Abstract

We report an immunocompromised patient in Alabama, USA, 75 years of age, with relapsing fevers and pancytopenia who had spirochetemia after a tick bite. We identified Borrelia lonestari by using PCR, sequencing, and phylogenetic analysis. Increasing clinical availability of molecular diagnostics might identify B. lonestari as an emerging tickborne pathogen.

Keywords: Borrelia lonestari, relapsing fever, tick, bacteria, parasites, vector-borne infections, zoonoses, Alabama, United States

Tickborne diseases account for 77% of all vectorborne diseases reported in the United States, and incidence is increasing (1). The bacterium Borrelia lonestari was first detected in the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum, in 1996 and has since been detected in both ticks and vertebrate hosts in many southeastern states (2,3). When first discovered, B. lonestari was a proposed etiology of southern tick-associated rash illness after A. americanum tick bites, but extensive efforts to isolate the bacterium in rash biopsies were unsuccessful (4). We report the detection of B. lonestari in a patient with febrile illness after a tick bite, demonstrating the potential of this bacterium as a human pathogen.

In late April 2019, a 75-year-old man in Alabama sought care at The Kirklin Clinic of the University of Alabama (Birmingham, AL, USA) for extreme fatigue and relapsing fevers accompanied by chills, sweating, headache, and dizziness that had recurred 1 or 2 times each week for the previous 4 weeks. He had a history of low grade follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma and was receiving maintenance rituximab therapy. The patient had not traveled out of Alabama for several years but reported that he had removed an attached tick 4 weeks before symptom onset. The patient’s symptoms lasted ≈3 months before receiving a diagnosis. During this 3-month period, pancytopenia (lowest hemoglobin 9.3 g/dL; leukocytes, 2 × 109 cells/L; platelets, 120 × 109/L), mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase (216 IU/L), and mild hepatosplenomegaly, noted by computed tomography scan, developed in the patient. Physical examination revealed no skin lesions, lymphadenopathy, or organomegaly. Although the patient was evaluated by the oncology department for suspected recurrent lymphoma, the pathology laboratory reviewed a peripheral blood smear and reported the presence of spirochetes (Appendix Figure). Empirical oral treatment (100 mg doxycycline 2×/d) was initiated immediately. After the first dose, a fever developed in the patient, and he became stuporous. Emergent evaluation for an acute cerebrovascular stroke was negative. The patient returned to his baseline state of health within 24 hours and completed a full 10-day course of doxycycline without additional complications. His pancytopenia resolved in the subsequent months.

A blood sample from the patient was submitted to the University of Washington Medical Center Molecular Microbiology laboratory for broad-range bacterial PCR targeting the V1/V2 domains of the 16S rRNA gene (5). PCR yielded a high-quality 497-nt product (GenBank accession no. MN683828) that was sequenced and then classified by using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) of sequences from GenBank and the reference laboratory’s sequence database. The PCR product had 100% identity to 3 published 16S rRNA gene sequences from B. lonestari (GenBank accession nos. AY166715, AY682921, and U23211) and 99.79% identity to another published 16S rRNA gene sequence from B. lonestari (GenBank accession no. AY682920) (Table). Percentage nucleotide identity of the patient sequence to other Borrelia spp. with high-confidence identifications was below the laboratory’s standard threshold of 99.7% for species-rank classification.

Table. Summary of BLAST results for 16S rRNA gene sequences used to clinically identify bacteria found in the patient’s blood sample in study of relapsing fever caused by Borrelia lonestari after tick bite in Alabama, USA*.

| Species | GenBank accession nos. | % Identity† | Confidence‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. lonestari | AY166715, AY682921, U23211 | 100% | Published |

| B. lonestari | AY682920 | 99.79% | Published |

| B. turicatae | NC_008710, NZ_CP015629 | 98.38% | RefSeq |

| B. parkeri | NZ_CP005851 | 98.38% | RefSeq |

| B. venezuelensis | MG651649 | 98.38% | Unpublished |

| B. coriaceae | NR_114544, NR_121718, NZ_CP005745 | 98.38% | Type |

| B. miyamotoi | AB900817, LC164096, LC164108 | 98.38% | Published |

| B. hermsii | NC_010673, NR_102957 | 97.78% | Type |

*The V1/V2 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA bacterial gene was amplified by PCR and BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was used to align the patient’s sequences with reference sequences in GenBank. †Percentage identity with the 16S rRNA bacterial sequence from patient blood. ‡Confidence refers to level of curation for each reference sequence identified by using BLAST. Published indicates sequence record associated with peer-reviewed manuscript; RefSeq indicates records from curated GenBank RefSeq database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq); Type indicates sequence from type material; unpublished indicates minimally curated direct submission to GenBank not associated with a peer-reviewed manuscript.

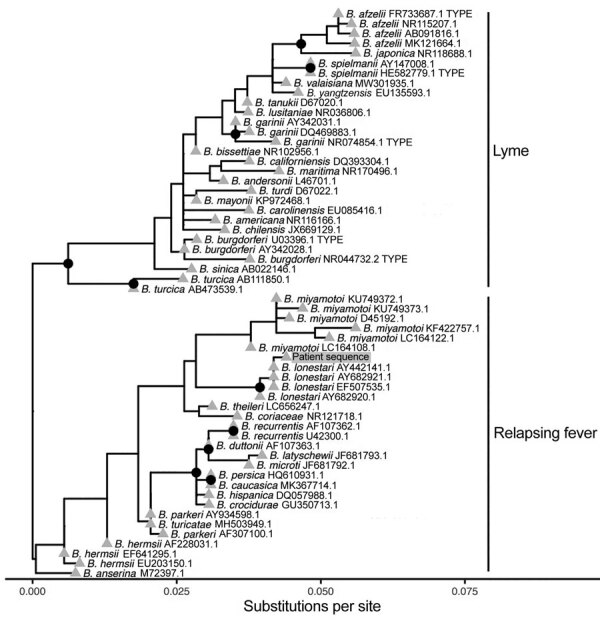

Because the clinical taxonomic classification was determined by a single locus, we retrospectively generated a single-locus phylogeny by using representative V1/V2 16S rRNA gene sequences to evaluate confidence in the clinical result (Figure) (6). The V1/V2 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis appropriately distinguished between Borrelia spp. causing Lyme disease and relapsing fever. We observed 2 well-resolved groups, and the bacterial sequence from the patient sample formed a high-confidence clade with B. lonestari sequences (bootstrap >0.95) (Figure). The B. lonestari clade was well-separated from other homogenous clades of Borrelia spp. causing relapsing fever, which had similarly high-confidence bootstrap values. The 2 clades most closely related to B. lonestari were B. miyamotoi and B. theilieri, recapitulating published Borrelia relapsing fever group phylogeny (7).

Figure.

Phylogenetic analysis of bacterial sequence derived from patient’s blood (gray shading) in study of relapsing fever caused by Borrelia lonestari after tick bite in Alabama, USA. Phylogenetic tree was constructed from representative V1/V2 regions of 16S rRNA gene sequences from different Borrelia spp. known to cause Lyme disease or relapsing fever. GenBank accession numbers are indicated after the species names. The bacterial sequence from the patient sample formed a high-confidence clade with B. lonestari sequences and was most closely related to B. miyamotoi. Nodes with >95% confidence bootstrap values are labeled with black circles, and branch tips are labeled with gray triangles.

The first reported human case of B. lonestari infection was identified in an elderly patient with an erythema migrans-like rash that developed after an A. americanum tick bite; PCR identified B. lonestari in both a skin biopsy and the removed tick (8). In contrast, the patient we report had a longer illness and a pattern of relapsing fevers, absence of erythema migrans, and a possible Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction after initiation of antimicrobial therapy. B. lonestari has not been previously reported to cause tickborne relapsing fever, but this manifestation is not unexpected given the close homology to B. miyamotoi, the cause of hard tick relapsing fever (9). The patient’s immunocompromised condition from CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy might also have affected the patient’s clinical manifestations.

The infrequency of reported B. lonestari infections despite the frequent isolation of the bacteria from host-seeking A. americanum ticks suggests that this species might have a lower pathogenic potential than other Borrelia spp. more often associated with human disease. However, this assumption is hindered by the difficult isolation of B. lonestari through classic laboratory methods, including culturing (2,10). This case and associated sequence analysis highlight the clinical utility of molecular diagnostics for patients with suspected tickborne diseases. Increasing availability of molecular diagnostics might enable B. lonestari to be identified as an emerging tickborne pathogen, particularly causing opportunistic infections among persons who are immunocompromised.

Additional information for relapsing fever caused by Borrelia lonestari after tick bite in Alabama, USA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefania Carmona for assistance in developing this manuscript.

The opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Biography

Dr. Vazquez Guillamet is an infectious disease specialist and tropical medicine diplomate completing doctoral studies on medicine and translational research at the University of Barcelona and the Barcelona Institute for Global Health.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Vazquez Guillamet LJ, Marx GE, Benjamin W, Pappas P, Lieberman NAP, Bachiashvili K, et al. Relapsing fever caused by Borrelia lonestari after tick bite in Alabama, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023 Feb [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2902.221281

Current affiliation: Barcelona Institute for Global Health, Barcelona, Spain.

References

- 1.Paules CI, Marston HD, Bloom ME, Fauci AS. Tickborne diseases—confronting a growing threat. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:701–3. 10.1056/NEJMp1807870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour AG, Maupin GO, Teltow GJ, Carter CJ, Piesman J. Identification of an uncultivable Borrelia species in the hard tick Amblyomma americanum: possible agent of a Lyme disease-like illness. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:403–9. 10.1093/infdis/173.2.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burkot TR, Mullen GR, Anderson R, Schneider BS, Happ CM, Zeidner NS. Borrelia lonestari DNA in adult Amblyomma americanum ticks, Alabama. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:471–3. 10.3201/eid0703.017323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wormser GP, Masters E, Liveris D, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB, Holmgren D, et al. Microbiologic evaluation of patients from Missouri with erythema migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:423–8. 10.1086/427289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SA, Plett SK, Luetkemeyer AF, Borgo GM, Ohliger MA, Conrad MB, et al. Bartonella quintana aortitis in a man with AIDS, diagnosed by needle biopsy and 16S rRNA gene amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2773–6. 10.1128/JCM.02888-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–80. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbour AG. Phylogeny of a relapsing fever Borrelia species transmitted by the hard tick Ixodes scapularis. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;27:551–8. 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James AM, Liveris D, Wormser GP, Schwartz I, Montecalvo MA, Johnson BJ. Borrelia lonestari infection after a bite by an Amblyomma americanum tick. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1810–4. 10.1086/320721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krause PJ, Schwab J, Narasimhan S, Brancato J, Xu G, Rich SM. Hard tick relapsing fever caused by Borrelia miyamotoi in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:1352–4. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varela AS, Luttrell MP, Howerth EW, Moore VA, Davidson WR, Stallknecht DE, et al. First culture isolation of Borrelia lonestari, putative agent of southern tick-associated rash illness. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1163–9. 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1163-1169.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information for relapsing fever caused by Borrelia lonestari after tick bite in Alabama, USA.