Abstract

Regulated antigen expression can influence the immunogenicity of live recombinant Salmonella vaccines, but a rational optimization has remained difficult since important aspects of this effect are incompletely understood. Here, attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 strains expressing the model antigen GFP_OVA were used to quantify in vivo antigen levels by flow cytometry and to simultaneously follow the crucial early steps of antigen-specific T-cell responses in mice that are transgenic for a T-cell receptor recognizing ovalbumin. Among seven tested promoters, PpagC has the highest activity in murine tissues combined with low in vitro expression, whereas Ptac has a comparable in vivo and a very high in vitro activity. Both SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) and SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA) cells can induce potent ovalbumin-specific cellular immune responses following oral administration, but doses almost 1,000-fold lower are sufficient for the in vivo-inducible construct SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) compared to SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA). This efficacy difference is largely explained by impaired early colonization capabilities of SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA) cells. Based on the findings of this study, appropriate in vivo expression levels for any given antigen can be rationally selected from the increasing set of promoters with defined properties. This will allow the improvement of recombinant Salmonella vaccines against a wide range of pathogens.

Recombinant live Salmonella sp. strains that express foreign antigens are promising oral vaccines (6, 30, 41). Among the many parameters that have been shown to influence their efficacy, regulated antigen expression appears to have particularly strong effects (3, 4, 9, 10, 19, 26, 32, 34, 35, 37, 39, 43). In vivo-inducible (IVI) instead of constitutive antigen expression allows the culture and administration of recombinant Salmonella cells expressing low levels of antigen that minimally interfere with bacterial viability. Once the Salmonella cells reach immunocompetent sites within the host, IVI promoters are thought to upregulate antigen expression, resulting in an efficient immune response. This general concept has been validated with a number of studies demonstrating an enhanced stability of IVI expression plasmids and an increase in immunogenicity of recombinant live Salmonella cells. However, several important aspects are still unclear, which impairs a rational optimization of IVI antigen expression.

Extensive data on Salmonella gene expression are available for in vitro conditions and cell culture infection models (15, 31), but quantitative data on in vivo gene expression in host tissues are largely lacking (29). Salmonella gene expression in cell culture models strongly depends on the host cell type that is infected (7), suggesting that gene expression in complex host tissues with potentially many different infected cell types might be difficult to predict based on cell culture data. Without quantitative data on in vivo antigen expression levels, the relationship between promoter choice and the immunogenicity of Salmonella strains is difficult to understand and a rational selection of an optimal promoter is impossible.

Various studies investigated the effect of differential antigen expression in recombinant Salmonella strains on humoral immune responses following immunization. In contrast, cellular immune responses have been rarely investigated, although such responses are crucial for protective immunity against a wide range of pathogens (40) and are more likely to be induced by Salmonella vaccines than are humoral responses (44). Humoral and cellular responses against Salmonella antigens can differ in strength, as is illustrated by the flagellar filament protein FliC, which is a dominant T-cell antigen (13, 33) but a very weak B-cell antigen (17) in orally infected mice. A more detailed analysis of cellular responses is required to assess the full potential of IVI expression in recombinant Salmonella strains and to determine what properties an optimal IVI expression system should have.

In most studies that compare immunization efficacies for different recombinant Salmonella strains, host immune responses are analyzed for one particular inoculum size. This approach reveals strong differences in immunogenicity but yields no data on the minimum dose that is required to induce an efficient immune response. Adverse effects generally increase with higher vaccine doses, and this is also true for Salmonella-based vaccines (6, 44, 45). Hence, it is especially important to aim for Salmonella constructs that induce sufficient responses at a low inoculum size. Dose-response curves are required to determine how well various strains fulfill this goal and what property of the expression system is especially relevant for optimization.

In this study, the in vitro and in vivo expression levels of several promoters in recombinant Salmonella strains were determined using a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-linked model antigen and two-color flow cytometry (5). The in vivo induction of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells following oral immunization with Salmonella strains was characterized using a transgenic T-cell receptor (tgTCR) mouse model which recognizes the same GFP-linked antigen (5). For two Salmonella strains with differential antigen expression, dose-response curves were determined for the specific induction of T cells in relation to the inoculum size. The results demonstrate a very strong impact of regulated antigen expression on immunogenicity that can be almost entirely explained by differential colonization capabilities of the Salmonella strains. An increasing set of promoters with defined in vivo properties allows the selection of appropriate expression levels for nontoxic and toxic antigens. This rational approach to optimizing antigen expression for efficient cellular immune responses will help develop efficacious Salmonella-based vaccines against a wide range of infectious diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of recombinant Salmonella strains.

To characterize various promoters for antigen expression in Salmonella cells, the corresponding fragments were amplified from genomic DNA of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium wild-type strain SL1344 (27) by PCR using the primers summarized in Table 1. The PCR fragments were digested with BamHI and XbaI and exchanged for the Ptac promoter in pPtacGFP_OVA (identical to pGFP_OVA [5]), which encodes a fusion gene of the GFP and a 25-amino-acid fragment of ovalbumin, ESLKISQAVHAAHAEINEAGREVVG, which contains a dominant H-2d-restricted 17-mer T-cell epitope together with the 4 adjacent amino acids on both the N and the C termini. The resulting plasmids (designated “pPxxxGFP_OVA”) were sequenced to verify the identity of the cloned promoters and electroporated into S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA SL3261 cells (27). Transformants were selected on plates containing streptomycin (90 μg ml−1) and ampicillin (100 μg ml−1).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Nucleotide sequencea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SpvA_1 | 5′-CGGGATCCGCTGAACGTTGTTTATTC | 23 |

| SpvA_2 | 5′-GCTCTAGATAAATAATGATGACTCCTGA | 23 |

| SsaH_1 | 5′-CGCGGATCCAATATTCGGTAGATTAGCCTTAAC | 47 |

| SsaH_2 | 5′-GCTCTAGAAATGCTTTTCCTTAAAATA | 47 |

| PagC_1 | 5′-CGGGATCCGTTAACCACTCTTAATAATAATG | 4 |

| PagC_2 | 5′-GCTCTAGATACTACTTATTATTTACG | 4 |

| PhoP-1_1 | 5′-CGGGATCCTGACTCTGGTCGACGAACTTA | 42 |

| PhoP-1_2 | 5′-GCTCTAGATAGCGTTGATTATGGTG | 42 |

| PhoP_1b | 5′-CGGGATCCTGACTCTGGTCGACGAACTTA | 42 |

| PhoP_2 | 5′-GCTCTAGATGTGTTAACAATAAGAACAGTCTA | 42 |

| OmpC_1 | 5′-CGGGATCCTAAACAGACATTCAGAAGTGAATG | 4 |

| OmpC_2 | 5′-GCTCTAGAATATGCCTTTATTGCTTTTTTATG | 4 |

Restriction enzyme sites are underlined.

Identical to PhoP-1_1.

Mice, adoptive transfer, and immunization.

Female 8- to 12-week-old BALB/c mice were obtained from the Bundesamt für gesundheitlichen Verbraucherschutz und Veterinärmedizin, Berlin, Germany, and were kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions in full accordance with the German guidelines for animal care. All experiments were approved by the local Animal Welfare Committee.

Ammonium chloride-treated splenocytes from 8- to 12-week-old female DO11.10 × BALB/c crosses were transferred by tail vein injection into sex- and age-matched BALB/c recipient mice (4 × 106 tgTCR CD4+ T cells per recipient mouse) and immunized 1 day later. For oral immunization, an overnight culture of recombinant Salmonella was diluted 1:8 in fresh Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and grown to the late logarithmic growth phase at 37°C and 200 rpm. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min, washed in LB medium containing 3% NaHCO3, and resuspended in the same medium to 5 × 107 to 5 × 1011 CFU ml−1, and 100-μl doses were intragastrically administered to chimeric mice with a round-tip stainless steel needle.

Flow cytometry of bacteria and T cells.

At various time intervals postimmunization (p.i.), mice were anesthetized and killed. Single-cell suspensions of spleens, mesenteric lymph nodes, and the Peyer's patches were prepared. To measure the in vivo expression of GFP_OVA in recombinant Salmonella cells, the tissue samples were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 and analyzed for scattering properties and green and orange fluorescence using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) as described (5). Flow cytometric GFP data were converted to numbers of GFP_OVA molecules per bacterium using a factor obtained from Salmonella in vitro cultures that express spectroscopically determined amounts of GFP (5). The number of CFU was determined by plating serial dilutions, and the extent of plasmid loss was analyzed by replica plating on media with or without ampicillin. To obtain the total in situ amounts of GFP_OVA, the number of plasmid-containing CFU was multiplied with the mean number of GFP_OVA molecules per bacterium.

To characterize the ovalbumin-specific CD4+ T-cell activation, single-cell suspensions of Peyer's patches, mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleens were stained with biotinylated anti-tgTCR clonotype-antibody KJ1-26, anti-CD4-fluorescein, anti-CD69-phycoerythrin, and anti-B220-allophycocyanin, followed by streptavidin-FarRed (Gibco), and analyzed with a Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). CD4+ tgTCR+ B220− lymphocytes were analyzed for their forward scatter and CD69 expression as described (5).

RESULTS

Differential regulation of seven selected promoters in vitro and in vivo.

Seven promoters were selected for antigen expression in Salmonella cells. PspvA, PpagC, and PphoP were selected since antigen expression from these promoters has previously been shown to result in efficient humoral immune responses (4, 19, 26, 32, 34). PphoP actually consists of two promoters, the inducible PphoP-1 and the constitutive PphoP-2 (42). PphoP-1 has not previously been tested for antigen expression, but it could be a superior IVI promoter compared to complete PphoP. PssaH from the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 is another promoter with potentially attractive IVI properties (47) that has not previously been tested for antigen expression. PompC is supposedly active early during infection but is rather ineffective for humoral immune responses (4). Finally, the artificial Ptac was used as a non-IVI reference promoter, since it is a commonly used promoter for constitutive expression in recombinant Salmonella (14, 22, 43, 48, 51). Moreover, antigen expression from Ptac has been successfully used to induce specific CD4+ T-cell responses in a tgTCR mouse model (see below) following oral immunization with recombinant Salmonella cells (5).

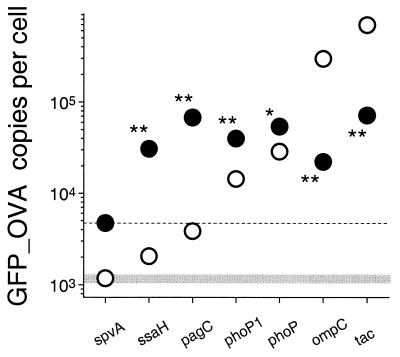

Each of the seven promoters was cloned on a medium-copy-number plasmid upstream of gfp_ova which encodes a model antigen consisting of the GFP and a C-terminally fused T-cell epitope from ovalbumin (5). The GFP part of this model antigen allows the quantification of the antigen expression levels in host tissues by a two-color flow-cytometric technique. The immunodominant major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted ovalbumin epitope allows the study of the early steps of specific CD4+ T-cell induction with a widely used tgTCR mouse model (38). Hence, this model antigen makes it possible to directly relate the local Salmonella antigen expression with the induction of cellular immune responses. Attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA SL3261 cells (27) carrying either of the expression plasmids were grown in liquid cultures in LB medium to the late logarithmic growth phase, and GFP_OVA expression was determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 1). The same cultures were then used to orally inoculate mice. Five days later, mice were sacrificed and Triton-treated Peyer's patches homogenates were analyzed for GFP-expressing Salmonella cells by two-color flow cytometry (Fig. 1). Under the in vitro conditions used, fewer than 4,000 GFP_OVA copies per cell are expressed from PspvA, PssaH, and PpagC. Among these three promoters with attractive low in vitro activities, PpagC has the highest in vivo activity (about 90,000 copies per cell), while the activity of PspvA is below the in vivo detection limit of the flow cytometric technique. PphoP-1 and the complete PphoP have quite high in vivo expression levels of 40,000 and 55,000 copies per cell, respectively, but their in vitro activities are also rather high (PphoP-1, ca. 15,000 copies; PphoP, ca. 35,000 copies) with the expected higher induction rate for PphoP-1. The in vitro activity of PphoP and PphoP-1 is lower during the late logarithmic growth phase compared to exponential growing bacteria, in agreement with previous in vitro studies for PhoP-dependent promoters in wild-type Salmonella cells (42). In contrast to the other five promoters, PompC and Ptac have very high in vitro activities (270,000 and 600,000 copies, respectively) and are strongly down-regulated in vivo (20,000 and 85,000 copies, respectively). Despite this strong repression, the in vivo expression levels from Ptac are still comparable to those of the strongest IVI promoter investigated in this study (PpagC).

FIG. 1.

Salmonella GFP_OVA expression from different promoters in vitro during late-logarithmic growth (○) and in vivo in murine Peyer's patches 5 days after oral immunization with 3 × 109 CFU (●). The in vitro data represent averages from two in vitro cultures. The in vivo data represent averages of arithmetic means for Salmonella GFP_OVA expression from four to five mice. The standard deviation was always smaller than 15%. Statistical differences between in vitro and in vivo activities were analyzed using the t test (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.001). The dashed line represents the detection limit for in vivo measurements, and the shaded box represents background fluorescence of in vitro cultures.

Among the seven tested promoters, PpagC has the highest in vivo activity and a rather low in vitro activity, suggesting that it is an appropriate prototype IVI promoter for studying the effect of regulated antigen expression on the immunogenicity of recombinant Salmonella vaccines. Therefore, the strain SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) was selected for further characterization.

Colonization, in situ antigen expression, and specific T-cell induction of SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA).

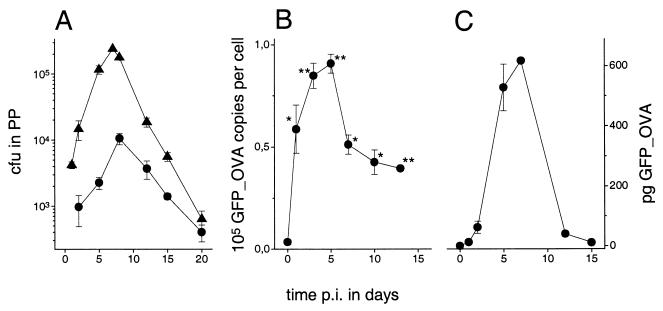

Following oral administration to mice, SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells exponentially proliferate in the Peyer's patches to reach a peak colonization at day 7 p.i., after which they are progressively cleared (Fig. 2A). A similar kinetic but much lower peak colonization was observed in the mesenteric lymph nodes (Fig. 2A), whereas only a few hundred bacteria colonize the spleen (data not shown). This colonization pattern is similar to what has been previously observed for other SL3261 constructs (18).

FIG. 2.

Colonization and GFP_OVA expression of SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells after oral administration to mice. (A) Colonization of Peyer's patches (PP) (▴) and mesenteric lymph nodes (●). More than 95% of the clones recovered at day 20 p.i. retained the expression plasmid as determined from plating with and without antibiotic selection. (B) GFP_OVA expression in the Peyer's patches. Statistical differences for comparison to in vitro expression levels in the inocula were analyzed using the t test (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.001). (C) Total in situ amount of GFP_OVA as calculated from CFU numbers and expression levels. In all panels, error bars show standard errors of the means.

More than 95% of the Salmonella clones that were recovered ex vivo at 20 days p.i. retained the expression plasmid as determined by replica plating on media with or without ampicillin. This high plasmid stability suggests that SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells have no major colonization disadvantage compared to the carrier strain SL3261. To directly test this hypothesis, defined mixtures of SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) and SL3261 cells were orally administered, and 7 days later, the numbers of plasmid-containing and plasmid-free clones in the Peyer's patches were determined. Compared to the initial ratio in the inoculum, SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells were underrepresented by a factor (competitive index) of 0.5 ± 0.2 (mean ± standard error of the mean) after 7 days of competitive in vivo growth, which is equivalent to an average difference in growth rates of 10% ± 4% based on the apparent in vivo division time of about 24 h (see below). This confirms that in vivo GFP_OVA expression from PpagC causes only a minor additional attenuation of SL3261 cells.

The in situ GFP_OVA expression of SL3261 (pPpagC GFP_OVA) cells in the Peyer's patches (Fig. 2B) and mesenteric lymph nodes (not shown) was quantified using two-color flow cytometry. Consistent with the initial characterization (Fig. 1), antigen expression is low in the inoculum but becomes highly induced in vivo. Based on the colonization data and the expression levels, the total amount of antigen that is produced in the colonized tissues was calculated (Fig. 2C).

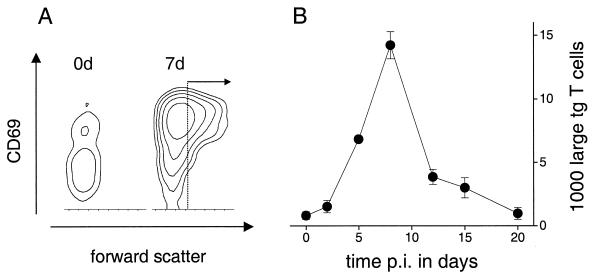

To characterize the crucial early steps of the induction of antigen-specific T cells following oral immunization with recombinant Salmonella, a widely used tgTCR adoptive transfer model (38) was used as recently described (5). In this system, a few million tg CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 mice (36) that specifically recognize an epitope from ovalbumin (amino acids 323 to 339) are transferred into syngeneic, non-tg BALB/c mice. In the chimeric mice, the small fraction of tg T cells can be detected with a clonotypic monoclonal antibody (25) and phenotypically characterized using four-color flow cytometry. Following oral immunization of chimeric mice with SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells that express the recognized ovalbumin epitope as a C-terminal fusion to GFP (see above), many of the initially resting ovalbumin-specific tg T cells in the Peyer's patches become strongly activated as shown by the upregulation of the very early activation marker CD69 and the enhanced forward scatter indicating a size increase (Fig. 3A). This activation is antigen-specific since no detectable activation occurs following oral immunization with control Salmonella strains not expressing the recognized ovalbumin epitope (not shown). Much weaker specific responses were detected in the mesenteric lymph nodes and the spleen (not shown). The total number of activated ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches (Fig. 3B) was calculated based on the total number of lymphocytes in the tissue samples and the fraction of large tg CD4+ T cells (gated as in Fig. 3A). Antigen-specific T-cell activation in the Peyer's patches followed rather closely the amount of locally produced antigen (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 3.

Activation of ovalbumin-specific T-cell receptor tg CD4+ T cells following oral immunization with 109 SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells. (A) Contour diagrams of flow cytometric data for forward scatter and CD69 expression of the tg T cells in Peyer's patches prior to and 7 days after immunization. (B) Number of large tg T cells (gated as shown in panel A) in the Peyer's patches at different times p.i. Error bars, standard errors of the means.

Quantitative comparison of PpagC and Ptac.

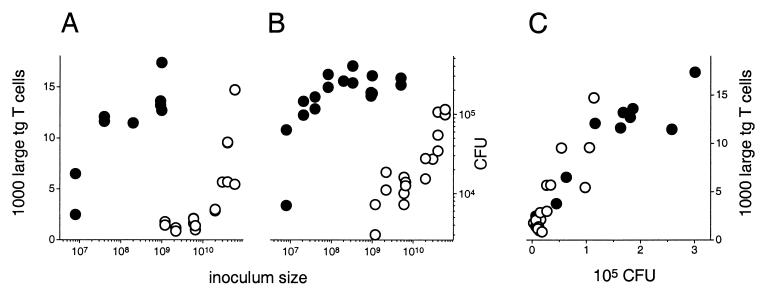

To investigate the effect of regulated antigen expression on the efficacy of recombinant Salmonella vaccines, the prototype IVI Salmonella strain SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) was compared to the strain SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA) in which the common constitutive promoter Ptac instead of PpagC drives antigen expression. Both strains induce potent ovalbumin-specific CD4+ T-cell responses in the Peyer's patches following oral administration, but such responses require a dose of SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA) cells almost 1,000-fold larger than that of SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells, indicating an enormous difference in efficacy between these two strains (Fig. 4A). The peak numbers of large tg T cells were lower in this study compared to previous data (ca. 12,000 compared to ca. 35.000 [5]). These numbers are calculated form the total number of Peyer's patch lymphocytes, the fraction of tg T cells, and the proportion of large activated tg T cells. The lower numbers in this study are mainly caused by the presence of fewer lymphocytes due to smaller Peyer's patches (peak numbers 30 to 35 million instead of 60 to 70 million) and somewhat fewer tg T cells, whereas the proportion of large activated tg T cells (maximum, 40%) is similar in both studies. The difference in Peyer's patch sizes was most likely due to variations between the mouse batches that were used in the two studies and did not affect the interpretation of the data, as all comparative experiments of this study were done with the same batch of mice for both Salmonella strains.

FIG. 4.

Quantitative comparison of immunogenicity and colonization of SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells (●) and SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA) cells (○). (A) Number of activated large ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches 7 days after oral immunization with different doses. (B) Colonization levels in Peyer's patches 7 days after immunization with different doses. (C) Relationship between colonization levels and the ovalbumin-specific T-cell response in Peyer's patches 7 days after oral immunization.

Peak colonization levels at day 7 after oral administration are also strikingly different for the two strains (Fig. 4B), with a dose dependency similar to that observed for the cellular host responses (Fig. 4A), suggesting that differential colonization capabilities may contribute to the efficacy difference. To validate this hypothesis, the CD4+ T-cell responses in the Peyer's patches were plotted against the local colonization levels of the two strains (Fig. 4C). There is a clear dose-response relationship for both strains, with stronger T-cell responses at higher colonization levels (for SL3261 [pPtacGFP_OVA], R = 0.86, P < 0.001; for SL3261 [pPpagCGFP_OVA], R = 0.90, P < 0.001), indicating a strong correlation of Salmonella colonization capabilities and immunogenicity. Moreover, both strains induce similar T-cell responses when equivalent colonization levels are compared, indicating that differential colonization explains most of the efficacy difference while other factors appear to be of minor importance.

To further characterize the growth characteristics of the two strains, in vitro and in vivo division times were determined. Despite the strong difference of in vitro antigen expression levels (Fig. 1), both strains have similar division times during exponential growth in liquid cultures (for SL3261 [pPpagCGFP_OVA], 35 ± 5 min; for SL3261 [pPtacGFP_OVA], 42 ± 5 min). The apparent in vivo division times in colonized Peyer's patches that are the net results of proliferation, killing, and migration (28) are also similar (for SL3261 [pPpagCGFP_OVA], 24 ± 7 h; for SL3261 [pPtacGFP_OVA], 24 ± 12 h [both values calculated from the colonization levels in the Peyer's patches 2 and 5 days after oral administration]).

DISCUSSION

IVI antigen expression has been shown to influence the efficacy of recombinant Salmonella vaccines. However, a rational optimization of antigen expression has remained difficult because of the incomplete understanding of several crucial aspects, including the quantitative IVI expression levels, the early inductive steps of cellular immune responses to the foreign antigen, and the effect of IVI antigen expression on the minimum effective vaccine dose. Here, recently developed methods were used to investigate these aspects to obtain a better basis for rational improvements of Salmonella-based vaccines.

To understand the effect of regulated antigen expression on efficacy, a quantitative determination of in vivo expression levels is required. This has been a difficult task because of technical problems, but recently, a two-color flow-cytometric technique has been established that allows the measurement of the expression of a model GFP-linked antigen in individual Salmonella cells in colonized host tissues (5). Using this technique, the activities of seven different promoters were measured in attenuated Salmonella cells in vitro and in vivo in the Peyer's patches of orally inoculated mice. Additional promoters are currently being screened by the same approach. The increasing set of promoters with defined properties makes it possible to rationally select appropriate expression levels for foreign antigens. Among the currently characterized promoters, PpagC has particularly attractive properties, i.e., low in vitro activity and high in vivo activity, which might explain the strong humoral immune responses that have been obtained for various Salmonella constructs using this promoter (4, 19, 26, 34). PssaH that had not been previously tested for antigen expression in Salmonella strains has attractive induction properties, but its in vivo activity is lower than that of PpagC. While PssaH might be less well-suited for nontoxic antigens like the GFP-linked model antigen, this promoter might be particularly attractive for somewhat-toxic antigens that cannot be expressed at higher levels (see below). Some other promoters with unfavorably high in vitro activities could be down-regulated using altered culture conditions. For example, PphoP can be repressed by millimolar concentrations of Mg2+ (21), and PompC is less active in media with low osmolarity (20). However, having identified PpagC as an attractive candidate promoter, there was no need to specially adapt culture conditions for other promoters lacking superior in vivo properties. Moreover, culturing and inoculation in LB medium have been reported to enhance Salmonella invasion compared to phosphate-buffered saline (12), and Salmonella cells grown in the presence of high Mg2+ concentrations have impaired capabilities to survive hostile conditions in the host (21), suggesting that modification of culture conditions could have complex consequences on vaccine properties.

To study the effect of regulated antigen expression on the efficacy of recombinant Salmonella vaccines, mostly humoral immune responses have been analyzed while cellular responses have been largely neglected despite their important role for protective immunity against many important pathogens (40). The crucial early steps of CD4+ T-cell induction are difficult to investigate in normal animals because of the very low precursor frequency of specific T cells. tgTCR mouse models with artificially high frequencies of T cells that recognize a single defined epitope make it possible to follow the early activation of specific CD4+ T cells following immunization (38). This approach has recently been applied to study T-cell responses in mice that have been subcutaneously (11) or orally inoculated (5) with recombinant Salmonella strains expressing ovalbumin. In case of the model antigen GFP_OVA in which the recognized ovalbumin epitope is fused to GFP (5), it is possible to simultaneously measure the antigen expression in colonized host tissues, so that the effect of differential antigen expression on Salmonella vaccine efficacy can be directly assessed. Here, this approach was used to compare the prototype IVI construct SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) with the prototype constitutive construct SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA), in which the widely used Ptac promoter drives antigen expression (14, 22, 43, 49).

Both constructs are capable of inducing potent ovalbumin-specific T-cell responses after oral administration to mice, but there is an enormous difference in efficacy with an ∼1,000-fold-lower minimum effective dose for the IVI construct compared to that of the constitutive construct (Fig. 4A). The minimum effective dose is particularly relevant for vaccine development since the number of live Salmonella cells that can be safely administered is generally limited (46). Therefore, these results demonstrate that regulated antigen expression is of outstanding importance as an optimization parameter for recombinant Salmonella vaccines. In addition, the higher numbers of Salmonella cells in the Peyer's patches that can be obtained with the IVI construct might induce a qualitatively different specific T-cell response. To test this, the cytokine profile of tg T cells following immunization is currently being analyzed.

Several promoter-dependent vaccine properties such as colonization capabilities, in vivo antigen expression levels, Salmonella-host interactions, etc., could contribute to the efficacy difference between the two strains, and the relative importance of these factors is of interest for rational optimization. The two strains have very different colonization capabilities (Fig. 4B), and this affects their efficacy since the T-cell responses closely correlate with colonization levels (Fig. 4C). Much larger inocula are needed for the weakly colonizing constitutive construct SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA) compared to the efficiently colonizing IVI construct SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA). This effect seems to explain most of the efficacy difference, as similar cellular responses are induced when equivalent numbers of Salmonella cells are present in the host tissues (Fig. 4C).

Despite the strongly different colonization capabilities, both strains have similar growth rates in vitro and in vivo from day 2 p.i. Apparently, the poor colonization of the SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA) strain is due to a colonization defect within the first 2 days after administration, such as impaired host tissue invasion and/or early survival in host cells. This early defect could be caused by the very high initial GFP_OVA expression that distinguishes this strain from the efficiently colonizing strain SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) (Fig. 1). While a direct toxic effect of high concentrations of GFP_OVA is unlikely because of the rapid in vitro growth of SL3261 (pPtacGFP_OVA) cells, the allocation of extensive protein resources to GFP_OVA expression might interfere with the need for rapid protein synthesis immediately after host contact (1). Further studies are required to test this hypothesis.

As differential colonization alone explains most of the efficacy difference, other factors seem to be of minor importance. Expression plasmid stability is somewhat lower for the constitutive construct compared to the IVI construct (80% [per reference 5] versus 95%), but this rather small difference probably contributes little compared to the several-log difference in colonization capabilities. In vivo antigen expression levels might influence efficacy, but the present comparison yields no information on this parameter since in vivo expression levels of both strains are comparable (Fig. 1). Another potentially important parameter is the interaction of regulatory networks of Salmonella cells with the promoter that drives antigen expression. Most IVI promoters that have been tested for antigen expression are part of operons encoding Salmonella virulence genes. Providing such promoters on multicopy plasmids might interfere with regulatory networks, resulting in altered Salmonella-host interactions. This could especially apply for PpagC, which is a part of the PhoP/PhoQ regulon that has an important role in Salmonella virulence (2, 24) and modulates antigen presentation of Salmonella-containing macrophages (50). Compared to the artificial Ptac promoter, multicopy PpagC has no detectable effect on the immunogenicity of Salmonella cells that express GFP_OVA once they successfully colonize host tissues (Fig. 4C). Moreover, SL3261 (pPpagCGFP_OVA) cells and SL3261 cells that are devoid of any expression plasmid have similar colonization capabilities. These results suggest that interactions with regulatory networks might be of minor importance for the optimization of promoters for antigen expression.

The information obtained in this study could help to rationally improve antigen expression in recombinant Salmonella vaccines for efficient cellular immune responses. Optimal promoters have low in vitro activities that interfere minimally with early colonization capabilities and have high activities once host tissues are reached to induce an efficient immune response (8, 16, 49). On the other hand, high in vivo expression levels might impair the colonization capabilities because of the metabolic burden and of potential toxic effects of the foreign antigen on Salmonella cells. There is probably a specific optimal in vivo expression level for every antigen depending on its properties. For nontoxic antigens such as GFP_OVA, expression levels of about 90,000 copies per cell do not cause a significant colonization defect. Additional promoter candidates are currently being screened for stronger in vivo activity, exceeding that of PpagC, which might further enhance efficacy for such antigens. On the other hand, somewhat-toxic antigens could require lower in vivo expression levels for optimal efficacy. The increasing set of promoters with defined properties makes it possible to adjust an appropriate in vivo expression level for any foreign antigen. This will help to rationally improve Salmonella-based vaccines against a wider range of infectious diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Thomas F. Meyer, Toni Aebischer, and Simone Spreng for helpful discussions and generous support and Meike Wendland for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant Me705/6-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abshire K Z, Neidhardt F C. Growth rate paradox of Salmonella typhimurium within host macrophages. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3744–3748. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3744-3748.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpuche Aranda C M, Swanson J A, Loomis W P, Miller S I. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson R, Dougan G, Roberts M. Delivery of the pertactin/P.69 polypeptide of Bordetella pertussis using an attenuated Salmonella typhimurium vaccine strain: expression levels and immune response. Vaccine. 1996;14:1384–1390. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullifent H L, Griffin K F, Jones S M, Yates A, Harrington L, Titball R W. Antibody responses to Yersinia pestis F1-antigen expressed in Salmonella typhimurium aroA from in vivo-inducible promoters. Vaccine. 2000;18:2668–2676. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bumann D. In vivo visualization of bacterial colonization, antigen expression, and specific T-cell induction following oral administration of live recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4618–4626. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4618-4626.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bumann D, Hueck C, Aebischer T, Meyer T F. Recombinant live Salmonella spp. for human vaccination against heterologous pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000;27:357–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns-Keliher L, Nickerson C A, Morrow B J, Curtiss R. Cell-specific proteins synthesized by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1998;66:856–861. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.856-861.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardenas L, Clements J D. Stability, immunogenicity and expression of foreign antigens in bacterial vaccine vectors. Vaccine. 1993;11:126–135. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatfield S N, Charles I G, Makoff A J, Oxer M D, Dougan G, Pickard D, Slater D, Fairweather N F. Use of the nirB promoter to direct the stable expression of heterologous antigens in Salmonella oral vaccine strains: development of a single-dose oral tetanus vaccine. Bio/Technology. 1992;10:888–892. doi: 10.1038/nbt0892-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H, Schifferli D M. Enhanced immune responses to viral epitopes by combining macrophage-inducible expression with multimeric display on a Salmonella vector. Vaccine. 2001;19:3009–3018. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00541-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Z M, Jenkins M K. Clonal expansion of antigen-specific CD4 T cells following infection with Salmonella typhimurium is similar in susceptible (Itys) and resistant (Ityr) BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2025–2029. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.2025-2029.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark M A, Hirst B H, Jepson M A. Inoculum composition and Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 regulate M-cell invasion and epithelial destruction by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1998;66:724–731. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.724-731.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cookson B T, Bevan M J. Identification of a natural T cell epitope presented by Salmonella-infected macrophages and recognized by T cells from orally immunized mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:4310–4319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corthésy-Theulaz I E, Hopkins S, Bachmann D, Saldinger P F, Porta N, Haas R, Zheng-Xin Y, Meyer T, Bouzourène H, Blum A L, Kraehenbuhl J P. Mice are protected from Helicobacter pylori infection by nasal immunization with attenuated Salmonella typhimurium phoPcc expressing urease A and B subunits. Infect Immun. 1998;66:581–586. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.581-586.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotter P A, DiRita V J. Bacterial virulence gene regulation: An evolutionary perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:519–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covone M G, Brocchi M, Palla E, Dias da Silveira W, Rappuoli R, Galeotti C L. Levels of expression and immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains expressing Escherichia coli mutant heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:224–231. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.224-231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Almeida M E, Newton S M, Ferreira L C. Antibody responses against flagellin in mice orally immunized with attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains. Arch Microbiol. 1999;172:102–108. doi: 10.1007/s002030050746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunstan S J, Simmons C P, Strugnell R A. Comparison of the abilities of different attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strains to elicit humoral immune responses against a heterologous antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:732–740. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.732-740.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunstan S J, Simmons C P, Strugnell R A. Use of in vivo-regulated promoters to deliver antigens from attenuated Salmonella enterica var. Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5133–5141. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5133-5141.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster J W, Park Y K, Bang I S, Karem K, Betts H, Hall H K, Shaw E. Regulatory circuits involved with pH-regulated gene expression in Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology. 1994;140:341–352. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia V E, Soncini F C, Groisman E A. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell. 1996;84:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez C R, Noriega F R, Huerta S, Santiago A, Vega M, Paniagua J, Ortiz-Navarrete V, Isibasi A, Levine M M. Immunogenicity of a Salmonella typhi CVD 908 candidate vaccine strain expressing the major surface protein gp63 of Leishmania mexicana mexicana. Vaccine. 1998;16:1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grob P, Guiney D G. In vitro binding of the Salmonella dublin virulence plasmid regulatory protein SpvR to the promoter regions of spvA and spvR. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1813–1820. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1813-1820.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groisman E A. The pleiotropic two-component regulatory system PhoP-PhoQ. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1835–1842. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.6.1835-1842.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haskins K, Kubo R, White J, Pigeon M, Kappler J, Marrack P. The major histocompatibility complex-restricted antigen receptor on T cells. I. Isolation with a monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1149–1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.4.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hohmann E L, Oletta C A, Loomis W P, Miller S I. Macrophage-inducible expression of a model antigen in Salmonella typhimurium enhances immunogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2904–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoiseth S K, Stocker B A. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hormaeche C E. The in vivo division and death rates of Salmonella typhimurium in the spleens of naturally resistant and susceptible mice measured by the superinfecting phage technique of Meynell. Immunology. 1980;41:973–979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S H, Camilli A. Novel approaches to monitor bacterial gene expression in infected tissue and host. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:97–101. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine M M, Galen J, Barry E, Noriega F, Tacket C, Sztein M, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Losonsky G, Kotloff K. Attenuated Salmonella typhi and Shigella as live oral vaccines and as live vectors. Behring Inst Mitt. 1997;98:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas R L, Lee C A. Unravelling the mysteries of virulence gene regulation in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1024–1033. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall D G, Haque A, Fowler R, Del Guidice G, Dorman C J, Dougan G, Bowe F. Use of the stationary phase inducible promoters, spv and dps, to drive heterologous antigen expression in Salmonella vaccine strains. Vaccine. 2000;18:1298–1306. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McSorley S J, Cookson B T, Jenkins M K. Characterization of CD4+ T cell responses during natural infection with Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol. 2000;164:986–993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McSorley S J, Xu D, Liew F Y. Vaccine efficacy of Salmonella strains expressing glycoprotein 63 with different promoters. Infect Immun. 1997;65:171–178. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.171-178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medina E, Paglia P, Rohde M, Colombo M P, Guzman C A. Modulation of host immune responses stimulated by Salmonella vaccine carrier strains by using different promoters to drive the expression of the recombinant antigen. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:768–777. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200003)30:3<768::AID-IMMU768>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy K M, Heimberger A B, Loh D Y. Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+CD8+TCRlo thymocytes in vivo. Science. 1990;250:1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.2125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orr N, Galen J E, Levine M M. Novel use of anaerobically induced promoter, dmsA, for controlled expression of fragment C of tetanus toxin in live attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strain CVD 908-htrA. Vaccine. 2001;19:1694–1700. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pape K A, Kearney E R, Khoruts A, Mondino A, Merica R, Chen Z M, Ingulli E, White J, Johnson J G, Jenkins M K. Use of adoptive transfer of T-cell-antigen-receptor-transgenic T cell for the study of T-cell activation in vivo. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts M, Li J, Bacon A, Chatfield S. Oral vaccination against tetanus: comparison of the immunogenicities of Salmonella strains expressing fragment C from the nirB and htrA promoters. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3080–3087. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3080-3087.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaible U E, Collins H L, Kaufmann S H. Confrontation between intracellular bacteria and the immune system. Adv Immunol. 1999;71:267–377. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sirard J C, Niedergang F, Kraehenbuhl J P. Live attenuated Salmonella: a paradigm of mucosal vaccines. Immunol Rev. 1999;171:5–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soncini F C, Vescovi E G, Groisman E A. Transcriptional autoregulation of the Salmonella typhimurium phoPQ operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4364–4371. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4364-4371.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su G F, Brahmbhatt H N, Wehland J, Rohde M, Timmis K N. Construction of stable LamB-Shiga toxin B subunit hybrids: analysis of expression in Salmonella typhimurium aroA strains and stimulation of B subunit-specific mucosal and serum antibody responses. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3345–3359. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3345-3359.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tacket C O, Galen J, Sztein M B, Losonsky G, Wyant T L, Nataro J, Wasserman S S, Edelman R, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Levine M M. Safety and immune responses to attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi oral live vector vaccines expressing tetanus toxin fragment C. Clin Immunol. 2000;97:146–153. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tacket C O, Sztein M B, Losonsky G A, Wasserman S S, Nataro J P, Edelman R, Pickard D, Dougan G, Chatfield S N, Levine M M. Safety of live oral Salmonella typhi vaccine strains with deletions in htrA and aroC aroD and immune response in humans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:452–456. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.452-456.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tacket C O, Sztein M B, Wasserman S S, Losonsky G, Kotloff K L, Wyant T L, Nataro J P, Edelman R, Perry J, Bedford P, Brown D, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Levine M M. Phase 2 clinical trial of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi oral live vector vaccine CVD 908-htrA in U.S. volunteers. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1196–1201. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1196-1201.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valdivia R H, Falkow S. Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science. 1997;277:2007–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J Y, Noriega F R, Galen J E, Barry E, Levine M M. Constitutive expression of the Vi polysaccharide capsular antigen in attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi oral vaccine strain CVD 909. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4647–4652. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4647-4652.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wick M J, Harding C V, Normark S J, Pfeifer J D. Parameters that influence the efficiency of processing antigenic epitopes expressed in Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4542–4548. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4542-4548.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wick M J, Harding C V, Twesten N J, Normark S J, Pfeifer J D. The phoP locus influences processing and presentation of Salmonella typhimurium antigens by activated macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu D, McSorley S J, Chatfield S N, Dougan G, Liew F Y. Protection against Leishmania major infection in genetically susceptible BALB/c mice by gp63 delivered orally in attenuated Salmonella typhimurium (AroA− AroD−) Immunology. 1995;85:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]