Abstract

Background

Previous studies have demonstrated low first‐time donor return rates (DRR) following catastrophic events. Little is known, however, about the influence of demographic factors on the DRR of first‐time donors during the COVID‐19 pandemic, including the unique motivation of COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) donors as compared to non‐CCP donors.

Study Design and Methods

Thirteen blood collection organizations submitted deidentified data from first‐time CCP and non‐CCP donors returning for regular (non‐CCP) donations during the pandemic. DRR was calculated as frequencies. Demographic factors associated with returning donors: race/ethnicity, gender, and generation (Gen Z: 19–24, Millennial: 25–40, Gen X: 41–56, and Boomer: ≥57 years old), within the CCP and non‐CCP first‐time cohorts were compared using chi‐square test at p < .05 statistical significance.

Results

From March 2020 through December 2021, there were a total of 44,274 first‐time CCP and 980,201 first‐time non‐CCP donors. DRR were 14.6% (range 11.9%–43.3%) and 46.6% (range 10.0%–76.9%) for CCP and non‐CCP cohorts, respectively. Age over 40 years (Gen X and Boomers), female gender, and White race were each associated with higher return in both donor cohorts (p < .001). For the non‐CCP return donor cohort, the Millennial and Boomers were comparable.

Conclusion

The findings demonstrate differences in returning donor trends between the two donor cohorts. The motivation of a first‐time CCP donor may be different than that of a non‐CCP donor. Further study to improve first‐time donor engagement would be worthwhile to expand the donor base with a focus on blood donor diversity emphasizing engagement of underrepresented minorities and younger donors.

Keywords: blood donor collections, COVID‐19 convalescent plasma donors, donor demographics, first‐time donor return rates

List of abbreviations

- BCOs

blood collection organizations

- CCP

COVID‐19 convalescent plasma

- DAEs

donor adverse events

- DRR

donor return rate

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- NBCUS

National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey

- RBCs

red blood cells

- WB

whole blood

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic disrupted countless aspects of healthcare, and its impact on the blood supply has been no exception. The blood shortages exacerbated by the pandemic have been chronic and sustained with a national and global impact. Like disaster situations with an acute need, it has been a motivating factor for first‐time donors. While previous studies have demonstrated low first‐time donor return rates (DRR) following catastrophic events, 1 , 2 , 3 little is known about the influence of demographic factors on the DRR of first‐time donors during the COVID‐19 pandemic, including the unique motivation of COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) donors and non‐CCP donors.

At the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, 4 collections at mobile blood drives and fixed donation sites rapidly declined as schools and businesses transitioned with strong recommendations for people to stay at home and practice social distancing. After the United States Surgeon General, Jerome Adams urged Americans to donate blood on March 19, 2020, there was an initial strong response to the blood shortage, which unfortunately wasn't sustained. 5 As the COVID‐19 risks of being in crowded public spaces increased, even regular blood donors became wary about coming to blood centers to donate despite the adoption of appropriate precautions in donor rooms including optimizing physical distancing, masking, and disinfection protocols.

As thousands of people became critically ill with COVID‐19 in the absence of effective therapies, many blood collection organizations (BCOs) across the country began collecting CCP from recovered patients as soon as March 2020 with the intent that passive immunotherapy with plasma might be effective and was likely safe. 6 CCP became one of the most common treatments despite limited efficacy data until April 2021. 7 Many of the individuals who presented to donate CCP were first‐time blood donors with no previous donation experience. 8 In addition, many healthy individuals stepped forward to donate blood for the first time in response to the critical blood shortages. CCP collections were paused at most BCOs in March 2021 when evidence for the broad effectiveness of CCP as a therapeutic modality was insufficient and pharmacotherapeutics were becoming more widely available. 7 Unfortunately, BCOs have continued to struggle with chronic blood shortages throughout the pandemic due to the ongoing disruption of blood drives, decreased mobile collections, and staffing shortages.

In the last 3 years, the national blood shortage has been exacerbated by the COVID‐19 pandemic emphasizing the critical need to recruit and retain blood donors. 9 , 10 Improving donor retention has been the focus of previous studies, which have assessed donor motivation and strategies to promote donor retention in an ongoing effort to secure a stable blood supply. 11 , 12 Early insight into the impact of COVID‐19 on blood donors and their motivation to donate has been reported from Europe, as has donor intention to return which correlated with donor satisfaction. 13 , 14 Yet, little is known about the likelihood that CCP donors will convert to standard donors of whole blood or apheresis products. The primary goal of this study is to describe the demographic characteristics of the CCP and non‐CCP return donor cohorts to identify potential retention strategies that could be leveraged to promote continued donation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirteen participating BCOs, collecting approximately 65% of the United States blood supply, submitted de‐identified aggregate data on return behaviors of first‐time donors CCP and non‐CCP donors from the start of CCP collections through the end of December 2021. Data were merged in a combined data set for analysis by the AABB Department of Research and Data Initiatives. The total number of first‐time CCP and non‐CCP donors during the study period were collected, as well as the total number of return donors, defined as CCP donors converted to standard donors and returning non‐CCP donors. (All BCOs define “first‐time donor” as the first donation within their system.) For return donors, demographic information was collected by generational age group as follows: Gen Z, age 19–24 years old, born 1997–2002; Millennial, age 25–40 years old, born 1981–1996; Gen X, age 41–56, born 1965–1980; and Boomer, age greater than or equal to 57, born 1964 or earlier. Donors born in 1925–1945 were included with the Boomer generation as they represented a minor percentage of the donors. Additional demographic information was collected for each cohort, including gender (male, female, or “other/nonbinary”) and race/ethnicity (Asian, Black, White, Hispanic, Other/Multiple races, and prefer not to disclose).

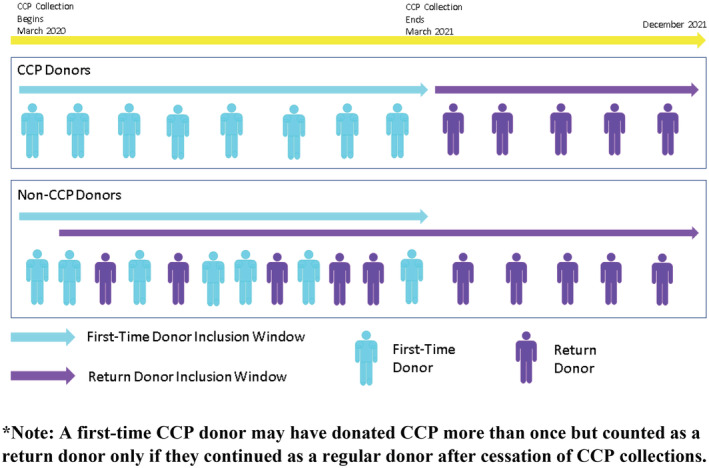

To limit the scope of data considering the technical capabilities of the participating BCOs, we chose to only collect and compare demographic data on the returning first‐time donors in both the CCP and non‐CCP cohorts. Because each BCO began collecting CCP on dates as early as March 2020, and to ensure all data were consistent, the dates for identifying first‐time CCP donors are variable. The DRR timeframe was also different for each cohort. (Figure 1) Specifically, first‐time CCP donors may have donated CCP more than once, but were only counted as return donor if they converted to standard donations after the cessation of CCP collections.

FIGURE 1.

Timeframe of first‐time COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) and non‐CCP donors into the return donor pool. A first‐time CCP donor may have donated CCP more than once but counted as a return donor only if they continued as a regular donor after cessation of CCP collections.

We calculated frequencies to determine the DRR of first‐time donors whose initial donation was for CCP between March 2020 and March 2021 (depending on when the BCO started and stopped CCP collections) and who continued donation of non‐CCP blood or blood components after the discontinuation of CCP collections in March 2021 through December 31, 2021 (see Figure 1). The DRR of first‐time non‐CCP donors presenting during the same study period was counted for donors who donated more than once through the end of December 2021. Each returning donor was counted only once regardless of the number of times the donor presented to donate. Of note, the race/ethnicity analysis was available for 12 of the 13 BCOs. (One BCO did not have the capability to identify race and reported 100% of their donors as “prefer not to disclose”; therefore, these data points were removed from the analysis). (Table 1) Demographic factors associated with returning donors within the CCP and non‐CCP first‐time donor cohorts were compared using the chi‐square test at p < .05 as statistically significant using SAS 9.4. Direct comparisons between the two cohorts were not conducted to avoid bias because of unequal follow‐up periods and the additional criteria for CCP donors (such as timing of COVID‐19 infection and vaccinations).

TABLE 1.

Demographics of COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) and non‐CCP donors

| Donor characteristics | CCP donor frequency n (%) | Non‐CCP donor frequency n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Donor status | ||

| First‐time donors | 44,274 | 980,201 |

| Return donors | 6458 (14.6%) | 457,054 (46.6%) |

| Age | ||

| Gen Z: 19–24 (2002–1997) | 341 (5.3%) | 31,071 (6.8%) |

| Millennial: 25–40 (1996–1981) | 1606 (24.9%) | 136,263 (29.8%) |

| Gen X: 41–56 (1980–1965) | 2272 (35.2%) | 156,629 (34.3%) |

| Boomer: ≥57 (1964 or earlier) | 2239 (34.7%) | 133,091 (29.1%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2578 (39.8%) | 185,067 (40.5%) |

| Female | 3888 (60.2%) | 271,964 (59.5%) |

| Other | 0 (0.00%) | 23 (0.01%) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 195 (3.1%) | 14,416 (3.2%) |

| Black/African American | 112 (1.8%) | 8939 (2.0%) |

| Caucasian/White | 4942 (78.6%) | 386,253 (85.8%) |

| Hispanic | 536 (8.5%) | 24,421 (5.4%) |

| Other/multiple race | 157 (2.5%) | 10,680 (2.4%) |

| Prefer not to disclose a | 345 (5.5%) | 5553 (1.2%) |

Race/Ethnicity frequencies were calculated after removing 171 CCP and 6792 non‐CCP return donors from the BCO not collecting Race/Ethnicity data. The n for Race/Ethnicity is 6287 CCP and 450,262 non‐CCP donors.

The participating BCOs included the American Red Cross, Community Blood Center of Greater Kansas City, Innovative Blood Resources, New York Blood Center (divisions of New York Blood Center Enterprises), ImpactLife, Mayo Clinic Blood Donor Center, Miller‐Keystone Blood Center, Oklahoma Blood Institute, South Texas Blood and Tissue, Stanford Blood Center, UCLA Blood, and Platelet Center, Versiti (Wisconsin), and Vitalant. The collective BCOs are hereafter arbitrarily numbered “Org” 1 through 13.

3. RESULTS

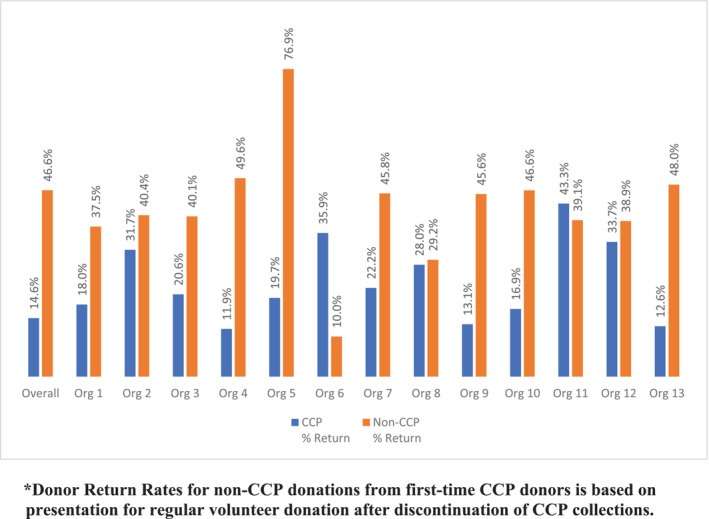

During the study period, there were a total of 44,274 first‐time CCP and 980,201 first‐time non‐CCP donors (Tables 1 & 2). Overall, there was a 14.6% DRR of CCP donors (range 11.9%–43.3%) versus 46.6% for non‐CCP donors (range 10.0%–76.9%). (Figure 2).

TABLE 2.

Percentage of return donor demographics by blood collection organizations (BCOs)

| 2a: CCP return donors | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self‐identified gender | Generation | Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Male | Female | Other | Gen Z | Millennial | Gen X | Boomer | Asian | Black | White | Hispanic | Other/multiple | Not disclosed | ||

| CCP donors | Org 1 | 55% | 45% | 0% | 4% | 15% | 28% | 52% | 1% | 1% | 66% | 3% | 4% | 24% |

| Org 2 | 36% | 64% | 0% | 5% | 16% | 36% | 43% | 1% | 1% | 94% | 3% | 1% | 0% | |

| Org 3 | 43% | 57% | 0% | 4% | 25% | 38% | 33% | 0% | 1% | 93% | 1% | 0% | 5% | |

| Org 4 | 45% | 55% | 0% | 6% | 35% | 32% | 27% | 6% | 3% | 75% | 13% | 4% | 0% | |

| Org 5 | 43% | 57% | 0% | 7% | 26% | 28% | 39% | 0% | 0% | 96% | 0% | 2% | 2% | |

| Org 6 | 54% | 46% | 0% | 4% | 21% | 39% | 36% | 0% | 0% | 86% | 4% | 0% | 11% | |

| Org 7 | 53% | 47% | 0% | 12% | 26% | 32% | 29% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| Org 8 | 38% | 62% | 0% | 11% | 41% | 23% | 25% | 15% | 2% | 60% | 18% | 4% | 1% | |

| Org 9 | 38% | 62% | 0% | 4% | 22% | 35% | 40% | 2% | 1% | 82% | 10% | 1% | 4% | |

| Org 10 | 83% | 17% | 0% | 8% | 17% | 50% | 25% | 17% | 0% | 50% | 25% | 8% | 0% | |

| Org 11 | 70% | 30% | 0% | 7% | 19% | 29% | 45% | 2% | 3% | 82% | 5% | 5% | 3% | |

| Org 12 | 29% | 71% | 0% | 2% | 18% | 37% | 43% | 1% | 0% | 39% | 2% | 0% | 58% | |

| Org 13 | 34% | 66% | 0% | 5% | 24% | 38% | 33% | 3% | 2% | 84% | 9% | 2% | 1% | |

| 2b: Non‐CCP return donors | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self‐identified gender | Generation | Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Male | Female | Other | Gen Z | Millennial | Gen X | Boomer | Asian | Black | White | Hispanic | Other/multiple | Not disclosed | ||

| Non‐CCP donors | Org 1 | 44% | 56% | 0% | 10% | 27% | 30% | 33% | 1% | 1% | 63% | 3% | 6% | 25% |

| Org 2 | 43% | 57% | 0% | 14% | 30% | 29% | 27% | 2% | 2% | 89% | 4% | 2% | 0% | |

| Org 3 | 41.19% | 58.59% | 0.22% | 10% | 32% | 31% | 28% | 2% | 1% | 90% | 2% | 2% | 3% | |

| Org 4 | 44% | 56% | 0% | 10% | 38% | 29% | 23% | 9% | 3% | 72% | 11% | 5% | 0% | |

| Org 5 | 38% | 62% | 0% | 13% | 43% | 23% | 22% | 4% | 1% | 88% | 3% | 3% | 1% | |

| Org 6 | 39% | 61% | 0% | 7% | 13% | 39% | 41% | 0% | 1% | 79% | 2% | 1% | 17% | |

| Org 7 | 44% | 56% | 0% | 6% | 32% | 36% | 26% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| Org 8 | 41% | 59% | 0% | 18% | 42% | 22% | 18% | 20% | 3% | 57% | 16% | 3% | 1% | |

| Org 9 | 44% | 56% | 0% | 6% | 30% | 33% | 32% | 3% | 1% | 81% | 10% | 2% | 3% | |

| Org 10 | 43.33% | 56.50% | 0.17% | 10% | 39% | 28% | 23% | 19% | 1% | 61% | 9% | 9% | 1% | |

| Org 11 | 45% | 55% | 0% | 10% | 27% | 33% | 29% | 1% | 2% | 85% | 6% | 6% | 0% | |

| Org 12 | 43% | 57% | 0% | 9% | 25% | 32% | 34% | 2% | 2% | 85% | 4% | 1% | 6% | |

| Org 13 | 39% | 61% | 0% | 6% | 29% | 35% | 29% | 3% | 2% | 88% | 4% | 2% | 1% | |

Note: Race/Ethnicity calculations do not include donors from Org 7 (highlighted gray).

FIGURE 2.

COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) and non‐CCP first‐time donor return rates. Donor Return Rates for non‐CCP donations from first‐time CCP donors are based on the presentation for regular volunteer donations after the discontinuation of CCP collections.

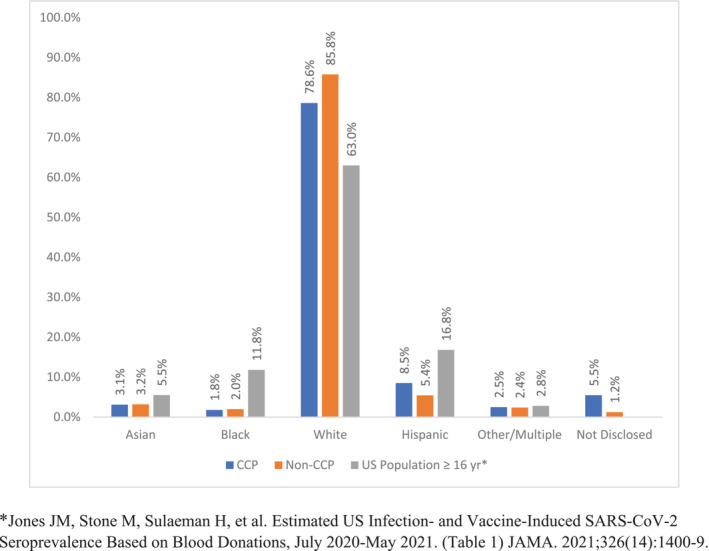

Donor race/ethnicity distributions were similar between returning CCP and non‐CCP donors. A significant majority of return donors in both cohorts self‐identified as White (78.6%: CCP and 85.8% non‐CCP; p < .001; χ 2(df) = 5). Return donors who self‐identified as Hispanic accounted for 8.5% of CCP and 5.4% of non‐CCP cohorts. Return donors who preferred not to disclose their race/ethnicity were 5.5% for CCP and 1.2% for non‐CCP cohorts. Other races comprised comparable percentages in both cohorts of approximately: Asian—3.0%, Black—2.0%, and Other/Multiple—2.0%. When compared to the United States general population census data from July 2020 to May 2021, 15 proportionate differences in the distribution of race/ethnicity of the returning donor cohorts are observed. (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of race/ethnicity between COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) and non‐CCP return donors and proportionate United States population ≥ 16y from July 2020 to May 2021. *Jones JM, Stone M, Sulaeman H, et al. Estimated US Infection‐ and Vaccine‐Induced SARS‐CoV‐2 Seroprevalence Based on Blood Donations, July 2020–May 2021. (Table 1) JAMA. 2021;326 (14):1400–9.

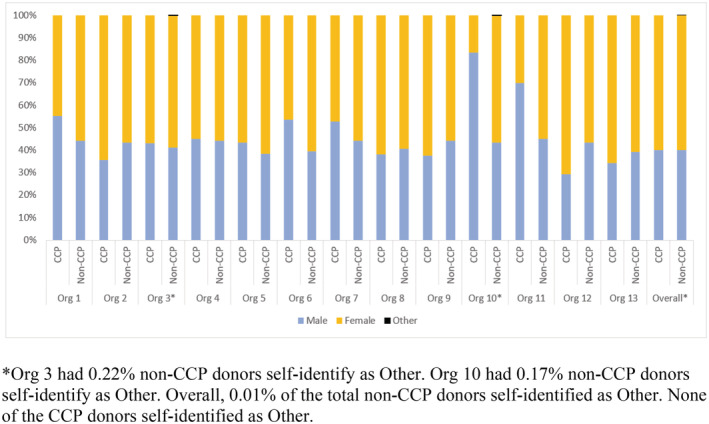

The male: female ratio of returning first‐time donors was approximately 40:60 in both donor cohorts (p < .001; χ 2(df) = 1). In addition, two BCOs offer “other/nonbinary” gender options while the remainder used only self‐identified male and female options. No returning first‐time donors in the CCP group identified their gender as other or nonbinary compared to 0.01% of the non‐CCP group. While the gender composition was similar among the BCOs for the non‐CCP cohort, significant variation in gender distribution was observed in the CCP cohort. Returning CCP male donors ranged from 29.4%–83.3% compared to 16.7%–70.6% for female donors. Of interest, male donors comprised well over 60% of the CCP return donor cohort at two of the BCOs (orgs 10 and 11). In contrast, females represented approximately 70% CCP return donor cohort at org 12. (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Gender comparison by blood collection organizations (BCOs) between COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) and non‐CCP return donors. *Org 3 had 0.22% of non‐CCP donors self‐identify as Other. Org 10 had 0.17% of non‐CCP donors self‐identify as Other. Overall, 0.01% of the total non‐CCP donors self‐identified as Other. None of the CCP donors self‐identified as Other.

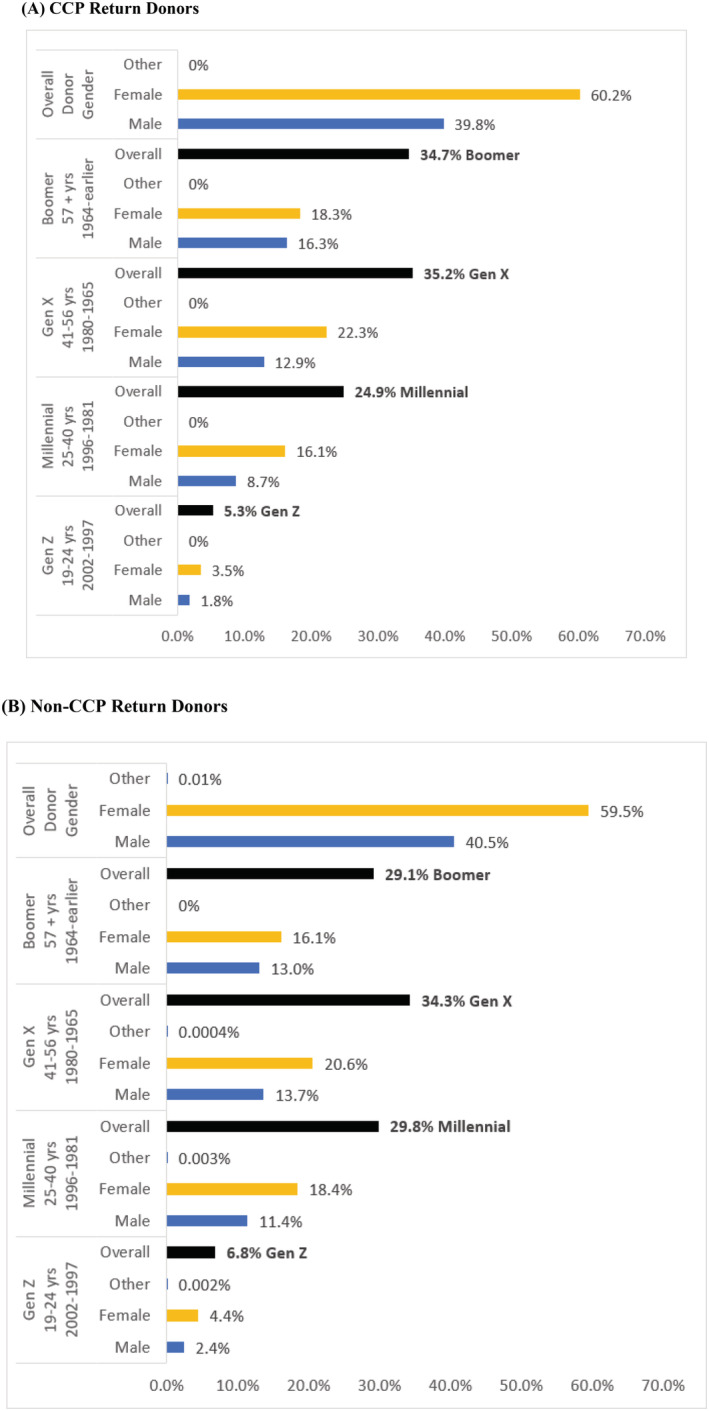

Generational demographics of first‐time CCP donors converted to standard blood donors versus returning first‐time non‐CCP donors were as follows: Gen Z (5.3% vs. 6.8%), Millennial (24.9% vs. 29.8%), Gen X (35.2% vs. 34.3%), and Boomer (34.7% vs. 29.1%). Donors over 40 years old (Gen X and Boomer generations) were associated with a higher representation of returning donors in both CCP and non‐CCP groups (p < .0001; χ 2(df) = 1). In addition, the Millennial return donors were comparable to Boomers for the non‐CCP group. The youngest donors (Gen Z) were the lowest for both return donor cohorts. Stratification of donor gender by age/generation demonstrated a consistently higher representation of females compared to males across all generations in both CCP and non‐CCP donor cohorts. (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) (A) and non‐CCP (B) return donors by generation and self‐reported gender

4. DISCUSSION

This study of first‐time CCP donors converting to standard blood donation and returning first‐time non‐CCP (standard) donors during the COVID‐19 pandemic (14.6% vs. 46.6%) found similar donor demographics distribution in both cohorts with a strong association with age over 40 years, female gender, and White race (p < .001).

A strength of this study is the broad spectrum of representation nationwide by both large and small BCOs. Overall, the DRR of first‐time CCP donors was lower than the frequency of return of first‐time non‐CCP donors (14.6% vs. 46.6%); however, we were unable to take into account the differences in the length of the window of opportunity for return between the cohorts (Figure 1). While specific strategies for recruitment and retention of CCP and non‐CCP donors were not the focus of this study, striking variation in DRR was observed in both donor cohorts between the participating BCOs. This could be due to a variety of reasons, including donation experience, reaction rates, and a unique motivation of individuals who recovered from COVID‐19 during the pandemic to donate CCP but not standard allogeneic donations. Further study to explore differences in donor engagement strategies between the BCOs for both the CCP and non‐CCP donor cohorts could help to identify best practices for recruitment and retention.

Several studies have identified higher rates of donor adverse events (DAEs) among CCP donors due to their higher proportion of first‐time donation experience, which would contribute to a lower likelihood of donor return. 8 , 16 , 17 Also, CCP donors who became ineligible to donate based on falling antibody titers may also have been less likely to return as regular blood donors.

The 2019 National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey (NBCUS) found that 31% of all whole blood (WB) donations in the United States were from first‐time donors. 18 However, challenges associated with the pandemic critically impacted the blood industry due to social distancing, loss of sponsor mobile blood drive venues, and unprecedented challenges with donor engagement resulting in fewer first‐time donors and lower donor retention rates over the last 2 years, as described during an AABB Blood Summit event. 19 While we did not collect data to determine the proportion of first‐time donors, differences in the DRRs between the BCOs offer an important opportunity for further study to identify successful strategies for engaging first‐time donors and encouraging donor return/retention. For example, organization 5 was found to have the highest DRR of non‐CCP donors at 76.9%, while organization 11 had the highest DRR of CCP donors at 43.3%. (Figure 2) Both BCOs had very targeted strategies to engage these donors and encourage continued donation. Org 11 specifically focused on a recruitment push to convert CCP donors to regular donors and shared that their efforts were most effective with Gen X and Boomers based on their own internal analysis.

The importance of diversity in our blood supply cannot be over‐emphasized and remains a challenge as highlighted by the findings in this study. Drawing on published information from the 2019 NBCUS, 19.5% of all whole blood and apheresis red blood cells (RBCs) were from racial or ethnic minority donors. 18 In contrast, relatively limited demographic information is available about CCP donors, many of whom donated plasma by apheresis. In a large study of CCP donors from a single BCO, the majority were White (82.4%) with 17.6% of racial/ethnic diverse populations. 16 Overall, the racial demographics of CCP donors in this study were similar to the standard apheresis and WB donors with a predominance of White donors (>82%) followed by Hispanic, Asian, and Black donors in each group. 16 In another study of CCP donors in the New York metropolitan area from 3/26/2020 to 7/7/2020, 8 CCP donors were somewhat more likely to self‐identify as White compared to non‐CCP WB donors and less likely to self‐identify as Latino, Asian, or Black. This is roughly comparable to our findings of 21.4% minority representation in returning first‐time CCP donors and 14.2% of returning non‐CCP donors. Further study is needed to identify effective recruitment and retention strategies, including ease of donation for minority populations incorporating equity and inclusion of donors from all race/ethnicity cohorts. For example, it's difficult to meet the needs of patients requiring rare blood phenotypes that are distributed by race/ethnicity if BCOs do not engage diverse donor populations. As observed in Figure 3, there is still significant underrepresentation of Blacks among blood donors, which contributes to the transfusion challenges for patients with sickle cell disease. Working to achieve equity and promote inclusion is both crucial and complex, but an important consideration for BCOs to help address existing medical disparities. Shifts in donor gender composition with a female predominance and increasing gap between male and female donors have been noted during the last 3 years with the greatest drops among the younger male donors. 20 Our study also found striking female gender predominance in both the returning CCP and non‐CCP donors, with the exception of a greater percentage of returning male CCP donors at two BCOs. The reason for this finding wasn't explored; however, prescreening policies of CCP donors may have contributed to the differences in gender representation. 17 For example, some BCOs may have had recruitment efforts with a bias toward male donors at some stages for CCP collection. In addition, some females with a history of pregnancy may not have qualified due to positive screening results for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antibodies.

While there is less available data for gender comparison in CCP donors, two previous studies found a slightly greater distribution of female CCP donors (56.9% and 51.6%). 8 , 16 This is in contrast with the 2019 NBCUS findings documenting a slight predominance of male blood donors in the United States. 21

Most BCOs do not offer an “other” gender option because of limitations of their blood establishment computer system and provide for only self‐identified males or females. While headway is being made toward individualized risk assessment in the United States, 22 it's important to recognize that negative belief, stigma, and discrimination against individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ contribute to medical disparities that jeopardize their health. Creating an environment of inclusivity for members of this community who are at a disproportionate risk due to their sexuality, gender identity, or gender expression represents an opportunity for many BCOs. 23 , 24

Prior to the pandemic, it was observed that donations from younger donors had continued to decline in the United States, while the proportion of donations from older donors steadily increased. 18 This trend was heightened during the pandemic. Among the challenges related to new donor recruitment and retention, there was a 47.7% decline in donors less than 24 years old. 19 A 37.9% increase in donors in the 60 to greater than 70‐year age group has also occurred in the last 10 years. 20 These age demographics are consistent with the returning donor trends identified in this study. As noted, Gen Z has the lowest distribution of return donors in this study with an age span of only 5 years (19–24 years) compared to a span of 15 or more years in the other generations. In addition, there has been a striking decline in the base of young donors during the pandemic attributed to the cancellation of blood drives due to COVID‐19, which heavily impacted the education sector. 19 Comparing the donor cohorts, it's interesting that there was a higher proportion of returning non‐CCP donors in the younger generations with Millennials comparable to the Boomers in this cohort, suggestive of some success with this generation. Future studies should continue to explore methods for engaging younger generations through existing social networks and new innovative strategies. 12 , 13 , 14 , 25 , 26

An important limitation of this study is the DRR of the first‐time CCP and non‐CCP donor cohorts are not entirely comparable due to the study design as illustrated in Figure 1. Specifically, first‐time CCP donors returning to donate non‐CCP products were not counted during the study period until after CCP collections were discontinued, which allowed a timeframe of approximately 9 months through the end of 2021. In contrast, the study interval allowed up to approximately 21 months for first‐time non‐CCP donors to return. While we were unable to perform mathematical modeling to determine the statistical significance of the discrepancy between the donor cohorts, the differences in donation experience and motivation to give CCP after recovering from COVID‐19 are also likely to have influenced continued donation efforts after CCP collections ceased. In addition, we could not assess whether there was “pandemic fatigue” with less likelihood for first‐time donors to return after March 2021 compared to the initial pleas to donate early in the pandemic since this level of detail was not captured.

5. CONCLUSION

This large multi‐institutional study demonstrates differences in returning donor trends between first‐time CCP and non‐CCP donors. We suspect this is related to differing motivations between these two groups. Similarities in the demographics between the two cohorts indicate that BCOs need to focus on underrepresented populations. Further study to improve first‐time donor engagement would be worthwhile to expand the donor base with focused efforts to effectively recruit and retain younger donors and those in minority populations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest relevant to this manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the entire membership of the AABB Donor Hemovigilance Working Group for the development of the project proposal that led to this study. While some of the members were not affiliated with the participating BCOs, they deserve special recognition for their contributions, including Dr. George Schreiber, Dr. Joseph Cho, Dr. Richard Gammon, Dr. Thomas Gniadek, Dr. Joy Fridey, Dr. Angelica Vivero, Dr. Michele Zeller, Dr. Rim Abdallah, Dr. Mark Fung, and Dr. Chester Andrzejewski.

The authors also gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for their invaluable assistance with the collection of data for their respective BCO sites: Pete Lux (ImpactLife), Kim Duffy (Mayo Clinic Blood Center), Nicolas Loew (Miller‐Keystone Blood Center), Kwang Lee (Oklahoma Blood Institute), Randal Birkelbach (South Texas Blood and Tissue), Geoffrey Belanger (Stanford Blood Center), Dennis Miranda (Blood and Platelet Center, UCLA Health, David Geffen School of Medicine), Craig Beczkiewicz (Versiti), and Marjorie Bravo (Vitalant).

Van Buren NL, Rajbhandary S, Reynolds V, Gorlin JB, Stramer SL, Notari EP IV, et al. Demographics of first‐time donors returning for donation during the pandemic: COVID‐19 convalescent plasma versus standard blood product donors. Transfusion. 2023. 10.1111/trf.17229

REFERENCES

- 1. Glynn SA, Busch MP, Schreiber GB, Murphy EL, Wright DJ, Tu Y, et al. Effect of a national disaster on blood supply and safety: the September 11 experience. JAMA. 2003;289(17):2246–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guo N, Wang J, Ness P. First‐time donors responding to a national disaster may be an untapped resource for the blood centre. Vox Sang. 2012;102:338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tran S, Lewalski EA, Dwyre DM, Hagar Y, Beckett L. Does donating blood for the first time in a national emergency create a better commitment to donating again? Vox Sang. 2010;98:e219–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kracalik I, Mowla S, Katz L, Cumming M, Sapiano MRP, Basavaraju SV. Impact of the early coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on blood utilization in the United States: a time‐series analysis of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network Hemovigilance Module. Transfusion. 2021;61(Suppl 2):S36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. AABB Weekly Report [press release]. Accessed at: https://www.aabb.org/donors-patients/weekly-blood-supply-report.

- 6. Budhai A, Wu AA, Hall L. How did we rapidly implement a convalescent plasma program? Transfusion. 2020;60:1348–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tobian AAR, Cohn CS, Shaz BH. COVID‐19 convalescent plasma. Blood. 2022;140(3):196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jain S, Garg K, Tran SM, Rask IL, Tarczon M, Nandi V, et al. Characteristics of coronavirus disease 19 convalescent plasma donors and donations in the New York metropolitan area. Transfusion. 2021;61(8):2374–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saillant NN, Kornblith LZ, Moore H, Barrett C, Schreiber MA, Cotton BA, et al. The National Blood Shortage‐an Impetus for change. Ann Surg. 2022;275(4):641–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Menitove JE, Reik RA, Cohn CC, Young PP, Fredrick J. Needed resiliency improvements for the national blood supply. Transfusion. 2021;61:2772–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bagot KL, Murray AL, Masser BM. How can we improve retention of the first‐time donor? A systematic review of the current evidence. Transfus Med Rev. 2016;30(2):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moussaoui LS, Blonde J, Chaduc‐Lemoine C, Baldelli S, Desrichard O, Waldvogel S. How to increase first‐time donors' returns? The postdonation letter's content can make a difference. Transfusion. 2022;62(7):1377–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chandler T, Neumann‐Bohme SN, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, et al. Blood donation in times of crisis: early insight into the impact of COVID‐19 on blood donors and their motivation to donate across European countries. Vox Sang. 2021;116:1031–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weidmann C, Derstroff M, Kluter H, Oesterer M, Müller‐Steinhardt M. Motivation, blood donor satisfaction and intention to return during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Vox Sang. 2022;117(4):488–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones JM, Stone M, Sulaeman H, Fink RV, Dave H, Levy ME, et al. Estimated US infection‐ and vaccine‐induced SARS‐CoV‐2 Seroprevalence based on blood donations, July 2020‐may 2021. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1400–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lasky B, Goodhue Meyer E, Steele WR, Crowder LA, Young PP. COVID‐19 convalescent plasma donor characteristics, product disposition, and comparison with standard apheresis donors. Transfusion. 2021;61(5):1471–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cho JH, Rajbhandary S, van Buren NL, Fung MK, Al‐Ghafry M, Fridey JL, et al. The safety of COVID‐19 convalescent plasma donation: a multi‐institutional donor hemovigilance study. Transfusion. 2021;61(9):2668–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mowla SJ, Sapiano MRP, Jones JM, Berger JJ, Basavaraju SV. Supplemental findings of the 2019 National Blood Collection and utilization survey. Transfusion. 2021;61(Suppl 2):S11–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Young PP. AABB Blood Summit: Situation critical! Stabilizing the blood supply during a historic 10+ year low. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8f5xpFVMBQ. 2022.

- 20. Block B. AABB Blood Summit: Donor Data/Analytic Update. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8f5xpFVMBQ. 2022.

- 21. Jones JM, Sapiano MRP, Mowla S, Bota D, Berger JJ, Basavaraju SV. Has the trend of declining blood transfusions in the United States ended? Findings of the 2019 National Blood Collection and utilization survey. Transfusion. 2021;61(Suppl 2):S1–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. ADVANCE study (Assessing Donor Variability and New Concepts in Eligibility) Accessed at: https://advancestudy.org/

- 23. Pandey S, Gorlin JB, Townsend M, van Buren N, Leung JNS, Lee CK, et al. International forum on gender identification and blood collection: responses. Vox Sang. 2022;117(3):E21–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pandey S, Gorlin JB, Townsend M, van Buren N, Leung JNS, Lee CK, et al. International forum on gender identification and blood collection: summary. Vox Sang. 2022;117(3):447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holloway K. Understanding the experiences of plasma donors in Canada's new source plasma collection centres during COVID‐19: a qualitative study. Vox Sang. 2022;117(9):1078–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schreiber GB, Sharma UK, Wright DJ, Glynn SA, Ownby HE, Tu Y, et al. First year donation patterns predict long‐term commitment for first‐time donors. Vox Sang. 2005;88(2):114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]