Abstract

Background

Population distribution of reduced diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) in smokers and main consequences are not properly recognised. The objectives of this study were to describe the prevalence of reduced DLCO in a population-based sample of current and former smoker subjects without airflow limitation and to describe its morphological, functional and clinical implications.

Methods

A sample of 405 subjects aged 40 years or older with postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity (FVC) >0.70 was obtained from a random population-based sample of 9092 subjects evaluated in the EPISCAN II study. Baseline evaluation included clinical questionnaires, exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) measurement, spirometry, DLCO determination, 6 min walk test, routine blood analysis and low-dose CT scan with evaluation of lung density and airway wall thickness.

Results

In never, former and current smokers, prevalence of reduced DLCO was 6.7%, 14.4% and 26.7%, respectively. Current and former smokers with reduced DLCO without airflow limitation were younger than the subjects with normal DLCO, and they had greater levels of dyspnoea and exhaled CO, greater pulmonary artery diameter and lower spirometric parameters, 6 min walk distance, daily physical activity and plasma albumin levels (all p<0.05), with no significant differences in other chronic respiratory symptoms or CT findings. FVC and exhaled CO were identified as independent risk factors for low DLCO.

Conclusion

Reduced DLCO is a frequent disorder among smokers without airflow limitation, associated with decreased exercise capacity and with CT findings suggesting that it may be a marker of smoking-induced early vascular damage.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Tobacco and the lung, Lung Physiology, Imaging/CT MRI etc, Exercise

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) provides information on the effective alveolar-capillary surface area available for gas transfer in the lungs.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Reduced DLCO is a frequent finding among smokers without airflow limitation.

This functional disorder is associated with a limited exercise tolerance and reduced daily physical activity, as well as a larger pulmonary artery diameter.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Absence of differences in the lung parenchyma attenuation suggests that DLCO may be a surrogate marker of smoking-induced early vascular lung damage.

Introduction

Cigarette smoke has been identified as a major risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a progressive destructive lung disease with persistent chronic inflammation characterised by airflow limitation,1 2 that is, usually identified by spirometry, the most common lung function test.

Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO), a complex test that provides a quantitative measure of the effective alveolar-capillary surface area available for gas transfer in the lungs, is also currently used in the clinical setting for the characterisation of subjects with COPD.3 DLCO is useful in distinguishing COPD phenotypes4 5 and for predicting increased symptoms, poor quality of life, decreased exercise tolerance and severe exacerbations in patients with COPD.3 Moreover, among patients with airflow limitation, DLCO negatively correlates with the extend of emphysema on lung CT scans.6

Moreover, DLCO seems to have a role in the evaluation of at-risk subjects, in early stages of lung disease or when they have not yet developed it.7 Thus, some evidence suggests that a reduced DLCO predicts a future decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1),8 9 and it has been reported that, in smokers with normal spirometry, a low DLCO increases the risk of developing COPD.10 Even a DLCO below 85% predicted has been found to be a significant predictor of all-cause mortality.11

This is particularly important, since DLCO could provide more integrated information about the lung abnormalities induced by cigarette smoking. Although most interest has focused on the contributions of cigarette smoke towards injuring the extracellular matrix and pulmonary epithelial cells, critical interdependence has been recognised between alveolar epithelial and microvascular endothelial cells to maintain the airspace structure, and loss of endothelial cells within the lung directly contributes to emphysematous remodelling.12 In fact, along with persistent inflammation, protease-antiprotease imbalance and oxidative stress, smoking-induced endothelial damage has been linked to pulmonary lesions and systemic comorbidities, including pulmonary hypertension and atherosclerosis.13

Although DLCO provides insight into respiratory physiology beyond that obtained with spirometry, including indirect measurement of pulmonary vascular abnormalities, no previous information is available about the population prevalence of low DLCO in subjects with a history of smoking without airflow limitation as well as its clinical and physiological consequences.14 The second Epidemiology of COPD in Spain (EPISCAN II) study, a population-based epidemiological study designed with the main objective of determining the prevalence of COPD in Spain through the analysis of a representative sample of adults from all Spanish regions,15 provides an ideal opportunity to analyse these aspects. This manuscript presents the results of a secondary objective which was to assess the prevalence of DLCO alterations in a population-based sample of current or former smoker subjects without airflow limitation, to identify its determinants and to evaluate the physiological and clinical parameters related to DLCO in these subjects.

Methods

EPISCAN II is a national, multicentre, cross-sectional, population-based epidemiological study, whose protocol, fieldwork and methods have been previously described.15 16 Briefly, the study was conducted at 20 teaching hospitals throughout Spain from April 2017 to February 2019.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the development of the research question, design or recruitment; no patient advisors were required, and data were analysed anonymously. The results will be disseminated to the scientific community in academic writing.

Study subjects

Subjects from the general population, who resided in the postal code areas nearest to the participating hospitals, were selected. A list of random telephone numbers was obtained, stratified according to these postal codes and quotas for sex and age groups. We selected men or women aged 40 years or more, with no physical or cognitive difficulties that would prevent them from completing spirometry or any of the study procedures. To evaluate the secondary outcomes, the first 35 subjects with airflow limitation and the first 35 subjects without airflow limitation from 12 preselected sites were consecutively invited to undergo a DLCO test and thoracic CT scan, with the aim to recruit a total of approximately 400 individuals for each group.

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

For the purposes of this prespecified secondary objective of EPISCAN II, a current smoker was defined as an individual who smoked at least one cigarette, cigar or pipe a day and a former smoker was defined as an individual who had discontinued using any form of tobacco at least 6 months before the study visit. Current or former smoker subjects were included in the analysis if they had a postbronchodilator FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) >0.70 and a cumulative tobacco use of at least 10 pack-years. As a control group, never-smoker subjects with a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC >0.7 were included.

Procedures and measurements

Demographic information on anthropometric characteristics, level of education, family conditions, smoking history and comorbidities were collected. Comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson and COPD-specific co-morbidity test (COTE) indices.17 18 Health status was assessed by the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) questionnaire,19 and the respective questions of the European Community for Coal and Steel Questionnaire (ECSC)20 were used to identify respiratory symptoms (chronic cough, chronic bronchitis, chronic expectoration, dyspnoea or wheezing). The degree of dyspnoea was evaluated by the modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale.21 Physical activity was measured by the Yale Physical Activity Survey questionnaire validated for the Spanish population and the elderly population, providing a summary of the physical activity level, as well as the time and energy cost of weekly physical activity.22

Prebronchodilator and postbronchodilator spirometry was performed using a pneumotachograph (Vyntus Spiro, Carefusion, Germany), according to American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) standardisation23 and using the Global Lung Initiative equations as reference values.24 DLCO was measured by the single-breath method with the same equipment in all study centres (MasterScreen diffusion, Carefusion, Germany) in accordance with ATS/ERS recommendations.5 The DLCO was corrected to body temperature, pressure, water vapour saturated conditions and a minimum of two acceptable manoeuvres that matched within 10% or less of the alveolar volume (VA) and DLCO was required. We excluded tests with a breath-holding time <9 or >11 s, an inspiratory capacity less than 85% of the largest previously measured vital capacity, expiration in >4 s, or with evidence of leaks or Valsalva or Müller manoeuvres. Adjustments were made for atmospheric pressure, haemoglobin levels and CO back pressure using non-invasive estimation of carboxyhaemoglobin by a CO-oximeter according to equations recommended in current standardisation.25 Cotes equations were used as reference values,26 and values below the lower limit of normal were considered reduced.

The 6 min walk test was performed in accordance with ATS guidelines,27 and the Body Obstructive Dyspnoea Exercise (BODE) index28 was calculated accordingly. From each participant, 20 mL of venous blood were collected for routine blood analysis, C reactive protein, fibrinogen and albumin.

CT images were acquired during maximal inspiration, without contrast and with low-dose radiation (120 kVp as acquisition voltage). The images obtained underwent semiautomatic postprocessing for determination of the percentage of emphysema, areas of low attenuation and bronchiolar airway wall thickness, as previously described.16 29 The pulmonary artery (PA) diameter was measured at the level of the PA bifurcation, and the average of two perpendicular measurements of the ascending aorta diameter were taken on the same CT image using mediastinal windows.30 PA enlargement was defined as a PA diameter ≥29 mm in men and ≥27 mm in women.31

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as numbers with percentages, and continuous variables as mean with SD or median (IQR), according to their distribution. Comparisons between subgroups have been performed using the Student’s t-test, analysis of variance, Mann-Whitney U test or χ2 test. The relationship between variables has been assessed with the Pearson correlation analysis. Multiple logistic regression analysis has been used to investigate factors associated with a reduced DLCO. Only variables with a level of significance <0.01 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multiple regression model. The ORs and the coefficient of determination (r2) were calculated for the model. Data were analysed with the SPSS V.25.0 software, considering a p value of 0.05 statistically significant for all tests.

Results

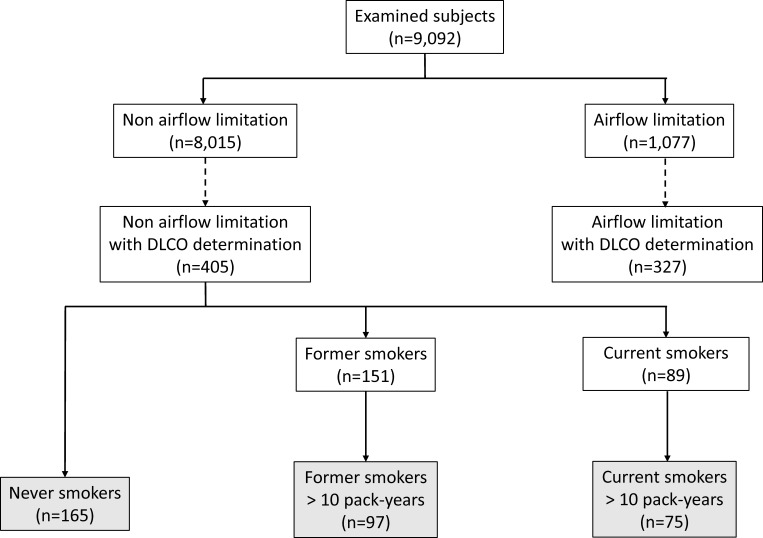

The EPISCAN II population included 9092 subjects who were able to perform a valid spirometry. Among those, 8015 had no airflow limitation, and 405 of them were invited to a longer office visit with DLCO determination and a CT scan. This subgroup was similar to the remaining patients without airflow limitation in terms of demographic characteristics, smoking intensity, comorbidities and spirometric parameters (online supplemental table 1). According to previous definitions, these subjects were classified as never-smokers (n=165), former smokers (n=151) or current smokers (n=89). Last, in the two subsamples of smokers only those subjects with a cumulative use of tobacco greater than 10 pack-years were selected (figure 1). Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of the three study groups.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study participants. DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study subjects*

| Current smokers (n=75) |

Former smokers (n=97) |

Never-smokers (n=165) |

P value | |

| Females, n (%) | 46 (61.3) | 43 (44.3) | 115 (69.7) | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 56±8 | 62±10 | 61±12 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.1±4.6 | 28.1±3.9 | 27.4±5.2 | 0.023 |

| Level of studies, n (%) | 0.051 | |||

| No studies | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Primary education | 7 (9.3) | 24 (24.7) | 33 (20.0) | |

| Secondary education | 23 (30.7) | 14 (14.4) | 32 (19.4) | |

| University | 44 (58.7) | 58 (59.8) | 98 (59.4) | |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 14 (18.7) | 22 (22.7) | 22 (13.3) | 0.143 |

| Pack-years | 32±14 | 32±23 | – | 0.839 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.3±0.7 | 0.5±1.1 | 0.3±0.8 | 0.294 |

| COTE index | 1.4±2.6 | 0.8±1.8 | 1.05±2.4 | 0.212 |

| CAT score | 9.2±6.6 | 6.8±5.4 | 6.2±5.6 | 0.001 |

| Chronic cough, n (%) | 27 (36.5) | 12 (12.5) | 18 (11.2) | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchitis, n (%) | 10 (15.2) | 3 (3.2) | 4 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic expectoration, n (%) | 21 (28.0) | 14 (14.7) | 14 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnoea, n (%) | 6 (8.2) | 16 (16.7) | 26 (16.5) | 0.209 |

| Wheezing, n (%) | 42 (56.8) | 27 (27.8) | 41 (24.8) | <0.001 |

| Baseline SaO2, % | 96±1 | 96±1 | 96±2 | 0.638 |

| Exhaled CO, ppm | 25±16 | 3±4 | 4±5 | <0.001 |

| Prebronchodilator FVC, z-score | 0.07±0.96 | 0.21±1.00 | 0.26±0.93 | 0.365 |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1, z-score | −0.17±1.04 | 0.05±1.09 | 0.21±1.01 | 0.031 |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1/FVC, z-score | −0.46±0.77 | −0.31±0.85 | −0.13±0.83 | 0.014 |

| Postbronchodilator FVC, z-score | 0.10+0.85 | 0.24+0.96 | 0.32+0.99 | 0.164 |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1, z-score | −0.15+0.98 | 0.06+1.11 | 0.19+1.12 | 0.011 |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC, z-score | −0.45+0.80 | −0.32–0.91 | −0.15+1.07 | 0.002 |

| 6MWD, m | 508±102 | 523±94 | 510±101 | 0.539 |

| DLCO, z-score | −0.80±0.60 | −0.30±0.71 | −0.26±0.68 | <0.001 |

| DLCO/VA, z-score | −0.10±0.12 | −0.02±0.12 | −0.01±0.15 | 0.005 |

| VA, z-score | −0.46±0.66 | −0.31±0.68 | −0.25±0.66 | 0.086 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 148±14 | 146±14 | 140±14 | <0.001 |

| Eosinophils, % | 2.1±1.5 | 2.3±1.6 | 2.0±1.6 | 0.440 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 3.9±0.8 | 3.8±0.9 | 3.8±1.0 | 0.910 |

| C reactive protein, mg/L | 1.4±2.8 | 0.9±1.5 | 1.5±2.8 | 0.134 |

| Albumin, g/l | 12.1±16.2 | 17.1±18.4 | 12.5±16.3 | 0.717 |

| BODE index | 1.0±0.5 | 1.1±0.5 | 1.1±0.6 | 0.195 |

| YPAS—physical activity summary | 55±22 | 62±24 | 57±21 | 0.236 |

| Total emphysema volume, % | 1.9±4.4 | 2.6±3.7 | 1.7±3.4 | 0.276 |

| Low density volume, % | 47±20 | 51±18 | 41±18 | 0.005 |

| P15, HU | −910±31 | −919±26 | −904±26 | 0.003 |

| Secondary bronchi WA, % | 25.4±5.7 | 25.3±5.7 | 24.5±5.4 | 0.392 |

| Pulmonary artery diameter, mm | 26±4 | 27±4 | 24±4 | 0.074 |

| Pulmonary artery:aorta ratio | 0.78±0.11 | 0.78±0.11 | 0.79±0.12 | 0.811 |

Comparison between groups using ANOVA or chi-squared test.

*Data are mean±SD or number (percentage).

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMI, body mass index; BODE, Body Obstructive Dyspnoea Exercise; CAT, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test; CO, carbon monoxide; COTE, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-specific co-morbidity test; DLCO, lung diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; HU, Hounsfield units; 6MWD, 6 min walk distance; P15, 15th percentile; SaO2, oxygen saturation; VA, alveolar volume; WA, wall area; YPAS, Yale Physical Activity Survey.

bmjresp-2022-001468supp001.pdf (173.5KB, pdf)

Prevalence of lung diffusing capacity reduction

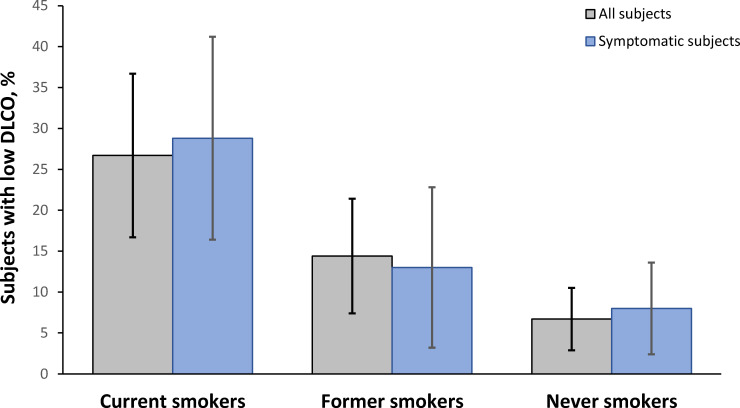

In the subjects selected for the analysis, the frequency of a DLCO below its lower limit of normal was higher in current smokers (26.7%; 95% CI 16.7% to 36.7%) than in former smokers (14.4%; 95% CI 7.4% to 21.4%) or never-smokers (6.7%; 95% CI 2.9% to 10.5%) (p<0.001). When the analysis was limited to subjects with self-reported chronic respiratory symptoms using the ECSC questionnaire, the frequencies obtained in the three subgroups showed a similar pattern (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of a reduced pulmonary diffusion capacity among the different subgroups of the study, considering all the subjects analysed and only those who reported chronic respiratory symptoms. DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide.

Clinical and functional variables related to DLCO

In current and former smoker subjects, women presented lower z-scores than men, both for DLCO (−0.64±0.57 vs −0.34±0.80, p=0.001) and DLCO/VA (−0.11±0.12 vs 0.01±0.12, p<0.001). Table 2 shows the relationship of both the DLCO and the DLCO/VA ratio with the main clinical, functional and morphological variables in all subjects with previous or current tobacco use. In them, DLCO presented an inversely proportional relationship with nicotine dependence assessed by the Fagerström test, health status and exhaled CO levels. In turn, DLCO was directly proportional to spirometric parameters, exercise tolerance (assessed by the distance walked for 6 min), and the level of daily physical activity. Finally, a negative relationship was identified between both DLCO and the DLCO/VA ratio with the diameter of the PA, although without differences in its ratio with the ascending aorta diameter. No other differences in DLCO or DLCO/VA ratio were detected based on the presence of chronic respiratory symptoms (online supplemental table 2).

Table 2.

Relation between diffusion parameters and clinical, functional and morphological variables in subjects with smoking history of more than 10 pack-years*

| DLCO, z-score | DLCO/VA, z-score | |||

| R | P value | R | P value | |

| Age, years | 0.017 | 0.829 | −0.079 | 0.303 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.127 | 0.097 | 0.295 | <0.001 |

| Pack-years | −0.054 | 0.478 | −0.041 | 0.595 |

| Fagerström test | −0.291 | 0.010 | −0.270 | 0.017 |

| Charlson index | 0.020 | 0.799 | 0.103 | 0.179 |

| COTE index | −0.115 | 0.134 | 0.010 | 0.892 |

| CAT total score | −0.194 | 0.011 | −0.084 | 0.271 |

| mMRC dyspnoea scale | −0.299 | 0.565 | 0.041 | 0.938 |

| Baseline SaO2, % | 0.093 | 0.227 | 0.046 | 0.549 |

| Exhaled CO, ppm | −0.370 | <0.001 | −0.302 | <0.001 |

| Prebronchodilator FVC, z-score | 0.352 | <0.001 | −0.136 | 0.074 |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1, z-score | 0.393 | <0.001 | −0.023 | 0.7666 |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1/FVC, z-score | 0.148 | 0.053 | 0.194 | 0.011 |

| 6MWD, m | 0.206 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.793 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 0.087 | 0.261 | 0.117 | 0.133 |

| Eosinophils, % | 0.041 | 0.599 | 0.154 | 0.047 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | −0.073 | 0.390 | −0.098 | 0.248 |

| C reactive protein, mg/L | −0.079 | 0.326 | −0.020 | 0.800 |

| Albumin, g/L | 0.295 | 0.182 | −0.114 | 0.613 |

| BODE index | −0.020 | 0.791 | 0.174 | 0.023 |

| YPAS—physical activity summary | 0.218 | 0.043 | 0.148 | 0.175 |

| Total emphysema volume, % | 0.020 | 0.812 | −0.064 | 0.440 |

| Low density volume, % | 0.050 | 0.547 | −0.021 | 0.801 |

| P15, HU | −0.089 | 0.280 | −0.038 | 0.650 |

| Secondary bronchi WA, % | 0.002 | 0.978 | 0.008 | 0.926 |

| Pulmonary artery diameter, mm | −0.294 | <0.001 | −0.381 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary artery:aorta ratio | 0.027 | 0.748 | 0.082 | 0.321 |

Bold values highlight significant relationships.

*Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and p value are shown.

BMI, body mass index; BODE, Body Obstructive Dyspnoea Exercise; CAT, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test; CO, carbon monoxide; COTE, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-specific co-morbidity test; DLCO, lung diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; HU, hounsfield units; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; 6MWD, 6 min walk distance; P15, 15th percentile; SaO2, oxygen saturation; VA, alveolar volume; WA, wall area; YPAS, Yale Physical Activity Survey.

The analysis of parameters related to DLCO and DLCO/VA ratio carried out separately in current and former smoker subjects (online supplemental tables 3 and 4) showed a trend similar to those described in the joint analysis of both subgroups.

Differences of smoker subjects with reduced or normal DLCO

The comparison of current or former smokers with a DLCO below their lower limit of normal versus subjects with normal DLCO (table 3) shows that DLCO reduction occurs in younger subjects with a higher level of exhaled CO. In addition, smokers with reduced DLCO have lower spirometric parameters, higher levels of dyspnoea, lower exercise tolerance and less daily physical activity. In fact, subjects with reduced DLCO perform less physical activity (median (IQR)) (35 (24–48) vs 57 (30–82) hour/week, p=0.005) and reach a lower energy cost (117 (82–120) vs 187 (99–281) MET × hour/week, p=0.004). Moreover, smokers with low DLCO also have worse BODE scores and lower plasma albumin levels. In turn, larger PA diameters were found in smoker subjects with reduced DLCO compared with those with normal DLCO. In fact, subjects with reduced DLCO showed a tendency towards PA enlargement, although without reaching the level of statistical significance (26.7 vs 12.6%, p=0.083). Online supplemental tables 5 and 6 present the comparison between subjects with reduced and normal DLCO, evaluating current smokers and former smokers separately.

Table 3.

Comparison between current or former smoker subjects according to the lung diffusing capacity*

| Reduced DLCO (n=34) |

Normal DLCO (n=138) |

P value | |

| Females, n (%) | 21 (61.8) | 68 (49.3) | 0.133 |

| Age, years | 54 (48–64) | 60 (54–67) | 0.028 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.7 (21.6–29.1) | 27.1 (24.4–30.0) | 0.237 |

| Level of studies | 0.070 | ||

| No studies | 1 (2.9) | 0 | |

| Primary education | 7 (20.6) | 24 (17.4) | |

| Secondary education | 6 (17.6) | 31 (22.5) | |

| University | 19 (55.9) | 83 (60.1) | |

| Lives alone | 5 (14.7) | 31 (22.5) | 0.227 |

| Pack-years | 25 (20–39) | 30 (20–40) | 0.529 |

| Fagerström test | 4 (3–6) | 4 (2–5) | 0.682 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.4±0.8 | 0.4±1.0 | 0.861 |

| COTE index | 1.9±2.7 | 0.9±2.0 | 0.066 |

| CAT total score | 5.0 (4.5–15.5) | 4 (2-8) | 0.531 |

| mMRC dyspnoea level | 0.037 | ||

| 0 | 23 (67.6) | 105 (76.1) | |

| 1 | 8 (23.5) | 30 (21.7) | |

| 2 | 1 (2.9) | 3 (2.2) | |

| 3 | 2 (5.9) | 0 | |

| Chronic cough, n (%) | 8 (24.2) | 31 (22.6) | 0.503 |

| Chronic bronchitis, n (%) | 2 (6.9) | 11 (8.5) | 0.565 |

| Chronic expectoration, n (%) | 7 (20.6) | 28 (20.6) | 0.604 |

| Wheezing, n (%) | 15 (44.1) | 54 (39.4) | 0.378 |

| Baseline oxygen saturation, % | 97 (96–97) | 96 (96–97) | 0.863 |

| Exhaled CO, ppm | 31 (29–32) | 12 (2–31) | 0.006 |

| Prebronchodilator FVC, z-score | −0.43 (−1.00 to 0.40) | 0.36 (−0.29 to 0.95) | <0.001 |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1, z-score | −0.44 (−1.32 to −0.10) | 0.03 (−0.54 to 0.91) | 0.001 |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1/FVC, z-score | −0.48 (−0.85 to −0.06) | −0.34 (−0.99 to 0.28) | 0.501 |

| Reduced VA, n (%) | 3 (8.8) | 2 (1.4) | 0.053 |

| 6MWD, m | 465 (450–480) | 555 (533–605) | 0.047 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 147 (144–149) | 153 (148–170) | 0.821 |

| Eosinophils, % | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.2 (0.1–1.9) | 0.435 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 4.4 (3.9–4.9) | 3.5 (2.9–4.1) | 0.698 |

| C reactive protein, mg/L | 0.7 (0.2–1.3) | 0.4 (0.1–3.5) | 0.404 |

| Albumin | 4.2 (4.2–4.3) | 4.7 (4.6–39.6) | <0.001 |

| BODE index | 0.006 | ||

| 0–2 points (survival: 80%) | 30 (88.2) | 137 (99.3) | |

| 3–4 (survival: 67%) | 4 (11.8) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Physical activity summary | 29 (24–62) | 53 (34–69) | 0.048 |

| Total emphysema volume, % | 0.69 (0.18–2.80) | 0.34 (0.17–2.79) | 0.261 |

| Low density volume, % | 53 (34–63) | 48 (24–54) | 0.210 |

| P15, HU | −911 (−917 to −886) | −905 (−930 to −889) | 0.127 |

| Secondary bronchi WA, % | 25.8 (22.8–27.5) | 25.3 (20.2–29.8) | 0.928 |

| Pulmonary artery diameter, mm | 25 (24–27) | 23 (21–24) | 0.002 |

| Pulmonary artery:aorta ratio | 0.77 (0.72–0.79) | 0.70 (0.65–0.71) | 0.578 |

| Pulmonary artery enlargement | 8 (26.7%) | 16 (13.4%) | 0.095 |

Comparisons were performed by Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U or χ2 tests.

Bold values highlight significant differences.

*Data are mean±SD, median (IQR) or number (frequency) according to their type and distribution.

BMI, body mass index; BODE, body obstructive dyspnoea exercise; CAT, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test; CO, carbon monoxide; DLCO, lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LLN, lower limit of normal; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; 6MWD, 6 min walk distance; P15, 15th percentile; VA, alveolar volume; WA, wall airway.

Finally, from all those variables that reached statistical significance in the comparison between reduced and normal DLCO in current or former smokers, the multiple logistic regression model only retained prebronchodilator FVC and exhaled CO as independent predictors of reduced DLCO (table 4), although the model contribution to explained variance in DLCO was modest (r2=0.153, p<0.001). The same variables were retained in multiple logistic regression models separately for current and former smokers (online supplemental tables 7 and 8).

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression model to detect decreased DLCO in current and former smoker subjects*

| Variable | B | SE | P value | OR | 95% CI |

| Prebronchodilator FVC, z-score | −0.815 | 0.225 | <0.001 | 0.443 | 0.285 to 0.688 |

| Exhaled CO, ppm | 0.030 | 0.013 | 0.018 | 1.030 | 1.005 to 1.056 |

| Constant | −1.910 | 0.301 | – | – | – |

*Exhaled CO level, prebronchodilator FVC, prebronchodilator FEV1, serum albumin level and pulmonary artery diameter were entered into the model. The BODE index was not entered because it was considered redundant and not strictly applicable to subjects without airflow limitation.

B, regression coefficient; BODE, body obstructive dyspnoea exercise; CI, confidence interval; CO, carbon monoxide; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that reduced DLCO is present in more than a quarter of current smokers without airflow limitation, being associated with lower spirometric parameters, as well as reduced exercise tolerance and less daily physical activity. Furthermore, a reduced FVC and increased exhaled CO have been identified as independent predictors of reduced DLCO in smokers without airflow limitation.

As previous methodological comments, it is worth mentioning that the procedure followed for study subject selection generated a sample with a prevalence of current and former smokers that are the same as in the general population of our country (22% and 25%, respectively).32 In fact, to our knowledge, this is the first article that shows a population approach to the evaluation of DLCO with simultaneous measurements of low dose CT scan in smokers without airflow limitation.

The population prevalence of DLCO below the LLN identified in our study in current and former smokers (19.8%) is consistent with the 17% previously described in active smokers selected from advertisements to assess lung health10 and 24% identified in a retrospective analysis of a lung function database.33 In addition, our data confirm the relationship of DLCO with some previously identified variables, such as male gender or spirometric parameters.34–36 However, the sample analysed has not identified a relationship between DLCO and the presence of chronic respiratory symptoms. This finding is also consistent with a small study of 58 smokers without airflow limitation, in which subjects who reported non-specific respiratory problems, chronic bronchitis or wheezing had lower spirometric parameters, but no differences were found in DLCO or with the single-breath nitrogen method, suggesting that symptoms are more related to physiological changes in the central airways than in the peripheral airways.37

Although some previous studies have described a weak relationship between the DLCO of heavy smokers (>20 pack-years) and lung attenuation,6 38 they included a notable percentage of patients with airflow limitation. Thus, in a subsample of smokers or former smokers from the GenKOLS study, DLCO was related to the percentage of low-attenuation areas and to the standardised airway wall thickness only in patients with COPD, while in subjects without airflow limitation the same relationship was not significant.39 Similarly, in 38 former smokers without airflow limitation, no differences in low-attenuation areas or bronchial wall thickness were identified between those with normal or low DLCO.40 This suggests that, in early phases of smoking-induced lung damage, the decrease in DLCO is not attributable to emphysema-like changes. As DLCO decreases in a wide variety of pathologic conditions, including reduction in alveolar surface area, decreased perfusion, even ventilation or inflammation or fibrosis of the alveolar wall impairing alveolar diffusion,5 impaired gas exchange may not necessarily reflect early emphysema, since it may be due to other smoking-related changes, including altered membrane diffusion or pulmonary vascular changes.41 The contribution of peripheral airways to DLCO reduction has been suggested in never-smokers from the COPDGene cohort, in which small airway dysfunction correlated significantly with lower DLCO among both non-obstructed and GOLD 1–2 subjects.42 This might justify that, in our smoker subjects, FVC was retained as an independent predictor of low DLCO, instead of FEV1, since the former better represents the contribution of the whole bronchial tree, including its most distal portions.

In this study, the other risk factor independently associated with the presence of reduced DLCO was increased exhaled CO. The DLCO correction for exhaled CO suggests that its contribution does not seem to be exclusively dependent on CO backpressure, so it is interesting to consider that exhaled CO is a recognised indicator of oxidative stress,43 one of the main causes of endothelial damage. This possibility is reinforced by the identification in smokers with reduced DLCO of low levels of albumin, a negative acute-phase reactant with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.44 Indeed, it has been suggested that albumin level may be a marker of susceptibility to the oxidative response resulting from smoking, while albuminuria should be a non-invasive marker of arterial stiffness.45 Although merely speculative, these findings are in agreement with some current evidence suggesting that peripheral airway destruction might be initiated, in part, by early smoking-induced damage to the pulmonary vascular endothelium mediated by plasma endothelial microparticles with apoptotic features, which are elevated in smokers with normal spirometry and reduced DLCO.46 It is particularly attractive to consider that, in the absence of lung parenchymal damage, DLCO provides a window into the microvasculature of smoker subjects. Thus, the lower DLCO of smokers probably reflects the presence of greater ventilation-perfusion inequalities, lower carbon dioxide elimination efficiency and, consequently, greater ventilatory stimulation,47 which, in turn, would justify the higher degree of dyspnoea reported by our smokers with reduced DLCO. This basic physiological proposal is in line with studies about exercise response in smokers at risk of COPD, in which exercise dyspnoea is mainly explained by increased inspiratory neural drive.47 Furthermore, this could also explain their lower exercise tolerance, consistently with the previous description of a correlation between low DLCO and reduced 6 min walk distance in former smokers with normal chest CT scans and spirometry.40 However, since the EPISCAN study protocol did not include the determination of functional residual capacity or inspiratory capacity, it is not possible to completely rule out the existence of a certain degree of hyperinflation not detected by lung imaging tests, which is a main determinant of exercise tolerance in patients with airflow limitation.48

Finally, one last aspect of our study to highlight is the larger diameter of the PA found in smokers with reduced DLCO compared with those with normal DLCO. Although this difference does not lead to significant differences in the PA enlargement between the two smoker subgroups or in the relationship between the diameter of the PA and the ascending aorta, which is the most consistent indicator of pulmonary hypertension,49 they might also reflect an early impact of smoking on the pulmonary vascular bed. In this regard, it is interesting to note that cigarette smoking has recently been shown to contribute to pulmonary arterial remodelling through several hypoxia-independent pathways that promote K+channel dysregulation in the absence of clinically established COPD.50

Our study has several limitations that are worth discussing. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow for cause-and-effect relationships to be established, although the data reveal that reduced DLCO is associated with differences in dyspnoea level, exercise tolerance and PA diameter. Second, the sample size may be limiting for some subanalyses, despite providing a representative sample of smokers at the population level and achieving statistical significance in most comparisons. Third, other spirometric parameters suggestive of peripheral airway disease have not been evaluated, such as the FEV3/FEV6 ratio, whose decrease is highly prevalent in smokers with preserved pulmonary function but impaired indices of physical function and quality of life.51 52 And fourth, the EPISCAN II study did also not include specific measurements of small airway function or pulmonary microcirculation to allow for the specific assessment of their relationship with a reduced DLCO.

In conclusion, this study shows that reduced DLCO is a frequent finding among smokers without airflow limitation and is associated with a limited exercise tolerance and reduced daily physical activity, as well as a larger PA diameter. These findings, together with increased exhaled CO and reduced plasma albumin, in the absence of differences in the lung parenchyma attenuation, allow us to speculate that, in these subjects, DLCO may be a surrogate marker of smoking-induced early vascular lung damage.

Acknowledgments

The collaboration of Monica Sarmiento and Neus Canal of IQVIA, and of Maria Victoria Pardo, Miguel Pascual and David Bañas from GSK is explicitly acknowledged.

Footnotes

Twitter: @FranGarciaRio, @MiravitllesMarc, @BorjaCos70

Collaborators: EPISCAN II study: Elena García Castillo; Claudia Valenzuela; Ana Pueyo Bastida; Lourdes Lázaro Asegurado; Luis Rodríguez Pascual; Mª José Mora; Luis Borderias Clau; Lourdes Arizón Mendoza; Sandra García; Juan Antonio Riesco Miranda; Julián Grande Gutiérrez; Jesús Agustín Manzano; Manuel Agustín Sojo González; Miguel Barrueco Ferrero; Milagros Rosales; José Alberto Fernández Villar; Cristina Represas; Ana Priegue; Isabel Portela Ferreño; Cecilia Mouronte Roibás; Sara Fernández García; Rocío Cordova Díaz; Nuria Toledo Pons; Margalida Llabrés; José María Marín Trigo; Marta Forner; Begoña Gallego; Pablo Cubero; Elisabet Vera; Mª Begoña Picurelli Albero; Noelia González García; Agustín Valido Morales; Carolina Panadero; Cristina Benito Bernáldez; Maria Velarde; Antonio Santa Cruz Siminiani; Carlos Castillo Quintanilla; Rocío Ibáñez Meléndez; José Javier Martínez Garcerán; Desirée Lozano Vicente; Pedro García Torres; Maria del Mar Valdivia; Juan Pablo de Torres Tajes; Montserrat Cizur Girones; Carmen Labiano Turrillas; Carlos Ruiz Martínez; Elena Hernando; Elvira Alfaro; José Manuel García; Jorge Lázaro; David Bravo; Laura Hidalgo; Silvia Francisco Terreros; Iñaki Zorrilla; Ainara Alonso Colmenero; Cristina Martínez González; Susana Margon; Rosirys Guzman Taveras; Ramón Fernández; Alicia Álvarez; José Ramón Agüero Balbín; Juan Agüero Calvo; Jaume Ferrer Sancho; Esther Rodríguez González; Eduardo Loeb; José Luis Izquierdo Alonso; Mª Antonia Rodríguez García; Juan Abreu González; Candelaria Martín García; Rebeca Muñoz; Haydée Martín García; Miguel Angel Martínez Muñiz; Andrés Avelino Sánchez Antuña; Jesús Allende González; Jose Antonio Gullón Blanco; Fernando José Alvarez Navascues; Manuel Angel Villanueva Montes; María Rodríguez Pericacho; Concepción Rodríguez García; Juan Diego Alvarez Mavárez.

Contributors: The study concept and design: FG-R, MM, JBS, BGC, JJJJS-C, CC, PdL, IA, JMRG-M, GS and JA. Data acquisition: BGC, JJJJS-C, CC and JA. Analysis and interpretation of the data: FG-R, MM, JBS and BGC. Drafting of the manuscript: FG-R. Critical revision and approval for submission: FG-R, MM, JBS, BGC, JJJJS-C, CC, PdL, IA, JMRG-M, GS and JA. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. FG-R is guarantor for this paper, accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: The EPISCAN II study has been a GlaxoSmithKline sponsored study (grant number: not applicable).

Competing interests: FG-R has received speaker or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Novartis, Pfizer and Rovi, and research grants from Chiesi, Esteve, Gebro Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini and TEVA. MM has received speaker or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, CSL Behring, Laboratorios Esteve, Gebro Pharma, Kamada, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Menarini, Mereo Biopharma, Novartis, pH Pharma, Palobiofarma SL, Rovi, TEVA, Spin Therapeutics, Verona Pharma and Zambon, and research grants from Grifols. JBS has no conflict of interest. BGC has received speaker or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Novartis, Sanofi, TEVA and research grants from Menarini, AstraZeneca and Boehringer-Ingelheim. JJS-C has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Esteve, Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Novartis and Teva, and and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Ferrer and Novartis. CC has received speaker or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Novartis, and research grants from GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini and AstraZeneca. PdL has no conflict of interest. IA has no conflict of interest. JMRG-M has no conflict of interest. MGSH is a GSK employee within the Medical Department. JA has received speaker or consulting fees from Actelion, Air Liquide, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Carburos Médica, Chiesi, Faes Farma, Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, InterMune, Linde Healthcare, Menarini, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Rovi, Sandoz, Takeda y Teva.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

EPISCAN II study:

Elena García Castillo, Claudia Valenzuela, Ana Pueyo Bastida, Lourdes Lázaro Asegurado, Luis Rodríguez Pascual, Mª José Mora, Luis Borderias Clau, Lourdes Arizón Mendoza, Sandra García, Juan AR Miranda, Julián Grande Gutiérrez, Jesús Agustín Manzano, Manuel González, Miguel Barrueco Ferrero, Milagros Rosales, José AF Villar, Cristina Represas, Ana Priegue, Isabel Portela Ferreño, Cecilia Mouronte Roibás, Sara Fernández García, Borja G Cosío, Rocío Cordova Díaz, Nuria Toledo Pons, Margalida Llabrés, José MM Trigo, Marta Forner, Begoña Gallego, Pablo Cubero, Elisabet Vera, Mª BP Albero, Noelia González García, Agustín Valido Morales, Carolina Panadero, Cristina Benito Bernáldez, Maria Velarde, Antonio Santa Cruz Siminiani, Carlos Castillo Quintanilla, Rocío Ibáñez Meléndez, José JM Garcerán, Desirée Lozano Vicente, Pedro García Torres, Maria del Mar Valdivia, Juan PT Tajes, Montserrat Cizur Girones, Carmen Labiano Turrillas, Carlos Ruiz Martínez, Elena Hernando, Elvira Alfaro, José Manuel García, Jorge Lázaro, David Bravo, Laura Hidalgo, Silvia Francisco Terreros, Iñaki Zorrilla, Ainara Alonso Colmenero, Cristina Martínez González, Susana Margon, Rosirys Guzman Taveras, Ramón Fernández, Alicia Álvarez, José RA Balbín, Juan Agüero Calvo, Jaume Ferrer Sancho, Esther Rodríguez González, Eduardo Loeb, José LI Alonso, Mª AR García, Juan Abreu González, Candelaria Martín García, Rebeca Muñoz, Haydée Martín García, Miguel AM Muñiz, Andrés AS Antuña, Jesús Allende González, Jose AG Blanco, Fernando JA Navascues, Manuel AV Montes, María Rodríguez Pericacho, Concepción Rodríguez García, and Juan DA Mavárez

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by CEIm Hospital La Princesa, Madrid, Spain. Reference number 2899. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: the gold science Committee report 2019. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1900164. 10.1183/13993003.00164-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cosío BG, Hernández C, Chiner E, et al. [ translated article ] Spanish COPD guidelines (gesepoc 2021): non-pharmacological treatment update. Archivos de Bronconeumología 2022;58:T345–51. 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.08.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balasubramanian A, MacIntyre NR, Henderson RJ, et al. Diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide in assessment of COPD. Chest 2019;156:1111–9. 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kovacs G, Agusti A, Barberà JA, et al. Pulmonary vascular involvement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. is there a pulmonary vascular phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:1000–11. 10.1164/rccm.201801-0095PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2005;26:720–35. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nambu A, Zach J, Schroeder J, et al. Relationships between diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and quantitative computed tomography measurements and visual assessment for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Radiol 2015;84:980–5. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de-Torres JP, O’Donnell DE, Marín JM, et al. Clinical and prognostic impact of low diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide values in patients with global initiative for obstructive lung disease I COPD. Chest 2021;160:872–8. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Knudson RJ, Kaltenborn WT, Burrows B. The effects of cigarette smoking and smoking cessation on the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lung in asymptomatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;140:645–51. 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3.645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harvey B-G, Gordon C, Dvorak A, et al. Natural history of asymptomatic smokers with normal spirometry and reduced diffusion capacity: do they develop COPD? American Thoracic Society 2010 International Conference, May 14-19, 2010 · New Orleans; May 2010. 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2010.181.1_MeetingAbstracts.A1531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harvey B-G, Strulovici-Barel Y, Kaner RJ, et al. Risk of COPD with obstruction in active smokers with normal spirometry and reduced diffusion capacity. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1589–97. 10.1183/13993003.02377-2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neas LM, Schwartz J. Pulmonary function levels as predictors of mortality in a national sample of US adults. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:1011–8. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goel K, Beatman EL, Egersdorf N, et al. Sphingosine 1 phosphate (S1P) receptor 1 is decreased in human lung microvascular endothelial cells of smokers and mediates S1P effect on autophagy. Cells 2021;10:1200. 10.3390/cells10051200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Polverino F, Celli BR, Owen CA. Copd as an endothelial disorder: endothelial injury linking lesions in the lungs and other organs? (2017 grover conference series). Pulm Circ 2018;8 10.1177/2045894018758528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neder JA, Berton DC, Muller PT, et al. Incorporating lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide in clinical decision making in chest medicine. Clin Chest Med 2019;40:285–305. 10.1016/j.ccm.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alfageme I, de Lucas P, Ancochea J, et al. 10 years after EPISCAN: a new study on the prevalence of COPD in spain—A summary of the EPISCAN II protocol. Archivos de Bronconeumología (English Edition) 2019;55:38–47. 10.1016/j.arbr.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soriano JB, Alfageme I, Miravitlles M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of COPD in spain: episcan II. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2021;57:61–9. 10.1016/j.arbres.2020.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–51. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marín JM, et al. Prognostic evaluation of COPD patients: gold 2011 versus bode and the COPD comorbidity index COTE. Thorax 2014;69:799–804. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54. 10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Minette A. Questionnaire of the European community for coal and steel (ECSC) on respiratory symptoms. 1987 -- updating of the 1962 and 1967 questionnaires for studying chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Eur Respir J 1989;2:165–77. 10.1183/09031936.93.02020165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, et al. Usefulness of the medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54:581–6. 10.1136/thx.54.7.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Donaire-Gonzalez D, Gimeno-Santos E, Serra I, et al. Validation of the Yale physical activity survey in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Arch Bronconeumol 2011;47:552–60. 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-Ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1324–43. 10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graham BL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. Executive summary: 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2017;49:16E0016. 10.1183/13993003.E0016-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cotes JE, Chinn DJ, Quanjer PH, et al. Standardization of the measurement of transfer factor (diffusing capacity). Eur Respir J 1993;6 Suppl 16:41–52. 10.1183/09041950.041s1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories . Ats statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7. 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005–12. 10.1056/NEJMoa021322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Soriano JB, et al. Determinants of blood eosinophil levels in the general population and patients with COPD: a population-based, epidemiological study. Respir Res 2022;23:49. 10.1186/s12931-022-01965-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iyer AS, Wells JM, Vishin S, et al. Ct scan-measured pulmonary artery to aorta ratio and echocardiography for detecting pulmonary hypertension in severe COPD. Chest 2014;145:824–32. 10.1378/chest.13-1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marin-Oto M, Seijo LM, Divo M, et al. Nocturnal hypoxemia and CT determined pulmonary artery enlargement in smokers. J Clin Med 2021;10:489. 10.3390/jcm10030489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. European health interview survey (EHIS) in spain. secondary european health interview survey (EHIS) in spain. 2020. Available: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/EncuestaEuropea/Enc_Eur_Salud_en_Esp_2020.htm

- 33. Cheung T, Papanikolaou V, Finlay P, et al. Prevalence of reduced carbon monoxide transfer factor in smokers with normal spirometry. Respir Med 2021;182:106422. 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sherrill DL, Enright PL, Kaltenborn WT, et al. Predictors of longitudinal change in diffusing capacity over 8 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:1883–7. 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9812072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alcaide AB, Sanchez-Salcedo P, Bastarrika G, et al. Clinical features of smokers with radiological emphysema but without airway limitation. Chest 2017;151:358–65. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Casanova C, Gonzalez-Dávila E, Martínez-Gonzalez C, et al. Natural course of the diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide in COPD: importance of sex. Chest 2021;160:481–90. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ekberg-Jansson A, Bake B, Andersson B, et al. Respiratory symptoms relate to physiological changes and inflammatory markers reflecting central but not peripheral airways. A study in 60-year-old “ healthy ” smokers and never-smokers. Respir Med 2001;95:40–7. 10.1053/rmed.2000.0969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van der Lee I, Gietema HA, Zanen P, et al. Nitric oxide diffusing capacity versus spirometry in the early diagnosis of emphysema in smokers. Respir Med 2009;103:1892–7. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grydeland TB, Thorsen E, Dirksen A, et al. Quantitative CT measures of emphysema and airway wall thickness are related to D (L) CO. Respir Med 2011;105:343–51. 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kirby M, Owrangi A, Svenningsen S, et al. On the role of abnormal DL (CO) in ex-smokers without airflow limitation: symptoms, exercise capacity and hyperpolarised helium-3 MRI. Thorax 2013;68:752–9. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jetmalani K, Thamrin C, Farah CS, et al. Peripheral airway dysfunction and relationship with symptoms in smokers with preserved spirometry. Respirology 2018;23:512–8. 10.1111/resp.13215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Criner RN, Hatt CR, Galbán CJ, et al. Relationship between diffusion capacity and small airway abnormality in copdgene. Respir Res 2019;20:269. 10.1186/s12931-019-1237-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gajdócsy R, Horváth I. Exhaled carbon monoxide in airway diseases: from research findings to clinical relevance. J Breath Res 2010;4:047102. 10.1088/1752-7155/4/4/047102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nelson JJ, Liao D, Sharrett AR, et al. Serum albumin level as a predictor of incident coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:468–77. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Candiano G, Petretto A, Bruschi M, et al. The oxido-redox potential of albumin methodological approach and relevance to human diseases. J Proteomics 2009;73:188–95. 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gordon C, Gudi K, Krause A, et al. Circulating endothelial microparticles as a measure of early lung destruction in cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:224–32. 10.1164/rccm.201012-2061OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Elbehairy AF, Ciavaglia CE, Webb KA, et al. Pulmonary gas exchange abnormalities in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. implications for dyspnea and exercise intolerance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:1384–94. 10.1164/rccm.201501-0157OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. O’Donnell DE, Elbehairy AF, Webb KA, et al. The link between reduced inspiratory capacity and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14(Supplement_1):S30–9. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-834FR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stevens GR, Fida N, Sanz J. Computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in pulmonary hypertension. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2012;55:161–71. 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sevilla-Montero J, Labrousse-Arias D, Fernández-Pérez C, et al. Cigarette smoke directly promotes pulmonary arterial remodeling and Kv7.4 channel dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:1290–305. 10.1164/rccm.201911-2238OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dilektasli AG, Porszasz J, Casaburi R, et al. A novel spirometric measure identifies mild COPD unidentified by standard criteria. Chest 2016;150:1080–90. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.06.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tenin K, Aurélien S, Daniela M, et al. Prevalence of a decreased FEV3/FEV6 ratio in symptomatic smokers with preserved lung function. Respir Med Res 2022;81:100891. 10.1016/j.resmer.2022.100891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2022-001468supp001.pdf (173.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.