Abstract

An individual based randomized controlled trial (RCT) was designed to evaluate the impact of a customized short message service (SMS) intervention on HIV-related high-risk behaviors among Men who have sex with men (MSM). In total, 631 HIV-negative MSM were enrolled at baseline and divided into intervention and control groups randomly. Nine months later, the intervention group who received additional customized SMS intervention reported significantly lower rates of multiple partners, unclear partner infection status and condomless anal intercourse compared to the control group who received the routine intervention only. Six months post stopping the SMS intervention, the rates of unclear partner infection status and condomless anal intercourse still remained lower report in the intervention group. Our study shown that the customized SMS interventions can significantly reduce the HIV-related high-risk behaviors among MSM and with sustained effects over a period of time.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10461-023-03995-4.

Keywords: Randomized controlled trial, Men who have sex with men, Customized short message service, HIV-related high-risk behavior, Difference-in-differences

Introduction

Globally, men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV [1]. The HIV epidemic has been increasing dramatically among MSM in China [2]. In 2019, MSM accounted for approximately 23% of new domestic HIV infectors, the HIV infection rate in MSM was approximately 8%, which was higher than that of drug users (2.4%) and female sex workers (0.2%) [3]. A higher prevalence is associated with risky sexual behavior, Bowring [4] reported that 30–84% of MSM in Asia have condomless anal intercourse. In China, the rate of condomless anal intercourse among non-regular sex partners was 42.8% [5]. Furthermore, compared with non-MSM males, MSM have higher odds of engaging in commercial sex [6], drug use [7], and multiple sex partners [8], which makes them susceptible to HIV infection and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

Currently, face-to-face interventions to reduce HIV-related risk behavior among MSM population, such as motivational interviewing and peer interventions, are often used and have yielded good results. For example, Mausbach provided a face-to-face intervention for MSM in the intervention group based on motivational interviewing techniques, and by 12 months post-baseline 7.1% reduction in unprotected sexual behavior was observed in the intervention group compared to control group [9]. Similarly, Chakrapani provided a motivation interviewing-based counselling intervention to 459 MSM with 16.4% increase in condom use in the intervention group after 6 months [10]. Besides, Liu conducted a 12-month peer intervention to 367 MSM and showed 68% reduced risk of using illicit drugs in the intervention group compared to the control group [11]. However, given the sexual and HIV discrimination and stigma that MSM may feel during face-to-face interventions, this approach produced a high rate of subsequent attrition, which was not conducive to intervention sustainability [9, 12]. SMS has showed the advantages of being more efficient in the health intervention process [13]. Khosropour’s survey of MSM found that they were generally willing to accept an SMS-based intervention [14], and a study in Togo showed that the majority of MSM who received an SMS intervention were satisfied with it [15]. And considering the advantages of SMS itself such as low cost, speed, accuracy, spreadability, concealment, and interactivity [16], SMS intervention may be a promising intervention.

In fact, SMS sent via cell phones has been used to provide sexual health information to MSM. Gerend conducted a nine-month SMS intervention with 150 MSM and found that “daily text messages” intervention group received HPV vaccination at more than three times the rate of the control group [17]. Similarly, a Peruvian study found an increase in HIV testing rates among MSM after a three-week SMS intervention for 62 MSM who participated in focus groups [18]. Furthermore, Reback conducted an RCT of 286 MSM who used methamphetamine with a 9-month text message intervention at a biweekly frequency and found a significant reduction in methamphetamine use among MSM in the intervention group [19]. In addition, in China, Song sent HIV-related knowledge intervention messages to 162 MSM at a twice-weekly frequency, and condom use among MSM increased significantly after 6 months of the intervention [20]. In summary, SMS interventions for MSM have demonstrated their effectiveness and ability to prevent HIV.

However, most studies of SMS interventions are mass texting to the intervention group [20–22], we have not found any research report on the customized intervention of individual behavior. In addition, some studies had smaller sample sizes, and shorter observation periods [17, 18], and few study observed behavioral changes after intervention [18, 20]. Therefore, we designed a randomized controlled trial based on individuals to explore the effectiveness and significance of the customized SMS intervention approach in a larger MSM for 15-month visit.

Methods

Study Design

This was a single-site, parallel-arm, individual based randomized controlled trial. The plan was to recruited 600 HIV-negative MSM population and then randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups according to random numbers, with the control group receiving the routine intervention only and the intervention group receiving the additional customized SMS intervention, after 9 months, comparing the changes in high-risk behaviors between the two groups. Six months post stopping the SMS intervention, the HIV-related high-risk behaviors was observed again in both groups.

Sample Size

We set the incidence of condomless anal intercourse in the control group to 55% [23, 24]. PS software by Vanderbilt University was used to estimate the sample size, the number 264 was calculated for intervention group, based on a 30% incidence reduction in the intervention group compared to the control group, with 90% power and a one-sided alpha of 0.05. Considering the 10% lost visit of the participants, a total sample size of 580 cases at least was needed. Finally, a total of 631 HIV-negative MSM were recruited in our study.

Study Field and Participants

Kunshan Rainbow Service Organization (hereafter referred to as Kunshan Rainbow), a non-government organization in Kunshan city, Jiangsu province, is dedicated to helping HIV-high-risk populations cope with health crises and promoting the rights of people affected by HIV. Volunteers from Kunshan Rainbow recruited participants in various ways, such as online publicity, on-site recruitment, peer promotion, and outreach services.

Eligible MSM participants were > 18 years who were HIV-negative, as determined by a colloidal gold-based primary screening antibody test of enrollment. Participants reported having anal sex with a man in the past 3 months and met the following criteria:(1) willingness to provide a cell phone number, name, or nickname; (2) ability to participate in follow-up visits within the next year; (3) willingness to answer the questionnaires and test for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and other STDs; and (4) had no cognitive impairment and informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) currently participating in other AIDS-related intervention studies; (2) planning to move out of Kunshan City the following year; and (3) psychosis or dementia according to medical institution reports.

Randomization

To ensure randomization and reduce selection bias in the grouping of study subjects, random groups based on individuals was used in our study. A total of 631 HIV-negative MSM were recruited in our study, each participant was assigned three digits according to a random number table in order of enrollment. Those with an odd mantissa were included in the intervention group and those with an even mantissa were included in the control group.

Survey Contents

All participants entering the survey were required to complete the questionnaires, HIV and syphilis rapid testing, and clinical examination of gonorrhea, genital herpes, and condyloma acuminata.

The participants completed an electronic questionnaire by scanning the QR code of WeChat. The questionnaire was divided into two sections: sociodemographic characteristics and HIV-high-risk behaviors. Sociodemographic characteristics included nickname, mobile number, age, household registration, ways to find sexual partners, marital status with females, occupation, education, sexual orientation, age at first sexual intercourse, and whether tested for HIV in the past year. HIV-related high-risk behavior included eight questions, such as the number of sexual partners, Sex with male infector(refers that men who sex with HIV positive men), condomless anal intercourse, new-type drug use (refer to the new synthetic drugs, such as Methamphetamine, Rush, Capsule 0, Magu, etc.), group intercourse, commercial sex, Condomless oral sex, and condom use in last intercourse.

Rapid testing for HIV and syphilis HIV antibody primary screening and syphilis detection were performed using an HIV antibody diagnostic kit and syphilis spirochete antibody detection reagent (colloidal gold method; Newscen Coast Bio-Pharmaceutical). Those who were HIV positive in the rapid test were referred to the Kunshan Center for Disease Control and Prevention for confirmatory testing.

The clinical examination of gonorrhea, genital herpes, and condyloma acuminata was completed by professional doctors of the Department of Dermatology of Kunshan Jinling Hospital.

Intervention

The routine intervention in our study refers to the health education we provided to all MSM who came to Kunshan Rainbow for HIV testing and MSM who received health information from other public media. The customized SMS intervention were designed based on the questionnaire completed by each survey participant. At each follow-up visit, we recorded the high-risk behaviors of the study participants and then customize the relevant intervention messages to be sent, and if the participant’s high-risk behavior changed, the content of the intervention would change accordingly. (For additional information see online supplemental appendix)

Study Procedures and Measures

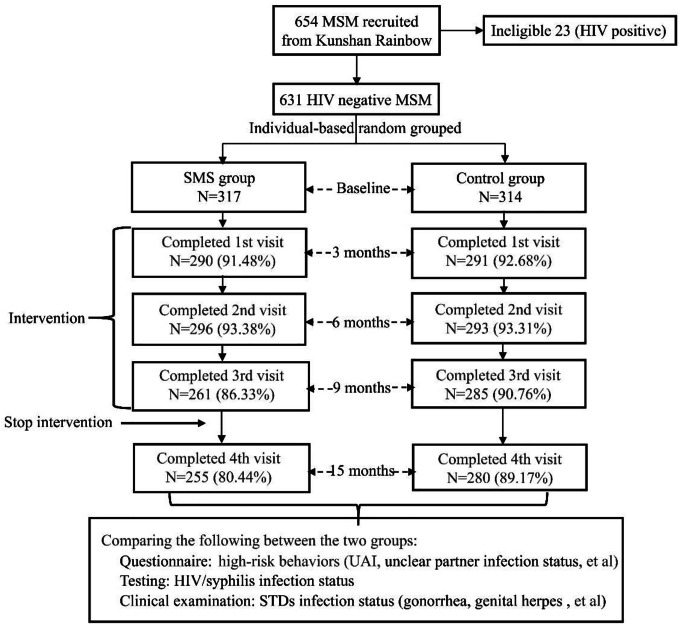

If eligible, participants were screened and enrolled within 30 days. Baseline participants were followed up at 3, 6, 9 months, and the fourth follow-up was conducted at the cessation of the intervention for 6 months after the end of the third follow-up visit, that is, a re-follow-up at 15 months after the baseline survey. Participants completed a questionnaire, rapid tests for HIV and syphilis, and clinical examinations for STDs at each follow-up visit.(Figure 1)

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for follow-up visits of participants

Participants who failed to come to the follow-up visit within the specified follow-up time were defined as lost to follow up, only data with complete follow-up would be retained for data analysis and we would call the loss participant to ask the HIV infection status and the reason for missing.

Statistical Analysis

The quantitative data were described as  , the comparison of two groups was performed using t test, and variance analysis was performed among multiple groups. Categorical data were described as N (%), Chi-square tests were used to compare the differences in the incidence of high-risk behaviors between the two groups during the 9-month intervention period and 6 months post stopping the intervention. Also, Z tests were used for two-by-two comparisons between multiple follow-up phases to describe differences in high-risk behaviors at each follow-up visit during the 9-month intervention period. Furthermore, Difference-in-differences (DID) models were used to measure the net effect of the customized SMS intervention on changes in high-risk behaviors in the intervention group.

, the comparison of two groups was performed using t test, and variance analysis was performed among multiple groups. Categorical data were described as N (%), Chi-square tests were used to compare the differences in the incidence of high-risk behaviors between the two groups during the 9-month intervention period and 6 months post stopping the intervention. Also, Z tests were used for two-by-two comparisons between multiple follow-up phases to describe differences in high-risk behaviors at each follow-up visit during the 9-month intervention period. Furthermore, Difference-in-differences (DID) models were used to measure the net effect of the customized SMS intervention on changes in high-risk behaviors in the intervention group.

HIV and STD cumulative incidences were calculated as the number of HIV seroconversions divided by the total number of person-years (PYs) of follow-up among those who tested HIV-negative at baseline.

The analysis was performed with SPSS 26.0 and Stata 17.0 statistical software.

Difference-in-differences

The DID model was used to measure the effect of the customized SMS intervention on HIV-related high-risk behaviors, which uses longitudinal data from two population groups (intervention and control) to obtain an appropriate counterfactual that allows the estimation of a causal effect.

As the dependent variable of the regression, we used high-risk behavior, a dichotomous variable that collects the results of the occurrence of HIV-related high-risk behaviors (1 for occurrence and 0 for non-occurrence). The effect of the customized SMS intervention was estimated according to the effects on the dependent variable from the interaction with the temporal variable time and the variable group.

The specification of the DID model is specified in:

|

where i = 0 is the control group, and i = 1 is the SMS group; t = 0 is the baseline, and t = 1 is the third visit (the 9-month follow-up visit); uit is the random disturbance term and Xit denotes the correction variable affecting the dependent variable; the coefficient β of the groupi×timet term in the DID model determines whether the DID value is statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

A total of 631 HIV-negative MSM were recruited at the end of April 2020, and a baseline survey was conducted in May 2020. The mean age of participants was 32.36 ± 8.46 years (range 16–70), 35.97% of them were married or cohabiting with a female, and 56.74% were service workers or freelancers. Of these, 44.22% had a college education or higher. The mean age for first anal intercourse with a man was 20.96 ± 4.61 years, 80.67% of the participants had been tested for HIV in the past year, and 583 (92.39%) were willing to initiate HIV testing in the future. After randomization of participants, the number of intervention and control groups were 317 and 314, respectively, and there were no statistical differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of 631 participants at baseline

| Variable | Total | SMS | Control | t/χ 2 | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Age | 32.36 ± 8.46 | 32.93 ± 8.53 | 31.78 ± 8.35 | 1.716 | 0.087 | |||

| 18–24 | 96 | 15.21 | 44 | 13.88 | 52 | 16.56 | 1.129 | 0.569 |

| 25–49 | 507 | 80.35 | 260 | 82.02 | 247 | 78.66 | ||

| ≥ 50 | 28 | 4.44 | 13 | 4.10 | 15 | 4.78 | ||

| Native place (province) | ||||||||

| Jiangsu | 225 | 36.66 | 111 | 35.02 | 114 | 36.31 | 5.166 | 0.160 |

| Others | 406 | 64.34 | 206 | 64.98 | 200 | 63.69 | ||

| Marital status with female | ||||||||

| In marriage | 227 | 35.97 | 114 | 35.96 | 113 | 35.99 | 3.315 | 0.191 |

| Unmarried | 365 | 57.85 | 178 | 56.15 | 187 | 59.55 | ||

| Other | 39 | 6.18 | 25 | 7.89 | 14 | 4.46 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Students | 26 | 4.12 | 10 | 3.15 | 16 | 5.10 | 1.553 | 0.460 |

| Service personnel/Freelancer | 358 | 56.74 | 183 | 57.73 | 175 | 55.73 | ||

| Personnel of enterprises and institutions/Others | 247 | 39.14 | 124 | 39.12 | 123 | 39.17 | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| College or above | 279 | 44.22 | 138 | 43.53 | 141 | 44.90 | 0.584 | 0.747 |

| High school | 230 | 36.45 | 120 | 37.85 | 110 | 35.03 | ||

| Junior high or below | 122 | 19.33 | 59 | 18.61 | 63 | 20.06 | ||

| Self-reported sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Homosexual | 425 | 67.35 | 217 | 68.46 | 208 | 66.24 | 2.105 | 0.349 |

| Heterosexual | 13 | 2.06 | 4 | 1.26 | 9 | 2.87 | ||

| Bisexual/Uncertain | 193 | 30.59 | 96 | 30.28 | 97 | 30.89 | ||

| Age of first homosexual intercourse | ||||||||

| 20.96 ± 4.61 | 20.70 ± 4.31 | 21.21 ± 4.89 | -1.399 | 0.162 | ||||

| Anal sex role | ||||||||

| Only 0 | 213 | 33.76 | 106 | 33.44 | 107 | 34.08 | 3.465 | 0.177 |

| Only 1 | 215 | 34.07 | 118 | 37.22 | 97 | 30.89 | ||

| 0 and/or 1 | 203 | 32.17 | 93 | 29.34 | 110 | 35.03 | ||

| HIV tested in last year | ||||||||

| Yes | 509 | 80.67 | 258 | 81.39 | 251 | 79.94 | 0.213 | 0.644 |

| No | 122 | 19.33 | 59 | 18.61 | 63 | 20.06 | ||

| Willing to take the HIV test voluntarily | ||||||||

| Yes | 583 | 92.39 | 290 | 91.48 | 293 | 93.31 | 0.822 | 0.663 |

| No | 10 | 1.58 | 6 | 1.89 | 4 | 1.27 | ||

| Unclear | 38 | 6.02 | 21 | 6.62 | 17 | 5.41 | ||

Changes in HIV-related High-risk Behaviors During Intervention Period

During the 9 months from May 2020, when the baseline survey was completed, to March 2021, follow-up visits were conducted at three-month intervals. The overall follow-up rate at 9 months was 86.53% (82.33% (261/317) for SMS group; 90.76% (285/314) for control group). And there was no statistical difference in sociodemographic characteristics between the two groups of lost to follow-up(see supplemental appendix for details). The results showed that the proportion of condomless anal intercourse was significantly lower in the SMS group than in the control group at all three visits and decreased by 26.51%3rd visit compared to baseline. Likewise, the proportion of multiple partners (number of male sexual partners ≥ 2) was significantly lower in the SMS group than in the control group (69.26% vs. 84.64%2nd visitχ2 = 19.626, P < 0.05 and 72.80% vs. 84.56%3rd visitχ2 = 11.341, P < 0.05), but was higher than the baseline by 11.22%2nd visit (χ2 = 8.299, P < 0.05) and 14.76%3rd visit (χ2 = 13.642, P < 0.05). Similarly, the percentage of unclear partner infection status was significantly lower in the SMS group than in the control group at all three visits and decreased by 26.11%3rd visit compared to baseline. Additionally, the incidence of condomless oral sex was significantly higher in the SMS group than in the control group at the third visit (χ2 = 5.523, P < 0.05). However, the difference was not significant compared to the baseline, and there was no statistical difference between all three visits. There were no significant differences between the SMS and control groups for other behaviors. There was no statistically significant difference between the second and third visits for all high-risk sexual behaviors in the SMS group. (See Table 2)

Table 2.

High-risk Sexual Behaviors Changes among Participants in Different Groups during 9 months Intervention Period

| Baseline | The first visit(3 Months) | The second visit (6 Months) | The third visit (9 Months) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMS N (%) |

Control N (%) |

χ 2 | SMS N (%) |

Control N (%) |

χ 2 | SMS N (%) |

Control N (%) |

χ 2 | SMS N (%) |

Control N (%) |

χ 2 | |

| Condomless anal intercourse | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 129(40.69)a | 120(38.22)a,b | 0.405 | 71(24.48)b | 129(44.33)b | 25.346* | 42(14.19)c | 103(35.15)a,b | 34.873* | 37(14.18)c | 81(28.42)a | 16.318* |

| No | 188(59.31) | 194(61.78) | 219(75.52) | 162(55.67) | 254(85.81) | 190(64.85) | 224(85.82) | 204(71.58) | ||||

| Number of male partners | ||||||||||||

| 0–1 | 133(41.96) | 139(44.27) | 0.344 | 61(21.03) | 45(15.46) | 3.022 | 91(30.74) | 45(15.36) | 19.626* | 71(27.20) | 44(15.44) | 11.341* |

| ≥ 2 | 184(58.04)a | 175(55.73)a | 229(78.97)b | 246(84.54)b | 205(69.26)c | 248(84.64)b | 190(72.80)b,c | 241(84.56)b | ||||

| Sex with male infector | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 6(1.89) | 2(0.64) | 2.000 | 6(2.07) | 2(0.69) | 8.737* | 4(1.35) | 1(0.34) | 26.224* | 8(3.07) | 5(1.75) | 12.980* |

| No | 193(60.88) | 195(62.10) | 212(73.10) | 187(64.26) | 254(85.81) | 205(69.97) | 224(85.82) | 216(75.79) | ||||

| Unclear | 118(37.22)a | 117(37.26)a | 72(24.83)b | 102(35.05)a | 38(12.84)c | 87(29.69)a,b | 29(11.11)c | 64(22.46)b | ||||

| Condomless oral sex | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 174(54.89)a | 172(54.78)a,b | 0.001 | 174(60.00)a | 182(62.54)b | 0.396 | 168(56.76)a | 148(50.51)a | 2.309 | 158(60.53)a | 144(50.53)a | 5.523* |

| No | 143(45.11) | 142(45.22) | 116(40.00) | 109(37.46) | 128(43.24) | 145(49.49) | 103(39.46) | 141(49.47) | ||||

| Condom use in last intercourse | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 240(75.71)a | 249(79.3)a | 1.165 | 265(91.38)b | 260(89.35)b | 0.689 | 269(90.88)b | 260(88.74)b | 0.738 | 244(93.48)b | 254(89.12)b | 3.235 |

| No | 77(24.29) | 65(20.7) | 25(8.62) | 31(10.65) | 27(9.12) | 33(11.26) | 17(6.51) | 31(10.88) | ||||

| New-type drug used | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 100(31.55)a | 88(28.03)a | 0.334 | 72(24.83)a | 90(30.93)a | 2.688 | 71(23.99)a | 87(29.69)a | 2.443 | 64(24.52)a | 82(28.77)a | 1.257 |

| No | 217(68.45) | 226(71.97) | 218(75.17) | 201(69.07) | 225(76.01) | 206(70.31) | 197(75.48) | 203(71.23) | ||||

| Group intercourse | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 38(11.99)a | 37(11.78)a | 0.935 | 20(6.90)a,b | 29(9.97)a | 1.772 | 13(4.39)b | 27(9.22)a | 5.411* | 15(5.75)a,b | 24(8.42)a | 1.469 |

| No | 279(88.01) | 277(88.22) | 270(93.10) | 262(90.03) | 283(95.61) | 266(90.78) | 246(94.25) | 261(91.58) | ||||

| Commercial sex | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 11(3.47)a | 16(5.10)a | 1.018 | 7(2.41)a | 7(2.44)a,b | 0.000 | 4(1.35)a | 2(0.68)b | 0.653 | 6(2.30)a | 2(0.70)b | 2.407 |

| No | 306(96.53) | 298(94.90) | 283(97.59) | 284(97.56) | 292(98.6) | 291(99.32) | 255(97.70) | 283(99.30) | ||||

Ps: (1)a vs. b, P < 0.05; (2) a vs. c, P < 0.05; (3) a vs. b,c, P < 0.05; (4) a vs. a,b, P ≥ 0.05; (5) b vs. a,b, P ≥ 0.05, (6) b vs. b,c, P ≥ 0.05; *: the SMS group vs. the control group, P < 0.05

Effects of the Customized SMS Intervention with DID Models

Capturing the net effects of SMS interventions through DID models can exclude the effects of routine interventions. Table 3 shows the results of the DID models for the incidence of high-risk behaviors. In models where the dependent variables were multiple partners, unclear partner infection status, last intercourse without condom, and condomless anal intercourse, the time*intervention interaction term (net effect term) β values were − 0.146 (t= -2.771, P = 0.006), -0.105 (t= -2.062, P = 0.040), -0.081 (t= -1.973, P = 0.049), and − 0.168 (t= -3.217, P = 0.001), respectively. After eliminating the effect of the routine intervention received by both groups, receiving the customized SMS intervention could reduce 16.77% in the proportion of condomless anal intercourse, 14.57% in the proportion of multiple partners, 10.53% in the proportion of unclear partner infection status and 8.11% in the proportion of last intercourse without condoms.

Table 3.

DID models estimates of the effect of the SMS on the probability of risk behaviors

| Dependent variable | Variable | Coeffificient (β) |

Std. Error | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple partners (number of male sexual partners ≥ 2) | |||||

| Time | 0.29321 | 0.035 | 8.323 | 0.000 | |

| Treated | 0.02312 | 0.039 | 0.592 | 0.558 | |

| Time*treated | -0.14568 | 0.053 | -2.771 | 0.006 | |

| Unclear partner infection status | |||||

| Time | -0.14411 | 0.037 | -3.858 | 0.000 | |

| Treated | 0.01219 | 0.039 | 0.310 | 0.754 | |

| Time*treated | -0.10530 | 0.051 | -2.062 | 0.040 | |

| Last intercourse without condom | |||||

| Time | -0.09669 | 0.029 | -3.274 | 0.001 | |

| Treated | 0.03590 | 0.033 | 1.083 | 0.281 | |

| Time*treated | -0.08108 | 0.041 | -1.973 | 0.049 | |

| Condomless anal intercourse | |||||

| Time | -0.09747 | 0.038 | -2.526 | 0.011 | |

| Treated | 0.02478 | 0.039 | 0.649 | 0.525 | |

| Time*treated | -0.16771 | 0.052 | -3.217 | 0.001 | |

| Condomless oral sex | |||||

| Time | -0.04243 | 0.041 | -1.032 | 0.301 | |

| Treated | 0.00113 | 0.040 | 0.033 | 0.977 | |

| Time*treated | 0.09890 | 0.058 | 1.701 | 0.089 | |

| New-type drug use | |||||

| Time | 0.00444 | 0.037 | 0.119 | 0.905 | |

| Treated | 0.03520 | 0.036 | 0.974 | 0.334 | |

| Time*treated | -0.07469 | 0.053 | -1.422 | 0.156 | |

| Group intercourse | |||||

| Time | -0.03243 | 0.025 | -1.313 | 0.190 | |

| Treated | 0.002039 | 0.026 | 0.078 | 0.937 | |

| Time*treated | -0.02997 | 0.034 | -0.878 | 0.378 | |

| Commercial Sexual | |||||

| Time | -0.04383 | 0.013 | -3.274 | 0.001 | |

| Treated | -0.01626 | 0.016 | -1.010 | 0.314 | |

| Time*treated | 0.03213 | 0.019 | 1.667 | 0.096 | |

HIV and STD New Infections

During the 9 months intervention period, there were five new HIV infections, of which, one in the SMS group occurred at the first follow-up (0.49 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 0.03–3.12), four in the control group (1.85 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 0.59–4.99): two cases occurred at the first and second follow-up visits, respectively, and two cases at the third follow-up visit. Other STD infections: (1) the SMS group: 3 syphilis infections (1.45 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 0.37–4.53), 5 gonorrhea infections (2.41 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 0.89–5.84), 1 genital herpes infection (0.48 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 0.03–3.05) and 5 condyloma acuminata infections (2.31 per 100 PYs, 95% CI 0.90–5.89); (2) the control group: 7 syphilis infections (3.38 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 1.49–7.15.), 6 gonorrhea infections (2.86 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 1.17–6.42); 1 genital herpes infection (0.47 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 0.02–2.99) and 11 condyloma acuminata infections( 5.23 per 100 PYs, 95% CI: 2.77–9.42). (See Table 4)

Table 4.

New HIV and STDs infections in participants

| SMS | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | PYs (person-years) |

HIV/STDs Incidence | N | PYs (person-years) |

HIV/STDs Incidence | |

| HIV Positive | ||||||

| 9-month intervention period | 1 | 204.25 | 0.49 | 4 | 215.75 | 1.85 |

| 6-month post intervention | 0 | 127.50 | 0 | 1 | 140.00 | 0.71 |

| Syphilis | ||||||

| 9-month intervention period | 3 | 206.50 | 1.45 | 7 | 206.75 | 3.38 |

| 6-month post intervention | 6 | 124.00 | 4.84 | 4 | 132.00 | 3.03 |

| Gonorrhea | ||||||

| 9-month intervention period | 5 | 207.50 | 2.41 | 6 | 209.50 | 2.86 |

| 6-month post intervention | 2 | 124.00 | 1.61 | 2 | 136.00 | 1.47 |

| Herpes genitalis | ||||||

| 9-month intervention period | 1 | 209.50 | 0.48 | 1 | 213.00 | 0.47 |

| 6-month post intervention | 0 | 126.00 | 0 | 1 | 138.00 | 0.72 |

| Pointed condyloma | ||||||

| 9-month intervention period | 5 | 205.75 | 2.43 | 11 | 210.25 | 5.23 |

| 6-month post intervention | 4 | 123.00 | 3.25 | 7 | 134.00 | 5.22 |

Changes in HIV-related High-risk Behaviors Post Stopping the Intervention

The follow-up rate at 15 months (the fourth visit) was 97.99%, SMS group was 97.70% (255/261) while control group was 98.25% (280/285), there was no statistical difference between the two groups. Table 5 showed that the proportion of unclear partner infection status was lower in the SMS group than in the control group (11.37% vs. 21.43% χ2 = 10.188, P = 0.002), a decrease of 25.79% compared to baseline (χ2 = 49.460, P < 0.05), but with no statistical difference from the third visit. Similarly, the proportion of condomless anal intercourse was lower in the SMS group than in the control group (21.96% vs. 37.86 χ2 = 15.974, P < 0.001), with a decrease of 18.73 compared to baseline (χ2 = 22.664, P < 0.05) and an increase of 7.78% from the third visit (χ2 = 5.290, P < 0.05). In addition, the proportion of new-type drug use was lower in the SMS group than in the control group (27.06% vs. 40.71% χ2 = 11.524, P < 0.001), with no statistical difference compared to both the baseline and the third visit (27.06%4th visit vs. 31.55%baseline vs. 24.523rd visit). There were no significant differences in other behaviors between the SMS and control groups.

Table 5.

High-risk Sexual Behaviors Changes among Participants in Different Groups after Stopping the Intervention

| Variable | The fourth visit (15 Months) | Compare to baseline | Compare to 3rd visit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMS N (%) |

Control N (%) |

χ 2 | P | SMS (extent %) |

Control (extent %) |

SMS (extent %) |

SMS (extent %) |

||

| Sex with male infector | |||||||||

| Yes | 5 (1.96) | 3 (1.07) | 10.188 | 0.002 | -25.79# | -15.83 | 0.26 | -1.03 | |

| No | 221 (86.67) | 217 (77.50) | |||||||

| Unclear | 29 (11.37) | 60 (21.43) | |||||||

| Condomless anal intercourse | |||||||||

| Yes | 56 (21.96) | 106 (37.86) | 15.974 | < 0.001 | -18.73# | -0.36 | 7.78* | 9.39* | |

| No | 199 (78.04) | 174 (62.14) | |||||||

| New-type drug used | |||||||||

| Yes | 69 (27.06) | 114 (40.71) | 11.524 | < 0.001 | -4.49 | 12.68# | 2.54 | 11.94* | |

| No | 186 (72.94) | 166 (59.29) | |||||||

| Number of male sexual partners | |||||||||

| 0–1 | 33 (12.95) | 25 (8.93) | 2.223 | 0.136 | 29.01# | 35.34# | 14.25* | 6.02* | |

| ≥ 2 | 222 (87.05) | 255 (91.07) | |||||||

| Last intercourse without condom | |||||||||

| Yes | 15 (5.88) | 27 (9.64) | 2.609 | 0.106 | -18.41# | -11.06# | -0.63 | -1.24 | |

| No | 240 (94.12) | 253 (90.36) | |||||||

| Condomless oral sex | |||||||||

| Yes | 136 (53.33) | 156 (56.71) | 0.305 | 0.581 | -1.56 | 1.93 | -7.21 | 6.18 | |

| No | 119 (46.67)5 | 124 (44.29) | |||||||

| Group intercourse | |||||||||

| Yes | 23 (9.02) | 34 (12.14) | 1.368 | 0.242 | -2.97 | 0.36 | 3.25 | 3.70 | |

| No | 232 (90.98) | 246 (87.86) | |||||||

| Commercial sex | |||||||||

| Yes | 7 (2.75) | 12 (4.29) | 0.925 | 0.336 | -0.72 | -0.81 | 0.45 | 3.59* | |

| No | 248 (97.25) | 268 (95.71) | |||||||

Ps: #: the fourth visit vs. baseline, P < 0.05; *: the fourth visit vs. the third visit, P < 0.05

Discussion

In this randomized, controlled trial evaluating an interactive, customized SMS-based intervention among HIV-negative MSM, participants who received customized SMS were less likely to have HIV-related high-risk behaviors. Specifically, the proportion of participants in the intervention group who had condomless anal intercourse, unclear partner infection status, and multiple partners was significantly lower than that in the control group after 9 months of intervention. Although the proportion of condomless anal intercourse increased in both groups six months after stopping the intervention, it remained lower in the intervention group than in the control group and at baseline.

Condomless anal intercourse is an important cause of HIV infection in MSM [1], our results showed that customized SMS could significantly improve condom use among MSM. Condomless anal intercourse was a high-risk behavior with the greatest reduction in this study, and the intervention effect was better than the QQ-based intervention service of Yan [25] and the web-based intervention study of Anand [26]. This may be due to two reasons: first, MSM were highly receptive to receiving HIV-related information by SMS, over 80% of respondents were in favor of using SMS interventions for HIV health education [27]; second, researchers sent text messages with health information about the risk of anal intercourse to participants who had condomless anal intercourse at the time of the follow-up visit, and this portion of the health message content was discontinued when these participants reported using condoms at the next follow-up visit three months later. This interactive feature positively improved the condomless anal sex behavior of MSM and facilitated the researcher’s understanding of the effects of the intervention [28].

In a survey of 342 MSM in Dalian, Yaxin [29] found that 33.6% of MSM were unaware of the HIV infection status of their sexual partners before having sex, which was similar to the 37.22% in our study. Disclosure of each other’s infection status among sexual partners would help take further protective measures to reduce the risk of HIV infection [30]. A study in Peru showed that communication between sexual partners could be effectively improved by increasing HIV risk awareness among MSM [31]. Therefore, in this study, we sent messages related to HIV infection risk knowledge to MSM in the intervention group, who were unaware of their partner’s infection status, and the results showed that the proportion of unclear partner infection status in this group continued to decline. MSM who received customized SMS had a significantly higher risk awareness and were more willing to actively ask about their sexual partner’s infection status, considering their health status.

Bairan [32] reported that knowing the infection status of sexual partners can stabilize sexual partner relationships and reduce the number of sexual partners. In our study, although the percentage of unclear partner infection status decreased significantly in both groups after 9-months intervention, the proportion of multiple partners in both groups was significantly higher than the baseline level. The reason for this was that the baseline survey was during the Covid-19 epidemic period when traffic was closed, and the reduced mobility of the population made sexual partners relatively fixed [33]. The lifting of the epidemic closure management in the subsequent follow-up visits led to an increase in the number of sexual partners. After excluding the effects of time and routine interventions, the DID model results showed that customized SMS could reduce the number of sexual partners in MSM. Notably, the proportion of all high-risk behaviors in the intervention group in our study was not statistically different between the second and third follow-up visits. This indicates that the intervention effect was significant in the short term, but the effect diminished over time, which is in line with the Berg’s finding [34]. Combined with the fieldwork of the follow-up intervention, it is speculated that this phenomenon may be due to the diminishing marginal utility of health education [35].

This study evaluated the 15-month effects of the customized SMS intervention on high-risk sexual behavior among MSM. We followed up with the study participants again six months after stopping the intervention and showed that there were no significant differences in the proportions of unclear partner infection status and new-type drug use in the intervention group compared to the third visit. In particular, new-type drug use did not show differences between the two groups during the intervention period but remained at baseline levels in the SMS group after stopping the intervention, in contrast to a significant increase in new-type drug use in the control group. It is evident that the effect of the text message intervention on these two high-risk behaviors of new-type drug use and sexual partner infection status among MSM was sustained. In contrast, although the intervention group did not return to the baseline level of condomless anal intercourse after stopping the intervention as did the control group, the change in condomless anal intercourse also rebounded with a longer cessation of the intervention. This may be closely related to psychosocial factors in the MSM population; MSM’s sexual orientation is in serious conflict with traditional attitudes; they often choose not to use condoms to promote trust between partners [36]. As a result, MSM had a high rate of knowledge about HIV prevention and treatment but a low rate of reporting safe sex, so this situation of separation of knowledge and behavior of HIV in this population was the focus of intervention [37]. Given the sustained effect of the customized SMS intervention on the change in condomless anal sex behavior in this study, we speculate that long-term, sustained follow-up with this intervention in the MSM community could reduce the risk of HIV. While emphasizing the importance of condom use, the intervention could include a warning about HIV infection, thereby raising awareness of the risks of reduced self-control.

Customized messages, which can be personalized to meet the specific needs of different individuals, are more effective than non-tailored messages and can make people feel more personally relevant. Our results suggest that a 9-month SMS intervention among MSM could improve condom use and reduce the incidence of multiple partners and unclear partner infection statuses. Furthermore, the increased awareness of the risks of new-type drug use and sexual intercourse with HIV-positive partners among MSM can be effectively maintained over time by customized SMS intervention. However, for condomless anal intercourse in MSM, only sustained intervention can facilitate the transition to safer sex.

There were also some limitations to this study: (1) The data for this study was obtained from recruited volunteers, and volunteer bias was inevitable. (2) HIV-related high-risk behaviors were enrolled by the participants themselves, and reporting bias was inevitable due to the privacy of the individuals involved which usually resulted underestimates the reporting rate. Two measures in this study can reduce information bias to some extent: one was the using of double-blind design for the questionnaire, i.e. neither the participants nor the data collectors (staff of Kunshan Rainbow) were unknow the grouping; the other was that at each follow-up stage, we performed laboratory tests for HIV syphilis as well as clinical examinations for STDs, and these objective indicators can also reduce information bias. (3) Only MSM who live in Kunshan were included in this study, so the representativeness of the study population was slightly lacking. (4) This study only intervened and followed up with the participants for nine months, and the program duration should be extended in the future when conditions permit the observation of the long-term effects of customized SMS interventions on MSM. (5) The start of the study coincided with an important point in the prevention and control of the Covid-19 epidemic, as the lockdown of the city and the restricted movement of people led to some changes in the behavioral characteristics of the study participants, such as the low number of sexual partners of the participants at baseline, which would lead to inevitable effects on the intervention effect and the study results.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Kunshan Rainbow Service Organization and Nantong Center for Disease Control and Prevention for helping with the distribution of questionnaires, blood sample for syphilis and HIV testing, data collection and administrative work.

Author Contributions

Hao Huang and Xun Zhuang designed the research study. Zhengcheng Xu, Xiaoyi Zhou, Meiyin Zou and Gang Qin contributed to acquisition of data. Hao Huang, Qiwei Ge, Yuxin Cao, Xiaoyang Duan and Minjie Chu analysed and interpreted the data. Hao Huang and Zhengcheng Xu drafted the manuscript. Xun Zhuang revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All the authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Science and Technology Major Project on A Multimodality model guided tailored screening, precise diagnosis, and prevention strategy (MODERN) for HIV Prevention and Control (2022YFC2304901); The Precision Targeted Intervention Studies among High Risk Groups for HIV Prevention in China, National Science and Technology Major Project (2018ZX10721102); The Key Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences Research in Jiangsu Education Department (2018SJZDI123); Nantong Health Commission, China (MB2021075); Science and Technology Project of Nantong City (MS12021099); Nantong Science Education and Health Program Medical Key Subjects (Infectious Diseases 2021[15]); Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX21_3127).

Code Availability (software application or custom code)

Not applicable.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nantong University (Approval number: No. (2019) 47). All participants signed an informed consent form.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Beyrer C, Baral SD, Griensven F, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):367–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han X, Takebe Y, Zhang W, et al. A large-scale survey of CRF55_01B from men-who-have-sex-with-men in China: implying the Evolutionary History and Public Health Impact. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18147. doi: 10.1038/srep18147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lian W, Zhang HP, Lu J, et al. First test results analysis of CD4 T lymphocyte among newly found HIV infected patients from 2015 to 2017 in Nantong. Chin J Health Lab Tec. 2019;29:1089–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowring AL, Veronese V, Doyle JS, et al. HIV and sexual risk among men who have sex with men and women in Asia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(10):2243–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Wang Z, Jiang X, et al. A cross-sectional study of the relationship between sexual compulsivity and unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in shanghai, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):465. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3360-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Bao R, Leuba SI, Li J, et al. Association of nitrite inhalants use and unprotected anal intercourse and HIV/syphilis infection among MSM in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1378. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09405-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fazio A, Hunt G, Moloney M. "It’s one of the better drugs to use”: perceptions of cocaine use among gay and bisexual asian american men. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(5):625–41. doi: 10.1177/1049732310385825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Zhang D, Yu B, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection and associated risk factors among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Harbin, P. R. China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mausbach BT, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, et al. Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for increasing safer sex behaviors in HIV-positive MSM methamphetamine users: results from the EDGE study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87(2–3):249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakrapani V, Kaur M, Tsai AC, et al. The impact of a syndemic theory-based intervention on HIV transmission risk behaviour among men who have sex with men in India: Pretest-posttest non-equivalent comparison group trial. Soc Sci Med. 2022;295:112817. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Vermund SH, Ruan Y, Liu H, et al. Peer counselling versus standard-of-care on reducing high-risk behaviours among newly diagnosed HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Beijing, China: a randomized intervention study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(2):e25079. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong NS, Mao J, Cheng W, et al. HIV linkage to Care and Retention in Care Rate among MSM in Guangzhou, China. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):701–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1893-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Q, Van Stee SK. The comparative effectiveness of Mobile phone interventions in improving Health Outcomes: Meta-Analytic Review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2019;7(4):e11244. doi: 10.2196/11244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosropour CM, Lake JG, Sullivan PS. Are MSM willing to SMS for HIV prevention? J health communication. 2014;19(1):57–66. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.798373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prata N, Weidert K, Soro DR. A mixed-methods study to explore opportunities and challenges with using a mHealth approach to engage men who have sex with men in HIV prevention, treatment and care in Lomé. Togo mHealth. 2021;7:47. doi: 10.21037/mhealth-20-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Velthoven MH, Brusamento S, Majeed A, et al. Scope and effectiveness of mobile phone messaging for HIV/AIDS care: a systematic review. Psychol health Med. 2013;18(2):182–202. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.701310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerend MA, Madkins K, Crosby S, et al. Evaluation of a text messaging-based human papillomavirus vaccination intervention for young sexual minority men: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Annals of behavioral medicine: a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2021;55(4):321–32. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaaa056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menacho LA, Blas MM, Alva IE, et al. Short text messages to motivate HIV Testing among Men who have sex with men: a qualitative study in Lima, Peru. The open AIDS journal. 2013;7:1–6. doi: 10.2174/1874613601307010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reback CJ, Fletcher JB, Swendeman DA, et al. Theory-Based text-messaging to Reduce Methamphetamine Use and HIV sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men: automated unidirectional delivery outperforms bidirectional peer interactive delivery. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(1):37–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song LP, Zhang ZK, Lan GH, et al. Impact of text message intervention on HIV-related high-risk sexual behaviro of MSM. Chin J AIDS STD. 2017;23(10):932–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnall R, Travers J, Rojas M, et al. eHealth interventions for HIV prevention in high-risk men who have sex with men: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014 May;26(5):e134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bourne C, Knight V, Guy R, et al. Short message service reminder intervention doubles sexually transmitted infection/HIV re-testing rates among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(3):229–31. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.048397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Y, Liu J, Chen Y, et al. The relation between mental health, homosexual stigma, childhood abuse, community engagement, and unprotected anal intercourse among MSM in China. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22403-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Hu Y, Jia Y, et al. Prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in China: an updated meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e98366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan HM, Gao C, Li Y, et al. Evaluation of QQ-based HIV high-risk behavior interventions for MSM population. China J AIDS STD. 2013;19(3):174–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anand T, Nitpolprasert C, Jantarapakde J, et al. Implementation and impact of a technology-based HIV risk-reduction intervention among thai men who have sex with men using “Vialogues”: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Care. 2020;32(3):394–405. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1622638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di L, Xuan D, Mingxu J, et al. Application of mhealth intervention in populations in relation to HIV infection control: a review. Chin J Public Health. 2016;32(12):1618–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bigna JJ, Noubiap JJ, Kouanfack C, et al. Effect of mobile phone reminders on follow-up medical care of children exposed to or infected with HIV in Cameroon (MORE CARE): a multicentre, single-blind, factorial, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(7):600–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70741-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaxin Z. The study on risk factors and intervention of HIV-risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Dissertation, China Medical University 2019.

- 30.Vanable PA, Carey MP, Brown JL, et al. What HIV-positive MSM want from sexual risk reduction interventions: findings from a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):554–63. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0047-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konda KA, Castillo R, Leon SR, et al. HIV Status Communication with Sex Partners and Associated factors among high-risk MSM and Transgender Women in Lima, Peru. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):152–62. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1444-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bairan A, Taylor GA, Blake BJ, et al. A model of HIV disclosure: disclosure and types of social relationships. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19(5):242–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyndman I, Nugent D, Whitlock GG, et al. COVID-19 restrictions and changing sexual behaviours in HIV-negative MSM at high risk of HIV infection in London, UK. Sex Transm Infect. 2021;97(7):521–4. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berg R. The effectiveness of behavioural and psychosocial HIV/STI prevention interventions for MSM in Europe: a systematic review. Euro Surveill. 2009;14(48):19430. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.48.19430-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Courtemanche C, Tchernis R, Ukert B. The effect of smoking on obesity: evidence from a randomized trial. J Health Econ. 2018;57:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Starks TJ, Gamarel KE, Johnson MO. Relationship characteristics and HIV transmission risk in same-sex male couples in HIV serodiscordant relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):139–47. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan YW. An Integrated Peer Intervention Trial to Decrease HIV Risky Sexual Behavior among Men Who Have Sex with Men. Dissertation, Anhui Medical University 2011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.