Abstract

Aim

was to assess the role of C-KIT, TET1 and TET2 expression in the diagnosis and prognosis of acute myeloblastic leukemia (AML).

Methods

The expression levels of C-KIT, TET1 and TET2 were assessed in the bone marrow (BM) aspirate of 152 AML patients compared to 20 healthy control using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Data were correlated with the clinico-pathological features of the patients, response to treatment, disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS) rates.

Results

C-KIT, TET1 and TET2 were significantly upregulated in AML patients [0.25 (0–11.6), 0.0113 (0–3.301), and 0.07 (0–4); respectively], compared to the control group [0.013 (0.005–0.250), P < 0.001, 0.001 (0–0.006), P < 0.001, and 0.02 (0.008–0.055), P = 0.019; respectively]. The sensitivity, specificity, and area under curve of of C-KIT were (48.7%, 100%, 0.855; respectively, P = 0.001), and that of TET1 were (63.4%, 100%, 0.897; respectively, P = 0.001), while that of TET2 were (56.8%, 100%, 0.766; respectively, P = 0.019). When combining the three markers, the sensitivity was 77.5%, however it reached the highest sensitivity (78.6%) and specificity (100%) when combining both c-KIT + TET1 together for the diagnosis of AML. C-KIT overexpression associated with shorter DFS (P = 0.05) and increased incidence of relapse (P = 0.019). Lymph nodes involvement [HR = 2.200, P = 0.005] is an independent risk factor for shorter OS rate of AML patients. Increased BM blast % [HR = 7.768, P = 0.002], and FLT3-ITD mutation [HR = 2.989, P = 0.032] are independent risk factors for shorter DSF rate of the patients.

Conclusion

C-KIT, TET1, and TET2 could be used as possible useful biomarkers for the diagnosis of AML.

Keywords: AML, C-KIT, TET1, TET2

Introduction

Leukemias are widespread hematological malignancies that are characterized by an uncontrolled proliferation of hematopoietic precursor blast cells, that interfere with the normal maturation and functions of the leukocytes [1]. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common leukemia that occurs in adult and pediatric patients, which is characterized by an increased incidence of relapse and poor outcomes for the patients [2]. It is a heterogeneous disease with a multistep process [3]. Hence, the recent risk stratification of the AML, e.g. The World Health Organization (WHO) [4] and European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classifications [5] depends upon the underlying genetic mutations together with the associated cytogenetic abnormalities to guide the therapeutic plan, and therefore, it will help in predicting the prognosis, outcomes, and response to treatment [5, 6]. The included genetic mutations which are widely used in the clinical practice for the risk stratification of the patients are tumor protein 53 (TP53), internal tandem duplication of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3-ITD), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (CEBPA), and nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1) [5].

The C-KIT oncogene encodes a class III transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase ( CD117) [7]. It is expressed in less than 5% of marrow myeloid progenitor cells [8], and it has an important role in the processes of cell proliferation, survival, adhesion, and chemotaxis [9]. Also, C-KIT expression is found in the blasts of 70% of the AML patients [10]. It had been reported that the overexpression of both wild and mutant types C-KIT can promote leukemogenesis [7, 11]. While its down-regulation can inhibit the activity of the hematological malignant cells [12].

Recently, there are many epigenetic mutations have been founded to have a role in the pathogenesis and development of AML. These epigenetic regulators included the family of ten-eleven translocation (TET) proteins, which facilitate DNA demethylation [13]. The tet oncogene family is composed of three isoenzymes, TET1, TET2, and TET3, which convert 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), formylcytosine (5fC), and carboxylcytosine (5caC) in a stepwise manner [14], which leads to demethylation, gene activation and consequently cellular proliferation [15]. There were some previous studies illusterated the significant relation between TET1 and TET2 gene expression with AML prognosis [16, 17].

TET1 has been found as a fusion partner of the MLL gene associated with t (10;11)(q22;q23) in AML [18, 19]. It plays an oncogenic role in AML as it was found that it promots expression of oncogenic targets (e.g., HOXA9, MEIS1, PBX3, etc.) and represses the expression of tumor suppressor targets (e.g., miR-22) [20, 21]. TET1 was significantly upregulated in MLL-rearranged AML [20–22]. Moreover Zhao et al. confirmed the essential oncogenic role of TET1 in the development of myeloid malignancies [15], Wang et al., found high TET1 expressers harbored poor overall survival in CN-AML patients [17]. For that, targeting TET1 signaling is a promising therapeutic strategy to treat TET1high AML patients [23]. Jiang et al., identified two compounds (i.e., NSC-311,068 and NSC-370,284) that selectively suppress TET1 transcription and 5hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) modification, that effectively inhibit cell viability in AML with high expression of TET1, including AML with MLL rearrangements and t(8;21). Also, they demonstrated that NSC-311,068 and especially NSC-370,284 significantly repressed TET1-high AML progression in vivo [23].

TET2 has a role in haematopoiesis as it reversed aberrant hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell self-renewal in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, it suppressed human leukemic colony formation and leukemia progression of primary human leukemia patient derived xenografts [24]. Rasmussen et al., indicated that loss of TET2 in hematopoietic cells leads to DNA hypermethylation of active enhancers and induction of leukemogenesis [25]. Also TET2 mutations frequently occur in AML [26, 27]. Moreover, TET2 mutations were important prognostic factors in AML and predicted response to hypomethylating agents in Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) patients [28].

The expression pattern and clinical significance of TET3 have been determined in several human cancers, which indicated that it plays a different role between cancer occurrence and development [29]. Some studies found that TET3 was highly expressed in renal cell carcinoma and endometrial cancers. Also, it had been proposed that a high mRNA level of TET3 was an independent predictor of poor outcome in patients with renal cell carcinoma [30, 31]. Zhang et al., observed that TET3 expression was increased in AML patients and acted as an independent prognostic factor, that could be overcame by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [29]. Whereas, several other investigations reported that TET3 was low-expressed in diverse human cancers as in cervical cancer [32], chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells [33] and in colorectal cancer [34].

Therefore, the aim of the current study is to investigate the diagnostic and prognostic values of C-KIT, TET1, and TET2 expression in AML patients. This may help to clearly understand their role in AML carcinogenesis, which allows for better risk stratification of the patients to guide individualized treatment protocol. This will be achieved by assessing the association between C-KIT, TET1, and TET2 expression with the patients’ clinicopathological features, response to treatment, and survival rates of the patients.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included 152 newly diagnosed AML patients, who were presented to the medical oncology clinics, National Cancer Institute (NCI), Cairo University, during the period from August 2016 to December 2018. Patients were compared to 20 healthy control subjects who were presented to the bone marrow transplantation unit.

Diagnosis of AML patients was performed through detailed history taking, full clinical examination, and laboratory investigations including complete blood count (CBC), BM aspiration, Immunophenotyping (IPT) of the blast cells, as well as conventional karyotyping.

The patients were classified according to the genetic risk (combined cytogenetic and molecular analysis according to Dohner et al., 2010 into three risk groups; favorable prognosis, intermediate risk group and poor prognosis [35]. Also, patients were classified according to ELN recommendations (which primarily relayed on concurrent gene mutations rather than genetic abnormalities) into Favorable risk group, intermediate risk group and adverse risk group [5].

Treatment and follow up of the patients

The induction chemotherapy for the AML patients was formed of a combination of cytosine arabinoside (100 mg/m2) for 7 days and Adriamycin (45 mg/m2) for 3 days. Patients who achieved complete remission (CR) and had favorable cytogenetics [inv16 and t(8; 21)] received consolidation chemotherapy with a high dose of Ara-C (3gm/m2 IV infusion over 3 h/12 hours for 3 days) for a total of 3–4 cycles. Patients with high-risk cytogenetics (monosomy 7 or 5, deletion of 5q, abnormalities of 3q, and those with a complex karyotype) or intermediate-risk cytogenetics (those with normal cytogenetics and other changes not associated with high risk or favorable groups) transferred for allogeneic BM transplantation (if they had matched sibling donor) after achieving CR. Patients who did not have a matched donor received consolidation chemotherapy as in the favorable group. Patients who relapsed after conventional chemotherapy or failed to achieve CR despite optimal induction treatment received the second induction and then transferred for allogeneic BM transplantation (if they had a matched sibling donor). Patients who relapsed after bone marrow transplantation received palliative chemotherapy (High dose ARA-C, Mitoxantrone).

Follow-up of the patients was done by the clinical and BM examination on day14 and day 28 of induction treatment. The outcome of the induction treatment was assessed at D28, where patients were categorized according to their response into patients who achieved complete remission (CR), and patients who were refractory to therapy. The CR was defined in accordance with standard criteria by Dohner et al. [35], which required an absolute neutrophil count of 1.5 × 109/L, platelet count of 100 × 109/L or more, no blasts in the peripheral blood (PB), BM cellularity more than 20%, no Auer rods, less than 5% BM blasts and no extramedullary leukemia. Disease free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date of CR to the date of relapse or death from any cause. The overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis until the date of death or last follow-up.

Sample collection

BM samples were obtained from all patients and control subjects according to the standard protocols for detection of c-KIT, TET1, and TET2 gene expression levels using quantitative RT-PCR.

Purification of total cellular RNA and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from the BM aspirate of all subjects using QIAamp RNA blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, LOT no. 154,013,334) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Quantitation and purity assessment of the isolated RNA were done using the Nano Drop® (ND)-1000 spectrophotometer (Nano Drop Technologies, Inc. Wilmington, USA). Reverse transcription of the RNA to cDNA was done by using the Applied Biosystems™ High-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, LOT no. 00716544).

Real-time quantification PCR ofc-Kit, TET1andTET2

The RT-PCR was carried out using fluorescent TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (c-Kit: Hs00174029, TET1: Hs04189344_g1; TET2: Hs00325999_m1, and β-Actin as a reference gene, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The RT- PCR amplification was performed using the computerized thermocyclers (ABI step one Applied Biosystems). The expression of the target genes was determined by relative fold change in gene expression, that was calculated using the delta-delta Ct method. It was normalized to the endogenous reference gene (β-Actin) and relative to the healthy controls [36].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS© Statistics version 22 (IBM© Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) according to the performed normality tests. Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. The Area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) was calculated to investigate the best cut-off value, sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of AML. The relation between qualitative variables was performed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Comparison between groups was done using the Mann-Whitney test. Survival analysis was done using Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the comparison between survival curves was done using the log-rank test. All tests were two-tailed. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The median age of the assessed AML patients was 33 (range 1–64), 35(23%) of them were lower than 18 years old, and 117 (77%) were adults. Males represented 53.3% (81/152), and females represented 46.7% (71/152). Bone marrow (BM) was hypercellular in 120 (79.5%) patients, normocellular in 27 (17.9%) patients, and hypocellular in only 4 (2.6%) patients. The most common FAB subtype was M2 in 51 (33.6%) patients, followed by M4 in 45 (29.6%) patients, and M1 in 28 (18.4%) patients. The IPT of the samples revealed that 63.3% (93/147) were myelocytic, 30.6% (45/147) were myelomonocytic, 4.1% (6/147) were monocytic, and 2.0% (3/147) were megakaryoblast. Twenty-five (16.7%) patients had mutant FLT3-ITD, 14 (23.3%) had mutant FLT3-TKD, and 24 (20.7%) had mutant NPM. Cytogenetics was favorable in 78 (58.2%) patients and adverse in 56 (41.8%) patients. There were 26 (17.1%) patients with high-risk diseases, 48 (31.6%) with intermediate-risk, and 78 (51.3%) patients with low-risk diseases. At the end of the study, relapse was reported in 18 (15.9%) patients, 54 (35.5%) patients died before day-28 of treatment (early death), and 42 (27.6%) died after day-28 (late death). Other clinical features of the patients were illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Association between c-KIT expression and the clinical features of the AML patients

| Parameter | Frequency (%) | c-KIT | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low expression | Overexpression | ||||

| Age (years) | Median (IQR) | 33 (1–64) | 33 (1–64) | 32 (1–64) | 0.538 |

| TLC | Median (IQR) | 24.9 (1-616) | 25 (1-395) | 24.9 (1-616) | 0.896 |

| Hb | Median (IQR) | 7.8 (4–14) | 7.4 (4–13) | 7.95 (4–14) | 0.694 |

| PLT | Median (IQR) | 33 (4-826) | 31 (6-191) | 34.5 (5-283) | 0.412 |

| PB. Blasts | Median (IQR) | 43 (0–98) | 40 (0–95) | 49 (0–98) | 0.036 |

| BM blasts | Median (IQR) | 70 (20–97) | 66.5 (20–97) | 70 (20–97) | 0.201 |

| gender | male | 81 (53.3%) | 45 (57.7%) | 36 (48.6%) | 0.329 |

| female | 71 (46.7%) | 33 (42.3%) | 38 (51.4%) | ||

| BM Cellularity Initial | hypercellularity | 120 (79.5%) | 57 (73.1%) | 63 (86.3%) | 0.126 |

| normocelluarity | 27 (17.9%) | 18 (23.1%) | 9 (12.3%) | ||

| hypocellularity | 4 (2.6%) | 3 (3.8%) | 1 (1.4%) | ||

| FAB | M0 | 3 (2.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0.633 |

| M1 | 28 (18.4%) | 12 (15.4%) | 16 (21.6%) | ||

| M2 | 51 (33.6%) | 25 (32.1%) | 26 (35.1%) | ||

| M3 | 14 (9.2%) | 9 (11.5%) | 5 (6.8%) | ||

| M4 | 45 (29.6%) | 23 (29.5%) | 22 (29.7%) | ||

| M5 | 8 (5.3%) | 6 (7.7%) | 2 (2.7%) | ||

| M7 | 3 (2.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 2 (2.7%) | ||

| IPT | monocytic | 6 (4.1%) | 5 (6.6%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0.385 |

| myelocytic | 93 (63.3%) | 46 (60.5%) | 47 (66.2%) | ||

| myelomonocytic | 45 (30.6%) | 24 (31.6%) | 21 (29.6%) | ||

| megakaryoblastic | 3 (2.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 2 (2.8%) | ||

| FLT3-ITD | wild | 125 (83.3%) | 62 (81.6%) | 63 (85.1%) | 0.663 |

| mutant | 25 (16.7%) | 14 (18.4%) | 11 (14.9%) | ||

| FLT3-TKD | wild | 46 (76.7%) | 24 (96.0%) | 22 (62.9%) | 0.004 |

| mutant | 14 (23.3%) | 1 (4.0%) | 13 (37.1%) | ||

| NPM | wild | 92 (79.3%) | 47 (82.5%) | 45 (76.3%) | 0.494 |

| mutant | 24 (20.7%) | 10 (17.5%) | 14 (23.7%) | ||

| Chromosomal translocations | negative | 105 (69.5%) | 57 (74.0%) | 48 (64.9%) | 0.385 |

| t(8;21) | 25 (16.6%) | 10 (13.0%) | 15 (20.3%) | ||

| inv. 16 | 9 (6.0%) | 3 (3.9%) | 6 (8.1%) | ||

| PML/RARa | 12 (7.9%) | 7 (9.1%) | 5 (6.8%) | ||

| Cytogenetics | favorable | 78 (58.2%) | 34 (49.3%) | 44 (67.7%) | 0.036 |

| adverse | 56 (41.8%) | 35 (50.7%) | 21 (32.3%) | ||

| genetic risk | HR | 26 (17.1%) | 18 (23.1%) | 8 (10.8%) | 0.042 |

| IR | 48 (31.6%) | 27 (34.6%) | 21 (28.4%) | ||

| LR | 78 (51.3%) | 33 (42.3%) | 45 (60.8%) | ||

| ELN classification | AR | 13 (8.6%) | 8 (10.3%) | 5 (6.8%) | 0.382 |

| IR | 95 (62.5%) | 51 (65.4%) | 44 (59.5%) | ||

| FR | 44 (28.9%) | 19 (24.4%) | 25 (33.8%) | ||

| Organomegaly | no | 60 (53.6%) | 28 (47.5%) | 32 (60.4%) | 0.105 |

| hepatomegaly | 11 (9.8%) | 8 (13.6%) | 3 (5.7%) | ||

| splenomegaly | 13 (11.6%) | 10 (16.9%) | 3 (5.7%) | ||

| HSM | 28 (25.0%) | 13 (22.0%) | 15 (28.3%) | ||

| LNs involvement | no | 55 (47.4%) | 27 (50.0%) | 28 (45.2%) | 0.710 |

| yes | 61 (52.6%) | 27 (50.0%) | 34 (54.8%) | ||

| Relapse | no | 95 (84.1%) | 57 (91.9%) | 38 (74.5%) | 0.019 |

| yes | 18 (15.9%) | 5 (8.1%) | 13 (25.5%) | ||

| Early death (before D28) | no | 98 (64.5%) | 49 (62.8%) | 49 (66.2%) | 0.735 |

| yes | 54 (35.5%) | 29 (37.2%) | 25 (33.8%) | ||

| late death (after D28) | no | 110 (72.4%) | 59 (75.6%) | 51 (68.9%) | 0.371 |

| yes | 42 (27.6%) | 19 (24.4%) | 23 (31.1%) | ||

| Overall Death | no | 56 (36.8%) | 31 (39.7%) | 25 (33.8%) | 0.503 |

| yes | 96 (63.2%) | 47 (60.3%) | 49 (66.2%) | ||

BM: bone marrow, HB: haemoglobin: IPT: immunophenotyping, PB: peripheral blood, BM: bone marrow, PLT: platelets, TLC: total leukocyte count

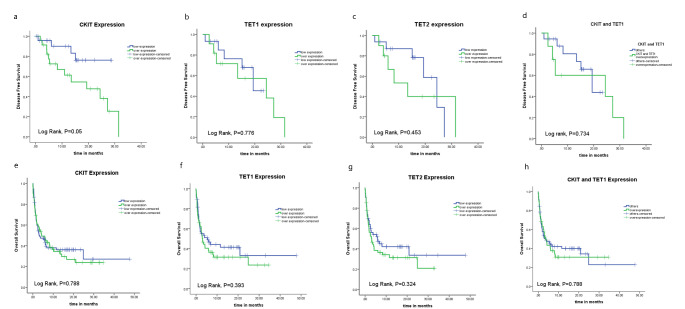

Expression levels of c-Kit, TET1 and TET2 in AML patients

There was a significant upregulation of c-Kit expression level in AML patients compared to the control group [0.25 (0-11.6) and 0.013 (0.005–0.250); respectively, P < 0.001]. Similarly, TET1 and TET2 genes were upregulated in AML patients [0.0113 (0-3.301) and 0.07 (0–4); respectively] in comparison to the control group [0.001 (0-0.006) and 0.02 (0.008–0.055); respectively], where the significance levels were (P < 0.001 and 0.019; respectively, Fig. 1 A, B, C).

Fig. 1.

Expression levels of: (A) C-KIT, (B) TET1, and (C) TET2 in BM sample of adult AML patients compared to the normal controls. ROC analysis of (D) C-KIT, (E) TET1, and (F) TET2 for the diagnosis of AML patients compared to the normal controls

The diagnostic value of c-Kit, TET1 and TET2 in AML patients

The ROC was performed to evaluate the role of c-Kit, TET1 and TET2 expression in the diagnosis of AML patients in comparison to the control subjects. The sensitivity of each gene was assessed at a specificity of 100% to ensure better diagnosis of the patients without the risk of false negative results.

At a specificity of 100%, the sensitivity and area under curve (AUC) of c-Kit were (48.7% and 0.855; respectively, with a cut-off 0.25, P < 0.001), the sensitivity and AUC of TET1 were 63.4% and 0.897; respectively, with a cut-off 0.006, (P < 0.001), and that of TET2 were (56.8% and 0.766; respectively, with a cut-off 0.06,P = 0.019). When combining the three markers together, the sensitivity increased to be 66.7% for TET1 + TET2, 77.5% for c-KIT + TET1 + TET2, while it was 78.6% for c-KIT + TET1 (P < 0.001 for all, Fig. 1D, E, F; Table 2).

Table 2.

Roc curve analysis of c-KIT, TET1 and TET2 for diagnosis of AML patients

| AUC | Cut off | sensitivity | specificity | P value | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| c-KIT | 0.855 | 0.25 | 48.7% | 100% | P < 0.001 | 0.767 | 0.943 |

| TET 1 | 0.897 | 0.006 | 63.4% | 100% | P < 0.001 | 0.803 | 0.990 |

| TET 2 | 0.766 | 0.06 | 56.8% | 100% | 0.019 | 0.651 | 0.880 |

| TET1 + TET2 | 0.894 | - | 66.7% | 100% | P < 0.001 | 0.804 | 0.984 |

| c-KIT + TET1 | 0.915 | - | 78.6% | 100% | P < 0.001 | 0.849 | 0.980 |

| c-KIT TET1 + TET2 | 0.910 | - | 77.5% | 100% | P < 0.001 | 0.845 | 0.975 |

AUC: area under curve, CI: confidence interval

Patients were categorized into lowexpressors and overexpressors according to the cut-off obtained by the ROC analysis for c-Kit, TET1, and TET2 expression (0.25, 0.006, and 0.06; respectively).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of CKIT, TET1 and TET2 for the diagnosis of AML

The univariate logistic regression analysis showed that CKIT, TET1, TET2 or CKIT + TET1 associated significantly with AML. While the multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that only CKIT (OR:3.942, P = 0.012) and TET1 (OR:4.199, P = 0.021) were considered as independent possible predictors for the diagnosis of AML patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of CKIT, TET1 and TET2 for the diagnosis of AML

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | SE | P value | OR | SE | P value | |

| CKIT | 7.091 | 0.322 | P < 0.001 | 3.942 | 0.547 | 0.012 |

| TET1 | 8.000 | 0.401 | P < 0.001 | 4.199 | 0.620 | 0.021 |

| TET2 | 7.571 | 0.402 | P < 0.001 | 0.713 | 0.714 | 0.635 |

| CKIT + TET1 | 10.286 | 0.396 | P < 0.001 | 17.9 | 0.427 | 0.997 |

OR: odds ratio, SE: standard error

Association between c-KIT expression and the clinical features of the patients

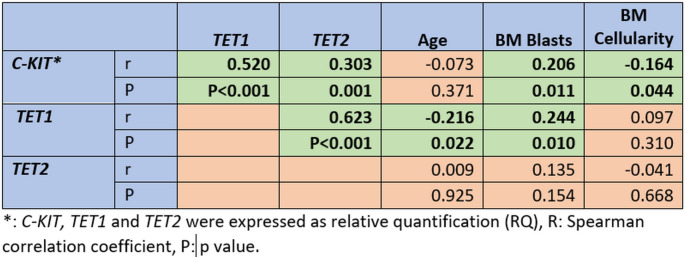

There was a significant association between c-Kit overexpression and increased PB blast cell%, FLT3-TKD mutation, and disease relapse (P = 0.036, 0.004 and 0.019; respectively). However, C-KIT overexpression associated with cytogenetic of favorable prognosis and low-risk stratification (P = 0.036 and P = 0.042; respectively, Table 4). There was a significant correlation between the relative quantification (RQ) of CKIT expression and TET1 (r = 0.520 P < 0.001), TET2 (r = 0.303, P = 0.001), BM blasts% (r = 0.206, P = 0.011). while there was a weak inverse correlation with BM celluarity (r=-0.164, P = 0.044, Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Association between TET1 and TET2 expression with the clinical features of the patients

| TET1 expression | P value | TET2 expression | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low expression |

Over

expression |

Low expression |

Over

expresion |

||||

| Age (years) | median(range) | 36 (1–64) | 29 (1–62) | 0.063 | 29 (1–64) | 34 (1–64) | 0.781 |

| TLC | median(range) | 17.9 (1-395) | 30 (1-616) | 0.044 | 16 (1-177) | 31 (1-616) | 0.036 |

| Hb | median(range) | 8 (4–14) | 7.8 (4–12) | 0.332 | 7.9 (4–14) | 7.7 (4–13) | 0.813 |

| PLT | median(range) | 34 (5-244) | 33 (5-283) | 0.751 | 33 (6-244) | 24 (5-283) | 0.631 |

| PB. Blasts | median(range) | 39 (0–90) | 50 (0–98) | 0.030 | 40 (0–90) | 47 (0–98) | 0.182 |

| BM blasts | median(range) | 65 (20–97) | 71 (25–97) | 0.026 | 65 (20–96) | 71 (25–97) | 0.306 |

| Sex | male | 32 (56.1%) | 27 (49.1%) | 0.570 | 29 (54.7%) | 30 (51.7%) | 0.849 |

| female | 25 (43.9%) | 28 (50.9%) | 24 (45.3%) | 28 (48.3%) | |||

| BM Cellularity Initial | hypercellularity | 46 (82.1%) | 44 (80.0%) | 0.352 | 41 (77.4%) | 49 (86.0%) | 0.483 |

| normocelluarity | 10 (17.9%) | 9 (16.4%) | 11 (20.8%) | 7 (12.3%) | |||

| hypocellularity | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.8%) | |||

| FAB | M0 | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.598 | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0.981 |

| M1 | 9 (15.8%) | 12 (21.8%) | 11 (20.8%) | 9 (15.5%) | |||

| M2 | 18 (31.6%) | 17 (30.9%) | 16 (30.2%) | 19 (32.8%) | |||

| M3 | 8 (14.0%) | 5 (9.1%) | 6 (11.3%) | 7 (12.1%) | |||

| M4 | 18 (31.6%) | 15 (27.3%) | 15 (28.3%) | 18 (31.0%) | |||

| M5 | 3 (5.3%) | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (3.8%) | 3 (5.2%) | |||

| M7 | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.5%) | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (1.7%) | |||

| IPT | mono | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0.309 | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.822 |

| myelo | 36 (64.3%) | 33 (63.5%) | 33 (63.5%) | 35 (63.6%) | |||

| myelomono | 18 (32.1%) | 15 (28.8%) | 15 (28.8%) | 18 (32.7%) | |||

| megakaryoblastic | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.8%) | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | |||

| FLT3-ITD | wild | 46 (83.6%) | 44 (80.0%) | 0.805 | 41 (80.4%) | 48 (82.8%) | 0.807 |

| mutant | 9 (16.4%) | 11 (20.0%) | 10 (19.6%) | 10 (17.2%) | |||

| FLT3-TKD | wild | 19 (82.6%) | 16 (66.7%) | 0.318 | 16 (80.0%) | 19 (70.4%) | 0.517 |

| mutant | 4 (17.4%) | 8 (33.3%) | 4 (20.0%) | 8 (29.6%) | |||

| NPM | wild | 31 (70.5%) | 38 (82.6%) | 0.216 | 30 (71.4%) | 38 (80.9%) | 0.327 |

| mutant | 13 (29.5%) | 8 (17.4%) | 12 (28.6%) | 9 (19.1%) | |||

| molecular translocations | negative | 40 (70.2%) | 40 (72.7%) | 0.838 | 40 (75.5%) | 39 (67.2%) | 0.529 |

| t(8;21) | 7 (12.3%) | 8 (14.5%) | 5 (9.4%) | 10 (17.2%) | |||

| inv. 16 | 3 (5.3%) | 3 (5.5%) | 2 (3.8%) | 4 (6.9%) | |||

| PML/RARa | 7 (12.3%) | 4 (7.3%) | 6 (11.3%) | 5 (8.6%) | |||

| Cytogenetics | Favourable | 28 (60.9%) | 25 (49.0%) | 0.308 | 26 (59.1%) | 26 (50.0%) | 0.416 |

| adverse | 18 (39.1%) | 26 (51.0%) | 18 (40.9%) | 26 (50.0%) | |||

| genetic risk | HR | 7 (12.3%) | 11 (20.0%) | 0.366 | 9 (17.0%) | 9 (15.5%) | 0.968 |

| IR | 15 (26.3%) | 17 (30.9%) | 15 (28.3%) | 16 (27.6%) | |||

| LR | 35 (61.4%) | 27 (49.1%) | 29 (54.7%) | 33 (56.9%) | |||

| ELN classification | AR | 5 (8.9%) | 4 (7.1%) | 0.832 | 4 (7.5%) | 5 (8.6%) | 0.564 |

| IR | 35 (62.5%) | 38 (67.9%) | 37 (69.8%) | 35 (60.3%) | |||

| FR | 16 (28.6%) | 14 (25.0%) | 12 (22.6%) | 18 (31.0%) | |||

| Organomegaly | no | 25 (59.5%) | 25 (58.1%) | 0.910 | 22 (55.0%) | 28 (63.6%) | 0.861 |

| hepatomegaly | 4 (9.5%) | 4 (9.3%) | 4 (10.0%) | 4 (9.1%) | |||

| splenomegaly | 3 (7.1%) | 5 (11.6%) | 4 (10.0%) | 4 (9.1%) | |||

| HSM | 10 (23.8%) | 9 (20.9%) | 10 (25.0%) | 8 (18.2%) | |||

| LNs | no | 21 (51.2%) | 21 (44.7%) | 0.669 | 18 (46.2%) | 24 (50.0%) | 0.830 |

| yes | 20 (48.8%) | 26 (55.3%) | 21 (53.8%) | 24 (50.0%) | |||

| Relapse | no | 29 (80.6%) | 31 (83.8%) | 0.768 | 30 (81.1%) | 29 (82.9%) | 0.845 |

| yes | 7 (19.4%) | 6 (16.2%) | 7 (18.9%) | 6 (17.1%) | |||

| Early death before D28 | no | 41 (71.9%) | 32 (58.2%) | 0.165 | 35 (66.0%) | 37 (63.8%) | 0.844 |

| yes | 16 (28.1%) | 23 (41.8%) | 18 (34.0%) | 21 (36.2%) | |||

| late death after d28 | no | 41 (71.9%) | 44 (80.0%) | 0.380 | 41 (77.4%) | 44 (75.9%) | 0.852 |

| yes | 16 (28.1%) | 11 (20.0%) | 12 (22.6%) | 14 (24.1%) | |||

| Death | no | 25 (43.9%) | 20 (36.4%) | 0.446 | 23 (43.4%) | 22 (37.9%) | 0.569 |

| yes | 32 (56.1%) | 35 (63.6%) | 30 (56.6%) | 36 (62.1%) | |||

AR: advanced risk, BM: bone marrow, FR: favourable risk, LR: low risk, HB: haemoglobin: HR: high risk, IPT: immunophenotyping, IR: intermediate risk, PB: peripheral blood, BM: bone marrow, PLT: platelets, TLC: total leukocyte count

Fig. 2.

correlation between TET1, TET2, CKIT, blast percentage, patient age and BM cellularity in AML patients

Association between TET1 and TET2 expression levels and the clinical features of the patients

TET1 overexpression associated significantly with increased TLC count, PB blast%, and BM blast% (P = 0.044, 0.030, and 0.026; respectively, Table 4). While TET2 overexpression associated significantly with increased TLC count only in the recruited AML patients (P = 0.036, Table 5). However, there was no significant association between TET1 and TET2 expression levels and the other clinicopathological features assessed.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis for OS and DFS rates of the AML patients

| Overall survival | Disease Free Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | SE | Sig. | HR | SE | Sig. | |

| Univariate analysis | ||||||

| Age | 1.142 | 0.209 | 0.526 | 2.662 | 0.532 | 0.065 |

| Sex | 1.225 | 0.206 | 0.327 | 0.589 | 0.580 | 0.362 |

| HB | 0.924 | 0.209 | 0.705 | 0.440 | 0.541 | 0.129 |

| TLC | 1.307 | 0.208 | 0.199 | 1.150 | 0.526 | 0.791 |

| PLT | 1.075 | 0.209 | 0.729 | 1.284 | 0.503 | 0.619 |

| BM blast% | 1.360 | 0.206 | 0.136 | 8.927 | 0.668 | 0.001 |

| PB blast% | 1.431 | 0.210 | 0.087 | 1.801 | 0.509 | 0.248 |

| BM cellularity | 0.688 | 0.246 | 0.129 | 1.687 | 0.757 | 0.490 |

| Genetic risk | 1.424 | 0.259 | 0.172 | 2.789 | 0.588 | 0.081 |

| Cytogenetic | 1.475 | 0.223 | 0.081 | 0.900 | 0.653 | 0.872 |

| ELN stage | 1.131 | 0.370 | 0.739 | 1.795 | 0.770 | 0.448 |

| LNs involvement | 2.064 | 0.246 | 0.003 | 0.942 | 0.558 | 0.914 |

| IPT | 0.998 | 0.237 | 0.257 | 0.860 | 0.543 | 0.782 |

| Organomegaly | 1.294 | 0.250 | 0.302 | 0.358 | 0.599 | 0.086 |

| FAB1 | 1.078 | 0.218 | 0.731 | 1.401 | 0.509 | 0.508 |

| FLT3-ITD mutation | 0.801 | 0.280 | 0.427 | 3.770 | 0.507 | 0.009 |

| FLT3-TKD mutation | 0.703 | 0.410 | 0.390 | 2.843 | 0.920 | 0.256 |

| NPM mutation | 0.480 | 0.321 | 0.022 | 0.481 | 1.049 | 0.485 |

| c-KIT | 0.811 | 0.212 | 0.321 | 2.976 | 0.584 | 0.062 |

| TET1 | 1.324 | 0.247 | 0.257 | 1.212 | 0.675 | 0.776 |

| TET2 | 1.242 | 0.249 | 0.385 | 1.578 | 0.612 | 0.456 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| LNs involvement | 2.200 | 0.280 | 0.005 | |||

| NPM | 0.567 | 0.354 | 0.110 | |||

| BM Blast% | 7.768 | 0.671 | 0.002 | |||

| FLT3-ITD | 2.989 | 0.511 | 0.032 | |||

BM: bone marrow, HB: haemoglobin, HR: hazard ratio, IPT: immunophenotyping, PB: peripheral blood, BM: bone marrow, PLT: platelets, TLC: total leukocyte count

TET1 correlated significantly with TET2 expression (r = 0.623, P < 0.001), BM blasts% (r = 0.244, P = 0.010), and patients’ age (r=-0.216, P = 0.022, Fig. 2).

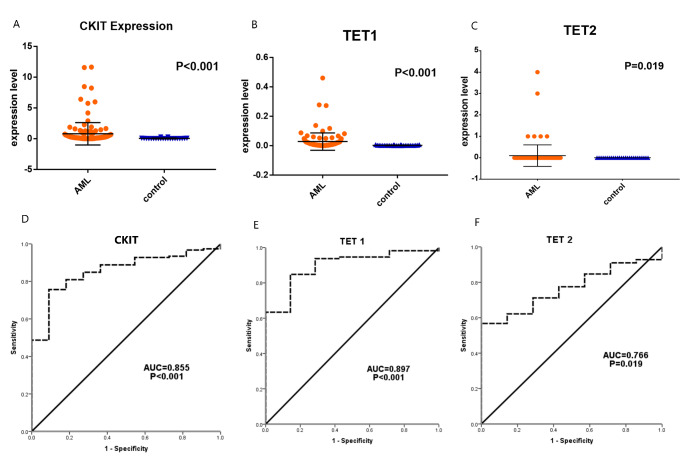

Impact of c-Kit, TET1 and TET2 expression levels on the DFS and OS rates of the AML patients

The AML patients who had c-KIT overexpression showed a significantly lower DFS rate compared to those with c-KIT low-expression, as the mean DFS in c-KIT overexpressors was 18.183 months compared to 24.212 months in those with c-KIT low-expression (P = 0.05). However, there was no significant association between c-KIT expression and OS rates of the patients. Similarly, there was no significant impact of TET1 nor TET2 expression levels and OS or DFS rates of the recruited AML patients (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Association of (a) C-KIT, (b) TET1, (c) TET2 and (d) C-KIT + TET1 expression with the disease free survival of the patients. Association of (e) C-KIT, (f) TET1, (g) TET2 and (h) C-KIT + TET1 expression with the overall survival rates of the AML patients

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the patients

The univariate analysis showed that patients with lymph nodes (LN) involvement [HR = 2.064, P = 0.003] and/or mutant NPM [HR = 0.480, P = 0.022] had significantly lower OS rates. While patients with increased BM blast% [HR = 0.668, P = 0.001], and/or those with FLT3-ITD mutation [HR = 0.507, P = 0.009] showed a significant lower DFS rates.

On the other hand, multivariate analysis showed that LN involvement [HR = 2.200, P = 0.005] is an independent risk factor for the shorter OS rate of AML patients. While increased BM blast% [HR = 7.768, P = 0.002], and FLT3-ITD mutation [HR = 2.989, P = 0.032] are independent risk factors for shorter DSF rate of the patients (Table 5).

The prognostic accuracy of CKIT, TET1 and TET2 for AML patients

The prognostic accuracy of CKIT, TET1 and TET2 was assessed in relation to the established prognostic factors including patient age, ELN risk stage, and BM blasts %. The data showed that the AUC for patient age, ELN risk stage, and BM blasts % for predicting relapse of the AML patients was 0.646 (P = 0.049), and when adding CKIT, the AUC increased to 0.740 (P = 0.001). While when using patient age, ELN risk stage, BM blasts %, CKIT, TET1 and TET2, the AUC increased to 0.743 (P = 0.005). Regarding the survival of the patients, patient age, ELN risk stage, and BM blasts % achieved (AUC: 0.623, P = 0.012), whlie when adding CKIT, TET1 and TET2, the AUC become 0.622 (P = 0.031, Table 6).

Table 6.

The prognostic accuracy of CKIT, TET1 and TET2 for AML patients

| Relapse | Survival | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Std. Error | P value | 95% CI | AUC | Std. Error | P value | 95% CI | |||

| patient age + ELN + BM blasts % | 0.646 | 0.064 | 0.049 | 0.522 | 0.771 | 0.623 | 0.046 | 0.012 | 0.533 | 0.713 |

| patient age + ELN + BM blasts %+ CKIT | 0.740 | 0.060 | 0.001 | 0.622 | 0.858 | 0.612 | 0.046 | 0.023 | 0.522 | 0.701 |

| patient age + ELN + BM blasts %+ TET1 | 0.654 | 0.066 | 0.066 | 0.524 | 0.784 | 0.619 | 0.054 | 0.034 | 0.514 | 0.724 |

| patient age + ELN + BM blasts %+ TET2 | 0.666 | 0.063 | 0.054 | 0.542 | 0.791 | 0.616 | 0.054 | 0.037 | 0.510 | 0.723 |

| patient age + ELN + BM blasts %+ CKIT + TET1 + TET2 | 0.743 | 0.066 | 0.005 | 0.613 | 0.872 | 0.622 | 0.053 | 0.031 | 0.517 | 0.727 |

AUC: area under curve, CI: confidence interval

Discussion

AML is the most common hematological malignancy worldwide. Though the advancement of the diagnostic and therapeutic modalities, still, there is an increased incidence of disease relapse and lower survival rates in AML patients. DNA methylation plays an important role in AML carcinogenesis, however, few studies had investigated the diagnostic and prognostic roles of TETs expression in AML [29]. The current study aimed at investigating the role of C-KIT, TET1, and TET2 expression levels and their clinical significance in AML patients.

The present data showed that C-KIT was significantly up-regulated in AML cases compared to the control group with a diagnostic power of 48.7% sensitivity and 100% specificity. These data are in agreement with other studies reported up-regulation of C-KIT in AML patients compared to the control group [37–40]. Abrams et al., found that C-KIT overexpression was recognized in many cancers including gastrointestinal stromal tumors, small cell lung cancer, melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, and AML, which raise the attention for using an anti-C-KIT antibody as a treatment protocol in these cancers [37]. Moreover, C-KIT up-regulation was a bad prognostic factor for AML patients, as its upregulation was significantly associated with a shorter DFS rate. This came in concordance with Advani et al. who found that increased intensity of C-KIT using the mean fluorescence index correlates with a decreased progression-free survival (PFS) and OS rates in AML patients [38]. Also, Gao et al. found that PFS was significantly shorter in patients with high C-KIT expression [39].

In the current study, C-KIT overexpression associated significantly with increased peripheral blood blasts and FLT3-TKD mutation. These data are in agreement with Hoehn et al. [40], who concluded that CD117(C-KIT) expression is a sensitive marker for FLT3 mutation in AML. However, Woźniak and Kopeć-Szlezak [41] found a negative correlation between the level of C-Kit expression and the peripheral blood blasts. This discrepancy may be due to the different methods used for the detection of C-Kit expression, as they used a relative fluorescence intensity using immunophenotypic analysis [40]. In addition, C-KIT overexpression showed a significant association with disease relapse in AML patients. These results are similar to that observed by Gao et al. [39], who found that patients with C-KIT overexpression showed poor disease outcomes. Moreover, our data demonstrated that lower expression of C-KIT was found in patients with low-risk prognostic factors, and its overexpression associated significantly with karyotypes of favorable prognosis [AML with t(8;21) and (inv-16)]. These data are in concordance with that reported by Gao et al. and Auewarakul et al., who found a significant association between C-KIT overexpression and the presence of AML with t(8;21) and/or inv-16 [39–42].

The current study showed also that TET1and TET2 were significantly upregulated in the BM samples of AML patients compared to the control group. In addition, TET1, TET2, and C-KIT could possibly add a diagnostic value for AML patients based upon the results obtained from the ROC curve analysis. It showed that TET2 achieved the highest sensitivity (63.4%) compared to TET2 (56.8%) and C-KIT (48.7%) expression at a specificity of 100%, while when combining the three markers together, the sensitivity was 77.5%. However, it reached the highest sensitivity (78.6%) and specificity (100%) when combining the expression of both c-KIT + TET1 together for the diagnosis of AML. Actually, the expression levels of TET1 and TET2 mRNA in AML patients are still a debatable issue. Zhang et al. (2020), found that TET1 was down-regulated, while TET2 was up-regulated in AML patients [29]. Similarly, Cheng et al. [43], observed a significant upregulation of TET2 in AML patients. However, Zhang et al. (2018) found that TET2 mRNA level was significantly down-regulated in AML patients compared with control subjects [16]. This discrepancy in the results may be due to the differeneces in the detection assay or the housekeeeping gene used. As well as the different cells used for the assessment either using unsorted whole BM cells or using sorted BM blasts, in addition to the different sample size of the patients.

Regarding the prognostic value of TET1 and TET2 in AML patients, our results could not confirm that TET1 and TET2 overexpression were a bad prognostic factor for AML, as we were not able to find a significant association between TET1 or TET2 expression and survival rates (DFS and OS) of the patients. This came in agreement with Zhang et al. [29], who found that there is no significant associations between TET1 or TET2 expression and the survival rates of the assessed patients. However, Wang et al. [17] proposed that high expression of TET1 was significantly associated with poor prognosis of the patients in the form of shorter OS and DFS rates in cytogenetically normal AML patients. Though, this was not applied to patients with high expression of TET2. This difference in the results could be attributed to the impact of using unsorted bone marrow cells other than using blast cells, in addition to that some patients included in the current study had AML with cytogenetic abnormalities.

The present results showed that TET1 overexpression associated significantly with high TLC together with a high number of PB blasts and BM blasts, while it had no significant association with age, FLT3/TKD mutation, molecular translocations nor any of the FAB subtypes. These data are consistent with Wang et al. [17], who couldn’t confirm any significant association between TET1 overexpression and patients’ ages or FLT3 mutation, however, they found that the cytogenetically normal AML patients with high TET1 expression showed a higher frequency of NPM1 mutations and FAB M0/1 morphology, while there was no significant association between TET1 expression and TLC, PB nor BM blasts. This controversy may be due to the impact of using unsorted bone marrow cells, or using different detection methods (e.g. different housekeeping gene). In addition to the difference in the number and type of the patients, as they recriuted a larger number of patients who were cytogenetically normal AML.

As regards TET2, its overexpression associated significantly with a high total leukocyte count. However, there was no significant association with age, sex, hemoglobin level, platelet count, percentage of PB blasts, BM blasts, cytogenetic abnormality, FLT3, or NPM mutations.

These data are comparable to that observed by Zhang et al. [16], who concluded similar results except that patients with low TET2 expression showed a high frequency of NPM1 mutations. Also, they found a significant association between TET2 expression and FAB subtypes of leukemia. This controversy could be attributed to the large number of patients who had NPM1 mutation included in their study, compared to the small number available for the present study [16].

Multivariate analysis showed that LN involvement is an independent risk factor for the shorter OS rate of AML patients. While increased BM blast% and FLT3-ITD mutation are independent risk factors for shorter DSF rate of the patients. However, when correlating the prognostic accuracy of the assessed genes to the established prognostic factors including patient age, ELN risk stage, and BM blasts %, it revelaed that adding CKIT, TET1, or TET2 could impove the prognosic power for prediciting relapse in AML patients. Moreover, when combining patient age, ELN risk stage, BM blasts %, CKIT, TET1 and TET2 together, the prognostic power became greater. On the other hand, adding CKIT, TET1 and TET2 had no significant impact on predicting patients’ survival. These data are in agreement with Liu et al. [44], who reported that TET2 mutations had an adverse impact on the prognosis of AML patients. Also, Wang et al. [17] proposed that TET1 was a reliable prognostic factor for patients with AML.

In conclusion, C-KIT, TET1, and TET2 were upregulated in newly diagnosed AML patients compared to the control subjects. All of them associated with specific phenotypes of AML indicating that these biological biomarkers may be helpful in providing new insights in understanding the pathogenesis of AML. Additionally, C-KIT, TET1, and TET2 could be used as potential useful markers for the diagnosis of AML especially when combined together as c-KIT + TET1 + TET2 achieved a sensitivity of 77.5%, and specificity of 100%, while c-KIT + TET1 achieved a sensitivity of 78.6%, and a specificity of 100%. Moreover, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that CKIT and TET1 could be considered as possible independent predictors for AML diagnosis. Also, C-KIT, TET1 and TET2 proved to be a negative prognostic biomarker for relapse in AML patients. However, these results should be validated on a larger number of samples with more categorization of patients according to their age, risk, and leukemia subtypes.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there is no possible conflict of interest.

Compliance ethical standards

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Ethical Committee in the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Cairo university, which is in concordance with 2011 Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant or their relatives before enrolment in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Whiteley AE, Price TT, Cantelli G, Sipkins DA (2021 Jul) Leukaemia: a model metastatic disease. Nat Rev Cancer 21(7):461–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A, Cancer Statistics, Cancer JC (2021) 2021 Jan;71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. Epub 2021 Jan 12. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jul;71(4):359 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Li MJ, Yang YL, Lee NC, Jou ST, Lu MY, Chang HH, Lin KH, Peng CT, Lin DT (2016 Sep) Tet oncogene family member 2 gene alterations in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J Formos Med Assoc 115(9):801–806 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA et al The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms.Blood. 2016 May19;127(20):2375–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Bloomfield CD. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:424–447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimwade D, Hills RK (2009) Independent prognostic factors for AML outcome.Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. :385–95 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Szatkowski D, Hellmann A. The overexpression of KIT proto-oncogene in acute leukemic cells is not necessarily caused by the gene mutation. Acta Haematol. 2015;133(1):116–123. doi: 10.1159/000360214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells SJ, Bray RA, Stempora LL, Farhi DC (1996 Aug) CD117/CD34 expression in leukemic blasts. Am J Clin Pathol 106(2):192–195 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Advani AS (2006 Jun) Targeting the c-kit receptor in the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 1(2):101–107 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Estey EH (2013 Sep) Epigenetics in clinical practice: the examples of azacitidine and decitabine in myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 27(9):1803–1812 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Reilly JT (2002 Mar) Class III receptor tyrosine kinases: role in leukaemogenesis. Br J Haematol 116(4):744–757 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Larrue C, Saland E, Vergez F, Serhan N, Delabesse E et al (2015 Oct) Antileukemic Activity of 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose through Inhibition of N-Linked Glycosylation in Acute Myeloid Leukemia with FLT3-ITD or c-KIT Mutations. Mol Cancer Ther 14(10):2364–2373 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lou H, Li H, Ho KJ, Cai LL, Huang AS, Shank TR, Verneris MR, Nickerson ML, Dean M, Anderson SK The Human TET2 Gene Contains Three Distinct Promoter Regions With Differing Tissue and Developmental Specificities.Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019 Jun7;7:99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Wu X, Zhang Y, TET-mediated active DNA demethylation: mechanism, function and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18(9):517–534. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Z, Chen L, Dawlaty MM, Pan F, Weeks O et al Combined Loss of Tet1 and Tet2 Promotes B Cell, but Not Myeloid Malignancies, in Mice.Cell Rep. 2015 Nov24;13(8):1692–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Zhang TJ, Zhou JD, Yang DQ, Wang YX, Wen XM, et al. TET2 expression is a potential prognostic and predictive biomarker in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:5838–5846. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Li F, Ma Z, Yu M, Guo Q, et al. High Expression of TET1 Predicts Poor Survival in Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia From Two Cohorts. EBioMedicine. 2018;28:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu H, D’Alessio AC, Ito S, Xia K, Wang Z et al Dual functions of Tet1 in transcriptional regulation in mouse embryonic stem cells.Nature. 2011 May19;473(7347):389–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ono R, Taki T, Taketani T, Taniwaki M, Kobayashi H, Hayashi Y LCX, leukemia-associated protein with a CXXC domain, is fused to MLL in acute myeloid leukemia with trilineage dysplasia having t(10;11)(q22;q23).Cancer Res. 2002 Jul15;62(14):4075–80 [PubMed]

- 20.Huang H, Jiang X, Li Z, Li Y, Song CX et al (2013 Jul) TET1 plays an essential oncogenic role in MLL-rearranged leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 16(29):11994–11999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Jiang X, Hu C, Arnovitz S, Bugno J, Yu M et al miR-22 has a potent anti-tumour role with therapeutic potential in acute myeloid leukaemia.Nat Commun. 2016 Apr26;7:11452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Ittel A, Jeandidier E, Helias C, Perrusson N, Humbrecht C et al (2013 Dec) First description of the t(10;11)(q22;q23)/MLL-TET1 translocation in a T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, with subsequent lineage switch to acute myelomonocytic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 98(12):e166–e168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Jiang X, Hu C, Ferchen K, Nie J, Cui X et al Targeted inhibition of STAT/TET1 axis as a therapeutic strategy for acute myeloid leukemia.Nat Commun. 2017 Dec13;8(1):2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Cimmino L, Dolgalev I, Wang Y, Yoshimi A, Martin GH, et al. Restoration of TET2 Function Blocks Aberrant Self-Renewal and Leukemia Progression. Cell. 2017;170:1079–1095e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen KD, Jia G, Johansen JV, Pedersen MT, Rapin N, et al. Loss of TET2 in hematopoietic cells leads to DNA hypermethylation of active enhancers and induction of leukemogenesis. Genes Dev. 2015;29:910–922. doi: 10.1101/gad.260174.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solary E, Bernard OA, Tefferi A, Fuks F, Vainchenker W. The Ten-Eleven Translocation-2 (TET2) gene in hematopoiesis and hematopoietic diseases. Leukemia. 2014;28:485–496. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdel-Wahab O, Mullally A, Hedvat C, Garcia-Manero G, Patel J, et al. Genetic characterization of TET1, TET2, and TET3 alterations in myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2009;114:144–147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bejar R, Lord A, Stevenson K, Bar-Natan M, PérezLadaga A, et al. TET2 mutations predict response to hypomethylating agents in myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Blood. 2014;124:2705–2712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-582809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang T, Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Zhou J (2020 Mar) Expression and prognosis analysis of TET family in acute myeloid leukemia. Aging 25(6):5031–5047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Chen D, Maruschke M, Hakenberg O, Zimmermann W, Stief CG, Buchner A. TOP2A, HELLS, ATAD2, and TET3 Are Novel Prognostic Markers in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Urology. 2017;102:265e1–265e7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciesielski P, Jóźwiak P, Wójcik-Krowiranda K, Forma E, Cwonda Ł, et al. Differential expression of ten-eleven translocation genes in endometrial cancers. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317695017. doi: 10.1177/1010428317695017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bronowicka-Kłys DE, Roszak A, Pawlik P, Sajdak S, Sowińska A, Jagodziński PP. Transcript levels of teneleven translocation type 1–3 in cervical cancer and non-cancerous cervical tissues. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:3921–3927. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Damme M, Crompot E, Meuleman N, Maerevoet M, Mineur P et al Characterization of TET and IDH gene expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: comparison with normal B cells and prognostic significance.Clin Epigenetics. 2016 Dec7;8:132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Rawłuszko-Wieczorek AA, Siera A, Horbacka K, Horst N, Krokowicz P, Jagodziński PP. Clinical significance of DNA methylation mRNA levels of TET family members in colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:1379–1392. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1901-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dohner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010;115:453–474. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. Dec;25(4):402-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Abrams T, Connor A, Fanton C, Cohen SB, Huber T et al Preclinical Antitumor Activity of a Novel Anti-c-KIT Antibody-Drug Conjugate against Mutant and Wild-type c-KIT-Positive Solid Tumors.Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Sep1; 24(17):4297–4308 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Advani AS, Rodriguez C, Jin T, Jawde RA, Saber W et al Increased C-kit intensity is a poor prognostic factor for progression-free and overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed AML.Leuk Res. 2008Jun; 32(6):913–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Gao X, Lin J, Gao L, Deng A, Lu X, Li Y, Wang L, Yu L (2015) High expression of c-kit mRNA predicts unfavorable outcome in adult patients with t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS One. Apr 10;10(4):e0124241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Hoehn D, Medeiros LJ, Chen SS, Tian T, et al. CD117 Expression Is a Sensitive but Nonspecific Predictor of FLT3 Mutation in T Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and T/Myeloid Acute Leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137:213–219. doi: 10.1309/AJCPR3N3JMSYLPFG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woźniak J, Kopeć-Szlezak J (2004 Mar) c-Kit receptor (CD117) expression on myeloblasts and white blood cell counts in acute myeloid leukemia. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 58(1):9–16 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Auewarakul CU, Lauhakirti D, Promsuwicha O, Munkhetvit C (2006 Feb) C-kit receptor tyrosine kinase (CD117) expression and its positive predictive value for the diagnosis of Thai adult acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol 85(2):108–112 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Cheng J, Guo S, Chen S, Mastriano SJ, Liu C et al An extensive network of TET2-targeting MicroRNAs regulates malignant hematopoiesis.Cell Rep. 2013 Oct31;5(2):471–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Liu WJ, Tan XH, Luo XP, Guo BP, Wei ZJ et al (2014 Dec) Prognostic significance of Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (TET2) gene mutations in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma 55(12):2691–2698 [DOI] [PubMed]