Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an intracellular pathogen that readily survives and replicates in human macrophages (MΦ). Host cells have developed different mycobactericidal mechanisms, including the production of inflammatory cytokines. The aim of this study was to compare the MΦ response, in terms of cytokine gene expression, to infection with the M. tuberculosis laboratory strain H37Rv and the clinical M. tuberculosis isolate CMT97. Both strains induce the production of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-16 at comparable levels. However, the clinical isolate induces a significantly higher and more prolonged MΦ activation, as shown by reverse transcription-PCR analysis of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, transforming growth factor beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) transcripts. Interestingly, when IFN-γ transcription is high, the number of M. tuberculosis genes expressed decreases and vice versa, whereas no mycobactericidal effect was observed in terms of bacterial growth. Expression of 11 genes was also studied in the two M. tuberculosis strains by infecting resting or activated MΦ and compared to bacterial intracellular survival. In both cases, a peculiar inverse correlation between expression of these genes and multiplication was observed. The number and type of genes expressed by the two strains differed significantly.

Tuberculosis (TB) is the main cause of mortality due to a single pathogen infection (12). The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that every year Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects and causes disease in up to 10 million people and the death of 3 million people worldwide (39). The success of mycobacteria as pathogens resides in their ability to replicate or persist in a dormant state within macrophages (MΦs) for long periods of time.

MΦs have an impressive number of antimicrobial defense mechanisms. This has placed a strong evolutionary pressure on M. tuberculosis to develop intra-MΦ survival capacity (18). For instance, M. tuberculosis adopts a differential gene expression strategy in the course of intra- versus extracellular replication (21).

Of note, it has recently been shown that enteropathogens that cause acute inflammatory colitis activate the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway, while nonpathogenic microorganisms (such as nonvirulent Salmonella strains) are able to inhibit this pathway by a mechanism of intestinal immune tolerance (26).

Nonvirulent (H37Ra) and virulent (H37Rv) M. tuberculosis strain-derived lipoarabinomannans (LAM) stimulate the NF-κB pathway in the opposite fashion: the H37Ra-derived LAM is capable of rapid activation of NF-κB, whereas the H37Rv-derived LAM is considerably less potent in stimulating NF-κB (4). This may contribute to the establishment of a protective immune response during infection with the nonvirulent strain of M. tuberculosis, which does not cause progressive disease in animals (40). Despite its weak activation of NF-κB, the virulent H37Rv strain stimulates the MΦs to produce several cytokines which may negatively or positively control the growth of phagocytosed microorganisms. So far, a few studies have focused on the differences between laboratory and clinical M. tuberculosis strain infections (20, 28, 29); however, none of them compared M. tuberculosis and MΦ gene expression during infection.

This study elucidated whether M. tuberculosis and human MΦs reciprocally influence their gene expression in the early phase of infection. This was achieved by analyzing transcription of eight MΦ cytokine genes and 11 M. tuberculosis genes on the same cDNA sample in the course of the first week of infection. Important differences were found between the H37Rv and CMT97 (22) strains in terms of gene expression and survival in activated and resting MΦs. These findings showed the plasticity of M. tuberculosis in sensing the environment and in adopting different survival strategies (10).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human macrophage infection.

Buffy coats were collected from healthy donors. Blood was diluted 1:1 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and mononuclear cells were separated on a Ficoll (Eurobio, Paris, France) gradient. The cells were harvested, washed twice, and plated at a concentration of 2 × 106/ml in 75-ml culture flasks. The culture was continued in glutamine-enriched RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with gentamicin and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). These cultures were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2–95% air atmosphere.

After 1 h of adherence, the supernatant was discarded, while the cells were washed twice and detached with cold PBS through gentle scraping. Isolation of the human MΦs was performed by magnetic depletion of nonmonocytes (monocyte isolation kit; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) using a cocktail of CD3, CD7, CD19, CD45RA, CD56, and anti-immunoglobulin E (anti-IgE) antibodies. The percentage of differentiated MΦs was checked at the FACscan with monoclonal antibodies specific for CD14. These showed a degree of purity not below 99%.

Infection of MΦs was performed on the day 7 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1, keeping M. tuberculosis and MΦs in 1 ml of medium for 2 h. After incubation, the extracellular bacteria were washed out with warm PBS. The infected MΦs were grown for another 7 days in 24-well plates without added growth factors and with replacement of the culture medium every 3 to 4 days. Noninfected MΦs, used as negative controls, were kept in a separate plate and in a different incubator to avoid any aerosol M. tuberculosis contamination. To study the role of the activation of MΦs in cytokine gene expression, they were incubated with 100 U of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and 1 μg of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) per ml 1 h prior to infection.

Mycobacteria.

The laboratory H37Rv and clinical CMT97 bacilli (the second was isolated at the Monaldi Hospital, Naples, Italy, from a TB patient's sputum 22) were transferred every 2 months in Sauton medium, allowing them to grow as a layer on the medium surface. In order to infect MΦs, mycobacterial layers were harvested every 2 months, spun down, and resuspended in sterile PBS. To get a homogeneous resuspension, the M. tuberculosis organisms were sonicated in a water bath sonicator (UST; 50 W, 20 kHz), regulated at a maximum power of 50 W, in sterile glass tubes. The samples were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Before infection, one M. tuberculosis aliquot was grown on 7H10 plates to titer the bacteria after freezing.

The same frozen master batch was used for each infection experiment.

Mycobacterial enumeration by CFU determination.

M. tuberculosiss grown for 7 days in 106 human MΦs (at an MOI of 10:1) were washed twice with sterile PBS and incubated for 30 min in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (0.1% saponin–PBS) at 37°C. The dilutions 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, 10−6, and 10−7 of each lysate (in 0.01% Tween 80–PBS) were plated as 50-μl droplets on 7H10 Middlebrook (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) medium. The CFU were checked after 21 days of culture in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Immunofluorescence.

The purified MΦs were kept in a chamber slide (Becton Dickinson Labware Europe, Meylan Cedex, France) for 5 days at a cell density of 0.25 × 106/well in 10% FCS and glutamine-enriched RPMI (Labtec) medium containing gentamicin and infected as already described. After 2 days, they were washed twice in PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. The MΦs were incubated first with the antibody against CD14 diluted 1:100 (Exalpha, Boston, Mass.). After three washes in PBS, they were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. After washes in PBS, the MΦs were blocked for 30 min in PBS enriched with 10% human serum at 4°C.

Staining with the antibody against IFN-γ (Endogen, Woburn, Mass.) was performed using the antibody at a final concentration of 1 μg/106 cells. After three washes, the secondary antibody, an anti-mouse total (heavy and light chain) IgG-indocarbocyanine (Cy3) conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) was added. All incubations with the antibodies were carried out for 45 min at room temperature in the dark. The double-stained MΦs were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss). Both stains were performed in parallel with an irrelevant isotype-matching antibody to exclude any nonspecific staining due to the isotype employed (mouse IgG1 kappa and mouse IgG-2b kappa; Cymbus, Hampshire, United Kingdom).

ELISA.

Human MΦs were prepared as described above and infected for 3 h at different MOIs (50:1, 10:1, and 1:1) with the two mycobacterial strains. After 1 and 3 days of infection, the culture supernatants were collected, while the IFN-γ protein was measured by a standard sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Endogen). Briefly, 50 μl of each sample was added to anti-human IFN-γ-coated strip well plate and followed by biotinylated antibody reagent for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes, 100 μl of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase solution was added to each well for 30 min at room temperature. Three washes were carried out before adding 100 μl of tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution, and after 30 min, the reaction was stopped. The units of IFN-γ were calculated from an IFN-γ standard curve.

RNA extraction.

The total RNA from infected human MΦs was extracted with a 4 M guanidinium isothiocyanate (GTC) single-step method (6). The solutions were prepared with diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated distilled water, while the extraction was performed on an RNase-free bench in a separate room. In order to get the maximum yield of good-quality M. tuberculosis total RNA without using a CsCl cushion, French press, or silica beads to lyse the mycobacteria, we slightly modified the GTC protocol. The infected MΦs, lysed with 4 M GTC, were sonicated three times for 10 min each in a water bath sonicator (UST; 50 W, 20 kHz). Total RNA was then extracted with warm-water-equilibrated phenol, put at 65°C for 5 min, then spun down and reextracted with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) for 10 min at 65°C. Finally, the supernatant was precipitated with 2.5 volumes of ethanol at −80°C overnight.

DNase I digestion and RT-PCR technique.

In order to get rid of any possible residue of genomic DNA, the total RNA (0.5 to 1 μg) was digested with 2 U of DNase I (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies, S. Giuliano Milanese, Milan, Italy) for 30 min at 37°C. The enzyme was inactivated at 75°C for 5 min without further phenol extraction to avoid any loss of RNA. In the same tube, the samples were reverse transcribed to cDNA with 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT) (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies), using 5 μg of p(dN6) random primers (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) per μl. The reaction continued for 1 h at 45°C in a total volume of 20 μl. The RT was inactivated at 95°C for 5 min. For each sample, one aliquot of DNase I-digested RNA, without RT, was used as a negative control for PCR amplification to ascertain that we were actually dealing with M. tuberculosis mRNA analysis. For each PCR, 1 μl of cDNA was used. Internal control of cDNA was achieved through PCR amplification using a pair of primers for a housekeeping gene, β2-microglobulin, for MΦs, and MT10Sa for M. tuberculosis. All cDNA samples with a good PCR product were subjected to further analysis with specific primers for human cytokine and M. tuberculosis genes.

PCR protocol.

PCR amplification was performed in a thermal cycler GeneAmp 2400 (Applied Biosystems) in 0.2-ml tubes in a total volume of 20 μl. Primers were used at a 0.5 μM concentration. We used 2 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 1 U of Taq polymerase (Amersham Pharmacia) in each tube. Samples were kept at 95°C for 5 min before adding 1 μl of cDNA. Then 35 cycles of amplification followed: (i) 45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 58°C, and 1 min at 72°C for eukaryotic cDNA; (ii) 45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 68°C, and 1 min at 72°C for prokaryotic cDNA. An elongation cycle of 10 min at 72°C followed, while the temperature was set up to hold 4°C. For each RT-PCR, 10 μl was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. Almost every time, we had to transfer 10 μl of RT-PCR products to a nylon membrane for Southern hybridization because of the low quantity of M. tuberculosis transcripts detectable only by ethidium bromide.

All primers designed for MΦ genes were RNA specific and nonreactive with DNA (30). The primer sequences are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences of primers employed in RT-PCR analysis

| Gene | Accession no. | Primer sequence and positionsa |

|---|---|---|

| b2 microglobulin | M17987 | 5′ 184-GAATTGCTATGTGTCTGGGT-203 |

| 3′ 2300-CATCTTCAAACCTCCATGATG-2289 | ||

| IL-1β | M15840 | 5′ 4336-GACACATGGGATAACGAGGC-4356 |

| 3′ 5819-ACGCAGGACAGGTACAGATT-5800 | ||

| IL-6 | M54894 | 5′ 52-TGAACTCCTTCTCCACAAGC-71 |

| 3′ 366-ATCCAGATTGGAAGCATCCA-347 | ||

| IL-10 | U16720 | 5′ 5511-ACCAAGACCCAGACATCAAG-5530 |

| 3′ 7925-CAGGTACAATAAGGTTTCTCAAG-7947 | ||

| IL-12 p40 | AF180563 | 5′ 16-CAGCAGTTGGTCATCTCTTG-35, |

| 3′ 435-CCAGCAGGTGAAACGTCCA-416 | ||

| IL-16 | U82972 | 5′ 1683-ATGCCTGACCTCAACTCCTC-1703 |

| 3′ 2030-CTCCTGATGACAATCGTGAC-2011 | ||

| TNF-α | Z15026 | 5′ 578-TGAGCACTGAAAGCATGATC-597 |

| 3′ 758-CCGCACCTCGACTCTCTATT-3739 | ||

| TGF-β | M38449 | 5′ 301-GACAGGTTGGTAGCACGC-320 |

| 3′ 394-GGACACCAACTATTGCTTCAG-414 | ||

| IFN-γ | J00219 | 5′ 508-TCTGCATCGTTTTGGGTTCT-518 |

| 3′ 2162-CAGCTTTTCGAAGTCATCTC-2142 | ||

| ahpC | U18264 | 5′ 649-GCGATCAATTCCCCGCC-665 |

| 3′ 1036-AAGGTCACGCGGTCGGC-1020 | ||

| 35-kDa antigen | M69187 | 5′ 669-GCGCACCCACCAAGCGC-685 |

| 3′ 903-GACGCTCTGCTCGGCGG-887 | ||

| MT10Sa | X60301 | 5′ 118-AGGGCCAGGTCGGTGGC-134 |

| 3′ 470-AGATCCGGACGATCGGC-454 | ||

| Ag85B | X62398 | 5′ 141-GGTCGAGTACCTGCAGG-157 |

| 3′ 631-CGTCACCCATCGCGAGG-615 | ||

| Ag85C | X57229 | 5′ 331-CCGCGTCGATGGGCCGC-347 |

| 3′ 680-CAGCGCGGAACCGCCCG-664 | ||

| ESAT6 | X79652 | 5′ 24-GCAGTGGAATTTCGCGG-40 |

| 3′ 247-CTTCGCTGATCGTCCGC-231 | ||

| rpoB | U12205 | 5′ 665-CTCCGTACCCGGAGCGC-681 |

| 3′ 1314-GCTCGCTGGTCCAGCCC-1298 | ||

| invB | AF006054 | 5′ 1233-GGGGTGCCCTATTCGTGGGGT-1253 |

| 3′ 1460-GCCGCCGCCTGGGCCGTAAAA-1439 | ||

| sigF | U41061 | 5′ 171-GTTTGCCTGCCGGCTCACCGG-191 |

| 3′ 715-CAACGGACGAAGCACCTCCCG-695 | ||

| umaA2 | U27357 | 5′ 11417-GTCGCAATGACTGGACCGCGG-11437 |

| 3′ 11930-AAGCTGAACCTCGAACCCGGG-11909 | ||

| eisb | AF144099 | 5′ -GGATCCGTCAGACCCACCGAGCAT- |

| 3′ -CGGATCCCCATCCATGGCGTGT- |

Each primer sequence is indicated in its 5′-3′ direction.

Modified from Wei et al. (37).

Southern hybridization.

After separation on an agarose gel, the PCR products were transferred to a nylon filter (Zeta Probe; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) by means of Southern blotting with 0.4 N NaOH. The filter was dried at room temperature in 3 MM chromatographic paper (Whatman, Maidstone, England), prehybridized for 2 h, and hybridized overnight with each gene-specific PCR fragment labeled with horseradish peroxidase (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia) at 42°C in a 10-ml final volume. The probe was removed, while the membranes were rinsed twice for 20 min in primary wash buffer, 0.4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–0.5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–6 M urea, at 42°C and twice for 5 min in secondary wash buffer (2× SSC) at 20°C. Signal detection was performed in the dark.

RESULTS

Cytokine expression in macrophages infected with two different M. tuberculosis strains.

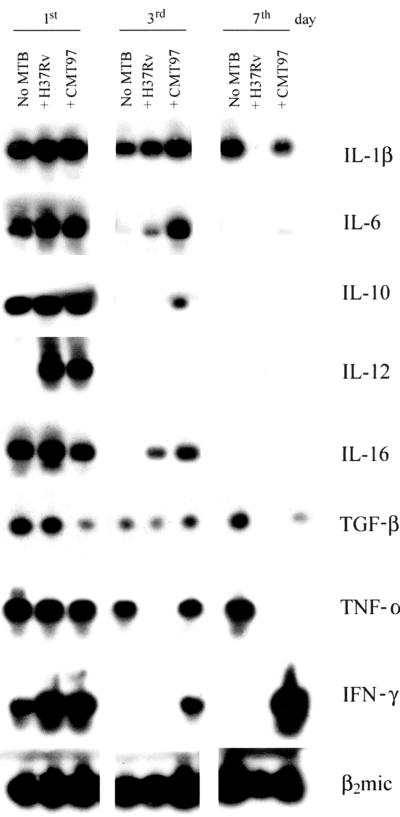

The mRNA levels of eight cytokines were analyzed (Fig. 1). After 1 day of infection, IFN-γ and IL-12 expression was only affected by M. tuberculosis. IFN-γ expression was low in control MΦs and upregulated in infected MΦs. Interestingly, IFN-γ RNA was the only one upregulated by the CMT97 M. tuberculosis strain at days 3 and 7. As this strain stimulates MΦ activation and easily reaches an equilibrium within the host cell, such a prolonged IFN-γ transcription may contribute to its peculiarities.

FIG. 1.

Southern blotting of RT-PCR products relative to the cytokines produced by resting uninfected human macrophages and by resting macrophages infected with two strains of M. tuberculosis (MTB), H37Rv and the CMT97 clinical isolate. Three time points were analyzed for each sample: 1, 3, and 7 days of culture for the controls, and 1, 3 and 7 days after infection for the infected cells. In each of the three groups, the first lane represents uninfected macrophages, the second represents H37Rv-infected macrophages, and the third represents CMT97-infected macrophages. As it comes out from the kinetics of RT-PCR products, the majority of cytokines decrease as a function of time, while the clinical strain induces a stronger and more prolonged production of TNF-α and IFN-γ compared with the laboratory strain H37Rv.

On the contrary, Il-12 was expressed exclusively in the infected MΦs. It became undetectable at days 3 and 7. IL-1β expression did not show great differences between uninfected and infected MΦs. This cytokine was no longer expressed in the H37Rv-infected MΦs at day 7 of infection. After 3 days of infection, the IL-6 levels were much higher in the infected MΦs than in the controls, while the CMT97 M. tuberculosis strain showed a higher ability to induce IL-6 RNA compared with the H37Rv M. tuberculosis strain. After 7 days, IL-6 remained slightly detectable only in the CMT97 M. tuberculosis-infected MΦs. The IL-16 mRNA, like IL-6 mRNA, was detectable after 3 days only in infected MΦs.

The CMT97 M. tuberculosis strain was more efficient than the H37Rv M. tuberculosis strain in IL-16 induction. Expression of IL-10 and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) was downmodulated with time. After 3 days, IL-10 mRNA was detectable in the CMT97 M. tuberculosis-infected MΦs. At day 7, it disappeared. TGF-β expression had already decreased on the first day in CMT97 M. tuberculosis-infected MΦs. It became undetectable on the seventh day in the H37Rv M. tuberculosis-infected MΦs.

A significant difference between the MΦs infected with the two M. tuberculosis strains was observed in the expression of the mRNAs for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IFN-γ. While the CMT97 M. tuberculosis-infected MΦs showed a strong TNF-α signal at the third day, in the H37Rv M. tuberculosis-infected MΦs the mRNA for this cytokine was undetectable. At the seventh day TNF-α was detectable only in control cells. Similar to TNF-α mRNA, IFN-γ mRNA expression was observed in CMT97 M. tuberculosis-infected MΦs only. Unexpectedly, it increased at the seventh day. As TNF-α and IFN-γ are important cytokines, playing a major role in the induction of the antimycobacterial protective immune response, the differences observed in the MΦs infected with the two M. tuberculosis strains suggested the existence of a novel mechanism through which M. tuberculosis may directly influence the activation of infected MΦs.

IFN-γ production by M. tuberculosis-infected human macrophages.

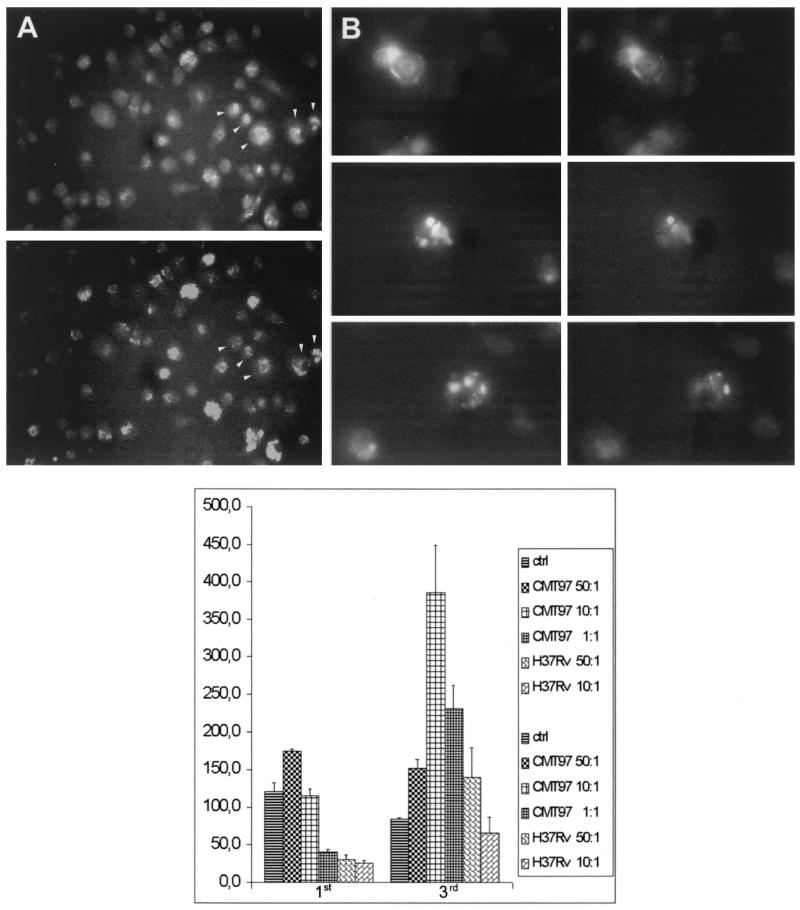

The unexpected finding that a strong IFN-γ signal was detected by RT-PCR in human MΦs prompted us to check its production at the protein level. Purified MΦs were infected with H37Rv M. tuberculosis and stained intracellularly with anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody. T-cell contamination was excluded by the absence of IL-4 signal using RT-PCR and hybridization with a probe specific for the amplified product (data not shown). Most of the infected MΦs were stained with monoclonal anti-IFN-γ antibodies and also with a monoclonal antibody specific for the CD14 molecule (Fig. 2A). When the MΦs infected with the two M. tuberculosis strains were stained with anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody, no relevant differences were observed (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

(A) Immunofluorescence of H37Rv-infected macrophages. The top panel shows anti-CD14 staining in nonpermeabilized macrophages; the bottom panel shows anti-IFN-γ staining in permeabilized macrophages. The arrowheads indicate macrophages that are positive for both antibodies. (B) Immunofluorescence of H37Rv- and CMT97-infected macrophages. Top and bottom panels, macrophages infected with the CMT97 strain. Middle panel, macrophages infected with the H37Rv strain. The left column shows anti-CD14 staining, and the right column shows anti-IFN-γ staining. (C) ELISA titration of IFN-γ released in culture supernatants of human macrophages infected with H37Rv and CMT97. The macrophages were prepared as described in the text and infected for 3 h at different MOIs (50:1,10:1, and 1:1); after 1 and 3 days of infection, the culture supernatants were collected, and IFN-γ protein was measured. Compared with the laboratory strain H37Rv, clinical strain CMT97 infection induces higher and more prolonged IFN-γ production.

To quantify the amount of IFN-γ released by MΦs infected with the two M. tuberculosis strains, IFN-γ was measured in the supernatant by ELISA. The MΦs were infected for 3 h at different MOIs (50:1, 10:1, and 1:1) with the two M. tuberculosis strains. After 1 and 3 days of infection, the culture supernatants were collected, and the IFN-γ protein was measured. The two M. tuberculosis strains displayed a different ability to induce IFN-γ (Fig. 2C). After 1 day, the CMT97 M. tuberculosis strain induced much higher IFN-γ release than H37Rv (in an MOI-dependent fashion). After 3 days of infection, the CMT97 M. tuberculosis strain still induced a two- to threefold-higher level of IFN-γ than H37Rv. In this case, the 10:1 MOI induced the highest level of cytokine release.

H37Rv and CMT97 M. tuberculosis intracellular gene expression analysis.

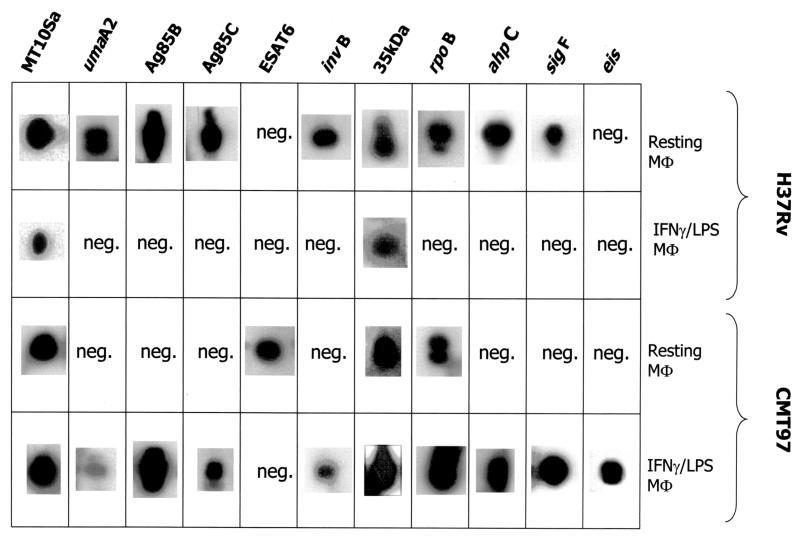

The two patterns of M. tuberculosis strain-specific gene expression proved to be rather different. They were inversely correlated with bacterial growth. Table 2 shows that the quantity of H37Rv M. tuberculosis transcripts decreased as a function of MΦ activation, in agreement with a recent study (21). The M. tuberculosis-complex-specific genes whose expression was analyzed were MT10Sa, a structural gene (36), 35 kDa (27), ahpC (31), Ag85B and Ag85C (14), ESAT6 (35), rpoB (24) invB (19), sigF (15, 7), umaA2 (11), and eis (37). Of these 11 mycobacterial genes in resting MΦ cDNA, 9 were expressed by strain H37Rv M. tuberculosis. The two negative signals concerned ESAT6, a well-known early secretory antigen of 6 kDa (2), and eis, encoding an enhanced intracellular survival-conferring gene. On the other hand, only two genes produced a positive signal in activated MΦs: MT10Sa, encoding a small stable RNA, and the 35-kDa antigen.

TABLE 2.

Gene expression in resting and activated macrophagesa

Summary of results of RT-PCR on cDNAs obtained from resting and activated human macrophages infected with strains H37Rv and CMT97. Positive gene expression (presence of a Southern signal) indicates that cDNA samples from three independent experiments were positive. neg., cDNAs did not show the expected bands except for the housekeeping gene MT10Sa.

Hence, the H37Rv M. tuberculosis strain exhibited decreased transcription of this group of genes as a function of host cell activation. In contrast, the pattern of transcription displayed by the CMT97 M. tuberculosis clinical isolate showed a low quantity of transcripts (4 of 11 genes) in the resting MΦs: MT10Sa, ESAT6, 35 kDa, and rpoB, the beta subunit of the RNA polymerase enzyme. In the activated MΦs, 10 genes proved to be transcribed (the negative one being that for ESAT6).

The bacterial choice to transcribe this group of genes appeared to receive a positive stimulus by the activation of the MΦs. The expression of the eis gene, which is not detected in resting MΦs, seemed to confirm a “counteraction” response; besides, the eis gene is known to confer increased intracellular survival to Mycobacterium smegmatis (37). Another qualitative difference between the two M. tuberculosis strains was the expression of the genes for the Ag85B and ESAT6 antigens, responsible for the immune response in mouse and human hosts (8, 17). The expression of these two genes seemed to be mutually exclusive, since a positive RT-PCR signal for both was never found in the same sample (Table 2). As a matter of fact, when the expression of the gene for Ag85B was positive, that of the gene for ESAT6 was negative, and vice versa.

It is noteworthy that ESAT6 expression was positive in an M. tuberculosis strain transcribing a small number of genes (Table 2) whose replication took place in infected MΦs producing IFN-γ (Fig. 1). On the contrary, the expression of the gene for Ag85B proved to be positive in an M. tuberculosis strain transcribing a large number of genes (Table 2), and it took place in MΦs which do not produce the IFN-γ (Fig. 1 and 3). Finally, in resting MΦs, while ESAT6 expression was displayed by the clinical M. tuberculosis strain, Ag85B expression was manifested by the laboratory M. tuberculosis strain.

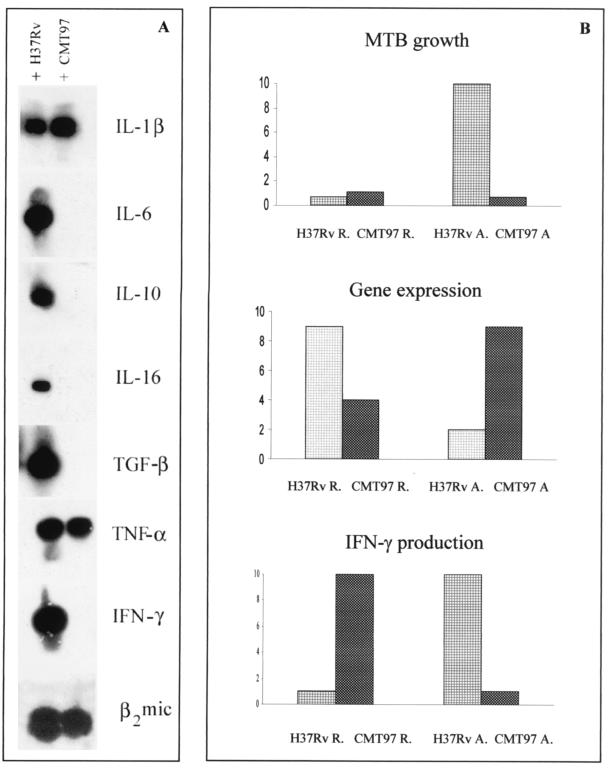

FIG. 3.

(A) RT-PCR Southern blotting for cytokine production in IFN-γ- and LPS-activated human macrophages. The cDNAs of human macrophages infected for 3 days with M. tuberculosis H37Rv and the clinical strain CMT97 were assayed with cytokine-specific primers. The housekeeping gene was β2 microblobulin (bottom line). The cytokines induced by CMT97 in the activated cells are only IL-1β and TNF-α, while laboratory strain H37Rv infection induces the production of all the cytokines analyzed. (B) Graphic representation of the modulation of CFU, bacterial gene expression, and IFN-γ production relative to H37Rv- and CMT97-infected macrophages, On the y axis are reported arbitrary units, ranging from 1 (assigned to the minimum value obtained) to 10 (assigned to the maximum value), independent of the absolute values of each group of observations. In particular, for CFU the values represent the bacterial colonies obtained from infected-cell lysates; for gene expression they reflect the number of M. tuberculosis-expressed genes out of the total number analyzed; for IFN-γ expression we considered the minimum and maximum optical density of the RT-PCR bands obtained.

Mycobacterial growth in macrophages.

The multiplication displayed by the two M. tuberculosis strains in human MΦs was rather interesting, especially in relation to the differences found in gene transcription. The CMT97 M. tuberculosis clinical isolate showed a CFU value in resting MΦs comparable to that of the laboratory M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv (not shown). A slight reduction in viable colonies was instead seen in MΦs activated with IFN-γ and LPS. On the other hand, the H37Rv M. tuberculosis, which grows similarly to the CMT97 M. tuberculosis in resting MΦs, showed a more than 10-fold increase in CFU in IFN-γ- and LPS-treated MΦs. Hence, H37Rv augments bacterial multiplication as a function of host cell activation (not shown). Such a striking phenomenon has already been observed in human MΦs (9). The data presented in this study suggest that the question concerning the complex network of human MΦ responses which are necessary to control M. tuberculosis infection (3) is still open.

DISCUSSION

The main questions we posed in this study were whether host transcription and pathogen transcription could influence each other and whether a particular M. tuberculosis clinical isolate, probably inducing antitumoral activity in a TB patient (22), would activate human MΦs in a different way than the M. tuberculosis laboratory strain. The data presented here showed that (i) the state of MΦ activation influences M. tuberculosis expression of a group of 11 selected genes, while M. tuberculosis transcription and multiplication influence the production of the MΦ cytokine transcripts and (ii) infection of the same MΦ by the two different M. tuberculosis strains induces differential cytokine gene expression and, consequently, a different MΦ response.

In this work we observed that when the production of “endogenous” IFN-γ by the MΦs is lowest, M. tuberculosis transcription of different genes (antigens involved in virulence and metabolism, etc.) becomes highest (Table 2 and Fig. 3). This cannot be justified by the expected IFN-γ mycobactericidal effect, since, compared to the resting MΦs, the M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain grows 10-fold in activated MΦs (not shown). Exogenous IFN-γ exerts a slight mycobacteriostatic effect on the growth of the M. tuberculosis clinical strain (not shown).

A possible explanation for the inverse correlation between M. tuberculosis expression of these 11 genes and the production of IFN-γ could be found in the study of the genes that the bacillus transcribes and in their possible influence on IFN-γ transcription itself. Let us now focus our attention on 3 of these 11 genes, namely, Ag85B, ESAT6, and eis, since they display the most relevant differences in their expression in the two M. tuberculosis strain infections.

The first gene is a member of the Ag85 complex (an important group of three immunodominant M. tuberculosis antigens, Ag85A, -B, and -C). Several studies demonstrated that the stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with Ag85B from both TB patients and healthy donors decreases the production of IFN-γ (16, 34). This feature is in agreement with the present results, showing that MΦs unable to produce IFN-γ (Fig. 1) are the ones in which M. tuberculosis expresses Ag85B (Table 2), given that both the MΦ- and M. tuberculosis-specific primers were used in RT-PCR on the same cDNA sample.

It is noteworthy that Ag85B expression is associated with a high gene expression pattern by M. tuberculosis (Table 2). The finding that H37Rv M. tuberculosis transcribes Ag85B in human macrophages is in contrast with a previous study (21), in which we found that this gene was expressed exclusively in synthetic medium; instead, in the same study we found that the mRNA for the Ag85A gene in intracytoplasmic M. tuberculosis is detectable. In the present study, however, Ag85A expression in the macrophages was negligible (not shown). This difference might be due to a different transcriptional regulation of the three related proteins whose expression in human phagosomes was actually detected with an antibody specific for the entire Ag85 complex, and not for any single polypeptide (12).

It might be possible, then, that M. tuberculosis transcribes each of the three genes at different times and/or in different amounts. This hypothesis is also supported by the biochemical characterization of the function of the three proteins, all being mycolyl transferases, able to catalyze the transfer of the fatty acid mycolate from one trehalose monomycolate to another, thus helping to build the bacterial cell wall (1). The three proteins belong to an antigenic complex made up of three polypeptides whose separation on the M. tuberculosis genome and differential transcriptional regulation have been shown. Therefore it is likely that their expression may be modulated by M. tuberculosis depending on various factors and that it may not always be the same in every macrophage. Furthermore, the fact that they have the same biochemical function could make the expression of all three proteins redundant to the same extent and contemporaneously.

The second gene produces an early secretory antigen for T cells of 6 kDa (ESAT6), able to induce IFN-γ production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (25). This information supported the finding that the M. tuberculosis clinical isolate, behaving as a strong and stable “enhancer” of IFN-γ, expresses ESAT6 in the course of intracellular replication (Table 2). The expression of ESAT6 by M. tuberculosis was associated with a pattern of low gene expression.

The third gene (eis) confers enhanced intracellular survival on mycobacteria (37). It is expressed by the clinical isolate only when its replication takes place in activated MΦs (Table 2). Such a bacillus, coexisting for a long time with its host, probably experienced the best tools to survive in the hostile environment of an activated MΦ. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence that the eis gene is induced by M. tuberculosis in infected human MΦs. Further studies will focus on its possible relation with IFN-γ production by the host.

For both the M. tuberculosis strains, a high expression pattern of this group of genes corresponds to a low CFU number and vice versa. Their modulation by the host cell activation is, however, exactly the opposite for H37Rv and CMT97. In fact, the laboratory strain, going from the resting MΦs to activated ones, dramatically increases its growth (not shown), while it decreases its gene expression (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Instead, the M. tuberculosis CMT97 isolate reacts to activation of the host MΦs by slightly diminishing its growth (not shown) and increasing the number of genes expressed in the MΦ cytoplasm. Among these genes there is eis, responsible for enhanced intracellular survival (37). With these features, the M. tuberculosis clinical isolate might have successfully adapted to human chronic infection.

The finding that two M. tuberculosis strains behave so differently in human MΦ infection is actually surprising, considering that one is a laboratory strain and the other was isolated from a human TB patient. On the other hand, we should consider that for many pathogenic bacterial species, it now begins to be commonly recognized that, in many respects, bacteria taken from infected animals are significantly different from those grown in vitro (32, 33). We should, in fact, pay more attention to the environmental conditions affecting bacterial growth, metabolism, and gene expression (5, 23). The question of why exponentially growing H37Rv M. tuberculosis should reduce expression of 11 different genes remains to be investigated. One may argue that M. tuberculosis is a slowly growing microorganism: its cycle lasts 16 h, while that of Escherichia coli lasts 20 min. Nucleic acid biosynthesis was indicated as a strong candidate for limiting its growth rate (38). The time to transcribe rRNA genes (13) was related to the generation time. Furthermore, M. tuberculosis has a single set of rRNA genes, while E. coli has seven rRNA operons. Probably, an actively growing M. tuberculosis would put the replication of the genome and the transcription of genes involved in DNA biosynthesis in an advantageous position, rather than slowing down its cell cycle with a large number of expressed genes.

The M. tuberculosis CMT97 clinical isolate induced a stronger and prolonged inflammatory cytokine production in infected MΦs (Fig. 1). In fact, the cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and especially IFN-γ are produced in higher amounts and for a longer period of time when the MΦs are infected with it. In particular, at the third and seventh day of infection, IFN-γ is exclusively induced by the M. tuberculosis clinical strain. A similar observation has already been reported (20). That study showed that the M. tuberculosis CDC1551 clinical isolate induced a more vigorous host response in vitro and in vivo (the latter was studied in the mouse model of TB). A fascinating paradox emerged from all this: when M. tuberculosis survives for a long time in human MΦs, its infection induces a stronger MΦ response (in terms of cytokine production). In other words, when the intracellular pathogen tried to reach a balance between its own survival and that of the host, a dynamic equilibrium occurred between its replication and the host's bactericidal process.

In conclusion, our experiments showed that (i) of the two M. tuberculosis strains used, the clinical isolate showed a stronger and more prolonged capacity to induce the production of IFN-γ (endogenous IFN-γ) by MΦs; (ii) the endogenous IFN-γ production was mainly influenced by the M. tuberculosis strain used to infect the MΦs rather than by the supply of exogenous IFN-γ; (iii) MΦ production of endogenous IFN-γ was able to decrease M. tuberculosis transcription of a group of 11 selected genes but not M. tuberculosis replication; and (iv) the two M. tuberculosis strains regulate the transcription of these genes and their replication in two opposite ways, although in both of them positive gene expression was associated with low bacterial replication and vice versa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Target Oriented Project-CNR, 1997–2000; Target Oriented Project-Ministry of Health-INMI “L. Spallanzani” 1999; and UNESCO-CNR grant.

Thanks are due to G. De Libero of the University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland, for helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D H, Harth G, Horwitz M A, Heisenberg D. An interfacial mechanism and a class of inhibitors inferred from two crystal structures of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 30 kDa major secretory protein (antigen 85B), a mycolyl transferase. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:671–681. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boesen H, Jensen B N, Wilcke T, Andersen P. Human T-cell responses to secreted antigen fractions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1491–1497. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1491-1497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonecini-Almeida M G, Chitale S, Boutsikakis I, Geng J, Doo H, He S, Ho J L. Induction of in vitro human macrophage anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis activity: requirement for IFN-γ and primed lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;160:4490–4499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown M C, Taffet S M. Lipoarabinomannans derived from different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis differently stimulate the activation of NF-κB and KBF1 in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1960–1968. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1960-1968.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busby, S. J. W., M. C. Thomas, and N. L. Brown. 1998. Molecular biology. NATO ASI Ser. Ser. H Cell Biol. 103.

- 6.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by guanidium thiocyanate phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Maio J, Zhang Y, Ko C, Young D B, Bishai W R. A stationary-phase stress-response sigma factor from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2790–2794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demissie A, Ravn P, Olobo J, Doherty T M, Eguale T, Geletu M, Hailu W, Andersen P, Britton S. T-cell recognition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate fractions in tuberculosis patients and their household contacts. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5967–5971. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5967-5971.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douvas G S, Looker D L, Vatter A E, Crowle A J. Gamma interferon activates human macrophages to become tumoricidal and leishmanicidal but enhances replication of macrophage-associated mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1985;50:1–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.1-8.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraziano M, Colizzi V, Mariani F. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and human macrophage: the bacillus with environmental-sensing. Folia Biol (Praha) 2000;46:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glickman M S, Cox J S, Jacobs W R., Jr A novel mycolic acid cyclopropane synthetase is required for cording, persistence, and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Cell. 2000;5:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith D E, Hardeman J L, Zhang Y, Wallace R J, Mazurek G H. Tuberculosis outbreak among healthcare workers in a community hospital. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:808–811. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harshey R M, Ramakrishan T. Purification and properties of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;432:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(76)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harth G, Lee B Y, Wang J, Clemens D L, Horwitz M. Novel insight into the genetics, biochemistry and immunochemistry of the 30-kilodalton major extracellular protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3038–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3038-3047.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Y, Coates A R M. Transcription of two sigma 70 homologous genes, sigA and sigB, in stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:469–476. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.469-476.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jo E K, Kim H J, Lim J H, Min D, Song Y, Song C H, Paik T H, Suhr J W, Park J K. Dysregulated production of interferon-gamma, interleukin-4 and interleukin-6 in early tuberculosis patients in response to antigen 85B of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 2000;51:209–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamath A R, Feng C G, Macdonald M, Briscoe H, Britton W J. Differential protective efficacy of DNA vaccines expressing secreted proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1702–1707. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1702-1707.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kauffman S H. Immunology of tuberculosis. Pneumology. 1995;3:643–648. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labò M, Gusberti L, De Rossi E, Speziale P, Riccardi G. Determination of a 15437 bp nucleotide sequence around the inhA gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and similarity analysis of the products of putative ORFs. Microbiology. 1998;144:807–814. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-3-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manca C, Tsenova L, Barry III C E, Bergtold A, Freeman S, Haslett P A, Musser J M, Freedman V H, Kaplan G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 induces a more vigorous host response in vivo and in vitro, but is not more virulent than other clinical isolates. Immunology. 1999;162:6740–6746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mariani F, Cappelli G, Riccardi G, Colizzi V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv comparative gene-expression analysis in synthetic medium and human macrophages. Gene. 2000;253:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariani F, Bocchino M L, Cappelli G, Persichini T, Colizzi V, Bonanno E, Ponticiello A, Sanduzzi S. Tuberculosis and lung cancer: an interesting case study. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2001;56:30–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall G, Bowe F, Hale C, Dougan G, Dorman C J. DNA topology and adaption of Salmonella typhimurium to an intracellular environment. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 2000;355:565–574. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller L P, Crawford J T, Shinnick T M. The rpoB gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:805–811. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.4.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustafa A S, Oftung F, Amoudy H A, Madi N M, Abal A T, Shaban F, Rosen Krands I, Andersen P. Multiple epitopes from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 antigen are recognised by antigen-specific human T cell lines. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl. 3):S201–S205. doi: 10.1086/313862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neish A S, Gewirtz A T, Zeng H, Young A N, Hobert M E, Karmali V, Rao A S, Madara J L. Prokaryotic regulation of epithelial responses by inhibition of IκB-α ubiquitination. Science. 2000;289:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connor S P, Rumschlag H S, Mayer L W. Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the 35-kDa protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Res Microbiol. 1990;141:407–423. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(90)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orme I M. Virulence of recent notorious Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79:379–381. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orme I M, Collins F M. Resistance of various strains of mycobacteria to killing by activated macrophages in vivo. J Immunol. 1983;131:1452–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pisa E K, Pisa P, Hansson M, Wigzell H. OKT3-induced cytokine mRNA expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells measured by polymerase chain reaction. Scand J Immunol. 1992;36:745–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherman D R, Mdluli K, Hickey M J, Arain T M, Morris S L, Barry C E, I. I I, Stover C K. Compensatory ahpC gene expression in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1996;272:1641–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith H. Pathogenicity and the microbe in vivo. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:377–393. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-3-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith H. What happens in vivo to bacterial pathogens? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;797:77–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb52951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song C H, Kim H J, Park J K, Lim J H, Kim U O, Kim J S, Paik T H, Kim K J, Suhr J W, Jo E K. Depressed interleukin-12 (IL-12), but not IL-18, production in response to a 30- or 32-kilodalton mycobacterial antigen in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4477–4484. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4477-4484.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorensen A L, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen A B. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tyagi J S, Kinger A K. Identification of the 10Sa RNA structural gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:138. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.1.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei J, Dahl J L, Moulder J W, Roberts E A, O'Gaora P, Young D B, Friedman R L. Identification of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene that enhances mycobacterial survival in macrophages. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:377–384. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.377-384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wheeler P R, Ratledge C. Metabolism of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Bloom B, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection and control. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 353–385. [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Heath Organization. Report on the tuberculosis epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M, Gong J, Lin Y, Barnes P F. Growth of virulent and avirulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1998;66:794–799. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.794-799.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]