Abstract

Background:

Today's health systems require the collaboration of diverse staff such as physicians, nurses, social workers, and other healthcare professionals. In addition to professional competencies, they also need to acquire interprofessional competencies. Effective interprofessional collaboration among healthcare professionals is one of the solutions that can promote the effectiveness of the health system using existing resources.

Materials and methods:

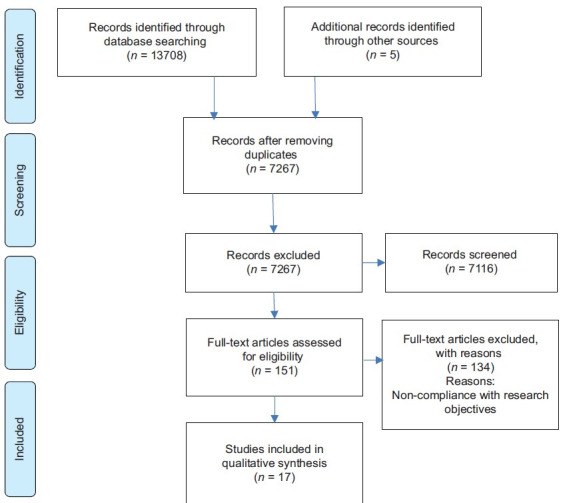

A systematic review was conducted in 2021 according to the PRISMA and through searching Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, ProQuest, Science Direct, Emerald, Springer Link, Google Scholar, SID, and Magiran databases. The official websites of WHO, United Nations, and World Bank were also searched. The time frame for the research was from 2010 to 2020, and included both the English and Persian languages. Out of 7267 initially retrieved articles, 17 articles finally met the quality evaluation criteria and were analyzed through qualitative content analysis. Then their full texts were retrieved and analyzed in MAXQDA software, and final results were categorized.

Results:

Competencies have been explored in various areas of health care, especially in the clinical field. The competencies introduced were extracted and categorized into six domains of “patient-centered care,” “interprofessional communication,” “participatory leadership,” “conflict resolution,” “transparency of duties and responsibilities,” and “teamwork.” The competence of “transparency of duties and responsibilities” was mentioned in all studies and is required for any collaboration.

Conclusions:

Interprofessional competencies provide quality, safety, and patient-centeredness through effective collaboration. Integrating interprofessional competencies into the educational curriculum, in-service training, and continue education is essential to form effective interprofessional collaboration.

Keywords: Interprofessional relations, intersectoral collaboration, professional competence, systematic review

Introduction

Healthcare systems face numerous challenges; therefore, they need to seek appropriate and economical solutions to provide healthcare services; effective collaboration among professionals and even various organizations is a requirement to meet the health needs of communities.[1,2] Ineffective physician–nurse collaboration has been recognized to adversely impact patients and organizational outcomes and even lead to nurses' job stress.[3] Although healthcare services need participation of nurses in clinical decision making, understanding the nursing process is a challenging issue.[4,5] Collaboration is a term used in all areas of health care such as research, education, and clinical practice. In fact, healthcare activities require people from a variety of professions and different clinical fields such as cancer care, palliative care, emergency services, healthcare research, and even healthcare budget allocation.[6,7,8] Participation or collaboration of individuals, groups, and organizations is an effective and efficient step in human social life. Collaboration along with empowerment of healthcare system helps realizing health goals.[9,10]

However, interprofessional collaboration can accelerate achieving the goals of healthcare system. Poor interprofessional collaboration among healthcare providers, especially clinical staff such as physicians and nurses, exacerbates existing healthcare challenges in addition to ignoring patient needs, and inaccurate and late diagnosis.[11,12,13] Failure to identify or late problem diagnoses, inadequate and scattered care, and even increased mortality are the results of a lack of competencies and interprofessional relationships in health workers. This situation is due to the existing divergence and lack of interprofessional collaboration reported in medical care[13] while positive and effective collaboration and communication among professionals can help improve the health of staffs in the workplace. Barriers to collaboration and interprofessional activities have organizational, environmental, and individual contexts, so it is necessary to explore the factors determining effective participation.[14] Interprofessional collaboration, which means cooperation of several healthcare providers from different professions with one another, with the patient, with the patient's family and the community, is one of the principles needed to improve healthcare providers' performance.[15] To this end, formal and international efforts began in 1980s to prepare healthcare professionals for collaborative activities in all areas of health care in different countries. In addition, the World Health Organization has provided a general framework that includes educational, health, and clinical management systems to achieve interprofessional collaboration. To this end, it is first necessary to start interprofessional training. Vocational training is a type of training that people learn from each other, about each other, and together to increase collaboration and improve patient.[2,16]

Determining the competencies underlying interprofessional collaboration is an important and necessary step. Competencies, as the basis for acquiring the knowledge and skills, are necessary for the success of interprofessional activities even for forming professional identity.[17,18] In medical sciences, competency is defined as “correct judgment and habit of using communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values and rethinking in daily activities with the aim of providing services to the community and individuals.”[19] Determining, measuring, and acquiring interprofessional qualifications required in healthcare lead to a standardized work environment.[20] In such a setting, interprofessional collaboration causes healthcare services to be high quality and, cost-effective, healthcare system becomes accountable and patient-centered.[21] The purpose of this study is to identify the interprofessional competencies introduced in healthcare systems so far.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)[22,23] in 2021. The inclusion criteria were limited to covering a population of healthcare professionals or students who experienced interprofessional collaboration or training, and the subject of interprofessional collaboration. Articles that did not determine interprofessional collaboration competencies were excluded from the study. The outcome was competencies that were identified with different tools. Data were extracted and analyzed through qualitative content analysis. Qualitative content analysis is a research method used to examine and identify words, concepts, themes, phrases, and sentences. Accordingly, the whole text is divided into semantic “themes” that contain specific words or a combination of words. These themes or codes contain a specific concept or component.[24]

Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, ProQuest, Science Direct, Emerald, Springer Link, Google Scholar, SID, and Magiran databases were searched to retrieve related articles. WHO, United Nations, and World Bank websites were also searched. We conducted database searches from January 2010 to December 2020. Relevant keywords were extracted from MeSH, related sources, and expert opinions. The obtained keywords were used to set the search strategy in each database. Persian databases were searched using a combination of related keywords.

According to the identified keywords, related studies were searched using the following strategy:

(Interprofessional OR Crossprofessional OR transprofessional OR Cross-professional OR trans-professional OR multiprofessional OR multidisciplinary OR Interdisciplinary OR Cross-Disciplinary OR transdisciplinary) AND (competence* OR qualification* OR capacity* OR capabilit* OR abilit* OR skill*) AND (collectivity OR association OR partnership OR intercommunity OR collaboration OR cooperation) AND (hospital* OR” health system*” OR “healthcare system*” OR “health care system*” OR” health service*” OR “healthcare service*” OR “health care service*”)

This systematic review included all quantitative and qualitative studies related to the study subject that demonstrated interprofessional activities in health care with a rich description of interprofessional competencies published in English or Persian between 2010 and 2020. Studies that were not related to the subject of the study and did not address interprofessional competencies in health care were excluded from the study.

After searching the databases and websites of mentioned organizations, the search results were entered into EndNote® software, and duplicates and overlaps were removed. First, the title and abstract of the articles were examined based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, the full text of the selected articles was reviewed by two members of the research team who had sufficient knowledge of the subject. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved with the opinion of a third expert. In addition, references of selected articles were examined to find possible relevant articles.

Due to the diversity of selected articles in terms of type and method, no special tools were used to evaluate the quality of the studies. At this stage, the articles were reviewed independently by two members of the research team using appropriate evaluation tools. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data were extracted after reviewing the full text of the selected articles based on a researcher-made data extraction form. The data extraction form included authors' name, year of publication, country, type of study, data collection tool, sample size, and interprofessional collaboration competencies in health care. Data were extracted independently by two members of the research team. Disagreements were resolved by a third expert on the subject under study. The extracted data were analyzed through qualitative content analysis. Textual data were extracted and then coded based on the response rate to the objectives of the study. In the next step, the codes were categorized based on coherence, similarities, or differences. By continuous and frequent comparison among categories, main categories and subcategories emerged, and their relationships were determined. Then, the results obtained from the analysis of articles were summarized and reported.

Ethical considerations

The protocol of this research was reviewed and approved by The Ethical Committee of Isfahan university of Medical Sciences, Iran (IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1399.634). Intellectual property rights were considered for all the authors.

Results

The first stage yielded 13708 articles from electronic databases using the search strategy. In addition, five articles were added by manually searching other valid data portals to make a final number of 13713 articles. In the next step, duplicates and overlaps were eliminated and 7267 articles remained. Two independent authors used systematic screening of titles to select articles about interprofessional competencies in health care, which yielded 151 articles. After reading the abstracts, 17 articles met the qualitative evaluation criteria and entered the final stage [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart

All 17 selected articles were thoroughly studied. These studies were conducted in different regions and countries. Most of these studies belonged to developed countries: four from the USA and four from Australia. One was conducted in Iran. Most studies were qualitative. Details of each article in terms of, year, type of qualitative study, sample, and data collection tools were examined. Table 1 presents a summary of each article regarding the competencies. The results of this study show how each healthcare sector attends to interprofessional competencies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the selected articles

| R | First Author | Year | Country | Study design | Study tools | Study sample | Sample size | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andersen, Peter Oluf, et al.[25] | 2010 | Denmark | Qualitative (framework analysis) | Individual semi-structured interviews | Nine physicians and two nurses from cardiology and anesthesiology departments in six university hospitals | 11 | Identifying non-technical skills to improve the interprofessional performance of the cardiac resuscitation team and barriers to performing of these skills. |

| 2 | Kendall, Margo L., et al.[26] | 2011 | Australia | Qualitative | Focus groups/expert practitioner panels/CR authority panel/the statewide survey | Community Rehabilitation (CR) practitioners | 115 | Determining interprofessional competencies in the field of community rehabilitation. |

| 3 | Tataw, David Besong[27] | 2013 | USA | Qualitative | Literature review, extant data review, nominal group techniques, and participant observation | Health and social care practitioners | Providing a set of core interprofessional competencies for education, training, and practice in the field of health and social care. | |

| 4 | Chan, Engle Angela, et al.[28] | 2013 | Hong Kong | Qualitative | Seminar discussions | Social work students | 32 | Investigating the students' perceptions and their performance of interprofessional competencies. |

| Community practice | Nursing students | 33 | ||||||

| Focus group interviews | ||||||||

| 5 | Hepp Shelanne L., et al.[29] | 2015 | Canada | Qualitative | Interviews | Six acute care units (surgical and medical) in three Alberta hospitals, 15–20 staff from each unit | 113 | Review of the status of competencies introduced in the framework of Canadian interprofessional health collaboration in six acute care centers. |

| 6 | Sakai Ikuko. 2017,[30] | 2017 | Japan | Quantitative | Questionnaire-based study | Health professionals | 2704, respond=1490 | Verification of the validity and reliability of the developed scale of practical measurement of interprofessional collaboration competencies |

| 7 | Haruta Junji. et al.[31] | 2018 | Japan | Qualitative (inductive thematic analysis) | World café method (structured conversational process in which groups of individuals discuss a topic at several tables) | Japan Association for Interprofessional Education (JAIPE) members, Mie university, healthcare organization | 161 | Preparation and development of a framework of interprofessional competencies for the Japanese health system. |

| 8 | McLaughlin Jacqueline E. et al.[32] | 2020 | USA | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (with a person, on the phone) | Pharmacists | 6 | Determining the main themes of interprofessional care models during the educational opportunities of pharmacy students. |

| 9 | Brewer, Margo L, et al.[33] | 2013 | USA | Descriptive | - | Existing interprofessional competency and capability frameworks from the UK, Canada, and the USA | Explaining interprofessional competencies at Curtin University. | |

| 10 | Jafari, Varjoshani Nasrin, et al.[34] | 2014 | Iran | Qualitative | Interview | Nurses, doctors, medical students | 22 | Identifying the underlying factors of interprofessional communication in the emergency department |

| 11 | Edelbring, Samuel et al.[35] | 2018 | Sweden | Quantitative/Qualitative | Questionnaire/expert panel | Nursing and medical students/Experienced IPL educators and researchers | 88 (answered the JSAPNC*) | Evaluation of two interprofessional collaboration questionnaires. |

| 84 (answered the RIPLS**) | ||||||||

| 12 | Jaruseviciene, Lina et al.[36] | 2019 | Lithuania | Qualitative/Quantitative | Focus group discussions/36-item cross-sectional questionnaire | Six focus group discussions were held with 27 general practitioners (GPs) and 29 community nurses (CNs) | 135 | Preparing and developing measurement tools for collaboration between nurses and physicians in primary healthcare |

| 13 | McElfish, Pearl Anna, et al,[37] | 2017 | USA | Quantitative (Interventional) | The online survey, retrospective pre/post-test design | Students from medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and radiologic imaging science | 98 | Evaluating an innovative program that combines interprofessional education with cultural competence. |

| 14 | Ansa, Benjamin E, et al.[38] | 2020 | USA | Cross-sectional | Online survey | Physicians, fellows and residents, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, respiratory therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, social workers, registered dietitians, pharmacists, and speech pathologists | 4252 | Demonstrating the attitudes of health workers of a large university center toward interprofessional collaboration |

| 15 | Mink, Johanna, et al.[39] | 2020 | Germany | Prospective pre-post-study with follow-up (part of the longitudinal mixed methods) | Questionnaire | Students | The impact of interprofessional competencies in communication, collaboration, coordination, teamwork, and interprofessional learning on interprofessional internships. | |

| 16 | Venville, Annie et al.[40] | 2020 | Australia | Pre-post-study design | Work Self-Efficacy Inventory (WS-Ei) | Students | 3524 | Investigating the impact of a three-day interprofessional training program called “Building a Great Health Team” |

| 17 | Bollen, Annelies et al.[41] | 2019 | Australia | Systematic review | Article | Database | 37 | Identifying the factors affecting interprofessional collaboration between general practitioners and community pharmacists |

*Jefferson Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Nurse Collaboration. **Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale

Competencies of interprofessional collaboration

Competencies identified for interprofessional collaboration were categorized into six domains: “patient-centered care,” “interprofessional communication,” “participatory leadership,” “conflict resolution,” “transparency of duties and responsibilities,” and “teamwork” [Table 2].

Table 2.

Interprofessional collaboration competencies in healthcare system

| Competency | Theme | Subtheme | Frequency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-centered care | Engagement | Consumer | 10 | Kendall et al., 2011; Hepp et al., 2015; Sakai et al., 2017; Haruta et al., 2018; McElfish et al., 2018; Jafari et al., 2020; Edelbring et al., 2018; McElfish et al., 2018; Ansa et al., 2020; Venville et al., 2020 |

| Community | ||||

| Patient | ||||

| Family | ||||

| Interprofessional communication | Communication | Relationship | 12 | Andersen et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2013; Hepp et al. 2015; Haruta et al., 2018; McElfish et al., 2018; Tataw et al., 2011; Mink et al., 2020; Jafari et al., 2020; Edelbring et al., 2018; McElfish et al., 2018; Ansa et al., 2020; Venville et al., 2020 |

| Interpersonal | ||||

| Participatory leadership | Leadership | Leadership | 5 | Andersen et al., 2010; Hepp et al. 2015; Mink et al., 2020; McElfish et al., 2018; Venville et al., 2020 |

| Conflict resolution | Reflection | Monitoring | 7 | Andersen et al., 2010; Kendall et al., 2011; Hepp et al. 2015; Haruta et al., 2018; McElfish et al., 2018; Ansa et al., 2020; Venville et al., 2020 |

| Standard | ||||

| Transparency of duties and responsibilities | Task | Boundaries | 17 | Andersen et al., 2010;Ansa et al., 2020; Bollen et al., 2019;Brewer et al., 2013; Chan et al., 2013;Edelbring et al., 2018; Haruta et al., 2018;Hepp et al., 2015; Jafari et al., 2020; Jaruseviciene et al., 2019;Kendall et al., 2011;McElfish et al., 2018;McLaughlin et al., 2020;Mink et al., 2020;Tataw et al., 2011;Venville et al., 2020;Sakai et al., 2017 |

| Clarification | ||||

| Professional | ||||

| Role contribution | ||||

| Teamwork | Team | Network | 12 | Kendall et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2013; Hepp et al. 2015; Haruta et al., 2018; McElfish et al., 2018; Tataw et al., 2011; Mink et al., 2020; Jafari et al., 2020; Edelbring et al., 2018; McElfish et al., 2018; Ansa et al., 2020; Venville et al., 2020 |

| Collaboration |

Competence of “patient-centered care”

Patient-centered care is one of the two main competencies. Patient-centered healthcare services, as one of the axes of the healthcare system, ensure the safety and quality of healthcare in models and frameworks of interprofessional collaboration.[17,34]

Competence of “interprofessional communication”

Competence in interprofessional communication is the second major competence. This competence provides communication among various healthcare professionals and facilitates sharing knowledge, ideas, and values regarding patients, clients, their family, and the community. Competency of communication has been studied and emphasized in studies from both intra-professional and extra-professional perspectives.[32]

Competence of “participatory leadership”

This competence creates a secure work environment that supports the participation of healthcare providers, facilitates interprofessional relationships, and facilitates the exchange of information.[26]

Competence of “conflict resolution”

Conflict resolution provides the ability to examine the perception, performance, feelings, and values of other employees and the experience of an advanced collaboration.[32]

Competence of “teamwork”

This competence in employees leads to an understanding of the team and its capabilities and enables effective interprofessional cooperation.[29]

Competence of “transparency of duties and responsibilities”

This competence helps employees understand their own and others' duties and use one another's knowledge and skills to perform the right task.[32] Interprofessional competencies can be identified through interviews with healthcare team members, expert participation at clinical, educational, and policy levels.[26,32] Another method is to examine the factors affecting participation and team activities, and willingness to participate using available standard questionnaires such as Jefferson Scale of Attitudes Towards Physician-Nurse Collaboration (JSAPNC) and the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS).[35] Educational programs, including curricula and in-service training, are also effective in creating and strengthening interprofessional competencies.[33] Interprofessional competency of “transparency of duties and responsibilities” had the highest repetition in studies, followed by “teamwork.”

Discussion

In this study, we tried to identify the competencies of interprofessional collaboration in health care. The included studies listed a large number of competencies with requirements and characteristics of interprofessional collaboration. This extensive definition is due to the novel use of the term “interprofessional” in healthcare and medical literature as well as the ambiguity and lack of transparency is the word competence. As such, even different words have been used for the same concept.[42,43,44] Many medical guidelines designed for teamwork focus mainly on clinical skills while the lack of leadership and teamwork skills needed by healthcare professionals cause numerous problems. Furthermore, changing from acute disease care to chronic disease care, accountability and responsive care need collaboration from different fields of clinical, health, and social workers. Employees who have acquired their own professional competencies cannot meet the health needs of communities because professional competence alone is not enough.[45] It should be noted that the purpose of determining interprofessional competencies is to carry out effective interprofessional collaboration to meet principles such as safety, quality, and patient-centered healthcare. In other words, interprofessional activity is a strategy in line with the goals of healthcare services. Interprofessional collaboration between midwives and physician can improve women's and maternal health indicators.[5,46]

So far, Canada, the USA, and the UK have introduced competencies for healthcare professionals. Since each country has a different healthcare system and sociocultural conditions, it is essential that each country determines its competencies.[47]

Another noteworthy point is the importance of educational programs in the field of interprofessional collaboration and related competencies. Integrating interdisciplinary training programs based on competency in knowledge, attitude, and working with others and the community helps healthcare providers gain a new understanding of health care. Weaknesses in the integration of interprofessional competency training can lead to a decrease in the ability to apply the knowledge learned in practice.[40,48]

However, more than a decade has passed since interprofessional education started, but interprofessional education has not been integrated into the curricula of many countries and even universities of healthcare sciences in developed countries.[32] Even the declared interprofessional competencies deal only with interpersonal communication while healthcare activities take place within health organizations. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the competencies of organizations to create and develop interprofessional services.[28]

One of the limitations of this study was that only Persian and English studies were included in the review. This can cause publication bias. Another limitation was that due to the methodological diversity of the selected articles, the quality assessment was not done.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study showed that identifying interprofessional competencies for effective interprofessional collaboration is a necessity for healthcare systems because interprofessional collaboration can help alleviate the existing challenges and achieve healthcare goals. Despite its importance, determining interprofessional competencies is at its early stages, and only interpersonal relations are addressed.

The integration of interprofessional competencies in different professional curricula along with in-service training is essential for institutionalizing competencies and forming effective interprofessional collaboration. The competencies introduced in this study can be used to develop educational programs and training models for interprofessional collaboration of healthcare providers.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgements

The present study was part of a PhD thesis in Management of Health Services. We appreciate and thank Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for funding this project (Project number IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1399.634).

References

- 1.Nester J. The importance of interprofessional practice and education in the era of accountable care. N C Med J. 2016;77:128–32. doi: 10.18043/ncm.77.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croker A, Fisher K, Smith T. When students from different professions are co-located: The importance of interprofessional rapport for learning to work together. J Interprof Care. 2015;29:41–8. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.937481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabone M, Mazonde P, Cainelli F, Maitshoko M, Joseph R, Shayo J, et al. Everyday ethical challenges of nurse-physician collaboration. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27:206–20. doi: 10.1177/0969733019840753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rostami H, Rahmani A. Correlation between nurse's occupational stress and professional communications between nurses and physicians. J Education & Ethics In Nursing. 2015;3:31–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowles D, McIntosh G, Hemrajani R, Yen M-S, Phillips A, Schwartz N, et al. Nurse–physician collaboration in an academic medical centre: The influence of organisational and individual factors. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:655–60. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1201464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melender H-L, Hkkن M, Saarto T, Lehto JT. The required competencies of physicians within palliative care from the perspectives of multi-professional expert groups: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00566-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green BN, Johnson CD. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: Working together for a better future. J Chiropr Educ. 2015;29:1–10. doi: 10.7899/JCE-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehrolhassani MH, Dehnavieh R, Haghdoost AA, Khosravi Evaluation of the primary healthcare program in Iran: A systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24:359–67. doi: 10.1071/PY18008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves S, Xyrichis A, Zwarenstein M. Teamwork, Collaboration, Coordination, and Networking: Why We Need to Distinguish between Different Types of Interprofessional Practice. J Interprof Care. 2018;32:1–3. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, Goldman J, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017:CD000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irajpour A, Farzi S, Saghaei M, Ravaghi H. Effect of interprofessional education of medication safety program on the medication error of physicians and nurses in the intensive care units. J Educ Health Promot. 2019:8. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_200_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vafadar Z, Vanaki Z, Ebadi A. An overview of the most prominent applied models of inter-professional education in health sciences in the world. Res Med Educ. 2016;8:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keshmiri F. Assessment of the interprofessional collaboration of healthcare team members: Validation of Interprofessional Collaborator Assessment Rubric (ICAR) and pilot study. J Mil Med. 2019;21:647–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schot E, Tummers L, Noordegraaf M. Working on working together. A systematic review on how healthcare professionals contribute to interprofessional collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2020;34:332–42. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1636007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golom FD, Schreck J. The journey to interprofessional collaborative practice: Are we there yet? Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018;65:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khajehghyasi RV, Jafari SEM, Shahbaznejad L. A survey of the perception of interprofessional education among Faculty Members of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. Strides Dev Med Educ. 2017:14. doi: 10.5812/SDME.64086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mink J, Mitzkat A, Mihaljevic AL, Trierweiler-Hauke B, Gtِsch B, Schmidt J, et al. The impact of an interprofessional training ward on the development of interprofessional competencies: Study protocol of a longitudinal mixed-methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1478-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romمo GS, Sل M. Competency-based training and the competency framework in gynecology and obstetrics in Brazil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2020;42:272–88. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1708887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riskiyana R, Claramita M, Rahayu G. Objectively measured interprofessional education outcome and factors that enhance program effectiveness: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;66:73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safabakhsh L, Irajpour A, Yamani N. Designing and developing a continuing interprofessional education model. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:459–7. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S159844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asar S, Jalalpour S, Ayoubi F, Rahmani M, Rezaeian M. PRISMA; preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2016;15:68–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr J Emerg Med. 2017;7:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinheksel A, Rockich-Winston N, Tawfik H, Wyatt T. Demystifying content analysis. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020:84. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen PO, Jensen MK, Lippert A, طstergaard D. Identifying non-technical skills and barriers for improvement of teamwork in cardiac arrest teams. Resuscitation. 2010;81:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendall E, Muenchberger H, Catalano T, Amsters D, Dorsett P, Cox R. Developing core interprofessional competencies for community rehabilitation practitioners: Findings from an Australian study. J Interprof Care. 2011;25:145–51. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.523651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tataw DB. Individual, organizational, and community interprofessional competencies for education, training, and practice in health and social care. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2011;21:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan EA, Lam W, Lam Yeung SK-S. Interprofessional competence: A qualitative exploration of social work and nursing students' experience. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52:509–15. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20130823-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hepp SL, Suter E, Jackson K, Deutschlander S, Makwarimba E, Jennings J, et al. Using an interprofessional competency framework to examine collaborative practice. J Interprof Care. 2015;29:131–7. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.955910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakai I, Yamamoto T, Takahashi Y, Maeda T, Kunii Y, Kurokochi K. Development of a new measurement scale for interprofessional collaborative competency: The Chiba Interprofessional Competency Scale (CICS29) J Interprof Care. 2017;31:59–65. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1233943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haruta J, Yoshida K, Goto M, Yoshimoto H, Ichikawa S, Mori Y, et al. Development of an interprofessional competency framework for collaborative practice in Japan. J Interprof Care. 2018;32:436–43. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2018.1426559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLaughlin JE, Bush AA, Rodgers PT, Scott MA, Zomorodi M, Roth MT. Characteristics of high-performing interprofessional health care teams involving student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84:7095. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewer ML, Jones S. An interprofessional practice capability framework focusing on safe, high-quality, client-centred health service. J Allied Health. 2013;42:45E–9E. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jafari N, Hosseini M, Khankeh H, Ahmadi F. Competency and cultural similarity: Underlying factors of an effective interprofessional communication in the emergency ward: A qualitative study. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2020;3:292–303. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edelbring S, Dahlgren MA, Edstrmِ DW. Characteristics of two questionnaires used to assess interprofessional learning: Psychometrics and expert panel evaluations. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1153-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaruseviciene L, Kontrimiene A, Zaborskis A, Liseckiene I, Jarusevicius G, Valius L, et al. Development of a scale for measuring collaboration between physicians and nurses in primary health-care teams. J Interprof Care. 2019;33:670–9. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1594730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McElfish PA, Moore R, Buron B, Hudson J, Long CR, Purvis RS, et al. Integrating interprofessional education and cultural competency training to address health disparities. Teaching Learn Med. 2018;30:213–22. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2017.1365717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ansa BE, Zechariah S, Gates AM, Johnson SW, Heboyan V, De Leo G, editors. Attitudes and behavior towards interprofessional collaboration among healthcare professionals in a large academic medical center. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8:323. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8030323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mink J, Mitzkat A, Krug K, Mihaljevic A, Trierweiler-Hauke B, Gtِsch B, et al. Impact of an interprofessional training ward on interprofessional competencies–a quantitative longitudinal study. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2021;35:751–9. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1802240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venville A, Andrews P. Building great health care teams: enhancing interprofessional work readiness skills, knowledge and values for undergraduate health care students. Journal of interprofessional care. 2020;34:272–5. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1686348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bollen A, Harrison R, Aslani P, van Haastregt JC. Factors influencing interprofessional collaboration between community pharmacists and general practitioners—A systematic review. Health & social care in the community. 2019;27:e189–e212. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwindt R, Agley J, McNelis AM, Hudmon KS, Lay K, Bentley M. Assessing perceptions of interprofessional education and collaboration among graduate health professions students using the Interprofessional Collaborative Competency Attainment Survey (ICCAS) Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice. 2017;8:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jamil R. What is wrong with competency research? Two propositions. Asian Social Science. 2015;11:43.. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chamberlain-Salaun J, Mills J, Usher K. Terminology used to describe health care teams: an integrative review of the literature. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2013;6:65.. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S40676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khossravi Shoobe J, Khaghanizade M, Parandeh A, vafadar Z. Effectiveness of Educational Workshop based on interprofessional approach in Changing Health Science Students' Attitudes towards Interprofessional Learning and Collaboration. %J Bimonthly of Education Strategies in Medical Sciences. 2019;12:125–33. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rayburn WF, Jenkins CJO, Clinics G. Interprofessional Collaboration in Women's Health Care: Collective Competencies, Interactive Learning, and Measurable Improvement. 2021;48:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amini SB, Keshmiri F, Soltani Arabshahi K, Shirazi M. Development and validation of the inter-professional collaborator communication skill core competencies. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences. 2014;20:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hejri SM, Jalili M. Competency frameworks: universal or local. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2013;18:865–6. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]