Abstract

Recent studies have shown that immunocompetent cells bear receptors of neuropeptides and neurotransmitters and that these ligands play roles in the immune response. In this study, the role of the sympathetic nervous system in host resistance against Listeria monocytogenes infection was investigated in mice pretreated with 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), which destroys sympathetic nerve termini. The norepinephrine contents of the plasma and spleens were significantly lower in 6-OHDA-treated mice than in vehicle-treated mice. The 50% lethal dose of L. monocytogenes was about 20 times higher for 6-OHDA-treated mice than for vehicle-treated mice. Chemical sympathectomy by 6-OHDA upregulated interleukin-12 (IL-12) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) production in enriched dendritic cell cultures and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and TNF-α production in spleen cell cultures, whereas chemical sympathectomy had no apparent effect on phagocytic activities, listericidal activities, and nitric oxide production in peritoneal exudate cells and splenic macrophages. Augmentation of host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection by 6-OHDA was abrogated in IFN-γ−/− or TNF-α−/− mice, suggesting that upregulation of IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF-α production may be involved in 6-OHDA-mediated augmentation of antilisterial resistance. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of spleen cells immune to L. monocytogenes from 6-OHDA-treated mice resulted in untreated naive recipients that had a high level of resistance against L. monocytogenes infection. These results suggest that the sympathetic nervous system may modulate host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection through regulation of production of IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF-α, which are critical in antilisterial resistance.

The nervous system and the immune system play important roles in the maintenance of homeostasis. Functional interactions between these two systems through humoral factors have been described previously (9, 44). For example, lymphoid organs contain a rich supply of sympathetic nerve fibers (11), and norepinephrine (NE) is synthesized and stored in the nerve termini (36, 51). Once released, NE can stimulate either α-adrenergic or β-adrenergic receptors on effector cells. Adrenergic receptors are reportedly found on lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and natural killer cells (2, 11, 20). Recent studies demonstrated that T-helper 1 (Th1) clones and newly generated Th1 cells, but not Th2 clones or newly generated Th2 cells, express a β2-adrenergic receptor (35, 41). Reciprocal regulation of NE and immune responses, including cytokine production, has been reported. It has been shown that cytokines produced by macrophages and lymphocytes, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-2, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), can inhibit NE release from presynaptic varicosities (3, 40, 43). Conversely, NE reportedly inhibits production of cytokines, including IL-6, IL-10, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and TNF-α (7, 49), and prevents Th1 differentiation through selective suppression of IL-12 production (31). However, a recent study indicated that NE promotes IL-12-mediated differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th1 effector cells, as well as IFN-γ production by Th1 cells (22, 45).

In previous studies to determine the role of the sympathetic nervous system in modulating immune responses in vivo, peripheral nerve terminals containing NE were reversibly destroyed in animals by chemical sympathectomy with the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) before exposure to antigen. Experimental model systems in which 6-OHDA-treated animals have been used have yielded conflicting data for both cell-mediated immunity and antibody production; some studies have shown that primary and secondary cytolytic T-lymphocyte responses to herpes simplex virus (25), delayed hypersensitivity to 2,4,6-trinitrochlorobenzene (27), and proliferation of T and B cells (28) are reduced by 6-OHDA treatment, while other studies have demonstrated that the severity of Th1-driven experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (6) and the severity of experimental rheumatoid arthritis (10) are enhanced by chemical sympathectomy and that lymphocyte proliferation is increased by such treatment (26). Moreover, 6-OHDA treatment has both increased (24) and decreased (21) the level of antibody production.

Host resistance against Listeria monocytogenes, a facultative intracellular pathogen, is controlled by cell-mediated immunity and is regulated by endogenous cytokines. IFN-γ (4, 19), TNF-α (16, 30, 34, 38), IL-1 (17), and IL-6 (23) reportedly play important roles in antilisterial resistance. Moreover, IL-12 is essential for differentiation of naive T cells into Th1 cells, which are dominantly induced in L. monocytogenes infections (18). Recently, Alaniz et al. (1) reported that in mice which lack dopamine β-hydroxylase and which cannot produce NE and epinephrine, host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection is impaired. Our approach was to examine the effect of removal of the sympathetic nervous system input on host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection because denervation or exposure of a neurotransmitter such as NE may influence cytokine production, which regulates antilisterial resistance. We investigated the effect of 6-OHDA treatment on host resistance and cytokine responses in L. monocytogenes infection.

In this study, we demonstrated that blockage of the sympathetic nervous system input upregulates antilisterial resistance and that adaptive immunity might be enhanced by 6-OHDA treatment through upregulation of production of cytokines, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Six- to eight-week-old C57BL/6 female mice were purchased from Clear Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan. Age- and sex-matched IFN-γ−/− mice on a C57BL/6 × Sv129 (48) and TNF-α−/− mice on a C57BL/6 × Sv129 (49) were also used in some experiments. The mice were housed singly in small plastic cages under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the Institute for Animal Experiments, Hirosaki University School of Medicine. They were kept on a cycle consisting of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness; the lights were turned on at 8:00 a.m. and off at 8:00 p.m. All experimental manipulations were carried out during the light portion of the cycle, generally between 9:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. The mice were allowed to acclimate to laboratory conditions for at least 2 weeks before experimental manipulation, and food and water were available at all times. This study was carried out in accordance with the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation of Hirosaki University.

6-OHDA treatment.

6-OHDA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was dissolved in sterile saline containing 0.01% l-ascorbic acid (Wako Pure Chemical Co., Osaka, Japan) as an antioxidant and was injected intraperitoneally at a concentration of 250 mg/kg (24). Desipramine HCl (Sigma) was dissolved in a small volume of sterile water and then diluted with sterile saline. Desipramine was injected intraperitoneally at a concentration of 10 mg/kg 2 days before infection (24).

Tissue sample preparation for high-performance liquid chromatography.

Spleen homogenates (10%, wt/vol) in 0.1 M HClO4 were prepared with a Dounce tissue grinder (Iwaki Glass, Tokyo, Japan) and then centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Two hundred microliters of each sample was added to 1 ml of sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.1) to which 50 mg of acid-washed alumina was added. One milliliter of 1.5 M Tris–EDTA (pH 8.6) was then added. The alumina was washed twice with distilled water and placed into an extraction chamber suspended over a centrifuge tube, and the distilled water was removed by centrifugation. The NE was then extracted by adding 200 μl of 0.1 M HClO4 to the alumina, vortexing, and then centrifuging the extraction medium into a new tube. Analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography was performed as described previously (12).

Bacteria.

L. monocytogenes 1b 1684 cells were prepared as described previously (31). The concentration of washed cells was adjusted spectrophotometrically at 550 nm, and the cells were stored at −80°C until they were used. In most experiments, mice were infected intravenously with 0.1 50% lethal dose (LD50) of viable L. monocytogenes cells in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). The LD50 of L. monocytogenes for the different groups were as follows: C57BL/6 mice, 5 × 105 CFU; IFN-γ−/− mice, 1 × 104 CFU; TNF-α−/− mice, 1 × 103 CFU; and 6-OHDA-treated mice, 5 × 107 CFU. Heat-killed L. monocytogenes HK-LM cells were obtained by heating the cells in a boiling water bath for 1 h.

In vivo elimination of T-cell subsets.

Hybridoma cell lines GK1.5 (anti-CD4; rat immuoglobulin G2b) and 53-6.72 (anti-CD8; rat immunoglobulin G2a) were used. The monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) in the ascites fluid were partially purified by (NH4)2SO4 precipitation. Mice were each given a single intravenous injection of 400 μg of an MAb 1 day before L. monocytogenes infection (32). Normal rat globulin was injected as a control for the MAbs. We confirmed that more than 95% of CD4+ cells or CD8+ cells were eliminated in the spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes of mice 24 h after injection of 400 μg of the corresponding MAb by using flow cytometry, as reported previously (32).

Adoptive transfer of spleen cells.

Mice were infected with 0.1 LD50 of L. monocytogenes on day 2 after injection of 6-OHDA or the vehicle (sterile saline containing l-ascorbic acid). Spleens were removed aseptically from mice on day 7 after infection, and splenocytes were obtained by squeezing the organs in RPMI 1640 medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Each cell suspension was filtered through stainless steel mesh (size 100). After lysis of erythrocytes, the cells were washed three times and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium. Mice were each injected intravenously with 0.2 ml of a solution containing 5 × 107 spleen cells. One day later, the mice were infected with L. monocytogenes.

Determination of numbers of viable L. monocytogenes cells in the organs.

The spleens and livers were aseptically removed from mice and suspended in PBS or 1% (wt/vol) 3-([cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfate (CHAPS) (Wako Pure Chemical Co.), and 10% (wt/vol) homogenates were prepared with a Dounce tissue grinder. The numbers of viable L. monocytogenes cells in the spleens and livers were established by plating serial 10-fold dilutions in PBS on tryptic soy agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Colonies were routinely counted 18 to 24 h later.

Spleen cell cultures.

Spleen cells prepared as described above were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U of penicillin G per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml and then placed in a 24-well tissue culture plate (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) at a density of 106 cells/well in the presence of 107 HK-LM cells per well or 1 μg of hamster anti-CD3-ɛ MAb 145-2C11 per well. After 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, the supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until the cytokine assays were performed.

Preparation of enriched DC.

Dendritic cells (DC) were enriched from spleens as described previously (39). Briefly, spleens were cut into small pieces and digested in 5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium–10% FCS containing 10 U of collagenase D (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) per ml for 60 min at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After addition of 500 μl of 1 mM EDTA in PBS, the cells were filtered through stainless steel mesh to remove the solid tissue and centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The washed cells were resuspended in 3 ml of a 17% Optiprep (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway) solution diluted with Hanks' balanced salt solution, overlaid with 7 ml of 12% Optiprep (1.068 g/ml) and then with 3 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution, and centrifuged at 600 × g for 15 min at 20°C. The low-density cells at the interface between Hanks' balanced salt solution and 12% Optiprep were harvested and washed three times. These cells were then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-CD11c MAb (PharMingen, San Francisco, Calif.) and analyzed with a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). More than 55% of the enriched cells expressed CD11c. Enriched DC suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS were placed in 96-well plates at a density of 105 cells/well in a final volume of 100 μl. Then 106 HK-LM cells per well were added to each well. After 24 h of incubation, the supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until the cytokine assays were performed.

Phagocytic and bactericidal assays.

The phagocytic and listericidal activities of peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) and splenic macrophages were determined by the method described previously (30). Splenic macrophages were prepared by adhering spleen cells twice in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS in a petri dish for 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. To obtain PEC, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 2.5 ml of 10% proteose peptone (Difco) 2 days after vehicle or 6-OHDA treatment. Five days later, the peritoneal cavities were lavaged with RPMI 1640 medium, and PEC were washed with RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% FCS three times. Splenic macrophages and PEC, which were resuspended in antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fresh homologous serum at a concentration of 106 cells/ml, were mixed with 107 CFU of viable L. monocytogenes and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a 5% CO2 incubator. Then they were washed three times with RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5 μg of gentamicin per ml to kill extracellular bacteria. The cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fresh homologous serum and 5 μg of gentamicin per ml and were transferred into a 96-well flat-bottom microplate at a density of 106 cells in 100 μl per well (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). The infected cells were lysed by treatment with RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% (wt/vol) CHAPS at zero time and 2, 4, and 6 h later. Lysates from three wells were pooled, and the number of viable intracellular bacteria in each specimen was determined by culturing on tryptic soy agar.

Cytokine assays.

Titers of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-12p70 in the culture supernatants and organ extracts were determined by double-sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays as described previously (31). Organ extracts were prepared by centrifuging 10% (wt/vol) spleen and liver homogenates in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% (wt/vol) CHAPS at 2,000 × g for 20 min.

Measurement of nitrite concentration in culture supernatant.

The nitrite concentration in a culture supernatant was assayed in a 96-well flat-bottom microplate by mixing 100 μl of the culture supernatant with 100 μl of Griess reagent (13). The A550 was measured 10 min later, and the concentration was determined by referring to a standard curve for 1 to 35 μM sodium nitrate.

Statistical evaluation of the data.

Data were expressed as means ± standard deviations, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to determine the significance of the differences in bacterial counts in the organs and in cytokine titers between control and experimental groups.

RESULTS

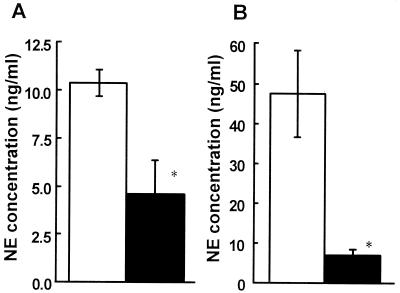

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on plasma and splenic NE content.

The extent of denervation was verified by measuring plasma and splenic NE concentrations (Fig. 1). A single intraperitoneal injection of 250 mg of 6-OHDA per kg resulted in significant decreases in plasma and splenic NE concentrations on day 2 after injection (P < 0.05). The significant decrease in splenic NE contents continued at least until day 8 after injection (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on plasma and splenic NE contents. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 6-OHDA (solid bars) or the vehicle (open bars), and then blood and spleens were removed 48 h later. The NE concentrations in plasma (A) and spleen homogenates (B) were measured. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on three mice. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the value obtained for the vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.05). The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

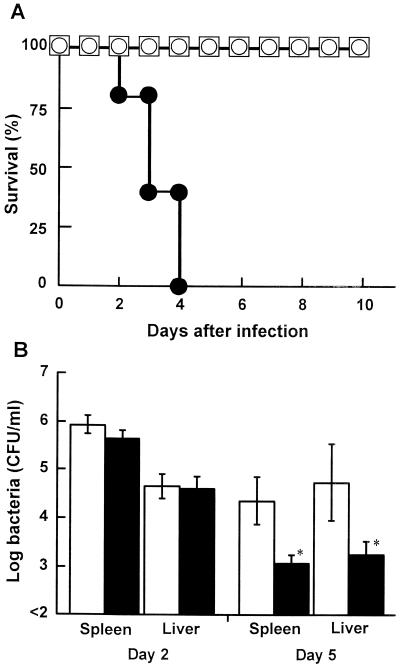

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection.

Mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 105, 5 × 106, or 5 × 107 CFU of L. monocytogenes on day 2 after injection with 6-OHDA or the vehicle, and the survival of each group was observed for 10 days (Fig. 2A). Fifty percent of the mice infected with 5 × 105 CFU of L. monocytogenes in the vehicle-treated group died (data not shown). All of the mice infected with 5 × 107 CFU of L. monocytogenes died within 4 days, in the 6-OHDA-treated group, whereas the mice infected with 5 × 105 or 5 × 106 CFU of L. monocytogenes survived. The LD50 of L. monocytogenes for 6-OHDA-treated mice was about 20-fold higher than that for vehicle-treated mice. To confirm the effect of 6-OHDA treatment on bacterial growth in the organs, the numbers of bacterial cells in the spleens and livers of 6-OHDA-treated mice and vehicle-treated mice were determined on days 2 and 5 postinfection (Fig. 2B). The number of bacteria in the organs of 6-OHDA-treated mice were comparable to those in the organs of vehicle-treated mice on day 2 after infection, whereas bacterial growth in the spleens and livers of 6-OHDA-treated mice was significantly inhibited on day 5 after infection (P < 0.05).

FIG. 2.

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on host resistance against L. monocytogenes. (A) Mice were injected with 6-OHDA and were infected with 5 × 105 (□), 5 × 106 (○), or 5 × 107 (●) CFU of L. monocytogenes 48 h later, and the levels of survival were determined for each group of five mice. (B) Mice were injected with 6-OHDA (solid bars) or the vehicle (open bars) and were infected with 5 × 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes 48 h later. The numbers of bacteria in the livers and spleens were determined on days 2 and 5 after infection. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on three mice. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the value obtained for the vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.05). The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

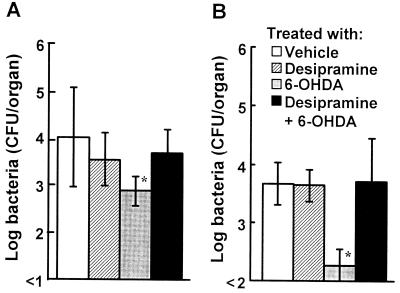

Abrogation of the effect of 6-OHDA treatment on host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection by desipramine.

To investigate whether the effect of 6-OHDA is drug specific, mice were injected with desipramine, which blocks the uptake of 6-OHDA into nerve fibers (24), before 6-OHDA injection. The numbers of L. monocytogenes CFU in the spleens and livers were determined on day 4 postinfection (Fig. 3). The number of bacterial cells in the organs of 6-OHDA-treated mice was significantly less than the number of bacterial cells in the organs of vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.01), whereas bacterial growth was observed in the organs of 6-OHDA-treated mice when they had been treated with desipramine. Injection of desipramine alone had no effect on the number of bacteria.

FIG. 3.

Abrogation of the effect of 6-OHDA by desipramine. Mice were injected with desipramine 30 min before 6-OHDA treatment and were infected with 5 × 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes 48 h later. The numbers of bacteria in the spleens (A) and livers (B) were determined on day 4 after infection. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on three mice. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the value obtained for the vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.05). The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

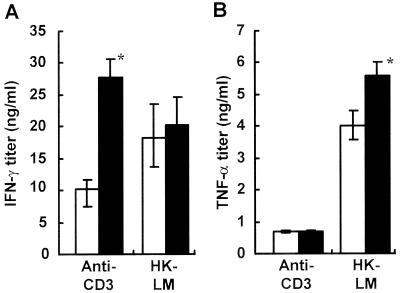

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on cytokine production in spleen cell cultures.

IFN-γ and TNF-α are known to be critical factors in antilisterial resistance (4, 16, 19, 30, 34, 38), and IL-4 reportedly plays a detrimental role in host defense (14). We investigated production of cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-4, in the spleen cell cultures obtained from vehicle- or 6-OHDA-treated mice. IFN-γ production in 6-OHDA-treated mice was markedly enhanced when they were stimulated with anti-CD3 MAb (Fig. 4A), whereas HK-LM-induced IFN-γ production was only slightly enhanced (Fig. 4A). Similarly, TNF-α production was increased by stimulation with HK-LM in 6-OHDA-treated spleen cells compared with vehicle-treated spleen cells (Fig. 4B). IL-4 production induced by HK-LM or anti-CD3 MAb was also determined. There were no significant differences between the vehicle-treated group and the 6-OHDA-treated group. Stimulated with HK-LM, the vehicle-treated mice produced 48 pg of IL-4 per ml and the 6-OHDA-treated mice produced 43 pg/ml; and stimulated with anti-CD3 MAb, the vehicle-treated mice produced 120 pg of IL-4 per ml and the 6-OHDA-treated mice produced 135 pg/ml.

FIG. 4.

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on IFN-γ and TNF-α production induced by anti-CD3 MAb or HK-LM in spleen cell cultures. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 6-OHDA (solid bars) or the vehicle (open bars). Spleen cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 MAb or HK-LM for 24 h. The titers of IFN-γ (A) and TNF-α (B) in the culture supernatants were measured. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on samples obtained from three mice. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the value obtained for the vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.05). The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

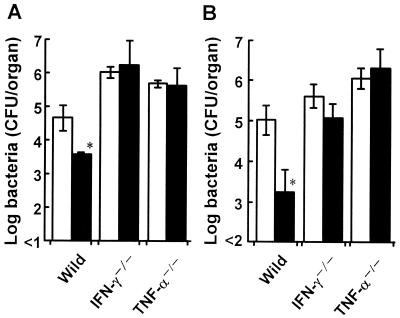

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on bacterial growth in cytokine-deficient mice.

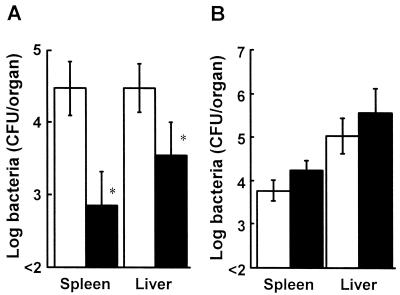

To examine the role of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the augmentation of host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection by 6-OHDA treatment, IFN-γ−/− or TNF-α−/− mice were injected with 6-OHDA or the vehicle, and they were each infected with 0.1 LD50 of L. monocytogenes. The numbers of viable bacteria in the organs were determined on day 4 after infection. The numbers of bacteria in the spleens and livers of 6-OHDA-treated IFN-γ−/− or TNF-α−/− mice were comparable to the numbers of bacteria in the spleens and livers of vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on the growth of L. monocytogenes cells in the spleens (A) and livers (B) of cytokine-deficient mice. Wild-type, IFN-γ−/−, and TNF-α−/− mice were injected with 6-OHDA (solid bars) or the vehicle (open bars) and were infected with 5 × 104, 1 × 103, or 1 × 102 CFU of L. monocytogenes 48 h later. The numbers of bacteria in the organs were determined on day 4 after infection. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on three mice. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the value obtained for the vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.05). The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

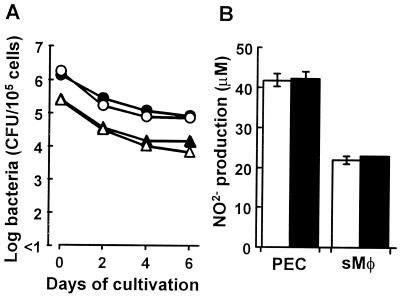

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on phagocytic and bactericidal activities of macrophages.

We investigated whether 6-OHDA treatment affects the phagocytic and listericidal activities of splenic macrophages and PEC in vitro. The drug treatment had no effect on the phagocytic activities of splenic macrophages (vehicle-treated mice, 2.47 × 105 CFU/105 cells; 6-OHDA-treated mice, 2.63 × 105 CFU/105 cells). Similar results were obtained for phagocytosis by PEC (vehicle-treated mice, 1.79 × 106 CFU/105 cells; 6-OHDA-treated mice, 1.39 × 106 CFU/105 cells). Next, the listericidal activities of splenic macrophages and PEC obtained from 6-OHDA-treated mice or vehicle-treated mice were determined 2, 4, and 6 h after phagocytosis. The numbers of viable bacteria in the splenic macrophages and PEC obtained from 6-OHDA-treated mice were comparable the numbers obtained for vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 6A). We also examined the effect of chemical sympathectomy on nitric oxide production by L. monocytogenes-infected PEC and splenic macrophages, and we found that 6-OHDA-treated and vehicle-treated PEC produced almost the same level of nitric oxide (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained when splenic macrophages were used (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on activation of PEC or splenic macrophages (sMΦ) obtained from 6-OHDA-treated mice (solid symbols) or vehicle-treated mice (open symbols). PEC (circles) or splenic macrophages (triangles) were mixed with L. monocytogenes cells and were cultured for 30 min at 37°C. After washing to remove the extracellular bacterial cells, the numbers of viable bacterial cells in the cell lysates at zero time and 2, 4, and 6 h later (A) and nitric oxide production by PEC and splenic macrophages in culture supernatants after 24 h of incubation (B) were estimated. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on four samples. The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

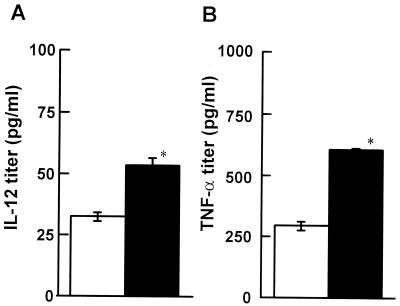

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on cytokine production in DC cultures.

It is known that cytokines, such as IL-12 produced by DC, are critical in Th1 differentiation (5). Therefore, the effect of 6-OHDA treatment on cytokine production by DC was investigated. Mice were infected with 5 × 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes on day 2 after injection of 6-OHDA or the vehicle. For each group five spleens were removed from the mice 24 h after infection, and DC were enriched. The enriched DC were cultured for 24 h in the presence of HK-LM, and the levels of cytokines, including IL-12p70, TNF-α, and IL-10, in the supernatants were measured. The titers of IL-12 and TNF-α produced by DC from 6-OHDA-treated mice were higher than the titers of these cytokines produced by DC from vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 7) (P < 0.05). IL-10 could not be detected in these cultures.

FIG. 7.

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on cytokine production induced by HK-LM in enriched DC cultures. Mice were injected with 6-OHDA (solid bars) or the vehicle (open bars) and were infected with 5 × 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes 48 h later. DC were obtained from the spleens of 6-OHDA- or vehicle-treated mice 24 h postinfection. DC were cultured in the presence of HK-LM for 24 h. The titers of IL-12p70 (A) and TNF-α (B) in the culture supernatants were measured. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on four samples. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the value obtained for the vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.05). The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

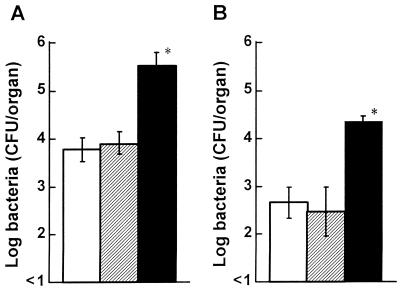

Role of T-cell subsets on host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection in 6-OHDA-treated mice.

To examine the effect of 6-OHDA on T-cell-dependent antilisterial resistance, CD4+ or CD8+ cells were depleted by injecting the corresponding MAbs into 6-OHDA-or vehicle-treated mice. When mice were pretreated with the vehicle, the numbers of bacteria in the spleens of CD8+ cell-depleted mice, but not in the spleens of CD4+ cell-depleted mice, were significantly higher than the numbers of bacteria in the spleens of normal rat globulin-treated mice 5 days postinfection (Fig. 8A) (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained when mice were denerved with 6-OHDA (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Effect of elimination of T-cell subsets on the growth of L. monocytogenes in the spleens of 6-OHDA-treated mice. Mice were injected with the vehicle (A) or 6-OHDA (B) and then received a single injection of normal rat globulin (open bars), anti-CD4 MAb (cross-hatched bars), or anti-CD8 MAb (solid bars) 24 h before infection. The mice were infected with 5 × 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes, and the numbers of bacteria were determined on day 5 after infection. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on three mice. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the value obtained for the normal rat globulin-treated mice (P < 0.01). The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on induction of acquired resistance against L. monocytogenes infection.

To investigate the effect of 6-OHDA treatment on induction of acquired resistance against L. monocytogenes infection, immune spleen cells obtained from 6-OHDA-or vehicle-treated mice were adoptively transferred to nonimmune and untreated mice. The mice were infected with 5 × 106 CFU of L. monocytogenes 24 h later, and the numbers of bacteria in the spleens and livers were determined 48 postinfection. Bacterial growth was significantly diminished in the organs of mice when immune spleen cells obtained from 6-OHDA-treated mice were transferred (Fig. 9A). Next, immune spleen cells obtained from untreated mice were adoptively transferred to nonimmune 6-OHDA- or vehicle-treated mice. The mice were infected with 5 × 106 CFU of L. monocytogenes 24 h later, and the number of bacteria in the spleens and livers were determined 48 postinfection. There were no significant differences in bacterial growth in this case (Fig. 9B).

FIG. 9.

Effect of 6-OHDA treatment on induction and expression of acquired resistance against L. monocytogenes. (A) Spleen cells immune to L. monocytogenes obtained from 6-OHDA-treated mice (solid bars) or vehicle-treated mice (open bars) were transferred to untreated naive recipients, and the mice were infected with 0.1 LD50 of L. monocytogenes cells 24 h later. Bacterial growth in the spleens and livers was determined 48 h postinfection. (B) Spleen cells immune to L. monocytogenes were transferred to 6-OHDA-treated mice (solid bars) or vehicle-treated mice (open bars), and the mice were infected with 5 × 106 CFU of L. monocytogenes cells 24 h later. Bacterial growth in the organs was determined 48 h postinfection. Each result is the mean ± standard deviation based on three mice. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the value obtained for the vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.05). The results were reproduced in three repeated experiments.

DISCUSSION

The results obtained by using mice that were chemically sympathectomized with 6-OHDA demonstrated that the sympathetic nervous system may downregulate host resistance against L. monocytogenes. It was assumed that the sympathetic nervous system might be involved in regulation of production of IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF-α, which are critical in antilisterial resistance.

6-OHDA reportedly destroys noradrenergic nerve termini in the peripheral nervous system (52). In the present study, a single injection of 6-OHDA significantly decreased the NE contents of the plasma and spleens (Fig. 1), and the splenic NE contents continued to decrease significantly until at least day 8 after injection (data not shown).

The present study also showed that 6-OHDA treatment enhanced host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection; 6-OHDA-treated mice were able to survive after infection with lethal doses of L. monocytogenes (Fig. 2A). The LD50 of L. monocytogenes for 6-OHDA-treated mice was about 20-fold higher than that for vehicle-treated mice. 6-OHDA treatment had no significant effect on bacterial growth in the spleens and livers of mice at 6 h (data not shown) or day 2 (Fig. 2B) postinfection. Innate immunity due to macrophages and neutrophils occurs at this stage (48). The results also demonstrated that the phagocytic activities, listericidal activities, and nitric oxide production in PEC and splenic macrophages from the drug-treated mice were comparable to those in PEC and splenic macrophages from the vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 6). In contrast, late in infection bacterial growth in the organs of 6-OHDA-treated mice was significantly inhibited compared with bacterial growth in the organs of vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2B); in the latter mice L. monocytogenes was eliminated from the organs of infected animals by T-cell-dependent mechanisms (48). Treatment with desipramine, which blocks the uptake of 6-OHDA into the nerve fibers and subsequent nerve destruction (23), prevented an increase in elimination of L. monocytogenes from the organs of 6-OHDA-treated mice (Fig. 3), suggesting that enhancement of antilisterial resistance by 6-OHDA might be drug specific.

TNF-α has been recognized as a critical factor in host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection due to activating macrophages and neutrophils (16, 30, 34, 38, 48). It has been reported that chemical sympathectomy by 6-OHDA upregulates production of cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-6 (8, 24, 28). Moreover, NE reportedly inhibits production of IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (14, 35, 41, 42, 49). Our results also showed that TNF-α production increased in both splenocytes (Fig. 4B) and DC (Fig. 7B) stimulated with HK-LM in 6-OHDA-treated mice. CD8+ T cells are known to play a critical role in elimination of L. monocytogenes from the organs of mice (15). In this study, a CD8+ T-cell-mediated mechanism enhanced antilisterial resistance by chemical sympathectomy because depletion of CD8+ cells abrogated the resistance (Fig. 8). Recent studies demonstrated that TNF-α is required for CD8+ T-cell-mediated antilisterial immunity (15, 50). The effect of 6-OHDA on bacterial growth in the organs was not observed with TNF-α−/− mice (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that upregulation of TNF-α production is involved in 6-OHDA-mediated augmentation of antilisterial resistance.

L. monocytogenes induces a Th1 response in the host (18), and IFN-γ plays a critical role in antilisterial resistance (4, 19). In this study, IFN-γ production was enhanced when spleen cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 MAb (Fig. 4A), indicating that the ability of T cells to produce IFN-γ may be increased by chemical sympathectomy. No effect of 6-OHDA on bacterial growth in the organs of IFN-γ−/− mice was observed (Fig. 5), suggesting that upregulation of IFN-γ production is also involved in 6-OHDA-mediated augmentation of antilisterial resistance. Alternatively, IL-4 is known to suppress antilisterial resistance (15), assuming that downregulation of IL-4 production may be involved in the resistance enhanced by chemical sympathectomy. However, the IL-4 production in 6-OHDA-treated mice was comparable to that in vehicle-treated mice.

Priming of naive T cells results from encounters with professional antigen-containing cells, such as DC. A recent study showed that NE controls DC migration from the site of inflammation to regional lymph nodes through an α1b-adrenergic receptor (29). Alternatively, it is known that cytokines, such as IL-12 produced by DC, are critical in Th1 differentiation (5). Our study demonstrated that more IL-12 was produced in response to HK-LM by splenic DC from 6-OHDA-treated mice than by splenic DC from vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 7A). Penina-Bordignon et al. (33) reported that β2-adrenergic receptor agonists prevented Th1 development by selective inhibition of IL-12. These finding suggest that upregulation of IL-12 production by DC, in addition to upregulation of TNF-α and IFN-γ production, may be involved in 6-OHDA-mediated augmentation of antilisterial resistance.

The present study showed that 6-OHDA treatment enhanced antilisterial activity late in infection (Fig. 2B), when L. monocytogenes is eliminated from the organs of infected animals by T-cell-dependent mechanisms (48). To address whether induction of adaptive immunity to L. monocytogenes infection is enhanced by chemical sympathectomy or denervation is required for expression of augmented antilisterial resistance, we investigated adoptive transfer of splenocytes immune to L. monocytogenes between 6-OHDA- or vehicle-treated donors and recipients (Fig. 9). Inhibition of bacterial growth was significantly enhanced in the organs of mice when immune spleen cells obtained from 6-OHDA-treated mice were transferred, while there were no significant differences in bacterial growth when spleen cells that were immune to L. monocytogenes and were obtained from untreated mice were transferred to 6-OHDA-treated or vehicle-treated mice. These results suggest that chemical sympathectomy might augment induction of adaptive immunity.

In contrast to our results, Alaniz et al. (1) reported that mice lacking dopamine β-hydroxylase, which cannot produce NE and epinephrine, exhibited impaired host resistance against L. monocytogenes infection and that production of IFN-γ and TNF-α by spleen cells was decreased in these animals. Although we cannot explain the discrepancy, there was a clear difference between the two systems in terms of NE content; the mutant mice lacked NE completely, and NE release in 6-OHDA-treated mice was partially inhibited. Alternatively, 6-OHDA destroys noradrenergic nerve termini only in the peripheral nervous system because the drug does not cross the blood-brain barrier (52), while dopamine β-hydroxylase-deficient mice lack NE in their whole bodies, including their brains (1). On the other hand, Rice et al. (37) recently reported that antilisterial resistance was enhanced by 6-OHDA pretreatment, which is consistent with our results. These authors also indicated that IFN-γ production induced by HK-LM was lower in spleen cell cultures obtained from 6-OHDA-treated mice on day 7 after infection but not on day 5 or 9 after infection. In our study, the levels of IFN-γ production induced by HK-LM in spleen cell cultures were comparable in 6-OHDA- and vehicle-treated mice before infection (Fig. 4) and on day 2 after infection (data not shown), but IFN-γ production was not investigated on day 7 after infection.

Recent studies demonstrated that Th1 clones and newly generated Th1 cells, but not Th2 clones or newly generated Th2 cells, express a β2-adrenergic receptor (10, 41). Reciprocal regulation of NE and immune responses, including differentiation of T cells and B cells and cytokine production, has been reported. Studies are being planned to clarify the precise mechanism of interaction between the sympathetic nervous system and antilisterial resistance through the roles of adrenergic receptor expressed in immunocompetent cells. IFN-γ production induced by HK-LM was lower in spleen cell cultures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by grant-in-aid for general scientific research 10670247 from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alaniz R C, Thomas S A, Perez-Melgosa M, Mueller K, Farr A G, Palmitter R D, Wilson C B. Dopamine β-hydroxylase deficiency impairs cellular immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2274–2278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blalock J E. The syntax of immune-neuroendocrine communication. Immunol Today. 1994;15:504–511. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bognar I T, Albrecht S A, Farasaty M, Schmitt E, Seidel G, Fuder H. Effects of human recombinant interleukins on stimulation-evoked noradrenaline overflow from the rat perfused spleen. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 1994;349:497–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00169139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchmeier N A, Schreiber R D. Requirement of endogenous interferon-γ for resolution of Listeria monocytogenes infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7404–7408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.21.7404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cella M, Scheidegger D, Palmer-Lehman K, Lane P, Lanzavecchia A, Alber G. Ligation of CD40 on dendritic cells triggers production of high levels of interleukin-12 and enhances T cell stimulatory capacity: T-T help via APC activation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:747–752. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chelmicka-Schorr E, Checinski M, Arnason B G W. Chemical sympathectomy augments the severity of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1988;17:347–350. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(88)90125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole S W, Korin Y D, Fahey J L, Zack J A. Norepinephrine accelerates HIV replication via protein kinase A-dependent effects on cytokine production. J Immunol. 1998;161:610–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Luigi A, Terreni L, Sironi M, De Simoni M G. The sympathetic nervous system tonically inhibits peripheral interleukin-1β and interleukin-6 by central lipopolysaccharide. Neuroscience. 1998;83:1245–1250. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downing J E, Miyan J A. Neural immunoregulation: emerging roles for nerves in immune homeostasis and disease. Immunol Today. 2000;21:281–289. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01635-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felten D L, Felten S Y, Belinger D L, Lorton D. Noradrenergic and peptidergic innervation of secondary lymphoid organs: role in experimental rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992;22:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felten D L, Felten S Y, Bellinger D L, Carlson S L, Ackerman K D, Madden K S, Olschowki J A, Livnat S. Noradrenergic sympathetic neural interactions with the immune system: structure and function. Immunol Rev. 1987;100:225–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs B A, Campbell K S, Munson A E. Norepinephrine and serotonin content of the murine spleen: Its relationship to lymphocyte β-adrenergic receptor density and the humoral immune response in vivo and in vitro. Cell Immunol. 1988;117:339–351. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green L C, Wanger D A, Glogowski J, Skipper P L, Wishnok J S, Tannenbaum S R. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N]nitrate in biologic fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haak-Frendsho M, Brown J F, Iizawa Y, Wagner R D, Czuprynski C J. Administration of anti-IL-4 monoclonal antibody 11B11 increases the resistance of mice to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 1992;148:3978–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harty J T, Tvinnerem A R, White D W. CD8+ T cell effector mechanisms in resistance to infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:275–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Havell E A. Production of tumor necrosis factor during murine listeriosis. J Immunol. 1987;139:4225–4231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch E, Irikura V M, Oaul S M, Hirsh D. Functions of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in gene knockout and overproducing mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11008–11013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh C-S, Macatonia S E, Tripp C S, Wolf S F, O'Garra A, Murphy K H. Development of Th1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science. 1993;260:547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel R M, Aguet M. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-γ receptor. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jetschmann J U, Benschop R J, Jacobs R, Kemper A, Oberbeck R, Schmidt R E, Schedlowski M. Expression and in-vivo modulation of α- and β-adrenoceptors on human natural killer (CD16+) cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;74:159–164. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohm A P, Sanders V M. Suppression of antigen-specific Th2 cell-dependent IgM and IgG1 production following norepinephrine depletion in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:5299–5308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohm A P, Sanders V M. Norepinephrine: a messenger from the brain to the immune system. Immunol Today. 2000;21:539–542. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, Freudenberg M, Lamers M, Kishimoto T, Zinkernagel R, Bluethmann H, Kohler G. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;368:339–342. doi: 10.1038/368339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruszewska B, Felten S Y, Moynihan J A. Alterations in cytokine and antibody production following chemical sympathectomy in two strains of mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:4613–4620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leo N A, Callahan T A, Bonneau R H. Peripheral sympathetic denervation alters both the primary and memory cellular immune responses to herpes simplex virus infection. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1998;5:22–35. doi: 10.1159/000026323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madden K S, Felten S Y, Felten D L, Hardy C A, Livnat S. Sympathetic neural modulation of the immune system. II. Induction of lymphocyte proliferation and migration in vivo chemical sympathectomy. J Immunol. 1994;49:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madden K S, Felten S Y, Felten D L, Sundarcsan P R, Livnat S. Sympathetic neural modulation of the immune system. I. Depression of T cell immunity in vivo and in vitro following chemical sympathectomy. Brain Behav Immun. 1989;3:72–89. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(89)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madden K S, Moynihan J A, Brenner G J, Felten S Y, Felten D L, Livnat S. Sympathetic nervous system modulation of the immune system. III. Alterations in T and B cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro following chemical sympathectomy. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;49:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maestroni G J M. Dendritic cell migration controlled by α1b-adrenergic receptors. J Immunol. 2000;165:6743–6747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakane A, Minagawa T, Kato K. Endogenous tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) is essential to host resistance against Listeria monocytogenes infection. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2563–2569. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2563-2569.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakane A, Nishikawa S, Sasaki S, Miura T, Asano M, Kohanawa M, Ishiwata K, Minagawa T. Endogenous interleukin-4, but not interleukin-10, is involved in suppression of host resistance against Listeria monocytogenes infection in gamma interferon-depleted mice. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1252–1258. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1252-1258.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakane A, Okamoto M, Asano M, Kohanawa M, Minagawa T. An anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody protects mice against a lethal infection with Listeria monocytogenes through induction of endogenous cytokines. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2786–2792. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2786-2792.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panina-Bordignon P, Mazzeo D, Di Lucia P, D'Ambrosio D, Lang R, Fabbri L, Self C, Sinigaglia F. β2-Agonists prevent Th1 development by selective inhibition of interleukin 12. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1513–1519. doi: 10.1172/JCI119674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfeffer K, Matsuyama T, Kündig T M, Wakeham A, Kishihara K, Shahinian A, Wiegmann K, Ohashi P S, Krönke M, Mak T W. Mice deficient for 55 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxin shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell. 1993;73:457–467. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90134-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramer-Quinn D S, Baker R A, Sanders V M. Activated Th1 and Th2 cells differentially express the beta-2-adrenergic receptor: a mechanism for selective modulation of Th1 cell cytokine production. J Immunol. 1997;159:4857–4867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reilly F D, McCuskey P A, Miller M L, McCuskey R S, Meineke H A. Innervation of the periarteriolar lymphatic sheath of the spleen. Tissue Cell. 1979;11:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(79)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice P A, Boehm G W, Moynihan J A, Bellinger D L, Stevens S Y. Chemical sympathectomy increases the innate immune response and decreases the specific immune response in the spleen to infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;114:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothe J, Lesslauer W, Lotscher H, Lang Y, Koebel P, Kontgen F, Althage A, Zinkernagel R, Steinmetz M, Bluethmann H. Mice lacking the tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 are resistant to TNF-mediated toxicity but highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 1993;364:798–802. doi: 10.1038/364798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruedle C, Rieser C, Böck G, Wick G, Wolf H. Phenotypic and functional characterization of CD11c+ dendritic cell population in mouse Peyer's patches. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1801–1806. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruhl A, Hurst S, Collins S M. Synergism between interleukin 1 beta and 6 on noradrenergic neurons in rat myenteric plexus. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:993–1001. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanders V M, Baker R A, Ramer-Quinn D S, Kasprowicz D J, Fuchs B A, Street N E. Differential expression of the beta-2-adrenergic receptor by Th1 and Th2 clones: implication for cytokine production and B cell help. J Immunol. 1997;158:4200–4210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Severn A, Rapson N T, Hunter C A, Liew F Y. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor production by adrenaline and β-adrenergic agonist. J Immunol. 1992;148:3441–3445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soliven B, Albert J. Tumor necrosis factor modulates the inactivation of catecholamine secretion in cultured sympathetic neurons. J Neurochem. 1992;58:1073–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straub R H, Westermann J, Schölmerich J, Falk W. Dialogue between the CNS and the immune system in lymphoid organs. Immunol Today. 1998;19:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swanson M A, Lee W T, Sanders V M. IFN-γ production by Th1 cells generated from naïve CD4+ T cells exposed to norepinephrine. J Immunol. 2001;166:232–240. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tagawa Y, Sekikawa K, Iwakura Y. Suppression of concanavalin A-induced hepatitis in IFN-γ−/− mice, but not in TNF-α−/− mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:1418–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taniguchi T, Takata M, Ikeda A, Momotani E, Sekikawa K. Failure of germinal center formation and impairment of response to endotoxin in tumor necrosis factor α-deficient mice. Lab Invest. 1997;77:647–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Unanue E R. Studies in listeriosis show the strong symbiosis between the innate cellular system and the T-cell response. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:11–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van der Poll T, Jansen J, Endert E, Sauerwein H P, van Deventer S J H. Noradrenaline inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 6 production in human whole blood. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2046–2050. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2046-2050.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White D W, Badovinac V P, Kollias G, Harty J T. Antilisterial activity of CD8+ T cells derived from TNF-deficient and TNF/perforin double-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:5–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams J M, Felten D L. Sympathetic innervation of murine thymus and spleen: a comparative histofluorescence study. Anat Rec. 1981;199:531–542. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091990409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams L M, Peterson R G, Shea P A, Schmedtje J F, Bauer D C, Felten D L. Sympathetic innervation of murine thymus and spleen: evidence for a functional link between the nervous and immune systems. Brain Res Bull. 1981;6:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(81)80072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]