Abstract

cis-Regulatory elements encode the genomic blueprints that ensure the proper spatiotemporal patterning of gene expression necessary for appropriate development and responses to the environment. Accumulating evidence implicates changes to gene expression as a major source of phenotypic novelty in eukaryotes, including acute phenotypes such as disease and cancer in mammals. Moreover, genetic and epigenetic variation affecting cis-regulatory sequences over longer evolutionary timescales has become a recurring theme in studies of morphological divergence and local adaption. Here, we discuss the functions of and methods used to identify various classes of cis-regulatory elements, as well as their role in plant development and response to the environment. We highlight opportunities to exploit cis-regulatory variants underlying plant development and environmental responses for crop improvement efforts. Although a comprehensive understanding of cis-regulatory mechanisms in plants has lagged in animals, we showcase several breakthrough findings that have profoundly influenced plant biology and shaped the overall understanding of transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes.

Keywords: cis-regulatory elements, chromatin, transcription regulation, development, adaption, stress response

1. INTRODUCTION

A major question in biology is how cellular diversity arises from a generally invariant genome. Backed by myriad studies in eukaryotes, the idea that cellular function is a manifestation of distinct gene expression programs has become well accepted. Moreover, transcriptional circuitries have been shown to be highly fluid across time, space, and environmental contexts, even within a single cell type. While recent studies demonstrate that a cell’s transcriptome largely sets the stage for its identity and function, the genetic mechanisms that allow variable interpretation of identical genomic sequences remain enigmatic. However, advances in chromatin profiling, high-throughput reporter assays, and single-cell genomics are now beginning to shed light on the central role of chromatin organization in gene regulation underlying development and sensing of environmental signals.

Patterns of transcription are mediated by cis-regulatory elements (CREs), DNA sequence motifs targeted by sequence-specific transcription factors (TFs). CREs are often found clustered together in cis-regulatory modules (CRMs). Through the cooperative activity of cognate DNA-binding proteins, CRMs dictate the developmental staging, cell-type/spatial patterning, and kinetics of transcription. To avoid ectopic transcription resulting in potentially detrimental outcomes, the cell carefully licenses which CRMs are capable of activity through the regulation of chromatin structure.

The twofold role of chromatin architecture is (a) to mechanically package DNA within the nucleus and (b) to regulate gene expression. Chromatin is hierarchically organized, ranging from a few base pairs to large nuclear domains spanning millions of bases. To accomplish this, the majority of nuclear DNA is tightly bound in ~147-bp segments around octamers of histone proteins, termed the nucleosome, representing the basic unit of chromatin packaging. A consequence of nucleosome packaging is that strong histone–DNA interactions preclude nucleosome-bound CRE sequences from being physically available to TF DNA-binding domains. Active CREs, on the other hand, are generalized by accessible chromatin regions (ACRs) and nucleosome depletion, enabling dynamic access between TFs and their target binding sites. This characteristic of chromatin packaging has led to the hypothesis that differential nucleosome occupancy and positioning in relation to CRM sequences underlie transcriptional variation.

Although the mechanics of transcription are relatively well understood (31), a comprehensive understanding of how CRMs gain activity through chromatin dynamics, how activity is maintained and modulated, and how CRMs contribute mechanistically toward phenotypic variation in diverse contexts is only just beginning to take shape. Here, we review recent breakthroughs that have advanced our understanding of CRMs in development, response to environment, adaptation, and evolution in plants.

2. FUNCTIONAL DIVERSITY OF CIS-REGULATORY MODULES

A major challenge to defining cis-regulatory rules is the abundant diversity of regulatory sequences. Here, we describe efforts to functionally characterize distinct regulatory types.

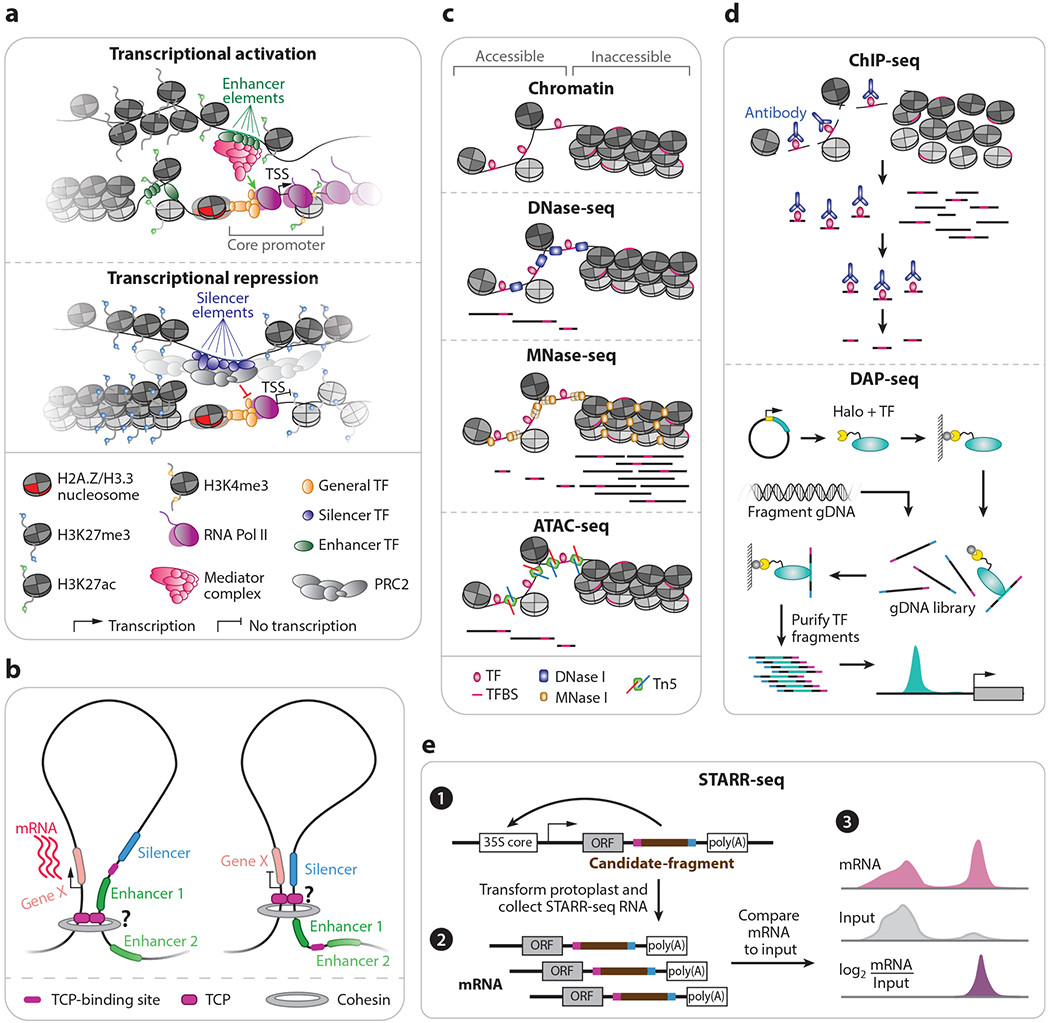

2.1. Core Promoters

Core promoter elements are the best understood class of CRMs owing to their predictable locations surrounding gene transcription start sites (TSSs) (Figure 1a). The core promoter serves to assemble components of the transcription preinitiation complex, including RNA polymerase II and general TFs, through a generally accessible chromatin configuration maintained by unstable histone variant H2A.Z (40, 41). Assembly of the complex is typically sufficient for basal transcription; however, modifications to the local chromatin environment can enable or repress transcription, such as acetylation of H2A.Z at the +1 nucleosome and 5-methylcytosine (5mC) DNA methylation in core promoter sequences, respectively (38, 68).

Figure 1.

Identification and classification of cis-regulatory elements. (a) Exemplary chromatin and cis-element landscape of actively transcribed and silenced genes. (b) Schematic of two cases of higher-order chromatin architecture resulting in distinct gene expression outcomes. Chromatin architecture in plants is predicted to be mediated by TCP transcription factors (CTCF in metazoans). (c) Illustration of chromatin accessibility profiling methods in a chromatin (top) and sequence fragment (bottom) context. (d) Schematic of ChIP-seq and DAP-seq approaches for mapping in vivo and in vitro transcription factor binding sites genome-wide, respectively. (e) STARR-seq experimental and computation workflow. Abbreviations: ATAC-seq, assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing; ChIP-seq, chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing; CTCF, CCCTC-binding transcription factor; DAP-seq, DNA affinity purification and sequencing; DNase-seq, DNase I digestion coupled with high-throughput sequencing; gDNA, genomic DNA; H3K27ac, acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27; H3K4me3, trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 4; MNase-seq, micrococcal nuclease sequencing; mRNA, messenger RNA; ORF, open reading frame; PRC2, Polycomb repressive complex 2; RNA Pol II, RNA polymerase II; STARR-seq, self-transcribing active regulatory region sequencing; TCP, teosinte branched 1/cycloidea/proliferating cell factor 1; TF, transcription factor; TFBS, transcription factor binding site; TSS, transcription start site.

Evaluation of transcription initiation shapes from cap analysis gene expression sequencing (CAGE-seq) and other 5’ capture methods indicates that core promoters are distributed as narrow or broad domains. For example, CAGE data in Zea mays show that 87% of TSSs are classified as narrow compared to 23% in fruit flies (89). Moreover, broad TSSs in maize are associated with greater and more constitutive gene expression, suggesting that narrow TSSs correspond to genes with restricted expression patterns, similar to metazoans (40). Core promoters can also be classified by distinct combinations of motifs that are either ubiquitous across eukaryotes, such as the TATA box found –35 bp upstream of TSSs (including 42% of maize sharp TSSs), or kingdom specific, such as Y-patch and CpG motifs in plants and mammals, respectively (93, 145). Trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) appears to be a ubiquitous feature of actively transcribed +1 nucleosomes in eukaryotes.

The unique combinations of distinct core promoter motifs, TSS shape, and chromatin environment in metazoans together hardcode the transcriptional output of a gene, termed burst size, that reflects the number of transcribing RNA polymerase II molecules during periods of active transcription (129). In mammals, transcription occurs stochastically in short yet intense bursts (16), with absolute transcript abundances regulated through enhancers that modulate burst frequencies (8, 66). Establishing the core promoter logic for plant species remains a major objective.

2.2. Enhancers

Studies of cis-elements capable of regulating target gene(s) in a location- and orientation-independent manner, termed enhancers, are just beginning to emerge in plants (Figure 1a). Distinct from promoters, enhancers lack the capacity for autonomous transcription initiation and have been shown to primarily regulate transcription burst frequency rather than the magnitude of messenger RNA (mRNA) biosynthesis, which appears to be established by the core promoter (40). Evaluation of chromatin and sequence features of plant enhancers suggests that they have both shared and unique attributes with enhancers defined in metazoans. For example, a recent survey of floral chromatin accessibility and histone modifications in Arabidopsis indicated that H3K4me1, a generalizable mark of enhancers in humans (43), is absent from plant distal enhancers (146). By contrast, H3K27ac, another mark of enhancers in humans (43), has been identified flanking distal enhancers in maize (101, 111). Interestingly, H3K27ac surrounding orthologous distal ACRs appears to be highly conserved in angiosperms despite millions of years of divergence (83).

In large eukaryotic genomes, a significant proportion of enhancers can be found in the intergenic space ranging from a few hundred bases to hundreds of kilobases away from the gene(s) they control. As such, many enhancers participate in chromatin loops: three-dimensional communication between enhancer- and promoter-bound proteins that impact transcriptional outcomes. Several examples of enhancer–promoter chromatin loops have been documented in plant species with moderate to large genome sizes, such as rice (27, 76), maize (69, 108, 111), and wheat (20). Species with more compact genomes, such as Arabidopsis, appear to have limited distal enhancers and are generalized by abundant local loops connecting 5’ to 3’ genic ends, termed self-loops (77).

Enhancers can also be embedded within the genes they regulate. Several well-known cell identity genes, such as AGAMOUS (AG) in Arabidopsis (119) and knotted1 (kn1) (49) in maize, have been previously shown to contain enhancer elements within their introns. Recently, a study of chromatin accessibility in Arabidopsis provided strong evidence for the widespread existence of intronic CRMs based on an average of ~1,000 accessible regions associated with ~1,100 genes across two tissues (90). Supporting regulatory function, tiled CRISPR deletions of ACRs within the second intron of TRIPTYCHON and seventh intron of CELLULOSE SYNTHASE-LIKE A10 suppressed transcription in specific developmental contexts and induced morphological phenotypes (90).

Context-dependent patterns of transcription via enhancers are hypothesized to be the result of interactions of enhancer-bound TFs and cofactors with transcription machinery at the core promoter (40). Indeed, CRMs within putative enhancers from distinct cell types are generalized by differential accessibility of various TF binding sites (86, 138). However, certain core promoters appear to only be compatible with select enhancer components and vice versa. For example, analysis of enhancer activity in HCT116 cells under several cofactor depletion treatments revealed unique enhancer categories with variable cofactor dependency, chromatin properties, and core promoter preferences (95). Similar investigations will be necessary to characterize enhancer functional diversity in plants.

2.3. Silencers

Regulatory sequences capable of silencing gene expression, termed silencers (Figure 1a), have been challenging to identify. Nevertheless, recent genome-wide studies have illuminated chromatin features potentially characteristic of silencing elements. For example, CRM–gene chromatin loops in maize associated with H3K27me3 were coincident with significantly lower transcript abundances compared to CRM–gene chromatin loops tethered by H3K4me3 nucleosomes (111). Analysis of single-cell chromatin accessibility and nuclear gene expression recovered previously identified Polycomb response element (PRE) motifs (144) de novo in ACRs upstream of H3K27me3-silenced genes (86). A genetically mapped locus upstream of teosinte branched 1 (tb1) with silencing activity was identified via assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) in maize seedlings and embedded within a large H3K27me3 domain (111, 127). Consistently analyses of transcriptional regulation in human cell lines and mouse embryonic stem cells suggest that long-range transcriptional silencing is coincident with Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2)-bound chromatin loops and a high density of H3K27me3-modified nucleosomes flanking distal ACRs (14, 96). Thus, a unifying theme of silencer elements appears to be the recruitment of PRC2 and deposition of H3K27me3. Implemented in mammalian models, high-throughput parallel reporter assays for quantitatively measuring silencing activity would be informative for querying the locations of silencing elements on a genome-wide scale in plants.

2.4. Insulators

The genomic space in which a CRM can act depends on the three-dimensional configuration of chromatin within the cell’s nucleus. In metazoans, higher-order chromatin organization is regulated by the CCCTC-binding transcription factor (CTCF). CTCF monomers dimerize to establish chromatin into distinct domains through interactions with the multisubunit complex, cohesin (Figure 1b). Second-order chromatin CTCF-cohesin domains can contain anywhere from a handful to hundreds of genes. Importantly domain formation constrains CRM–gene interactions to genomic sequences that are (a) within spatial proximity and (b) within the same CTCF-demarcated domain, often termed topology-associated domains (TADs). Thus, CRE sequences bound by CTCF in metazoan species function as insulator elements tasked with the spatial partitioning of large chromatin domains.

Plants exhibit similar higher-order chromatin organization, although species with compact genomes, such as Arabidopsis, appear to have limited TAD-like structure (77). Perhaps more curious is the lack of a clear CTCF homolog in the plant lineage, suggesting convergent evolution of one or more functionally equivalent chromatin architectural regulators. However, examples of CREs with bona fide insulator activity in plants are lacking, raising doubt of their existence. Although several studies in multiple plant models have coalesced to a handful of TFs, particularly from the teosinte branched 1/cycloidea/proliferating cell factor 1 (TCP) family (76, 86, 108), identification of the mechanistic factors orchestrating chromatin organization at the domain level remains a major objective for the field.

3. PROFILING ACCESSIBLE CHROMATIN REGIONS AND CIS-REGULATORY ELEMENTS

3.1. Experimental Methods to Identify Accessible Chromatin Regions

Active CRMs can be generalized by their occurrence in accessible chromatin that licenses interactions between TF DNA-binding domains and their target sequences (91). Several genome-wide assays for identifying CRMs have been developed that leverage the intrinsic association between cis-regulatory activity and chromatin accessibility. Optimization of these techniques for plants has fostered the generation of detailed genome-wide maps in numerous species. Here, we discuss various chromatin accessibility profiling methods and their use in plants.

3.1.1. DNase-seq.

First implemented in chicken nuclei (140), DNase I digestion has been the historical workhorse in the study of chromatin states. Application of DNase I for profiling chromatin accessibility was not broadly adopted until the 2000s, when DNase I digestion was coupled with high-throughput sequencing (DNase-seq) (12, 21, 22). Over the years, DNase-seq has undergone many iterations of technological developments that have ushered in higher-resolution maps, footprinting of individual TF binding events, and the chromatin accessibility landscapes of single-cells (53, 154–156).

DNase I digestion of native chromatin results in DNA cleavage specifically within regions depleted of bulk nucleosomes, producing fragments for sequencing library construction (Figure 1c). Notably, DNase-seq can be further divided based on two types of fragment preparations prior to sequencing: (a) end capture and (b) double hit. In the end-capture approach, digested fragments are ligated to a biotinylated linker with an MmeI restriction site, digested with MmeI to reduce fragments to 20 bp, ligated with a second adapter, and amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In comparison, the double-hit method directly attaches sequencing adapters to subnucleosomal digested fragments (100–500 bp), followed by PCR amplification. In both methods, the 5’ ends of mapped sequencing reads correspond to DNase I cleavage sites and are analyzed following similar computational schemes.

One particularly useful application of DNase-seq is the identification of TF-bound sequences protected from nuclease digestion, known as TF footprints. After aligning DNase-seq reads, TF footprints manifest as short regions recalcitrant to DNA cleavage that are embedded within a larger region of accessible chromatin. This approach has proven fruitful for the validation of known TF binding sites, such as Arabidopsis homeotic TFs SEP3 and APETALA1 (AP1) (155). However, a major strength of DNase-seq is the ability to identify TF footprints de novo. For example, nearly 700,000 de novo footprints were identified in a deeply sequenced DNase-seq data set generated from Arabidopsis seedlings (128). Evaluation of these footprints identified TF binding sites established from classical footprinting assays, such as the master photomorphogenesis regulator ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 within the RUBISCO SUBUNIT 1A promoter (128). However, care must be taken to remove signals from DNase I sequence bias that can lead to both false positive and negative footprints if not properly controlled. Further technological development of DNase-seq for use in single plant cells, as has been done in mammals (53), would be productive for mapping TF footprints in distinct cellular contexts.

3.1.2. MNase-seq.

Similar to DNase-seq, micrococcal nuclease digestion coupled with sequencing (MNase-seq) has emerged as a powerful approach to the identification of putative regulatory sequences. Several salient features make MNase-seq distinct from DNase-seq (Figure 1c). First, MNase (~17 kDa) is substantially smaller than DNase I (~30 kDa), which enables MNase to cleave histone linkers even in highly condensed chromatin. Second, MNase contains both endo- and exonuclease activity and largely produces fragments corresponding to mono-, di-, and trinucleosome-bound sequences. As a result, MNase-seq has been traditionally used to map nucleosome positioning rather than accessible chromatin.

Despite its historical use, MNase has been recently repurposed to assay CREs. One such iteration, termed differential nuclease sensitivity coupled to sequencing (DNS-seq), compared partially and heavily MNase-digested chromatin (112). Light digestion preferentially cleaves accessible chromatin, producing some nucleosome-protected fragments, while heavily digested chromatin predominantly produces nucleosomal fragments. A comparison of light and heavy digestion enables the identification of ACRs. Application of DNS-seq to maize inflorescence tissues uncovered TF footprints at base pair resolution, revealing the strong accessibility (97% of sites) of regions cobound by meristem determinacy factors KN1 and FEA4 and a novel motif enriched ~50 bp from FEA4-binding sites (105).

A recent innovation of MNase-seq exploits the endo- and exonuclease activities of MNase to recover short fragments representing TF binding footprints (117, 157). The technique, termed MNase-defined cistrome occupancy analysis (MOA-seq) documents TF binding sites within ACRs at high resolution. A collection of small MNase-seq fragments from Arabidopsis seedlings revealed ~15,000 ACRs missed by DNase-seq and ATAC-seq (157). MNase-seq-specific loci tended to be shorter (~85 bp on average), flanked by variably positioned nucleosomes, near genes associated with cellular differentiation and development, and enriched for repressive chromatin modifications H3K27me3 and 5mC. Similarly, analysis of MNase-seq short fragments in maize identified ~100,000 accessible regions, of which only 35% overlapped with previous ATAC-seq data (117). These studies demonstrate that repurposing MNase-seq allows for the detection of putative CREs associated with development that are inaccessible to other methods.

3.1.3. ATAC-seq.

ATAC-seq has emerged as the top method for chromatin accessibility profiling, boasting several advantages over nuclease-based approaches, including lower input nuclei requirements and a shortened protocol. The simplicity of ATAC-seq stems from the use of a hyperactive Tn5 transposase that preferentially inserts sequencing adapters into accessible chromatin (Figure 1c). Following tagmentation with Tn5, sequencing library preparation involves only a single round of PCR amplification.

The facile nature and low input requirements of ATAC-seq have resulted in a proliferation of plant chromatin accessibility maps. For example, using isolation of nuclei tagged in specific cell types (INTACT), Maher et al. (85) generated ATAC-seq data from the root tips of four species, including hair and nonhair Arabidopsis root epidermal cells. Analysis of ACRs between root epidermal cell types in Arabidopsis suggested largely quantitative differences that were coincident with ambiguous transcriptional outcomes; increased chromatin accessibility was frequently associated with both transcription activation and repression.

ATAC-seq has also been applied to investigations of TF footprinting. For example, Lu et al. (82) generated deep-coverage ATAC-seq data in Arabidopsis roots and seedlings, identifying approximately 125,000 potential TF-protected footprints. A comparison between tissues revealed that approximately 72% (~90,000/~125,000) of TF footprints were tissue specific (82). Analysis of tissue-specific footprints captured known biology such as the enrichment of motifs recognized by the photosynthesis TF PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR (PIF) in seedling-specific footprints and root-epidermal WRKY motifs in root-specific footprints. Tn5, similar to DNase I, exhibits sequence bias that can be effectively mitigated by normalizing to sequence preferences from a Tn5-treated genomic DNA sample.

3.1.4. scATAC-seq.

Due to the challenges of the plant cell wall and inability to culture homogeneous cell populations, chromatin accessibility profiling in plants has been largely performed on bulk tissues or necessitated the construction of cell-type-tagged transgenic lines. Recently, ATAC-seq was modified to allow tagging of chromatin accessibility of individual cells, termed single-cell ATAC-seq (scATAC-seq) (13). Development of scATAC-seq with microfluidic-based isolation (116) and combinatorial indexing (25) has further increased throughput and scalability, providing an attractive platform to address longstanding questions in developmental plant biology. Here, we provide an overview of scATAC-seq methods and findings in plants.

Current scATAC-seq methods can be classified as either (a) droplet based or (b) combinatorial indexed. In droplet-based assays, nuclei are tagmented in bulk and loaded onto a microfluidic chip that promotes the formation of aqueous droplets in oil containing a single nucleus, a barcoded bead, and PCR reagents. Within a droplet, uniform barcodes with complementary sequences to the Tn5-inserted adapters are released from the bead and attached to tagmented chromatin via PCR. Sequencing libraries are then constructed by emulsifying the phase-separated solution and amplifying by PCR with universal primers. In combinatorial indexing single-cell ATAC-seq (sciATAC-seq), nuclei are distributed into each well of a 96-well plate, tagmented with uniquely indexed Tn5 transposomes, pooled, and redistributed to multiple 96-well plates at a low concentration. Well- and plate-specific indexed sequencing adapters are then attached via PCR.

Recent application of scATAC-seq to plants has yielded unprecedented insight (24, 87). In a proof-of-principle study, Farmer et al. (30) illustrated that the chromatin accessibility landscape of Arabidopsis root cell types was predictive of nuclear gene expression patterns. Single-cell data have also been leveraged to reconstruct developmental trajectories that reflect a developmental path from an undifferentiated to a mature cell state. For example, Dorrity et al. (28) identified increased endoreduplication, activation of distinct gene expression programs, and overrepresentation of unique TF signatures along developing Arabidopsis endodermal cell subtypes. Such developmental trajectories have also been compared between species. Using an optimized protocol (88), a comparison of maize and Arabidopsis TF motif activity across phloem companion cell development revealed highly conserved and innovative TF dynamics (86).

Application of sciATAC-seq to plants has lagged for droplet-based techniques, presumably due to the technical nature of the protocol. To foster adoption of combinatorial approaches, Tu et al. (133) developed an optimized version of sciATAC-seq, complete with detailed experimental descriptions. A comparison of sciATAC-seq and scATAC-seq from Arabidopsis roots revealed similar chromatin accessibility dynamics within and across distinct cell types. Moreover, sciATAC-seq afforded greater signal-to-noise ratio measured by the fraction of reads in peaks (FRiPs) and with reduced costs compared to current commercial droplet-based methods. Single-cell approaches in plant biology are in their infancy, and the continued development of experimental and computational frameworks will undoubtedly usher a new frontier of discoveries in plant biology.

3.2. Experimental Methods to Validate cis-Regulatory Modules

Although many studies have charted the genomic locations of putative CRMs via chromatin accessibility profiling, fewer studies have provided functional validation. Here, we outline complementary approaches for directly and indirectly assessing functionality of putative CRMs.

3.2.1. Assaying transcription factor binding.

Methods that pinpoint TF localization provide information supporting regulatory function. There are numerous approaches capable of assaying TF binding site preferences; however, two sequencing-based methods, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) and DNA affinity purification sequencing (DAP-seq), stand out.

ChIP has been used to assess in vivo DNA–protein interactions since the mid-1980s (37) and was first coupled to sequencing in 2007 to map the genomic locations of NEURON-RESTRICTIVE SILENCING FACTOR in human T lymphoblast cells (54). Experimentally, chromatin of crosslinked or native nuclei are fragmented and precipitated with an antibody to the protein of interest. DNA associated with the protein of interest is then purified and attached to sequencing adapters via PCR amplification (58) (Figure 1d). Application of ChIP-seq to plants has proven fruitful for understanding links between genetic, molecular, and developmental phenotypes. For example, the maize kn1 mutant exhibits impaired inflorescence and shoot development (136) and is encoded by a class I KNOTTED1-like homeobox (KNOX) TF expressed in shoot meristems (51). ChIP-seq across a developmental gradient of maize pistillate inflorescence revealed thousands of KN1-bound regions enriched near other TFs and regulators of auxin metabolism, enabling the identification of a molecular network associated with maize meristem identity (10). However, ChIP-seq typically only identifies persistent and stable protein–DNA interactions and often fails to capture transient binding events (2), highlighting the need for further innovation.

DAP-seq was developed to address some of the key challenges of ChIP-seq, notably the reliance on quality antibodies and lower throughput. To this end, DAP-seq utilizes in vitro expression of HALO-tagged TFs in conjunction with amplified (5mC removed) and unamplified (5mC present) genomic DNA (gDNA) libraries (102) (Figure 1d). Tagged TFs are first immobilized by Magne HaloTag beads, washed of cellular debris, incubated with gDNA libraries, and washed to remove unbound fragments. Sequencing libraries are then prepared by eluting DNA and attaching adapters. The modularity of DAP-seq facilitates high-throughput screening, evidenced by the profiling of context-independent binding sites for 529 Arabidopsis TFs in the inaugural study (102). As TF affinity is assayed on DNA methylation-free and native gDNA substrates, DAP-seq also provides information on TF DNA methylation sensitivity. Indeed, DNA methylation inhibited greater than 75% of testable (327) Arabidopsis TFs, while only 4.3% preferentially bound methylated DNA. Analysis of binding patterns enabled the characterization of TF dimerization properties and spacing preferences. A follow-up study of 14 maize AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS (ARFs) revealed less than 0.8% of the genome-wide instances of the ARF consensus motif, TGTC, were bound by at least 1 of the 14 ARFs (34). A comparison of DAP-seq binding sites to genomic background indicated that ARFs bind highly clustered TGTC motifs, a finding that would not have been possible via in silico methods. However, a caveat of DAP-seq is the inability to identify binding sites for TFs that require heteromultimeric interactions for binding, causing many TFs to fail under the current framework.

3.2.2. cis-Regulatory elements are depleted of 5mC.

Genome-wide profiling of DNA methylation has yielded distinct patterns of context-specific methylation relative to gene or transposable element (TE) annotations (67, 97, 125). Many genes have methylation in the CG context within the middle portions of the coding sequences, often referred to as gene body methylation (9). TEs and many intergenic regions have elevated levels of CG and CHG methylation. Moderate levels of CHH methylation are often found near the edges of transposons and may mark the boundaries between heterochromatin and euchromatin regions (35, 36, 71, 150). Many crop species have an inflated intergenic space relative to model species such as Arabidopsis. Mapping of regulatory elements has provided examples of CREs located 50–100 kb away from the gene(s) they regulate (19, 115, 126). While most intergenic regions have high levels of DNA methylation, the genomes of many angiosperms contain short (several hundred base pairs) unmethylated regions (UMRs) (23, 100). UMRs lack DNA methylation in all sequence contexts, and many are found near or within genes. A comparison of UMRs and ACRs identified in maize seedling leaf tissue revealed that virtually all ACRs fall within UMRs (23, 98). However, there are many additional UMRs that are inaccessible. ACRs are highly dynamic in different tissues (111) or cell types (86). By contrast, UMRs are highly similar in distinct plant tissues (23). Many UMRs identified in leaf tissue that lack accessibility in leaves are identified as ACRs in other tissue contexts (23). These observations suggest that documenting UMRs catalogs potential ACRs that could be present in a specific tissue or environmental condition.

3.2.3. Functional activity.

Prior to genome-wide profiling methods, functional validation of CRMs relied on the use of reporter assays. For example, Studer et al. (127) used transient luciferase assays with a minimal promoter in maize protoplasts to validate the activity of a transposon-derived enhancer upstream of tb1. Assessing the functionality of intergenic DNase I hypersensitive sites in Arabidopsis, Zhu et al. (159) cloned 14 predicted enhancers upstream of a minimal promoter driving β-GLUCURONIDASE (GUS). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and subsequent GUS staining of stable transgenics revealed that 71% of predicted enhancers exhibited reproducible reporter signals. Despite their success in evaluating regulatory function, reporter assays relying on stable transformation are laborious, largely qualitative, and limited to species that can be successfully transformed. To overcome these challenges, Lin et al. (73) developed a rapid quantitative transient assay based on the luciferase reporter and Nicotiana benthamiana leaf agroinfiltration. Benchmarking the rapid validation system on previously validated Arabidopsis enhancers showcased remarkable consistency with stable transformed reporters. Moreover, the system is capable of measuring activity in vivo in real time, allowing the identification of oscillatory enhancer activity patterning corresponding to dynamic light perception.

Innovation of reporter assays with high-throughput sequencing now enables genome-wide profiling of regulatory activity. Of these methods, self-transcribing active regulatory regions sequencing (STARR-seq) has emerged as a powerful and dynamic approach to test regulatory activity in a highly parallel fashion (5) (Figure 1e). In STARR-seq, a DNA library is cloned between an open reading frame (ORF) and a poly(A) site that is driven by a minimal promoter. The reporter library is then transfected into a pool of cells and subjected to poly(A) RNA isolation. After reverse transcription, self-transcribed reporter fragments are amplified.

STARR-seq was recently applied to plants. Using an ATAC-seq library derived from maize leaf tissue as input to the STARR-seq vector, Ricci, Ji, Lu, and coworkers (111) assessed the regulatory activity of gene-distal ACRs. This study revealed several salient features associated with increased regulatory activity, including a chromatin state enriched with acetylated histone H3, participation in long-range chromatin loops, a greater density of TF binding sites, and orientation-independent function (111). Working toward a plant-optimized version of STARR-seq, Jores et al. (56) assessed the effects of variable enhancer positions within the reporter construct, finding that 3’ untranslated region positioning reduced the activity of the 35S enhancer. As a result, the authors developed an optimized construct by placing candidate enhancers upstream of the minimal promoter and a barcode between the ORF and poly(A) site, requiring an additional sequencing step to associate barcodes with candidate fragments. Applying this design to saturation mutagenesis led to the identification of TCP, ethylene response factor (ERF), and basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family functional elements as driving 35S enhancer activity. Further optimization to increase fragment recovery and innovations in transformation will enable expanded profiling in diverse species.

3.2.4. Genetic evidence for regulatory function.

Evidence for regulatory activity has also been derived from population and comparative genomics. For example, ACRs are enriched with conserved noncoding sequences (123). ACRs also exhibit a significant reduction in genetic diversity, suggesting that the sequences within these regions are subject to strong selection (55, 111). One study in maize estimated that the ACRs explain nearly 40% of the phenotypic variation for myriad quantitative traits, suggesting a critical role in generating phenotypic diversity (112). It is expected that genetic variation in ACRs might lead directly to altered expression of nearby genes (62), while ACRs documented in maize seedlings exhibit significant enrichment for cis-expression quantitative trait loci (cis-eQTLs) (111). Together, these analyses suggest that the accessible portions of the genome are enriched for functional traits, similar to observations noted by the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) (29).

4. DEVELOPMENT

Accumulating evidence points to variation in CREs as key mediators of developmental and organismal phenotypes. Elucidating the tissue-and cell-type-specific activities of regulatory regions has the potential to establish the cis-regulatory code underlying developmental patterning. Here, we detail the roles of cis and trans regulators foundational to embryonic and postembryonic development and their utility for crop improvement.

4.1. Embryonic Development

Plant development starts with an individual fertilized egg cell, the zygote. A series of asymmetric cell divisions results in the formation of the main apical–basal body axis and of major tissue types (protoderm, vasculature, and ground tissue initials) during embryo development. Tissue establishment is driven by TFs that initially become expressed during embryo development but are active throughout plant development, such as ARABIDOPSIS MERISTEM LAYER 1 and close homologs that specify the protoderm/epidermis. Major TFs controlling stem cell maintenance and organization become active during embryo development in the shoot and root apical meristems responsible for postembryonic development. This includes Arabidopsis class III homeodomain leucine zipper (HD-ZIP III) TFs and WUSCHEL, which are essential for shoot apical meristem formation, and PLETHORA TFs, which control the establishment of the root apical meristem.

Only a limited number of TFs have been described as specifically controlling embryo development. An important factor controlling embryonic identity is the nuclear transcription factor Y (NF-Y) factor LEAFY COTYLEDON 1 (LEC1). This factor not only controls different aspects of embryo development by stage-specific regulation of downstream target genes (107) but is also sufficient to induce embryonic programs in vegetative cells in the context of somatic embryogenesis. LEC1 encodes a B subunit of an NF-Y TF, and the B and C subunits of NF-Y possess a histone fold domain and form a deviant histone H2A–H2B dimer to facilitate a permissive chromatin conformation at promoters for the binding of other TFs (130). Another factor controlling embryonic development and triggering somatic embryogenesis is the AP2-like TF BABY BOOM (BBM, PLETHORA 4), known to also act in lateral root initiation. BBM controls auxin biosynthesis and responses during somatic embryogenesis (70). Auxin, in turn, was shown to rewire the cell totipotency network to trigger somatic embryogenesis by modifying chromatin accessibility, thereby enabling the access of embryonic TFs to specific downstream target genes (137).

A prerequisite for embryogenesis is the reprogramming of the chromatin landscape during gametogenesis. Male gametogenesis results in pollen that contains a sperm cell nucleus that will fertilize the egg cell and a vegetative nucleus that assists in pollen tube development. Sperm cell formation is associated with the global loss of repressive H2K27me3, resulting in a dynamic increase in chromatin accessibility at many genes, including regulators of embryo development, such as LEC1 and BBM (11) (Figure 2f). The accessibility of chromatin by removal of repressive H3K27me3 may also precede the activity of DEMETER DNA demethylase in the vegetative nucleus of pollen to enable the DNA binding of methylation-sensitive TFs (104).

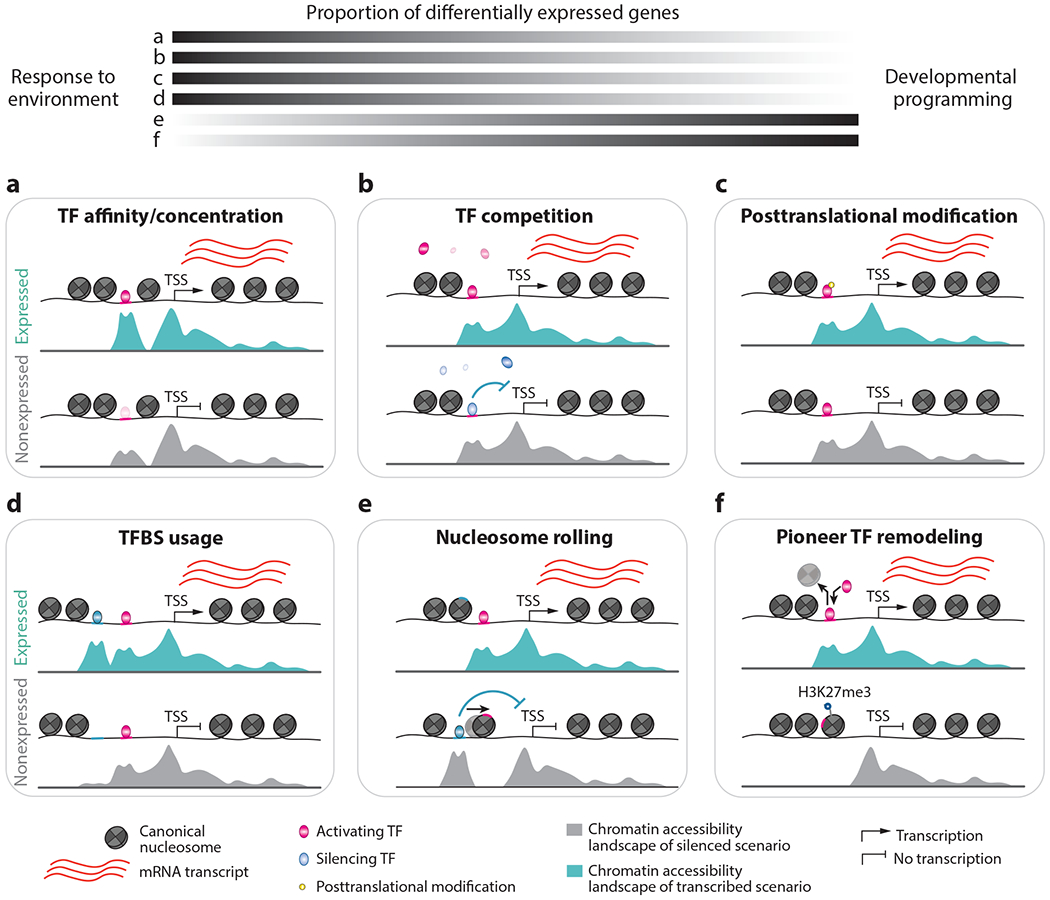

Figure 2.

Dynamic and static chromatin accessibility can underlie differential gene expression. Rapid, environmentally induced transcriptional changes are infrequently associated with widespread chromatin accessibility variation (a-c), in contrast to developmentally associated gene expression changes (d-f), which are more frequently attributed to chromatin remodeling. (a) A hypothetical locus with a strong TF affinity and/or TF nuclear concentration leads to greater chromatin accessibility and increased transcription. (b) Differential gene transcription arises due to differences in concentrations for competing TFs but causes no changes to chromatin accessibility. (c) Posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation or acetylation, to TFs can result in differential activation of transcription but cause no changes to chromatin accessibility. (d) The emergence of a shoulder peak in a broadly accessible domain due to TF binding leads to increased transcription. (e) The expression and binding of a silencing TF (blue) leads to nucleosome shifting and displacement of an activating TF (pink), resulting in gene silencing. There is novel chromatin accessibility in the non-expressed scenario. (f) An activating pioneer TF (pink) binds to nucleosomal DNA, leading to nucleosome eviction and activated transcription. There is novel chromatin accessibility in the transcribed scenario. Abbreviations: H3K27me3, histone 3 lysine 27 trimethylation; mRNA, messenger RNA; TF, transcription factor; TFBS, transcription factor binding site; TSS, transcription start site.

4.2. Postembryonic Development

Most plant developmental processes occur postembryonically, facilitated by stem cells that are located within various meristematic tissues in the shoot and root. Growth and cellular differentiation are controlled by networks of TFs and hormonal signaling that is modulated in an organ-specific manner by environmental factors, such as light and temperature. In Arabidopsis, profiling of chromatin accessibility in meristematic stem cells and differentiated leaf mesophyll cells revealed thousands of regions that quantitatively differed (120). Based on the overrepresentation of DNA-binding motifs, sets of TFs were identified that may coregulate target genes in the two cell types, including a predicted PIF, BES1-INTERACTING MYC-LIKE 1 (BIM1), and BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1 (BZR1) network. These factors are involved in light/temperature sensing (PIF, BIM1) and in brassinosteroid signaling (BZR1), and were previously shown to be involved in chloroplast biogenesis—a key aspect of mesophyll physiology. These findings are in line with observations of interconnected TF regulatory networks underlying root cell-type identity in Arabidopsis, including the shared enrichment of DNA-binding with one finger (DOF), cysteine-cysteine-cysteine-histidine zinc finger (C3H), and squamosa promoter binding protein (SBP) family TFs in phloem, xylem, and pericycle cells (28).

Protoplast-based ChIP-seq for 104 maize TFs that are expressed in leaves revealed almost 145,000 nonoverlapping TF binding sites, covering ~2% of the genome (134). A subset of these corresponded to highly occupied target (HOT) regions, previously defined as conserved sites of high TF binding density associated with developmentally controlled genes (45). For example, a HOT region in maize mapped to an important quantitative trait locus (QTL) genomic region, Vegetative to generative transition 1 (Vgt1), that controls flowering time (134). Vgt1 is a distal regulatory region located 70 kb upstream that controls expression of ZmRAP2.7. This large-scale ChIP-seq experiment revealed novel potential upstream regulators binding to Vgt1 that potentially modulate ZmRAP2.7 activity and thereby the transition to flowering in maize. Thus, identification of CRMs and cognate TFs is central to understanding the cis-regulatory code underlying developmental decisions in plants.

The transition from vegetative growth to flowering integrates information from external and internal cues via a network of transcriptional regulators and epigenetic factors. These pathways merge when the expression of central activators and repressors of the floral transition, such as FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) (141) and FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), are rewired (1, 161). This results in reprogramming of gene expression programs at the shoot apical meristem (39, 149). The initiation of flower development is mediated by master regulatory TFs such as LEAFY (LFY) and AP1, both of which can influence chromatin accessibility at their target sites in the genome, facilitating the access of other transcriptional regulators (103, 121, 143). LFY was recently shown to act as a pioneer factor capable of binding nucleosomal DNA (65). Among the earliest LFY and AP1 targets are homeotic TFs that specify the identities of floral organs and act in organ-specific tetrameric protein complexes. These TFs typically bind to several thousand regulatory regions, and different homeotic TF complexes may bind to partially overlapping sets of genomic targets (15). Organ-specific control of target gene expression may involve combinatorial regulation with non-MADS TFs (15). About 7,400 genes exhibit rapid changes in activity during flower development, emphasizing the global shifts in gene activity in this process (114). About 5,000 of these genes are directly bound by TFs with known roles in flower development from available ChIP-seq data (15). Particularly interesting, a number of these genes are bound by multiple TFs, evidence that HOT regions control developmental gene expression. Enhancer elements were more frequently found to be floral stage–specific in their activity than core promoters, and they contribute significantly to stage-specific gene expression programs (146). These findings were supported by an analysis of maize enhancers exhibiting greater cell-type specificity (86, 111).

4.3. Harnessing cis-Regulatory Variation in Development for Crop Improvement

The ability to fine-tune plant development either through precision breeding or genome engineering holds promise for accelerating crop improvement (132). Targeted modulation of morphological traits via their underlying developmental components can enhance crop productivity and tailor performance to diverse environments. The cis-regulatory space in crop genomes is an untapped repository for variation in gene regulation, including spatiotemporal specificity, which has been largely unexplored until very recently. Several examples of regulatory sequences controlling crop developmental gene expression have been discovered through QTL mapping in natural populations or with undomesticated wild relatives. For example, the genetic basis for apical dominance and repression of tiller outgrowth during maize domestication from its wild relative, teosinte, maps to the long-range enhancer upstream of the tb1 gene (127). Genetic variation in components of meristem maintenance and size pathways contributed to yield-related traits such as kernel row number, which remains an important breeding target (60). A major QTL for enhanced kernel row number, KRN4, was fine-mapped to a regulatory region ~60 kb downstream of the unbranched3 (ub3) gene encoding a SBP TF (78). Knockdowns of ub3 and its paralog ub2 increased kernel row number (17), supporting long-range regulation of ub3 in modulating meristem activity. In rice, an intergenic regulatory region (the SPR3 locus) was mapped as a large-effect QTL underlying a closed panicle phenotype—a product of domestication that confers less shattering and outcrossing due to more upright panicle branches and awns (50, 160). SPR3 is located ~10 kb upstream of the rice LIGULELESS1 (LG1) gene, which has pleiotropic effects on leaf angle and panicle branching (50, 160). A region syntenic to SPR3 in maize showed chromatin accessibility in developing tassel and ear primordia, but accessibility in the maize lg1 promoter was tissue specific and open only in the ear where lg1 is not expressed (105), suggesting regulation by repressor binding.

More recently, gene editing by CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been used to engineer cis-regulatory allelic diversity in promoters of important developmental genes that control meristem maintenance and determinacy in plants (79, 113). This technology provides a controlled way to fine-tune gene expression, generate allelic series in developmental phenotypes of agronomic impact, and uncover novel spatiotemporal functions. For example, the CLAVATA-WUSCHEL (CLV-WUS) feedback signaling pathway is a conserved circuit underlying the control of meristem size across monocots and dicots (122). Engineered edits that tiled the promoter region of tomato CLV3, a signaling peptide at the core of this pathway, uncovered a series of alleles with variations in floral organ and lodicule number, the latter resulting in variations in fruit size (113). Similarly, in maize, edits in promoter sequences of two genes encoding CLV3-like peptides generated a series of weak alleles with variations in meristem size and, consequently, yield-related traits including kernel row number (79).

Mutations in coding regions of core developmental genes tend to cause strong, pleiotropic phenotypes that are not desirable agronomically. Based on the concept of engineering allelic diversity, further work in tomato demonstrated that precise manipulation of cis-regulatory sequences upstream of the WUS HOMEOBOX 9 (WOX9) gene revealed hidden pleiotropy in its gene function, which was previously thought to be species specific (44). A variety of alleles were generated, resulting in plants that display a wide spectrum of vegetative and reproductive meristem defects. Integration of ATAC-seq data revealed that individual pleiotropic gene functions in vegetative and reproductive development were associated with edits in specific regions of accessible chromatin overlapping with conserved CREs (44). Indeed, some of these phenotypes are likely associated with loss of TF binding sites, demonstrating that pleiotropic phenotypes can be decoupled by manipulating cis-regulatory architecture. These findings have important implications for agriculture and understanding the basis of evolution and development. In rice, IDEAL PLANT ARCHITECTURE1 (IPA1) encodes an SBP TF that is orthologous to maize ub3 and a master regulator of plant architecture (52, 92). Gain-of-function alleles have positive effects on several morphological characteristics such as panicle size, thickened culm, and reduced ineffective tillers; however, a trade-off exists between panicle size and tiller number, which limits yield potential (153). Recent work leveraging a CRISPR-Cas9 strategy to tile deletions in CREs of IPA1 revealed tissue-specific control of its gene expression, which modulated changes in pleiotropic effect and resulted in diverse tiller number and panicle size phenotypic combinations (124).

Another example of natural variation in gene regulatory space contributing to increased grain yield in rice involves the precise regulation of axillary meristem determinacy pathways. Copy number variation in an upstream silencer of the FRIZZY PANICLE (FZP) spikelet meristem identity gene (61) was mapped as a causal locus for increased numbers of spikelets per panicle, resulting in a 15% increase in grain yield (7). Cultivars harboring tandem binding sites for the BZR1 TF in a regulatory region ~5.6 kb upstream of FZP showed yield increases due to reducing expression of FZP in a dose-dependent manner. Modulated repression of FZP delays the conversion of indeterminate branching, allowing for more branch meristems to be initiated before FZP confers spikelet identity, determining the number of spikelets and thereby grain that can be produced per panicle (7). Interestingly, another study mapped a similar phenotype in rice to a regulatory region ~2.7 kb upstream of FZP, which also harbored copy number variation but in ARF TF binding sites; decreased ARF binding caused increased repression of FZP and more secondary panicle branches (47). FZP is a highly conserved meristem identity gene in grass inflorescence development, and these studies highlight the potential for fine-tuning panicle architecture through its cis-regulatory transcriptional control.

5. ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSES

Dynamic gene regulation often occurs in response to environmental conditions. Detailed molecular studies have identified many TFs and cognate binding sites important for responses to environmental conditions such as light, heat, cold, drought, salt, or nutrient stress (26, 152). While these studies have been critical for developing models of stress-responsive gene regulation, it has been challenging to apply this knowledge to predict genome-wide responses to stress. Here we highlight recent studies of chromatin and transcription dynamics in response to environmental stress.

An analysis of DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs) in Arabidopsis plants subjected to different light regimes or heat stress identified examples of dynamic chromatin (128). During photomorphogenesis, regions with variable accessibility are enriched for specific TF binding sites (128). The same study also identified a set of DHSs that are present only after a 30-minute heat shock treatment. Profiling of accessible chromatin in Arabidopsis plants under heat, cold, salt, or drought stress identified examples of consistent and dynamic chromatin accessibility (109). The frequency of regions with variable accessibility differs substantially for different stress treatments. For example, drought or salt treatments were associated with limited gains of accessibility, while heat or cold stress resulted in a global increase of accessible chromatin (109). An analysis of chromatin accessibility in potato tuber tissue subjected to long-term cold stress identified many regions with increased accessibility after cold stress treatment (151). Most cold-specific accessible regions are found within genes associated with increased expression in cold-treated tissues. Rice root tissues subjected to distinct water stress conditions revealed examples of dynamic accessibility in response to the environment (110). However, examples of dynamic chromatin accessibility often represent quantitative variation in accessibility rather than gain or loss of unique accessible regions (110). This study also included profiles of samples with a 24-hour recovery period following the stress, revealing that chromatin accessibility often reverts to prestress configurations (110). An analysis of heat shock factors in maize and Setaria indicated that while many genes are strongly induced by heat stress, chromatin accessibility variation in response to heat stress is limited (94). However, a combined analysis of three-dimensional spatial organization and chromatin accessibility uncovered dynamic changes in the response to heat stress in rice (72).

Analyses of chromatin accessibility dynamics in response to environmental conditions are just beginning to catalog genome-wide stress response CREs. One avenue is to incorporate chromatin accessibility with motif analysis to predict gene expression responses. In Arabidopsis, the incorporation of chromatin data improved the performance of machine learning models for predicting responses to drought and heat (6). In maize, however, the use of chromatin accessibility data derived from plants grown in control conditions does not improve predictions of heat or cold stress responses (158). In sorghum, drought-responsive accessible chromatin signatures were enriched for ABSCISIC ACID RESPONSE ELEMENT (ABRE)-binding sites and used to constrain gene regulatory network predictions for abscisic acid–dependent transcriptional cascades (106). Further analyses using dynamic chromatin accessibility in both control and stress samples may provide insights into whether chromatin data can improve stress-response predictions.

Dynamic chromatin accessibility is often enriched near differentially expressed genes in response to stress. However, it is worth highlighting several caveats. First, most differential accessibility in response to stress represents a quantitative change to accessibility at already accessible loci, suggesting dynamic shifts in cell populations (Figure 2d). These regions may have limited TF binding and stochastic accessibility in control conditions such that only a small portion of cells have accessibility. During stress, there may be increased TF expression and occupancy, resulting in a greater proportion of cells with accessibility. Second, many genes with altered expression do not display any detectable changes to chromatin accessibility. Instead, many stress-induced genes display chromatin accessibility similar to control conditions (Figure 2b,c). This suggests that preexisting chromatin accessibility allows for the potential of an expression response. Evaluating the patterns of chromatin accessibility in control and stress conditions can also reveal subtle differences with potential shoulder peaks within the accessible region (Figure 2d–f). This could reflect the usage of novel CREs within a larger CRM in the stress condition. Together, these observations highlight that nuanced approaches are necessary to monitor chromatin accessibility dynamics in response to environmental conditions.

6. VARIATION IN CIS-REGULATORY ELEMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH EVOLUTION AND ADAPTATION

In prior sections, we focused primarily on the dynamics of CRMs and accessible chromatin in different cell types, developmental stages, and environments. In these comparisons, the underlying DNA sequence remains constant, while chromatin and gene expression can vary. In this section, we consider variation among individuals with distinct genomic sequences. While there have been detailed reports of CRMs creating trait variation in animal species (63, 80, 84, 147), researchers are just beginning to understand the role of cis-regulatory evolution in plant populations and between related species.

6.1. Natural Variation Within Species

Genetic variation among individuals of the same species provides opportunities for natural or artificial selection. Most plant breeding efforts rely upon combining natural variation to develop improved varieties. Analyses of major-effect QTLs from plant domestication have revealed several examples of selection acting upon changes in CRMs (19, 115). Several recent studies have assessed patterns of genetic diversity within putative regulatory elements from a reference genome to find evidence for selection on gene expression (55, 142, 148).

Recent investigations are beginning to shed light on the extent of natural variation within CREs. A comparison of four maize genotypes revealed that ACRs are enriched in conserved portions of the genome with limited structural variation (98). While many ACRs and UMRs are conserved, there are examples of genotype-specific chromatin properties, including variable boundaries for conserved UMRs and ACRs. A recent report of 26 maize genomes included documentation of ACRs in each genotype but did not perform a detailed characterization of the conservation and variability (48). Comparisons of chromatin accessibility within plant diversity panels promise to reveal variable CRMs necessary for understanding genetic and epigenetic factors contributing to gene expression variation.

6.2. Variation Between Species and Evolution of cis-Regulatory Elements

Comparative genomics of distinct species generally reveals conservation of gene sequences and order with substantially lower conservation of intergenic sequence. However, careful examination has identified numerous conserved noncoding sequences (CNSs), implying functional properties (33, 42, 57, 64, 123, 135). CNSs generally colocalize with ACRs (111) and sequence changes in CNSs are associated with altered gene expression (123), suggesting that many CNSs are functional CRMs.

Two recent studies have assessed chromatin accessibility across multiple plant species (83, 85). Evaluation of ACR locations in Arabidopsis, Medicago, tomato, and rice showed enrichment in gene proximal regions. However, the proportion of ACRs near TSSs decreases in larger genomes, suggesting that species with more intergenic space have increased proportions of distal CRMs. Comparisons of orthologous genes revealed limited conservation in the number, position, and sequence of ACRs in different species, even though genes often exhibit similar expression patterns and are likely coregulated by similar suites of TFs (85). These results were further supported by a recent study of chromatin accessibility and histone modifications in 13 angiosperm species (83) that showed ~66% of gene-distal ACRs were present across syntenic gene pairs. Comparisons of maize and sorghum syntenic orthologs revealed examples of ACRs at conserved sequences. However, the distance between ACRs and cognate TSSs is often highly variable due to proliferation and contraction of TEs, making similar analyses challenging at greater evolutionary distances (83).

6.3. Understanding the Sources of cis-Regulatory Module Creation

There are many examples of novel gene expression patterns revealed through intraspecific or interspecific comparisons. These include novel tissue-specific or developmental patterns of expression with major effects on plant architecture traits (127) as well as novel responsiveness to environmental conditions (81, 139). While gene expression studies have uncovered several examples tying allelic variation to expression patterns, an understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying variation in CRMs remains limited. It is possible that some regulatory changes reflect epigenetic modifications that do not require sequence alteration. For example, vernalization in Arabidopsis changes the activity of CRMs based upon prolonged exposure to cold stress (59). The presence of ACRs could be a semiheritable property that could be altered with little or no change in DNA sequence.

While epigenetics could contribute to variable gene expression, it is likely that most examples of novel expression patterns are due to altered sequences. A key question is, How are novel CRMs created? Novel CRMs can provide the source material for evolution and selection to act to generate new traits. There are likely two distinct types of sequence variation underlying functional alterations in CRMs. First, single-nucleotide polymorphisms and small insertions/deletions may quantitatively change TF binding affinity, potentially altering the strength and activity of CRMs and downstream phenotypes. Second, sequence variation can occur due to larger insertions. An insertion can affect CRMs through a variety of mechanisms. The insertion could fully contain a CRM coopted by a nearby gene, the junction of the insertion could create a novel CRM, or insertions could disrupt combinatorial TF interactions or change the relative position of a CRM and the TSS, resulting in altered activity.

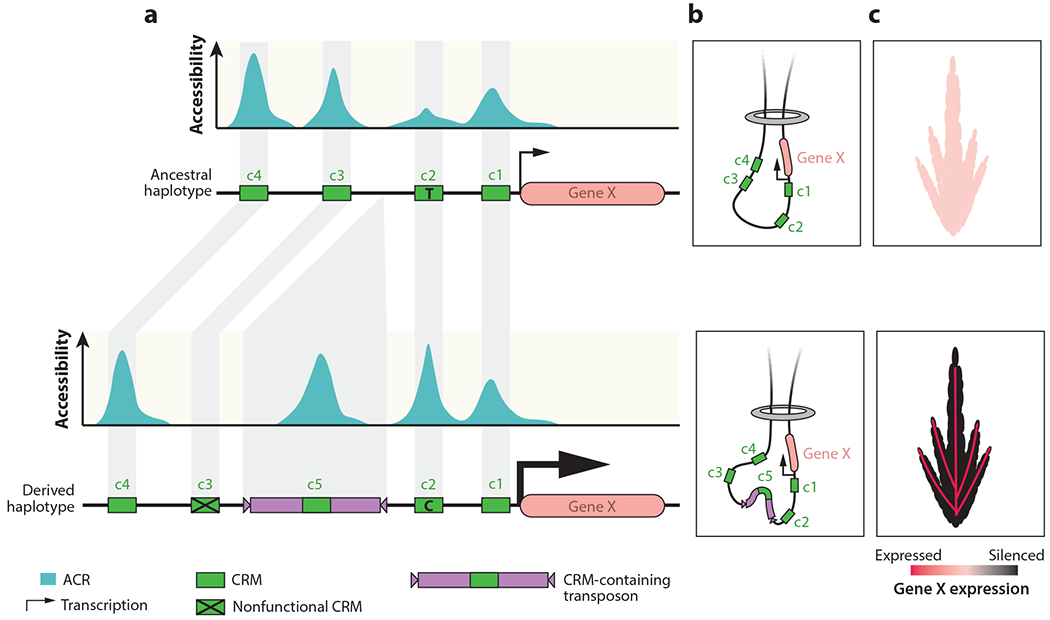

Comparisons among haplotypes within a species or syntenic regions of related species have uncovered widespread variation in the presence of transposons (3, 131). Transposon insertions can influence gene expression through a variety of mechanisms (18, 32, 46, 74, 75), but here we will discuss the potential for transposons to create novel CRMs. Most TEs are highly methylated with inaccessible chromatin. However, in many plant genomes, TEs account for greater than tenfold more of the genome space than genes (118). As a result, a small proportion of transposons affording chromatin accessibility can account for a substantial proportion of all ACRs. Several chromatin accessibility data sets have provided evidence for putative CRMs within transposons. While maize transposons are depleted of ACRs in general, the absolute counts of ACRs within TEs are substantial (99, 101, 156). Depending on the approach used, these studies found that 8–33% of putative CRMs were located within TEs. A single-cell analysis revealed that ACRs located within TEs tend to be highly cell-type specific, especially for more ancient TE insertions (86). The in vivo activity of maize transposon-derived CRMs has also been validated via protoplast-based green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter assays (156). CRMs located within transposons may function to regulate transposon-derived transcripts, as evidenced by the identification of dynamic tissue-specific expression of many transposons (4). However, these CRMs may also influence the expression of nearby genes. Haplotypes carrying TE-derived ACRs are associated with higher expression of nearby genes (99). TE movement may play a critical role in generating novel CRMs near genes (Figure 3). Over evolutionary scales, transposon sequences might be lost or altered. However, TEs containing CRMs may provide a selectable advantage and are more likely to be retained. Further studies will be important to document the role of transposons and other genetic mechanisms in the creation of novel CRMs.

Figure 3.

Evolution of CRMs and chromatin accessibility. (a) Hypothetical ancestral (top) and derived (bottom) haplotypes are shown. The ancestral haplotype has several ACRs (turquoise) over CRMs (green) and is moderately but broadly expressed. The derived haplotype has genetic variation including SNPs and a transposon insertion containing a novel CRM (purple and green rectangle), resulting in enhanced cell-type-specific expression. The size of the transcription arrow shows the relative expression level. (b) A tissue-constitutive CRE (c3) has lost activity because it no longer interacts with the promoter. There is a novel ACR/CRM located within the transposon (c5), as well as a quantitative gain of accessibility in another ACR (c2) due to a SNP that increases TF binding stability within the CRM. (c) These changes result in distinct spatiotemporal patterns of transcription. Abbreviations: ACR, accessible chromatin region; CRE, cis-regulatory element; CRM, cis-regulatory module; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; TF, transcription factor.

SUMMARY POINTS.

Advances in chromatin accessibility profiling have rapidly expanded the cis-regulatory lexicon of plant species.

Chromatin profiling, functional assays, and genetic perturbations are beginning to untangle diverse cis-element classes.

Chromatin accessibility variation of cis-regulatory elements allows a unique interpretation of the genome in diverse cellular contexts within an organism.

Gene expression programs underlying development are coordinated by cis-elements and can be exploited for crop improvement efforts.

Changes to chromatin accessibility are subtle in response to environmental cues.

Genetic variations can alter activity and birth cis-regulatory modules de novo that impact transcription, providing the substrate for natural and artificial selection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A.P.M. was supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) postdoctoral fellowship in biology (DBI-1905869) and a National Institutes of Health Pathway to Independence Award (1K99GM144742). A.L.E. was supported by an NSF Plant Genome Program award (IOS-1733606) and a Department of Energy Biological and Environmental Research award (DE-SC0020401). K.K. would like to thank the German Research Foundation for funding (project numbers 316736798, 438774542, 458750707). N.M.S. was supported by an NSF Plant Genome Program award (IOS-1733633).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Glossary

- Chromatin

nuclear mixture of DNA, RNA, and protein

- CRE

cis-regulatory element

- Motif

consensus sequence recognized by transcription factors

- TF

transcription factor

- CRM

cis-regulatory module

- Nucleosome

octamer of histone proteins bound to ~147 base pairs of DNA

- ACR

accessible chromatin region

- Chromatin loops

three-dimensional interaction between distal chromatin regions

- Topology-associated domains (TADs)

correspond to genomic regions with increased intra-interaction frequencies relative to adjacent regions

- Footprint

nuclease-protected sequences bound by transcription factors

- Cistrome

genome-wide set of cis-acting targets of a trans-acting factor

- Transposable element (TE)

mobile genetic elements capable of copying and pasting or replicating their cognate DNA sequences

- UMR

unmethylated region

- Epigenetics

heritable changes to gene epression in the absence of DNA alterations

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Adrian J, Farrona S, Reimer JJ, Albani MC, Coupland G, Turck F. 2010. cis-Regulatory elements and chromatin state coordinately control temporal and spatial expression of FLOWERING LOCUS T in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22:1425–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez JM, Schinke A-L, Brooks MD, Pasquino A, Leonelli L, et al. 2020. Transient genome-wide interactions of the master transcription factor NLP7 initiate a rapid nitrogen-response cascade. Nat. Commun 11:1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson SN, Stitzer MC, Brohammer AB, Zhou P, Noshay JM, et al. 2019. Transposable elements contribute to dynamic genome content in maize. Plant J. 100:1052–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson SN, Stitzer MC, Zhou P, Ross-Ibarra J, Hirsch CD, Springer NM. 2019. Dynamic patterns of transcript abundance of transposable element families in maize. G3 9:3673–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold CD, Gerlach D, Stelzer C, Boryn LM, Rath M, Stark A. 2013. Genome-wide quantitative enhancer activity maps identified by STARR-seq. Science 339:1074–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azodi CB, Lloyd JP, Shiu SH. 2020. The cis-regulatory codes of response to combined heat and drought stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. NAR Genom. Bioinform 2:lqaa049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai X, Huang Y, Hu Y, Liu H, Zhang B, et al. 2017. Duplication of an upstream silencer of FZP increases grain yield in rice. Nat Plants 3:885–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartman CR, Hsu SC, Hsiung CC, Raj A, Blobel GA. 2016. Enhancer regulation of transcriptional bursting parameters revealed by forced chromatin looping. Mol. Cell 62:237—47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bewick AJ, Schmitz RJ. 2017. Gene body DNA methylation in plants. Cum. Opin. Plant Biol 36:103–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolduc N, Yilmaz A, Mejia-Guerra MK, Morohashi K, O’Connor D, et al. 2012. Unraveling the KNOTTED 1 regulatory network in maize meristems. Genes Dev. 26:1685–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borg M, Papareddy RK, Dombey R, Axelsson E, Nodine MD, et al. 2021. Epigenetic reprogramming rewires transcription during the alternation of generations in Arabidopsis. eLife 10:e61894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyle AP, Davis S, Shulha HP, Meltzer P, Margulies EH, et al. 2008. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell 132:311–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Litzenburger UM, Ruff D, Gonzales ML, et al. 2015. Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals principles of regulatory variation. Nature 523:486–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai YC, Zhang Y, Loh YP, Tng JQ, Lim MC, et al. 2021. H3 K27me3-rich genomic regions can function as silencers to repress gene expression via chromatin interactions. Nat. Commun 12:719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen DJ, Yan WH, Fu L-Y, Kaufmann K. 2018. Architecture of gene regulatory networks controlling flower development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Commun 9:4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chubb JR, Trcek T, Shenoy SM, Singer RH. 2006. Transcriptional pulsing of a developmental gene. Curr Biol 16:1018–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chuck GS, Brown PJ, Meeley R, Hake S. 2014. Maize SBP-box transcription factors unbranched2 and unbranched3 affect yield traits by regulating the rate of lateral primordia initiation. PNAS 111:18775–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuong EB, Elde NC, Feschotte C. 2017. Regulatory activities of transposable elements: from conflicts to benefits. Nat. Rev. Genet 18:71–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark RM, Wagler TN, Quijada P, Doebley J. 2006. A distant upstream enhancer at the maize domestication gene tbl has pleiotropic effects on plant and inflorescent architecture. Nat. Genet 38:594—97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Concia L, Veluchamy A, Ramirez-Prado JS, Martin-Ramirez A, Huang Y, et al. 2020. Wheat chromatin architecture is organized in genome territories and transcription factories. Genome Biol. 21:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford GE, Holt IE, Mullikin JC, Tai D, Green ED, et al. 2004. Identifying gene regulatory elements by genome-wide recovery of DNase hypersensitive sites. PNAS 101:992–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford GE, Holt IE, Whittle J, Webb BD, Tai D, et al. 2006. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS). Genome Res. 16:123–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crisp PA, Marand AP, Noshay JM, Zhou P, Lu ZF, et al. 2020. Stable unmethylated DNA demarcates expressed genes and their cis-regulatory space in plant genomes. PNAS 117:23991–4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Demonstrated that stable unmethylated regions capture potentially comprehensive catalogs of cis-regulatory elements in plant genomes.

- 24.Cuperus JT. 2022. Single-cell genomics in plants: current state, future directions, and hurdles to overcome. Plant Physiol. 188:749–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cusanovich DA, Daza R, Adey A, Pliner HA, Christiansen L, et al. 2015. Multiplex single-cell profiling of chromatin accessibility by combinatorial cellular indexing. Science 348:910–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding Y, Yang S. 2022. Surviving and thriving: how plants perceive and respond to temperature stress. Dev. Cell 57:947–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong Q, Li N, Li X, Yuan Z, Xie D, et al. 2018. Genome-wide Hi-C analysis reveals extensive hierarchical chromatin interactions in rice. Plant J. 94:1141–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorrity MW, Alexandre CM, Hamm MO, Vigil A-L, Fields S, et al. 2021. The regulatory landscape of Arabidopsis thaliana roots at single-cell resolution. Nat. Commun 12:3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, Collins PJ, Davis C, et al. 2012. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489:57–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farmer A, Thibivilliers S, Ryu KH, Schiefelbein J, Libault M. 2021. Single-nucleus RNA and ATAC sequencing reveals the impact of chromatin accessibility on gene expression in Arabidopsis roots at the single-cell level. Mol. Plant 14:372–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng Y,Zhang Y, Ebright RH. 2016. Structural basis of transcription activation. Science 352:1330–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feschotte C 2008. Transposable elements and the evolution of regulatory networks. Nat. Rev. Genet 9:397—405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeling M, Subramaniam S. 2009. Conserved noncoding sequences (CNSs) in higher plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 12:126–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galli M, Khakhar A, Lu Z, Chen Z, Sen S, et al. 2018. The DNA binding landscape of the maize AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR family. Nat. Commun 9:4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gent JI, Ellis NA, Guo L, Harkess AE, Yao Y, et al. 2013. CHH islands: de novo DNA methylation in near-gene chromatin regulation in maize. Genome Res. 23:628–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gent JI, Madzima TF, Bader R, Kent MR, Zhang XY, et al. 2014. Accessible DNA and relative depletion of H3K9me2 at maize loci undergoing RNA-directed DNA methylation. Plant Cell 26:4903–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilmour DS, Lis JT. 1984. Detecting protein-DNA interactions in vivo: distribution of RNA polymerase on specific bacterial genes. PNAS 81:4275–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gómez-Zambrano A, Merini W, Calonje M. 2019. The repressive role of Arabidopsis H2A.Z in transcriptional regulation depends on AtBMI1 activity. Nat. Commun 10:2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutzat R, Rembart K, Nussbaumer T, Hofmann F, Pisupati R, et al. 2020. Arabidopsis shoot stem cells display dynamic transcription and DNA methylation patterns. EMBO J. 39:e103667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haberle V, Stark A. 2018. Eukaryotic core promoters and the functional basis of transcription initiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 19:621–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hampsey M 1998. Molecular genetics of the RNA polymerase II general transcriptional machinery. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 62:465–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haudry A, Platts AE, Vello E, Hoen DR, Leclercq M, et al. 2013. An atlas of over 90,000 conserved noncoding sequences provides insight into crucifer regulatory regions. Nat. Genet 45:891–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heintzman ND, Hon GC, Hawkins RD, Kheradpour P, Stark A, et al. 2009. Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature 459:108–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hendelman A, Zebell S, Rodriguez-Leal D, Dukler N, Robitaille G, et al. 2021. Conserved pleiotropy of an ancient plant homeobox gene uncovered by cis-regulatory dissection. Cell 184:1724–39.e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heyndrickx KS, Van de Velde J, Wang CM, Weigei D, Vandepoele K. 2014. A functional and evolutionary perspective on transcription factor binding in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 26:3894—910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirsch CD, Springer NM. 2017. Transposable element influences on gene expression in plants. Biochim.Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech 1860:157–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang Y, Zhao S, Fu Y, Sun H, Ma X, et al. 2018. Variation in the regulatory region of FZP causes increases in secondary inflorescence branching and grain yield in rice domestication. Plant J. 96:716–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hufford MB, Seetharam AS, Woodhouse MR, Chougule KM, Ou S, et al. 2021. De novo assembly, annotation, and comparative analysis of 26 diverse maize genomes. Science 373:655–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Inada DC, Bashir A, Lee C, Thomas BC, Ko C, et al. 2003. Conserved noncoding sequences in the grasses. Genome Res. 13:2030–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]