Abstract

Improper healing of a femoral shaft fracture can result in posttraumatic residual multiplanar femoral deformity and limb shortening, which can be restored with a corrective osteotomy. Predominantly in complex posttraumatic circumstances, the use of computer assistance in orthopaedic surgery may facilitate meticulous preoperative planning, and further improve the accuracy and safety of such procedures, potentially resulting in better clinical outcomes. Herein, we present a unique case of electromagnetic navigation assisted patient-personalized femoral osteotomy for acute correction of posttraumatic residual multiplanar femoral deformity with shortening.

Keywords: Navigation, Patient-specific, Femoral osteotomy, Femoral deformity, Femoral shortening

Introduction

Femoral shaft fractures are relatively common injuries to the lower limb [1–3]. These injuries are commonly associated with a high-energy impact, which often leads to multifragmentary fracture patterns, whereby the length and rotation of the affected femur may not be easily restored with fixation [3]. As a result, limb malalignment in terms of rotation and angulation can occur, along with leg-length discrepancy (LLD), which can significantly impair a patient’s quality of life [1–5].

An ever-advancing development of computer-aided surgical assistance, such as electromagnetic navigation (EMN) or custom, patient-specific, 3D printed cutting guides, provides many possibilities to an orthopedic surgeon, from preoperative planning to intraoperative assistance in technically demanding surgical procedures, leading to improved safety, accuracy, and overall execution of the procedure itself, predominantly in complex posttraumatic circumstances [2, 5].

Herein, we present a unique case of EMN-assisted patient-personalized femoral osteotomy for acute correction of posttraumatic residual multiplanar femoral deformity with shortening.

Case Description

A 57-year-old female with arterial hypertension, multiple sclerosis, and posttraumatic residual multiplanar femoral deformity with limb shortening was referred to our institution for further surgical treatment. Six years prior she suffered a left-side femoral shaft fracture, primarily treated with plate fixation in an outside facility. Since the primary injury management, the patient had been walking with a support and limping due to the LLD and symptomatic hyperextension of the left knee, with intense pain in her left thigh while walking. She had no known allergies, rheumatic diseases, or history of other skeletal injuries or surgeries. She denied any infection, fever, or antibiotic treatment in recent times. In the initial examination, a LLD of 27 mm was measured. There was no local signs of infection present in the area of the postoperative scar on her left thigh, despite the local palpatory pain. Spasticity of the patient’s both lower limbs was noted, along with partially diminished muscular strength of the left lower limb (compared to the contralateral limb), and reported hypoesthesia over the entire left lower limb. The range of motion (ROM) of the left knee was 120° of flexion, and 15° of hyperextension. The ROM of the left hip was normal. The imaging studies of the left femur showed a malunion with significant varus, hyperextension, and torsional deformity (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Both left hip and knee joints were without significant osteoarthritis or intraarticular abnormalities.

Fig. 1.

Images of posttraumatic residual multiplanar femoral deformity with shortening after left-side femoral shaft fracture, primarily treated with plate fixation in an outside facility. Anteroposterior view (left) and lateral view (right)

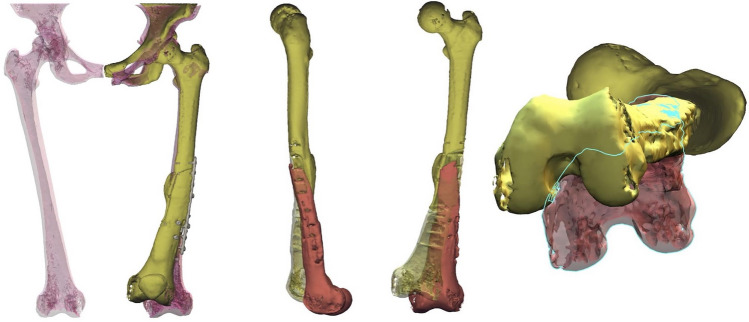

Fig. 2.

Schematic 3D representation of posttraumatic residual multiplanar femoral deformity with shortening after left-side femoral shaft fracture, primarily treated with plate fixation in an outside facility (left) and the patient-personalized, 3D-based, virtual preoperative surgery planning of the osteotomy cuts (middle and right)

Fig. 3.

Schematic 3D representation of the patient-personalized, 3D-based, virtual preoperative surgery planning, osteotomy cuts and final osteotomy position after mobilization, according to the anatomy of patients’ contralateral femur

A detailed explanation of diagnostic findings and possible treatment options was given to the patient. Based on clinical examination and imaging, we opted for a patient-personalized (Fig. 2), EMN-assisted (Guiding Star, Ekliptik d.o.o., Ljubljana, Slovenia), oblique-plane osteotomy for the correction of sagittal and coronal plane deformity and closing wedge osteotomy for the correction of rotational deformity with plate and screws fixation, using 3D-based, patient-personalized virtual preoperative surgery planning in EBS medical software (Ekliptik d.o.o., Ljubljana, Slovenia). The EMN system used in this case works on the principle of surface-based registration [5]. The planning of surgery was performed via upload of a DICOM format file of preoperative CT scans of both femurs into the EBS medical software, in order to generate a virtual 3D model of the left femur (Fig. 3). With the help of a software specialist, the surgeon planned the osteotomy cuts (Fig. 2), desired amount of correction, elongation, and the final positon of the fragments, according to the anatomy of patients’ contralateral femur (Fig. 3). The EMN-assisted patient-personalized femoral osteotomy for acute correction of posttraumatic residual multiplanar femoral deformity with shortening was developed based on the step-cut osteotomy concept for acute femoral lengthening in adults described by Brumat et al. [4]. The procedure was performed by the senior author (R.T.). The patient was placed in a supine position. The leg to be operated on was fixed proximally by a post in the perineal region and the ipsilateral foot was secured in the boot of the traction table. The well-leg was secured in extension. The lateral femoral approach was developed along the previous postoperative scar, followed by elevation of the quadriceps muscle and subperiostal preparation of the femur. Residual osteosynthetic material was removed. The first EMN reference sensor was then placed onto the distal and the second onto the proximal part of the exposed femur (both external to the planned osteotomy), with subsequent acquisition of several reference points on the given femoral surface [5]. All the digitized surface points were then adjusted to the previously rendered 3D model of the femur, which allowed for the intraoperative real-time visualization of the planned position of the personalized osteotomy cuts, before executing the EMN-assisted osteotomy [5]. After verification of the planned and desired correction via EMN, we marked the osteotomy length and cuts (Fig. 2) with K-wires. The oblique-plane osteotomy for the correction of sagittal and coronal plane deformity and closing wedge osteotomy for the correction of rotational deformity were performed with oscillating and reciprocating saw, followed by controlled gradual lengthening of the femur under traction [4]. The lengthening was limited to 12 mm, due to the high soft tissue tension and scarring. While still under traction, the osteotomized distal femoral fragment was then placed to the most optimal position according to the matching of preoperative planning and intraoperative navigation data. The fragments were then fixated with compression screws, followed by the release of the traction, and stabilisation of the construct with a LC-DCP plate with a combination of locking and non-locking screws. The osteotomy gaps were not grafted. The final intraoperative assessment showed an optimal position of the deformity correction and the construct, both in virtual and the real-life setting. Pathohistological examination excluded infection.

The postoperative course was unremarkable. We followed the same postoperative regimen, as described by the step-cut osteotomy method by Brumat et al. [4]. Based on the final follow-up 36 months after surgery and according to regular follow-up examinations and imaging, the osteotomy healed properly, achieving radiological evidence of bone union after 4 months, and with an optimal position of the corrected fragments, despite residual LLD of 15 mm (Figs. 4 and 5). The ROM of left-side hip and knee was normal, and the patient ambulated without support and pain.

Fig. 4.

Follow-up imaging: 1 month after the surgery (left) and 4 months after the surgery (right)

Fig. 5.

Long-leg radiographs: preoperative (left), 4 months after the surgery (middle), and 36 months after the surgery (right)

Discussion

The presence of femoral deformity or malalignment can affect postural balance, gait patterns and biomechanics of joints, adjacent to the deformity, causing discomfort and pain while walking, acute damage to the joint and acceleration of degenerative changes in the joints, whereby a femoral malalignment is considered as a significant risk factor for the development of low back pain, degenerative spinal changes, stress fractures, and hip or knee osteoarthritis [2–4]. The posttraumatic residual femur deformity in the presented case was multiplanar (sagittal, frontal and horizontal plane), with concomitant symptomatic structural LLD (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Such circumstances may be challenging, because combined deformities increase the complexity of the surgery and therefore may increase the chances of complications incurred by the subsequent deformity correction surgery [3]. Thus, predominantly in complex posttraumatic circumstances, the use of computer assistance in orthopaedic surgery may facilitate meticulous preoperative planning, and improve the accuracy and safety of these procedures, potentially resulting in better clinical outcomes [2, 5]. The successful treatment in this reported case emphasizes the benefits of computer assistance in orthopedic surgery, as increasingly recognized in recent years [2, 5]. Not only that the intraoperative use of navigation systems with real-time visualization improves the accuracy of bone cuts and overall safety of the surgical procedure, it also reduces the need for an intraoperative fluoroscopy, which reduces exposure to the radiation [2, 5]. Furthermore, patient-personalized preoperative planning via reconstruction models also enables 3D-printing of patient-specific templates, which can be used as osteotomy and implant positioning guides during the procedure [2, 5], although this concept was not considered in this reported case.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Uroš Vovk, PhD for his assistance with the preparation of Figs 2 and 3, and Mojca Tomažič, MD for her assistance with the preparation of Fig. 5.

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by all the authors. An initial draft of the manuscript was written by D.E., R.T. and P.B. redrafted the manuscript parts and provided helpful advice on the final revision. All authors were involved writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent

The patient provided written informed consent for her participation in the study and for their anonymized data to be published in this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Danijel Erdani, Email: danijel.erdani@ob-valdoltra.si.

Rihard Trebše, Email: rihard.trebse@ob-valdoltra.si.

Peter Brumat, Email: peter.brumat@ob-valdoltra.si.

References

- 1.Santoro D, Tantavisut S, Aloj D, Karam MD. Diaphyseal osteotomy after post-traumatic malalignment. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2014;7(4):312–322. doi: 10.1007/s12178-014-9244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oraa J, Beitia M, Fiz N, González S, Sánchez X, Delgado D, et al. Custom 3D-printed cutting guides for femoral osteotomy in rotational malalignment due to diaphyseal fractures: surgical technique and case series. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021;10(15):3366. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Middleton S, Walker RW, Norton M. Decortication and osteotomy for the correction of multiplanar deformity in the treatment of malunion in adult diaphyseal femoral deformity: a case series and technique description. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology. 2018;28(1):117–120. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-2008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brumat P, Mihalič R, Kovač S, Trebše R. Acute femoral lengthening in adults using step-cut osteotomy, traction table, and proximal femoral locking plate fixation: surgical technique and report of three cases Indian. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2022;56(4):559–565. doi: 10.1007/s43465-021-00547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brumat P, Mihalič R, Benulič Č, Kristan A, Trebše R. Patient-specific template and electromagnetic navigation assisted bilateral periacetabular osteotomy for staged correction of bilateral injury-induced hip dysplasia: a case report. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2021;8(2):192–196. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.