Abstract

Transposition plays a role in the epidemiology and pathogenesis of Neisseria meningitidis. Insertion sequences are involved in reversible capsulation and insertional inactivation of virulence genes encoding outer membrane proteins. In this study, we have investigated and identified one way in which transposon IS1106 controls its own activity. We have characterized a naturally occurring protein (Tip) that inhibits the transposase. The inhibitor protein is a truncated version of the IS1106 transposase lacking the NH2-terminal DNA binding sequence, and it regulates transposition by competing with the transposase for binding to the outside ends of IS1106, as shown by gel shift and in vitro transposition assays. IS1106Tip mRNA is variably expressed among serogroup B meningococcal clinical isolates, and it is absent in most collection strains belonging to hypervirulent lineages.

Many studies have pointed out the importance of mobile genetic elements in microbial pathogenesis and adaptation to changing environmental conditions. Virulence genes of pathogenic bacteria, which code for toxins, adhesins, invasins, capsules, pili, resistance determinants, or other virulence factors, may be located on transmissible genetic elements such as transposons, plasmids, or bacteriophages (16, 50). Insertion sequence (IS) elements are known to be involved in microevolution of bacterial genomes by several mechanisms (1, 32). (i) In the chromosomes of both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, virulence genes are often clustered in “virulence blocks” or “pathogenicity islands,” surrounded by IS elements that promote their transposition and lead to changes in virulence in the course of evolution. Pathogenicity islands are invariably found in pathogenic strains of a given species but are either absent or rarely present in nonpathogenic variants of the same species (12, 20, 21, 23, 30, 33, 34). (ii) In addition, two copies of certain IS elements flanking a DNA segment are able to act in concert, mobilizing the intervening region. (iii) Programmed insertion and excision of IS elements and of invertible DNA sequences may control the expression of several virulence factors by a mechanism of phase variation (24, 58). (iv) “Jumping” of DNA sequences (transposition) and subsequent recombination events may also cause gene activation (5) and antigenic variation of virulence factors, leading to the emergence of novel pathogenic variants (48). (v) IS-related DNA rearrangements do occur in resting bacterial cultures and confer plasticity on the genome under conditions of nutritional deprivation, thereby playing an adaptive role (1, 3, 18, 35, 36).

With the development of studies of the mechanisms of bacterial pathogenesis and the advent of whole-genome sequencing technologies in recent years, the finding of association between IS elements and pathogenic and virulence functions has become increasingly evident. Such associations have been observed in a variety of animal pathogens (6, 9, 14, 17, 31, 52).

Whole-genome sequence analysis and subtractive hybridization procedures have led to the identification of putative islands of horizontally transferred DNA into the genomes of serogroup B and serogroup A meningococci (42, 55). Several of these regions encode proteins that are specific to the pathogenic Neisseria species and may have a role in virulence. These regions do not have the classical characteristics of pathogenicity islands. Several, however, have a particularly low G+C content and are associated with transposase and integrase genes, suggesting that at some time in the genetic history of these species, the regions were the results of recombination events with DNAs from other species. One of these regions in a serogroup A strain, characterized by a significantly low G+C content and containing open reading frames (ORFs) with no homology to genes in databases, is flanked by several copies of IS1106 and a copy of IS50 (42).

Transposition plays a role in the epidemiology and pathogenesis of Neisseria meningitidis. IS1301 is involved in reversible capsulation by insertion into and excision from the siaA gene locus in serogroup B meningococci (24). This transposable element is also responsible for insertional inactivation of the porA gene encoding the class 1 outer membrane protein, which is considered to function as a porin and invasin (57) in several serogroup B and C meningococcal isolates (38). In addition, analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the chromosomal region downstream of the porA gene has revealed the presence of a rearranged copy of the IS1106 element in carrier strains/isolates but not in invasive meningococcal strains/isolates of serogroup B, type 15, subtype 16 (B15:P1.16) (26).

IS1106 is an IS present in multiple copies in all of the meningococcal strains so far examined (39, 40) belonging to the IS5 group of the IS4 family of transposable elements (46, 26, 32). It was the first IS to be characterized in N. meningitidis and has been used as a DNA probe in phylogenetic and epidemiological analyses (25, 39) and to develop rapid, specific, and sensitive PCR-based tests for the diagnosis of meningococcal disease (40).

In this study, we have investigated the regulation of transposase activity of the element IS1106 in clinical isolates of N. meningitidis and characterized a naturally occurring inhibitor protein (IS1106Tip) of the transposase of IS1106 (IS1106T) by using biochemical and genetic approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The meningococcal strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Invasive strains/isolates were derived from a collection of strains isolated during outbreaks of epidemic disease that have occurred in different places in Italy and France during the last 20 years. The serotypes and subserotypes of these strains are shown in Table 1. A total of 24 carrier strains/isolates were enrolled in this study. These strains were sampled from the nasopharynges of different healthy subjects at the time of their military enlistment in the course of a routine screening program for the surveillance of meningococcal disease. The carrier strains/isolates used in this study were sampled in different geographical areas in Italy and France. Two strains, BL9513 and BF9513, were isolated, respectively, from the cerebrospinal fluid and the nasopharynx of a single sick subject in France. All meningococcal strains were cultured on chocolate agar (Becton-Dickinson) or on GC agar or broth (Difco) supplemented with 1% (vol/vol) Polyvitox (Bio-Merieux) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Antibiotics were purchased from Sigma and used at the following concentrations: erythromycin, 7 μg ml−1; rifampin, 36 μg ml−1.

TABLE 1.

Meningococcal strains used in this study and their characteristics

| Strain | Serogroup and/or serotypea | Lineageb | IS1106Tip mRNAc | Clinical specimen(s)d | Sourcee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BF2 | B | ET-37 | + | NP | i |

| BF3 | B | ET-37 | + | NP | i |

| BF9 | B | Other | − | NP | i |

| BF13 | B | Other | + | NP | i |

| BL847 | B:14:P1.12 | Lineage 3 | − | CSF | ii |

| BL851 | B:4:P1.13 | Lineage 3 | − | CSF | ii |

| BL857 | B:21:P1.7,16 | Other | − | CSF | ii |

| BL858 | B:15,21:P1.15 | Other | − | CSF | ii |

| BL859 | B:4:P1.13 | Lineage 3 | − | CSF | ii |

| BS843 | B:4:P1.13 | Lineage 3 | − | BL | ii |

| BS845 | B:4:P1.13 | Lineage 3 | − | BL | ii |

| BS849 | B:4:P1.13 | Lineage 3 | − | BL | ii |

| BL855 | B | ET-37 | + | CSF | ii |

| B1940 | B:NT:P1.3,6,15 | Other | − | CSF | iii |

| BL9513 | B:4:P1.4 | Lineage 3 | − | CSF, BL | iv |

| BL892 | B:4:P1.4 | Lineage 3 | − | CSF | iv |

| BL942 | B:1:NST | Lineage 3 | ± | CSF | iv |

| BL911 | B:NT:P1.9 | Other | − | CSF | iv |

| BL915 | B:NT:P1.5 | Other | − | CSF | iv |

| BL951 | B:NT:P1.1 | Lineage 3 | − | CSF | iv |

| BL899 | B:4:P1.2,5 | ET-5 | − | CSF | iv |

| BL932 | B:4:P1.1 | Other | − | CSF | iv |

| BL937 | B:4:NST | ET-5 | − | CSF | iv |

| BL947 | B:1:NST | Other | − | CSF | iv |

| BL897 | B | Other | ± | CSF | iv |

| BF10 | B | Other | + | NP | v |

| BF17 | B | Other | − | NP | v |

| BF18 | B | Other | + | NP | v |

| BF21 | B | Other | + | NP | v |

| BF65 | B | Other | + | NP | v |

| BF16 | B | Other | − | NP | v |

| BF23 | B | ET-5 | − | NP | v |

| BF40 | B | ET-37 | + | NP | v |

| BF52 | B | ET-37 | + | NP | v |

| BF8960 | B | Other | − | NP | vi |

| BF8961 | B | Other | + | NP | vi |

| BF8964 | B | Other | ± | NP | vi |

| BF8969 | B | Other | ± | NP | vi |

| BF9216 | B | Other | − | NP | vi |

| BF5425 | B | Other | + | NP | vi |

| BF32B | B | Lineage 3 | NA | NP | vii |

| BF37B | B | Other | NA | NP | vii |

| BF43B | B | Other | NA | NP | vii |

| BF6L | B | Other | NA | NP | vii |

| BF8L | B | Other | NA | NP | vii |

| BF57L | B | Other | NA | NP | vii |

| 205900 | A | IV-1 | − | CSF, BL | viii |

| 93/4286 | C | ET-37 | + | CSF, BL | viii |

| NGP165 | B | ET-37 | + | CSF, BL | viii |

| BZ169 | B | ET-5 | − | CSF, BL | viii |

| H44/76 | B | ET-5 | − | CSF, BL | viii |

| MC58 | B | ET-5 | − | CSF, BL | viii |

| NGF26 | B | Other | − | CSF, BL | viii |

| 1000 | B | Other | − | CSF, BL | viii |

| NGE31 | B | Other | + | CSF, BL | viii |

| NGH15 | B | Other | − | CSF, BL | viii |

| ZF15 | Z | Other | + | NP | v |

| XL929 | X | Other | − | CSF, BL | iv |

| XF47A | X | Other | NA | NP | v |

| YL896 | Y | Other | − | CSF | iv |

| CF5C | C | Other | − | NP | v |

NST, not serotypeable.

Assignment of isolates to hypervirulent lineages was done as detailed in Materials and Methods. Other, not belonging to lineage 3, ET-5, or ET-37 complex, IV-1 cluster.

IS1106Tip mRNAs were detected by S1 nuclease protection experiments. +, presence of specific transcripts; −, absence of detectable transcripts; ±, barely detectable transcripts; NA, not analyzed.

NP, nasopharynx; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; BL, blood.

i, II Policlinico, Università di Napoli, Naples, Italy; ii, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy; iii, Bayerische Julius-Maximilians Universität, Würzburg, Germany; iv, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France; v, Hôpital d'Instruction des Armée, Brest Naval, France; vi, Institut de Médecine Tropicale du Service de Santé dès Armées, Marseille Armées, France; vii, Laboratory of Microbiology, Università di Lecce, Lecce, Italy; viii, IRIS, Chiron S.p.A, Siena, Italy.

Escherichia coli strain DH5α [F− Φ80d lacZΔM15 endA1 recA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 λ− gyrA96 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169] was used in cloning procedures. Strain BL21 λDE3 (F− ompT rB− mB−) was used to overexpress recombinant proteins (53). E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth/agar. When needed, ampicillin was added to a final concentration of 50 μg ml−1.

Transformation of meningococci.

Transformations were performed as previously described (19) by using 500 ng of chromosomal DNA extracted from rifampin-resistant derivatives of strains BL847 and BF52 (Table 1). A recipient strain was BF52. Transformants were selected on GC agar base supplemented with rifampin (36 μg ml−1) or erythromycin (7 μg ml−1).

Plasmids and cloning procedures.

To obtain plasmid pUCIS1106::ermC′, a 1,245-bp-long PCR-derived EcoRV fragment spanning an entire IS1106 element and flanking direct repeats (GGTC) was cloned into the HincII site of pUC19. The oligonucleotides used to amplify the IS1106 DNA sequence were 5′-TAAGATATCGTCGACGGTCGAGACCTTTGCAAAATTCCCCAAAATC-3′ and 5′ - T TAGATATCG TCGACGACCGAGACC T T TGCAAAATTCCT T TCCC TC-3′(the EcoRV sites are underlined). The template DNA was derived from strain BL859. The resulting plasmid, pUC1106, was linearized at the unique ClaI site within the IS1106T gene, and a 1,573-bp ClaI-AccI fragment containing the ermC′ gene was inserted.

To construct plasmids pET1106T and pET1106Tip, genomic regions containing the entire or 5′-end-truncated transposase were amplified, respectively, by using oligonucleotides 5′-TTAGGGGATTTCATATGAGCACCTTCTTCCGGCAAACCGC-3′ and 5′-CTTTCCCGGATCCCAGCCGAAACCCAAACACAGG-3′ (for IS1106T) or 5′-CCTTGTCCTGACATATGTTAATCCACTATACCTCCGCCAATG-3′ and 5′-CTTTCCCGGATCCCAGCCGAAACCCAAACACAGG-3′ (for IS1106Tip) (the underlined sequences are CATATG for NdeI sites and GGATCC for BamHI sites). The template DNAs were derived from strain BL859 (for IS1106T) and BF18 (for IS1106Tip). The PCR products of 1,128 and 518 bp, respectively, were restricted with NdeI and BamHI and cloned into the NdeI-BamHI sites of pET15b (provided by Novagen). pT71106Tip was obtained by cloning the 518-bp PCR product into the NdeI-BamHI sites of pT7-7 (54).

Plasmid pUH1106Tip was constructed by cloning a 540-bp-long, PCR-derived BamHI-XbaI fragment spanning the IS1106Tip gene into the polylinker of plasmid pUH1I (47). The oligonucleotides used to amplify the IS1106 DNA sequence were 5′-TAAGATGGATCCCTGCGGCTTCGTCGCCTTGTC-3′ and 5′-CTTTCCCTCTAGACAGCCGAAACCCAAACACAGG-3′ (the underlined sequences are GGATCC for BamHI sites and TCTAGA for XbaI sites). The template DNA was derived from strain BF18.

The genomic region encompassing the truncated IS1106 element shown in Fig. 3 was amplified from meningococcal strains by using oligonucleotides 5′-ATGGACGAAATCGAGGCAGCCG-3′ and 5′-TTCCCGCGAACGCGGGAATC-3′ as primers.

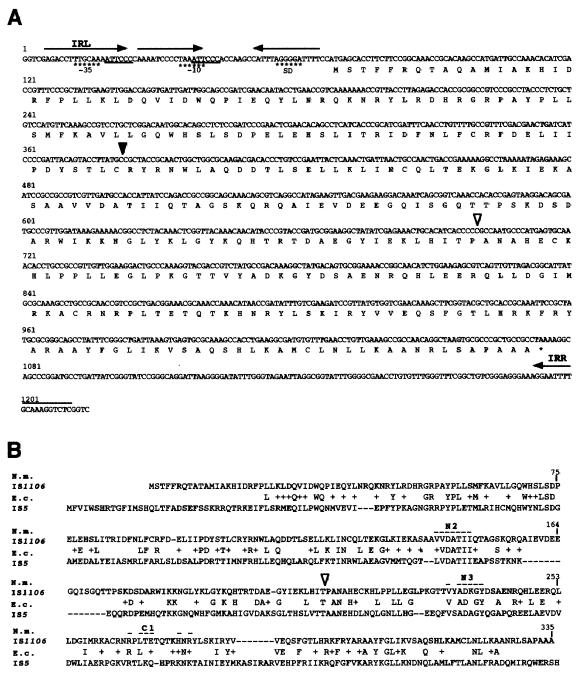

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence, deduced amino acid sequence, and structural features of the genomic region containing the transcriptionally active IS1106Tip gene. (A) Physical and genetic map of the genomic region containing the IS1106Tip gene. The IS1106Tip gene is located downstream of an IS1016-like element, which is preceded by the rho gene. The element is truncated at the 5′ end and is located immediately downstream from a neisserial SRE. Two copies of neisserial repetitive sequence RS3 are arranged in tandem downstream from the truncated element. The bent arrow indicates the transcription start point of the IS1106Tip mRNA. (B) Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the IS1106Tip gene. Arrows indicate IRs of the SRE (SRE-IRL and -IRR) and of IS1106 (IS1106-IRR). RS3 sequences are underlined. Bent arrows indicate the 5′ ends of the IS1106Tip mRNA. Asterisks mark the positions of a putative gearbox promoter sequence (5′-CACCAAGT-3′). Four nucleotide substitutions (indicated above the nucleotide sequence of BF18) were found in invasive strains/isolates BL859 and BL892 and map 12, 24, 82, and 86 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start site. Amino acid residues that are different from the deduced sequence of IS1106T (Fig. 1A) are underlined.

DNA procedures.

High-molecular-weight genomic DNAs from the different N. meningitidis strains were prepared as previously described (7). DNA fragments were isolated through acrylamide slab gels and recovered by electroelution as previously described (49).

The IS1106T-specific probe used in the Northern blot and S1 nuclease mapping experiments shown in Fig. 2 was obtained by PCR using the genomic DNA derived from strain BS849 as the template. The oligonucleotides used as primers (5′-ATGAGCACCTTCTTCCGGCAAACCGC-3′ and 5′-AGACAGCCGAAACCCAAACACAGG-3′) were designed to amplify a region of 1,126 bp on the basis of the nucleotide sequence of IS1106 shown in Fig. 1 (from nucleotide 68 to nucleotide 1194). The IS1106-specific probe used in the S1 mapping experiment shown in Fig. 5 was obtained with oligonucleotides 5′-ACAATGATGATTTCTTTGAACTGATGCGCG-3′ and 5′-ACATCGCCTTCAGGTGGCTTTGCGCACTCAC-3′ (from nucleotide 456 to nucleotide 482 of Fig. 4B) and genomic DNA derived from strain BF18 used as a template. The amplification reactions consisted of 30 cycles including 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 55°C, and 1 to 2 min of extension at 72°C. They were carried out in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA Thermal Cycler 480. 5′-end labeling was performed with the T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci mmol−1). In Northern blot and S1 mapping experiments, the probes were labeled only at the strand complementary to the expected transcripts.

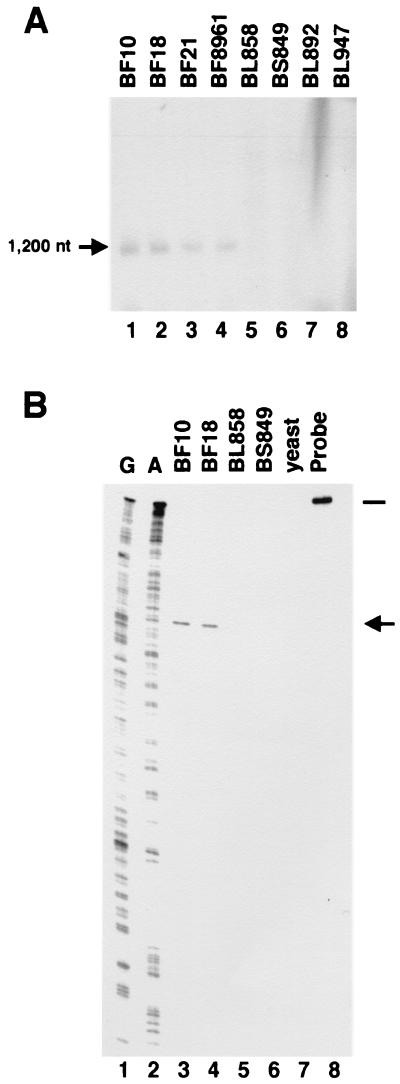

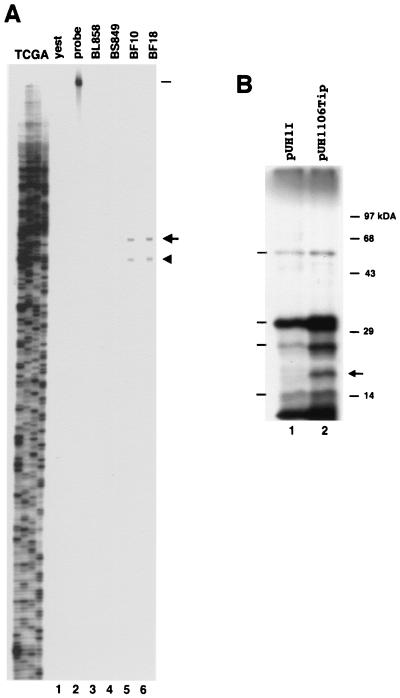

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the IS1106-specific transcript. (A) Northern blot analysis. Total RNAs (10 μg) from carrier strains/isolates BF10, BF18, BF21, and BF8961 (lanes 1 to 4) and from invasive strains/isolates BL858, BS849, BL892, and BL947 (lanes 5 to-8) were hybridized to a 5′-end-labeled 1,126-bp DNA fragment spanning the entire coding region of IS1106T (Fig. 1A and Materials and Methods). Only the strand complementary to the RNA was labeled. Arrows indicate the IS1106-specific transcript and its approximate size deduced on the basis of the relative migration of the rRNAs. nt, nucleotides. (B) S1 nuclease mapping analysis. A 5′-end-labeled DNA fragment spanning the entire coding region of IS1106T (Fig. 1A) was used as a probe. The probe (lane 8) was hybridized to total RNA (10 μg) extracted from carrier strains/isolates BF10 and BF18 (lanes 3 and 4), from invasive strains/isolates BL858 and BS849 (panel B, lanes 5 and 6), or from yeast (lane 7). After treatment with S1 nuclease, the reaction products were resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide-urea denaturing gel. The sizes of the protected hybrids (arrows) were determined by running in parallel a sequencing reaction ladder (G and A, lanes 1 and 2) of the same DNA fragment used as a probe. The bar indicates the relative migration of the probe.

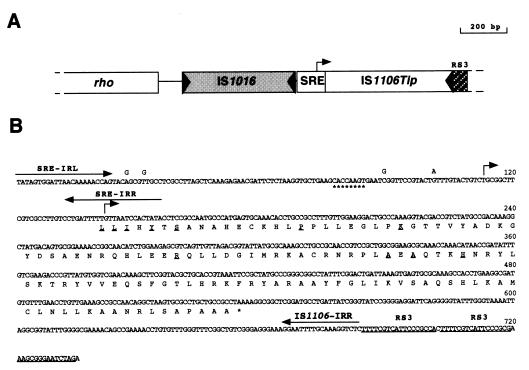

FIG. 1.

Structure and nucleotide sequence of N. meningitidis IS1106. (A) Nucleotide sequence of IS1106 and deduced amino acid sequence of the putative transposase (IS1106T) gene. IS1106 has a length of 1,207 bp and is flanked by 19-bp-long IRs (IRL and IRR, arrows). Four-base-pair direct repeats (GGTC) border the ends of the IS. Amino acids corresponding to the IS1106T ORF are indicated in uppercase letters below the nucleotide sequence. Several control elements are also shown: (i) a14-bp-long perfect IR located 2 bp downstream from IRL (arrows), (ii) a repeated motif resembling part of the core sequence of the neisserial RS3 repeat (underlined sequences), and (iii) putative −10 and −35 promoter and Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequences (asterisks). The nucleotide sequence downstream from the black arrowhead is also part of the rearranged element previously described (26). The sequence downstream from the open arrowhead is shared by IS1106Tip (Fig. 3B). (B) The deduced amino acid sequence of the putative IS1106T of N. meningitidis (N.m.) is aligned with the amino acid sequence of the 5A transposase protein of E. coli (E.c.) IS5. Plus signs indicate synonymous substitutions. The sequence downstream from the open arrowhead is shared by IS1106Tip (Fig. 3B). The overlined amino acids grouped in the N2, N3, and C1 regions are part of the DDE motif, the amino acid triad intimately involved in catalysis (32).

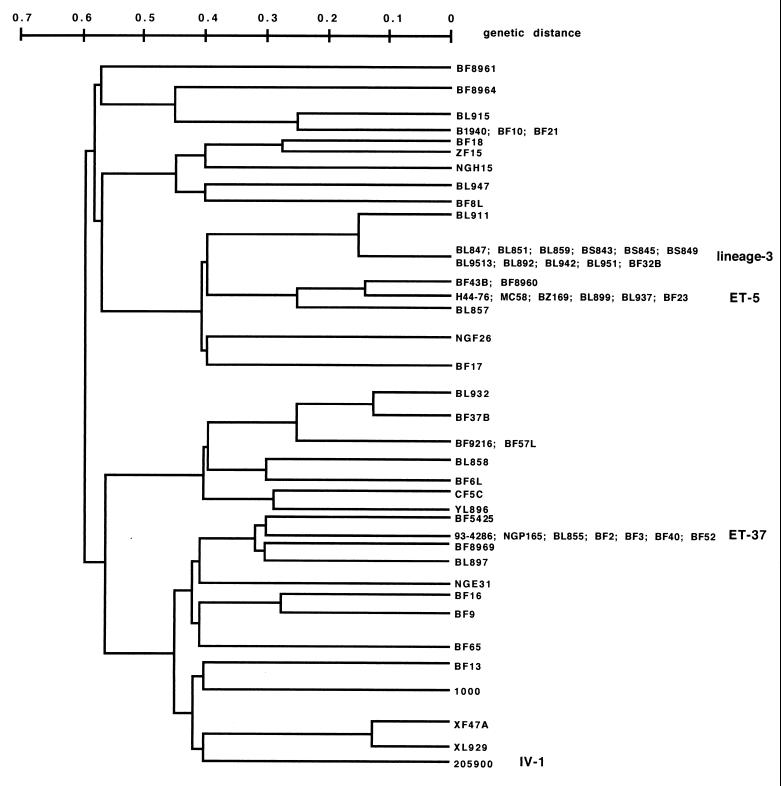

FIG. 5.

Dendrogram showing the genetic relatedness between meningococcal strains. The genetic distance between the meningococcal isolates was determined by comparing RFLP patterns in eight housekeeping genes and using collection strains as a reference as detailed in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 4.

Transcript mapping and translation of IS1106Tip. (A) S1 nuclease mapping of the putative start site(s) of the IS1106Tip transcript. Total RNAs (10 μg) from carrier strains/isolates BF10 and BF18 (lanes 5 and 6), from invasive strains/isolates BL858 and BS849 (lanes 3 and 4) or from yeast (lane 1) were hybridized to a 1,255-bp DNA fragment spanning the entire genomic region of IS1106Tip (Fig. 3 and Materials and Methods) that was labeled at the 5′ end of the strand complementary to the RNA (lane 2). The sizes of the protected hybrids (340 nucleotides [arrow] and 369 nucleotides [arrowhead]) were determined by running in parallel a sequencing reaction ladder (TCGA) of the same DNA fragment used as a probe. The bar indicates the relative migration of the probe. (B) In vitro transcription-translation of IS1106Tip gene. Plasmid pUH1I (lane 1) and derivative pUH1106Tip harboring the IS1106Tip gene (lane 2) were transcribed in vitro and translated by using an S30 extract derived from meningococcal strain BF18. The translation products were analyzed on an SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel. The bars on the left indicate vector-specific peptides. The arrow on the right marks the position of a specific translation product of about 16,000 Da produced by pUH1106Tip. The relative migration of molecular size markers is shown on the right.

The nucleotide sequence of the wild-type IS1106 element (Fig. 1A) was determined by sequencing of a 1,227-bp PCR product obtained by amplifying a genomic region(s) of serogroup B strain BL859 (Table 1) using two oligonucleotides corresponding to the IS1106 arms as primers. The putative arms of the element were determined by analysis of the available genomic sequence of N. meningitidis serogroup A strain Z2491 (Sanger Centre database) using a National Center for Biotechnology Information sequence similarity search tool.

The nucleotide sequence of the genomic region containing the IS1106Tip gene was determined by sequencing of PCR products obtained by using appropriate oligonucleotides as primers. The oligonucleotides were designed on the basis of the available sequences of N. meningitidis serogroup A strain Z2491, in which a region containing a 5′-truncated element was identified by using a National Center for Biotechnology Information sequence similarity search tool.

DNA sequencing reactions were carried out by the dideoxy-chain termination procedure using the T7 SequencingTM kit (Pharmacia Biotech) or the TAQence cycle sequencing kit from USB (distributed by Amersham Life Science) in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturers.

Processing of the DNA sequences was performed with the software GeneJockey Sequence Processor (published and distributed by Biosoft).

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) typing of meningococcal strains.

The genetic distances between the meningococcal isolates were determined by comparing RFLP patterns in eight housekeeping genes and using collection strains as a reference. Assignment of the different isolates to hypervirulent lineages was done by comparing the RFLP patterns to those of the reference strains (BL9513 [lineage 3]; 205900 [IV-1 cluster]; 93/4286 and NGP165 [ET-37 complex]; and BZ169, H44/76, and MC58 [ET-5 complex]).

Southern blotting was used to detect polymorphism generated by the presence or absence of Sau3AI sites in the coding region of the genes recA, uvrA, uvrB, uvrC, uvrD, rep, leuS, and rho. The gene fragments were amplified from chromosomal DNA of strain BL859 by using PCR with the following primers: 5′-CCGAATCCTCCGGCAAAACCACCC-3′ and 5′-CCGATCTTCATCCGGATTTGGTTGATG-3′ (recA), 5′-GCTCGTGGTGGTAACAGGATTGTCGGG-3′ and 5′-CAAAAGGCGCAGATAGTCGTGGATTTC-3′ (uvrA), 5′-GAACATATCGAGCAGATGCGCCTTTCC-3′ and 5′-GCTCATTAAATCGTCGACTTGGGTGGC-3′ (uvrB), 5′-GCAAAGTCTTATACGTCGGCAAAGC-3′ and 5′-GGTGTGGCTGATGTCGAAGCATTC-3′ (uvrC), 5′-GTGCTGACCACGCGCATCGCATGGC-3′ and 5′-GTTGGTGTCTTGGAACTCGTCAACGAG-3′ (uvrD), 5′-TGCTCGTCCTTGCCGGTGCAGGCAGCG-3′ and 5′-CGCGGTGGAGCGGTAGTTTTGCTCCAG-3′ (rep), 5′-GAGCTGACTTTTGACGACAAAGGC-3′ and 5′-TTCGTCGACTGCCGGCCAGCCAGC-3′ (leuS), and 5′-TGCACGTCTCCGAATTACAAACCCTGC-3′ and 5′-CACGCTTCCTTCGATGGTGTCGCC-3′ (rho). The lengths of the PCR products were as follows: 400 bp (recA), 248 bp (uvrA), 955 bp (uvrB), 1,129 bp (uvrC), 561 bp (uvrD), 755 bp (rep), 611 bp (leuS), and 303 bp (rho). Southern blots were performed in accordance with standard procedures (49). For higher resolution, a large apparatus was used for agarose-gel electrophoresis and the DNAs from reference strains were always included in each run. Bands of the same size were assumed to be identical and therefore to correspond to the same allele. The genetic diversity (h) at a locus among isolates was calculated as follows: h = (1 − Σxi2)(n/n − 1), where xi is the frequency of the ith allele and n is the number of isolates. The h values for the loci were: 0.00 (recA), 0.83 (uvrA), 0.70 (uvrB), 0.82 (uvrC), 0.73 (uvrD), 0.64 (rep), 0.39 (leuS), and 0.66 (rho). The mean genetic diversity per locus was the arithmetic average of h values over all of the loci. The genetic distance (D) between pairs of isolates was calculated as the proportion of loci at which dissimilar alleles occurred, and a dendrogram was constructed from a matrix of allelic mismatches by the pair group cluster method with arithmetic averages. Data were normalized by a weighted coefficient, with the contribution of each locus to D being weighted by the reciprocal of the mean genetic diversity at the locus in the total sample being analyzed (37, 51).

RNA procedures.

Total bacterial RNA was extracted from logarithmically growing cells by the guanidine hydrochloride procedure previously described (7). Electrophoretic analysis was done by fractionating the total RNA on 1% agarose gels containing formaldehyde (49). RNA transfer to Hybond (Amersham) membranes and hybridization with 32P-labeled fragments were done in accordance with the standard procedure (49).

RNA-DNA hybridization, S1 nuclease digestion, and analysis of the hybrids on denaturing polyacrylamide gels were performed as described by Favaloro et al. (13). Quantitative analysis of the different transcripts was performed by densitometry using a Scanmaster 3 (Howtek, Inc., Hudson, N.H.) or a high-performance desktop flat-bed color scanner equipped with the RFLPrint (Pdi, Huntington Station, N.Y.) software package or by directly counting the radioactive bands with a PhosphorImager SI (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.).

In vitro translation assay.

In vitro transcription-translation of recombinant plasmids was obtained in an S30 extract prepared from N. meningitidis in the buffer system described by Zubay (59) by making use of [35S]methionine to obtain labeled gene products. Proteins were analyzed on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–15% polyacrylamide gels.

In vitro transposition assay.

The in vitro transposition assay measured the movement of the transposase-defective element from donor plasmid pUC1106::ermC′ to target chromosomal DNA. The target DNA was derived from a rifampin-resistant variant of N. meningitidis strain BL859. Transposition reactions were carried out in 10% glycerol–2 mM dithiothreitol–250 μg of bovine serum albumin ml−1–25 mM HEPES (pH 7.9)–100 mM NaCl–10 mM MgCl2. They contained, in a final volume of 20 μl, 1 μg of donor plasmid, 1 μg of target chromosomal DNA, 500 ng of IS1106T, and different amounts of IS1106Tip. Samples were incubated at 30°C for 3 h and then exposed to 75°C for 10 min to inactivate the enzymes. Before the DNA was transformed into rifampin-sensitive parental strain BL859, single-stranded gaps possibly introduced upon transposition were repaired. Gaps in the DNA were first filled with the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I by using the same buffer system and each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at 1 mM. The enzyme was heat inactivated by 10 min of exposure to a temperature of 75°C. The sample volumes were then raised to 40 μl and 5 U of T4 DNA ligase and ATP to a final concentration of 1 mM were added. The ligation reactions were performed for 3 h at room temperature. Half of the repaired transposition products were used to transform BL859. Transposition events were scored as the recovery of erythromycin-resistant host cells after transformation. The ratio of the total number of erythromycin-resistant transformants to the total number of rifampin-resistant transformants was a measure of IS1106::ermC′ transposition. Each value is the mean of at least five independent experiments. The variation within one set of assays was usually less than twofold.

Cell extract preparation and protein purification

Crude (S30) extracts were prepared from E. coli BL21 λDE3 cells transfected with plasmid pET15b, pET1106T, pET1106Tip, pT7-7, or pT71106Tip grown to early logarithmic phase and induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 2 h at 37°C or not induced. Cells were mechanically broken with a French press in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.2), 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, and 20% glycerol. Induction of E. coli cells transfected with pT71106Tip resulted in the appearance of polypeptides with an apparent molecular mass of 16,000 Da as determined by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Histidine-tagged IS1106T and IS1106Tip were partially purified by the rapid affinity purification protocol in accordance with the Novagen pET system manual.

DNA gel mobility shift assay.

The double-stranded probe used in the gel mobility shift experiments was obtained by annealing the complementary 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotides 5′-GGTCGAGACCTTTGCAAAATTCC-3′ and 5′-GGAATTTTGCAAAGGTCTCGACC-3′ spanning the 19-bp sequence of the left arm of IS1106. The annealing reaction was carried out at 65°C for 1 h.

The gel mobility shift assay was performed by mixing (at 24°C) purified proteins, double-stranded labeled probe, unlabeled competitor DNA, and buffer in a total volume of 20 μl. The final buffer contained 20 mM HEPES, 40 mM KCl, 4% Ficoll, 5 mM spermidine, 0.25 μg of poly(dI-dC) μl−1. The protein concentrations ranged between 2.5 and 25 ng μl−1, and the concentration of the probe was 1 ng μl−1 (20,000 cpm). Unlabeled competitor was added in 5- to 50-fold excess over the labeled DNA. The mixture was incubated for 15 min at 24°C before loading onto a 5% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× standard TBE buffer (1× TBE is 0.0089 M Tris-borate, 0.089 M boric acid, and 0.002 M EDTA), and electrophoresis was carried out at 4°C.

RESULTS

Structure and nucleotide sequence of the N. meningitidis IS1106 element and analysis of transposase-specific transcripts in meningococcal strains.

The IS1106 element located within a complex repetitive region downstream of porA is a rearranged element in which a transposon-like repetitive element (also known as a small repetitive element [SRE]) (10) interrupts the region encoding the amino terminus of the putative IS1106T protein (26). By PCR using two oligonucleotides complementary to the IS1106 inverted-repeat sequences (IRs), we isolated a wild-type element from serogroup B strain BL859 (Fig. 1A). The element has a length of 1,207 bp, is flanked by 19-bp-long IRs (a left IR [IRL] and a right IR [IRR]), and encodes a putative 38,505-Da peptide showing extensive homology to the 5A transposase protein of IS5 (27, 8) (Fig. 1B). Analysis of the DNA sequence revealed the presence of several putative control elements upstream of the start codon of the transposase: (i) a 14-bp-long perfect IR located 2 bp downstream from IRL, (ii) a repeated motif resembling part of the core sequence of the neisserial RS3 repeat (22), and (iii) putative −10 and −35 promoter sequences (Fig. 1A).

We next analyzed transposon-specific transcripts in different serogroup B meningococcal strains by Northern blotting. Total RNAs extracted from either “carrier strain” or “invasive strain” isolates were probed with an IS1106T-specific probe. A specific transcript of about 1,200 nucleotides was detected only in carrier strain isolates (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 4) and not in invasive strain isolates (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 to 8). We performed an S1 mapping experiment to define the ends of this transcript (Fig. 2B). After treatment with S1 nuclease, the amounts of full-length protected hybrids were very low in all of the strains tested and detectable only after overexposure of the autoradiogram. On the contrary, a shorter hybrid was present in considerable amounts only in carrier strains/isolates BF10 and BF18 (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4). The 5′ end corresponded to nucleotide 700 of the IS1106 sequence (Fig. 1A).

Isolation of a transcriptionally active, 5′-end-truncated IS1106 element from the genome of a carrier strain/isolate.

The transcript mapping data led us to hypothesize the existence of a transcriptionally active, rearranged version of the IS1106 element in the meningococcal genome. The sequence of the IS1106 element in the genome of serogroup B carrier strain/isolate BF18 was determined (Fig. 3). Inspection of the nucleotide sequence revealed the presence of a rearranged IS1106 element located downstream of an IS1016-like element (32) (Fig. 3A). Alignment of the rearranged IS1106 sequence with that of the wild type (Fig. 1A) revealed that the element is truncated at the 5′ end and located immediately downstream from a neisserial SRE (Fig. 3B).

The putative start site(s) of the 5′-end-truncated IS1106-specific transcript was determined by S1 nuclease mapping (Fig. 4A). The analysis revealed two major transcripts whose 5′ ends mapped within the SRE located upstream of the rearranged IS1106 element (Fig. 3B). These transcripts could be detected only in carrier strains/isolates BF10 and BF18 (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 and 6) and not in invasive strains/isolates BL858 and BS849 (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4). The absence of the IS1106-specific transcripts in invasive strains/isolates BL858 and BS849 does not depend on a lack of the element because PCR analysis revealed the presence of the truncated IS1106 element (data not shown). We therefore speculated that transcription of the 5′-truncated IS1106 element could be impaired by a point mutation(s). Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of strain BS849 revealed four nucleotide substitutions in the putative promoter region in both strains, mapping 12, 24, 82, and 86 nucleotides upstream of the longer transcription start site, respectively (Fig. 3B).

In the rearranged element, an ORF initiates at the rare codon for leucine TTG (15) (nucleotide 140), possibly encoding a 14,870-Da peptide corresponding to the carboxy-terminal half of the putative wild-type IS1106T . This ORF is found both in the carrier strains/isolates and in the invasive strains/isolates (data not shown). To seek evidence that the 5′-end-truncated IS1106-specific transcripts were translatable, we performed an in vitro translation assay. To this end, the 5′-end-truncated transposase gene from strain BF18 was cloned downstream from the E. coli his promoter to obtain plasmid pUH1106Tip. The recombinant and the vector plasmids were transcribed in vitro and translated by using an S30 extract derived from meningococcal strain BF18 (Fig. 4B). In addition to vector-encoded peptides, a specific translation product of about 16,000 Da was produced by pUH1106Tip (Fig. 4B, lane 2). The size of this peptide was close to the expected molecular mass (14,870 Da) of the 5′-end-truncated transposase (IS1106Tip).

Analysis of ISII06Tip mRNA and distribution of IS1106 in clinical isolates of N. meningitidis.

We next investigated the presence of the IS1106Tip mRNA in clinical isolates of meningococci by S1 mapping. The meningococcal strains were isolated in different regions of Italy and France over the last 10 years. The genetic relationships among 50 clinical isolates and 10 reference strains (45) were determined by comparing RFLP patterns in eight housekeeping genes that were mapped on a physical map (55) to ensure that they were unlinked. The relatedness between strains is shown as a dendrogram (Fig. 5). The results of the S1 mapping analysis, summarized in Table 1, indicated that the 5′-end-truncated form of the IS1106T mRNA was produced in 14 (67%) of 21 meningococcal isolates sampled from the oropharynges of healthy subjects. In contrast, the transcript was detected in only 6 (18%) of 33 isolates derived from the blood or cerebrospinal fluid of patients with meningococcal disease or in strains belonging to several hypervirulent lineages, such as lineage 3, the ET-5 complex, and cluster IV-1. However, it was detected in strains belonging to the ET-37 complex derived either from patients or from healthy subjects.

In most cases, lack of IS1106Tip expression was associated with the same point mutations previously mapped (Fig. 3A). However, in strains of the ET-5 complex, the IS1106Tip gene could not be amplified by PCR, suggesting that a rearrangement or deletion had occurred (data not shown).

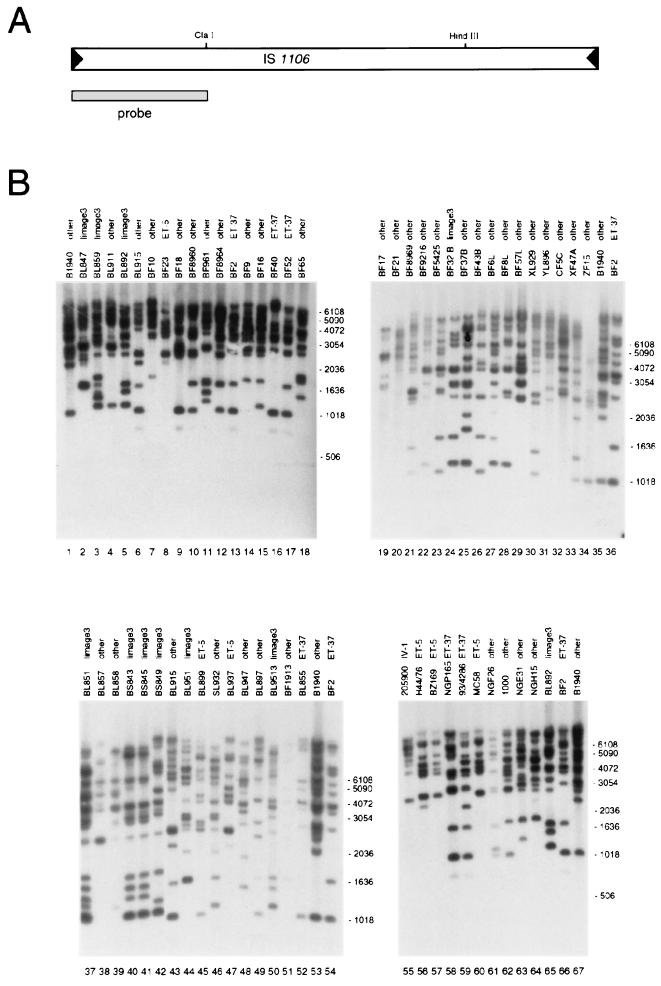

In an attempt to correlate IS1106Tip expression with IS1106 transposition, both the copy number and distribution of the IS1106 elements in the meningococcal clinical isolates were determined by Southern blotting. In the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 6B, any band in the autoradiograph might be interpreted as an insertion of a single copy of either an intact or a truncated IS1106 element. The results demonstrate that IS1106 is present in multiple copies in the genomes of the meningococcal isolates, ranging from about 5 or 6 to more than 15 or 16. The copy number did not correlate with the expression of IS1106 Tip. However, in phylogenetically related strains that do not express IS1106Tip, a high heterogeneity of the insertion pattern was observed. For instance, strains BL847 and BL859, which did not express IS1106 Tip although both belonging to lineage 3 (Fig. 5), appeared to be unrelated on the basis of the IS1106 transposition pattern. A similar heterogeneity was observed in several strains of the ET-5 complex, for instance, BL899 and BL937. By contrast, all of the examined strains of the ET-37 complex that express IS1106Tip exhibited very similar transposition patterns. This suggested that IS1106Tip might act as a negative modulator of IS1106 transposition.

FIG. 6.

Southern blot analysis of IS1106 insertions in the genomes of meningococcal strains. (A) Physical and genetic map of an IS1106 element. The positions of the ClaI and HindIII sites are indicated. The dashed bar below the map corresponds to the 322-bp-long fragment used as a probe in the Southern blot experiment shown in panel B. (B) Total DNAs derived from the meningococcal strains indicated above the panels were digested with EcoRI and HindIII and hybridized to the 332-bp 32P-labeled DNA fragment corresponding to the 5′-proximal one-third of the IS1106 sequence (A). The IS1106 sequence contains a unique HindIII site mapping downstream of the probe but does not contain any EcoRI site (A). Therefore, any band in the autoradiograph might be interpreted as an insertion of a single copy of either an intact or a truncated IS1106 element. The probe we used minimized the detection of rearranged elements because truncation of IS1106 occurred mostly at the 5′-proximal end (data not shown). The relative migrations of molecular size markers (sizes are in base pairs) are shown beside each panel. In addition to the names of the strains, their assignment to hypervirulent lineages is also indicated (lineage 3, ET-5, ET-37, IV-1, and other).

Effects of IS1106Tip expression on in vitro transposition of an IS1106::ermC′ element.

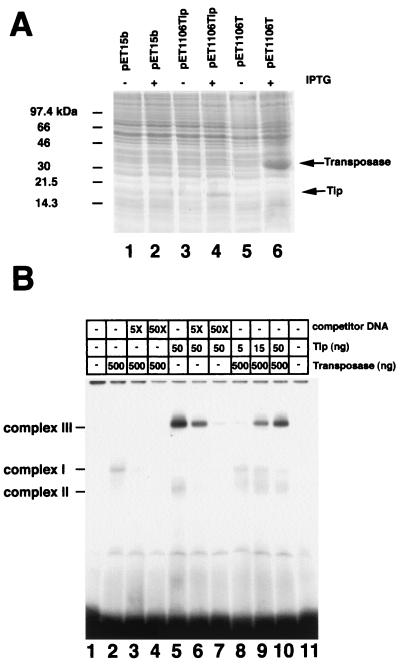

To investigate the possibility that IS1106Tip might function as a repressor of IS1106T, an in vitro transposition assay was developed. Histidine-tagged IS1106T or IS1106Tip overexpressed in E. coli BL21 λDE3 cells (Fig. 7A, lanes 4 and 6) was partially purified and variously mixed with tester DNA. A modified version of IS1106, IS1106::ermC′, was engineered by inserting the ermC′ gene conferring resistance to erythromycin into the gene for IS1106T. The assay measured the movement of the transposase-defective element from a donor plasmid to target rifampin-resistant N. meningitidis chromosomal DNA in the presence of different amounts of partially purified IS1106T and IS1106Tip. The target DNA was used to transform a sensitive N. meningitidis strain to erythromycin or rifampin resistance. Transposition events were scored as the recovery of erythromycin-resistant host cells after natural transformation. As the in vitro treatment was expected to affect the transforming ability of the target DNA, values were normalized with transformation efficiencies to rifampin resistance. Therefore, the ratio of the total number of erythromycin-resistant transformants to the number of rifampin-resistant transformants was taken as a measure of IS1106::ermC′ transposition. The data demonstrate that IS1106T was able to activate transposition of the transposase-defective element in trans and that transposition efficiencies strongly decreased in the presence of IS1106Tip. The extent of inhibition was dependent on the ratio of IS1106T to IS1106Tip (Table 2). In particular, at ratios of 50:1, 10:1, and 2:1 (amounts of IS1106T to amounts of IS1106Tip), the frequencies of transposition events decreased about 5-, 15-, and 50-fold, respectively.

FIG. 7.

DNA-protein interactions between the IS1106 ends and the transposase peptides. (A) Expression of recombinant histidine-tagged IS1106T and IS1106Tip in E. coli. S30 extracts derived from IPTG-induced or uninduced E. coli BL21 λDE3 cells harboring plasmid pET15b (lanes 1 and 2), pET1106Tip (lanes 3 and 4), or pET1106T (lanes 5 and 6) were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The arrows on the right indicate the relative migrations of recombinant IS1106T (Transposase) and IS1106Tip (Tip). The bars on the left indicate the positions of the molecular size markers that were run in parallel. (B) The DNA gel mobility shift assay was performed by incubating a 5′-end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide corresponding to the ends of IS1106 (lane 1) in the presence of partially purified, histidine-tagged IS1106T (lanes 2 to 4), histidine-tagged IS1106Tip (lanes 5 to 7), or a mixture of different amounts of both, as indicated (lanes 8 to 10). In lane 11, the probe was incubated with mock extract. Unlabeled competitor was added in 5- and 50-fold excesses over labeled DNA where indicated. The bars indicate specific DNA-protein complexes I, II, and III.

TABLE 2.

In vitro transposition of IS1106::ermC′ in the presence and absence of IS1106Tipa

| Donor plasmid | Amt of (ng) of:

|

Frequency of erythromycin-resistant clones (Ermr) | Frequency of rifampin-resistant clones (Rifr) | Ermr/Rifr ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS1106T | IS1106Tip | ||||

| None | <10−9 | 5.6 × 10−5 | NDb | ||

| pUC1106::ermC′ | <10−9 | 3.4 × 10−5 | ND | ||

| pUC1106::ermC′ | 500 | 6.3 × 10−7 | 7.3 × 10−6 | 8.6 × 10−2 | |

| pUC1106::ermC′ | 500 | 10 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 7.1 × 10−6 | 1.7 × 10−2 |

| pUC1106::ermC′ | 500 | 50 | 3.6 × 10−8 | 6.2 × 10−6 | 5.8 × 10−3 |

| pUC1106::ermC′ | 500 | 250 | 5.0 × 10−9 | 2.7 × 10−6 | 1.9 × 10−3 |

The assay measured the movement of the transposase-defective element from donor plasmid pUC1106::ermC′ to the target, N. meningitidis rifampin-resistant chromosomal DNA. The target DNA was derived from a rifampin-resistant variant of strain BL859. Transposition reactions were carried out in 20 μl in the presence of 1 μg of donor plasmid, 1 μg of target DNA, 500 ng of IS1106T, and different amounts of IS1106Tip. Before the DNA was transformed into rifampin-sensitive parental strain BL859, single-stranded gaps possibly introduced upon transposition were repaired (Materials and Methods). Transposition events were scored as the recovery of erythromycin-resistant host cells after transformation. The ratio of the total number of erythromycin-resistant transformants to the total number of rifampin-resistant transformants was a measure of IS1106::ermC′ transposition. The values shown are means of at least five independent experiments.

ND, not determined.

Binding of IS1106Tip to the IR of IS1106.

To elucidate the mechanism of inhibition of IS1106 transposition by the truncated transposase, we investigated the ability of IS1106Tip to interfere with binding of the full-length transposase to IS1106 termini (IS1106IR). Incubation of partially purified IS1106T with 5′-end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides corresponding to the IS1106 IR led to the appearance of a retarded complex I (Fig. 7B, lane 2) specifically titrated out by excess cold probe (Fig. 7B, lanes 3 and 4). When the IS1106 IR was incubated with IS1106Tip, two specific major DNA-protein complexes were detected: a faster-migrating one (complex II) and a much more abundant complex that migrated considerably more slowly (complex III) (Fig. 7B, lanes 5 to 7). Significantly, the amount of complex III was much greater than that of the IS1106 IR-IS1106T complex (Fig. 7B, lane 2), although IS1106Tip was used at a concentration 10-fold lower than that of IS1106T. This finding indicated that the truncated transposase was able to bind the IS1106 IR more efficiently than was the full-length transposase. This result was confirmed when the probe was incubated in the presence of both IS1106T and IS1106Tip at different relative ratios (Fig. 7B, lanes 8 to 10). Formation of complex I was substantially inhibited when IS1106Tip and IS1106T were used at a 1:10 ratio (Fig. 7B, lane 10).

DISCUSSION

Transposons have evolved various regulatory mechanisms that limit their movement and the accompanying mutagenic effect within the host cell. Several of these mechanisms are general and involve transcriptional repressors and translational inhibitors (antisense RNA). Others are more specific and include (i) sequestration of translation initiation signals, (ii) programmed translational frameshifting, (iii) coupling of translation termination, transposase binding and transposon activity, (iv) impinging transcription from an outside promoter and/or from within the element, (v) transposase stability, (vi) activity in cis of transposase (32). In this paper, we have characterized the wild-type IS1106 element and a novel mechanism by which this transposon controls its own activity.

Four copies of the wild-type element and several rearranged copies are found in the genome of serogroup A strain Z2491 (Sanger Centre database) (41). Computer sequence analysis of the regions flanking the IS1106 copies in strain Z2491 did not reveal a consensus target site. However, copies of repetitive sequence RS3 are located downstream of several IS1106 elements in the genome of Z2491, suggesting that the primary sequence and/or the architecture of the RS3 or RS3-like sequence may be involved in target site selection and possibly in the orientation of insertion. Interestingly, a repeated motif resembling part of the core sequence of the neisserial RS3 repeat is located upstream to the start codon of the transposase gene and partially overlaps the IRL (Fig. 1A). The analysis of the nucleotide sequence of this region also revealed several putative control elements: −10 and −35 promoter elements and a 14-bp-long perfect IR located in the space between the IRL and the start codon of the transposase gene. Because formation of this palindromic structure at the level of RNA is predicted to sequester the ribosomal binding site, one may speculate that the 14-bp-long IR protects IS1106 from activation by impinging transcription following insertion into highly expressed genes. A similar control mechanism regulates the activity of other transposable elements (32).

Transcriptional mapping analysis has demonstrated the presence, in several meningococcal strains, of an IS1106-specific transcript corresponding to a 5′-end truncated transposase mRNA (Fig. 2). The sequence analysis of the genomic region encoding the truncated transposase (IS1106Tip) revealed the presence of a 5′-end truncated IS1106 element downstream from a neisserial SRE (10) (Fig. 3). SREs have been associated with transposition in neisseriae. It is therefore reasonable that the genomic rearrangement leading to the 5′-end-truncated transposase gene has been promoted by insertion of the SRE into an IS1106 element. Transcription of the IS1106Tip gene starts within the SRE (Fig. 3 and 4A). Transcription from SREs has been reported for other meningococcal genes, including uvrB (2) and drg (7). No canonical ς70-dependent promoter consensus sequence is detectable in the SRE upstream of the truncated transposase gene. However, a putative gearbox promoter sequence (5′-CACCAAGT-3′) is present a few nucleotides upstream of the transcript start site (Fig. 3). Gearbox promoters appear to be involved in the regulation of several genes in E. coli that are induced upon entry into the stationary phase (4, 28, 29). In N. gonorrhoeae, putative gearbox sequences have been identified within the SRE upstream of uvrB and 7 of the 11 opa genes from strain MS11 (2). IS1106Tip mRNA is variably expressed among meningococcal clinical isolates (Table 1). The absence of IS1106Tip-specific transcripts is associated either with mutations in the putative promoter region located within the SRE or with rearrangement/deletion of the gene (in strains of the ET-5 complex).

The results of the in vitro transposition assay demonstrated that IS1106Tip might act as a negative modulator of IS1106 transposition (Table 2). Incomplete transposase peptides contribute to repression of transposition by different mechanisms: (i) binding to an IR, leading to either repression of the transposase pIRL promoter or competition with the transposase for binding to the ends of the element, and (ii) generation of nonproductive heteromultimers with full-length transposase peptides (32). The results of the DNA band shift assays demonstrate that IS1106Tip was able to bind the IS1106 IR more efficiently than the full-length transposase (Fig. 7). This finding was quite surprising, as the DNA binding domains involve N-terminal regions in many transposases (32). IS1106Tip lacks the N-terminal half of IS1106T, including part of the DDE motif (Fig. 1B). The analysis of the amino acid sequence of IS1106T by a computer program for prediction of helix-turn-helix DNA binding motifs using the algorithm of Dodd and Egan (available at http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/) indicated a unique sequence at the C-terminal starting from amino acid 276 to amino acid 297 (Fig. 1B), albeit with a low score (0.84). This sequence is conserved in IS1106Tip (Fig. 3B). In the DNA band shift assays, IS1106Tip generates two complexes (II and III) when mixed with IS1106IR (Fig. 7). We are currently investigating the nature of complex III (Fig. 7). It is possible that it is formed by multimers of IS1106Tip with a molecule(s) of IS1106 IR. Competition with the transposase for binding to the ends of the element and formation of multimers may account for the ability of IS1106Tip to act as a negative modulator of IS1106 transposition.

Lack of IS1106Tip and, possibly, hypertransposition may contribute to plasticity of the meningococcal genomes in several pathogenic clones, playing an adaptive role and leading to changes in virulence in the course of evolution. For instance, it has been proposed that IS1106-mediated transposition and recombination may be involved in genetic instability at the porA locus, thereby influencing antigenic variation of this important surface antigen (26). This hypothesis is further supported by computer sequence analysis of the meningococcal genome (serogroup A strain Z2491). The IS1106 elements are located close to genes encoding virulence factors and subjected to genetic variation, including lbpAB, encoding the lactoferrin receptor (43, 44), and frpC, a meningococcus-specific gene absent in gonococci (as well as porA) (11) and coding for an iron-regulated protein related to the RTX family of cytotoxins (56).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Di Nocera for useful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank M. Frosch, J. C. Chapalain, J. M. Alonzo, P. Nicolas, V. Scarlato, and P. Mastrantuono for providing meningococcal strains.

This work was partially supported by grants from the MURST-PRIN program (D.M. n. 503 DAE-UFFIII, 18/10/1999) and MURST-CNR Biotechnology Program L. 95/95.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arber W. Evolution of prokaryotic genomes. Gene. 1993;135:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black C G, Fyfe J A M, Davies J K. A promoter associated with the neisserial repeat can be used to transcribe the uvrB gene from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1952–1958. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.1952-1958.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blot M. Transposable elements and adaptation of host bacteria. Genetica. 1994;93:5–12. doi: 10.1007/BF01435235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohannon D E, Connell N, Keeneer J, Tormo A, Espinosa-Urgel M, Zambrano M M, Kolter R. Stationary-phase-inducible “gearbox” promoters: differential effects of katF mutations and role of ς70. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4482–4492. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4482-4492.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borst P, Greaves D R. Programmed gene rearrangements altering gene expression. Science. 1987;235:658–667. doi: 10.1126/science.3544215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brynestad S, Synstad B, Granum P E. The Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin gene is on a transposable element in type A human food poisoning strains. Microbiology. 1997;143:2109–2115. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bucci C, Lavitola A, Salvatore P, Del Giudice L, Massardo D R, Bruni C B, Alifano P. Hypermutation in pathogenic bacteria: frequent phase variation in meningococci is a phenotypic trait of a specialized mutator biotype. Mol Cell. 1999;3:435–445. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chernak J M, Schlaffer E J, Smith H O. Synthesis and overproduction of the 5A protein of insertion sequence IS5. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5368–5370. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.11.5368-5370.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins C M, Gutman D M. Insertional inactivation of an Escherichia coli urease gene by IS3411. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:883–888. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.883-888.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correia F F, Inouye S, Inouye M. A family of small repeated elements with some transposon-like properties in the genome of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12194–12198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dempsey J A F, Wallace A B, Cannon J G. The physical map of the chromosome of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis shows complex rearrangements relative to the chromosomes of the two mapped strains of the closely related species N. gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6390–6400. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6390-6400.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dozois C M, Curtiss R., III Pathogenic diversity of Escherichia coli and the emergence of ‘exotic’ islands in the gene stream. Vet Res. 1999;30:157–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Favaloro J, Treisman R, Kamen R. Transcription maps of polyoma virus-specific RNA: analysis by two-dimensional nuclease S1 gel mapping. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:718–749. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fetherston J D, Perry R D. The pigmentation locus of Yersinia pestis KIM6+ is flanked by an insertion sequence and includes the structural genes for pesticin sensitivity and HMWP2. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:697–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Files J G, Weber K, Coulondre C, Miller J H. Identification of the UUG codon as a translational initiation codon in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1975;95:327–330. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster P L. Adaptive mutation—the uses of adversity. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:467–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frosch M, Schultz E, Glenn-Calvo E, Meyer T F. Generation of capsule-deficient Neisseria meningitidis strains by homologous recombination. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1215–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groisman E A, Ochman H. Pathogenicity islands: bacterial evolution in quantum leaps. Cell. 1996;87:791–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81985-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groisman E A, Ochman H. How Salmonella became a pathogen. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:343–349. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas R, Meyer T F. The repertoire of silent pilus genes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: evidence for gene conversion. Cell. 1986;44:107–115. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90489-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Muhldorfer L, Tschape H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammerschmidt S, Hilse R, van Putten J P M, Gerardy-Schahn R, Unkenmeir A, Frosch M. Modulation of cell surface sialic acid expression in Neisseria meningitidis via a transposable genetic element. EMBO J. 1996;15:192–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight A I, Ni H, Cartwright K A V, McFadden J J. Identification of a UK outbreak strain of Neisseria meningitidis with a DNA probe. Lancet. 1990;335:1182–1184. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92697-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knight A I, Ni H, Cartwright K A V, McFadden J J. Identification and characterization of a novel insertion sequence, IS1106, downstream of the porA gene in B15 Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1565–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroger M, Hobom G. Structural analysis of insertion sequence IS5. Nature. 1982;297:159–162. doi: 10.1038/297159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Growth phase-regulated expression of bolA and morphology of stationary-phase Escherichia coli cells are controlled by the novel sigma factor ςs. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4474–4481. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4474-4481.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of a central regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C A. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of bacterial pathogens. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahillon J, Seurinck J, van Rompuy L, Delcour J, Zabeau M. Nucleotide sequence and structural organization of an insertion sequence (IS231) from Bacillus thuringiensis strain berliner 1715. EMBO J. 1985;4:3895–3899. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:725–774. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.725-774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mecsas J J, Strauss E J. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence: type III secretion and pathogenicity islands. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:270–288. doi: 10.3201/eid0204.960403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mobley H L. Helicobacter pylori factors associated with disease development. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(Suppl. 6):S21–S28. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naas T, Blot M, Fitch W M, Arber W. Insertion sequence-related genetic rearrangements in resting Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics. 1994;136:721–730. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naas T, Blot M, Fitch W M, Arber W. Dynamics of IS-related genetic rearrangements in resting Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:198–207. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nei M. Molecular polymorphism and evolution. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North-Holland Publishing Co.; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newcombe J, Cartwright K, Dyer S, McFadden J. Naturally occurring insertional inactivation of the porA gene of Neisseria meningitidis by integration of IS1301. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:453–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ni H, Knight A I, Cartwright K A V, McFadden J J. Phylogenetic and epidemiological analysis of Neisseria meningitidis using DNA probes. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109:227–239. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ni H, Knight A I, Cartwright K A V, Palmer W H, McFadden J J. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of meningococcal meningitidis. Lancet. 1992;340:1432–1434. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92622-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parkhill J, Achtman M, James K D, Bentley S D, Churcher C, Klee S R, Morelli G, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, et al. Complete DNA sequence of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis Z2491. Nature. 2000;404:502–506. doi: 10.1038/35006655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perrin A, Nassif X, Tinsley C. Identification of regions of the chromosome of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae which are specific to the pathogenic Neisseria species. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6119–6129. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6119-6129.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettersson A, Klarenbeek V, van Deurzen J, Poolman J T, Tommassen J. Molecular characterization of the structural gene for the lactoferrin receptor of the meningococcal strain H44/76. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:395–408. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettersson A, Prinz T, Umar A, van der Biezen J, Tommassen J. Molecular characterization of LbpB, the second lactoferrin-binding protein of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:599–610. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pizza M, Scarlato V, Masignani V, Giuliani M M, Arico B, Comanducci M, Jennings G T, Baldi L, Bartolini E, Capecchi B, et al. Identification of vaccine candidates against serogroup B meningococcus by whole-genome sequencing. Science. 2000;287:1816–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rezsohazy R, Hallet B, Delcour J, Mahillon, J J. The IS4 family of insertion sequences: evidence for a conserved transposase motif. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1283–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivellini F, Alifano P, Piscitelli C, Blasi V, Bruni C B, Carlomagno M S M S. A cytosine over guanosine-rich sequence in RNA activates Rho-dependent transcription termination. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:3049–3054. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saint Girons I, Barbour A G. Antigenic variation in Borrelia. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:711–717. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90085-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith J T, Lewin C S. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance and implications for epidemiology. Vet Microbiol. 1993;35:233–242. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90148-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sneath P H A, Sokal R R. Numerical taxonomy. W. H. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman & Co.; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stroeher U H, Jedani K E, Dredge B K, Morona R, Brown M H, Karageorgos L E, Albert M J, Manning P A. Genetic rearrangements in the rfb regions of Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10374–10378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Studier F W, Moffatt B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tettelin H, Saunders N J, Heidelberg J, Jeffries A C, Nelson K E, Eisen J A, Ketchum K A, Hood D W, Peden J F, Dodson R J, et al. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science. 2000;287:1809–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thompson S A, Wang L L, Sparling P F. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of frpC, a second gene from Neisseria meningitidis encoding a protein similar to RTX cytotoxins. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White D A, Barlow A K, Clarke I N, Heckels J E. Stable expression of meningococcal class 1 protein in an antigenically reactive form in outer membranes of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:769–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziebuhr W, Krimmer V, Rachid S, Lossner L, Gotz F, Hacker J. A novel mechanism of phase variation of virulence in Staphylococcus epidermidis: evidence for control of the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin synthesis by alternating insertion and excision of the insertion sequence element IS256. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:345–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zubay G. In vitro synthesis of protein in microbial systems. Annu Rev Genet. 1973;7:267–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.07.120173.001411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]