Abstract

Background

Digital health interventions offer new methods for delivering healthcare, with the potential to innovate healthcare services. Key performance indicators play a role in the evaluation, measurement, and improvement in healthcare quality and service performance. The aim of this scoping review was to identify current knowledge and evidence surrounding the development of key performance indicators for digital health interventions.

Methods

A literature search was conducted across ten key databases: AMED – The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, CINAHL – Complete, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, MEDLINE, APA PsycINFO, EMBASE, EBM Reviews – Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EBM Reviews – Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, EBM Reviews – Health Technology Assessment, and IEEE Xplore.

Results

Five references were eligible for the review. Two were articles on original research studies of a specific digital health intervention, and two were overviews of methods for developing digital health interventions (not specific to a single digital health intervention). All the included reports discussed the involvement of stakeholders in developing key performance indicators for digital health interventions. The step of identifying and defining the key performance indicators was completed using various methodologies, but all centred on a form of stakeholder involvement. Potential options for stakeholder involvement for key performance indicator identification include the use of an elicitation framework, a factorial survey approach, or a Delphi study.

Conclusions

Few articles were identified, highlighting a significant gap in evidence-based knowledge in this domain. All the included articles discussed the involvement of stakeholders in developing key performance indicators for digital health interventions, which were performed using various methodologies. The articles acknowledged a lack of literature related to key performance indicator development for digital health interventions. To allow comparability between key performance indicator initiatives and facilitate work in the field, further research would be beneficial to develop a common methodology for key performance indicators development for digital health interventions.

Keywords: Digital health, general, behaviour change, lifestyle, Apps, personalized medicine, technology, general, pharmacology, medicine, key performance indicators

Introduction

A digital health intervention (DHIs) is defined as a ‘discrete functionality of digital technology that is applied to achieve health objectives’ (p. xi) 1 and offers new methods for delivering healthcare, with the potential to innovate healthcare services.2 Careful monitoring and evaluation of DHIs is important in the process of evidence generation for these technologies and for informing decision-makers as to whether to integrate the intervention into practice and health systems.3 DHIs vary substantially in what they offer and the mechanisms used to deliver the intervention, contributing to complexity in their evaluation.2,4

There is a growing body of literature on evaluation frameworks to appraise DHIs 5 within which key performance indicator (KPI) development is often referred to,6 however, there is limited guidance on how such KPIs are developed. The aim of this review is to identify current knowledge and evidence surrounding the development of KPIs for DHIs; to the best of our knowledge, no systematic or scoping review has been published on this issue.

KPIs play a role in the evaluation, measurement, and improvement of healthcare quality and service performance.7,8 The World Health Organization (p.144) defines an indicator as “a quantitative or qualitative factor or variable that provides a simple and reliable means to measure achievement, to reflect the changes connected to an intervention or to help assess the performance of a development actor”.9 KPIs alone do not improve quality, however, they can act as alerts and metrics, allow comparisons between similar services, and contribute to high quality and safe services that meet the needs of the end-users.7

Effective KPIs must be clearly defined to be reliable and valid.7 The SMART criteria for indicators suggest they should be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound.3 however, there is a lack of appropriate guidance in selecting and developing SMART indicators.

This scoping review is part of our work within an €18.5 m, a 5-year partnership programme of research (Gravitate Health) funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative, the EU Commission and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries. This project aims to provide technology (a G-lens) for personalized content delivery (e.g., medication contraindications for patients with polypharmacy) to patients across the lifespan.

Methods

Scoping reviews are beneficial for exploratory topics where there is uncertainty about the breadth of the literature that will be identified.10 Such reviews can be used to further inform research questions for systematic reviews and other research. The review took place between May 2021 and August 2021 and was informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) scoping review extension checklist, thereby ensuring methodological rigour and reporting of key elements of a scoping review according to accepted standards.11 A protocol outlining the rationale, inclusion/exclusion criteria and data extraction was written a priori. The search strategy was guided by Arksey and O’Malley 12 search methodology, which involved five steps: (a) Identifying the research question; (b) identifying relevant studies; (c) study selection; (d) charting the data; (e) collating, summarizing, and reporting results.

Identifying the review question

The review question was developed following an initial search to identify literature to assist in the development of KPIs for an ongoing DHI initiative. This initiative aims to provide individual patients with access to trusted health information which is tailored and relevant to their specific needs. A key task in this project was to develop and select candidate KPIs to measure the success of the integrated DHI approach.

A protocol for the scoping review was developed and reviewed by members of the Gravitate task team (MB, AW, CM, CD, MH, MM). At an initial meeting, the review question and inclusion/exclusion criteria were clarified. A further meeting was then held to develop the literature search strategy, which was developed in collaboration with an experienced librarian [Supplemental file].

Identifying relevant studies

A rigorous literature search was conducted across ten key databases: AMED – The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, CINAHL – Complete, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, MEDLINE, APA PsycINFO, EMBASE, EBM Reviews – Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EBM Reviews – Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, EBM Reviews – Health Technology Assessment, and IEEE Xplore. The keywords and syntax were developed in the EBSCOHost platform and adapted to the other databases. Hand-searching of the literature was conducted from the references of included articles. The Grey literature was also searched in appropriate organization sites including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Health Information and Quality Authority, Health Standards, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Only English language literature was included. There were no restrictions based on publication status or year. Articles collected from the literature search were imported into Mendeley for deduplication, and then into Covidence 13 for screening.

Study selection

The eligibility criteria were designed according to the Joanna Briggs manual of scoping review methodology, consisting of Population, Concept, Context, and Study Design14 and are defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of eligibility criteria.

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | The population of interest was research teams or organizations developing KPIs for a DHI. |

| Concept | The concept of interest was the development of KPIs for a DHI and how they were identified, defined, and established. |

| Context | The context was KPIs for a DHI. Specifically, we included computer and mobile interventions. This included remote and Web 2.0-based interventions delivered via technologies that give patients access to eHealth. These technologies included personal computers and applications for mobile technology such as iPad, Android tablets, smart phones, and Skype. |

| We excluded studies that focused on monitoring devices such as telemonitoring/ telehealth or assistive technologies, as these studies involved the participation of more than one user, for example, the patient and the healthcare professional. | |

| Study Design | Study design for inclusion were review articles, editorials, guidelines, quantitative research designs, qualitative research designs, and the grey literature. |

| Settings | There were no restrictions based on study settings. |

| Language | Only English language studies were included. |

| Year | There were no restrictions based on year of publication. |

| Publication Status | There were no restrictions based on publication status. |

DHI: digital health intervention; KPI: key performance indicator.

Screening was conducted at both the title/abstract level and full-text level. At the onset of the screening, a meeting was held in which five random references were each screened by all reviewers to clarify the screening selection. Following this initial pilot of screening, reviewers working in pairs independently screened all studies at each level (AW, CM, MB, MH, CD, MM). Uncertainties were resolved by discussion at weekly meetings and in consultation with all team members. Results of the screening process are displayed in a PRISMA flow diagram with explanations for full-text exclusions.

Charting the data

A data extraction form was created in Excel to simplify the data collection process and to ensure that all relevant data was collected [Multimedia Appendix 2]. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and verified by a second independent reviewer (AW, CM, MB, MH, CD, MM).

Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

Within this project, our team was tasked with refining and selecting candidate KPIs to measure the success of this integrated digital health information. This review was a key aspect of this process in terms of sourcing and assessing relevant existing evidence related to this topic. A descriptive summary of the literature was performed, and thematic analysis using Braun and Clarke's (2006) framework. Each member of the review team read the included articles and identified recurring patterns in the data. Each pattern was coded independently and then compared for consensus. Reviewers (AW and MB) then categorized the codes and organized them into themes.

Results

Search results

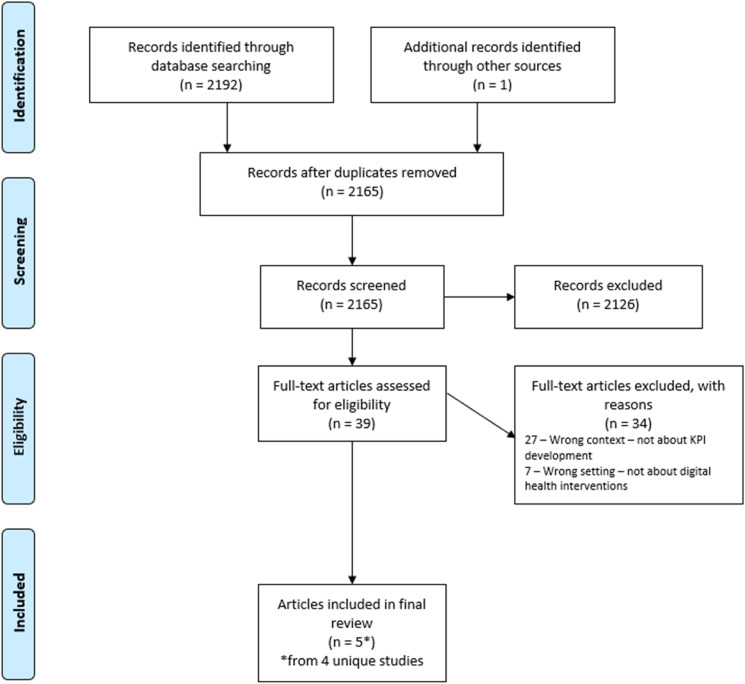

During the initial search, it became clear that there was limited literature on how to develop specific and measurable KPIs that evaluate DHIs. Broad generalist literature exists on components that should be measured as KPIs, however there is a paucity of guidance to operationalize the development of the KPIs. We retrieved 2192 articles and identified one further article from hand-searching references of the included studies. Following deduplication, 2165 references were screened at the title/abstract level, then 39 references were screened at the full-text level to determine if any relevant passages were included that would describe the identification or development of KPIs for DHIs. We excluded articles that described KPIs and/or metrics without discussing how the KPIs were identified or developed. This process resulted in the exclusion of a further 34 references, leaving five references (representing four unique publications) eligible for the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Characteristics of included references

Characteristics of the included literature are displayed in Table 1. Publication dates ranged from 2012 to 2018. Of the four included publications, two were articles on original research studies of a specific DHI,15,16 and two were overviews of methods for developing DHIs (not specific to a single DHI).17,18 The primary geographic region of the DHI or publication (dependent on whether the article was related to a specific DHI or an overview of DHI methodology) was Europe which accounted for three articles,16–18 and Colombia 15 for one article. Key issues to emerge from the scoping review are stakeholder involvement, methodology used to identify and develop KPIs and overall a dearth of evidence on the development of KPIs for DHI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included articles.

| Author, Year | Primary geographic region | Aim of the DHI | DHI development team composition | Methods to identify KPI's |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyppönen, 201218 | Europe | n/a – general report on DHIs |

|

|

| Carrion, 201619 | Europe | n/a – general report on DHIs |

|

Not included – describes DHI assessment based on principles of technical readiness and maturity, risks, benefits, and resources needed |

| Bradway, 201717 |

|

|||

| Vedluga, 201716 | Europe (Lithuania) | Lithuania's national eHealth information system |

|

|

| Farinango, 201815 | Columbia | Personal health record systems for the management of metabolic syndrome according to the principles and recommendations of the ISO 9241-210 standard |

|

|

*Of the DHI or publication (dependent on whether the article was related to a specific DHI or an overview of DHI methodology). DHI: digital health intervention; IMIA: International Medical Informatics Association; EFMI: European Federation for Medical Informatics; ISO: International Organization for Standardization; n/a: not applicable; KPI: key performance indicator.

Identifying and defining KPIs

The literature described a process of steps to identify and define KPIs, which included: identifying stakeholders and their needs, defining the goal of the DHI, identifying and defining the KPIs, and defining the data to evaluate the KPIs.15,18 All the included reports discussed the involvement of stakeholders in developing KPIs for DHIs.15–18 The step of identifying and defining the KPIs was completed using various methodologies, but all centred on a form of stakeholder involvement.

The importance of diversity of stakeholders was evident with several groups of stakeholders identified, for example the health sector and media (Vedluga 2017) 16; patient and/or patient representative organizations, DHI developers, government agencies and insurance agencies. (Bradway 2017).17 Farinango (2018) described their process for KPI development as first completing interviews with individual stakeholders, followed by an interdisciplinary brainstorming session.15 Vedluga16 suggested the use of instruments to identify stakeholders and their needs. These instruments, including the Activity Pyramid, Kane's Model Affinity Diagrams, and critical quality requirements tree, emphasize the importance of stakeholder input for DHI measurement systems, as stakeholder acceptance was noted as crucial for the acceptability of the DHI.

Hyppönen18 specifically referred to their methodology for KPI development as first conducting a literature review on indicator methodology (not specific to DHIs), followed by an expert meeting to classify the identified indicators. While not specifically referring to the context of DHIs, this article identified two main approaches for defining indicators for KPIs. These approaches included an expert-led top-down method, and a community-led bottom-up method, which were noted as being more prominently applied when assessing policies and impact at the level of society, and at the local environment level, respectively. Hyppönen18 also stated that the KPIs are often chosen using expert knowledge, peer-reviewed literature, or previous work focusing on existing indicators. This article specifically suggested the use of a Delphi study, which includes combining scientific evidence and expert opinion through a consensus technique. Similarly, Bradway (2017) does not refer specifically to the development of KPI's but describes 4 pillars for DHI assessment technical readiness and maturity, risks, benefits, and resources needed.19

Lack of literature

Most of the included articles recognized the lack of literature relating to KPI development for DHIs, compared to the breadth of literature available on the development of KPIs in other fields like health or informatics.15–18 It was noted that most prior initiatives for DHI evaluation attempted to adapt health assessment frameworks to DHIs. These initiatives focused primarily on just the usability and clinical outcomes of the interventions,16,17 however new initiatives should be created with the unique properties of DHIs in mind.17 While Hyppönen (2012) did suggest phases for KPI development, it was acknowledged that these were only a preliminary step in transparent indicator development methodology.18 It was argued that there was a need to develop a common methodology for KPI development for DHIs.17,18 New initiatives for the development of KPIs for DHIs should involve the participation of all stakeholders, including regulation and legislation bodies, and be sufficiently flexible to take into account local context.16,17 The KPIs need to be clearly defined and measurable.16

Discussion

This scoping review highlights key components of KPI development for DHIs, with a clear emphasis on the importance of stakeholder involvement, though it is not clear from the papers reviewed exactly what stakeholders should be involved from the groups mentioned. The review also identifies a significant gap in evidence-based knowledge in this domain. This is surprising given the extensive proliferation and diverse range of healthcare-related DHIs that are continuously being introduced. In addition, the useability of many DHIs is short lived due to the extensive roll out of DHIs without accompanying evaluation of their impact on health outcomes or systems.1,20–22

It is also possible that, while industry recognizes the importance of multidisciplinary partners in the development of DHIs, there is a need for greater partnership with academia to highlight the rigour required in the development of KPIs for DHIs and for this to be disseminated. The absence of publications in this area may reflect the traditional industry-academic partnerships which have focused on Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM), supported by national and university policies encouraging these alliances. The expansion of partnerships beyond STEM, while growing, does not always enjoy the same level of support. This may mean that in-depth qualitative data may be viewed as more of a background necessity than an important academic endeavour that requires methodological expertise. There is a need for a focused widening of engagement with industry and government from third-level institutions, in that third-level institutions themselves need to be more supportive of the various academic expertise they hold beyond traditional philosophical alliances. Deliberate appreciation of the rigour of qualitative enquiry and seeking alternative approaches and methodological disruptors is essential to the development of person-centred and innovative DHIs.

A further challenge in the identification of KPIs is choosing the most appropriate tool for gaining consensus on what should be included in a final list of indicators. While much is written in the literature on consensus development in healthcare this usually refers to an easily defined group of patients and clinicians, often related to a specific discipline of care. The development of KPIs for DHIs includes a much larger stakeholder group and so the challenge of consensus becomes more complex. One potential option is using an elicitation framework. For example, in the Sheffield Elicitation Framework,23 participants would be presented with factors derived from the literature and interviews and be asked to identify their plausible limits regarding each of the potential factors they identify as the most relevant KPIs for inclusion. This would result in the construction of a probability distribution for each participant and through inward skilled facilitation, a consensus of their overall preferred KPIs for inclusion would be identified.

An alternative is the use of a factorial survey approach. This comprises a hybrid technique that incorporates the use of vignettes that are based on specific testing scenarios with interchangeable, multiple factors. This methodology produces effects that cannot be identified from individually exploring the relationship between the dependent variable (e.g., drug adherence) and each independent variable (e.g., age, gender and/or health literacy) using the concept of orthogonality from the experimental tradition.24,25 This acknowledges that multiple factors may be responsible for influencing any action taken and that ‘human evaluations are in part socially determined (that is, shared with others) and in part governed by individuality, the mix varying from topic to topic’.26 While this approach has the capacity for exploring multiple variables at various levels, it is dependent on first having a limited and strong evidence-based list of KPIs. Alternatively, a Delphi study could be used to reach a consensus on priority KPIs for use in the development of a DHI. A Delphi study could be useful as it can accommodate a large number of options and is widely used involving multidisciplinary and international panel of experts, and offers anonymity to participants and is cost-effective.24

This review suggests 3 key actions are required to ensure consistency around KPI development. These are, validation of KPI's through accompanying evaluation of their impact on health outcomes or systems; the expansion of industry-academic collaboration in rigorous approaches to developing person-centred and innovative DHIs and the use of standardized frameworks for developing consensus among key stakeholders;

Limitations

Limitations in search strategy must be noted. The review limited included studies to English language only. Additionally, as this review aimed to identify KPIs for the broad field of DHIs, literature for KPI development in specific areas of DHIs may have been missed in the search strategy. Furthermore, data extraction was performed by one reviewer however the data was verified by a second independent reviewer.

Conclusions

This scoping review aimed to identify the current knowledge and evidence for the development of KPIs for DHI. Only five references (representing four unique studies) were eligible for the review. All the included articles discussed the involvement of stakeholders in developing KPIs for DHIs, which was performed using various methodologies. Potential options for stakeholder involvement in KPI identification include the use of an elicitation framework, a factorial survey approach, or a Delphi study. As previously stated, this review was performed as a part of our work within Gravitate Health. Few articles were identified, highlighting a significant gap in evidence-based knowledge in this domain. The articles in the review included primarily the authors’ personal experiences and lessons learned from their research, and little empirical data was identified in the literature. The articles acknowledged a lack of literature related to KPI development for DHIs. To allow comparability between KPI initiatives and facilitate work in the field, further research would be beneficial to develop a common methodology for KPI development for DHIs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231152160 for Development of the key performance indicators for digital health interventions: A scoping review by Maria Brenner, Arielle Weir, Margaret McCann, Carmel Doyle, Mary Hughes, Anne Moen, Martin Ingvar, Koen Nauwelaerts, Eva Turk and Catherine McCabe in Digital Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076231152160 for Development of the key performance indicators for digital health interventions: A scoping review by Maria Brenner, Arielle Weir, Margaret McCann, Carmel Doyle, Mary Hughes, Anne Moen, Martin Ingvar, Koen Nauwelaerts, Eva Turk and Catherine McCabe in Digital Health

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Jessica Eustace-Cook (Research Support Librarian) for her expertise and guidance with developing the search strategy.

Footnotes

Contributorship: MB, AW, CMcC searched literature and conceived the work. MB, AW, CMcC, MMcC, CD, MH were involved in protocol development, and reviewing titles/abstracts/full texts. MB, AW and CMcC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) – a joint undertaking of the European Commission, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA), IMI2 Associated Partners (Grant Agreement No 945334).

ORCID iDs: Maria Brenner https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8779-5288

Margaret McCann https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7925-6396

Catherine McCabe https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0597-8580

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO guideline: Recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening, 2019. [PubMed]

- 2.European Union. Assessing the Impact of Digital Transformation of Health Services: Report of the Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (EXPH). 2019.

- 3.World Health Organization. Monitoring and evaluating digital health interventions: A practical guide to conducting research and assessment 2016.

- 4.World Health Organization. Classification of digital health interventions v1.0. 2018.

- 5.Murray E, Hekler EB, Andersson G, et al. Evaluating digital health interventions: key questions and approaches. Am J Prev Med 2016; 51: 843–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karpathakis K, Libow G, Potts HWW, et al. An evaluation service for digital public health interventions: user-centered design approach. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e28356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Information and Quality Authority. Guidance on developing key performance indicators and minimum data sets to monitor healthcare quality. Dublin, 2013. Version 1.1.

- 8.Health Information and Quality Authority. National Standards for Better Safer Healthcare. Dublin, 2012.

- 9.World Health Organization. Evaluation practice handbook. 2013.

- 10.Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev 2012; 1: 1–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tricco A, Straus S, Moher D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Extension for scoping reviews (prisma-scr). The EQUATOR Network, 2015.

- 12.Arksey H, Malley LO. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covidence. Covidence. 2015: Victoria, Australia.

- 14.The Joanna Briggs, I. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 edition / Supplement. 2015.

- 15.Farinango CD, Benavides J, Cerón Jet al. et al. Human-centered design of a personal health record system for metabolic syndrome management based on the ISO 9241-210:2010 standard. J Multidiscip Healthc 2018; 11: 21–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vedluga T, Mikulskiene B. Stakeholder driven indicators for eHealth performance management. Eval Program Plann 2017; 63: 82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradway M, Carrion C, Vallespin Bet al. Mhealth assessment: conceptualization of a global framework. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017; 5: e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyppönen H, Ammenwerth E, de Keizer N. Exploring a methodology for eHealth indicator development. Stud Health Technol Inform 2012: 180: 338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrion C, Bradway M, Vallespin Bet al. et al. mHealth Assessment: conceptualization of a global framework. Int J Integr Care 2016; 16: S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo C, Ashrafian H, Ghafur Set al. et al. Challenges for the evaluation of digital health solutions-A call for innovative evidence generation approaches. NPJ Digit Med 2020; 3: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolasa K, Kozinski G. How to Value Digital Health Interventions? A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomlinson M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swartz Let al. et al. Scaling up mHealth: where is the evidence? PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris DE, Oakley JE, Crowe JA. A web-based tool for eliciting probability distributions from experts. Environ Model Softw 2014; 52: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen J, Brenner M, Hauer Jet al. et al. Severe neurological impairment: a delphi consensus-based definition. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2020; 29: 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dülmer H. The factorial survey. Sociol Methods Res 2015; 45: 304–347. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi PH, Anderson AB. The factorial survey approach: An introduction. 1982: Measuring social judgments: The factorial survey approach.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231152160 for Development of the key performance indicators for digital health interventions: A scoping review by Maria Brenner, Arielle Weir, Margaret McCann, Carmel Doyle, Mary Hughes, Anne Moen, Martin Ingvar, Koen Nauwelaerts, Eva Turk and Catherine McCabe in Digital Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076231152160 for Development of the key performance indicators for digital health interventions: A scoping review by Maria Brenner, Arielle Weir, Margaret McCann, Carmel Doyle, Mary Hughes, Anne Moen, Martin Ingvar, Koen Nauwelaerts, Eva Turk and Catherine McCabe in Digital Health