Abstract

目的

探讨全螺纹空心加压螺钉与部分螺纹空心螺钉治疗股骨颈骨折的疗效差异。

方法

回顾性分析2013年4月—2021年2月收治且符合选择标准的152例股骨颈骨折患者临床资料。其中74例采用全螺纹空心加压螺钉(试验组)、78例采用部分螺纹空心螺钉(对照组)固定骨折。两组患者年龄、性别、身体质量指数、致伤原因、受伤至手术时间以及骨折侧别、Garden分型、Pauwels分型等一般资料比较,差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。记录两组手术时间、术中出血量、住院时间、随访时间以及Harris评分。术后X线片复查,评价骨折复位质量及愈合情况、颈干角变化、股骨颈短缩程度,以及内固定失败、螺钉回退、股骨头坏死发生情况。

结果

两组手术时间、住院时间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),但试验组术中出血量少于对照组(P<0.05)。两组患者均获随访,其中试验组随访时间为(24.11±4.04)个月、对照组为(24.10±4.42)个月,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。X线片复查示两组骨折复位质量差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。随访期间对照组7例、试验组6例发生骨不连,其余骨折均愈合,且试验组骨折愈合时间较对照组缩短(P<0.05);两组骨不连发生率比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。随访期间试验组2例、对照组5例发生股骨头坏死,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);对股骨头坏死患者行二次手术。试验组3例、对照组9例发生螺钉回退,发生率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),但试验组螺钉回退距离短于对照组(P<0.05);试验组4例发生内固定失败,少于对照组(14例),差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。试验组术后1年股骨颈短缩发生率及短缩程度、颈干角变化均小于对照组,末次随访时Harris评分高于对照组,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05)。

结论

与部分螺纹空心螺钉相比,全螺纹空心加压螺钉可以有效维持骨折复位,避免股骨颈短缩、内固定失败,是股骨颈骨折内固定治疗的一个较好选择。

Keywords: 股骨颈骨折, 内固定, 全螺纹空心加压螺钉, 部分螺纹空心螺钉

Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of full thread compression cannulated screw and partial thread cannulated screw in the treatment of femoral neck fracture.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was made on 152 patients with femoral neck fractures, who met the selection criteria, between April 2013 and February 2021. The fractures were fixed with the full thread compression cannulated screws in 74 cases (trial group) and the partial thread cannulated screws in 78 cases (control group). There was no significant difference in general data such as age, gender, body mass index, cause of injury, time from injury to operation, and the side, Garden typing, Pauwels typing of fracture between the two groups (P>0.05). The operation time, intraoperative blood loss, hospital stay, follow-up time, and Harris score were recorded in both groups. X-ray films were performed to evaluate the quality of fracture reduction and bone healing, the changes of neck-shaft angle, the changes of femoral neck, as well as the occurrence of internal fixation failure, screw back-out, and osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

Results

There was no significant difference in operation time and hospital stay between the two groups (P>0.05). However, the intraoperative blood loss in the trial group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P<0.05). Patients in both groups were followed up, with the follow-up time of (24.11±4.04) months in the trial group and (24.10±4.42) months in the control group, and the difference was not significant (P>0.05). Postoperative X-ray films showed that there was no significant difference in fracture reduction grading between the two groups (P>0.05). Six cases in the trial group developed bone nonunion and 7 cases in the control group, the fractures of the other patients healed, and the healing time was significantly shorter in the trial group than in the control group (P<0.05). There was no significant difference in the incidence of bone nonunion between the two groups (P>0.05). During follow-up, 2 cases in the trial group and 5 cases in the control group had osteonecrosis of the femoral head, the difference was not significant (P>0.05), and the patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head were treated with secondary operation. The screw back-out occurred in 3 cases of the trial group and in 9 cases of the control group, showing no significant difference (P>0.05). But the screw back-out distance was significantly shorter in the trial group than in the control group (P<0.05). The incidence of internal fixation failure in the trial group (4 cases) was significantly lower than that in the control group (14 cases) (P<0.05). The incidence of femoral neck shortening and the change of neck-shaft angle at 1 year after operation were significantly lower in the trial group than in the control group (P<0.05). The Harris score at last follow-up was significantly higher in the trial group than in the control group (P<0.05).

Conclusion

Compared with the partial threaded cannulated screws, the full threaded cannulated compression screws can effectively maintain fracture reduction, avoid femoral neck shortening, and internal fixation failure. It is a better choice for femoral neck fracture.

Keywords: Femoral neck fracture, internal fixation, full thread compression cannulated screw, partial thread cannulated screw

随着人均寿命增长以及人口老龄化加重,股骨颈骨折患者数量逐年增加,据统计2000年有160万例髋部骨折患者,约60%为股骨颈骨折,预计2050年髋部骨折患者将达626万例[1]。对于年龄<65岁或无移位的股骨颈骨折常用空心螺钉内固定,自20世纪80年代开始空心螺钉三角形平行固定已成为内固定的“金标准”[2]。然而部分螺纹空心螺钉内固定时,如头部植入过长易穿透关节软骨,植入过短则导致螺纹不能全部通过骨折线,无法完成对骨折端加压;钉尾留置较长也无法对骨折端进行加压,同时术后股骨颈短缩、内固定激惹以及内收型骨折固定失效等严重并发症发生风险较高[3-4]。基于此,有学者提出采用全螺纹空心加压螺钉治疗股骨颈骨折,尸体标本生物力学研究也显示出明显优势[5]。但目前有关该内固定方法的临床研究有限,为此我们回顾分析了2013年4月—2021年2月采用全螺纹空心加压螺钉或部分螺纹空心螺钉内固定治疗的股骨颈骨折患者临床资料,比较两种内固定方式疗效。报告如下。

1. 临床资料

1.1. 一般资料

纳入标准:① 闭合性股骨颈骨折;② 受伤3周内手术。排除标准:① 年龄>65岁或<18岁;② 肿瘤或病理性股骨颈骨折;③ 存在髋关节手术史,同侧或患侧髋关节或股骨畸形、发育不良;④ 长期服用激素类药物;⑤ 有长期酗酒及吸烟史;⑥ 失访患者。

2013年4月—2021年2月,共152例患者符合选择标准纳入研究。其中74例患者采用全螺纹空心加压螺钉(试验组)、78例采用部分螺纹空心螺钉(对照组)固定骨折。两组患者年龄、性别、身体质量指数、致伤原因、受伤至手术时间以及骨折侧别、Garden分型、Pauwels分型等一般资料比较,差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05),见表1。

表 1.

Comparison of general data between the two groups

两组患者一般资料比较

| 项目 Item |

试验组(n=74) Trial group (n=74) |

对照组(n=78) Control group (n=78) |

统计值 Statistic |

年龄( ,岁) ,岁) |

54.65±11.88 | 53.35±9.80 |

t=–0.739 P=0.461 |

| 性别 [例(%)] | |||

| 男 | 27(36.49) | 37(47.44) | χ2=1.868 |

| 女 | 47(63.51) | 41(52.56) | P=0.172 |

身体质量指数( , kg/m2) , kg/m2) |

26.18±4.82 | 26.74±4.01 |

t=0.791 P=0.430 |

| 致伤原因 [例(%)] | |||

| 摔伤 | 67(90.54) | 62(79.49) | χ2=3.909 |

| 交通事故伤 | 3(4.05) | 9(11.54) | P=0.142 |

| 高处坠落伤 | 4(5.41) | 7(8.97) | |

受伤至手术时间( , d) , d) |

4.21±1.50 | 4.39±1.59 |

t=1.353 P=0.177 |

| 骨折侧别 [例(%)] | |||

| 左侧 | 32(43.24) | 34(43.59) | χ2=0.002 |

| 右侧 | 42(56.76) | 44(56.41) | P=0.996 |

| Garden 分型 [例(%)] | |||

| Ⅰ型 | 17(22.97) | 8(10.26) | Z=–1.154 |

| Ⅱ型 | 12(16.22) | 15(19.23) | P=0.249 |

| Ⅲ型 | 24(32.43) | 32(41.03) | |

| Ⅳ型 | 21(28.38) | 23(29.49) | |

| Pauwels分型 [例(%)] | |||

| Ⅰ型 | 4(5.41) | 7(8.97) | Z=–0.717 |

| Ⅱ型 | 20(27.03) | 22(28.21) | P=0.473 |

| Ⅲ型 | 50(67.57) | 49(62.82) | |

1.2. 手术方法

两组手术均由同一组术者完成。根据患者一般情况选择椎管内麻醉或全身麻醉后,患者仰卧于牵引床上,健侧半截石位固定,患髋先外展外旋位牵引,然后保持牵引内收内旋复位,C臂X线机透视复位满意后固定牵引。复位满意标准:股骨正位X线片示骨折端解剖复位或者阳性支撑,Garden对线指数>160°;侧位Garden对线指数为180°;正、侧位均可见Lowell S形曲线。于股骨近端外侧切开皮肤、阔筋膜张肌,导针平行呈倒三角形分布,正、侧位透视见导针位置满意后,经导针植入全螺纹空心加压螺钉(长度80~100 mm,尾部直径7.5 mm,头部直径6.5 mm;Acumed公司,美国)或者部分螺纹空心螺钉(长度80~100 mm,直径6.5 mm;Stryker公司,美国)。C臂X线机透视明确螺钉位置合适并且无“in-out-in”现象后,缝合切口。

1.3. 术后处理

两组术后处理一致。术后常规应用抗生素预防感染,低分子肝素预防下肢深静脉血栓形成。术后无需外固定或牵引,第2天开始指导患者下肢功能锻炼,行卧床患肢等长等张肌肉收缩锻炼、踝泵锻炼,可扶拐患肢无负重下地,待X线片复查示骨折愈合后开始逐渐负重。

1.4. 疗效评价指标

记录两组手术时间、术中出血量(纱布及负压吸引器吸血量之和)、住院时间及末次随访时髋关节Harris评分。

术后行股骨正侧位X线片检查,观测以下指标。① 术后5 d内基于Garden对线指数评价骨折复位质量,分为4级。Ⅰ级,正位片上股骨干内缘与股骨头内侧压力骨小梁夹角达160°,侧位片上股骨头轴线与股骨颈轴线呈一直线(180°);Ⅱ级,正位155°,侧位180°;Ⅲ级,正位<155°或者侧位>180°;Ⅳ级,正位150°,侧位>180°。② 术后1年颈干角(正位片上股骨干纵轴线与股骨颈轴线夹角)、股骨颈长度(正位片上股骨头顶点至大、小转子连线中心距离),计算上述两指标健、患侧差值,分别表示颈干角变化、股骨颈短缩程度。③ 随访期间观察内固定失败、股骨头坏死发生情况。内固定失败标准:内翻角>10°、骨折移位>5 mm、股骨颈短缩>10 mm。④ 观察骨折愈合情况及时间。骨折愈合标准:骨折线模糊、有连续骨痂通过骨折线。⑤ 观察有无退钉发生,并测算螺钉回退距离(术后5 d内及1年正位片上螺钉尾部至外侧皮质距离的差值)。

1.5. 统计学方法

采用SPSS26.0统计软件进行分析。计量资料行正态性检验,如符合正态分布,数据以均数±标准差表示,组间比较采用独立样本t检验;不符合正态分布,数据以M(Q1,Q3)表示,组间比较采用Wilcoxon秩和检验。计数资料以率表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。等级资料组间比较采用Wilcoxon秩和检验。检验水准α=0.05。

2. 结果

两组手术时间、住院时间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);但试验组术中出血量少于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。两组患者均获随访,随访时间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);末次随访时试验组Harris评分高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。见表2。

表 2.

Comparison of relevant indexes of effectiveness between the two groups

两组手术疗效相关指标比较

| 项目 Item |

试验组(n=74) Trial group (n=74) |

对照组(n=78) Control group (n=78) |

统计值 Statistic |

| 手术时间 [ M( Q1, Q3),min] | 60(50,85) | 60(47,89) |

Z=–0.033 P=0.973 |

| 术中出血量 [ M( Q1, Q3),mL] | 20.0(20.0,42.5) | 30.0(20.0,50.0) |

Z=–3.328 P=0.001 |

| 住院时间 [ M( Q1, Q3),d] | 11(9,15) | 12(10,15) |

Z=–1.930 P=0.054 |

| 骨折复位质量 [例(%)] | |||

| Ⅰ级 | 53(71.62) | 54(69.23) | χ2=0.333 |

| Ⅱ级 | 20(27.03) | 22(28.21) | P=0.945 |

| Ⅲ级 | 1(1.35) | 2(2.56) | |

| Ⅳ级 | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

骨折愈合时间( , 周) , 周) |

17.0±2.0 | 19.0±2.3 |

t=5.762 P<0.001 |

随访时间( , 周) , 周) |

24.11±4.04 | 24.10±4.42 |

t=–0.027 P=0.979 |

| 螺钉回退 [例(%)] | 3(4.05) | 9(11.54) |

χ2=2.925 P=0.087 |

| 螺钉回退距离 [ M( Q1, Q3),mm] | 3.00(3.00,5.00) | 6.00(5.00,6.00) |

Z=–1.970 P=0.049 |

颈干角变化( , °) , °) |

4.35±2.42 | 5.68±2.91 |

t=3.050 P=0.003 |

股骨颈短缩( , mm) , mm) |

3.54±1.54 | 4.04±1.51 |

t=2.017 P=0.046 |

| 术后Harris评分 [ M( Q1, Q3)] | 93.0(89.0,95.3) | 90.0(88.0,95.0) |

Z=–2.617 P=0.009 |

| 并发症 [例(%)] | |||

| 内固定失败 | 4(5.41) | 14(17.95) |

χ2=5.723 P=0.017 |

| 骨不连 | 6(8.11) | 7(8.97) |

χ2=0.058 P=0.081 |

| 股骨头坏死 | 2(2.70) | 5(6.41) |

χ2=1.188 P=0.443 |

| 股骨颈短缩 | 4(5.41) | 12(15.38) |

χ2=4.015 P=0.045 |

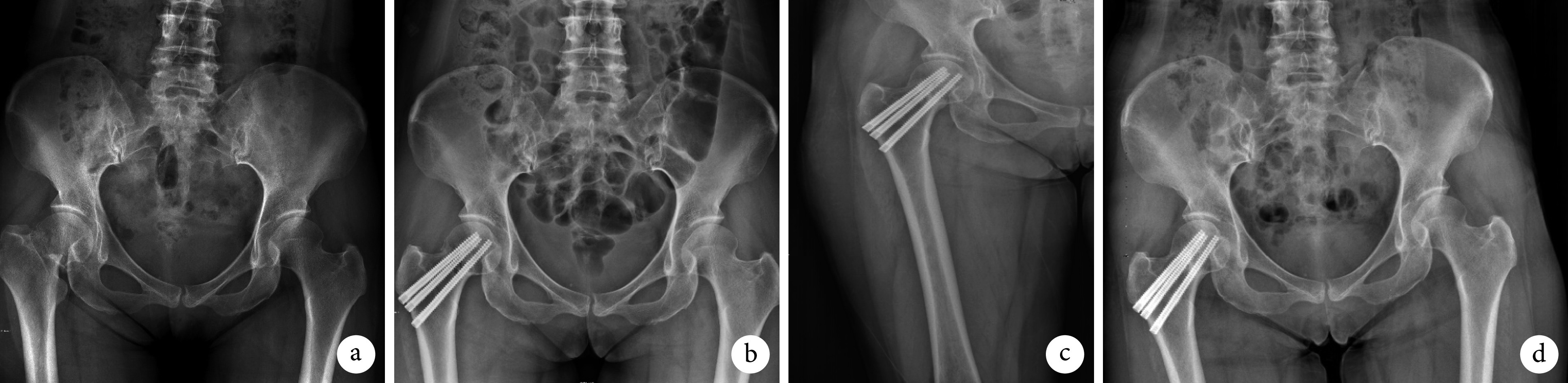

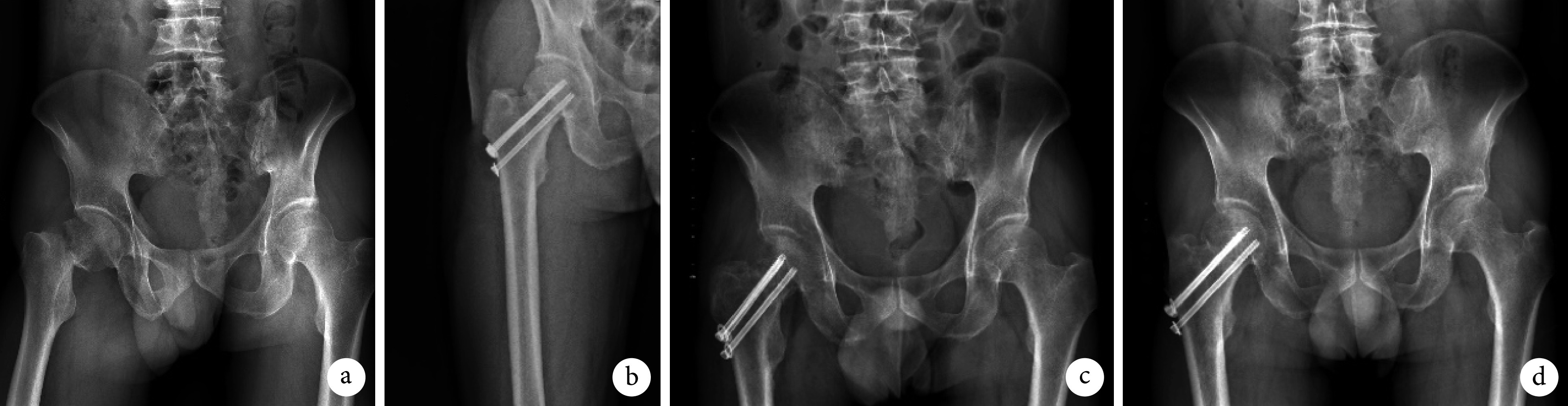

术后影像学复查示,两组骨折复位质量及骨不连发生率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);但试验组骨折愈合时间较对照组缩短,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。两组螺钉回退发生率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);但试验组螺钉回退距离小于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。试验组股骨颈短缩发生率及短缩程度、颈干角变化亦小于对照组,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05)。试验组内固定失败发生率低于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);但两组股骨头坏死发生率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),股骨头坏死患者均行人工全髋关节置换术或人工股骨头置换术治疗。见表2及图1、2。

图 1.

X-ray films of a 53-year-old female patient with right femoral neck fracture (Garden type Ⅳ, Pauwels type Ⅲ) in the trial group

试验组患者,女,53岁,右股骨颈骨折(Garden Ⅳ型、Pauwels Ⅲ型)X线片

a. 术前骨盆正位片;b. 术后1 d骨盆正位片;c. 术后9个月股骨正位片;d. 术后15个月骨盆正位片

a. Preoperative anteroposterior view of the pelvis; b. Anteroposterior view of the pelvis at 1 day after operation; c. Anteroposterior view of the femur at 9 months after operation; d. Anteroposterior view of the pelvis at 15 months after operation

图 2.

X-ray films of a 57-year-old male patient with right femoral neck fracture (Garden type Ⅳ, Pauwels type Ⅲ) in the control group

对照组患者,男,57岁,右股骨颈骨折(Garden Ⅳ型、Pauwels Ⅲ型)X线片

a. 术前骨盆正位片;b. 术后1 d股骨正位片;c. 术后5个月骨盆正位片;d. 术后12个月骨盆正位片

a. Preoperative anteroposterior view of the pelvis; b. Anteroposterior view of the femur at 1 day after operation; c. Anteroposterior view of the pelvis at 5 months after operation; d. Anteroposterior view of the pelvis at 12 months after operation

3. 讨论

股骨颈骨折常用内固定方法包括空心螺钉、股骨颈动力交叉钉系统、动力髋螺钉、髓内钉和股骨近端锁定钢板等[6-9]。3枚空心螺钉平行固定是经典内固定方式,通过轴向动态加压方式促进骨折愈合,具有保护血供、滑动加压、微创等优势[10-11]。然而,空心螺钉内固定术后股骨颈短缩、内固定失败等问题不可忽略。本研究中也发现同样问题,部分螺纹空心螺钉固定术后并发症明显多于全螺纹空心加压螺钉。基于此,越来越多学者尝试新的内固定方式。

全螺纹空心螺钉诞生于20世纪90年代,目前临床上有两种用于治疗股骨颈骨折的全螺纹螺钉,一种是普通头、圆柱形、等距的全螺纹空心螺钉,另一种是无头、锥形、不等距的全螺纹空心加压螺钉,两者固定机制有明显差异[12]。前者是一种非滑动、长度稳定的内固定物,不能起到拉力螺钉作用,也没有滑动加压作用。因此,由于骨吸收或骨折复位不良,术后可能会出现内固定失败、骨不连等并发症,尤其是固定粉碎性骨折时。而后者具有锥形轮廓和可变螺距,锥形轮廓使螺钉获得更多骨质支持以及更大压缩和拔出强度;可变螺距设计使螺纹螺距从头部到尾部逐渐变小,螺钉头部进入骨质速度比尾部快,从而在螺钉推进过程中对骨折面进行加压[13-14]。

既往相关临床研究样本量较少,本研究在扩大病例数的基础上,延长了随访时间,以期更全面地评估全螺纹空心加压螺钉固定股骨颈骨折的有效性。结果显示全螺纹空心加压螺钉固定明显减少了骨折愈合时间以及内固定失败、股骨颈短缩发生,我们认为这可能与该螺钉可变螺距和锥形轮廓设计特点有关。生物力学研究表明,采用全螺纹空心加压螺钉代替部分螺纹空心螺钉显著减少了骨折塌陷发生,在干骺端和股骨颈使用增加螺纹的螺钉可以防止股骨颈短缩和骨不连发生。Downey等[15]的生物力学研究发现全螺纹空心螺钉在抗剪切方面优于部分螺纹空心螺钉,并在初始固定强度和抗股骨颈短缩方面表现优越。Parker等[16]报道采用长螺纹空心松质螺钉治疗股骨颈骨折,术后骨不连发生率降低。Schaefer等[17]报道使用全螺纹加压空心螺钉替代后方部分螺纹空心螺钉,可以显著增加固定强度,减少骨折移位。全螺纹空心加压螺钉在固定股骨颈骨折方面,尤其是在高能量骨折中,比传统部分螺纹空心螺钉固定更具优势[18]。

结合本研究分析结果,我们认为全螺纹空心加压螺钉与部分螺纹空心螺钉相比,具有以下优势:① 全螺纹空心加压螺钉固定使骨折端处于绝对稳定状态。全螺纹空心加压螺钉螺纹增加了与骨质的接触,尾端螺纹加强了对股骨干外侧皮质的把持,中部螺纹增加了对股骨颈周围骨质的切割,固定后股骨颈处于稳定状态,为骨折愈合创造了良好条件。② 全螺纹空心加压螺钉固定因其为非滑动加压机制,有效避免了滑动加压导致的股骨颈短缩、螺钉退出,从而确保股骨颈长度得以维持。③ 全螺纹空心加压螺钉的埋头设计降低了退钉后尾帽对软组织和皮肤的激惹,减少了相关并发症发生。此外,该类螺钉无需全部拧入,也不需要特别平行植入,操作更简便。④ 全螺纹空心加压螺钉阻止骨折端滑动同时,也可以有效抵抗剪切力。

综上述,相比于部分螺纹空心螺钉,全螺纹空心加压螺钉可有效维持骨折复位,避免股骨颈短缩、内固定失败发生,是治疗股骨颈骨折的一个较好选择。

利益冲突 在课题研究和文章撰写过程中不存在利益冲突

伦理声明 研究方案经大连医科大学附属第二医院伦理委员会批准(2022第112号)

作者贡献声明 季仁晨:起草文章,统计并分析数据;潘德悦:手术方案制定及手术实施,并对文章的知识性内容作批评性审阅;卢星华:手术实施及临床资料收集;丛日成:数据收集整理

References

- 1.Haubruck P, Heller RA, Tanner MC Femoral neck fractures: Current evidence, controversies and arising challenges. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2020;106(4):597–600. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linde F, Andersen E, Hvass I, et al Avascular femoral head necrosis following fracture fixation. Injury. 1986;17(3):159–163. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(86)90322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer H, Maleitzke T, Eder C, et al. Management of proximal femur fractures in the elderly: current concepts and treatment options. Eur J Med Res, 2021, 26(1): 86. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00556-0.

- 4.Würdemann FS, Voeten SC, Krijnen P, et al Variation in treatment of hip fractures and guideline adherence amongst surgeons with different training backgrounds in the Netherlands. Injury. 2022;53(3):1122–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2021.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.潘德悦, 韩鑫, 赵文志 全螺纹空心加压螺钉内固定治疗股骨颈骨折. 创伤外科杂志. 2019;21(1):72–73. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-4237.2019.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalifa AA, Ahmed EM, Farouk OA. Surgical approaches for managing femoral head fractures (FHFs); What and how to choose from the different options? Orthop Res Rev, 2022, 14: 133-145.

- 7.Li L, Zhao X, Yang X, et al. Dynamic hip screws versus cannulated screws for femoral neck fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res, 2020, 15(1): 352. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01842-z.

- 8.Li J, Wang M, Zhou J, et al Finite element analysis of different screw constructs in the treatment of unstable femoral neck fractures. Injury. 2020;51(4):995–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang Y, Zhang Z, Wang L, et al. Femoral neck system versus inverted cannulated cancellous screw for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in adults: a preliminary comparative study. J Orthop Surg Res, 2021, 16(1): 504. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02659-0.

- 10.Hu H, Cheng J, Feng M, et al. Clinical outcome of femoral neck system versus cannulated compression screws for fixation of femoral neck fracture in younger patients. J Orthop Surg Res, 2021, 16(1): 370. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02517-z.

- 11.Sundkvist J, Brüggeman A, Sayed-Noor A, et al. Epidemiology, classification, treatment, and mortality of adult femoral neck and basicervical fractures: an observational study of 40, 049 fractures from the Swedish Fracture Register. J Orthop Surg Res, 2021, 16(1): 561. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02701-1.

- 12.Yuan KX, Yang F, Fu K, et al. Internal fixation using fully threaded cannulated compression screws for fresh femoral neck fractures in adults. J Orthop Surg Res, 2022, 17(1): 108. doi: 10.1186/s13018-022-03005-8.

- 13.Shin KH, Hong SH, Han SB Posterior fully threaded positioning screw prevents femoral neck collapse in Garden Ⅰ or Ⅱ femoral neck fractures. Injury. 2020;51(4):1031–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang JZ, Xiao YP, Li L, et al. The efficacy of dynamic compression locking system vs. dynamic hip screw in the treatment of femoral neck fractures: a comparative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2022, 23(1): 661. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05631-z.

- 15.Downey MW, Kosmopoulos V, Carpenter BB Fully threaded versus partially threaded screws: Determining shear in cancellous bone fixation. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2015;54(6):1021–1024. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker MJ, Ali SM Short versus long thread cannulated cancellous screws for intracapsular hip fractures: a randomised trial of 432 patients. Injury. 2010;41(4):382–384. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaefer TK, Spross C, Stoffel KK, et al Biomechanical properties of a posterior fully threaded positioning screw for cannulated screw fixation of displaced neck of femur fractures. Injury. 2015;46(11):2130–2133. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weil YA, Qawasmi F, Liebergall M, et al Use of fully threaded cannulated screws decreases femoral neck shortening after fixation of femoral neck fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018;138(5):661–667. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]