Key Points

Question

What is the risk of influenza A(H3N2) virus infection among household contacts of patients diagnosed with influenza during the 2021-2022 season compared with influenza seasons before the COVID-19 pandemic?

Findings

In this study of household transmission of influenza A(H3N2) viruses, which included 84 households from the 2021-2022 season and 152 households from 2 seasons prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 50.0% of household contacts were infected during the 2021-2022 season vs 20.1% during prior seasons (adjusted relative risk, 2.31).

Meaning

Among cohorts in 5 US states, there was a significantly increased risk of household transmission of influenza A(H3N2) in 2021-2022 compared with prior seasons.

Abstract

Importance

Influenza virus infections declined globally during the COVID-19 pandemic. Loss of natural immunity from lower rates of influenza infection and documented antigenic changes in circulating viruses may have resulted in increased susceptibility to influenza virus infection during the 2021-2022 influenza season.

Objective

To compare the risk of influenza virus infection among household contacts of patients with influenza during the 2021-2022 influenza season with risk of influenza virus infection among household contacts during influenza seasons before the COVID-19 pandemic in the US.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective study of influenza transmission enrolled households in 2 states before the COVID-19 pandemic (2017-2020) and in 4 US states during the 2021-2022 influenza season. Primary cases were individuals with the earliest laboratory-confirmed influenza A(H3N2) virus infection in a household. Household contacts were people living with the primary cases who self-collected nasal swabs daily for influenza molecular testing and completed symptom diaries daily for 5 to 10 days after enrollment.

Exposures

Household contacts living with a primary case.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Relative risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza A(H3N2) virus infection in household contacts during the 2021-2022 season compared with prepandemic seasons. Risk estimates were adjusted for age, vaccination status, frequency of interaction with the primary case, and household density. Subgroup analyses by age, vaccination status, and frequency of interaction with the primary case were also conducted.

Results

During the prepandemic seasons, 152 primary cases (median age, 13 years; 3.9% Black; 52.0% female) and 353 household contacts (median age, 33 years; 2.8% Black; 54.1% female) were included and during the 2021-2022 influenza season, 84 primary cases (median age, 10 years; 13.1% Black; 52.4% female) and 186 household contacts (median age, 28.5 years; 14.0% Black; 63.4% female) were included in the analysis. During the prepandemic influenza seasons, 20.1% (71/353) of household contacts were infected with influenza A(H3N2) viruses compared with 50.0% (93/186) of household contacts in 2021-2022. The adjusted relative risk of A(H3N2) virus infection in 2021-2022 was 2.31 (95% CI, 1.86-2.86) compared with prepandemic seasons.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among cohorts in 5 US states, there was a significantly increased risk of household transmission of influenza A(H3N2) in 2021-2022 compared with prepandemic seasons. Additional research is needed to understand reasons for this association.

This prospective study compares the risk of transmission of influenza virus infection among household contacts of patients with influenza during the 2021-2022 influenza season vs before the COVID-19 pandemic influenza seasons in the US.

Introduction

In spring 2020, after widespread adoption of measures to mitigate transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, influenza virus circulation in the US declined to historically low levels.1 Antibodies, either naturally acquired or vaccine-induced, are important for the immune response to influenza virus infection but wane over time.2,3,4,5,6 In the absence of periodic exposure, either to seasonal influenza viruses or through vaccination with strains well-matched to circulating viruses each influenza season, population susceptibility to influenza might increase and the return of widespread seasonal influenza transmission may result in large epidemics.7,8,9

Since 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has conducted studies of influenza transmission within households, with protocols that include daily follow-up and detailed contact surveys. These studies were used to test the hypothesis that people who are household contacts of patients with influenza may have greater risk of infection during the 2021-2022 season compared with prepandemic seasons. This study compared the risk of influenza virus infection among household contacts of patients with influenza during the 2021-2022 influenza season with risk of influenza virus infection among household contacts in seasons before the COVID-19 pandemic in the US.

Methods

Study Design

Two case-ascertained household transmission studies for influenza were conducted in the US: one during 2017-2020 in Tennessee and Wisconsin and the second during 2021-2022 in Arizona, New York, North Carolina, and Tennessee. Study protocols and procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute (2017-2020) and Vanderbilt University (2017-2020 and 2021-2022). All enrolled participants provided written or verbal informed consent or assent prior to study activities.

Individuals with laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection (index cases) were identified and recruited from ambulatory clinics, emergency departments, or other settings that performed influenza testing. Index cases with acute illness of less than 5 days’ duration who lived with at least 1 other person who was not currently ill were eligible to participate. The index case and their household contacts were enrolled within 7 days of the index case’s illness onset and followed up for 5 days (2017-2020 in Wisconsin), 7 days (2017-2020 in Tennessee), or 10 days (2021-2022 at all sites). The current analysis was restricted to no more than 7 days of follow-up.

Sample Collection and Surveys

Nasal swabs were self-/parent-collected daily during follow-up and tested for influenza using reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). During 2017-2020, RT-qPCR was conducted at Marshfield Clinic Research Institute and Vanderbilt University using the CDC Human Influenza Virus Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, Influenza A/B Typing Kit with the SuperScript III Platinum One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen) on the StepOnePlus or QuantStudio 6 Flex (Applied Biosystems). Subtyping of influenza A–positive specimens was performed using the CDC Human Influenza Virus Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, Influenza A Subtyping Kit with the SuperScript III Platinum One-Step qRT-PCR Kit System on the MagNA Pure LC 2.0 platform (Roche). For the 2021-2022 season, influenza was detected using the Flu A/B/RSV Assay on the Panther Fusion System (Hologic), an RT-qPCR assay. Whole-genome sequencing was conducted at the University of Michigan to determine influenza virus subtype during the 2021-2022 season.

Questionnaires were administered by study staff or self-administered. Questionnaires measured age, self-reported race, self-reported ethnicity, household characteristics, self-reported medical history, self-reported symptoms in the week prior to enrollment, and self-reported influenza vaccination for the current season. Race and ethnicity data were collected as required for federally funded studies and participants could select all options that applied; race categories included American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, unknown, or prefer not to answer, while ethnicity categories included Hispanic or Latino, not Hispanic or Latino, unknown, or prefer not to answer. At enrollment, all participants reported frequency and type of interaction with every other household member at 2 points: the day before the index case developed symptoms (as a proxy for general contact patterns) and the day before enrollment (after the index case was known to have influenza and was likely infectious). The survey collected information about time spent in the same room as the individual (<1 hour, 1-4 hours, and >4 hours) and whether there was physical contact (eg, touching, hugging, kissing). Influenza vaccination was self-reported at enrollment and was included if both date and location of vaccination were provided. Participants who reported vaccination less than 14 days prior to enrollment or who reported unknown vaccination were considered unvaccinated. The number of people per bedroom in each household (household density) was calculated. Self-administered daily questionnaires measured symptoms during follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were restricted to households affected by influenza A(H3N2) viruses, to contacts who provided nasal swab specimens on at least 4 days, and to household contacts with complete data for covariates of interest. Within a household, the person(s) with influenza virus infection who had the first illness onset was considered the primary case; individuals could be co-primary cases if they shared the same illness onset date with another person in the household. Only contacts from households with a single primary case were included in analyses. Analyses focused on people who were household contacts of the primary case. Characteristics of participants were compared across study periods, using 2-sided Fisher exact tests where P values were reported (P values <.05 were considered significant).

The risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza A(H3N2) virus infection among household contacts was compared by study period (2021-2022 vs prepandemic) using modified Poisson regression and generalized estimating equations to account for household clustering. Estimated relative risks of infection were adjusted for household density, age of the contact, current season influenza vaccination in the contact, and time spent in the same room as the primary case the day before enrollment.

Planned subgroup analyses were conducted by fitting 3 adjusted models with an interaction between study period and age of the household contact, influenza vaccination status of the household contact, or interaction with the primary case (defined by the amount of time the household contact spent in the same room as the primary case after the primary case’s illness onset). Because some sites were not represented across all study periods, a prespecified sensitivity analysis was performed using data from Tennessee, which enrolled participants in both study periods. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted by modeling household infection risk by year (with 2018-2019 season as the reference). Analyses were conducted using R (version 4.0.4).10

Results

Study Population

During 2017-2020, 708 households were enrolled into the influenza virus transmission study and 98 households were enrolled during 2021-2022 (Figure 1). Influenza A(H3N2) viruses were detected during the influenza seasons spanning 2017-2018, 2018-2019, and 2021-2022 (eFigure in Supplement 1). Four contacts (<1% of enrolled participants) were excluded due to missing data on the amount of time spent in the same room as the primary case. No other household contacts were missing covariate data. After applying exclusion criteria, there were 236 households and 539 household contacts included in the analysis (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Figure 1. Inclusion and Exclusion of Households and Individuals in the Case-Ascertained Household Study of Influenza Virus Infection in the US .

Participants (both primary cases and household contacts) in the prepandemic and 2021-2022 seasons were similar with respect to household size, age, and sex (Table; eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Among people who were household contacts, racial and ethnic groups differed significantly between periods (P < .001) and influenza vaccination was significantly lower among people who were household contacts during the 2021-2022 season (P = .008) compared with prepandemic seasons. During the 2021-2022 season, people who were household contacts more frequently reported spending longer periods in the same room as the primary case on the day before enrollment (after the household knew the primary case had influenza virus infection; 72% spent >4 hours with the primary case during the 2021-2022 season vs 56% during the prepandemic seasons, P = .001). These results were consistent between primary cases aged 0 to 17 years with results in primary cases aged 18 and older and were consistent between household contacts aged 0 to 17 years with household contacts aged 18 and older (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). A greater proportion of household contacts reduced interactions during the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 seasons compared with the 2021-2022 season (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). People who were household contacts during the 2021-2022 season also reported significantly more physical contact with the primary case after the primary case’s illness onset (82% vs 62% during prepandemic seasons, P < .001).

Table. Characteristics of Primary Cases and Their Household Contacts Affected by Influenza A(H3N2) Viruses Before the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017-2018 and 2018-2019 Influenza Seasons) and During the 2021-2022 Influenza Season, US.

| No. (%)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021-2022 Influenza season | Prepandemic influenza seasons, 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 | |||

| Primary case | Contact | Primary case | Contact | |

| No. | 84 | 186 | 152 | 353 |

| Household size, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-4.3) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | ||

| Household density, individuals per bedroom, median (IQR) | 1.3 (1.0-2.1) | 1.0 (1.0-1.3) | ||

| State | ||||

| Arizona | 3 (3.6) | 7 (3.8) | ||

| North Carolina | 2 (2.4) | 3 (1.6) | ||

| New York | 43 (51.2) | 102 (54.8) | ||

| Tennessee | 36 (42.9) | 74 (39.8) | 83 (54.6) | 168 (47.6) |

| Wisconsin | 69 (45.4) | 185 (52.4) | ||

| Race and ethnicityb | ||||

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1 (1.2) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (2.6) | 5 (1.4) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 11 (13.1) | 26 (14.0) | 6 (3.9) | 10 (2.8) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 41 (48.8) | 99 (53.2) | 14 (9.2) | 27 (7.6) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 26 (31.0) | 43 (23.1) | 125 (82.2) | 305 (86.4) |

| Multiple races, non-Hispanic | 1 (1.2) | 5 (2.7) | 3 (2.0) | 5 (1.4) |

| Unknown or refused | 4 (4.8) | 11 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Age, y | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 10.0 (5.0-25.0) | 28.5 (11.0-40.0) | 13.0 (8.0-38.0) | 33.0 (11.0-44.0) |

| 0-4 | 17 (20.2) | 11 (5.9) | 19 (12.5) | 26 (7.4) |

| 5-11 | 29 (34.5) | 37 (19.9) | 42 (27.6) | 70 (19.8) |

| 12-17 | 15 (17.9) | 20 (10.8) | 38 (25.0) | 48 (13.6) |

| 18-49 | 15 (17.9) | 95 (51.1) | 28 (18.4) | 157 (44.5) |

| 50-64 | 4 (4.8) | 12 (6.5) | 15 (9.9) | 38 (10.8) |

| ≥65 | 4 (4.8) | 11 (5.9) | 10 (6.6) | 14 (4.0) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 44 (52.4) | 118 (63.4) | 79 (52.0) | 191 (54.1) |

| Male | 40 (47.6) | 68 (36.6) | 73 (48.0) | 162 (45.9) |

| Influenza vaccination | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 43 (51.2) | 101 (54.3) | 72 (47.4) | 149 (42.2) |

| Vaccinated | 41 (48.8) | 85 (45.7) | 80 (52.6) | 204 (57.8) |

| Influenza A(H3N2) virus infection | 84 (100.0) | 93 (50.0) | 152 (100.0) | 71 (20.1) |

| Took influenza antiviralsc | 28 (33.3) | 7 (3.8) | 73 (48.0) | 47 (13.3) |

| Time spent in same room, before symptom onsetd | ||||

| No time or <1 h | 18 (9.7) | 50 (14.2) | ||

| 1-4 h | 34 (18.3) | 84 (23.8) | ||

| >4 h | 134 (72.0) | 219 (62.0) | ||

| Physical contact, before symptom onsete | ||||

| No time spent in the same room | 5 (2.7) | 13 (3.7) | ||

| Time in same room, no physical contact | 22 (11.8) | 68 (19.3) | ||

| Time in same room, with physical contact | 159 (85.5) | 271 (77.0) | ||

| Time spent in same room, after symptom onsetd | ||||

| No time or <1 h | 24 (12.9) | 68 (19.3) | ||

| 1-4 h | 29 (15.6) | 88 (24.9) | ||

| >4 h | 133 (71.5) | 197 (55.8) | ||

| Physical contact, after symptom onset (%)e | ||||

| No time spent in the same room | 5 (2.7) | 14 (4.0) | ||

| Time in same room, no physical contact | 29 (15.6) | 120 (34.0) | ||

| Time in same room, with physical contact | 152 (81.7) | 219 (62.0) | ||

Demographic characteristics of primary cases and their household contacts enrolled during individual seasons (2017-2018, 2018-2019, and 2021-222) are presented in eTable 1 in Supplement 1.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported by participants using closed-ended questions. Participants could choose more than 1 race option.

Influenza antivirals include oseltamivir, baloxavir, zanamivir, and peramivir.

Time spent in the same room as the primary case was reported in closed categories with options as reported here.

Physical contact with the primary case was solicited with the examples (eg, hugging, kissing, touching).

Risk of Infection Among Household Contacts

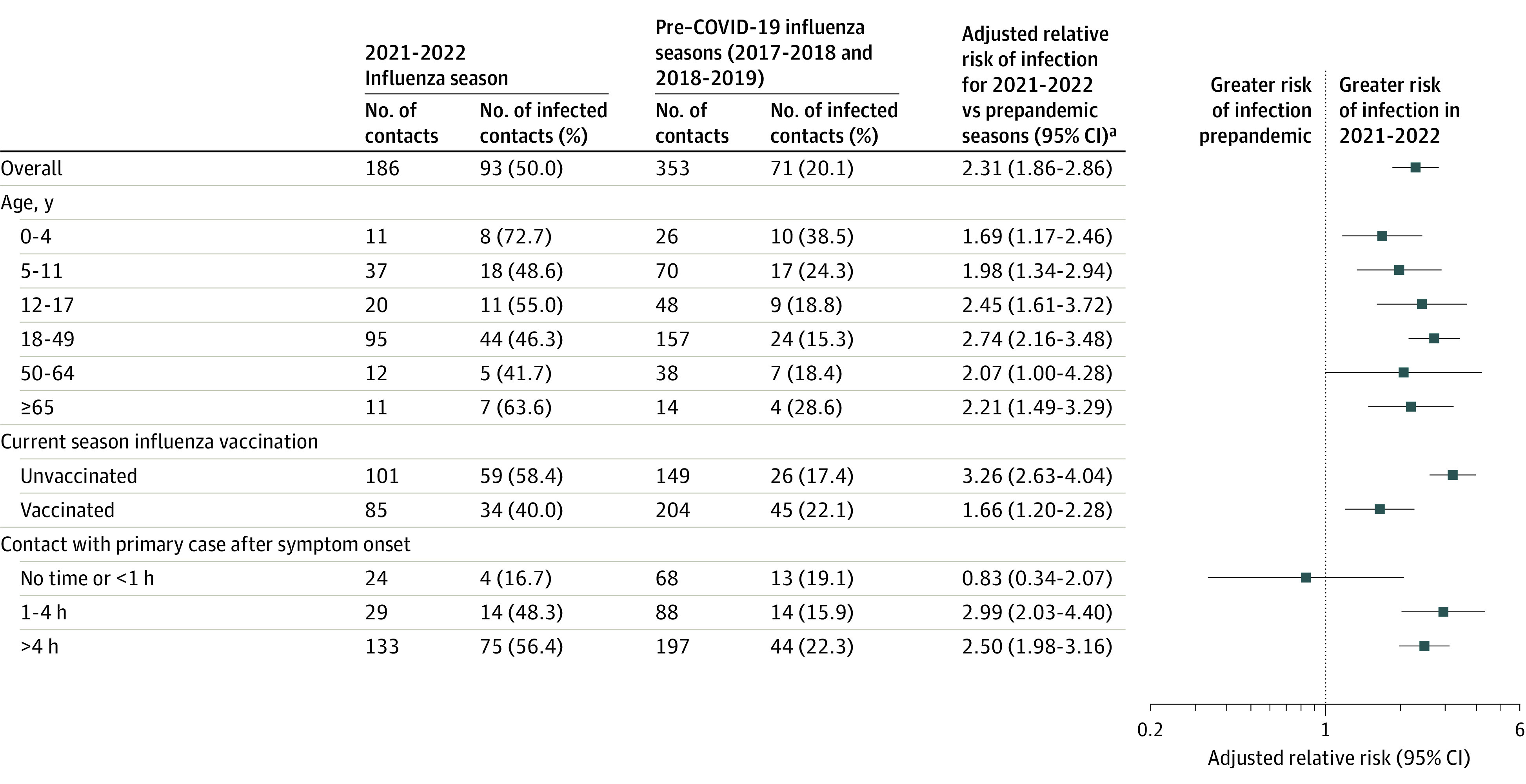

Among people who were household contacts, 20.1% (71/353) were infected during the prepandemic seasons compared with 50.0% (93/186) during the 2021-2022 season (P < .001). During prepandemic seasons, 90.1% of laboratory-confirmed infected contacts reported any symptoms compared with 78.5% of infected contacts from the 2021-2022 season. Of contacts infected during prepandemic seasons, 63.4% reported 2 or more symptoms including fever with cough or sore throat compared with 46.2% of contacts infected during the 2021-2022 season (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Adjusting for the age of the contact, whether the household contact had received the seasonal influenza vaccine, household density, and the amount of interaction the contact had with the primary case after the primary case’s illness onset, the relative risk of laboratory-confirmed A(H3N2) virus infection among household contacts during the 2021-2022 season was 2.31 (95% CI, 1.86-2.86; Figure 2; eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Results were similar when infection risk was examined by season, with significantly higher risk of infection among household contacts during the 2021-2022 season compared with the 2018-2019 season (21.7% in 2018-2019 vs 50.0% in 2021-2022; adjusted relative risk, 2.15 [95% CI, 1.73-2.66]; eTable 7 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Risk of Influenza A(H3N2) Virus Infection Among Household Contacts During the 2021-2022 Influenza Season Compared With Influenza Seasons Before the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017-2018 and 2018-2019).

aRegression models accounted for household clustering and were adjusted for household density, age of the household contact, current season influenza vaccination in the contact, and time spent in the same room as the primary case on the day before study enrollment.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and during the 2021-2022 season, the risk of infection with influenza was highest among household contacts aged younger than 5 years and lowest among household contacts aged 18 to 64 years (Figure 2), though there was no statistically significant modification of the association of study period with household transmission by age. Influenza vaccination among household contacts significantly attenuated the relative increase in infection risk seen in the 2021-2022 season (P for interaction < .001); however, the infection risk among vaccinated household contacts during the 2021-2022 season still remained elevated (40.0%) compared with prepandemic seasons (22.1%) (Figure 2; eTable 6 in Supplement 1). There were also significant differences in infection risk by duration of time spent in the same room as the primary case; the higher risk of infection observed in 2021-2022 occurred primarily among contacts who spent 1 hour or longer in the same room as the primary case the day before enrollment (Figure 2, P for interaction for 1-4 hours of interaction time = .01 and P for >4 hours of interaction time = .02; eTable 6 in Supplement 1).

In a sensitivity analysis restricting the assessment to households enrolled in Tennessee, which enrolled participants with relatively stable demographic characteristics during both study periods (eTable 8 in Supplement 1), there continued to be significantly higher risk of infection during the 2021-2022 season (24% prepandemic vs 43% in 2021-2022; adjusted relative risk, 1.81 [95% CI, 1.18-2.76]).

Discussion

In this study, 50% of household contacts of patients with influenza were infected in 2021-2022 compared with 20% of household contacts during influenza seasons before the COVID-19 pandemic. The significantly increased risk of household infection with influenza during the 2021-2022 season was also higher than estimates reported from other influenza household transmission studies.5,11

There are several potential reasons that the risk of intrahousehold influenza virus infection during the 2021-2022 season was higher than in previous seasons. First, antibodies against influenza, whether naturally acquired or vaccine-induced, may have declined, or waned, over the 3 years since the last time the US population was widely exposed to A(H3N2) viruses in 2018-2019.2,5,12 Seroprevalence studies suggested that approximately 14% of antibodies acquired from infection wane within a year. Therefore, during a 3-year period without substantial population exposure, antibody titers could be considerably lower than initial levels.5

Second, reductions in seasonal influenza vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to increased population susceptibility.9,13 While influenza vaccination was relatively stable since 2019 in the US, with approximately 55% of the US population receiving an influenza vaccination during the 2021-2022 season, there were lower rates of vaccination among children, and there may have been individual-level changes in vaccination behavior not measured by population-level surveys.14

Third, the match between the virus antigens in the annual vaccine and circulating influenza viruses can affect the incidence of seasonal influenza.15,16 The A(H3N2) viruses that circulated during the 2021-2022 season were from a genetic subgroup (3C.2a1b.2a.2, referred to as 2a.2 viruses) that emerged early in 2021 and were antigenically drifted from the A(H3N2) virus included in the 2021-2022 northern hemisphere influenza vaccine.17,18 While laboratory studies show that the 2a.2 viruses may evade neutralization by vaccine-induced antibodies, there was evidence that influenza vaccination during the 2021-2022 season was associated with lower odds of an individual seeking outpatient medical care for an illness by 35%, similar to vaccine effectiveness estimates in prior seasons predominated by influenza A(H3N2) viruses.18,19 In the current household study, the rate of influenza infection during the 2021-2022 season was 40.0% among people who received an influenza vaccine during the 2021-2022 influenza season compared with 58.4% among people who did not receive an influenza vaccine during the 2021-2022 influenza season.

Patterns of population mixing in the US have also changed over the COVID-19 pandemic, with people generally spending more time at home.20,21 More frequent interaction with an infected host would be expected to increase infection risk and, in 2021-2022, household contacts reported spending more time in the same room with others compared with influenza seasons before the pandemic. During the 2021-2022 influenza season, once the household knew the primary case had influenza, household contacts continued to report frequent interaction with the primary case, whereas there was a more pronounced decline in interaction among the enrolled households during the prepandemic seasons. The emergence of the Omicron variant and subvariants of SARS-CoV-2 in the middle of the 2021-2022 influenza season in the US may have prompted readoption of some community mitigation measures, which may have also contributed to greater within-home interactions.22

Since September 2022, there have been increasing influenza virus infections in the US for the 2022-2023 season; circulation of influenza viruses has occurred sooner than in typical prepandemic influenza seasons, with states reporting high numbers of outpatient visits due to influenza-like illness, high rates of influenza-associated hospitalizations, and 79 influenza-associated pediatric deaths as of early January 2023.23 Virologic surveillance suggests that influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) viruses have circulated in the US during the current season23; however, the return of influenza A(H3N2) is concerning given the increased risk of infection observed in this study. The 2022-2023 northern hemisphere influenza vaccine has been updated to include a 2a.2 subgroup virus for the A(H3N2) component and vaccination is the best way to protect against influenza and severe disease.24,25 To prevent influenza virus transmission, individuals who are infected should reduce interactions with other people while they are ill.26 When isolation or reducing interaction is not possible, those infected or those interacting with ill people should consider wearing a high-quality mask to prevent transmission.27 Mitigation measures are particularly important for households with individuals who are at high risk for complications of influenza infection, such as those aged 65 years and older, those with underlying medical conditions, pregnant people, or children younger than 5 years, or individuals who live with someone at high risk.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, households do not reflect contact patterns in the community or work settings. Second, this study was unable to ascertain why there was significantly greater risk of infection in households in 2021-2022. Third, there were substantial differences in age, race, and ethnicity of participants enrolled during the 2021-2022 influenza season compared with participants enrolled prior to the pandemic. It is possible that findings reported here are due to confounding related to these differences. Fourth, it is possible that the differences in geographic sites of enrollment between the study periods might explain some of the differences in infection rates. However, sensitivity analysis restricted to households in Tennessee demonstrated consistent results. Fifth, this study did not analyze immunologic markers that may have better defined susceptibility or immunity to the circulating influenza A(H3N2) viruses. Sixth, because these studies were conducted in a small number of states, results may not be generalizable to other populations. Seventh, seasonal variation in risk of influenza infection has been reported prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with some previously reported estimates of influenza infection risk of approximately 40% to 60%.11 It is possible that the higher rates of infection observed during the 2021-2022 season may reflect these seasonal variations and would have occurred without the COVID-19 pandemic. Eighth, this analysis estimated rates of household infections from follow-up through day 7 after enrollment; however, Wisconsin, which comprised 45.4% of index cases and 52.4% of household contacts in the prepandemic period, only collected nasal samples from household contacts for 5 days, which may have resulted in fewer infections being detected.

Conclusions

Among cohorts in 5 US states, there was a significantly increased risk of household transmission of influenza A(H3N2) in 2021-2022 compared with prepandemic seasons. Additional research is needed to understand reasons for this association.

eFigure. Enrolled Primary Cases With Influenza A/H3N2 Virus Infection in a Case-Ascertained Household Study of Influenza Virus Infection, by Week of Illness Onset

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics of Included Households and Excluded Households Affected by Influenza A/H3N2 Viruses Before the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017/18 and 2018/19 Influenza Seasons) and During the 2021/22 Influenza Season, United States

eTable 2. Demographic Characteristics of Primary Cases and Their Household Contacts Affected by Influenza A/H3N2 Viruses Before the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017/18 and 2018/19 Influenza Seasons) and During the 2021/22 Influenza Season, United States

eTable 3. Frequency and Percentage of Household Contacts Interacting With the Primary Case the Day Before Study Enrollment (Which Occurred After Symptom Onset in the Primary Case)

eTable 4. Interaction Between the Household Contact and the Primary Case on the Day Before Symptom Onset in the Primary Case and the Day Before Study Enrollment (After Symptom Onset in the Primary Case), by Age of the Household Contact, Age of the Primary Case, and Influenza Season (2021/22 Season Compared With Pre-pandemic Seasons in 2017/18 and 2018/19)

eTable 5. Symptoms Reported by Household Contacts With Influenza Virus Infection at Baseline (for the Week Prior to Enrollment) or During Follow-up

eTable 6. Adjusted Relative Risks of Influenza Virus Infection Among Household Contacts of Primary Cases With Influenza A/H3N2 Virus Infection

eTable 7. Adjusted Relative Risks of Influenza Virus Infection Among Household Contacts of Primary Cases With Influenza A/H3N2 Virus Infection by Influenza Season of Enrollment

eTable 8. Demographic Characteristics of Primary Cases and Their Household Contacts Affected by Influenza A/H3N2 Viruses Before the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017/18 and 2018/19 Influenza Seasons) and During the 2021/22 Influenza Season, Tennessee

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Olsen SJ, Winn AK, Budd AP, et al. Changes in influenza and other respiratory virus activity during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, 2020-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(29):1013-1019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7029a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krammer F. The human antibody response to influenza A virus infection and vaccination. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(6):383-397. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0143-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ochiai H, Shibata M, Kamimura K, Niwayama S. Evaluation of the efficacy of split-product trivalent A(H1N1), A(H3N2), and B influenza vaccines: reactogenicity, immunogenicity and persistence of antibodies following two doses of vaccines. Microbiol Immunol. 1986;30(11):1141-1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb03043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potter CW, Clark A, Jennings R, Schild GC, Wood JM, McWilliams PK. Reactogenicity and immunogenicity of inactivated influenza A (H1N1) virus vaccine in unprimed children: report to the Medical Research Council Committee on Influenza and Other Respiratory Virus Vaccines. J Biol Stand. 1980;8(1):35-48. doi: 10.1016/S0092-1157(80)80045-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsang TK, Perera RAPM, Fang VJ, et al. Reconstructing antibody dynamics to estimate the risk of influenza virus infection. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1557. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29310-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zelner J, Petrie JG, Trangucci R, Martin ET, Monto AS. Effects of sequential influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination on antibody waning. J Infect Dis. 2019;220(1):12-19. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krauland MG, Galloway DD, Raviotta JM, Zimmerman RK, Roberts MS. Impact of low rates of influenza on next-season influenza infections. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(4):503-510. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker RE, Park SW, Yang W, Vecchi GA, Metcalf CJE, Grenfell BT. The impact of COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on the future dynamics of endemic infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(48):30547-30553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2013182117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scenario Modeling Hub Team . Technical report: the uncertain burden of COVID-19 and influenza in the upcoming flu season. October 26, 2022. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://raw.githubusercontent.com/midas-network/flu-scenario-modeling-hub/main/reports/technical_report_flu1_covid15.pdf

- 10.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Consulting; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsang TK, Lau LLH, Cauchemez S, Cowling BJ. Household transmission of influenza virus. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(2):123-133. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laurie KL, Rockman S. Which influenza viruses will emerge following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic? Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2021;15(5):573-576. doi: 10.1111/irv.12866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee K, Jalal H, Raviotta JM, et al. Estimating the impact of low influenza activity in 2020 on population immunity and future influenza seasons in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;9(1):ofab607. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Weekly flu vaccination dashboard. Updated April 22, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/dashboard/vaccination-dashboard.html

- 15.Chung JR, Rolfes MA, Flannery B, et al. ; US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network, the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, and the Assessment Branch, Immunization Services Division, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Effects of influenza vaccination in the United States during the 2018-2019 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(8):e368-e376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tenforde MW, Kondor RJG, Chung JR, et al. Effect of antigenic drift on influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States—2019-2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e4244-e4250. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Neher R, Bedford T. Real-time tracking of influenza A/H3N2 evolution. Updated September 1, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://nextstrain.org/flu/seasonal/h3n2/ha/2y

- 18.Bolton MJ, Ort JT, McBride R, et al. Antigenic and virological properties of an H3N2 variant that continues to dominate the 2021-22 northern hemisphere influenza season. Cell Rep. 2022;39(9):110897. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Interim US flu vaccine effectiveness (VE) data for 2021-2022. Updated August 3, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/2021-2022.html

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID data tracker: explore human mobility and COVID-19 transmission in your local area. Updated September 6, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#mobility

- 21.Google . COVID-19 community mobility reports. Updated September 1, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/

- 22.Merced-Morales A, Daly P, Abd Elal AI, et al. Influenza activity and composition of the 2022-23 influenza vaccine—United States, 2021-22 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(29):913-919. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7129a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Weekly US influenza surveillance report. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm

- 24.World Health Organization . Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2022-2023 northern hemisphere influenza season. February 25, 2022. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/recommended-composition-of-influenza-virus-vaccines-for-use-in-the-2022-2023-northern-hemisphere-influenza-season

- 25.Grohskopf LA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices—United States, 2022-23 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(1):1-28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7101a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Preventive steps. Updated August 31, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/prevention.htm

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Types of masks and respirators. Updated September 8, 2022. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/types-of-masks.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Enrolled Primary Cases With Influenza A/H3N2 Virus Infection in a Case-Ascertained Household Study of Influenza Virus Infection, by Week of Illness Onset

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics of Included Households and Excluded Households Affected by Influenza A/H3N2 Viruses Before the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017/18 and 2018/19 Influenza Seasons) and During the 2021/22 Influenza Season, United States

eTable 2. Demographic Characteristics of Primary Cases and Their Household Contacts Affected by Influenza A/H3N2 Viruses Before the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017/18 and 2018/19 Influenza Seasons) and During the 2021/22 Influenza Season, United States

eTable 3. Frequency and Percentage of Household Contacts Interacting With the Primary Case the Day Before Study Enrollment (Which Occurred After Symptom Onset in the Primary Case)

eTable 4. Interaction Between the Household Contact and the Primary Case on the Day Before Symptom Onset in the Primary Case and the Day Before Study Enrollment (After Symptom Onset in the Primary Case), by Age of the Household Contact, Age of the Primary Case, and Influenza Season (2021/22 Season Compared With Pre-pandemic Seasons in 2017/18 and 2018/19)

eTable 5. Symptoms Reported by Household Contacts With Influenza Virus Infection at Baseline (for the Week Prior to Enrollment) or During Follow-up

eTable 6. Adjusted Relative Risks of Influenza Virus Infection Among Household Contacts of Primary Cases With Influenza A/H3N2 Virus Infection

eTable 7. Adjusted Relative Risks of Influenza Virus Infection Among Household Contacts of Primary Cases With Influenza A/H3N2 Virus Infection by Influenza Season of Enrollment

eTable 8. Demographic Characteristics of Primary Cases and Their Household Contacts Affected by Influenza A/H3N2 Viruses Before the COVID-19 Pandemic (2017/18 and 2018/19 Influenza Seasons) and During the 2021/22 Influenza Season, Tennessee

Data Sharing Statement