Key Points

Question

What is the association between inflammation after diagnosis with colon cancer and survival?

Findings

In this cohort study of 1494 patients with stage III colon cancer, 3 canonical inflammatory biomarkers (interleukin 6, soluble tumor necrosis factor α receptor 2, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) were measured 3 to 8 weeks after surgery but before initiation of chemotherapy, and the starting point for survival was date of randomization. Higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers were significantly associated with increased risk of recurrence and mortality, even after adjustment for clinical, pathological, and lifestyle factors.

Meaning

Findings suggest that higher inflammation after diagnosis is significantly associated with worse survival outcomes among patients with stage III colon cancer.

Abstract

Importance

The association of chronic inflammation with colorectal cancer recurrence and death is not well understood, and data from large well-designed prospective cohorts are limited.

Objective

To assess the associations of inflammatory biomarkers with survival among patients with stage III colon cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study was derived from a National Cancer Institute–sponsored adjuvant chemotherapy trial Cancer and Leukemia Group B/Southwest Oncology Group 80702 (CALGB/SWOG 80702) conducted between June 22, 2010, and November 20, 2015, with follow-up ending on August 10, 2020. A total of 1494 patients with plasma samples available for inflammatory biomarker assays were included. Data were analyzed from July 29, 2021, to February 27, 2022.

Exposures

Plasma inflammatory biomarkers (interleukin 6 [IL-6], soluble tumor necrosis factor α receptor 2 [sTNF-αR2], and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hsCRP]; quintiles) that were assayed 3 to 8 weeks after surgery but before chemotherapy randomization.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was disease-free survival, defined as time from randomization to colon cancer recurrence or death from any cause. Secondary outcomes were recurrence-free survival and overall survival. Hazard ratios for the associations of inflammatory biomarkers and survival were estimated via Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

Of 1494 patients (median follow-up, 5.9 years [IQR, 4.7-6.1 years]), the median age was 61.3 years (IQR, 54.0-68.8 years), 828 (55.4%) were male, and 327 recurrences, 244 deaths, and 387 events for disease-free survival were observed. Plasma samples were collected at a median of 6.9 weeks (IQR, 5.6-8.1 weeks) after surgery. The median plasma concentration was 3.8 pg/mL (IQR, 2.3-6.2 pg/mL) for IL-6, 2.9 × 103 pg/mL (IQR, 2.3-3.6 × 103 pg/mL) for sTNF-αR2, and 2.6 mg/L (IQR, 1.2-5.6 mg/L) for hsCRP. Compared with patients in the lowest quintile of inflammation, patients in the highest quintile of inflammation had a significantly increased risk of recurrence or death (adjusted hazard ratios for IL-6: 1.52 [95% CI, 1.07-2.14]; P = .01 for trend; for sTNF-αR2: 1.77 [95% CI, 1.23-2.55]; P < .001 for trend; and for hsCRP: 1.65 [95% CI, 1.17-2.34]; P = .006 for trend). Additionally, a significant interaction was not observed between inflammatory biomarkers and celecoxib intervention for disease-free survival. Similar results were observed for recurrence-free survival and overall survival.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study found that higher inflammation after diagnosis was significantly associated with worse survival outcomes among patients with stage III colon cancer. This finding warrants further investigation to evaluate whether anti-inflammatory interventions may improve colon cancer outcomes.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01150045

This cohort study assesses the association between survival outcomes and levels of inflammatory biomarkers after diagnosis with stage III colon cancer.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer diagnosed in the United States, and more than 50 000 people die from it each year.1 Although chronic inflammation is a well-established pathway for CRC carcinogenesis,2 its impact on CRC prognosis is not well understood, which may result in a missed opportunity to improve cancer outcomes via anti-inflammatory interventions after CRC diagnosis.

To assess inflammatory status, previous studies in CRC prognosis primarily focused on lymphocyte-related measures, such as the ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes, platelets to lymphocytes, and monocytes to lymphocytes, and multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published consequently.3,4,5 These nonspecific inflammatory measures were commonly used in prognosis analyses because lymphocytes affect inflammation via secreting inflammatory cytokines,6 and these measures can be easily derived via complete blood cell count tests that are frequently ordered in the clinic.7 However, because inflammatory cytokines are central in extensive biological networks to regulate inflammation that may affect colon cancer progression,8 studies directly assessing them are urgently needed to inform inflammation and CRC prognosis.

Inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), can activate Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and nuclear factor κB signaling pathways,9,10 which may further promote colon tumor proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis.2 Both IL-6 and TNF-α can induce C-reactive protein (CRP) transcription and secretion in hepatocytes,11 and a CRP test is frequently ordered in the clinic for inflammation assessment that may have potential to predict cancer outcomes.12 In addition, soluble TNF-α receptor 2 (sTNF-αR2) is of high stability and sensitivity in blood samples to surrogate TNF-α,13 and a high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) test is more sensitive than a standard one in detecting lower levels of CRP.14 Therefore, we selected IL-6, sTNF-αR2, and hsCRP as inflammatory biomarkers for this analysis and sought to assess their associations with survival among patients with stage III colon cancer.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

As previously reported,15 2526 patients with stage III colon cancer were enrolled in a National Cancer Institute (NCI)–sponsored, multicenter, double-blinded, phase 3, adjuvant chemotherapy trial between June 22, 2010, and November 20, 2015, in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB; now part of the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology) and Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 80702. In brief, patients with stage III colon cancer were randomly assigned in a 2 × 2 design to (1) fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin for 3 months vs 6 months and (2) daily celecoxib (cyclooxygenase 2 [COX-2] inhibitor; 400 mg) vs placebo for 3 years (trial protocol in Supplement 1).15 There were no statistically significant differences in survival between different treatment groups,15,16 and therefore patients were combined for this analysis. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each participating institution, and all patients provided written informed consent. This cohort study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Inflammatory Biomarkers

As a substudy of CALGB/SWOG 80702, patients were also asked for their consent to collect baseline blood samples for research purposes. Before chemotherapy and 3 to 8 weeks after surgery, nonfasting plasma samples were collected in one 5-mL lavender tube, centrifuged for 10 to 15 minutes at 1300g, and aliquoted into 2-mL cryovials at 0.5 mL per vial. The sample transfer time from blood draw to cryopreservation was less than 5 hours, and the samples were stored in a −80 °C or colder freezer before being shipped on dry ice to Alliance Biorepository at Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio). The samples were cryogenically preserved at a median of 4.8 years (IQR, 3.7-5.9 years) after blood collection and then shipped on dry ice to the central laboratory (Clinical Chemistry Lab, Children’s Hospital of Boston, Boston, Massachusetts) for analysis of plasma inflammatory biomarkers. The assays were conducted from November 28, 2018, to January 14, 2019, for IL-6; from July 29 to October 19, 2018, for sTNF-αR2; and from July 19 to August 19, 2018, for hsCRP. In prior studies, concentrations of these markers were similar in both fasting and nonfasting states,17 did not differ by surgery procedures (open vs laparoscopy),18,19 and returned to basal levels within 1 week after surgery for patients with colon cancer.18,19,20

IL-6 was measured by an ultrasensitive research-grade enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R&D Systems) that has a limit of detection of 0.094 pg/mL; the day-to-day variabilities of the assay at concentrations of 0.49, 2.78, and 5.65 pg/mL are 9.6%, 7.2%, and 6.5%, respectively. sTNF-αR2 was measured by a research-grade ELISA (R&D Systems) that has a limit of detection of 0.6 pg/mL; the day-to-day variabilities of the assay at concentrations of 90, 197, and 444 pg/mL are 5.1%, 3.5%, and 3.6%, respectively. hsCRP was measured with an immunoturbidimetric US Food and Drug Administration–approved diagnostic assay on the Roche Cobas 6000 system (Roche Diagnostics) that has a limit of detection of 0.1 mg/L; the day-to-day variabilities of the assay at concentrations of 0.91, 1.60, and 18.40 mg/L are 3.8%, 3.3%, and 1.9%, respectively. Both IL-6 and sTNF-αR2 were assayed in duplicate, and hsCRP was assayed singly. For IL-6 and sTNF-αR2, 3 levels of quality control were run on each ELISA plate. For hsCRP, 3 levels of quality control were run before the assaying, repeated after every 50 samples, and calibrated again at the end of the day. The central laboratory followed Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments regulations to ensure the values of inflammatory biomarker were in the range; if not, the assay was rejected and repeated.

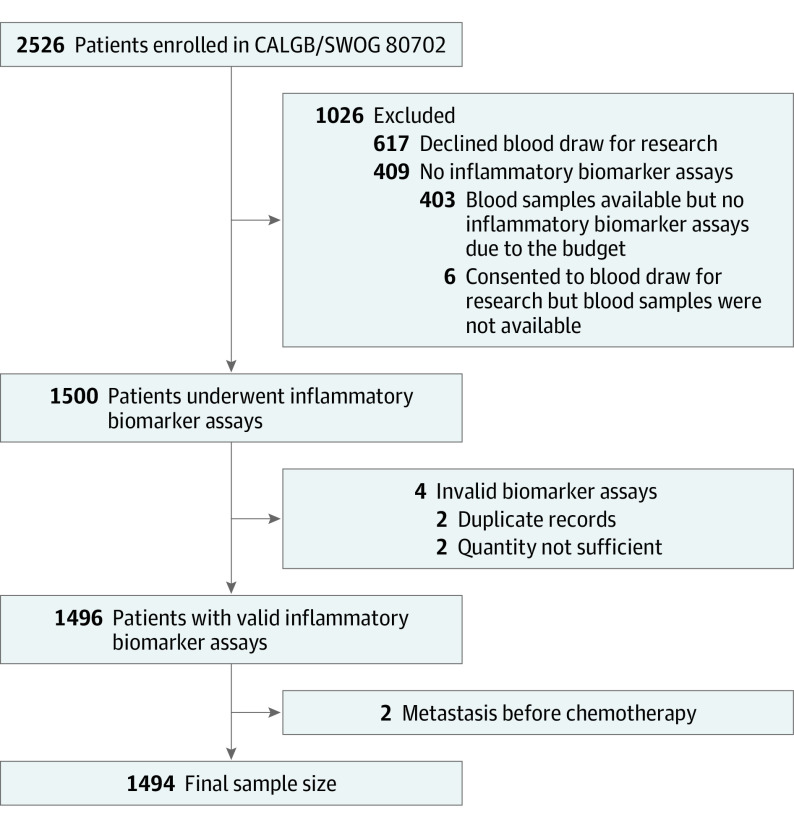

Plasma concentrations of IL-6, sTNF-αR2, and hsCRP were log transformed for analysis, and the results were exponentially transformed back for interpretation. If concentrations were lower than the detection limit, their values were imputed as half of the detection limit.21 Only 3 of the 1494 patients (0.2%) had concentrations lower than the detection limit for hsCRP, and none for IL-6 and sTNF-αR2. If blood specimens were reported as quantity not sufficient, the corresponding patients were excluded. Figure 1 represents the derivation of the final population of 1494 patients. Compared with patients who were not included, the study population was more likely to be White and non-Hispanic and have a lower T category (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Patients in CALGB/SWOG 80702 for Analysis of Inflammatory Biomarkers and Colon Cancer Survival.

CALGB indicates Cancer and Leukemia Group B; SWOG, Southwest Oncology Group.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was disease-free survival, defined as the time from randomization to colon cancer recurrence or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Secondary outcomes were recurrence-free survival (time from randomization to colon cancer recurrence) and overall survival (time from randomization to death from any cause). All patients were followed up through August 10, 2020.

Patient Characteristics

The following patient characteristics were collected through medical notes and clinical examinations of the participating institutions and the Alliance Pathology Coordinating Laboratory: age, sex, race, ethnicity, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, bowel wall invasion (T category), nodal stage (N category), tumor location, and body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Statistical Analysis

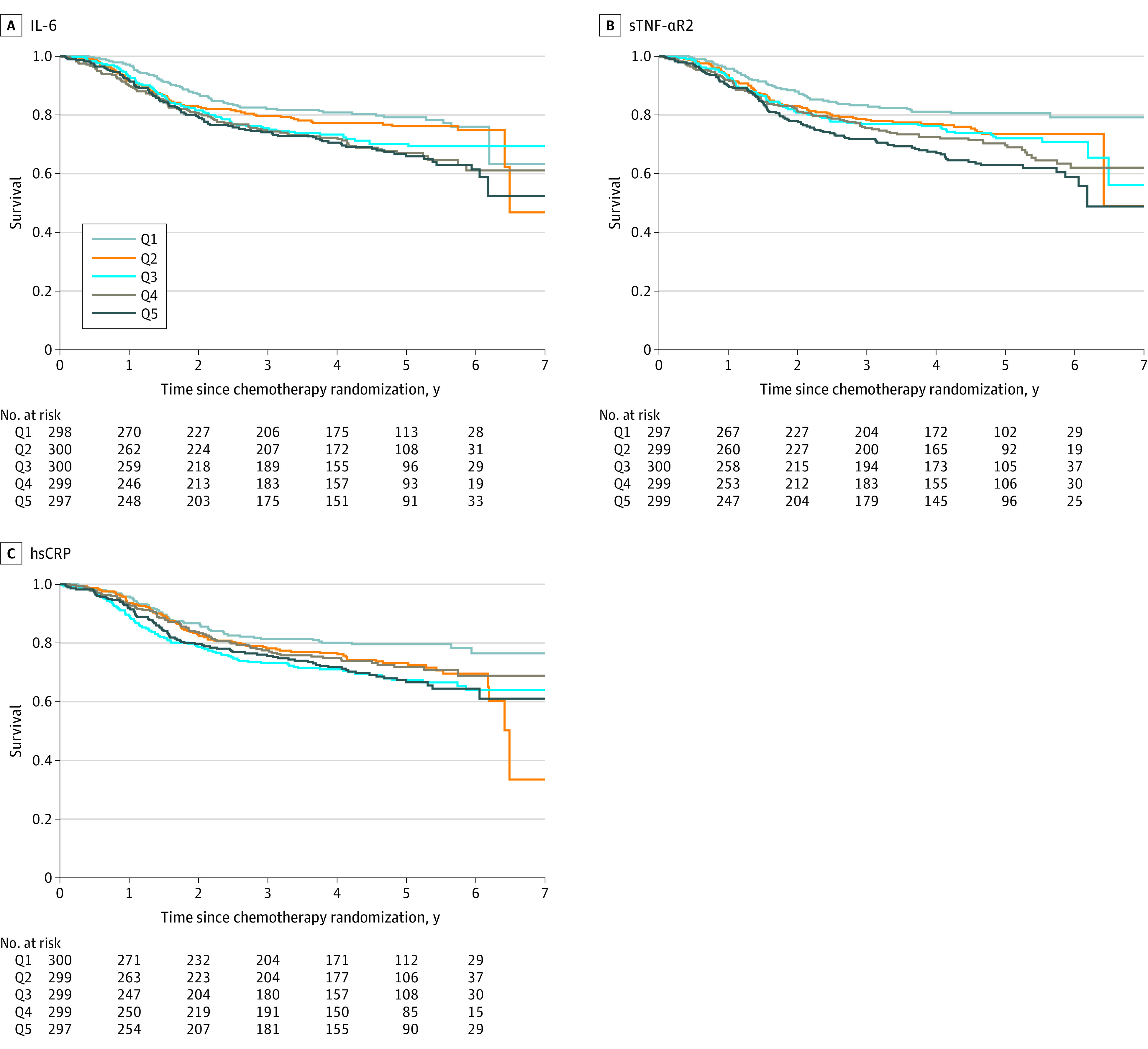

Patient characteristics were summarized and compared by quintiles of inflammatory biomarkers (IL-6, sTNF-αR2, and hsCRP), with the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Spearman correlations (rS) within 3 inflammatory biomarkers were also calculated.22 Differences in disease-free survival, recurrence-free survival, and overall survival between quintiles were assessed via the Kaplan-Meier estimator and the log-rank test (Figure 2).23,24

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimates for Disease-Free Survival by Quintiles (Q1-Q5) of Inflammatory Biomarkers Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer.

Disease-free survival by quintiles of interleukin 6 (IL-6) (A), soluble tumor necrosis factor α receptor 2 (sTNF-αR2) (B), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) (C). P values for each inflammatory biomarker were calculated with the log-rank test: IL-6 (P = .005), sTNF-αR2 (P < .001), and hsCRP (P = .02).

We applied Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for the associations of inflammatory biomarkers (quintiles) with disease-free survival, recurrence-free survival, and overall survival.25 We used the plasma level as a continuous variable to conduct all trend tests. Considering biological plausibility and change-in-estimate criteria (10% cutoff),26,27 the following were considered as potential covariates: age (years), sex (male or female), race (Asian, Black, White, and other), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0 or 1-2), T category (T1-T2, T3, or T4), N category (N1 or N2), tumor location (left side, right side, or multiple), BMI (<18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25.0-29.9, and ≥30), time between surgery and blood draw (months), blood sample storage time (months), and trial group (celecoxib or placebo). Race and ethnicity were self-reported, and participants who did not self-identify as Asian, Black, or White were classified as other for race. Missing data were substituted with median values of continuous variables and most frequent values of categorical variables,28 and less than 0.5% of patients had missing data for covariates. We used the Schoenfeld residuals method to test proportional hazards assumption and did not detect violations.29

Patients were also invited to complete a self-administered questionnaire during adjuvant therapy to assess their postdiagnosis diet and lifestyle, and 1142 of 1494 (76.4%) returned valid questionnaires. For sensitivity analysis, we additionally adjusted for diet quality (measured by the Western dietary pattern score as previously described30), smoking (never, past, and current), low-dose aspirin use (yes or no), and physical activity (measured by metabolic equivalent task hours per week: 0-2.9, 3-8.9, 9-17.9, and ≥18).

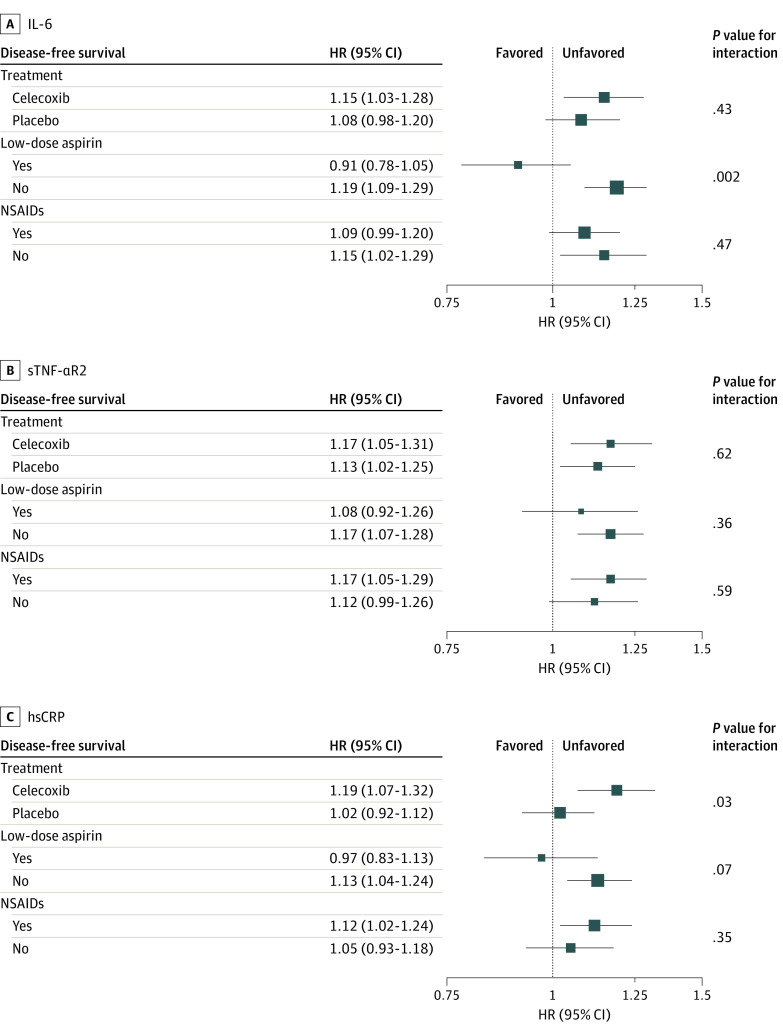

For subgroup analysis, because CALGB/SWOG 80702 was designed to test the efficacy of celecoxib on disease-free survival while permitting low-dose aspirin use, we were particularly interested in how the associations of inflammatory biomarkers with disease-free survival may differ by treatment groups (celecoxib vs no), low-dose aspirin use (yes vs no), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use (yes vs no). If patients were randomly assigned to celecoxib or took low-dose aspirin, they were considered as using NSAIDs; otherwise, they were not. We considered inflammatory biomarkers (quintiles) as ordinal variables, and their quintile levels (1 through 5) corresponded to the equivalent integer value (1 through 5). We performed stratified analyses to estimate adjusted HRs of inflammatory biomarkers by the increase of 1 quintile and tested P value for interaction by using likelihood ratio tests.31 More information about subgroup analysis modeling is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Adjusted Associations of Interleukin 6 (IL-6), Soluble Tumor Necrosis Factor α Receptor 2 (sTNF-αR2), and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hsCRP) With Disease-Free Survival Stratified by Treatment Group, Low-Dose Aspirin Use, and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug (NSAID) Use.

Associations were adjusted for age (years), sex (male or female), race (Asian, Black, White, and other [participants who did not self-identify as Asian, Black, or White were classified as other for race]), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0 or 1-2), T category (T1-T2, T3, or T4), N category (N1 or N2), tumor location (left side, right side, or multiple), body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; <18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25.0-29.9, and ≥30), time between surgery and blood draw (months), blood sample storage time (months), stratified factor, and the interaction term inflammatory biomarker × stratified factor with Cox proportional hazards regression. For treatment and low-dose aspirin models, treatment and low-dose aspirin were both included to adjust mutually. The P value for interaction was assessed with likelihood ratio tests. Inflammatory biomarkers were evaluated as ordinal variables, and each level (quintile [Q]) corresponded to the equivalent integer (from Q1 through Q5). The hazard ratios (HRs) in the plot refer to the estimates of a quintile increase for inflammatory biomarkers. If patients were randomly assigned to celecoxib or took low-dose aspirin, they were considered as taking NSAIDs; otherwise, they were considered as not taking NSAIDs.

Data collection and statistical analyses were conducted by the Alliance Statistics and Data Management Center. Data quality was ensured by the center and by the study chairperson following Alliance policies. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) and R, version 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) from July 29, 2021, to February 27, 2022. All P values were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. For subgroup analysis, multiple comparisons were adjusted with Bonferroni correction,32 for which P < .006 (ie, .05/9) was considered statistically significant. Point estimates were presented with 95% CIs.

Results

Of 1494 patients (median follow-up, 5.9 years [IQR, 4.7-6.1 years]), we observed 327 recurrences, 244 deaths, and 387 events for disease-free survival. Of these patients (Table 1), the median age was 61.3 years (IQR, 54.0-68.8 years), 828 were male (55.4%), 666 were female (44.6%), 52 were Asian (3.5%), 163 were Black (10.9%), 82 were Hispanic (5.5%), 1412 were non-Hispanic (94.5%), 1230 were White (82.3%), and 49 were of other race (3.3%). Plasma samples were collected at a median of 6.9 weeks (IQR, 5.6-8.1 weeks) after surgery and 6 days (IQR, 3-12 days) before chemotherapy randomization (ie, day 1 of cycle 1 of chemotherapy). The median plasma concentration was 3.8 pg/mL (IQR, 2.3-6.2 pg/mL) for IL-6, 2.9 × 103 pg/mL (IQR, 2.3-3.6 × 103 pg/mL) for sTNF-αR2, and 2.6 mg/L (IQR, 1.2-5.6 mg/L) for hsCRP. The correlations (rS) were 0.40 (P < .001) for IL-6 and sTNF-αR2, 0.55 (P < .001) for IL-6 and hsCRP, and 0.30 (P < .001) for sTNF-αR2 and hsCRP.

Table 1. Characteristics of 1494 Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer in CALGB/SWOG 80702.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 61.3 (54.0-68.8) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 828 (55.4) |

| Female | 666 (44.6) |

| Raceb | |

| Asian | 52 (3.5) |

| Black | 163 (10.9) |

| White | 1230 (82.3) |

| Other | 49 (3.3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 82 (5.5) |

| Non-Hispanic | 1412 (94.5) |

| ECOG performance statusc | |

| 0 | 1076 (72.0) |

| 1-2 | 418 (28.0) |

| Bowel wall invasion by T categoryd | |

| T1-T2 | 290 (19.4) |

| T3 | 984 (65.9) |

| T4 | 209 (14.0) |

| Missing | 11 (0.7) |

| Nodal categorye | |

| N1 | 1090 (73.0) |

| N2 | 392 (26.2) |

| Missing | 12 (0.8) |

| Tumor location | |

| Left side | 716 (47.9) |

| Right side | 754 (50.5) |

| Multiple | 7 (0.5) |

| Missing | 17 (1.1) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 28.0 (24.6-32.2) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; SWOG, Southwest Oncology Group.

Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Participants who did not self-identify as Asian, Black, or White were classified as other for race.

ECOG performance status: 0, fully active, able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction; 1, restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out light work; 2, ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities, awake and ambulatory more than 50% of waking hours.

Bowel wall invasion: T1, tumor has grown into the submucosa; T2, into the muscularis propria; T3, through the muscularis propria and into the subserosa; and T4, into the surface of the visceral peritoneum or into or has attached to other organs or structures.

Nodal stage: N1, 1 to 3 lymph nodes tested positive for cancer; N2, 4 or more lymph nodes tested positive.

Compared with those in the lowest quintile of IL-6, patients in the highest quintile of IL-6 were more likely to be older, self-identify as non-Hispanic, have a worse performance status, and have more right-sided tumors and a higher BMI (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Compared with those in the lowest quintile of sTNF-αR2, patients in the highest quintile of sTNF-αR2 were more likely to be older, self-identify as White and non-Hispanic, have a worse performance status, and have a higher T category, more right-sided tumors, and a higher BMI. Compared with those in the lowest quintile of hsCRP, patients in the highest quintile of hsCRP were more likely to self-identify as Black, have a worse performance status, and have more right-sided tumors and a higher BMI.

Patient Outcomes

Regardless of inflammatory biomarker types, compared with those in the lowest quintile of inflammation, patients in the highest quintile of inflammation had worse disease-free survival (Figure 2). The estimated percentage point difference ranged from 12.9% (hsCRP) to 17.6% (sTNF-αR2) for the 5-year disease-free survival rate (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). We observed similar patterns for recurrence-free survival and overall survival (eTable 3 and eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 2).

Among all inflammatory biomarker types, compared with those in the lowest quintile of inflammation, patients in the highest quintile of inflammation had an unadjusted higher risk of recurrence and mortality (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). After multivariable adjustment (Table 2), the associations remained statistically significant for disease-free survival (IL-6: adjusted HR, 1.52 [95% CI, 1.07-2.14]; P = .01 for trend; sTNF-αR2: adjusted HR, 1.77 [95% CI, 1.23-2.55]; P < .001 for trend; and hsCRP: adjusted HR, 1.65 [95% CI, 1.17-2.34]; P = .006 for trend). We observed similar patterns for recurrence-free survival and overall survival (Table 2 and eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Elevated inflammation was associated with higher risk of recurrence (IL-6: adjusted HR, 1.68 [95% CI, 1.07-2.65]; P = .08 for trend; sTNF-αR2: adjusted HR, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.04-2.28]; P = .001 for trend; and hsCRP: adjusted HR, 1.73 [95% CI, 1.11-2.68]; P = .03 for trend) and increased risk of mortality (IL-6: adjusted HR, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.05-2.25]; P = .03 for trend; sTNF-αR2: adjusted HR, 2.33 [95% CI, 1.40-3.89]; P = .02 for trend; and hsCRP: adjusted HR, 1.56 [95% CI, 1.07-2.26]; P = .003 for trend).

Table 2. Adjusted Associations of Inflammatory Biomarkers With Survival Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancera.

| Survivalb | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | P value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease free | ||||||

| IL-6 | 1 [Reference] | 1.12 (0.79-1.60) | 1.36 (0.96-1.92) | 1.46 (1.03-2.06) | 1.52 (1.07-2.14) | .01 |

| sTNF-αR2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.20 (0.83-1.73) | 1.44 (1.00-2.07) | 1.57 (1.09-2.27) | 1.77 (1.23-2.55) | <.001 |

| hsCRP | 1 [Reference] | 1.34 (0.95-1.89) | 1.61 (1.14-2.26) | 1.25 (0.88-1.79) | 1.65 (1.17-2.34) | .006 |

| Recurrence free | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| IL-6 | 1 [Reference] | 1.42 (0.90-2.26) | 1.56 (0.98-2.47) | 1.50 (0.94-2.37) | 1.68 (1.07-2.65) | .08 |

| sTNF-αR2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.14 (0.78-1.66) | 1.29 (0.88-1.88) | 1.49 (1.01-2.18) | 1.54 (1.04-2.28) | .001 |

| hsCRP | 1 [Reference] | 1.27 (0.81-1.99) | 1.70 (1.10-2.63) | 1.20 (0.76-1.90) | 1.73 (1.11-2.68) | .03 |

| Overall | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| IL-6 | 1 [Reference] | 1.32 (0.91-1.93) | 1.46 (1.00-2.14) | 1.57 (1.07-2.30) | 1.54 (1.05-2.25) | .03 |

| sTNF-αR2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.56 (0.93-2.62) | 1.92 (1.15-3.19) | 1.93 (1.16-3.22) | 2.33 (1.40-3.89) | .02 |

| hsCRP | 1 [Reference] | 1.27 (0.88-1.84) | 1.62 (1.13-2.33) | 1.20 (0.82-1.76) | 1.56 (1.07-2.26) | .003 |

Abbreviations: hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; Q, quintile; sTNF-αR2, soluble tumor necrosis factor α receptor 2.

Data are presented as adjusted hazard ratios (95% CIs).

Adjusted for age (years), sex (male or female), race (Asian, Black, White, and other [participants who did not self-identify as Asian, Black, or White were classified as other for race]), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0 or 1-2), T category (T1-T2, T3, or T4), N category (N1 or N2), tumor location (left side, right side, or multiple), body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; <18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25.0-29.9, and ≥30), time between surgery and blood draw (months), blood sample storage time (months), and treatment arm (celecoxib or placebo).

Sensitivity Analysis

For sensitivity analysis (eTable 5 in Supplement 2), the associations of inflammatory biomarkers and survival were attenuated, but most remained statistically significant after additional adjustment for diet and lifestyle.

Subgroup Analysis

We did not observe a significant interaction between any inflammatory marker and celecoxib vs placebo randomization (Figure 3) after correcting for multiple comparisons in which significance was defined as P < .006. In contrast, we observed 1 significant interaction between IL-6 and baseline low-dose aspirin use. The association of higher IL-6 with disease-free survival was positive and significant among patients not taking low-dose aspirin (adjusted HR, 1.19 [95% CI, 1.09-1.29]) but negative and not significant for those taking low-dose aspirin (adjusted HR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.78-1.05]) (P = .002).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of patients with stage III colon cancer, we found that higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers (IL-6, sTNF-αR2, and hsCRP) after colon cancer diagnosis were significantly associated with increased risk of recurrence and mortality, even after adjustment for clinical, pathological, and lifestyle factors. This was a large study using 3 canonical inflammatory biomarkers to assess the associations of inflammation with colon cancer survival.

Among 12 studies estimating the associations of postdiagnosis IL-6 with CRC survival,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 there were 10 studies with limited sample size (<250) that reported inconsistent associations of IL-6 with recurrence and mortality.34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 In addition, 7 of these 10 studies36,37,38,39,40,41,43 recruited all their patients before 2003, when laparoscopy and fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin were approved as effective for colon cancer treatment.45,46 As for sTNF-αR2 (or TNF-α), a similar pattern was observed: the majority of studies were small and reported inconsistent associations with recurrence and mortality.35,39,43,44,47 There were 2 CRC prognosis studies with larger sample sizes (>250) for assessing IL-6, TNF-α, or both. First, 306 patients with stage II to III CRC diagnosed between 1998 and 2007 were identified through the Seattle Colon Cancer Family Registry, and their blood samples were collected at a median of 9.5 months after diagnosis.33 Higher IL-6 level (highest vs lowest quartile) was reported to be associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 2.72 [95% CI, 2.07-3.56]) and cancer-specific mortality (HR, 5.02 [95% CI, 2.92-8.59]).33 Second, 747 patients with stage I to III CRC diagnosed between 2012 and 2016 were identified through 2 Netherlands prospective cohorts and their blood samples were obtained at diagnosis and 6 months afterward.35 Higher IL-6 level at diagnosis or afterward (highest vs lowest tertile) was not associated with increased risk of recurrence (at diagnosis: HR, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.87-1.28]; after diagnosis: HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 0.94-1.45]) and all-cause mortality (at diagnosis: HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 0.98-1.38]; after diagnosis: HR, 1.09 [95% CI, 0.78-1.38]).35 A similar finding was also observed for TNF-α, and higher TNF-α level at diagnosis was not associated with increased risk of recurrence (HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.51-1.25]) and mortality (HR, 1.30 [95% CI, 0.89-1.92]), nor was TNF-α level after diagnosis (HR for recurrence, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.53-1.61]; HR for mortality, 1.59 [95% CI, 0.93-2.70]).35 Beyond previous reports, our study had the largest sample size to date, recruited patients of diverse race and ethnicity, and was derived from a recently completed NCI-sponsored adjuvant chemotherapy trial, in which patients received up-to-date effective surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy. As for hsCRP, multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated CRP or CRP-focused measures (such as Glasgow prognostic score and ratio of CRP to albumin) and CRC prognosis.48,49,50 In line with previous studies,48,49,50 we reported that higher inflammation measured by hsCRP was significantly associated with colon cancer recurrence and mortality. To conclude, we reported that higher inflammation after diagnosis was significantly associated with colon cancer recurrence and mortality, and our measurement timing (after surgery but before chemotherapy) may help clinicians monitor postoperative inflammation for better cancer outcomes and prepare for incoming chemotherapy-enhanced inflammation. These findings are important to inform the role of inflammation in colon cancer prognosis among patients receiving up-to-date cancer treatment.

The use of NSAIDs (celecoxib, aspirin, and other COX inhibitors) has not consistently shown significant reduction in inflammatory biomarkers.51,52,53,54,55 However, NSAIDs still play a pivotal role in regulating inflammation resolution so that the association of inflammatory biomarkers with CRC survival may be modified by NSAID use,56 and few prognosis studies have investigated such stratified associations. Although we did not observe a significant interaction between inflammatory markers and celecoxib vs placebo randomization, we did observe an increased risk of recurrence and mortality among individuals with higher IL-6 level while not using low-dose aspirin. Preclinical research suggested that aspirin can induce colon cell apoptosis and suppress the JAK/STAT3 (IL-6) signaling pathway,57 and a recent meta-analysis suggested that aspirin use is associated with improved survival among patients with CRC.58 It is unclear why a differential association was observed for celecoxib (selective COX-2 inhibitor) vs aspirin (nonselective COX inhibitor), and more preclinical and clinical studies are needed to elucidate this difference. However, as an exploratory study, our subgroup findings still contribute importantly to identifying patients with CRC at higher risk of recurrence and mortality through low-dose aspirin use.

As a result of inflammation, hyperactivation of JAK/STAT3 (IL-6) and nuclear factor κB (TNF-α) signaling pathways can facilitate colon tumor progression, immune suppression, and treatment resistance.9,10,59,60 In addition, IL-6 and TNF-α can induce the hepatic synthesis of CRP11 that can further result in elevated systemic inflammation and worse colon cancer outcomes.48,49,50 Thus, anti-inflammatory interventions could be promising to provide therapeutic benefits for patients with colon cancer by directly inhibiting tumor growth and stimulating antitumor immunity. Although the trial CALGB/SWOG 80702 used for this analysis suggested that the addition of celecoxib (selective COX-2 inhibitor) to standard adjuvant chemotherapy did not significantly improve colon cancer survival,15 diet, physical activity, smoking, obesity, aspirin use, and other lifestyle factors, which are key regulators of inflammation, have been consistently reported to be associated with colon cancer prognosis.30,58,61,62,63,64,65 Although the effects of each diet and lifestyle factor in isolation on prognosis may be small, the combined effect of these factors promises to substantially reduce recurrence and mortality. This aligns with our sensitivity analysis results, which showed that the associations of inflammatory biomarkers with survival were attenuated after adjustment for diet and lifestyle. However, our findings still suggest that higher levels of inflammation after diagnosis were significantly associated with colon cancer recurrence and mortality.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it did not use a comprehensive panel of inflammation-related proteins and may not inclusively assess every inflammatory aspect. However, this analysis was focused on key inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, sTNF-αR2, and hsCRP) and these biomarkers have been widely used across different populations for general inflammation assessment.66,67,68 Second, for subgroup analysis, the possibility of a false-positive result may increase owing to testing of multiple hypotheses, but we used Bonferroni correction to counter this problem. Considering that NSAIDs are one of the most commonly used drugs in the United States and the rest of the world,69,70,71 our exploratory analysis underscores the importance of using inflammatory biomarkers for identifying colon cancer subgroups at higher risk of recurrence and mortality. Such findings need to be further confirmed by analyses of other independent studies. Third, in the multivariable analysis, we did not adjust for other tumor biology biomarkers such as KRAS, BRAF, and microsatellite instability or stability status, testing for which is now frequently ordered in the clinic. Both KRAS and BRAF mutations and microsatellite stability were reported to be significantly associated with increased risk of recurrence and mortality after colon cancer diagnosis.72,73 Fourth, causes of death were not available; thus, we could not analyze the causes that may be associated with excess events for disease-free survival or overall survival. Fifth, patients in our study had primarily stage III cancer; further evaluation of inflammation and colon cancer prognosis in other stages (I, II, and IV) is warranted. In addition, recent developments regarding other biomarkers such as circulating tumor DNA have shown that they perform well in predicting colon cancer recurrence74,75; therefore, future studies may compare the performance of different biomarkers in predicting recurrence and death among patients with colon cancer.

Conclusions

Our findings from a large, well-designed, prospective cohort study provide compelling observational evidence that higher inflammation after diagnosis was significantly associated with worse survival among patients with stage III colon cancer. Further investigation is warranted to evaluate whether anti-inflammatory interventions may improve colon cancer outcomes.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Factors Between Patients Included in vs Excluded From the Biomarker Cohort

eTable 2. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Colon Cancer Patients by Quintiles of Inflammatory Biomarkers

eTable 3. Five-Year Survival From the Kaplan-Meier Estimator by Quintiles of Inflammatory Biomarkers

eFigure 1. Kaplan-Meier Estimates for Recurrence-Free Survival by Quintiles of Inflammatory Biomarkers Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

eFigure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimates for Overall Survival by Quintiles of Inflammatory Biomarkers Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

eTable 4. Unadjusted Associations of Inflammatory Biomarkers With Survival Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis of Incorporating Diet and Lifestyle Factors for Adjusted Associations of Inflammatory Biomarkers With Survival Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terzić J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, Karin M. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2101-2114. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haram A, Boland MR, Kelly ME, Bolger JC, Waldron RM, Kerin MJ. The prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer: a systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115(4):470-479. doi: 10.1002/jso.24523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan D, Fu Y, Tong W, Li F. Prognostic significance of lymphocyte to monocyte ratio in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;55:128-138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng HX, Lin K, He BS, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio could be a promising prognostic biomarker for survival of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. FEBS Open Bio. 2016;6(7):742-750. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis DE, Blutt SE. Organization of the immune system. In: Rich RR, Fleisher TA, Shearer WT, Schroeder HW, Frew AJ, Weyand CM, eds. Clinical Immunology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2019:19-38. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7020-6896-6.00002-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tefferi A, Hanson CA, Inwards DJ. How to interpret and pursue an abnormal complete blood cell count in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(7):923-936. doi: 10.4065/80.7.923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao H, Wu L, Yan G, et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):263. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00658-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2:17023. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(4):234-248. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhodes B, Fürnrohr BG, Vyse TJ. C-reactive protein in rheumatology: biology and genetics. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(5):282-289. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart PC, Rajab IM, Alebraheem M, Potempa LA. C-reactive protein and cancer—diagnostic and therapeutic insights. Front Immunol. 2020;11:595835. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.595835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruggeman LA, Drawz PE, Kahoud N, Lin K, Barisoni L, Nelson PJ. TNFR2 interposes the proliferative and NF-κB–mediated inflammatory response by podocytes to TNF-α. Lab Invest. 2011;91(3):413-425. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Windgassen EB, Funtowicz L, Lunsford TN, Harris LA, Mulvagh SL. C-reactive protein and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: an update for clinicians. Postgrad Med. 2011;123(1):114-119. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2011.01.2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyerhardt JA, Shi Q, Fuchs CS, et al. Effect of celecoxib vs placebo added to standard adjuvant therapy on disease-free survival among patients with stage III colon cancer: the CALGB/SWOG 80702 (Alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(13):1277-1286. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grothey A, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1177-1188. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milan AM, Pundir S, Pileggi CA, Markworth JF, Lewandowski PA, Cameron-Smith D. Comparisons of the postprandial inflammatory and endotoxaemic responses to mixed meals in young and older individuals: a randomised trial. Nutrients. 2017;9(4):354. doi: 10.3390/nu9040354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehigan BJ, Hartley JE, Drew PJ, et al. Changes in T cell subsets, interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein after laparoscopic and open colorectal resection for malignancy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(11):1289-1293. doi: 10.1007/s004640020021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ordemann J, Jacobi CA, Schwenk W, Stösslein R, Müller JM. Cellular and humoral inflammatory response after laparoscopic and conventional colorectal resections. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(6):600-608. doi: 10.1007/s004640090032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujii T, Tabe Y, Yajima R, Tsutsumi S, Asao T, Kuwano H. Relationship between C-reactive protein levels and wound infections in elective colorectal surgery: C-reactive protein as a predictor for incisional SSI. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58(107-108):752-755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lubin JH, Colt JS, Camann D, et al. Epidemiologic evaluation of measurement data in the presence of detection limits. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(17):1691-1696. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spearman C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(5):1137-1150. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant test procedures. J R Stat Soc A. 1972;135(2):185-198. doi: 10.2307/2344317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric-estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457-481. doi: 10.2307/2281868 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34(2):187-220. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(11):923-936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125-137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression-model. Biometrika. 1982;69(1):239-241. doi: 10.2307/2335876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Association of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2007;298(7):754-764. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casella G, Berger RL. Statistical Inference. Duxbury; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34(5):502-508. doi: 10.1111/opo.12131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hua X, Kratz M, Malen RC, et al. Association between post-treatment circulating biomarkers of inflammation and survival among stage II-III colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2021;125(6):806-815. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01458-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varkaris A, Katsiampoura A, Davis JS, et al. Circulating inflammation signature predicts overall survival and relapse-free survival in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;120(3):340-345. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0360-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wesselink E, Balvers MGJ, Kok DE, et al. Levels of inflammation markers are associated with the risk of recurrence and all-cause mortality in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(6):1089-1099. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hermunen K, Soveri L-M, Boisen MK, et al. Postoperative serum CA19-9, YKL-40, CRP and IL-6 in combination with CEA as prognostic markers for recurrence and survival in colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(12):1416-1423. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1800086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh KY, Li YY, Hsieh LL, et al. Analysis of the effect of serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble IL-6 receptor levels on survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40(6):580-587. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belluco C, Nitti D, Frantz M, et al. Interleukin-6 blood level is associated with circulating carcinoembryonic antigen and prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(2):133-138. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0133-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rich T, Innominato PF, Boerner J, et al. Elevated serum cytokines correlated with altered behavior, serum cortisol rhythm, and dampened 24-hour rest-activity patterns in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(5):1757-1764. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galizia G, Orditura M, Romano C, et al. Prognostic significance of circulating IL-10 and IL-6 serum levels in colon cancer patients undergoing surgery. Clin Immunol. 2002;102(2):169-178. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung YC, Chang YF. Serum interleukin-6 levels reflect the disease status of colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83(4):222-226. doi: 10.1002/jso.10269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hara M, Nagasaki T, Shiga K, Takahashi H, Takeyama H. High serum levels of interleukin-6 in patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer: the effect on the outcome and the response to chemotherapy plus bevacizumab. Surg Today. 2017;47(4):483-489. doi: 10.1007/s00595-016-1404-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nikiteas NI, Tzanakis N, Gazouli M, et al. Serum IL-6, TNFα and CRP levels in Greek colorectal cancer patients: prognostic implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(11):1639-1643. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i11.1639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang PH, Pan YP, Fan CW, et al. Pretreatment serum interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α levels predict the progression of colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2016;5(3):426-433. doi: 10.1002/cam4.602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):3109-3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nelson H, Sargent DJ, Wieand HS, et al. ; Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group . A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(20):2050-2059. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimm M, Lazariotou M, Kircher S, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α is associated with positive lymph node status in patients with recurrence of colorectal cancer—indications for anti–TNF-α agents in cancer treatment. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2010;33(3):151-163. doi: 10.1155/2010/891869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pathak S, Nunes QM, Daniels IR, Smart NJ. Is C-reactive protein useful in prognostication for colorectal cancer? a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(10):769-776. doi: 10.1111/codi.12700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woo HD, Kim K, Kim J. Association between preoperative C-reactive protein level and colorectal cancer survival: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(11):1661-1670. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0663-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou J, Wei W, Hou H, et al. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein, Glasgow prognostic score, and C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio in colorectal cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:637650. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.637650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Block RC, Dier U, Calderonartero P, et al. The effects of EPA+DHA and aspirin on inflammatory cytokines and angiogenesis factors. World J Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;2(1):14-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ho GY, Xue X, Cushman M, et al. Antagonistic effects of aspirin and folic acid on inflammation markers and subsequent risk of recurrent colorectal adenomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(23):1650-1654. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lang Kuhs KA, Hildesheim A, Trabert B, et al. Association between regular aspirin use and circulating markers of inflammation: a study within the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(5):825-832. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Navarro SL, Kantor ED, Song X, et al. Factors associated with multiple biomarkers of systemic inflammation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(3):521-531. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vaucher J, Marques-Vidal P, Waeber G, Vollenweider P. Cytokines and hs-CRP levels in individuals treated with low-dose aspirin for cardiovascular prevention: a population-based study (CoLaus Study). Cytokine. 2014;66(2):95-100. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(12):1191-1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian Y, Ye Y, Gao W, et al. Aspirin promotes apoptosis in a murine model of colorectal cancer by mechanisms involving downregulation of IL-6–STAT3 signaling pathway. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(1):13-22. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1060-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiao S, Xie W, Fan Y, Zhou L. Timing of aspirin use among patients with colorectal cancer in relation to mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5(5):pkab067. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkab06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu X, Li J, Fu M, Zhao X, Wang W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu Y, Zhou BP. TNF-α/NF-κB/Snail pathway in cancer cell migration and invasion. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(4):639-644. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Fung TT, et al. Major dietary patterns are related to plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(4):1029-1035. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.4.1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elosua R, Bartali B, Ordovas JM, Corsi AM, Lauretani F, Ferrucci L; InCHIANTI Investigators . Association between physical activity, physical performance, and inflammatory biomarkers in an elderly population: the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(6):760-767. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCleary NJ, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Impact of smoking on patients with stage III colon cancer: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 89803. Cancer. 2010;116(4):957-966. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza’ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13(4):851-863. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.58928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Blarigan EL, Meyerhardt JA. Role of physical activity and diet after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(16):1825-1834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(10):a016295. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Idriss HT, Naismith JH. TNFα and the TNF receptor superfamily: structure-function relationship(s). Microsc Res Tech. 2000;50(3):184-195. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ. Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:754. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Holubek WJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, et al. , eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2010:528-536. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davis JS, Lee HY, Kim J, et al. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in US adults: changes over time and by demographic. Open Heart. 2017;4(1):e000550. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2016-000550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams CD, Chan AT, Elman MR, et al. Aspirin use among adults in the US: results of a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(5):501-508. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Formica V, Sera F, Cremolini C, et al. KRAS and BRAF mutations in stage II and III colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(4):517-527. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guastadisegni C, Colafranceschi M, Ottini L, Dogliotti E. Microsatellite instability as a marker of prognosis and response to therapy: a meta-analysis of colorectal cancer survival data. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(15):2788-2798. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tie J, Cohen JD, Lahouel K, et al. ; DYNAMIC Investigators . Circulating tumor DNA analysis guiding adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(24):2261-2272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2200075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tie J, Cohen JD, Wang Y, et al. Circulating tumor DNA analyses as markers of recurrence risk and benefit of adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1710-1717. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Factors Between Patients Included in vs Excluded From the Biomarker Cohort

eTable 2. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Colon Cancer Patients by Quintiles of Inflammatory Biomarkers

eTable 3. Five-Year Survival From the Kaplan-Meier Estimator by Quintiles of Inflammatory Biomarkers

eFigure 1. Kaplan-Meier Estimates for Recurrence-Free Survival by Quintiles of Inflammatory Biomarkers Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

eFigure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimates for Overall Survival by Quintiles of Inflammatory Biomarkers Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

eTable 4. Unadjusted Associations of Inflammatory Biomarkers With Survival Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis of Incorporating Diet and Lifestyle Factors for Adjusted Associations of Inflammatory Biomarkers With Survival Among Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

Data Sharing Statement