Abstract

The importance of the One Health concept in attempting to deal with the increasing levels of multidrug-resistant bacteria in both human and animal health is a challenge for the scientific community, policymakers, and the industry. The discovery of the plasmid-borne mobile colistin resistance (mcr) in 2015 poses a significant threat because of the ability of these plasmids to move between different bacterial species through horizontal gene transfer. In light of these findings, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that countries implement surveillance strategies to detect the presence of plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant microorganisms and take suitable measures to control and prevent their dissemination. Seven years later, ten different variants of the mcr gene (mcr-1 to mcr-10) have been detected worldwide in bacteria isolated from humans, animals, foods, the environment, and farms. However, the possible transmission mechanisms of the mcr gene among isolates from different geographical origins and sources are largely unknown. This article presents an analysis of whole-genome sequences of Escherichia coli that harbor mcr-1 gene from different origins (human, animal, food, or environment) and geographical location, to identify specific patterns related to virulence genes, plasmid content and antibiotic resistance genes, as well as their phylogeny and their distribution with their origin. In general, E. coli isolates that harbor mcr-1 showed a wide plethora of ARGs. Regarding the plasmid content, the highest concentration of plasmids was found in animal samples. In turn, Asia was the continent that led with the largest diversity and occurrence of these plasmids. Finally, about virulence genes, terC, gad, and traT represent the most frequent virulence genes detected. These findings highlight the relevance of analyzing the environmental settings as an integrative part of the surveillance programs to understand the origins and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance.

Keywords: One Health, antibiotic resistance genes, Escherichia coli, whole-genome sequencing, colistin resistance, mcr-1

Introduction

Over the last two decades, the evolution and dissemination of new antibiotic resistance determinants has led to one of the most critical health scenarios worldwide. According to the United Nations and the World Bank, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) will cause, in the worst scenario, 10 million deaths every year and a loss of 3.8 percent of the annual global gross domestic product (GDP) by 2050 (World Bank, 2017; IACG, 2019). A recently published systematic analysis on the worldwide burden of bacterial AMR estimated that in 2019 there were nearly 5 million deaths associated with AMR in that year alone, and 1.3 million deaths were directly attributable to bacterial AMR (Murray et al., 2022). The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study (GBD) estimates that in 2019 out of 13.7 million deaths, the leading pathogen responsible for global deaths was Staphylococcus aureus, followed closely by Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae (GBD, 2019, Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators, 2022).

Although bacterial AMR represents a threat to humankind, pharmaceutical research and development have failed to identify and deploy new antibiotics that can reduce and minimize this substantial danger (Tacconelli et al., 2017). In this context, the dependence on antibiotics of last resort to treat the increasing levels of multidrug-resistant bacteria in both human and animal health is a challenge for the scientific community, policymakers, and the industry, and hence the importance of the One Health concept in attempting to deal with this global problem (Mendelson et al., 2018). Colistin (polymyxin E) is considered one of the crucial last-resort antibiotics and is regarded as an essential option for use against infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (Falagas et al., 2005; Kaye et al., 2016). Unfortunately, colistin is commonly used in the animal world for treating infections and as a growth promoter in animal feeds. These practices have contributed to widescale and rapid global resistance to this antibiotic (Elbediwi et al., 2019).

Traditionally, colistin resistance mechanisms were triggered by chromosomal mutations (Kim et al., 2019). However, the discovery of the plasmid-borne mobile colistin resistance mechanism in 2015, called mcr, poses a significant threat because of the ability of these plasmids to move between different bacterial species through horizontal gene transfer (Liu et al., 2015). In light of these findings, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that countries implement surveillance strategies to detect the presence of plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant microorganisms and take suitable measures to control and prevent their dissemination (PAHO/WHO, 2016).

Since 2015, the mcr gene has been reported in the chromosomal or plasmid content in some bacterial species, mainly the Enterobacterales (Zhang et al., 2021). Nowadays, the mcr gene is most frequently harbored with E. coli (Forde et al., 2018). At present, ten different variants of the mcr gene (mcr-1 to mcr-10) have been detected worldwide in bacteria isolated from humans, animals, foods, the environment, and farms (Dadashi et al., 2021; Hussein et al., 2021). However, the possible transmission mechanisms of the mcr gene among isolates from different geographical origins and sources are largely unknown.

The democratization of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) techniques and the generation of bioinformatic platforms that allow a deep characterization of pathogens can potentially transform epidemiological surveillance and disease control systems worldwide (NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Genomic Surveillance of AMR, 2020; Ferdinand et al., 2021; Kovac et al., 2021). Using these new technologies, the aim of this study was to re-analyze mcr-1 harboring E. coli WGS sequences submitted to the greater public genomic databases [such as the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA)] to identify specific patterns related to virulence genes, plasmid content and antibiotic resistance genes, as well as their phylogeny and their distribution with their origin (human, animal, food or environment) and geographical location.

Materials and methods

Sequences

One hundred and twenty-three WGS sequences of mcr-1 harboring E. coli were obtained from NCBI and ENA databases from 26 countries from four continents (Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Europe). The description of the sequences (years, country of origin, and NCBI/ENA number) are included in Supplementary Table S1. Briefly, 42 sequences were retrieved from the Americas, 32 from Europe, 10 from South and East Asia, 15 from Western Asia, 22 from Southeast Asia, and two from Africa. According to their origin, 55 were from animals, 47 were from humans, 7 were from feeds, and 14 were from environmental samples. In addition, the draft genome assembly quality was evaluated using CheckM v1.0.18.

Bioinformatic analyses

Draft genomes were analyzed using the tools from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology of the Technical University of Denmark. Multilocus sequence types (MLSTs) were determined using MLST v2.0 (Larsen et al., 2012). The presence of plasmids was identified using PlasmidFinder (Carattoli and Hasman, 2020). The prediction of bacterial pathogenicity was evaluated using PathogenFinder v1.1 (Cosentino et al., 2013). The detection of E. coli virulence genes was carried out using VirulenceFinder v2.0 (Tetzschner et al., 2020). The identification of acquired genes and/or chromosomal mutations mediating antimicrobial resistance was done using ResFinder 4.1 (Bortolaia et al., 2020). The core-genome multilocus sequence typing phylogeny was carried out using the Galaxy Sciensano platform (Bogaerts et al., 2019). The obtained Newick file was analyzed and annotated using iTOL platform (Letunic and Bork, 2021).

Statistical analysis

The distribution of the genotypes between hosts and location was calculated using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s multiple-comparison test was performed post hoc for pairwise comparisons between groups, and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. The data analysis for this paper was generated using the Real Statistics Resource Pack software (Release 7.6). Copyright (2013–2021) Charles Zaiontz.1

Ethics statement

This work does not involve the use of human subjects or animal experiments.

Results and discussion

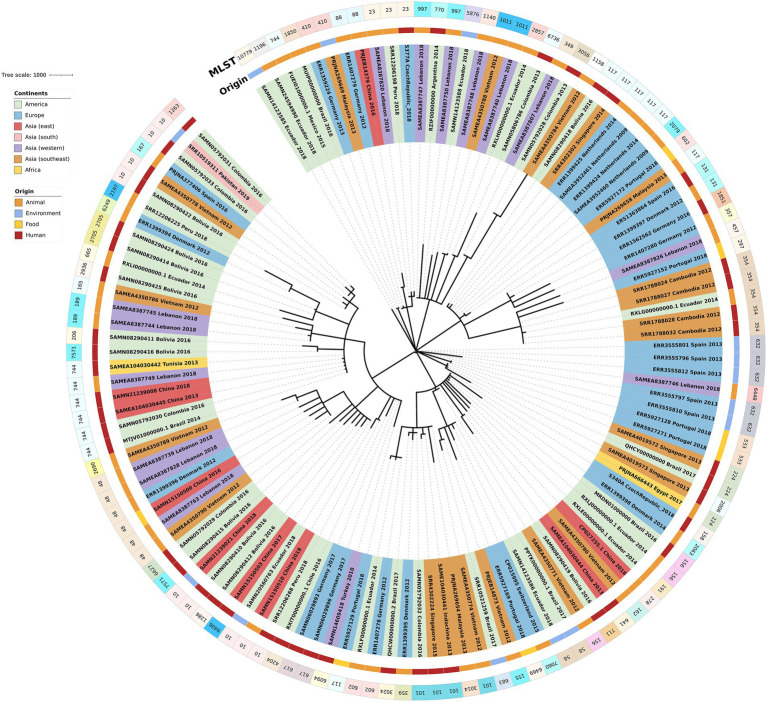

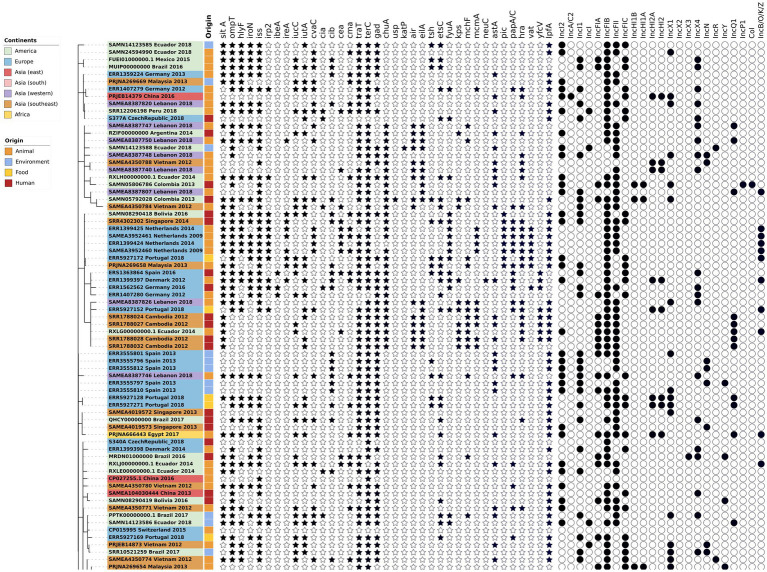

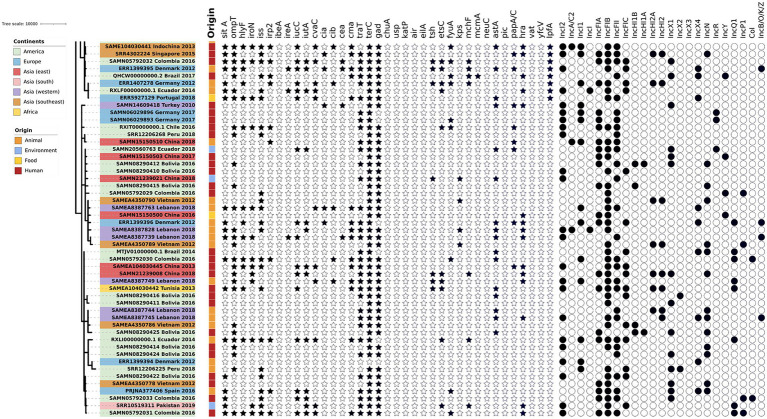

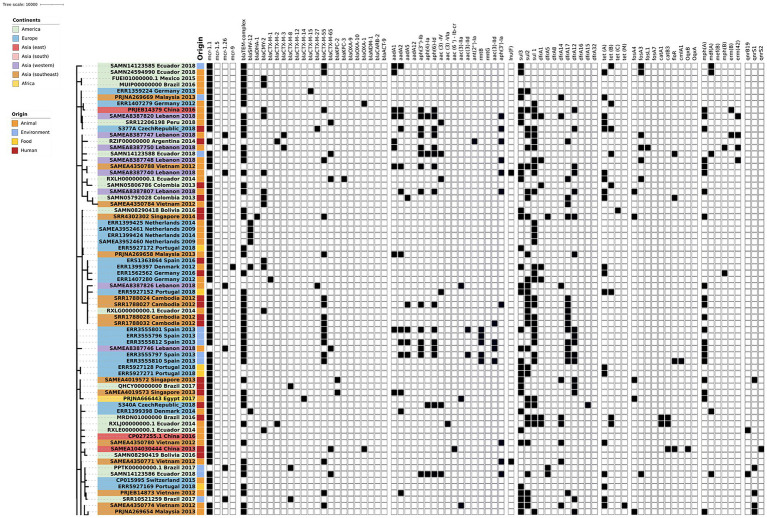

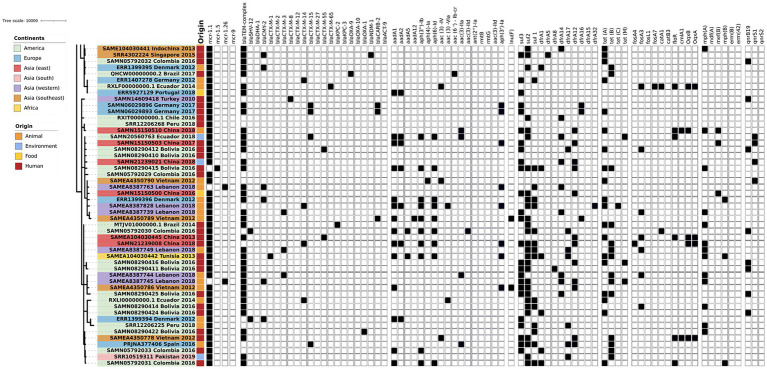

The phylogenetic tree of the core-genome multilocus sequence type allelic profiles of mcr-1 harboring E. coli isolates evaluated in this study is shown in Figure 1, which includes the MLST profile of the isolates, the origin of isolation, and the continent. The name of the isolate corresponds to their NCBI, ENA, or internal database, followed by the country and the year of isolation. The virulence genes and plasmid content of the evaluated E. coli sequences are shown in Figures 2, 3. The antibiotic-resistance genes are indicated in Figures 4, 5. A comparison of the topologies of the cgMLST-phylogenetic tree reveals that the evolutionary relationships among mcr-1 harboring E. coli were not entirely correlated with the origin of the samples (animal, environmental, human, and food/feed) and the geographical precedence.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the core-genome multilocus sequence type allelic profiles of mcr-1 harboring Escherichia coli isolates evaluated in this study. Clusters are colored and labeled according to their continent of origin and the source of isolation.

Figure 2.

Virulence genes and plasmid content of the evaluated E. coli sequences (Part one). The source of the isolates is specified by different colors in the genomic cg-MLST tree branches. The presence and absence of virulence genes and plasmid incompatibility groups are indicated by star and circle symbols, respectively.

Figure 3.

Virulence genes and plasmid content of the evaluated E. coli sequences (Part two). The source of the isolates is specified by different colors in the genomic cg-MLST tree branches. The presence and absence of virulence genes and plasmid incompatibility groups are indicated by star and circle symbols, respectively.

Figure 4.

Antibiotic resistance genes content of the evaluated E. coli sequences (Part one). The source of the isolates is specified by different colors in the genomic cg-MLST tree branches. Squares indicate the presence (black) and absence (white) of antibiotic resistance genes.

Figure 5.

Antibiotic resistance genes content of the evaluated E. coli sequences (Part two). The source of the isolates is specified by different colors in the genomic cg-MLST tree branches. Squares indicate the presence (black) and absence (white) of antibiotic resistance genes.

Virulence

The presence of virulence genes stratified by the origin of the samples (environmental, human, food and animal) was generally homogeneous (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test). Globally, one of the most frequent virulence genes detected was the virulence factor terC (resistance to tellurium), which had an incidence of 96%. However, even though the Ter operon role was associated with pathogenicity and stress response, the biochemical mechanisms of this association are still unclear (Turkovicova et al., 2016). The resistance followed by the gad factor (glutamate decarboxylase system) had an incidence of 77%, and traT (serum resistance in E. coli) had an incidence of 76% of the evaluated genomes. The presence of gad genes was suggested as a prescreening marker for the detection of pathogenic E. coli groups and this was applied to evaluate the load of pathogens in environmental samples (Grant et al., 2001; Hoorzook and Barnard, 2021). Both genes, gad and traT were often detected in clinical and animal isolates of E. coli worldwide (Firoozeh et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2021).

The sitA virulence vector (prevents unproductive conjugation) was recorded in all of the animal samples from 2014 and 2018; sitA was applied as an excellent genetic marker for the identification of avian pathogenic E. coli, considering their significantly difference in the expression on pathogenic vs. non-pathogenic strains (Schouler et al., 2012). In addition, this gene was frequently detected in highly-pathogenic extra-intestinal E. coli (ExPEC) isolates worldwide (Bakhshi et al., 2020). In the E. coli isolates from environmental and food/feed samples, the lpfA gene (long polar fimbriae associated with adherence) was detected with considerable frequency (71 and 86% of the analyzed genomes) in comparison with isolates from human and animal origin. lpfA was commonly associated with enteropathogenic E. coli (Ross et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2021). In a recent study carried out in Brazil, there was a statistically significant increased presence of the lpfA gene (p < 0.05) in E. coli from agricultural soils in comparison with the isolates from non-agriculture origin (Furlan and Stehling, 2021), highlighting the role of animal manure as potential source of virulence genes.

Another virulence gene frequently detected in environmental samples was iutA (ferric aerobactin receptor). The presence of this gene was significatively higher in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli, and their presence might be a disadvantage for colonization in humans and animals (Ikeda et al., 2021). In contrast, the gene iss (serum survival) was highly correlated with isolates from human, animal, and food/feed origin. This gene could influence capsule production in bacteria (Biran et al., 2021). The rest of the virulence genes were distributed in homogenous and lower densities among the isolates from different sample origins. No significant differences were identified in the detection of virulence genes according to their geographical origin (p > 0.05; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

Antibiotic resistance genes

The mcr-1-harboring E. coli commonly show different antibiotic resistance patterns, and the detection of multiresistant genotypes in these isolates increases their epidemiological relevance significantly. Among the analyzed genomes, the variant mcr-1.1 is the most frequently detected globally. In western Asia, the variant mcr-1.26 from different STs was detected in avian isolates from Lebanon. The same variant was detected in isolates from highly polluted water samples from Brazil that included highly-pathogenic STs (Furlan et al., 2020). The variant mcr-1.5 was detected in Bolivian E. coli isolate of human origin (NCBI Accession SAMN08290415). Nowadays, no additional information about this isolate has been published.

Interestingly, one isolate from animal origin in Denmark (NCBI run ERR1399397, NCBI accession PRJEB13885, ENA submission ERA613496) shows the co-harboring of two mobile colistin resistance genes: mcr-1.1 and mcr-9. Additionally, this isolate encodes the extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) genes blaSHV and blaCMY. However, no additional information about this isolate was published until now. The co-occurrence of mcr gene variants is not frequently detected; however, there are a few recent reports from an E. coli isolate of human origin in Thailand (mcr-2 and mcr-3; Phuadraksa et al., 2022). Another study that reports the occurrence of co-harbored mcr variants was conducted in Laos, detecting mcr-3 and mcr-8 genes inside one isolate from Klebsiella pneumoniae (accession number CP035204; Hadjadj et al., 2019). Furthermore, the detection in the same strain of different variants of mcr genes poses a threat to the spread of colistin resistance through horizontal and vertical gene transfer.

Most mcr-harboring bacteria possess multidrug resistance phenotypes and their subsequent antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs). No significant differences were identified according to the sample origin (p > 0.05; one-way ANOVA). However, significant differences were identified between geographic locations in the detection of ARGs (p > 0.05; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test). This was specifically found between the American and African groups and South and East Asian and African groups. Among the vast plethora of ARGs detected in silico, the most frequent genes detected were the ESBL genes. blaTEM was seen in higher proportions in environmental (93%), human (68%), food/feed (71%), and animal (53%) samples. According to the geographical distribution, this gene was detected worldwide in 50–100% of samples, showing a higher presence in Asian and African isolates. Another ESBL gene with a considerable presence was blaCTX-M which has shown extended dissemination in the worldwide community since the 2000s (Chong et al., 2018). Among the CTX-M variants of clinical relevance, blaCTX-M-55 represented the most frequent gene detected, especially in environmental isolates (43%) and with lower frequency in human and animal samples. The same trend was observed in blaCTX-M-65 and blaCTX-M-15, showing higher positive results in environmental samples compared to animal and human isolates. The variants CTX-M-65 and CTX-M-55 showed a familiar presence in isolates from Asia, Europe, and America. Several questions still arise to elucidate these trends that link the environmental sources as a potential reservoir or origin of these CTX-M subtypes and the acceleration of the dissemination in the community.

The increasing resistance to carbapenems (last-resort antibiotic class) represents a severe threat to the healthcare system worldwide (García-Betancur et al., 2021). The WHO global priority pathogen list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria includes Enterobacterales carbapenem-resistant as critical (priority 1; WHO, 2017). The carbapenemase enzymes detected in the mcr-1 E. coli included KPC, OXA, and NDM in human and animal samples from Singapore, Brazil, Bolivia, Germany, Ecuador, and China. No environmental or feed isolates evaluated show a co-harboring of carbapenemases and mcr genes. The dissemination of isolates that harbor mcr-1 and carbapenemases constitutes a public health issue, although these isolates have been reported in low frequency until now (Dalmolin et al., 2019; Bilal et al., 2021). The increasing detection of isolates that co-harbor critically important ARGs emphasized the importance of prompt surveillance strategies to reduce the dissemination of these highly critical clones worldwide.

Other β-lactamases detected inside the mcr-E. coli, mainly in human and animal origin isolates, are the blaCARB and the blaCMY genes. The carbenicillinase resistance gene blaCARB, earlier known as blaPSE, is commonly associated with a chromosomal cassette in different bacterial genera, including Acinetobacter, Salmonella, Escherichia, and Pseudomonas (Kamolvit et al., 2015; Monte et al., 2020). Furthermore, the presence of blaCMY AmpC-β-lactamases are one of the primary mechanisms for resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and were one of the most common β-lactamases detected in Enterobacterales from poultry origin worldwide (Dandachi et al., 2018; Rizi et al., 2020).

Other ARGs commonly detected in mcr-1 harboring E. coli in all the sample types and origins were the resistance genes sul1, sul2, and sul3 that codify resistance to sulfonamides. Considering the prolonged usage of this antibiotic family, the resistance to sulfonamides was widespread in different environments, including pristine locations (Pruden et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2021). Although less commonly found, another group of ARGs frequently detected was the tetracycline-resistance genes tetA and tetB, which are widely reported on the current clones that circulate worldwide. The extensive use of tetracyclines in veterinary and clinical settings as prophylactics and growth promoters may lead to the selective pressure for developing and disseminating those ARGs (Rose et al., 2016; Samanta and Bandyopadhyay, 2020).

Another antibiotic group extensively used in veterinary practice and which showed a considerable presence of ARGs was the macrolides, which caused a concomitant rise in resistance to these drugs in animal pathogens worldwide (Samanta and Bandyopadhyay, 2020). The ARG mphA (macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase I) was detected in the 28% of the evaluated isolates, showing a homogeneous distribution in animal, human and environmental samples. However, a higher presence of this gene was observed in the isolates of southeast and western Asia compared to America and Europe. In addition, the presence of acquired ARGs to the trimethoprim gene dfrA (dihydrofolate reductase) variants was considerably higher in Asian countries compared with European and American countries. In Enterobacterales, these genes are usually part of mobile gene cassettes associated with integrons (Partridge et al., 2009). This ARG is widespread in Gram-negative bacteria and is found in Staphylococci (Zinner and Mayer, 2015; Rossolini et al., 2017). Surpringsily, the variants dfrA12, dfrA17, and dfrA5 showed higher percentages in the isolates from environmental sources compared with animal and human isolates, where the proportions were equal.

Plasmid content

The plasmids represent the mobile genetic element (MGE) that was considered the principal vector for horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of the variants of mcr-1 reported to date (Shen et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2018). Unfortunately, the sequences data were mainly based on short-read sequencing. This is because the identification of the specific location of the resistance genes is unclear because de novo assembly of reads from total genomic DNA does not allow the separation of the assemblies according their original location (plasmids or chromosome; Wang et al., 2021).

IncFIB, IncFII, IncI2, IncI1, IncFIC, IncFIA, IncX1, and IncX4 were the plasmids with the highest occurrence in animal, human, food, and environmental samples. Moreover, these plasmids have been reported to be associated with HGT for mcr-1 variants and other ARGs (Ghasemian et al., 2018; Daza-Cardona et al., 2022). Geographically, there is an apparent homogeneity in the presence of the plasmids IncFIB, IncFII, and IncI2. However, in Europe, the occurrence of the plasmid IncI1 was notably higher in comparison with the other continents. The same trend was observed with the plasmid IncX4, with a considerable presence in isolates from western Asia and Europe compared to the rest of Asia and America. In addition, the plasmid incompatibility group IncN was more frequent in the southeast Asia region. IncHI2A and IncHI2 exhibited similar occurrences according to the geographical origin; however, these incompatibility groups were not present in environmental samples. IncHI1B and IncHI1A were present only in samples from America and Southeast Asia, and the higher incidence was in human samples. The presence of these plasmids was null in environmental isolates.

Conversely, IncA/C2 was the only plasmid absent in America, Europe and Africa but latent in Asia. This, in turn, had a low incidence in animal and human samples, being absent in food and environmental samples. Finally, the IncX2, IncX3 and Col plasmids were the only plasmids that were not present in Asia but only present in America and even there in small numbers. These in turn, were not present in food or environmental samples. The difference between IncX3 and IncX2 and Col was absent in animal samples.

Therefore, based on the information collected, it can be indicated that the highest diversity of plasmids was found in animal samples, followed by human, and environmental samples. In turn, Asia was the continent that led with the largest diversity and occurrence of these plasmids, followed by America and Europe.

Conclusion

Whole-genome sequencing allows the scientific community to better understand the evolution and dissemination of antibiotic resistance worldwide. However, several questions still need to be answered. As noted above, the E. coli isolates that harbor mcr-1 showed a wide plethora of ARGs, plasmid-types and virulence genes, demonstrating in most cases a multiresistance profile based on their genotypic information. It is essential to note the higher percentages of co-resistant ARGs detected in environmental samples of clinical relevance, which highlights the critical role of the environment in the AMR crisis. However, these results only represent the top of the iceberg, considering that WGS is not considered as part of the surveillance programs in the majority of countries. Additionally, it is remarkable how limited are the number of isolates from environmental origin and the geographical bias for the analysis of AMR worldwide. These findings highlight the relevance of analyzing the environmental settings as an integral part of the surveillance programs to understand the origins and dissemination of AMR.

Author’s note

This article was developed through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership coordinated by TDR, the UNICEF, UNDP, World Bank, WHO Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases hosted at the World Health Organization. The specific SORT IT program that led to this research article included an implementation partnership of TDR and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the WHO Country offices of Colombia and Ecuador; the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Colombia; Food and Agriculture Organization, Sierra Leone; Sustainable Health Systems, Freetown, Sierra Leone; The Tuberculosis Research and Prevention Center Non-Governmental Organization, Armenia; The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, Paris, France and South East Asia offices, India; Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; Damien Foundation, Belgium; Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Epidemiology; Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER); GMERS Medical College Gotri Vadodara Gujarat, India; India Medical College Baroda, Gujarat, India; Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College, India; Public Health, Ontario; The Universidade Federal de Ciencias de Saude de Porto Alegre, Brazil; Universidade de Brasilia, Brazil; Universidad de Concepcion, Chile, Universidad de los Andes, Colombia; Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Colombia; Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia; The Central University of Ecuador and; California State University of Fullerton, United States; The Autonomous University of Yucatán, México.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

WC-C designed the investigation. KR, AM, JM, and CB-C performed the preliminary analyses of the data. WC-C, KR, AM, and JM performed genomic analysis, including genome assemblies, MLST, antibiotic resistance genes, plasmid and cgMLST analysis. MR, NO-G, TS, CD, and AH collaborated in the protocol designing according to Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative SORT IT (Partnership between TDR-UNICEF, UNDP, World Bank and WHO). WC-C, AH, NO-G, TS, CD, CB-C, and MR obtained the approbation from the Ethics Advisory Groups from PAHO and The Union. WC-C supervised the entire work. WC-C, AM, JM, and AH wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1032753/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bakhshi M., Zandi H., Bafghi M. F., Astani A., Ranjbar V. R., Vakili M. (2020). A survey for phylogenetic relationship; presence of virulence genes and antibiotic resistance patterns of avian pathogenic and uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from poultry and humans in Yazd, Iran. Gene Rep. 20:100725. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2020.100725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal H., Ur Rehman T., Khan M. A., Hameed F., Jian Z. G., Han J., et al. (2021). Molecular epidemiology of mcr-1, blaKPC-2, and blaNDM-1 harboring clinically isolated Escherichia coli from Pakistan. Infect. Drug Resist. 14, 1467–1479. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S302687, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biran D., Sura T., Otto A., Yair Y., Becher D., Ron E. Z. (2021). Surviving serum: the Escherichia coli is gene of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli is required for the synthesis of group 4 capsule. Infect. Immun. 89:e0031621. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00316-21/SUPPL_FILE/IAI.00316-21-S0001.XLSX, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaerts B., Winand R., Fu Q., Van Braekel J., Ceyssens P. J., Mattheus W., et al. (2019). Validation of a bioinformatics workflow for routine analysis of whole-genome sequencing data and related challenges for pathogen typing in a European national reference center: Neisseria meningitidis as a proof-of-concept. Front. Microbiol. 10:362. doi: 10.3389/FMICB.2019.00362/BIBTEX, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolaia V., Kaas R. S., Ruppe E., Roberts M. C., Schwarz S., Cattoir V., et al. (2020). Res finder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 3491–3500. doi: 10.1093/JAC/DKAA345, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Hasman H. (2020). “Plasmid finder and in silico pMLST: identification and typing of plasmid replicons in whole-genome sequencing (WGS),” in Horizontal Gene Transfer: Methods and Protocols Methods in Molecular Biology, (ed.) Cruz F.. New York, NY: Springer US, (pp. 285–294). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong Y., Shimoda S., Shimono N. (2018). Current epidemiology, genetic evolution and clinical impact of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Genet. Evol. 61, 185–188. doi: 10.1016/J.MEEGID.2018.04.005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino S., Voldby Larsen M., Møller Aarestrup F., Lund O. (2013). Pathogen finder--distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS One 8:e77302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077302, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadashi M., Sameni F., Bostanshirin N., Yaslianifard S., Khosravi-Dehaghi N., Nasiri M. J., et al. (2021). Global prevalence and molecular epidemiology of mcr-mediated colistin resistance in Escherichia coli clinical isolates: a systematic review. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 29, 444–461. doi: 10.1016/J.JGAR.2021.10.022, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmolin T. V., Wink P. L., De Lima-Morales D., Barth A. L. (2019). Low prevalence of the mcr-1 gene among carbapenemase-producing clinical isolates of Enterobacterales. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 40, 263–264. doi: 10.1017/ICE.2018.301, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandachi I., Chabou S., Daoud Z., Rolain J. M. (2018). Prevalence and emergence of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-, carbapenem- and colistin-resistant gram negative bacteria of animal origin in the Mediterranean basin. Front. Microbiol. 9:2299. doi: 10.3389/FMICB.2018.02299/BIBTEX, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daza-Cardona E. A., Buenhombre J., Dos Santos Fontenelle R. O., Barbosa F. C. B. (2022). Mcr-mediated colistin resistance in South America, a one health approach: a review. Rev. Res. Med. Microbiol. 33, E119–E136. doi: 10.1097/MRM.0000000000000293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elbediwi M., Li Y., Paudyal N., Pan H., Li X., Xie S., et al. (2019). Global burden of colistin-resistant bacteria: mobilized colistin resistance genes study (1980–2018). Microorganisms 7:461. doi: 10.3390/MICROORGANISMS7100461, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falagas M. E., Kasiakou S. K., Saravolatz L. D. (2005). Colistin: the revival of Polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 1333–1341. doi: 10.1086/429323, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand A. S., Kelaher M., Lane C. R., da Silva A. G., Sherry N. L., Ballard S. A., et al. (2021). An implementation science approach to evaluating pathogen whole genome sequencing in public health. Genome Med. 13, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/S13073-021-00934-7/TABLES/2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firoozeh F., Saffari M., Neamati F., Zibaei M. (2014). Detection of virulence genes in Escherichia coli isolated from patients with cystitis and pyelonephritis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 29, 219–222. doi: 10.1016/J.IJID.2014.03.1393, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde B. M., Zowawi H. M., Harris P. N. A., Roberts L., Ibrahim E., Shaikh N., et al. (2018). Discovery of mcr-1-mediated colistin resistance in a highly virulent Escherichia coli lineage. mSphere 3, 486–504. doi: 10.1128/MSPHERE.00486-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan J. P. R., Savazzi E. A., Stehling E. G. (2020). Widespread high-risk clones of multidrug-resistant extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli B2-ST131 and F-ST648 in public aquatic environments. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 56:106040. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106040, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan J. P. R., Stehling E. G. (2021). Multiple sequence types, virulence determinants and antimicrobial resistance genes in multidrug- and colistin-resistant Escherichia coli from agricultural and non-agricultural soils. Environ. Pollut. 288:117804. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2021.117804, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Betancur J. C., Appel T. M., Esparza G., Gales A. C., Levy-Hara G., Cornistein W., et al. (2021). Update on the epidemiology of carbapenemases in Latin America and the Caribbean. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 19, 197–213. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1813023, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD (2019). Antimicrobial resistance collaborators (2022). Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 400, 2221–2248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02185-7, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemian A., Shafiei M., Hasanvand F., Shokouhi Mostafavi S. K. (2018). Carbapenem and colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: worldwide spread and future perspectives. Rev. Res. Med. Microbiol. 29, 173–176. doi: 10.1097/MRM.0000000000000142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M. A., Weagant S. D., Feng P. (2001). Glutamate decarboxylase genes as a prescreening marker for detection of pathogenic Escherichia coli groups. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 3110–3114. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.7.3110-3114.2001/ASSET/41BF8267-4589-4654-A0B9-05A66210C00D/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/AM0710130002.JPEG, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjadj L., Baron S. A., Olaitan A. O., Morand S., Rolain J.-M. (2019). Co-occurrence of variants of mcr-3 and mcr-8 genes in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from Laos. Front. Microbiol. 10:2720. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02720, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoorzook K. B., Barnard T. G. (2021). Absolute quantification of E. coli virulence and housekeeping genes to determine pathogen loads in enumerated environmental samples. PLoS One 16:e0260082. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0260082, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Yang X., Shi X., Erickson D. L., Nagaraja T. G., Meng J. (2021). Whole-genome sequencing analysis of uncommon Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from cattle: virulence gene profiles, antimicrobial resistance predictions, and identification of novel O-serogroups. Food Microbiol. 99:103821. doi: 10.1016/J.FM.2021.103821, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein N. H., AL-Kadmy L. M. S., Taha B. M., Hussein J. D. (2021). Mobilized colistin resistance (mcr) genes from 1 to 10: a comprehensive review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 48, 2897–2907. doi: 10.1007/S11033-021-06307-Y/FIGURES/7, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IACG (2019). No time to wait: securing the future from drug-resistant infections. Available at: https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/interagency-coordination-group/IACG_final_report_EN.pdf?ua=1 [].

- Ikeda M., Kobayashi T., Fujimoto F., Okada Y., Higurashi Y., Tatsuno K., et al. (2021). The prevalence of the iutA and ibeA genes in Escherichia coli isolates from severe and non-severe patients with bacteremic acute biliary tract infection is significantly different. Gut Pathog. 13:32. doi: 10.1186/s13099-021-00429-1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamolvit W., Derrington P., Paterson D. L., Sidjabat H. E. (2015). A case of IMP-4-, OXA-421-, OXA-96-, and CARB-2-producing Acinetobacter pittii sequence type 119 in Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 727–730. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02726-14/ASSET/AEED766D-BEEB-417B-873B-DB02EF2C583E/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/ZJM9990940110001.JPEG, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye K. S., Pogue J. M., Tran T. B., Nation R. L., Li J. (2016). Agents of last resort: polymyxin resistance. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 30, 391–414. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Woo J. H., Kim N., Kim M. H., Kim S. Y., Son J. H., et al. (2019). Characterization of chromosome-mediated colistin resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from livestock in Korea. Infect. Drug Resist. 12, 3291–3299. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S225383, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovac J., Dudley E. G., Nawrocki E. M., Yan R., Chung T. (2021). Whole genome sequencing: the impact on foodborne outbreak investigations. Compr. Foodomics. 1, 147–159. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.22697-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen M. V., Cosentino S., Rasmussen S., Friis C., Hasman H., Marvig R. L., et al. (2012). Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Bork P. (2021). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKAB301, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Sun W., Jin D., Yu Q., Yang Y., Zhang Z., et al. (2021). Effect of composting on the conjugative transmission of sulfonamide resistance and sulfonamide-resistant bacterial population. J. Clean. Prod. 285:125483. doi: 10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2020.125483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-Y., Wang Y., Walsh T., Yi L.-X., Zhang R., Spencer J. (2015). Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson M., Brink A., Gouws J., Mbelle N., Naidoo V., Pople T., et al. (2018). The one health stewardship of colistin as an antibiotic of last resort for human health in South Africa. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, e288–e294. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30119-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte D. F. M., Sellera F. P., Lopes R., Keelara S., Landgraf M., Greene S., et al. (2020). Class 1 integron-borne cassettes harboring blaCARB-2 gene in multidrug-resistant and virulent salmonella typhimurium ST19 strains recovered from clinical human stool samples, United States. PLoS One 15:e0240978. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0240978, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. J., Ikuta K. S., Sharara F., Swetschinski L., Robles Aguilar G., Gray A., et al. (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0/ATTACHMENT/B227DEB3-FF04-497F-82AC-637D8AB7F679/MMC1.PDF, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Genomic Surveillance of AMR (2020). Whole-genome sequencing as part of national and international surveillance programmes for antimicrobial resistance: a roadmap. BMJ Glob. Health 5, 1–13. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002244, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAHO/WHO (2016). Epidemiological Alert: Enterobacteriacea With Plasmid-mediated Transferable Colistin Resistance, Public Health Implications in the Americas. Washington, DC: PAHO/WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge S. R., Tsafnat G., Coiera E., Iredell J. R. (2009). Gene cassettes and cassette arrays in mobile resistance integrons: review article. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 757–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuadraksa T., Wichit S., Arikit S., Songtawee N., Yainoy S. (2022). Co-occurrence of mcr-2 and mcr-3 genes on chromosome of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from healthy individuals in Thailand. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 60:106662. doi: 10.1016/J.IJANTIMICAG.2022.106662, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruden A., Arabi M., Storteboom H. N. (2012). Correlation between upstream human activities and riverine antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 11541–11549. doi: 10.1021/es302657r, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizi K. S., Mosavat A., Youssefi M., Jamehdar S. A., Ghazvini K., Safdari H., et al. (2020). High prevalence of blaCMY AmpC beta-lactamase in ESBL co-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. clinical isolates in the northeast of Iran. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 22, 477–482. doi: 10.1016/J.JGAR.2020.03.011, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose L., Peahota M. M., Gallagher J. C. (2016). Beta-lactams and Tetracyclines. Side Eff. Drugs Annu. (Elsevier) 38, 217–227. doi: 10.1016/bs.seda.2016.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross B. N., Rojas-Lopez M., Cieza R. J., McWilliams B. D., Torres A. G. (2015). The role of long polar fimbriae in Escherichia coli O104:H4 adhesion and colonization. PLoS One 10:e0141845. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0141845, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossolini G. M., Arena F., Giani T. (2017). Mechanisms of antibacterial resistance. Infect. Dis. (Auckland). 2, 1181–1196. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7020-6285-8.00138-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta I., Bandyopadhyay S. (2020). “Resistance to aminoglycoside, tetracycline and macrolides,” in Antimicrobial Resistance in Agriculture. Academic Press. 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Schouler C., Schaeffer B., Brée A., Mora A., Dahbi G., Biet F., et al. (2012). Diagnostic strategy for identifying avian pathogenic Escherichia coli based on four patterns of virulence genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1673–1678. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05057-11, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z., Wang Y., Shen Y., Shen J., Wu C. (2016). Early emergence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli from food-producing animals. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16:293. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00061-X, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Zhang H., Liu Y. H., Feng Y. (2018). Towards understanding MCR-like colistin resistance. Trends Microbiol. 26, 794–808. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.006, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli E., Carrara E., Savoldi A., Kattula D., Burkert F. (2017). Global Priority List of Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. Washington, DC: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Tetzschner A. M. M., Johnson J. R., Johnston B. D., Lund O., Scheutz F. (2020). In silico genotyping of Escherichia coli isolates for extraintestinal virulence genes by use of whole-genome sequencing data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 58:e01269-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01269-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkovicova L., Smidak R., Jung G., Turna J., Lubec G., Aradska J. (2016). Proteomic analysis of the TerC interactome: novel links to tellurite resistance and pathogenicity. J. Proteome 136, 167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.01.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Li Q., Kang J., Zhang Z., Song Y., Yin D., et al. (2021). Co-production of NDM-1, CTX-M-9 family and mcr-1 in a Klebsiella pneumoniae ST4564 strain in China. Infect. Drug Resist. 14, 449–457. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S292820, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2017). Global Priority List of Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. Washington, DC: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank (2017). Drug-resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future (Final Report). Washington, DC: World Bank, (pp. 1–132). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Abbas M., Rehman M. U., Wang M., Jia R., Chen S., et al. (2021). Updates on the global dissemination of colistin-resistant Escherichia coli: an emerging threat to public health. Sci. Total Environ. 799:149280. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149280, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Yang Y., Wu M., Ma F., Xu Y., Deng B., et al. (2021). Role of long polar fimbriae type 1 and 2 in pathogenesis of mammary pathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Dairy Sci. 104, 8243–8255. doi: 10.3168/JDS.2021-20122, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinner S. H., Mayer K. H. (2015). Sulfonamides and trimethoprim. Mand. Douglas. Bennett’s Princ. Pract. Infect. Dis. 1, 410–418.e2. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4557-4801-3.00033-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.