Abstract

Rationale and Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly altered the residency application and interview process. Due to social distancing concerns, residency programs have had to virtually showcase their program to applicants, many utilizing social media. Similarly, applicants have had to devise novel ways of assessing “goodness of fit”, one of the top factor's applicants use when ranking programs (1). Whether or not these attempts made an impact on an applicant's decision-making process has yet to be determined.

Materials and Methods

Residency candidates interviewing for a diagnostic and/or interventional radiology residency position at our institution completed an online survey. The goal of the survey was to assess the potential influence of virtual interviews, social media, and virtual events on an applicant's decision to apply to, interview at, and rank residency programs.

Results

78/156 (50%) candidates completed the survey. Thirty-five percent reported applying to more programs and 58% reported accepting more interviews than they would have if interviews were not virtual. Forty-two percent reported that social media played a vital role during the application season and 71% reported using social media to learn more about the program. Sixty-nine percent attended a virtual open house, 57% of whom reported that attending the open house influenced their decision to apply to a program. Sixty-three percent reported that attending a virtual reception influenced a program's ranking.

Conclusion

Social media has had a growing role in the medical community, and the COVID-19 pandemic likely accelerated an inevitable shift in residency program “branding” and how applicants perceive overall “goodness of fit”.

INTRODUCTION

In the years leading up to the 2020-2021 cycle, residency interviews have typically been day-long affairs, involving formal interviews, informal sessions with residents and faculty, and a tour of the facilities. While allowing for a program's further assessment of an applicant, interviews also serve as an opportunity for applicants to evaluate how compatible a program is with their own personal goals and preferences. After an anecdotally arduous and costly interview process, applicants must compare the prospective programs and submit a rank order list (ROL), typically facilitated through The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). The NRMP conducts a survey each year to determine the factors that applicants consider when selecting programs. The 2019 NRMP applicant survey found that the top three factors that applicants consider when ranking programs are: overall goodness of fit, interview day experience, and desired geographic location (1). Historically, in-person interviews have undoubtedly been instrumental in applicant decision-making.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a substantial disruption in the residency application and interview process. Due to social distancing concerns, in-person interviews were shifted to virtual platforms. During this unprecedented match cycle, programs have had to strategize in order to virtually showcase their program to applicants. Similarly, applicants have had to devise novel ways of assessing a program's overall “goodness of fit”.

The concept of residency program “branding” gained increasing traction during the 2020-2021 application cycle (2,3). Shappell et al outlined key elements of branding applicable to residency program recruitment, including brand image, brand identity, and brand experience (2). Many residency programs have utilized social media platforms and virtual events in order to capture their program's strengths and uniqueness in order to recruit applicants. Whether or not these attempts have made an impact on an applicant's decision-making process has yet to be determined.

We surveyed a group of applicants during the 2020-2021 applications cycle with the goal of assessing the potential influence of the virtual interviews, social media, and virtual events on an applicant's decision to apply, interview, and rank residency programs.

METHODS

A voluntary, anonymous online survey (Google Form) was sent to all applicants who interviewed for a diagnostic and/or interventional radiology residency position at our institution. All participants anticipated enrollment in the 2020-2021 NRMP Match Cycle. The survey was sent to applicants upon completion of their interview for a residency position at our institution and prior to the Rank Order List certification deadline. A letter signed by the research team containing the survey link was sent as an email attachment from the program coordinator. Responses from all participants were used. The survey consisted of 14 questions. The responses to 12 questions were used for data analysis. Questions #2-12 are included in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 . The first question asked if the respondent attended a virtual interview during the 2020-2021 interview season. Geographic location of candidate's medical school was assessed in question #2, accompanied by a map of the United States delineating census bureau-designated regions and divisions (New England, Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, South, West). The remaining questions were to ascertain respondents’ opinions about different aspects of the virtual interview season. To optimize response rate, these questions consisted only of di- or trichotomous (yes/no or yes/no/other) questions.

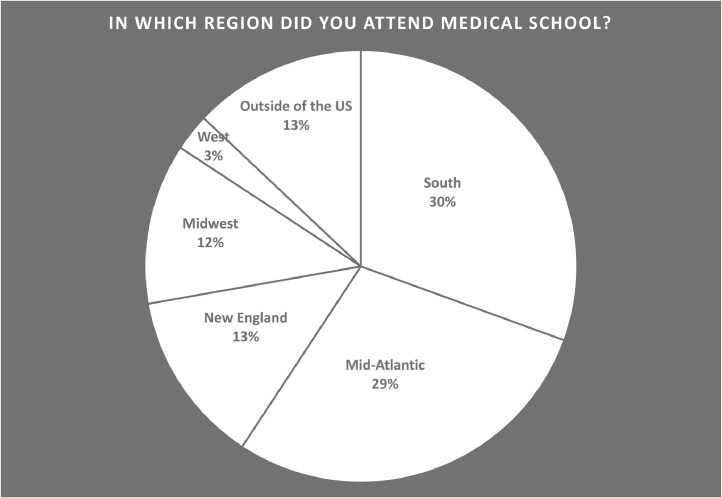

Figure 1.

Region of respondent's medical school (question #2). Thirty-one percent of survey respondents (24/78) attended medical school in the Mid Atlantic, 33% (26/78) in the South, 13% (9/78) in the Midwest, 3% (3/78) in the West, 6% (5/78) in New England, and 14% (11/78) attended medical school outside of the United States.

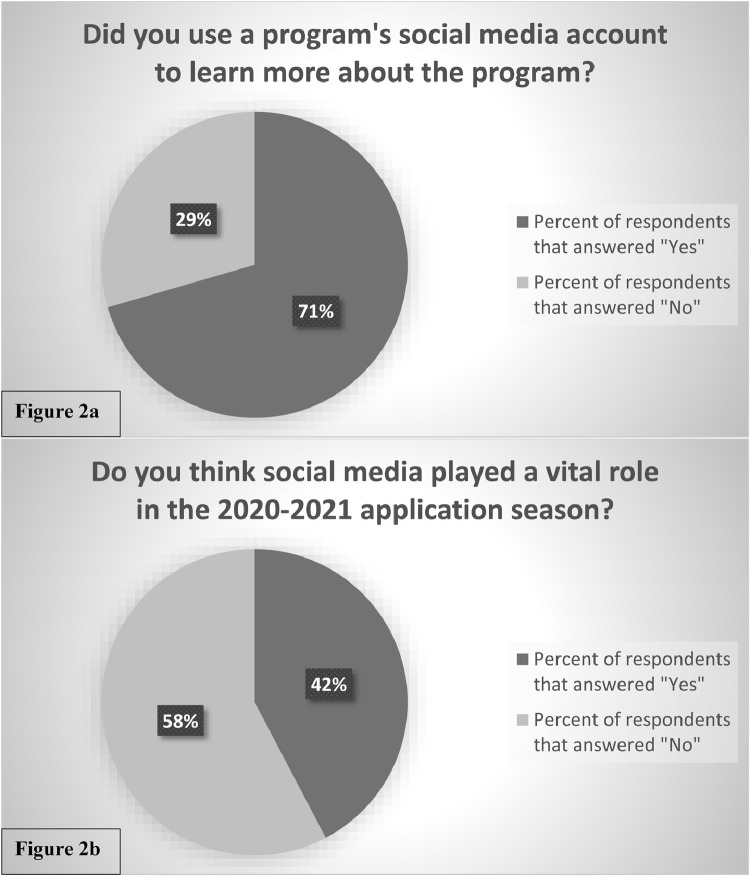

Figure 2.

Opinions on social media (questions #3,4). (A) Question #3. Seventy one percent (55/78) of respondents reported using a program's social media account(s) to learn more about a program. (B) Question #4. Forty-two percent (33/78) of respondents reported that social media played a vital role in the 2020-2021 application season.

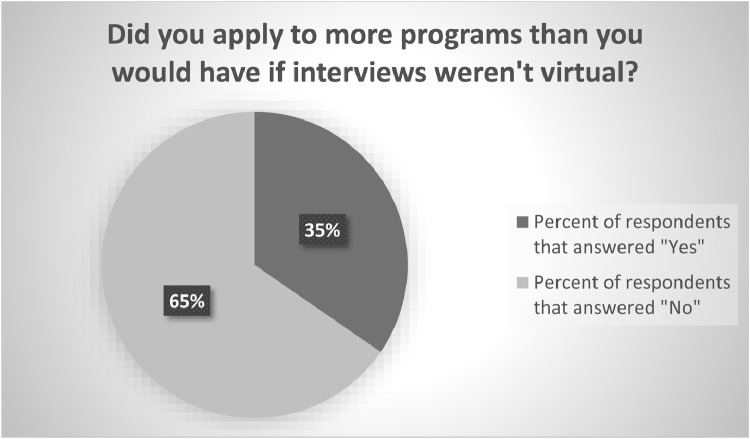

Figure 3.

Applying to programs (question #5). Thirty-five percent (27/78) of respondents reported applying to more programs than they would have if interviews were not virtual.

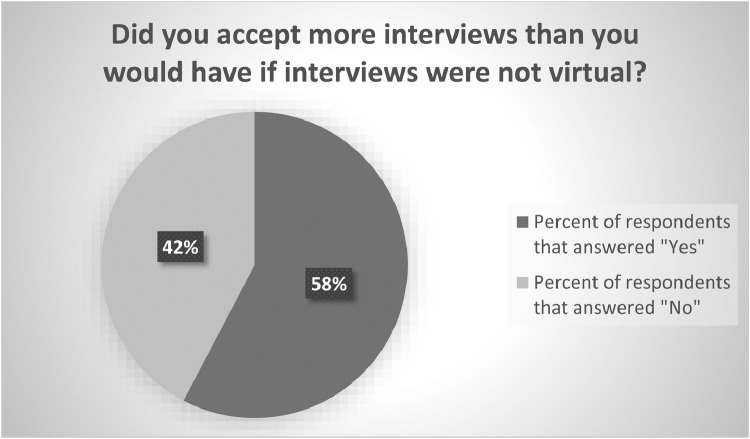

Figure 4.

Accepting interviews (question #6). Fifty-eight percent (45/78) of respondents reported accepting more interviews than they would have if interviews were not virtual.

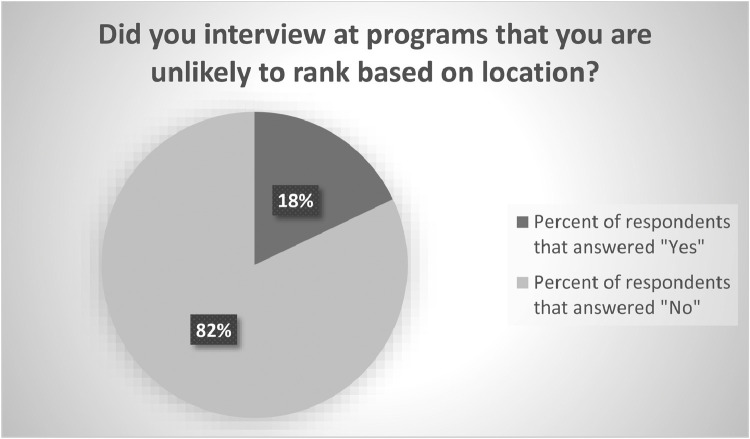

Figure 5.

Interviewing at undesirable programs (question #7). Eighteen percent (14/78) of respondents reported interviewing at programs that they were unlikely to rank based on location.

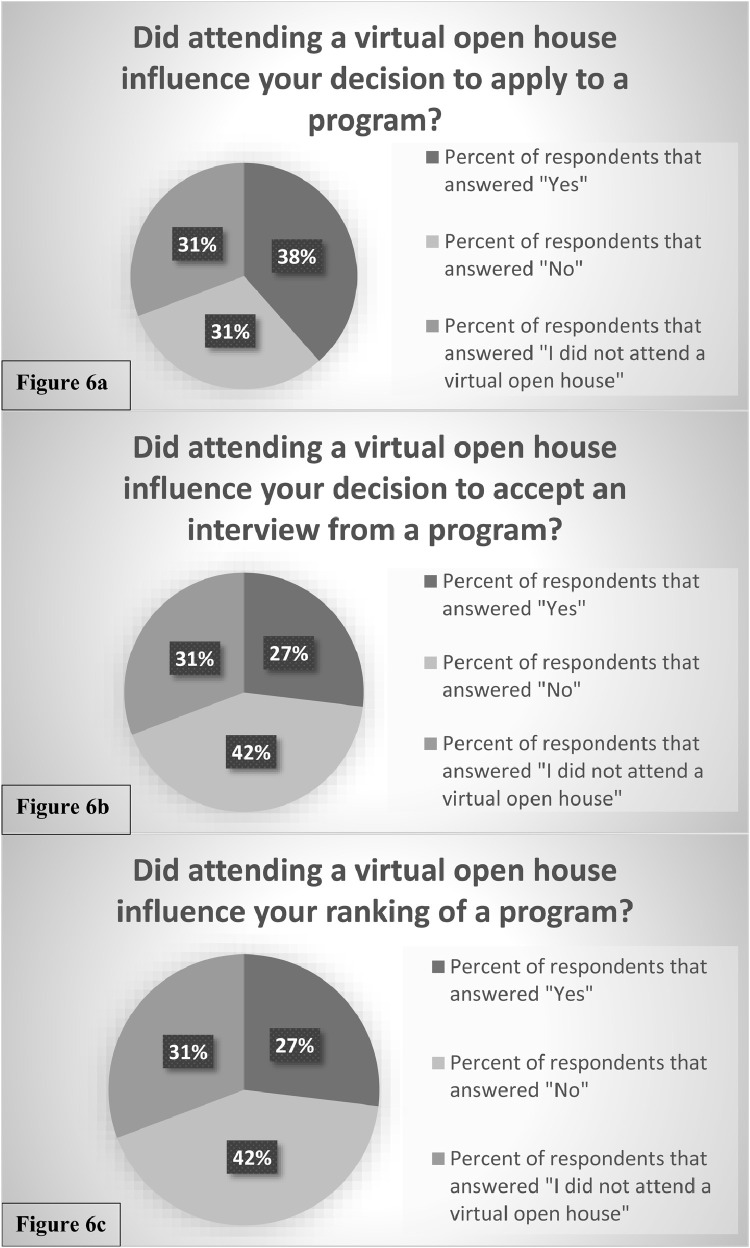

Figure 6.

Effect of virtual open houses on applicant decision-making (questions #8-10). (A) Question #8. Sixty-nine percent (54/78) reported attending a virtual open house during the 2020-2021 application cycle. Fifty-seven percent (30/54) of those in attendance reported that attending the virtual open house influenced their decision to apply to a program. (B) Question #9. Thirty-nine percent (21/54) of those who reported attending a virtual open house stated the virtual open house influenced their decision to accept an interview from a program. (C) Question #10. Thirty-nine percent (21/54) of those who attended a virtual open house reported that attending the virtual open house influenced their ranking of a program. Thirty-one percent of all respondents (24/78) did not attend a virtual open house.

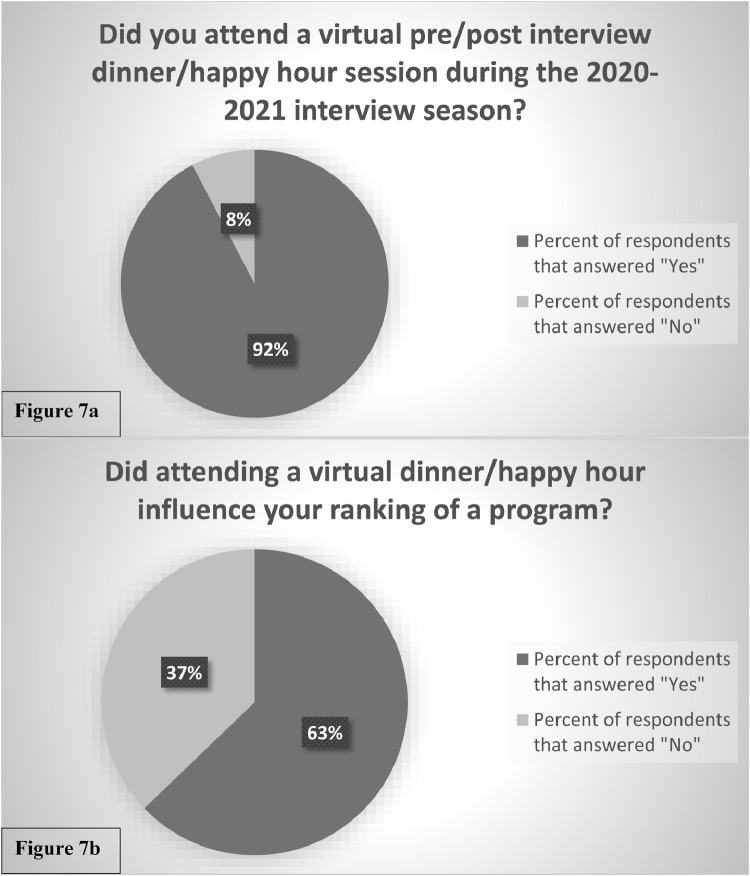

Figure 7.

Effect of virtual dinner/happy hours on applicant decision-making (questions #11-12). (A) Question #11. Ninety-two percent (72/78) respondents reported attending a virtual pre/post interview event. (B) Question #12. Sixty-three percent (49/78) respondents reported that a virtual dinner/happy hour influenced their ranking of a program.

Two questions regarding supplemental information requested from residency programs (questions #13,14) were not included in data analysis due to ambiguity in responses received and presumed misinterpretation.

Data analysis involved basic comparison of proportions of applicants who utilized virtual platforms in their decision-making process. Unpaired two sample two tailed z-test for comparison of proportions were used for subgroup analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. This study was exempt by our Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Response Rate and Demographics

Of 156 applicants that interviewed for a diagnostic and/or interventional radiology residency position at our institution, 78 (50%) survey responses were received. All respondents reported attending a virtual interview during the 2020-2021 interview cycle (Question #1). The majority of respondents interviewing at our Mid-Atlantic institution attended medical school in the Mid-Atlantic and the South, a smaller percentage of respondents attended school in the Midwest, West, New England or outside of the United States. Geographic distribution of respondents’ medical schools is shown in Figure 1.

Social Media

Seventy-one percent of respondents reported using a program's social media account to learn more about the program (Fig 2A). “Social media” includes all interactive web-based applications, including Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Participants were not asked to specify which type of social media platform they accessed. Forty-two percent felt that social media played a vital role in the 2020-2021 application cycle (Fig 2B). Of those who reported that social media did not play a vital role in the 2020-2021 application process, 60% (27/45) still reported using a program's social media page(s) to learn more about the program.

Applying to More Programs, Accepting More Interviews, and Interviewing at Programs Unlikely to be Ranked

When asked to compare the new virtual interview format with the traditional in-person model, 35% of interviewees reported applying to more programs (Fig 3) and 58% reported accepting more interviews than they would have if in-person interviews were being conducted (Fig 4). Eighteen percent reported interviewing at programs that they were unlikely to rank based on location (Fig 5). While only 18% of international medical students/graduates reported applying to more programs than they would have if interviews were not virtual (vs. 40% of all US medical students/graduates) this difference was not significant (p = 0.09). Participants from the Midwest were statistically more likely to accept more interviews than they would have if interviews were not virtual (9/10 applicants from the Midwest vs. 36/68 applicants from remaining regions, compared using an unpaired two sample z-test. p-value = 0.0007). However, they were not statistically more likely to interview at programs that they were unlikely to rank based on location (1/10 applicants from the Midwest vs. 36/68 applicants from the remaining regions, compared using an unpaired two sample z-test. p = 0.3964).

Of the 61% of respondents who reported applying to programs and/or accepting more interviews than they would have if interviews were not virtual, 29% (14/48) reported interviewing at programs that they were unlikely to rank. Three percent of interviewees (2/78) did not report applying to more programs or accepting more interviews but did report interviewing at programs that they were unlikely to rank.

Virtual Open Houses

Virtual open houses are online presentations, often with question-and-answer sessions, hosted by residency programs for prospective applicants. Responses to questions regarding virtual open houses are shown in Figures 6. Of those that attended virtual open houses, 57% reported that attending the open house prior to interview season influenced their decision to apply to a program, 39% reported that the open house influenced their decision to accept an interview, and 39% reported that attending the open house influenced their ranking of a program. Those that stated that social media played a vital role in the 2020-2021 application season were statistically more likely to be influenced by a virtual open house (p-values 0.0001, 0.0079, and 0.0001 for applying to, accepting interviews from, and ranking programs, respectively).

Virtual Pre/Post Interview Events

Virtual pre/post interview events include any virtual event hosted by a residency program for candidates who have accepted an interview invitation. These events are typically casual virtual meetings with residents prior to or during the candidates interview day. Regarding virtual pre/post interview events, 92% of respondents reported attending a virtual pre/post interview event (Fig 7A). Sixty-three percent reported that attending a virtual dinner/happy hour influenced their ranking of a program (Fig 7B). When comparing those that stated that social media played a vital role in the application cycle to those that did not, both groups were equally likely to be influenced by virtual happy hours (p = 0.08). Regarding geographic differences, applicants from all regions were equally likely to attend a virtual pre/post dinner or happy hour (regional attendance ranged from 88%–100%).

Excluded Questions

Question 13 asked, “were you asked to supply supplemental information to your ERAS application?”, to which 21/78 replied “No”, but when asked in question #14 “If you were asked to supply supplemental information to your ERAS application, did you think this was a fair request?”, 62/78 replied “Yes” or “No”, while the remaining 16 respondents selected “The programs I applied to did not ask for supplemental information”. Given the discrepancy, we presume that 5 respondents interpreted the second question as hypothetical and responses to these two questions were excluded from further analysis.

DISCUSSION

Social Media

The medical community has had an expanding social media presence over the last decade (4). According to the Symplur data analytics website, the “#MedTwitter” hashtag has been used over three million times since October of 2012, with over two million of the tags posted after July of 2018 (5). The increased utilization of social media by the medical community is not without precedent. In 2012, the concept of Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAMed) was initiated as a social media movement by a group of innovators sharing their own open educational resources. FOAMed has since grown into “a highly networked environment that interweaves learners, teachers, scientists, and practitioners in a swirling web of content production and consumption” (6). A search of the #FOAMed hashtag reveals a vibrant community of all medical disciplines and an apparent lack of hierarchical discrimination, appealing to medical students who are given instant access to mentors and educators that are often hard to reach. FOAMed and the #MedTwitter communities have proven to be particularly valuable throughout the pandemic, a time at which traditional means of information sharing would fail to match the dynamicity of our evolving knowledge of COVID-19. The utilization of social media by medical students and physicians has likely increased over the past year, though additional research is necessary to confirm suspected trends.

Prior to the switch to virtual interviews, applicants had already been turning to social media to obtain information about programs (7,8). In an article published in September of 2020, Fick et al demonstrated that 41.6% of applicants surveyed were influenced by social media when deciding which programs to apply to (8). Our comparative results reflect the growing ubiquity of social media and the effects of the transition to virtual interviews, with the majority (71%) of our respondents using social media to learn more about a program, and 42% stating that social media played a vital role in the 2020-2021 application cycle. Even among those who did not find social media vital, the majority reported using a program's social media page(s) to learn more about the program. Our findings suggest that a program's social media presence is necessary, at the very least to showcase program culture (i.e., “goodness of fit”), a consistent key factor considered in applicant decision making (1).

Applying to More Programs, Accepting More Interviews, and Interviewing at Programs Unlikely to be Ranked

While the shift to virtual interviews had no direct effect on the cost of applications, 35% percent of our respondents reported applying to more programs than they would have if interviews were not virtual. The reasoning behind this decision is likely varying and multifactorial, including expected savings during the downstream interview process. An open letter sent on behalf of the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) suggested a maldistribution of interview invitations, with top tier applicants receiving more interviews than in the past, and middle tier applicants receiving fewer interviews than expected based on qualifications (9). The statement suggested that top tier applicants were applying to more programs than in past years. Similarly, applicants in the middle and lower third of their class may have anticipated or were advised of the maldistribution of invitations and correspondingly increased the number of applications submitted.

The shift from in-person to virtual interviews removed the limiting barriers of interview scheduling- time and cost. Expectedly, 58% of our respondents reported accepting more interviews than they would have if interviews weren't virtual. The personal decision of applicants to accept more interviews than in past years was not without effect, again evidenced by the open letter from the AAMC, which encouraged applicants to release interviews if they accepted more than needed in order to allow other students access to more interview opportunities (9).

Participants from the Midwest were statistically more likely to accept more interviews than they would have if interviews were not virtual (p-value = 0.0007). However, they were not statistically more likely to interview at programs that they were unlikely to rank based on location (p = 0.3964). The rationale for this finding likely varies from candidate to candidate, but the cost, and time saved traveling from the Midwest was likely a key factor in a midwestern candidate's decision to accept more interviews. Major US airports are clustered along the coasts. The median distance for a resident of California or New York to a major airport is 12.7 and 8.1 miles, respectively (10). Meanwhile, the median distance traveled for a resident of North Dakota and South Dakota to a major airport is 65.9 and 48.6 miles, respectively (10). Given that the midwestern candidates were no more likely than other candidates to interview at programs they were unlikely to rank, virtual interviews potentially provided more opportunities to midwestern candidates than in years past. Notably, they were given equal simplicity of access to top programs throughout the country.

Eighteen percent of our respondents reported interviewing at programs that they were unlikely to rank based on location. Unequal distribution of interviews has existed prior to the implementation of virtual interviews, with a small fraction of the applicant pool filling the majority of all available interview slots (11,12). Given the extremely competitive nature of the residency application and interview process, applicants are all but encouraged to “hoard” as many interviews as possible (12). Additionally, applicants feel pressure to perform well during interviews, as evidenced by a growing market of “mock” interview programs (13,14). Given the mitigation of cost and time barriers during the 2020-2021 interview season, it is not unreasonable to assume that some applicants might utilize interviews at undesirable programs in order to prepare for their top choice interviews. Owing to radiology's frequent use by applicants as a “backup” specialty (15), radiology program directors are especially burdened by the increase in applications and interview distribution. Applicants utilizing radiology as a backup specialty are likely highly qualified, with a resume reflective of their quest for a more competitive, top choice specialty. Given almost three-quarters of US MD seniors match to one of their top three choice programs (15), highly qualified applicants are unlikely to match into a lower-ranked backup specialty.

The process behind screening and interviewing applicants who will rank a program lowly or not at all adds a significant strain to programs with no return on time and resource investment. It further affects applicants who would have otherwise received an interview invitation but did not because interview slots were filled by this cohort. An increasing number of unmatched applicants and unfilled programs can be expected if virtual interviews continue without addressing this issue. Given that US medical students who submit between 4 and14 contiguous ranks have over 90% chance of successfully matching (1), some authors suggest a cap on the number of interviews a student can accept, preventing top tier applicants from over-interviewing (11). The use of brief secondary applications may be used to reduce applicant pool to a more management size (16). Secondary applicants may consist of brief essays or questionnaires formulated to identify applicants that display compatible interest with a program or specific geographic ties to the area not otherwise obvious on the candidate's primary application (16).

If residency interviews continue to be virtual, programs must anticipate these changes in applicant decision-making and adjust their methods and rate of interview invitations.

Virtual Open Houses

Links for residency program virtual open houses began appearing on social media at the end of spring 2020. With the urology match occurring months earlier than most other residency matches, they were at the forefront of the initiative and began seeing an average of 15 virtual open houses per week as early as June 15, 2020 (17). The @futureradres Instagram account displays over 20 diagnostic and interventional radiology virtual open house interview invitations posted in fall of 2020 (18). Research has shown that applicants find virtual open houses both helpful and necessary (19). Virtual open houses have no standard format, but usually involve a faculty introduction, discussion of training sites, hospital information, discussion of program strengths and weaknesses, and resident and/or faculty Q&A (17). During virtual open houses, programs may attempt to showcase their unique characteristics that set them apart from other programs, whether it be the program's mission, facilities, recognitions, resident-faculty dynamic, etc. The majority of our respondents reported attending a virtual open house during the 2020-2021 application cycle. Of those that attended virtual open houses, 57% reported that attending the open house prior to interview season influenced their decision to apply to a program, 39% reported that the open house influenced their decision to accept an interview, and 39% reported that attending the open house influenced their ranking of a program. Our findings suggest that virtual open houses were helpful during the virtual interview season as a means of attracting applicants and providing them with information that they would have otherwise had limited access to, particularly given the need for social distancing and cessation of in-person and away rotations. Candidates who stated that social media played a vital role in the 2020-2021 application season were statistically more likely to be influenced by a virtual open house when deciding to apply to, accept an interview from, and rank a program.

Virtual open houses removed the geographic barriers to program exposure and allowed applicants to easily obtain information about a program prior to submitting an application. While virtual open houses were the product of a socially distanced application cycle, applicants may request and expect them in years to come.

Virtual Pre/Post Interview Events

In-person residency interviews typically involve an informal event allowing for resident-applicant interactions. These events, e.g., dinners or happy hours, also allow the applicant to observe resident-resident interactions, which can provide them with useful information when determining “goodness of fit” and evaluating desirability of future colleagues. Interactions at pre-interview dinners influence an applicant's rank order list (20,21). Interview dinners have been found to enhance a candidate's perception of current residents as desirable peers to train alongside as well as enhance the candidate's perception of the training program relative to other programs (22). Attendance for the pre-interview socials is usually optional, however, candidates believe attendance is important, and failing to attend will negatively affect their application (20).

While some programs may have chosen to accept the loss of the pre/post interview reception during the 2020-2021 Match cycle, some have hosted virtual dinners/happy hours in order to provide applicants a chance to obtain the information that they would have at an in-person social with residents- candid insight to the program's culture, faculty, and academics, life outside of work, moonlighting opportunities, etc. At our institution, we hosted a nonmandatory 1-hour group “Virtual Happy Hour” meeting via the Zoom virtual meeting platform. The hour consisted of a brief game of trivia followed by casual, organic conversations between current residents and residency candidates.

Ninety two percent of our respondents reported attending a virtual pre/post interview event during this interview cycle if it was offered. Sixty-three percent of our respondents reported that the virtual dinner/happy hour influenced their ranking of a program. The virtual reception was likely to have played a role in a candidate's ranking of a program regardless of their opinion of social media's role in the 2020-2021 Match cycle.

Our study is limited by a relatively small sample size (n = 78; response rate 50%). The study was performed at one academic medical center and the surveyed population was solely applicants involved in the diagnostic and/or interventional radiology residency match, which may limit its generalizability. Participant bias may have played a role seeing as those who utilized the electronic survey may have been inherently more likely to favor social media. Additionally, although the survey was anonymous and participants were told that their response would have no effect on their ranking, applicant responses may have been influenced by the temporal relationship of the survey to their interview day. Finally, our survey was administered on a rolling basis throughout the interview season, which may mean that those who submitted the survey early may have had less experience from which to base responses.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic and the necessary changes made to The Match process during the 2020-2021 cycle likely accelerated an inevitable shift in residency program “branding” and how applicants evaluate perceived “goodness of fit”.

References

- 1.National resident matching program, data release and research committee: Results of the 2019 NRMP applicant survey by preferred specialty and applicant type. National resident matching program, Washington, DC. 2019. https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Applicant-Survey-Report-2019.pdf

- 2.Shappell E, Shakeri N, Fant A, et al. Branding and Recruitment: A Primer for Residency Program Leadership. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):249–252. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00602.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slanetz PJ, Cooke E, Jambhekar K, et al. Branding your radiology residency and fellowship programs in the COVID-19 Era. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(12):1673–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fogelson NS, Rubin ZA, Ault KA. Beyond likes and tweets: an in-depth look at the physician social media landscape. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56(3):495–508. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31829e7638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.symplur.com/healthcare-social-media-analytics/. Accessed at: March 18, 2021.

- 6.Chan TM, Stehman C, Gottlieb M, et al. A short history of free open access medical education. the past, present, and future. ATS Scholar. 2020;1(2):87–100. doi: 10.34197/ats-scholar.2020-0014p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweitzer J, Hannan A, Coren J. The role of social networking web sites in influencing residency decisions. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112:673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fick L, Palmisano K, Solik M. Residency program social media accounts and recruitment - a qualitative quality improvement project. MedEdPublish. 2020;9(1)):203. doi: 10.15694/mep.2020.000203.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whelan A. https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Applicant-Survey-Report-2019.pdf. Accessed at: December 12, 2020.

- 10.Pearson M. How far are people on average from their nearest decent-sized airport? Average Distance to Nearest Airport. 2021 https://www.mark-pearson.com/airport-distances/ Accessed atMarch 26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammoud MM, Standiford T, Carmody JB. Potential implications of COVID-19 for the 2020-2021 residency application cycle. JAMA. 2020;324(1):29–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee AH, Young P, Liao R, et al. I dream of gini: Quantifying inequality in otolaryngology residency interviews. The Laryngoscope. 2018;129(3):627–633. doi: 10.1002/lary.27521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimaldi L, Hu C, Kang P, et al. Mock interviews with video-stimulated recall to prepare medical students for residency interviews. MedEdPublish. 2018;7(3):30. doi: 10.15694/mep.2018.0000168.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donaldson K, Sakamuri S, Moore J, et al. A residency interview training program to improve medical student confidence in the residency interview. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10917. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match®. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC. 2020.https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/MM_Results_and-Data_2020-1.pdf

- 16.Soeprono TM, Pellegrino LD, Murray SB, et al. Considerations for program directors in the 2020–2021 remote resident recruitment. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44:664–668. doi: 10.1007/s40596-020-01326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang J, Key P, Deibert CM. Improving the Residency Program Virtual Open House Experience: A Survey of Urology Applicants. Urology. 2020;146:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.https://www.instagram.com/futureradres/?hl=en, Accessed 3/18/2021.

- 19.Zertuche J-P, Connors J, Scheinman A, et al. Using virtual reality as a replacement for hospital tours during residency interviews. Medical Education Online. 2020;25(1) doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1777066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlitzkus LL, Schenarts PJ, Schenarts KD. It was the night before the interview: perceptions of resident applicants about the preinterview reception. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):750–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Love JN, Howell JM, Hegarty CB, et al. Factors that influence medical student selection of an emergency medicine residency program: implications for training programs. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(4):455–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skalski JH, Dulohery MM, Kelm DJ, Ramar K. Impact of a Preinterview Dinner on Candidate Perception of a Fellowship Training Program. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):763–766. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00162.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]