Abstract

Objectives

To describe the epidemiological, clinical, and household transmission characteristics of pediatric COVID-19 cases in Shanghai, China.

Methods

Pediatric patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in Shanghai from March-May 2022 were enrolled in this retrospective, multicenter cohort study. The symptoms and the risk factors associated with disease severity were analyzed.

Results

In total, 2620 cases (age range, 24 days-17 years) were enrolled in this study. Of these, 1011 (38.6%) were asymptomatic, whereas 1415 (54.0%), 190 (7.3%), and 4 (0.2%) patients developed mild, moderate, and severe illnesses, respectively. Household infection rate was negatively correlated with household vaccination coverage. Children aged 0-3 years, those who are unvaccinated, those with underlying diseases, and overweight/obese children had a higher risk of developing moderate to severe disease than children aged 12-17 years, those who were vaccinated, those without any underlying disease, and those with normal weight, respectively (all P <0.05). A prolonged duration of viral shedding was associated with disease severity, presence of underlying diseases, vaccination status, and younger age (all P <0.05).

Conclusion

Children aged younger than 3 years who were not eligible for vaccination had a high risk of developing moderate to severe COVID-19 with a prolonged duration of viral shedding. Vaccination could protect children from COVID-19 at the household level.

Keywords: Omicron, SARS-CoV-2, Epidemiology, Pediatrics, Household transmission

Introduction

The Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) of the SARS-CoV-2, which is a variant of concern, was first detected in South Africa in November 2021 [1]. This variant of SARS-CoV-2 has become the most dominant variant of concern because it led to the fifth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide [2]. BA.2.2, a fast-spreading subvariant of the Omicron variant, triggered a wave of COVID-19 in Shanghai, China in February 2022. Although 90% of the Shanghai adult population has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, a total of 627,087 cases and 589 deaths were recorded in Shanghai as of June 24, 2022 [3,4]. China commenced a nationwide COVID-19 vaccination program for children and adolescents aged 3-17 years in July 2021; the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm Group Co., Ltd., China) and CoronaVac (Sinovac Biotech, Ltd., China) were approved for emergency use with a two-dose schedule and a spacing of 3-8 weeks. However, given the rapid spread of the Omicron subvariants and the relatively low vaccination coverage in children, a large number of pediatric cases were identified during the Omicron outbreak in Shanghai.

A series of strict public health and social measures were implemented under China's dynamic zero-COVID policy. These measures included extensive viral nucleic acid screening of the general population, organized by communities, combined with rapid antigen screening on a weekly basis, temporary lockdown of communities, and closure of schools with COVID-19 outbreaks. Makeshift hospitals, also known as Fangcang hospitals, were used for large-scale medical isolation of asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic patients. In these hospitals, low-level care of patients with nonsevere disease was adapted under the policy of “all those in need have been tested, and if positive, have been quarantined, hospitalized, or treated” [4,5].

Global data have shown that the Omicron wave is associated with a higher number of pediatric hospitalizations for COVID-19 than previous waves [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. As of July 29, 2022, there were approximately 57.8 million and 15,786 pediatric COVID-19 cases and deaths, respectively [12]. It has been clearly established that children and adolescents are as susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infections as adults but are more likely to be asymptomatic [13], [14], [15], [16]. However, little is known about the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in children and adolescents in China, especially regarding the transmission of COVID-19 under strict and comprehensive control strategies, such as school closures and containment measures. Thus, the aim of this study was to analyze the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of pediatric patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection hospitalized during the Omicron outbreak in Shanghai, China. In addition, we described the transmission patterns of COVID-19 during this period and identified the risk factors associated with the severity of COVID-19 and the duration of viral shedding.

Methods

The ethics committee of the Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the included children during the primary data collection process (No.2022SHL-KY-19-02). All data used in this study were deidentified. This study was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline [17].

Study setting and procedures

This was a retrospective, multicenter study, pediatric patients (aged <18 years) with SARS-CoV-2 infection who were admitted to five hospitals in Shanghai between March 30 and May 31, 2022 were included in this study. The five hospitals were Shanghai Renji Hospital South Campus, Shanghai New International Expo Center Makeshift Hospital, Jiading Makeshift Hospital, Changxingdao Makeshift Hospital, and Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center. The cases were identified through large-scale community viral nucleic acid screening or fever clinics and transferred to the previously mentioned hospitals for isolation and management. Children aged younger than 7 years; with mild, moderate, or severe symptoms; or with severe underlying diseases/conditions (e.g., tumors, congenital heart disease, hematologic diseases, and postorgan transplant) were considered to have an increased risk for disease progression and were referred to the designated hospitals for advanced care. Antiviral treatment was used when necessary. The remaining children were managed in makeshift hospitals. Oropharyngeal, nasal, or nasopharyngeal swabs were collected daily and tested for SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid using a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, which targets the ORF1ab and N regions of the nucleocapsid gene. Patients with clinical symptoms were followed up in the hospital until the discharge criterion of two consecutive negative PCR results (cycle threshold values for both genes ≥35) at least 24 hours apart was met [18].

The symptoms and severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children were classified according to the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Version 9) released by the National Health Commission and National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine on March 15, 2022 [18]: asymptomatic, mild (mild clinical symptoms and no pneumonia in chest radiology), moderate (fever, respiratory symptoms, and chest radiology findings suggesting pneumonia), and severe (high fever lasting >3 days, shortness of breath, oxygen saturation ≤93% in room air at rest, respiratory distress, drowsiness, convulsions, and feeding difficulties with signs of dehydration). Chest X-ray or computed tomography was performed if a patient was suspected to have pneumonia or show disease progression. Routine blood tests, liver function tests, and other examinations were performed when necessary. The diagnosis and treatment were based on a comprehensive analysis of epidemiological history, clinical manifestations, laboratory test results, and chest imaging findings.

Data collection

Patient data were extracted from electronic health records and collected through telephone interviews. For each child, the following information was obtained: age, sex, height, weight, history of underlying diseases, history of allergy, symptom duration, vaccination history, including the number of doses received (zero to two doses) and the type of vaccine received, and duration of viral shedding, which was defined as the duration from the date of symptom onset or the first positive PCR test result to the first day that there were two consecutive negative PCR tests results at least 24 hours apart. Household information on the number of family members and their infection and vaccination status, history of underlying diseases, and history of allergy were self-reported.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of interest was the clinical severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection (asymptomatic, mild, or moderate/severe). We used descriptive statistics, including mean (SD), median (interquartile range), ranges, counts, and proportions, to describe the epidemiological, clinical, and household transmission characteristics of hospitalized children with COVID-19 in Shanghai. The differences between groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis H test, and Student's t-test, as appropriate. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to examine the differences between groups when the cell numbers were less than five. Four age groups were prespecified (<3 years, 3-5 years, 6-11 years, and 12-17 years) based on the structure of the Chinese basic education system. Four body mass index (BMI) categories (underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese) were defined based on the World Health Organization growth charts for children [19].

A univariable logistic regression model was first used to evaluate the association between relevant risk factors (recruited hospital, sex, age group, BMI category, vaccination status, presence of underlying conditions, history of allergy, and other epidemiological and transmission factors) and the development of mild and moderate/severe symptoms. Factors with a P-value less than 0.05 and those of known clinical relevance were included for further multivariable logistic regression analysis to obtain an adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The final multivariable logistic regression model was adjusted for age, sex, BMI category, vaccination status, underlying conditions, and history of allergy. The association between vaccination status and selected clinical features was evaluated using multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age, sex, and BMI category. The risk factors associated with the duration of viral shedding were estimated using Poisson regression, adjusted for recruited hospital, age, sex, BMI category, vaccination status, underlying conditions, and clinical disease severity. All statistical analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.1.2). The statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Study participants

A total of 2620 children and adolescents with COVID-19 were included in this study (Supplementary Figure 1). The epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the included children and adolescents are shown in Table 1 . Of the included children, 2018 (77.0%) children were admitted to makeshift hospitals, and 602 (23.0%) were referred to the hospitals exclusively designated for pediatric cases. The mean (SD) age was 6.7 (4.1) years (range, 24 days-17 years), and 45.0% of them were female. Of the 1864 cases who provided in-depth epidemiological information, 526 reported underlying medical diseases (including rhinitis [222, 11.9%], eczema [145, 7.8%], recurrent respiratory tract infections [98, 5.3%], hives [37, 2.0%], bronchial asthma [31, 1.7%], and other diseases), and 229 cases reported a history of allergy (not mutually exclusive from underlying medical diseases). Regarding BMI, 61.9% (1621/2620) of the patients had available information on their BMI category and 944 (58.2%) of these had a normal weight.

Table 1.

Epidemiological, clinical, and transmission characteristics of hospitalized children with COVID-19 in Shanghai.

| [ALL] | <3 years | 3-5 years | 6-11 years | 12-17years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2620 | N = 664 | N = 601 | N = 663 | N = 692 | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) [range] | 6.7(4.1) [24 days - 17years] | ||||

| Recruited hospital | |||||

| Makeshift hospitals | 2018 (77.0%) | 255 (37.9%) | 519 (86.4%) | 596 (90.2%) | 648 (94.5%) |

| Designated hospitals | 602 (23.0%) | 417 (62.1%) | 82 (13.6%) | 65 (9.8%) | 38 (5.5%) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1180 (45.0%) | 275 (41.4%) | 268 (44.6%) | 312 (47.1%) | 325 (47.0%) |

| Male | 1440 (55.0%) | 389 (58.6%) | 333 (55.4%) | 351 (52.9%) | 367 (53.0%) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 18.5 (41.8) | 17.5 (3.4) | 20.3 (82.5) | 16.8 (3.3) | 19.2 (3.9) |

| BMI category | |||||

| Underweight | 170 (10.5%) | 39 (10.0%) | 58 (13.3%) | 41 (10.5%) | 32 (7.9%) |

| Normal weight | 944 (58.2%) | 155 (39.8%) | 243 (55.9%) | 258 (65.8%) | 288 (71.1%) |

| Overweight | 253 (15.6%) | 94 (24.2%) | 54 (12.4%) | 52 (13.3%) | 53 (13.1%) |

| Obese | 254 (15.7%) | 101 (26.0%) | 80 (18.4%) | 41 (10.5%) | 32 (7.9%) |

| Clinical severity | |||||

| Asymptomatic | 1011 (38.6%) | 80 (12.0%) | 198 (32.9%) | 354 (53.4%) | 379 (54.8%) |

| Mild | 1415 (54.0%) | 438 (66.0%) | 381 (63.4%) | 296 (44.6%) | 300 (43.4%) |

| Moderate | 190 (7.3%) | 143 (21.5%) | 22 (3.7%) | 13 (2.0%) | 12 (1.7%) |

| Severe | 4 (0.2%) | 3 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Vaccination status | |||||

| Unvaccinated | 1162 (62.0%) | 589 (100%) | 384 (81.7%) | 130 (33.2%) | 59 (14.0%) |

| One dose | 69 (3.7%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (6.6%) | 27 (6.9%) | 11 (2.6%) |

| Two doses | 642 (34.3%) | 0 (0%) | 55 (11.7%) | 235 (59.9%) | 352 (83.4%) |

| Vaccine types | |||||

| CoronaVac | 205 (45.6%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (45.2%) | 83 (50.9%) | 103 (42.0%) |

| BBIBP-CorV | 245 (54.4%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (54.8%) | 80 (49.1%) | 142 (58.0%) |

| History of allergy | |||||

| No | 1584 (87.4%) | 504 (88.3%) | 386 (83.9%) | 359 (90.0%) | 335 (87.5%) |

| Yes | 229 (12.6%) | 67 (11.7%) | 74 (16.1%) | 40 (10.0%) | 48 (12.5%) |

| Underlying conditionsa | |||||

| None | 1338 (71.8%) | 454 (78.7%) | 313 (67.0%) | 276 (68.3%) | 295 (70.9%) |

| Bronchial asthma | 31 (1.7%) | 2 (0.4%) | 13 (2.8%) | 5 (1.2%) | 11 (2.8%) |

| Rhinitis | 222 (11.9%) | 17 (3.0%) | 59 (12.7%) | 64 (15.8%) | 82 (19.7%) |

| Eczema | 145 (7.8%) | 55 (9.5%) | 40 (8.6%) | 23 (5.7%) | 27 (6.7%) |

| Hives | 37 (2.0%) | 12 (2.1%) | 12 (2.6%) | 5 (1.2%) | 8 (2.0%) |

| Recurrent respiratory tract infection | 98 (5.3%) | 19 (3.3%) | 26 (5.6%) | 33 (8.2%) | 20 (5.0%) |

| Tumor | 14 (0.8%) | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.7%) | 8 (2.0%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (0.7%) | 9 (1.6%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Seizures | 9 (0.5%) | 3 (0.5%) | 3 (0.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Otherb | 107 (6.3%) | 41 (9.1%) | 31 (6.7%) | 23 (6.1%) | 12 (3.5%) |

| With clear exposure historyc | |||||

| Yes | 1359 (52.2%) | 378 (57.0%) | 337 (56.1%) | 337 (50.9%) | 307 (45.3%) |

| No | 1244 (47.8%) | 285 (43.0%) | 264 (43.9%) | 325 (49.1%) | 370 (54.7%) |

| Possible location of infection | |||||

| Family | 1195 (64.2%) | 344 (58.1%) | 324 (70.7%) | 247 (62.5%) | 280 (67.3%) |

| Community | 666 (35.8%) | 248 (41.9%) | 134 (29.3%) | 148 (37.5%) | 136 (32.7%) |

| Symptoms before PCR test positive | |||||

| No | 475 (26.9%) | 92 (18.5%) | 111 (24.4%) | 103 (25.8%) | 169 (40.8%) |

| Yes | 1291 (73.1%) | 406 (81.5%) | 343 (75.6%) | 297 (74.2%) | 245 (59.2%) |

| Is the first COVID-19 case in household | |||||

| No | 1222 (71.3%) | 356 (76.2%) | 313 (69.7%) | 259 (65.6%) | 294 (72.8%) |

| Yes | 493 (28.7%) | 111 (23.8%) | 136 (30.3%) | 136 (34.4%) | 110 (27.2%) |

| Household infection rated, %, mean (SD) | 85.1 (22.9) | 89.0 (19.7) | 84.1 (23.5) | 84.1 (23.2) | 82.6 (24.8) |

| Household vaccination ratee, %, mean (SD) | 81.8 (29.5) | 66.3 (22.6) | 79.0 (29.6) | 85.9 (28.4) | 96.1 (28.6) |

| Duration of viral sheddingf, days, mean (SD) | 11.0 (4.2) | 12.6 (3.8) | 10.7 (3.7) | 10.3 (3.9) | 10.5 (4.7) |

| Average symptom duration, days, mean (SD) | 3.1 (3.3) | 3.3 (2.6) | 2.8 (3.5) | 3.3 (4.0) | 2.7 (3.3) |

| Peak fever temperature, °C, mean (SD) | 39.0 (0.8) | 39.3 (0.7) | 39.1 (0.8) | 38.9 (0.8) | 38.8 (0.8) |

| Presenting symptomsg, N (%, [95% CI]) | |||||

| Systemic | |||||

| Fever | 1507 (93.7, [92,6-95.0]) | 537 (90.9%) | 386 (95.8%) | 292 (94.8%) | 292 (93.8%) |

| Fatigue | 54 (3.4, [2.5-4.2]) | 10 (1.7%) | 14 (3.5%) | 15 (4.9%) | 15 (4.9%) |

| Muscle pains | 37 (2.3, [1.6-3.0]) | 1 (0.2%) | 11 (2.7%) | 8 (2.6%) | 17 (5.5%) |

| Headache | 31 (2.0, [1.3-2.6]) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (1.7%) | 7 (2.3%) | 17 (5.5%) |

| Dizziness | 27 (1.7, [1.1-2.3]) | 2 (0.3%) | 4 (1.0%) | 8 (2.6%) | 13 (4.2%) |

| Chills or shivers | 9 (0.6, [0.2-0.9]) | 4 (0.7%) | 1 (0.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Respiratory | |||||

| Cough | 653 (40.6, [38.3-43.1]) | 253 (42.8%) | 134 (33.3%) | 132 (43.0%) | 134 (43.5%) |

| Runny nose | 181 (11.2, [9.7-12.8]) | 55 (9.3%) | 56 (13.9%) | 39 (12.7%) | 31 (10.1%) |

| Expectoration | 164 (10.2, [8.7-11.7]) | 54 (9.1%) | 27 (6.7%) | 36 (11.7%) | 47 (15.3%) |

| Sore throat | 116 (7.2, [6.0-8.5]) | 25 (4.2%) | 18 (4.5%) | 36 (11.7%) | 37 (12.0%) |

| Stuffy nose | 113 (7.0, [5.8-8.3]) | 39 (6.6%) | 22 (5.5%) | 27 (8.8%) | 25 (8.1%) |

| Shortness of breath | 5 (0.3, [0.04-0.6]) | 4 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Gastrointestinal | |||||

| Abnormal defecation | 119 (7.4, [6.1-8.7]) | 78 (13.2%) | 26 (6.5%) | 12 (3.9%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| Vomiting | 86 (5.4, [4.3-6.5]) | 42 (7.1%) | 21 (5.2%) | 15 (4.9%) | 8 (2.6%) |

| Loss of appetite | 52 (3.2, [2.4-4.1]) | 12 (2.0%) | 15 (3.7%) | 13 (4.2%) | 12 (3.9%) |

| Abdominal pain | 32 (2.0,[1.3-2.7]) | 5 (0.9%) | 16 (4.0%) | 6 (2.0%) | 5 (1.6%) |

| Nausea | 16 (1.0, [0.5-1.5]) | 2 (0.3%) | 4 (1.0%) | 6 (2.0%) | 4 (1.3%) |

| Other | |||||

| Skin rash | 32 (2.0, [1.4-2.7]) | 28 (4.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Clear throat | 13 (0.8, [0.4-1.3]) | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.7%) | 5 (1.6%) | 4 (1.3%) |

| Sleeping Disorder | 6 (0.4, [0.1-0.7]) | 4 (0.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified. BMI, body mass index; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

The number of cases presented with at least one underlying condition among 1864 cases. Multiple presenting conditions were possible.

Other comorbidities included conjunctivitis, tic disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, diabetes, hypertension, febrile convulsion, lung disease, kidney disease, and disability.

Children have been exposed to the individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 or closely contacted with SARS-CoV-2 carriers.

Calculated as the number of household members infected with SARS-CoV-2 divided by the total number of family members.

Calculated as the number of vaccinated household members divided by the total number of family members.

Duration of viral shedding was defined as the duration from the date of symptom onset or the first positive PCR test result to the first day that there were two consecutive negative PCR tests results at least 24 hours apart.

Multiple presenting symptoms were possible. The number of cases presenting at least one symptom among 1609 symptomatic cases.

Clinical manifestation of COVID-19 in children and adolescents

Of the 2620 pediatric cases included in this study, 1011 (38.6%) were asymptomatic and 1415 (54.0%), 190 (7.3%), and 4 (0.2%) had mild, moderate, and severe disease, respectively. Regarding the referral of patients to hospitals, 1003 (99.2%) of the 1011 asymptomatic patients and 1015 of the 1415 patients with mild symptoms were admitted into the makeshift hospitals (Supplementary Table 1). All moderate and severe pediatric cases were admitted to the designated hospitals with advanced management and treatment protocols.

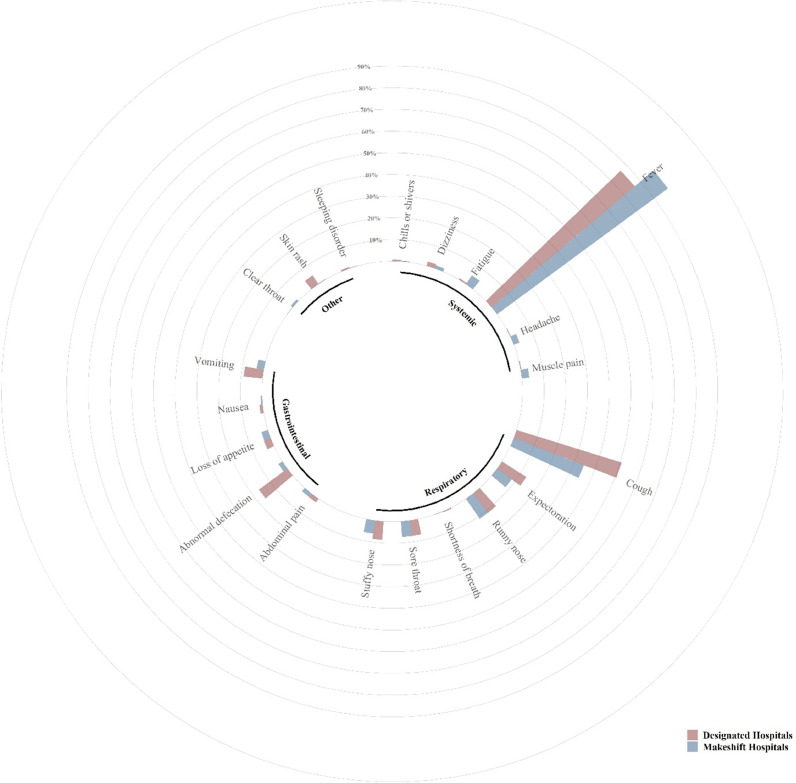

List of symptoms reported by pediatric cases with COVID-19 during the Omicron wave in Shanghai was summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Of the 1609 symptomatic patients, 1507 experienced fevers with a mean fever spike of 39.0 ± 0.8°C (range: 37.6-41.0°C). The symptom duration was 3.1 (3.3) days. The top five most common symptoms among symptomatic cases were fever (93.7%, 95% CI, 92.6-95.0), cough (40.6%, 95% CI, 38.3-43.1), runny nose (11.2%, 95% CI, 9.7-12.8), expectoration (10.2%, 95% CI, 8.7-11.7), and abnormal defecation (7.40%, 95% CI, 6.1-8.7; Table 1; Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

The prevalence of symptoms reported by pediatric cases infected during the Omicron wave in Shanghai and admitted to the designated hospitals and makeshift hospitals. Symptoms were grouped into four groups: systemic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and other. The percentage of one symptom among all symptomatic cases was calculated and compared.

Role of children and adolescents in household transmission

A total of 1359 (52.2%) cases reported having a clear history of exposure to COVID-19, 1195 (64.2%) reported that they had been exposed to at least one adult in their household with confirmed COVID-19, 1291 (73.1%) had typical COVID-19 symptoms before a positive PCR test result, and 493 (28.7%) were the first COVID-19 cases in their household (Table 1).

A total of 1002 cases had available information on household transmission and the vaccination status of their household contacts (n = 5123). The mean household infection rate (calculated as the number of household members infected with SARS-CoV-2 divided by the total number of family members) was 85.1%. The household infection rate decreased with age (Table 1), whereas the household vaccination rate increased with age.

Risk factors for mild or moderate symptoms

Children aged <3 years had a significantly higher risk of having mild (odds ratio [95% CI]; 2.62 [1.51-4.94]; Table 2 ) and moderate/severe symptoms (11.07 [3.68-33.25]) than children aged 12-17 years old. Children who were overweight (2.20 [1.17-4.15]) or obese (2.32 [1.24-4.33]) had a higher risk of developing moderate/severe illness than those with a normal weight. Unvaccinated children had a higher risk of having mild (1.88 [1.32-2.68]) and moderate/severe symptoms (3.68 [1.53-8.82]) versus being asymptomatic than those who received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Children with comorbidities had a significantly higher risk of having mild symptoms (1.64 [1.20-2.24]) and moderate/severe symptoms (3.51 [2.11-5.85]) than those without comorbidities. Children with a history of recurrent respiratory tract infections had a higher risk of developing mild symptoms than those without (2.91 [1.38-6.16]; Supplementary Table 3). Unadjusted results were reported in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 2.

Risk factors associated with clinical severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Asymptomatic | Mild | Moderate/severea | Mild vs asymptomatic | Moderate /severe vs asymptomatic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1011 | N = 1415 | N = 194 | Adjusted odds ratiob (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratiob (95% CI) | |

| Age group | |||||

| <3 years | 80 (7.9%) | 438 (31.0%) | 146 (75.3%) | 2.62 [1.51-4.94] | 11.07 [3.68-33.25] |

| 3-5 years | 198 (19.6%) | 381 (26.9%) | 22 (11.3%) | 1.27[0.83-1.94] | 1.14 [0.40-3.27] |

| 6-11 years | 354 (35.0%) | 296 (20.9%) | 13 (6.70%) | 0.90 [0.64-1.25] | 0.94 [0.36-2.47] |

| 12-17 years | 379 (37.5%) | 300 (21.2%) | 13 (6.70%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 479 (47.4%) | 631 (44.6%) | 70 (36.1%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Male | 532 (52.6%) | 784 (55.4%) | 124 (63.9%) | 1.17 [0.90-1.53] | 1.44 [0.92-2.34] |

| BMI category | |||||

| Normal weight | 196 (65.1%) | 710(59.1%) | 38 (31.9%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Underweight | 27 (9.0%) | 130 (10.8%) | 13 (10.9%) | 1.22 [0.77-1.94] | 2.01 [0.92- 4.44] |

| Overweight | 39 (13.0%) | 183 (15.2%) | 31 (26.1%) | 1.02 [0.69-1.52] | 2.20 [1.17-4.15] |

| Obese | 39 (13.0%) | 178 (14.8%) | 37 (31.1%) | 0.94 [0.62-1.42] | 2.32 [1.24-4.33] |

| Vaccination status | |||||

| Vaccinated ≥1 dose | 200 (64.1%) | 493 (36.0%) | 18 (9.4%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Unvaccinated | 112 (35.9%) | 876 (64.0%) | 174 (90.6%) | 1.88 [1.32-2.68] | 3.68 [1.53-8.82] |

| Underlying conditions | |||||

| No | 247 (78.4%) | 967 (71.1%) | 124 (65.6%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 68 (21.6%) | 393 (28.9%) | 65 (34.4%) | 1.64 [1.20-2.24] | 3.51 [2.11-5.85] |

| History of allergy | |||||

| No | 270 (90.9%) | 1150 (86.4%) | 164 (88.6%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 27 (9.1%) | 181 (13.6%) | 21 (11.4%) | 1.56 [0.99-2.45] | 1.37 [0.70-3.07] |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; Ref., reference.

Four severe cases were grouped with the moderate cases.

Adjusted for age, sex, BMI category, vaccination status, underlying conditions, and history of allergy. Recruited hospital type was not adjusted in the model as moderate and severe cases were all treated in the designated hospital.

Table 3.

The association between vaccination status and clinical features in 1284 children aged 3 years or older who were eligible for COVID-19 vaccination.

| [ALL] | Vaccinated | Unvaccinated | Unvaccinated vs vaccinated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1284 | N = 711 | N = 573 | Adjusted odds ratioa (95% confidence interval) | |

| Age group | 8.00 (3.5) | 9.77 (3.0) | 5.81 (2.7) | |

| 3-5 years | 470 (36.6%) | 86 (12.1%) | 384 (67.0%) | 30.24 [20.57-44.46] |

| 6-11 years | 392 (30.5%) | 262 (36.8%) | 130 (22.7%) | 3.27 [2.27-4.72] |

| 12-17 years | 422 (32.9%) | 363 (51.1%) | 59 (10.3%) | Ref. |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 579 (45.1%) | 324 (45.6%) | 2545 (44.5%) | Ref. |

| Male | 7705 (54.9%) | 387 (54.4%) | 3188 (55.5%) | 0.97 [0.73-1.29] |

| BMI category | ||||

| Normal weight | 777 (64.4%) | 458 (67.3%) | 319 (60.8%) | Ref. |

| Underweight | 130(10.8%) | 69 (10.1%) | 61 (11.6%) | 0.85 [0.53-1.35] |

| Overweight | 151 (12.5%) | 89 (13.1%) | 62 (11.8%) | 0.86 [0.55-1.33] |

| Obese | 148(12.3%) | 65 (9.6%) | 83 (15.8%) | 1.08 [0.69-1.69] |

| Clinical Severity | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 285 (22.2%) | 200 (28.1%) | 85 (14.8%) | Ref. |

| Mild | 951 (74.1%) | 493 (69.3%) | 458 (79.9%) | 1.88 [1.32-2.70] |

| Moderate b | 48 (3.7%) | 18 (2.6%) | 30 (5.3%) | 3.58 [1.50-8.54] |

| Systemic symptoms | ||||

| No | 260 (21.1%) | 186 (27.2%) | 74 (13.5%) | Ref. |

| Yes | 973 (78.9%) | 499 (72.8%) | 474 (86.5%) | 1.93 [1.33-2.81] |

BMI, body mass index; Ref., reference.

Adjusted for age, sex, BMI category, and clinical severity of symptoms.

One severe case was grouped with the moderate cases.

cP-values estimated from Student's t-test

Vaccination status and clinical features

Among the 1284 children aged ≥3 years who were eligible for COVID-19 vaccination, 573, 69, and 642 were unvaccinated, received one vaccine dose, and two vaccine doses, respectively (Table 1). Of the 450 children who provided information on the vaccine type, 205 received the CoronaVac vaccine and 245 received the BBIBP-CorV vaccine. The full vaccination rate (received two doses of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine) varied considerably by age and increased with age, from 11.7% in those aged 3-5 years to 83.4% in those aged 12-17 years. The household vaccination coverage (calculated as the number of vaccinated household members divided by the total number of family members) was negatively correlated with the household transmission rate (Spearman rho = -0.3, P <0.05).

The association between the vaccination status and clinical features of the 1284 children eligible for vaccination are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Unvaccinated children had a significantly higher risk of having mild symptoms (1.88 [1.32-2.70]) and moderate/severe symptoms (3.58 [1.50-8.54]) than children who received at least one vaccine dose. In addition, unvaccinated children had a greater likelihood of developing systemic symptoms than vaccinated children (1.93 [1.32-2.81]).

The duration of viral shedding and its risk factors

The duration of viral shedding in symptomatic children (11.6, 95% CI: 11.1-12.1, days) was longer than in asymptomatic children (10.0, 95% CI: 9.7-10.3, days; data not shown). The duration of viral shedding was longest among children aged <3 years and shortest among those aged 3-5 years (Table 4 ). The mean duration of viral shedding in unvaccinated children was 1.42 (0.23) days longer than that in those received at least one dose of a vaccine (P <0.001). In addition, the mean duration of viral shedding in patients with comorbidities was 0.56 (0.19) days longer than that in those without comorbidities (Table 4, P = 0.002).

Table 4.

Risk factors associated with the duration of viral shedding

| Duration of viral sheddinga | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean difference (days,SD) | P-value b | |

| Recruited hospital | ||

| Makeshift hospital | Ref. | Ref. |

| Designated hospital | 1.53 (0.29) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | Ref. | Ref. |

| Male | -0.23 (0.16) | 0.15 |

| Age group, years | ||

| <3 years | 0.71 (0.29) | 0.01 |

| 3-5 years | -0.92 (0.27) | <.001 |

| 6-11 years | -0.50 (0.26) | 0.04 |

| 12-17 years | Ref. | Ref. |

| Vaccination status | ||

| Unvaccinated | 1.42 (0.23) | <.001 |

| Vaccinated (at least one dose) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Comorbidities | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 0.56 (0.19) | 0.002 |

| Clinical severity | ||

| Asymptomatic | Ref. | Ref. |

| Mild | 0.78 (0.22) | <.001 |

| Moderate or severe c | 2.39 (0.41) | <.001 |

BMI, body mass index; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Duration of viral shedding was defined as the duration from the date of symptom onset or the first positive PCR test result to the first day that there were two consecutive negative PCR tests results at least 24 hours apart.

P-values obtained from multiple regression adjusted for recruited hospital, age, sex, BMI category, vaccination status, comorbidities, and clinical severity.

Four severe cases were grouped with the moderate cases.

Discussion

In this multicenter observational study, we investigated the epidemiological characteristics, clinical manifestations, and features of the household transmission of COVID-19 among children and adolescents during the Omicron outbreak of the disease in Shanghai, China. In the study cohort of 2620 pediatric patients with COVID-19, over 92% of the cases were asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic. Most of the asymptomatic patients were aged 6-17 years. Among all cases with moderate to severe symptoms, 75.3% were aged 0-3 years. For symptomatic patients, the mean duration of initial symptoms was approximately 3 days, and the most common symptoms were fever, cough, and runny nose. Gastrointestinal and other symptoms were not common in all age groups but were somewhat frequently reported among children aged younger than 3 years. The study results also indicated that children aged younger than 3 years, unvaccinated children, and those with at least one underlying disease had as significantly higher risk of having mild to moderate/severe symptoms than children aged older than 3 years, vaccinated children, and those without any underlying disease, respectively.

The duration of viral shedding decreased with age, ranging from 12.6 days among patients aged younger than 3 years to 10.5 days among those aged older than 3 years. A prolonged duration of viral shedding was associated with a higher disease severity, being unvaccinated, and having underlying diseases. Noticeably, the duration of viral shedding among the pediatric patients managed in the makeshift hospitals was generally longer than that reported for asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic adults (mean of 6 days) infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the same period in Shanghai [20]. In addition, the results also indicated that children with a history of recurrent respiratory tract infections had a higher risk of developing mild and moderate/severe symptoms than those without such history. Further studies on the mechanisms involved in the association between specific underlying diseases and the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children are needed.

The data of this study revealed that children and adolescents in Shanghai were susceptible to Omicron BA.2.2 infection. However, most of the patients were mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic, as reported in other part of the world. In Shanghai, all children infected with SARS-CoV-2 who had an elevated risk of developing severe diseases were triaged and transferred to the nearest designated hospitals for comprehensive medical management. In general, the mortality, hospitalization, and intensive care unit entry rates in Shanghai during in the Omicron BA.2-dominant wave were lower than those reported in Hong Kong [11,21]. This may be partly explained by the effective triage and management actions that were implemented when a pediatric COVID-19 case was identified in Shanghai [4].

In current study, unvaccinated children aged younger than 3 years old accounted for most of the pediatric patients who developed moderate infection. All four patients with severe COVID-19 were unvaccinated. Children aged ≥3 years who were eligible for COVID-19 vaccination were less likely to develop moderate to severe symptoms. The vaccination coverage increased with age, from 18.3% in those aged 3-5 years to 86.0% in those aged 12-17 years. There was no difference in the effects of the CoronaVac and BBIBP-CorV vaccines on reducing the severity of illness and shortening the duration of viral shedding. The data from Hong Kong showed that [22] one or two doses of inactivated vaccine is beneficial in reducing the severity of symptoms and the duration of viral shedding. Although vaccination is efficacious in preventing COVID-19 complications, reluctance among parents in mainland China regarding their children receiving vaccination has been reported since the July 2021 rollout [23]. Therefore, more awareness campaigns are needed to promote COVID-19 vaccination among children and their parents.

The household infection rate in this study was 85.1%, which was higher than that reported in the United States during the Omicron-dominant wave [24]. This high household infection rate could be attributed to the complete lockdown of Shanghai during the study period, leading to more frequent contact between family members than during the prelockdown period. We also observed a significantly negative correlation between household vaccination coverage and household transmission rate, highlighting the protective role of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. This is in line with previous findings in England [25,26] and Israel [27] that the risk of transmission in households with children was as high as that in households with only adults and that vaccination reduced the household transmission rate.

Our study revealed that the mean household vaccination coverage among patients treated in the makeshift hospitals was higher than that among those treated in the designated hospitals. This finding might be related to the local triage protocol, which involves direct referral of all children aged younger than 3 years, who are not eligible for COVID-19 vaccination, to the designated hospitals.

This study had several strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the largest multicenter observational cohort study of pediatric COVID-19 cases in mainland China that focused not only on the epidemiological and clinical data but also on household transmission patterns of children and adolescents infected with SARS-CoV-2. Second, we analyzed the association between the household transmission pattern and vaccination status. The results of this analysis provided insights into the spread of COVID-19 during the strict lockdown period in Shanghai and may facilitate future updates of COVID-19 prevention and control policies in China. This study also had some limitations as well. First, only a fraction of all pediatric COVID-19 cases in Shanghai were included in this study; thus, the results may not be generalizable to all children and adolescents in Shanghai. Second, most of the data used were self-reported and thus prone to reporting bias. Third, 1002 of 2620 pediatric cases provided household virus transmission information, which may have introduced bias and led to the overestimation of the household infection rate. Fourth, there may have been some heterogeneity in the swab specimen collection processes and among specimen types. These could influence the PCR results and thus affect the accurate calculation of viral shedding duration.

Although the outbreak of the Omicron BA 2.2 wave of COVID-19 in Shanghai was shut down since June 2022, the chances for major outbreaks of Omicron in other parts of China are high. Thus, appropriate preparation for such outbreaks is necessary. The Omicron outbreak in Shanghai shows that to maintain the dynamic zero-COVID policy or in the era of social reopening in China, further campaigns for vaccination strategies, in combination with effective triage and treatment of cases at elevated risk for COVID-19 development, are critical for preventing the spread of COVID-19 in pediatric populations and the development of severe illnesses. For children who have an increased risk of developing moderate or severe symptoms of COVID-19, efficient triage strategies should be implemented immediately in addition to proper referral to designated hospitals for advanced clinical care and treatment.

Conclusion

This retrospective, multicenter cohort study described the epidemiological, clinical, and household transmission characteristics of pediatric cases and household contacts with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Shanghai during the Omicron outbreak of the disease. Our study showed that children aged younger than 3 years and children who were unvaccinated, overweight, or had underlying diseases were susceptible to the Omicron infection. These findings may facilitate the development of future COVID-19 prevention and control strategies in China.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant number 2022ZYLCYJ05-5), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 72211530040, 71520107003, and 71931008), and the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (grant number shslczdzk04101).

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of the Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine approved this study and the written informed consent from parents during primary data collection process was obtained (No.2022SHL-KY-19-02). All data used in the current study were deidentified.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the children and their parents that participated in the cohort. Jianer Yu and Jiahui Lu provided important insights into the design of the research proposal. Jinjun Ran offered help in data analysis. Lirong Huang, Mingge Hu, Lili Zhou, Yajuan Wang, Shiping Shen, Zhaopeng Han, Peng Wang, Lina Geng, Peng Xue, Sujing Wang, Shuxiao Shi, Ying Dong, Minzhi Chen, and Yani Wu helped to collect information from the electronic health records and assisted in telephone interviews.

Author contributions

Mrs. Liu, Dr. Xu, and Dr. Piao had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Zhong L., Xue, Zhong W., Zheng, Zhou W., Yu, and Wang, Yin. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Xu, Liu, and Piao. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Zhong W., Zhong L., Xue, Zheng, Yu, Wang, Yin, and Zhou W. Statistical analysis: Xu and Li. Obtained funding: Zhong L., Xue, Zhong W., Zheng, Zhou, Yu, Wang, and Yin. Administrative, technical, or material support: Shi, Huang, Zhou H., Yang, Liu, Wu, and He.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2023.01.030.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Viana R, Moyo S, Amoako DG, Tegally H, Scheepers C, Althaus CL, et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature. 2022;603:679–686. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants, https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/;2022; 2022 [Accessed 25 May 2022].

- 3.Information Office of Shanghai Municipality. Shanghai reports on the prevention and control of COVID-19, https://www.shio.gov.cn/TrueCMS/shxwbgs/2022n_6y/2022n_6y.html; 2022 [accessed 29 July 2022].

- 4.Zhang X, Zhang W, Chen S. Shanghai's life-saving efforts against the current omicron wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2022;399:2011–2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00838-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai J, Deng X, Yang J, Sun K, Liu H, Chen Z, et al. Modeling transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in China. Nat Med. 2022;28:1468–1475. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01855-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdullah F, Myers J, Basu D, Tintinger G, Ueckermann V, Mathebula M, et al. Decreased severity of disease during the first global omicron variant Covid-19 outbreak in a large hospital in tshwane, South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;116:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belay ED, Godfred-Cato S. SARS-CoV-2 spread and hospitalisations in paediatric patients during the omicron surge. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:280–281. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cloete J, Kruger A, Masha M, du Plessis NM, Mawela D, Tshukudu M, et al. Paediatric hospitalisations due to COVID-19 during the first SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) variant wave in South Africa: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:294–302. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00027-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink EL, Robertson CL, Wainwright MS, Roa JD, Lovett ME, Stulce C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of neurologic manifestations in hospitalized children diagnosed with acute SARS-CoV-2 or MIS-C. Pediatr Neurol. 2022;128:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iuliano AD, Brunkard JM, Boehmer TK, Peterson E, Adjei S, Binder AM, et al. Trends in disease severity and health care utilization during the early omicron variant period compared with previous SARS-CoV-2 high transmission periods - United States, December 2020–January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:146–152. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung PH, Chan CP, Jin DY. Lessons learned from the fifth wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong in early 2022. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:1072–1078. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2060137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations Children's Fund. COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths: age- and sex-disaggregated data, https://data.unicef.org/resources/covid-19-confirmed-cases-and-deaths-dashboard/; 2022 (accessed 25 May 2022).

- 13.Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, Ye C, Zou X, Zhang Z, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:911–919. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawood FS, Porucznik CA, Veguilla V, Stanford JB, Duque J, Rolfes MA, et al. Incidence rates, household infection risk, and clinical characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and adults in Utah and New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:59–67. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han MS, Choi EH, Chang SH, Jin BL, Lee EJ, Kim BN, et al. Clinical characteristics and viral RNA detection in children with coronavirus disease 2019 in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:73–80. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siebach MK, Piedimonte G, Ley SH. COVID-19 in childhood: transmission, clinical presentation, complications and risk factors. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56:1342–1356. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ChinaNationalHealthCommission. Diagnosis and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia (trial version 9), http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202203/b74ade1ba4494583805a3d2e40093d88.shtml; 2022 [accessed 25 May 2022].

- 19.de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–667. doi: 10.2471/blt.07.043497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith DJ, Hakim AJ, Leung GM, Xu W, Schluter WW, Novak RT, et al. COVID-19 mortality and vaccine coverage - Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China, January 6, 2022-March 21, 2022. China CDC Wkly. 2022;4:288–292. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2022.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He G, Zhu S, Fu D, Xiao J, Zhao J, Lin Z, et al. Association between COVID-19 vaccination coverage and case fatality ratio: a comparative study — Hong Kong SAR, China and Singapore, December 2021–March 2022. China CDC Wkly. 2022;4:649–654. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2022.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Wen W, Chen C, Tang J, Wang C, Zhou M, et al. Explore the attitudes of children and adolescent parents towards the vaccination of COVID-19 in China. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:122. doi: 10.1186/s13052-022-01321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker JM, Nakayama JY, O'Hegarty M, McGowan A, Teran RA, Bart SM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant transmission within households - four U.S. Jurisdictions, November 2021-February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:341–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7109e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris RJ, Hall JA, Zaidi A, Andrews NJ, Dunbar JK, Dabrera G. Effect of vaccination on household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in England. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:759–760. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2107717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall JA, Harris RJ, Zaidi A, Woodhall SC, Dabrera G, Dunbar JK. HOSTED-England's Household Transmission Evaluation Dataset: preliminary findings from a novel passive surveillance system of COVID-19. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50:743–752. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prunas O, Warren JL, Crawford FW, Gazit S, Patalon T, Weinberger DM, et al. Vaccination with BNT162b2 reduces transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to household contacts in Israel. Science. 2022;375:1151–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.abl4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.