Abstract

Background:

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed several ethical challenges worldwide. Understanding care providers’ experiences during health emergencies is key to develop comprehensive ethical guidelines for emergency and disaster circumstances.

Objectives:

To identify and synthetize available empirical data on ethical challenges experienced by health care workers (HCWs) providing direct patient care in health emergencies and disaster scenarios that occurred prior to COVID-19, considering there might be a significant body of evidence yet to be reported on the current pandemic.

Methods:

A rapid review of qualitative studies and thematic synthesis was conducted. Medline and Embase were searched from inception to December 2020 using “public health emergency” and “ethical challenges” related keywords. Empirical studies examining ethical challenges experienced by frontline HCWs during health emergencies or disasters were included. We considered that ethical challenges were present when participants and/or authors were uncertain regarding how one should behave, or when different values or ethical principles are compromised when making decisions.

Outcome:

After deduplication 10,160 titles/abstracts and 224 full texts were screened. Twenty-two articles were included, which were conducted in 15 countries and explored eight health emergency or disaster events. Overall, a total of 452 HCWs participants were included. Data were organized into five major themes with subthemes: HCWs’ vulnerability, Duty to care, Quality of care, Management of healthcare system, and Sociocultural factors.

Conclusion:

HCWs experienced a great variety of clinical ethical challenges in health emergencies and disaster scenarios. Core themes identified provide evidence-base to inform the development of more comprehensive and supportive ethical guidelines and training programmes for future events, that are grounded on actual experiences of those providing care during emergency and disasters.

Keywords: Ethics, clinical, healthcare workers, emergency treatment, standard of care, rapid review

Introduction

A newly emergent coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) first recognized in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, is responsible for causing COVID-19 disease. The severity of the disease and the widespread of its transmission prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it as a pandemic in March, 2020 (World Health Organization 2020).

Despite a significant focus on healthcare sector preparedness and response to this emergency, the serious health needs of many people have put healthcare services and providers under great pressure. This scenario has prompted medical associations, international organizations, and governments to offer clinical ethics guidelines for the pandemic (Joebges and Biller-Andorno 2020; Teles-Sarmento, Lírio-Pedrosa, and Carvalho 2021). Although not exclusively, most guidelines address issues related to health-resource limitations and frontline healthcare workers’ (HCWs) rights and obligations (World Medical Association 2017; McGuire et al. 2020; Leider et al. 2017; Joebges and Biller-Andorno 2020; Valera, Carrasco, and Castro 2021; World Health Organization 2016; Teles-Sarmento, Lírio-Pedrosa, and Carvalho 2021). However, these might not necessarily address the extent of the real-world ethical issues experienced by those delivering direct patient care (McGuire et al. 2020). The development of ethical guidelines has been criticized for lacking transparency in its standards and processes for the formulation and quality of the ethical recommendations provided (Mertz and Strech 2014). Accordingly, in order to improve the guidelines and the acceptability and quality of ethical recommendations the development should follow a systematic and transparent process (Mertz and Strech 2014). Mertz and Strech’s (2014) six-step approach for the development of ethical recommendations suggests that the first step should be to establish the full range of disease specific ethical challenges to improve the quality and appropriateness of the guideline, recommending a systematic review of issue-specific ethical challenges (Mertz and Strech 2014).

Qualitative evidence synthesis include different methodologies used for the systematic review of qualitative research evidence (Flemming et al. 2019). By synthetizing findings from studies of qualitative design, qualitative evidence synthesis offer a better understanding of complex and context-sensitive issues, such as participants’ behaviors, experiences and interactions around the issue being address (Flemming et al. 2019). The synthesis results go beyond individual studies and can contribute to inform new theories, policy and guideline development, clinical practice and areas in need of further research (Munn et al. 2014; Flemming et al. 2019). Given that the experience of ethical dilemmas is an underexplored and a highly context-sensitive field, qualitative data provides a better means to answer our research question. Accordingly, a preliminary review suggested that the great majority of potentially included studies were of qualitative design.

Published systematic reviews on ethical challenges in healthcare emergencies are either focused on context-specific: technological disasters (Khaji et al. 2018), group-specific: nurses (Johnstone and Turale 2014); pregnant women (Hummel, Saxena, and Klingler 2015); children and families (Hunt, Pal, et al. 2018) or focused on a particular issue: willingness to work (Aoyagi et al. 2015). We therefore conducted a rapid review of qualitative empirical bioethics literature focused on ethical challenges experienced by HCWs providing direct patient care during healthcare emergencies and/or disasters. Although some empirical research has been already published exploring ethical challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sperling 2021; Mazza et al. 2020; George et al. 2020; Friedman et al. 2021), there might be a significant body of evidence yet to be reported. Therefore, we excluded COVID-19 related data in this review.

The aim of this study is to identify and synthesize evidence from available qualitative studies on ethical challenges experienced by HCWs, in health emergencies and disasters, before COVID-19 pandemic. We hope that this evidence could inform new guidelines for future health emergencies and disasters, aiming to support good clinical practice and prevent moral distress and its negative impact on HCWs’ wellbeing and performance (Viens, McGowan, and Vass 2020).

Methods

Design

We conducted a rapid review of qualitative studies and thematic synthesis. The review design was based on a proposed approach for systematic reviews of empirical bioethics (Strech, Synofzik, and Marckmann 2008) together with Butler et al’s guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol (Butler, Hall, and Copnell 2016) and the Interim Guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group (Garritty et al. 2020). The included items in this review are reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement 2020 (Page et al. 2021).

The review protocol has not been published nor prospectively registered.

Eligibility criteria

We used the Methodology, Issues, Participants (MIP) model to define the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Strech, Synofzik, and Marckmann 2008) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Methodology | Empirical studies of qualitative design (i.e., studies using qualitative methods for data collection and data analysis). | Empirical studies of quantitative design. Empirical studies of mixed-methods design. Non-empirical studies including systematic reviews and theoretical papers. |

| Issue | Studies concerning ethical challenges experienced by healthcare workers delivering direct clinical care in the context of a health emergency or disaster. | Studies exploring ethical challenges in health emergencies or disasters, but focused on research ethics, vaccines, HIV, malaria and COVID-19 pandemic. Studies focusing on ethical challenges associated with public health management of health emergencies or disasters. Studies exploring participants’ views on hypothetical scenarios. Studies focused on evaluation or impact on training programmes. Studies assessing psychological impact/distress on health care workers. |

| Participants | Healthcare workers providing direct patient care. Studies with mixed populations were included if separate data for target participants was available. |

Healthcare workers who do not deliver direct patient care, including but not limited to: those working in institutional/organizational management level, public health, policy, administration. Volunteers and healthcare students. |

| Type of publication | Peer-reviewed studies published in English. No geographical or time limits were applied. |

Study protocols, conference abstract, theoretical reviews, book chapters, opinion letters, editorials, commentaries and gray literature. |

We operationalized three key concepts: (i) Health emergencies and disasters include any hazard – natural, man-made, biological, chemical, radiological and others, that implies a “disruption of the functioning of a community or a society causing widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses which exceed the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources” (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and World Meteorological Organization 2012); (ii) Ethical challenges were identified when study participants or study authors (Schofield et al. 2021b) reflect on uncertainties regarding how one should behave, act, or react in a certain situation, or when different values or ethical principles are compromised when making decisions (Hem et al. 2018); and (iii) HCWs providing direct patient care include: health professionals, health associate professionals, personal care workers in health services, support personnel, and other health service providers (World Health Organization 2008).

Search strategy

A literature search was conducted in Medline and Embase electronic databases, from inception to December 2020. Key words were related to “public health emergency” and “ethical challenges” and adapted for each database requirement. See the Medline search strategy in Table 2.

Table 2.

Medline search strategy.

| 1. Public health emergency.mp. | 10. Ethics/ or Ethics, Clinical/ or Ethic*.mp. or Ethics, Medical/ or Ethics, Professional/ |

| 2. Mass casualty incident.mp. or Mass Casualty Incidents/ | 11. Bioethics/ or bioethic*.mp. or Bioethical Issues/ |

| 3. Mass disaster.mp. | 12. moral*.mp. |

| 4. Disease outbreak.mp. or Disease Outbreaks/ | 13. Moral injury.mp. |

| 5. epidemic.mp. or Epidemics/ | 14. Moral distress.mp. |

| 6. Natural disaster.mp. or Natural Disasters/ | 15. disaster planning.mp. or Disaster Planning/ |

| 7. Pandemic.mp. or Pandemics/ | 16. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 |

| 8. Public Health Emergency of International Concern.mp. | |

| 9. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 | |

| 17. 9 and 16 | |

| 18. limit 17 to (books or chapter or conference abstract or conference paper or “conference review” or editorial or letter) | |

| 19. 17 not 18 | |

Retrieved references were managed using RefWorks® reference manager software. After deduplication, two authors (CM and MD) independently screened all titles/abstract against inclusion/exclusion criteria. Selected studies for full text review were dually screened (CM and DR) for final inclusion. Disagreements were discussed within the team, until consensus was reached. Data was independently extracted by two authors (CM and DR) using an Excel form including author, publication year, study setting (health emergency or disaster context, year and country), study objective and study design, data collection instruments, participants’ characteristics and study results relevant for the review aim. All texts included in the results section were considered as study findings (Thomas and Harden 2008; Noyes et al. 2018).

Data analysis

Aiming to produce a rich thematic description of the entire dataset (Braun and Clarke 2006), we conducted an inductive thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden 2008), for qualitative data analysis. This method was considered appropriate as it allows a more flexible approach to the different theoretical frameworks underpinning individual studies, and offered a well-structured approach that best fitted the research team’s skills and experience with qualitative data synthesis methods (Nowell et al. 2017). Two authors (CM and DR) independently conducted inductive line-by-line coding of individual study results. Codes and corresponding quotes were migrated to a Microsoft Excel® worksheet, an accessible alternative to the qualitative data analytic software (Bree and Gallagher 2016). The initial worksheet included three columns (i) study author, (ii) quote from original study, and (iii) code(s). These codes were then organized into descriptive themes after discussion within the authors, considering that individual codes could contribute to more than one theme/subtheme. Thereafter, each initial descriptive theme was sorted into different worksheets to facilitate further analysis. Then, each author independently revised the themes with the initial codes and quotes. Further group discussion led to checking several quotes to ensure accurate interpretation of the primary data and the review’s credibility (Nowell et al. 2017). Moreover, when considered appropriated, certain quotes were recoded and several codes were relocated into different themes/subthemes. Finally, multiple group discussion allowed for the refinement of themes and subthemes and its reorganization into broader descriptive themes and subthemes (Dixon-Woods et al. 2005), which were reviewed by all the authors to improve the trustworthiness of the results. A detailed description of study characteristics (country, healthcare emergency/disaster and participants’ role) are provided to help the readers to contextualize the findings and assess the transferability of the results (Nowell et al. 2017). We did not conduct quality appraisal for individual studies, neither assessed the confidence in the review findings.

This review included only published data and therefore did not require ethical approval.

Results

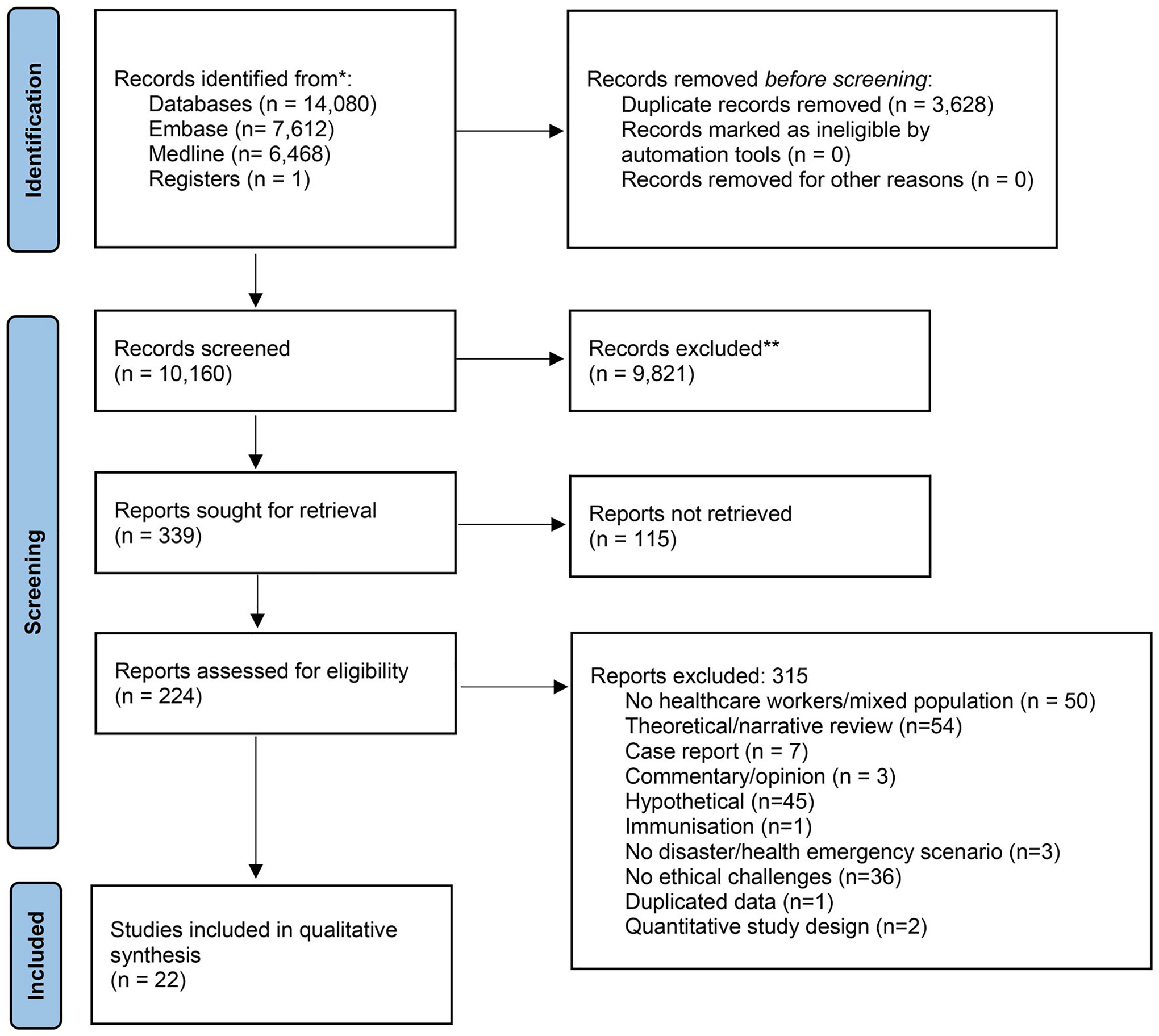

The electronic search retrieved 14,080 titles. After deduplication 10,160 titles/abstracts and 339 reports were sought for retrieval with 224 assessed in full text for eligibility. Finally, 22 articles were included in data synthesis. See PRISMA Flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram. *Records identified from each database and **excluded by automation tools and manually.

Description of included studies

We included 22 qualitative studies published between 2004 and 2020 and conducted in 15 countries. Studies addressed multiple health emergencies and disasters including: Infectious diseases (Severe acute respiratory syndrome -SARS 2003, Influenza -H1N1 2009, Middle East Respiratory syndrome -MERS-CoV2 2015, and Ebola Virus Disease -EVD 2014–2016), natural disasters (fires -San Diego 2007 and Tasmania 2012/13, hurricanes -Katrina 2005 and Wenchuan Earthquake), and three studies addressing unspecified health emergencies (multiple humanitarian, mass casualty and natural disaster crises). Detailed study characteristics are provided in Table 3 and an overview of characteristics of included literature in this review is shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies.

| First author publication year | Country of health emergency or disaster Setting |

Health emergency or disaster (year) | Study focus | Study design Instrument |

Study participants* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Al Knawy et al. 2019 | Saudi Arabia Hospital |

MERS- CoV (2015) | Perceptions of the operational and organizational management of a major outbreak. | Qualitative Semi-structured individual interviews and focus groups |

10 nurses 9 physicians |

| 2. | Almutairi AF, 2017 | Saudi Arabia Hospital |

MERS-CoV (2015) | Examine the perspectives of health professionals on an outbreak. | Qualitative Face-to-face semi-structured interview |

4 nurses 3 physicians |

| 3. | Bensimon CM, 2007 | Canada Hospital |

SARS (2003) | Characterize the views of individuals on the nature and limits of duty of care. | Qualitative In-depth, semi-structured interviews |

13 nurses 7 physicians 3 social workers 1 paramedic 1 respiratory therapist |

| 4. | Corley, Hammond, and Fraser 2010 | Australia Intensive Care Unit |

H1N1 (2009) | Document and describe the lived experiences of the nursing and medical staff caring for patients in the ICU with confirmed or suspected H1N1, during the influenza pandemic. | Qualitative Questionnaire with semi-structured, open ended questions and Focus group sessions |

Questionnaire 28 nurses 4 physicians Focus Group 12 nurses 4 physicians |

| 5. | Davidson J E, 2009 | USA Hospital |

Fires in san Diego, Us (2007) | Describe factors influencing the decision to come to work, during the san Diego fires and explore drivers affecting that decision. | Qualitative Focus group |

8 HCWs (roles not specified) |

| 6. | Draper H, 2017 | Sierra Leona Ebola treatment Unit |

Ebola (2014) | Identify and explore the ethical challenges the military personnel working in the Ebola treatment unit. | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

7 physicians 7 medical support staff 6 nurses |

| 7. | Gearing R, 2007 | Canada Children’s hospital |

SARS (2003) | Elucidate social workers’ experience during the SARS outbreak. | Qualitative Focus group |

19 social workers |

| 8. | Geisz-Everson M, 2012 | USA Hospital |

Hurricane Katrina (2005) | Describes the shared experiences of certified registered Nurse Anesthetists, who were on duty in New Orleans, during Hurricane Katrina. | Qualitative Focus group |

10 Nurses |

| 9. | Hunt M, 2018 | Rwanda, Jordan, and Guinée Not specified |

Multiple humanitarian crisis (Not specified) | Investigate humanitarian policy-maker and care providers’ moral experiences and perceptions of palliative care, during humanitarian crises. | Qualitative Interviews |

16 physicians 6 nurses 1 physical therapist |

| 10. | Kiani M, 2017 | Iran Not specified |

Multiple mass casualty incidents (Not specified) | Determine the personal factors affecting ethical performance in healthcare workers in disasters and mass casualty incidents, in Iran. | Qualitative Interviews |

21 HCWs |

| 11. | Koller D, 2006 | Canada Hospital |

SARS (2003) | Perceived experiences of (a) hospitalized children with probable or suspected SARS,1 (b) their parents, and (c) health care providers, who provided care to these children. | Qualitative In-depth ethnographic interviews |

8 HCWs (roles not specified) |

| 12. | Kunin M, 2015 | Australia, Israel and England Primary Care |

H1N1 (2009) | Challenges faced by primary care physicians, as they implemented pandemic policies in Australia, Israel and England, before the 2009/A/H1N1 pandemic vaccine became available. |

Qualitative In-depth semi-structured interviews |

65 physicians |

| 13. | Lam KK, 2013 | China Emergency Department | H1N1 (2009) | Gathered insight from emergency nurses in Hong Kong (HK) regarding their experience and perceptions toward work, during human swine influenza outbreak. | Qualitative Semi-structured, face-to-face individual interviews |

10 nurses |

| 14. | Lee JY, 2020 | Korea Hospital |

MERS (2015) | Experiences of Korean nurses who had directly cared for patients with middle East respiratory syndrome. | Qualitative In-depth interviews |

17 nurses |

| 15. | Li Y, 2015 | China Hospital | Wenchuan Earthquake (2008) | Explore the earthquake disaster experiences of Chinese nurses. | Qualitative Interviews |

15 nurses |

| 16. | Mak PW, 2017 | Australia Community pharmacy |

Tasmanian Bushfires (2012/13) | Explore the impacts of the 2012/2013 Tasmanian bushfires on community pharmacies. | Qualitative Semi-structured telephone interviews |

7 pharmacists |

| 17. | Mulligan JM, 2020 | Puerto Rico Not specified |

Hurricane Maria (2017) | What ethics of care were forged by health care workers and how do these ethics of care shape the work of recovery and enable resilience? | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

11 physicians 8 public or community HCWs 8 nurses 6 non-medical staff 3 other (pharmacy, PT, dental) |

| 18. | Pourvakhshoori N, 2017 | Iran Not specified |

Multiple natural disasters (Not specified) | Explore the experiences and perceptions of disaster nurses, regarding their provision of disaster health care services. | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

15 nurses |

| 19. | Straus SE, 2004 | Canada Hospitals |

SARS (2003) | To explore issues of medical professionalism, in the context of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a new emerging health threat. | Qualitative Semistructured, individual telephone interviews |

14 physicians |

| 20. | Tseng HC, 2005 | China Hospital |

SARS (2003) | Identify the key factors enabling the hospital to survive SARS unscathed. | Qualitative In-depth interviews |

4 nurses |

| 21. | Walker A, 2019 | Sierra Leona and Liberia Not specified |

Ebola (2014–2015) | Understand how the public health professionals involved in efforts to contain an outbreak experience ethical challenges, in this complex terrain. | Qualitative In-depth interviews |

8 HCWs (not specified) |

| 22. | Wright AL, 2020 | Australia Emergency department |

Ebola (2014) | Understanding of how the institutional work of custodians can maintain a place of social inclusion. | Qualitative Observational + field notes, interview, and archival data |

32 physicians |

SARS: Severe acute respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV2: Middle East Respiratory syndrome; EBV: Ebola Virus Disease; HCW: Healthcare workers

Table 4.

Characteristics of included data in review (n = 22).

| N (studies) | References (study number)* | |

|---|---|---|

| Study participants (n) | ||

| Physicians (168) | 10 | 1,2,3,4,6,9,12,17,19,22 |

| Nurses (146) | 13 | 1,2,3,4,6,8,9,13,14,15,17,18,20 |

| Social workers (22) | 2 | 3,7 |

| Paramedics (3) | 1 | 3 |

| Medical Support staff (7) | 1 | 6 |

| Respiratory therapist (3) | 1 | 3 |

| Healthcare worker (not specified) (56) | 5 | 5,10,11,17,21 |

| Physical therapist (1) | 1 | 9 |

| Pharmacist (7) | 1 | 16 |

| Non-medical staff (6) | 1 | 17 |

| Country | ||

| Australia | 4 | 4,12,16,22 |

| Canada | 4 | 3,7,11,19 |

| China | 3 | 13,15,20 |

| Iran | 2 | 10,18 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 1,2 |

| Sierra Leona | 2 | 6,21 |

| United States of America | 2 | 5,8 |

| England | 1 | 12 |

| Guinée | 1 | 9 |

| Israel | 1 | 12 |

| Jordan | 1 | 9 |

| Korea | 1 | 14 |

| Liberia | 1 | 21 |

| Puerto Rico | 1 | 17 |

| Rwanda | 1 | 9 |

| Health Emergency/Disaster | ||

| Infectious disease | ||

| SARS 2003 | 5 | 3,7,11,19,20 |

| Influenza H1N1 2009 | 3 | 4,12,13 |

| MERS-CoV 2015 | 3 | 1,2,14 |

| EBV 2014–2016 | 3 | 6,21,22 |

| Natural Disasters | ||

| Fires | 2 | 5,16 |

| Hurricanes | 2 | 8,17 |

| Earthquakes | 1 | 15 |

| Unspecified healthcare emergencies | 3 | 9,10,18 |

According to study number provided in Table 3.

SARS: Severe acute respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV2: Middle East Respiratory syndrome; EBV: Ebola Virus Disease; HCW: Healthcare workers

Synthesis of the evidence

We organized our findings into five major themes with subthemes, and provide representative quotes to illustrate them. To provide an overview of the review findings, Table 5 shows the main themes and sub-themes with contributing studies, and represented health emergency/disaster scenarios.

Table 5.

Main themes and subthemes with contributing studies and represented health emergency/disaster scenarios.

| Theme | Infectious disease outbreak | Disasters | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtheme (Contributing studies, according to key numbers provided in Table 3) | SARS (2003) | H1N1 (2009) | MERs-CoV2 (2015) | EBV (2014–2016) | San Diego fires (2007) | Tasmanian bushfires (2012) | Katrina Hurricane (2005) | Maria Hurricane (2017) | Wuenchuan Earthquake (2008) | Unspecified* |

| Vulnerability | ||||||||||

| (4,8,12,13,15,17,18,22) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Duty to care | ||||||||||

| Arguments grounding the duty to care (2,3,5,6,8,10,13,15,16, 18,19,22) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Balancing the duty to care against the risks and burdens (2,3,5,6,8,10,14,16,18,19,22) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Features of the duty to care (3,5,8,10,14,22) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Quality of care | ||||||||||

| Challenges to the provision of person and family centered care (4,7,9,11,12,13,14,19) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Resource allocation (6,9,10,12,16,18,22) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Competence and professionalism (10,12,14,15) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Management of Healthcare system | ||||||||||

| Institutional policies and local management (1–5,7,8,10,12,13,16,18,20–22) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Global healthcare management (8,12,21) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Sociocultural factors | ||||||||||

| Cultural competence of HCW (6,8,9,21) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Discrimination to HCW (1,2,7,14) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Global responsibility (1,4,7,21) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

SARS: Severe acute respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV2: Middle East Respiratory syndrome; EBV: Ebola Virus Disease; HCW: Healthcare workers

Vulnerability (Corley, Hammond, and Fraser 2010; Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012; Lam and Hung 2013; Kunin et al. 2015; Li et al. 2015; Wright et al. 2021; Pourvakhshoori et al. 2017; Mulligan and Garriga-López 2021).

The concept of vulnerability “reflects the fact that we all are born, live, and die within a fragile materiality that renders all of us constantly susceptible to destructive external forces and internal disintegration” (Fineman 2012, 71). By recognizing themselves as vulnerable, people also understand vulnerability as the need for care, responsibility and solidarity, and not the exploitation of this condition by others (Morais and Monteiro 2017).

Participants’ accounts illustrated the experience of vulnerability, as human beings susceptible to damage, suffering or death, in its individual and relational anthropological dimensions. At an individual level, uncertainty about risks and lack of knowledge on appropriate control and safety measures generated helplessness, fears of and guilt about themselves and/or their relatives becoming affected by the disease or by potential aggressions due to the chaos and violence caused by the crisis.

One of the things that needed to be considered was how to comfort the rescuers who went to the disaster area. Compared with the victims, our psychological problems also needed to be paid attention to.

(Nurse, China) (Li et al. 2015).

In addition to these factors, increased workload and pressure were also experienced as threats to participants mental health wellbeing, with many reporting anxiety, insomnia, fatigue, irritability, and substance abuse, as expressed by a participant: “I took to drinking [alcohol] every day for several weeks. I had to go back to work, so I couldn’t sustain that.” (Nurse, USA) (Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012, 210).

Participants also perceived their vulnerability in terms of their relationship with peers and patients, frequently identifying themselves with others’ vulnerability; caring for their colleagues or patients with whom they shared certain characteristics led them to reflect on their own mortality and a feeling of shared uncertainty and fears, blurring the distinction between patient and care provider.

…Cause now we were part of everyone, the thousands of people that were stranded all along [Interstate]10 and walking around in a daze … coming up to us, asking us for help. We needed help ourselves…

(Nurse, USA) (Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012, 209).

For some participants these feelings of shared vulnerability motivated a sense of solidarity within their community, helping and supporting each other, colleagues, and citizens, beyond their strict professional duties (Mulligan and Garriga-López 2021).

Duty to care

Duty to care refers to the healthcare professionals’ role-based responsibility to provide care to patients, even when this involves some degree of burden or risk to the clinician (McDougall 2014). Findings show that HCWs acknowledge they are normally exposed to certain known risks during their practice. However, emergency and disaster scenarios imply uncertain, and maybe greater risks, challenging the balance between their professional duty to care and the level of risk they ought or are willing to expose themselves and their families to. Findings around the duty to care were organized into three sub-themes:

Arguments grounding, and limiting, the duty to care

(Almutairi et al. 2018; Bensimon et al. 2007; Davidson et al. 2009; Draper and Jenkins 2017; Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012; Kiani et al. 2017; Lam and Hung 2013; Lee, Hong, and Park 2020; Mak and Singleton 2017; Pourvakhshoori et al. 2017; Straus et al. 2004; Wright et al. 2021; Li et al. 2015). Participants mentioned a diversity of arguments including those related to professionalism and deontological duty, as expressed by this nurse:

Everyone has to take their own responsibility towards the society. If I, as a nurse, retreated from the threats of influenza, who is going to help the sick people? It is a feeling of mission calling. I am doing what I need to do as a nurse, rather than act cowardly.

(Nurse, Hong Kong) (Lam and Hung 2013, 244).

Some participants pointed to explicit duties established in their employment contracts, which might also draw the limits to their duty; “I didn’t sign up for this” or “they don’t pay me enough to take this kind of risk”(Doctor, Canada) (Straus et al. 2004, 83).

Commitment toward their colleagues; spiritual beliefs, personal benefits, and an obligation coming of holding particular competences to perform certain clinical tasks were also described. For some participants, the differences among colleagues generated conflicts, critically judging those who did not attend to provide care. Particularly within those serving military and/or humanitarian action institutions, an over-arching duty to assist when required was recognized.

Balancing the duty to care against the risks and burdens

(Almutairi et al. 2018; Bensimon et al. 2007; Davidson et al. 2009; Draper and Jenkins 2017; Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012; Kiani et al. 2017; Lee, Hong, and Park 2020; Mak and Singleton 2017; Pourvakhshoori et al. 2017; Straus et al. 2004; Wright et al. 2021). Participants recurrently mentioned their personal safety as a critical factor to be considered. The burdens and emotional impact of uncertainty regarding risks, and access to appropriate professional protective equipment (PPE) was a conditioning element to participants’ disposition to responding to their duty.

As time goes by, the hospital’s atmosphere becomes more and more serious, as the severity of the symptoms increases and the number of patients increases, so the guidelines for protective equipment are constantly changing. As I became more and more anxious about what I was doing… I thought I could get MERS if I did wrong. I couldn’t say it, but my fears grew…

(Nurse, Korea) (Lee, Hong, and Park 2020).

Further on, family safety and household responsibilities (i.e., pet care, home security) are also considered in this balance implying certain limits to participants’ duty to provide care as reported by this nurse: “My most troubling things were, one, not knowing where my mother was….” Nurse, USA) (Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012, 208).

Among military workers, the duty to assist as a soldier was seen to overcome the obligations as a HCW and risk appeared to be less relevant and even an accepted threat of their occupation: “[…]if you join the Army you are expecting to get sent into risky places and the, the whole purpose of the Army is so that we can take that risk and so that the UK can remain safe” (Military medical personnel, UK) (Draper and Jenkins 2017, 77).

Features of the duty to care

(Bensimon et al. 2007; Davidson et al. 2009; Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012; Kiani et al. 2017; Lee, Hong, and Park 2020; Wright et al. 2021). Participants considered that their duty to care should not discriminate against individuals for their background, beliefs, medical condition, and associated risks to the provision of care. “Providing services on a preferential basis and in view of ethnicity, race, fellow citizenship, etc., is just unethical”(Participant, Iran) (Kiani et al. 2017, 346).

Additionally, participants considered that the duty to care has different degrees of obligatoriness; some regard this duty as an absolute commitment, while others consider it to have certain limits and even a voluntary call or a supererogatory duty under particular circumstances.

Quality of care

HCWs’ reported that their ability to deliver good quality care and achieve the desired health outcomes posed several ethical challenges. These were organized into three subthemes:

Challenges to the provision of person and family-centered care

(Corley, Hammond, and Fraser 2010; Gearing, Saini, and McNeill 2007; Hunt, Chénier, et al. 2018; Koller et al. 2006; Kunin et al. 2015; Lam and Hung 2013; Lee, Hong, and Park 2020; Straus et al. 2004). Lack of time and the use of PPE have a negative impact in communication and the ability to connect with patients, eventually affecting patients’ care. Participants experienced challenges in providing compassionate care and respecting patients’ dignity, feeling unable to address the emotional dimension, understanding patients’ preferences and values, and promoting patient’s autonomy and shared decision-making processes. These constraints, alongside to isolation caused by infectious control measures or to infrastructure destruction, were especially relevant when patients were dependent on other community members or required language translation support. Participants also expressed concerns that patient’s respect for privacy and confidentiality could not be guaranteed, i.e., conflicts around the use of cameras to monitor patients (Hunt, Chénier, et al. 2018), as mentioned by this participant: “That’s a huge piece of it too, like – not being on display for everybody, so having privacy, I think, when you’re talking about what’s important in palliative care, the dignity aspect is huge”(Participant) (Hunt, Chénier, et al. 2018, 12).

Additionally, new isolation and visiting policies challenged involvement of relatives into patients’ care and decision-making, which was considered especially relevant in pediatric and end-of-life care scenarios.

There were children in isolation who used the phone as a security object. There was one child who had the phone to his head all the time… In his sleep, he grabbed the phone and hung onto it like a teddy bear, because that was his line to his family.

(Social worker, Canada) (Gearing, Saini, and McNeill 2007, 23)

Resource allocation

(Draper and Jenkins 2017; Hunt, Chénier, et al. 2018; Kunin et al. 2015; Kiani et al. 2017; Mak and Singleton 2017; Pourvakhshoori et al. 2017; Wright et al. 2021). Triage and resource allocation were experienced as ethical challenges from different perspectives; when deciding which patient gets “the only ventilator in the red zone”(Draper and Jenkins 2017, 77) and, as referred by members of humanitarian groups, when institutional policies prevented the use of available resources (i.e., empty beds) that were meant to be saved for patients with a specific disease or a particular group of people (Hunt, Chénier, et al. 2018). In both scenarios, participants felt individual patients were receiving substandard care. Additionally, they expressed concerns that when no clear guidance is available, triage and prioritization decisions might follow questionable criteria, such as families’ pressures.

You know? Because the victims’ families pulled us to this side or that side, on the other hand, there was no plan. The priority of care delivery depends on who cries more, to attract the nurses’ attention to attend to their victims. Everyone tried to show that their patients were in more urgent need compared to the other patients

(Nurse, Iran) (Pourvakhshoori et al. 2017, 7)

Resource constraints, mostly in relation to staff availability, were particularly challenging in relation to end-of-life care scenarios, with several participants feeling that although compassion is central to responding to healthcare emergencies, it is largely neglected, prioritizing a focus on saving as many lives as possible.

I’ve literally watched hundreds of babies seize to death and it’s just a terrible… But I didn’t have a way of keeping them comfortable, and letting them die in a warm, comfortable place and that really haunts me.

(Participant) (Hunt, Chénier, et al. 2018, 12).

Competence and professionalism

(Kiani et al. 2017; Kunin et al. 2015; Lee, Hong, and Park 2020; Li et al. 2015). Participants acknowledged that either lack of training and preparedness, providing care outside their usual professional role and skills, or being emotionally affected by the situation limited the provision of standard care: “Knowledge and experience form the basis of ethical performance. Incompetent workers create problems for everyone”(Participant, Iran) (Kiani et al. 2017, 346).

In relation to emergencies resulting from new diseases, lack of evidence and training often implied the use of novel equipment and/or innovative and “off label” therapies, potentially posing patients at unknown risks and burdens.

I’ve never prescribed Tamiflu until the swine flu season… it was a bit nerve wracking, because you’re prescribing a drug you don’t really know much about, new territory, you don’t know the risks, you don’t know the pros, and it was a bit unsettling.

(Participant) (Kunin et al. 2015, 32)

Management of healthcare system

Participants reported how institutional policies and structural factors posed ethical challenges to the provision of direct patient care. These were organized into two themes representing different levels of decision-making:

Institutional policies and local management

(Al Knawy et al. 2019; Almutairi et al. 2018; Bensimon et al. 2007; Corley, Hammond, and Fraser 2010; Davidson et al. 2009; Gearing, Saini, and McNeill 2007; Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012; Kunin et al. 2015; Kiani et al. 2017; Lam and Hung 2013; Mak and Singleton 2017; Pourvakhshoori et al. 2017; Tseng, Chen, and Chou 2005; Walker et al. 2020; Wright et al. 2021). Participants mentioned the challenges posed by poor organizational management at their local institutions, including decisions being made following a top-down approach without incorporating concerns of those providing direct care and therefore, lacking coherence with actual problems.

Poor communication between management and frontline staff, top-down approaches in decision and policy making, and lack of consistent and clear guidelines affected participants’ confidence in their own safety and their clinical decision-making. This posed greater burdens on them and affected the relationship with their patients and the provision of care as shown by this comment: “Confusion about when people were no longer considered infectious… who decides this? No information to bedside nurses” (Nurse, Australia) (Corley, Hammond, and Fraser 2010, 581).

Participants highlighted the need to receive opportune, clear, and coherent guidelines and information about the emergency context and associated risks. HCWs praised the presence of a caring and collaborative institutional culture, which promoted respect for each other and greater commitment within teams.

“He often told us that employees’ lives can never be sacrificed, do our best, and that he would take full responsibility for everything. The Chief Executive said his attitude was one of fairness to every member of staff so he pads on each member of staff’s shoulder with the same weight”

(Nurse, Taiwan) (Tseng, Chen, and Chou 2005, 63)

Following institutional orders not considered appropriate to the context was a common challenge within studies; while military members felt forced to implement these decisions (Hunt, Chénier, et al. 2018), others advocated for a more pragmatic approach and the use of “common sense” in adapting rules to facilitate patients’ care (Mak and Singleton 2017). “You’ve got to be pragmatic about what you can have ready for a disaster. It is what it is. As I said, you do the best you can with the systems you’ve got available to you.”(Pharmacist, Australia) (Mak and Singleton 2017, 166)

More broadly, participants perceived how a lack of solidarity between different institutions generated an unequal and unfair allocation of resources.

Global healthcare management

(Kunin et al. 2015; Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012; Walker et al. 2020). From a systemic perspective, several participants referred to difficulties associated with poor service planning, unclear definitions of HCW’s roles during the emergency, allocation of responsibilities that exceed actual capacity and competences, and lack of integration of different service levels and providers, i.e., primary and secondary care. “I think there were a lot of uncertainties in my program as different guidelines were rolling in and out in terms of what you could or couldn’t do; I think a lot of staff were confused”(Social worker, Canada) (Gearing, Saini, and McNeill 2007, 23).

Sociocultural factors

This theme represents how the interactions of HCWs with broader society lead to ethical challenges in the provision of patient care. These were organized into four subthemes:

HCWs’ cultural competence

(Draper and Jenkins 2017; Hunt, Chénier, et al. 2018; Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012; Walker et al. 2020). Participants highlighted a need to integrate culturally diverse beliefs when providing care, especially those who were deployed to international settings. This aspect was mentioned in relation to the perceived noncompliance with healthcare advice and public health measures, and to those patients holding alternative and conspiracy theories. Instead of simply labeling these as wrong, they need to be explored and better understood to adequately address them.

Participants also described that cultural competence was relevant when caring for dying patients. They reported challenges due to the additional barriers posed by the infection control measures in understanding and respecting individuals’ own beliefs and values around death and dying, including management of death bodies and death rituals.

We had 2 deaths… [T]hat bothered me a lot because we took [1] body across the street to the garage and left it there, because our morgue was in the basement, and it was flooded, and I thought, my God, here it is, somebody’s family member.

(Nurse, USA) (Geisz-Everson, Dodd-McCue, and Bennett 2012, 208).

Discrimination to HCWs

(Almutairi et al. 2018; Al Knawy et al. 2019; Gearing, Saini, and McNeill 2007; Lee, Hong, and Park 2020). This challenge was only present in infectious disease outbreaks. Some participants suffered stigmatization and social isolation because of their role in caring for patients with infectious diseases. Some would avoid disclosing their roles to protect themselves and their families from being discriminated against. “I would find myself thinking about whether it was wise to go here or there and trying to make those decisions, balance what is reasonable and what might be better to not take part in”(Social worker, Canada) (Gearing, Saini, and McNeill 2007, 24).

Global responsibilities

(Corley, Hammond, and Fraser 2010; Gearing, Saini, and McNeill 2007; Al Knawy et al. 2019; Walker et al. 2020). Participants expressed concerns about the amount of PPE being used and disposed and the consequent environmental impact: ‘‘It was a huge number of big wheelie bins they had to take down, I think it was 80 in one day, full of masks and gowns” and “the workload was horrendous for the wards person staff” (Participant, Australia) (Corley, Hammond, and Fraser 2010, 581).

Additionally, the role of the media was questioned by participants, particularly when misrepresenting cultural attitudes regarding transmission through burial practices. Others perceived journalists contributed to the pressure put on HCWs by exacerbating the magnitude of the catastrophe.

Discussion

Main findings

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first structured review of empirical qualitative literature reporting ethical challenges experienced by frontline HCWs in emergency and disaster scenarios before the COVID-19 pandemic. This review includes studies conducted in eight different scenarios, 15 countries and participants with various occupations, providing a comprehensive view of ethical challenges from diverse perspectives. These challenges were grouped into five major themes; Vulnerability; Duty to care; Quality of care; Management of Healthcare system; and Sociocultural factors.

Many of the ethical challenges identified in this review are addressed and widely discussed in ethics guidelines on healthcare emergencies and disasters. However, as also found in other healthcare fields (Braunack-Mayer 2001; Schofield et al. 2021b), our findings suggest that HCWs providing direct patient care in emergency and disaster scenarios face a broader diversity of ethical challenges. This gap supports the promotion of bottom-up approaches and stakeholders’ involvement when developing ethical guidance to ensure these resources are coherent with real-world challenges.

Overall, most ethical challenges experienced by participants were common to the multiple emergency and disaster scenarios. However, some of them seem to be specific to certain situations (see Table 2). Military HCWs experienced dual-roles/obligations by holding both medical and military-based principles and duties which might diverge and thus pose additional difficulties in emergency circumstances. Also, particularly during infectious diseases outbreaks, HCW’s experienced issues associated with social isolation due to stigmatization and discrimination, and communication difficulties associated with the use of PPE.

The lived experience of vulnerability blurred the common vertical relationship, where patients are the vulnerable ones asking for help. The distinction between “they”, the patients, and “us”, the HCWs is diluted. Vulnerability is understood not merely restricted to the identification of certain groups in need of special protection but a wider relational concept where this shared condition of vulnerable human beings stands as the foundation of solidarity and responsibilities of care toward others (Delgado 2021).

Furthermore, vulnerability permeates into the four other major themes: the protection required by HCWs as fundamental feature of the duty to care; the importance of support and guidance by institutions and the social discrimination toward HCWs during infectious disease outbreaks. Additionally, when HCWs recognize themselves as being vulnerable it could contribute to build a better clinical relationship.

Regarding HCWs’ duty to care, the American Medical Association’s (AMA) first Code of Medical Ethics (1848) addressed the issue of personal risk during epidemics: “When pestilence prevails, it is [physicians’] duty to face the danger, and continue their labors for the alleviation of suffering, even at the jeopardy of their own lives” (American Medical Association 1848, 105) maintaining this guidance for nearly two centuries. In 2006, the AMA added a longer-term perspective “Physicians should balance immediate benefits to individual patients with ability to care for patients in future” (Morin, Higginson, and Goldrich 2006, 421), leaving decisions on the level of risk to be taken to individual discretion and based on beneficence to future patients, without considering doctors’ further obligations to themselves and their loved ones (Bailey 2010). With a different focus and emphasizing that responsibility toward patients’ safety is shared by individual nurses and institutional and health systems leaders, the latest version of the International Council of Nurses Code of Ethics (2021) also refers to the nurses’ responsibilities in being prepared and able to respond to emergencies and disasters (Internacional Council of Nurses 2021). Our findings are aligned with the existing wide consensus that for HCWs to exercise their duty to care, governments, institutions and society have a moral obligation to provide them with due protection and support. This shall not be limited to PPE and other physical safety measures, but also include emotional and psychological care and more broadly, protection to HCWs loved ones when appropriate.

The wide variety of reasons grounding the individuals’ duty to care add a layer of complexity to the definition of HCWs’ obligations to care during healthcare disasters. Acknowledging the diversity of individual reasons and thresholds allows for personal vulnerabilities and contextual factors - which could strengthen or debilitate this obligation- to be considered. However, differences among individuals might generate tensions within colleagues and potentially affect teamwork, the sense of cohesion and mutual respect.

HCWs’ understandings on their duty to care during emergencies should be explored within teams as a way to respect individuals’ judgements and set preparedness plans accordingly (Iserson 2020). Since the duty to care is mostly considered as an obligation of future healthcare professionals it should be discussed during training programs so that, when faced to the emergency situation, HCWs have already reflected on its implications and limits.

By requiring HCWs’ to switch into a public health approach where the focus is no longer the benefit of the individual patient but in benefiting the most, patients might receive substandard care when compared with normal circumstances. Many participants mentioned that the lack of clear and consistent triage and prioritization guidance, alongside with poor stakeholders’ involvement and lack of transparency in the guideline’s development process, lead to ethically challenging situations. Findings highlight the importance of a cohesive teamwork with a bottom-up approach and continuous effective communication, between different levels in maintaining the team’s morale, sense of belonging and mutual responsibility.

Participants were widely aware of their commitment to alleviate patients’ suffering but felt helpless in responding to it due to the primary focus on saving lives. Remarkably, most ethical guidelines mention the provision of compassionate end-of-life care as a minimum standard for those patients who will not receive lifesaving care after triage. However, findings suggest that this particular goal of medicine of relieving suffering (Hastings Center 1996) is actually challenged. There seems to be an inconsistency between the guidelines’ general recommendations on the provision of end-of-life care and the actual possibilities and resources for this to be feasible. Ensuring palliative care as a minimum standard of care in response plans should also be considered in preparedness plans and resource allocation decisions (Wynne, Petrova, and Coghlan 2020).

In a globalized world, cultural diversity is also a source of ethical challenges, particularly when faced with the need to modify death rituals and to understand how this might negatively impact relatives’ bereavement processes. Acquiring and practicing cultural humility, which implies respectful and active openness to differences, might be helpful in these circumstances where imposing restrictive measures will have a different impact for different cultural groups.

While ethical challenges are common and somehow inevitable in medical practice, the critical context during emergency and disaster emergencies exacerbates the likelihood of ethical challenges and consequently a greater risk of HCWs experiencing moral distress (Viens, McGowan, and Vass 2020; Morley et al. 2020). Initially described by Jameton in 1984, moral distress refers to “the experience of knowing the right thing to do while being in a situation in which it is nearly impossible to do it” (Jameton 2017, 617). Evidence suggests that moral distress leads to impaired competency and wellbeing among practitioners eventually impacting patients’ care (Lerkiatbundit and Borry 2009; Morley et al. 2019).

It is, however, important to note that by offering this synthesis of qualitative evidence and identifying the wider diversity of ethical challenges experienced by HCWs during healthcare emergencies and disasters, we do not attempt to draw any normative conclusion, i.e., as to how these ethical challenges ought to be experienced and/or solved (De Vries and Gordijn 2009). Instead, we aim to contribute to further ethical reflection and offer evidence to inform the development of more context-sensitive and relevant ethical guidelines to appropriately support clinicians.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first rapid review of empirical literature that provides an overview of clinical ethical challenges experienced by HCWs during health emergency and disasters. The review includes studies focused on a wide variety of contexts, different healthcare settings and diverse HCWs’ occupation. Although data suggest that particular fields will raise specific dilemmas, the overview provided by this synthesis allows a comprehensive view of ethical challenges that might inform the development of guidelines at institutional and system levels with a healthcare team rather than a profession/occupation-specific approach.

However, this review has some limitations. As a rapid review, only two electronic databases were searched and no citation and reference lists, nor gray literature were hand-searched, limiting the comprehensiveness of the review. Identifying ethical challenges within studies, both during the selection and data analysis processes, proved to be a difficult task since there is not a unique definition of what constitutes an ethical challenge (Schofield et al. 2021a). Consequently, there is a risk of having missed relevant studies and of overinterpretation or omission of ethical challenges during data analysis. These limitations were hopefully mitigated by independent dual screening and coding followed by multiple discussions within the whole research team. We did not conduct quality appraisal for included studies, neither assessed the confidence in the review findings and therefore validity and trustworthiness of the synthesis is not ensured.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that HCWs providing patient care in emergency and disaster scenarios face a diversity of ethical challenges in multiple dimensions of their caregiving roles. Core themes identified provide evidence to inform the development of comprehensive ethical guidelines and training programmes for current and/or future events that are grounded on actual experiences of those providing care during these scenarios. The development of clinical ethics guidelines should ensure a bottom-up approach, including frontline HCWs involvement. The provision of coherent and contingent support to frontline staff will reduce the risk of moral distress and its negative consequences for individual practitioners, institutions and individual patient’ care.

Funding

This work did not obtain funding.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Nothing to declare.

References

- Almutairi AF, Adlan AA, Balkhy HH, Abbas OA, and Clark A. 2018. “It feels like I’m the dirtiest person in the world.”: Exploring the experiences of healthcare providers who survived MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Infection and Public Health 11 (2):187–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. 1848. Code of ethics of the American Medical Association, adopted May 1847. Philadelphia: T.K. and P.G. Collins, printers. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-63310410R-bk. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi Y, Beck CR, Dingwall R, and Nguyen-Van-Tam JS. 2015. Healthcare workers’ willingness to work during an influenza pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 9 (3):120–30. doi: 10.1111/irv.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JE 2010. Virtual Mentor (Review). Ethics 12 (5):197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Bensimon CM, Tracy CS, Bernstein M, Shaul RZ, and Upshur R. 2007. A qualitative study of the duty to care in communicable disease outbreaks. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 65 (12):2566–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, and Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braunack-Mayer AJ 2001. What makes a problem an ethical problem? An empirical perspective on the nature of ethical problems in general practice. Journal of Medical Ethics 27 (2):98–103. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bree RT, and Gallagher G. 2016. Using Microsoft Excel to code and thematically analyse qualitative data: A simple, cost-effective approach. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education 8 (2):2811–2819. [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Hall H, and Copnell B. 2016. A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 13 (3):241–9. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley A, Hammond NE, and Fraser JF. 2010. The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (5):577–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JE, Sekayan A, Agan D, Good L, Shaw D, and Smilde R. 2009. Disaster dilemma: Factors affecting decision to come to work during a natural disaster. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal 31 (3):248–57. doi: 10.1097/TME.0b013e3181af686d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries R, and Gordijn B. 2009. Empirical ethics and its alleged meta-ethical fallacies. Bioethics 23 (4):193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2009.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado J 2021. Vulnerability as a key concept in relational patient- centered professionalism. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy 24 (2):155–72. doi: 10.1007/s11019-020-09995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, and Sutton A. 2005. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10 (1):45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper H, and Jenkins S. 2017. Ethical challenges experienced by UK military medical personnel deployed to Sierra Leone (Operation GRITROCK) during the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Ethics 18 (1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12910-017-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineman MA 2012. Elderly as vulnerable: Rethinking the nature of individual and societal responsibility. Elder Law Journal 20 (71):71–111. [Google Scholar]

- Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, Tunçalp Ö, and Noyes J. 2019. Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: Clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Global Health 4 (Suppl 1):e000882. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DN, Blackler L, Alici Y, Scharf AE, Chin M, Chawla S, James MC, and Voigt LP. 2021. COVID-19-related ethics consultations at a cancer center in New York City: A content review of ethics consultations during the early stages of the pandemic. JCO Oncology Practice 17 (3):e369–e376. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, Affengruber L, and Stevens A. 2021. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 130:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing RE, Saini M, and McNeill T. 2007. Experiences and implications of social workers practicing in a pediatric hospital environment affected by SARS. Health & Social Work 32 (1):17–27. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisz-Everson MA, Dodd-McCue D, and Bennett M. 2012. Shared experiences of CRNAs who were on duty in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina. AANA Journal 80 (3):205–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George CE, Inbaraj LR, Rajukutty S, and de Witte LP. 2020. Challenges, experience and coping of health professionals in delivering healthcare in an urban slum in India during the first 40 days of COVID-19 crisis: A mixed method study. BMJ Open 10 (11):e042171. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings Center. 1996. The goals of medicine. Setting new priorities. New York, USA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hem MH, Gjerberg E, Husum TL, and Pedersen R. 2018. Ethical challenges when using coercion in mental healthcare: A systematic literature review. Nursing Ethics 25 (1):92–110. doi: 10.1177/0969733016629770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel P, Saxena A, and Klingler C. 2015. Rapid qualitative review of ethical issues surrounding healthcare for pregnant women or women of reproductive age in epidemic outbreak. Cybrarians Journal 2 (37):1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt M, Chénier A, Bezanson K, Nouvet E, Bernard C, de Laat S, Krishnaraj G, and Schwartz L. 2018. Moral experiences of humanitarian health professionals caring for patients who are dying or likely to die in a humanitarian crisis. Journal of International Humanitarian Action 3 (1):12. doi: 10.1186/s41018-018-0040-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt M, Pal NE, Schwartz L, and O’Mathúna D. 2018. Ethical challenges in the provision of mental health services for children and families during disasters. Current Psychiatry Reports 20 (8):60–10. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0917-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Internacional Council of Nurses. 2021. The ICN code of ethics for nurses. Geneva. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iserson KV 2020. Healthcare ethics during a pandemic. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 21 (3):477–83. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameton A 2017. What moral distress in nursing history could suggest about the future of health care. AMA Journal of Ethics 19 (6):617–28. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.mhst1-1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joebges S, and Biller-Andorno N. 2020. Ethics guidelines on COVID-19 triage - an emerging international consensus. Critical Care 24 (1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02927-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone MJ, and Turale S. 2014. Nurses’ experiences of ethical preparedness for public health emergencies and healthcare disasters: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Nursing & Health Sciences 16 (1):67–77. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaji A, Larijani B, Ghodsi SM, Mohagheghi MA, Khankeh HR, Saadat S, Tabatabaei SM, and Khorasani-Zavareh D. 2018. Ethical issues in technological disaster: A systematic review of literature. The Archives of Bone and Joint Surgery 6 (4):269–76. doi: 10.22038/abjs.2018.22025.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiani M, Fadavi M, Khankeh H, and Borhani F. 2017. Personal factors affecting ethical performance in healthcare workers during disasters and mass casualty incidents in Iran: A qualitative study. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy 20 (3):343–51. doi: 10.1007/s11019-017-9752-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knawy BA, Al-Kadri H, Elbarbary M, Arabi Y, Balkhy HH, and Clark A. 2019. Perceptions of postoutbreak management by management and healthcare workers of a Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak in a tertiary care hospital: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 9 (5):e017476. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller DF, Nicholas DB, Goldie RS, Gearing R, and Selkirk EK. 2006. When family-centered care is challenged by infectious disease: Pediatric health care delivery during the SARS outbreaks. Qualitative Health Research 16 (1):47–60. doi: 10.1177/1049732305284010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin M, Engelhard D, Thomas S, Ashworth M, and Piterman L. 2015. Challenges of the pandemic response in primary care during pre-vaccination period: A qualitative study. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 4 (October):32. doi: 10.1186/s13584-015-0028-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KK, and Hung S. 2013. Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: A qualitative study. International Emergency Nursing 21 (4):240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Hong JH, and Park EY. 2020. Beyond the fear: Nurses’ experiences caring for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome: A phenomenological study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29 (17–18):3349–62. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leider JP, Debruin D, Reynolds N, Koch A, and Seaberg J. 2017. Ethical guidance for disaster response, specifically around crisis standards of care: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health 107 (9):e1–e9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerkiatbundit S, and Borry P. 2009. Moral distress part I: Critical literature review on definition, magnitude, antecedents and consequences. The Journal of Pharmacy Practice 1 (1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Turale S, Stone TE, and Petrini M. 2015. A grounded theory study of ‘turning into a strong nurse’: Earthquake experiences and perspectives on disaster nursing education. Nurse Education Today 35 (9):e43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak PW, and Singleton J. 2017. Burning questions: Exploring the impact of natural disasters on community pharmacies. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy : RSAP 13 (1):162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza M, Attanasio M, Pino MC, Masedu F, Tiberti S, Sarlo M, and Valenti M. 2020. Moral decision-making, stress, and social cognition in frontline workers vs. population groups during the COVID-19 pandemic: An explorative study. Frontiers in Psychology 11:588159. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.588159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall R 2014. Systematic reviews in bioethics: Types, challenges, and value. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 39 (1):89–97. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jht059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire AL, Aulisio MP, Davis FD, Erwin C, Harter TD, Jagsi R, Klitzman R, Macauley R, Racine E, Wolf SM, et al. 2020. Ethical challenges arising in the COVID-19 pandemic: An overview from the association of bioethics program directors (ABPD) task force. The American Journal of Bioethics 20 (7):15–27. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1764138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz M, and Strech D. 2014. Systematic and transparent inclusion of ethical issues and recommendations in clinical practice guidelines: A six-step approach. Implementation Science 9 (1):184. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais TCA, and Monteiro PS. 2017. Conceitos de Vulnerabilidade Humana e Integridade Individual Para a Bioética. Revista Bioética 25 (2):311–9. doi: 10.1590/1983-80422017252191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morin K, Higginson D, and Goldrich M. 2006. Physician Obligation in Disaster Preparedness and Response. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 15 (4):417–21. doi: 10.1017/s0963180106210521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley G, Ives J, Bradbury-Jones C, and Irvine F. 2019. What Is “ ‘moral distress’? A narrative synthesis of the literature”? Nursing Ethics 26 (3):646–62. doi: 10.1177/0969733017724354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley G, Sese D, Rajendram P, and Horsburgh CC. 2020. Addressing caregiver moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, June. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan JM, and Garriga-López A. 2021. Forging compromiso after the storm: Activism as ethics of care among health care workers in Puerto Rico. Critical Public Health 31 (2):214–25. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2020.1846683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Porritt K, Lockwood C, Aromataris E, and Pearson A. 2014. Establishing confidence in the output of qualitative research synthesis: The ConQual approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 14 (September):108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, and Moules NJ. 2017. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1):160940691773384. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, Garside R, Harden A, Lewin S, Pantoja T, Hannes K, Cargo M, and Thomas J. 2018. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group Guidance series-paper 3: Methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 97:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourvakhshoori N, Norouzi K, Ahmadi F, Hosseini M, and Khankeh H. 2017. Nurse in limbo: A qualitative study of nursing in disasters in Iranian context. PloS One 12 (7):e0181314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield G, Dittborn M, Huxtable R, Brangan E, and Selman LE. 2021a. Real-world ethics in palliative care: A systematic review of the ethical challenges reported by specialist palliative care practitioners in their clinical practice. Palliative Medicine 35 (2):315–34. doi: 10.1177/0269216320974277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield G, Dittborn M, Selman LE, and Huxtable R. 2021b. Defining ethical challenge(s) in healthcare research: A rapid review. BMC Medical Ethics 22 (1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12910-021-00700-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling D 2021. Ethical dilemmas, perceived risk, and motivation among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Ethics 28 (1):9–22. doi: 10.1177/0969733020956376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus SE, Wilson K, Rambaldini G, Rath D, Lin Y, Gold WL, and Kapral MK. 2004. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and its impact on professionalism: Qualitative study of physicians’ behaviour during an emerging healthcare crisis. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 329 (7457):83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38127.444838.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strech D, Synofzik M, and Marckmann G. 2008. Systematic reviews of empirical bioethics. Journal of Medical Ethics 34 (6):472–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.021709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teles-Sarmento J, Lírio-Pedrosa C, and Carvalho AS. 2021. What is common and what is different: Recommendations from European scientific societies for triage in the first outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Medical Ethics. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, and Harden A. 2008. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng H-C, Chen T-F, and Chou S-M. 2005. SARS: Key factors in crisis management. The Journal of Nursing Research 13 (1):58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, and World Meteorological Organization. 2012. Disaster risk and resilience. UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda.

- Valera L, Carrasco MA, and Castro R. 2021. Fallacy of the last bed dilemma. Journal of Medical Ethics. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2021-107333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viens AM McGowan CR, and Vass CM. 2020. Moral distress among healthcare workers: Ethics support is a crucial part of the puzzle. The BMJOpinion. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/06/23/moral-distress-among-healthcare-workers-ethics-support-is-a-crucial-part-of-the-puzzle/. [Google Scholar]

- Walker A, Kennedy C, Taylor H, and Paul A. 2020. Rethinking resistance: Public health professionals on empathy and ethics in the 2014–2015 Ebola response in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Critical Public Health 30 (5):577–88. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2019.1648763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2008. Classifying health workers : mapping occupations to the international standard classification, 1–14. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2016. Guidance for managing ethical issues in infectious disease outbreaks. Geneva: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Guidance. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2020. World Health Organization’WHO Director General’s Statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV)’. IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus (2019-NcoV). https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-ihr-emergency-committee-on-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov).

- World Medical Association. 2017. WMA - policy: Statement on medical ethics in the event of disasters. Chicago, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Wright AL, Meyer AD, Reay T, and Staggs J. 2021. Maintaining places of social inclusion: Ebola and the emergency department. Administrative Science Quarterly 66 (1):42–85. doi: 10.1177/0001839220916401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne KJ, Petrova M, and Coghlan R. 2020. Dying individuals and suffering populations: applying a population-level bioethics lens to palliative care in humanitarian contexts: Before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Medical Ethics 46 (8):514–25. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2019-105943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]