Abstract

In recent decades, environmental pollution with chromium (Cr) has gained significant attention. Although chromium (Cr) can exist in a variety of different oxidation states and is a polyvalent element, only trivalent chromium [Cr(III)] and hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] are found frequently in the natural environment. In the current review, we summarize the biogeochemical procedures that regulate Cr(VI) mobilization, accumulation, bioavailability, toxicity in soils, and probable risks to ecosystem are also highlighted. Plants growing in Cr(VI)-contaminated soils show reduced growth and development with lower agricultural production and quality. Furthermore, Cr(VI) exposure causes oxidative stress due to the production of free radicals which modifies plant morpho-physiological and biochemical processes at tissue and cellular levels. However, plants may develop extensive cellular and physiological defensive mechanisms in response to Cr(VI) toxicity to ensure their survival. To cope with Cr(VI) toxicity, plants either avoid absorbing Cr(VI) from the soil or turn on the detoxifying mechanism, which involves producing antioxidants (both enzymatic and non-enzymatic) for scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Moreover, this review also highlights recent knowledge of remediation approaches i.e., bioremediation/phytoremediation, or remediation by using microbes exogenous use of organic amendments (biochar, manure, and compost), and nano-remediation supplements, which significantly remediate Cr(VI)-contaminated soil/water and lessen possible health and environmental challenges. Future research needs and knowledge gaps are also covered. The review’s observations should aid in the development of creative and useful methods for limiting Cr(VI) bioavailability, toxicity and sustainably managing Cr(VI)-polluted soils/water, by clear understanding of mechanistic basis of Cr(VI) toxicity, signaling pathways, and tolerance mechanisms; hence reducing its hazards to the environment.

Keywords: chromium phytotoxicity, environment, contamination, plant physiology and growth, remediation

1. Introduction

Heavy metal contamination has disastrous impacts on terrestrial as well as aquatic life (Pushkar et al., 2021), and it has significantly disrupted the natural ecosystem (Zulfiqar et al., 2022). The unplanned urban and industrial development that disregards the value of a healthy environment is the main cause of environmental pollution (Dabir et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2022a). These actions have greatly increased the pollution from heavy metals, which upsets the natural balance (Posthuma et al., 2019; Qianqian et al., 2022). More than 1.7 million deaths were reported by World Health Organization (WHO) because of exposure to harmful contaminants, such as heavy metals (World Health Organization (WHO), 2017; Xu et al., 2018). The increase of heavy metal pollution in the environment increases the potential of human exposure to these heavy metals (Zulfiqar et al., 2019). Heavy metals may be harmful to living things due to their biodegradable properties (Qianqian et al., 2022). At different trophic levels, heavy metals frequently bioaccumulate and move within the ecosystem (Pushkar et al., 2021). Untreated trash can contain heavy metals that may leak into irrigation water/groundwater and easily absorbed by plants (Banerjee et al., 2019). Heavy metals can have fatal consequences on living things when they encounter them through water, air, food, etc. (Majumder et al., 2017; Yaashikaa et al., 2019). The degradation of heavy metals is a serious problem that requires immediate action.

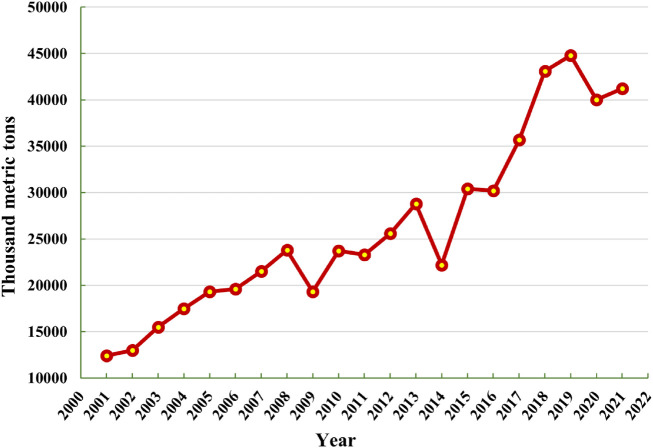

In the earth’s mantle, chromium (Cr) is 17th the most plenteous element, and the valence state of Cr regulates its toxicity in plants. Cr is widely used in a various industry, including the Cr plating, tanneries, mining, steel, and chemical industry (Shahid et al., 2017; Pushkar et al., 2021). Cr has become more prevalent as an environmental pollutant due to its increased industrial uses (Pradhan et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2022a). Cr is a pervasive contaminant with significant environmental hazards, particularly for soil-plant ecosystem (Ao et al., 2022; Kapoor et al., 2022). It is a metallic compound that belongs to category VI-B in the periodic table with an atomic number of 24. It is a shiny, hard, and steel-gray mineral with maximum melting point (Owlad et al., 2009). The annual world mine production of Cr in thousand metric tons is mentioned in Figure 1 . The trivalent and hexavalent Cr appears being the most persistent among the numerous chromium oxidation states (III to +VI) (Chug et al., 2016). Hexavalent Cr is known to be a dangerous metal relative to the trivalent form because of its carcinogenic, mutagenic, and oxidizing properties (Wei et al., 2022a). Compounds of Cr(VI) are thousand times more cytostatic and carcinogenic than Cr(III) (Mamais et al., 2016). Furthermore, as opposed to further forms, Cr(VI) is highly soluble and bioavailable, obtaining more consideration (Xiao W. et al., 2017). There is no known biological function of Cr in plants (Srivastava et al., 2021). The soil properties, such as soil texture, pH, organic matter (OM) composition, electrical conductivity (EC), sulphide ions, iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn) oxides, microbial activity, and soil moisture content, as well as the plant physiology, such as root surface area, rate of root exudation, rate of transpiration, and plant type all influence the biogeochemical behavior of Cr in soil-plant systems (Shahid et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2021; Ao et al., 2022). Plants lack specialized transporters and channels for absorbing Cr because it is a non-essential element for them (Adhikari et al., 2020). As a result, certain carriers of the necessary ions for plant metabolism, such as Fe for Cr(III) and phosphate and sulphate for Cr(VI), are used by plants to accumulate Cr (Anjum et al., 2016a). The oxidative stress caused due to Cr toxicity may lead to reduce membrane stability due to the over-accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that may also damage the morpho-physiological attributes in the plants (Eleftheriou et al., 2015; Azeez et al., 2021). Due to oxidative reactions such as mutilation of DNA and RNA, inhibition of enzymes, lipid peroxidation, and protein oxidation, ROS can induce cell death when produced in high concentrations (Srivastava et al., 2021). The functioning and regulation of many proteins are reportedly suppressed by Cr toxicity (Dotaniya et al., 2014; Handa et al., 2018a), and plant tissues exhibit chromosomal abnormalities as a result (Shahid et al., 2017). Numerous techniques, including solvent extraction, adsorption, chemical reduction, bio-remediation, and others, have been thoroughly investigated and evaluated, to remove hazardous form Cr(VI) to non-toxic Cr(III) form from polluted soil, water, and air (Azeez et al., 2021). Moreover, plants have evolved a variety of sophisticated adaptation methods, such as chelation by organic compounds followed by sequestration within vacuoles, to deal with high amounts of ROS produced under biotic and abiotic challenges (Azeez et al., 2021; Pushkar et al., 2021). To combat the elevated amounts of Cr-mediated ROS, plants also have a secondary mechanism for generating antioxidant enzymes (Srivastava et al., 2021; Ao et al., 2022). Understanding the biogeochemistry of Cr in soil-plant environments and the effects that high levels of Cr will have on the ecosystem is crucial.

Figure 1.

Annual world mine production of Cr in thousand metric tons (source, U.S.G.S. (United States Geological Survey), 2021).

The effects of Cr toxicity on agricultural productivity, lipid peroxidation, ROS production, and potential remediation procedures have been described in a number of previous research (Shanker et al., 2005; Shahid et al., 2017; Azeez et al., 2021; Srivastava et al., 2021; Ao et al., 2022). This review provides an overview of the most recent research on the mechanisms underlying transport of Cr, accumulation, toxicity, and detoxification in soil-plant systems. The toxic effects of Cr on key metabolic functions of plants leading to growth and yield impairment are reported. The mechanisms of Cr(VI) immobilization and reduction by organic amendments i.e., biochar, compost, and organic manure are also discussed Cr(VI). Additionally, in this review the recent remediation techniques are also highlighted, such as bioremediation, which includes phytoremediation, remediation using microbes, and supplements for nano-remediation. These techniques significantly reclaim Cr-contaminated soil and water while reducing potential health and environmental risks. To define future research goals and needs, research gaps in the biogeochemical behavior of Cr in soil-plant systems and difficulties in using in-situ remediation materials for Cr(VI)-contaminated soils are also integrated.

2. Chemical properties of chromium

The element Cr is relatively active. Instead of reacting with water, it reacts with many acids. At room temperature, it reacts with oxygen to create chromium oxide (Cr2O3). A thin layer of chromium oxide coats the metal’s surface, preventing further corrosion (rusting). The atomic number of Cr is 24 and has 51.996 g mol-1 molecular weight. Moreover, the electronegativity of Cr is 1.6, density 7.19 g cm-3 at 20°C, ionic radius 0.061 nm for Cr(III) and 0.044nm for Cr(VI), melting point 1907°C and boiling point is 2672°C. Cr is hard, brittle, and lustrous. It can be highly polished and is a silver-gray color.

3. Sources of chromium in environment

Cr is one of the heavy metals whose concentration is continuously rising because of industrial expansion and combustion processes, particularly the rise of the metal, chemical, and tanning sectors (Sharma et al., 2020). Industrial processes like leather tanning, Cr plating, pigment production, wood preservation, and the use of Cr as a corrosion-inhibitor in cooling towers are examples of anthropogenic sources (Shanker et al., 2005). Natural sources include the leaching of Cr during weathering of ultramafic rocks is another (Ao et al., 2022). Other environmental sources of Cr include power plants using liquid fuels, brown, and hard coal, industrial and municipal trash, and rocks eroded by water and air (Shahid et al., 2017). Cr pollution is not a concern on a global basis, but it may cause excessive concentrations of this pollutant to circulate in the biogeochemical cycle locally due to metal permeability into soil, water, or the atmosphere (Yang et al., 2022).

4. Chromium dynamics in soil

The average soil concentration of Cr is about 40 mg kg-1 (Isak et al., 2013). Cr exhibits a wide range of potential states of oxidation, the +3 state is vigorously persistent; the +3 and +6 forms are frequently seen in Cr groups, while the +1, +4, and +5 states are uncommon. Cr FeCr2O4 chromate, which contains about 70% of pure Cr2O3, is the main mineral possessing this element (Lakshmi and Sundaramoorthy, 2010). Natural Cr exists in most soils as relatively inert forms of Cr(III) that must be liberated over time by acid discharge (Chandra et al., 2010). The manganese (Mn) oxides present in soils will oxidize Cr(III) into Cr(VI), but a minute proportion of Cr(III) in soils is typically found in oxidizable forms (Mishra et al., 2009). Within the soil, Cr is perfectly integrated, however effectively bound to organic materials on Fe and Mn oxides and hydroxides (Balamurugan et al., 2014).

5. Factors affecting chromium dynamics

The disruption of the equilibrium state between species is significantly impacted by several chemical events that Cr conversion can cause in soils, including hydrolysis, oxidation, precipitation, and reduction (Di-Palma et al., 2015). Shift of redox state (Eh), soil pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), biological conditions, microbial environments, and competitive cations have a significant impact on these complex interactions (Taghipour and Jalali, 2016). Cr speciation is particularly vulnerable to the values of soil Eh (Xiao et al., 2019). The dominant factor influencing soil Eh may be biochemical properties of metals, specifically those with different types of metal oxidation conditions in the soil (Bell et al., 2022). In addition to Cr(III) immobilization and precipitation, altered soil types cause hazardous Cr(VI) to be converted to less harmful Cr(III) (Pakade et al., 2019). Generally, in oxygen-rich conditions, Cr(VI) species dominate and exists as HCrO4 -, Cr2O7 2- and CrO4 2-; these have higher bioavailability, solubility and propensity for transport (Ball and Izbicki, 2004; Larsen et al., 2016), in an acidic environment, Cr(VI) does have significant Eh (1.38 V), indicating its significant oxidizing propensity (Shadreck, 2013). By influencing its chemical speciation, soil pH significantly influences Cr geochemical activity (Amin and Kassem, 2012). Soil pH determines the chemical form of Cr in soil solution and controls the balance between solubility, adsorption and desorption of Cr in soil (Ertani et al., 2017). A decrease in soil pH causes the mobilization and release of Cr(III), while an increase in soil pH leads to formation of Cr(VI) in soil (Dias-Ferreira et al., 2015). Only at pH 5.5, Cr(III) have quite a poor stability (Kabata-Pendias, 2010). Cr(III) almost fully precipitates above the pH, and thus its compounds are known to be extremely stable in soil. In contrast, Cr(VI) is highly volatile in soil, and is present in acidic and alkaline pH environments (Kabata-Pendias, 2010). Apart from directly affecting the Cr speciation, pH also influences the chemical and mineralogical properties of soil such as CEC surface charge and Eh, thereby regulating the transport, solid phase fractionation and redox behavior of Cr (Xu et al., 2020). Soil Organic matter plays an important role in determination of Cr bioavailability in soil through oxidation/reduction and adsorption/desorption (Ao et al., 2022). It binds metals in soil and performs as a transporter of Cr and several other heavy metals, reflecting soil and deposits as metals and OM storage association (Eckbo et al., 2022). Soil OM controls the Cr bioavailability and speciation through three key mechanisms (adsorption, direct and indirect reduction) (Xia et al., 2019). (1) Soil OM has a higher CEC and can form simple organic molecules and humic substances with Cr ions in soil (Schaumann and Mouvenchery, 2018). (2) Dissolved organic carbon acts as an electron donor for the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) (Li et al., 2020). (3) Soil OM drives microbial growth and creates reducing conditions that indirectly stimulate the biological reduction of Cr(VI) in the soil (Wang et al., 2019). X-ray absorption near edge structure spectroscopy revealed that increasing soil OM favors the redox transformation of Cr(VI), resulting in prevalence of reduction product Cr(III) (Jardine et al., 2013). Microorganism multiplication in soils with high OM levels creates a lowered state and modifies the soil Eh to decrease harmful Cr(VI) organisms to less harmful. Numerous organic modifications (plant tissue, black carbon, compost, farm-yard manure, and poultry manure) are widely utilized in remedial and soil restoration procedures (Kanchinadham et al., 2015).

6. Cr uptake and translocation in plants

In plants, the mechanism of Cr uptake is yet to be discovered. Cr is a non-essential mineral with no specialized mechanism for absorption and is also reliant on Cr speciation (Adhikari et al., 2020). The contact between roots and soil is the first interaction for uptake of Cr by plants and the uptake by plant rootsis based on plant type and Cr speciation [Cr(III) and Cr(VI)] (Shahid et al., 2017). In addition, soil pH, Cr content, salinity, and the availability of dissolved salts also influence Cr uptake in aqueous media (Babula et al., 2008). Furthermore, studies have shown that the creation of Cr-organic ligand complexes improves Cr absorption in plants (Hao et al., 2022). In various plant species, uptake of Cr takes place via the same carriers as for essential ions for plant metabolism (Ding et al., 2019). In plant species, the oxidation state of the Cr ions, and the concentration of Cr in the growth media influence the distribution and translocation of Cr within plants (Shahid et al., 2017). Plants can take up both Cr(III) and Cr(VI) through epidermal root cells, but there are significant differences in the pathways and efficiency of their entry into cells. Cr(VI) is more easily taken up by plants as compared to Cr(III) due to higher water solubility and higher transmembrane efficiency (Aharchaou et al., 2017). The uptake of Cr(III) is a passive process with no use of energy, most Cr(III) is taken up by roots through the same carriers as for essential elements (Singh et al., 2013). However, the routes of Cr(III) entry into cell are not well established. The uptake of Cr(VI) is an active process and relies on phosphate or sulfate carriers owing to similarity in structure (Ding et al., 2019). Cr mobility in plant roots is low as compared to other heavy metals (Sharma et al., 2020). Thus, the concentration of Cr in the roots can be 100 times more than that of the shoots (Gupta and Sinha, 2006). Cr may be sequestered in the vacuoles of root cells as a protective strategy, resulting in increased Cr accumulation in roots (Mangabeira et al., 2011). As a result of this mechanism, plants have some inherent tolerance to Cr toxicity (Srivastava et al., 2021). Furthermore, Cr translocation from the roots to the aerial shoots is quite limited, and it is highly dependent on the chemical form of Cr within the tissue (Shahid et al., 2017). Cr(VI) is changed to Cr(III) in plant tissues, which tends to adhere to cell walls, preventing Cr from being transported further into plant tissues (Kabata-Pendias and Szteke, 2015).

Cr(III)Cr(VI)The activation of ferric reductase enzymes in roots leads to active transport of Cr(VI) and results in its rapid conversion to Cr(III) (Zayed et al., 1998). This transformed Cr(III) attaches to the cell wall, preventing it from transporting through the various plant tissues (Shanker et al., 2009). Increased MSN1 (a potential yeast transcriptional activator) production resulted in increased Cr and S absorption and tolerance in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) (Shahid et al., 2017). In the transgenic Indian mustard plant, Cr(VI) stress promotes the expression of SHST1 gene, a high affinity sulfate transporter located on the plasma membrane that mediates Cr(VI) uptake by roots (Lindblom et al., 2006). Studies on sulfate transporters confirmed that Sultr1;2 gene knockout in Arabidopsis thaliana inhibits Cr(VI) uptake rate, whereas its over expression in rice significantly increases the Cr(VI) uptake by roots (Xu et al., 2021).

7. Effect of chromium toxicity in plants

Cr may enhance plant development at low concentrations and hinder plant growth at higher concentrations, according to some research, even though there is no concrete proof to substantiate its positive participation in plant metabolism (Ao et al., 2022). In plants, higher concentration of Cr significantly affects various biochemical and morphological parameters i.e., reducing seed germination, plant biomass, photosynthetic efficiency, root damage, and eventually causes plant mortality (Zayed and Terry, 2003; Zaheer et al., 2015; Figure 2 ; Table 1 ). Excess amounts of Cr can cause stunted growth of the plant (Faisal and Hasnain, 2005a). Essential nutrients and Cr interaction can disturb the uptake pattern of various essential nutrients calcium (Ca2+) and magnesium (Mg2+) in the plant because of the interaction of Cr with soil (Zupančič et al., 2004). Moreover, agricultural soils with high levels of Cr contamination adversely affect the crop yield (Kanwal et al., 2014; Adrees et al., 2015a). Throughout the growth cycle, plants are sensitive to Cr toxicity, and detailed information about the toxic effect of Cr on morpho-physiological and biochemical parameters and toxicity mechanisms is highlighted below.

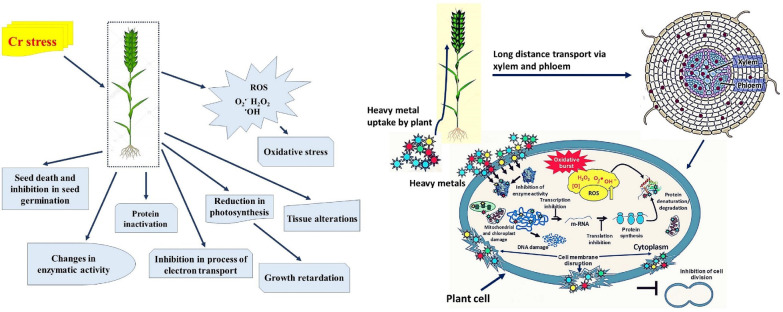

Figure 2.

Schematic representation from the sequestration of chromium (Cr) into a plant cell to the plant’s death, through a series of events. Cr toxicity decelerates photosynthesis by preventing seedling establishment and root growth, which in turn slows down essential nutrient and water uptake. Moreover, toxicity of Cr alters photosynthetic pigments content in plant leaves, and these alterations typically result in chlorosis and necrosis of the leaves. In addition, to decreasing membrane integrity, high Cr stress also causes the loss of osmolytes and cell turgor pressure, which causes stomatal closure impacting overall osmoregulation. Additionally, Cr toxicity disrupts the equilibrium between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the antioxidant defense system, which causes ROS to build up and cause oxidative damage to cellular organelles. DNA damage, protein and lipid synthesis, lipid peroxidation, enzyme activity, and impaired cell division are all affected by the formation of ROS, which ultimately leads to plants death (Shanker et al., 2005; Rizvi et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Effect of chromium stress on yield of some representative field crops.

| Plant species | Cr concentration | Experiment type | Yield reduction (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cauliflower | 0.5 mM | Pot experiment | 50 | Chatterjee and Chatterjee (2000) |

| Sunflower | 60 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 52 | Fozia et al. (2008) |

| Spinach | 150 mg L-1 | Pot experiment | 45.1 | Deepali (2009) |

| Pea | 0.4 mM | Pot experiment | 27.6 | Tiwari et al. (2009) |

| Chickpea | 67.5 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 15.3 | Wani and Khan (2010) |

| Spring barley | 150 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 31 | Wyszkowski and Radziemska (2010) |

| Paddy rice | 200 mg L-1 | Field experiment | 37.5 | Sundaramoorthy et al. (2010) |

| Canola | 3.49 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 21 | Ahmad et al. (2011) |

| Wheat | 160 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 41.03 | Parmar and Patel (2016) |

| Oat | 12.95 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 44 | Wyszkowski and Radziemska (2013) |

| Okra | 30.46 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 50 | Maqbool et al. (2015) |

| Maize | 0.15 mM | Pot experiment | 26 | Anjum et al. (2017) |

| Mustard | 100 mg L-1 | Pot experiment | 27 | Kumar et al. (2020b) |

| Wheat | 50 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 27 | Seleiman et al. (2020) |

| Okra | 2.53 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 46.91 | Zeeshan et al. (2021) |

| Tomato | 1.5 mM | In vitro culture | 50 | Hafiz and Ma (2021) |

| Wheat | 200 mg kg-1 | Pot experiment | 58.6 | Ahmad et al. (2022) |

7.1. Germination and stand establishment

Considering that seed germination is the first physiological activity that Cr affects, a seed’s capacity to germinate in a medium containing Cr would be an indication of how tolerable it is to this metal (Shanker et al., 2005; Rath and Das, 2021). Symptoms of Cr phytotoxicity comprise the early development of seedling or impediment of seed germination, suppressed root growth, and leaf chlorosis. Cr prominently reduced the seed germination of different plants such as vegetables cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L.), citrullus (Citrullus vulgaris), and crops, wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), and maize (Zea mays L.) (Shahid et al., 2017; Ao et al., 2022). It was noted that higher toxicity of Cr in soil reduced the germination rate of jungle rice (Echinochloa colona), bush bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), alfalfa (Medicago sativa), and sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) by 25%, 48%, 23%, and 57%, respectively as compared with control (Shanker et al., 2005).

According to several investigations, with an increase in Cr concentration in the external medium i.e., soil/nutrients solution, the DNA content of bean seedlings gradually improved and as a result, the DNA content followed a trajectory that was the opposite of the radical expansion (DalCorso, 2012). Higher concentrations of Cr significantly minimized the bean roots by interfering the cell division process in roots (Zeid, 2001; Singh et al., 2013). During seed germination, accumulated reserve materials like proteins and starch are hydrolyzed to produce precursors like sugars and amino acids for the development of embryo axis as well as substrates for different metabolic processes (Ao et al., 2022). Additionally, when the Cr content gradually increased, the activity of the α- and β-amylases of the developing seeds decreased, which may be responsible for the inhibition of seed germination (Oliveira, 2012). Seed germination of black gram (Vigna mungo) was reduced to 50.70% with the presence of Cr(VI) contents (300 µM) in nutrient solution (Rath and Das, 2021). Singh and Sharma (2017), observed that chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and green bean (Phaseolus aureus) seed germination was decreased by 42.60 and 53.53%, respectively, when Cr was present at higher concentrations (100 mg/L). More than 90% of the 45 tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) genotypes displayed reduced and delayed germination within 14 days under 78 mg/L Cr(VI) stress, according to a recent study by Hafiz and Ma (2021).

Higher ROS production from Cr treatment may have facilitated the breakdown of stored nutrients in seeds cotyledon, which ultimately leads to changing the characteristics of cell membranes, hence results in reduced seedling germination (Shafiq et al., 2008; Shah et al., 2010). The significant reduction in seedling length under Cr stress might be due to the reduced water potential and secondary stress-causing obstructed nutrient absorption (John et al., 2009). Because there are fewer meristematic cells in root tips than in cotyledons and shoot apex, Cr treatment also results in diminished seedling growth, particularly of roots (Rath and Das, 2021). The hydrolytic enzymes’ activity is impacted by Cr stress, depriving the radical and plumule of seed and ultimately slowing seedling growth (Stambulska et al., 2018). According to Sundaramoorthy et al. (2009), hexavalent Cr concentration even results in chromosomal abnormalities in the roots of seedling, which stimulate c-mitosis and result in extremely reduced root growth. The amylase activity of seeds under Cr stress may be inhibited, which would lead to a reduction in the transfer of carbohydrates to the germ (Stambulska et al., 2018). Additionally, Cr treatment stimulates protease activity, which results in a lower rate of seed germination or possibly seed death (Khan et al., 2020; Ao et al., 2022).

7.2. Uptake and interaction with other mineral elements

By altering the soil’s nutritional composition and controlling plant nutrient absorption, distribution, and transport, Cr have a significant impact on the metabolism of minerals and causes phytotoxicity in soil-plant systems (Chen et al., 2018). Cr can alter the mineral nutrition of plants in a complex way because of its structural resemblance to some critical elements (Ding et al., 2019). Researchers have focused most of their emphasis on how Cr affects the absorption and accumulation of other inorganic nutrients. Different processes are used by plants to absorb Cr (Ao et al., 2022). Both forms, i.e., Cr(III) and Cr(VI), have the potential to obstruct the uptake of several other ionically related ions, including Fe and S. Both Cr(III) and Cr(VI) have been reported to interfere with macronutrient elements (Ca, K, Mg, N, P, and S) and trace elements (Cu, Fe, Mn, Si, and Zn) through competitive uptake, even though the methods and pathways by which plants absorb Cr(III) and Cr(VI) differ (Ding et al., 2019; Askari et al., 2021; Ashraf et al., 2022a). Complex barriers caused by Cr prevent plants from absorbing essential minerals. According to Shahid et al. (2017), the existence of Cr and critical nutrients in soil and plant cells may be the cause of their antagonistic interactions and competitive absorption. Recent studies reported that excessive Cr toxicity minimizes adsorption sites and forms insoluble/low-bioavailable compounds in rhizosphere soil, which prevents the accumulation of vital nutrients including Ca, Cu, Fe, Mg, P, S, and Zn (De-Oliveira et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018). The absorption of essential nutrients (such as N, P, K) in paddy irrigation reduced with an elevation in the level of Cr(VI) (Sundaramoorthy et al., 2010). In addition to Cr toxicity, a reduction in Fe content in leaf tissue indicates Cr(VI) involvement in Fe supply, leading to instability in Fe metabolism instability (Gopal et al., 2009).

This reduced uptake of nutrients might be occurred because of the decrease in root development and restriction of root penetration under Cr stress, or because of the reduction in translocation of essential elements (Shahzad et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2020). Therefore, Cr(VI) competitive binding to common carriers may decrease the absorption of several nutrients. The suppression of plasma membrane H+ ATPase could be a possible explanation for the lower absorption of many of these elements in Cr stressed plants (Shanker et al., 2005). Additionally, the significant Cr buildup in the plant cell wall may harm the plasmodesmata, which serve as crucial channels for the transport of mineral nutrients, resulting in an imbalance in their metabolism (Kitagawa et al., 2015).

7.3. Plant water relations

The detrimental consequences of Cr concentrations cannot be precisely predicted in soil and surface water (Waseem et al., 2014). Plant roots serve the primary purposes of absorbing inorganic and organic nutrients, and water, protecting and anchoring the plant body to the ground, storing nutrients, and promoting vegetative reproduction (Rucińska-Sobkowiak, 2016). These organs typically contain higher Cr concentrations than in the above-ground plant and are known to be the first points of contact with harmful metals like Cr ions (Shanker et al., 2005; Burkhead et al., 2009). Accumulation of Cr ions in tissues may influence soil water absorption and tends to lower the water content in plant roots (Kumar et al., 2016). The direct involvement of Cr ions with the guard cells or the early effects of Cr buildup on plant parts (such as stems and roots) are what induce stomata to close (Ahmed et al., 2016). It is believed that Cr’s effects on water supply in soils, root development, reduced water absorption, and other harmful effects are distinct from its influence on the connection between plants and soil water (Chow et al., 2018). The osmotic ability of soil solution in Cr-enriched soils may be less than that of root cell sap (Vernay et al., 2007). In these circumstances, osmotic pressure, and soil solution will significantly restrict plant water absorption levels (Vernay et al., 2007; Rucińska-Sobkowiak, 2016). When the toxic metal i.e., Cr concentration hits the 10-3 M threshold level, osmotic pressure is thought to exist (Levitt, 1972). Adjustments to endogenous factors, such as root structure and morphology, are more likely to influence plant water absorption indirectly (Kumar et al., 2016). After being exposed to Cr, green amaranth (Amaranthus viridis) showed a substantial decrease in total root area (Sampanpanish et al., 2006). Reduced root hair surface, primary root elongation, increased root dieback, and poor secondary development is abnormalities in Cr-stressed plants that affected how water and plants interacted in the soil (Shanker et al., 2005; Chow et al., 2018). In epidermal and cortical cells of bush bean plants unveiled to Cr, there was impaired turgor and plasmolysis (Vazques et al., 1987). According to Gopal et al. (2009), Cr(VI) inhibits the physiological water supply, as evidenced by a drop in leaf water capability and elevation in diffusional stiffness in spinach leaves, implying that they are growing under water stress. Cr-induced structural changes reduce plant ability to acquire water in the soil and cause insufficient root-soil interaction (Ertani et al., 2017). A broad range of water-related changes is brought about by Cr exposure throughout the entire plant. Reduced water absorption and restriction of short-distance water transport in the apoplast and symplast pathways are effects of Cr toxicity in roots (Srivastava et al., 2021). Additionally, the apoplast’s resistance to water flow is increased by the thickening of the cell wall brought on by Cr ions or other incrusting substances within cell walls (Bhalerao and Sharma, 2015). The inhibition of aquaporin functions and variations in protein expression is most likely to blame for the impaired water transport through the membrane (Ullah et al., 2019a). Such changes affect the flow of water via the vascular system and reduce root sap exudation (Chen et al., 2010). Long-distance water transfer is reluctant, which causes a reduction in leaf water and, as a result, a water deficit in leaves (Shahid et al., 2017). Events that enhance plants’ capacity to retain water include a quick fall in root vacuolization, osmotic ability, and alternation in the tissues of stems and leaves (Srivastava et al., 2021; Ao et al., 2022).

7.4. Plant root and shoot growth

Cr has a significant impact on root growth and development in addition to seed germination (Shahid et al., 2017). The roots, which are a major organ for nutrient uptake and are consequently linked to Cr uptake, act as a major source of Cr toxicity in plants (Srivastava et al., 2021). A considerable reduction in root length of sour orange (Citrus aurantium) seedlings was discovered while conducting an experiment in a greenhouse experiment, under doses of 200 mg/kg Cr(III), (Shiyab, 2019). In water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes), Cr promotes root length, width, and laminal length at low concentrations (0.25 mg L-1) when compared to controls, but at higher concentrations (2.5 mg L-1), the root length was observed to be reduced (Kakkalameli et al., 2018). Similarly, it was observed that Cr toxicity minimized the shoot length of oats (Avena sativa) by 41% as compared to control (Shanker et al., 2005). The growth of lateral roots and the quantity of secondary roots are further effects of Cr (Mallick et al., 2010; Srivastava et al., 2021). Root cell division may have decreased because of the Cr-induced reduction in root length. Cr(VI) prevents plants from absorbing nutrients and water, which shortens roots and reduces cell division (Shahid et al., 2017). Treatment with Cr(VI) in maize (Zea mays) resulted in shorter and fewer root hairs, as well as a brownish color (Mallick et al., 2010). Even various studies claimed that the cell cycle extended when exposed to Cr toxicity (Sundaramoorthy et al., 2010). According to Zou et al. (2006), green amaranth (Amaranthus viridis) root tip cells had their mitotic index reduced because of exposure to Cr.

Another growth metric that is frequently impacted by Cr exposure is plant stem growth (Ding et al., 2019). The shoot length of sunflower (Helianthus annus) was observed to decrease when Cr(VI) content increased (Fozia et al., 2008). Similarly, when the soil’s Cr(III) concentration was raised in sour orange (Citrus aurantium) the shoot length decreased by 90.4% at 200 mg kg-1 of Cr (Shiyab, 2019). After being exposed to 600 mg kg-1 Cr(III), tea (Camellia sinensis) developed a short stem that grew slowly (Tang et al., 2012). According to Lukina et al. (2016), Cr(VI) toxicity (1000 mg kg-1) in 32 species had a negative impact on 94% of the species’ stem growth. The Cr-reduced root growth and development, which results in decreased water and nutrient transfer to the above-ground plant components, may be the cause of the decreased stem growth and height (Srivastava et al., 2021). Additionally, increased Cr transport to shoot tissues may directly interact with delicate plant tissues (leaves) and functions (photosynthesis), affecting shoot cellular metabolism and resulting in a shorter plant (Sharma et al., 2020).

7.5. Oxidative damages

In general, trace metal stress plants by oxidizing them either directly or indirectly by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Qianqian et al., 2022). Cr toxicity causes oxidative damage in plants through overproduction of ROS such as O2-, H2O2, and OH- (Shahid et al., 2017; Basit et al., 2022). The process of reducing Cr(VI) to lower oxidation states is the root cause of Cr toxicity, where only ROS are produced (Shanker et al., 2005; Shahzad et al., 2018). Wakeel et al. (2020) reported that when Cr(VI) is radical reduced, the unstable intermediates i.e., Cr(IV) and Cr(V), which contribute to the generation of ROS, are created. Various plant organelles, such as mitochondria, peroxisomes, and chloroplasts, create these ROS as by-products of diverse metabolic activities (Srivastava et al., 2021). The primary causes of ROS generation in plant organelles i.e., mitochondria and chloroplasts are the inhibition of CO2 fixation and excessive decrease of the electron transport chain (Ao et al., 2022). Furthermore, the production of ROS is caused by the leakage of electrons from O2 caused by electron transport activity in mitochondria, peroxisomes, and chloroplasts (Anjum et al., 2016b). Cr toxicity in plants tends to share electrons, sulfhydryl groups in proteins establish covalent interactions with redox-inactive minerals (Anjum et al., 2017). Numerous studies have been reported showing a dramatic escalation in ROS (Sharma et al., 2019) with an increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) content with Cr toxicity (Adrees et al., 2015b). A pivotal part as signaling pathways molecules and mediators of responses to cellular metabolic disturbance, environmental stimuli, pathogen infection, various developmental stimuli, and a variety of biological and physiological responses are played by plants under normal circumstances when appropriate concentrations of ROS are present (Waszczak et al., 2018). However, the overproduction of ROS in plants results in disruption of cell homeostasis, cell membrane or protein fragmentation, DNA strand breaks, deactivation and degradation of genetic material, and harm to photosynthetic pigments (Srivastava et al., 2021; Ao et al., 2022). Similar findings were observed by Ullah et al. (2019b), who reported that increased ROS generation in plants with Cr toxicity results in oxidative damage, inflicting damage to DNA, lipids, pigments, and proteins, and stimulating the lipid peroxidation functions. These effects inhibit plant growth by preventing cell division or inducing cell death, which lowers biomass production (Wakeel et al., 2020). According to Shahid et al. (2014), the duration of exposure, Cr content, plant species, stage of development, level of stress, and particular organs all affect how hazardous Cr-induced ROS are for plants

7.6. Antioxidant defense system

Complex defense approaches, including non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidants, have evolved to prevent oxidative damage to plant cells (Semchuk et al., 2009; Ashraf et al., 2021; Zulfiqar et al., 2021). As with many other metals, excess Cr can promote the development of ROS and generally increases the activity of anti-oxidative enzymes ( Table 2 ). Activities of enzymatic antioxidants such as catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), peroxidase (POD), glutathione reductase (GR), superoxide dismutase (SOD), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), glutathione-S-transferases (GST), monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR), and non-enzymatic antioxidants such as glutathione (reduced form, GSH, and oxidized type, GSSG), ascorbic acid (AsA), and phenolic metabolites were significantly increased under Cr toxicity to minimized the counter effects of ROS production in plant metabolic processes (Shahid et al., 2017; Jan et al., 2020). Cr exposure was found to increase the content of GSH and AsA, while the concentration of phenolic contents was depleted (Panda, 2007). Moreover, non-enzymatic antioxidants that control the levels of ROS in cells, such as tocopherols, carotenoids, GSH, proline, and AsA are regarded as moderators of oxidative damage (Adrees et al., 2015a). Antioxidant capabilities can also be found in other low-molecular-weight substances such as tocopherols, carotenoids, and phenols (Akyol et al., 2020; Ao et al., 2022). However, their antioxidants’ activity and availability are dependent on secondary metabolites’ capacity to synthesize specific compounds, which varies widely among different plant species (Akyol et al., 2020).

Table 2.

Effects of chromium stress on activities of different antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in different plants.

| Plant species | Enzymes (%) | Culture | LPO indicator (%) | Cr exposure level | Exposure duration (days) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | APX (245↑), CAT (35.1↓), SOD (31.6↑), POD (59.9↓) | Hydroponic | MDA (65↑) | 20 µM | 10 | Cao et al. (2013) |

| Canola | CAT (39.42↓), SOD (42.85↑), POD (82.14↑), APX(37.5↓) | Hydroponic | MDA (66.67↑) | 50 µM | 2 | Yıldız et al. (2013) |

| Radish | CAT, SOD, POD | Hydroponic | MDA | 2- 8 mM | 3 | Sayantan (2013) |

| Pakchoi | CAT (37.84↓), SOD (47.04↓), POD (41.43↓) | Soil | MDA (48.5↑) | 0, 50, 100 and 200 mg kg-1 | 2 | Zhang et al. (2013) |

| Cotton | CAT (16.66↑), SOD (74.07↓), POD (48.5↑), APX (44.44↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (65.9↑) | 0, 10, 50 and 100 µM | 7 | Daud et al. (2014) |

| Tossa jute | CAT (65.28↑), SOD (56.83↑), POD (59.13↑), GR (57.94↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (47.89↑) | 100, 200 and 400 mg kg-1 | 7 | Islam et al. (2014) |

| Black nightshade | SOD (13.51↑), POD (22.22↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (22.22↑) | 0, 0.5 and 1 mM | 2 | UdDin et al. (2015) |

| Santa-maria | SOD (23.26↑), POD (42.85↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (38.46↑) | 0, 0.5 and 1 mM | 2 | UdDin et al. (2015) |

| Rapeseed | CAT (54.54↑), SOD (49.37↑), POD (23.08↑), APX (57.5↑) | Soil | MDA (70.2↑) | 0, 100 and 500 µM | 15 | Afshan et al. (2015) |

| Indian mustard | SOD (66.14↑), CAT (42.08) ↑), POD (59.11↑), APX (33.15↑), GR (46.97↑), DHAR (70.38↑), MDHAR (71.52↓) | Hydroponic | MDA (50.36↑) | 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 mM | 30 | Kanwar et al. (2015) |

| Egg plant | APX (12↑), GST (38↑), GR (20↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (13↑) | 25 µM | 7 | Singh et al. (2017) |

| Amaranth | CAT (44↑), SOD (50↑), POD (74↑), GST (101↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (108↑) | 0, 10 and 50 µM | 7 | Bashri et al. (2016) |

| Maize | CAT (48.52↑), SOD (17.14↑), POD (36.67↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (126↑) | 100 µM | Anjum et al. (2016b) | |

| Kenaf | CAT (151.43↑), SOD (135.79↑), POD (58.46↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (53.51↑) | 1.5 mM | 6 | Ding et al. (2016) |

| Rice | CAT (74.42↓), SOD (9.33↓), POD (64.91↓), GR (54.84↓) | Hydroponic | H2O2 (86.89↑) | 100 µM | 7 | Huda et al. (2016) |

| Green gram | CAT (31.03↑), SOD (46.25↑), POD (34.21↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (51.67↑) | 0, 250 and 500 µM | 7 | Jabeen et al. (2016) |

| Sunflower | CAT (70.83↑), SOD (75.61↑), POD (20.12↑), APX (62.5↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (71.43↑) | 0, 5, 10 and 200 mM | 15 | Farid et al. (2017) |

| Wheat | CAT (40.1↓), APX (13.46↑) | Soil | MDA (16.67↑) | 10 and 22 mg kg-1 | 30 | González et al. (2017) |

| Barley | CAT (41.82↓), APX (22.5↑) | Soil | MDA (27.27↑) | 10 and 22 mg kg-1 | 30 | González et al. (2017) |

| Cauliflower | CAT (34.78↑), SOD (37.5↑), POD (35.1↑) | Hydroponic | MDA (63.33↑) | 0, 10, 100 and 200 µM | 7 | Ahmad et al. (2017) |

| Sorghum | CAT (66.67↑), SOD (90.1↑), APX (80.2↑), GR (64.5↑), GST (36.5↓) | Hydroponic | MDA (61.67↑) | 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 mg kg-1 | 7 | Yilmaz et al. (2017) |

| Indian mustard | CAT (39↓), SOD (16↑), APX (28↑), GR (16↑), GPX (14↓), DHAR (50↓), MDHAR (31↓) | Hydroponic | MDA (101↑) | 0.15 and 0.3 mM | 5 | Al-Mahmud et al. (2017) |

| Maize | GR (29.33↓) | Hydroponic | MDA (65.71↑) | 50, 100 and 200 mg L-1 | Adhikari et al. (2020) | |

| Tomato | – | Petri dish | MDA (63.23↑) | 50 µM | Khan et al. (2020) |

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), glutathione reductase (GR), glutathione S-transferase (GST), monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR), peroxidase (POD), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA).

Plant roots with high levels of Cr(III) content, SOD increased primarily, while the quality of H2O2 displayed a discontinuous pattern for the various Cr(III) absorption, which was assumed because of heterogeneity in the activity of various peroxidases (Kováčik et al., 2013). Plant resistance may have surpassed the innate immune level for high doses of Cr in this case, resulting in the observed declines in enzyme activity. With increasing Cr(III) content, there was an increase in proline content. Usman et al. (2020), reported that giant milkweed (Calotropis procera) treated with Cr(VI) (20 mg L-1) showed enhanced activity of CAT, GR, and SOD with SOD activity being the greatest (up to 12.2 U mg-1). The formation of reducing agents (GSH and AsA metabolites) that catalyze the dismutation of H2O2 to O2 - and H2O is aided by the synergistic effects of GR, CAT, and APX and which all play critical roles in scavenging ROS (Bashir et al., 2020). When Cr metal binds to proteins, whether in the catalytic domain or elsewhere, it inhibits enzyme reactants by attaching unique functional groups to proteins, resulting in enzymatic function modifications (Gupta et al., 2010). In addition, from the enzyme, dislocation of essential cations the equilibrium of ROS in cells is disrupted by binding sites, and consequently, ROS is produced in dramatic amounts (Shahzad et al., 2016). The oxidation number of glutathione (GSH) and its constituents appear to bind and utilize Cr metal, which is important for reducing ROS (Lee et al., 2003). In addition, NADPH oxidase contributes to oxidative damage as it is associated with Cr (Pourrut et al., 2013). NADPH oxidases can consume cytosolic NADPH in the existence of Cr metal and generate free radical O2; it is quickly converted to H2O2 through SOD enzyme (Shahid et al., 2017). In the presence of NADPH oxidase, Cr-generated free radicals are external to the plasma membrane, where the pH is generally lower than on the interior side of the membrane (Sagi and Fluhr, 2006). The transporter membrane promotes Cr ingestion and affects the plasma membrane’s ability to produce ROS (Maiti et al., 2012). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of scavenging ROS by antioxidants and non-enzymatic antioxidants are yet unknown and need more research.

7.7. Photosynthetic activity and yield formation

Phytotoxicity of Cr adversely affects various metabolic processes i.e., CO2 fixations, electron transfer, photophosphorylation, and enzyme concentration, which directly impairs photosynthesis (Anjum et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2020; Ashraf et al., 2022b). Taken to be critical indices that measure plant photosynthesis under Cr stress are photosynthetic rate, photosynthetic pigments, and photochemical efficiency (Ma et al., 2016). Cr is a potent inhibitor of plant photosynthesis, according to numerous studies (Shanker et al., 2005; Shahzad et al., 2016; Bashir et al., 2020). According to Mathur et al. (2016), Cr toxicity prevents CO2 fixation, electron transfer, enzyme activity, and photophosphorylation in plants. This destroys the photosynthetic apparatus, specifically light-harvesting complex II, PSI, and PSII, and prevents the production of Calvin cycle enzymes (responsible for ATP production) (Sinha et al., 2018). In a study, Anjum et al. (2016a) found that maize plants exposed to Cr stress had significantly lower the levels of net photosynthesis, chlorophyll contents, gas exchange capacity, transpiration rate, water use efficiency, and stomatal conductance. The degradation of photosynthetic pigments caused by exposure to the high concentration of Cr leads to reduction in light-harvesting capacity (Handa et al., 2018b; Srivastava et al., 2021). Net photosynthetic rate (Pn) and chlorophyll content in wheat (Triticum aestivum) were decreased as Cr exposure period gradually increased (Srivastava et al., 2021). Cr prevents mitochondrial electron transport in higher plants, which increases the production of ROS and causes chloroplast modifications, pigment changes, and oxidative stress (Sharma et al., 2016). One of the crucial plant parts involved in photosynthesis is the leaf and total leaf area (Srivastava et al., 2021). In rice (Oryza sativa) the Cr(VI) toxicity reduced the number of leaves per plant by 50% while significantly affecting the overall leaf area and photosynthesis activity of plant (Sundaramoorthy et al., 2010). Under 3.4 mM Cr(VI) toxicity in nutritional media, smooth mesquite (Prosopis laevigatar) was shown to have fewer leaves that significantly affect the chlorophyll content and photosynthesis activity of plant (Buendía-González et al., 2010). Furthermore, it was shown that Cr toxicity significantly decreased the leaf’s net photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, and intercellular CO2 concentration, of sunflower with reductions of 36%, 71%, 57%, and 25%, respectively (Sharma et al., 2020).The first requirement for large plant yields is high plant biomass (Shahid et al., 2017). Cr is known to have negative impacts on several physiological and metabolic processes, which compromises plant production and yield equally (Ali et al., 2015). Various studies highlighted that Cr phototoxicity results to minimize plant biomass and yield of melon (Cucumis melo) (Akinci and Akinci, 2010), wheat (Triticum aestivum) (Adrees et al., 2015a), french bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) (Sharma et al., 2016), okra (Hibiscus esculentus) (Amin et al., 2013), turnip mustard (Brassica campestris) (Qing et al., 2015), Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) (Ding et al., 2019), common duckweed (Lemna minor) (Reale et al., 2016), wheat (Triticum aestivum) (Ali et al., 2015), barley (Hordeum vulgare) (Ali S. et al., 2013) maize (Zea mays) (Anjum et al., 2017), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) (Farooq et al., 2016), makoi (Solanum nigrum) (UdDin et al., 2015). In plants, higher concentration of Cr significantly affects various biochemical and morphological parameters i.e., minimized nutrient and water uptake, reduction in cell division, nutrients imbalance (translocation and uptake), the inefficiency of inorganic nutrient uptake by plant, higher oxidative stress, and ROS formation, oxidative stress damage to sensitive cell organelles such as chlorophyll, mitochondria, lipids, proteins, and reduction in photosynthesis activity that results to minimize the growth, biomass, yield of plant (Shanker et al., 2005; Shahid et al., 2017; Ao et al., 2022). At the cellular, molecular, organ, and plant levels, each of these elements, alone or in combination, have an impact on plant growth, development, and yield (Shahid et al., 2017). However, the type of plant and chemical speciation of Cr will determine which of these factors will be more severely impacted. The impact of Cr on plant development, however, differs depending on the variety of plants. In general, transgenic and hyperaccumulator plants have a lot of potential for Cr tolerance and selective accumulation (Sarangi et al., 2009).

7.8. Enzymatic activity

Cr stress can stimulate potentially three forms of metabolic changes in plants: (i) modification in the synthesis of organic pigments facilitates the growth and development of plants (e.g., anthocyanin, and chlorophyll (Shanker et al., 2005; Shahid et al., 2017); (ii) enhanced the synthesis of metabolites (e.g., ascorbic acid, and glutathione) as a direct reaction to Cr stress that will affect the plants (Srivastava et al., 2021); and (iii) modifications in the metabolic-pool to channelize the synthesis of new biochemically associated metabolites that will confer tolerance or resistance to Cr stress (e.g., histidine and phytochelatins) (Shanker et al., 2005; Ao et al., 2022). Initially at germination stage, toxicity of Cr significantly reduced the activity of gibberellin (GA) and enhanced the activity of abscisic acid (ABA) (major factor of seed dormancy), which lead to seed imbibition and reduced germination rate (Seneviratne et al., 2019). Similarly, according to Yan et al. (2014) hydrolyzing enzymes secreted by the aleurone layer of seeds are crucial for seed germination. By releasing food reserves from the endosperm, enzymes i.e., acid phosphatases (ACPs), α-amylases, and proteases promote effective seedling establishment and growth (see section 5.1). Acid phosphatase, α-amylase, and alkaline phosphatase activity were decreased in the endosperm of cereals i.e., wheat, oat, barley, and maize seeds when Cr was present (Seneviratne et al., 2019). In addition, the enzymes involved in the assimilation of important nutrient nitrogen i.e., nitrogenase, nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, glutamine synthetase, glutamate synthase, glutamate dehydrogenase were significantly reduced with the contamination of Cr in plants (Sangwan et al., 2014). Deficiency of nutrients in plants due to Cr toxicity results into degradation of various amines, alkaloids, pigments, vitamins, coenzymes, nucleic acids, and nucleotides as nutrients are structural component of these organelles (Shanker et al., 2005; Sangwan et al., 2014). Similarly, the activities of enzymes involved in photosynthesis NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME), pyruvate, phosphate dikinase (PPDK), and Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), plant respiration i.e., α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and isocitrate dehydrogenase, and gene transcription i.e., RNA polymerase are significantly reduced in various plants due to phototoxicity of Cr.

8. Remediation of Cr contaminated soils

The concentration of metals in polluted soils is affected by multiple chemical and biological attributes (Alengebawy et al., 2021). Soils preserve heavy metals by adsorbent, crystallization, and chelation; nevertheless, such interactions restrict their mobility and bioavailability (Yan et al., 2020). However, the implementation of chemical processes, such as organic and inorganic modifications in field can complement this natural attenuation process (Mench et al., 2006; Shahid et al., 2017). These technologies generally minimized the availability of Cr, boost the fertility of the soil, and increase plant growth (Gavrilescu, 2022). Organic amendments (compost) possess a significant proportion of humified organic material and may restrict the availability of Cr in the soil, even though they allow vegetation to be regenerated (Lwin et al., 2018). On the other hand, phosphate fertilizers are useful in metal inactivation through the creation of stable mineral phosphate within the inorganic amendments (Ahmad et al., 2019). Biological options, particularly phytoremediation, have been considered reliable, ecologically acceptable, and cost-effective replacement to physicochemical approaches for the restoration of depleted environments. Various physicochemical activities that can be used to eliminate Cr-polluted environments include ionization, precipitation, reverse osmosis, evaporation, and chemical reduction (Roy and Bharadvaja, 2021). Moreover, there are numerous issues linked with these processes, like permeate flux, inflated prices, high energy consumption, and low extraction efficiency shows that these are less significant in industry. In general, the main considerations in choosing an acceptable treatment to eliminate metals are technological applicability, eco-friendly, and cost-effectiveness (Acheampong et al., 2010).

8.1. Phytoremediation

Phytoremediation is a process in which plants are used for remediation of polluted soils and considered an eco-friendly and green approach (Ali H. et al., 2013; Srivastava et al., 2021). There are various strategies associated with phytoremediation techniques including phytoextraction, rhizofiltration, phytovolatilization, biotransformation, rhizdegradation, phytostabilization, and phytorestoration (Yan et al., 2020). Phytoextraction is focused on the ‘hyperaccumulation’ process, and phytostabilization is focused on the surface complexation mechanism and both are involved in metal affinity phenomena (Xu et al., 2012). Phytoextraction and phytostabilization are two of those practically and economically viable solutions for treating metal-polluted soils (Kuiper et al., 2004). Biotransformation is another term for phyto-transformation. That is the separation of pollutants absorbed by plants via internal metabolic pathways or the segmentation of pollutants just outside of the plant because of plant-generated chemicals (such as enzymes). Plant absorption and metabolism are the primary components, which result in plant deterioration. The uptake of contaminants by plant roots and its conversion to a gaseous state, and release into the atmosphere is referred as phytovolatilization. Volatilization through leaves (ITRC, 2009) is the phytovolatilization process. Degradation by plant rhizospheric microorganisms is the method referred as rhizodegradation (Mench et al., 2009). This ecologically accepted technology is successfully used to fix soils that are polluted by various contaminants. Furthermore, phytoremediation is increasingly used as a technical alternative to treat contaminated water in various forms of wetland treatment (Zhang et al., 2010). In crux, phytoremediation is a feasible, socially, and economically suitable, and eco-friendly solution for the soils polluted with Cr. Nonetheless, to counteract the health risks due to Cr concentration in edible parts of food crops, the proportion of Cr in edible parts of food crops should be closely scrutinized.

8.2. Microbe-assisted remediation

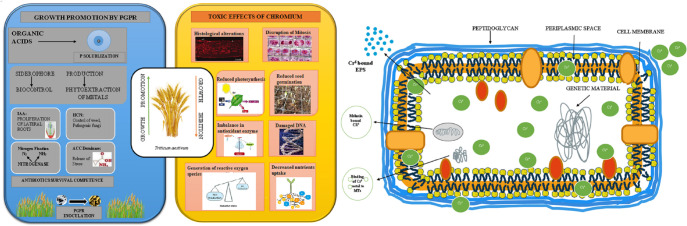

Several methods of metal remediation have been used to address the harmful impacts of metal contamination, including physical, chemical, and biological processes, to inactive specific hazardous metals from the atmosphere (Marques et al., 2011). Microbial remediation has gained significant attention among different biological remediation methods because of its cost-effectiveness, higher efficacy, and non-expendable technologies (Malaviya and Singh, 2014; Fernandez et al., 2018). Some of the microbes that tolerate Cr establish ability to minimize the toxicity of Cr(VI) concentration from the atmosphere and thus play a prominent role in the remediation of Cr(VI) ( Table 3 ; Figure 3 ). Many investigations on the collection and profiling of distinct Cr-lowering microbial strains of bacteria have been published in last few years (Pseudomonas spp., Bacillus spp., Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter spp,.), fungi (Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., Rhizopus spp.), and yeast (Candida spp., Saccharomyces spp.) (Chen et al., 2016).

Table 3.

Biosorption of chromium by application of different microbes.

| Microbial group | Microbial biosorbent | pH | Temperature (°C) | Time | Initial metal ion concentration (mg L-1) | Removal efficiency (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi |

Saccharomyces

cerevisiae |

5 | 25 | 3 h | 90 | 99.6 | Rossi et al. (2018) |

| Aspergillus sydowii | 5 | 28 | 7 d | 50 | 24.9 | Lotlikar et al. (2018) | |

| Arthrinium malaysianum | 3 | 30 | 20 h | 1000 | 67 | Majumder et al. (2018) | |

| Penicillium oxalicum SL2 | 30 | 144 h | 1000 | 100 | Long et al. (2018) | ||

| Aspergillus niger (CICC41115) | 7 | 37 | 84 h | 50 | 100 | Gu et al. (2015) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 3.5 | 25 | 24 | 200 | 85 | Mahmoud and Mohamed (2017) | |

| Aspergillus sp. FK1 | 5 | 7 d | 557 | 65 | Srivastava and Thakur (2006b) | ||

| Bacteria | Acinetobacter sp. B9 | 7 | 30 | 24 h | 7.0 | 67 | Bhattacharya and Gupta (2013) |

| Enterobacter cloacae strain CTWI-06 | 7 | 37 | 92 h | 500 | 94 | Pattnaik et al. (2020) | |

| Escherichia coli VITSUKMW3 | 7.5 | 30 | 5 h | 20 | 40 | Samuel et al. (2012) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus strain K1 | 8 | 35 | 24 | 100 | 99 | Tariq et al. (2019) | |

| Bacillus subtilus PAW3 | 6 | 35 | 20 | 100 | 100 | Wani et al. (2018) | |

|

Cellulosimicrobium

Funkei strain AR6 |

7 | 35 | 120 | 250 | 80.43 | Karthik et al. (2017) | |

| Acinetobacter sp. AB1 | 10 | 30 | 72 h | 50 | 100 | Essahale et al. (2012) | |

| Streptomyces sp. MC1 | 7.4 | 30 | 72 h | 50 | 52 | Polti et al. (2011) | |

| Bacillus subtilis MNU16 | 7 | 30 | 72 h | 50 | 75 | Upadhyay et al. (2017) | |

| Pseudomonas sp. JF122 | 6.5 | 30 | 72 h | 2.0 | 100 | Zhou and Chen (2016) | |

| Acinetobacter guillouiae SFC 500 – 1A | 10 | 28 ± 2 | 72 | 10 | ~62 | Ontañon et al. (2015) | |

| B. mycoides 2000AsB1 | 7 | 30 | 25 h | 25 | 100 | Wang et al. (2016) | |

| Streptomyces werraensis LD 22 | 7 | 41 | 7 d | 250 | 51.7 | Latha et al. (2015) | |

| Arthrobacter sp. Sphe3 | 8 | 30 | 45 | 100 | Ziagova et al. (2014) |

Figure 3.

A schematic illustrating how rhizobacteria that encourage plant growth might boost growth and reduce the damaging effects of chromium (Cr) on plant. The removal/detoxification of Cr ions by active biomolecules i.e., secretion of melanin, metallothionein (MTs), and polymeric substances (EPS), released by rhizobacteria strains under Cr stress (Rizvi et al., 2020; Ao et al., 2022).

The use of plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) in plants, is also regarded as a significant and environmentally acceptable method for the removal of heavy metals from soil (Fahad et al., 2014). These bacteria encourage plants to endure extreme stress and improve plant nutrition to stimulate plant growth (N, P, Fe) and release different metabolites related to stress, such as the production of phytohormones, solubilization of phosphates, and production of siderophores (Dodd and Perez-Alfocea, 2012). Several studies have documented the use of plant growth promotion (PGP) rhizobacteria for heavy metal bioremediation, like Bacillus sp., Pseudomonas sp., etc. (Ndeddy-Aka and Babalola, 2016). Microorganisms have been found to reduce hexavalent Cr through various means, either by using hexavalent Cr as the final acceptor of electrons or by releasing some dissolving enzymes ( Table 4 ; Ahemad, 2015). In an experiment, Karthik and Arulselvi (2017) evaluate the effect of Cr(VI) on the plant growth-promoting properties of potential rhizobacterial strain isolated from the rhizosphere of a common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). The strain AR8 was chosen from 36 rhizobacterial strains when compared to uninoculated Cr(VI) treated plants, the inoculation of Cellulosimicrobium funkei strain AR8 significantly improved the root length of test crops in both the presence and absence of Cr(VI). Strain AR8 could be used for growth stimulation as well as for the removal of Cr in Cr-contaminated soil because of these exceptional characteristics ( Figure 3 ).

Table 4.

Effects of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on plants in Cr-contaminated soils.

| Plant species | PGPR | Method of application | Amount of PGPR | Cr concentration | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indian mustard | Pseudomonas sp. PsA4, Bacillus sp. Ba 32 | Seedling inoculation | 108 cell mL-1 | 281 mg kg-1 | Increased plant growth (phytostabilization), decreased Cr content. | Rajkumar et al. (2006) |

| Chickpea | Mesorhizobium sp. RC3 | Seedling inoculation | Approx. 108 cell mL-1 | 136 mg kg-1 | The bio-inoculant decreased the assimilation of Cr by 14, 34 and 29% in roots, shoots and grain respectively. | Wani et al. (2008) |

| Sunflower | Ochrobactrum intermedium | Seedling inoculation | 300 µg mL-1 | 300 µg g-1 | Increased growth of plant and decreased Cr(VI) uptake. | Faisal and Hasnain (2005a; b) |

| Green gram | Ochrobactrum sp., and Bacillus cereus | Seedling inoculation | 300 µg mL-1 bacterial suspension | 384 µg g-1 | Cr toxicity to seedlings is lessened from Cr(VI) to Cr(III). | Faisal and Hasnain (2006) |

| Common bean | Cellulosimicrobium funkei (KM263188) | 0.024 mg kg-1 (garden soil) and 42.65 mg kg-1 (leather industrial soil) | Serial dilution (up to 10-7) | Increased crop production, showed tolerance to Cr(VI), produced plant growth-promoting substance. | Karthik and Arulselvi (2017) | |

| Alfalfa | Pseudomonas sp. | Seedling inoculation | 108 CFU mL-1 bacterial suspension | 10 mg kg-1 | Improved alfalfa growth and antioxidant system under Cr stress and enhanced Cr(VI) phytoremediation | Tirry et al. (2021) |

| Green gram |

Bacillus sp. AMP2, Halomonas sp. AST, Arthrobacter mysorens AHA, Kushneria avicenniae

AHT, Halomonas venusta APA |

Seedling inoculation | 10 to 1000 µg mL-1 | 100 µg mL-1 | Reduced the damaging effects of Cr on the environment, primarily on soil. | Arshad and Ahmed (2017) |

| Maize | T2Cr and CrP450 | Seedling inoculation | 108 CFU mL-1 bacterial suspension | Improved production potential of maize, reduced oxidative stress | Islam et al. (2016) | |

| Black gram (Vigna mungo) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC P15442 (P15) | Seed inoculation | 10 mL of NBRIP broth medium inoculated with 10% bacteria cell | 100 and 250 µg mL-1 | Reduced heavy metals, soil productivity enhanced due to PGPR. | Kumar et al. (2020a) |

| Bacillus subtilis MNU 16 | 2 x 106 bacteria/mL bacterial suspension | 50-300 mg/L | Reduced toxic form of Cr(VI) to less toxic form Cr(III), improved the efficiency of rhizoremediation of contaminated soils. | Upadhyay et al. (2017) | ||

| Common bean | Cellulosimicrobium funkei (AR6) | 1200 µg mL-1 | Inoculation of rhizobacteria in polluted soils could be a good approach for soil rehabilitation. | Karthik et al. (2017) | ||

| Maize | Agrobacterium fabrum and Leclercia adecarboxylata | Foliar application | 10 mL of inoculum was applied along 10% sugar in 100g sterilized seeds. | 50 and 100 mg kg-1 | Chlorophyll content and nutrient concentration increased and Cr toxicity decreased. | Danish et al. (2019) |

| Lentil (Lens culinaris) | Bacillus sp. | Seed inoculation | 106-107 CFU mL-1 | 500 µg mL-1 | PGPRs protected the plants from heavy metals by producing phytohormones and antioxidant enzymes. | Fatima and Ahmed (2018) |

| Wheat | Bacillus sp. | Seed inoculation | 107 CFU mL-1 | 95-1180 mg kg-1 | PGPR in combination with biochar increased root and shoot length, chlorophyll content and sugar contents, it also controlled the Cr. | Mazhar et al. (2020) |

| Mesquite trees (Prosopis laevigata) | Bacillus sp. MH778713 | Seed inoculation | 1x106 UFC suspended in 1 mL of sterile distilled water |

435 mg kg-1 | Bacillus sp. is thought to be a viable option for heavy metals-contaminated soil rehabilitation. | Ramírez et al. (2019) |

| Wheat | 180 Cr(VI) tolerant bacteria | Seed inoculation | 107-108 CFU mL-1 | 20 mg kg-1 | Cr concentration decreased with the application of PGPR. | Khan M.Y. et al. (2013) |

| Wheat | CC7 and ACC-14 | Seed inoculation | 107-108 CFU mL-1 | 0-100 mg L-1 | Phytotoxicity was reduced by using PGPR like CC7 and ACC-14. | Rai et al. (2016) |

| Bajra (Pennisetum glaucum L.) |

Bacillus sp., Pseudomonas sp., Azotobacter sp., and Rhizobium sp. | 200 µg mL-1 | 25 to 2000 µg mL-1 | Decreased the heavy metal contaminants present in the soil. | Saif and Khan (2017) | |

|

Achromobacter xylosoxidans (LK391696), and Azotobacter vinelandii

(LK391702) |

46 µg mL-1 and 30 µg mL-1 | 0.2 mg kg-1 | PGPRs reduced Cr concentration and improved plant growth. | Mohan et al. (2014) | ||

| Rice | Bacillus sp. | 10-3 to 10-7 | 50 to 100 µg | Plant growth stimulation and biocontrol work together to boost vegetative and crop yields. | Karuppiah and Rajaram (2011) | |

| Maize | PGPR LCC41, LCC81 | Seed inoculation | 108 CFU mL-1 bacterial suspension | 320 mg kg-1 | PGPRs improved plant growth, and soil microbial activity and reduced translocation of Cr within plant | Silva et al. (2021) |

According to Caravelli et al. (2008) the Sphaerotilus natans CSCr-3, a filamentous bacterium obtained from activated sludge, reduced Cr concentration up to 1.5 mM in the presence of a carbon source. This removal efficiency is significant because S. natans was originally recognized for its biosorption capability. Under alkaline medium, another bacterium, Ochrobactrum sp., was able to decrease Cr(VI). This isolate substantially tolerated and reduced Cr(VI) up to 15.4 mM. The inclusion of glucose generated a significant improvement in Cr(VI)-reduction, while the availability of sulphate or nitrate had no effect (He et al., 2009). Five Cr resistant bacterial strains with auxin biosynthesis abilities were used by Arshad and Ahmed (2017). Halomonas venusta APA and Arthrobacter mysorens AHA were determined to be the most effective isolates in terms of phytostimulatory effects on green gram (Vigna radiata). A huge proportion of microbial variants have been recorded for remediation of Cr(VI) using biosorption and bioaccumulation methods, such as Paecilomyces lilacinus (Sharma and Adholeya, 2011), Aspergillus niger (Srivastava and Thakur, 2006a, b), Bacillus cereus IST105 (Naik et al., 2012), Zobellella denitrificans (He et al., 2016), and Bacillus mycoides 200AsB1 (Wang et al., 2016). In conclusion, the use of a suitable microbial inoculum might become useful in effectively altering the soil infected with Cr.

8.3. Chemical remediation

In-situ or ex-situ complex formation through chelating substances has been used for metal extraction (Di-Palma et al., 2005; Finzgar and Lestan, 2007). The efficacy of extraction depends upon the availability of readily exchangeable ions in the soil matrix capable of forming strong complexes with minimum specific chelating agents (Di-Palma, 2009). For removal of maximum amounts of metals found in polluted soils, phytoextraction may be used, with some portion of the soil metal content freely available to plants. There are various synthetic chelating components, such as EDTA (ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid), diethylene trinitrile pentaacetic acid (DTPA), nitrile triacetic acid (NTA), pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDA), trans-l,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N0,N0-tetraacetate (CDTA), or ethylenediamine disuccinate (EDDS) used for remediation of soil polluted with organic and inorganic contaminants. To increase the accessibility of metals in soil and the transference of metals from root to shoot, several ideas have been proposed (Meers et al., 2005). Application of chelating agents substantially improved the Cr uptake in above-ground biomass of many crops ( Table 5 ). Patra et al. (2018) revealed that in Cr(VI) polluted soil, application of chelators including EDTA, DTPA, citric acid, and salicylic acid, along with metal ions, enhanced the growth of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) and enhanced Cr bioavailability. Chigbo and Batty (2013) analyzed that the application of EDTA and citric acid reduced alfalfa (Medicago sativa) shoot dry matter by 55%, decreasing the soil Cr removal efficiency. The removal of Cr increased to 54.28% when the polluted soil was pre-treated with 0.01M EDTA-2Na (Xu Y. et al., 2019). Mohanty and Patra (2012) revealed the total accumulation rate for Cr was improved with the application of DTPA to rice (Oryza sativa) and wheat (Triticum aestivum), While the use of EDDHA was proven to be useful in accelerating the process of Cr accumulation in green gram (Vigna radiata) seedlings. The role of chelating substances in reducing the harmful impact of Cr(VI) is demonstrated in this study. The chelating agents in the culture medium augmented with Cr(VI) improved the bioavailability of Cr in plants. In another study, EDTA application in Cr contaminated soil resulted in higher endogenous levels of Cr(III) in plants. Moreover, EDTA addition improved the growth by regulating Cr species, ion homeostasis and accumulation of secondary metabolites in castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) (Qureshi et al., 2020).

Table 5.

Effect of chelates application for remediation of chromium in soil.

| Plant species | Chelate applied | Concentration in biomass (mg kg-1) | (mg kg-1) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | ||||

| Rice | 25 µM EDTA | 30 | 42 | 100 | Huda et al. (2021) |

| Lemongrass | 50 mg EDTA kg-1 | 12.2 | 17.93 | 50 | Patra et al. (2018) |

| Alfalfa | 0.14 g EDTA | 2.45 | 4.10 | 50 | Chigbo and Batty (2013) |

| Barnyard grass | 10 mmol EDTA kg-1 | 79.50 | 109.23 | 79.50 | Ebrahimi (2014) |

| Common reed (Phragmites australis) | 10 mmol EDTA kg-1 | 0.002 | 125.71 | 550 | Ebrahimi (2015) |

| Chinese mustard | 2 mM EDTA kg-1 | 21 | 28 | 51.5 | Han et al. (2004) |

| Mustard | 10 mmol EDTA kg-1 | 1328 | 1411 | 169 | Firdaus-E-Bareen and Tahira (2010) |

| Downy thorn apple | 1 mmol EDTA kg-1 | 0.17 | 0.49 | 113 | Jean et al. (2008) |

| Maize | 7.5 mmol EDDS kg-1 | 0.003 | 0.019 | 151 | Meers et al. (2008) |

| Rice | 10 µM EDTA | 0.0002 | 93.64 | Mohanty and Patra (2012) | |

| Wheat | 10 µM DTPA | 0.0003 | 110.25 | Mohanty and Patra (2012) | |

| Green gram | 10 µM EDDHA | 0.07 | 52.6 | Mohanty and Patra (2012) | |

| Water spinach | 3 mg EDTA kg-1 | 400 | 7000 | 13217 | Chen et al. (2010) |

| Physic nut | 0.3 g EDTA kg-1 | 8 | 33 | 56.9 | Jamil et al. (2009) |

| Sunflower | 0.708 mM EDTA | 2.98 | 4.88 | 30 | January et al. (2008) |

| Sunflower | 0.1 g EDTA kg-1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 8.05 | Turgut et al. (2004) |

| Sunflower | 0.3 g EDTA kg-1 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 7.72 | Turgut et al. (2005) |

8.4. Remediation by nanoparticles

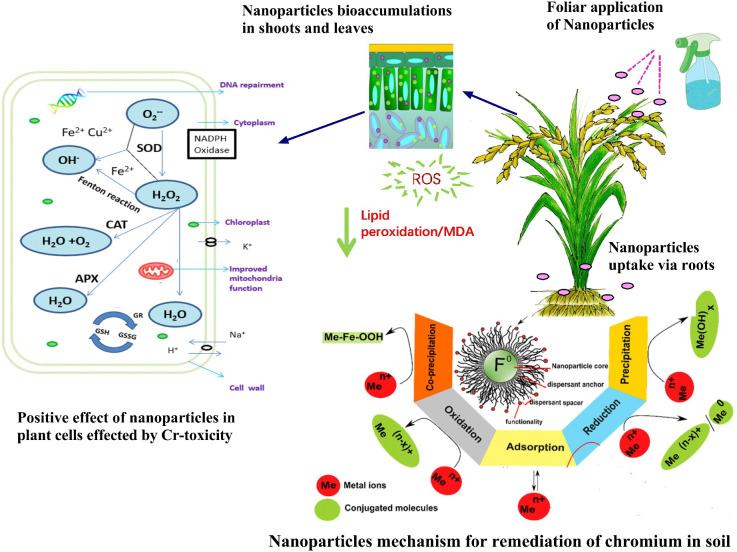

Nano-remediation is an eco-friendly and cost-effective method of detoxifying heavy metals in soil and other environments using nanoparticles (NPs) (Ahmed et al., 2021a; Wei et al., 2022a; Table 6 ). By absorbing heavy metals, lowering the hazardous valence to a stable metallic state, and accelerating the reaction, this unique remediation strategy has been demonstrated to be efficient in the removal of toxic heavy metals (Mondal et al., 2020). Synthesis of nZVI NPs in colloidal solution using green tea extract having an average particle diameter of 5-10 nm with polyphenol coating (which served as a capping and reducing agent) was significantly effective in remediating Cr(VI) from groundwater passing through porous soil beds (Mystrioti et al., 2014). Synthesis of NPs by using various rose apple (Syzgium jambos L.), candlenut tree (Aleurites moluccanus L.), and oolong-tea leaves extracts were significantly remediate Cr(VI) from aqueous medium up to 90% at initial 5 minutes, due to its maximum NPs antioxidant property, but complete removal took after 60 minutes (Xiao et al., 2016). The removal effectiveness of Cr(VI) was greatly influenced by factors i.e., Cr(VI) initial concentration, NPs dosage, solution pH, and temperature. For a constant concentration of Cr, the availability of active sites rises with increasing NPs dosage, which improves the removal rate (Xiao Z. et al., 2017). Various probable processes for effective decontamination of inorganic pollutants by NPs have already been hypothesized throughout the application, including precipitation, adsorption, complexation, and reduction (Mondal et al., 2020; Ahmed et al., 2021b). The most well-known method for eliminating Cr is called as reduction, which is followed by adsorption. According to Li and Zhang (2007), whenever the trace-metal ions already had a greater negatively standard-redox strength (E0 ) as compared to, or were like Fe0 (-0.41 V), the method for decontamination of Cr via green-synthesized iron-NPs was largely regulated by surface complexation/adsorption. However, whenever the Cr ions already had substantially higher positive E0 as compared to Fe0, precipitation and reduction of Cr ions predominate (Lin et al., 2019). When the Cr cations had somewhat more positive E0 as compared to Fe0, both reduction and adsorption happened (Ahmed et al., 2021b). Other possibilities included co-precipitation and Fe-hydroxide oxidation (Sebastian et al., 2018; Figure 4 ). In addition, bimetallic Fe-NPs and Fe-oxide remove pollutants through catalytic degradation and adsorption respectively (Ahmed et al., 2021b). However, there are significant limitations and knowledge gaps that must be addressed to ensure social acceptance and safe usage of green synthesized NPs for toxic heavy metals remediation. As a result, more field studies are required to assess the application’s safety, reliability, efficacy, fate, intrinsic toxicity of NPs, and long-term impacts of NPs on Cr bioavailability and absorption in contaminated soils. To attain its promised implications in the environmental sector, future research should focus on doze optimization and safe targeted delivery of NPs.

Table 6.

Application of nanoparticles for remediation of chromium in aqueous medium.

| Initial conc. of Cr | NP source | NP type | Reaction time | Removal efficiency % | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 mg L-1 | Eucalyptus globulus | nZVI | 30 min | 98.1% | Madhavi et al. (2013) |

| 100 mg L-1 | Citrus maxima | Fe-NPs | 90 mins | 99.29% | Wei et al. (2016) |

| 15 mg L-1 | Eucalyptus globulus leaves | nZVI | 60 mins | 58.9% Cr and 33.0% Cu | Weng et al. (2016) |

| 50 mg L-1 | Syzygium jambos, Oolong tea, Aleurites moluccana | Fe NPs | 60 min | 100% | Xiao et al. (2016) |

| 300 mg L-1 |

Rosa damascene, Thymus

vulgaris, and Urtica dioica |

Fe-NPs | 25 mins | 100% | Fazlzadeh et al. (2017) |

| 10 mg L-1 | Eucalyptus globulus leaves | nZVI | 35 mins | 98.9% | Jin et al. (2017) |

| 50 mg L-1 | Syzygium jambos leaves | nZVI | 90 mins | 99.45% | Xiao Z. et al. (2017) |

| 100 mg L-1 | Eichhornia crassipes leaves | Fe-NPs | 80 mins | 89.9% | Wei et al. (2017) |

| 100 mg L-1 | Eichhornia crassipes leaves | nZVI | 90 mins | 89.9% | Wei et al. (2017) |

| 40 g L-1 | Eucalyptus globulus | Fe-NPs | 12 hrs | 98.6%. | Jin et al. (2017) |

Figure 4.

Nanoparticles (NPs) application reduced oxidative stress in plant species. Under chromium (Cr) toxicity, cellular respiration produces O2 .- that is converted into hydrogen peroxide by the activity of superoxide (SOD). H2O2 is then converted into O2 and H2O by the combined activities of ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), glutathione reductase (GR), and glutathione peroxidase (GPX). NPs minimizes the accumulation of O2 .- and H2O2. The reactive oxygen species (ROS) which causes lipid peroxidation, enzyme inactivation, and cell death. The activity of ROS was significantly minimized by NPs due to improved production of antioxidants i.e., CAT, SOD, and POD (Ali et al., 2021). Mechanism representations i.e., precipitation, reduction, adsorption, oxidation, and coprecipitation for the decontamination of toxic trace-metals i.e., Cr in soil/aqueous medium by NPs with a core-shell structure (Yang et al., 2019).

8.5. Use of organic amendments for remediation

Organic material is facilitated in soil deposition of Cr, according to Branzini and Zubillaga (2012). We postulated that soil comprising most of the humidified organic material had a lesser Cr accessibility, which would minimize Cr deposition in plants. The use of organic modifications in Cr polluted soils and their impact on reducing Cr absorption in plants have been reported in several studies.

8.5.1. Biochar