Abstract

Detention facilities in the southern US hold a large percentage of individuals detained in the US and have amassed numerous reports of medical mismanagement. The purpose of this study was to evaluate expert declarations of individuals residing in these facilities to assess the appropriateness of medical care provided. We analyzed 38 medical expert declarations from individuals in detention from 2020 to 2021. A thematic analysis was conducted to explore the management of medical conditions. Major themes include inadequate workup, management and treatment of medical conditions, psychiatric conditions, and medical symptoms. Subthemes identified include incorrect workup, failure to refer to a specialist, incorrect medications and/or treatments, missed or incorrect diagnoses, and exacerbation of chronic conditions. This study supports growing evidence of medical mismanagement and neglect of individuals while in immigration detention. Enhanced oversight and accountability around medical care in these facilities is critical to ensure the quality of medical care delivered meets the standard of care.

Keywords: ICE detention, Medical mismanagement in ICE detention, Medical neglect in ICE detentionMedical care in ICE detention

Introduction

Over the last 25 years, the number of individuals held in immigration detention facilities in the United States (US) has increased dramatically from an average daily population of 6785 in 1994 to 47,000 in 2019 [1, 2]. While detaining non-citizens in the US. has a long history, the recent expansion in immigrant detention has been fueled by multiple congressional policies and executive orders [3–5]. To date, there are over 130 active detention facilities with a daily average of 23,000 detained individuals (as high as 50,000 in 2019) [6, 7].

As the number of detained individuals has increased, civil and human rights organizations have raised concerns of substandard conditions in detention facilities across the country. Several published reports have highlighted overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions, physical and sexual abuse, inadequate nutrition, medical mismanagement, neglect, and abuse; leading to exacerbation of chronic medical conditions and/or development of new health conditions [2, 3, 8, 9]. A study evaluating deaths of individuals in ICE detention facilities demonstrated that 71 individuals died while in ICE custody over a 7-year period, many of whom were young (mean age of 42.7 years at the time of death) with no or minor pre-existing conditions [10]. Mental health care in ICE facilities has been of particular concern with suicide accounting for a number of deaths for at least 2 decades, and ongoing reports of the improper use of solitary confinement for those with mental health disorders (which in fact negatively affects physical and psychological health) [9, 11–16]. Historically, ICE has engaged in other unsafe mental health care practices including detaining individuals with significant mental health conditions despite court ordered requirements for inpatient mental health treatment [17]. Conditions in ICE facilities have been especially concerning in the setting of COVID-19, with reports of poor adherence to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 guidelines and high COVID-19 positivity rates [18, 19].

Southern detention facilities, particularly those in Georgia (GA), have been an area of concern. Notably, Irwin County Detention Center (ICDC), in Ocilla, GA, was forced to close in 2021 in response to medical abuses and failure to adhere to COVID-19 protocols [20, 21]. Investigations into medical care at this facility revealed that women had undergone reproductive related medical and surgical procedures without their consent [22, 23]. Stewart Detention Center (SDC), located in Lumpkin, GA, has been cited to have some of the worst living conditions with inadequate access to medical and psychiatric care [5, 24]. Over eight deaths have been reported at this facility since 2017, and the number of total documented COVID-19 cases to date remains one of the highest in the country [13, 25, 26]. Notably, an investigation into one of the deaths at SDC revealed significant medical neglect, multiple violations of ICE and SDC policies, and falsified documentation [13].

Despite ongoing reports of medical mismanagement in southern detention facilities, there is little transparency about the medical conditions of individuals in detention and the extent of medical mismanagement. While ICE has published National Detention Standards (NDS) to ensure the health and safety of those in detention, there is no ongoing assessment to determine the extent of adherence to these standards. Since 2019, the GA Human Rights Clinic (GHRC) has provided medical chart reviews to medically vulnerable individuals in southern detention facilities in partnership with legal partners in the south. The purpose of this study was to evaluate expert declarations, letters summarizing findings from review of medical records, of medically vulnerable individuals in detention to better describe the medical conditions, medical care provided, and the extent of medical mismanagement, neglect, and abuse. Our study is one of the first to explore the medical and psychiatric care of medically vulnerable individuals while in detention in Southern facilities with not yet fatal conditions.

Methods

Data Sources

Expert declarations were coordinated and provided by the GHRC in partnership with legal organizations. The GHRC receives referrals for medical chart reviews by the client’s legal representative. Medical records are obtained from the detention facility by their legal representative with the client’s consent. The legal team confidentially provides medical records from detention facilities, and external medical records if available, to the trained clinician(s) conducting the review. All clinicians are provided with standard training resources (see Appendix A for sample resources). After review of records, the clinician(s) objectively document medical and psychiatric conditions, workup, and management of these conditions, and assess whether the current workup and management is within the standard of care for each condition. If applicable, the clinician(s) document concerns about the provision of medical and psychiatric care and if applicable, how ongoing detention may exacerbate underlying medical and psychiatric disorders. This documentation is compiled in a letter, or expert declaration, which is sent to the legal team and is submitted with the client’s case to a judge or directly to ICE. The expert declarations included in this study were completed by board certified physicians who practice at an academic medical center. The GHRC collects and stores all expert declarations via a secure database. A total of 38 expert declarations were included in this study (21 from 2020 to 17 from 2021). Prior to the start of this study, legal representatives providing referrals were consulted regarding the use of deidentified expert declarations and reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. This study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board.

Study Approach and Analysis

We utilized thematic analysis to evaluate expert declarations as described by Braun and Clarke [27]. All expert declarations from 2020 to 2021 were de-identified by two members of the study team (AS, HG) following a redaction key (removing client and evaluator demographics, detention facility name and demographics, and any other potentially identifying information) and imported into Dedoose for coding [28]. Members of the study team reviewed all expert declarations and then developed a coding tree that was piloted and refined (AJZ, AS, HG). The developing coding tree was reviewed and edited by the entire study team. Two investigators open coded all expert declarations using the coding tree (AS, HG). Any discrepancies in codes were discussed and resolved by consensus (AJZ, AS, HG). After completion of coding, themes were generated from coded segments with major and minor themes identified that were reviewed and refined by the entire study team. Final themes and an accompanying thematic map were developed iteratively by the study team. Throughout the coding and generation of themes process, the coders met weekly (AJZ, AS, HG) and utilized a memoing approach to document changes, reflections, and discrepancies and how they were adapted. Notably, the study team has deep content expertise regarding medical and psychiatric care in ICE facilities. As such, the study team utilized reflexivity throughout the analysis process, acknowledging prior experiences and assumptions surrounding healthcare in ICE facilities to ensure preexisting knowledge and biases did not influence interpretation of data. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines were followed (see Appendix B for a completed checklist).

Results

The majority of referrals were from GA (77%) with SDC being the most common referral facility (49%). The mean age of individuals was 40.7 years, and most were men (92%). This distribution is likely due to the availability of legal representation at certain facilities (e.g., SDC). Most individuals had at least one chronic medical condition (97%) and/or psychiatric condition (45%) with many individuals having both medical and psychiatric conditions (42%). Over half of individuals (66%) had COVID-19 risk factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the study population

| Demographics (N = 38) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 35 (92) |

| Female | 3 (8) |

| Year | |

| 2020 | 21 (55) |

| 2021 | 17 (45) |

| Age (N = 29) (mean (sd)) | 40.7 (11.5) |

| Medical conditions | |

| Any medical condition | 37 (97) |

| COVID-19 Cases | 11 (29) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 12 (32) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 19 (50) |

| Risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection | 25 (66) |

| Psychiatric conditions | |

| Any psychiatric condition | 17 (45) |

| Major depressive disorder | 12 (32) |

| Both medical and psychiatric conditions (%) | 16 (42) |

| Facility location by state (N = 35) | |

| Alabama | 1 (3) |

| Florida | 1 (3) |

| Georgia | 27 (77) |

| Folkston | 7 (20) |

| Irwin | 3 (9) |

| Stewart | 17 (49) |

| Louisiana | 4 (11) |

| Mississippi | 1 (3) |

| Texas | 1 (3) |

*Missing data for age (n = 29) and facility (n = 35)

Themes

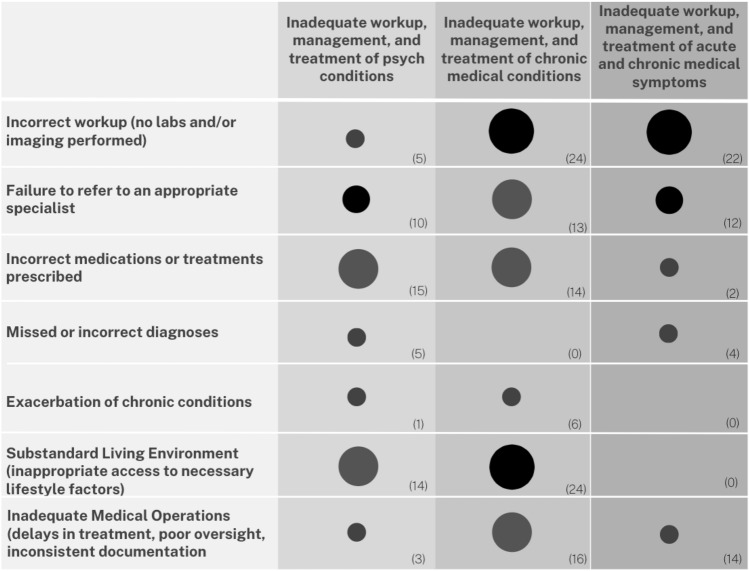

Major themes centered around inadequate workup, management and treatment of medical conditions, psychiatric conditions, and medical symptoms (Fig. 1; Table 2). There were a number of subthemes present throughout most of the major themes including incorrect workup, failure to refer to a specialist, incorrect medications and/or treatments prescribed, missed or incorrect diagnoses, and exacerbation of chronic medical conditions. Additionally, three subthemes emerged: substandard living environment, inadequate medical operations, and COVID-19 concerns.

Fig. 1.

Major and minor themes. This figure illustrates major themes (row 1) and minor themes (rows 2–8). The number of times the minor theme was identified within an expert declaration is indicated by the size of the circle. The actual number of occurrences is included in the parenthesis of each column. Small circles correspond to 1–6 occurrences, medium circles correspond to 7–12 occurrences, large circles correspond to 13–18 occurrences, and extra large circles correspond to 18–24 occurrences

Table 2.

Themes and representative excerpts

| Theme | Representative excerpts |

|---|---|

| Inadequate workup, management and treatment of pre-existing chronic medical conditions |

Incorrect treatment, failure to refer, exacerbation of chronic condition: Due to his inadequately controlled diabetes, the client has evidence of kidney damage and eye damage (also known as diabetic retinopathy). Therefore, he would benefit from further intensification of his insulin regimen and possibly other oral diabetic medications to better control his diabetes. He needs closer and more consistent follow-up and evaluation with an endocrinologist for his diabetes 2020_8 Incorrect workup, failure to refer: As he has had no evaluation by a specialist and has had several requests for refills on his inhalers he would benefit from an evaluation and consistent follow up by a pulmonologist for lung volume testing to properly evaluate for this, as this would alter the choice of inhalers to treat his lung disease. 2020_20 Incorrect treatment: However, despite multiple visits with blood pressures above goal, he was maintained on the two medications and doses he was on when he entered the facility. 2021_03 Incorrect treatment, exacerbation of chronic medical condition: Per chart review, the client has not been given additional steroid inhalers or (more importantly) oral steroids, which would be the first step in attempting to control exacerbations. Per documentation, the client’s symptoms are worsening daily with cough and chest pain, all signs of an asthma exacerbation. 2020_1 |

| Inadequate workup, management, and treatment of acute and chronic medical symptoms |

Incorrect workup: For patients who report blood in their stool, it is standard of care to perform a rectal examination and a colonoscopy to identify a cause for the bleeding. He was diagnosed with hemorrhoids and was prescribed a healing ointment. Medically, it is not possible to make the diagnosis of hemorrhoids without performing a rectal examination. Incorrect workup: Given his risk profile and chest pain it would be standard of care to check serial troponins (cardiac enzymes) and have the patient follow up with a cardiac stress test or cardiac imaging. 2021_11 Incorrect workup: his blood work from [date redacted] showed mildly elevated liver enzymes. No acknowledgement or plan was documented but care should be taken to monitor these levels 2021_19 Failure to refer to a specialist, incorrect treatment: It would be recommended for a patient who has concern for spinal injury due to persistent symptoms to have consultation with an advanced specialist including a neurosurgeon or orthopedic surgeon. The treatment he has received to date may lead to further harm as he has been given multiple prolonged courses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, meloxicam, and naproxen. 2021_16 |

| Inadequate workup, management, and treatment of a psychiatric condition |

Incorrect workup, Incorrect treatment: With such strong evidence supporting a psychotic process, the client should undergo a full psychiatric evaluation by a psychiatrist. It is standard of care to prescribe an antipsychotic medication in these cases. Mirtazapine, an antidepressant, will not adequately treat the client’s apparent psychosis. 2020_16 Incorrect workup: Given the symptoms endorsed by the client, further work up and exclusion of all medical causes is needed prior to diagnosis of pseudocyesis can be made. 2021_18 Incorrect treatment: The best evidence-based guidelines for treating Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) recommend patients receive both medication and regular psychotherapy. Using both of these modalities increases the chance for improvement of symptoms and possible recovery when compared to medication alone. Using the documentation that we have, there is no evidence that the client receives psychotherapy at an adequately recommended regular interval. 2021_12 Inappropriate medication/treatment: Based on chart review, it appears the client is not on appropriate medications for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). As per recent psychiatric medication recommendations, the medication he was given (Risperidone) is a fourth line treatment for PTSD. He has not been given access to preferred treatments including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRIs), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and trauma-focused psychotherapy, all of which are first line recommendations for PTSD. In addition, the dose of Risperidone he has been given is a subclinical dose that is likely not adequate to manage his symptoms. 2020_14 Incorrect diagnosis: Of significant concern is the improper diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). Throughout his medical record there is one instance that ASPD is mentioned [date redacted] as “concern for ASPD”. This was done without any documentation as to how the diagnostic criteria were met and no further analysis as to why there was a concern for ASPD. High levels of agitation, lack of cooperation, and intermittent verbal threats of harm were mentioned and are not diagnostic of ASPD. Many of the behaviors exhibited have many potential explanations, such as his diagnosis of PTSD, the high stress environment and uncertainty of detention, isolation, or worsening depression as described above among many other causes. 2021_2 |

| Substandard living environment |

Per chart review, the patient lifestyle in detention is sedentary (as it is difficult to find ways to get his daily exercise) and he is not able to choose from healthy food options; instead he has to “eat whatever he can get,” and whatever is made available to him. The documentation reports that he has been advised to exercise and eat healthy, but no specific help or advice has been offered, and he has limited means to implement these changes due to the confines and stress of living in detention and the lack of healthy food options available to him 2021_5 However, it is apparent that her environment in detention is working to negate these coping mechanisms, and exacerbate her mental health. From records, she reports difficulty sleeping at night due to the detention facility leaving lights on. Poor sleep hygiene will inevitably exacerbate underlying Anxiety and Depression. Further exposure to these conditions could worsen her mental health, making long term treatment and recovery more difficult. 2020_17 There are many factors leading to worsening both PTSD and depression including living environment, social isolation, lack of social support and access to adequate resources. In detention, the client does not have access to adequate social support, mental health support, or a low stress living conditions. 2021_2 |

| Inadequate medical operations |

The patient reported on [date redacted] and [date redacted] that he had pain in his stomach and pelvis. Provider documentation shows left flank pain for several days. This is a discrepancy in patient reports and provider documentation. (Shortly thereafter, this patient underwent an appendectomy for appendicitis) -2020_20 Medical records indicate he has only been evaluated by a counselor. He requires a specialized evaluation and ongoing treatment by a psychiatrist in the setting of his significant trauma and ongoing stressors. 2020_10 The client reported feeling shortness of breath on [date redacted], but did not receive appropriate treatment until 8 days later, despite having low peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) values on [date redacted] (and a history of asthma). Standard procedure is immediate initiation of albuterol when symptoms begin, which in this case did not occur, based on the medical records provided 2021_9 |

| COVID-19 |

The client reported symptoms of cough, headache, chills, shortness of breath and nasal discharge. It does not appear that COVID-19 was considered; however these symptoms are highly consistent with COVID-19. She was not isolated, monitored or tested for COVID-19 at this time. 2020_17 On [date redacted], he had a positive test. It appears the client was isolated that day but his medical records only note vital signs once daily on [date redacted]. It is highly concerning that his symptoms first started on [date redacted] yet he wasn’t isolated until over one month later, despite having an exposure and symptoms 2020_2 |

Inadequate Workup, Management, and Treatment of Pre-existing Chronic Medical Conditions

Evaluators documented multiple encounters in which the workup, management, and treatment of diagnosed chronic medical conditions were inadequate. This was defined by the subthemes of incorrect workup, failure to refer to an appropriate specialist, incorrect medications or treatments prescribed, and exacerbation of chronic medical conditions. Incorrect workup was described as a failure to order additional labs and/or imaging for a condition or only pursuing a partial workup without completing a standard workup. This also included ordering incorrect labs and/or imaging for certain conditions. There were multiple encounters in which a patient should have been referred to a specialist for a chronic medical condition but was not. Frequently, evaluators documented concerns about medications prescribed; the use of non-first line agents, use of medications that were inappropriate for the condition, initiation of medications without required follow up labs, or simply not initiating medications when appropriate to do so. There was also documentation of missing required daily medications for multiple days, excessive use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and failure to adjust medications when there was not an adequate treatment response. On several occasions, the inappropriate workup, management, and treatment of chronic medical conditions led to exacerbation of chronic medical conditions.

Inadequate Workup, Management, and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Medical Symptoms

This theme was defined by the subthemes of incorrect workup, failure to refer to an appropriate specialist, and missed or incorrect diagnoses. Evaluators documented multiple encounters in which there was a failure to initiate a workup of acute and/or chronic medical symptoms, or incomplete workup of symptoms (with no previous medical condition diagnosed related to the symptom). This was described as a failure to order additional labs and/or imaging for a condition, only pursuing a partial workup, initiating the wrong workup for a symptom, and/or failing to perform an adequate physical exam for a symptom. Additionally, patients were not referred to a specialist when appropriate for serious symptoms. As a result, patients were often not diagnosed with a medical condition and therefore unable to receive the appropriate treatment for that condition. While not directly related to a symptom, a subtheme that was also present throughout was the failure of the medical team to follow up abnormal labs and/or vitals.

Inadequate Workup, Management, and Treatment of a Psychiatric Condition

A number of subthemes emerged that define inadequate workup, management, and treatment of a psychiatric condition, including incorrect workup, failure to refer to an appropriate specialist, incorrect medications/treatments prescribed and missed or incorrect diagnoses. Evaluators documented that while patients may have seen a behavioral health specialist, the frequency of appointments was inadequate to appropriately diagnose and treat a psychiatric condition. Additionally, patients were rarely referred to a psychiatrist to assist with complex medication management and/or psychotherapy. Missed or incorrect diagnoses were common and the rationale for certain diagnoses was inadequate, and/or patients were often diagnosed with psychiatric conditions of a lesser severity than what would be consistent with the symptoms. There were a number of concerns related to the inappropriate use of psychiatric medications, defined as the use of incorrect psychiatric medications for specific conditions, use of short term psychiatric medications rather than more effective long term medications, use of non-first line agents, use of multiple non indicated psychiatric medications in combination, failure to adjust medications or escalate treatment with worsening of psychiatric symptoms, and sole use of medication without the combination of therapy. In a few cases, medical isolation was utilized as a treatment option but the details of this were not defined.

Substandard Living Environment

The substandard living environment theme arose from consistent documentation about the concerns of the environmental context of detention facilities as a whole, specifically the substandard living environment (housing, nutrition, hygiene, access to exercise). The standard of care for many medical conditions present here include lifestyle factors such as: access to appropriate nutrition/diet for managing hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, and similarly access to exercise options to manage these conditions. Evaluators documented concerns about the ability to access these necessary lifestyle changes while in detention, thus leading to challenges in management of these conditions. This was similar for those with existing or new psychiatric disorders, as detention facilities rarely constitute a therapeutic environment and patients often do not have access to a critical support system to help with management of symptoms.

Inadequate Medical Operations

This subtheme refers to medical operations provided by the facility and includes more operational aspects of adequate and effective care delivery rather than individual provider practices. This was defined as poor oversight in which there was concern that patients and conditions were being managed without appropriate physician oversight. There was also consistent documentation of delays in management and treatment, including accessing labs/imaging, referrals, and/or delays in starting required medications. Evaluators commented on inconsistencies in documentation in which a patient noted one thing which the provider did not document, and/or diagnoses that were not consistent with the symptoms/findings. Finally, there were a few occasions in which the facility failed to transfer a patient to the Emergency Department for serious symptoms or conditions.

COVID-19

Finally, as the expert declarations reviewed expand across 2020–2021, COVID-19 related data was present throughout many of the declarations. Evaluators frequently described inadequate testing, treatment, and adherence to COVID-19 guidelines, as well as highlighting individuals with one or multiple COVID-19 risk factors. There were multiple patients who had the presence of COVID-19 symptoms and/or exposures but it was unclear if they were isolated, appropriately monitored, or tested for COVID-19. Evaluators frequently documented concerns about the conditions in detention facilities as exacerbators of rapid spread of COVID-19 and the need for detention facilities to adhere to Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines.

Discussion

In this analysis, we found evidence of medical mismanagement and neglect, described as inadequate workup, management and treatment of chronic medical conditions, psychiatric conditions, and acute and chronic medical symptoms. We describe in detail the type and extent of mismanagement, as well as concerns about the operational aspects of medical care in ICE facilities and substandard conditions of ICE detention facilities that serve as barriers to achieving optimal care. Additionally, during the study period, COVID-19 exacerbated many of these factors, further stressing an already deficient system.

Prior studies have documented evidence of medical mismanagement, neglect, and abuse in ICE facilities. A review of deaths in ICE detention documented evidence of substandard care, operational concerns, and violation of ICE’s own NDS, finding substandard medical and psychiatric care described as inappropriate dosing of medications, missed diagnoses, inappropriate treatment plans for psychiatric conditions, and delays in care [10]. Another study exploring the health status of formerly detained immigrants highlights similar findings including delays in medical care while in detention, exacerbation of chronic medical conditions, and worsening of psychiatric conditions [9]. These findings are not surprising considering the structure of medical services in ICE facilities was designed for short lengths of stay and acute care services. However, many individuals remain in ICE facilities for months to years with limited support for chronic diseases and preventative health [29]. Additionally, suicide has remained a common cause of death for individuals in ICE detention since 2003 with a significantly increased suicide rate noted in 2020 [11, 12, 14]. This recent time period (2020) overlaps with our study period and aligns with numerous themes suggesting inadequate management of psychiatric conditions and concerns regarding the environment of ICE facilities that exacerbate psychiatric conditions.

Our results are particularly concerning when placed into context of immigration and carceral structures and practices in Southern states like GA due to the large population of detained individuals, with SDC holding the highest number of individuals in the state and country in 2022 (averaging 1086 per day) [7, 30]. Since 2012, several civil rights organizations have published multiple investigations at GA detention facilities revealing limited oversight or accountability and highlighting inadequate medical care, yet minimal improvements have been implemented [5, 24]. Additionally, detention facilities that are dedicated Inter-governmental Service Agreement (IGSA) facilities, those that solely house ICE detainees, have been found to have higher death rates than all other settings where individuals detained reside [14, 31]. All three detention facilities in GA, SDC, ICDC and Folkston ICE Processing Centre, are/were IGSA dedicated facilities. With a large, detained population and extensive documentation of medical mismanagement in Southern detention facilities, supported by our findings here, it is critical that greater oversight of medical care is implemented in ICE facilities at both state and federal levels.

One component of oversight could be independent external and routine evaluation of medical care in ICE facilities to assess adherence to ICE’s own NDS. Additionally, enhanced transparency around medical care in detention facilities is critical as it is extremely challenging to access information about medical operations, medical staffing, and health outcomes of individuals in detention. ICE facilities should be held accountable for reporting specific health outcomes data and adhering to medical operations requirements. This could include providing appropriate and timely referrals for specific conditions, ensuring access to labs, imaging, and medications that are condition appropriate, providing recommended nutrition regimens for those with chronic conditions, improvements in medical staffing, and prohibiting the use of solitary confinement.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Our sample was limited only to those who had legal representation and a referral by their legal representative, and only for those who were identified by their legal teams as being medically vulnerable. This may have missed those without legal representation or not identified as medically vulnerable. There may also be sampling bias as we only included individuals with potentially more severe medical conditions or with multiple comorbid conditions. Given the logistical challenges of confidentially storing medical records, we were only able to utilize secondary data from expert declarations rather than review of primary data (medical charts) which introduces bias, including bias from the objective reviewer. While clinicians who conduct chart reviews and subsequently write Expert Declarations are meant to be objective reviewers and are provided with education/templates for objective review, they may introduce their own biases when reviewing and documenting perceived standards of care. Additionally, our study has a small sample size and is geographically restricted to the South with the majority of expert declarations conducted for clients residing in GA detention facilities, limiting generalizability. Finally, we recognize that it is difficult to assess whether the care provided is inadequate because of individual provider factors or facility specific factors. We are cognizant to avoid criticizing individual practices of clinicians as they may be limited by their setting rather than intrinsic factors, and medical staff previously have played an important role in accountability.

Conclusion

This data supports the need to closely examine the medical ethics and medical rights of individuals in detention facilities. If these facilities are unable to uphold the standard of care expected at non-detention medical facilities, closure and discontinued use of ICE facilities may be the only acceptable option. As clinicians and public health experts, it is essential that we continue to advocate for accountability, transparency, and closure of facilities if ICE cannot ensure the delivery of quality medical care to all individuals.

Appendix A

Purpose: The purpose of the letter is to review medical records, identify medical problems, and comment on whether the medical problems are being managed appropriately. The letter is meant to be as objective as possible. The audience is the judge. This is why it is important that the letter be unbiased and objective. Demonstrating unmet medical needs, or how detention may exacerbate medical conditions, may help an individual be released on bond.

Strategy: The general strategy is to (1) review the records (2) identify medical problems (ex. diabetes) (3) how they were diagnosed in the detention facility (ex. Hemoglobin A1c) (4) what current treatment strategy and workup they have had and (5) general background about the disease in general including complications (6) comment on whether or not the management is appropriate including if they have seen appropriate specialists, medication management, therapy, etc. (7) If management is not appropriate, comment on what additional management is needed. (8) If applicable comment on how ongoing detention may exacerbate specific medical conditions.

Sample Expert Declaration (De-identified)

Date

Hon. Immigration Judge X.

U.S. Department of Justice.

X Immigration Court.

XXX address.

Re: XXXXXXXX.

Agency Number: XXXXX.

DOB: XXXXX.

Dear Hon. Judge X.

I am writing on behalf of [client name] to draw attention to the health care services provided to them by Immigrant and Customs Enforcement at XX Processing Center. Our conclusions and medical recommendations are based on review of the available medical records.

I, [evaluator name], am a licensed physician in the state of XX. [Include additional titles and qualifications of evaluator].

Per chart review, [client name] suffers from several medical conditions that require close monitoring including hypertension and acute stress disorder. Without appropriate medical attention [client name] is at risk of suffering both acute and chronic complications.

Hypertension

Per chart review, it appears [client name] was first noted to have symptomatic hypertension on 01/28/2020 with severe headaches, flushing, and a blood pressure reading of 180/116 with minimal reduction of his/her blood pressure despite medication administration. He/she continued to have elevated blood pressure despite treatment and eventually had a seizure-like episode with a blood pressure of 208/111 on 01/30/2020 for which the patient was appropriately taken to the emergency department. A change in mental status in conjunction with high blood pressure is concerning for medical conditions such as PRES (Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome) due to brain edema, hypertensive encephalopathy, or stroke. Although the patient received head imaging with a CT scan of his/her head, in order to appropriately rule out the above medical conditions a brain MRI, EEG, and a neurology consult is indicated. A CT scan alone cannot rule out the above conditions. The patient did not undergo the additional workup within the emergency department or upon discharge. Additionally, the patient was not admitted, but instead was discharged on two blood pressure medications and was told to follow a low sodium diet. Uncontrolled hypertension can have severe medical complications including heart failure, stroke, heart attack, brain hemorrhage, or chronic kidney disease. To properly treat hypertension, it is recommended to have a blood pressure cuff for daily self-readings, encourage physical activity daily to promote weight loss, and adhere to a modified diet with salt restriction which has been proven significantly to reduce blood pressure. Per chart review, it does not appear the patient was provided with any of the above nonpharmacologic therapy. Medications are an appropriate adjunct to nonpharmalogical therapy and were provided to [client name]. However, the two medications hydrochlorothiazide and lisinopril can cause major electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hyponatremia which can in turn lead to confusion or life-threatening heart arrhythmias. To ensure these medications are given safely routine labwork, initially every 1–2 weeks, is necessary to monitor these electrolytes. It does not appear that [client name] underwent regularly labwork to evaluate for this, which is standard of care when initiating these blood pressure medications. Subsequently, the patient was also noted to have low blood pressure readings on several occasions with the lowest of 95/48 on 02/09. These labile blood pressures may be concerning for either over treatment of his/her hypertension or other secondary causes of hypertension including thyroid problems, sleep apnea, or genetic causes such as primary aldosteronism and pheochromocytoma. All of these secondary etiologies can cause high blood pressure and require specific labwork and imaging. It is standard of care to undergo this workup with labwork and imaging for individuals with poorly controlled hypertension and/or labile blood pressure. It does not appear that [client name] has received this workup.

Acute Kidney Injury

There are many causes of acute kidney injury, which is defined by an elevation in creatinine. Causes include but are not limited to dehydration, uncontrolled hypertension, medication side effects, intrinsic kidney pathology, or obstructive diseases such as kidney stones. [client name] was noted to have an elevated and abnormal creatinine of 1.3 on 11/2019 which is suggestive of compromised kidney function. In patients with elevated creatinine, it is standard of care to recheck within one week and explore etiologies of acute kidney injury with additional labwork, urine studies, and often an ultrasound of the kidneys. [client name] did not undergo repeat testing of his/her creatinine while in detention. His/her creatinine was checked in the emergency department where it was found to be slightly lower at 1.1 but still borderline high. If not addressed properly acute kidney injury can progress to chronic kidney disease which has many severe medical ramifications. Kidney disease can also cause blood pressure lability and lethal electrolyte abnormalities. Additionally, addressing abnormal blood pressure (both high and low) is essential in individuals with kidney disease.

Acute Stress Reaction

[client name] was noted to have been diagnosed with acute stress reaction on 01/30/2020 prior to being taken to the hospital. In patients with mental health conditions, access to a counselor is paramount. It appears [client name] does have access and has been treated by a counselor while in detention. Equally important in management of acute stress is ensuring patients have access to a safe and non-threatening environment, with close monitoring to watch for signs of deterioration. When [client name] returned from the emergency department he/she was placed in “medical segregation” for two weeks. There is no literature to support isolation is a beneficial practice for patients with physical or mental health issues. In fact, isolation has been noted to exacerbate underlying mental health conditions including PTSD or anxiety. It is extremely concerning that [client name] was placed under medical isolation upon return from the Emergency Department given both his/her medical and psychological diagnoses. Under no circumstances should an individual with medical needs be placed under isolation, especially considering the incomplete workup [client name] received while in the Emergency Department. This is especially concerning as [client name] could have undergone another episode of hypertensive emergency/encephalopathy while under isolation as stressful environments can exacerbate underlying medical conditions like hypertension. The results of this could have been detrimental and irreversible.

[client name] has a number of medical conditions that require close monitoring and testing. It appears he/she has had an incomplete workup and treatment of his/her current medical conditions. To remain in detention without appropriate testing and management poses a threat to his/her physical and mental health. If you have any questions or would like to discuss the case further, I can be reached at XXXXXXXXXX.

Sincerely,

[Evaluator Name]

Appendix B

See Table 3.

Table 3.

Standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR)

| Topic & Number | Response |

|---|---|

| Title & Abstract | |

|

S1 Title Concise description of the nature and topic of the study, identify study as qualitative or indicate approach |

The topic of the study is described concisely and the approach is included. |

|

S2 Abstract Summary of key elements of the study using the abstract format |

Summary of key elements of the study are included in the abstract in the format of the intended publication. |

| Introduction | |

|

S3 Problem formulation Description and significance of the problem studied, review of relevant theory and empirical work; problem statement |

Description of the problem studied is described, prior work included, problem statement clearly stated. |

|

S4 Purpose or research question Purpose of the study and specific objectives or questions |

Purpose of the study and questions to be addressed are clearly stated. |

| Methods | |

|

S5 Qualitative approach and research paradigm Qualitative approach and guiding theory if appropriate; identifying the research paradigm; rationale |

A thematic analysis approach was used as described by Braun and Clark given the nature of the data. This methodology offers a six-stage flexible approach to understand, describe and interpret often large amounts of complex data in order to develop insights about experiences centered around a particular question (here, medical management in detention). |

|

S6 Researcher characteristics and reflexivity Researcher’s characteristics that may influence the research |

As noted in the methods, the study team has deep content expertise regarding medical and psychiatric care in ICE facilities. In order to ensure objectivity, we utilized reflexivity throughout the analysis process to acknowledge prior experiences and assumptions pertaining to healthcare in ICE facilities in order to ensure pre existing biases did not influence interpretation of the data. |

|

S7 Content Setting/site and salient contextual factors; rationale |

A description of the data used was provided and the rationale for why using this data was appropriate to answer the study question is clearly stated. |

|

S8 Sampling Strategy How and why research participants, documents or events were selected; criteria for deciding when no further sampling was necessary; rationale |

Rationale for use of study documents was provided. Expert declarations highlight objective medical conditions and management, which directly answers the study question regarding the medical care of individuals while in detention. There is no formal recommendation for sample saturation in this context however no further sampling was possible. |

|

S9 Ethical issues pertaining to human subjects Documentation of approval by an appropriate ethics review board and participant consent or explanation for lack thereof; other confidentiality and data security issues |

This study was reviewed and approved by the institution’s IRB. |

|

S10 Data collection methods Types of data collected; details of data collection procedures including (as appropriate) start and stop dates of collection and analysis, iterative process, triangulation of methods/sources, modification of procedures in response to evolving study findings; rationale |

The data collected in this study includes expert declarations, letters detailing objective review of primary medical records. We describe the referral source (legal representatives), components of clinician review (including standardized resources in the appendix), and time period of the expert declarations reviewed (2020–2021). |

|

S11 Data collection instruments and technologies Description of instruments and devices used for data collection; if/how instruments changed over the course of the study |

No study instruments were used for this study but we describe the type of data collected, expert declarations, and the components of the declarations (including providing a standardized template used by clinicians in the appendix). |

|

S12 Units of Study Number and relevant characteristics of participants, documents or events included; level of participation (could be in results) |

The number of expert declarations is reported (38 total) and the demographics of the study population are included in the results (Table 1). |

|

S13 Data processing Methods for processing data prior to and during analysis, including transcription, data entry, data management and security, verification of data integrity, data coding, and de-identification of excerpts |

All declarations are stored in an institutionally sponsored secure database used by the Georgia Human Rights Clinic. Processing of the data (expert declarations) required de-identification of all expert declarations using a redaction key (removing client and evaluator demographics, detention facility name and demographics, and any other potentially identifying information). De-identified declarations were stored in a separate secure database and labeled with a unique Study ID. De-identified declarations were imported into dedoose for coding and analysis. |

|

S14 Data Analysis Process by which inferences, themes, etc. were identified and developed, including the researchers involved in the data analysis; usually references a specific paradigm or approach; rationale |

A thematic analysis approach (as described by Braun and Clarke) was utilized. Members of the study team reviewed all expert declarations and then developed a coding tree that was piloted and refined (AJZ, AS, HG). The developing coding tree was reviewed and edited by the entire study team. Two investigators open coded all expert declarations using the coding tree (AS, HG). Any discrepancies in codes were discussed and resolved by consensus (AJZ, AS, HG). After completion of coding, themes were generated from coded segments with major and minor themes identified that were reviewed and refined by the entire study team. Final themes and an accompanying thematic map was developed iteratively by the study team. |

|

S15 Techniques to enhance trustworthiness Techniques to enhance trustworthiness and credibility of data analysis (e.g., member checking, audit trail, triangulation); rationale |

Throughout the coding and generation of themes process, the coders met weekly (AJZ, AS, HG) and utilized a memoing approach to document changes, reflections, and discrepancies and how they were adapted. Notably, the study team has deep content expertise regarding medical and psychiatric care in ICE facilities. As such, the study team utilized reflexivity throughout the analysis process, acknowledging prior experiences and assumptions surrounding healthcare in ICE facilities to ensure preexisting knowledge and biases did not influence interpretation of data. |

| Results/Findings | |

|

S16 Synthesis and interpretation Main findings (e.g. themes); might include development of a theory or model or integration with prior research or theory |

Major themes identified include inadequate workup, management and treatment of medical conditions, psychiatric conditions, and medical symptoms. Subthemes identified within major themes include incorrect workup, failure to refer to a specialist, incorrect medications and/or treatments prescribed, missed or incorrect diagnoses, and exacerbation of chronic medical conditions; and substandard living environment, inadequate medical operations, and COVID-19 concerns. |

|

S17 Links to empirical data Evidence (e.g. quotes, field notes, text excerpts) to substantiate analytic findings |

Table 2 includes representative excerpts from expert declarations to support findings; Fig. 1 highlights themes identified. |

| Discussion | |

|

S18 Integration with prior work, implications, transferability and contributions to the field Short summary of main findings; explanation of how findings and conclusions connect to, support, elaborate on, or challenge conclusions of earlier scholarship; discussion of scope of application/generalizability; identification of unique contributions to scholarship in a discipline or field |

A summary of the main findings are provided in the discussion, as well as how these findings fit within the context of previous studies exploring medical care in detention facilities. Unique contributions and implications are discussed. |

|

S19 Limitations Trustworthiness and limitations of findings |

We highlight a number of limitations in the discussion. |

|

S20 Conflicts of interest Potential sources of influence or perceived influence on study conduct and conclusions; how these were managed |

In the methods, we highlight the prior experience and potential assumptions of authors, and how we used reflexivity to maintain objectivity during the analysis. |

|

S21 Funding Sources of funding and other support; role of funders in data collection, interpretation, and reporting |

This study was unfunded. |

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amy J. Zeidan, Email: ajzeida@emory.edu

Harrison Goodall, Email: harrison.malone.goodall@emory.edu.

Andrew Sieben, Email: andrew.j.sieben@emory.edu.

Parveen Parmar, Email: Parveen.Parmar@med.usc.edu.

Elizabeth Burner, Email: elizabeth.burner@med.usc.edu.

References

- 1.Moinester M. Beyond the border and into the heartland: spatial patterning of U.S. immigration detention. Demography. 2018;55(3):1147–93. doi: 10.1007/s13524-018-0679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Migration Studies. Immigration detention: recent trends and scholarship [internet]. https://cmsny.org/publications/virtualbrief-detention/ (2018). Accessed 15 Nov 2022.

- 3.Silverman SJ. Immigration detention in America: a history of its expansion and a study of its significance. COMPAS Working Paper. 2010;(80):1–31.

- 4.Saadi A, Young ME, Patler C, Estrada JL, Venters H. Understanding US immigration detention: reaffirming rights and addressing social-structural determinants of health. Health Hum Rights. 2020;22(1):187–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penn State Law Center for Immigrants’ Rights and Project South. Imprisoned Justice: Inside Two Georgia Immigrant Detention Centers [Internet]. http://projectsouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Imprisoned_Justice_Report-1.pdf (2017). Accessed 10 March 2022.

- 6.Meyer JP, Franco-Paredes C, Parmar P, Yasin F, Gartland M. COVID-19 and the coming epidemic in US immigration detention centres. Lancet. 2020;20(6):646–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30295-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Detention Management: Detention Statistics [Internet]. https://www.ice.gov/detain/detention-management (2022). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 8.Villalobos JD. Promises and human rights: the Obama administration on immigration detention policy reform. Race Gend Cl. 2011;18(1):151–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hampton K, Mishori R, Griffin M, Hillier C, Pirrotta E, Wang NE. Clinicians’ perceptions of the health status of formerly detained immigrants. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12967-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmar P, Ross M, Terp S, Kearl N, Fischer B, Grassini M, Ahmed S, Frenzen N, Burner E. Mapping factors associated with deaths in immigration detention in the United States, 2011–2018: a thematic analysis. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2021;2:100040. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terp S, Ahmed S, Burner E, Ross M, Grassini M, Fischer B, Parmar P. Deaths in immigration and customs enforcement (ICE) detention: FY2018–2020. AIMS Public Health. 2021;8(1):81–9. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2021006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erfani P, Chin ET, Lee CH, Uppal N, Peeler KP. Suicide rates of migrants in United States immigration detention (2010–2020) AIMS Public Health. 2021;8(3):416–20. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2021031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olivares J, The Intercept. ICE review of immigrant’s suicide finds falsified documents, neglect and improper confinement [Internet]. https://theintercept.com/2021/10/23/ice-review-neglect-stewart-suicide-corecivic/ (2021). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 14.Granski M, Keller A, Venters H. Death rates among detained immigrants in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(11):14414–9. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121114414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General. ICE Needs to Improve its Oversight of Segregation Use in Detention Facilities [Internet]. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2021-10/OIG-22-01-Oct21.pdf (2021). Accessed 15 Nov 2022.

- 16.Strong JD, Reiter K, Gonzale G, Tublitz R. The body in isolation: the physical health impacts of incarceration in solitary confinement. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0238510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venter H, Keller AS. Diversion of patients with mental illness from court-ordered care to immigration detention. Psychiatry Serv. 2012;63(4):377–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erfani P, Lee C, Uppal N, Peeler KR. A systematic approach to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in immigration detention facilities. Health Affairs Blog [Internet]. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200616.357449/full/#:~:text=Mass%20testing%20is%20the%20most,and%20spread%20of%20the%20pandemic (2020). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 19.Erfani P, Uppal N, Lee CH, Mishori RPK. COVID-19 testing and cases in immigration detention centers, April-August 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(2):182–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Project South. Lack of Medical Care, Unsafe Work Practices, and Absence of Adequate Protection against COVID-19 for Detained Immigrants and Employees Alike at the Irwin County Detention Center [Internet]. https://projectsouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/OIG-ICDC-Complaint-1.pdf (2020). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 21.United States Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General. Medical Processes and Communication Protocols Need Improvement at Irwin County Detention Center [Internet]. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2022-01/OIG-22-14-Jan22.pdf (2002). Accessed 15 November 2022.

- 22.Ghandakly EC, Fabi R. Sterilization in US immigration and customs enforcement’s (ICE’s) detention: ethical failures and systemic injustice. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(5):832–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Senate Staff Report. Medical Mistreatment of Women in ICE Detention [Internet]. https://aboutbgov.com/5Hw (2022). Accessed 15 Nov 2022.

- 24.Detention Watch Network. Stewart Detention Center: Expose and Close [Internet]. https://www.detentionwatchnetwork.org/sites/default/files/reports/DWN%20Expose%20and%20Close%20Stewart.pdf (2012). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 25.United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ICE Guidance on COVID-19: ICE Detainee Statistics [Internet]. https://www.ice.gov/coronavirus (2022). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 26.American Immigration Lawyers Association. Deaths at Adult Detention Centers [Internet]. https://www.aila.org/infonet/deaths-at-adult-detention-centers (2021). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 27.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dedoose V. 9.0.17. Web application for managing, analyzing and presenting qualitative and mixed methods research data [Intenet]. https://www.dedoose.com/ (2021). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 29.Venters HD, Keller AS. The immigration detention health plan: an acute care model. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(4):951–7. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freedom for Immigrants. Detention by the Numbers [Internet]. https://www.freedomforimmigrants.org/detention-statistics (2022). Accessed 10 Mar 2022.

- 31.United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement. 2011 Operations Manual ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards [Internet]. https://www.ice.gov/detain/detention-management/2011 (2011). Accessed 15 Nov 2022.