Abstract

Objective

Low back pain (LBP) is a highly prevalent condition that poses significant patient burden. This cross-sectional study identified factors associated with LBP occurrence and developed a strategy to identify, prevent, and reduce LBP-related burden on patient health. A web-based questionnaire-answering system was used to assess the potential effects of LBP on mental health, assessing five domains (physical features, demographics, lifestyle, diet, and mental status) conceptually associated with hie, a common disease state traditionally described in the Japanese culture as a chilly sensation.

Results

Of 1000 women, 354 had and 646 did not have LBP. The Chi test identified 21 factors, and subsequent multivariate logistic regression indicated eight factors significantly associated with LBP: age, history of physician consultation regarding anemia, history of analgesic agents, dietary limitations, nocturia, sauna use, hie, and fatigue. Furthermore, women with LBP exhibited a significantly lower body temperature (BT) in the axilla/on the forehead than women without LBP. LBP and hie are subjective and potentially affected by patient mental status. Stress reduces blood circulation, causing hypothermia and possibly worsening LBP. Therefore, mental-health support is important for patients with LBP to reduce physiological stress. Hyperthermia therapy, a traditionally prescribed intervention, is a potential intervention for future studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13104-023-06276-4.

Keywords: Low back pain, Body temperature, Hie, Stress

Introduction

Many low back pain (LBP) patients show substantial discrepancies between the objective observations of medical practitioners and their subjective complaints, suggesting causes other than physiological disorders [1]. Particularly, 85% of chronic LBP (CLBP) cases are nonspecific, with no identified physiological, neural, or orthopedic spine disorders [2]. LBP frequently causes absenteeism among healthcare workers, nurses, and factory workers and profoundly affects the patients, society, and economy [3]. Consequently, LBP prevention requires a greater understanding of the causative factors to reduce the likelihood of its onset. Early detection/treatment should be the primary concern to achieve this goal. Psychological effect or social stress significantly affects LBP [4].

A recent study hypothesized that acute LBP might develop into CLBP (LBP lasting > 3 months) in the presence of psychological stress or other mental/emotional factors [1]. In Japan, LBP is a common ailment. The Japanese Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry regularly reported that the ratio of LBP prevalence/consultation is significantly high consistently [5]. The Japanese Orthopaedic Association recently developed a pain evaluation questionnaire assessing five key domains of LBP, including mental health [6–8]. It includes questions regarding physical and mental health, and many doctors focus on the mental health of LBP patients. This questionnaire was used to improve LBP identification and support targeted therapeutic strategies for efficient, multimodal interventions; however, LBP prevalence has not decreased, despite the questionnaire’s implementation.

Therefore, for this study, we prepared a new questionnaire comprising five domains (physical features, demographics, lifestyle, diet, and mental status) and further investigated the effects of mental status on LBP using body temperature (BT). Additionally, we utilized an original parameter, “hie,” a chilly or cold sensation. In Japan, hie is used to describe the subjective, uncomfortable feeling of coldness; females are 2.7 times more likely to suffer from it than males [5]. Although this term is very common in Japan, it has not been conceptually well-established in modern medicine owing to cultural and language barriers. We conducted a cross-sectional study on various factors using a questionnaire to investigate the background and cause of LBP, assess the possible effects of mental status on LBP, and propose a new approach to prevent LBP, particularly nonspecific LBP. We sought a new strategy to identify, prevent, and reduce the LBP-related health burden while considering early detection, BT assessment, traditional medicinal concepts, and effects of LBP on patient mental health.

Main text

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from a database maintained by a Japanese survey company (Cross Marketing Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The questionnaires were administered using an internet-based survey conducted by this company. Among 300,000 individuals listed in the database, 5000 were selected using random sampling, stratified by age and place of residence. This subsample was resampled by proportional allocation to balance the sex ratio, yielding a final sample size of 1000 individuals who were recruited. All participants were asked to use the web-based questionnaire-answering system. All participants who accessed the survey web page provided written informed consent before starting the questionnaire, and all of them also responded to the questionnaire. Owing to the BT recording location criteria, women without access to a contact-free thermometer (infrared thermometer) were excluded.

Low back pain

LBP refers to pain, stiffness, decreased lower back movement, and difficulty in straightening one’s lower back. Participants with or without LBP were divided into two groups: LBP ( +) (n = 354, 35.4%) and LBP ( −) (n = 646, 64.6%). Our questionnaire (Additional file 1) recorded clinical details, including doctor visits or diagnostic imaging. Participants were asked to report on various aspects of their LBP condition [6–8].

Hie

Hitherto the “hie” parameter has been uninvestigated; therefore, we incorporated it with regard to LBP into our new questionnaire. In traditional medicine, hie is known to induce pain, including in LBP patients [9]. Local or small-scale studies have been conducted; however, these cannot be considered sufficient evidence to explore the effect of hie on LBP [10–12]. We quantified hie (a traditional concept) by measuring BT (a modern concept) because, according to recently published studies, hie may be influenced by multiple factors, including mental status [13–16]. Other information that may affect both BT and hie, including current place of residence, place of birth, room temperature (RT) while answering the questionnaire, current dietary consumption, and mental status, was obtained through the questionnaire.

(i) Physical features

This domain included the following parameters: age, breathing rate, and body mass index (BMI). Participants were asked to select the appropriate age category. Simultaneously, participants were asked to measure and select their breathing rate.

As in previous studies, we calculated the BMI [17–19] by inquiring about the participant’s weight and height and applying the following formula:

Participants were categorized into three groups based on their BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–24.9, and ≥ 25.0).

(ii) Demographics

This domain included the following parameters: present residence, place of birth, and occupation. Social situations may influence LBP; therefore, we asked the participants to provide information about their current place of residence (present residence) and place of birth. We also inquired about their occupation.

(iii) Lifestyle factors

Living conditions, including RT [20–22], presence of a room heater and usage time, winter wear use, and air-conditioner use, might affect LBP. We asked participants to provide their RTs, history of heater use, usage time duration, use of winter wear, likability of the air-conditioner, history of consultations with a doctor regarding anemia, and history of analgesics use. Data on dietary limitations, menstrual history, recent history of catching a cold, and smoking history were also collected [17, 23].

Additionally, we asked the participants whether or not they exercised [24], the type of exercise performed, duration of time spent sitting in one position, duration of sleep [25–27], bedtime, frequency of going to the bathroom during sleeping hours (nocturia), bathing habits, and history of sauna use [28–30].

“Mild hie” is the sensation of feeling chilly, whereas “severe hie” indicates feelings of discomfort [10–13]. Therefore, we asked the participants regarding the presence or absence of hie.

(iv) Diet

According to previous studies, we asked the participants to rate their food intake frequency [31], especially cold foods, including fish, beans, fermented food, and richly flavored foods, as well as their taste and distaste for food.

(v) Mental status

Although the causes of LBP are difficult to identify, researchers have reported the possible influence of mental status on LBP [4, 32]. Anger may exacerbate LBP [33–36]; therefore, participants were asked to report their emotional experience [24].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Means (± standard deviations) were used to characterize the distributions of continuous variables.

First, Pearson’s chi-squared test was performed to study both groups (LBP [ −] or [ +]) and determine candidate factors for the multivariate analysis. Next, multiple logistic regression analysis with forward stepwise model selection was performed to determine the factors significantly associated with LBP. The values are presented as 95% confidence interval and adjusted odds ratio (OR). The dependent variable in the multiple logistic regression models was binary: LBP ( −) and LBP ( +), and the null hypothesis was that the probability of observing a regression coefficient of 0 or 1 is influenced solely by chance rather than by any of the independent variables. We also conducted Student’s t-test and analysis of variance to study LBP.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the participant’s basic characteristics. Among 1000 participants, 354 (35.4%) were grouped as LBP ( +) participants. Pearson’s chi-square test identified 21 factors in the five domains that were significantly associated with LBP. Many factors in the mental status domain showed a highly significant association with LBP.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the LBP ( −) and LBP ( +) groups

| Characteristics | LBP ( −) | LBP ( +) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total (n = 1000) | 646 | 64.6 | 354 | 35.4 | |

| Physical features | |||||

| Age (years) | 0.001** | ||||

| 20–29 | 145 | 73.2 | 53 | 26.8 | |

| 30–39 | 174 | 69.3 | 77 | 30.7 | |

| 40–49 | 180 | 60.8 | 116 | 39.2 | |

| 50–59 | 147 | 57.6 | 108 | 42.4 | |

| Lifestyle | |||||

| Breathing rate (/min) | 0.047* | ||||

| < 15 | 292 | 68.1 | 137 | 31.9 | |

| ≥15 | 354 | 62.0 | 217 | 38.0 | |

| Duration of heater use | 0.005** | ||||

| Whole sleeping duration | 68 | 56.2 | 53 | 43.8 | |

| Until waking up | 35 | 53.0 | 31 | 47.0 | |

| Until falling asleep | 46 | 74.2 | 16 | 25.8 | |

| Before waking up & until falling asleep | 25 | 52.1 | 23 | 47.9 | |

| Do not use heater while sleeping | 439 | 67.7 | 209 | 32.3 | |

| Do not use heater at all | 33 | 60.0 | 22 | 40.0 | |

| History of consultations with a doctor regarding anemia | < 0.001*** | ||||

| Currently undergoing anemia treatment | 13 | 48.1 | 14 | 51.9 | |

| History of anemia treatment | 50 | 52.1 | 46 | 47.9 | |

| Anemia present but not undergoing treatment | 64 | 50.8 | 62 | 49.2 | |

| Presence of diseases other than anemia | 57 | 60.6 | 37 | 39.4 | |

| Did not consult a doctor | 462 | 70.3 | 195 | 29.7 | |

| History of analgesics use | < 0.001*** | ||||

| 2/week | 20 | 51.3 | 19 | 48.7 | |

| 1/week | 28 | 45.2 | 34 | 54.8 | |

| 3/month | 65 | 57.0 | 49 | 43.0 | |

| Sometimes | 140 | 55.3 | 113 | 44.7 | |

| No history of use | 393 | 73.9 | 139 | 26.1 | |

| Dietary limitations | 0.001** | ||||

| Ongoing | 145 | 60.4 | 95 | 39.6 | |

| Sometimes | 300 | 61.5 | 188 | 38.5 | |

| No limitations | 201 | 73.9 | 71 | 26.1 | |

| Menstrual history | < 0.001*** | ||||

| Irregular | 115 | 55.0 | 94 | 45.0 | |

| Painful | 155 | 62.5 | 93 | 37.5 | |

| No problem | 286 | 71.9 | 112 | 28.1 | |

| Absence of menstruation | 90 | 62.1 | 55 | 37.9 | |

| Recent history of catching a cold | 0.028* | ||||

| No history of a cold | 515 | 66.8 | 256 | 33.2 | |

| Last October ~ no (~ September yes) | 83 | 57.6 | 61 | 42.4 | |

| Last October ~ yes | 48 | 56.5 | 37 | 43.5 | |

| Smoking history | 0.009** | ||||

| No history | 501 | 66.5 | 252 | 33.5 | |

| Sometimes | 18 | 42.9 | 24 | 57.1 | |

| Very often | 64 | 58.7 | 45 | 41.3 | |

| Smoked/not now | 63 | 65.6 | 33 | 34.4 | |

| Duration of sleep (hours) | 0.013* | ||||

| < 6 | 222 | 59.0 | 154 | 41.0 | |

| 6–7 | 214 | 66.7 | 107 | 33.3 | |

| ≥7 | 210 | 69.3 | 93 | 30.7 | |

| Frequency of using the bathroom at night (nocturia) | < 0.001*** | ||||

| 0 | 414 | 70.5 | 173 | 29.5 | |

| 1 | 181 | 57.3 | 135 | 42.7 | |

| 2 | 34 | 52.3 | 31 | 47.7 | |

| ≥3 | 17 | 53.1 | 15 | 46.9 | |

| History of sauna use | < 0.001*** | ||||

| Yes | 31 | 40.3 | 46 | 59.7 | |

| No | 615 | 66.6 | 308 | 33.4 | |

| Hie | 0.007** | ||||

| Yes | 328 | 68.9 | 148 | 31.1 | |

| No | 318 | 60.7 | 206 | 39.3 | |

| Diet | |||||

| Tastes and distastes | 0.001** | ||||

| Yes | 88 | 51.8 | 82 | 48.2 | |

| N/A | 244 | 67.6 | 117 | 32.4 | |

| No | 314 | 67.0 | 155 | 33.0 | |

| Cold foods | 0.004** | ||||

| Frequently | 265 | 59.4 | 181 | 40.6 | |

| N/A | 202 | 71.1 | 82 | 28.9 | |

| Hardly | 179 | 66.3 | 91 | 33.7 | |

| Consumption of richly flavored foods | 0.020* | ||||

| Frequently | 189 | 58.5 | 134 | 41.5 | |

| N/A | 272 | 67.2 | 133 | 32.8 | |

| Hardly | 185 | 68.0 | 87 | 32.0 | |

| Mental status | |||||

| Feelings of anger | 0.013** | ||||

| Yes | 152 | 58.5 | 108 | 41.5 | |

| N/A | 348 | 64.9 | 188 | 35.1 | |

| No | 146 | 71.6 | 58 | 28.4 | |

| Feelings of inferiority | 0.004** | ||||

| Yes | 265 | 70.1 | 113 | 29.9 | |

| N/A | 251 | 63.9 | 142 | 36.1 | |

| No | 130 | 56.8 | 99 | 43.2 | |

| Feelings of deteriorating health | 0.001** | ||||

| Yes | 109 | 56.2 | 85 | 43.8 | |

| N/A | 261 | 62.4 | 157 | 37.6 | |

| No | 276 | 71.1 | 112 | 28.9 | |

| Feelings of exhaustion | < 0.001*** | ||||

| Yes | 153 | 56.5 | 118 | 43.5 | |

| N/A | 239 | 62.1 | 146 | 37.9 | |

| No | 254 | 73.8 | 90 | 26.2 | |

| Feelings of failure | < 0.001*** | ||||

| Yes | 223 | 57.8 | 163 | 42.2 | |

| N/A | 196 | 63.4 | 113 | 36.6 | |

| No | 227 | 74.4 | 78 | 25.6 | |

LBP low back pain; BMI body mass index; RT room temperature

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

***P < 0.001

The proportion of LBP ( +) cases increased from 6.8% in the “20–29” age group to 30.7% in the “30–39” age group, 39.2% in the “40–49” age group, and 42.4% in the “50–59” age group. Ninety-nine LBP ( +) participants consulted doctors, while 255 did not. Of these 354 participants, 36 had specific LBP with a physiological cause; the remaining participants (318) had nonspecific LBP with an undetermined physiological cause.

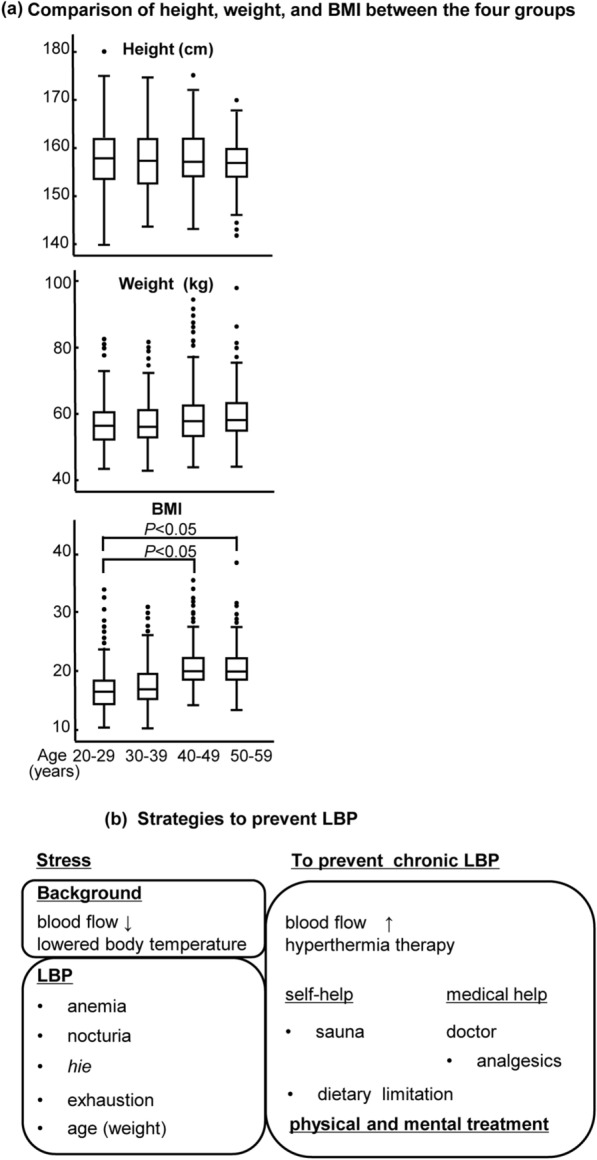

The multivariate logistic regression analysis identified eight factors associated with LBP (Table 2). Significant differences were observed between the age groups “20–29” and “40–49” and between the “20–29” and “50–59” by analysis of variance/post hoc analysis. No significant difference was found between the four groups with respect to height and weight.

Table 2.

Results of multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Parameters | Co-efficient | SE | P | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 20–29 | – | – | – | 1.000 | ||

| 30–39 | 0.901 | 0.230 | 0.000*** | 0.406 | 0.259 | 0.637 |

| 40–49 | 0.776 | 0.206 | 0.000*** | 0.460 | 0.307 | 0.689 |

| 50–59 | 0.340 | 0.189 | 0.072 | 0.712 | 0.491 | 1.031 |

| History of consultations with a doctor regarding anemia | ||||||

| Currently undergoing anemia treatment | – | – | – | 1.000 | ||

| History of anemia treatment | 0.756 | 0.430 | 0.079 | 2.129 | 0.916 | 4.951 |

| Anemia present (No treatment) | 0.614 | 0.240 | 0.010* | 1.848 | 1.155 | 2.954 |

| Presence of diseases other than anemia | 0.725 | 0.212 | 0.001** | 2.064 | 1.362 | 3.130 |

| Did not consult a doctor | 0.377 | 0.245 | 0.124 | 1.458 | 0.902 | 2.355 |

| History of analgesics use | ||||||

| 2/week | – | – | – | 1.000 | ||

| 1/week | 0.583 | 0.361 | 0.106 | 1.792 | 0.883 | 3.639 |

| 3/month | 1.078 | 0.301 | 0.000*** | 2.939 | 1.628 | 5.304 |

| Sometimes | 0.732 | 0.231 | 0.002** | 2.080 | 1.323 | 3.269 |

| No history | 0.751 | 0.171 | 0.000*** | 2.119 | 1.516 | 2.961 |

| Dietary limitations | ||||||

| Ongoing | – | – | – | 1.000 | ||

| Sometimes | 0.491 | 0.210 | 0.019* | 1.634 | 1.083 | 2.465 |

| No limitations | 0.384 | 0.182 | 0.035* | 1.468 | 1.028 | 2.096 |

| Frequency of using the bathroom at night (nocturia) | ||||||

| 0 | – | – | – | 1.000 | ||

| 1 | 0.527 | 0.412 | 0.201 | 0.590 | 0.263 | 1.324 |

| 2 | 0.016 | 0.419 | 0.969 | 0.984 | 0.433 | 2.237 |

| ≥3 | 0.092 | 0.484 | 0.849 | 0.912 | 0.353 | 2.357 |

| Sauna use | ||||||

| Yes | – | – | – | 1.000 | ||

| No | 1.049 | 0.276 | 0.000*** | 2.854 | 1.662 | 4.900 |

| Hie | ||||||

| No | – | – | – | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 0.183 | 0.070 | 0.009** | 1.201 | 1.047 | 1.378 |

| Feeling exhaustion | ||||||

| Yes | – | – | – | 1.000 | ||

| N/A | 0.473 | 0.174 | 0.007** | 0.623 | 0.443 | 0.876 |

| No | 0.126 | 0.178 | 0.480 | 1.134 | 0.800 | 1.609 |

| Constant | 1.025 | 0.479 | 0.032* | 0.359 | ||

CI confidence interval; OR odds ratio; SE standard error

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

***P < 0.001

The reasons for using these drugs include: “during menstruation” (386 [223 + 163] participants) and “back/knee pain” (46 [12 + 34] participants; 73.9% of them were LBP [ +]).

The main way of obtaining these drugs is via the “drug store/internet” rather than through a “doctor consultation.”

Discussion

Our findings identified eight factors that are significantly associated with LBP: age, history of consultation with a doctor regarding anemia, history of analgesics use, dietary limitations, nocturia, sauna use, hie, and feeling exhausted. We also found that participants with LBP had a significantly lower BT in the axilla/on the forehead than participants without LBP. These findings suggest that stress is the root cause of LBP owing to its association, both physically and mentally, with the eight identified factors. These findings shed light on the substantial discrepancies between objective observations of medical practitioners and subjective patient accounts of LBP.

Lumbar spine degeneration or muscular weakness may influence LBP. However, our results demonstrated that increase in weight and BMI with age were significantly associated with LBP (Fig. 1a) and may play a role in inducing LBP. The increase in weight/BMI with age may be why age was identified as a factor by multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2). We initially postulated that anemia might play a role in influencing LBP; however, high ORs for “history of anemia, no treatment” and “diseases other than anemia” may imply that many LBP patients who consult doctors do not suffer from “anemia.” Rather, LBP is the reason for visiting the doctor.

Fig. 1.

aComparison of height, weight, and BMI between the four groups. b Strategies to prevent LBP. LBP, low back pain; BMI, body mass index

Analgesics are designed for anti-inflammatory action and pain relief. To understand the reason ORs for “3(/month),” “sometimes,” and “no history” were higher than those for “2/(week),” we conducted further analysis of the 468 participants with a history of use of these drugs. The reasons and manner of obtaining analgesics (Tables 3 and Table 4) could explain the reason why the ORs for “3/month” and “sometimes,” which allude to menstruation, were higher than those for “2/week.” Therefore, it appears that participants used the drugs during menstruation and without obtaining a doctor’s prescription. A p value of < 0.001 for “menstruation” (Table 1) supports this understanding.

Table 3.

Reasons for analgesics use (n = 468)

| LBP (−) | LBP ( +) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| During menstruation | 223 | 57.8 | 163 | 42.2 |

| Back/knee pain | 12 | 26.1 | 34 | 73.9 |

| Skin disorder/fever | 18 | 50.0 | 18 | 50.0 |

LBP low back pain

Table 4.

Manner of obtaining analgesics (n = 468)

| LBP (−) | LBP ( +) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| After consultation with a doctor (Doctor’s prescription) | 47 | 45.2 | 57 | 54.8 |

| Drug store/internet | 187 | 56.2 | 146 | 43.8 |

| Friend/family | 19 | 61.3 | 12 | 38.7 |

LBP low back pain

Regarding “dietary limitations,” it is known that many Japanese women are on restricted diets [37]. However, the percentage of LBP (−) participants with “no dietary limitations” is 73.9% (Table 1). This may imply that LBP (−) participants do not have to be on dietary limitations as much as LBP ( +) participants do because they do not have to lose weight to manage LBP. In this study, the weight of LBP ( +) participants was significantly higher than that of LBP (−) participants (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of characteristics between LBP ( −) and LBP ( +) participants

| Characteristics | LBP (−) | LBP ( +) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | 157.74 ± 5.51 | 158.55 ± 5.68 | 0.638 |

| Weight (kg) | 51.70 ± 8.46 | 54.11 ± 10.39 | 0.002** |

| BT, axilla (℃) | 36.18 ± 0.36 | 36.13 ± 0.42 | < 0.000*** |

| BT, forehead (℃) | 36.11 ± 0.35 | 36.03 ± 0.39 | 0.003** |

| BT, hand (℃) | 34.33 ± 0.54 | 34.31 ± 0.57 | 0.179 |

| BT, foot (℃) | 32.23 ± 0.56 | 32.28 ± 0.57 | 0.456 |

| Highest recorded BT (℃) | 36.22 ± 0.34 | 36.18 ± 0.41 | < 0.001*** |

| Lowest recorded BT (℃) | 32.23 ± 0.56 | 32.28 ± 0.57 | 0.456 |

| Maximum BT difference (℃) | 3.99 ± 0.59 | 3.90 ± 0.59 | 0.543 |

| BMI | 20.72 ± 3.16 | 21.46 ± 3.89 | 0.001** |

LBP ( +) participants had a significantly lower BT in the axilla and on the forehead than LBP (−) participants

LBP low back pain; BT body temperature; BMI body mass index

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

***P < 0.001

The percentage of LBP ( +) participants who frequented the bathroom at night increased; 29.5%, 42.7%, 47.7%, and 46.9% of participants frequented the bathroom 0, 1, 2, and ≥ 3 times, respectively. This result may be useful to study LBP and to prevent accidental orthopedic conditions, including bone fracture or leg sprain. BT (axilla) of LBP ( +) participants was lower than that of LBP ( −) participants (Table 5), which may increase the frequency of night bathroom visits, although this needs further study. Bathroom visits at night are considered dangerous as they increase the risk of falls, which may result in injury in LBP ( +) participants.

In our study, only 77 participants indicated “sauna” use; however, interestingly, 59.7% of them were LBP ( +). LBP ( +) participants might experientially know that hyperthermia stimulation can ease LBP. Table 5 implies that the BT in the axilla/on the forehead reflects the BT in the trunk. The BT in the axilla is the deep (inside) BT and that of the forehead is the surface BT. Other BTs are away from the center (peripheral). This result may explain that LBP ( +) participants had lower BTs and may need hyperthermia stimulation.

Traditional medicine often uses hyperthermia stimulation; moxibustion stimulation eases LBP [38, 39], and so does hot spring therapy [40, 41]. The Japanese Orthopaedic Association conducted a systematic review analysis in 2022 and reported the efficiency of hyperthermia therapy for LBP management [42]. In Japan, many women suffer from hie, and this concept is not quite popular outside Japan. Although the study of hie alone is insufficient, both hie and LBP are understood subjectively. A recent study revealed a strong relationship between these two sensations [1].

As discussed above, LBP ( +) participants had a significantly lower BT in the axilla/on the forehead than that of LBP ( −) participants. This may be attributed to the fact that LBP ( +) participants are not as physically active as LBP (−) participants. Pain may weaken muscular action and muscle pumping, which circulates warm blood from the heart to the axilla.

Both hie and LBP are felt subjectively, and thus, they can be easily affected by mental status. Table 1 showed p values of < 0.05 for five of seven questions in the mental status domain. Interestingly, the multivariate logistic regression analysis identified only “feeling exhausted” as a factor (Table 2), and Table 1 shows a decrease in the percentage of LBP ( +) participants with the factor of “feeling exhausted” as follows: “yes” (43.5%), “N/A” (37.9%), and “no” (26.2%). It implies a strong association between the factor of “feeling exhausted” and LBP. Many researchers reported the effect of mental status on LBP. LBP ( +) participants may feel exhausted in daily life because of pain.

Increases in body weight and BMI affect LBP. Researchers reported the effect of mental status on factors associated with LBP, especially in CLBP [1]. In Table 1, the breathing rate (/min) of LBP ( +) participants was “ < 15” for 31.9% and “ ≥ 15” for 38.0%. Stress can increase breathing rate via the autonomic nervous system [43, 44]. Moreover, the result of the mental status domain in Table 2 shows the emotional status of the participants; stress manifested by emotions, including “anger,” “feeling of inferiority,” “deteriorating health,” “feeling exhausted,” and “feeling unsuccessful,” rather than “feeling happy.” Stress induces adrenaline stimulation, reduces blood circulation, and causes hypothermia under sympathetic nerve dominance [45, 46]. It may increase the frequency of night bathroom visits. Decreased blood circulation or lowered BT may worsen LBP. To avoid pain, some LBP ( +) patients consult a doctor while some adopt dietary limitations to reduce weight.

LBP ( +) patients often show substantial discrepancies between the objective observations of medical practitioners and patients’ subjective complaints. It is well known that stress affects mental status, and thus, researchers began to investigate mental status/attitude [47]. Currently, many workplaces regularly evaluate employees’ stress levels. As LBP ( +) participants demonstrated the factor of “feeling exhausted” in the mental status domain, we need to pay heed to their complaints and take effective measures.

Medical staff plays an important role in assisting LBP ( +) patients to prevent back pain from developing into a chronic/more severe pain. For example, fall-prevention strategy during nighttime bathroom visits and purchase of may help. Abuse of analgesics, which can be obtained over the counter or via the internet, may affect blood flow. Analgesics are inhibitors of cyclooxygenase, which stops prostaglandins production, and whole-body blood circulation is inhibited [48]. Therefore, LBP mechanism and appropriate drug usage should be properly understood (Fig. 1b).

Hie has not been researched thoroughly to date; however, both hie and LBP are undesirable sensations. Traditional medicine considers hie a harbinger of various diseases, and a common traditional prescription is hyperthermia therapy (sauna or hot spring). A recent study revealed strong effects between hie and LBP [1], and thus it is also important to investigate traditional therapy for LBP reduction.

Conclusions

Stressful lifestyles are a common part of modern society and may be a strong risk factor for LBP development, especially considering poor mental health status, decreased BT, and poor blood circulation. LBP is a physical disease; however, it may also involve mental health factors. We, therefore, recommend that timely diagnosis and treatment of psychological stressors and mental health counseling could help minimize LBP incidence.

Limitations

First, the sample size was small. Second, only participants who frequently use the internet could participate. Therefore, our results may not be representative of the wider population. Nonetheless, these factors may be valuable to assess in future studies, and some conclusions drawn here will lead to further debate.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all volunteers who participated in this study. We would also like to thank Editage for assistance with English language editing. We also thank Mr. Ko Shimabukuro and Ms. Ayae Kato of Cross Marketing Group Inc., Tokyo, Japan for designing the web research system.

Abbreviations

- LBP

Low back pain

- CLBP

Chronic low back pain

- BT

Body temperature

- BMI

Body mass index

- RT

Room temperature

Author contributions

MW, CT, and TN contributed to conception and design, data analysis, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript. TT and NM contributed to data analysis, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. All authors read approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Uchida Energy Science Promotion Foundation (R04-1–085) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science’s Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI Grant No. 19K10727).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ibaraki Prefectural University of Health Sciences (Ibaraki, Japan, e300-r120209). Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from participants.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interest in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ouchi K, Watanabe M, Tomiyama C, Nikaido T, Oh Z, Hirano T, et al. Emotional effects on factors associated with chronic low back pain. J Pain Res. 2019;12:3343–3353. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S223190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:363–370. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew J, Singh SB, Garis S, Diwan AD. Backing up the stories: the psychological and social costs of chronic low-back pain. Int J Spine Surg. 2013;7:e29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsp.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikaido T, Fukuma S, Wakita T, Sekiguchi M, Yabuki S, Onishi Y, et al. Development of a profile scoring system for assessing the psychosocial situation of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1853–1859. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S129957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Japanese Health, Labour, and Welfare Ministry. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa19/dl/04.pdf Accessed Aug 16 2022. in Japanese

- 6.Fukui M, Chiba K, Kawakami M, Kikuchi S, Konno S, Miyamoto M, et al. Japanese orthopaedic association back pain evaluation questionnaire. Part 2. Verification of its reliability: the subcommittee on low back pain and cervical myelopathy evaluation of the clinical outcome committee of the Japanese orthopaedic association. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12:526–532. doi: 10.1007/s00776-007-1168-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukui M, Chiba K, Kawakami M, Kikuchi S, Konno S, Miyamoto M, et al. Japanese orthopaedic association back pain evaluation questionnaire. Part 3. validity study and establishment of the measurement scale: subcommittee on low back pain and cervical myelopathy evaluation of the clinical outcome committee of the Japanese orthopaedic association. Japan J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:173–179. doi: 10.1007/s00776-008-1213-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukui M, Chiba K, Kawakami M, Kikuchi S, Konno S, Miyamoto M, et al. JOA back pain evaluation questionnaire (JOABPEQ)/JOA cervical myelopathy evaluation questionnaire (JOACMEQ). The report on the development of revised versions. April 16, 2007. The subcommittee of the clinical outcome committee of the Japanese orthopaedic association on low back pain and cervical myelopathy evaluation. J Orthop Sci Rev Vers. 2009;14:348–365. doi: 10.1007/s00776-009-1337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori H, Kuge H, Sakaguchi S, Tanaka TH, Miyazaki J. Determination of symptoms associated with hiesho among young females using hie rating surveys. J Integr Med. 2018;16:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamato T, Aomine M. Physical characteristics and living environment in female students with cold constitution. Health Evaluat Promot. 2002;29:878–884. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saga M, Imai M. Study of painful chills and associated factors in female university students. Ishikawa J Nurs. 2012;9:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai M, Akasofu K, Fukunishi H. Subjective chills, and their related factors in adult women. Ishikawa J Nurs. 2007;4:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sannomaru Y, Akiyama T, Numajiri S. Relationship of lifestyle and frequency of certain types of food intake on the chilliness of female college students. J Jpn Soc Food Life. 2016;26:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchida Y, Tsunekawa C, Sato I, Morimoto K. Effect of the menstrual cycle phase on foot skin temperature during menthol application in young women. J Therm Biol. 2019;85:102401. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2019.102401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monobe H. Proposal of quantification of sensibility to cold based on psychological procedure. Japan Soc Physiol Anthropol. 2009;14:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuwabara A, Hando T, Ikeda K. Symptoms of poor blood circulation in young people of both, male and female. Niigata Seiryo Univ Inst Rep. 2012;4:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Power C, Frank J, Hertzman C, Schierhout G, Li L. Predictors of low back pain onset in a prospective British study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1671–1678. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konishi H, Kaneda K, Takemitsu Y, Shiba K, Kurihara A, Iguchi T, et al. A study of medico-social factors related to delayed return to work in worker with low back pain. Jpn J Occup Med Traumatol. 2006;54:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto M, Kinoshita G, Shiraki T. Addressing occupational low back pain (OLBP): the role of good posture and education. J Lumbar Spine Disord. 2001;7:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakajima Y, Schmidt SM, Malmgren Fänge A, Ono M, Ikaga T. Relationship between perceived indoor temperature and self-reported risk for frailty among community-dwelling older people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:613. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuboi S, Mine T, Tomioka Y, Shiraishi S, Fukushima F, Ikaga T. Are cold extremities an issue in women’s health? Epidemiological evaluation of cold extremities among Japanese women. Int J Women Health. 2019;11:31–39. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S190414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi Y, Schmidt SM, Malmgren Fänge A, Hoshi T, Ikaga T. Lower physical performance in colder seasons and colder houses: evidence from a field study on older people living in the community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:651. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO. Are lifestyle-factors in adolescence predictors for adult low back pain? A cross-sectional and prospective study of young twins. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartvigsen J, Christensen K. Active lifestyle protects against incident low back pain in seniors: a population-based 2-year prospective study of 1387 Danish twins aged 70–100 years. Spine. 2007;32:76–81. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250292.18121.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakajima H. Association between sleep duration and hemoglobin A1c level. Sleep Med. 2009;10:937–938. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Youngstedt SD, Kripke DF. Long sleep and mortality: rationale for sleep restriction. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:159–174. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freiwald J, Hoppe MW, Beermann W, Krajewski J, Baumgart C. Effects of supplemental heat therapy in multimodal treated chronic low back pain patients on strength and flexibility. Clin Biomech. 2018;57:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baig AAM, Ahmed SI, Ali SS, Rahmani A, Siddiqui F. Role of posterior-anterior vertebral mobilization versus thermotherapy in non specific lower back pain. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34:435–439. doi: 10.12669/pjms.342.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pittler MH, Karagülle MZ, Karagülle M, Ernst E. Spa therapy and balneotherapy for treating low back pain: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Rheumatol. 2006;45:880–884. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagata C, Wada K, Tamura T, Konishi K, Goto Y. Hot-cold foods in diet and all-cause mortality in a Japanese community: the Takayama study. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27:194–199.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang H, Haldeman S, Lu ML, Baker D. Low back pain prevalence and related workplace psychosocial risk factors: a study using data from the 2010 national health interview survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39:459–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carson JW, Keefe FJ, Lowry KP, Porter LS, Goli V, Fras AM. Conflict about expressing emotions and chronic low back pain: associations with pain and anger. J Pain. 2007;8:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burns JW, Gerhart JI, Bruehl S, Peterson KM, Smith DA, Porter LS, et al. Anger arousal and behavioral anger regulation in everyday life among patients with chronic low back pain: relationships to patient pain and function. Health Psychol. 2015;34:547–555. doi: 10.1037/hea0000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nisenzon AN, George SZ, Beneciuk JM, Wandner LD, Torres C, Robinson ME. The role of anger in psychosocial subgrouping for patients with low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:501–509. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruehl S, Liu X, Burns JW, Chont M, Jamison RN. Associations between daily chronic pain intensity, daily anger expression, and trait anger expressiveness: an ecological momentary assessment study. Pain. 2012;153:2352–2358. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murnen SK, Smolak L. Femininity, masculinity, and disordered eating: a meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:231–242. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199711)22:3<231::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamiyama S, Iwatuki H, Oda F, Kasuya K, Sato M, Seki R, et al. The actual condition of patients treated by acupuncture in Ibaragi prefecture. Jpn Acupunct Moxibustion. 1987;37:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsukayama H. Acupuncture treatment for low back pain at Taukuba college of technology clinic. The J Jpn Soc Lumber Spine Disord. 1995;1:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yokoi T, Senda M, Hamada M, Mitsunobu F, Hosaki F, Ashida K, et al. QOL in LBP patients. Nippon Onsen Kiko Butsuri Igakkai Zasshi. 2004;74:48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka N. My research on balneology, sauna, exercise, and rehabilitation medicine. Nippon Onsen Kiko Butsuri Igakkai Zasshi. 2016;79:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shirado O, Arai Y, Iguchi T, Imagama S, Kawakami M, Nikaido T, et al. Formulation of Japanese orthopaedic association (JOA) clinical practice guideline for the management of low back pain-the revised 2019 edition. J Orthop Sci. 2022;27:3–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2021.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abo T, Kawamura T. Immunomodulation by the autonomic nerves system: therapeutic approach for cancer, collagen diseases, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Ther Apher. 2002;6:348–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2002.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakaki K. Variation in the ratio of leukocytes in women caused by yoga breathing. Jpn J Phys Fit Sports Med. 2006;55:477–488. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe M, Tomiyama-Miyaji C, Kainuma E, Inoue M, Kuwano Y, Ren H, et al. Role of alpha-adrenergic stimulus in stress-induced modulation of body temperature, blood glucose and innate immunity. Immunol Lett. 2008;15(115):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minagawa T, Okubo K, Tanaka N. Studies on pathophysiology and possible cause of hie-symptom. Nippon Onsen Kiko Butsuri Igakkai Zasshi. 2020;83:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe K, Otani K, Nikaido T, Kato K, Kobayashi H, Handa J, et al. Usefulness of the brief scale for psychiatric problems in orthopaedic patients (BS-POP) for predicting poor outcomes in patients undergoing lumbar decompression surgery. Pain Res Manag. 2021;2021:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2021/2589865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lucas S. The pharmacology of indomethacin. Headache. 2016;56:436–446. doi: 10.1111/head.12769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.