Abstract

Background:

While psychedelics have been shown to improve psycho-spiritual well-being, the underlying elements of this change are not well-characterized. The NIH-HEALS posits that psycho-social-spiritual change occurs through the factors of Connection, Reflection & Introspection, and Trust & Acceptance. This study aimed to evaluate the changes in NIH-HEALS scores in a cancer population with major depressive disorder undergoing psilocybin-assisted therapy.

Methods:

In this Phase II, single-center, open label trial, 30 cancer patients with major depressive disorder received a fixed dose of 25 mg of psilocybin. Participants underwent group preparation sessions, simultaneous psilocybin treatment administered in separate rooms, and group integration sessions, along with individual care. The NIH-HEALS, a self-administered, 35-item, measure of psycho-social spiritual healing was completed at baseline and post-treatment at day 1, week 1, week 3, and week 8 following psilocybin therapy.

Results:

NIH-HEALS scores, representing psycho-social-spiritual wellbeing, improved in response to psilocybin treatment (p<0.001). All three factors of the NIH-HEALS (Connection, Reflection & Introspection, and Trust & Acceptance) demonstrated positive change by 12.7%, 7.7%, and 22.4%, respectively. These effects were apparent at all study time points and were sustained up to the last study interval at 8 weeks (p<0.001).

Limitations:

The study lacks a control group, relies on a self-report measure, and uses a relatively small sample size with limited diversity that restricts generalizability.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that psilocybin-assisted therapy facilitates psycho-social-spiritual growth as measured by the NIH-HEALS and its three factors. This supports the factors of Connection, Reflection & Introspection, and Trust & Acceptance as important elements for psycho-social-spiritual healing in cancer patients, and validates the use of the NIH-HEALS within psychedelic research.

Keywords: psilocybin, cancer, psycho-spiritual, healing, NIH-HEALS

Introduction

A cancer diagnosis can have a devastating effect on physical, psychological, and spiritual well-being (Niedzwiedz et al., 2019; Zare et al., 2019). While extensive focus has been placed on mitigating the physiological impact, recent efforts have aimed to uncover the psycho-spiritual needs of cancer patients (Hatamipour et al., 2015; Astrow et al., 2018). Many cancer patients experience clinical depression and anxiety (Zabora et al., 2001; Mitchell et al., 2011), a debilitating fear of dying, disconnectedness, lack of control, and loss of hope (Coward & Kahn, 2004; Moreno & Stanton, 2013). Yet, traditional pharmacotherapeutics have mixed and limited efficacy in treating cancer-related distress (Li et al., 2012).

Psychedelic therapies such as psilocybin (Griffiths et al., 2016) are among novel therapeutic approaches that have found a renewed relevance in recent years. Throughout history, Indigenous tribes have utilized plant-based hallucinogenic substances for their healing properties. These ceremonies promoted mystical experiences, open-mindedness, and connection with nature and the divine (Carod-Artel, 2015; Nichols, 2020). During the 1960s-1970s, psychedelic research in the United States documented profound effects on psychological health, quality of life, and pain in cancer patients (Kast & Collins, 1964; Kast, 1966; Pahnke, 1969).However, safety concerns were raised in response to widespread non-medical use, and clinical research was halted with the Controlled Substance Act. Since then, conditions for safe administration, proper set and setting, and a code of ethics for psychedelic use have been established (Johnson et al., 2008; Mithoefer, 2017). In more recent clinical trials, psilocybin was found to promote significant and substantial improvements in cancer-related depression, anxiety, existential distress, and orientation towards death (Grob et al., 2011; Griffiths et al., 2016, Ross et al., 2016). While the effects are clear, the mechanistic underpinnings of psychedelic-mediated psycho-spiritual change in cancer patients are less understood.

A recently validated measure, the NIH-HEALS, has been developed based on interviews with patients who experienced positive psychological, social, and spiritual change after being diagnosed with severe and/or life-threatening diseases. Two hundred patients, 80% of whom had diagnoses of cancer, were recruited from the NIH Clinical Center and participated in the validation of the NIH-HEALS. Results showed the measure to have high internal consistency, split-half reliability, and convergent and divergent validity (Ameli et al., 2018). Factor analysis of the NIH-HEALS yielded three primary elements instrumental in psycho-social-spiritual healing: (1) Connection: a sense of interconnectedness; religious, spiritual and interpersonal connectedness; level of connection to a higher power, community, and family; (2) Reflection & Introspection: a sense of meaning, purpose, and gratitude, experience of joy in nature, use of activities that connect mind and body, present moment orientation, and an awareness about the fragility of life; (3) Trust & Acceptance: the ability to let go of resistance, to feel resolved and at peace with one’s circumstances, and to trust that caregivers, friends and family will respond to needs as they arise. These factors are consistent with cancer literature, as higher well-being in cancer patients has been linked to one’s connectedness with others (Lin & Bauer-Wu, 2003), sense of life-meaning (Lin & Bauer-Wu, 2003; Sleight et al., 2021), and acceptance of the diagnosis (Secinti et al., 2019).

The factors of connection, reflection/introspection, and trust/acceptance are also influenced by psychedelic therapy. Subjective reports indicate that psychedelic therapy can improve one’s sense of connection, as participants have described experiences of reduced self-other boundaries (Smigielski et al., 2020), increased nature relatedness (Kettner et al., 2019), and a profound sense of oneness with all (Watts et al., 2017). Psychedelic therapy is also thought to promote introspection by leading one on an exploration of the unconscious, to discover all disavowed aspects of the self and begin a process of attachment repair (Vaid & Walker, 2022)., Lastly, psychedelics may encourage acceptance, as attempts to exert control over a challenging psychedelic experience typically fail while adopting an allowing attitude and letting go provides the intended relief (Wolff et al., 2020). This encounter teaches one to move towards suffering rather than away, transforming habitual avoidance into a growth-inclined attitude (Watts et al., 2017).

We hypothesize that the elements of Connection, Reflection & Introspection, and Trust & Acceptance underlie the psycho-social-spiritual improvements evidenced in psilocybin therapy. Thus, the present study aims to evaluate the changes in NIH-HEALS scores in a cancer population with major depressive disorder following psilocybin-assisted therapy.

Methods

Study Design

This was a Phase II, single-center, fixed dose, open label trial of psilocybin-assisted group therapy in cancer patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Psychotherapeutic care was provided before, during, and after psilocybin administration to cohorts of 3–4 participants. Supportive therapy included individual and group preparation sessions, simultaneous administration of psilocybin to the cohort, and individual and group integration sessions. This study (NCT04593563) took place in a cancer center in Rockville, Maryland. It was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (IRB), sponsored by Maryland Oncology Hematology, PA., and funded by COMPASS Pathways Ltd., the psilocybin manufacturer.

Participants

Thirty (30) participants were recruited during an 8-month period at the study site and through referrals from specialized psychiatric and oncology services using convenience sampling. Written consent was obtained from each participant prior to the study. Inclusion criteria were: 1) aged ≥ 18 years, 2) Major Depressive Disorder single episode or recurrent without psychotic features according to the DSM-5, 3) Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) score ≥ 18 at baseline, and 4) malignant neoplasm based on ICD-10 codes C00-C97. Exclusion criteria were adapted from current standards for psilocybin safety profiles, which include current or past history of psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders borderline personality disorder, or significant suicide risk. Patients tapered psychiatric medications per standard psychedelic research practices in order to participate safely (Johnson et al., 2008). No cancer-related procedures were performed during the study period, but oral cancer medications were continued.

Study Procedure

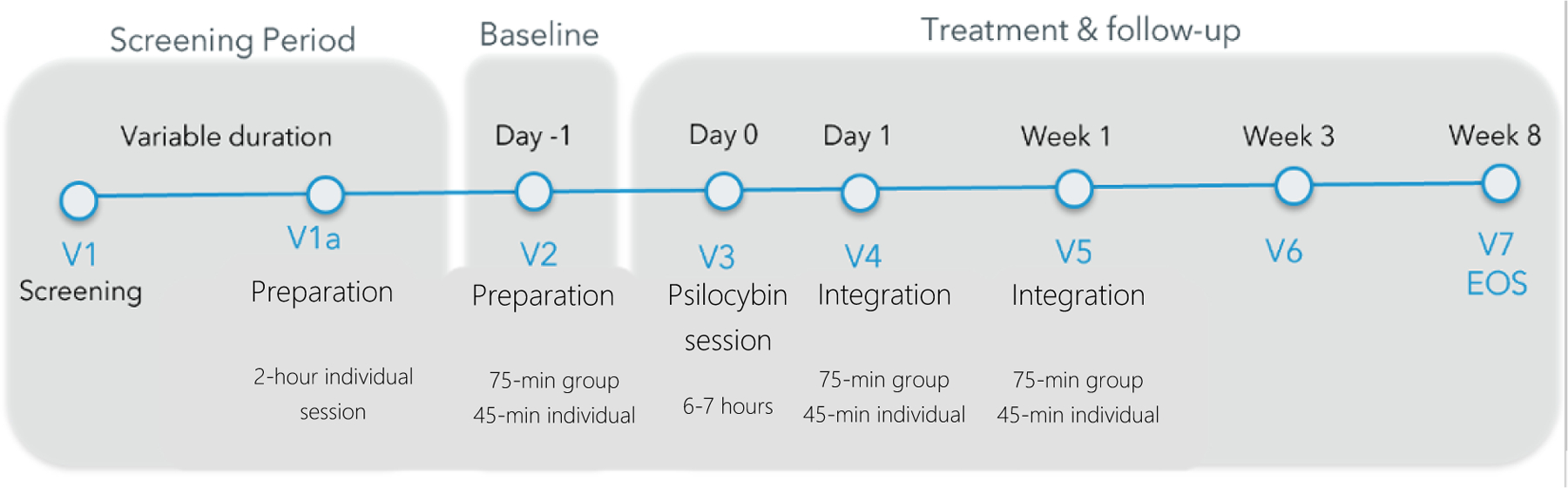

Cohorts of 3–4 participants completed screening, baseline assessment, treatment, and follow-ups with a total of 8 visits during the 8-week study period (Figure 1). During Visit 1, participants signed an informed consent form and were assessed for their eligibility with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Version 7.0.2 (MINI 7.0.2) (Sheehan, 1998), the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) (Hamilton, 1960), and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (Posner et al., 2008). The following information was also obtained during Visit 1: medical history, physical examination, medication use, vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG), and blood and urine samples. Eligible participants then entered the screening period and were further evaluated with the Euro Quality of Life- 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L), the DSM-5 Anxious Distress Specifier (DADSI), the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-SR), and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Clinicians were all licensed with master’s or doctorate degrees and supervised by an experienced psychedelic therapy informed senior clinician.

Figure 1. Study schematic outline.

Following the screening phase, participants went through two preparation sessions, psilocybin therapy, and two integration sessions. Safety, efficacy, and exploratory measures were administered at V2 (Baseline), V4 (Day 1), V5 (Week 1), V6 (Week 3), and V7 (Week 8).

Abbreviations: EoS = End of Study; V = Visit

After passing the screening phase, participants met with their assigned therapist for their first preparatory session (V1a). This 2-hour visit was designed to impart information regarding the psilocybin treatment, introduce coping strategies such as breathing exercises, and establish a therapeutic alliance. Visit 2 (Baseline), occurred one day prior to the psilocybin treatment. This visit included the administration of outcome measures and a two-part therapeutic session, with both group and individual components. The group component was guided by a lead therapist, who disseminated psychoeducational material and encouraged interaction among participants. The goal of the group preparation session was to support the development of a relationship among the group members, treatment team, and the designated therapists. Participants also met individually with their assigned therapist to address individual concerns, set intentions for the session, and practice techniques for managing anxiety and supporting experiential engagement.

At Visit 3, participants were administered 25 mg of psilocybin alongside their cohort in individual rooms, supported by their assigned therapist. The therapeutic approach was non-directive and entailed the use of eyeshades and a music program to promote an inner-directed experience. The dominant mode of therapy was active listening and presence. Therapeutic goals were to ensure psychological safety, to maintain each participants attention on the present moment, and to encourage processing of potentially challenging emotional states. Adverse events (AEs) were recorded during the session.

Visits 4 and 5 occurred in a similar two-part therapeutic approach, with group and individual components. The aim of these sessions was to facilitate integration of the psychological material accessed during the psilocybin therapy by exploring these experiences, their significance and meaning, and their impact on participants’ lives. Consistent with self/inner-directed inquiry, therapists did not make interpretations, influence understanding, give advice, or suggest solutions during integration sessions.

The NIH-HEALS was administered at four time points: baseline (V2), week 1 (V5), week 3 (V6), and week 8 (V7) post-treatment.

NIH-HEALS

National Institute of Health, Healing Experiences in All Life Stressors (NIH-HEALS), is a psycho-social-spiritual measure of healing when faced with challenges (Table 1) (Ameli et al., 2018). The NIH-HEALS has strong convergent (r = 0.64, p < 0.0001) and divergent validity (r = −0.34, p < 0.0001). There are 35-items scored using a 5-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 35 to 175. It has three factors, namely Connection (e.g., “my situation strengthened my connection to a higher power”), Reflection & Introspection (e.g., “working through thoughts about the possibility of dying brought meaning to my life”), and Trust & Acceptance (e.g., “I accept things that I cannot change”) (Ameli et al., 2018). It is important to note that the NIH-HEALS three factors are not discrete constructs. Rather, they are related concepts that delineate psycho-social-spiritual elements that could contribute to the experience of healing.

Table 1.

Three-Factor, 35-item NIH-HEALS Measure of Psycho-Social-Spiritual Wellbeing

| Connection | Reflection & Introspection | Trust & Acceptance |

|---|---|---|

| 3. Connection with a higher power is important to me | 4. I gain awareness from self-reflection | 1. I am content with my life |

| 12. I survived difficult circumstances because of a higher power | 5. I enjoy activities that involve both the mind & body | 2. I have a sense of purpose in my life |

| 13. My situation strengthened my connection to a higher power | 9. Working through thoughts about dying brought meaning to my life | 6. I feel isolated |

| 14. My religious beliefs help me feel calm when faced with difficult circumstances | 10. Difficult circumstances in my life have increased my compassion towards others | 7. I feel calm even though I am not in control of my situation |

| 15. My personal religious practice is important to me | 11. I want to make the most out of life | 8. I accept things I cannot change |

| 16. My participation in religious community is an important aspect of my life | 19. Doing something I am passionate about gives me purpose during difficult times | 23. I am not getting the support I need |

| 17. I get support from my religious community | 20. I find meaning in helping others | 24. I am confident that my medical caregivers will respond to my needs |

| 18. My religious beliefs give me hope | 26. I seek more of a connection in my relationships | 25. My friends provide the support I need during |

| difficult times | ||

| 21. Connection with family has become by highest priority | 27. I take more time to be in the moment | 28. My experience with multiple losses has made it hard to be hopeful during difficult times |

| 22. Support from family lifts my spirits, which gives me hope during difficult times in my life | 29. Working through my own grief brings meaning to my life | 30. I have a sense of peace in my life |

| 31. I have an increased sense of gratitude | 34. Life challenges interfere with activities that are important to me | |

| 32. Being surrounded by nature is meaningful | ||

| 33. Creative arts brings peace to my life | ||

| 35. Life challenges raised my desire to be positive |

Statistical Analysis

Data are described using frequency (percentage) for categorical data and mean (SD) for continuous data and were assessed for distributional (normality) assumptions. Mixed models for repeated measures were used to analyze NIH-HEALS scores (outcome, dependent variable, continuous data) at each visit over time (week 1, week 3, week 8). These models adjusted for baseline NIH-HEALS score, as is required in repeated measures analysis. In addition, models were adjusted for potential confounding effects of age (continuous) and gender (categorical). Post-hoc comparisons adjusted for multiple comparisons by Dunnet’s method with baseline as the referent comparison. Data were analyzed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics

Demographic information describing the sample is presented in Table 2. The mean age of participants was 56 years (SD 12). Participants did not identify outside of the gender binary, with 30% identifying as male and 70% as female. The sample was predominantly Caucasian (80%), married (67%), and employed (83%). Most participants (70%) had undergone more than 1 line of cancer therapy. At baseline, participants had a mean HAMD score of 25.4 and mean QIDS score of 12.3, both of which indicate moderate to severe depression. Half of the sample (50%) reported previous antidepressant usage. Patients who had undergone curative treatment for cancer as well as those with advanced metastatic disease were included. Cancer prognosis varied within the sample-nearly half (47%) were diagnosed with curable cancer, while the other half (53%) had non-curable, metastatic cancer.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants with Cancer

| Characteristic | Categories | % (n=30) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, in years: mean (SD) | Range 30 – 78 | 56.1 (12.4) |

| Gender | Female | 70.0% |

| Male | 30.0% | |

| Ethnicity/Race | African American/Black | 10.0% |

| Asian, Asian American, Pacific | 6.7% | |

| Islander | 80.0% | |

| Caucasian | 3.30% | |

| Hispanic, Latinx | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 66.7% |

| Divorced/Separated | 16.7% | |

| Never Married | 16.7% | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 83.3% |

| Retired | 13.3% | |

| Unemployed | 3.33% | |

| Number of Depressive | 3 or less | 30.0% |

| Episodes | More than 3 | 40.0% |

| Unknown | 30.0% | |

| Baseline Depression Severity: | HAMD | 25.4 |

| mean (SD) | QIDS-SR | 12.3 |

| Prior Antidepressant Use | Yes | 50.0% |

| No | 36.7% | |

| Unknown | 13.3% | |

| Cancer Prognosis | Non-curable | 53.3% |

| Curable | 46.7% |

Adverse Events (AEs)

The reported adverse events related to psilocybin therapy were generally mild or expected, and included headache (80%), nausea (40%), tearfulness (27%), anxiety (23%), euphoria (23%), fatigue (23%), and mild impairment of psychomotor functioning (10%). These effects resolved at the conclusion of the psilocybin treatment session prior to discharge. There were no notable laboratory changes, ECG abnormalities, or suicidality.

Psycho-Social-Spiritual Wellbeing

NIH-HEALS scores, representing the extent to which one experiences psycho-social-spiritual healing, improved in response to psilocybin treatment (Table 3). All three factors of the NIH-HEALS (Connection, Reflection & Introspection, and Trust & Acceptance), demonstrated positive change. These effects were apparent one day after psilocybin treatment and were sustained up to the last study interval at 8 weeks.

Table 3.

NIH-HEALS Factor and Cumulative Total Scores over Time

| Visit | n | Score Mean (SD) | Magnitude of Effect Mean Difference (95% CI)1 |

P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connection Factor | ||||

| Baseline | 30 | 30.8 (9.4) | ||

| Week 1 | 30 | 34.3 (9.1) | 3.4 (1.3–5.3) | 0.002 |

| Week 3 | 30 | 33.8 (89.0) | 2.9 (0.7–4.9) | 0.012 |

| Week 8 | 3 | 34.7 (9.3) | 3.9 (1.4–5.9) | 0.003 |

| Reflection & Introspection Factor | ||||

| Baseline | 30 | 55.7 (6.8) | ||

| Week 1 | 30 | 59.6 (6.8) | 3.9 (2.1–6.2) | <0.001 |

| Week 3 | 30 | 60.4 (6.4) | 4.7 (3.2–7.3) | <0.001 |

| Week 8 | 30 | 60.0 (7.9) | 4.3 (2.5–7.3) | <0.001 |

| Trust & Acceptance Factor | ||||

| Baseline | 30 | 32.6 (8.0) | ||

| Week 1 | 30 | 39.3 (8.9) | 6.7 (3.9–10.3) | <0.001 |

| Week 3 | 30 | 39.7 (8.7) | 7.1 (4.3–10.9) | <0.001 |

| Week 8 | 30 | 39.9 (10.7) | 7.3 (4.2–11.7) | <0.001 |

| Total Score | ||||

| Baseline | 30 | 119.1 (19.4) | ||

| Week 1 | 30 | 133.1 (19.9) | 14.4 (8.5–20.3) | <0.001 |

| Week 3 | 30 | 133.8 (20.3) | 15.5 (8.9–20.9) | <0.001 |

| Week 8 | 30 | 134.6 (23.7) | 16.4 (9.1–23.8) | <0.001 |

From a repeated measures mixed model analyses adjusting for baseline, age, and gender, where follow-up visits were compared to baseline. P-values are corrected for multiple comparisons.

The Connection factor, measuring connection to a higher power and to loved ones, increased by 12.7% on average by week 8 (p = 0.003) the end of the study. Scores on the Reflection & Introspection factor, measuring a sense of meaning, purpose, and gratitude, experience of joy in nature, use of activities that connect mind and body, present moment orientation, and an awareness about the fragility of life, rose by 7.7% by week 8 (p<0.001). Similarly, scores on the Trust & Acceptance factor, measuring the ability to let go of resistance, to feel resolved and at peace with one’s circumstances, and to trust that caregivers, friends, and family will respond to needs as they arise, increased by 22.4% by week 8 (p<0.001). Cumulatively, this totaled to an average of a 16.4-point increase in the NIH-HEALS total scores (p<0.001; Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, cancer patients with depression experienced marked improvements in psycho-social-spiritual wellbeing following psilocybin-assisted therapy, as assessed by the NIH-HEALS. These improvements occurred within the domains of Connection, Reflection & Introspection, and Trust & Acceptance, and were sustained for up to 8 weeks post-dosing. Thus, the results of this study demonstrate that the NIH-HEALS was a useful measure in the context of psychedelic research, and point to a potential mechanism for the psycho-spiritual healing evidenced in cancer patients undergoing psilocybin-assisted therapy.

The results are corroborated by prior psilocybin research, which documented similar changes in cancer patients. Griffiths et al. (2016) utilized the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy- Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-sp) to measure changes in the spiritual dimension of quality life across the domains of meaning, peace, and faith, and found improvements up to 6 months post psilocybin treatment. Ross et al. (2016) also found psilocybin therapy to positively influence spiritual well-being in a cancer patient population using FACIT-swb, a modified version with a combined meaning/purpose factor. The NIH-HEALS and its factors are significantly correlated with FACIT-Sp factors (Ameli et al., 2018). Further, the NIH-HEALS offers an assessment of Trust & Acceptance as a component of the healing experience in addition to faith, meaning, and peace.

With a better understanding of the underlying psycho-social spiritual changes, psychedelic-assisted therapies can be tailored to strengthen well-being further during the intervention. Because data suggests that Connection, Reflection & Introspection, and Trust & Acceptance are important elements for psycho-social-spiritual wellbeing, additional focus can be placed on enhancing the development of these factors during therapeutic sessions. For example, therapists leading preparation and integration sessions can emphasize themes of connection, teach mindfulness skills, promote acceptance of life’s circumstances, and encourage awareness of the fragility of life awareness (Rodin et al., 2018). This existential awareness, so called “double awareness” on life and death, vitalizes people to live more fully, while also preparing them for the inevitable transition (Rodin et al., 2018; Holland & Breitbart, 1998).

The renewed interest in psilocybin therapy represents a paradigm shift towards a more holistic approach to treatment. There is an underlying assumption that the psyche holds the tools for its own healing, with psychedelics acting as its catalyst (Grof, 2003; Grinspoon & Doblin, 2008; Mithoefer, 2017). This therapy also addresses the complexity of the whole person, including the mind, body, and spirit (Benor, 2017). While the mind and body have traditionally been regarded as important dimensions, it is noteworthy that the medical field is evolving to incorporate spiritual wellbeing into its definition of health (WHOQOL, 1995). Spirituality was found to be associated with quality of life to the same degree as physical well-being (Brady et al., 1999). Thus, the inclusion of this domain of life in treatment aligns with the current knowledge base on the factors contributing to wellbeing, healing, and quality of life.

Addressing psycho-spirituality might be particularly salient in the cancer patient population, whose diagnoses have radically restructured their lives. In order to experience meaning in life, humans need to comprehend the world around them (coherence), find direction for their actions (purpose), and find worth in their lives (significance) (Park & AI, 2006; Martela & Steger, 2016). Diagnosis of severe and/or life-threatening disease can shatter one’s sense of coherence, basic safety, purpose, and significance (Ameli et al., 2018). However, those who are able to reformulate the world around them and their place within it can emerge on a growth trajectory, with a greater sense of wholeness than before their diagnosis (Tedeschi & Calhoun 1996; Tedeschi et al., 2017; Ameli et al., 2018). Psilocybin is one tool that has the potential to facilitate this transformation in patients by encouraging acceptance of their disease, increasing trust in caregivers, expanding their perspective of self, and deepening a sense of connection to self, others, nature, or a higher power.

The present study was limited by the lack of a control group, a potential for social desirability bias in responding to NIH-HEALS items, and a smaller sample size. In addition, the participants were predominantly Caucasian, female, and employed. These limitations should be considered in terms of the generalizability of the study results. Future studies may aim to reduce these limitations by including a control arm and repeating the treatment in a larger, more diverse sample.

In summary, these findings bring a deeper understanding to the psycho-social-spiritual changes that emerge from psilocybin-assisted therapy, and will hopefully advance the psychedelic field.

Highlights.

NIH-HEALS scores, representing psycho-social-spiritual healing, improved in response to psilocybin treatment.

All three factors of the NIH-HEALS (connection, reflection & introspection, and trust & acceptance) demonstrated positive change.

These effects were apparent at all study time points and were sustained up to the last study interval at 8 weeks

Acknowledgments:

Declared none.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors confirm that the article content has no conflict of interest

References:

- Ameli R, Sinaii N, Luna MJ, Cheringal J, Gril B, & Berger A (2018). The National Institutes of Health measure of Healing Experience of All Life Stressors (NIH-HEALS): Factor analysis and validation. PloS one, 13(12), e0207820. 10.1371/journal.pone.0207820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrow AB, Kwok G, Sharma RK, Fromer N, & Sulmasy DP (2018). Spiritual Needs and Perception of Quality of Care and Satisfaction With Care in Hematology/Medical Oncology Patients: A Multicultural Assessment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(1), 56–64.e1. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benor D (2017). The Definition of Healing Depends on How One Defines Health. Explore (New York, N.Y.), 13(4), 259–260. 10.1016/j.explore.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, & Cella D (1999). A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psycho-Oncology, 8(5), 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carod-Artal FJ (2015). Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures. Neurología (English Edition), 30(1), 42–49. 10.1016/j.nrleng.2011.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward DD, & Kahn DL (2004). Resolution of spiritual disequilibrium by women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncology nursing forum, 31(2), E24–E31. 10.1188/04.ONF.E24-E31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, Cosimano MP, & Klinedinst MA (2016). Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 30(12), 1181–1197. 10.1177/0269881116675513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinspoon L, & Bakalar JB (1986). Can drugs be used to enhance the psychotherapeutic process? American Journal of Psychotherapy, 40(3), 393–404. 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1986.40.3.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinspoon L, Doblin R (2001) Psychedelics as catalysts in insight-oriented psychotherapy. Social Research, 68; 677–695. [Google Scholar]

- Grob CS, Danforth AL, Chopra GS, Hagerty M, McKay CR, Halberstadt AL, & Greer GR (2011). Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(1), 71–78. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grof S (2003). Implications of modern consciousness research for psychology: Holotropic experiences and their healing and heuristic potential. The Humanistic Psychologist, 31(2–3), 50–85. 10.1080/08873267.2003.9986926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23, 56–62. 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartogsohn I (2018). The Meaning-Enhancing Properties of Psychedelics and Their Mediator Role in Psychedelic Therapy, Spirituality, and Creativity. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 129. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatamipour K, Rassouli M, Yaghmaie F, Zendedel K, & Majd HA (2015). Spiritual Needs of Cancer Patients: A Qualitative Study. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 21(1), 61–67. 10.4103/0973-1075.150190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifets BD, & Malenka RC (2016). MDMA as a Probe and Treatment for Social Behaviors. Cell, 166(2), 269–272. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC & Breitbart W (1998). Psycho-oncology Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Richards WA, & Griffiths RR (2008). Human Hallucinogen Research: Guidelines for Safety. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 22(6), 603–620. 10.1177/0269881108093587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW (2021). Consciousness, Religion, and Gurus: Pitfalls of Psychedelic Medicine. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, 4(2), 578–581. 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kast E (1966). LSD and the dying patient. The Chicago Medical School quarterly, 26(2), 80–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kast EC, & Collins VJ (1964). Study of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide as an Analgesic Agent. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 43(3), 285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney M A place of healing: working with suffering in living and dying New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kettner H, Gandy S, Haijen ECHM, & Carhart-Harris RL (2019). From Egoism to Ecoism: Psychedelics Increase Nature Relatedness in a State-Mediated and Context-Dependent Manner. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5147. 10.3390/ijerph16245147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Frye MA, & Shelton RC (2012). Review of Pharmacological Treatment in Mood Disorders and Future Directions for Drug Development. Neuropsychopharmacology, 37(1), 77–101. 10.1038/npp.2011.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H-R, & Bauer-Wu SM (2003). Psycho-spiritual well-being in patients with advanced cancer: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(1), 69–80. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martela F, & Steger MF (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. 10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, & Meader N (2011). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. The Lancet Oncology, 12(2), 160–174. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mithoefer M, Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). A Manual for MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Version 8.1 2017.

- Moreno PI, & Stanton AL (2013). Personal growth during the experience of advanced cancer: a systematic review. Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass.), 19(5), 421–430. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3182a5bbe7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols DE (2020). Psilocybin: From ancient magic to modern medicine. The Journal of Antibiotics, 73(10), 679–686. 10.1038/s41429-020-0311-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedz CL, Knifton L, Robb KA, Katikireddi SV, & Smith DJ (2019). Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer, 19(1), 943. 10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin G, Lo C, Rydall A, Shnall J, Malfitano C, Chiu A, Panday T, Watt S, An E, Nissim R, Li M, Zimmermann C, & Hales S (2018). Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM): A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Psychological Intervention for Patients With Advanced Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36(23), 2422–2432. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P, & Schmidt BL (2016). Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 30(12), 1165–1180. 10.1177/0269881116675512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahnke WN (1969). Psychedelic drugs and mystical experience. International psychiatry clinics, 5(4), 149–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K et al. , (2011). The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings From Three Multisite Studies With Adolescents and Adults. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preller KH, Herdener M, Pokorny T, Planzer A, Kraehenmann R, Stämpfli P, Liechti ME, Seifritz E, & Vollenweider FX (2017). The Fabric of Meaning and Subjective Effects in LSD-Induced States Depend on Serotonin 2A Receptor Activation. Current biology : CB, 27(3), 451–457. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secinti E, Tometich DB, Johns SA, & Mosher CE (2019). The relationship between acceptance of cancer and distress: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 71, 27–38. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleight AG, Boyd P, Klein WMP, & Jensen RE (2021). Spiritual peace and life meaning may buffer the effect of anxiety on physical well-being in newly diagnosed cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 30(1), 52–58. 10.1002/pon.5533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smigielski L, Kometer M, Scheidegger M, Stress C, Preller KH, Koenig T, & Vollenweider FX (2020). P300-mediated modulations in self–other processing under psychedelic psilocybin are related to connectedness and changed meaning: A window into the self–other overlap. Human Brain Mapping, 41(17), 4982–4996. 10.1002/hbm.25174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaid G, & Walker B (2022). Psychedelic Psychotherapy: Building Wholeness Through Connection. Global advances in health and medicine, 11, 2164957X221081113. 10.1177/2164957X221081113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts R, Day C, Krzanowski J, Nutt D, & Carhart-Harris R (2017). Patients’ Accounts of Increased “Connectedness” and “Acceptance” After Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(5), 520–564. 10.1177/0022167817709585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, Evens R, Mertens LJ, Koslowski M, Betzler F, Gründer G, & Jungaberle H (2020). Learning to Let Go: A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of How Psychedelic Therapy Promotes Acceptance. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, & Piantadosi S (2001). The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-oncology, 10(1), 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zare A, Bahia NJ, Eidy F, Adib N, & Sedighe F (2019). The relationship between spiritual well-being, mental health, and quality of life in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(5), 1701–1705. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_131_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]