Abstract

Background:

African Americans (AAs) experience high rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes relative to Whites. Differential in utero exposure to environmental chemicals and psychosocial stressors may explain some of the observed health disparities, as exposures to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and experiences of discrimination have been linked to adverse birth outcomes. Few studies have examined chemicals and non-chemical stressors together as an exposure mixture, which may better reflect real-life exposure patterns. Here, we adapted methods designed for the analysis of exposure mixtures to examine joint effects of PFAS and psychosocial stress on birth outcomes among AAs.

Methods:

348 participants from the Atlanta African American Maternal-Child cohort were included in this study. Four PFAS were measured in first trimester serum samples. Self-report questionnaires were administered during the first trimester and were used to assess psychosocial stress (perceived stress, depression, anxiety, gendered racial stress). Quantile g-computation and Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) were used to estimate the joint effects between PFAS and psychosocial stressors on gestational age at delivery and birthweight for gestational age z-scores. All models were adjusted for maternal education, maternal age, parity, and any alcohol, tobacco and marijuana use.

Results:

Our analytic sample included a socioeconomically diverse group of pregnant women, with 79% receiving public health insurance. In quantile g-computation models, a simultaneous one-quartile increase in all PFAS, perceived stress, depression, anxiety, and gendered racial stress was associated with a reduction in birthweight z-scores (mean change per quartile increase = −0.24, 95% confidence interval= −0.43, −0.06). BKMR similarly showed that increasing all exposures in the mixture was associated with a modest decrease in birthweight z-scores, but not a reduced length of gestation.

Discussion:

Using methods designed for analyzing exposure mixtures, we found that a simultaneous increase in in utero PFAS and psychosocial stressors was associated with reduced birthweight for gestational age z-scores.

Keywords: PFAS, stress, joint effects, mixtures, pregnancy

1. Introduction

Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of man-made chemicals widely used to make products that are water and grease resistant.1 PFAS are found in non-stick cookware, textiles, as well as carpeting, food packaging, and sweat resistant clothing.1 PFAS are known as “forever chemicals” because they do not easily degrade in the environment,1 subsequently leading to a pervasive public health problem in the United States (US) and globally. Representative studies show that everyone in the US has detectable levels of certain PFAS.2 These chemicals are detected in breastmilk, cord blood, and the placenta, often times at higher levels in the infant relative to the mother.3–5 PFAS exposure has been linked to a wide array of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth, reduced fetal growth, and pregnancy complications.6,7

Psychosocial stressors are also widely prevalent during pregnancy and increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Pregnant people who experience depression, anxiety, stressful life events, and discrimination are more likely to deliver preterm relative to those who did not experience these stressors.8–12 Importantly, experiences of different psychosocial stressors are not isolated and often co-occur. For example, individuals who experience stressful life events and perceived stress have more symptoms of depression relative to their lower stress counterparts.13 Racial discrimination is recognized as a distinct stressor that leads to depression and anxiety14 and physiological manifestations of stress, such as high blood pressure.15 Further, experiences of stressors are not evenly distributed across the population, as African Americans (AAs) experience psychosocial stress at rates much higher than Whites.16 AAs also disproportionally experience elevated rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes, and socioeconomic status alone does not fully explain the observed disparities.17

“Double jeopardy” of exposure to environmental hazards and social stressors can intensify existing disparities in maternal and child health.18 From an environmental justice perspective, relative to Whites and independent of socioeconomic status, AAs have higher detectable levels of personal care-product related chemicals.19 While a recent study found that AAs have lower levels of the certain PFAS (perfluorooctanoic acid [PFOA], perfluorononanoic acid [PFNA], perfluorooctanesulfonic acid [PFOS]) relative to Whites,20 levels of perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), a replacement for PFOS, was detected at higher levels in AAs.21 AAs may still be at a risk for cumulative exposures over time, as they may be more likely to eat processed and packaged food from containers that are coated with PFAS,20 relative to Whites. Furthermore, the relationship between PFNA and corticotrophin-releasing hormone, a biomarker of relevance for preterm birth, was stronger among those who experienced depression, stressful life events, financial strain, and food insecurity, suggesting a joint effect of PFAS and social stressors.22

To date, no studies have examined cumulative effects of PFAS and psychosocial stressors on adverse pregnancy outcomes in AAs, which may be critically important given the high rates of these exposures and outcomes among this population. Numerous studies have examined the cumulative or joint effects of chemical and non-chemical stressors on adverse pregnancy outcomes.23–26 These studies find that the associations between chemicals and adverse pregnancy outcomes are stronger among those who also experience non-chemical stressors. However, these studies have largely examined these associations using single pollutant models stratified by one stressor at a time.27 This may underestimate health effects, as individuals, particularly AAs, are often exposed to numerous psychosocial stressors simultaneously.

In the current study, we adapted quantile g-computation and Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR),28–30 two statistical techniques which allow us to test for additive and synergistic effects. We estimated the joint effects of four PFAS and four psychosocial stressors on gestational age and birthweight for gestational age z-scores, a proxy for fetal growth, in a cohort of AAs in Atlanta, Georgia between 2016 and 2020. We hypothesized that the cumulative effects of PFAS and psychosocial stressors together on gestational age at delivery and birthweight z-scores would be greater in magnitude than the effect of individual PFAS or psychosocial stressors alone. Based on the literature to date, we predict supraadditive rather than subadditive effect of chemicals and stress when multiple measures are included in the same model.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

Participants included in the present analysis were a subset of those enrolled in the Atlanta African American Maternal-Child Cohort (ATL AA), an ongoing prospective birth cohort. The subset included participants for whom a first trimester serum sample and questionnaire measures were available. Information about recruitment, retention, and data collection methods are described in detail elsewhere.31,32 Briefly, pregnant women are recruited during early pregnancy (between 8–14 weeks gestation) from two hospitals in metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia. Participants recruited from Emory Healthcare are generally higher socioeconomic status, while those recruited from Grady Health Systems are more socioeconomically diverse. Individuals were eligible for inclusion if they self-identified as female and being AA (Black or African American race), were born in the United States, not pregnant with multiples, fluent in English, and had no diagnosed chronic medical conditions. All participants provided written, informed consent prior to participating. The Institutional Review Board at Emory University approved the ATL AA study (approval reference number 68441).

2.2. Analysis of Per- and Poly-fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

Serum samples were obtained between 8–14 weeks gestation and were stored at −80°C prior to analysis for PFAS. Samples were analyzed at the Children’s Health Exposure Analysis Resource (CHEAR) and Human Health Exposure Analysis Resource (HHEAR) laboratories, including Wadsworth Center/New York University Laboratory Hub (Wadsworth/NYU) and the Laboratory of Exposure Assessment and Development for Environmental Research (LEADER) at Emory University. Laboratories in CHEAR and HHEAR have participated in activities to produce harmonized measurements among them.33 PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS were analyzed in all samples (N=523). A subset of samples (N=435 out of 523) were additionally analyzed the Wadsworth Center for perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS), perfluorooctane sulfonamide (PFOSA), N-methyl perfluorooctane sulfonamido acetic acid (NMeFOSAA), N-ethyl perfluorooctane sulfonamido acetic acid (NEtFOSAA), perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), PFDA, perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA) and perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDoDA).21,34 Only a subset was analyzed for these additional PFAS due to budget restrictions. The details of analytical methods used in both labs have been described in detail elsewhere.21,35 Briefly, each serum sample was spiked with internal standards, treated by solid phase extraction, and quantified by liquid chromatography interfaced with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Quantification of PFAS was performed using isotope dilution calibration. Bench and blind quality control samples and blanks were analyzed alongside unknown samples. Both laboratories participate in and are certified by the German External Quality Assessment Scheme twice annually for serum PFAS quantification and laboratory measurements have been cross-validated between the two labs conducting PFAS measurements (the Pearson correlation coefficients ranged from 0.88 to 0.93, and the relative percent differences ranged from 0.12 to 20.2% with a median of 4.8% in the 11 overlapping samples).21

We focused the present analysis on those PFAS with >80% detection, which included PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS.21 For values below the limit of detection (LOD), the concentration was replaced with.36 All PFAS concentrations were right skewed and natural log transformed for subsequent analysis.

2.3. Psychosocial Stress

We included four self-report measures of psychosocial stress: perceived stress, depression, anxiety, and gendered racial stress. All psychosocial stressors were assessed using validated questionnaires that were administered between 8–14 weeks gestation and are widely used during pregnancy.37–41 Responses to individual questions were reverse coded so that higher scores on each scale correspond to higher stress levels. All psychosocial stressors were treated as continuous measures and were normally distributed, thus no transformations were applied.

Perceived stress was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)-14.37,38 The PSS-14 included 14 questions that assess the degree to which a participant perceived their life as uncontrollable, unpredictable, or overloading. Scores on the PSS-14 ranged from 0 to 45.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used to quantify depressive symptoms.39 The EPDS is a 10-question screening tool designed to assess depression in perinatal care. Scores on the EPDS ranged from 0 to 25.

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI),40 which consists of 40 questions, 20 of which measure current feelings of anxiety and were used in this study. STAI scores ranged from 6 to 79.

Experiences of gendered racial stress were assessed using the 39-item Jackson-Hogue-Phillips-Reduced Common measure of contextualized stress,41 which assesses specific exposure to chronic racial and gendered stress among Black women and is comprised of subscales: racism, burden, coping, personal history, and work stress.42 Scores ranged from 45 to 159.

2.4. Birth Outcomes

Gestational age at delivery (in weeks) was abstracted from the medical record and was determined using the best obstetrical estimate per American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) guidelines, which is based on the date of delivery in relation to the estimated date of confinement.43 Given enrollment criteria, all participants in this study had the estimated date of confinement established in early pregnancy (enrollment visit between 8–14 weeks) by certain last menstrual period and/or first trimester ultrasound. In all cases, birthweight in grams was obtained from the first weight measured in the delivery room by the delivery room nurse attendant. Given that infant birthweight can be confounded by gestational age, we calculated birthweight for gestational age z-scores as an indicator for fetal growth. Birthweight for gestational age z-scores were sex-specific and were estimated using a US population-based reference for singleton births.44

2.5. Covariates

Marital status (categorized as married/partnered and co-habiting, single/partnered and not cohabiting), maternal level of education (categorized as less than high school, high school diploma, bachelor’s degree, graduate degree), type of health insurance during pregnancy (private, public), and number of members in the household were obtained via a standardized interview questionnaire that was administered at enrollment. An income to poverty ratio was calculated by using a combination of the number of members in the household and self-reported annual household income. Parity, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, and tobacco and marijuana in the month prior to pregnancy were abstracted from the medical record. Maternal body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) was calculated using weight and height measurements obtained during the first clinical visit between 8–14 weeks’ gestation.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Frequencies, counts, means and standard deviations (SDs) were used to examine distribution of demographics in our analytic sample. The distribution of PFAS was examined using geometric means, geometric SDs, and percentiles. Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) were used to estimate correlations between PFAS, psychosocial stressors, and gestational age and birthweight z-scores.

Loess curves were used to examine bivariate associations and linearity between PFAS, psychosocial stressors and gestational age and birthweight z-scores. Unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models were used to examine associations between individual PFAS and psychosocial stressors, with gestational age and birthweight z-scores. As a sensitivity analysis, we additionally included term birthweight (birthweight among those who delivered ≥37 weeks gestation) as an outcome in linear regression models. In these models, all PFAS and psychosocial stressors were standardized at a one-half interquartile range (IQR) increase to maximize comparisons with mixture models. Covariates retained in adjusted models were determined via a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG; Figure S1) and included maternal age (continuous), parity (0, 1 or more prior births), and any self-reported alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use (any alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana use versus none). Education (<high school, high school, college degree, graduate degree) was included as an indicator of socioeconomic status. Our DAG was informed via a literature review and associations between exposures and outcomes in our study population.21

2.6.1. Mixtures Analysis

In our first approach, we used quantile g-computation to examine joint effects of PFAS and psychosocial stressors on birth outcomes. Under the assumption of linearity, quantile g-computation estimates the effect of simultaneously increasing all exposures in the mixture by one quartile using a parametric, generalized linear model-based implementation of g-computation.28 In quantile g-computation, all exposures in the mixture (PFAS and psychosocial stressors) are recoded based on quantile cut-points which are then included in a model for the outcome. This allows each exposure in the mixture to be given a positive or negative weight, based on the direction of independent effect. Positive and negative weights sum to 1 and are interpreted as the proportion of the partial effect in the positive or negative direction due to a single exposure. As a sensitivity analysis, we altered the number of quartiles, ranging from 2 to 20, to assess whether a different numbers of exposure categories would capture different effects. As a second sensitivity analysis, we applied a novel extension of quantile g-computation to examine effect modification of the joint association between the PFAS mixture and birth outcomes by individual psychosocial stressors.45 In these models, the linear combination is made from exposure*effect modifier interaction terms. High levels of depression and anxiety were defined as scores ≥10 and 39 based on pre-defined cut points, respectively.39,46 High levels of perceived stress and gendered racial stress were defined as values above the median. Lastly, we utilized quantile g-computation to examine the effect of a PFAS mixture, adjusting for psychosocial stressors as covariates, as well as the effect of a psychosocial stress mixture, adjusting for PFAS as covariates.

As a second approach to explore non-linearity of exposures and potential interactions, we utilized Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) with component-wide variable selection (10,000 iterations).29,30 BKMR estimates a nonparametric high-dimensional exposure-response function using kernel machine regression. In BKMR models, all PFAS and psychosocial stressors were standardized to have a mean of 0 and SD of 1. The overall effect of the mixture was evaluated by comparing the expected difference in birth outcomes when exposures in the mixture were set at the 25th and 75th percentile, relative to when they were all fixed at their 50th percentile. Next, we assessed linearity by examining individual univariate exposure-response functions. To assess the interactions between PFAS and psychosocial stress exposures, we estimated bivariate exposure-response functions, which indicate evidence of interaction if the effect of one exposure differs across levels of another (i.e., the lines are not overlapping and are not parallel). Similar to quantile g-computation, the relative importance for each PFAS and psychosocial stressor was based on posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs), which identify the relative importance of individual exposure variables to the overall mixture effect.47 A traditional threshold of importance is 0.5.48

Mixture analyses were run on complete cases (N=348) and birthweight z-scores and gestational age were treated as separate outcomes in individual models. Covariates retained in mixture models were the same as those retained in linear regression. All statistical analyses were conducted using R Version 4.1.1.

3. Results

There were 523 participants for whom serum levels of PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS were available. Of this group, 348 had complete information on maternal age, education, parity, and any alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use and were included in mixture models. In our analytic sample (N=348), the mean maternal age at enrollment was 26 years (SD= 5.2). Approximately half (47%) of participants were married or living with a partner and 40% had a high school education and 29% had a college degree. Of the participants who delivered at Grady, 98% had public health insurance. The mean gestational age at delivery was 38 weeks (SD= 2.5) and the mean birthweight was 3,054 grams (SD= 627.7). The mean scores on the perceived stress, depression, anxiety, and gendered racial stress scales in our analytic sample were 24 (SD= 7.6), 7.2 (SD= 5.4), 34 (SD= 12), and 97 (SD= 20), respectively (Table 1). The distribution of demographics in our analytic sample was similar to the larger study population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of demographics and psychosocial stressors in the Atlanta African American Maternal-Child study population, 2016–2020.

| Overall (N=523)1 | Analytic Sample for Mixtures (N=348)2 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| N (%) or Mean (SD) | N (%) or Mean (SD) | |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Maternal Age (years) | 25 (4.9) | 26 (5.2) |

|

| ||

| Maternal Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 29 (7.8) | 29 (7.9) |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Living Together | 249 (48 %) | 165 (47 %) |

| Single | 274 (52 %) | 183 (53 %) |

|

| ||

| Maternal Education | ||

| <High School | 83 (16 %) | 53 (15 %) |

| High School | 202 (39 %) | 140 (40 %) |

| College Degree | 152 (29 %) | 100 (29 %) |

| Graduate Degree | 86 (16 %) | 55 (16 %) |

|

| ||

| Income to Poverty Ratio | ||

| <100% | 227 (43 %) | 154 (44 %) |

| 100–150% | 119 (23 %) | 83 (24 %) |

| 150–300% | 112 (21 %) | 74 (21 %) |

| >300% | 65 (12 %) | 37 (11 %) |

|

| ||

| Tobacco Use | ||

| No | 434 (84 %) | 281 (81 %) |

| Yes | 89 (17 %) | 67 (19 %) |

|

| ||

| Alcohol Use | ||

| No | 460 (88 %) | 303 (87 %) |

| Yes | 63 (12 %) | 45 (13 %) |

|

| ||

| Marijuana Use | ||

| No | 348 (67 %) | 218 (63 %) |

| Yes | 175 (33 %) | 130 (37 %) |

|

| ||

| Parity (at prenatal enrollment) | ||

| 0 | 244 (47 %) | 152 (44 %) |

| 1+ | 279 (53 %) | 196 (56 %) |

|

| ||

| Health Insurance | ||

| Public | 413 (79 %) | 285 (82 %) |

| Private | 110 (21 %) | 63 (18 %) |

|

| ||

| Delivery Hospital | ||

| Emory | 209 (40 %) | 124 (36 %) |

| Grady | 314 (60 %) | 224 (64 %) |

|

| ||

| Infant Sex | ||

| Male | 252 (48 %) | 177 (51 %) |

| Female | 264 (50 %) | 171 (49 %) |

|

| ||

| Gestational Age at Delivery (weeks) | 38 (2.6) | 38 (2.5) |

| Missing | 9 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||

| Birthweight (grams) | 3026 (637.6) | 3054 (627.7) |

| Missing | 10 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||

| Birthweight for Gestational Age Z-score | −0.47 (1.1) | −0.39 (1.1) |

|

| ||

| Missing | 26 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||

| Psychosocial Stressors | ||

|

| ||

| Perceived Stress | 24 (7.7) | 24 (7.6) |

| Missing | 27 (5.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||

| Anxiety Symptoms | 34 (12) | 34 (12) |

| Missing | 156 (29.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||

| Depression Symptoms | 7.1 (5.4) | 7.2 (5.4) |

| Missing | 40 (7.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||

| Gendered Racial Stress | 96 (21) | 97(20) |

| Missing | 33 (6.3) | 0 (0.0%) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation.

Indicates all participants in the Atlanta African American Maternal-Child study population for which PFAS were available (N=523).

Indicates all participants retained in mixture models (N=348).

PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS were detected in the sera of >95% of participants (Table 2). PFAS levels in our analytic sample were slightly lower than what was observed in the overall study population (Table 2). In our analytic sample, the geometric mean was highest for PFOS (geometric mean= 1.62 ng/mL [geometric SD= 2.55 ng/mL]), followed by PFHxS (geometric mean= 1.12 ng/mL [geometric SD= 2.15 ng/mL]). All PFAS were moderately correlated with one another (ρ ranging from 0.28 to 0.65). Psychosocial stressors were similarly correlated with one another (ρ ranging from 0.45 to 0.65) and were weakly correlated with PFAS (Figure S2).

Table 2.

Distribution of first trimester serum levels of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (ng/mL) with >80% detection in the Atlanta African American Maternal-Child study population, 2016–2020.

| Percentiles | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| %Above LOD | Geometric Mean (Geometric SD) |

5 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 95 | |

| PFNA | |||||||

| 1 Overall | 96.75 | 0.26 (2.35) | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.3 | 0.47 | 0.81 |

| 2 Analytic Sample for Mixtures | 97.41 | 0.24 (2.35) | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.75 |

|

| |||||||

| PFOA | |||||||

| 1 Overall | 97.32 | 0.62 (2.36) | 0.11 | 0.45 | 0.7 | 1.06 | 1.69 |

| 2 Analytic Sample for Mixtures | 98.28 | 0.6 (2.23) | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 1.64 |

|

| |||||||

| PFHxS | |||||||

| 1 Overall | 97.51 | 1.16 (2.06) | 0.3 | 0.81 | 1.24 | 1.75 | 3.61 |

| 2 Analytic Sample for Mixtures | 97.41 | 1.12 (2.15) | 0.29 | 0.73 | 1.19 | 1.79 | 3.62 |

|

| |||||||

| PFOS | |||||||

| 1 Overall | 97.9 | 1.89 (2.5) | 0.53 | 1.38 | 2.12 | 3.23 | 5.44 |

| 2 Analytic Sample for Mixtures | 98.28 | 1.62 (2.55) | 0.45 | 1.16 | 1.82 | 2.83 | 4.71 |

Abbreviations: LOD, limit of detection; SD, standard deviation.

Indicates all participants in the Atlanta African American Maternal-Child study population for which PFAS were available (N=523).

Indicates all participants retained in mixture models (N=348).

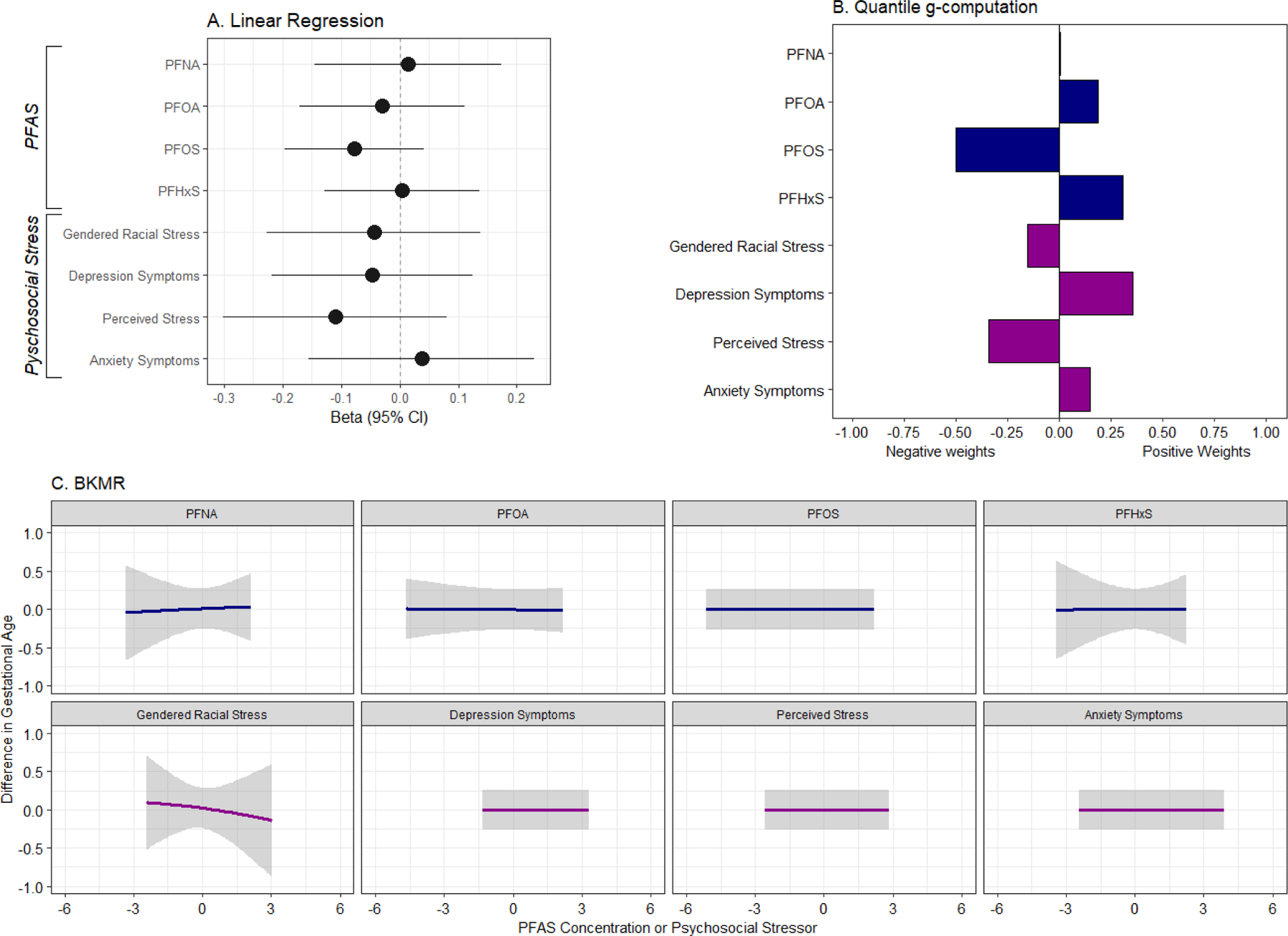

In our analytic sample for mixtures, a one half IQR increase in all PFAS and psychosocial stressors, was associated with modestly lower birthweight z-scores. The magnitude of association was greatest for PFNA (β= −0.05, 95% CI= −0.13, 0.01) and depression (β= −0.07, 95% CI = −0.14, 0.01) (Figure 1A; Table S1). Similarly, a one half IQR increase in PFOS (β= −0.08, 95% CI= −0.20, 0.04) and perceived stress (β= −0.11, 95% CI= −0.30, 0.08) was associated with shorter gestational age (Figure 2A; Table S1). Associations were similar to what was observed in the overall study population and when term birthweight was the outcome of interest (Table S1).

Figure 1.

(A) Change in birthweight for gestational age z-scores corresponding to a one-half interquartile range increase in individual PFAS and psychosocial stressors; (B) weights representing the proportion of the positive and negative effect on birthweight z-scores in relation to a mixture of PFAS and psychosocial stressors, estimated using quantile g-computation (N=348); and (C) univariate exposure-response functions indicating change in birthweight-scores resulting from individual PFAS and psychosocial stressors while fixing remaining exposures in the mixture at their 50th percentiles, estimated using BKMR (N=348).

Note: All models were adjusted for maternal education, maternal age, parity, and any alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. (1A) Sample sizes for linear regression models are provided in Table S1. (1B) For quantile g-computation, negative and positive weights each sum to 1 and correspond to the effect size relative to other effects in the same direction and should not be directly compared. Positive weights indicate mixture components that were associated with an increase in birthweight z-scores and negative weights correspond to mixture components associated with a reduction in birthweight z-scores. (1C) In BKMR models, all PFAS and psychosocial stressors were standardized to have a mean of 0 and SD of 1.

Figure 2.

(A) Change in gestational age at delivery (weeks) corresponding to a one-half interquartile range increase in individual PFAS and psychosocial stressors; (B) weights representing the proportion of the positive and negative effect on gestational age in relation to a mixture of PFAS and psychosocial stressors, estimated using quantile g-computation; and (C) univariate exposure-response functions indicating change in gestational age resulting from individual PFAS and psychosocial stressors while fixing remaining exposures in the mixture at their 50th percentiles, estimated using BKMR (N=348).

Note: All models were adjusted for maternal education, maternal age, parity, and any alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. (2A) Sample sizes for linear regression models are provided in Table S1. (2B) For quantile g-computation, negative and positive weights each sum to 1 and correspond to the effect size relative to other effects in the same direction and should not be directly compared. Positive weights indicate mixture components that were associated with an increase in gestational age and negative weights correspond to mixture components associated with a reduction in gestational age. (2C) In BKMR models, all PFAS and psychosocial stressors were standardized to have a mean of 0 and SD of 1.

Using quantile g-computation, increasing all PFAS, perceived stress, depression, gendered racial stress, and anxiety by one quartile was associated with a reduction birthweight z-scores (mean change per quartile increase = −0.24, 95% CI= −0.43, −0.06) (Table S2). PFOA, gendered racial stress, depression and anxiety were assigned the largest negative weights, indicating that they were negatively associated with birthweight z-scores (Figure 1B; Table S3). Associations between the PFAS and stress mixture and gestational age were similar in magnitude but were less precise (mean change per quartile increase = −0.25, 95% CI = −0.68, 0.18), and PFOS and perceived stress were assigned the largest negative weights in the model which included gestational age as the outcome (Figure 2B; Table S3). The effect of the PFAS and psychosocial stress mixture was greater in magnitude for both gestational age at delivery and birthweight z-scores, relative to the mixture of PFAS alone and to the mixture of psychosocial stressors alone (Table S2). Altering the number of quantiles in the mixture models did not noticeably change effect estimates (data not shown). We observed evidence of interaction between the PFAS mixture and birthweight z-scores by gendered racial stress, where increasing the PFAS mixture by one quartile was associated with reduced birthweight z-scores only among those with gendered racial stress values above the median (mean change per quartile increase= −0.24, 95% CI= −0.43, −0.04; p-interaction= 0.1) (Table S4). Among those with value of gendered racial stress below the median, the PFAS mixture was not associated with birthweight z-scores (mean change per quartile increase= 0.00, 95% CI= −0.20, 0.19). Significant interaction between the PFAS mixture and perceived stress was also observed, where an increase in the PFAS mixture was associated with a reduction in gestational age only among those who experienced low perceived stress (mean change per quartile increase= −0.42, 95% CI= −0.84, 0.00; p-interaction= 0.05).

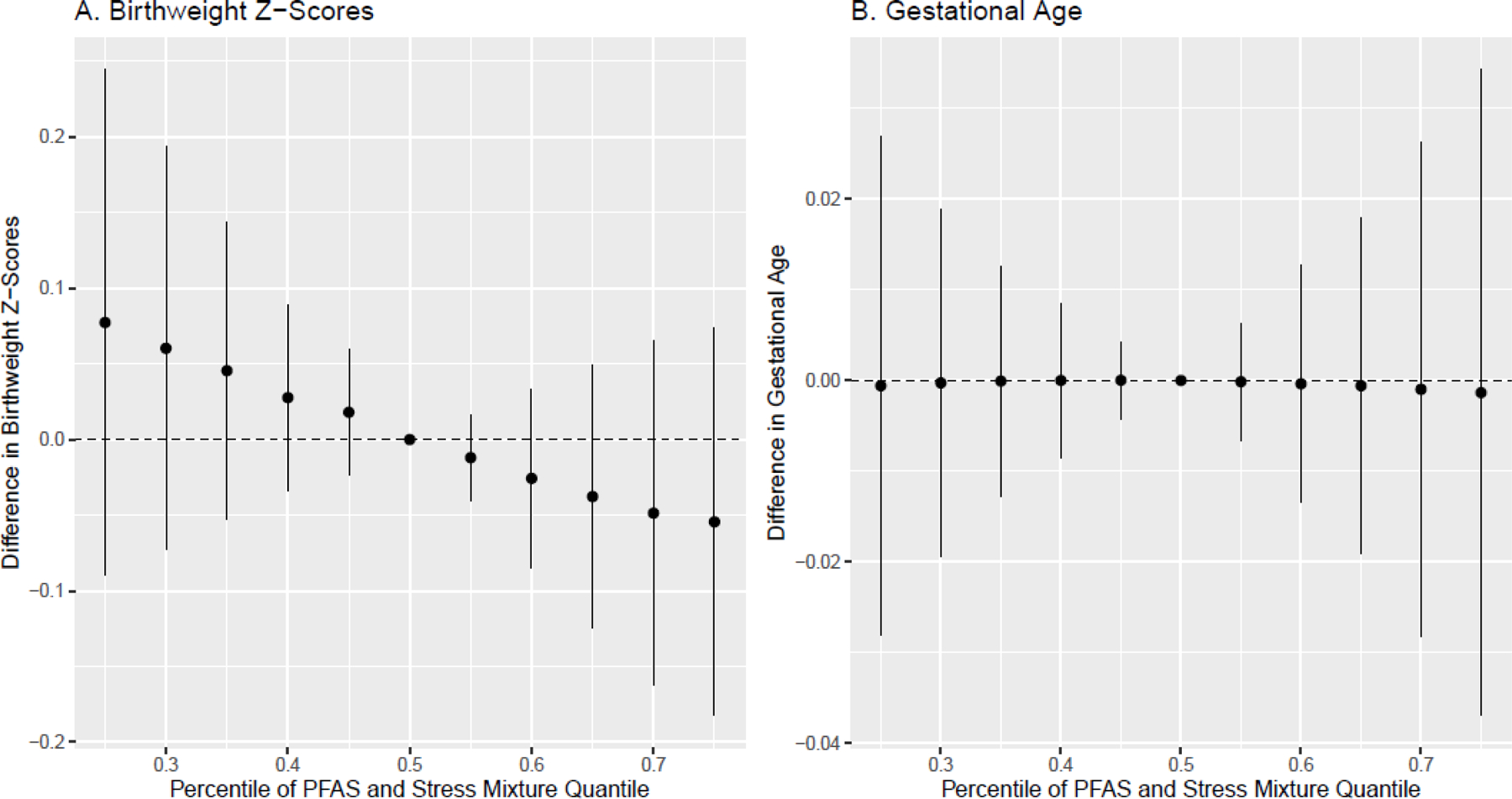

In BKMR univariate exposure-response analysis, we observed that PFNA, PFOA, and depression were associated with a modest reduction in birthweight z-scores, while the relationship with anxiety was somewhat non-linear (Figure 1C). When gestational age was the outcome, only gendered racial stress had a negative effect (Figure 2C). When examining the overall effect of the mixture, we observed a negative trend, indicating that increasing all exposures in the mixture was associated with a non-significant reduction in birthweight z-scores (Figure 3A). The overall effect of the mixture was not associated with gestational age (Figure 3B). When birthweight z-scores was the outcome of interest, we observed potential evidence of interaction between anxiety and depression, and anxiety and PFHxS (Figure S3). No evidence of interaction was observed when gestational age was the outcome (Figure S4). BKMR did not identify any PFAS or psychosocial stressors as being “important” predictors of gestational age or birthweight z-scores, as all PIP values were <0.5 (Table S5).

Figure 3.

Cumulative effect (estimates and 95% credible intervals) of the PFAS and psychosocial stressor mixture on birthweight for gestational age z-scores and gestational age at delivery (in weeks), estimated using BKMR (N=348).

Note: Models are adjusted for maternal education, maternal age, parity, and any alcohol, tobacco and marijuana use. All PFAS and psychosocial stressors are standardized to have a mean of 0 and SD of 1.

4. Discussion

In a cohort of AA pregnant women in Atlanta, Georgia, we found that simultaneously experiencing exposure to multiple PFAS and psychosocial stressors was associated with reduced birthweight for gestational age z-scores, a proxy for fetal growth. There was no apparent association between the PFAS and stress mixture with gestational age at delivery. Our analysis utilized two types of advanced statistical methods developed to assess chemical exposure mixtures. Both methods produced consistent results and indicated that the joint effects of the PFAS and stress mixture were greater in magnitude than what we observed in our single pollutant analyses. Our study provides novel information about adverse health effects associated with cumulative exposures among AAs, which is critically important as this population is routinely exposed to the multiple psychosocial stressors and experience a high burden of environmental hazards and increased risk of adverse birth outcomes.

Our results contribute to a growing body of literature indicating that non-chemical stressors may amplify the harmful effects of chemicals. Numerous studies have examined joint effects of chemical and non-chemical stressors on pregnancy outcomes, largely using single pollutant models stratified by binary indicators of a single stressor.23,49–52 Few studies have examined these exposures together as a mixture. Findings from our study are most comparable to recent by work by members of our team who examined joint effects of PFAS, perceived stress, and depression in two pregnancy cohorts in San Francisco, California and central Illinois.53 In that study, increasing PFAS, perceived stress, and depression simultaneously was associated with a non-significant decrease in fetal growth. The effect sizes observed in the present study were greater in magnitude and may reflect differences in study populations, as the present study included only AAs while the other two study populations included largely White participants. The current study also included anxiety and racial gendered stress as additional psychosocial stress exposures in mixture models, which we found to have a negative effect on fetal growth. Our findings are also supported by prior studies examining mixtures of PFAS, alone or in combination with other chemical classes, in relation to birth outcomes.54–57 Using BKMR and Weighted Quantile Sum regression, prior work shows that PFAS are associated with a reduction in birthweight.54,55 Other studies have utilized different mixture methods to assess the cumulative effects of chemical and non-chemical stressors during pregnancy.56,58,59 For example, in the New Bedford Cohort, a joint effect of organochlorines and metals, sociodemographic, parental and home characteristics on risk-taking behaviors in adolescence was observed with a semi-parametric additive mixture model.56

We observed no association between the PFAS and stress mixture on gestational age at delivery. However, in our sensitivity analysis using quantile g-computation to examine effect modification, we observed that the increasing PFAS concentrations were associated with a reduction in gestational age only among those who reported low perceived stress. It could be that those who report high perceived stress also experience other stressors and risk factors that ‘outweigh’ PFAS in terms of affecting gestational age. This was in contrast to our hypothesis and may also be reflective of non-linear associations, as we observed some evidence that higher levels of perceived stress, gendered racial stress, and depression symptoms were associated with a slight, non-significant, reduction in gestational age in linear regression models. Consistent with these findings, prior studies found that perceived stress, depression, and experiences of racism were associated with increased odds of preterm birth and shorter gestational duration.8,9,11,60 A meta-analysis that included studies published between 2010 and 2020 found that AAs with depression were twice as likely to experience a preterm or low birthweight birth relative to Whites, which supports our findings from linear regression.10 While not observed in our study, symptoms of anxiety have been identified as significant contributors to reduced gestational age in prior work.9

Our single pollutant and mixture models identified PFOS as the PFAS that was most strongly associated with a reduction in gestational age at delivery. This may be indicative of a dose-response, as PFOS was detected at the highest concentrations relative to other PFAS in our study population, and is the most frequently detected PFAS in biological samples. Levels of PFAS and psychosocial stressors in our study population are similar to levels in other studies. Compared to PFAS levels in NHANES matched on age, sex, and race, levels of PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA were similar, while levels of PFHxS were higher.21 Sociodemographic characteristics associated with higher PFAS levels in our study included having more than a high school education and frequent use of cosmetics, while increasing parity and tobacco use were associated with lower PFAS levels.21 Psychosocial stress levels in our study were higher than what has been observed in largely White populations and were consistent with stress levels observed in other primary AA study populations.61,62

PFAS and psychosocial stress may be leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes, including birthweight z-scores, through multiple mechanisms. Previously in this study population, we observed that perturbations of biological pathways involved in amino acid, lipid and fatty acid, bile acid, and androgenic hormone metabolism were associated with both PFAS exposures and reduced birthweight z-scores, our marker of fetal growth.34 Other pathways could be through perturbations in biological pathways connected with inflammation, oxidative stress, and endocrine disruption.63 These processes are also sensitive to the psychosocial stressors examined here (perceived stress, depression, anxiety and racial stress),64–66 suggesting that they may amplify the effects of PFAS.

Our study is not without limitations. Misclassification of psychosocial stress may have occurred, as individuals may respond to the questionnaires differently and structured clinical interviews were not performed. Nonetheless, questionnaires used to assess psychosocial stress in our study have been validated and have demonstrated good reliability across study populations.37–41 Our analysis also focused on four PFAS that were well-detected and emerging or alternative PFAS with lower detection rates and/or shorter half-lives may also contribute to the observed associations. Despite these limitations, our study has many strengths. The pregnancy outcomes under study were ascertained by the abstraction of pregnancy, labor and delivery, and neonatal records by medical personnel among women who presented for clinical prenatal care between 8–14 weeks of gestation, minimizing the chance of misclassification. While we cannot rule out the possibility that outcome misclassification may have occurred, we expect an outcome misclassification to be minimal, as our birth outcomes were defined using current definitions recommended by ACOG. Further. all participants in the study had early pregnancy dating, based on their enrollment at 8–14 weeks of gestation, further contributing to the accuracy of gestational age at birth ascertainment. We incorporated psychosocial stressors into our mixture analysis, allowing us to better estimate real life exposures. However, PFAS and psychosocial stressors were not strongly correlated in our study population, and thus our primary mixture models of PFAS and psychosocial stress together should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, incorporating both chemical and non-chemical stressors in mixture models is critically important for future studies conducted in populations, such as AAs, that experience high levels of both chemical and non-chemical stressors and increased risk of adverse birth outcomes. Additionally, AAs are largely excluded from environmental epidemiologic studies and our results provide important information that may help explain persistent health disparities and the inexplicably high rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes in this population.

4.1. Conclusions

When examined together as an exposure mixture, PFAS, perceived stress, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and gendered racial stress were associated with reduced fetal growth. The cumulative effects of these exposures were greater in magnitude than the effect of any single exposure. Our results provide important information on risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes among AAs, a population who consistently experiences high rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes, and is disproportionally exposed to psychosocial stress and environmental hazards. Future studies examining the effect of multiple exposures on pregnancy outcomes should consider that social factors can enhance the effects of chemicals and may shape chemical exposure patterns.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) research grants [R01NR014800, R01MD009064, R24ES029490, R01MD009746], NIH Center Grants [P50ES02607, P30ES019776, UG3/UH3OD023318, U2CES026560, U2CES026542, U2COD023375], and Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) center grant [83615301]. We would like to thank the study participants who participated in the ATL AA cohort study, and the clinical health care providers and staff at the prenatal recruiting sites for helping with data and sample collection and logistics and sample chemical analyses in the laboratory, especially Nathan Mutic, Priya D’Souza, Estefani Ignacio Gallegos, Nikolay Patrushev, Kristi Maxwell Logue, Castalia Thorne, Shirleta Reid, and Cassandra Hall.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sunderland EM, Hu XC, Dassuncao C, Tokranov AK, Wagner CC, Allen JG. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2019;29(2):131–147. doi: 10.1038/s41370-018-0094-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999–2000. Environ Health Perspect 2007;115(11):1596–1602. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall SM, Zhang S, Hoffman K, Miranda ML, Stapleton HM. Concentrations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in human placental tissues and associations with birth outcomes. Chemosphere 2022;295:133873. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.133873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varsi K, Huber S, Averina M, Brox J, Bjørke-Monsen AL. Quantitation of linear and branched perfluoroalkane sulfonic acids (PFSAs) in women and infants during pregnancy and lactation. Environment International 2022;160:107065. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.107065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panagopoulos Abrahamsson D, Wang A, Jiang T, et al. A Comprehensive Non-targeted Analysis Study of the Prenatal Exposome. Environ Sci Technol 2021;55(15):10542–10557. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c01010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao X, Ni W, Zhu S, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances exposure during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Research 2021;201:111632. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erinc A, Davis MB, Padmanabhan V, Langen E, Goodrich JM. Considering environmental exposures to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as risk factors for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Environmental Research 2021;197:111113. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nutor JJ, Slaughter-Acey JC, Giurgescu C, Misra DP. Symptoms of Depression and Preterm Birth Among Black Women. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing 2018;43(5). https://journals.lww.com/mcnjournal/Fulltext/2018/09000/Symptoms_of_Depression_and_Preterm_Birth_Among.3.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard M, Wittkowski A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women and Birth 2015;28(3):179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simonovich SD, Nidey NL, Gavin AR, et al. Meta-Analysis Of Antenatal Depression And Adverse Birth Outcomes In US Populations, 2010–20. Health Affairs 2021;40(10):1560–1565. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alhusen JL, Bower KM, Epstein E, Sharps P. Racial Discrimination and Adverse Birth Outcomes: An Integrative Review. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 2016;61(6):707–720. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal Stress and Preterm Birth. American Journal of Epidemiology 2003;157(1):14–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eick SM, Meeker JD, Swartzendruber A, et al. Relationships between psychosocial factors during pregnancy and preterm birth in Puerto Rico. PLoS One 2020;15(1):e0227976–e0227976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bower KM, Thorpe RJ, LaVeist TA. Perceived Racial Discrimination and Mental Health in Low-Income, Urban-Dwelling Whites. Int J Health Serv 2013;43(2):267–280. doi: 10.2190/HS.43.2.e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forde AT, Sims M, Muntner P, et al. Discrimination and Hypertension Risk Among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension 2020;76(3):715–723. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown LL, Mitchell UA, Ailshire JA. Disentangling the Stress Process: Race/Ethnic Differences in the Exposure and Appraisal of Chronic Stressors Among Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 2020;75(3):650–660. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braveman P, Dominguez TP, Burke W, et al. Explaining the Black-White Disparity in Preterm Birth: A Consensus Statement From a Multi-Disciplinary Scientific Work Group Convened by the March of Dimes. Frontiers in Reproductive Health 2021;3. 10.3389/frph.2021.684207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morello-Frosch R, Shenassa ED. The environmental “riskscape” and social inequality: implications for explaining maternal and child health disparities. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114(8):1150–1153. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zota AR, Shamasunder B. The environmental injustice of beauty: framing chemical exposures from beauty products as a health disparities concern. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2017;217(4):418.e1–418.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boronow KE, Brody JG, Schaider LA, Peaslee GF, Havas L, Cohn BA. Serum concentrations of PFASs and exposure-related behaviors in African American and non-Hispanic white women. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 2019;29(2):206–217. doi: 10.1038/s41370-018-0109-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang CJ, Ryan PB, Smarr MM, et al. Serum per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) concentrations and predictors of exposure among pregnant African American women in the Atlanta area, Georgia. Environmental Research 2021;198:110445. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eick SM, Goin DE, Cushing L, et al. Joint effects of prenatal exposure to per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances and psychosocial stressors on corticotropin-releasing hormone during pregnancy. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology Published online April 6, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41370-021-00322-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hahn J, Gold DR, Coull BA, et al. Air Pollution, Neonatal Immune Responses, and Potential Joint Effects of Maternal Depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021;18(10). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson KK, Rosen EM, Barrett ES, et al. Joint impact of phthalate exposure and stressful life events in pregnancy on preterm birth. Environment International 2019;133:105254. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aker A, McConnell RER, Loch-Caruso R, et al. Interactions between chemicals and non-chemical stressors: The modifying effect of life events on the association between triclocarban, phenols and parabens with gestational length in a Puerto Rican cohort. Sci Total Environ 2020;708:134719. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashrap P, Aker A, Watkins DJ, et al. Psychosocial status modifies the effect of maternal blood metal and metalloid concentrations on birth outcomes. Environment International 2021;149:106418. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H, Wang A, Morello-Frosch R, et al. Cumulative Risk and Impact Modeling on Environmental Chemical and Social Stressors. Current Environmental Health Reports 2018;5(1):88–99. doi: 10.1007/s40572-018-0180-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keil AP, Buckley JP, O’Brien KM, Ferguson KK, Zhao S, White AJ. A Quantile-Based g-Computation Approach to Addressing the Effects of Exposure Mixtures. Environ Health Perspect 2020;128(4):47004. doi: 10.1289/ehp5838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bobb JF, Claus Henn B, Valeri L, Coull BA. Statistical software for analyzing the health effects of multiple concurrent exposures via Bayesian kernel machine regression. Environmental Health 2018;17(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12940-018-0413-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bobb JF, Valeri L, Claus Henn B, et al. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics 2015;16(3):493–508. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxu058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corwin EJ, Hogue CJ, Pearce B, et al. Protocol for the Emory University African American Vaginal, Oral, and Gut Microbiome in Pregnancy Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2017;17(1):161. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1357-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennan PA, Dunlop AL, Smith AK, Kramer M, Mulle J, Corwin EJ. Protocol for the Emory University African American maternal stress and infant gut microbiome cohort study. BMC Pediatrics 2019;19(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1630-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balshaw DM, Collman GW, Gray KA, Thompson CL. The Children’s Health Exposure Analysis Resource: enabling research into the environmental influences on children’s health outcomes. Curr Opin Pediatr 2017;29(3):385–389. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang CJ, Barr DB, Ryan PB, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) exposure, maternal metabolomic perturbation, and fetal growth in African American women: A meet-in-the-middle approach. Environment International 2022;158:106964. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honda M, Robinson M, Kannan K. A rapid method for the analysis of perfluorinated alkyl substances in serum by hybrid solid-phase extraction. Environ Chem 2018;15(2):92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hornung RW, Reed LD. Estimation of Average Concentration in the Presence of Nondetectable Values. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 1990;5(1):46–51. doi: 10.1080/1047322X.1990.10389587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen S Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: The Social Psychology of Health. The Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology Sage Publications, Inc; 1988:31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spielberger CD. Manual for the state-trait anxiety, inventory. Consulting Psychologist Published online 1970.

- 41.Jackson FM, Hogue CR, Phillips MT. The development of a race and gender-specific stress measure for African-American women: Jackson, Hogue, Phillips contextualized stress measure. Ethn Dis 2005;15(4):594–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson FM, Hogue CJ, Phillips MT. Phillips, Jackson, Hogue, Phillips Contextualized Stress Measure. 2014 (Clinical Form): Technical Manual Published online 2014.

- 43.Committee Opinion No 700: Methods for Estimating the Due Date. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2017;129(5). https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2017/05000/Committee_Opinion_No_700__Methods_for_Estimating.50.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aris IM, Kleinman KP, Belfort MB, Kaimal A, Oken E. A 2017 US Reference for Singleton Birth Weight Percentiles Using Obstetric Estimates of Gestation. Pediatrics 2019;144(1):e20190076. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevens DR, Bommarito PA, Keil AP, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite mixtures in pregnancy and fetal growth: Findings from the infant development and the environment study. Environment International 2022;163:107235. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knight RG, Waal-Manning HJ, Spears GF. Some norms and reliability data for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Zung Self-Rating Depression scale. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 1983;22(4):245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1983.tb00610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barbieri Maria Maddalena, Berger James O.. Optimal predictive model selection. The Annals of Statistics 2004;32(3):870–897. doi: 10.1214/009053604000000238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cathey AL, Eaton JL, Ashrap P, et al. Individual and joint effects of phthalate metabolites on biomarkers of oxidative stress among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. Environment International 2021;154:106565. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyland C, Bradshaw P, Deardorff J, et al. Interactions of agricultural pesticide use near home during pregnancy and adverse childhood experiences on adolescent neurobehavioral development in the CHAMACOS study. Environmental Research 2022;204:111908. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Padula AM, Monk C, Brennan PA, et al. A review of maternal prenatal exposures to environmental chemicals and psychosocial stressors-implications for research on perinatal outcomes in the ECHO program. J Perinatol 2020;40(1):10–24. doi: 10.1038/s41372-019-0510-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Padula AM, Rivera-Núñez Z, Barrett ES. Combined Impacts of Prenatal Environmental Exposures and Psychosocial Stress on Offspring Health: Air Pollution and Metals. Curr Environ Health Rep 2020;7(2):89–100. doi: 10.1007/s40572-020-00273-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clougherty Jane E, Levy Jonathan I, Kubzansky Laura D, et al. Synergistic Effects of Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Exposure to Violence on Urban Asthma Etiology. Environmental Health Perspectives 2007;115(8):1140–1146. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eick SM, Enright EA, Padula AM, et al. Prenatal PFAS and psychosocial stress exposures in relation to fetal growth in two pregnancy cohorts: applying environmental mixture methods to chemical and non-chemical stressors. Environ Int 2022;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Zhuang LH, Chen A, Braun JM, et al. Effects of gestational exposures to chemical mixtures on birth weight using Bayesian factor analysis in the Health Outcome and Measures of Environment (HOME) Study. Environmental Epidemiology 2021;5(3). https://journals.lww.com/environepidem/Fulltext/2021/06000/Effects_of_gestational_exposures_to_chemical.11.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Svensson K, Tanner E, Gennings C, et al. Prenatal exposures to mixtures of endocrine disrupting chemicals and children’s weight trajectory up to age 5.5 in the SELMA study. Sci Rep 2021;11(1):11036–11036. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89846-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vieira VM, Levy JI, Fabian MP, Korrick S. Assessing the relation of chemical and non-chemical stressors with risk-taking related behavior and adaptive individual attributes among adolescents living near the New Bedford Harbor Superfund site. Environment International 2021;146:106199. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liao Q, Tang P, Song Y, et al. Association of single and multiple prefluoroalkyl substances exposure with preterm birth: Results from a Chinese birth cohort study. Chemosphere 2022;307:135741. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zilversmit Pao L, Harville EW, Wickliffe JK, Shankar A, Buekens P. The Cumulative Risk of Chemical and Nonchemical Exposures on Birth Outcomes in Healthy Women: The Fetal Growth Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16(19):3700. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamayo YOM, Téllez-Rojo MM, Trejo-Valdivia B, et al. Maternal stress modifies the effect of exposure to lead during pregnancy and 24-month old children’s neurodevelopment. Environ Int 2017;98:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bower KM, Geller RJ, Perrin NA, Alhusen J. Experiences of Racism and Preterm Birth: Findings from a Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 2004 through 2012. Women’s Health Issues 2018;28(6):495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kornfield SL, Riis VM, McCarthy C, Elovitz MA, Burris HH. Maternal perceived stress and the increased risk of preterm birth in a majority non-Hispanic Black pregnancy cohort. Journal of Perinatology Published online August 16, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41372-021-01186-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Kim DR, Sockol LE, Sammel MD, Kelly C, Moseley M, Epperson CN. Elevated risk of adverse obstetric outcomes in pregnant women with depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 2013;16(6):475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0371-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X, Barr DB, Dunlop AL, et al. Assessment of metabolic perturbations associated with exposure to phthalates among pregnant African American women. Science of The Total Environment Published online November 16, 2021:151689. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Eick SM, Barrett ES, van ‘t Erve TJ, et al. Association between prenatal psychological stress and oxidative stress during pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2018;32(4):318–326. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Venkatesh KK, Meeker JD, Cantonwine DE, McElrath TF, Ferguson KK. Association of antenatal depression with oxidative stress and impact on spontaneous preterm birth. J Perinatol 2019;39(4):554–562. doi: 10.1038/s41372-019-0317-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simons RL, Lei MK, Beach SRH, et al. Discrimination, segregation, and chronic inflammation: Testing the weathering explanation for the poor health of Black Americans. Developmental Psychology 2018;54(10):1993–2006. doi: 10.1037/dev0000511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.