Abstract

Adult regeneration restores patterning of orthogonal body axes after damage in a post-embryonic context. Planarians regenerate using distinct body-wide signals primarily regulating each axis dimension: anteroposterior Wnts, dorsoventral BMP, and mediolateral Wnt5 and Slit determinants. How regeneration can consistently form perpendicular tissue axes without symmetry-breaking embryonic events is unknown, and could either occur using fully independent, or alternatively, integrated signals defining each dimension. Here, we report that the planarian dorsoventral regulator bmp4 suppresses the posterior determinant wnt1 to pattern the anteroposterior axis. Double-FISH identified distinct anteroposterior domains within dorsal midline muscle that express either bmp4 or wnt1. Homeostatic inhibition bmp4 and smad1 expanded the wnt1 expression anteriorly, while elevation of BMP signaling through nog1;nog2 RNAi reduced the wnt1 expression domain. BMP signal perturbation broadly affected anteroposterior identity as measured by expression of posterior Wnt pathway factors, without affecting head regionalization. Therefore, dorsal BMP signals broadly limit posterior identity. Furthermore, bmp4 RNAi caused medial expansion of the lateral determinant wnt5 and reduced expression of the medial regulator slit. Double RNAi of bmp4 and wnt5 resulted in lateral ectopic eye phenotypes, suggesting bmp4 acts upstream of wnt5 to pattern the mediolateral axis. Therefore, bmp4 acts at the top of a patterning hierarchy both to control dorsoventral information and also, through suppression of Wnt signals, to regulate anteroposterior and mediolateral identity. These results reveal that adult pattern formation involves integration of signals controlling individual orthogonal axes.

Introduction

Most animal forms are organized along orthogonal body axes. Bilaterian body plans typically involve head-to-tail (anteroposterior, AP), back-to-belly (dorsoventral, DV), and midline-to-lateral (mediolateral, ML) dimensions produced with high fidelity. Signals defining each body axis can function largely independently, and many animals use canonical Wnt signaling to regulate the AP axis and BMP signaling to regulate the DV axis (1-3). Definitive body axes emerge through embryogenesis from initial asymmetries generated either by maternal cues such as oocyte polarity (4) or symmetry-breaking events such as sperm entry, cavitation, or gastrulation (3, 5). However, the ability of some species to undergo whole-body regeneration as adults suggests embryogenesis can be unnecessary to maintain and restore axis orthogonality. In planarians, acoels, and Cnidarians, patterning along individual tissue dimensions has been attributed to distinct spatial signaling pathways (6-13). Because such organisms can re-establish body forms for many successive generations asexually, they could in principle inherit AP and DV asymmetries from each axis dimension separately, leading to independence of orthogonal axis information. Alternatively, perpendicular axis systems might instead interact to enable coordinated growth. How separate patterning systems integrate across axes to generate three-dimensional pattern in adulthood is relatively unexplored.

The freshwater planarian Schmidtea mediterranea is a model for studying the principles of adult axis patterning due to its ability to regenerate nearly any surgically removed tissue and undergo perpetual homeostasis in the absence of injury. These abilities are supported by adult pluripotent stem cells termed neoblasts that differentiate into any of the approximately 150 cell types comprising the adult animal and assemble into functional and appropriately positioned and scaled tissues (14, 15). Neoblasts undergo regionalized specialization to form subsets of progenitors fated for tissues located at particular axial locations such as the eyes, pharynx, and dorsal-versus-ventral epidermal cells (16-18). Neoblasts also hone to particular regions through their migratory ability (19-22) in order to form organs at particular locations in the body (23-25). Therefore, spatial information is critical for controlling progenitor function in order to maintain and regenerate the planarian body plan.

Spatial organization in regeneration and homeostasis is provided by a specialized set of signaling factors termed position control genes (PCGs) that are expressed regionally from body-wall muscle (26). Following amputations that truncate the body axis, PCG expression domains shift to provide tissue identity information, allowing for restoration of missing body regions (27, 28). The planarian AP axis is controlled by canonical β-catenin signaling involving the use of posteriorly expressed Wnts and their signaling outputs, and anteriorly expressed Wnt-inhibitors (7, 9, 27-30). The Wnt ligand wnt1 and secreted Wnt inhibitor notum are expressed at the posterior and anterior poles, respectively, where they organize tail and head patterning (7, 9, 27-29, 31). By contrast, the DV axis is established by BMP signaling. bmp4 is expressed in a mediolateral gradient within dorsal muscle and acts to promote dorsal fates while repressing ventral fates, through feedback inhibition of a ventrally and laterally expressed admp homolog (6, 10, 32-35). Fates along the ML axis are determined through the reciprocal antagonism of medial slit and the laterally expressed non-canonical Wnt ligand wnt5 (28, 36). slit inhibition results in a collapse of lateral tissues, such as eyes, onto the midline, while wnt5 inhibition causes opposite defects in which ectopic tissue, such as eyes, form laterally. Inhibition of PCG factors results in mis-patterning phenotypes both in amputated animals regenerating a new blastema and also in uninjured animals using neoblasts to maintain their bodies through homeostasis. Therefore, canonical Wnt, BMP, and Slit/Wnt5 signals constitutively control axis identities across three spatial dimensions, but the independence versus interrelationship between these signals is not fully understood.

Results

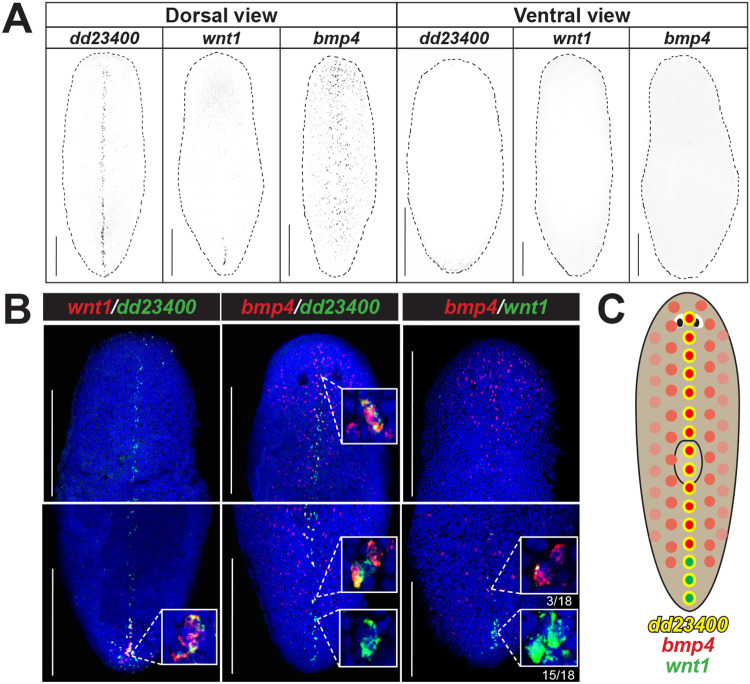

We sought to uncover possible relationships between key determinants of orthogonal body axes in planarians. We examined the expression of bmp4 and observed that in addition to the prominent dorsal-versus-ventral expression pattern with highest expression on the dorsal midline (6, 10, 37), bmp4 expression was stronger in the anterior versus posterior of the animal and reduced at the posterior tip (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, we noted that expression of wnt1, a master regulator of posterior identity, is selective to the dorsal and not ventral side of animals in the posterior tail approximately where bmp4 expression is lower (9, 28) (Fig. 1A). wnt1 is known to be co-expressed in a posterior subset of muscle cells specific to the dorsal midline marked by expression of dd23400 (38). We utilized double fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to examine the features of co-expression of dorsal posterior wnt1, dorsal bmp4, and dorsal midline dd23400 (Fig. 1B). Similar to results reported previously, dd23400 was co-expressed in 88.9% of wnt1+ cells (64/72 cells). Additionally, dd23400 and bmp4 were also co-expressed, as bmp4 expression was detected in 55.4% of dd23400+ cells (169/305 cells) throughout the dorsal midline, though at apparently reduced numbers in the tail tip. By contrast, bmp4 was only co-expressed in 12.1% of wnt1+ cells (4/33 cells) (Fig. 1B), with double-positive cells only present at the most anterior of the wnt1 domain. Within the posterior wnt1+ domain, wnt1+ cells in the anterior of the domain co-expressed bmp4 (3/18) while wnt1 cells in the posterior of the domain were bmp4-negative (15/18). These results suggest a model in which dd23400+ cells are partitioned into an anterior population co-expressing bmp4 and a population in the far posterior co-expressing wnt1, with a limited overlap (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. bmp4 and wnt1 co-express with dd23400+ dorsal midline cells in a regionally distinct manner.

(A) Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) detecting dd23400 on the dorsal midline, wnt1 on the dorsal posterior midline, and bmp4 in a dorsal midline-centered gradient with reduced expression in the far posterior. Scale bars represent 150 μm with dorsal or ventral views indicated. (B) Double FISH detecting co-expression of wnt1, dd23400, and bmp4. 88.9% of wnt1+ cells co-expressed dd23400 and 55.4% of dd23400+ cells co-expressed bmp4. Only 12.1% of wnt1+ cells co-expressed bmp4. Therefore, along dd23400+ dorsal midline muscle cells, wnt1 and bmp4 expression defines largely nonoverlapping AP domains within posterior. Within the wnt1+ domain of the representative image, wnt1+ cells in the anterior co-expressed bmp4 (3/18) whereas cells in the posterior of the domain lacked bmp4 co-expression (15/18). Scale bars represent 150 μm. (C) Schematic illustrating separation of bmp4 and wnt1 domains on the dorsal midline.

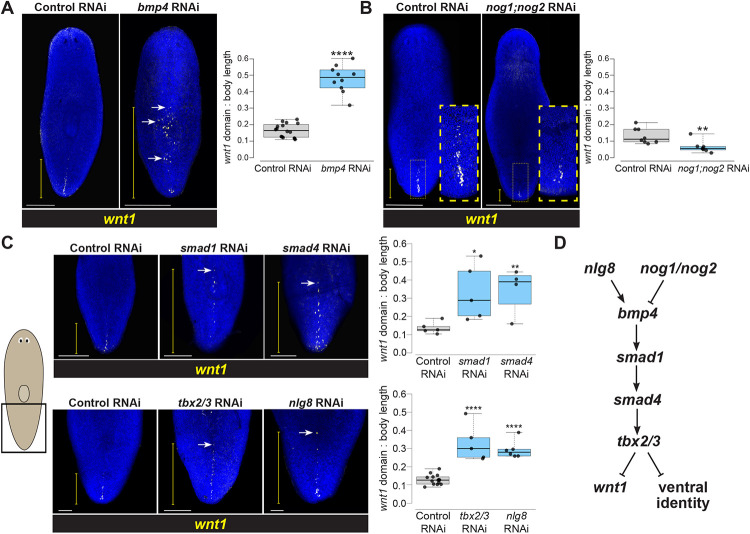

To test for possible functional relationships between bmp4 and wnt1, we first used RNA interference (RNAi) to examine the consequences of bmp4 inhibition. To circumvent the roles of bmp4 in directing expression of the injury-induced equinox gene essential for blastema outgrowth (39), we examined axis relationships using homeostatic RNAi in the absence of injury to specifically reveal possible interactions between axis patterning factors. After 14 days of bmp4 RNAi, the wnt1 expression domain expanded dramatically anteriorly, but retained dorsally restricted specificity (Fig. 2A). Expanded expression of wnt1 in bmp4(RNAi) animals was more sporadic and patchier compared to the normal wnt1 domain in control animals. In addition, wnt1 expression expanded laterally in bmp4(RNAi) animals. Together, these results indicate that bmp4 controls the AP limit of wnt1 expression.

Fig. 2. A BMP signaling pathway involved in DV identity restricts wnt1 expression to the posterior.

(A) FISH detecting wnt1 expression in animals following 14 days of homeostatic control or bmp4 RNAi. Inhibition of bmp4 expanded wnt1 expression toward the anterior (white arrow shows ectopic wnt1+ cells). (B) wnt1 expression domain reduced in nog1;nog2(RNAi) animals treated with dsRNA for 18 days of homeostasis (yellow boxes, magnified insets). (C) Top: FISH of wnt1 following 14 days of control, smad1, or smad4 RNAi Bottom: FISH detecting wnt1 after 18 days of control, tbx2/3, or nlg8 RNAi. Inhibition of these BMP signaling components results in anterior expansion of wnt1 expression. (A-C) White scale bars represent 150 μm, and yellow brackets indicate wnt1 AP expression domain size. Box plots showing the distance from the posterior tip of the animal to the most anterior wnt1 expression relative to body length after indicated treatments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p < 0.0001 by 2-tailed t-test; N ≥ 4 animals. Box plots show median values (middle bars) and first-to-third interquartile ranges (boxes); whiskers indicate 1.5× the interquartile ranges, and dots are data points from individual animals. (D) Pathway model for components acting in DV determination and control of wnt1.

To gain insights into whether BMP signaling acts permissively or instructively in regulation of wnt1, we inhibited Noggin homologs nog1 and nog2 known to negatively regulate bmp4 in planarian DV determination (33). Homeostatic inhibition of nog1 and nog2 for 18 days decreased the wnt1 expression domain (Fig. 2B), indicating that BMP signaling likely plays an instructive role in limiting posterior wnt1 identity.

We next examined whether this role of bmp4 in controlling a regulator of AP identity occurred via a canonical BMP pathway signaling through Smad1 and Smad4 effectors. Planarian smad1 and smad4 are known to mediate control dorsoventral identity along with bmp4 (6, 10). Following a 14-day inhibition, both smad1(RNAi) and smad4(RNAi) animals had significantly anterior expansion of wnt1 expression, phenocopying the effects of bmp4 RNAi on wnt1 (Fig. 2C, top). Given these results, we next investigated potential regulation of wnt1 by other factors known to act with BMP signaling to control dorsoventral identity. We examined the effects of inhibiting tbx2/3, a transcription factor hypothesized to act downstream of bmp4 for control of DV identity in Dugesia japonica (40). Following 18 days of tbx2/3 RNAi, wnt1 expression was likewise significantly expanded toward the anterior (Fig. 2C, bottom). Similarly, we investigated nlg8, a noggin-like gene that facilitates BMP signal activation, is expressed dorsally, and whose inhibition phenocopies the ventralization phenotypes observed after bmp4 RNAi (33). Homeostatic RNAi of nlg8 for 18 days caused expansion of the wnt1 domain (Fig. 2C, bottom). Taken together, these experiments provide support that a bmp4 signaling pathway closely linked to dorsoventral identity determination acts to restrict the expression domain of the posterior determinant wnt1 (Fig. 2D).

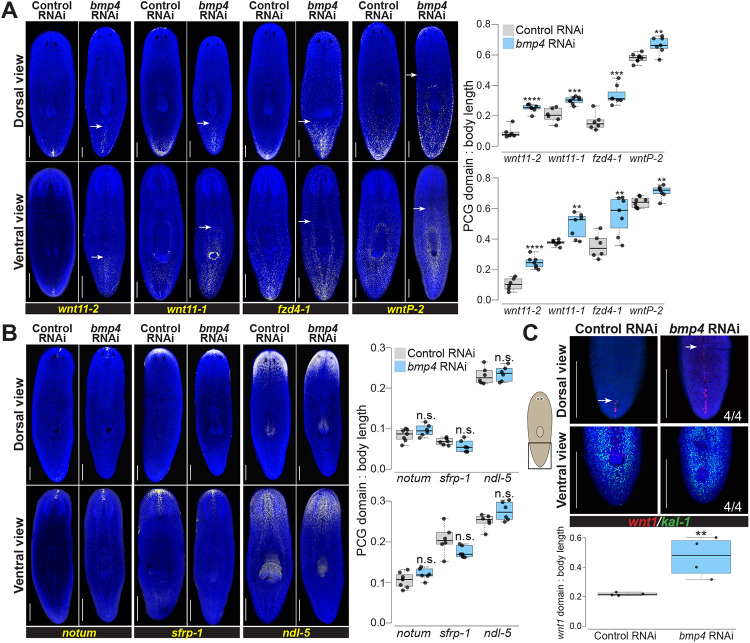

To investigate whether the role of BMP signaling was limited to wnt1 or more broadly affected posterior identity in general, we assessed expression of other posterior markers following 28 days of bmp4 RNAi. Posterior markers wnt11-2, wnt11-1, fzd4-1, and wntP-2 are expressed in successively broader posterior domains, have roles in tail and trunk patterning (7, 24, 30, 31, 41), and are expressed in a beta-catenin-dependent manner (42-44). Most known posterior markers such as these factors are expressed both dorsally and ventrally, unlike wnt1, but in regeneration their expression depends on wnt1 (27, 28). bmp4 inhibition expanded the domains of all four posterior markers in both their dorsal and ventral domains (Fig. 3A). Therefore, BMP signaling broadly limits posterior identity.

Fig. 3. bmp4 restricts posterior identity independent of DV control.

(A) Animals were fixed after 28 days of homeostatic control or bmp4 RNAi and stained by FISH as indicated for markers of the AP axis identity. bmp4 RNAi caused an anterior expansion of the posterior markers wnt11-2, wnt11-1, fzd4-1, and wntP-2 on both dorsal and ventral sides. White arrows indicate the expansion of posterior markers. (B) FISH stained animals following 28 days of control or bmp4 RNAi. bmp4 inhibition did not affect AP distribution of anterior markers notum, sfrp-1, or ndl-5. (A-B), Graphs show the measurement of indicated marker domains normalized by total length of animal (N ≥ 6 animals). (C) FISH showing wnt1 and ventral marker kal-1 expression comparing 14 days of control and bmp4(RNAi). Dorsal view (upper) shows that inhibition of bmp4 expanded wnt1 expression anteriorly (arrows indicate anterior-most wnt1+ cell) at a time prior to any dorsal expression of the ventral marker kal-1 expression (4/4 animals). Boxplot comparing wnt1 expression normalized by body length between control and bmp4(RNAi) animals (N = 4 animals). (A-C) Box plots shows median values (middle bars) and first-to-third interquartile ranges (boxes); whiskers indicate 1.5× the interquartile ranges and dots are data points from individual animals. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p<0.0001, n.s. indicates p>0.05 by 2-tailed t-test. Scale bars, 300 μm (A-B) or 150 μm (C).

By contrast, markers of far anterior identity did not appear to become restricted in bmp4 RNAi We stained bmp4(RNAi) animals for notum, sfrp-1, and ndl-5 in order to assess AP identity over a range of the anterior region (7, 9, 28, 29). Compared to control animals, there was no significant change in these expression patterns in the AP direction on either dorsal or ventral side of the animals (Fig. 3B). We note, however, that bmp4(RNAi) animals eventually form dorsal cephalic ganglia and an extra set of dorsal eyes (10). These transformations may impact anterior pattern expression to some degree, and we noted that the domain of ndl-5 expression, present throughout the head of normal animals, appeared mediolaterally modified after homeostatic bmp4 RNAi. However, our data suggest BMP’s role on the AP axis is primarily to regulate identity within the posterior.

Because bmp4(RNAi) animals undergo a progressive ventralization, we considered the possibility that ventral tissue identity might indirectly influence wnt1 expression in these animals. To ascertain possible relationships between ventralization and posteriorization phenotypes, we examined bmp4(RNAi) animals at an early time in their phenotypic progression after 14 days of dsRNA feeding, then simultaneously assessed both phenotypes. These animals had expanded wnt1 but not yet dorsal expression of the ventral epidermal marker kal-1 (Fig. 3C). However, longer-term bmp4 RNAi ultimately results in the dorsal expression of kal-1 as the epidermis becomes ventralized during tissue turnover (16). Therefore, our results suggest that the anterior wnt1 expansion after bmp4 RNAi is unlikely a secondary consequence of tissue ventralization and instead could represent a separate use of BMP signaling for planarian AP axis patterning.

Given that bmp4 and wnt1 expression were enriched in separate anterior and posterior domains, we further examined whether these genes might undergo mutual negative regulation. To test this possibility, we inhibited wnt1 homeostatically, followed by FISH to detect expression of bmp4. Following 14 days of wnt1 RNAi, tails began to retract and become bulged, as reported previously (38). In these animals, the bmp4 expression pattern was altered to be expressed more highly in the posterior of the animal but retained its dorsal specificity (Fig. S1). Therefore, inhibition of wnt1 permitted bmp4 expression in the dorsal posterior tip of the animal in a domain normally expressing wnt1. Together with the prior results, these experiments suggest a reciprocal antagonism between wnt1 and bmp4 to define each other’s expression boundaries and consequently pattern the posterior.

wnt1 also undergoes dramatic expression dynamics early in regeneration. Wound sites express wnt1 in muscle cells early after wounding, and optimal injury-induced wnt1 expression depends on bmp4 signals to induce expression of the novel secreted factor equinox, which in turn activates many injury-induced genes (39). In addition, regenerating tail fragments undergo an extensive remodeling of pre-existing territories so that regeneration restores the overall body proportionality without restoring absolute size. In regenerating tail fragments, wnt1 expression undergoes an initial anterior expansion along the midline by 18 hours post-amputation, followed by eventual restriction and re-establishment of a new AP axis through rescaling over several days (28). We tested whether bmp4 inhibition would affect these regeneration-dependent behaviors of wnt1 expression along the posterior midline in amputated tail fragments. In these animals, bmp4 RNAi resulted in an anterior expansion of the wnt1 domain from the homeostatic knockdown prior to amputation and so was present in animals fixed immediately after amputation (Fig. S2). By 18 hours, control tail fragments underwent an anterior expansion of wnt1 along the midline, while bmp4(RNAi) tail fragments retained an expanded wnt1 domain. However, bmp4(RNAi) animals underwent apparently normal resetting of wnt1 domains during the rescaling period by 96 hours, similar to control animals. By contrast, a prior study found that inhibition of the STRIPAK complex factor mob4 led to anteriorly expanded wnt1 but loss of regeneration-induced rescaling of wnt1 territories (38). Therefore, although bmp4 negatively regulates wnt1 homeostatically, it is unlikely that the reduction to the wnt1 expression domain through regenerative rescaling occurs through control of bmp4 under normal conditions. Furthermore, it is likely that bmp4 and mob4 act separately to control wnt1 expression.

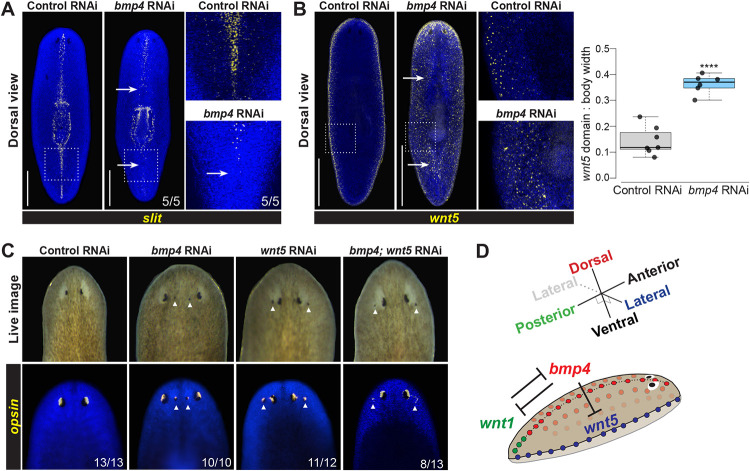

In light of the unexpected role of BMP signals in AP axis patterning, we next sought to clarify how bmp4 participates in ML axis regulation. bmp4 RNAi causes expansion lateral tissue (19) and also failure to produce lateral tissue after lateral amputations. In addition, bmp4 RNAi causes transverse regeneration to proceed with midline indentations (6, 10), likely because of bmp4’s role in dorsoventrally positioning the notum+ anterior pole during head blastema outgrowth (45). Furthermore, bmp4(RNAi) homeostasis animals form an extra set of eyes medially, consistent with this factor having additional roles in ML axis formation (6, 10). However, the relationship between bmp4 and other ML axis patterning factors slit and wnt5 is not fully understood. We next examined bmp4’s role in homeostatically maintaining midline marker expression. Following 28 days of bmp4 RNAi, expression of the midline determinant slit was reduced, particularly in the posterior of the animal (Fig. 4A). These results suggested that slit might function downstream of bmp4 for controlling midline information. Furthermore, inhibition of bmp4 reduced and disrupted the dd23400 midline expression pattern and expanded its expression domain laterally (Fig. S3A), suggesting BMP controls midline identity broadly. Taken together, these data suggest that bmp4 promotes medial identity and is important for establishing the boundaries of medial territories.

Fig. 4. bmp4 regulates ML patterning upstream of lateral wnt5.

(A-B) FISH detecting slit or wnt5 following 28 days of homeostatic control or bmp4 RNAi. Right panels show enlargements of boxed regions. Scale bars represent 300 μm. (A) bmp4 RNAi caused reduction of slit in the anterior and elimination in the posterior (arrows). (B) Inhibition of bmp4 caused medial expansion of wnt5 (arrows). Graph shows wnt5 expression domain width (dorsal side) normalized to body width. ****p<0.0001 by unpaired 2-tailed t-test; N ≥ 6 animals. Box plots show median values (middle bars) and first to third interquartile ranges (boxes); whiskers indicate 1.5× the interquartile ranges and dots are data points from individual animals. (C) Eyes assessed by live imaging (top) or opsin FISH (bottom) after 21 days of homeostatic RNAi to inhibit bmp and/or wnt5 and scored for lateral or medial ectopic eyes (arrows). For single-gene RNAi, dsRNA for the targeted gene was mixed with an equal amount of control dsRNA so that the total amounts of each targeted dsRNA delivered were equal between single- and double-RNAi conditions. 100% of bmp(RNAi) animals had ectopic medial eyes and 92% wnt5(RNAi) animals had ectopic lateral eyes. By contrast, 100% of bmp4;wnt5(RNAi) animals had at least two lateral ectopic eyes, and of these 38% also formed a single medial ectopic eye while 62% only formed ectopic lateral eyes (shown). Therefore, inhibition of wnt5 masks the bmp4(RNAi) ML phenotype. (D) Model of bmp4 establishing DV polarity, influencing AP regulation through wnt1, and controlling ML patterning through wnt5.

We next considered how bmp4 might interact with lateral regulatory factor wnt5. We first used the lateral epidermal marker laminB to confirm prior results that bmp4 inhibition generated ectopic lateral tissue (Fig. S3B) (32). We then examined a possible regulatory relationship between bmp4 and the lateral determinant wnt5. Following 28 days of bmp4 RNAi, expression of wnt5 significantly expanded to occupy distant medial territories on the dorsal side (Fig. 4B), and more weakly expanded wnt5 expression on the ventral side (Fig. S3C). To test whether bmp4 and wnt5 undergo reciprocal negative regulation, we inhibited wnt5 for 21 days, then stained for bmp4. Inhibition of wnt5 did not cause an apparent increase or decrease of bmp4 expression under these conditions (Fig. S4). Together, these experiments demonstrate that bmp4 antagonizes wnt5 expression, promotes medial identity and suppresses lateral identity.

To determine whether bmp4 functionally controls ML identity in part through regulation of wnt5, we conducted epistasis tests using eye placement as a readout. bmp4 RNAi causes the formation of ectopic medial eyes, whereas wnt5 RNAi produces an opposite defect of the formation of ectopic lateral eyes (6, 7, 10). To test for interactions between bmp4 and wnt5, we homeostatically inhibited these genes individually or together for 21 days, examined animals visually, and stained them with an opsin riboprobe to label photoreceptor neurons (Fig. 4C). Control animals had no ectopic eyes (13/13 animals), while 100% of bmp4(RNAi) animals (10/10 animals) had ectopic medial eyes, and 92% of wnt5(RNAi) animals (11/12 animals) had lateral eyes. In bmp4;wnt5(RNAi) animals, however, 100% of animals (13/13 animals) had at least two lateral ectopic eyes. Of these animals, 38% (5/13 animals) also had a single medial ectopic eye, while no animals displayed the bmp4(RNAi) phenotype of only medial ectopic eyes. Therefore, wnt5 likely does not operate exclusively upstream of bmp4, because double-RNAi animals displayed the wnt5(RNAi) phenotype. Additionally, the two factors likely do not operate fully independently because wnt5 co-inhibition reduced the penetrance of the bmp4(RNAi) phenotype (p=0.0027, 2-tailed Fisher's exact test). Instead, taken together with the findings that bmp4 RNAi causes expansion of wnt5 expression, these results indicate bmp4 can act upstream to limit wnt5 in order to regulate ML identity.

Discussion

Together, these experiments identify upstream roles for bmp4 in patterning multiple body axes in planarians. BMP regulation not only establishes DV polarity but additionally influences both posterior identity through regulation of wnt1 and also ML polarity through the suppression of wnt5 and activation of slit. These results indicate that the signals governing perpendicular body axes (i.e., AP and DV axes) are not fully independent in adult pattern formation in planarians. We suggest that a regulatory logic in which the integration of information across axes may be important for robustness of patterning across long timescales in adulthood (Fig. 4D).

Our results clarify the relationships among the BMP, Wnt5, and Slit signals that participate in ML patterning in planarians. DV polarity is apparently normal in wnt5(RNAi) animals, suggesting this treatment does not strongly impact BMP-dependent patterning (Fig. S4)(28). Further, the bmp4;wnt5(RNAi) experiments presented here suggest wnt5 acts downstream of bmp4, which is supported by wnt5 expression expansion after bmp4(RNAi). These results argue strongly against a hypothetical model in which wnt5 acts exclusively upstream of bmp4. It has been previously demonstrated that BMP inhibits Wnt5 during ectoderm patterning in sea urchins (46) and BMP activity downregulates wnt5a to modulate convergence and extension in zebrafish development (47). Therefore, roles of BMP upstream of Wnt5 factors may be conserved. slit also likely acts downstream of bmp4, because bmp4 inhibition reduced slit expression. These results collectively argue that bmp4 acts at a high point in a hierarchy for ML patterning.

Our experiments also reveal interactions in which dorsal BMP restricts posteriorizing Wnt signals. These results are congruous with evidence of spatiotemporal coordination between the AP and DV axes in vertebrate development. In early mammalian development, a proximal BMP signal from trophectoderm activates Wnt3 asymmetrically in epiblast cells in order to establish the future AP axis (48). In early Xenopus development, BMP4 is required for the expression of posterior Wnt8 (49). The integration of BMP and Wnt signaling pathways occurs by Wnt8 preventing the conserved ability of GSK3 kinase to inhibit Smad1 activity through its phosphorylation and targeted proteasomal degradation, such that Wnt signals can positively enhance BMP signaling duration. This regulation contributes to a model in which AP positional information is specified by the duration of BMP signaling (50). Zebrafish development also involves coordination of AP and DV axis formation, with maternal Wnt signaling generating the organizer to repress bmp, and zygotic Wnt transcriptionally promoting the maintenance of BMP expression (51). Furthermore, BMP defines DV patterning in a temporal AP gradient from head to tail (52). By contrast, planarian Wnt/BMP integration involves signaling antagonism and operates at a transcriptional level and so likely occurs through a distinct mechanism. Uses for Wnt and BMP signals to pattern perpendicular body axes predate the bilaterians, with Cnidarians using Wnt signaling along the oral-aboral primary body axis and BMP to control the perpendicular directive axis (3, 12, 53, 54). In Nematostella, BMP and canonical Wnt signaling mutually antagonize to pattern endomesoderm (55). Our results suggest that interactions between BMP/Wnt signaling across axes may be a fundamental and ancient property enabling the integration of body axis information in three dimensions.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Model

Asexual Schmidtea mediteraanea animals (CIW4 strain) were kept in 1x Montjuic salts at 18-20°C. Animals were fed pureed calf liver. Animals were starved at least 7 days before the start of experiments.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

The FISH protocol used is based off previously published work (38). Animals were killed in 7.5% NAC in PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, and stored in methanol. They were rehydrated with methanol:PBSTx, bleached in 6% hydrogen peroxide in PBS, permeabilized with proteinase K, then prehybridized at 56°C. Hybridization occurred with digoxigenin or fluorescein labeled riboprobes at a 1:1000 concentration, which were synthesized using T7 RNA binding sites for antisense transcription. Animals were washed in a SSC concentration series at 56°C. Anti-digoxigenin-POD or anti-fluorescein-POD antibodies were in a solution of TNTx/ horse serum/Western blocking reagent at a concentration of 1:2000. Tyramide in TNTx was utilized to develop and amplify the antibody signal. For double FISH, the enzymatic activity of tyramide reactions was inhibited by sodium azide. Nuclei were stained using 1:1000 Hoescht in TNTx.

RNA interference (RNAi)

RNAi treatments were performed by dsRNA feeding with 80% liver and 5% food dye. dsRNA was synthesized as previously described (29). Animals were fed RNAi food every 2-3 days for the length of the experiment. For double RNAi, control dsRNA was mixed in with the single experimental dsRNA to ensure the same amount of overall dsRNA in feedings between double and single experimental conditions (Fig. 4C). For RNAi treatment without injury, animals were fixed 5 days after the last feeding. For a regeneration time course following injury, animals were cut 2 days after the last feeding and fixed at the indicated time.

Image Acquisition

Live animals were imaged with a Leica M210F dissecting microscope with a Leica DFC295 camera (Fig. 4C). Stained animals were imaged with a Leica DMI 8 confocal microscope (Fig. 1-4, S1-S4). FISH images are maximum projections from a z-stack. Adjustments to brightness and contrast were made using Adobe Photoshop or ImageJ.

Primer Design

Primers for dsRNA and riboprobes are listed in Table S1.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Body length and PCG measurements were taken using LAS X or FIJI on z-stack maximum projections of FISH images. For body length, animals were measured from their most anterior to most posterior tips. For PCG length, animals were measured from the tip of the anterior (Fig. 3B), tip of the posterior (Fig. 2, 3A, 3C, S2), or lateral edge (Fig. 4B) to end of the fluorescence stain. Cell counting was manually performed using maximum projections in LAS X (Fig. 1, S3). Statistical analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel. Plots were generated in BoxPlotR.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. wnt1 inhibits bmp4 expression in the posterior. FISH staining for bmp4 expression after 14 days of control or wnt1 RNAi. Inhibition of wnt1 results in elevated expression of bmp4 on the posterior midline of the animal (arrows). Bottom panels show enlargements. Scale bars are 150 μm. N = 5 animals.

Fig. S2. Reduction of wnt1 expression domain through AP regenerative rescaling is not influenced by bmp4 inhibition. (A) FISH to detect wnt1 expression in regenerating tail fragments at 0, 18, and 96 hours after amputations conducted after 14 days of either control or bmp4 RNAi. Arrows indicate anterior-most wnt1+ cell detected along the dorsal midline for each timepoint and condition. Top panels show control animals undergoing early expansion of the dorsal midline wnt1 domain by 18 hours of regeneration followed by rescaling to reduce the domain to the tip of the animal by 96 hours. Bottom panel shows wnt1 expression dynamics in bmp4 RNAi, in which midline wnt1 expression was anterior expanded at the time of injury (0 hours), remained expanded at 18 hours of regeneration, and then restricted posteriorly by 96 hours, similar to control RNAi conditions. Therefore, BMP pathway modulation is unlikely to be responsible for the normal restriction of wnt1 by 96 hours in regenerating tail fragments. Scale bars represent 150 μm. (B) Graph showing the quantification of the length of the wnt1 domain relative to length of tail fragment. ****p<0.0001 by 2-tailed t-test and n.s. indicates p>0.05; N ≥ 3 animals. Box plots shows median values (middle bars) and first to third interquartile ranges (boxes); whiskers indicate 1.5× the interquartile ranges and dots are data points from individual animals.

Fig. S3. bmp4 promotes midline identity and suppresses lateral identity. (A-C) FISH for dd23400, LaminB, and wnt5 following 28 days of control or bmp4 RNAi. Scale bars represent 300 μm. (A) Inhibition of bmp4 reduces dd23400 expression (arrows), particularly in the posterior. Right: Quantification of number of dd23400+ cells normalized to animal body length. **p<0.01 by unpaired 2-tailed t-test; N ≥ 6 animals. Box plots show median values (middle bars) and first to third interquartile ranges (boxes); whiskers indicate 1.5× the interquartile ranges and dots are data points from individual animals. (B) bmp4 RNAi causes ectopic medial expression of lateral marker laminB expression on the posterior midline (arrows). (C) Knockdown of bmp4 appears to elevate wnt5 expression less dramatically on the ventral side versus dorsal side. Right panels show enlargements of boxed regions.

Fig. S4. wnt5 inhibition does not detectably alter bmp4 expression. FISH staining for bmp4 after 21 days of control or wnt5 RNAi under homeostatic conditions. Inhibition of wnt5 does not cause detectable increases or decreases in bmp4 expression or distribution. Scale bars are 150 μm. N = 5 animals.

Table S1. Primer Sequences for dsRNA and riboprobes.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Petersen lab for critical comments and Dr. Erik Schad for reagents and concepts. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant NIGMS R01GM129339 (to C.P.P.), National Institutes of Health grant NIGMS R01GM130835 (to C.P.P.), Simons/SFARI (597491-RWC) pilot project grant (to C.P.P.). E.G.C was supported in part by the Northwestern University Graduate School Cluster in Biotechnology, Systems, and Synthetic Biology, which is affiliated with the Biotechnology Training Program, and Northwestern University biotechnology training grant.

Footnotes

Competing Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References

- 1.Petersen CP, Reddien PW. Wnt signaling and the polarity of the primary body axis. Cell. 2009;139(6):1056–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Robertis EM, Sasai Y. A common plan for dorsoventral patterning in Bilateria. Nature. 1996;380(6569):37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niehrs C. On growth and form: a Cartesian coordinate system of Wnt and BMP signaling specifies bilaterian body axes. Development. 2010;137(6):845–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth S, Neuman-Silberberg FS, Barcelo G, Schupbach T. cornichon and the EGF receptor signaling process are necessary for both anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral pattern formation in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;81(6):967–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossant J, Tam PP. Blastocyst lineage formation, early embryonic asymmetries and axis patterning in the mouse. Development. 2009;136(5):701–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molina MD, Saló E, Cebrià F. The BMP pathway is essential for re-specification and maintenance of the dorsoventral axis in regenerating and intact planarians. Dev Biol. 2007;311(1):79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurley KA, Rink JC, Sánchez Alvarado A. Beta-catenin defines head versus tail identity during planarian regeneration and homeostasis. Science. 2008;319(5861):323–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iglesias M, Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Saló E, Adell T. Silencing of Smed-betacatenin1 generates radial-like hypercephalized planarians. Development. 2008;135(7):1215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen CP, Reddien PW. Smed-betacatenin-1 is required for anteroposterior blastema polarity in planarian regeneration. Science. 2008;319(5861):327–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Kicza AM, Sanchez Alvarado A. BMP signaling regulates the dorsal planarian midline and is needed for asymmetric regeneration. Development. 2007;134(22):4043–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srivastava M, Mazza-Curll KL, van Wolfswinkel JC, Reddien PW. Whole-body acoel regeneration is controlled by Wnt and Bmp-Admp signaling. Curr Biol. 2014;24(10):1107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holstein TW. The role of cnidarian developmental biology in unraveling axis formation and Wnt signaling. Developmental biology. 2022;487:74–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy PC, Gungi A, Ubhe S, Pradhan SJ, Kolte A, Galande S. Molecular signature of an ancient organizer regulated by Wnt/β-catenin signalling during primary body axis patterning in Hydra. Communications Biology. 2019;2(1):434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fincher CT, Wurtzel O, de Hoog T, Kravarik KM, Reddien PW. Cell type transcriptome atlas for the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Science. 2018;360(6391):eaaq1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plass M, Solana J, Wolf FA, Ayoub S, Misios A, Glažar P, et al. Cell type atlas and lineage tree of a whole complex animal by single-cell transcriptomics. Science. 2018;360(6391). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wurtzel O, Oderberg IM, Reddien PW. Planarian Epidermal Stem Cells Respond to Positional Cues to Promote Cell-Type Diversity. Dev Cell. 2017;40(5):491–504.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lapan SW, Reddien PW. Transcriptome analysis of the planarian eye identifies ovo as a specific regulator of eye regeneration. Cell Rep. 2012;2(2):294–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adler CE, Seidel CW, McKinney SA, Sánchez Alvarado A. Selective amputation of the pharynx identifies a FoxA-dependent regeneration program in planaria. eLife. 2014;3:e02238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonar NA, Petersen CP. Integrin suppresses neurogenesis and regulates brain tissue assembly in planarian regeneration. Development. 2017;144(5):784–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seebeck F, März M, Meyer A-W, Reuter H, Vogg MC, Stehling M, et al. Integrins are required for tissue organization and restriction of neurogenesis in regenerating planarians. Development. 2017;144(5):795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abnave P, Aboukhatwa E, Kosaka N, Thompson J, Hill MA, Aboobaker AA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors control pluripotent adult stem cell migration in vivo in planarians. Development. 2017;144(19):3440–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guedelhoefer OCt, Sánchez Alvarado A. Amputation induces stem cell mobilization to sites of injury during planarian regeneration. Development. 2012;139(19):3510–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atabay KD, LoCascio SA, de Hoog T, Reddien PW. Self-organization and progenitor targeting generate stable patterns in planarian regeneration. Science. 2018;360(6387):404–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lander R, Petersen CP. Wnt, Ptk7, and FGFRL expression gradients control trunk positional identity in planarian regeneration. eLife. 2016;5:e12850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill EM, Petersen CP. Positional information specifies the site of organ regeneration and not tissue maintenance in planarians. eLife. 2018;7:e33680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witchley JN, Mayer M, Wagner DE, Owen JH, Reddien PW. Muscle cells provide instructions for planarian regeneration. Cell Rep. 2013;4(4):633–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen CP, Reddien PW. A wound-induced Wnt expression program controls planarian regeneration polarity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(40):17061–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurley KA, Elliott SA, Simakov O, Schmidt HA, Holstein TW, Sánchez Alvarado A. Expression of secreted Wnt pathway components reveals unexpected complexity of the planarian amputation response. Dev Biol. 2010;347(1):24–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersen CP, Reddien PW. Polarized notum activation at wounds inhibits Wnt function to promote planarian head regeneration. Science. 2011;332(6031):852–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sureda-Gómez M, Pascual-Carreras E, Adell T. Posterior Wnts Have Distinct Roles in Specification and Patterning of the Planarian Posterior Region. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(11):26543–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adell T, Salò E, Boutros M, Bartscherer K. Smed-Evi/Wntless is required for beta-catenin-dependent and -independent processes during planarian regeneration. Development. 2009;136(6):905–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gavino MA, Reddien PW. A Bmp/Admp regulatory circuit controls maintenance and regeneration of dorsal-ventral polarity in planarians. Current biology : CB. 2011;21(4):294–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molina MD, Neto A, Maeso I, Gómez-Skarmeta JL, Saló E, Cebrià F. Noggin and noggin-like genes control dorsoventral axis regeneration in planarians. Curr Biol. 2011;21(4):300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orii H, Watanabe K. Bone morphogenetic protein is required for dorso-ventral patterning in the planarian Dugesia japonica. Dev Growth Differ. 2007;49(4):345–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.González-Sastre A, Molina MD, Saló E. Inhibitory Smads and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) modulate anterior photoreceptor cell number during planarian eye regeneration. Int J Dev Biol. 2012;56(1-3):155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cebrià F, Guo T, Jopek J, Newmark PA. Regeneration and maintenance of the planarian midline is regulated by a slit orthologue. Dev Biol. 2007;307(2):394–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orii HK K; Agata K; Watanabe K. Molecular Cloning of the Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) Gene from the Planarian Dugesia japonica. Zoological science. 1998;15(6):6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schad EG, Petersen CP. STRIPAK Limits Stem Cell Differentiation of a WNT Signaling Center to Control Planarian Axis Scaling. Curr Biol. 2020;30(2):254–63.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scimone ML, Cloutier JK, Maybrun CL, Reddien PW. The planarian wound epidermis gene equinox is required for blastema formation in regeneration. Nature Communications. 2022;13(1):2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian Q, Sun Y, Gao T, Li J, Hao Z, Fang H, et al. TBX2/3 is required for regeneration of dorsal-ventral and medial-lateral polarity in planarians. J Cell Biochem. 2021;122(7):731–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scimone ML, Cote LE, Rogers T, Reddien PW. Two FGFRL-Wnt circuits organize the planarian anteroposterior axis. eLife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stückemann T, Cleland JP, Werner S, Thi-Kim Vu H, Bayersdorf R, Liu SY, et al. Antagonistic Self-Organizing Patterning Systems Control Maintenance and Regeneration of the Anteroposterior Axis in Planarians. Dev Cell. 2017;40(3):248–63.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tewari AG, Owen JH, Petersen CP, Wagner DE, Reddien PW. A small set of conserved genes, including sp5 and Hox, are activated by Wnt signaling in the posterior of planarians and acoels. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(10):e1008401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reuter H, Marz M, Vogg MC, Eccles D, Grifol-Boldu L, Wehner D, et al. Beta-catenin-dependent control of positional information along the AP body axis in planarians involves a teashirt family member. Cell Rep. 2015;10(2):253–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oderberg IM, Li DJ, Scimone ML, Gaviño MA, Reddien PW. Landmarks in Existing Tissue at Wounds Are Utilized to Generate Pattern in Regenerating Tissue. Curr Biol. 2017;27(5):733–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McIntyre DC, Seay NW, Croce JC, McClay DR. Short-range Wnt5 signaling initiates specification of sea urchin posterior ectoderm. Development. 2013;140(24):4881–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myers DC, Sepich DS, Solnica-Krezel L. Bmp activity gradient regulates convergent extension during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev Biol. 2002;243(1):81–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurek D, Neagu A, Tastemel M, Tüysüz N, Lehmann J, van de Werken HJG, et al. Endogenous WNT signals mediate BMP-induced and spontaneous differentiation of epiblast stem cells and human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4(1):114–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoppler S, Moon RT. BMP-2/−4 and Wnt-8 cooperatively pattern the Xenopus mesoderm. Mech Dev. 1998;71(1-2):119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fuentealba LC, Eivers E, Ikeda A, Hurtado C, Kuroda H, Pera EM, et al. Integrating patterning signals: Wnt/GSK3 regulates the duration of the BMP/Smad1 signal. Cell. 2007;131(5):980–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuazon FB, Mullins MC. Temporally coordinated signals progressively pattern the anteroposterior and dorsoventral body axes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;42:118–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tucker JA, Mintzer KA, Mullins MC. The BMP signaling gradient patterns dorsoventral tissues in a temporally progressive manner along the anteroposterior axis. Dev Cell. 2008;14(1):108–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rentzsch F, Anton R, Saina M, Hammerschmidt M, Holstein TW, Technau U. Asymmetric expression of the BMP antagonists chordin and gremlin in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis: implications for the evolution of axial patterning. Dev Biol. 2006;296(2):375–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saina M, Genikhovich G, Renfer E, Technau U. BMPs and Chordin regulate patterning of the directive axis in a sea anemone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(44):18592–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wijesena N, Simmons DK, Martindale MQ. Antagonistic BMP-cWNT signaling in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis reveals insight into the evolution of mesoderm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(28):E5608–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. wnt1 inhibits bmp4 expression in the posterior. FISH staining for bmp4 expression after 14 days of control or wnt1 RNAi. Inhibition of wnt1 results in elevated expression of bmp4 on the posterior midline of the animal (arrows). Bottom panels show enlargements. Scale bars are 150 μm. N = 5 animals.

Fig. S2. Reduction of wnt1 expression domain through AP regenerative rescaling is not influenced by bmp4 inhibition. (A) FISH to detect wnt1 expression in regenerating tail fragments at 0, 18, and 96 hours after amputations conducted after 14 days of either control or bmp4 RNAi. Arrows indicate anterior-most wnt1+ cell detected along the dorsal midline for each timepoint and condition. Top panels show control animals undergoing early expansion of the dorsal midline wnt1 domain by 18 hours of regeneration followed by rescaling to reduce the domain to the tip of the animal by 96 hours. Bottom panel shows wnt1 expression dynamics in bmp4 RNAi, in which midline wnt1 expression was anterior expanded at the time of injury (0 hours), remained expanded at 18 hours of regeneration, and then restricted posteriorly by 96 hours, similar to control RNAi conditions. Therefore, BMP pathway modulation is unlikely to be responsible for the normal restriction of wnt1 by 96 hours in regenerating tail fragments. Scale bars represent 150 μm. (B) Graph showing the quantification of the length of the wnt1 domain relative to length of tail fragment. ****p<0.0001 by 2-tailed t-test and n.s. indicates p>0.05; N ≥ 3 animals. Box plots shows median values (middle bars) and first to third interquartile ranges (boxes); whiskers indicate 1.5× the interquartile ranges and dots are data points from individual animals.

Fig. S3. bmp4 promotes midline identity and suppresses lateral identity. (A-C) FISH for dd23400, LaminB, and wnt5 following 28 days of control or bmp4 RNAi. Scale bars represent 300 μm. (A) Inhibition of bmp4 reduces dd23400 expression (arrows), particularly in the posterior. Right: Quantification of number of dd23400+ cells normalized to animal body length. **p<0.01 by unpaired 2-tailed t-test; N ≥ 6 animals. Box plots show median values (middle bars) and first to third interquartile ranges (boxes); whiskers indicate 1.5× the interquartile ranges and dots are data points from individual animals. (B) bmp4 RNAi causes ectopic medial expression of lateral marker laminB expression on the posterior midline (arrows). (C) Knockdown of bmp4 appears to elevate wnt5 expression less dramatically on the ventral side versus dorsal side. Right panels show enlargements of boxed regions.

Fig. S4. wnt5 inhibition does not detectably alter bmp4 expression. FISH staining for bmp4 after 21 days of control or wnt5 RNAi under homeostatic conditions. Inhibition of wnt5 does not cause detectable increases or decreases in bmp4 expression or distribution. Scale bars are 150 μm. N = 5 animals.

Table S1. Primer Sequences for dsRNA and riboprobes.