Abstract

Peritoneal mesothelioma is an aggressive disease with a median survival of under three years, due to a lack of effective treatment options. Mesothelioma is traditionally considered a “chemoresistant” tumor; however, low intratumoral drug levels coupled with the inability to administer high systemic doses suggests that therapeutic resistance may be due to poor drug delivery rather than inherent biology. While patient survival may improve with repetitive local intraperitoneal infusions of chemotherapy throughout the perioperative period, these regimens carry associated toxicities and significant peri-operative morbidity. To circumvent these issues, we describe ultra-high drug loaded nanoparticles (NPs) composed of a unique poly(1,2-glycerol carbonate)-graft-succinate-paclitaxel (PGC-PTX+PTX) conjugate. PGC-PTX+PTX NPs are cytotoxic, localize to tumor in vivo, and improve survival in a murine model of human peritoneal mesothelioma after a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection compared to multiple weekly doses of the clinically utilized formulation PTX-C/E. Given their unique pharmacokinetics, a second intraperitoneal dose of PGC-PTX+PTX NPs one month later more than doubles the overall survival compared to the clinical control (122 versus 58 days). These results validate the clinical potential of prolonged local paclitaxel to treat intracavitary malignancies such as mesothelioma using a tailored polymer-mediated nanoparticle formulation.

Keywords: drug delivery, mesothelioma, peritoneal, high drug loadings, paclitaxel

1. Introduction

Mesothelioma is an aggressive and rare disease, arising from the mesothelial lining of the chest or abdomen, and is associated with environmental exposures to asbestos in a subset of patients. It is nearly universally fatal due to relentless local progression of disease [1–3]. Spreading diffusely along the peritoneum, malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPeM) accounts for roughly one in four cases of mesothelioma. Given the inability to diagnose the disease early, to surgically resect all microscopic disease, or to effectively treat with systemic agents, the median survival time is no more than 3 years [4–6].

Currently, systemic delivery (intravenous infusion, IV) of chemotherapeutics demonstrates at best limited efficacy against peritoneal or pleural mesothelioma, and the off-target toxicities limit dosing and increase morbidity with these agents [7,8]. Cytoreductive surgery combined with intracavitary localized paclitaxel treatments can afford promising results in patients with both pleural mesothelioma [9] and peritoneal mesothelioma but are limited by high morbidity and local failure rates [10]. Paclitaxel (PTX) was chosen specifically for intraperitoneal (IP) administration due to its high molecular weight, which culminates in a longer retention period within the peritoneal space (t1/2 IV = 4.7 ± 3.3 hrs, t1/2 IP = 28.7 ± 8.7 hrs) [11,12]. Studies led by Dr. Paul Sugarbaker showed that local paclitaxel, in the setting of multimodal therapy, can improve disease-free survival for peritoneal mesothelioma. However, short-term treatment during surgical debulking is insufficient for disease control [13]. A prolonged multi-dose regimen can improve survival, but at the expense of increased morbidity. Specifically, management of peritoneal mesothelioma is proposed to require a combination of cytoreductive surgery, hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIIC), subsequent early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (EPIC), and long-term normothermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (NIPEC-LT) consisting of PTX infusions for up to 6 months. While NIPEC-LT increases the 5-year survival, up to 70% in some studies [13–16], these regimens demonstrate a 35% incidence of major postoperative morbidity and significantly limit clinical benefit in patients with suboptimal cytoreduction [3,17]. A significant percentage of patients are unable to complete the adjuvant treatment regimen due to infection and wound complications or other treatment related side-effects. Although intraperitoneal therapy appears to be the treatment of choice with proof of concept that local high dose paclitaxel is effective against mesothelioma when delivered over a substantially long timeframe, the current multiple-dose treatment within the peritoneal cavity following surgery is poorly tolerated, carries significant morbidity, and is insufficiently efficacious. Thus, we describe a tailored drug delivery platform specifically designed for the routinely encountered clinical scenarios and disease biology of peritoneal mesothelioma in order to improve outcomes.

The anti-tumor efficacy of many chemotherapeutic agents, including PTX, depends on both the local concentration in tumor tissue and the duration of exposure to the agents at or above the minimum cytotoxic level. The clinical formulation for PTX, Taxol™, utilizes a polyethoxylated castor oil (a mixture of Cremophor EL and ethanol, abbreviated as PTX-C/E) to increase drug solubility and improve pharmacokinetics of delivery [12]. However, this formulation can cause dose-limiting toxicities such as severe anaphylactoid hypersensitivity reactions, blood disorders, hyperlipidemia, and peripheral neuropathy [18]. Additionally, PTX-C/E exhibits a short duration of exposure in vivo due to clearance via hepatic metabolism, resulting in subtherapeutic concentrations within the tumor and necessitating multiple infusions over several weeks/months [19]. Nanoparticles (NPs) can efficiently enhance chemotherapeutic delivery by improving solubility, increasing tumor site concentrations and prolonging exposure durations, while decreasing systemic side-effects [20–30]. A prime example is albumin-coated PTX nanoparticles (Abraxane™) which demonstrate clinical success against breast, lung, and pancreatic cancers [31–36]. In a human breast xenograft tumor model, it affords slightly higher, 33%, tumor accumulation than PTX-C/E, and prevents tumor recurrence when given at twice the dose of PTX-C/E [37]. The need for administration of twice the dose is likely tied to the release of PTX from the albumin-coated nanoparticle, which is rapid upon administration and subsequent dilution [38]. In vivo, Abraxane™ has been found to have a similar pharmacokinetic profile as PTX-C/E [39,40]. For these reasons, Abraxane™ has not been clinically used for the treatment of mesothelioma.

To date, there is minimal work on nanoparticle optimization for the treatment of mesothelioma specifically, however several groups are investigating generalized concepts to treat peritoneal carcinomatosis and ovarian cancer [41]. Sugarbaker et al. explored clinically the use of pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin for both EPIC and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) applications, but despite an increase in doxorubicin uptake, the pharmacokinetics were less than ideal and not well suited for HIPEC [42]. Simón-Gracia et al. developed PTX-loaded polymersomes that significantly decrease both primary tumor and metastasis after three weeks in a murine model of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Yet three administrations of the NPs per week were required to obtain these results [43]. Both Xiao et al. and Zhai et al. developed promising self-assembling PTX-loaded NPs to treat ovarian cancer, however they were ultimately not significantly different than clinical controls in their in vivo models [44,45]. In general, existing NPs are limited by one or more of the following: suboptimal tumor targeting, poor bioavailability, rapid-drug release, or low drug loading (<10wt%).

To address the unmet need for a local, sustained drug delivery system for the treatment of intraperitoneal mesothelioma, our group explored paclitaxel delivery via pH-responsive nanoparticles, termed ‘expansile nanoparticles’ (eNPs) [46–50]. These eNPs expand in volume under slightly acid-conditions, such as found in the tumor microenvironment, and when swollen, release their encapsulated contents. However, despite initial success in mesothelioma tumor models, the substantial release (> 90%) of the drug payload within 24 hours results in limited long term survival of animals (i.e., 20%) or necessitates 8 administrations to achieve 50% survival at 100 days [51–53]. Therefore, in order to maintain the therapeutic effect against mesothelioma for a longer period of time, we developed a new NP composition containing both covalently bound and encapsulated drug.

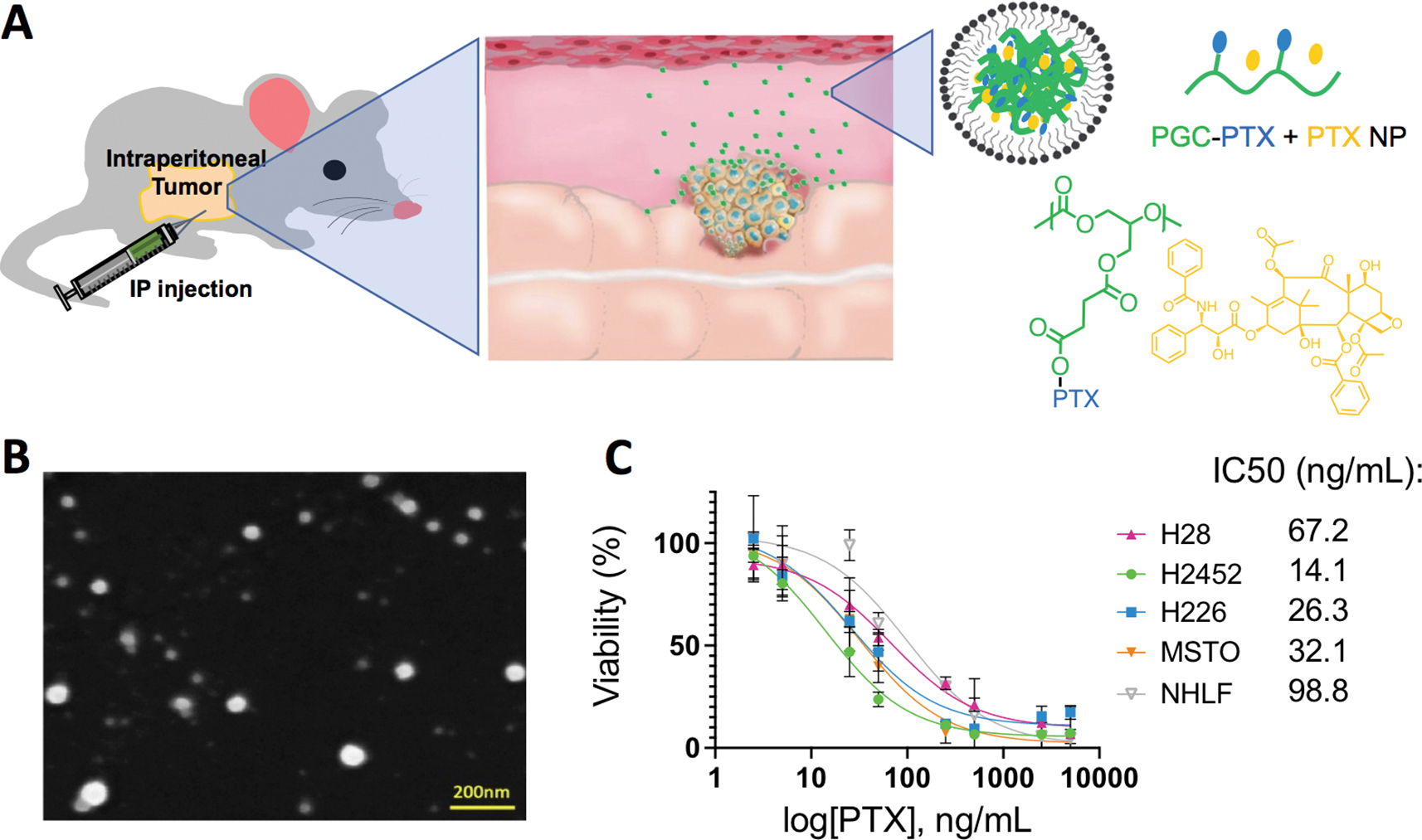

We report the successful in vivo utilization of a synthesized polymeric nanoparticle system designed to achieve tumor-specific delivery of ultrahigh PTX concentrations to the site of diffuse peritoneal mesothelioma implants over a prolonged period of time (Figure 1). Specifically, we use a biodegradable polymer comprised of glycerol, CO2, succinic acid, and paclitaxel building blocks, termed poly(1,2-glycerol carbonate)-graft-succinic acid-paclitaxel (PGC-PTX), to form NPs. By additionally entrapping free PTX within the NP core, we create ultra-high loaded “PGC-PTX+PTX NPs”. These NPs encapsulate over 75 wt% PTX, as the mass of the drug is greater than the mass of the carrier [54], and generate the desired greater initial release, while simultaneously maintaining therapeutic levels long-term due to cleavage of the chemically conjugated PTX over time. In this study, we assess the pharmacokinetic (PK) and biodistribution of PTX delivery of these PGC-PTX+PTX NPs and demonstrate improved in vitro and in vivo efficacy of a multi-dose regimen, as compared to standard PTX dosing, with markedly prolonged survival in a murine xenograft model of human peritoneal mesothelioma.

Fig. 1.

Characterization and depiction of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs. a) Schematics of an IP injection of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs. b) SEM images of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs. Scale bar = 200 nm. c) Cellular viability after 3 days of incubation in vitro of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs with H2452, H226, H28, MSTO-211H, and NHLF.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthesis of PGC-PTX

Poly(1,2-glycerol carbonate) (PGC) was synthesized following a previously optimized procedure [55] using an alternating copolymerization of epoxide and CO2. Once polymerized, the primary alcohol on the PGC polymer was deprotected via hydrogenation, and immediately conjugated with succinic anhydride to synthesize poly(1,2-glycerol carbonate)-graft-succinic acid (PGC-SA). PGC (100 mg, 0.85 mmol, 1.0 eq.), succinic anhydride (93 mg, 0.93 mmol, 1.1 eq.), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (5.2 mg, 0.042 mmol, 0.05 eq.), and dimethylformamide (DMF; 1 mL) were added into a 5 mL glass vial and stirred at room temperature overnight before being purified via precipitation in diethyl ether (2x). After centrifugation, the upper layer was decanted, and the solid re-dissolved with dichloromethane (DCM). The isolated polymer was dried under vacuum overnight, and isolated as a white foam. To synthesize PGC-PTX with 34 mol% PTX loading, the purified PGC-SA (100 mg, 0.459 mmol, 1.0 eq.), PTX (157 mg, 0.183 mmol, 0.4 eq.), N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) (42 mg, 0.202 mmol, 0.44 eq.), and 1 mL DMF were added into a 5 mL glass vile. The reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight, then filtered using a 0.2 μm Millex-GN nylon syringe filter (EMD Millipore; Billerica, MA) to remove precipitated dicyclohexylurea (DCU), and again purified via precipitation in diethyl ether (2x). The conjugate was isolated as a white powder (172 mg, 75% from PGC-SA). Polymer and PTX loading were verified via nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR; Figure S1), while polymer length was evaluated via gas permeation chromatography (GPC; Mw = 14847 g/mol; Đ = 1.04). Reagents and supplies were obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific Inc. unless specified.

2.2. Preparation of PGC-PTX + PTX NPs

Nanoparticles (NPs) were formulated using a previously described miniemulsion procedure [56]. 34 mol% PGC-PTX (50.0 mg) and free PTX (12.5 mg) were dissolved in 0.5 mL DCM and added to a 2 mL solution of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 10mg) in pH 7.4 10 mM phosphate buffer. The mixture was emulsified under argon using a Sonics Vibra-Cell VCX-600 Ultrasonic Processor (Sonics & Materials; Newtown, CT). Following sonication, the NPs were stirred under argon for 2 hours, followed by stirring under air overnight to allow for the evaporation of the DCM. The resulting NP suspension was dialyzed for 24 hours against 1 L of 5 mM pH 7.4 phosphate buffer, exchanged twice to ensure sink conditions. Nanoparticle formation was verified via dynamic light scattering (DLS) to determine size and distribution. Drug loading is defined as follows:

| (1) |

In equation 1, mdrug and mcarrier correspond to the mass of the encapsulated drug and the mass of the polymeric carrier, respectively. The PGC-PTX polymer contains 58 wt% PTX (34 mol%) with an additional 25 wt% of free PTX within the NPs to achieve a loading of ≈83 wt%. HPLC confirmed PTX loading. The PGC-PTX + PTX NPs were then stored in solution at 4 °C or lyophilized at −20 °C for 49 days. The NP stability was determined via DLS measurements at days 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, and 49.

2.3. Cell culture

Human malignant pleural mesothelioma cells (MSTO-211H, ATCC), human late-stage metastatic pleural mesothelioma cells (H28, ATCC), human metastatic squamous cell carcinoma/mesothelioma cells (H226, ATCC), human lung-derived mesothelioma cells (H2452, ATCC), human lung fibroblasts (NHLF, Lonza), and MSTO-211H transfected with firefly luciferase gene (MSTO-211H-Luc; a generous gift from J. Rheinwald at Harvard Medical School, Boston) were cultured in RPMI 1640 media, containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin (100 mg/mL), and penicillin (100 units/mL). All cell lines were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Cell culture supplies were obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific Inc. unless specified.

2.4. In vitro cell viability

MSTO-211H tumor cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 2,000 cells/well in media. After 24 hours, media was removed and replaced with media containing PGC-PTX + PTX NP, unloaded-NPs, or PTX. Cells were incubated with treatments for 4 hours, treatments were removed, and cells were washed thrice with warm phosphate buffered saline (PBS) before addition of media without treatments. After further culturing for 3 days, cell viability was determined using the CellTiter 96® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega; Madison, WI). All viability assays were performed in triplicates, and the percent viability of treatment wells was calculated as absorbance relative to control wells receiving no treatments.

2.5. Cellular uptake of PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX via confocal-microscopy

MSTO 211-H and NHLF cells were gown on 12-well glass bottom plates (Celvis, P12–1.5H-N) at a density of 50,000 cells/well and grown for 48 hours. Cells were then treated with a 200 ng/mL dose of the PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs for 3 hours, washed with live-cell imaging solution (Invitrogen, A14291DJ), and incubated with 5 μg/mL WGA-488 (Invitrogen, W6748) for 10 min at 37°C. Following labeling of the cell membrane, the cells were then washed and incubated with 1 incubated with 1 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 for 5 minutes. Cells were washed again and then imaged immediately on an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope with a temperature control chamber at 37°C.

2.6. Cellular uptake of PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX via flow cytometry

MSTO-211H, H28, H2452, H226, and NHLF cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 300,000 cells/well and are allowed to adhere overnight. MSTO-211H cells were incubated for 2 hours with different inhibitors of the cellular uptake pathway (endocytosis inhibitor - brefeldin A; clatherin-mediated endocytosis inhibitor - chlorpromazine; microtubule inhibitor - colchicine; lysomotropic agent - chloroquine; macropinocytosis inhibitor - rottlerin), rinsed, and then incubated with the same PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs at a concentration of 400 ng/mL. After 3 hours (N=3/group), wells were rinsed 3x with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and cells were detached using 0.5 mL/well trypsin-EDTA (0.25%). Cells were collected using 2 mL media/well, pelleted via centrifugation at 1000 RPM for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was removed. Cells were subsequently fixed via resuspension in 3 mL 4% formaldehyde for 15 minutes, before being washed with 5 mL cold fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (0.1% sodium azide, 1% BSA in PBS), pelleted via centrifugation, and resuspended in 0.5 mL FACS buffer. The fluorescence of the cell population was evaluated using a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences; Franklin Lakes, NJ), with 10,000 events (single cells) recorded per sample. Data analysis was performed using the FlowJo software.

2.7. In vivo tumor models

Athymic mice (NU/J, 6–8 week old, female mice; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at the animal facility in the Dana Faber Cancer Institute, Boston and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Animal care and procedures were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (DFCI IACUC number: 07–027; MGH IACUC number: 2019N000085), in strict compliance with all federal and institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 106 MSTO-211H-Luc cells. For experiments requiring substantial tumor tissues including the in vivo localization study and the PTX biodistribution study, the tumors were allowed to grow in mice for 3 weeks before the treatments. For the survival study, the treatments were started 1 week after tumor inoculation, which represents a clinically relevant model of limited tumor burden following cytoreductive surgery.

2.8. In vivo biodistribution of PGC-PTX + PTX NPs

Three weeks after xenografting of tumor cells, animals were randomized and received either an intraperitoneal injection of 10% rhodamine B-labelled PGC-PTX + PTX NPs diluted to 300 μL with saline (n=4), the equivalent free rhodamine B in saline (n=3) or just saline (n=3). Animals were sacrificed 72 hours later, and high-resolution digital photographs were taken of the intraperitoneal space using a Nikon D40 camera under daylight lamp (focal length: 55 mm, automatic exposure, aperture: F5.6) and ultraviolet light (302 nm; camera focal length: 55 mm, exposure: 5 seconds, aperture: F5.6) from a Wood’s lamp. Rhodamine B is excited at both 302 and 254 nm UV light. The fluorescence is more intense with 302 nm excitation, and thus we used this excitation wavelength for the studies [57]. The tumor tissues were snap frozen in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. compound, and 5–6 μm thick frozen sections were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes and then stained with a mixture of DAPI (0.2 μg/mL) and WGA 488 (5 μg/mL) in HBSS for 10 mins. The tissues were mounted with ProLong™ gold antifade mountant (Invitrogen) overnight and imaged with a BZ-X800 fluorescence microscope with optical sectioning function (Keyence).

2.9. In vivo pharmacokinetics of PGC-PTX + PTX NPs

Three weeks following xenografting, NU/J mice received either intraperitoneal injections of PGC-PTX + PTX NPs (210 mg/kg total paclitaxel) (n=4), or free PTX in chromophore/ethanol (PTX-C/E 20 mg/kg) (n=4). The concentration for PTX-C/E was chosen as it is reported to be the MTD for IP administration [58]. Blood samples were collected from the facial vein in live animals. After euthanasia, 1 mL of cold PBS (Ca2+ and Mg2+ free) were injected into the peritoneal cavity, and the intraperitoneal lavage fluid was aspirated with a 25G needle slowly after abdominal massage. The fluid recovery rate is 80%−90% in all mice. Afterwards, all visible tumor was harvested, weighted, and stored at −20 °C. Tissues from intraperitoneal organs including liver, spleen, kidney, and a 5 cm long section of small intestine were harvested. PTX concentrations in liquid (plasma and lavage) and tissues were measured by Bioanalytical Systems Inc. (West Lafayette, IN) using proprietary protocols which involve HPLC followed by LC-MS. The detecting limits for liquid samples and tissue samples were 5 ng/mL and 0.5 ng/g, respectively.

2.10. Multiple-dose model treating established disease

NU/J mice received treatments started 7 days after 5 × 106 MSTO-211H-Luc cells injection. Four treatments were randomly assigned to the animals: 1) saline IP, weekly (n=13); 2) PTX-C/E 20 mg/kg IP weekly x 10 times or until euthanasia criteria were met (n=12); 3) PGC-PTX + PTX NPs IP, one dose on day 7 (n=13); 4) PGC-PTX + PTX NPs IP, 2x doses, on day 7 and day 35 (n=11). The euthanasia criteria included: 1) body weight loss more than 15%, or 2) clinical signs of tumor burden. Sequential bioluminescence images (BLI) were taken at 4 and 6 weeks after tumor inoculations from randomly pre-selected mice. “Empty” images (black squares) represent death of animal before repeat imaging at the 6 timepoint. Black triangles indicate images from previous published study [26].

2.11. Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard error unless specified in the text. All computations were performed using the Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA). All significance tests and P-values are two-sided with P < 0.05 as significant.

3. Results and discussion:

3.1. Characterization of ultra-high loaded polymeric nanoparticle system

One of the biggest challenges of polymeric nanoparticle drug delivery systems (NPs) is low agent loading efficiencies [56,59,60]. Inadequate loading necessitates large doses or multiple treatments to achieve therapeutic levels, which in turn raises concerns related to biocompatibility and safety. We overcame this key issue by conjugating the chemotherapeutic, in this case PTX, directly to the polymer backbone of poly(1,2-glycerol carbonate)-graft-succinic acid, followed by NP formation [55]. Poly(1,2-glycerol carbonate) (PGC) is an ideal hydrophobic polymer for PTX conjugation, as it is straightforward to synthesize in well-defined molecular weights, is biocompatible, is biodegradable with degradation products of glycerol and carbon dioxide, and is atom efficient in terms of the repeat unit (i.e., a low molecular weight for the repeat unit) [61]. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, succinic acid links PTX to the PGC backbone, providing a hydrolysable ester linkage for the release of PTX. Varying the degree of PTX conjugation on the polymer enables controlled NP drug loading as high as 70 wt% (traditional particles encapsulate ~10 wt% PTX), and sustain in vitro drug release for over 60 days [55]. Although a single PGC-PTX NP intraperitoneal injection is safe and initially efficacious, all animals eventually succumb to mesothelioma in our initial experiments using models of prevention of tumor establishment and established tumors. We hypothesized that the lack of an initial PTX burst from the NPs may allow some tumor cells to survive and that higher PTX levels may prevent eventual tumor escape [55]. Therefore, we encapsulated free PTX within PGC-PTX NPs to further increase the amount of administered drug, and to boost the initial bolus dose. These NPs showed promising results in an initial in vivo study [56]. Building off of these findings and to further evaluate in vivo NP performance, we synthesized PTX-PGC + PTX NPs with a total PTX loading of 83 wt% PTX (58 wt% conjugated and 25 wt% encapsulated). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) data shows sub-100 nm diameter NPs with a negative zeta potential of −43 mV, and a PDI of 0.1 (Figure S2a–c). Scanning electron microscopy reveals spherical, monodisperse particles as well (SEM; Fig. 1b). The PGC-PTX + PTX NPs are stable both in solution at 4 °C and lyophilized at −20 °C over the course of 49 days (Figure S2d).

3.2. Determination of cellular uptake mechanism

Next, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of the PTX-PGC + PTX NPs against four mesothelioma cell lines, specifically chosen to demonstrate efficacy against a range of tumor severity and location, as H28 is derived from a patient with stage 4 mesothelioma; MSTO-211H is a biphasic mesothelioma; H226 is both squamous cell carcinoma/mesothelioma; and H2452 is a pleural mesothelioma. The PTX-PGC + PTX NPs are highly cytotoxic with IC50 values of 67.2 ng/mL, 32.1 ng/mL, 26.3 ng/mL, and 14.1 ng/mL, respectively (Fig. 1c). These IC50 values are greater than that of free PTX (1–10 ng/mL), which is likely due to the slow release of encapsulated PTX from the NPs. Notably, when incubated with a normal fibroblast cell line (NHLF), the IC50 increases to 98.8 ng/mL, indicating a reduced cytotoxic effect. To further investigate this difference in NP cytotoxicity for tumor vs normal cell lines, both MSTO-211H and NHLF cells were incubated for 3 hours with fluorescently labeled PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs, stained with wheat germ agglutinin Oregon Green 488 and Hoechst 33342 for cell membrane and nucleus staining, respectively, and then underwent confocal imaging (Fig. 2a and 2b, respectively). Representative confocal images show greater NP uptake in the mesothelial tumor cells compared to the normal fibroblast cells. To quantify and better understand the NP uptake, we performed flow cytometry experiments with the PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs and with several small-molecule inhibitors to gain insight into the mechanism of NP uptake. Specifically, MSTO-211H cells were incubated for 2 hours with different inhibitors of the cellular uptake pathway (endocytosis inhibitor - brefeldin A; clatherin-mediated endocytosis inhibitor - chlorpromazine; microtubule inhibitor - colchicine; lysomotropic agent - chloroquine; macropinocytosis inhibitor - rottlerin) prior to addition of the NPs. After 3 hours of incubation with the PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs (400 ng/mL), the cells were prepped for flow cytometry similarly to previously published methods [62]. Gating for cellular viability and rhodamine B signal are illustrated in Figure S3. The significant decrease in fluorescence intensity for the rottlerin group indicates that macropinocytosis is downregulated, as rottlerin is a polycyclic aromatic compound that inhibits kinases associated with macropinocytosis, such as protein kinase C-delta (Fig. 2c) [63]. Treatment of the other three mesothelioma cell lines with rottlerin leads to similar relative reduction in fluorescence intensity, suggesting that macropinocytosis is a mechanism of PGC-PTX + PTX NP uptake in all of these cell lines (Fig. 2d). Macropinocytosis also plays a role in NP uptake in normal fibroblast cells, as treatment with rottlerin also decreases NP uptake (Fig. 2e). However, the mean rhodamine B intensity in the healthy fibroblasts is almost half of those in the mesothelioma tumor cells, consistent with the reduced overall NP uptake in the healthy cell line.

Fig 2.

Determination of the cellular uptake pathway for the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs. a) Confocal imaging of PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs in MSTO-211H cells, stained with wheat germ agglutinin Oregon Green 488 and Hoechst 33342 for cell membrane and nucleus staining, respectively. Scale bar = 20 μm. b) Confocal imaging of PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs in NHLF cells. c) FACS analysis of PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NP cellular uptake in MSTO-211H cells demonstrate use of macropinocytosis with rottlerin mediated inhibition. d) FACS analysis of cellular uptake with and without treatment of rottlerin in various mesothelioma cell lines including H28, H2452, and H226. e) Preferential uptake of NPs in MSTO-211H compared to their healthy NHLF fibroblasts determined via FACS. *P < 0.05, **P< 0.01

3.3. Visualization of PGC-PTX +PTX NP accumulation in vivo

Cellular uptake in 2D in vitro models does not necessarily correlate with in vivo tumor localization and uptake. To qualitatively assess the tumor specificity of the NPs, we intraperitoneally injected either PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs, free rhodamine B dissolved in PBS, or saline alone three weeks after 5 × 106 MSTO-211H-luc cell intraperitoneal inoculation (Fig. 3a). Upon animal euthanasia 72 hours later, higher fluorescence signals are present in tumors than in other abdominal organs including the liver, spleen, kidneys, and intestines under UV light excitation (Fig. 3b). No intra-tumoral fluorescence signal is seen in either the saline or the free rhodamine B control groups, consistent with the short half-life of rhodamine B (initial t1/2 IV = 15 min, terminal t1/2 IV = 4.7 hrs) [64]. Fluorescence microscopy of the cross-section of collected frozen tumor tissues reveals that the PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs accumulate at the outer rim of the tumor and in the connective tissues between microscopic tumor nodules (Fig. 3c and Figure S4).

Fig. 3.

Higher affinity of PGC-PTX+PTX NPs to tumor tissues than healthy tissues and evidence of penetration in tumors. a) Timeline of the in vivo experiment. b) Visible light and UV light (302 nm) imaging after treatment with PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs (n=4), free rhodamine B (n=3), or saline (n=3). Co-localization of NPs (red under UV excitation) is demonstrated in tumor tissues (yellow circles). c) Merged images showing PGC-PTX(Rho) + PTX NPs (red) penetrated in the tumor tissues; blue color represents nuclei with DAPI staining, and green color represents cell membrane with WGA-488 staining (scale bar = 200 μm).

3.4. Assessment of pharmacokinetics and safety

NPs accumulate after IP injection primarily in the regions of peritoneal tumor, which is critical for effective local delivery while decreasing potential off-target toxicities. However, differences in tumor uptake does not prove PTX concentration differences between the disease site and the surrounding healthy tissue, which is critical to assessing both efficacy and morbidity of PGC-PTX + PTX potential as a potential targeted local delivery system. Thus, we assessed the pharmacokinetics of PTX released from the NPs over an extended duration via high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of tissues, peritoneal lavage, and plasma samples. Tumor bearing mice were established with the intraperitoneal inoculation of 5 × 106 MSTO-211H-luc cells three weeks prior to receiving either a single IP administration of the PTX-PGC + PTX NPs (210 mg/kg) or the highest tolerated single dose of PTX-C/E (20 mg/kg) (Fig. 4a). At each timepoints (6 hours, 1 week, and 2 weeks), a group of animals (n = 4) were euthanized, and the plasma, peritoneal lavage, intraperitoneal tumors, and other vital organs were harvested and evaluated for paclitaxel concentration. It is important to note that the assays can detect only the released paclitaxel, not the drug still covalently bound to the polymer, and thus drug levels represent the currently available “active” drug.

Fig. 4.

Paclitaxel concentration kinetics after IP administration with PGC-PTX + PTX NPs (n=4) or PTX-C/E (n=4). a) Timeline of late-stage established tumor model. b) Peritoneal tumor weights at 6 hours, 1 week, and 2 weeks after treatment with PGC-PTX+PTX NPs or PTX-C/E. c) Released paclitaxel concentration in tumor, peritoneal lavage, plasma and other vital organs after single bolus intraperitoneal injection of either PGC-PTX+PTX NPs (PTX 210 mg/kg) or PTX-C/E (20 mg/kg) given 3 weeks after inoculation with MSTO-211H-luc cells in NU/J mice. * P < 0.05. Additional H&E staining of liver, spleen, kidney, and intestine samples after 6-month survival study of established MSTO-211H-luc tumor bearing model of treatment with either the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs administered IP twice, or PTX-C/E administered IP 10x weekly. Scale bar = 50 μm.

The paclitaxel concentration in the tumor is 10x, 62x, and >1000x greater at the 6-hour, 1-week, and 2-week timepoints, respectively, in the PGC-PTX + PTX NP treated mice compared to the IP PTX-C/E group. Consistent with the PTX tumor concentrations, IP administration of PTX-C/E is effective for a short duration, but after only two weeks the tumor weight starts to increase. This is in contrast to in the PGC-PTX + PTX NP treatment group where the tumor weight decreases (Fig. 4b). In fact, the tumor weight is three-times lower in mice treated with PGC-PTX + PTX NPs compared to PTX-C/E, highlighting the importance and necessity for prolonged PTX release in tumor control.

In contrast to the differences in the PTX tumor concentrations (Fig. 4c), the plasma PTX concentrations appear more similar between the PGC-PTX + PTX NP and PTX-C/E treatment groups. The ratios of the PTX concentrations (PGC-PTX + PTX NP to PTX-C/E) after 6 hours is under 2x, whereas the 1- and 2-week timepoints are all under the level of detection (5 ng/mL), except for the 1-week NP treatment group, which is just above this limit (11.1 ng/mL). These results demonstrate that the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs can deliver significantly greater concentrations of PTX to the tumor site while limiting systemic delivery, potentially limiting off-target toxicities. As expected, the PTX levels in liver, spleen, kidney, and intestine are similar at 6 hours given the burst release of the freely-encapsulated PTX from the NPs akin to a bolus dose of PTX give IP. However, at the 1 and 2-week timepoints, the tissue levels of PTX-C/E plummet as the free drug is cleared by the liver, whereas the PTX tissue levels from the NP-treated mice remain similar or slowly decline. Therefore, at 6 hours, the ratio of the PTX concentrations (PGC-PTX + PTX NP to PTX-C/E) is 5.7x; yet as the PTX-C/E bolus is rapidly cleared, this ratio significantly increases to over 5000x for the 1- and 2-week timepoints. Over the course of 6 hours to 2 weeks, the PTX concentrations decrease, although the reduction is the greatest for the PTX-CE treatment group (Table S1). Comparative data on safe paclitaxel tissue levels for individual organs after prolonged exposure are lacking, since previous pharmacokinetic studies have focused on shorter duration after bolus treatment due to the fast metabolism and clearance of free paclitaxel (t1/2 IV = 4.7 ± 3.3 hrs) [11,65,66]. Nonetheless, no morbidity or mortality was noted in the NP-treated cohort over the 6-month follow-up, tissues collected at the 6-month end point of the in vivo survival study (see below) show no adverse effects via histopathologic evaluation, and the organs (e.g., liver, spleen, kidney, and intestine) appear microscopically similar amongst the treatments. Furthermore, mice body weights remain stable and the WBC counts are comparable between mice treated with PTX-PGC+PTX NP IP and with PTX-C/E on day 10, the day when the nadir of the WBC occurs in mice (Figure S5). Further there is no statistical difference in body weights at the 5- and 9-week timepoints, which is 4 weeks after the first treatment and 4 weeks after the second dose of the PGC-PTX + PTX NP x2 group, respectively. Histopathologic examination of major organs shows no overt signs of toxicity 6 months after one or two treatments of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs (Figure S6).

3.5. Evaluation of in vivo anti-cancer efficacy

Finally, we evaluated PGC-PTX + PTX NPs efficacy in vivo using a human peritoneal mesothelioma murine model. Seven days after MSTO-211H-luc injection and establishment of tumor, mice were randomly assigned to receive the following treatments: 1) single IP injection of PGC-PTX+PTX NPs (total paclitaxel dose of 210 mg/kg); 2) two IP injections one on day 7 and a second on day 35 of PGC-PTX+PTX NPs (total paclitaxel dose of 420 mg/kg); 3) IP PTX-C/E 20 mg/kg weekly for 10 doses or until tumor burden met pre-defined end point for euthanasia (total paclitaxel dose of 200 mg/kg or less); or 4) weekly saline IP injections (Fig. 5a). We chose to deliver the second PGC-PTX + PTX NP dose on day 35. We hypothesized that the second injection would boost the depleted drug levels in the tumor site, therefore maintaining the therapeutic levels of PTX and increasing the median survival.

Fig. 5.

Overall survival in established MSTO-211H tumor bearing model. a) Timeline of the survival study in an established intraperitoneal mesothelioma model. Mice were randomly assigned to 1) saline IP control on day 7 after inoculation with MSTO-211H-luc cells in NU/J mice (n=13); 2) PTX-C/E 20mg/kg IP weekly up to 10 weeks starting on day 7 after tumor inoculation (maximum dosing 200 mg/kg) (n=12); 3) PGC-PTX+PTX NPs (total PTX dose 210 mg/kg, IP) on day 7 after inoculation (n=13); 4) PGC-PTX+PTX NPs IP on day 7 and day 35 after inoculation (total PTX dose 420 mg/kg, IP) (n=11). b) Sequential bioluminescence imaging (BLI) at 4 and 6 weeks from selected mice. Each column is the same mouse, and the “empty” images represent death of animal before the 6 week timepoint. Black triangles indicate images from previous published study [26]. All images utilized the same intensity scale. c) Summary of luminescent intensities of images in panel b. *: P < 0.05 Saline vs PGC-PTX+PTX NPs x2 and PGC-PTX+PTX NPs x1. d) Overall survival. †: P < 0.05 PGC-PTX+PTX NPs x2 vs PGC-PTX+PTX NPs x1. MST: Median survival time.

Bioluminescence imaging reveals low tumor signals at both 4 and 6 weeks in the mice treated with a single dose of PGC-PTX + PTX NPs with the exception of one mouse. Conversely, large tumor volumes are seen in all but one mouse after 6 weeks of PTX-C/E weekly treatments. Only one mouse survived past 6 weeks with saline treatments with considerable tumor signals (Fig. 5b). The impact of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs are mirrored in the overall survival. The clinical PTX treatment control, i.e. 20 mg/kg PTX-C/E administered weekly, prolongs survival by only 18 days compared to the saline control (MST 53 days vs. 35 days, P < 0.0001). In contrast, a single dose of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs extends survival by 45 days (MST 81 days vs. 35 days, P < 0.0001), and the addition of a second dose of the PGC-PTX+PTX NPs significantly improves survival by 87 days compared to the saline control (MST 122 days vs. 35 days, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5c).

Previous work by our group demonstrated the optimization and significant improvement of this novel nanoparticle formulation. In a similar established intraperitoneal mesothelioma model, eNPs significantly reduce tumor volume and extended the median survival roughly 2-fold compared to a bolus PTX-C/E injection (54 vs 26.5 days, respectively) [53]. Similar success was shown with the PGC-PTX NPs, as survival in an established intraperitoneal mesothelioma model was roughly 1.5-fold compared to the untreated control (55 vs 37 days, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in survival between the PGC-PTX NPs administered once, and weekly injections of PTX-C/E (55 and 65 days, respectively) [55]. These nanoparticle formulations suffer from opposite pharmacokinetics. The eNPs exhibit a burst release in acidic conditions, releasing the majority of paclitaxel quickly. The PGC-PTX NPs show sustained release for over 70 days, however the initial release is very slow, less then 5% over the first 5 days, and is likely below the therapeutic level [55]. The PGC-PTX + PTX NPs take advantage of both these formulation designs, as the freely encapsulated PTX is released quickly, ~25% over the first 5 days, while the chemically conjugated PTX is released over the span of several weeks. Both NPs demonstrate first order release kinetics during the first two weeks, however the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs exhibit a release rate roughly 6x greater than the previous PGC-PTX NP iteration [56]. This is likely the reason the survival for the PGC-PTX + PTX NP treated mice is roughly 4-fold longer than the untreated control after only two administrations a month apart.

Despite eventual recurrence, these results support our hypothesis and demonstrate the clinical utility of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs. Increasing treatment efficacy by prolonging the effective drug concentration at disease sites while reducing the number of required drug administrations and systemic side effects are a critical advance for successful clinical translation. Recurrence in this model is likely due to a small number of cells that survive the PTX treatments, and not PTX resistance. This is evident by the increase in survival with a second treatment, as resistance cells would likely not be impacted by an additional treatment. Future work would include additional administrations of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs to extend the duration of PTX release and further improve overall survival, as we hypothesize the levels of PTX in the tumor after 90 days is below the therapeutic level. Additionally, a dose escalation study with the NPs would exemplify their ability to safely delivery ultra-high concentrations of paclitaxel, and potentially further improve their therapeutic effect.

4. Conclusion

Local intraperitoneal treatments can improve clinical efficacy in diseases such as malignant peritoneal mesothelioma; yet, the long-term efficacy remains limited due to the requirement for multi-dose infusions over several months, high incidence of infection and wound complications, and ultimately recurrent disease. Nanoparticle formulations offer the potential to deliver agents specifically to the tumor with optimized drug release profiles and pharmacokinetics, but are often limited by low drug loading efficiency. By conjugating PTX directly to the backbone of our PGC polymer, we engineered an ultra-high loaded, sub-100nm PGC-PTX + PTX NP formulation, which provides early and prolonged PTX delivery. The NPs are preferentially taken up by mesothelioma tumor cells in vitro, mechanistically via macropinocytosis, compared to healthy control cells. The NPs are cytotoxic against four mesothelioma cell lines of different severity and origins. Upon IP administration, the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs localize to the tumors within 72 hours, with minimal accumulation in other abdominal tissues. PTX concentrations are greater in the tumor after PGC-PTX + PTX NP administration, and significantly higher when compared to clinically relevant PTX-C/E control at six hours, one week, and two week time points. More importantly, these drug tumor levels are sustained at a high level for a minimum of several weeks. In a murine model of established peritoneal mesothelioma, a single dose of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs improves survival compared to maximally tolerated doses of weekly PTX-C/E administered for 10 weeks. The addition of a second dose of the NPs, one month after the initial treatment, further improves the median overall survival, although we acknowledge the eventual progression of disease and mortality. Given the importance of surgical cytoreduction in the clinical treatment of this disease, future studies will examine use of multi-dose PGC-PTX+PTX NPs in a surgical resection model for improved survival and assessment of peri-operative morbidity.

While prolonged multi-dose local chemotherapeutic regimens for the treatment of peritoneal mesothelioma have shown benefit, treatment-related morbidities and clinically complex multiphase regimens makes clinical standardization, treatment completion, and patient tolerance quite challenging, thereby limiting overall success. One injection of the PGC-PTX + PTX NPs safely delivers prolonged high PTX levels at the site of tumor which far exceeds the dose that can currently be administered systemically (greater than the maximally tolerated IV or IP dose). It achieves the milestone of maintaining therapeutic drug levels within the tumor for weeks while reducing systemic absorption and limiting the off-target toxicities. The success of these nanoparticles against peritoneal mesothelioma highlights the potentials for clinical translation of these tunable technologies due to their tumor localization, ultra-high drug loading, prolonged and substantial drug tissue concentrations, and low off-target delivery and side effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from the National Cancer Institute (grant numbers R01 CA232056 and R01CA227433), and the National Institute of Health T32 Grant entitled Translational Research in Biomaterials (NIH T32EB006359, AM and RCS), and the Distinguished Professor of Translational Research Chair at Boston University (MWG). Research reported in this publication was supported by the Boston University Micro and Nano Imaging Facility and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health of the National Institutes of Health under award Number S10OD024993. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests. We have NIH support for this work. A patent application has been submitted and is owned by BU. The patent and technology are available for licensing.

Data Availability.

The raw data required to reproduce these findings are available from the authors upon request.

References

- [1].Greenbaum A, Alexander HR, Peritoneal mesothelioma, Transl Lung Cancer Res. 9 (2020) 120–132. 10.21037/tlcr.2019.12.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Scherpereel A, Wallyn F, Albelda SM, Munck C, Review Novel therapies for malignant pleural mesothelioma, Lancet Oncol. 19 (2018) e161–e172. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Carbone M, Adusumilli PS, Alexander HR, Baas P, Bardelli F, Bononi A, Bueno R, Felley-bosco E, Galateau-salle F, Jablons D, Mansfield AS, Minaai M, De Perrot M, Pesavento P, Rusch V, Severson DT, Taioli E, Tsao A, Woodard G, Yang H, Zauderer MG, Pass HI, Mesothelioma : Scientific Clues for Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy, (2019) 402–429. 10.3322/caac.21572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Salo S, Ilonen I, Laaksonen S, Myllarniemi M, Salo J, Rantanen T, Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma : Treatment Options and Survival, Anticancer Res. 39 (2019) 839–845. 10.21873/anticanres.13183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bijelic L, Darcy K, Stodghill J, Tian C, Cannon T, Predictors and Outcomes of Surgery in Peritoneal Mesothelioma: an Analysis of 2000 Patients from the National Cancer Database, Ann. Surg. Oncol. 27 (2020) 2974–2982. 10.1245/s10434-019-08138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kepenekian V, Elias D, Passot G, Mery E, Goere D, Delroeux D, Quenet F, Ferron G, Pezet D, Guilloit JM, Meeus P, Pocard M, Bereder JM, Abboud K, Arvieux C, Brigand C, Marchal F, Classe JM, Lorimier G, De Chaisemartin C, Guyon F, Mariani P, Ortega-Deballon P, Isaac S, Maurice C, Gilly FN, Glehen O, Averous G, Bereder JM, Bibeau F, Bouzard D, Chevallier A, Croce S, Dartigues P, Durand-Fontanier S, Gouthi L, Heyd B, Kaci R, Kianmanesh R, Laverrière MH, Leblanc E, Lelong B, Leroux A, Loi V, Mariette C, Meeus P, Msika S, Pezet D, Peyrat P, Pirro N, Paineau J, Poizat F, Porcheron J, Quenet F, Rat P, Regimbeau JM, Thibaudeau E, Tuech JJ, Valmary-Degano S, Verriele V, Zerbib P, Zinzindohoue F, Diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: Evaluation of systemic chemotherapy with comprehensive treatment through the RENAPE Database: Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study, Eur. J. Cancer. 65 (2016) 69–79. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sugarbaker PH, Update on the management of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma, 7 (2018) 599–608. 10.21037/tlcr.2018.08.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Levý M, Boublíková L, Büchler T, Šimša J, Treatment of Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma, Clin. Oncol. 32 (2019) 333–337. 10.14735/amko2019333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sugarbaker DJ, Flores RM, Jaklitsch MT, Richards WG, Strauss GM, Corson JM, De Camp J, Swanson SJ, Bueno R, Lukanich JM, Baldini EH, Mentzer SJ, Kaiser LR, Patterson GA, Faber LP, Resection margins, extrapleural nodal status, and cell type determine postoperative long-term survival in trimodality therapy of malignant pleural mesothelioma: Results in 183 patients, J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 117 (1999) 54–65. 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yan TD, Deraco M, Baratti D, Kusamura S, Elias D, Glehen O, Gilly FN, Levine EA, Shen P, Mohamed F, Moran BJ, Morris DL, Chua TC, Piso P, Sugarbaker PH, Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: Multi-institutional experience, J. Clin. Oncol. 27 (2009) 6237–6242. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kuhn JG, Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel, Ann. Pharmacother. 28 (1994). 10.1177/10600280940280s504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Van Zomeren DM, Buijs D, Ouwens L, Nooter K, Stoter G, Sparreboom A, Influence of cremophor EL on the bioavailability of intraperitoneal paclitaxel, Clin. Cancer Res. 8 (2002) 1237–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sugarbaker PH, Chang D, Long-term regional chemotherapy for patients with epithelial malignant peritoneal mesothelioma results in improved survival, Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 43 (2017) 1228–1235. 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sugarbaker PH, Stuart OA, Unusually favorable outcome of 6 consecutive patients with diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma treated with repeated doses of intraperitoneal paclitaxel. A case series, Surg. Oncol. 33 (2020) 96–99. 10.1016/j.suronc.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sugarbaker PH, Normothermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy long term (NIPEC-LT) in the management of peritoneal surface malignancy, an overview, Pleura and Peritoneum. 2 (2017) 85–93. 10.1515/pp-2017-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sugarbaker PH, Intraperitoneal delivery of chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of peritoneal metastases: current challenges and how to overcome them, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 16 (2019) 1393–1401. 10.1080/17425247.2019.1693997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Alexander HR, Bartlett DL, Pingpank JF, Libutti SK, Treatment factors associated with long-term survival after cytoreductive surgery and regional chemotherapy for patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma, Surgery. 153 (2010) 779–786. 10.1016/j.surg.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A, Cremophor EL: The drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation, Eur. J. Cancer. 37 (2001) 1590–1598. 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sparreboom A, Van Tellingen O, Nooijen WJ, Beijnen JH, Nonlinear Pharmacokinetics of Paclitaxel in Mice Results from the Pharmaceutical Vehicle Cremophor EL, Cancer Rese. 56 (1996) 2112–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Min Y, Caster JM, Eblan MJ, Wang AZ, Clinical Translation of Nanomedicine, Chem. Rev. 115 (2015) 11147–11190. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wolinsky J, Colson Y, Grinstaff M, Local Drug Delivery Strategies for Cancer Treatment: Gels, Nanoparticles, Polymeric Films, Rods, and Wafers, J. Control. Release. 159 (2012) 1–7. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Petros RA, Desimone JM, Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9 (2010) 615–627. 10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mitchell MJ, Billingsley MM, Haley RM, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA, Langer R, Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20 (2021) 101–124. 10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Anselmo AC, Mitragotri S, Nanoparticles in the clinic: An update, Bioeng. Transl. Med. 4 (2019) 1–16. 10.1002/btm2.10143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Donahue ND, Acar H, Wilhelm S, Concepts of nanoparticle cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, and kinetics in nanomedicine, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 143 (2019) 68–96. 10.1016/j.addr.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang Y, Chan HF, Leong KW, Advanced materials and processing for drug delivery: The past and the future, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 65 (2013) 104–120. 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bertrand N, Wu J, Xu X, Kamaly N, Farokhzad OC, Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 66 (2014) 2–25. 10.1016/j.addr.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang L, Jing D, Jiang N, Rojalin T, Baehr CM, Zhang D, Xiao W, Wu Y, Cong Z, Li JJ, Li Y, Wang L, Lam KS, Transformable peptide nanoparticles arrest HER2 signalling and cause cancer cell death in vivo, Nat. Nanotechnol. 15 (2020) 145–153. 10.1038/s41565-019-0626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Xiao K, Luo J, Fowler WL, Li Y, Lee JS, Xing L, Cheng RH, Wang L, Lam KS, A self-assembling nanoparticle for paclitaxel delivery in ovarian cancer, Biomaterials. 30 (2009) 6006–6016. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kumari A, Yadav SK, Yadav SC, Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles based drug delivery systems, Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 75 (2010) 1–18. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kratz F, Albumin as a drug carrier : Design of prodrugs, drug conjugates and nanoparticles, J. Control. Release. 132 (2008) 171–183. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].De Vita F, Ventriglia J, Febbraro A, Laterza MM, Fabozzi A, Savastano B, Petrillo A, Diana A, Giordano G, Troiani T, Conzo G, Galizia G, Ciardiello F, Orditura M, NAB-paclitaxel and gemcitabine in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC): From clinical trials to clinical practice, BMC Cancer. 16 (2016) 1–8. 10.1186/s12885-016-2671-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schettini F, Giuliano M, De Placido S, Arpino G, Nab-paclitaxel for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer: Rationale, clinical data and future perspectives, Cancer Treat. Rev. 50 (2016) 129–141. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Adrianzen Herrera D, Ashai N, Perez-Soler R, Cheng H, Nanoparticle albumin bound-paclitaxel for treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: an evaluation of the clinical evidence, Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 20 (2019) 95–102. 10.1080/14656566.2018.1546290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Miele E, Spinelli GP, Miele E, Tomao F, Tomao S, Albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel (Abraxane® ABI-007) in the treatment of breast cancer, Int. J. Nanomedicine. 4 (2009) 99–105. 10.2147/ijn.s3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yardley DA, nab -Paclitaxel mechanisms of action and delivery, J. Control. Release. 170 (2013) 365–372. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Oneto JMM, Khan I, Seebald L, Royzen M, In vivo bioorthogonal chemistry enables local hydrogel and systemic pro-drug to treat soft tissue sarcoma, ACS Cent. Sci. 2 (2016) 476–482. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Suh MS, Patil SM, Kozak D, Pang E, Choi S, Jiang X, Rodriguez JD, Keire DA, Chen K, An NMR Protocol for In Vitro Paclitaxel Release from an Albumin-Bound Nanoparticle Formulation, AAPS PharmSciTech. 21 (2020) 1–8. 10.1208/s12249-020-01669-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gardner ER, Dahut WL, Scripture CD, Jones J, Aragon-Ching JB, Desai N, Hawkins MJ, Sparreboom A, Figg WD, Randomized crossover pharmacokinetic study of solvent-based paclitaxel and nab-paclitaxel, Clin. Cancer Res. 14 (2008) 4200–4205. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gao Y, Nai J, Yang Z, Zhang J, Ma S, Zhao Y, Li H, Li J, Yang Y, Yang M, Wang Y, Gong W, Yu F, Gao C, Li Z, Mei X, A novel preparative method for nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel with high drug loading and its evaluation both in vitro and in vivo, PLoS One. 16 (2021) 1–25. 10.1371/journal.pone.0250670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Nowacki M, Peterson M, Kloskowski T, McCabe E, Guiral DC, Polom K, Pietkun K, Zegarska B, Pokrywczynska M, Drewa T, Roviello F, Medina EA, Habib SL, Zegarski W, Nanoparticle as a novel tool in hyperthermic intraperitoneal and pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotheprapy to treat patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, Oncotarget. 8 (2017) 78208–78224. 10.18632/oncotarget.20596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sugarbaker PH, Stuart OA, Pharmacokinetics of the intraperitoneal nanoparticle pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with peritoneal metastases, Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 47 (2021) 108–114. 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Simón-Gracia L, Hunt H, Scodeller PD, Gaitzsch J, Braun GB, Willmore AMA, Ruoslahti E, Battaglia G, Teesalu T, Paclitaxel-loaded polymersomes for enhanced intraperitoneal chemotherapy, Mol. Cancer Ther. 15 (2016) 670–679. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0713-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Xiao K, Luo J, Fowler W, Li Y, Lee J, Wang L, Lam KS, A self-assembling nanoparticle for paclitaxel delivery in ovarian cancer, Biomaterials. 30 (2009) 6006–6016. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.015.A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhai J, Luwor RB, Ahmed N, Escalona R, Tan FH, Fong C, Ratcliffe J, Scoble JA, Drummond CJ, Tran N, Paclitaxel-Loaded Self-Assembled Lipid Nanoparticles as Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Aggressive Ovarian Cancer, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 10 (2018) 25174–25185. 10.1021/acsami.8b08125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lei H, Hofferberth SC, Liu R, Colby A, Tevis KM, Catalano P, Grinstaff MW, Colson YL, Paclitaxel-loaded expansile nanoparticles enhance chemotherapeutic drug delivery in mesothelioma 3-dimensional multicellular spheroids, J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 149 (2015) 1417–1425.e1. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Colson YL, Liu R, Southard EB, Schulz MD, Wade JE, Griset AP, Zubris KAV, Padera RF, Grinstaff MW, The performance of expansile nanoparticles in a murine model of peritoneal carcinomatosis, Biomaterials. 32 (2011) 832–840. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Schulz MD, Zubris KAV, Wade JE, Padera RF, Xu X, Grinstaff MW, Colson YL, Paclitaxel-loaded expansile nanoparticles in a multimodal treatment model of malignant mesothelioma, Ann. Thorac. Surg. 92 (2011) 2007–2014. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Liu R, Khullar OV, Griset AP, Wade JE, Zubris KAV, Grinstaff MW, Colson YL, Paclitaxel-loaded expansile nanoparticles delay local recurrence in a heterotopic murine non-small cell lung cancer model, Ann. Thorac. Surg. 91 (2011) 1077–1084. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chu NQ, Liu R, Colby A, de Forcrand C, Padera RF, Grinstaff MW, Colson YL, Paclitaxel-loaded expansile nanoparticles improve survival following cytoreductive surgery in pleural mesothelioma xenografts, J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 160 (2020) e159–e168. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.12.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Griset AP, Walpole J, Liu R, Gaffey A, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW, Expansile Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and in Vivo Efficacy of an Acid-Responsive Polymeric Drug Delivery System, Jacs. 131 (2009) 2469–2471. https://doi.org/papers://2F94A527-0474-4007-B03B-3832ED902E90/Paper/p2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Liu R, Colby AH, Gilmore D, Schulz M, Zeng J, Padera RF, Shirihai O, Grinstaff MW, Colson YL, Nanoparticle tumor localization, disruption of autophagosomal trafficking, and prolonged drug delivery improve survival in peritoneal mesothelioma, Biomaterials. 102 (2016) 175–186. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Colson YL, Liu R, Southard EB, Schulz MD, Wade JE, Griset AP, Ann K, Zubris V, Padera RF, Grinstaff MW, The performance of expansile nanoparticles in a murine model of peritoneal carcinomatosis, Biomaterials. 32 (2011) 832–840. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Shen S, Wu Y, Liu Y, Wu D, High drug-loading nanomedicines: Progress, current status, and prospects, Int. J. Nanomedicine. 12 (2017) 4085–4109. 10.2147/IJN.S132780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ekladious I, Liu R, Zhang H, Foil D, Todd D, Graf T, Padera R, Oberlies N, Colson Y, Grinstaff MW, Synthesis of poly(1,2-glycerol carbonate)-paclitaxel conjugates and their utility as a single high-dose replacement for multi-dose treatment regimens in peritoneal cancer, Chem. Sci. (2017) 8443–8450. 10.1039/C7SC03501B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ekladious I, Liu R, Varongchayakul N, Mejia Cruz LA, Todd DA, Zhang H, Oberlies NH, Padera RF, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW, Reinforcement of polymeric nanoassemblies for ultra-high drug loadings, modulation of stiffness and release kinetics, and sustained therapeutic efficacy, Nanoscale. 10 (2018) 8360–8366. 10.1039/c8nr01978a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bartasun P, Cieśliński H, Bujacz A, Wierzbicka-Woś A, Kur J, A Study on the Interaction of Rhodamine B with Methylthioadenosine Phosphorylase Protein Sourced from an Antarctic Soil Metagenomic Library, PLoS One. 8 (2013) 1–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Zhang X, Burt HM, Mangold G, Dexter D, Von Hoff D, Mayer L, Hunter WL, Anti-tumor efficacy and biodistribution of intravenous polymeric micellar paclitaxel, Anticancer. Drugs. 8 (1997) 696–701. 10.1097/00001813-199708000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ekladious I, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW, Polymer–drug conjugate therapeutics: advances, insights and prospects, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18 (2019) 273–294. 10.1038/s41573-018-0005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].De Clercq K, Xie F, De Wever O, Descamps B, Hoorens A, Vermeulen A, Ceelen W, Vervaet C, Preclinical evaluation of local prolonged release of paclitaxel from gelatin microspheres for the prevention of recurrence of peritoneal carcinomatosis in advanced ovarian cancer, Sci. Rep. 9 (2019) 1–19. 10.1038/s41598-019-51419-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhang H, Grinstaff MW, Synthesis of atactic and isotactic poly(1,2-glycerol carbonate)s: Degradable polymers for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 6806–6809. 10.1021/ja402558m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Conde J, Oliva N, Atilano M, Song HS, Artzi N, Self-assembled RNA-triple-helix hydrogel scaffold for microRNA modulation in the tumour microenvironment, Nat. Mater. 15 (2016) 353–363. 10.1038/nmat4497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Sarkar K, Kruhlak MJ, Erlandsen SL, Shaw S, Selective inhibition by rottlerin of macropinocytosis in monocyte-derived dendritic cells, Immunology. 116 (2005) 513–524. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sweatman TW, Seshadri R, Israel M, Metabolism and elimination of rhodamine 123 in the rat, Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 27 (1990) 205–210. 10.1007/BF00685714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Cabanes A, Briggs KE, Gokhale PC, Treat JA, Rahman A, Comparative in vivo studies with paclitaxel and liposome-encapsulated paclitaxel, Int. J. Oncol. 12 (1998) 1035–1040. 10.3892/ijo.12.5.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Yang T, De Cui F, Choi MK, Cho JW, Chung SJ, Shim CK, Kim DD, Enhanced solubility and stability of PEGylated liposomal paclitaxel: In vitro and in vivo evaluation, Int. J. Pharm. 338 (2007) 317–326. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data required to reproduce these findings are available from the authors upon request.