Abstract

The extent to which basic medical research is translated into clinical practice is a topic of interest to all stakeholders. In this study, we assessed the clinical translation intensity of papers published by scientists who have made outstanding contributions to the field of basic medicine (Lasker Prize winners for Basic Medical Research). Approximate Potential for Translation (APT), Translational science scores (TS), and Citations by clinical research (Cited by Clin.) were analyzed as dependent variables. A traditional citation indicator was used as a reference (relative citation ratio, RCR). In order to examine the correlation between these different indicators and the characteristics of the paper, the author, and the institution. we used nonparametric tests, Spearman correlations, ordinal least squares regressions (OLS), quantile regressions, and zero-inflated negative binomial regression methods. We found that among the basic medical research papers published by Lasker Basic Medicine Award winners, (1) 20% are cited by clinical research; 11.6% of the papers were more valuable for clinical research than basic research; 12.8% have a probability of more than 50% to be cited in future clinical studies; (2) Spearman correlations were conducted among APT, TS, Cited by Clin., RCR, and all of the other continuous variables. There is a significant, positive, low to moderate correlation between APT, TS, and Cited by Clin (APT and TS: r = 0.549, p < 0.01; APT and Cited by Clin: r = 0.530, p < 0.01; TS and Cited by Clin: r = 0.383, p < 0.01). However, the relationship between RCR and the three indicators of clinical translation intensity was not consistent. APT was positively correlated with RCR (r = 0.553, p < 0.01). Cited by Clin. is weakly positively correlated with RCR (r = 0.381, p < 0.01). There is almost no correlation between TS and RCR (r = 0.184, p < 0.01). (3) Publication age, primary research paper, multidisciplinary science, number of disciplines, authors, institutions, funded projects, references, length of the title, length of paper, physical age, gender, nationality, institutional type, Nobel Prize have a significant relationship with 1 to 3 types of clinical translation intensity measures. In a sample of basic medical research papers published by the world’s top scientists in basic medicine, we came to the following conclusions: the three indicators, APT, TS and Cited by Clin., measured the clinical translation intensity of the papers from different perspectives. They are both related to each other and have their own characteristics. In a sample of basic medical research papers published by the world’s top scientists in basic medicine, characteristics at the paper, winner, and institution level significantly correlated with the measures of clinical translation intensity. Gender effect on the clinical translation intensity of papers was confirmed. Traditional citation-based indicators and translational-focused indicators measure academic impact and clinical impact respectively. There is a certain degree of disconnect between them. Two types of indicators should be used in combination in future assessments of basic medical research.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11192-023-04634-4.

Keywords: Clinical translation intensity, Approximate potential to translate (APT), Translational science score (TS score), Basic medical research, Lasker Prize, Impact assessment

Introduction

The goal of medical research is to improve the quality of health care worldwide and improve people’s health. It has become one of the most difficult and challenging goals of medicine to translate basic research findings into clinical practice (Honey, 2007). The long lag between the initial basic research discovery and the ultimate clinical practice is usually measured in decades (Beierlein et al., 2017; Spector et al., 2018). The reason is the inherent barrier between basic medical research and drug development, clinical research, and public health practice (Morris et al., 2011).

Recognizing this challenge, many researchers, institutions, and governments have made substantial efforts to break down this barrier and build a bridge between basic research and clinical practice. Dr. Choi proposed a concept called “from bench to bedside” in 1992 (Choi, 1992). Shortly after this, the concept of “translational medicine” gradually took shape and was first introduced by Geraghty in the Lancet in 1996 (Geraghty, 1996). Since it was formally proposed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) of the United States in 2003, translational medicine has attracted more and more attention from medical circles around the world (Zerhouni, 2003). As a science, translational medicine can fill the gap between basic medical theory and clinical practice. It can help to achieve new breakthroughs in medicine, and better serve people’s health by promoting the translation of scientific research results into the industry. In recent years, significant progress has been made in the field of cancer immunotherapy, epidemic prevention and etc. In particular, since the outbreak of COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccine technology has made remarkable progress from development to clinical application and popularization.

According to the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), “translation” refers to the process of changing medical practice and behavior through the translation of lab-generated research results into interventions that can improve the health of individuals and the public (Han et al., 2018). Translation includes a series of multi-stage knowledge flows, and the scientific outputs generated at each stage are naturally endowed with corresponding clinical value. In short, translation refers to the flow of knowledge from basic scientific findings found in a laboratory setting into clinical practice (potential treatments for a disease).

The extent to which knowledge from basic medical research is transferred to clinical application is an ongoing topic of concern for all stakeholders. Over the years, this evaluation object has been expressed in many forms. For example, Narin called it the “Research Level” which ranged from the most applied (clinical observation) to the most fundamental (basic biomedical research) (Narin et al., 1976). Weber developed the term “translational index (The position of one or more articles when projected onto the translational axis)” (Weber, 2013); The word most frequently mentioned is the number of citations of papers cited by clinical trials or clinical guidelines (Andersen, 2013; Grant et al., 2000; Thelwall & Kousha, 2016). However, there is no uniform term to describe the objects being measured. Li and Tang developed a bibliometric indicator called “translation intensity” (Li & Tang, 2021) to quantify the result of a drug research’s translation, which is based on “Approximate Potential to Translate (APT)” (Hutchins et al., 2019). Inspired by Li’s study, we proposed a concept that we named “clinical translation intensity”, which collectively refers to the intensity or level at which basic medical research findings in a paper are translated into clinical applications.

What quantitative indicators have been developed to measure clinical translation intensity? It is believed that if original articles in basic medicine are cited in clinical trials, clinical guidelines, and other clinical studies, it marks the transfer or flow of knowledge generated in basic medical research to clinical research and clinical application (Andersen, 2013; Eriksson et al., 2020; Grant et al., 2000; Kryl et al., 2012; Lewison & Sullivan, 2008; Thelwall & Kousha, 2016; Thelwall & Maflahi, 2016). In recent years, some scholars have developed relatively novel quantitative indicators to evaluate and predict the clinical translational intensity of articles in basic medicine. We will review the previous literature on the measurement and tools of clinical translation intensity and conduct exploratory empirical research on the newly designed indicators.

The Albert Lasker Medical Research Award is one of the top prizes in physiology and medicine in addition to the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The Lasker Awards, which began in 1945, are awarded in four categories: Basic Medical Research Award, Clinical Medical Research Award, Special Achievement Award in Medical Science, and Public Service Award. The Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards honor scientists, physicians, and public service personnel who have made outstanding contributions to the understanding, diagnosis, treatment, cure, or prevention of human disease.

In recent years, Lasker Prize-related research has focused on the distribution of significant medical research achievements of previous Lasker prize winners (Gray et al., 2019; Littman, 2015; Miller & Su, 2011; Yancopoulos, 2010). Charlton used the Lasker Prize for Clinical Medicine, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the Gairdner Prize as representative awards in the field of medicine to evaluate and compare the contributions of countries and institutions to revolutionary biomedicine from 1987 to 2006 (Charlton, 2007a, 2007b). Nevertheless, there is a lack of quantitative analysis of the relationship between the characteristics of papers and winners and their impact.

The Lasker Basic Medical Research Award has been hailed as a bellwether for the Nobel Prize. From 1946 to 2019, 88 Lasker Laureates received the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine, including 77 Lasker Laureates in Basic Medicine (49% of the 157 Lasker Prize winners in Basic Medicine). In this study, we selected articles authored by Lasker Basic Medical Prize winners as research samples for the following two reasons: Firstly, The Lasker Prize for Basic Medicine is awarded to distinguished contributors in the field of basic medicine and, as a result, their published papers are biased towards basic medical topics. The separation of the Lasker Award for Basic Medicine and the Lasker Award for Clinical Medicine enables us to better target high-quality papers authored by outstanding basic medicine scientists in the field of basic medicine. Secondly, the intensity to which these outstanding achievements in basic medicine have been translated into clinical research and clinical practice since the paper was published is unknown. In other words, the intensity of knowledge transferred from basic medical research papers to clinical practice along the translational continuum is worth exploring.

Backward citations of published clinical studies are mostly used to measure the clinical translation intensity of the cited papers. In 2019, Hutchins developed an indicator called “Approximate Potential to Translate (APT)” based on a machine-learning algorithm to predict translational progress in biomedical research at the article level (Hutchins et al., 2019). In 2020, Kim proposed a novel bibliometric indicator named “Translational Science score (TS score)” to capture the translational degree of focal articles in basic medicine (Kim et al., 2020). NIH iCite also reports the number of clinical citations to a paper which is called Cited by Clin. in 2016 or so. These three quantitative evaluation indicators of clinical translation intensity have rarely been empirically studied since they have just been developed.

In this paper, three indicators (APT, TS and Cited by Clin.) were used to evaluate the clinical translation intensity of basic medical research papers published by the world’s top scientists in the field of basic medicine, aiming to achieve the following three research objectives:

The overall clinical translation intensity of basic medical research papers published by Lasker Prize winners in Basic Medicine and their changing trend with publication age.

Among the characteristics of the paper, the author, and the institution, which factors show an effect on the clinical translation intensity of basic medical research papers published by Lasker Prize winners for Basic Medicine?

Correlation among clinical translation intensity and traditional citation indicators of basic medical research papers published by Lasker Prize winners for Basic Medicine.

Literature review

Studies on the models of translational research stages

To better understand translational research, scholars have put forward a variety of models depicting the characteristics of translational research stages. There is no doubt that “from bench to bedside” is the prototype of the 1 T model (Choi, 1992). The 1 T model focuses on the interface between basic medicine and clinical medicine. It refers to the translation of knowledge generated in basic science into novel ways of preventing, diagnosing, and treating disease. Since 2000, the US Congress has shown concern regarding the disconnection between basic science and the delivery of better health (Woolf, 2008). The Institute of Medicine regularly organized clinical research roundtables and identified two major barriers to translation. Sung visually represented a two-phase model (Sung et al., 2003). The first phase (T1) is the translation from basic biomedical research to human studies and the second phase (T2) is the translation of new clinical knowledge into clinical practice and health decision-making. In 2007, Westfall et al. developed a three-stage translational research model by splitting Sung et al.’s T2 stage into two distinct stages with “practice-based research” as the interface (Westfall et al., 2007). In Westfall et al.’s T2 phase, knowledge transfers from phase I and II clinical trials to phase III and IV clinical trials through developing the clinical guideline, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. The “practice-based research” interface is a crucial transition interface (translations to patients) where happens a massive shift in the continuum from basic research to clinical practice and a critical leap was made from individual clinical study knowledge to more comprehensive general knowledge across different studies. In addition, different versions of the more complicated three-stage translation model (Dougherty & Conway, 2008), four-stage translation model (Khoury et al., 2007), and five-stage translation model (Surkis et al., 2016) have been proposed successively.

Studies on the classification of translational publications by “research level”

In 1976, Narin examined the journal interrelations in biomedical articles and put forward the concept of “Research Level” to classify over 900 biomedical journals into four Research Levels ranging from clinical observation to clinical mix, clinical investigation, and basic biomedical research (Narin et al., 1976). The most applied is clinical observation and the most fundamental is basic biomedical research. However, Narin’s “Research Level” classification method has certain limitations. For example, it doesn’t fit the journal’s research direction. In addition, it does not apply to journals from other databases in addition to the “Science Citation Index”; “Research Level” for papers in a journal is unique and is not assigned according to the research direction of the paper.

Lewison and Paraje extended the “Research Level” to the Medline database (Lewison & Paraje, 2004). They calculated the proportion of only clinical research papers, only basic research papers, and both clinical and basic research papers in biomedical journals based on the “basic” and “clinical” title lists, and assigned weighted coefficients of 1, 4, and 2.5, respectively, to obtain the RLcalc score. According to the RLcalc score, journals are assigned to the corresponding “Research Level”. Boyack developed a “Research Level” classification model for individual article-level, using multinomial logistic regression to train the model by extracting word texts from the title words, abstract words, and references, and to achieve the “Research Level” classification of more than 25 million papers in all disciplines in the Scopus database (Boyack et al., 2014). Compared with previous journal-level models, this article-level model has the advantage that it can be used to classify articles in any discipline and any database, regardless of whether the articles are published in SCI journals or biomedical journals. Surkis et al. created a list of definitions for each stage from T0 to T4 in the translational research spectrum proposed by CTSA and then identified and classified translational studies based on the titles, abstracts, and complete MeSH terms associated with publications using the Bayesian logistic regression algorithm (Surkis et al., 2016). Ke defined MeSH terms related to cells, molecules, and animals as basic research terms, and MeSH terms related to humans as applied terms (Ke, 2020). Next, he obtained a translational axis by learning vector representation of the MeSH terms (Ke, 2019). Then he used the representation learning method to obtain the vector representation of the MeSH terms of the paper, calculated the cosine similarity between the MeSH word vector and the translational axis vector, and assigned a “Level Score” (LS) to each MeSH term of each paper. The LS score for a paper is the average of LS for all MeSH terms of the paper. LS is a continuous variable used to identify translational science through embeddings of controlled vocabularies. Different from the previously developed “Research Level” indicator, LS can avoid classifying all papers into the same predefined “Research Level”. LS is capable of capturing more subtle differences in papers with different intensities of translation within the same “Research Level” identified.

Studies on identifying translational science within the triangle of biomedicine

Weber proposed a new way to quantify the “Research Level” using MeSH terms (Weber, 2013). Weber divided biomedical papers into seven categories based on whether they incorporated MeSH terms related to cells/molecules (C), animals (A), and humans (H). If only one of the MeSH terms such as animals (A), cell/molecular (C), and human (H) is included in one paper, it is classified as A, C, or H, respectively. When one paper includes both animal (A) and cell/molecular (C) related MeSH terms, it is classified as AC; Papers that include both animal (A) and human (H) related MeSH terms are classified as AH; Papers that include both cell/molecular (C) and human (H) related MeSH terms are classified as CH; Papers that include all three are classified as ACH. To define the MeSH terms of papers, Weber used the tree hierarchy of MeSH to map the three MeSH terms cell/molecular (C), animal (A), and human (H) to specific MeSH hierarchy nodes and their subtrees. To identify translational research, Weber constructed a “biomedical triangle”. Class A, C, and H papers are mapped to the three vertices of an equilateral triangle. AC, AH, and CH papers are respectively mapped to the midpoints of the three sides of the triangle. ACH papers map the center of the triangle. A collection of papers can be represented by the average position of a group of papers. Although a single paper can be mapped to only one of seven points (A, C, H, AC, AH, CH), a collection of papers can be mapped to any location within the triangle.

Studies on citation analysis between publications of different types

A paper was cited in clinical trials or clinical guidelines, suggesting that the paper might have an effect on clinical research or clinical practice that extends beyond academia. Based on a bibliometric analysis of 15 papers cited in clinical practice guidelines, Grant found that reference analysis of guidelines is a new way to monitor knowledge transfer (Grant et al., 2000). According to Eriksson, papers that were cited in clinical guidelines had a higher clinical “Research Level” score than papers that were uncited (Eriksson et al., 2020). Early works have shown that papers that were cited in clinical guidelines were often from their own countries and were more highly cited in the citation database than uncited ones (Grant, 1999; Lewison & Paraje, 2004; Lewison & Sullivan, 2008; Pallari et al., 2018). Contopoulos-Ioannidis, based on a sample of 101 basic research journal articles, found that there was a long-time interval between basic research and clinical trials (Contopoulos-Ioannidis et al., 2003). Thelwall used citations in clinical trials to predict the future influence of articles and found that the average number of citations for articles that have been cited in clinical trials was much higher than those of other articles in the same journal that have not been referenced in clinical trials (Thelwall & Kousha, 2016).

Based on the theory of the multi-stage translational research model, Rosas et al. regarded the emergence of primary research outputs in significant secondary research outputs (such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and clinical guidelines) as a milestone in the translation of primary research outputs (Rosas et al., 2013). To identify translational research, whether primary research is included in synthesized research is considered a measure. Rosas used the Mesh terms of papers in the PubMed database to determine the document type of forwarding citations. Han et al. partially revised Rosas’ method. Han et al. divided translational research into two categories: primary translational research, that is, the paper was any one of 11 types related to clinical research, clinical trials, or clinical guidelines; The second category is secondary translational research, which does not belong to any of the clinical research categories, but if a paper is cited in primary translational research, then the paper also makes an important contribution to the translational process (Han et al., 2018).

Newly developed indicators for measuring translation intensity

To predict the clinical translational potential of a single paper or a group of research papers, Hutchins et al. developed a novel indicator named “Approximate potential to translate scores (APT)” based on the method of the “biomedical triangle” and random forest model in machine learning (Hutchins et al., 2019). To construct vector space for machine learning, Hutchins summarized 7 characteristics of the focal paper (the proportion of “Molecular/cellular” (MC), “animal” (A) and “human”(H) MeSH terms; Whether “disease” (D), “treatment/diagnosis method” (E), “chemical/drug” (CD) is included in MeSH terms of the focal paper), average cited rate per year and 15 characteristics (Max, Mean and standard deviation of MC, A, and H; Mean and standard deviation of D, E, and CD) of the papers that cite the focal papers. APT was divided into 5 subgroups: < 5%, < 25%, < 50%, < 75% and > 95%. Hutchins et al. used citation data from different time windows to test the model and found that citation data from 2 years after publication also had a quite highly predictive performance.

Park et al. reported that the average APT for a group of problematic articles (human gene research articles with wrongly identified nucleotide sequences) ranged from 15 to 35%, indicating that there is a 15–35% chance that they will be referenced in clinical trials in the future (Park et al., 2022). The average APT of publications funded by the NIH Research Plan on Rehabilitation goals decreased from 2015 to 2018 with values between 0.33 and 0.29 (Jackson & Cernich, 2020). For publications supported by the Georgia CTSA grant (2007–2021), Llewellyn et al. calculated a mean APT score of 0.51, which suggests a 51% likelihood that the articles in the portfolio will be translated into clinical practice (Llewellyn et al., 2021). Li regarded APT as an indicator of translation intensity, which was used to quantify the translation results of 18 FDA-approved drugs (Li & Tang, 2021). They found that translation intensity (APT) had a positive correlation with the interdisciplinary characteristics of drug research. Nelson verified that content-based models (training the machine learning models by extracting characteristics from the metadata, titles, and abstracts) were superior to the citation-based method (inclusion in future patents, clinical guidelines, and clinical policies) in terms of forecasting the translational impact of medical papers (Nelson et al., 2022).

Kim et al. created a new measurement indicator called “Translational science scores (TS)” based on Han’s ideas (Kim et al., 2020). He believes that if a basic research paper is cited in a clinical research journal, it signals a transfer of knowledge from basic science to clinical science. Because each journal might be assigned multiple subject categories by the WOS database, Kim classified the journals that contained only the “clinical sciences” subject category as “clinical journals,” and the rest as “non-clinical journals”. TS refers to the ratio of the number of forward citations from “clinical journals” to the total number of forward citations the paper received. In order to ensure a stable TS score, the paper’s citation data must be maintained at least 4 years after publication (correlation coefficient threshold: 0.7), but if the paper has been cited at least 5 times, citation data of less than 4 years can also be used. Kim used several methods to verify the validity of TS. For example, a new indicator, called Department-based Translational Science (dTS), was calculated by using the proportion of clinical attributes of the first author’s institution, and it was found that dTS had a correlation of 0.748 with TS. Another example, the average TS of papers cited by patents was significantly higher than those papers that were not cited by patents. Furthermore, the average TS of basic research papers cited by patents was significantly higher than the average TS of all basic research papers in the sample.

Methodology

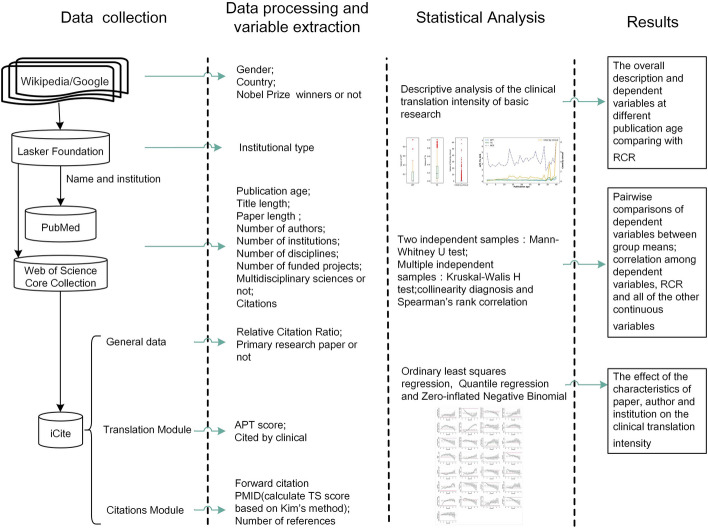

To investigate the clinical translation intensity of basic medical papers written by the Lasker Prize winners, we obtained the winners’ information from the official website of the Lasker Prize. We searched the published papers of the winners through the Web of Science and PubMed databases. We also established the dataset of published papers of Lasker Prize winners in Basic Medicine. Then, we further examined the clinical translation intensity of the Lasker Basic Medical Research Award winners’ basic medical research papers. We also examined the relationship between clinical translation intensity and the characteristics of the paper, the author, and the institution. The research framework is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overall process of research framework

Sample selection

Clinical translation intensity is a novel dimension to evaluate the social impact of papers. Because clinical research and basic research are located at different positions in the timeline of medical translation, there are certain differences in translation intensity between the two types of studies. In this paper, we only selected basic research papers for measurement, and it is innovative and meaningful to investigate the clinical impact of basic medical research.

In the award setting of the Lasker Medical Research Award, the basic medical research Award and the clinical medical research Award are awarded as different awards. This allows us to target the world’s leading contributors to basic medicine, who produce research papers that are more focused on basic medicine. Winners of the Lasker Prize have not only published basic research papers, but also clinical research papers. The Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research recipients may have produced a small number of clinical research papers. Therefore, after we collected papers published by winners of the Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research, we began to distinguish between basic research papers and clinical research papers.

In the field of biomedicine, basic medical research is biased toward biomedical theory, and clinical research is biased toward clinical practice. Clinical research focuses on discovering new or better ways to detect, diagnose, treat, and prevent diseases. So, clinical research is mainly carried out on patients, including collecting patients’ personal information, disease information, and response to treatment. Clinical trials are the core component of clinical research. In contrast, basic medical research is carried out in the laboratory, mainly using cell or animal models. The goal of basic medical research is to better understand cell biology and the mechanisms of interaction between various molecules and pathways. This will help us discover new therapeutic targets.

In this framework, the iCite platform roughly divides papers into basic research papers and clinical research papers and proposes an indicator called “Clinical” under the translation module of the iCite platform. It is a publication-type tag (Yes/No) that is assigned to each paper to indicate whether it is a clinical research paper or not. A paper is considered by iCite to be a clinical research paper when it falls into at least one of the following categories: Clinical Study, Clinical Trial, Clinical Trial, Phase I, Clinical Trial, Phase II, Clinical Trial, Phase III, Clinical Trial, Phase IV, Adaptive Clinical Trial, Controlled Clinical Trial, Randomized Controlled Trial, Clinical Trial Protocol, Observational Study, Guideline, Practice Guideline. We will use this indicator called “Clinical” to identify clinical medical research in our sample. In addition to clinical medicine research papers, we consider them to be basic research papers.

As we all know, the Lasker Basic Medicine Award winners are a group of outstanding scientists in the field of basic medicine. Accordingly, the papers published by these laureates represent high-quality papers with considerable academic impact in the field of basic medicine. We prefer to believe that these high-quality papers may have a stronger clinical translation intensity than more general papers. Only if the paper has sufficient clinical translation intensity can further analysis of the relationship of the characteristics of the paper, the author, and the institution with clinical translation intensity be carried out.

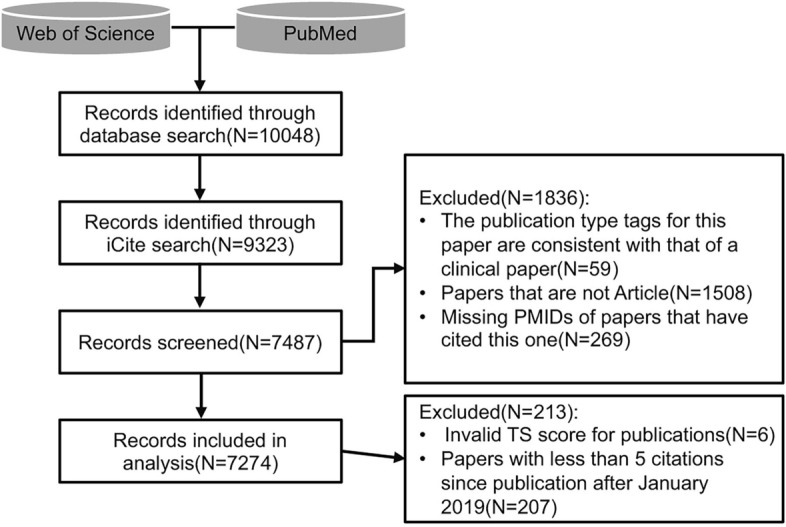

Figure 2 shows the flowchart of the identification and selection of research data. We used the Web of Science Core Collection database and the PubMed database for retrieving papers. The recipients’ names and institutions are used as search terms. The retrieval period was from April 6 to June 25, 2020. We initially received 10,048 papers from different databases. After 10,048 papers were imported into the iCite database, 9596 papers were returned. We performed de-duplication processing based on PMID number; 9323 papers remained. According to the TS score calculation method described by Kim in her paper, 59 papers of the “clinical” type were excluded. To calculate the TS score, 269 papers without forward citation information were deleted, and 8995 papers remained. Next, all the journals included in JCR in 2019 were classified by reference to the WOSCs discipline. According to the comparison table of “WOSCs classification—clinical and non-clinical” provided by Kim, Python programming was used to further sort out the “Journal name—Clinical and non-clinical comparison table” (including 3106 clinical journals and 9145 non-clinical journals). We used the pubmed_mapper program package to tag the clinical attributes of forward citations in our sample. Based on the TS calculation formula, we successfully assigned TS variables to 8782 papers. We referred to the stability thresholds of APT and TS comprehensively. We lowered the correlation coefficient threshold of TS to 0.6 so that the cumulative citation data 2 years after publication could meet the stability requirements of APT and TS. Then, we only retain papers that have been published for at least two years or have been cited at least five times. Because “review”, “letter & editorial material” and “other types” of papers may affect the stability of the results in our study, we deleted the papers that were not “Article” and the papers with an empty publication type. In the end, we had a sample of 7274 papers.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the identification and selection of research data. According to iCite’s definition of publication types, clinical article tags include Clinical Study, Clinical Trial, Clinical Trial, Phase I, Clinical Trial, Phase II, Clinical Trial, Phase III, Clinical Trial, Phase IV, Adaptive Clinical Trial, Controlled Clinical Trial, Randomized Controlled Trial, Clinical Trial Protocol, Observational Study, Guideline, Practice Guideline

Variable selection

Three dependent variables (APT, TS and Cited by Clin.) were chosen to measure the clinical translation intensity of papers. RCR was used as a reference variable. We selected three types of explanatory variables: 9 characteristic variables about the paper, 4 characteristic variables about the Lasker prize winners, and 2 characteristic variables about the institutions based mainly on the following evidence. All of the variables we selected are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the variables

| Type | Number | Indicator | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical impact indicator | 1 | APT score (approximate potential to translate) | Likelihood estimates of future citation of papers by clinical trials or clinical practice guidelines based on machine learning algorithms. |

| 2 | TS score (translational science score) | The ratio of the number of forward citations a paper received from clinical science to the total number of forward citations. | |

| 3 | Cited by clin. | The number of times a research paper is cited in a clinical research paper. | |

| Academic impact indicator | 1 | RCR (relative citation ratio) | A field-normalized and time-normalized citation score. RCR of a paper is the ratio of the paper citation rate to the expected citation rate in the field. According to Hutchins, when calculating the RCR, papers financed by NIH's R01 program were used as a benchmark. |

| Characteristics of the paper | 1 | Publication age | The year difference between the date of publication and the search date of the paper. |

| 2 | Primary research paper | Whether the paper is a primary research paper. Primary research papers include journal articles, clinical trials, pathology reports, etc., rather than editorial or reviews, etc.0=No;1=Yes. | |

| 3 | Multidisciplinary subject or not | Whether the category “Multidisciplinary science” is included in the Web of Science subject classification of a paper. 0 = No; 1 = Yes. | |

| 4 | Number of disciplines | The number of disciplines in the Web of Science subject classification. | |

| 5 | Number of authors | The number of all authors of the paper. | |

| 6 | Number of funded projects | The number of funded projects publicly mentioned in the paper by the authors. | |

| 7 | Title length | Number of words in Title. | |

| 8 | Paper length | The number of paper pages. | |

| 9 | Number of references | Number of references cited in the paper. | |

| Characteristics of the author | 1 | Physical age | The age of the author who received the Lasker Prize in Basic Medicine at the time of publication of the paper. |

| 2 | Gender | Gender of the author who received the Lasker Prize in Basic Medicine. 0 = male; 1 = female. | |

| 3 | Nationality | Nationality of the author who received the Lasker Prize in Basic Medicine. The first nationality of the winners is chose to be analyzed. | |

| 4 | Nobel prize | Whether the author who received the Lasker Prize in Basic Medicine has also received a Nobel Prize. 1 = received, 0 = not received. | |

| Characteristics of the institution | 1 | Number of institutions | Total number of institutions to which all authors belong. |

| 2 | Institutional type | The type of the institution where the author who received the Lasker Prize in Basic Medicine works, includes universities, research institutes, hospitals, businesses or company, and foundations. |

Dependent variables

APT

APT was first proposed by Hutchins in 2019. In the opinion of He and his colleagues [12], a paper cited once by clinical papers such as clinical trials or clinical practice guidelines marked a significant advance in the translation of biomedical knowledge. Hutchins selected 22 characteristic factors of each paper as early markers for the translation from basic research to clinical research. These factors predicted the probability of the paper being cited by clinical papers in the future, that is, the clinical usefulness of the paper in the future. On the iCite platform, the “clinical translational potential approximation (APT)” indicator is divided into five groups: < 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and > 95%. When the APT value of papers is 0.25, an average of 25% of papers are expected to be referenced in clinical papers. When the APT value of papers is 0.75, an average of 75% of papers are most likely to be mentioned in clinical papers. The larger the APT value, the greater the probability of the paper being used by clinical research in the future. The maximum APT value is 1, indicating that papers are expected to have an average of 100% chance of being cited in clinical papers. There is a minimum value of 0, which indicates that the probability of a paper being cited in a clinical paper is close to zero.

TS

In 2020, Kim proposed TS based on the ratio of the number of forward citations received from clinical science to the total number of forward citations. Forward citations from clinical research were seen as evidence of the clinical application of basic research. The authors used the share of citations in clinical journals to evaluate the relative importance of knowledge in a basic research paper for subsequent clinical and basic research. The TS score is between 0 and 1. The higher the TS score, the greater the clinical importance of a cited paper. A TS score greater than 0.5 indicates that the research paper will have a significant impact on clinical research than on basic research.

Clited by Clin.

Clited by Clin.is an indicator provided in the translation module on the iCite platform handled by the office of Portfolio Analysis at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The developers of this indicator consider the fact that basic research papers are cited by clinical research papers to be a strong indication that knowledge generated in basic research papers has been transferred to clinical research. Clinical research papers are generally defined as clinical trials or clinical practice guidelines. iCite classifies any of the 13 types of research (as listed in “Sample selection” section) as clinical research. In this framework, Cited by Clin. (The number of times a research paper is cited in a clinical research paper) is an indicative indicator of clinical translation intensity.

Reference variable

RCR (The relative citation ratio) is an indicator developed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2015 (Hutchins et al., 2016). RCR is a field- and time-normalized citation score. Hutchins, the earliest researcher on RCR, pointed out that the co-citation network can accurately reflect a paper’s field. Firstly, the field citation rate of the paper is calculated. Then, the RCR of the paper is the ratio of the paper citation rate to the expected citation rate in the field. According to Hutchins, when calculating the RCR, papers financed by NIH’s R01 program were used as a benchmark. When RCR is equal to 1.0, it indicates that the academic impact of the paper is equivalent to the average impact of NIH R01 project-funded papers. When RCR is greater than 1.0, it indicates that the academic impact of the paper is higher than the average level of NIH R01 project-funded papers. The RCR value can be obtained through the citation module of the iCite platform of NIH.

Explanatory variables

Characteristic variables of the papers

It takes a long time for basic research findings to be translated into clinical interventions to bring broader benefits to public health. So, there is a large “translational lag” (Roberts et al., 2012) or “valley of death” (Meslin et al., 2013). Studies have shown that it takes an average of 17 years for scientific research evidence to reach clinical practice (Westfall et al., 2007). Contopoulos-Ioannidis found that only 25% of high-impact basic medical research papers with clear treatment options or high potential for disease prevention entered clinical trials 20 years after publication (Contopoulos-Ioannidis et al., 2003, 2008). Therefore, publication age may be an factor influencing the clinical translation intensity of papers.

Broadly speaking, papers can be divided into primary research and secondary research. Scientific discovery needs to undergo a process of knowledge translation from its generation to its application in clinical research and practice. A primary research study generates the most original results, whereas a review, practice guidelines, and policy literature are considered secondary research. Primary research translates knowledge into secondary research through dissemination and diffusion. The inclusion of primary research into secondary research is a symbolic event of the occurrence of knowledge translation (Rosas et al., 2013). In other words, secondary research is the output of the next stage of primary research along the translation continuum. Therefore, whether a paper is a primary research or not might be correlated with the clinical translation intensity of the paper.

Bordons analyzed papers published by Spanish authors from 1990 to 1993. He found that there was a significant positive correlation between the Research Level and the interdisciplinary nature of the papers in both the cardiovascular system and pharmacology fields. The higher the Research Level was, the higher the degree of interdisciplinary research was (Bordons & Zulueta, 1997). Li studied drug research papers and concluded that the diversity of studies was positively correlated with the translation intensity of drugs (Li & Tang, 2021). Therefore, interdisciplinarity may be associated with the clinical translation intensity of papers. In the WOS database, the subject classification is determined based on the subject attributes of journals. One journal corresponds to one or more disciplines. In this study, we chose the number of disciplines assigned to journals and whether the journal includes the “Multidisciplinary Science” category to measure the interdisciplinary nature of papers.

In addition, we also chose some characteristics of papers as explanatory variables that have been proven to be related to the citation times or the quality of papers, such as number of authors and funded projects, length of the title, length of the paper, number of references (Amara et al., 2015; Ayres & Vars, 2000; Bornmann & Leydesdorff, 2015; Di Vaio et al., 2012; Falagas et al., 2013; Vanclay, 2013; Webster et al., 2009).

Characteristic variables about the authors

In terms of the characteristics of authors, studies have shown that authors of different ages have different citation behaviors (Costas & Bordons, 2011; Costas et al., 2012). The physical age reflects the author’s career stage which has been found to affect scientific integrity (Fanelli et al., 2015), knowledge recency (Liang et al., 2020), work meaningfulness (Lopez & Ramos, 2017), future research impact (Zuo & Zhao, 2021), publication and scientists’ satisfaction (Husemann et al., 2017). Whether there are differences in clinical translation intensity in the papers published by authors at different career stages needs to be further examined. At the same time, gender, nationality, and institution are biased in the research community. Gender has a significant influence on the citations of papers. In some research fields, publications by female first authors receive fewer citations than expected. For example, in the urology field, female authorship exhibited a significant citation advantage over male authors, but female authors were less likely to be cited (Shukla et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). This situation also exists in astronomical publications (Caplar et al., 2017). In terms of nationality, some studies have found that international co-authorship is associated with higher citations (Sin, 2011). Therefore, in this study, gender and nationality are included as explanatory variables. Finally, the award effect does exist, and papers written by highly reputed authors often receive higher citations (Collet et al., 2014). The publications of Nobel prize-winning authors are more likely to receive substantial citation growth than non-Nobel publications (Frandsen & Nicolaisen, 2013). Therefore, whether the author won the Nobel Prize was taken as one of the explanatory variables.

Characteristic variables of the institutions

Some studies have found that the size of the cooperative team had a potential impact on the citations of outputs (Lecocq & Van Looy, 2009). The number of institutions co-publishing papers was also slightly associated with an increase in citations to publications (Didegah & Thelwall, 2013; Leimu & Koricheva, 2005). Narin and Hamilton found that the average Research Level of papers published by medical schools, hospitals, and clinics in the United States was between 2.0 and 3.0, while the average Research Level of papers published by universities was between 3.0 and 4.0 (Narin & Hamilton, 1996). It can be seen that university research is more basic than that of medical schools, hospitals, and clinics. Narin and Rozek discovered that in the same journals between 1973 and 1975, biomedical research conducted by pharmaceutical companies was more clinical than that accomplished by universities but more basic than the biomedical research conducted by major U.S. medical schools, hospitals, and clinics (Narin & Rozek, 1988). Top universities tend to be associated with more outputs and citation scores (Amara et al., 2015). Given this, we assumed that the clinical translation intensity of biomedical research might be related to the author’s institutional type and the number of institutions.

Data acquisition

In this study, APT, Cited by Clin. and RCR were extracted based on the PMID numbers through the iCite database. TS was calculated according to Kim’s calculation method. In total, we chose 9 variables to describe the characteristics of the papers, and 4 variables to represent the characteristics of the authors (Note that the characteristics of the author here refer specifically to the characteristics of the author of each paper who received the Lasker Prize in Basic Medicine, not to any author of each paper). And 2 variables for institutional characteristics. The official website of the Lasker Prize (https://laskerfoundation.org) is the most authoritative data source which has recorded the name, year of award, and the institutions of the winners. We searched for other information such as the gender, the nationality of the winners, and whether they ever won the Nobel Prize through Wikipedia and Google. We obtained the characteristics of the papers and the institutions through the Web of Science database and PubMed. These characteristics include publication year, the total number of pages, the title, the authors, the institutions, the WOS discipline, and funded projects. We calculated publication age, the length of titles, the number of authors, institutions, disciplines, and funded projects. In addition, papers are tagged as to whether they are primary research papers or not based on information from the iCite database. We classified papers into multi-disciplinary and non-multi-disciplinary according to whether or not they contained “Multidisciplinary Sciences categories” in the WOS discipline field. We manually divided the institutions of the winners into five categories.

Statistical methods

Firstly, we conducted a descriptive analysis of the distribution characteristics of APT and TS. Next, a nonparametric test including Mann–Whitney U (2 samples) and Kruskal–Wallis 1-way ANOVA (k samples) was selected for the univariate analysis to compare the distributions of APT, TS, and Cited by Clin. across groups. Because the distribution of clinical translation intensity varied among subgroups, the mean rank was compared between two and more independent samples. Thirdly, we used the Spearman rank correlation test to analyze the correlation among continuous variables. Next, we used the OLS regression model and a quantile regression model (Koenker & Bassett, 1978) to examine whether the characteristics of papers, authors, and institutions have an effect on the clinical translation intensity of papers and their changing trends. By correcting heteroscedasticity, the OLS regression method can provide more robust results. Quantile regression is suitable for the test of linear or nonlinear relationships between the dependent variable and the explanatory variables. The quantile regression method can show the overall characteristics of dependent variables under each quantile, less affected by outliers. By comparison to the OLS regression method, the quantile regression method helps eliminate biased estimates in OLS and is more robust. Different from APT and TS, Cited by Clin. contains a large number of zero values (80%), and its numerical distribution is over-dispersion (the Variance is significantly larger than the Mean), which exceeds the predictive ability of the quantile regression model. Therefore, the zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) model (Cameron & Trivedi, 1998) was used to test the influencing factors Cited by Clin. SPSS 26.0 software was used for descriptive statistics, univariate analysis, and correlation analysis, and STATA 16.0 software was used for regression analysis. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive analysis

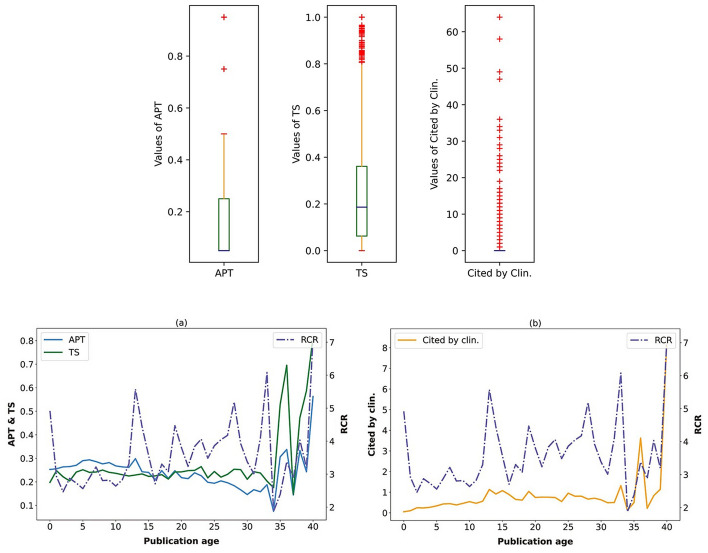

APT is an indicator to predict the probability of a paper or a group of papers being cited by clinical papers in the future. This refers to the clinical utility of papers in the future. As shown in Table 2, APT (N = 7274) ranges from 0.05 to 0.95 (Mean ± SD: 0.24 ± 0.26, Median: 0.05). The median APT value of Lasker Prize winners’ published papers is 0.05, indicating that 50% of Lasker prize winners’ papers have an approximate value of clinical translational potential less than 0.05, and the potential of being referenced by clinical papers is less than 5%. APT values of more than half of the papers were 0.05 (51.8%), and the rest were 0.25 (24.7%), 0.50 (10.7%), 0.75 (10.2%), and 0.95 (2.6%) according to their frequency. It can be seen that the papers with an APT value less than or equal to 0.50 account for 87.2%, while those with an APT value greater than 0.5 account for only 12.8%. And that means, 87.2% of the papers had a 50% or lower probability of being cited in future clinical papers, and only 12.8% had a more than 50% probability of being cited in future clinical papers.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for dependent variables

| APT (N = 7274) | TS (N = 7274) | Cited by Clin. (N = 7274) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Range | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Range | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Range |

| 0.24 ± 0.26 | 0.05 (0.05–0.25) | 0.05–0.95 | 0.24 ± 0.21 | 0.19 (0.06–0.36) | 0.00–1.00 | 0.59 ± 2.40 | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00–64.00 |

| Valid values | Frequency | % | Valid values | Frequency | % | Valid values | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APT = 0.05 | 3769 | 51.8 | TS ≤ 0.05 | 1627 | 22.4 | 0 | 5821 | 80.0 |

| APT = 0.25 | 1794 | 24.7 | 0.05 < TS ≤ 0.25 | 2826 | 38.9 | 1 | 740 | 10.2 |

| APT = 0.50 | 778 | 10.7 | 0.25 < TS ≤ 0.50 | 1973 | 27.1 | 2 | 270 | 3.7 |

| APT = 0.75 | 742 | 10.2 | 0.50 < TS ≤ 0.75 | 678 | 9.3 | 3 | 146 | 2.0 |

| APT = 0.95 | 191 | 2.6 | 0.75 < TS ≤ 0.95 | 101 | 1.4 | 4 | 88 | 1.2 |

| 0.95 < TS ≤ 1.00 | 69 | 0.9 | 5–6 | 83 | 1.1 | |||

| 7–8 | 47 | 0.7 | ||||||

| 9–23 | 63 | 0.9 | ||||||

| ≧24 | 16 | 0.2 |

TS value is between 0 and 1. It stands for the ratio of the paper’s forward citations from clinical research to the total forward citations the paper received. The higher the TS value, the more critical the basic research paper is to subsequent clinical research, and the more valuable it is to clinical research. If the TS score exceeds 0.5, it indicates that a basic research paper is mainly cited in clinical research papers. This is because its value to clinical research exceeds its value to basic research. In our sample, TS (N = 7274) ranged from 0.00 to 1.00 (Mean ± SD: 0.24 ± 0.21, Median: 0.19). 88.4% of the papers had TS values less than or equal to 0.5. Only 11.6% of papers had a TS value of more than 0.5. 11.6% of papers were more valuable for clinical research than for basic research and had relatively higher clinical translation intensity. The median TS value of the papers is 0.19 (less than 0.5), suggesting that 50% of the Lasker Prize winners’ papers are relatively more influential for subsequent basic research. From the perspective of upper and lower quartiles, the lower quartile was 0.06, while the upper quartile was only 0.36, still less than 0.5, indicating that 75% of papers in our sample had a higher value for basic research than for clinical research, and the clinical translation intensity was low. On further examination, the 85th and 95th percentile of TS scores were 0.47 and 0.65 respectively. So, to be more precise, about 85% of Lasker Prize-papers have more value for basic research than for clinical research; About 15% of Lasker Prize winners’ papers had more value to clinical research than basic research, and 5% of Lasker Prize winners’ papers had nearly twice as much value to clinical research as to basic research.

On average, the 7274 papers in this sample were cited 0.59 times by clinical research papers. The maximum number of citations of a single paper by clinical research papers reached 64. However, eighty percent of the papers had a Cited by Clin. of zero. This suggests that 80% of the papers in our sample have not yet been cited in clinical research papers. 10.2% of the papers were cited once by clinical research papers; 3.7% were cited twice by clinical research papers; 3.2% of the papers were cited 3–4 times by clinical research papers; Papers that were cited five or more times by clinical research papers accounted for only 2.9% of the sample.

As shown in Fig. 3a, when the publication age is less than 20 years, APT and TS show a slight fluctuation between 0.2 and 0.3, but the variation of TS is always around a horizontal line, while APT shows a downward trend. When the age of the papers is between 20 and 34, the average APT value of the papers continues to decline, approaching 0.075, while the average TS value still has no significant change and only fluctuates in a small range between 0.2 and 0.3. When the papers are older than 34, there is a significant fluctuation in the rise of APT and TS. The trend line of TS is close to 0.8, and APT rises to 0.56. In Fig. 3b, when the age of the paper is less than 33 years old, the average Cited by Clin. of the papers tends to increase slowly from 0 to 1. When a paper is 13 years, 15 years, and 19 years old, Cited by Clin. value has a small peak, slightly exceeding 1. After the age of 33, there is a big jump in the Cited by Clin. score every three years: at 33, the average Cited by Clin. score is 1.32; At the age of 36, the average Cited by Clin. score was 3.63; At age 40, the average Cited by Clin. score is 8.5.

Fig. 3.

Box plot of the APT, TS score, and Cited by Clin. distribution and average clinical translation intensity compared with that average citation at different publication ages. As Box plots shown in Fig. 3, APT, TS, and Cited by Clin. are all positively skewed. The first quantile value of the box of APT is equal to the median and the lower limit. The median of APT and TS is both smaller than the mean. Since the median, first quartile, third quartile, upper limit, and lower limit of Cited by Clin. are all 0, the box and the whisker are barely visible. And plenty of outliers from Cited by Clin. are shown. In Fig. 3, we can also compare the average APT, TS, and Cited by Clin. of papers at different publication ages in the sample and their differences with average RCR. This is a two-ordinate plot. The left ordinate is APT, TS, and Cited by Clin. and the right ordinate is RCR. If Cited by Clin. is compared with APT and TS in the same figure, APT and TS of the paper change slightly with the age of publication, which is masked by the change in Cited by Clin. Therefore, we use a, b to compare the differences between APT & TS and RCR, and the differences between Cited by Clin. and RCR, respectively

RCR is the ratio of the average number of citations per year to the expected number of citations per year for papers funded by the R01 program NIH. In Fig. 3a and Fig. 3b, the RCR value of papers is relatively stable when the papers are 2 to 10 years old. However, RCR varies greatly between 3.0 and 6.0 when the publication age is from 10 to 34 years. There is a substantial increase in the average RCR of papers after 34 years, even exceeding 7.0 to some extent.

In general, compared with RCR, APT, TS and Cited by Clin. have a more similar trend with the age of publication increase. RCR fluctuates a great deal before the age of 34. Instead of that, APT, TS, and Cited by Clin. do not change significantly before the papers are less than 34 years old. We were surprised to find that after the paper had been published for 34 years, the four variables exhibited the same change trend. There was a small decrease, but it increased steadily on the whole. In particular, the trend line of APT and TS almost coincided.

Nonparametric test

Non-parametric tests were used to compare the clinical translation intensity between 12 independent variables’ subgroups (Table 3). We found that clinical translation intensity differed significantly in these 6 characteristics related to the paper, 4 characteristics about the author, and 2 characteristics of the institutions. However, we also found that there were no significant differences in publication age, multidisciplinary science, number of disciplines, gender, and Nobel Prize for individual types of clinical translation intensity variables. We’ll work through them one by one.

Table 3.

Nonparametric test of APT, TS and Cited by Clin. differences between groups

| Variable | Frequency | % | APT | TS | Cited by Clin. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | Statistics | p value | Mean Rank | Statistics | p value | Mean rank | Statistics | p value | |||

| Characteristics of the paper | 7274 | ||||||||||

| Age of publication | 134.298*** | 0.000 | 1.367 | 0.713 | 64.481*** | 0.000 | |||||

| ≤ 10 (REF) | 3027 | 41.61 | 3884.16 | 3635.36 | 3475.86 | ||||||

| 11–20 | 2017 | 27.74 | 3670.51 | 3602.10 | 3766.18 | ||||||

| 21–30 | 1805 | 24.81 | 3314.80 | 3681.31 | 3755.61 | ||||||

| ≥ 31 | 425 | 5.84 | 3094.56 | 3634.69 | 3676.41 | ||||||

| Primary research paper | − 2.404* | 0.016 | − 8.603*** | 0.000 | − 4.110*** | 0.000 | |||||

| No (REF) | 409 | 5.62 | 3860.27 | 4503.93 | 3926.65 | ||||||

| Yes | 6865 | 94.38 | 3624.23 | 3585.88 | 3620.27 | ||||||

| Multidisciplinary science | − 5.663*** | 0.000 | − 1.780 | 0.075 | − 4.013*** | 0.000 | |||||

| No (REF) | 5223 | 71.80 | 3557.24 | 3664.92 | 3594.32 | ||||||

| Yes | 2051 | 28.20 | 3841.88 | 3567.66 | 3747.47 | ||||||

| Number of disciplines | − 3.660*** | 0.000 | − 5.144*** | 0.000 | − 1.054 | 0.292 | |||||

| 1 discipline | 4943 | 67.95 | 3580.66 | 3550.67 | 3625.07 | ||||||

| ≥ 2 disciplines | 2331 | 32.05 | 3758.04 | 3821.63 | 3663.87 | ||||||

| Number of authors | 795.584*** | 0.000 | 481.189*** | 0.000 | 128.936*** | 0.000 | |||||

| 1 author | 239 | 3.29 | 3517.08 | 4541.45 | 3834.75 | ||||||

| 2–5 authors | 3514 | 48.31 | 3063.45 | 3121.82 | 3438.07 | ||||||

| 6–10 authors | 2388 | 32.83 | 3932.05 | 3902.93 | 3794.33 | ||||||

| ≥ 11 authors | 1133 | 15.58 | 4822.51 | 4486.77 | 3883.88 | ||||||

| Number of funded projects | 162.352*** | 0.000 | 67.652*** | 0.000 | 7.598* | 0.022 | |||||

| 0 funded project | 1834 | 25.21 | 3367.23 | 3658.34 | 3703.84 | ||||||

| 1–3 funded projects | 2611 | 35.89 | 3437.73 | 3387.54 | 3582.02 | ||||||

| ≥ 4 funded projects | 2829 | 38.90 | 3997.09 | 3854.69 | 3645.69 | ||||||

| Characteristics of the author | |||||||||||

| Physical age | 38.415*** | 0.000 | 61.759*** | 0.000 | 61.394*** | 0.000 | |||||

| ≤ 35 | 38 | 0.52 | 3812.88 | 4279.62 | 3639.16 | ||||||

| 36–45 | 369 | 5.07 | 3673.12 | 3549.45 | 4004.33 | ||||||

| 46–55 | 1634 | 22.47 | 3663.99 | 3534.23 | 3784.27 | ||||||

| 56–65 | 2480 | 34.09 | 3534.99 | 3564.61 | 3629.67 | ||||||

| 66–75 | 1730 | 23.79 | 3559.79 | 3573.01 | 3496.06 | ||||||

| ≥ 75 | 1023 | 14.06 | 3955.75 | 4096.11 | 3528.85 | ||||||

| Gender | − 1.717 | 0.086 | − 0.035 | 0.972 | − 4.764*** | 0.000 | |||||

| Male | 7005 | 96.30 | 3629.89 | 3637.67 | 3621.47 | ||||||

| Female | 269 | 3.70 | 3835.66 | 3633.07 | 4054.98 | ||||||

| Nationality | 200.296*** | 0.000 | 329.320*** | 0.000 | 190.633*** | 0.000 | |||||

| The U.S. (REF) | 4765 | 65.51 | 3680.71 | 3633.47 | 3639.14 | ||||||

| Japan | 539 | 7.41 | 3704.36 | 4011.42 | 3499.82 | ||||||

| United Kingdom | 486 | 6.68 | 3164.83 | 3497.36 | 3443.69 | ||||||

| Australia | 343 | 4.71 | 3878.98 | 3639.59 | 4253.64 | ||||||

| Germany | 347 | 4.77 | 3158.15 | 2426.09 | 3155.74 | ||||||

| Canada | 283 | 3.89 | 3323.87 | 3282.74 | 3863.97 | ||||||

| Switzerland | 157 | 2.16 | 4719.60 | 4745.21 | 4351.32 | ||||||

| Israel | 97 | 1.33 | 2706.84 | 3406.66 | 3053.63 | ||||||

| France | 104 | 1.43 | 4761.88 | 5371.74 | 3596.94 | ||||||

| Sweden | 61 | 0.84 | 4303.43 | 5645.01 | 4217.01 | ||||||

| South Africa | 34 | 0.47 | 2452.22 | 2566.37 | 2911.00 | ||||||

| Argentina | 34 | 0.47 | 2964.71 | 2937.47 | 3625.66 | ||||||

| Romania | 24 | 0.33 | 3055.69 | 4124.33 | 3256.21 | ||||||

| Nobel prize | − 3.597*** | 0.000 | − 0.403 | 0.687 | − 3.808*** | 0.000 | |||||

| No | 3527 | 48.49 | 3553.65 | 3647.71 | 3570.10 | ||||||

| Yes | 3747 | 51.51 | 3716.42 | 3627.89 | 3700.95 | ||||||

| Characteristics of the institution | |||||||||||

| Number of institutions | 590.902*** | 0.000 | 240.253*** | 0.000 | 41.780*** | 0.000 | |||||

| ≤ 1 institution | 1903 | 26.16 | 3063.97 | 3294.53 | 3526.83 | ||||||

| 2–5 institutions | 3987 | 54.81 | 3545.27 | 3538.42 | 3615.46 | ||||||

| ≥ 6 institutions | 1384 | 19.03 | 4691.78 | 4394.51 | 3853.17 | ||||||

| Institutional type | 172.779*** | 0.000 | 275.008*** | 0.000 | 140.825*** | 0.000 | |||||

| University (REF) | 5726 | 78.72 | 3531.46 | 3506.45 | 3549.19 | ||||||

| Research Institute | 1128 | 15.51 | 4170.93 | 4439.32 | 4031.14 | ||||||

| Hospital | 296 | 4.07 | 4012.62 | 3471.44 | 4029.85 | ||||||

| Business or company | 45 | 0.62 | 4121.52 | 4811.80 | 3628.46 | ||||||

| Foundation | 79 | 1.08 | 2025.84 | 1640.30 | 2952.53 | ||||||

Statistics: Mann–Whitney U (2 samples) or Kruskal–Wallis 1-way ANOVA (k samples) tests

IQR inter-quartile range

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05

In our sample, 41.61% of papers were published 10 years ago or earlier. The publication age of the papers (N = 7274) ranges from 0 to 40 (Mean ± SD: 14.71 ± 9.359). It can be seen that the younger the publication age of the paper, the higher the mean rank of APT (p < 0.001). Cited by Clin. variable also has significant differences in the group of publication age. A pairwise comparison shows that Cited by Clin. variable of group ≦ 10 is significantly smaller than that of other age groups (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in the age groups of publication for TS.

Moreover, APT (p < 0.05), TS (p < 0.001), and Cited by Clin. (p < 0.001) of primary research papers are significantly lower than those of secondary research papers. We found that 28.20% of papers were published in journals in the “Multidisciplinary science” category defined by WOS. APT and Cited by Clin. scores of multidisciplinary papers were significantly higher than those of non-multidisciplinary papers (p < 0.001). However, there is no significant difference in TS score on whether the paper is multidisciplinary science or not. In this study, according to the data downloaded from the Web of Science, 67.95% of the papers belong to a single discipline. In addition, 32.05% of the papers belong to two or more disciplines. The number of disciplines in which papers are published varies from 1 to 6, with an average of 1.43 disciplines. The APT and TS of papers with 2 or more disciplines are significantly higher than those of papers with a single discipline (p < 0.001). But the number of disciplines the papers belong to does not affect Cited by Clin.

In our sample, 48.3% of papers had 2–5 authors; 32.8% of papers had 6 to 10 authors; Fewer papers had 11 or more authors (15.58%), and only 3.29% had a single author. The mean number of authors per paper was 6.88 ± 6.258. Significant differences were found between the different number of authors subgroups for APT, TS, and Cited by Clin (p < 0.001). Roughly speaking, the larger the number of authors, the higher the APT. To our surprise, the clinical translation intensity of papers published by a single author is higher than that of papers published by 2 to 5 authors.

In addition, 26.16% of papers are published by researchers from a single institution; 54.81% of papers were written by authors from 2 to 5 institutions. The mean number of collaborating institutions was 3.78 with a median of 3.00. We found that all three types of clinical translation intensity variables showed the same trend, that is, the “≧ 6 institutions” group was significantly larger than the “2–5 institution” group (p < 0.001), and the “2–5 institution” group was greater than “≦ 1 institution” group (p < 0.001).

Moreover, about 25.21% of papers in the sample were not supported, 35.89% of the papers were supported by 1–3 projects, and 38.90% of the papers were supported by 4 or more projects. The mean number of projects per paper was 3.29 with a median of 2.00. APT of papers with 4 or more funded projects is significantly higher than that of the other two groups (p < 0.001). For TS and Cited by Clin., 1–3 funded project groups are lower than the other two groups (p < 0.05).

The 56–65 age group of authors produced the most papers, accounting for 34.09%, followed by the 66–75 age group (23.79%) and the 46–55 age group (22.47%). Only 14.06% of papers were written by authors in the 75 or older age group. It is interesting to note that the APT and TS of papers published by authors aged 75 and above were significantly higher than that of papers published by authors aged 46–55 (p < 0.01), 56–65 (p < 0.001), and 66–75 (p < 0.001). Furthermore, authors in the 36–45 age group had the highest average Cited by Clin. for published papers.

The number of papers published by males is 7005, accounting for 96.3%, which is the absolute majority. The results show that Cited by Clin. of the papers published by female laureates is significantly higher than that of male laureates, but the gender difference between APT and TS is not significant (p < 0.001).

There is a significant difference in clinical translation intensity between the nationalities of the winners. The United States has the highest number of winners (65.51%), but the winners with the highest average APT are from France (p < 0.001); The winners with the highest average TS of papers are from Sweden and France (p < 0.001); The highest average Cited by Clin. for papers came from Switzerland and Australia (p < 0.001).

Winners affiliated with universities published the most, accounting for 78.72%, followed by research institutes (15.51%), hospitals (4.07%), foundations (1.08%), and businesses or companies (0.62%). The clinical translation intensity, whether APT, TS, or Cited by Clin., differed significantly in terms of the five institutional types. In this study, the APT of papers published by winners whose institution is a research institute is the highest. This is followed by businesses or companies, then hospitals, and universities, and the lowest is foundations. In a slightly different way, winners whose institutions were research institutes or hospitals received the highest Cited by Clin., followed by universities, companies, or businesses.

In our sample, the Lasker laureates who won the Nobel Prize produced 3747 papers, accounting for 51.51%. In contrast, the Lasker laureates who did not win the Nobel Prize later produced 3527 papers, accounting for 48.49%. There is no big difference between the two groups in the number of papers published. However, it is very interesting to find that the APT and Cited by Clin. of the papers published by the Lasker prize winners who also won the Nobel Prize was significantly higher than that of the papers published by the Lasker prize winners who did not win the Nobel Prize (p < 0.001). Unfortunately, TS values were not significantly related to a Nobel Prize (p > 0.1).

Spearman correlation

Spearman correlations were conducted among APT, TS, Cited by Clin., RCR, and all of the other continuous variables. As shown in Table 4, APT has a moderate positive correlation with TS (r = 0.549, p < 0.05), Cited by Clin. (r = 0.530, p < 0.05); TS is weakly correlated with Cited by Clin. (r = 0.383, p < 0.05); RCR was positively associated with clinical translation intensity indicators (APT: r = 0.553, p < 0.05; TS: r = 0.184, p < 0.05; Cited by Clin.: r = 0.381, p < 0.05). The correlation between RCR and TS is significant, but the correlation coefficient is less than 0.2, which can be considered as having no correlation.

Table 4.

Spearman’s Rho correlation matrix for continuous variables

| Publication age | Number of disciplines | Number of authors | Number of institutions | Number of funded projects | Length of title | Length of paper | Number of references | Physical age | APT | TS | Cited by clinical | RCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication age | 1.000 | 0.002 | − .419** | − .530** | − .545** | .103** | − .367** | − .253** | − .455** | − .131** | 0.013 | .096** | − 0.008 |

| Number of disciplines | 0.002 | 1.000 | .045** | .032** | − 0.006 | 0.003 | .218** | .076** | − .051** | .034** | .060** | 0.009 | − .035** |

| Number of authors | − .419** | .045** | 1.000 | .720** | .467** | .090** | .226** | .140** | .182** | .325** | .224** | .123** | .200** |

| Number of institutions | − .530** | .032** | .720** | 1.000 | .513** | 0.007 | .233** | .177** | .172** | .298** | .184** | .081** | .163** |

| Number of funded projects | − .545** | − 0.006 | .467** | .513** | 1.000 | − 0.004 | .249** | .198** | .291** | .170** | .070** | − 0.003 | .093** |

| Title length | .103** | 0.003 | .090** | 0.007 | − 0.004 | 1.000 | .078** | .057** | .025* | − 0.005 | .049** | 0.020 | − .062** |

| Paper length | − .367** | .218** | .226** | .233** | .249** | .078** | 1.000 | .588** | .138** | .039** | − .045** | − .084** | .042** |

| Number of references | − .253** | .076** | .140** | .177** | .198** | .057** | .588** | 1.000 | .125** | .096** | 0.000 | − 0.013 | .105** |

| Physical age | − .455** | − .051** | .182** | .172** | .291** | .025* | .138** | .125** | 1.000 | .025* | .055** | − .084** | − .174** |

| APT | − .131** | .034** | .325** | .298** | .170** | − 0.005 | .039** | .096** | .025* | 1.000 | .549** | .530** | .553** |

| TS | 0.013 | .060** | .224** | .184** | .070** | .049** | − .045** | 0.000 | .055** | .549** | 1.000 | .383** | .184** |

| Cited by clinical | .096** | 0.009 | .123** | .081** | − 0.003 | 0.020 | − .084** | − 0.013 | − .084** | .530** | .383** | 1.000 | .381** |

| RCR | − 0.008 | − .035** | .200** | .163** | .093** | − .062** | .042** | .105** | − .174** | .553** | .184** | .381** | 1.000 |

**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

In addition, APT was positively correlated with the number of disciplines (r = 0.034, p < 0.01), number of authors (r = 0.325, p < 0.01), number of institutions (r = 0.298, p < 0.01), number of funded projects (r = 0.170, p < 0.01), length of papers (r = 0.039, p < 0.01) and number of references (r = 0.096, p < 0.01). APT was negatively correlated with publication age (r = − 0.131, p < 0.01).

TS has a significant positive relationship with the number of disciplines (r = 0.060, p < 0.01), number of authors (r = 0.224, p < 0.01), number of institutions (r = 0.184, p < 0.01), number of funded projects (r = 0.070, p < 0.01), length of title (r = 0.049, p < 0.01) and physical age (r = 0.055, p < 0.01) and significant negative relationship with the length of paper (r = − 0.045, p < 0.01).

Cited by Clin. showed positive and significant correlations with publication age (r = 0.096, p < 0.01), number of authors (r = 0.123, p < 0.01), and number of institutions (r = 0.081, p < 0.01). In contrast, Cited by Clin. was negatively correlated with the length of paper (r = − 0.084, p < 0.01) and physical age (r = − 0.084, p < 0.01).

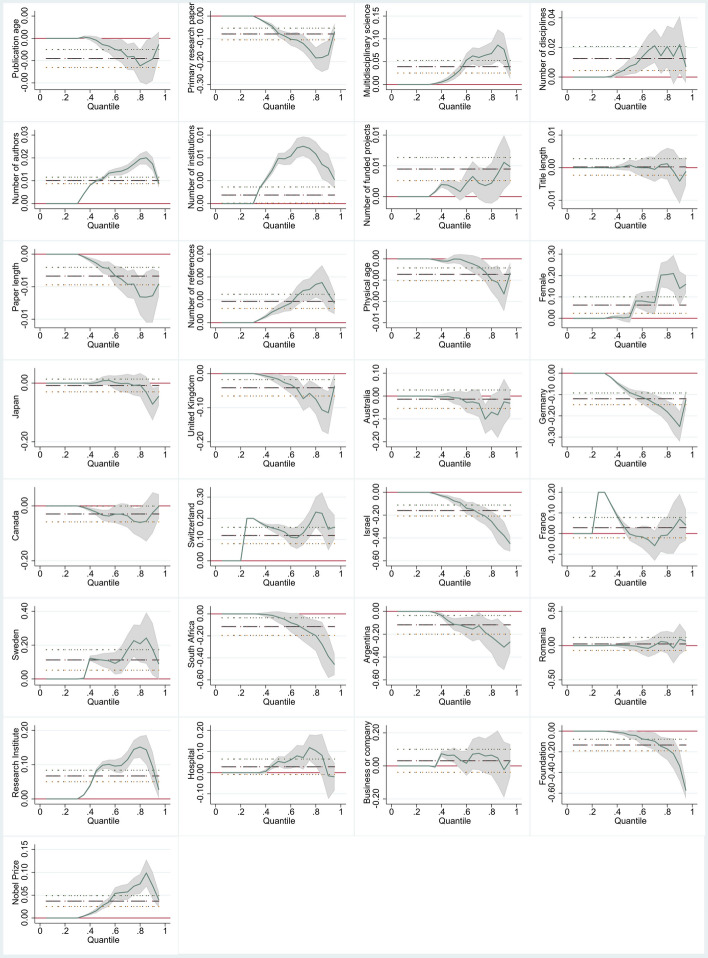

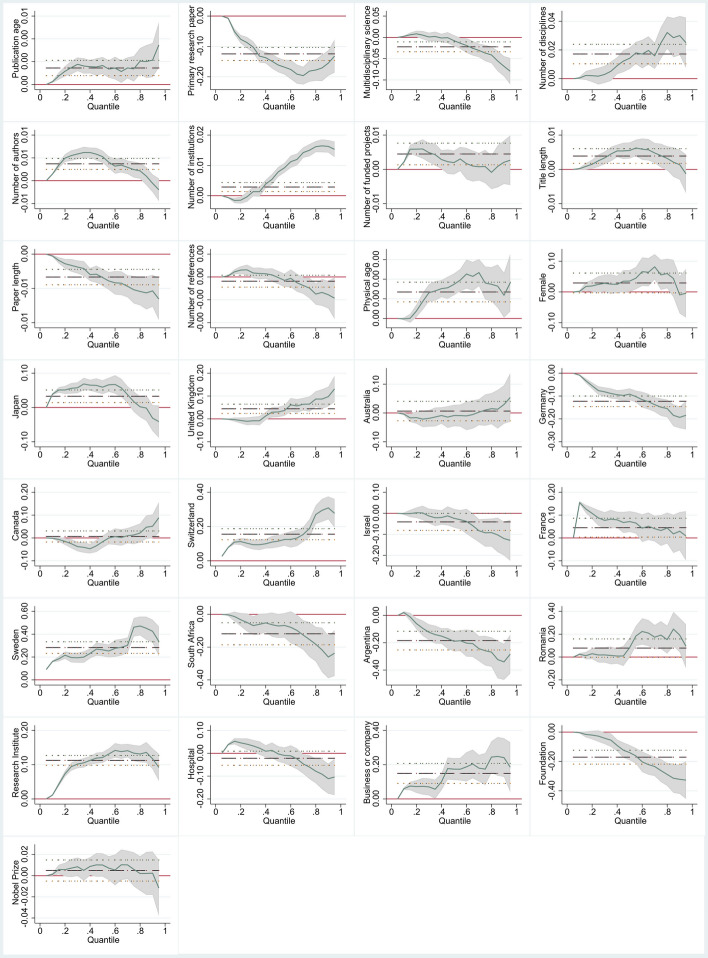

OLS regression and quantile regression

Before conducting the regression, we performed a multicollinearity diagnosis (Table S1). The results indicated that there was no problem with multicollinearity. We used classical OLS regression to estimate the conditional mean of clinical translation intensity. We also estimated the effect of these factors on the range of variation in the explained variables and the shape of the conditional distribution.

In Table 5, we present the coefficients and associated standard errors for both OLS and quantile regression estimates. These results are pictured in Figs. 4 and 5 where we exhibit both APT and TS at the mean (OLS) and different points of the APT and TS distribution. We estimated APT and TS for the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th quantiles. The results have shown the variation in parameter estimates of both APT and TS across the OLS and quantiles. OLS estimates only provide a baseline of the conditional mean of effects. We will compare these with estimates of different quantiles in the APT and TS conditional distributions. We will analyze the different influencing factors one by one below.

Table 5.

OLS and quantile regression models, QR 0.25, 0.50, 0.75 and 0.95

| Variables | APT | TS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | Quantile | OLS | Quantile | |||||||||

| B | β | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.95 | B | β | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.95 | |

| Paper-level characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Publication age | − 0.00181*** | − 0.066 | 0 | − 0.000562 | − 0.00163** | − 0.000547 | 0.00145*** | 0.0633 | 0.00148*** | 0.00166*** | 0.00137** | 0.00347*** |

| (0.000433) | (4.69e − 05) | (0.000495) | (0.000814) | (0.000934) | (0.000412) | (0.000330) | (0.000419) | (0.000643) | (0.000904) | |||

| Primary research paper | ||||||||||||

| No (REF) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | − 0.0787*** | − 0.0707 | − 0 | − 0.0750*** | − 0.148*** | − 0.0681** | − 0.125*** | − 0.134 | − 0.0873*** | − 0.161*** | − 0.181*** | − 0.132*** |

| (0.0138) | (0.00150) | (0.0158) | (0.0260) | (0.0298) | (0.0131) | (0.0105) | (0.0134) | (0.0206) | (0.0289) | |||

| Multidisciplinary science | 0.0389*** | 0.0683 | − 0 | 0.0200** | 0.0642*** | 0.0307* | − 0.0223*** | − 0.0469 | 0.00527 | − 0.00775 | − 0.0368*** | − 0.0795*** |

| (0.00723) | (0.000806) | (0.00851) | (0.0140) | (0.0160) | (0.00581) | (0.00566) | (0.00721) | (0.0110) | (0.0155) | |||

| Number of disciplines | 0.0125*** | 0.0351 | 0 | 0.00722 | 0.0143* | 0.00686 | 0.0172*** | 0.0577 | 0.00175 | 0.0142*** | 0.0249*** | 0.0251*** |

| (0.00409) | (0.000473) | (0.00500) | (0.00820) | (0.00942) | (0.00391) | (0.00332) | (0.00423) | (0.00648) | (0.00912) | |||

| Number of authors | 0.0101*** | 0.247 | 0 | 0.0107*** | 0.0173*** | 0.00880*** | 0.00370*** | 0.108 | 0.00551*** | 0.00529*** | 0.00244** | − 0.00197 |

| (0.00139) | (8.34e − 05) | (0.000881) | (0.00145) | (0.00166) | (0.00106) | (0.000586) | (0.000745) | (0.00114) | (0.00161) | |||

| Number of funded projects | 0.00448*** | 0.0641 | 0 | 0.00143 | 0.00179 | 0.00486** | 0.00224** | 0.0384 | 0.00297*** | 0.000989 | 0.000411 | 0.00133 |

| (0.00129) | (0.000110) | (0.00116) | (0.00191) | (0.00219) | (0.000984) | (0.000774) | (0.000984) | (0.00151) | (0.00212) | |||

| Title length | 0.000114 | 0.00199 | 0 | 0.000400 | 0.000475 | − 0.000552 | 0.00194*** | 0.0407 | 0.00125** | 0.00275*** | 0.00201** | − 0.000647 |

| (0.000654) | (7.41e − 05) | (0.000782) | (0.00128) | (0.00147) | (0.000557) | (0.000520) | (0.000662) | (0.00101) | (0.00143) | |||

| Paper length | − 0.00337*** | − 0.067 | − 0 | − 0.00206** | − 0.00459*** | − 0.00454*** | − 0.00334*** | − 0.0798 | − 0.00164*** | − 0.00340*** | − 0.00520*** | − 0.00654*** |

| (0.000734) | (7.86e − 05) | (0.000830) | (0.00136) | (0.00156) | (0.000546) | (0.000552) | (0.000702) | (0.00108) | (0.00151) | |||

| Number of references | 0.000933*** | 0.0761 | − 0 | 0.000598*** | 0.00145*** | 0.000847** | − 0.000184 | − 0.018 | 0.000314** | − 2.42e − 05 | − 0.000487** | − 0.000929*** |

| (0.000164) | (1.81e − 05) | (0.000191) | (0.000314) | (0.000361) | (0.000138) | (0.000127) | (0.000162) | (0.000249) | (0.000350) | |||

| Author-level characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Physical age | − 0.00145*** | − 0.0638 | 0 | − 9.53e − 06 | − 0.00121** | − 0.00131* | 0.00135*** | 0.0709 | 0.000863*** | 0.00174*** | 0.00181*** | 0.00182*** |

| (0.000324) | (3.49e − 05) | (0.000368) | (0.000605) | (0.000694) | (0.000289) | (0.000245) | (0.000312) | (0.000478) | (0.000672) | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male (REF) | ||||||||||||

| Female | 0.0619*** | 0.0456 | − 0 | 0.00423 | 0.202*** | 0.159*** | 0.0292** | 0.0258 | 0.0246 | 0.0355* | 0.0557* | − 0.00412 |

| (0.0209) | (0.00224) | (0.0237) | (0.0389) | (0.0446) | (0.0139) | (0.0158) | (0.0201) | (0.0307) | (0.0432) | |||

| Nationality | ||||||||||||

| The U.S. (REF) | ||||||||||||

| Japan | − 0.00799 | − 0.00817 | − 0 | 0.00816 | − 0.00744 | − 0.0447* | 0.0328*** | 0.0401 | 0.0559*** | 0.0594*** | 0.0170 | − 0.0412* |

| (0.0104) | (0.00127) | (0.0134) | (0.0220) | (0.0253) | (0.00823) | (0.00892) | (0.0113) | (0.0174) | (0.0245) | |||

| United Kingdom | − 0.0417*** | − 0.0406 | 0 | − 0.0162 | − 0.0581** | − 0.0360 | 0.0442*** | 0.0516 | − 0.0105 | 0.0304** | 0.0649*** | 0.131*** |