cm3) *,† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall change in brain and lesion volumes | ||||||||

| T1 (51–66) | 99 | 4.71 | 7.58 | −20.3 (−25.0, −15.6) | −0.42 (−0.53, −0.31) | 4.28 (2.84, 5.73) | 3.17 (2.30, 4.04) | 1.11 (0.30, 1.93) |

| T2 (66–71) | 102 | 4.77 | 7.50 | −18.7 (−23.3, −14.1) | −0.32 (−0.42, −0.21) | 5.11 (3.70, 6.53) | 3.40 (2.55, 4.25) | 1.71 (0.91, 2.51) |

| T3 (71–92) | 98 | 4.70 | 7.63 | −17.0 (−21.5, −12.5) | −0.32 (−0.42, −0.22) | 6.20 (4.81, 7.59) | 3.86 (3.03, 4.70) | 2.34 (1.55, 3.12) |

| p-trend | 0.2065 | 0.0985 | 0.0167 | 0.1487 | 0.0069 | |||

| p-value (T3 vs. T1) | 0.2072 | 0.1024 | 0.0168 | 0.1480 | 0.0070 | |||

| Per 5 beats/min | 1.22 (−0.49, 2.94) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.07) | 0.86 (0.34, 1.38) | 0.40 (0.08, 0.71) | 0.46 (0.16, 0.76) | |||

| Annual change in brain and lesion volumes | ||||||||

| T1 (51–66) | 99 | 4.71 | 7.58 | −4.45 (−5.45, −3.45) | −0.09 (−0.11, −0.07) | 0.94 (0.64, 1.25) | 0.70 (0.51, 0.89) | 0.24 (0.08, 0.41) |

| T2 (66–71) | 102 | 4.77 | 7.50 | −4.00 (−4.98, −3.02) | −0.07 (−0.09, −0.04) | 1.10 (0.81, 1.40) | 0.73 (0.55, 0.92) | 0.37 (0.20, 0.54) |

| T3 (71–92) | 98 | 4.70 | 7.63 | −3.72 (−4.68, −2.76) | −0.07 (−0.09, −0.05) | 1.33 (1.04, 1.63) | 0.84 (0.66, 1.02) | 0.50 (0.33, 0.66) |

| p-trend | 0.1884 | 0.1166 | 0.0212 | 0.1850 | 0.0072 | |||

| p-value (T3 vs. T1) | 0.1904 | 0.1217 | 0.0212 | 0.1833 | 0.0073 | |||

| Per 5 beats/min | 0.25 (−0.12, 0.61) | 0.01 (−0.00, 0.01) | 0.18 (0.07, 0.29) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.15) | 0.10 (0.04, 0.16) | |||

Model adjusted for age, education, WHI Hormone Trial Randomization assignment (HTR arm), depression, physical activity, alcohol intake, coffee intake, presence of ApoE-ε4 allele, mean systolic blood pressure over time, anti-hypertensive medication use over time and incident cardiovascular disease over time.

Additionally adjusted for total brain volume at WHIMS-MRI 1.

In analyses of cognitive functioning (WHIMS MRI 1), large compared to small brain lesion volumes were found to be significantly associated with later incident cognitive impairment (Table 4). Neither RHR nor VVHRV showed significant associations with cognitive impairment (Supplemental Table 4 and Supplemental Table 5).

Table 4.

Total Lesion Volumes and Risk of Cognitive Impairment (HR, 95% CI) in WHIMS-MRI 1 Trial (n=435)*

| Total lesion volume | N | Follow-up time (years) | # of HR measures | MCI or PD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of cases‡ | HR (95% CI)§ | ||||

| Tertile 1 | 145 | 16.70 | 7.60 | 24 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Tertile 2 | 145 | 16.05 | 7.62 | 31 | 1.59 (0.90, 2.82) |

| Tertile 3 | 145 | 15.28 | 7.54 | 36 | 2.02 (1.18, 3.47) |

| p-trend | 0.0109 | ||||

| Per 5% Increase | 1.34 (0.31, 5.88) | ||||

HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, confidence interval

Individuals with MCI or PD diagnosis before WHIMS-MRI 1 brain scan (n=10) and those lost to follow-up before WHIMS-MRI 1 visit (n=48) were excluded. The study sample dropped from 493 to 435.

Incident MCI and PD cases ascertained from MRI-1 (2004–2006) through December 30, 2017.

Model adjusted for age, education, WHI Hormone Trial Randomization assignment (HTR arm), depression, physical activity, alcohol intake, presence of ApoE-ε4 allele, mean systolic blood pressure over time, anti-hypertensive medication use over time and incident cardiovascular disease over time.

In sensitivity analyses we repeated our analyses by including women with a history of cardiovascular disease or major risk factors. Our main results were consistent with the main reported findings above (Supplemental Tables 6 to 9).

DISCUSSION

In a cohort of older women higher RHR was associated with increases in brain ischemic lesion volumes over time. Large brain lesion volume, but not RHR or VVHRV, was subsequently found to be associated with cognitive impairment.

There may be several explanations for these findings. Women with higher RHR may be more likely to suffer from asymptomatic (paroxysmal) episodes of atrial fibrillation which consequently predispose these women to subclinical brain damage. Unfortunately, these episodes are hard to catch with regular ECG measurements and our longitudinal study may have missed some cases even though ECGs were recorded at three time points. Although from a clinical standpoint this explanation seems intuitive, previous studies have been controversial regarding the relation of RHR and incident atrial fibrillation. Whereas data from the trials ONTARGET and TRANSCEND or the Tromsø study point to an increased risk for atrial fibrillation in individuals with low RHR (< 60 or 50/min), results from the ARIC Study or the LIFE Study indicate a higher risk with higher RHR (≥ 80/min).17–20 These findings correspond to prior clinical observations that alterations of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system are implicated in initiating paroxysmal atrial fibrillation events.21 Second, elevated RHR, as a surrogate for cardiac autonomic function, has been described to be an independent risk factor for blood pressure changes and hypertension.22 Concomitant vascular structural changes including arterial stiffness, endothelial dysfunction and subclinical inflammation most likely also play an additional role. Recently, long-term elevated RHR has been related to arterial stiffness, a finding similar to reports on long-term visit-to-visit blood pressure variability.23–25 Nonetheless, when we additionally adjusted our RHR results for pulse pressure, a measure of aortic compliance, the main findings did not significantly change (data not shown). When we correlated RHR and VVHRV with mean systolic blood pressure or visit-to-visit systolic blood pressure variability, none or only weak correlations were detected in our study population consisting of relatively healthy women without cardiovascular disease at baseline (data not shown). In fact, only 3% of our sample developed diabetes, 1% CHD during follow-up, which is substantially lower than the rate in the general population of the similar age group. When we looked at the one-to-one relationship of hypertension, diabetes, CHD and stroke with total lesion volume, only hypertension was related to total lesion volume (p-value=0.031). Finally, alternate explanations for our findings may point to the presence of other potentially not well documented or detected cardiometabolic risk factors. One such factor may be obstructive sleep apnea which has been shown to be a predictor of white matter hyperintensities and stroke.26,27 Interestingly, during the follow-up of our study snoring more than three times a week was reported more in women with higher RHR which may be indicative for an underlying sleep disorder (data not shown).

The relationship between brain lesion volume and subsequent cognitive dysfunction is well established. Among existing most recent evidence, in the Swedish National study on Aging and Care, a population of elderly Swedish individuals with high prevalence of hypertension, cerebral microvascular lesion loads were shown to be strongly associated with cognitive decline and dementia over a 9-year follow-up period.28 Our results complement these findings as we detected a strong relationship between lesion volume and cognitive impairment even in a cohort consisting of relatively healthy, well-educated older women with no hypertension or diabetes at baseline over approximately 15-years of follow-up. However, we did not observe a higher risk for cognitive impairment in individuals with higher RHR or VVHRV. Interestingly, these results are comparable to results from the SPRINT trial. Whereas an intensive blood pressure control was associated with a smaller increase in cerebral white matter lesion volume in the SPRINT trial, this did not result in a significant reduction in the risk of probable dementia.29,30

Strengths of this analysis include a well-structured cohort study with long-time follow-up including longitudinal brain MRI assessments, confirmed and adjudicated assessment of MCI and PD and adjustment for several confounding factors. Nonetheless, there are several limitations. Selection bias and residual confounding are present, and generalizability is limited as we only included white, well-educated postmenopausal women. We chose to first restrict our analysis to a study population without documented cardiovascular disease or major risk factors at baseline as the risk of cognitive impairment and brain lesions is greater among those with longer duration and more severe exposure to cardiovascular disease and thus the risk of confounding is more imminent. We thereafter conducted sensitivity analyses and additionally included women with cardiovascular disease or major risk factors to compare our findings and to be more representative of the general older population. Another limitation is that our classification of cognitive outcomes which was triggered by a low 3 MSE score has the potential to underestimate the diagnosis of ‘MCI’, especially MCI with executive dysfunction only. Finally, a considerable proportion of women refused to participate in a second brain MRI assessment which limits longitudinal analysis.

In conclusion, our findings show an association between elevated RHR and ischemic brain lesions, probably due to underlying subclinical disease processes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the WHI participants, clinical sites, investigators, and staff for their dedicated efforts. A list of WHI investigators is available online at: https://www-whi-org.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/WHI-Investigator-Short-List.pdf

Sources of Funding

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HHSN268201600003C, and HHSN268201600004C.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang D, Wang W, Li F. Association between resting heart rate and coronary artery disease, stroke, sudden death and noncardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2016;188:E384–E392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohm M, Cotton D, Foster L, Custodis F, Laufs U, Sacco R, Bath PM, Yusuf S, Diener HC. Impact of resting heart rate on mortality, disability and cognitive decline in patients after ischaemic stroke. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2804–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohm M, Schumacher H, Leong D, Mancia G, Unger T, Schmieder R, Custodis F, Diener HC, Laufs U, Lonn E, Sliwa K, Teo K, Fagard R, Redon J, Sleight P, Anderson C, O’Donnell M, Yusuf S. Systolic blood pressure variation and mean heart rate is associated with cognitive dysfunction in patients with high cardiovascular risk. Hypertension 2015;65:651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung LY, Bartz TM, Rice K, Floyd J, Psaty B, Gutierrez J, Longstreth WT Jr., Mukamal KJ. Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Measures Associated With Increased Risk of Covert Brain Infarction and Worsening Leukoaraiosis in Older Adults. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:1579–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaramillo SA, Felton D, Andrews L, Desiderio L, Hallarn RK, Jackson SD, Coker LH, Robinson JG, Ockene JK, Espeland MA. Enrollment in a brain magnetic resonance study: results from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study (WHIMS-MRI). Acad Radiol 2007;14:603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shumaker SA, Reboussin BA, Espeland MA, Rapp SR, McBee WL, Dailey M, Bowen D, Terrell T, Jones BN. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS): a trial of the effect of estrogen therapy in preventing and slowing the progression of dementia. Control Clin Trials 1998;19:604–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coker LH, Espeland MA, Hogan PE, Resnick SM, Bryan RN, Robinson JG, Goveas JS, Davatzikos C, Kuller LH, Williamson JD, Bushnell CD, Shumaker SA. Change in brain and lesion volumes after CEE therapies: the WHIMS-MRI studies. Neurology 2014;82:427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Jaramillo SA, Hirsch C, Stefanick ML, Murray AM, Ockene J, Davatzikos C. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and regional brain volumes: the WHIMS-MRI Study. Neurology 2009;72:135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espeland MA, Bryan RN, Goveas JS, Robinson JG, Siddiqui MS, Liu S, Hogan PE, Casanova R, Coker LH, Yaffe K, Masaki K, Rossom R, Resnick SM. Influence of type 2 diabetes on brain volumes and changes in brain volumes: results from the Women’s Health Initiative Magnetic Resonance Imaging studies. Diabetes Care 2013;36:90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lao Z, Shen D, Liu D, Jawad AF, Melhem ER, Launer LJ, Bryan RN, Davatzikos C. Computer-assisted segmentation of white matter lesions in 3D MR images using support vector machine. Acad Radiol 2008;15:300–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Shumaker SA, Brunner R, Manson JE, Sherwin BB, Hsia J, Margolis KL, Hogan PE, Wallace R, Dailey M, Freeman R, Hays J, Women’s Health Initiative Memory S. Conjugated equine estrogens and global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA 2004;291:2959–2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, Gass ML, Stefanick ML, Lane DS, Hays J, Johnson KC, Coker LH, Dailey M, Bowen D, Investigators W. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289:2663–2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, Rapp SR, Thal L, Lane DS, Fillit H, Stefanick ML, Hendrix SL, Lewis CE, Masaki K, Coker LH, Women’s Health Initiative Memory S. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA 2004;291:2947–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, Hendrix SL, Jones BN 3rd, Assaf AR, Jackson RD, Kotchen JM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Wactawski-Wende J, Investigators W. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289:2651–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHI. Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trials 1998;19:61–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE Jr.,, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang W, Alonso A, Soliman EZ, O’Neal WT, Calkins H, Chen LY, Diener-West M, Szklo M. Relation of Resting Heart Rate to Incident Atrial Fibrillation (From ARIC [Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities] Study). Am J Cardiol 2018;121:1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okin PM, Wachtell K, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Lindholm LH, Dahlof B, Hille DA, Nieminen MS, Edelman JM, Devereux RB. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in relation to changing heart rate over time in hypertensive patients: the LIFE study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2008;1:337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohm M, Schumacher H, Linz D, Reil JC, Ukena C, Lonn E, Teo K, Sliwa K, Schmieder RE, Sleight P, Yusuf S. Low resting heart rates are associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with vascular disease: results of the ONTARGET/TRANSCEND studies. J Intern Med 2015;278:303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morseth B, Graff-Iversen S, Jacobsen BK, Jorgensen L, Nyrnes A, Thelle DS, Vestergaard P, Lochen ML. Physical activity, resting heart rate, and atrial fibrillation: the Tromso Study. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2307–2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen MJ, Zipes DP. Role of the autonomic nervous system in modulating cardiac arrhythmias. Circ Res 2014;114:1004–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tjugen TB, Flaa A, Kjeldsen SE. High heart rate as predictor of essential hypertension: the hyperkinetic state, evidence of prediction of hypertension, and hemodynamic transition to full hypertension. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009;52:20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen S, Li W, Jin C, Vaidya A, Gao J, Yang H, Wu S, Gao X. Resting Heart Rate Trajectory Pattern Predicts Arterial Stiffness in a Community-Based Chinese Cohort. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin B, Viera AJ, Muntner P, Plassman BL, Edwards LJ, Adair LS, Popkin BM, Mendez MA. Visit-to-Visit Variability in Blood Pressure Is Related to Late-Life Cognitive Decline. Hypertension 2016;68:106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimbo D, Shea S, McClelland RL, Viera AJ, Mann D, Newman J, Lima J, Polak JF, Psaty BM, Muntner P. Associations of aortic distensibility and arterial elasticity with long-term visit-to-visit blood pressure variability: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Hypertens 2013;26:896–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim H, Yun CH, Thomas RJ, Lee SH, Seo HS, Cho ER, Lee SK, Yoon DW, Suh S, Shin C. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for cerebral white matter change in a middle-aged and older general population. Sleep 2013;36:709–715B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redline S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, Shahar E, O’Connor GT, Resnick HE, Diener-West M, Sanders MH, Wolf PA, Geraghty EM, Ali T, Lebowitz M, Punjabi NM. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang R, Laveskog A, Laukka EJ, Kalpouzos G, Backman L, Fratiglioni L, Qiu C. MRI load of cerebral microvascular lesions and neurodegeneration, cognitive decline, and dementia. Neurology 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasrallah IM, Pajewski NM, Auchus AP, Chelune G, Cheung AK, Cleveland ML, Coker LH, Crowe MG, Cushman WC, Cutler JA, Davatzikos C, Desiderio L, Doshi J, Erus G, Fine LJ, Gaussoin SA, Harris D, Johnson KC, Kimmel PL, Kurella Tamura M, Launer LJ, Lerner AJ, Lewis CE, Martindale-Adams J, Moy CS, Nichols LO, Oparil S, Ogrocki PK, Rahman M, Rapp SR, Reboussin DM, Rocco MV, Sachs BC, Sink KM, Still CH, Supiano MA, Snyder JK, Wadley VG, Walker J, Weiner DE, Whelton PK, Wilson VM, Woolard N, Wright JT Jr., Wright CB, Williamson JD, Bryan RN. Association of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control With Cerebral White Matter Lesions. JAMA 2019;322:524–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, Auchus AP, Bryan RN, Chelune G, Cheung AK, Cleveland ML, Coker LH, Crowe MG, Cushman WC, Cutler JA, Davatzikos C, Desiderio L, Erus G, Fine LJ, Gaussoin SA, Harris D, Hsieh MK, Johnson KC, Kimmel PL, Tamura MK, Launer LJ, Lerner AJ, Lewis CE, Martindale-Adams J, Moy CS, Nasrallah IM, Nichols LO, Oparil S, Ogrocki PK, Rahman M, Rapp SR, Reboussin DM, Rocco MV, Sachs BC, Sink KM, Still CH, Supiano MA, Snyder JK, Wadley VG, Walker J, Weiner DE, Whelton PK, Wilson VM, Woolard N, Wright JT Jr, Wright CB. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019;321:553–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.