Abstract

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I and II loci are essential elements of innate and acquired immunity. Their functions include antigen presentation to T cells leading to cellular and humoral immune responses, and modulation of NK cells. Their exceptional influence on disease outcome has now been made clear by genome-wide association studies. The exons encoding the peptide-binding groove have been the main focus for determining HLA effects on disease susceptibility/pathogenesis. However, HLA expression levels have also been implicated in disease outcome, adding another dimension to the extreme diversity of HLA that impacts variability in immune responses across individuals. To estimate HLA expression, immunogenetic studies traditionally rely on quantitative PCR (qPCR). Adoption of alternative high-throughput technologies such as RNA-seq has been hampered by technical issues due to the extreme polymorphism at HLA genes. Recently, however, multiple bioinformatic methods have been developed to accurately estimate HLA expression from RNA-seq data. This opens an exciting opportunity to quantify HLA expression in large datasets but also brings questions on whether RNA-seq results are comparable to those by qPCR. In this study, we analyze three classes of expression data for HLA class I genes for a matched set of individuals: (a) RNA-seq, (b) qPCR, and (c) cell surface HLA-C expression. We observed a moderate correlation between expression estimates from qPCR and RNA-seq for HLA-A, -B, and -C (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53). We discuss technical and biological factors which need to be accounted for when comparing quantifications for different molecular phenotypes or using different techniques.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00251-023-01296-7.

Keywords: HLA, Expression, PCR, RNA-seq

Introduction

Gene expression provides a molecular phenotype that lies at an intermediate position between genetic variation and complex phenotypes, such as disease status. Understanding the genetic basis of gene expression can be strategic to make links between genetic variation and complex phenotypes (GTEx Consortium 2013; Lappalainen et al. 2013), including susceptibility to autoimmune and infectious diseases. Although the study of genetic variation at the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci, and within the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region in general, has been used to dissect the genetic basis of several complex diseases (Trowsdale and Knight 2013; Dendrou et al. 2018), the inclusion of molecular phenotypes, in particular those associated with gene expression, is comparatively recent (Apps et al. 2015; Vince et al. 2016; Ramsuran et al. 2018; Johansson et al. 2022).

The human MHC region on chromosome 6p21 displays a high gene density, with unique patterns of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and extreme polymorphism (de Bakker et al. 2006; Radwan et al. 2020). The MHC region contains the HLA class I and II loci that encode molecules involved in triggering and modulating the immune response. HLA class I molecules are expressed by most nucleated cells and generally present intracellular peptides to CD8+ T cells. In contrast, HLA class II molecules are primarily expressed by professional antigen-presenting cells, and present to CD4+ T cells exogenous antigens that were internalized by endocytosis. Class I molecules are also recognized by receptors on natural killer (NK) cells, the killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), which impacts both education and activation of NK cells (Colonna and Samaridis 1995; Goodson-Gregg et al. 2020). The pairing of different HLA class I allotypes and specific KIR molecules influences NK cell (and a subset of CD8+ T cell) activity, resulting in differential risks to cancer, infectious disease, and autoimmunity (reviewed in Kulkarni et al. 2008).

HLA disease associations have been primarily attributed to allele-specific differences in antigen presentation, owing to the extensive polymorphisms in the peptide-binding groove. However, HLA expression levels contribute to some of the associations observed between HLA polymorphisms and disease outcomes. HLA expression level is an important modifier of autoimmunity and to the strength of the HLA-mediated immune response to cancer and infections (reviewed in René et al. 2016).

There are multiple examples of associations between HLA expression levels and viral infection outcomes. It is well-documented, for example, that higher HLA-C expression levels, at both the mRNA level and protein on the cell surface, associate with better control of HIV-1 (Thomas et al. 2009; Kulkarni et al. 2011; Apps et al. 2013; Parolini et al. 2018; Bachtel et al. 2018), whereas elevated HLA-A expression associates with impaired HIV control (Ramsuran et al. 2018). SARS-CoV-2 infection downregulates HLA-C gene expression (Loi et al. 2022) and HLA class I expression on the cell surface (Zhang et al. 2021; Arshad et al. 2023), as well as HLA class II gene expression, including HLA-DPA1, -DPB1, -DRA, and -DRB1 (Wilk et al. 2020). Additionally, there are associations of HLA-DPA1 (Ou et al. 2019) and HLA-DPB1 (Thomas et al. 2012; Ou et al. 2021) expression levels with HBV clearance; HLA-DRA expression with susceptibility to infection by bat Influenza A viruses in human cell lines (Karakus et al. 2019); and extensive associations between regulatory variants and expression levels at HLA class II genes, including HLA-DQA1, -DQB1, -DQB2, -DRB1, and -DRB5 with antibody response against multiple prevalent viruses (Kachuri et al. 2020).

The expression levels of HLA loci are also associated with autoimmunity (see Johansson et al. 2022 for a review). HLA-C expression levels at the cell surface (Apps et al. 2013; Kulkarni et al. 2013), as well as HLA-G levels on the cell surface and in plasma (da Costa Ferreira et al. 2021), have been associated with risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Increased HLA-B27 expression on the cell surface was observed among ankylosing spondylitis patients (Cauli et al. 2002), as was overall HLA class I expression among Graves’ disease patients (Weider et al. 2021). HLA class II expression levels also influence the risk of autoimmune conditions. HLA-DQA1 and -DRB1 gene expression and expression of DQ and DR molecules on the cell surface are increased in peripheral blood monocytes of vitiligo patients (Cavalli et al. 2016); regulatory variants associated with higher HLA-DQA1, -DQB1, and -DRB1 gene expression and DQ and DR expression on the cell surface are associated with risk of systemic lupus erythematosus (Raj et al. 2016); HLA-DRB5 gene expression is higher in scleroderma patients with interstitial lung disease (Odani et al. 2012); specific HLA-DRB1 alleles are highly expressed in rheumatoid arthritis patients (Houtman et al. 2021); and higher expression of DRB1*15:01 associates with risk of multiple sclerosis (Alcina et al. 2012). Therefore, understanding the variation of HLA expression among individuals and the mechanisms regulating HLA expression levels will be key to uncovering the genetic basis of disease phenotypes.

Traditionally, HLA expression has been estimated by antibody-based techniques for expression levels at the cell surface (Thomas et al. 2012; Apps et al. 2013) or by quantitative PCR (qPCR or RT-PCR) for mRNA transcription levels (Bettens et al. 2014; Ramsuran et al. 2015, 2017). It is challenging to compare results across studies or even compare distinct HLA loci within the same study since different experimental procedures are used for each analysis and for each HLA locus, which can result in different amplification efficiencies in qPCR or antibody affinities in flow cytometry.

High-throughput technologies such as RNA-seq provide expression estimates for all the genes in the genome, including HLA genes, thus allowing evaluation of HLA expression in a genome-wide context. However, these technologies bring many challenges when used to estimate expression levels of the HLA genes. In addition to well-documented biases associated with RNA-seq assays (e.g., batch effects, library preparation, GC content (’t Hoen et al. 2013), the difficulty in estimating expression levels for HLA genes results from the fact that the quantification involves the alignment of short reads to a reference genome, which does not provide a complete representation of the HLA allelic diversity. Therefore, some reads may fail to align because of large numbers of differences with respect to the reference genome (Brandt et al. 2015). In addition, the HLA genes are part of a gene family formed after successive rounds of duplications, and often contain segments that are very similar between paralogs, thus resulting in cross alignments among genes and biased quantification of expression levels. These difficulties motivated the development of computational pipelines (see Johansson et al. 2022 for a review) which account for known HLA diversity in the alignment step and have been shown to provide accurate expression levels for HLA genes (Boegel et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2018; Aguiar et al. 2019; Gutierrez-Arcelus et al. 2020; Darby et al. 2020).

While both RNA-seq and qPCR approaches estimate HLA expression by quantifying the abundance of transcripts, the methods involve different experimental and bioinformatic processing procedures. To our knowledge, a quantitative comparison of results from RNA-seq to those derived from qPCR for HLA genes has not been performed. In this study, we sought to compare different techniques and molecular phenotypes for the quantification of HLA class I expression, keeping in mind that no technique can be considered a gold-standard. To reduce the effect of technical and biological variation in the comparison of different studies, we performed an RNA-seq assay on a set of 96 individuals for which qPCR expression estimates were available (for HLA-A, -B, -C), and for a subset of which HLA-C antibody-based cell surface expression was also available. RNA-seq quantification was performed with an HLA-tailored pipeline which allows for accurate expression estimation, minimizing the bias of standard approaches relying on a single reference genome.

Materials and methods

Samples

Blood samples were obtained from 96 healthy blood donors enrolled in the voluntary donor program at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research (FNLCR). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and specimens were anonymized by IRB-approved procedures of the National Cancer Institute. RNA was extracted from freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) using the RNeasy Universal kit (Qiagen). RNA was treated with RNAse-free DNAse for removal of genomic DNA. Total RNA extracted from PBMCs was quantitated using HT RNA Lab Chip (Caliper, Life Sciences). All samples that showed an RNA quality score greater than 8 were used in the gene expression analyses.

HLA typing

HLA alleles were determined by Sanger sequencing. Additionally, we ran HLApers (Aguiar et al. 2019) and Kourami (Lee and Kingsford 2018) to infer HLA alleles directly from RNA-seq, and checked for agreement with the Sanger sequencing-based calls. If we consider consistent calls between HLApers and Kourami, we observed only 10 discordances with the Sanger calls out of 288 comparisons (3 loci × 96 individuals). Most of them (n = 5) showed support from RNA-seq for an allele very close to the one determined by Sanger sequencing, thus we chose to keep the RNA-seq-based calls. For 3 genotypes, we observe homozygous calls from RNA-seq likely because one allele was not expressed, and we kept the calls from Sanger sequencing. This does not impact expression estimation, since no reads align to the allele not detected via RNA-seq. For one genotype, we observed good support for a heterozygous call where the Sanger sequencing called a homozygote. In that case, we kept the RNA-seq-based call since it better explained the observed reads. For one allele call, we considered an error of the RNA-seq-based calls due to insufficient read coverage.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

HLA mRNA transcription levels for HLA-A, -B, and -C were measured by qPCR in an assay that ensures unbiased amplification of the common alleles at each locus while avoiding amplification of all other loci. The primers utilized were: HLA-A (F, GCTCCCACTCCATGAGGTAT; R, AGTCTGTGACTGGGCCTTCA); HLA-B (F, ACTGAGCTTGTGGAGACCAGA; R, GCAGCCCCTCATGCTGT); HLA-C (F, CTGGCCCTGACCGAGACCTG; R, CGCTTGTACTTCTGTGTCTCC). Reverse transcription was performed using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems). Amplification of HLA and the housekeeping gene β2 microglobulin (B2M) cDNA was performed using Power SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems), on an ABI 7900HT machine. Primer sequences for B2M are described in Table S4 of Kulkarni et al. (2013). The average expression level of each HLA gene was normalized to that of B2M and calculated using the 2-∆∆Ct method (where Ct is the threshold cycle).

Average allele-specific expression levels of common HLA alleles were estimated by a linear model as described in Ramsuran et al. (2015). Specifically, we modeled expression as a linear function of the two alleles carried by each individual and extracted the effects of each allele on gene expression. We performed this step in R (see section Code availability).

Surface expression

HLA-C cell surface expression was measured on CD3+ cells from freshly isolated PBMCs by flow cytometry using the HLA-C specific monoclonal antibody DT9 (Apps et al. 2013). For the HLA-A analysis in a subset of individuals carrying A*03 and A*11, we stained cells with the antibody 0554HA (One Lambda, Inc.).

RNA-seq

RNA preparation

RNA-seq was performed on RNA stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was quantified using the Qubit RNA HS Assay (Thermo Fisher). RNA quality was assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument and an Agilent 6000 RNA Pico Kit (Agilent Technologies). For each sample, 500 ng total RNA was used as input for preparation of whole transcriptome rRNA depleted libraries. An adapter-ligated library was prepared with the KAPA HyperPrep Kit (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) using Bioo Scientific NEXTflex™ DNA Barcoded Adapters (BioScientific, Austin, TX, USA) according to KAPA-provided protocol.

rRNA Depletion using RiboErase

Ribosomal RNA was depleted by incubating total RNA with probes complementary to rRNA sequences. Following hybridization, RNase H was used to enzymatically degrade rRNA. Cleanup and DNase digestion was performed using Kapa Pure Beads and DNase according to Kapa protocol.

Fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, and library construction

rRNA depleted samples were fragmented at 85 °C for 4.5 min in the presence of magnesium prior to 1st and 2nd strand synthesis and A-Tailing reactions. NEXTflex DNA Barcoded Adapters (1.5 uM) were ligated to A-tailed cDNA with a unique barcode for each sample. Products were purified with Kapa Pure Beads and 8 cycles of Library Amplification were performed. Following amplification, a final library cleanup was performed, and library quantification and QC was assessed using Qubit DNA HS Assay (Thermo Fisher) and Agilent DNA HS kit on the 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument.

Sequencing

The resulting multiplexed sequencing libraries were used in cluster formation on an Illumina cBOT (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequencing was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 following Illumina-provided protocols for 2 × 126 bp paired-end sequencing. Each transcriptome was sequenced to a target depth of 40–50 million reads.

RNA-seq on fresh samples from 11 individuals

In order to investigate the possibility of sample degradation of material stored at −80 °C before RNA sequencing, a potential source of disagreement with qPCR estimates, we redrew blood from 11 donors and performed RNA-seq on the new samples. The experiment was carried out with the same library preparation and methods as before, but sequenced using an Illumina NextSeq with 2 × 150 pb reads.

Quantification of expression for RNA-seq

Reference transcriptome

We used Salmon (Patro et al. 2017) to estimate expression levels for all transcripts annotated in the Gencode v37 database. We used all options for bias correction on Salmon (GC bias, positional bias, and sequence-specific bias).

Personalized

Same as “Ref transcriptome,” but with personalized HLA transcripts according to the HLA-A, -B, and -C genotypes carried by each individual. The personalization was carried out by aligning the sequence for the reference genome’s HLA allele to the genome in order to get the coordinates. Then, by using the multi-sequence alignment of the allele present on the reference genome with all the other alleles (available from IPD-IMGT/HLA release 3.43.0 (Robinson et al. 2020)), we attributed genomic positions to all HLA alleles. Finally, we constructed a personalized transcript based on the combination of information of transcript coordinates and the HLA allele’s sequence. This procedure was carried out in R (R Core Team 2020), using the Biostrings package (Pagès et al. 2020) and the tidyverse metapackage (Wickham et al. 2019).

Normalization

We used expression estimates in transcripts per million (TPM), which is the standard normalization produced by Salmon, and corresponds to the relative amount of a given transcript in a sample. For any given gene, the estimate is simply the sum of TPMs for its transcripts. In some cases when we show standard normal transformed estimates, we performed a rank normal transformation of the RNA-seq data using the GenABEL R package (Aulchenko et al. 2007), which is usually applied, for example, in linear models of eQTL mapping (Delaneau et al. 2017).

Read alignment to the reference genome

For the analysis of read coverage at HLA genes reported in Fig. S7, we aligned reads to the reference genome GRCh38 with STAR v2.7.3a (Dobin et al. 2013), using Gencode v37 gene annotations. In order to control for mapping bias at HLA genes, we further processed the BAM files with hla-mapper v4.3 (Castelli et al. 2018).

Simulation

Ground-truth data

To generate simulated data, we first ran Salmon v1.3.0 (Patro et al. 2017) on the real sample #66K00003 to learn the expression levels of Gencode v37 transcripts. Then we used the Polyester package (v1.26.0) to generate 50 synthetic samples with identical transcriptome-wide expression levels, except for HLA-A, -B, and -C. The expression levels for these genes were based on 50 randomly chosen individuals from our real data (for which we have HLA allele data available). For each HLA gene, we selected the isoforms that accounted for at least 90% of the total protein-coding transcript expression in a Salmon run on the real dataset (which resulted in only 1 transcript per gene) and personalized the transcript sequences according to the HLA alleles carried by each individual.

This procedure allowed us to synthetically generate 50 individuals with identical background expression levels, but with variable HLA expression and with HLA polymorphism built into the simulated reads.

In order to mirror our real data, thirty million 126 bp paired-end reads with a mean fragment size of 261 bp were simulated for each individual, using the defaults for other polyester parameters (e.g., standard deviation of the fragment length = 25 bp, error rate = 0.005, uniform distribution of reads, and no bias). Polyester outputs FASTA files, from which we produced FASTQ files with a constant quality score (corresponding symbol “F”).

Metrics for accuracy

TPMs were computed on simulated counts given the transcript lengths and average fragment size of 261 bp. The “Estimated TPM/True TPM” ratio is used to assess performance in recovering simulated expression levels and allows us to observe down or overestimation.

Graphics

We prepared all the plots in this article using the ggplot2 package v3.3.2 (Wickham 2016) in R.

Code availability

All the code for data analysis is publicly available at https://github.com/genevol-usp/nci_hla.

Results

Accuracy of RNA-seq HLA quantification

Given the absence of a method that can be considered the experimental gold standard for HLA expression quantification from RNA-seq data, we initially assessed the accuracy of RNA-seq quantification methods for HLA using simulated data where true expression levels are known, since they are generated in a computer to emulate real experiments. This was done in order to choose the best computational approach among RNA-seq-based methods, allowing a subsequent contrast with non-RNA-seq approaches.

We simulated an RNA-seq experiment for 50 individuals using the Polyester package (Frazee et al. 2015). These synthetic individuals have the same expression levels for all genes in the genome, except for HLA-A, -B, and -C, for which we varied the expression levels. We also personalized the annotated HLA transcript sequences from Gencode v37 to introduce real genetic variation observed in randomly chosen individuals from a dataset of 96 individuals (which were HLA genotyped by Sanger sequencing as described below). The resulting personalized transcripts had a median sequence identity with the reference greater than 95% for all HLA loci.

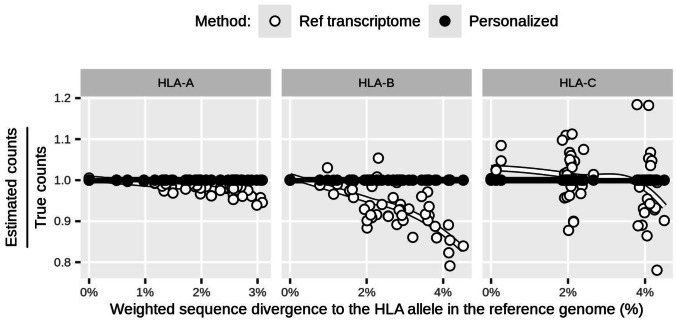

We compared estimates of HLA expression obtained by two bioinformatic methods: (1) “Ref transcriptome,” which uses Salmon (Patro et al. 2017) to align reads to the standard reference transcriptome, quantifying transcript abundance and (2) “Personalized,” which also uses Salmon, but maps reads to personalized HLA transcripts, reflecting the individual’s HLA genotype (Fig. 1). The “Personalized” approach extends our previous strategy (Aguiar et al. 2019) by using a personalized transcript, rather than a single canonical coding sequence for each allele carried by the individual.

Fig. 1.

Accuracy for each simulated individual (represented as a point in each panel of the graph), defined as the fraction of reads from a gene that are correctly assigned to that gene (estimated counts/true counts, Y axis; Y = 1 represents the optimal accuracy). The results are shown as a function of the sequence divergence of the simulated isoforms to the reference isoforms. “Ref transcriptome” pipeline (white), Salmon on lightweight alignment mode; “Personalized” (black), same method but with personalized transcripts for HLA

The “Ref transcriptome” method underestimated expression levels, in particular for alleles with a greater proportion of sequence differences with respect to the reference genome (Fig. 1). This is expected, since a higher mismatch rate between reads and the reference negatively impacts alignment (Brandt et al. 2015). This approach also overestimated HLA-C expression for some individuals, a consequence of reads from HLA-B being mapped to the HLA-C reference transcripts (Fig. S1). The “Personalized” approach, on the other hand, controls the mapping bias and achieves optimal accuracy.

Although our simulation provides encouraging results regarding the quantification of HLA expression using RNA-seq, we must consider some caveats. We modified the sequence of the annotated isoforms according to the individuals’ HLA alleles using a single set of isoforms for all alleles at a given HLA gene. Those sequences were used both in the simulation of reads as well as in the quantification of expression; thus, we expect optimal accuracy. In a real scenario, different HLA alleles might be associated with different isoforms. Later in this paper, we discuss a specific example that we observed for HLA-A, consistent with the hypothesis that certain isoforms are exclusive to specific alleles. Nonetheless, given that we are mainly interested in the gene-level and HLA allele-level expression estimates, we expect that personalized sequences represent an improvement over a single reference transcriptome by reducing mapping bias.

Estimating HLA expression from real RNA-seq data

We performed expression estimation on whole-transcriptome RNA-seq data for 96 individuals, for which qPCR for HLA-A, -B, and -C, and HLA-C surface expression levels were previously estimated (Kulkarni et al. 2013; Ramsuran et al. 2015, 2017), and could be used to compare with the RNA-seq results (see Fig. S2 for QC analyses on RNA-seq data).

Given the higher accuracy of the personalized approach in the simulation, we contrast this method of RNA-seq-based expression estimates to that of other non-RNA-seq approaches, but provide the results for the reference transcriptome-based approaches in the “Supplementary information.” We personalized the transcript sequences given the individual HLA genotypes obtained by Sanger sequencing. We ran HLApers (Aguiar et al. 2019) and Kourami (Lee and Kingsford 2018) to infer alleles directly from the RNA-seq data and confirm the Sanger calls (see “Materials and methods”).

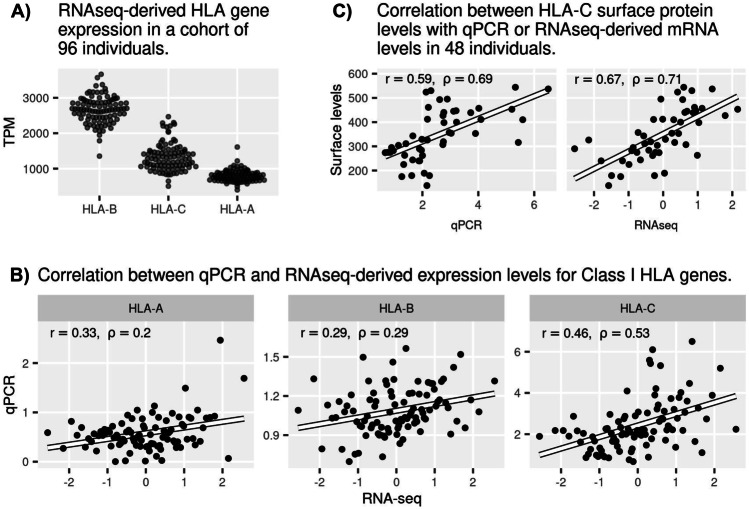

The gene-level expression estimates show that HLA-B has the highest expression among HLA loci in our dataset, followed by HLA-C and HLA-A (Fig. 2A). This ordering is consistent with the GTEx whole blood dataset (GTEx Consortium 2020) and with a previous HLA-capture RNA-seq method applied to PBMCs (Yamamoto et al. 2020). However, this pattern differs from that seen by Boegel et al (2018), who observed similar levels across genes using a different strategy for dealing with reads mapping to multiple loci, which may contribute to the lack of distinction across loci in terms of expression level). Future studies will have to tease apart the contribution of differences in methodologies or cell-type composition to these differences.

Fig. 2.

mRNA abundance estimates from RNA-seq obtained with the personalized approach, and comparison with qPCR estimates and protein surface levels. A RNA-seq-derived HLA expression estimates in transcripts per million (TPM) for classical class I HLA genes. B Correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR derived HLA expression estimates. C Correlation between HLA-C protein levels at the cell surface with mRNA levels obtained with either qPCR or RNA-seq. RNA-seq-based TPM estimates in (B) and (C) were rank-transformed to normality. r, Pearson correlation coefficient; ρ Spearman correlation coefficient

Comparing RNA-seq and qPCR on real data

We next compared RNA-seq expression estimates to those obtained with qPCR (Fig. 2B). Although the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR expression was statistically significant for all genes (p = 0.024, 0.002, 0.000000016, for HLA-A, -B, and -C, respectively; Spearman’s test for positive association), the magnitude of the correlations was modest for HLA-A and -B, and higher for -C. The use of a personalized reference for RNA-seq modestly increased the correlation with qPCR compared to a standard reference (Fig. S3). This agrees with our previous observation that gene-level expression estimates are not substantially different between reference-genome-based or personalized approaches for HLA class I genes (Aguiar et al. 2019), with the main benefit of personalized approaches being the estimates at the HLA allele level, which we explore below. The use of bias correction in Salmon (GC bias, sequence-specific bias, and position-specific bias) improves the correlation with qPCR, with highest impact for HLA-B (compare Figs. 2B and S4, for corrected and uncorrected data, respectively).

Comparing mRNA levels with surface expression

Because RNA expression is informative with regard to the initial steps of cell signaling and response to stimuli, analyzing its relationship to downstream molecular phenotypes (such as protein expression on the cell surface) can help us understand the role of post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation on HLA expression. Differences between RNA and protein abundances are expected since they are subject to distinct modes of regulation. Technical effects can also introduce differences, since RNA and protein techniques differ and are affected by uncorrelated types of error (Li and Biggin 2015; Kaur et al. 2017; Carey et al. 2019). Furthermore, in the case of our study, gene expression was measured on total PBMCs, whereas protein expression was measured on sorted CD3+ cells. With this difference in mind, we measured the degree to which HLA protein on the cell surface can be predicted by mRNA expression. This analysis was performed exclusively for HLA-C, since it is the only locus for which an antibody that can bind all alleles with equal affinities is available. Interestingly, there was a high correlation between mRNA and protein expression for HLA-C, with a slightly higher correlation for RNA-seq (Fig. 2C).

HLA allele-level expression

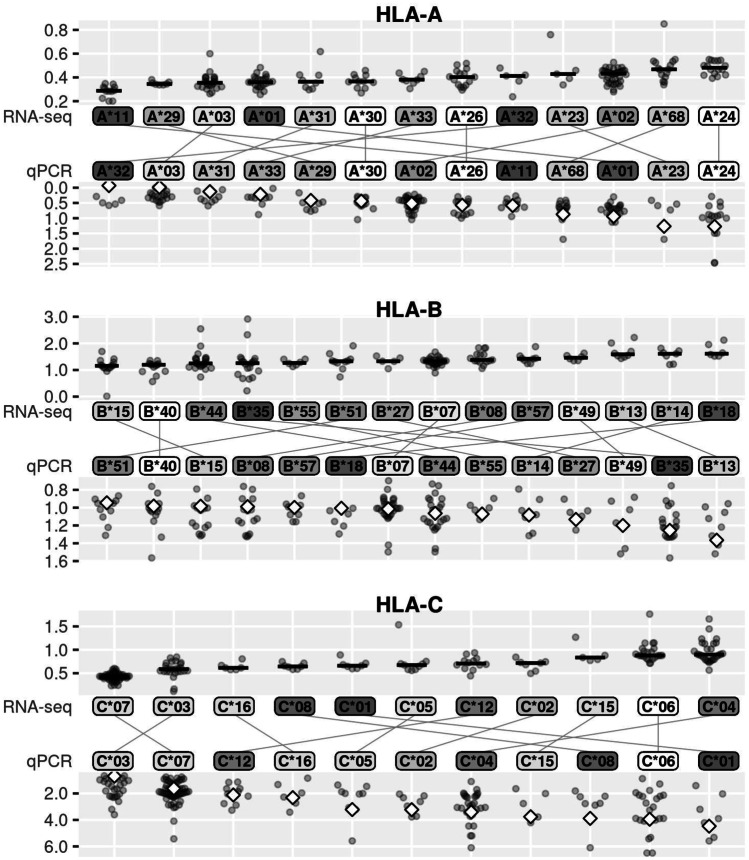

HLA genes harbor regulatory elements associated with constitutive transcription and dynamically activated transcription (René et al. 2016). As a result, HLA expression varies across tissues and can be modulated by regulatory networks triggered by different stimuli (Anderson 2018; Carey et al. 2019). There is increasing interest in understanding whether distinct HLA alleles are associated with different basal expression levels and regulatory programs (Aguiar et al. 2019; Gutierrez-Arcelus et al. 2020), and whether this variation contributes to disease phenotypes or transplantation outcomes (Petersdorf et al. 2014, 2015; René et al. 2016; Bettens et al. 2022; Johansson et al. 2022). Therefore, HLA allele-level expression estimates for qPCR and RNA-seq were compared. Because individual alleles are often quite rare in the dataset, we grouped them by allelic lineages (i.e., groups of alleles that are phylogenetically defined by the relationship of exons) (Elsner et al. 2002).

We ranked lineages according to their expression levels based on both RNA-seq and qPCR data and assessed the concordance of rankings across methods (Fig. 3). Our personalized RNA-seq approach directly provides allele-level estimates, since HLA allele sequences are used to index the alignments, so we ordered allelic lineages according to their median expression levels. Because our qPCR expression estimates are at the gene level and do not directly provide allele-level estimates, we ordered allelic lineages according to their effects in a linear model of expression levels explained by HLA genotype (see Ramsuran et al. 2015). In Fig. 3, the expression values are plotted twice for each donor; for RNA-seq, this represents the estimated expression level for each allele of the individual, and for qPCR, it is simply the gene-level expression plotted twice, reflecting the presence of two alleles.

Fig. 3.

Lineage-level expression estimates. For RNA-seq data, lineages are ordered according to their median expression levels (horizontal bar); for qPCR data, order is according to the lineage effects in a linear model (diamond shapes). Lineage labels are colored by the magnitude of difference of the rankings between qPCR and RNA-seq (dark gray = more different). Allelic lineages with ≥ 5 individuals are shown. Expression levels from RNA-seq are in TPM × 10–3

The ordering of expression estimates is more similar between RNA-seq and qPCR for HLA-C than it is for -A and -B (average absolute order difference, where order difference refers to the observed difference in positions within a ranked order of expression values, between RNA-seq and qPCR quantification, of 2.3 for HLA-C, 3.1 for -A, and 3.9 for -B), following a similar pattern of agreement to that of gene-level expression, for which we found highest correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR for HLA-C.

Among the lineages with the largest differences between RNA-seq and qPCR is A*11. We measured surface expression on a subset of heterozygotes for A*03 or A*11 using an antibody that has equal affinity for both lineages and observed that qPCR correlates more robustly with cell surface expression of these two allotypes than does RNA-seq (Fig. S5). Next, we present a more extensive evaluation of allele orderings through comparisons with previous studies of HLA mRNA expression.

While there is interest in comparing expression differences among HLA alleles, various studies show that variation in expression within an allele or allelic lineage is often quite high, and differences between alleles of different ranks are often small and non-significant. As a consequence, it may be unrealistic to expect a maintenance of ranks across multiple alleles, and it may be preferable to compare expression estimates for alleles at the extremes of expression.

For our RNA-seq data, we compare our estimates with those from two previous HLA-tailored RNA-seq approaches on PBMCs. There is an overall good concordance with Yamamoto et al. (2020), where A*24, A*02, C*04, and C*06 are highly expressed, and A*03, C*03 and B*15 are expressed at low levels, although we also see differences such as for B*35, which would agree more with our qPCR data. When we compare our RNA-seq data with Johansson et al. (2021), however, we see many more differences, although they have very small samples for many lineages.

We also contrast our results with those from two previous qPCR studies that applied allele-specific primers. Bettens et al. (2014) used allele-specific primers for some HLA-C lineages, and saw C*04 and C*06 as highly expressed, whereas C*07 and C*03 were expressed at low levels, in concordance with what we have for both RNA-seq and qPCR. René et al. (2015) applied allele-specific primers for HLA-A, and observed A*02 (high) and A*29 (low) at the extremes of expression, which agrees more with our RNA-seq results than our qPCR; however, we see many differences at other allelic lineages.

In some cases, we can also evaluate agreement with functional studies. For example, previous analyses of transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) and promoter activity (reviewed in Anderson 2018), and studies on miRNA regulation (Kulkarni et al. 2011), show that C*03 and C*07 are weakly expressed alleles, which agrees with our observations for both RNA-seq and qPCR.

Potential sources for differences

We next investigated whether processing of the samples used for RNA-seq could have contributed to the differences between expression estimates obtained with qPCR and RNA-seq.

One specific concern was the length of time the samples were stored in a –80 °C freezer (approximately 4 years between the qPCR and RNA-seq assays), as well as other steps specific to the RNA-seq experiment, including thawing of samples. To address this, we performed a second RNA-seq experiment on fresh blood redrawn from 11 individuals, which are a subset of the 96 analyzed in this study, and we compared the expression estimates between the two timepoints. Even though this second assay carries both technical and biological differences with respect to the first RNA-seq experiment (Fig. S6A and B), the transcriptome-wide correlation in expression estimates between timepoints is high (Fig. S6C). Although assessing correlation with 11 individuals can be noisy, correlations at HLA genes are among the largest gene-wise correlations between the two samples (Fig. S6D and F). We also computed within-individual allele ratios, which is the ratio of expression between the two HLA alleles of a heterozygous individual, and compared them between timepoints. The correlation was greater than 0.94 for HLA-A, -B, and -C (Fig. S6E). Therefore, we saw no evidence for a major contribution of RNA degradation to explain the low correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR in our original sample.

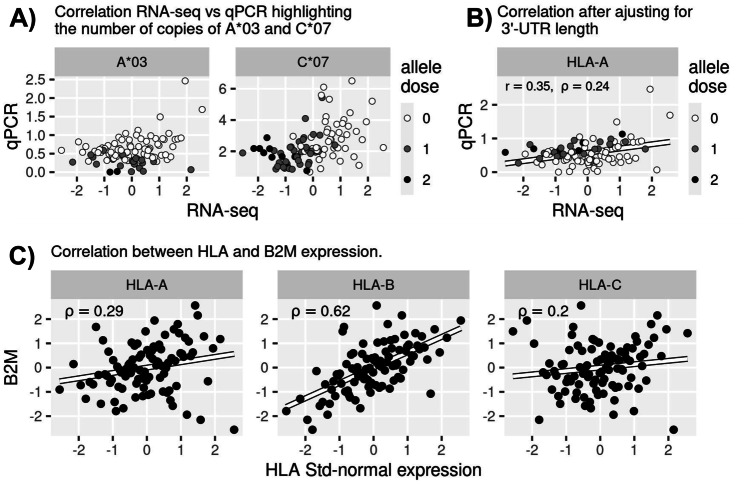

Another possible contribution to differences between RNA-seq and qPCR is that specific HLA alleles may be more biased in one method or the other, in which case individuals carrying such alleles would contribute to large differences. For example, for individuals carrying A*03, or for homozygotes for C*07, there is a negative relationship between qPCR and RNA-seq (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Exploring potential sources for lack of correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR. A Gene-level expression as shown in Fig. 2B, highlighting individuals carrying alleles A*03 and C*07. B Correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR for HLA-A as shown in Fig. 2B, but after adjustment for 3′-UTR length. Points colored by number of copies of either A*01 or A*11. C Correlation of expression between HLA and B2M in the RNA-seq data

An additional source of differences between the methods might arise from the fact that, in our RNA-seq approach, we personalize all Gencode annotated transcripts for every HLA allele; however, true transcript diversity and its association with specific HLA alleles are not well understood. For example, Kulkarni et al. (2017) showed that A*01 and A*11 produce shorter 3′-UTRs. To investigate if we can replicate that finding in our RNA-seq data, we mapped the reads to the reference genome, and corrected for mapping bias at HLA genes with hla-mapper (Castelli et al. 2018). Indeed, for individuals carrying A*01 or A*11, the read coverage at the 3′-UTR of HLA-A shows a sharp drop at ~120 bp before the annotated gene end (Fig. S7).

Because transcript per million (TPM) values are computed taking into account the reference length, using a reference that is longer than the true transcript leads to underestimation of expression. We attempted to control for the possibility of such shorter transcripts by including a version of each HLA-A transcript with a shortened 3′-UTR in our index for read alignment. However, we found no evidence of expression of the shorter isoform (Fig. S8), possibly because these shorter isoforms are contained within the normal-length isoforms, and Salmon’s implementation assigns all reads to the larger isoform. Interestingly, expression at the isoform level reveals an isoform with a longer 5′-UTR exclusive to A*11, which contributes a large proportion of the total expression for this allele (Fig. S8).

We also tested a normalization of our expression estimates, in which we adjusted the read lengths given the read coverage supporting a proximal or distal 3′-UTR terminus (weighted average of transcript lengths using read coverage as weights). Although we observe a gain in up to 20% in the expression levels for individuals carrying A*01 and/or A*11, we see only a small improvement in the correlation with qPCR after this adjustment (from rho = 0.20 in Fig. 2, to rho = 0.24 in Fig. 4B).

A*01 and A*11 are among the alleles with the largest rank differences between RNA-seq and qPCR (Fig. 3), and it is possible that an imperfect representation of their associated transcripts in the annotation introduces bias in our RNA-seq estimates.

Finally, normalization methods used to obtain final expression estimates from the raw qPCR data can also be a source of differences between qPCR and RNA-seq estimates. Quantitative PCR assays for HLA Class I genes usually amplify regions within exons 1 to 4, and a standardization by the expression of a housekeeping gene such as B2M (β2-microglobulin) is typically carried out (as was the case in the present study). The rationale for this procedure is that if expression levels are standardized by a stably expressed reference, the estimates for different individuals are put on the same scale, thus allowing for comparisons across individuals.

B2M encodes for the light chain in the HLA Class I molecule, and it is plausible that B2M and HLA class I genes have some coordination of expression, since they share similar promoter architectures (Kobayashi and van den Elsen 2012; Vijayan et al. 2019), and can be regulated by shared transcription factors (for example, NLRC5/CITA induces the expression of both HLA class I and B2M in Jurkat cell lines (Meissner et al. 2010). It is possible that the normalization of HLA gene expression by correlated values introduces bias in our qPCR estimates, especially for HLA-B, for which we see a high correlation with B2M expression (Fig. 4C). Scaling a variable by a different but correlated variable can introduce perturbation by bringing extreme values to the middle of the distribution and reducing variance; consistent with this hypothesis, the coefficients of variation for the qPCR data are 0.61 and 0.50 for HLA-A and -C, respectively, but drops to 0.17 for HLA-B (as a comparison, CVs for RNA-seq data are 0.20, 0.14, and 0.29 for HLA-A, -B, and -C, respectively). However, using the same qPCR design, Ramsuran et al. (2017) normalized HLA-B expression by either B2M, GAPDH, 18 s, and b-Actin gene, and observed very consistent results, which does not support an impact of B2M normalization to the qPCR estimates.

Discussion

Reliable estimates of HLA transcript expression can contribute to diverse research questions, and although disease outcome is frequently explored in the context of HLA coding variation, expression levels are also likely to explain variation in clinical outcomes (reviewed in Dendrou et al. 2018; and in Johansson et al. 2022). Expression levels also have the potential to inform decisions when planning hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; for example, if a perfect match is unavailable in selection for allogeneic donors, it appears beneficial to select those that are mismatched at low expression alleles (Petersdorf et al. 2014, 2015). Reliable estimates of transcript expression may also assist in identification of eQTLs that underlie the control of HLA expression, which could be integrated into GWAS findings, by querying if known hits in the MHC region coincide with eQTLs for HLA genes (see, e.g., Table S6 in Aguiar et al. 2019). More generally, improved estimates of HLA transcript expression will help us understand the genetic architecture of HLA regulation, identifying the relative contribution of cis-acting variants (i.e., those in the neighborhood of the HLA gene they regulate) and trans-acting variants (those in distant genomic locations, including on other chromosomes). This will provide information regarding the degree to which variation in HLA expression is an allele-specific property vs. an inter-individual characteristic independent of allelic identity (see Bettens et al. 2022).

Quantitative PCR techniques have enabled us to uncover associations between HLA expression and disease phenotypes. More recently, RNA-seq has become the method of choice to assess gene expression in large whole-transcriptome datasets of different populations. Being able to extract accurate information for HLA expression from such data is an important challenge, and many methods have been proposed to achieve this goal. However, the degree to which the results emerging from RNA-seq analyses agree with those accumulated by the use of qPCR is currently unknown. Although these methods target the same molecular phenotype (RNA abundance), they differ markedly in the experimental techniques used, the forms of analyzing and normalizing the data, the bioinformatic procedures, and the biases they are subject to.

To our knowledge, previous studies comparing HLA-tailored RNA-seq approaches with qPCR included small samples. For example, Johansson et al. (2021) validated their HLA-targeted RNA-seq with qPCR on only 5 samples at HLA-C, finding a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.9, which was not significant (p = 0.08).

In the present study, we compared quantitative PCR and RNA-seq expression estimates for the classical HLA class I gene HLA-A, -B and -C in a matched set of 96 individuals. We found modest but significant correlations in expression over a sample of 96 individuals. Given the lack of a gold standard with which to compare these estimates, it is possible that estimation errors and biases associated with both methods contribute to the overall result.

We explored the effects of various factors that may explain the low correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR estimates, such as poor estimation of expression for specific HLA alleles and normalization by a single housekeeping gene in qPCR. Our results cannot be generalized to every qPCR design or RNA-seq pipeline, for which there are a wide variety of different approaches. However, to our knowledge, this is the first direct comparison between qPCR and RNA-seq for the estimation of HLA expression.

Our study suggests areas that require improvement in the determination of HLA transcript expression. Comparisons between RNA-seq and qPCR, for example, should employ uniform processing of samples across methods (e.g., same RNA isolation protocol, storage/thawing time, RNA integrity) in order to limit artifactual differences associated with these methods. Mapping short reads to single reference genomes or transcriptomes clearly generates biases, and strategies that map reads accounting for HLA polymorphism are necessary. Given that there are several strategies to accomplish this (Boegel et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2018; Aguiar et al. 2019; Gutierrez-Arcelus et al. 2020; Darby et al. 2020), it will be key to compare the relative accuracy of these approaches. There is also a need to develop methods that adequately account for isoform variation, not only to provide another layer of information, but also more accurate expression estimates, since normalization of read counts by an incorrect transcript length is a potential source of error. In this context, long-read data, which directly generates full transcript information, can be a powerful tool (Cornaby et al. 2022). Finally, copy number variation, a known feature for certain HLA loci (e.g., DRB), should also be considered when quantifying expression levels.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tatiana Torres (University of São Paulo), Yang Luo (Harvard Medical School), and the members of the Joint Biology Consortium in Boston, for their helpful discussions.

Author contribution

Diogo Meyer, Mary Carrington, Richard M. Single and Vitor R. C. Aguiar contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and experiments were performed by Maureen P. Martin, Veron Ramsuran, Smita Kulkarni, Arman Bashirova, Danillo G. Augusto, and Mary Carrington. Data analysis was performed by Vitor R. C. Aguiar, Erick Castelli, Richard M. Single, Maria Gutierrez-Arcelus and Diogo Meyer. The manuscript was written by Vitor R. C. Aguiar and Diogo Meyer. All authors read, made contributions, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The São Paulo Funding Agency (FAPESP, http://www.fapesp.br/en/) provided funding to DM (2012/18010-0 and 2013/22007-7) and to VRCA (2014/12123-2 and 2016/24734-1). The National Institutes of Health, USA provided funding to DM (NIH R01 GM075091), which supported part of VRCA postdoc. Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) & Ministry of Health, Brazil provided funding for the RNA-seq experiments and research travel visits, as part of a US-Brazil joint proposal awarded to MC and DM (470043/2014-8). NIH/NIAID R01AI157850 supports SK. VR was funded the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) with funds from the Department of Science and Technology (DST); and also supported in part through the Sub-Saharan African Network for TB/HIV Research Excellence (SANTHE), a DELTAS Africa Initiative (Grant # DEL-15-006) by the AAS. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This Research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Frederick National Lab, Center for Cancer Research.

Data availability

The RNA-seq data presented in the current publication have been deposited in and are available from the dbGaP database under dbGaP accession phs003177.v1.p1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vitor R. C. Aguiar, Email: vitor@ib.usp.br

Diogo Meyer, Email: diogo@ib.usp.br.

References

- Aguiar VRC, César J, Delaneau O et al (2019) Expression estimation and eQTL mapping for HLA genes with a personalized pipeline. PLoS Genet 15:e1008091. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alcina A, Abad-Grau MDM, Fedetz M et al (2012) Multiple sclerosis risk variant HLA-DRB1*1501 associates with high expression of DRB1 gene in different human populations. PLoS One 7:e29819. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Anderson SK. Molecular evolution of elements controlling HLA-C expression: Adaptation to a role as a killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor ligand regulating natural killer cell function. HLA. 2018;92:271–278. doi: 10.1111/tan.13396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apps R, Meng Z, Del Prete GQ, et al. Relative expression levels of the HLA class-I proteins in normal and HIV-infected cells. J Immunol. 2015;194:3594–3600. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apps R, Qi Y, Carlson JM, et al. Influence of HLA-C expression level on HIV control. Science. 2013;340:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1232685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad N, Laurent-Rolle M, Ahmed WS et al (2023) SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins ORF7a and ORF3a use distinct mechanisms to down-regulate MHC-I surface expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120:e2208525120. 10.1073/pnas.2208525120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, van Duijn CM. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1294–1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtel ND, Umviligihozo G, Pickering S et al (2018) HLA-C downregulation by HIV-1 adapts to host HLA genotype. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007257. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bettens F, Brunet L, Tiercy J-M. High-allelic variability in HLA-C mRNA expression: association with HLA-extended haplotypes. Genes Immun. 2014;15:176–181. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettens F, Ongen H, Rey G et al (2022) Regulation of HLA class I expression by non-coding gene variations. PLoS Genet 18:e1010212. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boegel S, Bukur T, Castle JC, Sahin U. In Silico Typing of Classical and Non-classical HLA Alleles from Standard RNA-Seq Reads. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1802:177–191. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8546-3_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boegel S, Löwer M, Schäfer M, et al. HLA typing from RNA-Seq sequence reads. Genome Med. 2012;4:102. doi: 10.1186/gm403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt DYC, Aguiar VRC, Bitarello BD et al (2015) Mapping Bias Overestimates Reference Allele Frequencies at the HLA Genes in the 1000 Genomes Project Phase I Data. G3 5:931–941. 10.1534/g3.114.015784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carey BS, Poulton KV, Poles A. Factors affecting HLA expression: A review. Int J Immunogenet. 2019;46:307–320. doi: 10.1111/iji.12443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli EC, Paz MA, Souza AS, et al. Hla-mapper: An application to optimize the mapping of HLA sequences produced by massively parallel sequencing procedures. Hum Immunol. 2018;79:678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauli A, Dessole G, Fiorillo MT, et al. Increased level of HLA-B27 expression in ankylosing spondylitis patients compared with healthy HLA-B27-positive subjects: a possible further susceptibility factor for the development of disease. Rheumatology. 2002;41:1375–1379. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.12.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli G, Hayashi M, Jin Y, et al. MHC class II super-enhancer increases surface expression of HLA-DR and HLA-DQ and affects cytokine production in autoimmune vitiligo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:1363–1368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523482113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M, Samaridis J. Cloning of immunoglobulin-superfamily members associated with HLA-C and HLA-B recognition by human natural killer cells. Science. 1995;268:405–408. doi: 10.1126/science.7716543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornaby C, Montgomery MC, Liu C, Weimer ET (2022) Unique Molecular Identifier-Based High-Resolution HLA Typing and Transcript Quantitation Using Long-Read Sequencing. Front Genet 13:901377. 10.3389/fgene.2022.901377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- da Costa FS, Sadissou IA, Parra RS, et al. Increased HLA-G Expression in Tissue-Infiltrating Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2610–2618. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby CA, Stubbington MJT, Marks PJ, et al. scHLAcount: allele-specific HLA expression from single-cell gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:3905–3906. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bakker PIW, McVean G, Sabeti PC, et al. A high-resolution HLA and SNP haplotype map for disease association studies in the extended human MHC. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/ng1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaneau O, Ongen H, Brown AA, et al. A complete tool set for molecular QTL discovery and analysis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15452. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dendrou CA, Petersen J, Rossjohn J, Fugger L. HLA variation and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:325–339. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsner H-A, Rozas J, Blasczyk R. The nature of introns 4–7 largely reflects the lineage specificity of HLA-A alleles. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:447–462. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazee AC, Jaffe AE, Langmead B, Leek JT. Polyester: simulating RNA-seq datasets with differential transcript expression. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2778–2784. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson-Gregg FJ, Krepel SA, Anderson SK. Tuning of human NK cells by endogenous HLA-C expression. Immunogenetics. 2020;72:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s00251-020-01161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GTEx Consortium The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GTEx Consortium The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science. 2020;369:1318–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Arcelus M, Baglaenko Y, Arora J, et al. Allele-specific expression changes dynamically during T cell activation in HLA and other autoimmune loci. Nat Genet. 2020;52:247–253. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0579-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtman M, Hesselberg E, Rönnblom L et al (2021) Haplotype-Specific Expression Analysis of MHC Class II Genes in Healthy Individuals and Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Front Immunol 12:707217. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.707217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johansson T, Partanen J, Saavalainen P (2022) HLA allele-specific expression: Methods, disease associations, and relevance in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol 13. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1007425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johansson T, Yohannes DA, Koskela S et al (2021) HLA RNA Sequencing With Unique Molecular Identifiers Reveals High Allele-Specific Variability in mRNA Expression. Front Immunol 12:629059. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.629059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kachuri L, Francis SS, Morrison ML, et al. The landscape of host genetic factors involved in immune response to common viral infections. Genome Med. 2020;12:93. doi: 10.1186/s13073-020-00790-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakus U, Thamamongood T, Ciminski K, et al. MHC class II proteins mediate cross-species entry of bat influenza viruses. Nature. 2019;567:109–112. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0955-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G, Gras S, Mobbs JI, et al. Structural and regulatory diversity shape HLA-C protein expression levels. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15924. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi KS, van den Elsen PJ. NLRC5: a key regulator of MHC class I-dependent immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:813–820. doi: 10.1038/nri3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Martin MP, Carrington M. The Yin and Yang of HLA and KIR in human disease. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Qi Y, O’hUigin C, , et al. Genetic interplay between HLA-C and MIR148A in HIV control and Crohn disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20705–20710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312237110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Ramsuran V, Rucevic M, et al. Posttranscriptional Regulation of HLA-A Protein Expression by Alternative Polyadenylation Signals Involving the RNA-Binding Protein Syncrip. J Immunol. 2017;199:3892–3899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Savan R, Qi Y, et al. Differential microRNA regulation of HLA-C expression and its association with HIV control. Nature. 2011;472:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature09914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen T, Sammeth M, Friedländer MR, et al. Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature. 2013;501:506–511. doi: 10.1038/nature12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Kingsford C. Kourami: graph-guided assembly for novel human leukocyte antigen allele discovery. Genome Biol. 2018;19:16. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1388-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Plant K, Humburg P, Knight JC. AltHapAlignR: improved accuracy of RNA-seq analyses through the use of alternative haplotypes. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2401–2408. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JJ, Biggin MD. Gene expression. Statistics Requantitates the Central Dogma Science. 2015;347:1066–1067. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi E, Moi L, Cabras P et al (2022) HLA-C dysregulation as a possible mechanism of immune evasion in SARS-CoV-2 and other RNA-virus infections. Front Immunol 13. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1011829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Meissner TB, Li A, Biswas A, et al. NLR family member NLRC5 is a transcriptional regulator of MHC class I genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13794–13799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008684107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odani T, Yasuda S, Ota Y, et al. Up-regulated expression of HLA-DRB5 transcripts and high frequency of the HLA-DRB5*01:05 allele in scleroderma patients with interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology. 2012;51:1765–1774. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou G, Liu X, Xu H, et al. Variation and expression of HLA-DPB1 gene in HBV infection. Immunogenetics. 2021;73:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s00251-021-01213-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou G, Liu X, Yang L, et al. Relationship between HLA-DPA1 mRNA expression and susceptibility to hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:155–161. doi: 10.1111/jvh.13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagès H, Aboyoun P, Gentleman R, DebRoy S (2020) Biostrings: Efficient manipulation of biological strings. Version 2.56.0. http://bioconductor.org/packages/Biostrings/. Accessed 16 Oct 2020

- Parolini F, Biswas P, Serena M et al (2018) Stability and Expression Levels of HLA-C on the Cell Membrane Modulate HIV-1 Infectivity. J Virol 92. 10.1128/JVI.01711-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, et al. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods. 2017;14:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersdorf EW, Gooley TA, Malkki M, et al. HLA-C expression levels define permissible mismatches in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2014;124:3996–4003. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-599969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersdorf EW, Malkki M, O’hUigin C, , et al. High HLA-DP Expression and Graft-versus-Host Disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:599–609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org. Accessed 12 Feb 2021

- Radwan J, Babik W, Kaufman J, et al. Advances in the Evolutionary Understanding of MHC Polymorphism. Trends Genet. 2020;36:298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj P, Rai E, Song R et al (2016) Regulatory polymorphisms modulate the expression of HLA class II molecules and promote autoimmunity. Elife 5. 10.7554/eLife.12089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ramsuran V, Hernández-Sanchez PG, O’hUigin C, , et al. Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Untranslated Promoter Regions for Class I Genes. J Immunol. 2017;198:2320–2329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsuran V, Kulkarni S, O’huigin C, , et al. Epigenetic regulation of differential HLA-A allelic expression levels. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:4268–4275. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsuran V, Naranbhai V, Horowitz A, et al. Elevated HLA-A expression impairs HIV control through inhibition of NKG2A-expressing cells. Science. 2018;359:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.aam8825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- René C, Lozano C, Eliaou J-F. Expression of classical HLA class I molecules: regulation and clinical impacts: Julia Bodmer Award Review 2015. HLA. 2016;87:338–349. doi: 10.1111/tan.12787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- René C, Lozano C, Villalba M, Eliaou J-F. 5’ and 3' untranslated regions contribute to the differential expression of specific HLA-A alleles. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:3454–3463. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Barker DJ, Georgiou X, et al. IPD-IMGT/HLA Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D948–D955. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ’t Hoen PAC, Friedländer MR, Almlöf J, , et al. Reproducibility of high-throughput mRNA and small RNA sequencing across laboratories. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1015–1022. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, Apps R, Qi Y, et al. HLA-C cell surface expression and control of HIV/AIDS correlate with a variant upstream of HLA-C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1290–1294. doi: 10.1038/ng.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, Thio CL, Apps R, et al. A novel variant marking HLA-DP expression levels predicts recovery from hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2012;86:6979–6985. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00406-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowsdale J, Knight JC. Major histocompatibility complex genomics and human disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:301–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan S, Sidiq T, Yousuf S, et al. Class I transactivator, NLRC5: a central player in the MHC class I pathway and cancer immune surveillance. Immunogenetics. 2019;71:273–282. doi: 10.1007/s00251-019-01106-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince N, Li H, Ramsuran V, et al. HLA-C Level Is Regulated by a Polymorphic Oct1 Binding Site in the HLA-C Promoter Region. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:1353–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weider T, Richardson SJ, Morgan NG, et al. HLA Class I Upregulation and Antiviral Immune Responses in Graves Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:e1763–e1774. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J et al (2019) Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw 4:1686. 10.21105/joss.01686

- Wilk AJ, Rustagi A, Zhao NQ, et al. A single-cell atlas of the peripheral immune response in patients with severe COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1070–1076. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0944-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto F, Suzuki S, Mizutani A, et al. Capturing Differential Allele-Level Expression and Genotypes of All Classical HLA Loci and Haplotypes by a New Capture RNA-Seq Method. Front Immunol. 2020;11:941. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li Y et al (2021) The ORF8 protein of SARS-CoV-2 mediates immune evasion through down-regulating MHC-Ι. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118. 10.1073/pnas.2024202118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data presented in the current publication have been deposited in and are available from the dbGaP database under dbGaP accession phs003177.v1.p1.