Abstract

Context:

Advance care planning (ACP) intends to support person-centered medical decision-making by eliciting patient preferences. Research has not identified significant associations between ACP and goal-concordant end-of-life care, leading to justified scientific debate regarding ACP utility.

Objective:

To delineate ACP’s potential benefits and missed opportunities and identify an evidence-informed, clinically relevant path ahead for ACP in serious illness.

Methods:

We conducted a narrative review merging the best available ACP empirical data, grey literature, and emergent scholarly discourse using a snowball search of PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar (2000–2022). Findings were informed by our team’s interprofessional clinical and research expertise in serious illness care.

Results:

Early ACP practices were largely tied to mandated document completion, potentially failing to capture the holistic preferences of patients and surrogates. ACP models focused on serious illness communication rather than documentation show promising patient and clinician results. Ideally, ACP would lead to goal-concordant care even amid the unpredictability of serious illness trajectories. But ACP migh also provide a false sense of security that patients’ wishes will be honored and revisited at end-of-life. An iterative, ‘building block’ framework to integrate ACP throughout serious illness is provided alongside clinical practice, research, and policy recommendations.

Conclusions:

We advocate a balanced approach to ACP, recognizing empirical deficits while acknowledging potential benefits and ethical imperatives (e.g., fostering clinician-patient trust and shared decision-making). We support prioritizing patient/surrogate-centered outcomes with more robust measures to account for interpersonal clinician-patient variables that likely inform ACP efficacy and may better evaluate information gleaned during serious illness encounters.

Keywords: advance care planning, advance directives, communication, serious illness, palliative care, patient-centered care, goal-concordant care, end-of-life

Introduction

Opportunities to align disease-modifying treatments with a patient’s goals, values, and preferences are commonly missed in the serious illness and end of life context.1,2 These missed opportunities likely reflect a spectrum of unmet needs and care delivery gaps (e.g., insufficient patient knowledge, prognostic uncertainty, lack of communication about patient preferences in complex medical circumstances). High-quality serious illness care requires that patients have time to deliberate on the nature of their medical conditions and the many ways those conditions impact their quality of life. For instance, patients will likely need to make complex current and future decisions based on treatment options and limitations, and the risks, benefits, and likely outcomes with and without those interventions.3,4 Advance care planning (ACP) is often employed to accomplish such tasks.

ACP is an iterative process that supports patients and surrogates to: 1) consider their quality of life and care preferences in the context of their current and future decision-making capacity; 2) envision what the future might hold related to their psychosocial and functional status; 3) identify and discuss what care choices might be preferred prior to the immediacy of such decisions needing to be made in partnership with loved ones; 4) designate and discuss preferences with a surrogate to make medical decisions in case a patient cannot participate; and 5) communicate those choices with their clinicians through formal and informal methods (e.g., medical/legal documents and verbal communication, respectively).5 A key component of surrogate designation is discussion regarding how binding previously documented preferences are (e.g., surrogate decision-making leeway).6 Surrogates are fundamental to ACP and likely require additional preparation to best learn about the patient’s needs and values and to ease their decisional burden.7

ACP is complicated by the unpredictable course of many serious illnesses. This requires that clinicians know how to elicit a patient’s values beyond the biomedical aspects of clinician-patient communication, so that they can ensure treatment concordant with the patient’s goals, hopes, concerns, and available social supports, as well as the elements they deem essential to maintain a meaningful and quality life.3 Expertly elicited, discussed, and documented patient value systems are intended to foster person-centered care,8–10 particularly amid the high stakes, ethically complex nature of serious illness and end-of-life care.11 Further, this process can support situation-specific and in-the-moment decision-making as challenging medical circumstances arise.12,13 A recent scoping review on ACP interventions and outcomes affirmed the complexity of ACP and showed heterogenous trial characteristics with mixed outcomes pertaining to quality of care and health status, while also pointing to improved patient/surrogate communication and care satisfaction and a decrease in both surrogate/clinician distress.14 Nonetheless, ACP’s efficacy and evidence base have been questioned by leading palliative and serious illness care experts,15,16 and there remains disagreement about the value of ACP research and utility in clinical practice.17,18

Experts have noted that despite widespread ACP adoption, increased reimbursement for ACP encounters, and multiple payers’ use of ACP as a quality measure, comprehensive scientific data does not support the hypothesis that ACP leads to enhanced goal-concordance at the end-of-life.16 Further, they have expressed concern that continued investment in ACP is less valuable then more substantive clinical interventions and outcomes and that incentivizing ACP could lead to potentially misguided procedure-oriented, as opposed to person-oriented, practices.19 ACP proponents note the design and methodological limitations of ACP randomized controlled trials,20 the essential nature of ACP as a mechanism to understanding a patient’s acceptability of their image of life,21 and the need for standardized “whole-system strategic approaches” to ACP.22 Sudore et al. described improved ACP models that recognize the inherent complexity of ACP processes, the absence of unstandardized goal concordance measures, the disparate adoption of ACP utilization as a patient-centered outcome, and the likelihood of ACP to be nurtured through collaborations with community-based organizations.23 Humanitarian emergencies such as COVID-19 have increased the stakes surrounding ACP, requiring increased availability of clinical tools to improve shared-decision making.24

Given the breadth of predictive and associative factors related to ACP, a narrative review was warranted. We aimed to delineate ACP’s potential benefits and missed opportunities to identify an evidence-informed and clinically relevant path ahead for ACP in serious illness. To achieve our aim, we appraised 1) ACP definitions and related terminology; 2) the processes and resources essential for ACP implementation; 3) the diversity of applications of ACP; 4) variations of ACP needs across serious illness groups; 5) the challenges to programmatic implementation; and 6) the shortcomings and contextual limitations of ACP research to date. These points are examined with an understanding of the inherent evolution and fluctuation of patient and family needs in the context of serious illness. We conclude with recommendations for clinical practice, research, and policy to support a balanced approach to ACP and offer a ‘building block’ framework to guide integration of ACP into serious illness care.

Methods

The ongoing debate surrounding the interpretation and implications of previous systematic and scoping review findings16,22 warranted a narrative review approach. By definition, a narrative review provides a broad overview of the research area, often addressing several domains related to a field of interest (e.g., ACP practice, research, policy); does not have a pre-defined protocol-based search method; includes studies based on authors’ research experience and relevance to the review aims; employs a non-protocol-based approach to data extraction and synthesis; and provides an interpretation of results rooted in the authors’ expertise.25 While systematic reviews may provide reproducibility and traceability due to strict methodology adherence, narrative reviews facilitate critical scholarly and scientific discussion, often regarding a non-disease focused area of interest.26 Furthermore, they assist with offering expert-informed guidance from across disciplinary traditions in emerging or debated fields (e.g., ACP).27

Our discussion and observations were guided by a snowball search of empirical and related grey literature, as well as the national discourse surrounding ACP. PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar were searched using a snowball approach with the terms “advance care planning”, “advance directives”, “goal-concordant care”, “end-of-life care”, “palliative care”, “serious illness”, “serious illness communication”, “shared decision-making”, “surrogate decision-making”, “health care proxy”, “goals of care”, “patient preferences”, “patient values”, and “patient goals”. Our inclusion timeline (2000–2022) acknowledged the national shifts occurring in advance care planning law and policy. For example, in 2000, sixteen states had statutes related to advance directives, which often combined living wills and health care proxies in the same law, and there was a well-documented paradigm shift occurring from a ‘legal transactional approach’ focused on standardized legal forms to a more flexible ‘communications approach’ that prioritized a more iterative and communication-focused elicitation of patients’ values.28

To provide feasible recommendations, we employed an informal consensus process among interprofessional serious illness experts in clinical practice and research settings regarding the utility, application, and efficacy of ACP based on the search results. Collaborators are members of the Cambia Health Foundation Sojourns Scholars Leadership Development Program Advance Care Planning Special Interest Group (SIG) and represent nursing (n=5), medicine (n=9), and social work (n=2). The aims, data search and synthesis, interpretation, and recommendations were the result of unanimously approved verbal and written contributions following an in-person convening of the SIG in April 2022.

Discussion and Observations

Definitions and Related Terminology

A targeted exploration of the definition and intention of ACP is imperative to effectively appraise the field. ACP must also be critically compared to other similar communication or documentation interventions to precisely identify both similarities and differences. A Delphi panel-developed definition of ACP describes it as “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care. The goal of advance care planning is to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals, and preferences during serious and chronic illness.”5 An additional international consensus-based definition of ACP includes recommendations to adapt ACP to individual readiness, target ACP content as a person’s illness worsens, and leverage trained non-physician facilitators to guide ACP.29 For this review, we focus on ACP in the setting of a serious illness for patients of all ages. The varied clinical course and multidimensional impact of serious illness behooves clinicians to engage in ACP to explicitly identify patient and family value systems as guideposts to inform treatment planning, bridge transitional care gaps, and support end-of-life decision-making and care delivery.

Several elements of these definitions deserve highlighting. First, ACP is a process: it has multiple steps that are iteratively and longitudinally employed. The process includes delving into what matters most to people – their personal values, life goals, and preferences for medical care at some point in the future. In addition, the process of decision-making, particularly in the serious illness context at end-of-life, involves collaboration between patients and surrogates/caregivers, a weighing of the full range of options at all stages, and serial choices (e.g., a multitude of choices as opposed to one choice).30 Second, this can be done at any stage of health. Preferences for medical care should be targeted based on an individual’s illness and illness trajectory (e.g., use of mechanical ventilation in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), which may be more salient during serious illness. Third, the ACP process aims to achieve an alignment of medical care delivery - either at a current or future timepoint - with what matters most to people from their present, in-the-moment perspective, which is likely to evolve with their serious illness circumstances and experiences.31 Additionally, ACP is not centered on discussing immediate decisions – rather, it focuses on planning for the future in a manner aligned with an individual’s values, goals, and preferences.

It is also critical to note what is not included in available definitions. For instance, Sudore et al.’s Delphi panel5 definition does not specifically point to completion of forms or documents (e.g., advance directives), which may or may not be indicated and may vary based on setting or the individual facilitating the ACP process. Yet, in times of crisis and in the absence of available surrogate decision-makers, documentation may be helpful (e.g., the portable medical orders registry is available around-the-clock32). Policy is a consideration as documentation and form completion mandates vary widely between care settings, potentially serving as a barrier to effective and standardized ACP implementation.24,33 Additionally, their ACP definition does not specify disease type (e.g., cancer) nor the illness severity trajectory (e.g., chronic disease with exacerbations, progressively debilitating, acute onset).5 The palpable absence of the mention of clinicians, surrogate decision-makers, or children implies flexibility in how ACP might be practiced in various settings. Furthermore, the clear limitations of the definition create a substantial “burden of proof” to the suggestion that ACP is ineffective or unworthy of future clinical and empirical investment.

Given the confabulation of terms commonly used in medical communication terminology, the ACP definition must be compared to other widely used communication interventions. The terms addressed in Table 1 may be used in several different clinical circumstances. For instance, serious illness communication can be applied in acute, long-term, or in community-based care settings, but also in conversations related to hospice and/or end-of-life care. Each of these interventions may also integrate communication styles that are well-documented (e.g., empathic communication,34 motivational interviewing35), but each maintain their distinct aims and distinctions from ACP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Communication Modalities Used in Serious Illness: Aims and Comparisons with Advance Care Planning.

| Intervention | Aim | Similarities with ACP | Differences from ACP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advance Directives: “Written documents (often called living wills) that provide instructions or name a surrogate decision maker (often called health care proxy or durable power of attorney [DPOA] for healthcare), are one legal method by which patients may state preferences in advance of a period of incompetence.”94 | ⦁ Legal document assisting in patient self-determination, creating the opportunity to name a legal surrogate decision maker and provide detail about what kinds of goals, values, wishes, and preferences one has | ⦁ Aim to provide a tool whereby people can achieve medical care that aligns with their wishes, aimed for any stage of health for adults | ⦁ It is a legal document (rather than a communication intervention) |

| Discussions About Core-Health Related Values: Discussions that support patients in articulating values as a premise for medical-decision making.8 | ⦁ Ideally to support patients when clinically stable to discuss values related to their identity and dignity; affirms personhood; may assist with planning treatment options | ⦁ One component of ACP focused on elicitation of individual values that may assist patient or surrogate decision-making in current or future settings | ⦁ Not provided with the intent of making preferences for medical decision-making known, but rather fostering trust and rapport as a component of quality serious illness care |

| Shared Decision-Making: “An approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of making decisions, and where patients are supported to consider options, to achieve informed preferences.”95 | ⦁ To confer agency and independence in making medical decisions by helping individuals to make their own free, informed decisions | ⦁ Described processes anchor on what matters most to patients | ⦁ For active and in-the-moment choices |

| Serious Illness Conversations: Iterative discussions between clinicians and patients/caregivers about goals, values, preferences, and prognosis in the context of advancing serious illness or illnesses.96 | ⦁ Clinician/patient processing of advancing serious illness (building prognostic awareness) and discussion of what matters most in that context | ⦁ Iterative process; preparing for later decision-making; focusing on what matters most, not about filling out forms | ⦁ Not specifically about current/future medical decision-making or aligning medical care with wishes; targets patients with one or more serious illnesses and thus limited life span; addresses illness(es) most affecting their lives |

| Prognostic Discussions: Ongoing discussions between clinicians and patients/caregivers to describe and clarify understanding of prognosis, disease awareness, and relevant implications.97,98 | ⦁ A component of serious illness conversations (as above); clinician/patient discussion to foster disease awareness tailored to patient’s desired amount of information; may assist with clarifying goals, values, and preferences | ⦁ Ongoing process to be revisited with transitions in care, decision points, and changes in disease status and prognosis | ⦁ Not aimed at eliciting goals, values, and preferences although this may be a potential outcome |

|

Goals of Care (GOC) Conversations: Discussions of GOC, which can be defined as “the overarching aims of medical care for a patient that are informed by patients’ underlying values and priorities, established within the existing clinical context, and used to guide decisions about the use of or limitation(s) on specific medical interventions;”99,100 can be approached as early and late GOC conversations. |

⦁ To discuss and delineate the aims of, and thus make decisions about, medical care based on what matters most to patients, focusing on the current clinical context ⦁ For early conversations, could include preparing for an impending decision (i.e., next line of cancer treatment); for later conversations, making decisions about end-of-life care (i.e., application of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation) |

⦁ Focuses on what matters most, also not specifically about completing forms | ⦁ Aimed toward more “in-the-moment” medical decisions for patients with active health issues and illnesses |

| Medical Orders for Life Sustaining Treatments (MOLST): In some settings called Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST); forms that augment traditional methods for advance care planning by translating treatment preferences into medical orders, including for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), scope of treatment, artificial nutrition and/or hydration, and in some states, antibiotic use;”101 a legal order form listing individual treatments; varies by state | ⦁ To record individual treatment choices on a legal, transferrable order form to honor preferences across settings | ⦁ Created for noting preferred medical treatment choices; aims for goal-concordant care | ⦁ Legal document (rather than a conversation), actionable and clinician-signed order set, limited to individual treatment choices |

| Code Status Discussions: “Conversations eliciting patient preferences about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)”99 and intubation along with benefits, risks, likely outcomes, and alternative options | ⦁ A shared decision-making conversation where patients make choices about whether they would want CPR, in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest, with an aim of placing a code status order reflecting the patient’s self-determined choice | ⦁ Aim is to make a medical decision to honor patient’s autonomous wish | ⦁ Not by definition anchored in what matters most to patients; about a single medical decision that pertains to a cardiopulmonary arrest and the decision to intubate ⦁ Often a compulsory component during hospitalizations |

Advance Care Planning Implementation

Despite evidence showing increased patient/surrogate satisfaction with communication and care, and decreased surrogate/clinician distress,36 we – as a clinical and research community - have yet to determine which aspects of ACP are most important (e.g., exploration of goals and values, identifying a surrogate), and what endpoints are most appropriate to measure the success of ACP implementation across settings and patient populations (e.g., ACP conversation documentation rates, patient knowledge or patient-reported comfort with medical decisions, hospice utilization at the end of life). Additionally, there is significant variation in ACP approaches (e.g., didactic, workshop, game, community-based, decision aids, individualized interventions) that may, in part, explain utility, feasibility, and mixed outcomes. There are several well-established patient-facing programs to educate and engage patients to take actions for ACP including PREPARE for Your Care (https://prepareforyourcare.org/en/welcome) and the Conversation Project (https://theconversationproject.org/), among others (e.g., https://www.fivewishes.org). These programs and their materials are disseminated in communities and/or through healthcare organizations and have demonstrated improved rates of advance directive completion and conversations with loved ones and/or healthcare professionals about end-of-life care preferences. However, the impact of these patient-facing ACP programs on other pertinent outcomes is unclear.

More patients being prepared and engaged to discuss ACP does not mean that ACP has become more routinely adopted in healthcare organizations. Despite the general recognition that having ACP conversations is probably important in the delivery of person-centered care, uptake of ACP in healthcare practice has been slow.37 Lack of time, limited training, and clinicians’ discomfort to talk about ACP are frequently cited barriers.38,39 In addition, fragmented healthcare systems and lack of institutional infrastructure to support ACP across illness trajectories, clinicians, and settings are identified as structural barriers hindering effective implementation of ACP in healthcare practice.38,39 Respecting Choices® (https://respectingchoices.org/) and the Serious Illness Care Program (https://www.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care) are two of the most adopted clinician-facing programs that can support ACP, and both programs include ACP facilitation communication skill training for clinicians as well as strategies to promote system level changes to implement ACP process in routine practice (Table 2).

Table 2.

Best Practice Exemplars of Programs that Support Advance Care Planning.

| Respecting Choices® | Serious Illness Care Program (SICP) |

|---|---|

|

Background:

• Started in La Crosse, Wisconsin in 1991 as a community-wide initiative • Work of Respecting Choices® took more than 15 years of engaging entire communities collaborating with all hospitals in respective regions Components of Program: • First Steps® (FS): For any healthy adult >18yo who may have chronic illness but has no advance care plan. Goals include motivate patient planning, assist in choosing qualified healthcare agent/decision-maker, provide guidance for goals of care in event of permanent/severe, neurologic injury, complete basic documentation. • Next Steps® (NS): For patients with advancement of chronic illness (e.g., clinical triggers occur, frequent hospitalizations or clinical encounters, decline in function). • Advanced Steps® (AS): Offered as component of quality end-of-life care for frail elders and patients for whom death in following 12 months would not be unexpected. AS focused on goals of care for “timely, proactive, and specific end-of-life decisions”, ideally converted into medical orders that can be followed throughout care continuum (e.g., POLST). Outcomes: • Demonstrated successful community-wide implementation with more than 90% of people dying in that geographic region with a written advance directive, 99% of which were available in patients’ medical records at the time of death, and delivery of treatment that was consistent in the advance care plan102 • A system-wide implementation of Respecting Choices® in a large healthcare organization demonstrated the limited but meaningful positive impact of ACP in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic 6 years post-implementation, suggesting the possibility of practice culture change to integrate ACP in routine practice103 • Respecting Choices®, or derivative models, are adopted by healthcare organizations nationally and internationally Implications: • Outcomes demonstrated by the original work of Respecting Choices® have not been replicated in subsequent studies. • Implementation in one healthcare system without engagement and buy-in from broader organizations or communities may not suffice to change culture and cement ACP into practice • Materials not free for equitable access and dissemination |

Background:

• Began as a communication training for outpatient discussion of GOC with patients • Has evolved into a program to help build healthcare systems that facilitate earlier, more frequent, and better GOC conversations with patients • Focuses on patients’ goals and values rather than making decisions about future end-of-life care or completing documents; targets patients who are currently living with serious illness, not healthy individuals • Includes communication training for clinicians using the Serious Illness Conversation Guide and strategies to make Serious Illness Conversations (SICs) part of routine practice Components of SIC Guide: • Setup (e.g., asking patient permission to discuss advance planning in context of illness • Assess (e.g., patient understanding, how much information patients want to know about illness in future) • Share prognosis (e.g., in terms of uncertainty, time, or function) • Explore (e.g., goals, fears and worries, strengths, critical abilities, willingness to endure for time gain, loved ones’ knowledge of priorities/wishes) • Close (e.g., reviewing and reflecting conversation, clinician recommendation, partnership statements) Outcomes: • SICP demonstrated educational effectiveness in improving clinicians’ confidence in, satisfaction with, and frequency of engaging patients in ACP conversations104–107 • SICP studies have also demonstrated decreased anxiety and depression in oncology patients but no significant differences in patient peacefulness or the receipt of goal-concordant care104 • SICP is adopted in various specialty areas beyond oncology as well as primary care settings nationally and internationally108 Implications: • Materials free for equitable access and dissemination • Data on successful implementation of SICP in practice and impact on patient/system outcomes are limited |

Another practical aspect is the introduction of ACP billing codes in 2016, whereby the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) encourages practitioners to have more ACP conversations with patients by reimbursing them for their time in such discussions. From 2016 to 2019, the number of ACP claims among beneficiaries who enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare increased from 17,000 to 120,000 per month.40 However, ACP claim prevalence remains low (3.7% of beneficiary outpatient claims) even for high-risk populations (<7.5% of beneficiaries who died within the year).40 The utility of ACP billing codes remains unclear in their current iteration, leading to confusion regarding time allocation for ACP, skepticism and/or discomfort about ACP, and questions regarding which types of clinicians are reimbursed for ACP interventions. Additional clarity in ACP billing codes by CMS could contribute to greater success with ACP practice and a potential decrease in the use of low value end-of-life health care services.41

Applications of Advance Care Planning

Multiple factors must be considered for integrated ACP processes, including but not limited to educating clinicians in ACP and serious illness conversation, documentation expectations and requirements, institutional mandates, financial or other incentives, and utilization and tracking of documented ACP data in electronic health record (EHR) systems.2,3 EHRs may present both barriers and facilitators to documenting ACP discussions given diverse templates, inconsistent charting practices, and non-specific medical record guidance on where to enter ACP-related information.42,43 Innovations have been spearheaded in various health systems, including a “Values Tab” initiated in a comprehensive cancer center to centralize patient-identified values in an easily identifiable location.8,44 Although education on ACP processes may be contextualized to individual institutions and systems, training through national platforms may also be used as available (e.g., VitalTalk; https://www.vitaltalk.org).

A key consideration is teamwork and collaboration that likely includes several roles to negotiate for streamlined results, i.e., – who does what? These tasks might include facilitating ACP discussions, following up on incomplete conversations, and taking accountability for EHR documentation and navigation. Given that ACP is a process, as previously noted, multiple stakeholders are likely to engage several iterative conversations throughout the care continuum.

Variations Across Major Serious Illnesses and Patient Groups

Patients with various medical conditions experience unique illness trajectories (e.g., dementia, congestive heart failure, advanced cancer, multiple co-morbid conditions) and thus unique ACP needs. For instance, there may be diverse ACP considerations and applications for patients with cancer (e.g., clarifying utility of cancer-directed treatment options in the context of patient/family values); neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., leveraging cognitive function to elicit additional concerns, worries, and fears regarding functional decline and dependence on caregivers); end-stage organ diseases (e.g., prompting broader serious illness communication and goals clarification amid rapidly changing clinical circumstances); and stroke and cerebrovascular diseases (e.g., assisting to reassess goals of care and wishes in stroke survivors post-hospitalization). Additionally, states of wellness or pre-illness call for a different kind of ACP adapted to the clinical context.45 In this section, we discuss explicit considerations for dementia, other nonmalignant chronic illnesses, and ACP in the pediatric population.

Dementia and Other Nonmalignant Chronic Illnesses

Specific guidance for ACP in early dementia is emerging,46,47 and actively addresses family involvement for early vs late-stage dementia. Other challenges include engaging patients with undiagnosed dementia, keeping patients involved at the margin of their decision-making capacity, and potentially lacking the skills needed to engage with patients with dementia. This can present a problem of “shared decision-making” in cognitive impairment, and thus there is an emerging preference for “supported decision-making” or “facilitated decision-making” that allows for involvement of persons at the margin of decision-making capacity.48

Among patients with non-malignant advanced chronic illness (e.g., cirrhosis, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, COPD) rates of ACP completion are exceedingly low.38,49–51 Treatment decision-making among these patients with advanced stages of disease often focuses on prolongation of life and reliance on advanced treatments (e.g., liver transplant, ventricular assist device for heart failure), rather than on end-of-life decision-making.49,51 As a result, specialist clinicians may be reluctant to consider limiting disease-modifying treatments in the context of a potentially fluctuating prognosis. Other significant barriers that reduce ACP among these patients include prognostic uncertainty, insufficient time during clinical encounters, lack of serious illness conversations training among specialists, and a lack of communication/protocols regarding who (i.e., primary care provider vs. specialist) is responsible for initiating these conversations. Given the prognostic unpredictability among many of these patients, discussions involving future health states may be especially challenging and nuanced for some clinicians, who are often ill-prepared for these conversations.1,2 Serious illness communication skills are critical in these situations which may indicate an enhanced role for communication training for specialists or involvement of specialist palliative care in this patient population. Unfortunately, these services are less readily available in outpatient settings where these patients receive most of their care.52

Another important group of patients in need of enhanced ACP practices are those in a state of chronic critical illness.53 These are patients who survived an initial medical insult but remain dependent on intensive care for a prolonged period, such as patients who need long-term mechanical ventilation. Clinical teams and patients’ surrogate decision-makers may struggle to align on the goals of care and a common understanding of the clinical condition, which can all devolve into seemingly unbridgeable paths.54 Earlier ACP in these clinical contexts have the potential to align goals of care with treatment received and may also reduce decisional burden among surrogates of patients in the intensive care unit.55 The opposite may also may be true: ACP preferences documented earlier in the disease may lack relevance in the current clinical context, leaving surrogates and/or clinicians in a lurch to actualize such preferences – further underscoring the need to treat ACP as a process. The COVID-19 pandemic and influx of critically ill patients highlighted the need for enhanced ACP in the setting of acute life-threatening illness, especially among older adults with chronic illness, and the need to increase ACP for individuals in the community prior to hospitalizations.56

Pediatric Populations

As is true for adults, the terminology and corresponding practice of ACP can be confusing in pediatric populations. Here, advance directives are less relevant, as parents and legal guardians are pre-defined surrogate decision-makers. Anticipatory guidance and the incorporation of family preferences into care plans are standard. A child’s cognitive and developmental abilities to participate in their care plans are constantly evolving, demanding that the concepts of ACP are revisited serially over multiple timepoints with multiple family and healthcare team members. For most families (and clinicians), the death of a child feels unnatural and highly traumatic, even if it is anticipated. Together, pediatricians and their patients may resist the label and implications of “ACP.” Perhaps for these reasons, there are far fewer studies of ACP in pediatric than adult patient populations.

In a recent systematic review of pediatric ACP, 1 of 21 identified articles focused on the initiation of ACP, and the remaining 20 focused on decision-making at the end of life, including resuscitation and cessation of life- sustaining medical technologies.57 When the terminology is broadened to include complex conversations about a child’s prognosis and a family’s corresponding goals and values, ACP helps clinicians align with the family and deliver goal-concordant care,58,59 helps patients and family caregivers understand one another,60 and reduces patient (and family/surrogate) suffering.61 Pediatric patients and families want to talk more about their illness, including worst-case scenarios, and most find ACP discussions helpful.62,63 In fact, ACP may be an opportunity to accommodate pediatric patients’ emerging autonomy and engage them as ‘active stakeholders’ in their serious illness communication process.64 Pediatric ACP does not cause distress, anxiety, or depression, and it is not burdensome to clinicians or their loved ones.65

The number of children with complex serious illness is growing, and these children are experiencing multiple comorbidities and prolonged hospitalizations.66 The demand for pediatric ACP will increase. And yet, ACP delivery is currently variable and dependent on pediatric subspecialty and clinicians’ prior training.67 Many pediatric clinicians delay or avoid ACP discussions altogether until a crisis point, even when death is imminent. Several groups have suggested techniques to overcome such barriers, including guidelines for ACP conversations,68,69 models to integrate ACP with other psychosocial services,65 and age-targeted ACP programs.60 Earlier involvement of the pediatric palliative care team can also support successful ACP,70 as well as an expanded team-based approach that leverages the skills of the larger team such as child life specialists.71,72 Ultimately, as is true in the care for adults with serious illness, pediatric clinicians must strive to standardize and operationalize ACP language and skillful practice.

Requirements for Programmatic Success

ACP processes involve various stakeholders, including patients and their surrogates, healthcare clinicians, and the broader, non-medical community in which patients live. Patients and their surrogates must be equal partners with healthcare clinicians in the ACP process. Ideally, patients would be encouraged to appoint a trusted surrogate decision-maker (healthcare proxy) and that surrogate would be iteratively and collaboratively engaged in high quality discussions in advance of when actual medical decisions must be made.16 Surrogate decision-makers may experience less guilt, depression, anxiety, and decisional conflict when they have had conversations regarding patient care preferences well before serious illness and the end of life.55 Moreover, the distress experienced by caregivers has the potential to be mitigated or prevented with psychosocial support73 and educational interventions that target their engagement, attitudes, and knowledge about ACP.74

Both specialty palliative care clinicians (interprofessional palliative care consult teams, including primary team members with subspecialty training in palliative medicine) and primary palliative care clinicians (primary teams delivering primary/generalist level palliative care) are key stakeholders in ACP provision.75 Due to primary treating clinicians’ longitudinal therapeutic relationships with their patients and their understanding of the underlying illness, the training of clinicians who practice primary palliative care in ACP processes can be adapted to their individual team and clinical workflows and protocols, as well as their individual disease specialty (e.g., cardiology). ACP skills are in purview of all primary medical teams and distinguished from complex care challenges (e.g., refractory symptomatic distress, complex psychosocial dynamics, existential or spiritual crisis, assistance with maladaptive coping in end-of-life care) that may require specialty palliative care consultation.75

The broader, non-medical community represents another key ACP stakeholder, particularly among historically marginalized groups.76 For example, one study demonstrated that Black community-dwelling residents are more likely to value collective decision-making, interdependence, and interconnectedness compared to White residents.77 Moreover, the public’s awareness of ACP does not always translate into taking action to identify a healthcare proxy.78 Several factors underlie the varied and often limited involvement in ACP by community dwelling individuals and include mistrust of the healthcare system, low health literacy, confidence that they are aware of their loved ones’ wishes about future care, and an inability to engage due to other life stressors across the entire biopsychosocial spectrum.78 Because an individual’s effort to change their health practices are mediated by various social determinants of health, possible solutions include educational interventions that provide racially, ethnically, and culturally underrepresented groups with multilingual and culturally inclusive ACP materials. Most research interventions in this area have included various minoritized groups, utilized strategies that target individual-level factors influencing health disparities, and considered outcomes related to ACP knowledge, attitudes, and completion.79 Additional translational and community-based participatory research initiatives may be needed to better understand and codify the role of lay navigators in facilitating ACP in community-based settings beyond traditional and potentially inaccessible medical contexts.80,81

Shortcomings and Contextual Limitations of ACP Research

Decades of ACP research in various patient populations (e.g., dementia, cancer, heart failure) across diverse care settings (e.g., outpatient, nursing home, oncology clinic, intensive care unit) have not demonstrated direct impact on the delivery of goal-concordant care or better end-of-life care.15,16 Some experts point to multifactorial reasons for these shortcomings, including the confusion around how ACP is defined, lack of clarity on the interventions and outcomes studied, and the need for systems-level change that supports training clinicians to elicit, discuss, and document what’s most important to patients in a way that leads to such patient values being visible and available for re-broaching when medical decisions need to be made “in the moment.”13,82 The lack of an established and reliable method to measure goal-concordant care is a significant barrier, as is the frequent conflation of “ACP research” and “advance directive research.”23 The mixed results in ACP research are clearly informed by the varied outcomes being used to measure ACP efficacy. The collective research community may need to ultimately redefine the interpretation of “successful ACP” and shift from long-range emphasis on healthcare utilization to more immediate impacts on patient and surrogate experiences.5

Implications and Recommendations

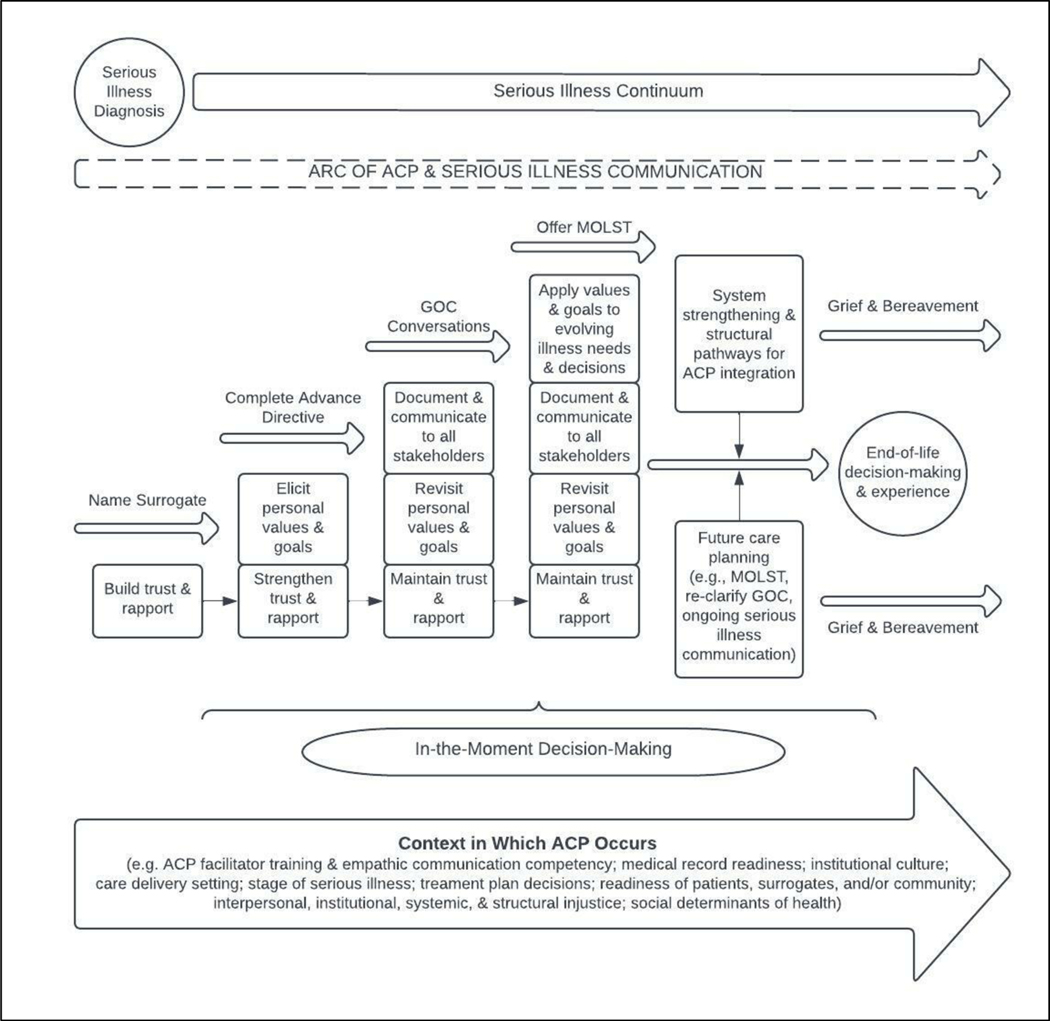

To acknowledge and anticipate these shortcomings in clinical practice, we recommend a „building block’ framework to incorporate patient- and surrogate-centered ACP throughout the serious illness continuum to guide both clinical practice and future studies. Throughout Figure 1, we recognize the many factors that inform ACP (e.g., patient and surrogate readiness, stage of serious illness, social determinants of health) and the need for system strengthening to promote person- and surrogate-centered end-of-life decision-making and goal-concordant end-of-life experiences from serious illness diagnosis to end-of-life and bereavement. Sudore & Fried’s core elements to support in-the-moment decision-making are integral to this framework, particularly their call for choosing an appropriate surrogate decision-maker, clarifying and articulating patients’ values over time, and establishing leeway in surrogate decision-making.83 We extend these surrogate-specific considerations into the end-of-life and bereavement phase, supported by evidence that suggests that ACP enhances surrogates’ death preparedness and relational bonds with the patient,84 as well as supporting surrogates’ peace of mind during and following end-of-life decision making.85 Our framework also recognizes 1) previously identified significant associations between full engagement of ACP (e.g., documented living will, identification of surrogate, end-of-life discussions) and caregivers’ positive perceptions of end-of-life and 2) partial ACP engagement as a clinically relevant and modifiable outcome of end-of-life experiences.86 Previous work by Izumi and Fromme informs the arc of ACP and serious illness communication that evolves over time, accompanied by varied and iterative needs.45

Figure 1.

‘Building Block’ Approach to Advance Care Planning Throughout the Serious Illness Continuum.

In alignment with narrative review methodology, our team of interprofessional palliative specialists makes several key clinical practice, research, and policy recommendations to guide future discourse regarding ACP efficacy, value, and application (Table 3). Despite the framework provided and ample recommendations that emphasize ACP is a process – this point cannot be overstated. Future interventions should continue to conceptualize and engage ACP as a health behavior and, as such, revisit, refine, and maintain it over time,87,88 as well as to actively dismantle structures and mandates that view ACP as a ‘one and done’ procedure.

Table 3.

Recommendations for a Balanced Approach to Advance Care Planning.

| Domain | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Serious Illness Clinical Practice: Holistic ACP for Patients and their Social Support Structures | ⦁ Approach ACP as an opportunity to build rapport, foster trust, promote relationship-based care, and elicit patient and family values, goals, preferences, and needs beyond documentation requirements ⦁ Foster intentional ACP discussions throughout the trajectory of serious illness care, with particular attention to moments of prognostic or psychosocial transitions, greater severity of symptoms, or increased proximity to end-of-life ⦁ Normalize high-quality ACP discussions as a core standard of quality primary care, primary palliative care, and serious illness care, using discussion findings to further explore changing values, etc. ⦁ Actively engage surrogates, caregivers, and other social supports into ACP discussions to promote inclusivity, co-participation, and alleviate stressors that may contribute to decisional conflict ⦁ Advocate for documentation and EHR improvements that assist with ongoing tracking of ACP preferences to ensure an iterative ACP dialogue with care recipients ⦁ Partner with palliative specialists to improve serious illness communication skills ⦁ Include ACP preferences as a part of patient “hand-off” and when collaborating with interprofessional colleagues and/or consulting services |

| Serious Illness and ACP Research | ⦁ Design and implement longitudinal research to evaluate patient/family and clinician experiences with ACP starting at time of serious illness diagnosis to bereavement ⦁ Explore clinician and system barriers, needs, and facilitators to ACP discussions and use implementation science to guide interventions that support clinician confidence during ACP encounters ⦁ Evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of training programs that assist clinicians, patients, surrogates, communities, and lay navigators to develop and hone ACP communication skills ⦁ Advocate for increased ACP research funding to address evidence gaps and promote comprehensive investigation of ACP utility ⦁ Compare ACP with other forms of serious illness communication and generate additional data on the association between ACP and health services at end of life ⦁ Design valid tools to measure clinician and patient/family experiences and perceptions of ACP with particular attention to the high-stakes circumstances inherent to serious illness |

| Serious Illness and ACP Policy | ⦁ Increase fiscal investments in ACP research in a multitude of settings, including acute and critical care, long-term care, community-based and nursing home care, and throughout serious illness care delivery for pediatric and other vulnerable and/or historically excluded populations ⦁ Call for required training to promote primary palliative care and serious illness care skills and communication for all clinicians by integrating and supporting key legislation, such as the Palliative Care and Hospice Education Training Act (PCHETA) ⦁ Revise ACP billing codes to promote robust clinician-patient discussions, clarity on reimbursement, user incentives, and frequency of use ⦁ Support public health education regarding ACP awareness and patient/family empowerment to address ACP preferences with clinicians and care teams, particularly in serious illness ⦁ Invest in the expansion of palliative care specialist services to support timely ACP communication in the serious illness context |

Limitations

There are several limitations. First, narrative reviews lack the protocol-based rigor of systematically conducted reviews and are more easily subject to bias. However, we have mitigated biases by transparently articulating team positionality, discipline, and roles; clearly articulating all research questions; and recognizing both the strengths (authors’ clinical and research expertise) and weaknesses (potential bias, absence of protocol) of narrative reviews.

Second, although briefly mentioned, our discussion on the role of ACP in contributing to or exacerbating serious illness care disparities is insufficient. More robust investigation and policy changes are needed to dismantle structural barriers to equitable serious illness care and ensure adequate preparation and support for shared decision-making throughout illness trajectories, including at end-of-life and bereavement. Researchers have shown that when patients have equitable opportunities to complete advance directives (e.g., partial ACP engagement86), demographic characteristics are not consistently associated with advance directive completion, suggesting disparities more linked to access than patient willingness to participate in ACP.89 Whether informed by variation in clinical practice patterns,90 insurance coverage (e.g., Medicaid status),91 or other barriers faced by minoritized people,79,92,93 all forms of bias and injustice – interpersonal, institutional, systemic, and structural - must be exposed and strategically dismantled in relation to ACP access, provision, processes, and outcomes.

Finally, although our team represents nursing, social work, and medicine, with members who are adept practitioners and researchers in several specialties related to serious illness care, there are a number of key stakeholders missing, including but not limited to chaplains and faith leaders, lay navigators, and community-based organizations representatives. Future work will need to bridge these gaps and create unified, collaborative approaches to ACP that foster inclusion, sustainability, and interventions relevant to the setting.

Conclusion

There is arguably much to be gleaned from the ACP process when viewed as a vehicle to build relationships; foster trust; elicit patient values, goals, and preferences; and identify social support mechanisms. Negative findings are fundamental to the scientific endeavor, and it would be prudent not to abandon current and future streams of ACP research, but rather continue to adapt accordingly. We advocate a balanced approach to ACP – one in which health professionals leverage the ACP process to promote person- and family-centered care throughout the trajectory of serious illness, while being accountable for employing other communication interventions to optimize pragmatism in the face of unpredictable clinical circumstances and to bridge gaps in care that ACP fails to address.

Funding:

WER & ASE acknowledge the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. CJC is funded by NIH/NINDS Award K23NS099421.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest Statement:

All authors are members of the Cambia Health Foundation Sojourns Scholars Leadership Development Program Advance Care Planning Special Interest Group. The views expressed in this manuscript rest solely with the authors and do not reflect the views, opinions, position, or endorsement of Cambia Health Foundation. These authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahluwalia SC, Levin JR, Lorenz KA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for advance care planning communication during outpatient clinic visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(4):445–451. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1917-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knutzen KE, Sacks OA, Brody-Bizar OC, et al. Actual and Missed Opportunities for End-of-Life Care Discussions With Oncology Patients: A Qualitative Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113193. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication About Serious Illness Care Goals: A Review and Synthesis of Best Practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Back AL, Fromme EK, Meier DE. Training Clinicians with Communication Skills Needed to Match Medical Treatments to Patient Values. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S435–S441. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2017;53(5):821–832.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, Sudore RL. Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakke BM, Feuz MA, McMahan RD, et al. Surrogate Decision Makers Need Better Preparation for Their Role: Advice from Experienced Surrogates. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(6):857–863. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2021.0283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein AS, Desai AV, Bernal C, et al. Giving Voice to Patient Values Throughout Cancer: A Novel Nurse-Led Intervention. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2019;58(1):72–79.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.You JJ, Dodek P, Lamontagne F, et al. What really matters in end-of-life discussions? Perspectives of patients in hospital with serious illness and their families. CMAJ. 2014;186(18):E679–687. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, Thompson G, Dufault B, Harlos M. Eliciting Personhood Within Clinical Practice: Effects on Patients, Families, and Health Care Providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):974–980.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein AS, Shuk E, O’Reilly EM, Gary KA, Volandes AE. “We have to discuss it”: cancer patients’ advance care planning impressions following educational information about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Psychooncology. 2015;24(12):1767–1773. doi: 10.1002/pon.3786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vig EK, Sudore RL, Berg KM, Fromme EK, Arnold RM. Responding to surrogate requests that seem inconsistent with a patient’s living will. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(5):777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudore RL. A piece of my mind. Can we agree to disagree? JAMA. 2009;302(15):1629–1630. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahan RD, Tellez I, Sudore RL. Deconstructing the Complexities of Advance Care Planning Outcomes: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? A Scoping Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(1):234–244. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison RS. Advance Directives/Care Planning: Clear, Simple, and Wrong. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2020;23(7):878–879. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison RS, Meier DE, Arnold RM. What’s Wrong With Advance Care Planning? JAMA. 2021;326(16):1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.16430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis JR. Three Stories About the Value of Advance Care Planning. JAMA. 2021;326(21):2133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.21075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness, Board on Health Care Services, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Challenges and Opportunities of Advance Care Planning: Proceedings of a Workshop. (Graig L, Friedman K, Alper J, eds.). National Academies Press; 2021:26119. doi: 10.17226/26119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrison RS, Meier DE, Arnold RM. Controversies About Advance Care Planning-Reply. JAMA. 2022;327(7):686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell SL. Controversies About Advance Care Planning. JAMA. 2022;327(7):685–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers J, Steinberg L, Seow H. Controversies About Advance Care Planning. JAMA. 2022;327(7):684–685. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rigby MJ, Wetterneck TB, Lange GM. Controversies About Advance Care Planning. JAMA. 2022;327(7):683–684. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudore RL, Hickman SE, Walling AM. Controversies About Advance Care Planning. JAMA. 2022;327(7):685. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heyland DK. Advance Care Planning (ACP) vs. Advance Serious Illness Preparations and Planning (ASIPP). Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3). doi: 10.3390/healthcare8030218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pae CU. Why Systematic Review rather than Narrative Review? Psychiatry Investig. 2015;12(3):417–419. doi: 10.4306/pi.2015.12.3.417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faggion CMJ, Bakas NP, Wasiak J. A survey of prevalence of narrative and systematic reviews in five major medical journals. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0453-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins JA, Fauser BCJM. Balancing the strengths of systematic and narrative reviews. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(2):103–104. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabatino CP. The evolution of health care advance planning law and policy. Milbank Q. 2010;88(2):211–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00596.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):e543–e551. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30582-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levoy K, Tarbi EC, De Santis JP. End-of-life decision making in the context of chronic life-limiting disease: a concept analysis and conceptual model. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(6):784–807. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Creutzfeldt CJ, Holloway RG. Treatment Decisions for a Future Self: Ethical Obligations to Guide Truly Informed Choices. JAMA. 2020;323(2):115–116. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National POLST. POLST Registries. POLST Registries. Published 2022. Accessed May 9, 2022. https://polst.org/registries/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart M, Stepita R, Berall A, Sokolowski M, Karuza J, Katz P. Development of an Advance Care Planning Policy within an Evidenced-Based Evaluation Framework. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. Published online April 13, 2022:10499091221077056. doi: 10.1177/10499091221077057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5748–5752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollak KI, Gao X, Arnold RM, et al. Feasibility of Using Communication Coaching to Teach Palliative Care Clinicians Motivational Interviewing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(4):787–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vranas KC, Plinke W, Bourne D, et al. The influence of POLST on treatment intensity at the end of life: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(12):3661–3674. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meehan E, Foley T, Kelly C, et al. Advance Care Planning for Individuals With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Scoping Review of the Literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(6):1344–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandar M, Brockstein B, Zunamon A, et al. Perspectives of Health-Care Providers Toward Advance Care Planning in Patients With Advanced Cancer and Congestive Heart Failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(5):423–429. doi: 10.1177/1049909116636614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer MK, Jacobson M, Enguidanos S. Advance Care Planning For Medicare Beneficiaries Increased Substantially, But Prevalence Remained Low: Study examines Medicare outpatient advance care planning claims and prevalence. Health Affairs. 2021;40(4):613–621. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissman JS, Reich AJ, Prigerson HG, et al. Association of Advance Care Planning Visits With Intensity of Health Care for Medicare Beneficiaries With Serious Illness at the End of Life. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(7):e211829. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kantor MA, Scott BS, Abe-Jones Y, Raffel KE, Thombley R, Mourad M. Ask About What Matters: An Intervention to Improve Accessible Advance Care Planning Documentation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2021;62(5):893–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Desai AV, Agarwal R, Epstein AS, et al. Needs and Perspectives of Cancer Center Stakeholders for Access to Patient Values in the Electronic Health Record. JCO Oncology Practice. 2021;17(10):e1524–e1536. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desai AV, Michael CL, Kuperman GJ, et al. A Novel Patient Values Tab for the Electronic Health Record: A User-Centered Design Approach. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e21615. doi: 10.2196/21615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izumi S, Fromme EK. A Model to Promote Clinicians’ Understanding of the Continuum of Advance Care Planning. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2017;20(3):220–221. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrison Dening K, Sampson EL, De Vries K. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. Palliat Care. 2019;12:1178224219826579. doi: 10.1177/1178224219826579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.deLima Thomas J, Sanchez-Reilly S, Bernacki R, et al. Advance Care Planning in Cognitively Impaired Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(8):1469–1474. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson A, Karlawish J, Largent E. Supported Decision Making With People at the Margins of Autonomy. Am J Bioeth. 2021;21(11):4–18. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1863507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel AA, Ryan GW, Tisnado D, et al. Deficits in Advance Care Planning for Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis at Liver Transplant Centers. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(5):652–660. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately One In Three US Adults Completes Any Type Of Advance Directive For End-Of-Life Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(7):1244–1251. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuart B. The nature of heart failure as a challenge to the integration of palliative care services. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2007;1(4):249–254. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282f283b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berger GN, O’Riordan DL, Kerr K, Pantilat SZ. Prevalence and characteristics of outpatient palliative care services in California. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2057–2059. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AA, Carson SS. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(4):446–454. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0210CI [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han JJ, Raiten JM. Escaping the Labyrinth - On Finding a Common Path Forward in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(24):2269–2271. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2103422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chiarchiaro J, Buddadhumaruk P, Arnold RM, White DB. Prior Advance Care Planning Is Associated with Less Decisional Conflict among Surrogates for Critically Ill Patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(10):1528–1533. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201504-253OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosenberg AR, Popp B, Dizon DS, El-Jawahri A, Spence R. Now, More Than Ever, Is the Time for Early and Frequent Advance Care Planning. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(26):2956–2959. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carr K, Hasson F, McIlfatrick S, Downing J. Factors associated with health professionals decision to initiate paediatric advance care planning: A systematic integrative review. Palliat Med. 2021;35(3):503–528. doi: 10.1177/0269216320983197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weaver MS, Anderson B, Cole A, Lyon ME. Documentation of Advance Directives and Code Status in Electronic Medical Records to Honor Goals of Care. J Palliat Care. 2020;35(4):217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompkins JD, Needle J, Baker JN, et al. Pediatric Advance Care Planning and Families’ Positive Caregiving Appraisals: An RCT. Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020029330. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lyon ME, Squires L, Scott RK, et al. Effect of FAmily CEntered (FACE®) Advance Care Planning on Longitudinal Congruence in End-of-Life Treatment Preferences: A Randomized Clinical Trial. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(12):3359–3375. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02909-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hein K, Knochel K, Zaimovic V, et al. Identifying key elements for paediatric advance care planning with parents, healthcare providers and stakeholders: A qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2020;34(3):300–308. doi: 10.1177/0269216319900317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orkin J, Beaune L, Moore C, et al. Toward an Understanding of Advance Care Planning in Children With Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2020;145(3):e20192241. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Needle JS, Peden-McAlpine C, Liaschenko J, et al. “Can you tell me why you made that choice?”: A qualitative study of the influences on treatment decisions in advance care planning among adolescents and young adults undergoing bone marrow transplant. Palliat Med. 2020;34(3):281–290. doi: 10.1177/0269216319883977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stein A, Dalton L, Rapa E, et al. Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of their own life-threatening condition. Lancet. 2019;393(10176):1150–1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33201-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fladeboe KM, O’Donnell MB, Barton KS, et al. A novel combined resilience and advance care planning intervention for adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer: A feasibility and acceptability cohort study. Cancer. 2021;127(23):4504–4511. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruth AR, Boss RD, Donohue PK, Shapiro MC, Raisanen JC, Henderson CM. Living in the Hospital: The Vulnerability of Children with Chronic Critical Illness. J Clin Ethics. 2020;31(4):340–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Song IG, Kang SH, Kim MS, Kim CH, Moon YJ, Lee J. Differences in perspectives of pediatricians on advance care planning: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00652-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosenberg AR, Wolfe J, Wiener L, Lyon M, Feudtner C. Ethics, Emotions, and the Skills of Talking About Progressing Disease With Terminally Ill Adolescents: A Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1216. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sisk BA, Friedrich AB, DuBois J, Mack JW. Emotional Communication in Advanced Pediatric Cancer Conversations. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2020;59(4):808–817.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harmoney K, Mobley EM, Gilbertson-White S, Brogden NK, Benson RJ. Differences in Advance Care Planning and Circumstances of Death for Pediatric Patients Who Do and Do Not Receive Palliative Care Consults: A Single-Center Retrospective Review of All Pediatric Deaths from 2012 to 2016. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2019;22(12):1506–1514. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wiener L, Bell CJ, Spruit JL, Weaver MS, Thompson AL. The Road to Readiness: Guiding Families of Children and Adolescents with Serious Illness Toward Meaningful Advance Care Planning Discussions. NAM Perspect. 2021;2021. doi: 10.31478/202108a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Basu MR, Partin L, Revette A, Wolfe J, DeCourcey DD. Clinician Identified Barriers and Strategies for Advance Care Planning in Seriously Ill Pediatric Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(3):e100–e111. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Applebaum AJ, Kent EE, Lichtenthal WG. Documentation of Caregivers as a Standard of Care. JCO. 2021;39(18):1955–1958. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cruz-Oliver DM, Pacheco Rueda A, Viera-Ortiz L, Washington KT, Oliver DP. The evidence supporting educational videos for patients and caregivers receiving hospice and palliative care: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2020;103(9):1677–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus Specialist Palliative Care — Creating a More Sustainable Model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sloan DH, Gray TF, Harris D, et al. Church leaders and parishioners speak out about the role of the church in advance care planning and end-of-life care. Pall Supp Care. 2021;19(3):322–328. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bullock K. The influence of culture on end-of-life decision making. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2011;7(1):83–98. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2011.548048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grant MS, Back AL, Dettmar NS. Public Perceptions of Advance Care Planning, Palliative Care, and Hospice: A Scoping Review. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2021;24(1):46–52. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones T, Luth EA, Lin SY, Brody AA. Advance Care Planning, Palliative Care, and End-of-life Care Interventions for Racial and Ethnic Underrepresented Groups: A Systematic Review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2021;62(3):e248–e260. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fink RM, Kline DM, Bailey FA, et al. Community-Based Conversations about Advance Care Planning for Underserved Populations Using Lay Patient Navigators. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(7):907–914. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rocque GB, Dionne-Odom JN, Sylvia Huang CH, et al. Implementation and Impact of Patient Lay Navigator-Led Advance Care Planning Conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(4):682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Periyakoil VS, Gunten CF von, Arnold R, Hickman S, Morrison S, Sudore R. Caught in a Loop with Advance Care Planning and Advance Directives: How to Move Forward? J Palliat Med. 2022;25(3):355–360. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2022.0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–261. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Durepos P, Sussman T, Ploeg J, Akhtar-Danesh N, Punia H, Kaasalainen S. What Does Death Preparedness Mean for Family Caregivers of Persons With Dementia? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(5):436–446. doi: 10.1177/1049909118814240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Song MK, Metzger M, Ward SE. Process and impact of an advance care planning intervention evaluated by bereaved surrogate decision-makers of dialysis patients. Palliat Med. 2017;31(3):267–274. doi: 10.1177/0269216316652012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Levoy K, Buck H, Behar-Zusman V. The Impact of Varying Levels of Advance Care Planning Engagement on Perceptions of the End-of-Life Experience Among Caregivers of Deceased Patients With Cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37(12):1045–1052. doi: 10.1177/1049909120917899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sudore RL, Schickedanz AD, Landefeld CS, et al. Engagement in multiple steps of the advance care planning process: a descriptive study of diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1006–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01701.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, Knight SJ, Williams BA, Sudore RL. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.15325415.2008.02093.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hart JL, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Are Demographic Characteristics Associated with Advance Directive Completion? A Secondary Analysis of Two Randomized Trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):145–147. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4223-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Obermeyer Z, Powers BW, Makar M, Keating NL, Cutler DM. Physician Characteristics Strongly Predict Patient Enrollment In Hospice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):993–1000. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Starr LT, Ulrich CM, Perez GA, et al. Hospice Enrollment, Future Hospitalization, and Future Costs Among Racially and Ethnically Diverse Patients Who Received Palliative Care Consultation. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;39(6):619–632. doi: 10.1177/10499091211034383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reich AJ, Perez S, Fleming J, et al. Advance Care Planning Experiences Among Sexual and Gender Minority People. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2222993. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reich AJ, Manful A, Candrian C, et al. Use of Advance Care Planning Codes Among Transgender Medicare Beneficiaries. LGBT Health. Published online June 28, 2022. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2021.0340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Teno JM, Stevens M, Spernak S, Lynn J. Role of written advance directives in decision making: Insights from qualitative and quantitative data. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(7):439–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00132.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared Decision Making: A Model for Clinical Practice. :7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sanders JJ, Miller K, Desai M, et al. Measuring Goal-Concordant Care: Results and Reflections From Secondary Analysis of a Trial to Improve Serious Illness Communication. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2020;60(5):889–897.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Applebaum AJ, Kolva EA, Kulikowski JR, et al. Conceptualizing prognostic awareness in advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(9):1103–1119. doi: 10.1177/1359105313484782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vlckova K, Tuckova A, Polakova K, Loucka M. Factors associated with prognostic awareness in patients with cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2020;29(6):990–1003. doi: 10.1002/pon.5385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Binder AF, Huang GC, Buss MK. Uninformed consent: Do medicine residents lack the proper framework for code status discussions?: Code Status Discussions. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):111–116. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]