Abstract

Community teaching physicians (i.e., community preceptors) have assumed an important role in medical education. More than half of medical schools use community settings to train medical students. Whether community preceptors are well prepared for their teaching responsibilities is unknown. In addition, best practice for faculty development (FD) of this population of preceptors has not been defined. The authors conducted a narrative review of the literature to describe FD programs for community preceptors that may be helpful to medical schools for future planning. Many databases were searched from their establishment to May 2022. Studies that described FD programs for community preceptors were included. Data were organized according to program aim, duration, setting, participants, content, and outcomes. The Communities of Practice theoretical framework was used to present findings. From a total of 6308 articles, 326 were eligible for full review, 21 met inclusion criteria. Sixty-seven percent (14/21) conducted a needs assessment; 57% (12/21) were developed by the medical school; 81% (17/21) included only community preceptors. Number of participants ranged from six to 1728. Workshops were often (24%, 5/21) used and supplemented by role-play, online modules, or instructional videos. Few programs offered opportunities to practice with standardized learners. Content focused primarily on teaching skills. Five programs offered CME credits as an incentive for engagement. Participant surveys were most often used for program evaluation. Learner evaluations and focus groups were used less often. Participants reported satisfaction and improvement in teaching skills after attending the program. Faculty development for community preceptors is primarily delivered through workshops and online materials, although direct observations of teaching with feedback from FD faculty and learners may be more helpful for training. Future studies need to focus on the long-term impact of FD on community preceptors’ teaching skills, identity formation as medical educators, and student learning.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08026-5.

Community teaching physicians have assumed an important role in medical education. More than half of medical schools use regional campuses and community settings to train their medical students.1 The need for training future physicians to better meet societal needs and expectations has prompted medical schools to shift student learning to community settings.2, 3 At these sites that are often rural or urban, medical students learn from community practicing physicians (i.e., community preceptors) and better understand how social determinants of health can impact patients and communities.4, 5 These experiences can be powerful and may have a lasting effect on medical students’ professional identity formation and career choices.6

The value of community preceptors in medical education has been increasingly recognized by many organizations.7, 8 Community-based medical schools, in particular, depend on these physicians to fulfill their educational mission and provide clinical training to their students.9 The Alliance of Academic Internal Medicine has called attention to the important roles of community preceptors and need for faculty development (FD) programs that align with their needs and are mindful of their time constraints and geographic location.10 Furthermore, medical school accreditation standards require comparability of student learning experiences across training sites demanding teaching physicians who are well prepared for their educator roles.11

However, whether community preceptors are well prepared for their teaching responsibilities is unknown. In addition, best practice for FD of this population of preceptors has not been defined.12 Many organizations have expressed concerns about the shortage of community preceptors and their level of preparedness to provide high-quality educational experiences.7, 8, 13, 14 According to a national survey of Family Medicine clerkship directors, FD programs for community preceptors are unstructured or absent, and best practices are lacking.13 Community preceptors are often uncertain about their teaching skills and find teaching to be stressful and difficult.15 Time constraints, high productivity demands, disinterested learners, and lack of training as educators are additional barriers to teaching.14

Given the increasingly important role of community physicians in the educational mission of medical schools, it becomes important to better understand what FD resources are available to them and the scope and outcomes of these FD resources. The literature in this area is less explored since previous studies have primarily focused on the FD of academic teaching faculty. To explore this area of medical education, we conducted a narrative review of the literature with the aim to describe FD programs and identify any gaps that maybe helpful to medical schools and FD developers in the preparation of these teaching physicians for their roles as educators. We used the Communities of Practice (CoP) theoretical framework to present our findings.16, 17 We found CoP relevant to community preceptors who may aspire to join the community of medical educators and acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to move from “peripheral participation to full membership” (p. 186). Our review will explore the role of FD in this process.17

METHOD

Review Methodology and Electronic Database Searches

In our review, we followed a narrative review approach18 by conducting a systematic review of the literature on FD for community preceptors and narratively synthesized our findings. The scope of our review was broad to explore this area of FD and identify areas that could potentially be addressed in future research. Our overarching research question was:

What is the present status of FD for community preceptors?

For our review, we used MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE, Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Social Science & Humanities), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), both in the Cochrane Library, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) using the ProQuest platform, and ClinicalTrials.gov for ongoing or recently completed relevant trials. Our search spanned from the establishment of each database to May 31, 2022.

We used variations of the following controlled vocabulary and keywords: faculty development, continuing education, medical schools, and Academic Medical Centers (AMCs). We also used the search terms (community OR clinical OR volunteer OR adjunct) AND (faculty OR teacher OR preceptor OR educator OR instructor) AND (development OR education OR train) AND (continuing OR professional OR in-service training) (Appendix 1). We included all the studies in the initial search regardless of their methodological approach and did not apply any language restrictions.

Data Collection and Analysis

We used standard Cochrane methodological procedures19 and exported our search results into a bibliographic citation management system (Endnote 20, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA). The co-author (IA) read the titles and abstracts that were retrieved from the initial database search and selected articles for full review. Two co-authors (IA and JS) conducted the full-article review independently and agreed on the articles that were selected for final review. IA and JS summarized and collated data from the final articles separately and subsequently compared their results. Any disagreements were discussed with a third co-author (RB) until consensus was reached. For the purpose of this review, a community preceptor was defined as a practicing physician (e.g., MD or DO) who teaches medical students, residents, fellows, and other healthcare profession students at a community setting, and has an affiliate clinical faculty appointment at the medical school or serves as a volunteer.

During the review, we excluded studies that (1) described FD programs for academic faculty only, including clinician educators, physician scientists, basic science educators, and participants from other health professions (e.g., dentists, pharmacists, physician assistants, nurses); (2) did not describe their participants as community-based; (3) focused on the development, evaluation, or the developers of FD programs and not on the participants; (4) did not include a description of the FD program; and (5) described FD programs with focus on continuous medical education (CME) and not teaching skills. In addition, non-peer reviewed, non-English language publications, opinion papers, commentaries, perspectives, letters, editorials, and review articles were excluded.

After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, we (IA and JS) reviewed all eligible articles and collected information about the characteristics of each FD program, including aim, duration, setting (e.g., organization, community, or university), participants, program description, and outcomes (when available). We organized the data in a table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Articles on Faculty Development for Community Preceptors Included in the Synthesis of the Literature

| First author, year of study | Design | Aim | Program setting and sponsorship | Duration | Participants | Needs assessment | Program design and funding | Evaluation | Study results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hitchcock, 1980 (ref. #31) | Posttest only | Develop, implement, and evaluate a model of clinical teaching to improve teaching skills of faculty in family practice programs | Family Practice FD Center of Texas (cooperative venture of 14 residency programs and departments of FM in 6 medical schools) | One weekend | 119 participants (full- and part-time, voluntary faculty) | Yes |

Weekend workshop (8 h on Saturday and 4 h on Sunday) on teaching skills 12 CME credits by the American Academy of Family Practice Funding: Not reported |

Post-workshop survey | Quality and suitability of workshop (both achieved based on survey responses) |

| Stuart, 1980 (ref. #29) | Pre/posttest | Develop an innovative and comprehensive program to prepare community preceptors for their teaching roles | Single community hospital FM residency program affiliated with a medical school in New Jersey; sponsored by department of FM at the medical school | Not specified | 8 part-time preceptors in a consultative capacity | Yes |

Preceptors observed residents on a regular basis and scheduled feedback sessions directly following resident-patient encounters observed with a trained faculty facilitator Videotaped recordings of resident patient interactions and the preceptor-resident interactions were used to enhance the feedback and assess effectiveness of the program Funding: Medical school covered 1st year: 2/3 of cost through grant funding 2nd year: 1/3 of cost |

Videotapes were reviewed by faculty facilitator and participant who received feedback Videotapes were reviewed and scored by the faculty facilitator and blindly by a psychologist Informal feedback from participants and residents |

Scores before and after the intervention show significant preceptor improvement overtime (p <.001); both evaluators scored assessment and all categories of preceptor-resident relationship as showing improvement Participants reported great satisfaction with the program; feedback from residents suggested that the program had a positive impact on their learning |

| Levy, 1998 (ref. #36) | Posttest only | Develop and implement an interactive videoconferencing system as an alternative for FD of community preceptors | Single institution (U. of Iowa); sponsored by department of FM | Not specified | 21 FM Community Preceptors | No |

Use of video-conferencing to present a workshop on basic teaching skills in the outpatient setting (“Effective Clinical Teaching” program) at various sites Funding: State subsidies and internal CME grants |

Participants and workshop presenters completed a post-video conferencing survey |

Participants rated: satisfaction, convenience, quality Presenters rated: ability to communicate with participants, quality of interaction, convenience |

| Bing-You, 1999 (ref. #39) | Pilot study Qualitative | Develop a pilot program to foster FD for community preceptors through collegial site visits | Maine Practice Network | 1 year | 6 community preceptors | No |

2 collegial site visits to another site with emphasis on discussing teaching practices (preceptor reflection on teaching issues, meeting of site visitor with student and observation of student encounter with patient, lunch of site visitor with preceptor and student, and/or others) Site visitors had a half-day orientation meeting as a group (with mini-lectures, small group discussion, and brainstorming) Site visitors sent a letter back to the preceptor providing feedback Funding: Foundation grant (covered site visitors travel expenses and stipend) |

1 month after, a research assistant conducted a phone interview with the preceptors who had been visited | 4 themes: promoting reflection, approaches to teaching, collegiality, and quality assurance. Participants thought the site visitor benefitted them the most. Several preceptors indicated they would attempt alternative teaching methods learned |

| Skeff, 1999 (ref. #30) | Pre/posttest | To examine the feasibility and value of an American College of Physicians–sponsored regional teaching improvement program for community preceptors | Regional workshops (Connecticut, New Hampshire/ Vermont, New York, Ohio, and Virginia) | 1 month | 282 (49% community based, 51% university based) | Yes |

5 regional (Connecticut, New Hampshire/Vermont, New York, Ohio, and Virginia) 1- to 2-day teaching-improvement workshops (seven 2-h seminars in a small group instructional format with 6–8 participants); Stanford Faculty Development Program trained facilitators Topics: promoting a positive learning climate, communicating educational goals, and providing feedback Funding: Charitable Trusts |

Pre- and post-intervention surveys (74% response rate) |

At all sites, participants evaluated the program as highly useful; indicated program had a positive effect on their knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward office-based teaching, increased their teaching ability (p < 0.001) and their sense of integration with their affiliated institution (p <0.001) Self-reported significant changes in behaviors pertaining to fostering a positive learning climate, communicating goals, providing feedback, and general teaching ability (p <0.001) |

| Ferguson, 2003 (ref. #27) | Posttest only | Development a cultural competence curriculum integrated into the training of community preceptors | 15 medical schools in New England and New York; sponsored by the Community FD Center of U. Mass medical school | 18 months | 137 participants | Yes |

“Teaching the Culture of the Community” consisted of four 2.5 hours modules/ workshops, including interactive lectures and small group role-play exercises on cultural needs assessment, patient-centered interviewing, feedback on cultural issues and use of the community to enhance cultural understanding Funding: Not reported |

Post-workshop surveys |

Workshops received positive ratings (average 4/out of 5); statistically significant improvement in the overall value of the program and the clarity of objectives Before workshop #3, 21.4% of participants self-reported changes to their teaching behaviors related to culture components After workshop #3, 30.2% of respondents self-reported intentions to work on culture-related teaching behaviors |

| Langlois & Thach, 2003 (ref. #40) | Posttest only | To develop a collection of materials and techniques to overcome obstacles encountered in providing FD to community preceptors | Mountain Area Health Education Center, NC (Preceptor Development Program) | 3-year | 491 community preceptors from four NC U., 19 programs, and 143 courses | Yes |

“Preceptor Development Program”: materials on nine core FD topics provided in a variety of formats: seminars, monographs, web modules, and one-page summary “thumbnails”; free to FD developers and customizable Core topics: setting expectations, giving feedback, and evaluating; teaching styles, One-Minute-Preceptor; teaching when time is limited; difficult learner; teaching at bedside Optional CME credit; minimal or no registration fee Funding: HRSA Family Medicine Faculty Development Training Grant |

Post-intervention surveys |

Low usage of CME; 19% response rate Barriers: time and busy practice; overall satisfied with the materials, although small sample size did not allow to detect any statistically significant differences; respondents seemed pleased with modules overall, their relevance to preceptors’ teaching, and the extent to which they were easy to use |

| Stone, 2003 (ref. #37) | Pre/posttest | Develop and test a performance-based instrument (OSTE) to evaluate preceptor proficiency in delivering feedback | Single institution (U. of Mass); sponsored by the Community FD Center of U. Mass | Not specified | 56 FM, IM, Peds preceptors from 17 med schools participated in workshop and 50 completed OSTE | No |

2-day workshop using an observation and feedback module (part of Teaching of Tomorrow series; 4 workshops) with an OSTE and written test Funding: Macy Initiative in Health Communication |

-OSTE checklist and rating scale completed by students -Written test taken by participants |

-Difference in the development of an action plan between pre/post-groups (p = .03) -Trends in the post-group: preceptors prioritizing and limiting the amount of feedback, decreased feedback on medical content and increased on doctor-patient communication -No differences in the written test performance between groups |

| Baldwin, 2004 (ref. #21) | Pre/posttest | Develop a FD program to help community faculty develop their computer skills | Single institution (UT Galveston) | 3 years | 181 preceptors (22% of total) | Yes |

The Teaching and Learning Through Educational Technology (TeLeTET) program, included conferences on: - Basic Educational Technology Skills - Online Case-Based Learning - Clinical CME with Technology Enhancements (included 4 modules) Workshops on: - Using Personal Digital Assistants in a Teaching Practice - Portable, modular Web-Based Curricular Materials Funding: Grants (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Generalist Physician Initiative grant, State of Texas Telecommunications Infrastructure Fund and Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration) |

Surveys | Overall high satisfaction with the program |

| Armson, 2005 (ref. #20) | Posttest only | Develop a FD program (The Cabin Fever retreat) with the overarching goal of supporting the recruitment and retention efforts of the Alberta Rural Physician Action Plan to stabilize manpower in underserviced areas | Single institution (U. of Calgary) | Every year (3 day-retreat) | 140 FM and specialty rural preceptors | Yes |

Retreat objectives: - Context-specific preparation of preceptors for their roles in teaching and evaluation of clinical skills - Networking Plenary followed by small group workshops (3 streams: for novice, experienced teachers, and those interested in theoretical foundations of education); participants can self-select and cross over streams; rural preceptors facilitate or co-facilitate workshops Registration was free Funding source: Not reported |

Post-intervention surveys | Retreat format, content, and practice were very highly rated. |

| Wilkes, 2006 (ref. #25) | Mixed methods | Develop a novel FD program to augment community preceptor teaching skills and practice behaviors | Single institution (UCLA); sponsored by the Dean’s office | 3 years | 37 preceptors (total of 90 preceptors in Doctoring course) | Yes |

Doctoring for Community Preceptors (DCP): small groups led by “opinion leaders” (trained community preceptors); topics: teaching skills and tools, EBM, reflection, communication skills; use of standardized medical students - Year 1: training opinion leaders - Year 2: FD for community preceptors; monthly small groups for 10 months; videos, detailed tutor guides for preparation before sessions - Year 3: program evaluation 18 CME credits Funding source: Private Foundation |

Participant surveys post each session; written evaluations of the program and focus groups with opinion leaders; focus groups with standardized medical students (SMS); surveys of MS3 who worked with preceptors |

- Opinion leaders rated program as the most effective they had been involved in - Preceptors rated the training sessions highly and self-reported improvement of their teaching skills - SMS found the experience extremely valuable; they improved their clinical knowledge; learned teaching skills; learned about the diverse approaches of community preceptors in the care of patients - MS3 students ratings did not change pre- and post-intervention |

| Willett, 2006 (ref. #26) |

Pilot study Posttest only |

Development and use of an audiotape for community preceptors to improve their teaching technique | Single institution (UMDNJ) | 24 months |

53 preceptors; 28 community-based and 25 academic; 37 preceptors completed entire 2-year program |

Yes |

A short audiotape on strategies for providing student independence in the office setting was made and distributed to preceptors of MS4 Funding source: Not reported |

Students completed post-clerkship evaluations before and after tape distribution rating preceptor |

- Student shadowing experiences significantly declined post-intervention (p=.03) - In the preceptor “noncompliant” group shadowing significantly declined post-intervention (p<.001) |

| Bramson, 2007 (ref. #22) | Posttest only | To address preceptor needs for FD materials that integrate medical content, technology, and teaching skills | Single institution (Texas A&M University); sponsored by the Department of Family and Community Medicine | 3 years | 144 FM preceptors | Yes |

• 10 CME sessions (teaching and technology skills) • Listserve • Electronic Discussion group • Orientation videotape on precepting • CD-ROM on teaching skills and evaluation • On-site technology support Funding source: Not reported |

Web surveys (44/144, 31%) |

- CME sessions were useful (93%) - Participants used listserv to communicate with the department, but not with other preceptors (85%) - Technology support positively impacted precepting (80%) as did CD-ROM (80%) - Participants did not integrate electronic information into real-time teaching and clinical care |

| Gjerde, 2008 (ref. #35) | Posttest only | Assess the long-term academic and professional outcomes for clinical preceptors who completed the part-time FD program | Single institution (U. of Wisconsin); sponsored by the Department of FM | 1 year | 20 Community- and university-based preceptors per year | No |

5 weekend workshops on evidence-based medicine, teaching skills, technology tools, doctor-patient communication, quality improvement, and advocacy. Each fellow worked with faculty mentors on an applied project and presented it on the final weekend Funding source: HRSA grant (covered registration as well) |

Surveys of program graduates from 1996–2003 (n=100); 80% response rate |

90% of respondents were teaching medical students and residents; self-reported improvement in teaching skills, clinical skills, intrapersonal growth, scholarly and academic outcomes, self-confidence, interdisciplinary networking, and mentoring. 91% recommended the program to others |

| Gallagher, 2011 (ref. #38) | Qualitative | Develop and implement a peripatetic educational program for community preceptors to teach them the skills needed for their teaching roles | Single institution (U. of Otago, New Zealand); sponsored by the Medical Education Unit | 2 years | Not specified | No |

Delivered in various formats, including presentations to large groups; 1-h small group workshops; 2-h workshops; and 4-h early evening workshops Funding source: Not provided |

Participant reflections (no information on number of participants, analysis of data, timing of reflections) | Participants wished to be valued by and connected to the university more than currently; attendance did not require major rescheduling of clinical activities, and offered “bite-sized” practical tips easy to implement in the workplace. |

| Gallagher, 2012 (ref. #34) | Descriptive | Develop and implement a peripatetic educational program for community preceptors to teach them the skills associated with the One-Minute Preceptor | Single institution (U. of Otago, New Zealand); sponsored by the Medical Education Unit | Not specified | 15-20 per workshop (total number not provided) | No |

Traveling workshops on One-Minute Preceptor, including a paired exercise; analysis of an actual one-to-one clinical teaching session in a DVD; and introduction to the 5 stages of clinical teaching using the One-Minute Preceptor. Funding source: Not reported |

No | No |

| Delver, 2014 (ref. #24) | Mixed-methods | Pilot study to evaluate the FM Preceptor Online Development (FM POD) program, designed to meet FD needs of rural preceptors | Single institution (U. of Calgary); sponsored by the Rural Integrated Community Clerkship Program, the Office of Distributed Learning and Rural Initiatives, and the Office of Faculty Development | 9 months | 14 preceptors for Rural Integrated Community Clerkship | Yes |

Distributed program, blending face-to-face, asynchronous, and synchronous teaching and learning techniques (online modules paired with podcasts followed by virtual workshops) Funding source: Not reported |

- Surveys (pre/post program and post-podcast) - Focused groups (post program) |

- Participants enjoyed collaborating with colleagues and rated their learning experiences highly - Participanst reported increased comfort with precepting teaching skills (p<.001) and distance learning technologies (p<.01) Needs assessment: giving effective feedback, time-efficient teaching strategies, working with learners in difficulty, teaching communication, physical exam and procedural skills were the highest rating topics (in descending order) |

| Tai, 2015 (ref. #32) | Mixed methods | Provide accessible training in education to community and rural preceptors | Monash University, Australia | Not specified | 978 participants (physicians, nursing, social work, PT/OT, speech pathology) for face-to-face workshops; 1728 total registrations for online modules | Yes |

Clinical Supervision Support Across Contexts (ClinSSAC): a 4- hour introductory module; developed by facilitators from medicine, physiotherapy, nursing and audiology. Initially as a face-to-face workshop, online modules Funding sources: Australian state and national government |

Surveys (post-intervention), interview and focus group with participants, faculty, managers and administrators | Participants rated workshops helpful or very helpful |

| Bernstein, 2018 (ref. #28) | Pre/posttest | Use newer technology to satisfy community-based preceptors’ desire for continued medical education and to improve their teaching practices | 3 US med schools (UNC, Kaiser Permanente-East Bay,UCSF, FAU) | 10 weeks | 88 community preceptors teaching in LICs | Yes |

Series of five brief podcasts on teaching skills directed towards community-based teachers in LICs; sent via group text message before morning commute Funding source: Not reported |

Pre- and post-surveys assessed acceptability and effectiveness of podcasts 67 completed pre- and 33 (36%) post-intervention survey |

64% of respondents found podcasts moderately or very helpful; 70% perceived podcasts altered their teaching style; 70% would likely or highly likely listen to more podcasts; 55% would likely or highly likely recommend them to colleagues; 25% listened to all five podcasts 22% had never received FD and 42% rarely |

| Brink, 2020 (ref. #23) | Pre/posttest | Design a new preceptor improvement program and determine its effectiveness and acceptability for community preceptors | Single institution (U. of Minnesota); sponsored by the Department of FM and Community Health | On average 3 hours over 4 weeks (range 2 weeks to 3 months) | 23 community preceptors enrolled and 13 completed program | Yes |

Readings, short videos, handouts and posters, one-on-one sessions with a trained standardized medical student who visited the preceptor’s office before and after preceptor’s engagement with the educational materials Funding source: Not reported |

Pre/post intervention: evaluation of preceptor’s teaching through self-evaluation, student reporting, and overall rating of teaching effectiveness |

Self-assessment: preceptors reported improved teaching competency for all the items in the survey; for 57% of items, results were statistically significant (p<.05) Standardized student reported preceptors used more of eight desired teaching behaviors in the post-intervention than the pre-intervention encounter (p<.001) All participants were either satisfied or highly satisfied with the program and would recommend it to a colleague |

| Farrell, 2020 (ref. #33) | Posttest only | Promote community preceptor partnerships, introduce practical educational resources, and develop effective teaching strategies in the midst of providing patient care | Presented at 3 national pediatric conferences | Annually | 57 Pediatric community and university-based preceptors (community 87% in 2016; 73% in 2017; 63% in 2018) | Yes |

90-minute workshop on teaching strategies (participant identified challenges and discussed approaches in small-group breakout sessions) Funding source: Not reported |

Post-workshop surveys | Participants rated the workshop as highly effective and engaging, with the small-group breakout session rated most engaging |

CME, continuing medical education; EBM, evidence-based medicine; FD, faculty development; FM, family medicine; IM, internal medicine; LICs, Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships; Mass, Massachusetts; Med, medical; NC, North Carolina; Peds, pediatrics; U, university

RESULTS

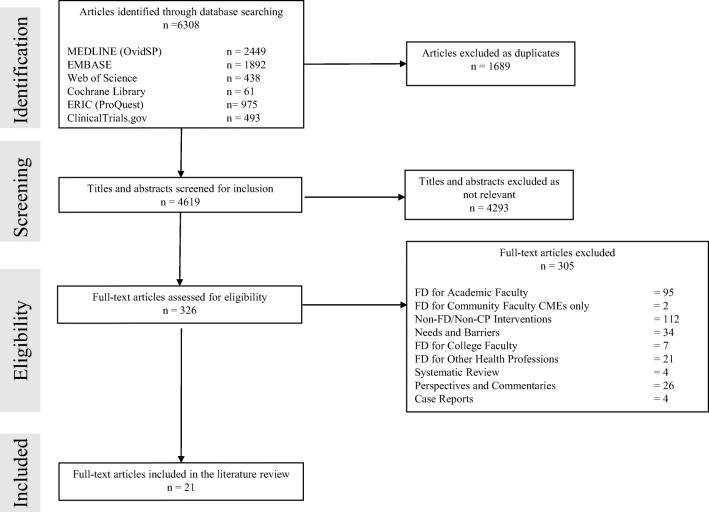

The search of the electronic databases resulted in a total of 6308 articles. We found 1689 duplicate articles and removed them. After reviewing the titles and abstracts of the remaining 4619 articles, we removed irrelevant articles (n = 4293) and identified 326 articles for full-text review. We selected 21 articles after the full-text review that we included in this study. Our search strategy is shown in Figure 1. An overview of our findings is included in Appendix 2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature search and study selection process from a review of the literature on faculty development programs for community preceptors.

Design of Faculty Development Programs

In most studies (67%, 14/21), a needs assessment guided the content and design of the FD program.20–33 Teaching skills was the main area community preceptors requested to have additional training. Thus, FD program developers designed their programs around this need and included topics such as teaching techniques (e.g., one-minute-preceptor),34 teaching in a longitudinal clerkship model,28 promoting a positive learning climate, communicating goals, providing feedback,30 and assessing clinical skills.20

Characteristics of Participants

The number of participants in the FD programs ranged from six to 1728 (e.g., total number of participants who registered for online modules, including community preceptors and other health professions; however, some participants registered for more than one module).32 One study did not provide the exact number of participants.34 Only one study provided the number of participants as a proportion of their preceptor pool.21 The majority of FD programs included only community preceptors (76%, 16/21); four programs included both academic and community-based preceptors;26, 30, 33, 35 and one study32 included health professionals from medicine, nursing, social work, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech pathology.

Characteristics of Faculty Development Programs

More than half of FD programs (62%, 13/21) were developed and implemented by the medical school that community preceptors were affiliated with. Among these programs, four were sponsored by Departments of Family Medicine,22, 23, 35, 36 one by the FD office,37 two by the Medical Education units,34, 38 one by the dean’s office,25 and one from the FD office and rural program24; four medical schools did not report sponsorship.20, 21, 26, 32 Three FD programs were sponsored by multiple institutions;27, 28, 31 one by a community-based residency program and a medical school;29 and one by a physician practice network.39 Some FD programs were supported by organizations, such as the American College of Physicians30 and Mountain Area Health Education Center in Ashville, North Carolina.40 Nine programs (9/21, 43%) reported funding information21, 25, 29, 30, 35–37, 39, 40 with federal and state grant funding35,40 and private foundations being the primary sources.25, 30, 37, 39 Three FD programs noted offering free registration.20, 35, 40 Five studies were international, including one study from Australia,32 two from Canada,20, 24 and two from the same institution in New Zealand.34, 38 The remaining studies were from various regions in the USA, including the Northeast, West, Midwest, and the South. The duration of the FD programs ranged from one weekend to 3 years; in five studies, duration was not included.29, 32, 34, 36, 37 In one study, the FD program was occurring annually as a 3-day retreat,20 and in another,33 at an annual national conference as a workshop.

Content of Faculty Development Programs

Workshops were common (62%, 13/21), including in-person (54%, 7/13) 20, 31, 33–35, 38, 41 and virtual offerings (8%, 1/13).36 In most studies, workshops were being supplemented by small group teaching,41 role-play,27 online modules,23, 24, 32 instructional videos,25 online discussion boards,22 or observed preceptor teaching encounters with learners.23, 29, 34, 37, 39 Willett26 used a short audiotape that community preceptors could listen to during their commute to work, while Delver et al.24 used podcasts to supplement face-to-face and online sessions. Bernstein et al.28 used a series of five podcasts that were sent via group text message before the morning commute. Armson et al.20 chose a retreat with a plenary and small group workshops to provide FD for rural preceptors; the workshops were divided into three “streams” (p. 532) based on the preceptors’ experience and needs (i.e., for novice, experienced teachers, and those interested in theoretical foundations of education).

Some FD programs used experienced preceptors to teach their peers. In the Doctoring for Community Preceptors,25 community preceptors were trained during the first year of the program as “opinion leaders” (p. 332), and subsequently led small groups during program implementation in the second year. In the study by Skeff et al.,41 a cadre of physician-facilitators who had received prior training at the Stanford Faculty Development Program in Clinical Teaching41 (p. 180) delivered a series of seven 2-h seminars in small groups with six to eight participants.

Some FD programs offered community preceptors hands-on opportunities to practice their teaching skills with trained standardized learners (e.g., medical students or residents) and receive feedback from FD faculty facilitators.23, 25, 29, 34, 37, 39 In some programs, these observations were recorded so community preceptors could watch after the encounter, reflect on their performance, and receive feedback from FD faculty.29 Brink et al.23 provided community preceptors with preparatory readings and short videos, and offered participants one-on-one sessions with a standardized medical student who visited their office before and after their review of the educational materials.

One FD program taught additional skills, such as evidence-based medicine, use of technology tools, doctor-patient communication, quality improvement, and advocacy.35 Baldwin et al.21 developed the Teaching and Learning Through Educational Technology (TeLeTET; p. 113) program that focused on teaching community preceptors basic educational technology skills, online learning, development of online curricula, and use of personal digital assistants in clinical practice. The Teaching the Culture of the Community program27 (p. 1221) focused on cultural competency training, including cultural needs assessment, patient-centered interviewing, feedback on cultural issues, and use of the community to enhance cultural understanding; this content was taught through modules, interactive lectures, and small group role-play exercises.

Evaluation and Outcomes of Faculty Development Programs

All but one study34 provided evaluation data. Participant survey was the primary modality of FD program evaluation (71%; 15/21). Surveys were most often distributed at the end of the program (60%, 9/15) and asked participants about their satisfaction and engagement with the various activities of the program (e.g., seminars, small groups); whether they would recommend it to a colleague; what they learned; and barriers in attending the program. However, the response rate varied among the studies (19 to 74%).30, 40 Participants self-reported improvement in their teaching skills, intrapersonal growth, increased self-confidence, ability to find mentors and network,35 more comfort with using distance learning technologies,24 and intentions to apply what they learned to their teaching encounters.27

A few FD programs used focus groups with FD faculty, participants, and/or medical students,24, 25, 32 observed structured teaching encounters,37 or medical student evaluations of community preceptors pre- and post-intervention23 for evaluation. Stone et al.37 asked trained standardized medical students to use an objective structured teaching exercise checklist to rate community preceptors’ teaching effectiveness. The authors reported a statistically significant (p = .03) difference in the ability of community preceptors to develop action plans post-intervention compared with pre-intervention. Moreover, community preceptors prioritized feedback and improved their communication skills with patients after attending the program, although the differences pre-/post-intervention were not statistically significant.37

Stuart et al.29 videotaped participants’ encounters with residents and used informal feedback from both participants and residents to evaluate the effectiveness of the FD program. Bing-You et al.39 used two visits of FD faculty to the community preceptor’s clinic and their observations of the community preceptors’ teaching encounters with students as a means to provide feedback to the participants. In addition, a month after the end of the FD program, the authors conducted phone interviews with the community preceptors to assess the impact of the intervention. Themes that emerged included program promoted reflection; offered new approaches to teaching; and supported collegiality and quality assurance.39

DISCUSSION

Our narrative review of the literature on FD programs for community preceptors identified that medical schools are the primary developers of such interventions as they recognize the need to prepare community teaching physicians for their demanding roles as educators. Family Medicine departments were the primary sponsors of these programs.22, 23, 29, 31, 35, 36 Fewer programs were sponsored by the FD office or medical education unit at the medical school. Accreditation requirements for comparability of student learning experiences across training sites11 and the increased need for clinical training at community settings1,7 are likely drivers of these FD programs. Funding of these programs was often through federal, state, and private foundations which may question the sustainability of these interventions.21,25, 30, 35, 36, 39, 40 Some programs in our study were implemented at a large scale and were supported by various organizations, such as the American College of Physicians30 and the Mountain Area Health Education Center in North Carolina.40 Few programs were international (e.g., Canada,20, 24 Australia,32 and New Zealand)34, 38 which highlights the important role these teaching physicians have in the educational mission of medical schools across the globe.

Most FD programs in our review conducted needs assessments to identity content areas important to community preceptors. Teaching skills were uniformly identified as the area community preceptors asked for more training. Our findings align with other literature that suggested community preceptors volunteer because they enjoy teaching, but often lack comfort, training, or experience in teaching, assessing students, or giving feedback.8, 14, 15, 42 Therefore, teaching skills were the primary focus of FD programs in our review, including teaching techniques,34 promoting a positive learning climate, setting expectations, communicating goals, providing feedback,30 and assessing clinical skills.20 Some programs35 incorporated topics such as evidence-based medicine, doctor-patient communication, and basic educational technology skills21 to better meet the needs of a student population who is increasingly more technology savvy.43 Moreover, technology can be used in various ways to supplement FD planning and delivery. Yilmaz et al.44 suggested using “nudge-based learning” (p. 1793) by providing content in small amounts via internet-connected devices and harnessing faculty performance analytics to identify faculty learning needs. Furthermore, incorporating virtual communities of practice into FD of community preceptors may offer opportunities to community teaching physicians who are geographically dispersed to connect with other community and academic teaching physicians.45 The FD programs in our review were implemented before the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., in or prior 2020). Since several of these programs utilized online and other teaching strategies (modules, podcasts, etc.), it is possible that some programs may have been able to quickly adapt and continue during the pandemic. Further studies should explore the impact of the pandemic on FD for community preceptors.

Our study identified a broad range of FD programs with regard to duration, setting, content, and instructional methods. Duration ranged considerably from one weekend to 3 years. Delivering an in-person workshop on a weekend would offer convenience to busy teaching clinicians, but may be inadequate if not supplemented with other modalities (e.g., online materials, mentoring). Khan et al.46 reported increased participant knowledge and understanding after attending a 2-day FD workshop, but attendees did not feel confident implementing what they learned and asked for additional resources and follow-up workshops.

In our review, the program developers were mindful of the competing responsibilities and time constraints of community preceptors that may pose a risk for emotional exhaustion and contribute to burnout and attrition.14, 47, 48 To address convenience and time constraints, program developers 26 used audiotapes or conducted site visits to the community preceptors’ offices.39 Site visits offer convenience and customizable FD, but require resources, institutional support, and trained FD faculty to be effective and sustainable. Other programs utilized a combination of instructional modalities (online and in-person) to better meet community preceptors’ needs. Some programs provided opportunities for community preceptors to reflect on their performance and receive feedback.37 Personalized FD interventions may be effective for community preceptors, but more data are needed to better understand the short- and long-term impact of these FD programs on teaching effectiveness and student learning. Additionally, online instructional modalities or sporadic workshops may offer convenience, but it is uncertain whether they can cultivate the social learning environment and continuity of engagement with other novice and expert preceptors that are necessary for the induction of community preceptors into the medical educator CoP.16 Future research should focus on better understanding how community preceptors develop their professional identity as educators.

Five programs in our review offered CME credits as an incentive for engagement.21, 22, 25, 31, 40 Our findings align with literature that indicates CMEs and maintenance of certification credits to be among the incentives medical schools use to recruit and retain community preceptors in addition to teaching awards, library access, financial stipends, and annual appreciation events. However, the value49 and effect of these incentives on the “community preceptors crisis”8 (e.g., challenges in their recruitment and retention; p. 329) need to be further studied.

Faculty development programs in our study primarily relied on surveys to evaluate efficacy. Participants typically completed surveys at the end of the program or before and after the completion of the program.24, 28, 30 The surveys collected information about participants’ satisfaction with the content and delivery of the program (Kirkpatrick Level 1) and self-perceived changes in participants’ knowledge, skills, and confidence (Kirkpatrick Levels 2a and 2b).50 Community preceptors reported being overall satisfied with the FD program, improving their teaching skills, finding mentors, becoming more confident as medical educators, and being willing to implement what they learned. These results align with outcomes of FD programs for academic clinician educators that showed high self-reported satisfaction with FD interventions, but limited data on the longitudinal impact of such programs on participants’ teaching skills, identity formation as medical educators, their workplace communities and learners, and the medical school.51

A few programs in our review conducted focus groups24, 25, 32 or used medical student evaluations23 (Kirkpatrick Level 4b)50 to assess their effectiveness. O’Sullivan and Irby52 suggest that evaluators of FD programs should consider the continuous interactions between FD and the workplace communities to better assess their impact and effectiveness. In our review, only one study20 offered different FD tracks based on community preceptors’ interests and expertise. Moreover, topics such as diversity, bias training, and cultural competence were not included in the programs we reviewed, with the exception of the study by Ferguson et al.27 that focused on cultural competence. Faculty development planners and medical schools should consider contextual factors at the community level, important and timely topics in medical education, and community preceptors’ experiences and needs in the design and evaluation of their programs.

Our study had limitations. Our narrative review of the literature focused on community preceptors and our findings may not be generalizable to academic teaching faculty. Our review included studies published in 2020 or prior (e.g., pre-COVID-19 pandemic) which may limit the applicability of our findings to the post-pandemic period. We did not access the methodological quality of the studies in our review, and only included English language publications. Nevertheless, we followed a narrative review approach18 and standard methods to avoid bias, such as having two independent reviewers (IA and JS) for each review stage.

CONCLUSION

Faculty development for community preceptors is important for medical schools to ensure these medical educators are well prepared to provide medical students with high-quality learning experiences. Workshops and online materials are the primary modality for FD delivery, although direct observations of community preceptors’ teaching with feedback from FD faculty and learners may be more helpful for training and development of interpersonal skills. Future studies need to focus on the long-term impact of FD on community preceptors’ teaching skills, the formation of their identity as medical educators, and student learning.

Supplementary Information

Search Strategies for a Narrative Review of the Literature on Faculty Development Programs for Community Preceptors (PDF 184 kb)

Study Findings Overview (PDF 136 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Robyn E. Rosasco, MSLIS, AHIP, head of research services at Charlotte Edwards Maguire Medical Library, Florida State University College of Medicine, for her assistance in the literature review.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

None.

Footnotes

Previous Presentations:

None

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.AAMC. Curriculum reports. Regional Campuses at Medical School Programs. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/interactive-data/regional-campuses-medical-school-programs. Accessed 18 May 2022.

- 2.AAMC. Medical school applicants and enrollments hit record highs; underrepresented minorities lead the surge. Association of American Medical Colleges 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/medical-school-applicants-and-enrollments-hit-record-highs-underrepresented-minorities-lead-surge. Accessed 22 May 2022.

- 3.Farnsworth TJ, Frantz AC, McCune RW. Community-based distributive medical education: advantaging society. Med Educ Online. 2012;17:8432. 10.3402/meo.v17i0.8432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Claramita M, Setiawati EP, Kristina TN, Emilia O, van der Vleuten C. Community-based educational design for undergraduate medical education: a grounded theory study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):258. 10.1186/s12909-019-1643-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.de Villiers M, van Schalkwyk S, Blitz J, et al. Decentralised training for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):196. 10.1186/s12909-017-1050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Crampton PE, McLachlan JC, Illing JC. A systematic literature review of undergraduate clinical placements in underserved areas. Med Educ. 2013;47(10):969-78. 10.1111/medu.12215. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.ACICBL. Enhancing Community-Based Clinical Training Sites: Challenges and Opportunities; 16th Annual Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Congress. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/community-based-linkages/reports/ sixteenth-2018.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2022.

- 8.Christner JG, Dallaghan GB, Briscoe G, et al. The community preceptor crisis: recruiting and retaining community-based faculty to teach medical students-a shared perspective from the alliance for clinical education. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(3):329-36. 10.1080/10401334.2016.1152899. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Fogarty JJ. Optimal alcohol taxes for Australia. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2012;15(2). 10.1515/1558-9544.1276. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Fazio SB, Shaheen AW, Amin AN. Tackling the problem of ambulatory faculty recruitment in undergraduate medical education: an AAIM Position Paper. Am J Med. 2019;132(10):1242-1246. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.LCME. LCME Accreditation Guidelines for New and Developing Medical Schools; LCME 8.7 Comparability of Education/ Assessment. Retrieved from http://lcme.org/. Accessed 22 May 2022.

- 12.Hatem CJ, Searle NS, Gunderman R, et al. The educational attributes and responsibilities of effective medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):474-80. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820cb28a. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Drowos J, Baker S, Harrison SL, Minor S, Chessman AW, Baker D. Faculty development for medical school community-based faculty: a council of academic family medicine educational research alliance study exploring institutional requirements and challenges. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1175-1180. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001626. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Beck Dallaghan GL, Alerte AM, Ryan MS, et al. Recruiting and retaining community-based preceptors: a multicenter qualitative action study of pediatric preceptors. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1168-1174. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001667. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Minor S, Huffman M, Lewis PR, Kost A, Prunuske J. Community preceptor perspectives on recruitment and retention: the CoPPRR Study. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):389-398. 10.22454/FamMed.2019.937544. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lave J WE. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- 18.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1(1):b92.

- 19.Chandler J, Churchill R, Higgins J, Lasserson T, Tovey D. Methodological standards for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Sl: Cochrane Collaboration. 2014;3(2):1-4.

- 20.Armson H, Crutcher R, Myhre D. Cabin fever: an innovation in faculty development for rural preceptors. Med Educ. 2005;39(5):531–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldwin CD, Niebuhr VN, Sullivan B. Meeting the computer technology needs of community faculty: building new models for faculty development. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4(1 Suppl):113-6. 10.1367/1539-4409(2004)004<0113:mtctno>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Bramson R, Vanlandingham A, Heads A, Paulman P, Mygdal W. Reaching and teaching preceptors: limited success from a multifaceted faculty development program. Fam Med. 2007;39(6):386-8. [PubMed]

- 23.Brink D, Power D, Leppink E. Results of a preceptor improvement project. Fam Med. 2020;52(9):647-652. 10.22454/FamMed.2020.675133. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Delver H, Jackson W, Lee S, Palacios M. FM POD: an evidence-based blended teaching skills program for rural preceptors. Fam Med. 2014;46(5):369-77. [PubMed]

- 25.Wilkes MS, Hoffman JR, Usatine R, Baillie S. An innovative program to augment community preceptors’ practice and teaching skills. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):332-41. 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Willett LR. Brief report: utilizing an audiotape for outpatient preceptor faculty development. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):503-5. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Ferguson WJ, Keller DM, Haley HL, Quirk M. Developing culturally competent community faculty: a model program. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1221-8. 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Bernstein J, Mazotti L, Ziv TA, et al. Texting brief podcasts to deliver faculty development to community-based preceptors in longitudinal integrated clerkships. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10755. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Stuart MR, Orzano AJ, Eidus R. Preceptor development in residency training through a faculty facilitator. J Fam Pract. 1980;11(4):591-5. [PubMed]

- 30.Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Bergen MR, Sampson K, Deutsch SL. Regional teaching improvement programs for community-based teachers. Am J Med. 1999;106(1):76-80. 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00360-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hitchcock MA, Ramsey CN, Jr., Herring M. A model for developing clinical teaching skills of family practice teachers. J Fam Pract. 1980;11(6):923-9. [PubMed]

- 32.Tai J, Bearman M, Edouard V, Kent F, Nestel D, Molloy E. Clinical supervision training across contexts. Clin Teach. 2016;13(4):262-6. 10.1111/tct.12432. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Farrell L, DeWolfe C, Cuzzi S, Ismail L, Newman D, Kalburgi S. Strategies for teaching medical students: a Faculty Development Workshop for Pediatric Preceptors in the Community Setting. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10890. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Gallagher P, Tweed M, Hanna S, Winter H, Hoare K. Developing the one-minute preceptor. Clin Teach. 2012;9(6):358-62. 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Gjerde CL, Hla KM, Kokotailo PK, Anderson B. Long-term outcomes of a primary care faculty development program at the University of Wisconsin. Fam Med. 2008;40(8):579-84. [PubMed]

- 36.Levy BT, Albrecht L, Gjerde CL. Using videoconferencing to train community family medicine preceptors. Acad Med. 1998;73(5):616-7. 10.1097/00001888-199805000-00094. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Stone S, Mazor K, Devaney-O’Neil S, et al. Development and implementation of an Objective Structured Teaching Exercise (OSTE) to evaluate improvement in feedback skills following a faculty development workshop. Teach Learn Med. Winter 2003;15(1):7-13. 10.1207/S15328015TLM1501_03. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Gallagher P, Pullon S. Travelling educational workshops for clinical teachers: are they worthwhile? Clin Teach. 2011;8(1):52-6. 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Bing-You RG, Renfrew RA, Hampton SH. Faculty development of community-based preceptors through a collegial site-visit program. Teach Learn Med. 1999;11(2):100-104. 10.1207/S15328015TL110208.

- 40.Langlois JP, Thach SB. Bringing faculty development to community-based preceptors. Acad Med. 2003;78(2):150-5. 10.1097/00001888-200302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Bergen MR, et al. The Stanford Faculty Development Program: a dissemination approach to faculty development for medical teachers. Teach Learn Med. 1992;4(3):180-187. 10.1080/10401339209539559.

- 42.Graziano SC, McKenzie ML, Abbott JF, et al. Barriers and strategies to engaging our community-based preceptors. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(4):444-450. 10.1080/10401334.2018.1444994. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Reilly JR, Vandenhouten C, Gallagher-Lepak S, Ralston-Berg P. Faculty development for e-learning: a multi-campus community of practice (COP) approach. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2012;16(2):99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yilmaz Y, Lal S, Tong XC, et al. Technology-enhanced faculty development: future trends and possibilities for health sciences education. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(4):1787-1796. 10.1007/s40670-020-01100-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Ghamrawi N. Teachers’ virtual communities of practice: a strong response in times of crisis or just another fad? Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2022:1-27. 10.1007/s10639-021-10857-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Khan AM, Gupta P, Singh N, Dhaliwal U, Singh S. Evaluation of a faculty development workshop aimed at development and implementation of a competency-based curriculum for medical undergraduates. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(5):2226-2231. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_17_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Castiglioni A, Aagaard E, Spencer A, et al. Succeeding as a clinician educator: useful tips and resources. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(1):136-40. 10.1007/s11606-012-2156-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516-529. 10.1111/joim.12752. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Ryan MS, Leggio LE, Peltier CB, et al. Recruitment and retention of community preceptors. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3) 10.1542/peds.2018-0673. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick KJ.Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels. (3rd. ed.). Berrett-Koehler; 2006.

- 51.Alexandraki I, Rosasco RE, Mooradian AD. An evaluation of faculty development programs for clinician-educators: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2021;96(4):599-606. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003813. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Reframing research on faculty development. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):421-8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820dc058. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search Strategies for a Narrative Review of the Literature on Faculty Development Programs for Community Preceptors (PDF 184 kb)

Study Findings Overview (PDF 136 kb)